Edited by:

Diego Sauka - Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina

Leopoldo Palma - Universidad de Valencia, Spain

Johannes Jehle - Julius Kühn-Institut, Institute for Biological Control, Germany

Last update: October 2025

More infoFungal diseases in agricultural crops cause economic losses, with chemical control being the conventional method to manage them. However, this approach negatively impacts both the environment and human health. This study focused on endophytic fungi isolated from the roots of Ceratozamia mirandae in the Mexican locality of Juan Sabines (Villa Corzo, Chiapas). These fungi were identified morphologically and molecularly, biochemically characterized, and evaluated for their antagonistic activity against Colletotrichum karstii, Neopestalotiopsis sp. and Fusarium oxysporum. Their potential for promoting growth in Arabidopsis thaliana and tomato, as well as protecting against Botrytis cinerea, was also assessed. Fourteen fungal isolates were identified and grouped into six genera: Fusarium, Pestalotiopsis, Trichoderma, Umbelopsis, Nectria and Podospora. Among these Fusarium proliferatum JS311 and F. oxysporum JS239 exhibited strong inhibitory effects against the tested pathogens. Eight isolates were found to produce indole-3-acetic acid, promoting the growth of A. thaliana and tomato plants. Notably, F. oxysporum JS439 and F. solani (JS240, JS256 and JS4101) exhibited additional capabilities, including siderophore production and growth in nitrogen-free media. All Fusarium endophytic isolates induced systemic resistance against B. cinerea in tomato. Endophytic fungi from C. mirandae show promising potential as biofertilizers due to their combined mechanisms of anti-phytopathogenic activity, plant growth promotion, and systemic resistance induction through the production of beneficial metabolites.

Las enfermedades fúngicas causan pérdidas económicas en los cultivos agrícolas, y el control químico es el método principal para reducirlas. Sin embargo, este enfoque repercute negativamente tanto en el ambiente como en la salud humana. Este estudio se centró en hongos endófitos aislados de las raíces de Ceratozamia mirandae de muestras obtenidas en la localidad mexicana de Juan Sabines (Villa Corzo, Chiapas). Los hongos aislados se identificaron morfológica y molecularmente, se caracterizaron bioquímicamente y se evaluó su actividad antagonista frente a Colletotrichum karstii, Neopestalotiopsis sp. y Fusarium oxysporum. También se estudió su potencial para promover el crecimiento de Arabidopsis thaliana y tomate, así como el efecto protector frente a Botrytis cinerea. Se identificaron catorce hongos agrupados en seis géneros: Fusarium, Pestalotiopsis, Trichoderma, Umbelopsis, Nectria y Podospora. Entre ellos, Fusarium proliferatum JS311 y F. oxysporum JS239 mostraron fuertes efectos inhibidores contra los patógenos evaluados. Ocho aislados produjeron ácido indol-3-acético y promovieron el crecimiento de A. thaliana y tomate. En particular, F. oxysporum JS439 y F. solani JS240, JS256 y JS4101 mostraron capacidades adicionales, incluyendo la producción de sideróforos y el crecimiento en medios libre de nitrógeno. Todos los aislados de Fusarium indujeron resistencia sistémica contra B. cinerea en tomate. Los hongos endófitos de raíces de C. mirandae presentan un potencial prometedor como biofertilizantes debido a sus mecanismos combinados de actividad antifitopatógena, promoción del crecimiento vegetal e inducción de resistencia sistémica mediante la producción de metabolitos benéficos.

Agricultural pests and diseases annually reduce global crop yields by 30–50%, with chemical control remaining the most widely used method in modern agriculture13. However, excessive reliance on chemical inputs has led to significant challenges, including the development of resistance in pathogens and pests, loss of biodiversity, soil degradation, harm to beneficial fauna, and adverse effects on human and animal health22.

The use of endophytic microorganisms (EMs) in biofertilizers has emerged as an effective and sustainable strategy to enhance agricultural productivity. EMs control diseases caused by pathogens and suppress pest damage, reduce dependence on chemical inputs, mitigate ecological impacts, and improve crop yield and quality15. Recent studies highlight the potential of EMs as biofertilizers in agriculture. For instance, Khan et al17. demonstrated that Acremonium strains isolated from Lilium davidii exhibited antifungal activity, promoted the growth of Allium tuberosum, and produced plant growth-promoting substances such as 3-indolacetic acid (IAA), siderophores, organic acids and solubilized phosphates. Similarly, EMs from the genera Alternaria, Didymella, Fusarium and Xylogone isolated from Sophora flavescens were shown to enhance primary root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana while producing IAA, siderophores and solubilized phosphates43. Species of the genus Trichoderma have also been widely utilized as biological control agents due to their ability to confer resistance against plant pathogens and increase the productivity of economically important crops32. These findings underscore the promising role of EMs in sustainable agriculture, offering an eco-friendly alternative to conventional chemical-based practices.

EMs reside within plant tissues during part or all of their life cycle, offering their host plants a wide range of biological benefits15. The primary effects of EMs include enhanced stress tolerance by increasing resilience to abiotic stressors, such as acidity, salinity, heavy metals, drought, floods, extreme temperatures, as well as biotic stressors like pathogens, insects and herbivores41. EMs also promote plant growth through the production and secretion of plant hormones such as gibberellins and auxins, solubilizing essential nutrients in the soil including phosphate and iron, to make them more available to plants11,13, and facilitating nitrogen transfer to plants through strains that express ACC deaminase, which are up to 40% more efficient at forming nitrogen-fixing nodules12. Additionally, EMs induce systemic defense mechanisms in plants by producing antifungal and antibiotic secondary metabolites that inhibit pathogen development and compete for space and nutrients, thereby protecting the plant13,15.

The rhizosphere serves as a prolific source of rhizospheric or endophytic microorganisms; it is estimated that over one million EMs species, including bacteria and fungi, are associated with approximately 300000 plant species10. However, studies suggest that the diversity of endophytic communities associated with various plant species remains significantly underestimated6,42. For example, Ulloa-Muñoz et al.45 isolated EM species from native and endemic plants of the Cordillera Blanca in the Peruvian Andes, demonstrating their potential to promote crop growth and control pathogen.

These findings suggest that wild plants endemic to conserved areas harbor a vast diversity of EMs. Therefore, this study aims to characterize endophytic fungi associated with the roots of Ceratozamia mirandae (Pérez, Vovides & Iglesias Amenduai)29 (Cycadales: Zamiaceae), an endemic species of Chiapas, Mexico, focusing on their biocontrol potential against fungal phytopathogens, their ability to promote plant growth, and their capacity to induce systemic resistance in tomato seedlings against Botrytis cinerea.

Materials and methodsStudy areaSamples of healthy secondary roots of C. mirandae were collected in the Natural Resource Protection Reserve “La Frailescana”, located in the locality of “Juan Sabines” within the municipality of Villa Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico (16°03′20.5″N; 93°28′41.6″W, at an altitude of 1817m above sea level).

Sampling and isolation of endophytic fungiHealthy roots of C. mirandae were collected from a depth of 10cm, carefully wrapped in kraft paper, and transported in polyethylene bags to the Laboratory of Biofertilizers and Bioinsecticides at the University of Sciences and Arts of Chiapas (UNICACH-Villa Corzo campus). The roots were cut into 10mm explants using a scalpel, then surface-disinfected with 70% ethanol for 3min, followed by 10% sodium hypochlorite for 10min, and finally rinsed twice with sterile distilled water. The disinfected explants were placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium and incubated at 28°C for 48h. Emerging fungal colonies were isolated and purified using the hyphal tip technique.

Morphological and molecular identificationFungal isolates were first identified morphologically by observing their reproductive structures using an Axiolab Carl Zeiss® compound microscope and following dichotomous keys for fungal taxonomy46. For molecular identification, genomic DNA was extracted from the isolates according to the protocol described by Raeder and Broda33. The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of 18s rDNA was amplified and sequenced using the ITS5 (5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’) and ITS4 (5′-TCTCCTCCGCTTATTGATATATGC-3′) primers47. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplicons were sequenced using the Sanger method on an ABI sequencer (Applied Biosystem)1. The resulting sequences were compared with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database using the BLAST algorithm and aligned using CLUSTAL W in MEGA7® software. GenBank accession numbers were obtained for the submitted sequences42.

In vitro dual confrontation bioassaysFirst, a screening bioassay was performed to evaluate the antagonistic activity of endophytic fungi (EF) using Colletotrichum karstii as a model; the isolates that exhibited notable antagonistic responses were used for further assays against other fungi. The antagonistic EF were evaluated against C. karstii and Neopestalotiopsis sp., foliar pathogens of camedor palm38, and Fusarium oxysporum coffee (FoC), a coffee seedling pathogen donated by the Laboratory of Biofertilizers and Bioinsecticides of UNICACH-Villa Corzo. Pathogen explants were placed at one end of a Petri dish containing PDA, while EF explants were placed at the opposite end. The plates were incubated at 28°C for 8 days (d). Mycelial growth inhibition (MGI) of the pathogen was calculated using the formula [(R−r)/R]×100, where R is the control pathogen growth and r is the pathogen growth in confrontation34. A completely randomized design with four replicates per EF was used.

Characterization of fungi with plant growth-promoting activityThe plant growth-promoting activity of C. mirandae endophytic isolates were assessed on three-day-old A. thaliana Ecotype Col-0 seedlings. Each experiment included four replicates, with five seedlings per replicate. Seedlings were placed on the surface of Petri dishes containing Murashige and Skoog (MS) culture medium, with EF explants positioned at the bottom. Plates were maintained under a 16h light/8h dark photoperiod at 25°C for 12 d and monitored daily until the roots contacted the fungal growth36. Morphological changes in root architecture and aerial parts were considered positive indicators of growth promotion.

Biochemical characterization of fungi with plant growth-promoting activityDetection of 3-indolacetic acidIAA production was determined using the protocol by Ponce de León31. Five-day-old EF explants pre-cultured on PDA were incubated in test tubes with nutrient broth supplemented with l-tryptophan (150g/l) under constant shaking (1800rpm) at 28±1°C for 7 d. Supernatants from centrifuged cultures (13000g, 15min) were mixed with Salkowski's reagent (100ml of 35% perchloric acid and 2ml of 0.5M ferric chloride) and incubated in the dark for 30min. A color change from yellow to pink indicated IAA production, which was quantified at 530nm using a Thermo Scientific® Evolution™ 300 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Absorbance values were compared to an IAA calibration curve (0–0.1mg/ml)31.

Detection of siderophoresEF were inoculated on plates containing solidified Cromoazurol S (CAS) medium, as described by Louden et al.20. Plates were incubated at 28±1°C for 7 d in darkness. Isolates displaying orange halos around the colonies were identified as siderophore producers.

Growth in nitrogen-free media assayEF were grown on nitrogen-free Ashby culture medium (20g sucrose, 0.2g K2HPO4, 0.2g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.2g NaCl, 0.1g K2SO4, 5.0g CaCO3, and 15g agar per liter). Plates were incubated at 28±1°C for 7 d. EF that grew on this medium were considered positive for growth in nitrogen-free media7.

Phosphate solubilization assayPhosphate solubilization was evaluated using NBTRIP medium (10g glucose, 5g Ca3(PO4), 5g MgCl2-6H2O, 0.25g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.20g KCl, 0.1g (NH4)2SO4 and 15g agar per liter). EF explants were inoculated and incubated in darkness at 28±1°C for 7 d. Clear halos around the colonies indicated phosphate solubilization24.

Tomato growth promotion bioassayBlack 96-cavity Hydroenviroment® germination trays filled with CosmoPeat® peat moss substrate were used. Solanum lycopersicum var. Pomodoro (USAgriseeds®) seeds were sown at a 3mm depth and subjected to the following treatments: T1 – absolute control (water), T2 – negative control with F. oxysporum tomato strain (FoT), T3 – positive control I (50% N, 1.63kg/ha), T4 – positive control II (100% N, 3.23kg/ha), T5–T12 – treatments with isolates JS286, JS240, JS414, JS439, JS4101, JS296, JS285, and JS256, respectively.

A non-growth-promoting pathogenic tomato strain of F. oxysporum (FoT) was used as a negative control. Seeds were inoculated with 20μL of 1×106conidia/ml of each EF isolate at sowing, applied directly to the seeds, followed by a second inoculation 5 d post-emergence, applied directly to the base of the stem using a micropipette.

Fertilization with Fertiquim® urea, based on a planting density of 41666plants/ha, was applied using a 50% nitrogen dose in plant–EF interactions (T2, T5–T12)25 to evaluate the capacity of EF isolates to promote growth under nitrogen deficiency. Seedlings were maintained under semi-controlled conditions with 50% shade and irrigated to prevent leaching.

A completely randomized design with eight replicates per treatment was used. At 30 d post-planting (dpp), destructive analyses were performed to measure stem diameter (SD, mm), root length (RL, cm), seedling height (SH, cm), seedling fresh weight (SFW, mg), root fresh weight (RFW, mg), seedling dry weight (SDW, mg), root dry weight (RDW, mg), and leaf chlorophyll content (μmol/m2/s).

Morphological traits (SD, RL, SH) were measured using an Adeske® electronic vernier caliper. SD was measured 3cm from the stem base; RL from the stem base to the main root tip; and SH from the stem base to the terminal bud. Biomass variables (SFW and RFW) were recorded by separately weighing the stem and roots using a Velab® analytical scale. Dry biomass variables (SDW and RDW) were determined after drying samples at 70°C for 72h in a Thermo Scientific® oven. Chlorophyll content was measured using a Quantum Flux Apogee® sensor placed at the center of seedling leaves25.

Bioassays of systemic protection against B. cinerea induced by endophytic fungi of C. mirandae on tomato plantsThirty-day-old leaves of S. lycopersicum var. Pomodoro (USAgriseeds) seedlings, produced in an independent experiment under the same conditions as described for the growth promotion bioassay, were inoculated with 20μl of the necrotrophic fungus B. cinerea (a pathogenic tomato strain obtained from the Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo CIAD-Unidad Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua) at a concentration of 1×106conidia/ml. The conidia were resuspended in water containing Break-Thru® (BASF) at 0.1% and applied directly to the leaves with a micropipette37. A completely randomized design with six replicates per treatment was employed, with three leaves inoculated per seedling. Seedlings were maintained in a greenhouse for 7 d at 26±2°C. Leaf lesions were measured using ImageJ software, calibrated with a scale for accuracy39. The percentage of disease severity was calculated using the formula (% severity=damaged area/total area×100)27.

Statistical analysisData were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test (p≤0.05), using the MINITAB19® statistical software. Experiments were conducted in duplicate at separate times to ensure reproducibility.

ResultsIdentified endophytic fungiThe ITS sequences (ITS4–ITS5) of the EF showed similarities ranging from 94 to 100% in the GenBank database. These sequences were submitted with the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), where unique accession numbers were assigned (Table 1). A total of 14 EF isolates associated with C. mirandae were identified, representing the genera Fusarium, Pestalotiopsis, Trichoderma, Umbelopsis, Nectria and Podospora. Based on morphological and molecular analyses, these fungi were classified into three classes: Sordariomycetes, Euascomycetes and Zygomycetes (Table 1).

Diversity of root endophytic fungi associated with C. mirandae: morphological and molecular identification using ITS marker sequencing and GenBank accession.

| Endophytic fungal isolates | GenBank access number | Macro and microscopic identification | Related species in GenBank | Similarity (%) | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS311 | OR843338 | F. proliferatum | F. proliferatum | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS312 | OR842899 | Pestalotiopsis sp. | Pestalotiopsis sp. | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS414 | OR843339 | F. oxysporum | F. oxysporum | 100 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS439 | OR843341 | F. oxysporum | F. oxysporum | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS240 | OR843340 | F. solani | F. solani | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS455 | PP722765 | Trichoderma spirale | Trichoderma spirale | 98 | Euascomycetes |

| JS256 | OR852613 | F. solani | F. solani | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS469 | OR843989 | Umbelopsis nana | Umbelopsis nana | 99 | Zygomycetes |

| JS285 | OR843990 | Nectria sp. | Nectria sp. | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS286 | PP722977 | Fusarium sp. | Fusarium sp. | 100 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS296 | PP586144 | F. solani | F. solani | 94 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS4101 | PP724710 | F. solani | F. solani | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS3102 | PP586187 | Podospora dennisiae | Podospora dennisiae | 99 | Sordariomycetes |

| JS2107 | PP724711 | F. solani | F. solani | 100 | Sordariomycetes |

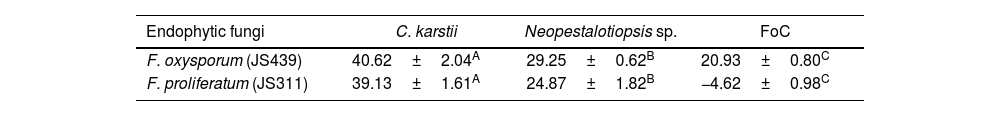

In the in vitro screening bioassay, F. proliferatum JS311 and F. oxysporum JS439 exhibited notable antagonistic responses against C. karstii. In the bioassay involving three pathogens, F. oxysporum JS439 inhibited the mycelial growth of C. karstii (40.62%), Neopestalotiopsis sp. (29.25%) and F. oxysporum (20.93%), respectively. In contrast, F. proliferatum JS311 inhibited the growth of C. karstii (39.13%) and Neopestalotiopsis sp. (24.87%) but showed no inhibition against F. oxysporum (Table 2).

Radial growth inhibition of C. karstii, Neopestalotiopsis sp. and F. oxysporum coffee (FoC) by EF isolates F. oxysporum JS439 and F. proliferatum JS311.

| Endophytic fungi | C. karstii | Neopestalotiopsis sp. | FoC |

|---|---|---|---|

| F. oxysporum (JS439) | 40.62±2.04A | 29.25±0.62B | 20.93±0.80C |

| F. proliferatum (JS311) | 39.13±1.61A | 24.87±1.82B | −4.62±0.98C |

Each result represents the mean±standard deviations (SD) of four replicates for each pathogenic fungus. Different letters within rows indicate statistically significant differences (Tukey's test, p≤0.05).

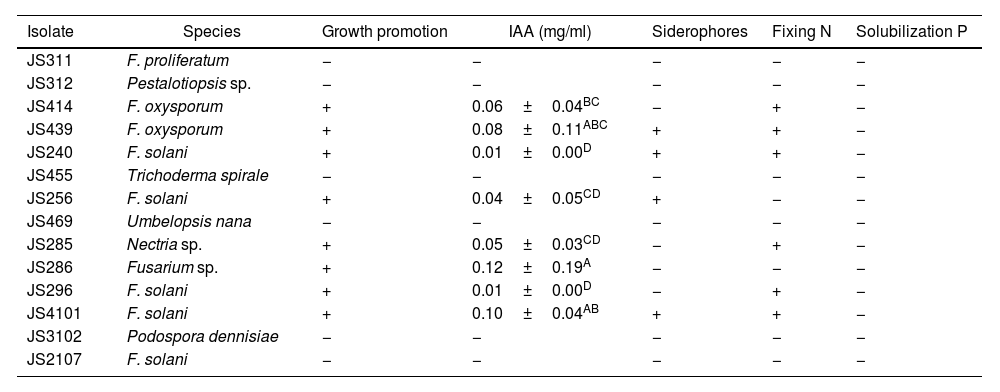

Eight of the 14 EF isolates associated with C. mirandae demonstrated growth-promoting effects of A. thaliana seedlings. Isolates of F. oxysporum (JS414 and JS439), F. solani (JS240, JS256, JS296 and JS4101), Nectria sp. (JS285) and Fusarium sp. (JS286) significantly enhanced root architecture, root hair development, and aerial growth of A. thaliana seedlings compared to the control group (Table 3 and Fig. 1).

Endophytic fungi from C. mirandae roots: growth promoters of A. thaliana, producers of IAA and siderophores, nitrogen (N) fixers, and phosphate (P) solubilizers.

| Isolate | Species | Growth promotion | IAA (mg/ml) | Siderophores | Fixing N | Solubilization P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JS311 | F. proliferatum | − | − | − | − | − |

| JS312 | Pestalotiopsis sp. | − | − | − | − | − |

| JS414 | F. oxysporum | + | 0.06±0.04BC | − | + | − |

| JS439 | F. oxysporum | + | 0.08±0.11ABC | + | + | − |

| JS240 | F. solani | + | 0.01±0.00D | + | + | − |

| JS455 | Trichoderma spirale | − | − | − | − | − |

| JS256 | F. solani | + | 0.04±0.05CD | + | − | − |

| JS469 | Umbelopsis nana | − | − | − | − | − |

| JS285 | Nectria sp. | + | 0.05±0.03CD | − | + | − |

| JS286 | Fusarium sp. | + | 0.12±0.19A | − | − | − |

| JS296 | F. solani | + | 0.01±0.00D | − | + | − |

| JS4101 | F. solani | + | 0.10±0.04AB | + | + | − |

| JS3102 | Podospora dennisiae | − | − | − | − | − |

| JS2107 | F. solani | − | − | − | − | − |

Based on the qualitative analysis, results were categorized as positive (+) or negative (−). For the quantitative analysis of IAA, each result represents the mean of four replicates±standard deviation (SD). Values with different letters indicate statistically significant differences according to Tukey's test (p≤0.05).

The eight EF isolates that promoted A. thaliana growth were found to produce IAA at varying concentrations (Table 3). Among these, F. oxysporum JS439, F. solani JS240, JS256 and JS4101 isolates demonstrated siderophore production, with F. oxysporum JS439 producing the largest orange halo on CAS medium (Table 3). Six isolates, including F. oxysporum (JS414, JS439), F. solani (JS240, JS296, JS4101) and Nectria sp. (JS285), exhibited the ability to grow in nitrogen-free medium (Table 3). However, none of the tested isolates showed positive results for phosphate solubilization (Table 3).

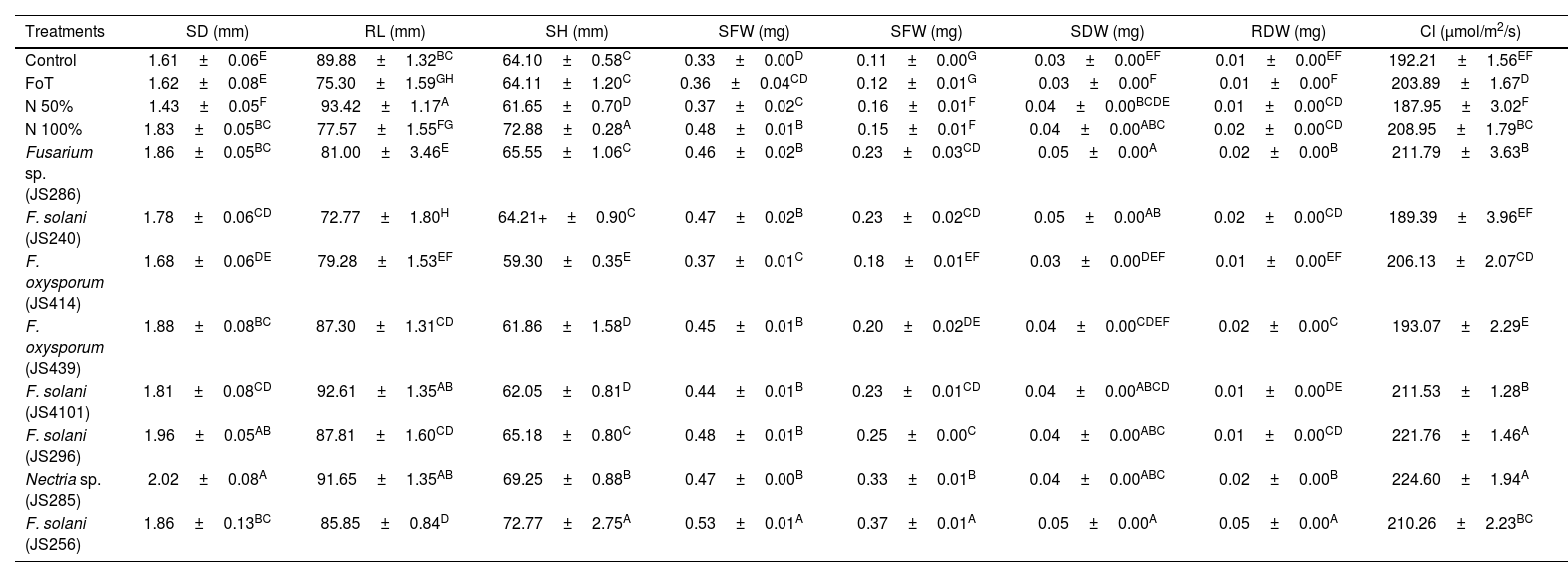

Endophytic Fusarium isolates promote tomato growthTomato seedlings inoculated with the EF isolates of C. mirandae, F. oxysporum JS414, JS439; F. solani JS240, JS256, JS296, JS4101; Nectria sp. JS285 and Fusarium sp. JS286, exhibited significantly enhanced growth across several variables, including stem diameter (SD), root length (RL), seedling height (SH), seedling dry weight (SDW) and root dry weight (RDW), compared to the control treatments (T1, T2, T3, T4) (Table 4).

Impact of endophytic Fusarium isolates on tomato seedling growth.

| Treatments | SD (mm) | RL (mm) | SH (mm) | SFW (mg) | SFW (mg) | SDW (mg) | RDW (mg) | Cl (μmol/m2/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.61±0.06E | 89.88±1.32BC | 64.10±0.58C | 0.33±0.00D | 0.11±0.00G | 0.03±0.00EF | 0.01±0.00EF | 192.21±1.56EF |

| FoT | 1.62±0.08E | 75.30±1.59GH | 64.11±1.20C | 0.36±0.04CD | 0.12±0.01G | 0.03±0.00F | 0.01±0.00F | 203.89±1.67D |

| N 50% | 1.43±0.05F | 93.42±1.17A | 61.65±0.70D | 0.37±0.02C | 0.16±0.01F | 0.04±0.00BCDE | 0.01±0.00CD | 187.95±3.02F |

| N 100% | 1.83±0.05BC | 77.57±1.55FG | 72.88±0.28A | 0.48±0.01B | 0.15±0.01F | 0.04±0.00ABC | 0.02±0.00CD | 208.95±1.79BC |

| Fusarium sp. (JS286) | 1.86±0.05BC | 81.00±3.46E | 65.55±1.06C | 0.46±0.02B | 0.23±0.03CD | 0.05±0.00A | 0.02±0.00B | 211.79±3.63B |

| F. solani (JS240) | 1.78±0.06CD | 72.77±1.80H | 64.21+±0.90C | 0.47±0.02B | 0.23±0.02CD | 0.05±0.00AB | 0.02±0.00CD | 189.39±3.96EF |

| F. oxysporum (JS414) | 1.68±0.06DE | 79.28±1.53EF | 59.30±0.35E | 0.37±0.01C | 0.18±0.01EF | 0.03±0.00DEF | 0.01±0.00EF | 206.13±2.07CD |

| F. oxysporum (JS439) | 1.88±0.08BC | 87.30±1.31CD | 61.86±1.58D | 0.45±0.01B | 0.20±0.02DE | 0.04±0.00CDEF | 0.02±0.00C | 193.07±2.29E |

| F. solani (JS4101) | 1.81±0.08CD | 92.61±1.35AB | 62.05±0.81D | 0.44±0.01B | 0.23±0.01CD | 0.04±0.00ABCD | 0.01±0.00DE | 211.53±1.28B |

| F. solani (JS296) | 1.96±0.05AB | 87.81±1.60CD | 65.18±0.80C | 0.48±0.01B | 0.25±0.00C | 0.04±0.00ABC | 0.01±0.00CD | 221.76±1.46A |

| Nectria sp. (JS285) | 2.02±0.08A | 91.65±1.35AB | 69.25±0.88B | 0.47±0.00B | 0.33±0.01B | 0.04±0.00ABC | 0.02±0.00B | 224.60±1.94A |

| F. solani (JS256) | 1.86±0.13BC | 85.85±0.84D | 72.77±2.75A | 0.53±0.01A | 0.37±0.01A | 0.05±0.00A | 0.05±0.00A | 210.26±2.23BC |

SD: stem diameter; RL: root length; SH: seedling height; SFW: seedling fresh weight; RFW: root fresh weight; SDW: seedling dry weight; RDW: root dry weight; Cl: chlorophyll content. F. oxysporum tomato (FoT), nitrogen (N). Each result represents the mean of eight seedlings±SD. Values within columns followed by the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey's test (p≤0.05).

In the SD variable, seedlings inoculated with EF and supplemented with 50% nitrogen fertilization recorded higher values than the control groups, including the positive control II (T4, 100% nitrogen). The highest SD values were observed in seedlings treated with Nectria sp. JS285 and F. solani JS296 at 2.02 and 1.96mm, respectively (Table 4).

For RL, the positive control T3 treatment (50% nitrogen) produced the longest roots at 93.42mm. However, seedlings inoculated with F. solani JS4101 plus 50% nitrogen and Nectria sp. JS285 plus 50% nitrogen recorded 92.65mm and 91.65mm, respectively, surpassing the control treatments T1, T2 and T4 (Table 4).

In the SH variable, EF-inoculated treatments promoted seedlings height compared to controls (T1, T2 and T3). The highest SH values were recorded in positive control II T4 (100% nitrogen control, 72.88mm) and F. solani JS256 plus 50% nitrogen (72.77mm), followed by Nectria sp. JS285 at 69.25mm (Table 4).

For seedling fresh weight (SFW) and root fresh weight (RFW), EF-inoculated seedlings with 50% nitrogen displayed comparable values to the 100% nitrogen control (T4), and outperformed treatments T1, T2 and T3. The highest SFW (0.53mg) and RFW (0.37mg) were achieved with F. solani JS256 plus 50% nitrogen (Table 4).

In the SDW and RDW variables, EF-inoculated seedlings with 50% nitrogen fertilization showed equivalent results to the 100% nitrogen positive control II (T4) and outperformed T1, T2 and T3. The highest SDW values (0.05mg) were observed in seedlings treated with F. solani JS256 plus 50% N and Fusarium sp. JS286 plus 50% N. For RDW, F. solani JS256 presented the highest value (0.05mg), exceeding all control treatments (Table 4).

Chlorophyll concentration in tomato leaves was highest in seedlings treated with Nectria sp. JS285 and F. solani JS296, with values of 224.60μmol/m2/s and 221.76μmol/m2/s, respectively. In comparison, the absolute water control treatment (T1) recorded a chlorophyll concentration of 192.21μmol/m2/s (Table 4).

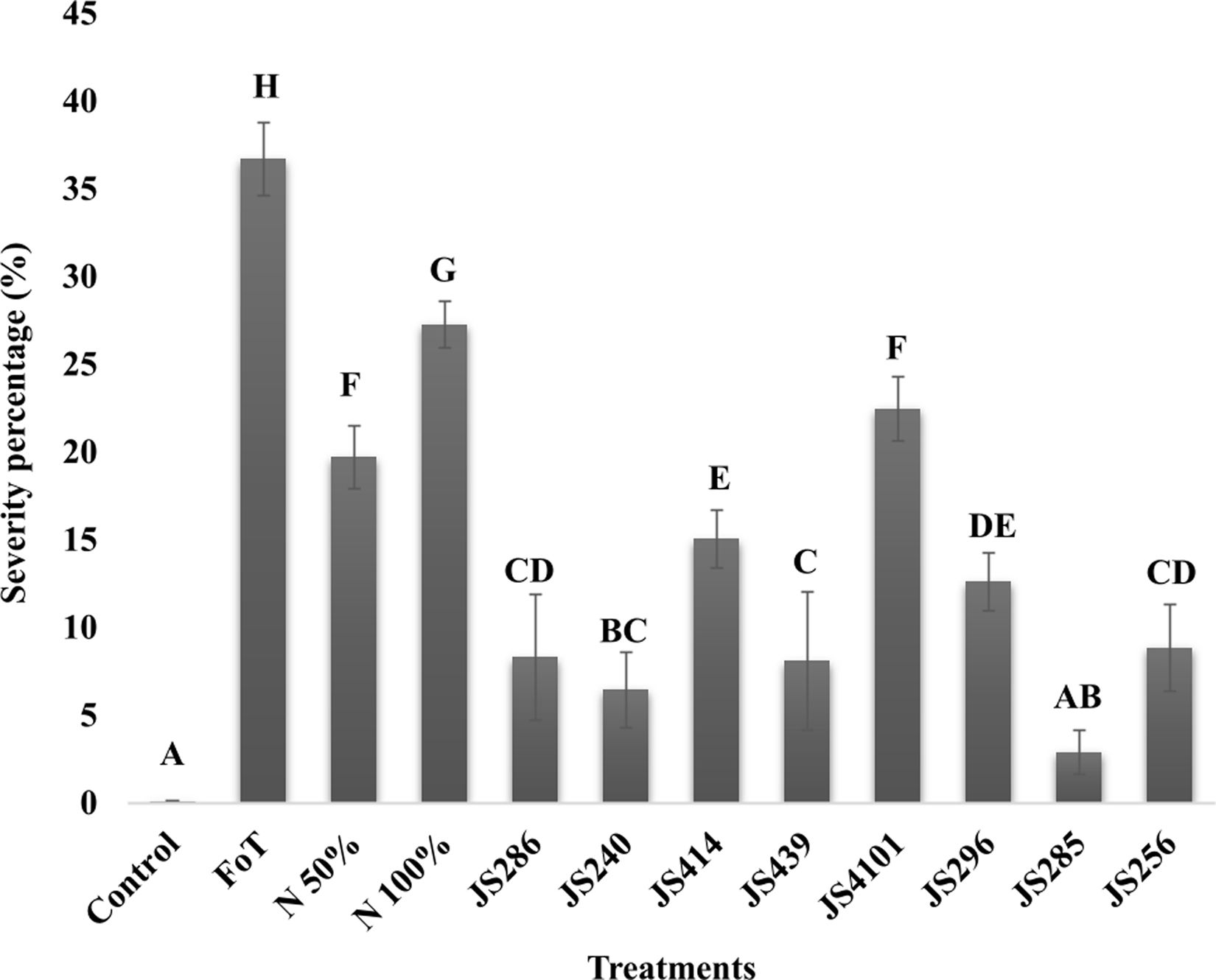

Colonization of tomato roots by endophytic Fusarium isolates induces resistance against B. cinereaSeven days after the foliar plant–pathogen interaction, diverse levels of severity caused by B. cinerea were observed. Tomato seedling leaves treated with different endophytic isolates of C. mirandae showed significant lower severity percentages compared to the control groups (negative control (T2), positive control I (T3) and positive control II (T4)). Among the treatments, Nectria sp. JS285 demonstrated the highest systemic resistance, with a severity value of 2.89%, which was statistically comparable to the absolute water control treatment (T1), with a severity of 0.07% (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that the inoculation of endophytic Fusarium isolates can effectively induce systemic resistance in tomato plants against B. cinerea.

Systemic protection induced by endophytic fungi of C. mirandae in tomato seedlings against the necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea. The bars in the graph represent the percentage of severity caused by B. cinerea. Each result is the mean of six replicates±SD. Values sharing the same letter are not significantly different according to Tukey's test (p≤0.05).

Fusarium was the most abundant genus (eight isolates) among the 14 EF isolated from C. mirandae roots. Fusarium is one of the three most dominant genera worldwide, with more than 1500 rhizosphere-associated species described48. Its strong ability to colonize tissues of a wide variety of host plants has also been documented28. Some strains are plant pathogens, while others can survive as saprophytes5. Due to its phytopathogenic nature, it is ranked among the ten most devastating fungal genera globally8. However, in recent years, non-pathogenic endophytic Fusarium strains have been reported to play beneficial roles in agriculture and forestry, owing to their ability to colonize root surfaces and protect even susceptible plant varieties from the highly virulent pathogenic isolates28.

Endophytic Fusarium isolates from C. mirandae showed in vitro antagonism against C. karstii, Neopestalotiopsis sp. and FoC. These results align with those reported by Hamzah et al.14, where Fusarium strains, such as mangrove endophytes, inhibited the growth of the pathogen F. solani 45–66%. It has been reported that non-pathogenic Fusarium isolates produce compounds such as 5-hexenoic acid, limonene, octanoic acid, 3,4-2h-dihydropyran, saponins, phenols, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, anthroquinones, and terpenoids, some of which are toxic to fungal and bacterial pathogens28.

Additionally, Fusarium isolates produced the highest amount of IAA (0.12mg/ml). Previous studies have reported that endophytic Fusarium isolates can produce up to 0.42mg/ml IAA.21 Other EF have been reported to have different amounts of IAA, such as Acremonium (53.12–167.71mg/ml)17, Didymella, Alternaria and Fusarium, which produced IAA levels of 0.5–16.0mg/ml44. Therefore, the amount of IAA produced by a fungus depends on the species and the nutritional and environmental conditions to which it is exposed13,28.

In this study, endophytic Fusarium isolates of C. mirandae produced siderophores; siderophore-producing fungi are generally considered to promote plant growth17. Six of the 14 EF isolates were able to grow in nitrogen-free medium, likely due to their association with diazotrophic microorganisms capable of nitrogen fixation, endohyphal bacteria40, or the production and secretion of enzymes such as ACC deaminase, which facilitate nitrogen fixation and transfer to plants17. However, EF isolates of C. mirandae were unable to solubilize phosphorus (P). In this regard, the primary EF isolates reported as P solubilizers belong to the genera Penicillium, Aspergillus, Piriformospora, Curvularia, and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi23. Nevertheless, endophytic Fusarium isolates capable of phosphate solubilization have been documented9. Therefore, the antagonistic and growth-promoting effects of beneficial Fusarium strains in plants are probably due to the production and secretion of various metabolites.

EF of C. mirandae positively modified root and shoot architecture in A. thaliana seedlings. It also significantly increased growth parameters (SD, RL, SH, SFW, RFW, SDW and RDW) in tomato seedlings. The use of endophytic Fusarium isolates has been documented in various agriculturally important crops. Cheng et al.4 reported that native Fusarium strains, along with their endobacterium Klebsiella aerogenes, promoted tomato seedling growth by increasing RL and SH compared to control groups. Similarly, Fauriah et al.9 demonstrated that endophytic Fusarium strains enhanced RL and SH in maize compared to control seedlings. Kisaakye et al.18 showed that non-pathogenic Fusarium strains improved banana yields during the first cycle, increasing SH and pseudostem circumference while reducing Radopholus similis nematode densities. Likewise, Moročko-Bičevska et al.26 demonstrated that endophytic Fusarium strains promoted strawberry growth, with significantly higher RFW and shoots weights compared to control plants. They also documented that pre-inoculating soil with Fusarium strains significantly reduced disease severity caused by Gnomonia fragariae. Glick12 showed that crude extracts from endophytic Fusarium strains of Biserrula pelecinus increased SDW and RDW values in Lolium multiforum (a forage plant) seedlings compared to controls. Moreover, tomato plants inoculated with Fusarium endophytes and fertilized with 50% nitrogen showed growth variables comparable to the positive control II T4 (100%). This suggests that the 50% nitrogen deficiency may be compensated by the production of various metabolites or through interactions between endophytes and other microorganisms28.

EF of C. mirandae significantly increased chlorophyll content in tomato seedlings. Hatamzadeh et al.15 reported that corn seedlings treated with Alternaria consortiale, an endophyte of Anthemis altissima, showed up to a 60% increase in chlorophyll levels compared to untreated seedlings. Higher chlorophyll concentrations enhance light energy uptake, thereby maximizing photosynthesis and accelerating plant growth35. It is important to note that although isolated endophytes of Fusarium have been shown to promote the growth of Arabidopsis and tomato seedlings, further studies are needed. This is particularly relevant given that some Fusarium species are pathogenic and produce mycotoxins during plant interactions, which can negatively affect plants and pose risks to human and animal health30.

EF of C. mirandae also induced systemic protection in tomato seedlings, reducing disease severity caused by necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea. Comparable results were observed with endophytic strains of Beauveria spp., which induced resistance in chili bell pepper and tomato plants against B. cinerea3. Additionally, Trichoderma asperellum has been reported to induce systemic protection against B. cinerea in tomato plants16. The confrontation assays in this study demonstrated the antifungal potential of EF from C. mirandae against B. cinerea. This systemic defense induction may result from the direct and/or indirect effects of EF on the plant. The application of non-pathogenic Fusarium strains to seeds, roots, or leaves has been shown to induce systemic resistance to pathogens, mediated by elicitors that trigger the expression of defense proteins such as glucanases, chitinases, peroxidases and PR proteins28. Li et al.19 attributed the biocontrol potential of Albifimbria verrucaria against B. cinerea in Vitis vinifera to its chitinase activity. Similarly, Asim et al.2 reported that endophytic Fusarium strains showed potential as bioherbicides in wheat (Avena fatua) due to their enzymatic activities, such as catalase and peroxidase. Therefore, these beneficial Fusarium isolates, in addition to producing growth-promoting metabolites, may also synthesize molecules that elicit induced systemic resistance.

This work documents non-pathogenic endophytic Fusarium isolates from C. mirandae with potential as plant growth promoters and biocontrol agents against fungal phytopathogens. These findings highlight the importance of endemic plants from protected natural areas as reservoirs of endophytic microorganisms with potential applications as biofertilizers or biocontrol agents in agriculture and forestry. Notably, this is the first report from Mexico of beneficial Fusarium isolates that promote plant growth and induce plant defense systems.

The advantages of beneficial Fusarium strains for plants have been reported28. In the particular case of these isolates, agronomic, biochemical and molecular characterization will continue to confirm the safety of cultivating these fungi, specifically ensuring that they do not produce mycotoxins in food. Moreover, identifying the metabolites responsible for their beneficial effects on plants is essential. It will also be important to investigate the potential horizontal transmission of virulence genes between Fusarium species, to prevent the risk of these beneficial strains becoming pathogenic.

ORCID IDNidia del C. Ríos-De León: 0009-0000-5013-2691

Brenda del R. Saldaña-Morales: 0009-003-9882-0567

Daniel A. Pérez-Corral: 0000-0001-8298-2738

Vidal Hernández-García: 0000-0002-9383-6426

Claudio Ríos-Velasco: 0000-0002-3820-2156

Sergio Casas-Flores: 0000-0002-9612-9268

Luis A. Rodríguez-Larramendi: 0000-0001-8805-7180

Rubén Martínez-Camilo: 0000-0002-9057-8601

CRediT authorship contribution statementNCRL conducted field and laboratory work, and contributed to writing the paper; BRSM and DPC performed laboratory work; VHG, CRV provided equipment and reagents for the experiments; SCF provided equipment and reagents for the experiments and contribute to the writing of the paper; LARL performed data analysis; RMC conducted field work and data analysis; MASM design the experiments, write and reviewed the paper.

Ethical approvalThis article does not include any studies involving human participants or animals conducted by the authors.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

FundingThis study was funded by University of Sciences and Arts of Chiapas (UNICACH).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We thank the Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo A.C. (CIAD-Unidad Cuauhtémoc) for their support in providing the facilities to carry out some experiments. We also thank Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) for their contribution to the first author's master's scholarship.