Escherichia coli contamination in minced meat poses a significant public health concern and may serve as a reservoir for antimicrobial-resistant strains. This study investigated the presence of E. coli resistant to ciprofloxacin and/or gentamicin in minced meat samples from Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Resistant E. coli isolates were identified using MALDI-TOF. A total of 109 samples were analyzed, yielding 97 E. coli isolates (23 from AMC-CIP and 74 from AMC-GEN). Twenty-three isolates carried the ant(2″) gene, ten the ant(3″) gene, and one the blaCTX-M gene. Resistance was observed to gentamicin (6/25), streptomycin (1/25), ceftazidime (1/25), and cefotaxime (4/25). Eleven isolates carried the aggR gene, and another three were identified as biofilm producers. Although phenotypic resistance was low, we detected genetic potential for resistance which, combined with biofilm formation, represents a risk to food safety.

La contaminación de la carne picada por Escherichia coli tiene un fuerte impacto en la salud pública y podría ser una fuente de cepas con resistencia a antimicrobianos. Este trabajo analizó la presencia de aislamientos de E. coli resistentes a ciprofloxacina, a gentamicina o a ambos en muestras de carne picada de Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Los aislamientos resistentes se identificaron mediante MALDI-TOF. Se estudiaron 109 muestras y se obtuvieron 97 aislamientos totales de E. coli (23 desarrollados en AMC-CIP y 74 de AMC-GEN). Veintitrés aislamientos presentaron el gen ant(2”), 10 el gen ant(3”) y uno el gen blaCTX-M. Se observó resistencia a gentamicina (6/25), estreptomicina (1/25), ceftazidima (1/25) y cefotaxima (4/25). Once aislamientos portaron el gen aggR y otros tres fueron productores de biofilm. Aunque la resistencia fenotípica fue baja, identificamos el potencial genético de resistencia, que, junto con la formación de biofilm, representa un riesgo para la seguridad alimentaria.

Food borne diseases have become an important public health concern worldwide, affecting both developed and underdeveloped countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified more than 200 diseases that may result from the consumption of food contaminated with bacteria, viruses, parasites or chemical substances such as heavy metals. Foodborne diseases can generate a wide range of pathologies, with gastrointestinal issues being the most frequent10.

There are different ways in which food and water can become contaminated with microorganisms and/or their toxins. Food can get contaminated at different points in the production chain, including the environment where animals are raised and plants are harvested. Contamination also occurs frequently during the production process such as transportation, processing, handling, or as a result of cross-contamination from individuals who prepare the food12.

The main source of infection for many foodborne pathogens are animals raised for food production (cattle, sheep, chickens, pigs, among others)1,14. Microorganisms, mainly foodborne bacteria, are the main threat to food safety, causing human infections or poisoning after the consumption of products of animal origin contaminated with these microorganisms or their toxins13. Escherichia coli is a member of the normal gut microbiota, but some strains carry virulence genes and are classified as either enteric or extra intestinal pathogens, depending on their virulence genes9.

Poor practices in slaughterhouses can pose a risk to human health, either through contamination or the generation of hazardous effluents. Safe practices minimize carcass contamination with feces, and hygienic handling of foods at abattoirs and during food production can reduce contamination45.

E. coli is frequently used as a sentinel microorganism for antimicrobial resistance in animal husbandry due to its abundance in healthy individuals and its ability to demonstrate the selective pressure exerted by antibiotic use on Gram-negative enteric bacteria. Resistance mechanisms present in E. coli can spread to humans through direct contact, the consumption of meat, or indirectly through the environment34. This resistance is normally acquired through horizontal gene transfer with other bacteria, which may belong to different genera. Additionally, resistance can also emerge due to genetic mutations. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria often possess a repertoire of resistance genes, facilitated by the presence of integrons and gene cassettes that enable them to uptake and collect antibiotic resistance genes.32

One of the most commonly reported resistance mechanisms to β-lactam antibiotics among Enterobacterales is the production of β-lactamases, enzymes that hydrolyze β-lactam antibiotics. Extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) efficiently hydrolyze third and fourth-generation cephalosporins, along with monobactams. The most prevalent ESBLs worldwide are the CTX-M-family, which are inhibited by compounds such as clavulanic acid and tazobactam11.

The emergence of CTX-M was considered one of the major causes of superbugs resistant to multiple transferable antibiotics, particularly in E. coli. Furthermore, CTX-M-producing E. coli often displays resistance to multiple classes of antimicrobials, such as fluoroquinolones, sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, and tetracyclines3.

The monitoring of E. coli resistance includes the evaluation of susceptibility to antimicrobials that are important in human and veterinary medicine, as well as those commonly employed for epidemiological purposes. Some of these antimicrobials are included in the list of critically important categories (third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, polymyxins) for human medicine developed by the World Health Organization. Additionally, this monitoring extends to other high-priority agents, such as aminoglycosides, macrolides, and tetracyclines. The objective of this study is to comprehensively assess the virulence characteristics, resistance profiles, and genetic markers present in E. coli isolated from minced meat obtained from butcher shops in Tierra del Fuego, Argentina.

Materials and methodsAll butcher shops in the three towns of the island of Tierra del Fuego (TDF) were georeferenced. A 500-gram sample of ground meat was purchased from each market over the course of a one-week sampling period conducted in spring 2019. The samples were collected in sterile bags to avoid cross-contamination and were immediately frozen for air transport to the laboratory in cooled boxes. Each sample was thawed at 4°C overnight at the Microbiology Laboratory of the Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Detection of antimicrobial drug residues in the meat matrixA proportion of the meat samples, randomly selected from the study group was analyzed for the detection of cephalexin, enrofloxacin, and streptomycin. The detection of traces of these antibiotics was performed on 20g of the meat samples. The residues of cephalexin were determined using a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method27, while the enzyme immunoassay using the Ridascreen® kit was utilized for the remaining analyses.

Sample analysisA total of 109 minced samples were analyzed. Portions of each sample (65g) were stomached for 2min in 585ml of tryptic soy broth (TSB) and incubated at 37°C overnight under aerobic conditions. Next, 0.1ml of the broth was cultured on MacConkey Agar (MCA) supplemented with antimicrobials. We used MCA supplemented containing 1μg/ml ciprofloxacin (MCA-CIP)57, MCA supplemented with 4μg/ml gentamicin (MCA-GEN)31 and MCA without antimicrobials, as a control. The plates were incubated for 24h at 37°C and assessed qualitatively for the presence or absence of E. coli colonies with typical morphology. The number of colonies grown on MCA-CIP and MCA-GEN was recorded. Up to five colonies from positive cultures were selected for further studies and stored in TSB plus glycerol (20%) at −20°C. Catalase, oxidase and glucose fermentation tests were used for the presumptive identification of E. coli from the suspected isolates obtained on both media. All the isolates were then identified by matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF MS).

Each isolate was suspended in 200μl of milliQ water and heated at 100°C for 10min. The supernatant was used for the screening of antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence markers of diarrheagenic strains, and additional virulence factors. Moreover, the genetic diversity of the different E. coli recovered from a single sample was evaluated by random amplified polymorphic DNA PCR (RAPD).

Antibiotic resistance characterizationAntimicrobial resistance genes for aminoglycosides (ant(2″), ant(3″), aph(3′)-Vla, aac(6′)-Ib, acc(3)-IIa, -llc, -lld, -lie, rmtB)6, plasmid mediated quinolone resistance-PMQR (qnrA, qnrB, qnrD, qnrS, aac(6′)-Ib-cr)7 and ESBL, such as blaCTX-M-group30, were searched for in those isolates identified as E. coli. blaCTX-M-group 2 amplicons were sequenced.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on those isolates testing positive for the targeted resistance genes using the disk diffusion method in accordance with Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2023) guidelines. The antimicrobial agents assessed were amoxicillin–clavulanic acid 20/10μg (AMC), cefotaxime 30μg (CTX), ceftazidime 30μg (CAZ), imipenem (IMI), streptomycin (STR), amikacin (AKN) and gentamicin 10μg (GEN). Commercial antibiotic disks were acquired from Britania S.A.® (Argentina).

Random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) genotypingGenetic diversity of the different E. coli recovered from a single sample with the same antibiotic resistance profile was evaluated by random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) using the M13 RAPD primer. The isolates were grown in TSB, and total DNA was obtained by boiling at 100°C for 10min. A 1:10 dilution of the boiled lysate was used as template. Pattern bands were visually analyzed in agarose gel 1%. Similarity in the amplification profile was used to select the number of strains for the following assays.

Virulence profileThe presence of virulence markers of E. coli pathovars were analyzed by PCR: stx1/stx2 for Shiga toxin-producer E. coli (STEC)38, eae for enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC)38, aaiC2 and aagR54 for enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), invE for enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC)16, elt and estA for enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)16 and daaE for diffuse aggregation E. coli (DAEC)53. Primers for the detection of genetic markers are shown in Table S1.

Moreover, several virulence factors including attA33, iha48, lpf51, ecpA15, toxB50, and efaC17 related to putative adhesins were searched.

SerotypesAll isolates were serotyped using agglutination assays with rabbit antisera: 187 sera were used against somatic antigens (O), and 53 sera were used against flagellar antigens (H) at the Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).

Biofilm assayBiofilm production was assessed using a quantitative 96-well plate assay following the protocol outlined by Vélez et al52. Briefly, each strain was inoculated into a tube containing 5ml of Luria Bertani (LB) broth and incubated at 37°C overnight with agitation. The cultures were subsequently diluted until reaching a turbidity equivalent to 0.5 on the McFarland scale. Then, 10μl of each dilution was seeded into 190μl of LB supplemented with sodium chloride in triplicate wells and incubated at 37°C for 24h. In the subsequent step, the media was refreshed, replacing it with LB containing glucose. Following a total of 48h of incubation, the microplates were washed with distilled water, fixed with 200μl of methanol for 15min, and stained with a 0.1% aqueous solution of crystal violet (200μl for 30min). After rinsing with water and drying for an hour at room temperature, the adhered dye was eluted with 200μl of ethanol under agitation. Absorbance was measured at 570nm (OD570). The results were interpreted by correcting the mean of the three OD570 measurements for each strain with respect to the cut-off value (ODc), which was set at 3 standard deviations above the mean OD570 measurements of a negative control strain (non-biofilm producer, QC148 EHEC). The corrected value enabled the classification of the strains as non-biofilm producers (OD≤ODc), weak biofilm producers (ODc<OD≤2 ODc), moderate biofilm producers (2ODc<OD≤4 ODc), and strong biofilm producers (OD >4 ODc). The assay was performed in triplicate.

ResultsPresence of antimicrobial drug residues in the meat matrixThe cephalexin residue was detected at concentrations below 100μg/kg in 42 of the minced meat samples analyzed (38.5%), while streptomycin residues were observed at levels below 20μg/kg in 81 minced meat samples (74.3%). Additionally, enrofloxacin residues were detected at concentrations below 10μg/kg in 78 of the samples studied (71.6%). These findings provide valuable information on the minimal contamination of the minced meat with the tested antibiotics and, consequently, the low exposure risks associated with these drugs.

Sample screeningA total of 109 samples were analyzed in this study. Of these, four did not yield any colony growth on any of the culture media. Among the 105 samples that showed growth on MCA, 26 yielded colonies on MCA-CIP and 41 on MCA-GEN (Table 1). Colony counts on media supplemented with antibiotics ranged from 1×103CFU/g to uncountable levels (Table S2).

Isolate recovery on MAC-CIP and MAC-GEN media from 105 minced meat samples.

| MAC-CIP | MAC-GEN | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Samples with growth | 26 | 41 | 66 |

| Isolates analyzed | 110 | 156 | 266 |

| Positive samples with E. coli | 5 | 21 | 22* |

| E. coli by MALDI-TOF | 23 | 74 | 97 |

MAC-CIP: MacConkey Agar with ciprofloxacin; MAC-GEN: MacConkey Agar with gentamicin.

Based on the selection criterion of five colonies per sample for subsequent confirmation, this number was not achieved in all cases. From MCA-CIP, E. coli was confirmed by MALDI-TOF in 23 of the 110 isolates, corresponding to five of the 26 samples. Additionally, E. coli was confirmed by MALDI-TOF in 74 of the 156 isolates obtained from MCA-GEN, representing 21 of the 41 samples.

The remaining isolates, 87 of the 110 from MCA-CIP and 82 of the 156 from MCA-GEN, were presumptively selected, but were later identified as other taxa.

Further examination of these strains revealed the presence of several other bacterial taxa, with the most prevalent ones being Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (13%). Other identified species were Raoultella ornithinolytica (4.7%), Citrobacter braakii (4.1%), Enterobacter bungandensis (4.1%), Leclercia adecarboxilata (3.5%), Citrobacter freundi (3.5%), Pseudomonas fulva (2.9%), Myroides injenensis (2.9%), Klebsiella oxytoca (2.9%), Providencia rettgeri (2.9%), Proteus hauseri (1.18%) and 0.6% for each of the following species: Serratia marceccens, Enterobacter cloacae, Hafnia alvei, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterobacter asburiae and Enterococcus hirae, highlighting the diversity of bacterial communities within these samples.

In summary, a total of 266 isolates were successfully recovered from the samples tested with both antimicrobials (Table 1). Among these isolates, 97 were conclusively identified as E. coli through MALDI-TOF identification (Table S2).

Antibiotic resistance determinationGenetic analysis of E. coli isolates revealed interesting insights into antibiotic resistance determinants. Specifically, 25 of 97 E. coli isolates were found to carry antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes (Table 2): 23 strains recovered from 4 different meat samples (A, B, C, D) were positive for ant(2″)-Ia gene, while 10 harbored the ant(3″)-Ia gene (belonging to the meat samples D, E, F). Remarkably, eight of these isolates exhibited the co-occurrence of both aminoglycoside resistance markers (sample D). In a subset of four isolates recovered from the same sample (D), the presence of the blaCTX-M group 2 gene was also detected, pointing to the potential for multidrug resistance. Sequencing confirmed the presence of the blaCTX-M-2 allelic variant in these four isolates, which also harbored both aminoglycoside resistance genes.

Resistance markers, virulence profile, and serotyping of isolates.

| Meat sample (isolates) | ant(2″) | ant(3″) | blaCTX-M-2 | RAPD profile | aggr | lpf | ecpA | efaC | Serotype | Biofilm formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (5) | + | − | − | II | + | + | − | − | O18ac:H21 | Non-producer |

| B1 (3) | + | − | − | IV | + | − | + | + | ONT:H− | Non-producer |

| B2 (2) | + | − | − | V | + | − | + | + | ONT:H− | Non-producer |

| B3 (1) | + | − | − | VI | − | − | + | − | O23:H8 | Moderate producer |

| C (4) | + | − | − | VII | − | + | − | − | O164:H40 | Non-producer |

| D1 (1) | + | + | + | VIII | − | + | + | + | O130:H25 | Low producer |

| D2 (3) | + | + | + | VIII | − | − | + | + | O130:H25 | Non-producer |

| D3 (4) | + | + | − | VIII | − | − | + | + | O130:H25 | Non-producer |

| E (1) | − | + | − | I | + | + | − | − | ONT:H− | Non-producer |

| F (1) | − | + | − | III | − | + | + | − | ONT:H− | Moderate producer |

Note: B and D samples showed different profiles (B1–B3; D1–D3).

All the isolates showed negative amplification results for the remaining aminoglycoside resistance genes. Interestingly, none of the E. coli isolates in our study exhibited the presence of PMQR determinants, suggesting alternative mechanisms of quinolone resistance within this population.

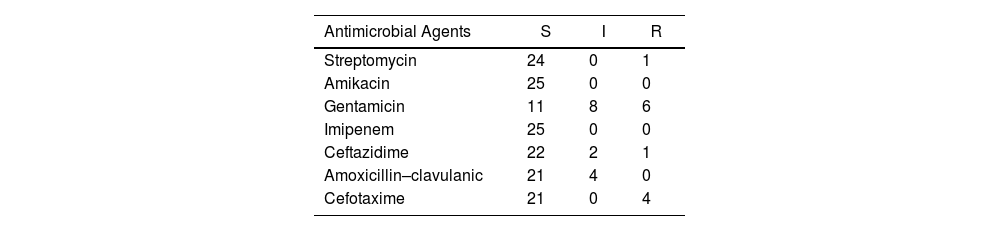

The results of the antimicrobial susceptibility tests for E. coli isolates that tested positive for the genetic markers are shown in Table 3. Furthermore, complete information for each isolate is presented in Table S3. An excellent congruence was observed between the detected genes and the corresponding resistance profiles. All the blaCTX-M-2-positive isolates were non-susceptible to AMC, CTX (4/4) and CAZ (3/4). In addition, 14 of 25 isolates exhibited phenotypic resistance to GEN. As expected, none of them were resistant to IMI or AKN. The susceptibility results of the isolates with the resistance genes are shown in Table S3.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test of 25 E. coli isolates harboring resistance genes.

| Antimicrobial Agents | S | I | R |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | 24 | 0 | 1 |

| Amikacin | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Gentamicin | 11 | 8 | 6 |

| Imipenem | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Ceftazidime | 22 | 2 | 1 |

| Amoxicillin–clavulanic | 21 | 4 | 0 |

| Cefotaxime | 21 | 0 | 4 |

S: susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

The 25 AMR-positive E. coli isolates which belong to 6 different samples (A–F) were genotyped by RAPD PCR20. This analysis revealed 8 different profiles and even one of them showed diversity in AMR gene content (sample D). In addition, differences in the virulence profiles were observed among isolates from the same sample (B or D), despite having the same profile according to RAPD (Table 2). Only one group of isolates belonging to a single RAPD profile (pattern VIII, sample D) was strictly associated with all three genetic markers of resistance.

Virulence profile and biofilm formationRegarding the virulence profile, all strains tested negative for diarrheagenic pathovars such as STEC, EPEC, ETEC, EIEC, DAEC. However, eleven isolates showed evidence of the aggR gene associated with the EAEC pathovar54. Furthermore, among these EAEC strains, five were positive for both the ecpA and efaC genes, while the other six were lpf-positive (Table 2). The remaining fourteen aggR-negative isolates exhibited putative virulence genes, including lpf, ecpA and efaC, whereas attA, iha and toxB were not detected in any of the 25 isolated AMR-positive E. coli. On the other hand, three of these isolates were classified as biofilm formers (1 low and 2 moderate producer); the remaining isolates were categorized as “non-producers” (Table 2).

SerotypesIsolates of each RAPD, virulence, or resistance marker pattern were serotyped (Table 2). The 25 isolates belonged to 5 different serotypes (one per sample): O18ac:H21 (A), O23:H8 (B3), O164:H40 (C), O130:H25 (D1, D2, D3). Additionally, isolates of four patterns were identified as ONT:H− (B1, B2, E, F).

DiscussionGround meat poses a significant risk because surface contamination with E. coli can spread throughout the entire product mass29. Contamination data can vary significantly across the Argentinean territory. The southern province of TDF has a subpolar oceanic climate with cold temperatures throughout the year, averaging 5–7°C annually. On the island of TDF, two slaughterhouses process local bovine and sheep production. Imported meat from the mainland is allowed only as vacuum-packed, boneless whole cuts, which are not used for grinding. As a result, the degree to which the population is exposed to antimicrobial residues used in animal production or resistant E. coli in ground meat is particularly unknown. Cephalexin, enrofloxacin and streptomycin were found in low but detectable concentrations, compared to Greece, where the highest median concentrations were detected in bovine muscles for streptomycin and quinolones at 182.10μg/kg and 50.78μg/kg, respectively47. Despite this fact, the concentration of these antibiotics is below the MRL (maximum residue limits) allowed by the Argentine food code5; however, their residues can still contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance in the gut microbiota, which is a significant threat to public health23,45.

Sakar et al.44 conducted a study in Tennessee, USA, where they quantified residues of tetracycline, sulfonamide, and erythromycin in beef marketed as “antibiotic-free” at farmers’ markets. They found that all beef samples contained residues of these antibiotics. The median concentration of tetracycline residue was 51.75μg/kg, while the median concentrations for sulfonamide and erythromycin residues were 3.50μg/kg and 3.67μg/kg, respectively. The chain of events that leads to the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) can be identified as effective causal complexes. One of the primary microorganisms associated with AMR is E. coli. Our work represents the first record of AMR genes circulating within the meat supply chain and highlights the presence of antimicrobial drug residues in the meat matrix of the region. Although the identification of other taxa in samples subjected to antibiotic pressure lies beyond the scope of this study, it is important to highlight that such microorganisms may serve as reservoirs or vectors for antimicrobial resistance and/or virulence genes. Their potential dissemination via food chains and environmental routes represents a concern for public health and warrants further investigation26.

In this study, the antibiotic resistance patterns of E. coli revealed that 24% (6/25) of isolates were resistant to gentamicin, with an additional 32% showing intermediate sensitivity. Resistance to streptomycin was found in 4% of isolates, while 16% exhibited intermediate resistance to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. Notably, 16% of isolates were resistant to cefotaxime, 4% to ceftazidime, and 8% showed intermediate resistance. All isolates were sensitive to amikacin and imipenem. In contrast, a study by Dsani8 on raw meat reported high susceptibility rates for gentamicin (97%) and ciprofloxacin (92%), but noted that 17% of the samples were resistant to cefuroxime, with the blaTEM gene detected in 4% of cases. Kassem et al.19 revealed that 1.7% of E. coli isolates from raw minced meat in Lebanon were resistant to cefotaxime and 2.5% to gentamicin. Additionally, 5.8% were resistant to kanamycin and 30% to streptomycin, although all isolates remained sensitive to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid and imipenem. Lastly, Rahman41 found 100% resistance to ciprofloxacin and gentamicin in E. coli isolates from meat.

In our genetic analysis, we identified the ant(2″)-Ia and ant(3″)-Ia genes, which encode resistance to aminoglycosides. The nucleotidyltransferases ANT(2″) and ANT(3″) are the enzymes most commonly associated with aminoglycoside resistance in Gram-negative bacteria40.

A study by Xiao and Hu56 demonstrated that E. coli exhibited high resistance to gentamicin, streptomycin, and etimicin, while resistance to amikacin and isepamicin was low. The predominant resistance mechanism identified was the aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme AAC(3)-I. Lee et al.25 investigated the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in E. coli from retail meats in California, finding that 30.48% and 16.9% of isolates were resistant to gentamicin and streptomycin, respectively. Nine genes encoding various acetyltransferases, nucleotidyltransferases, or phosphotransferases were responsible for this resistance profile, with the most frequently observed being aph(3″)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, aac(3)-VIa, and ant(3″)-Ia25.

Due to its reproducibility, cost effectiveness, speed, and practicality, the RAPD method genotyping, especially when dealing with many isolates, has been described as a great tool for evaluating clonal diversity of E. coli isolates36. We used M13 RAPD genotyping to understand the genetic diversity and relatedness of isolates belonging to the same sample with at least one resistance gene. This technique was successful in amplifying different sized products for all isolates. Ndegwa et al.35, found highly similar RAPD profiles in some strains belonging to some serogroups, whereas other serogroups generated a higher diversity in the generated RAPD pattern. Our results showed an identical profile in E. coli O130:H25 isolates, even when this serogroup was associated with diversity in resistance or virulence markers, resulting in three diverse patterns. According to Ndegwa et al.35, the ONT groups showed high diversity by RAPD, which could be associated with intrinsic difference among strains with ONT, because it was not a formal serogroup. Some strains previously identified as ONT could be later assigned to a specific serogroup. Thakur et al.49 identified 30% of diarrheagenic E. coli isolates as ONT. Interestingly, untypeable isolates belonged to various categories of DEC pathotypes49. In contrast to these reports, two of our isolates did not carry genetic markers of DEC, whereas the other five carried EAEC markers. E. coli serogroups have been largely associated with identifying clonal variants of DEC pathotypes rather than providing precise identification4,18. Although in some cases RAPD was able to discriminate among E. coli based on serogroups, in those with higher diversity most of the clustering was based on the presence of a specific gene combination. In Argentina, genetic diversity has been reported within the same M13 RAPD pattern and STEC serogroup isolated from meat, even in isolates sharing the same combination of virulence genes22. Our results highlight the previous unreported diversity of E. coli harboring resistance and virulence markers from meat in TDF. These data are important for determining their significance as public health pathogens.

An isolate from O18ac:H21 was reported from cattle in Mexico42 but carrying a stx2 virulence profile. In our study, the isolate was aggR positive, and highlighted the potential of the serotype to host a phage carrying the stx2 toxin. Moreover, serogroup O18ac was associated with hybrid ExPEC/EAEC and the ST131 clone carrying its own set of acquired resistance and virulence genes43.

The mere presence of virulence genes does not mean that the strain is pathogenic; however, E. coli O23 strains were observed in isolates from organs after Psittacidae necropsy21. In our study, this O23 isolate came from meat samples, and the animals in the slaughterhouse were expected to be healthy. Anyway, their relationship to virulence and resistance genes allows us to suspect their potential risk.

We found 3 isolates classified as low to moderate biofilm producers, identified as O23, O130, and ONT serotypes. Although biofilm production in this group of bacteria may be associated with antibiotic resistance, these strains exhibited antimicrobial resistance genes that explain this resistance. Our results align with those of Pellegrini et al.39, who isolated E. coli strains from 10 horticultural farms and observed moderate and low biofilm production, without being able to associate this characteristic with antimicrobial resistance, even though all the isolates tested exhibited biofilm production. The importance of this phenotypic characteristic should be considered in strains found in their natural environment28.

This resistance could be the result of the indiscriminate use of these antibiotics in animal production, which exerts selective pressure that favors the proliferation of resistant bacteria24. Resistance to CIP and GEN limits the therapeutic options available to treat the infections caused by these strains, highlighting the importance of prudent antibiotic management.

Transferable resistance mechanisms, such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and aminoglycoside resistance genes, were detected in several isolates. The detection of blaCTX-M-2 in some isolates is particularly alarming since this enzyme confers resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, including third and fourth generation cephalosporins. These resistance mechanisms can be transferred horizontally between bacteria, facilitating the spread of resistance in different environments, including human and animal. Continued surveillance and control of antimicrobial resistance are essential to address this threat from a “One Health” approach37,55.

E. coli is a key indicator of food hygiene, and its monitoring in meat samples points to the potential presence of antimicrobial-resistant strains capable of causing infections in humans, encompassing resistance profile.

Food handlers can be asymptomatic carriers of E. coli with varying antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles, posing a significant risk of spreading the microorganism through improper practices46. Across the entire food chain (whether industrial, small merchants or households) food handlers play a crucial role in food preparation. Poor manufacturing practices, often influenced by cultural factors and inadequate risk perception, exacerbate this issue. Ensuring food safety through good manufacturing practices (GMP) and proper training of food handlers, including butchers, is essential in preventing foodborne diseases (FBD). Detecting and evaluating risk parameters is crucial for identifying critical action points. Failure to address them can result in widespread contamination and severe public health consequences.

FundingThe present study was supported by PIDAE 2018-2019, UBACyT 2020 and 2022, Secretaria de Politicas Universitarias-Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We thank all the technical staff for their work in carrying out this work.