The Caatinga biome occurs only in Brazil; however, there is no survey on leptospirosis using direct and indirect diagnostic tests in this region with goats maintained in field conditions. We conducted a prospective survey with paired sampling to evaluate the importance of carrier goats in the maintenance of disease. Based on sampling calculation, 60 goats (30 confined and 30 extensively reared) were randomly selected and monitored for three months during the rainy season with paired monthly biological sample collections. The animals underwent urine and vaginal fluid collection for microbiological and molecular diagnosis, and serum samples for serological diagnosis using the microscopic agglutination test (MAT). Overall, 45 (75%) animals were positive in at least one diagnostic method. Anti-Leptospira spp. antibodies were detected in all three sampling moments in 43 (71.7%) animals, antibody titers varied from 25 to 800, and most frequent serogroups were Australis in the 1st and 2nd blood collections (66.7% and 40.7%, respectively) and Cynopteri in the 3rd collection (52.6%). None of the animals tested positive in the microbiological diagnosis or the vaginal fluid PCR; however, five (16.7%) animals were positive in the urine PCR only in the confined group in the first collection. Two DNA urine samples were sequenced, demonstrating 99% similarity with Leptospira interrogans. Different diagnostic techniques for leptospirosis in goats raised under Caatinga biome field conditions are suggested, as well as further studies over a longer period with monthly collections to better understand the prevalence of Leptospira spp. and its variation over time.

El bioma Caatinga se encuentra solo en Brasil; sin embargo, no existe para esta región ningún relevamiento sobre leptospirosis basado en pruebas diagnósticas directas e indirectas en cabras criadas en condiciones de campo. Para evaluar la importancia de las cabras portadoras en el mantenimiento de la enfermedad, se llevó a cabo un estudio prospectivo con muestreo pareado. Con base en el cálculo del tamaño muestral, se seleccionaron al azar 60 cabras (30 confinadas y 30 criadas extensivamente) para ser monitorizadas durante 3 meses, en la temporada de lluvias. Mensualmente se tomaron muestras pareadas de orina y de exudado vaginal para el diagnóstico microbiológico y molecular, y muestras de suero para el diagnóstico serológico mediante la prueba de aglutinación microscópica. En total, 45 (75%) animales fueron positivos en al menos un método de diagnóstico. Se detectaron anticuerpos anti-Leptospira spp. en los 3 momentos de muestreo en 43 (71,7%) animales, con títulos que variaron de 25 a 800. Los serogrupos más frecuentes fueron Australis en el primer y el segundo muestreo (66,7 y 40,7%, respectivamente) y Cynopteri en el tercer muestreo (52,6%). Todos los cultivos microbianos fueron negativos, al igual que los exudados vaginales evaluados por PCR, mientras que 5 muestras de orina resultaron positivas por PCR solo en el grupo confinado, en el primer muestreo. Se secuenció el ADN de 2 muestras de orina y se obtuvo un 99% de similitud con Leptospira interrogans. Para comprender mejor la prevalencia de Leptospira spp. y su variación en el tiempo en cabras criadas en condiciones de campo en el bioma Caatinga, se recomienda efectuar diferentes pruebas diagnósticas, así como estudios adicionales durante un período mayor de 3 meses, con recolecciones mensuales.

Leptospirosis is a worldwide spread zoonotic disease affecting companion, wild and farm animals. The infection causes economic losses to subsistence and industrial livestock10,44, has great impact on public health in addition to be strongly influenced by environmental components9,41. Currently, based on phylogenetic analyses, the genus Leptospira spp. is divided according to its level of pathogenicity into the following categories: saprophytic (26 species), intermediate (21 species) and pathogenic (17 species). Intermediate species share a nearly common ancestor with pathogenic species, although exhibiting moderate pathogenicity in humans and animals52. Pathogenic Leptospira spp. serovars generally have specific host preferences (e.g., serovar Hardjo and cattle, serovar Canicola and dogs, and serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae and rats), but these associations are not strict and the molecular basis for such host specificity is unknown38.

Goat farming is of great economic importance in several countries, including Brazil. It is an important source of protein and additional income for producers, especially in the Northeast region, where 94.5% of the national herd is located25. The disease has been identified as a possible adaptation of the agent to unfavorable environments, despite being generally associated with greater humidity and rainfall. Although goats raised in semiarid conditions are more resistant to infection, the spread of the disease has worsened on properties that engage in activities intercropped with other species37.

In acute goat leptospirosis the animals exhibit pyrexia, jaundice, anorexia and anemia or hemorrhagic syndromes. However, most infected animals present the chronic form of the disease, which is characterized by infertility, abortion, stillbirths and reduced milk production that result in significant economic losses11,15,30. The asymptomatic presentation in goats is the most commonly reported, and animals in this condition play an important epidemiological role, as they can act as sources of infection and facilitate the elimination of the agent within the herd, which may infect other animals and humans50. Leptospirosis is diagnosed using the microscopic agglutination test (MAT), which is the recommended test for serological diagnosis47. However, combining serology with molecular methods is strongly recommended in order to make the diagnosis more reliable and identify carrier animals even with negative serological results12,47.

The Caatinga biome is exclusive to the Brazilian territory and is characterized by dry forests, high temperatures and low humidity, as well as a broad biodiversity. The average temperature is 28°C, reaching 40°C in the hottest days, while the annual precipitation varies from 400 to 800mm, with a rainy period that lasts three to four months. This biome covers an area of 826411km2 (11% of the national territory) and is present in all the states of the Northeast region of Brazil, as well as part of the north of Minas Gerais. It has distinct vegetation, making it unique to the region and therefore offering epidemiological conditions that should be assessed differently from other regions of Brazil and the world2. Dry climate regions such as these, where the environment is often unfavorable, may influence the adaptability of Leptospira spp. by selecting alternative routes of transmission and determining a distinctive epidemiology36. There are several surveys of goat leptospirosis in the Caatinga biome using slaughtered animals; however, there is a lack of studies involving animals maintained under field conditions. In this study, we conducted a prospective survey with paired sampling to evaluate the prevalence of Leptospira spp. in goat herds reared under different systems in the Caatinga biome and the importance of carrier goats in the maintenance of disease.

Materials and methodsGoats and sample planningThe study was conducted on an experimental farm in the state of Pernambuco, in the Northeast region of Brazil. The goat herd on the property consisted of 200 goats of the Moxotó and Saanen breeds, 160 females (120 sexually mature) and 40 males, raised in confined and extensive management systems, and not vaccinated against leptospirosis. In addition to the goats, the property also housed sheep, cattle and horses. Only female goats that had reached sexual maturity were selected for the experiment, since the analysis of vaginal fluid at this age provides important data on genital transmission. Although reproductive failure was not a selection criterion for the study, the herd had a history of reproductive problems, such as abortions, stillbirths, repeated estrus and malformations.

The minimum sample size required was calculated using the formula to analyze proportions1:

where n=minimum sample size; Zα/2=1.96 (Z value for a 95% confidence level); Z1−β=1.64 (Z value for the power of 95%); P0=32.4% (reference proportion of PCR positivity)21; P1=75% (estimate of experimental proportion of PCR positivity)22; q0=1−p0; q1=1−p1.

Based on these parameters, 60 goats (30 confined and 30 extensively reared) were randomly selected on February 1, 2023. These animals were monitored for three months (March, April and May), during the rainy season with paired monthly biological sample collections. The diagnostic tests were conducted in the Communicable Disease Laboratory of the Federal University of Campina Grande, Patos, Paraíba state, Brazil.

Sample collectionThe selected animals underwent urine and vaginal fluid (VF) collection for subsequent microbiological and molecular diagnosis, with duplicate samples being collected for each animal. After an injection of 5mg/kg of furosemide (Fraga, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil), urine samples were collected by spontaneous urination. VF collection was performed using sterile swabs directly from the dorsal vestibule of the vagina. DNA- and RNA-free microtubes containing 0.5ml of phosphate-buffered saline were used to store urine and VF samples and kept at room temperature until transported to the laboratory and stored at −20°C until PCR was performed up to 24h after collection. Blood samples were collected by puncture of the jugular vein using properly identified sterile tubes with a capacity of 8ml. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 1512g for 10min and the serum samples were stored at −20°C until serology was performed.

Leptospira spp. serologyThe serological diagnosis of leptospirosis was run using the microscopic agglutination test (MAT). Overall, 24 serovars belonging to 17 pathogenic serogroups of five Leptospira spp. species were used as antigens: serovars Kennewicki, Hebdomadis, Pyrogenes, Copenhageni, Shermani, Canalzoni, Javanica, Canicola, Autumnalis, Wolffi, Hardjoprajitno, Icterohaemorrhagiae, Pomona, Bratislava, Australis, Guaricura, Tarassovi, Ballum, Mini, Castellonis, Grippotyphosa, Cynopteri, Panama and Louisiana53. Sera were screened at 1:25 dilution, and antibody titers were determined as the highest dilution with at least 50% of agglutinated leptospires. Animals were deemed positive when they presented reciprocal titers ≥25.

Leptospira spp. cultivationImmediately after collection, the vaginal swab (VF swab) and urine (100μl) were transferred separately to tubes containing 5ml of EMJH semisolid medium (Difco, BD Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), enriched with an antibiotic cocktail: 5-fluorouracil (1mg/ml), fosfomycin (4mg/ml), sulfamethoxazole (0.4mg/ml), amphotericin B (0.05mg/ml), and trimethoprim (0.2mg/ml) (named STAFF cocktail). The tubes were incubated at 28°C for 24h under biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) conditions. After this period, the cultures were transferred to new tubes with EMJH semisolid medium, but without antibiotics, and incubated again under the same BOD conditions. Cultures were then examined weekly for 12 weeks by dark-field microscopy.

Leptospira spp. molecular detection and sequencingThe Dneasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used for DNA extraction from VF and urine according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The molecular detection (polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) was performed as previously described22. To amplify the LipL32 gene (specific for pathogenic leptospires), primers LipL32-45F (5′-AAG CAT TAC CGC TTG TGG TG-3′) and LipL32-286R (5′-GAA CTC CCA TTT CAG CGA TT-3′) were used48. Positive and negative controls were Leptospira interrogans serogroup Pomona serovar Kennewicki (kindly provided by the Fluminense Federal University, Niteroi, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and ultrapure water, respectively.

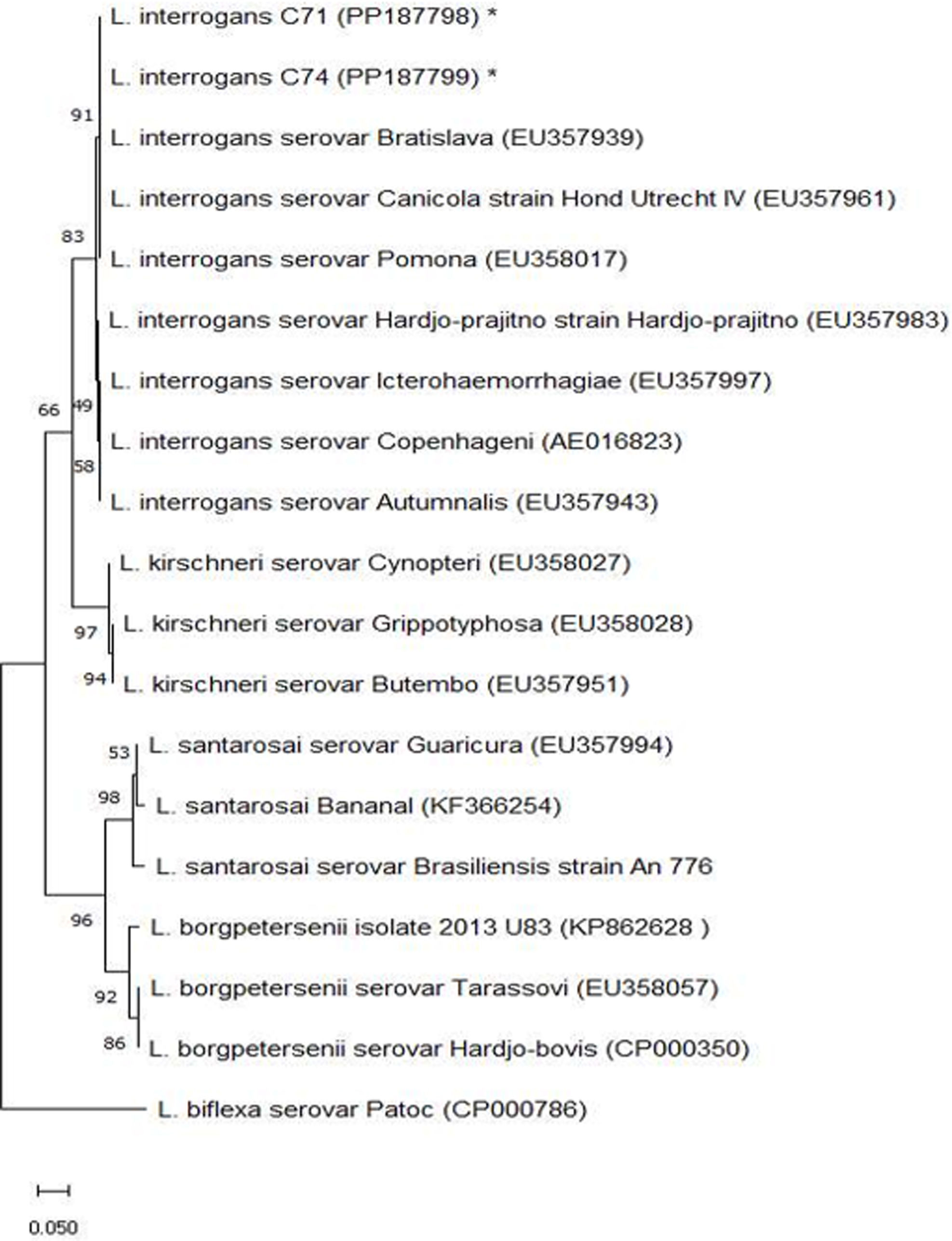

The Big Dye Terminator v3.1 Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used for sequencing with primers LipL32-45F and LipL32-286R48. Capillary electrophoresis was run on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer and POP-7 polymer39, and the Bio Edit editor20 was used for sequence alignment. Dataset strings were obtained from GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, USA) (http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov) with the BLAST tool (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Seaview4 software17 was applied for the phylogenetic analysis, and the neighbor-joining model-based phylogenetic tree was constructed with a bootstrap value of 1000 replications, visualized through FigTree v1.4.3 (http://tree .bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Sequences of Leptospira spp. were included in the phylogenetic reconstruction.

Data analysisThe comparison of the frequencies of positive animals in the serology, urine PCR, and vaginal fluid PCR were carried out as follows: (i) comparison of biological material per collection period; (ii) comparison of collection periods per biological material; (iii) comparison of confined and extensive animals per collection period and biological material. For this purpose, a mixed-effect model with repeated measures and multiple comparisons by the Bonferroni test was built considering the collection periods as within-subject effects and the group (confined/extensive) as between-subject effect. The analyses were conducted in the R environment40, with the RStudio interface and rstatix package26, and the significance level was 5% (p≤0.05).

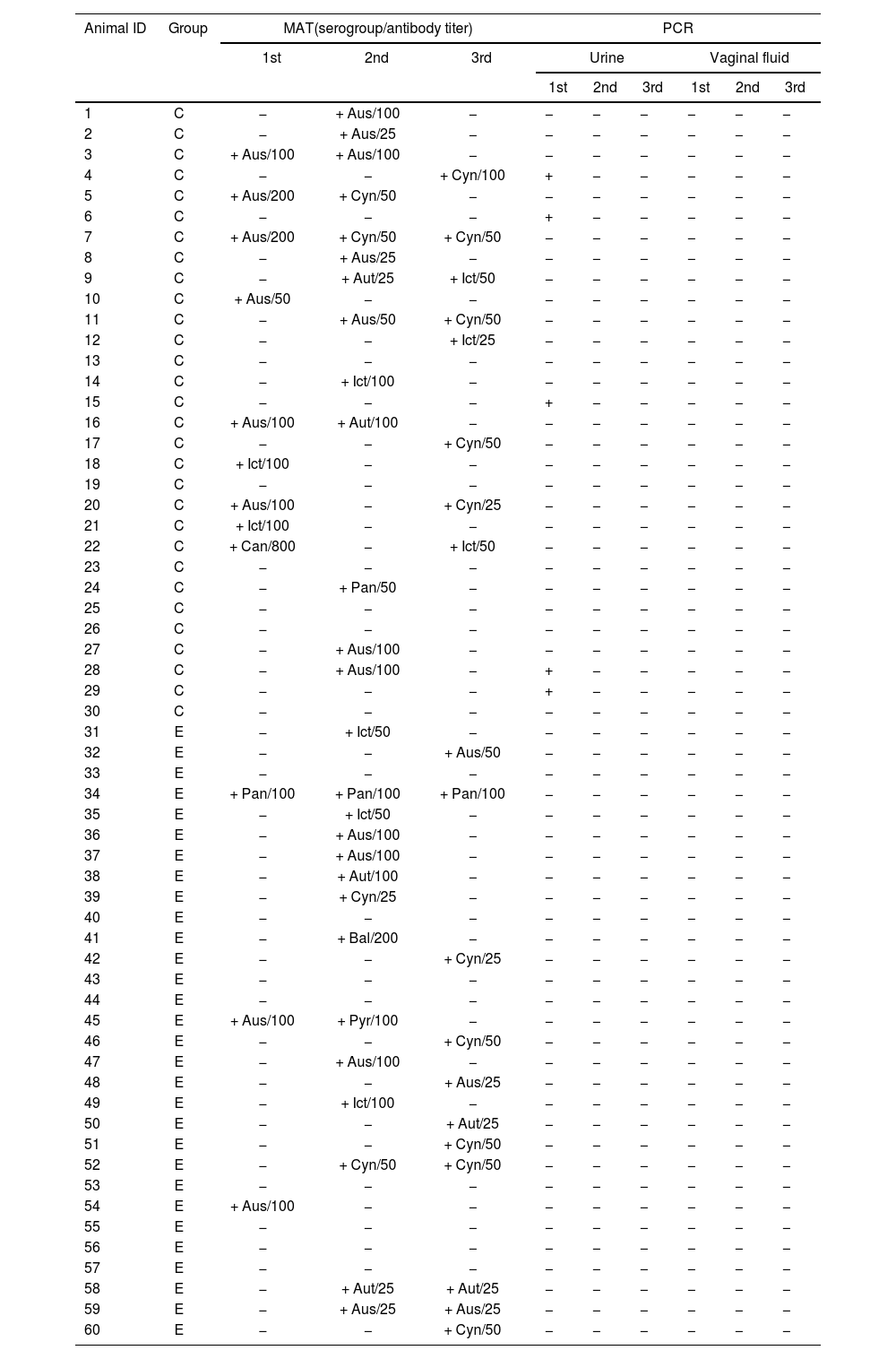

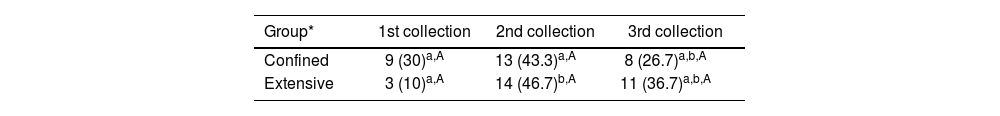

ResultsSerological resultsOverall, 45 (75%) animals were positive in at least one diagnostic method (Table 1). Anti-Leptospira spp. antibodies were detected in all three sampling moments in 43 animals (71.7%; 58 cases; 12: 1st collection, 27: 2rd collection, 19: 3rd collection), and antibody titers varied from 25 to 800. Most frequent serogroups were Australis in the 1st and 2nd blood collections (66.7% and 40.7%, respectively) and Cynopteri in the 3rd collection (52.6%). The higher seropositivity (45%) was found in the 2nd collection (Table 2) for both confined and extensive groups. Seven confined animals and one extensive animal showed antibody titers for different Leptospira spp. serogroups. There was an effect of the collection period (p=0.016) and proportions for 1st and 2nd collections were statistically different (p=0.006) in extensive animals, however, there was not statistical difference between confined and extensive animals in any moment (p>0.05).

Results of MAT, PCR and bacterial growth of Leptospira spp. in goats raised in confined and extensive systems in the Caatinga biome, Brazil, according to biological materials and collection periods (1st, 2nd and 3rd).

| Animal ID | Group | MAT(serogroup/antibody titer) | PCR | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Urine | Vaginal fluid | ||||||

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||||

| 1 | C | − | + Aus/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | C | − | + Aus/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3 | C | + Aus/100 | + Aus/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4 | C | − | − | + Cyn/100 | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 5 | C | + Aus/200 | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 6 | C | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 7 | C | + Aus/200 | + Cyn/50 | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8 | C | − | + Aus/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 9 | C | − | + Aut/25 | + Ict/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 10 | C | + Aus/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 11 | C | − | + Aus/50 | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 12 | C | − | − | + Ict/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 13 | C | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 14 | C | − | + Ict/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 15 | C | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 16 | C | + Aus/100 | + Aut/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 17 | C | − | − | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 18 | C | + Ict/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 19 | C | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 20 | C | + Aus/100 | − | + Cyn/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 21 | C | + Ict/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 22 | C | + Can/800 | − | + Ict/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 23 | C | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 24 | C | − | + Pan/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 25 | C | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 26 | C | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 27 | C | − | + Aus/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 28 | C | − | + Aus/100 | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 29 | C | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| 30 | C | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 31 | E | − | + Ict/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 32 | E | − | − | + Aus/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 33 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 34 | E | + Pan/100 | + Pan/100 | + Pan/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 35 | E | − | + Ict/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 36 | E | − | + Aus/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 37 | E | − | + Aus/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 38 | E | − | + Aut/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 39 | E | − | + Cyn/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 40 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 41 | E | − | + Bal/200 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 42 | E | − | − | + Cyn/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 43 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 44 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 45 | E | + Aus/100 | + Pyr/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 46 | E | − | − | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 47 | E | − | + Aus/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 48 | E | − | − | + Aus/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 49 | E | − | + Ict/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 50 | E | − | − | + Aut/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 51 | E | − | − | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 52 | E | − | + Cyn/50 | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 53 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 54 | E | + Aus/100 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 55 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 56 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 57 | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 58 | E | − | + Aut/25 | + Aut/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 59 | E | − | + Aus/25 | + Aus/25 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 60 | E | − | − | + Cyn/50 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

C: confined; E: extensive; Aus: Australis; Aut: Autumnalis; Bal: Ballum; Cyn: Cynopteri; Ict: Icterohaemorrhagiae; Pan: Panama; Pyr: Pyrogenes; +: positive; −: negative.

Number and frequency (%) of goats from the Caatinga biome seropositive for Leptospira spp. by MAT according to the collection period and group.

| Group* | 1st collection | 2nd collection | 3rd collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confined | 9 (30)a,A | 13 (43.3)a,A | 8 (26.7)a,b,A |

| Extensive | 3 (10)a,A | 14 (46.7)b,A | 11 (36.7)a,b,A |

Total number of samples per group=30; in the same row, proportions with different superscript lowercase letters indicate statistical difference (p<0.05) between collections; in the same column, proportions with different superscript capital letters indicate statistical difference (p<0.05) between groups.

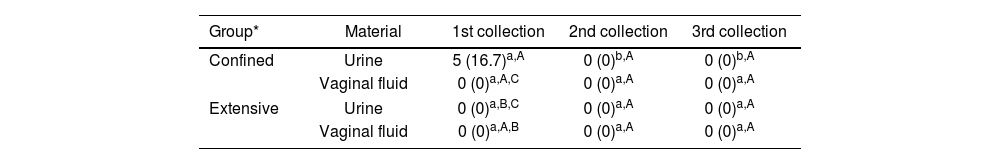

All samples were negative by microbiological culture, and most culture samples exhibited high contamination. Only five animals were positive for leptospirosis by PCR; the diagnosis was made in the confined group from urine samples during the first collection (Table 3). All PCR-positive animals were seronegative by MAT in the same collection. Two DNA samples of urine were sequenced, demonstrating 99% similarity with L. interrogans (Fig. 1).

Number and frequency (%) of goats from the Caatinga biome positive for Leptospira spp. by PCR according to the collection period and group.

| Group* | Material | 1st collection | 2nd collection | 3rd collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confined | Urine | 5 (16.7)a,A | 0 (0)b,A | 0 (0)b,A |

| Vaginal fluid | 0 (0)a,A,C | 0 (0)a,A | 0 (0)a,A | |

| Extensive | Urine | 0 (0)a,B,C | 0 (0)a,A | 0 (0)a,A |

| Vaginal fluid | 0 (0)a,A,B | 0 (0)a,A | 0 (0)a,A | |

Total number of samples per group=30; in the same row, proportions with different superscript lowercase letters indicate statistical difference (p<0.05) between collections; in the same column, proportions with different superscript capital letters indicate statistical difference (p<0.05) between groups.

The survey presented some logistical and budgetary limitations. A 12-month follow-up period covering the rainy and dry seasons would be more comprehensive to verify the possible influence of season on serology and PCR results. Although the aim of the survey was to follow-up animals (paired sampling) to verify the importance and maintenance of Leptospira spp. carriers in the transmission of leptospirosis in goats under field conditions, the study lacks a proper control group from a non-endemic area, which would have strengthened the interpretation of results, especially regarding the prevalence of infection in the Caatinga biome. In addition, the use of end-point PCR instead of the more sensitive real-time PCR method could have affected the results. Similarly, the characterization of the identified strains by MLST or whole genome sequencing could have provided additional information. Despite these difficulties, it was possible to follow-up 60 animals with 75% of the animals showing positive results in at least one diagnostic test throughout the experiment, without compromising the minimum number of animals required by the sample size calculation.

To our knowledge, this is the first follow-up investigation on Leptospira spp. infection in goats maintained under field semiarid conditions in Brazil. The use of different diagnostic methods for leptospirosis enabled a better assessment of the herd, since 75% of the animals investigated were positive in at least one diagnostic test. There was a higher proportion of positive animals using serology (71.7%) compared to PCR (6.7%), and all five PCR-positive animals were negative by MAT in the 1st collection. The higher proportion of positivity for PCR is due to the fact that in some cases, depending on the serovar-host interaction as well as individual host responses, leptospires have low antigenicity3 and, moreover, the infection may be in the chronic phase. Thus, a seronegative animal is not always free of infection36. The search for Leptospira spp. DNA from total blood samples should be a suitable attempt to detect goats in the leptospiremia phase. Leptospira spp. DNA has been successfully detected in goats13 and camels42. Thus, the detection of Leptospira spp. in blood and urine could suggest that the animals were in leptospiremia and leptospiruria phases respectively, i.e., they could hypothetically yield leptospires, thus contaminating the environment or directly infecting other animals and humans.

These findings reinforce the association of MAT with direct diagnostic techniques, such as PCR, for assessing the epidemiological situation of infection in herds27. Usually, the cut-off used in Leptospira spp. serology for livestock is an antibody titer ≥10011. In this survey, the cut-off point used was ≥25, which has been proved to increase the serology sensitivity values in ewes maintained under field semiarid conditions42, and this may justify the discrepancy between serology and PCR results. Moreover, lower values of PCR positivity have been shown in ewes slaughtered in the rainy season in the Brazilian semiarid36.

Recently, worldwide investigations have detected serovars Pomona, Australis, and Tarassovi in goats, while Australis, Tarassovi, Bratislava, Grippothyphosa, and Hebdomadis were detected in sheep species15,19,51. The most frequent serogroups in this study were Australis (1st and 2nd collections) and Cynopteri (3rd collection). Although scarcely cited by other authors in goats, different serogroups of leptospires are prevalent in specific regions, and are associated with one or more maintainer hosts that serve as reservoirs of infection5. The Australis serogroup is often found in horses and pigs without causing clinical signs15, whereas sheep may act as maintenance or accidental hosts depending on the region and breeding conditions34. The presence of antibodies against the Autralis serogroup in the goats studied may be related to sheep, horses and cattle sharing the same environment with goats, since there is an association between certain species and specific serogroups19.

To date, there is no confirmatory evidence on the animal reservoir, as well as the environmental determinants associated with the transmission of the Cynopteri serogroup, the second most frequent in this study. However, it has been identified in humans49 and in domestic cats35. Although it has been detected in goats14, information on its prevalence in the species is scarce.

In this study, low antibody titers prevailed, in agreement with the research carried out by Ciceroni et al.7, who examined 218 goats in Bolivia and found titers of 200 or less. Schmidt et al.45 conducted a study on dairy goats in Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil, and found antibody titers below 400. Arduino et al.3 reported that leptospires are antigens with low immunological response and for a short period of time. The pattern of antibody titers found in this study suggests that the infections were not recent or that goats may be resistant to the serogroups to which they reacted45.

It was expected that all PCR-positive samples would also show leptospire growth, but despite all efforts to avoid contamination, the collection of biological material in the field caused a high rate of contamination of the cultures, even with the cleanliness of the collection environment and the use of antibiotics (STAFF cocktail) in the culture media, which may have contributed to the discrepancy between the PCR and bacteriological culture results8,16. Contaminant control remains a critical point of leptospire isolation, for which several formulae with antibiotics have been proposed, and the STAFF cocktail has been demonstrated to be efficient for soil samples6 and also for bovine clinical samples33 in control contaminants. However, STAFF completely inhibited Leptospira borgpetersenii growth in EMJH culture medium, and T80/40/LH medium+STAFF combination proved to be the best choice for growth, being recommended for obtaining a higher number of Leptospira spp. strains from bovines31. Urine collection methods such as suprapubic puncture or catheter collection are mechanisms that need to be taken into account in further studies in order to reduce the possibility of environmental contamination.

There was molecular detection of Leptospira spp. in five urine samples (16.7%), and no sample was positive in the PCR of genital fluid. The incidence of leptospirosis is strongly associated with periods of high rainfall43; however, in studies carried out with small ruminants slaughtered in the Brazilian semiarid region, the Caatinga biome28,47, there was greater positivity in PCR in the period of low rainfall compared to the period of higher rainfall, especially in biological materials from the reproductive system. In this study, the positivity found in the rainy season may suggest a greater variety of serogroups and variation in circulating strains, which may be related to the non-identification of PCR positivity in VF in the study period and the indirect transmission of the agent being predominant, especially in the rainy season28,46. However, comparisons covering several seasonal periods would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis. It is also possible that the low positive PCR results were due to the low concentrations of leptospires in urine, which may be below the PCR detection limit when animals are chronically infected with adapted serovars28. Moreover, the time between sample collection and processing may have influenced the PCR results.

All five urine PCR-positive animals were seronegative by MAT, but there was a higher proportion of serology positivity compared to PCR and this disagreement between serological and molecular results is common11, reinforced by the hypothesis that, although serology is very useful for herd diagnosis, it may be an insufficient tool for identifying individual carriers, as a seronegative animal is not always free of infection, and detection of the presence of the agent is necessary to identify and treat the animal safely18.

In surveys on leptospirosis in sheep in the Caatinga biome, in which direct and indirect diagnostic tests were used, the animals came from slaughterhouses, with no reproductive or health history28,47. This study was conducted with animals raised in an extensive management system where the animals were free to graze and their production was destined for meat commercialization, and for confined animals the feed and environment were controlled, and the breeding was destined for dairy production. The study period was rainy and no animal showed clinical signs of acute systemic leptospirosis, and the herd was not vaccinated against leptospirosis. Animals have been introduced to the property, and although there is a dam around the property, there is no history of flooding in recent years. No investigation into the causes of reproductive problems in goats had been carried out on the property until this study, and there are risk factors such as the presence of rodents and wild animals near the facilities and the absence of an adequate vaccination program that can predispose to the occurrence of reproductive diseases such as leptospirosis.

The occurrence and transmission of Leptospira spp. in a given habitat are conditioned by the results of synergistic and antagonistic effects of numerous variables. Confined and extensive animals in the 1st collection were statistically different (p=0.019) regarding urine PCR positivity, which may be linked to specific characteristics of each group. The high density of confined animals facilitates the rapid transmission of pathogens due to the close and constant contact among animals, in addition to having less interaction with the external environment11. Moreover, factors such as the characteristics of the infectious agent, susceptibility of hosts, animal demographics, movement patterns and environmental conditions that facilitate the maintenance and multiplication of infectious agents are important factors to consider when seeking to understand the dynamics of animal infectious disease transmission23.

Sequencing of the PCR product was possible in two animals, and the samples showed 99% similarity to L. interrogans. This species is part of the group involved in the pathogenesis of leptospirosis, being responsible for infection in domestic animals and humans27, and the success of this species as a pathogen is due to its ability to evade the host's immune system38. The different serovars of L. interrogans do not show host specificity, but the preference of specific serovars for certain vertebrates has been observed. L. interrogans is one of the most important pathogenic species and is frequently associated with reproductive disorders in ruminants4,32. The importance of identifying L. interrogans lies in its ability to survive in adverse conditions and its capacity to disperse in herds through animal trade, generating a transmission cycle that may not be dependent on hosts or environmental contamination29,37,49. From an epidemiological point of view, knowledge of Leptospira spp. species is essential for the adoption of appropriate and integrated management measures, thus serving as a basis for the construction and application of strategies for the prophylaxis and control of this disease24.

In conclusion, it was possible to detect the presence of the Cynopteri serogroup, which has rarely been reported in goats, and a sequenced urine sample showed 99% similarity to L. interrogans. In addition, only in the first month of collection there were PCR-positive animals, showing the importance of using different diagnostic techniques for leptospirosis in goats raised in Caatinga biome field conditions for a better evaluation of the herd and identification of carrier animals. Further studies over a longer period with monthly collections are suggested to better understand the prevalence of Leptospira spp. and its variation over time.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMayla de Lisbôa Padilha: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, and Writing – original draft. Lídio Ricardo Bezerra de Melo, Clécio Henrique Limeira, Nathália Maria de Andrade Magalhães, Maria Luana Cristiny Rodrigues Silva and Rafael Rodrigues Soares: Investigation and Methodology. Clebert José Alves and Severino Silvano dos Santos Higino: Investigation, Methodology and Writing – review & editing. Carolina de Sousa Américo Batista Santos: Data curation, Investigation, and Methodology. Sérgio Santos de Azevedo: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, and Writing – review & editing.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Ethical disclosuresThe present study had its ethical procedures approved by the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals (CEUA) of Universidade Federal de Campina Grande (UFCG) under protocol number 37/2023.

FundingThis study was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), grant numbers 302222/2016-2 and 423836/2018-8, and Research Support Foundation of the State of Paraíba (FAPESQ), grant numbers 46360.673.28686.05082021 and 54758.924.28686.25102022.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Data availabilityData are available on request from the corresponding author.