The concept of body representation overlaps with others, such as body schema, body image, body semantics, structural description, body description or body map. A taxonomy is proposed that classifies body schema, body structural description and body semantics. The aim of this narrative review is to analyze the supply of instruments for neuropsychological assessment of body representation and to propose a classification of their paradigms.

MethodA total of 1,109 articles were obtained and reduced to a total of 71 references by inclusion and exclusion criteria.

ResultsA total of 66 instrument names were found, of which 22 were related to body schema, 32 to structural description of the body and 12 to body semantics. Forty five instruments about clinical manifestations not commonly related to neurological etiology (e.g., anorexia, bulimia, hypochondria or schizophrenia) were discarded.

DiscussionA synthesis and classification of paradigms and instruments of interest to the clinic is presented. The need for the creation of validated consensus protocols and their implications are discussed.

El concepto de representación corporal se solapa con otros, como esquema corporal, imagen corporal, semántica corporal, descripción estructural, descripción corporal o mapa corporal. Se propone una taxonomía que clasifica el esquema corporal, la descripción estructural del cuerpo y la semántica corporal. El objetivo de esta revisión narrativa es analizar la oferta de instrumentos de evaluación neuropsicológica de la representación corporal y proponer una clasificación de sus paradigmas.

MétodoSe obtuvieron 1.109 artículos y se redujeron a un total de 71 referencias por criterios de inclusión y exclusión.

ResultadosSe encontraron un total de 66 nombres de instrumentos, de los cuales 22 se relacionan con el esquema corporal, 32 con la descripción estructural del cuerpo y 12 con la semántica corporal. Se descartaron 45 instrumentos sobre manifestaciones clínicas no relacionadas habitualmente con etiología neurológica (p.ej. anorexia, bulimia, hipocondría o esquizofrenia).

DiscusiónSe presenta una síntesis y clasificación de los paradigmas e instrumentos de interés para la clínica. Se discute sobre la necesidad de creación de protocolos validados de consenso y sus implicaciones.

Body representation (BR) was first described by Head and Holmes1 in 1911, and subsequently by Pick2 in 1922, when he described the body schema (BSch) and difficulties in recognising posture and locating body parts. Today, the concept of BR is controversial and remains under constant review,3–6 although 3 underlying constructs are recognised7,8: an implicit proprioceptive mechanism, the BSch, defined as a dynamic representation of the relative positions of different body parts, derived from multiple sensorimotor afferent signals (proprioceptive, vestibular, somaesthetic, visual, efference copy signals, etc); and 2 explicit, conceptual mechanisms: a) body structural description (BSD), a visual and somaesthetic mechanism defined as a continuous map of different locations derived from visual afferent signals that define the boundaries of body parts and their relationships with nearby objects9; and b) body semantics (BS), also known among neurologists as body image (a term also referring to the psychiatric concepts of self-conception and self-image), a lexical-semantic mechanism that includes the names of body parts, their functions, and their relationships with objects (Table 1).10,11

There is relative consensus regarding the anatomical correlates of these mechanisms: the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex for BSch7; the insula and superior temporal areas, as well as the extrastriate area at the right parieto-occipital junction for BSD12–14; and left recruitment for BS, with greater involvement of the left hemisphere.13,15 Developmental studies of healthy populations have reported that BR develops from the age of 10 years, and declines somewhat after 60 years of age,16,17 with a prevalence of 51%-81% among the population with stroke.7,18

Over the years, numerous articles have reported symptoms of impaired BR and body awareness,3,6 including allochiria, Gerstmann syndrome, heterotopagnosia, autotopagnosia, body integrity dysmorphia, and phantom limbs, among others, and their relationship with signs including apraxia,19–21 aphasia,10,22 and neglect.15,23,24 Effectively, BR is closely related to other cognitive processes, such as working memory,18 language,18 and motor control19; however, no comprehensive description of these relationships has yet been published.18

In general, BR has always been evaluated through verbal or non-verbal commands, with patients instructed to point to different body parts on their own or somebody else’s body,22,25 to construct a body using different body parts,26 to make a drawing,27 or to indicate the laterality of a body.28–30 Though the majority of instruments have been used in experimental tasks with individual patients,8,25 recent years have seen increased replication and larger patient samples.7,13,15,18,19,31,32

In Spain, the only instrument available for assessing BR is the Barcelona Test 2, whose modules 1 and 4 include 7 brief subtests in which patients are required to name, understand, or point to body parts, and to recognise their laterality.33 The remaining tests were mostly developed in other countries including Italy (eg, the Frontal Body Evocation task), Poland (eg, the Designating Body Parts task), and the United States (eg, the Matching Body Parts to Objects task),7,18,22,26 with no Spanish-language validation studies having been published. The objective of this review is to analyse the existing neuropsychological assessment instruments addressing BR in adults and children, and to propose a series of recommendations in this regard; we conducted a narrative systemic review in accordance with the PRISMA criteria (see Supplementary Material 1).34 To our knowledge, no similar review has previously been published.

Material and methodsSearch strategyGiven the conceptual breadth and diversity of terms observed after searching for the term body representation (BSch, BSD, BS, and body image),7,8 we used the descriptors for each term in each database (thesaurus, MeSH, descriptors, or indices) and conducted a preliminary review with each term to assess the volume and precision of results on an individual basis.

The terms “body schema,” “body structural description,” and “body semantics” are not indexed in all databases, whereas “body image” is. “Body image” is a search term than often belongs to both the semantic fields of neurology and psychiatry; therefore, we decided to use it as a main search term to avoid excluding true negative articles between fields. Furthermore, we observed that the term “body image” was also included in studies related to BSch, BSD, and BS; therefore, using this search term ensured that no cognitive study addressing BR was excluded.

The literature search was conducted between January and February 2022. The keywords selected for the literature search were “body image” and “neuropsychological assessment.”

The search was performed on the following databases: PubMed (MeSH), PsycINFO (Thesaurus), PSICODOC (Indices), Psyke (Descriptors), Web of Science (Keywords), Scopus (Keywords), and Teseo. The search strategy was as follows: (“body image”) AND (“neurops*”). Results were filtered for articles written in English or Spanish. We accessed each database through the affiliated distributors via the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology (FECYT, for its Spanish initials). We also searched the grey literature; no filter was applied to year of publication, with all articles published up to 2022 included.

Article selection strategyThe inclusion criteria used were a) articles addressing the assessment of BSch, BSD, or BS; and b) articles including at least one BR assessment instrument. The exclusion criteria were a) articles studying psychiatric or personality disorders without referring to BR assessment; and b) articles studying BR assessment but using instruments related to beliefs, attitudes, or psychoaffective factors, with no item referring to or potentially related to cognitive or neuropsychological analysis.

The literature search, article selection, and data extraction were conducted by the lead author (JFM), while articles were definitively included or excluded by the second author (JMRS), acting as an external reviewer. Furthermore, the Connected Papers software (https://www.connectedpapers.com/) was used to confirm the findings, using the keyword “body semantics” and assuming the term to be equivalent to the combination of the terms “body image” and “body schema.”

ResultsA total of 1109 articles were identified, of which a total of 71 remained after application of selection criteria (Fig. 1). We identified a total of 14 assessment paradigms, with 66 original names of instruments of neurological interest (Table 2). Twenty-two were related to BSch, and were administered to a total of 2384 subjects; 32 were related to BSD, and were administered to 1781 subjects; and 12 were related to BS, and were administered to 915 subjects (Table 3). As there were occasions on which a single subject was evaluated with different tasks belonging to a single construct, Table 4 presents all the paradigms and the total number of subjects examined with each. The most prevalent study population was healthy adults, and the paradigm with the most frequent and longest history of use was left-right judgement, evaluating BSch. We also excluded 45 instruments related to nuclear aspects of psychiatry, personality, belief (self-conception or self-image), attitudes, and other psychoaffective factors; these are listed in Supplementary Material 2. Supplementary Material 3 lists the study populations identified in the search, classified by medical specialty.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram34 depicting the literature review on body representation assessment instruments. As this was an exploratory study, we did not establish inclusion or exclusion criteria for type of study; therefore, the PRISMA 2020 criteria were only partially applied (e.g., we did not exclusively include randomised controlled trials).

Taxonomy of instruments and paradigms for the neuropsychological evaluation of body representation.

| Paradigm | Country | Instruments | Population (age) | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body schema | ||||

| Left-right judgement | USA | Left-Right Discrimination Test | 66 HC (4-8) | Benton,28 1959 |

| USA | 76 TBI, 32 HC | Semmes et al.,66 1963 | ||

| USA | 8 HC (university students) | Cooper et al.,46 1975 | ||

| Spain | Piaget-Head | 48 motor deficits (M: 10) | Sangorrín García,81 1977 | |

| USA | Left-Right Judgements of an Outstretched Arm of a Body in Observer’s Frontoparallel Plane | 68 HC (university students) | Parsons,30 1987 | |

| USA | Foot Laterality Task (FLT) | 22 HC (university students) | Parsons,49 1987 | |

| USA | 89 HC (university students) | Parsons,48 1994 | ||

| USA | Hand Laterality Task | 2 epilepsy (41-42); 8 HC (M: 37) | Parsons et al.,47 1998 | |

| USA | Identification of Hands in Different Positions Task | 13 stroke (M: 59.07) | Coslett23 (1998) | |

| USA | 1 dementia (62); 1 HC (62) | Buxbaum et al.,21 2000 | ||

| USA | Mental Own-Body Transformation Task (OBT) | 24 HC (19-31) | Zacks et al.,45 2002 | |

| USA | Right-Left Hand Discrimination Task | 1 dementia (62) | Coslett et al.,11 2002 | |

| USA | 55 stroke (M: 58); 18 HC (M: 47) | Schwoebel et al.,20 2004 | ||

| USA | 70 stroke (M: 55); 18 HC | Schwoebel and Coslett,7 2005 | ||

| Switzerland | 11 HC (M: 26.8) | Blanke et al.,41 2005 | ||

| Switzerland/UK | Mirror Task (MIR) | 24 HC (M: 26.85) | Arzy et al.,40 2006 | |

| UK/Switzerland | 48 HC (M: 27.3) | Easton et al.,43 2007 | ||

| Switzerland | 59 MS (59); 5 HC (M: 60.2) | Overney et al.,44 2009 | ||

| The Netherlands | 18 amputees (M: 62.8); 18 HC (M: 57.0) | Curtze et al.,36 2010 | ||

| USA | 82 pain (M: 48.65); 38 HC (M: 45.2) | Coslett et al.,38 2010 | ||

| Brazil | Oral Hand Laterality Task and Motor Hand Laterality Task | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | |

| Australia/Italy/UK | 32 stroke (M: 64.9); 36 HC (61.1) | Amesz et al.,52 2016 | ||

| Israel | 1 TBI (22), 14 HC | Krasovsky et al.,50 2017 | ||

| Poland | 50 ABI (M: 67.71); 50 HC (M: 68.71) | Razmus,18 2017 | ||

| Russia | Left-Right Task | 23 tumour (M: 36.7) | Nikishina et al.,35 2018 | |

| Canada | 61 pain (M: 55.82) | Pelletier et al.,51 2018 | ||

| Italy | Visuospatial Imagery Task | 30 CP (M: 11.65); 30 HC (M: 11.47) | Butti et al.,42 2019 | |

| Ireland/Italy/UK | 30 stroke (M: 50) | Lane et al.,19 2021 | ||

| Italy | 65 HC (7-8); 37 HC (9-10); 50 HC (18-40); 50 HC (41-60); 37 HC (> 60) | Raimo et al.,17 2021 | ||

| Same/different matching | USA | Same-Different Visual Matching Task for Body Position Memory | 65 HC (university students) | Reed and Farah,54 1995 |

| USA | Gesture Matching | 1 dementia (62); 1 HC (62) | Buxbaum et al.,21 2000 | |

| USA | 1 TBI (48) | Buxbaum and Coslett,9 2001 | ||

| Brazil | Hand Matching Task | 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | |

| Italy | Same-Different Visual Matching Task for Body Postures | 3 stroke (M: 67.66); 18 HC (M: 64.3) | Olgiati et al.,53 2017 | |

| Italy | 90 HC (7-10); 37 HC (18-35) | Raimo et al.,39 2019 | ||

| Italy | 26 stroke (M: 56.07); 39 HC (M: 57.67) | Boccia et al.,13 2020 | ||

| Italy | 33 CP (M: 7.69); 103 HC (M: 8.04) | Di Vita et al.,32 2020 | ||

| Italy | 64 stroke (M: 58.39); 41 HC (M: 58.39) | Raimo et al.,15 2022 | ||

| Observation and imitation (meaningless gestures) | USA | Hand Imagery and/or Action Task | 4 ABI (M: 47) | Sirigu et al.,55 1996 |

| Germany | Imitation of Meaningless Gestures | 205 stroke (M: 58.20); 90 HC (M: 54.75) | Goldenberg,56–58 1995, 1996, 2001 | |

| USA | Imitation of Meaningless Gesture Analogs | 1 dementia (62); 1 HC (62) | Buxbaum et al.,21 2000 | |

| USA | 70 stroke (M: 55) 18 HC | Schwoebel and Coslett,7 2005 | ||

| Brazil | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | ||

| Poland | Hand Action Task | 50 stroke (M: 67.71); 50 HC (M: 68.71) | Razmus,18 2017 | |

| Russia | Head’s Test and The Test of Transfer of Position from one Hand to Another | 23 tumour (M: 36.7) | Nikishina et al.,35 2018 | |

| Body structural description | ||||

| Body part localisation | UK | In-Between Task, Point Finger Test, Matchbox Test, and Finger Block Test | 12 Gerstmann syndrome (M: 54); 20 ABI (54.45) | Kinsbourne and Warrington,82 1962 |

| USA | Pointing to Those Parts of His Own Body Associated With a Number | 76 TBI (adults) | Semmes et al.,66 1963 | |

| Spain | 48 motor deficits (M: 10) | Sangorrín García,81 1977 | ||

| Italy/USA | Semenza and Goodglass Test | 32 stroke (M: 51.46) | Semenza and Goodglass,22 1985 | |

| New Zealand | Pointing to Parts of the Body on Himself by Imitation | 1 tumour (59) | Ogden,25 1985 | |

| USA | Localization of Objects on the Body | 1 dementia (62); 10 HC (adults) | Sirigu et al.,8 1991 | |

| Italy | 1 stroke (42) | Guariglia and Antonucci,69 1992 | ||

| Japan | 1 stroke (66) | Suzuki et al.,10 1997 | ||

| USA | Finger Grouping on Finger Identification Task | 13 stroke (M: 59.07) | Coslett et al.,23 1998 | |

| Italy | Body Part Localization Task | 1 stroke (67) | Denes et al.,72 2000 | |

| USA | Matching Body Parts: Effect of Impoverishment/Variability in Visual Features Task | 1 TBI (48) | Buxbaum and Coslett,9 2001 | |

| USA | Localization of Named Body Parts Task and Pointing to Pictured or Named Body Part on Oneself Task | 1 dementia (62) | Coslett et al.,11 2002 | |

| Italy | 1 stroke (78) | Guariglia et al.,65 2002 | ||

| France | Body Part Pointing Tasks | 2 dementia (68-73) | Felician et al.,60 2003 | |

| Italy | 1 stroke (78) | Marangolo et al.,70 2003 | ||

| USA | 55 stroke (M: 58); 18 HC (M: 47) | Schwoebel et al.,20 2004 | ||

| USA | 70 stroke (M: 55); 18 HC (adults) | Schwoebel and Coslett,7 2005 | ||

| The Netherlands | Finger Tactile Stimulus and Pointing Toward the Real Finger Touched Task | 7 stroke (61-81); 1 epilepsy (31) | Anema et al.,83 2008 | |

| France | Structural Knowledge of Body and Localization of Objects on the Body | 1 stroke (72) | Auclair et al.,63 2009 | |

| France | Body Part Pointing Tasks | 3 stroke (M: 59.66) | Cleret de Langavant et al.,62 2009 | |

| Italy/UK | Intermanual In-Between Task | 44 HC (M: 26) | Rusconi et al.,84,85 2009, 2014 | |

| Brazil | Image Marking Procedure | 16 pain (M: 23.9); 20 HC (23.6) | Thurm et al.,86 2013 | |

| Brazil | Verbal Body Part Localization Task, Visual Body Part Localization Task, and Pointing to Named Body Parts Task | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | |

| Italy | 1 stroke (62) | Di Vita et al.,64 2015 | ||

| Poland | 50 stroke (M: 67.71); 50 HC (M: 68.71) | Razmus,18 2017 | ||

| Israel | Body Part Pointing Tasks | 1 TBI (22); 14 HC (adults) | Krasovsky et al.,50 2017 | |

| Russia | 23 tumour (M: 36.7) | Nikishina et al.,35 2018 | ||

| Germany | 37 stroke (M: 60.13); 19 HC (59.7) | Dafsari et al.,59 2019 | ||

| Switzerland | 1 stroke (60) | Bassolino et al.,61 2019 | ||

| Switzerland/Italy | 32 stroke (59.25) | Ronchi et al.,87 2020 | ||

| Matching body parts by location | USA | Contiguity Task | 1 dementia (62) | Coslett et al.,11 2002 |

| USA | Matching Body Parts by Location Task | 70 stroke (M: 55); 18 HC | Schwoebel and Coslett,7 2005 | |

| France | 1 stroke (72) | Auclair et al.,63 2009 | ||

| Brazil | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | ||

| Poland | 50 ABI (M: 67.71); 50 HC (M: 68.71) | Razmus,18 2017 | ||

| Visual construction of the body | Spain | 48 motor deficits (M: 10) | Sangorrín García,81 1977 | |

| Spain | Body Representation Test and Drawing Task | 100 HC (7-11) | Daurat-Hmeljiak et al.26 1978; Spanish adaptation: Jiménez,27 1978 | |

| Italy | Frontal Body-Evocation Task (FBE) | 1 stroke (42) | Guariglia and Antonucci,69 1992 | |

| Japan | Mental Imagery Drawing and Drawing Task | 1 stroke (66) | Suzuki et al.,10 1997 | |

| Italy | 1 stroke (78) | Guariglia et al.,65 2002 | ||

| Italy | 1 stroke (78) | Marangolo et al.,70 2003 | ||

| Italy | 1 stroke (70) | Canzano et al.,68 2011 | ||

| Italy | 32 ABI (M: 59.56); 18 amputees; 15 HC (M: 55) | Palermo et al.,67 2014 | ||

| Italy | Human Figure Drawing Task | 1 stroke (62) | Di Vita et al.,64 2015 | |

| Italy | 23 stroke (M: 64.69); 16 HC (M: 66.44) | Di Vita et al.,24 2017 | ||

| Italy | 90 HC (7-10); 37 HC (18-35) | Raimo et al.,39 2019 | ||

| Italy | 23 stroke (M: 60.57); 9 HC (M: 60.33) | Di Vita et al.12 2019 | ||

| Italy | 33 CP (M: 7.69); 103 HC (M: 8.04) | Di Vita et al.32 2020 | ||

| Italy | 26 stroke (M: 56.07); 39 HC (M: 57.67) | Boccia et al.,13 2020 | ||

| Italy | 65 HC (7-8); 37 HC (9-10); 50 HC (18-40); 50 HC (41-60); 37 HC (> 60) | Raimo et al.,17 2021 | ||

| Italy | 64 stroke (M: 58.39); 41 HC (M: 58.39) | Raimo et al.,15 2022 | ||

| Explicit body knowledge | France | 3 stroke (M: 59.66) | Cleret de Langavant et al.,62 2009 | |

| Italy | 3 stroke (M: 67.66); 18 HC (M: 64.3) | Olgiati et al.,53 2017 | ||

| Italy | Visual Body Recognition Task | 30 CP (M: 11.65); 30 HC (M: 11.47) | Butti et al.,42 2019 | |

| France | 103 HC (M: 66.6) | Baumard et al.,16 2020 | ||

| Implicit body knowledge | Italy | Sideness test | 95 HC (university students) | Ottoboni et al.,71 2005 |

| Ireland/Italy/UK | 30 stroke (M: 50) | Lane et al.,19 2021 | ||

| Body semantics | ||||

| Body part naming | New Zealand | Watching While the Examiner Points to Body Parts on Another Person on Verbal Command | 1 tumour (59) | Ogden,25 1985 |

| USA | Naming Body Parts Task | 1 dementia (62); 10 HC (adults) | Sirigu et al.,8 1991 | |

| Italy | 1 stroke (67) | Denes et al.,72 2000 | ||

| USA | 1 dementia (50) | Coslett et al.,11 2002 | ||

| Italy | 1 stroke (78) | Guariglia et al.,65 2002 | ||

| The Netherlands | Finger Naming | 2 stroke (52, 59); 1 epilepsy (31) | Anema et al.,83 2008 | |

| France | 1 stroke (72) | Auclair et al.,63 2009 | ||

| France | 3 stroke (M: 59.66) | Cleret de Langavant,62 2009 | ||

| Brazil | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | ||

| Israel | 1 TBI (22); 14 HC (adults) | Krasovsky et al.,50 2017 | ||

| Poland | 50 ABI (M: 67.71); 50 HC (M: 68.71) | Razmus,18 2017 | ||

| Germany | 37 stroke (M: 60.13); 19 HC (M: 59.7) | Dafsari et al.,59 2019 | ||

| Body reading | UK | Finger Strip Test | 12 Gerstmann syndrome (M: 54); 20 ABI (54.45) | Kinsbourne and Warrington,82 1962 |

| USA | Oral Reading of Body Part Names | 1 dementia (50); | Coslett et al.,11 2002 | |

| Body-body matching | USA | Matching Body Parts by Function | 1 dementia (50) | Coslett et al.,11 2002 |

| USA | 55 stroke (M: 58); 18 HC (M: 47) | Schwoebel et al.,20 2004 | ||

| USA | 70 stroke (M: 55); 18 HC | Schwoebel and Coslett,7 2005 | ||

| Brazil | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | ||

| Object-body matching | Japan | 1 stroke (66) | Suzuki et al.,10 1997 | |

| USA | 1 TBI (48) | Buxbaum and Coslett,9 2001 | ||

| USA | Body Part and Object Association Task | 1 dementia (50) | Coslett et al.,11 2002 | |

| USA | 55 stroke (M: 58); 18 HC (M: 47) | Schwoebel et al.,20 2004 | ||

| USA | Matching Body Parts to Objects Task | 70 stroke (M: 55); 18 HC | Schwoebel and Coslett,7 2005 | |

| France | Semantic Knowledge of Body Parts Task | 1 stroke (72) | Auclair et al.,63 2009 | |

| Brazil | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | ||

| Israel | 1 TBI (22); 14 HC (adults) | Krasovsky et al.,50 2017 | ||

| Poland | 50 stroke (M: 67.71); 50 HC (M: 68.71) | Razmus,18 2018 | ||

| Italy | 23 stroke (M: 62.58) | Di Vita et al.,12 2019 | ||

| Italy | 90 HC (7-10); 37 HC (18-35) | Raimo et al.,39 2019 | ||

| Italy | Object-Body Part Association Task | 33 CP (M: 7.69); 103 HC (M: 8.04) | Di Vita et al.,32 2020 | |

| Italy | 26 stroke (M: 56.07); 39 HC (M: 57.67) | Boccia et al.,13 2020 | ||

| Italy | 64 stroke (M: 58.39); 41 HC (M: 58.39) | Raimo et al.,15 2022 | ||

| Observation and imitation (meaningful gestures) | USA | Imitation of Meaningful Gestures Task | 55 stroke (M: 58); 18 HC (M: 47) | Schwoebel et al.,20 2004 |

| Brazil | 61 CP (M: 8); 30 HC (M: 5) | Fontes et al.,31 2014 | ||

| Designating body parts | Poland | Designating Body Parts task | 50 ABI (M: 67.71); 50 HC (M: 68.71) | Razmus,18 2017 |

ABI: acquired brain injury; CP: cerebral palsy; HC: healthy controls; M: mean age (years); MS: multiple sclerosis; TBI: traumatic brain injury.

Participants’ age in years is shown in parentheses.

The instruments shown include all instruments with original names; in the majority of cases the task is replicated with minimal modifications, which does not add value to visual analysis.

Prevalence of different profiles of subjects evaluated in the different constructs of body representation.

| Body schema | Body structural description | Body semantics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | |||

| Controls | 922 | 542 | 246 |

| Stroke | 511 | 467 | 334 |

| Pain | 143 | 16 | 0 |

| TBI | 78 | 78 | 2 |

| MS | 59 | 0 | 0 |

| Tumour | 23 | 24 | 1 |

| Amputees | 18 | 18 | 0 |

| ABI | 4 | 52 | 0 |

| Epilepsy | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Gerstmann syndrome | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| Dementia | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Children | |||

| Controls | 450 | 425 | 223 |

| CP | 124 | 94 | 94 |

| Motor deficits | 48 | 48 | 0 |

| Total | 2384 | 1781 | 915 |

ABI: acquired brain injury; CP: cerebral palsy; MS: multiple sclerosis; TBI: traumatic brain injury.

Frequency of use of the different assessment paradigms.

| Number of participants | |

|---|---|

| Body schema | |

| Left-right judgement | 1658 |

| Same/different matching | 552 |

| Observation and imitation (meaningless gestures) | 603 |

| Body structural description | |

| Body part localisation | 896 |

| Matching body parts by location | 281 |

| Visual construction of the body | 962 |

| Explicit body knowledge | 157 |

| Implicit body knowledge | 125 |

| Body semantics | |

| Body part naming | 284 |

| Body reading | 13 |

| Body-body matching | 253 |

| Object-body matching | 826 |

| Observation and imitation (meaningful gestures) | 164 |

| Designating body parts | 100 |

The most widely used paradigm was left-right judgement (1658 subjects), in which participants are asked to identify a body part as belonging to the left or right side of the body,7,17,18,30,31,35–39 or whether an item is located to the left or to the right side of a body.40–46 Performing these tasks requires the existence of a standard, canonical body schema that is accurately represented in the brain, in order to subsequently perform a spatial transformation enabling matching to the visual analysis of the stimulus presented.30,46,47 Therefore, the subject performs a mental rotation of their own body from an egocentric perspective,45 using internal spatial and kinematic coding of their own body.21,48

The gold standard in this paradigm is the Hand Laterality Task,30,49 which has been replicated or adapted in multiple studies with different names,7,18,20,23,31,32,37,50 numbers of stimuli,7,18,20,21,31,32 stimulus orientation and manipulation,23,32,47 and types of response.7,18,23,31,32 Technological advances have enabled electronic administration of this paradigm using mobile apps (eg, Recognise App by the Neuro-Orthopedic Institute; Adelaide, South Australia; Fig. 2).19,51,52 The use of apps enables better control of stimulus types and increases the precision of data recording.19,51,52

Trial of a left-right judgement protocol in the Hand Laterality Task (Recognise App19,51) for assessing body schema. The subject must respond as quickly as possible whether a left or right hand is shown. The image is original, and corresponds to a screenshot of one of the randomly presented stimuli on “quick test” mode.

Another paradigm is same/different matching,21,31,53,54 which also demands spatial transformation as a function of a bodily stimulus. In these tasks, subjects are required to indicate whether 2 visual stimuli show the same or different body positions (Fig. 3). Stimuli may be presented sequentially or simultaneously.21,31,53

Original stimuli from the same/different matching paradigm used in the Body Schema Task.53 The subject must state whether 2 postures are the same or different.

Licence granted with copyright © 2017, American Psychological Association.

Finally, in imitation paradigms, subjects are asked to watch and repeat an action, and to imagine and accurately perform a movement; this enables comparison of the time taken and the accuracy in completing each task (eg, rapidly pinching the fingers 5 times).7,18,31,55 Imitation also involves access to an internal configuration of the body position of the person performing the action, particularly for meaningless gestures (e.g., imitating the position of a fist beneath the chin as demonstrated by the examiner).7,21,56–58

Evaluation of body structural descriptionThe body part localisation paradigm is based on the test developed by Semenza and Goodglass22 to assess autotopagnosia (inability or difficulty locating parts of one’s own body). In general terms, it consists in asking the subject to indicate the locations of different parts of their own body, somebody else’s body, or in an image or photograph, on a mannequin, or on a sheet with depictions of multiple body parts.7,18,22,25,31 It should be noted that this paradigm should be used first, or even exclusively, in a non-verbal form18,59 in order to avoid influencing the use of language and BS, and that the double dissociation with heterotopagnosia in the absence of autotopagnosia was only studied years later.60–62

Body part localisation tests have been adapted to different population profiles, with differences in the type and number of body parts targeted, the perspective of the body subjects are asked to point to, how stimuli are presented, how instructions are given, and even how errors are recorded.7,18,19,22,25,31,62–65 Technological advances have enabled replication of an associative variant of this paradigm66 using virtual reality headsets (Fig. 4), which have been tested in patients diagnosed with heterotopagnosia and healthy controls.61

Experimental virtual reality task for assessing heterotopagnosia with a body part localisation paradigm, developed by Bassolino et al.,61 to measure body structural description. The subject must indicate the number associated to different parts of a body (their own or somebody else’s) from different perspectives (first or third person).

Licence granted with copyright © 2019, Elsevier Ltd.

Another paradigm is matching body parts by location.11 In this task, the subject is presented with an image of a body part and subsequently of another 3 body parts, and asked to select the one that best corresponds to the spatial continuation of the first image. In the study by Fontes et al.,31 the literal instruction is “Point to the figure of the body part that is nearer or continues the figure of XXX.” Other authors used the questions “is the wrist next to the shoulder or the elbow?”63 or “what body part is below the thigh?”50

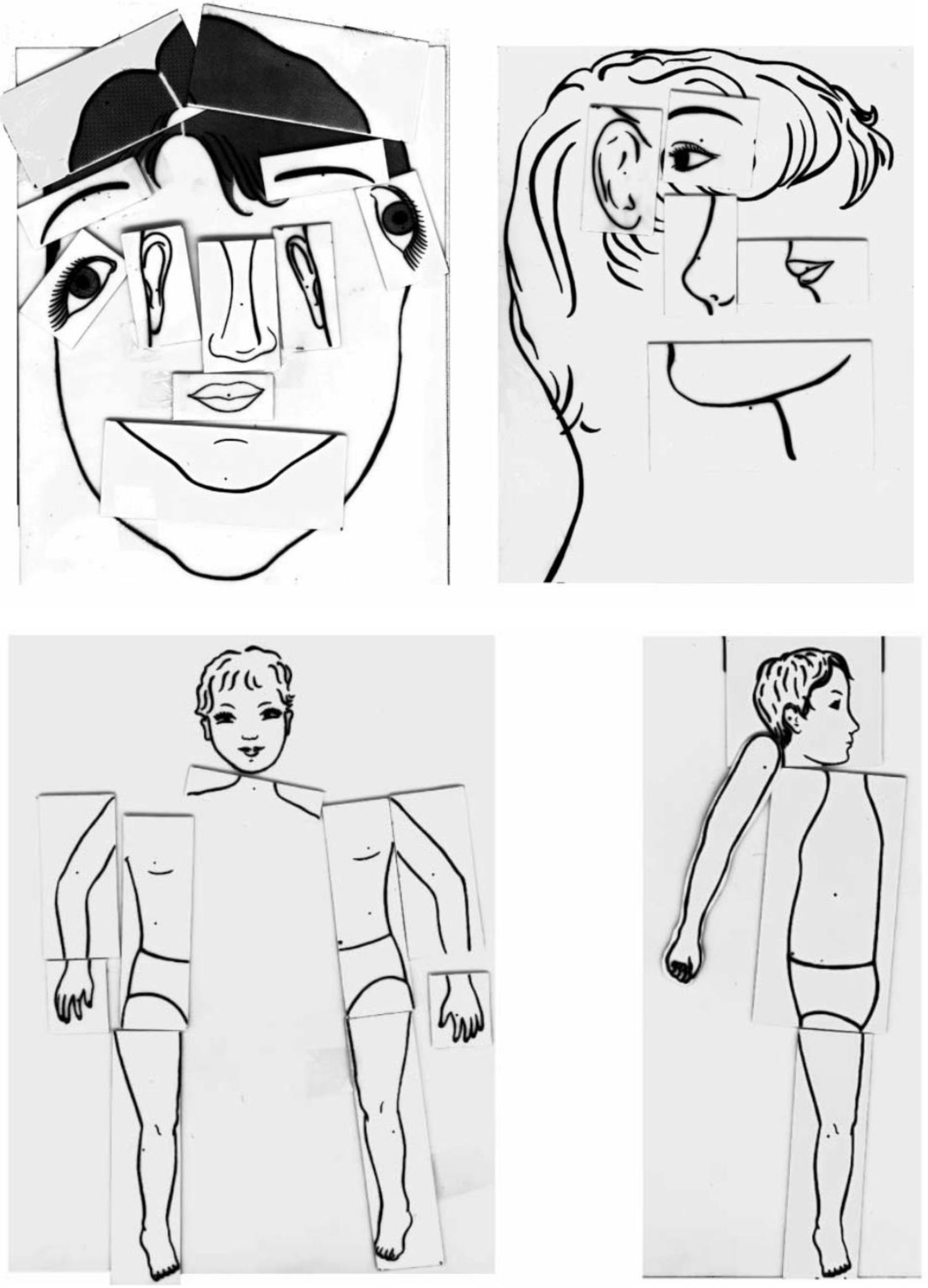

Another paradigm is visual construction, with the example of the Body Representation Test developed by Daurat-Hmeljiak et al.,26 or the Frontal Body-Evocation task,65 which was originally designed for children but has been replicated by other authors in other clinical populations, including patients with stroke, cerebral palsy, and amputations.12,13,15,24,64,65,67–70 In this task, participants are asked to construct a person’s body or face based on an image of a body or face fragmented into its parts (Fig. 5). In a recent study, Di Vita et al.13,32 developed a computerised version of this test, in which participants use a touchscreen to drag body parts into position one by one to construct the correct image. The advantage of this version is that it enables recording and coding of millimetric deviations from the accurate location of each body part. Human figure drawing tasks can also be considered a construction task, and are inexpensive to administer.10,27,64,70

Performance in the visual construction paradigm used in the Body Representation Test developed by Daurat-Hmeljiak et al.26,65 for evaluating body structural description.

Licence granted with copyright © 2019, Elsevier Ltd.

Finally, another paradigm is explicit body knowledge, in which participants are asked to distinguish between images of bodies in possible or impossible positions,16,42 or whether body parts do or do not belong to the participant’s own body.53 Regarding body knowledge, we should also mention the only implicit processing paradigm, which involves presemantic knowledge of body structure.19,71

Evaluation of body semanticsOne of the classical paradigms is naming tasks, in which participants are asked to verbally name the body parts shown in a series of photographs.8,11,18,25,31,50,72 Another approach is reading paradigms; for instance, in the Oral Reading of Body Part Names task,11 participants are asked to read 25 words corresponding to parts of the body, and correct and incorrect answers are recorded. Another of the more commonly used paradigms in BS assessment is object-body matching, in which subjects are asked to select the best association between an object and various body parts.18,31,39 As shown in Fig. 6, the test may include foils based on contiguous or conceptually related body parts.7,18

Stimuli from a trial of the Object-Body Part Association Task for evaluating body semantics. Subjects must indicate the body part most closely related to the object shown in the upper part of the slide. When testing children, the number of options shown in the lower part may be reduced to 2,32 whereas 3 options are shown to adults.18

Another matching paradigm, in this case body-body matching, is the Matching Body Parts by Function task.7,11,20,31 In this test, the examiner presents a screen with 4 images of different parts of the body (one at the top and 3 at the bottom of the screen), and subjects are required to decide which of the 3 bottom images is most closely related to the top image in terms of body function; subjects respond to a concrete association to the instruction “Point to or say the name of the figure that is doing similar things as the figure of XXX.”31 Finally, some articles used paradigms based on imitation of meaningful actions (eg, brushing hair, gesture of feeling cold), which constitute semantic mechanisms, or designating body parts, in which participants are presented with 22 photographs of body parts and asked to point to the ones named by the examiner.18

DiscussionThe concept of body representation refers to a broad range of related concepts, which have overlapped in the scientific literature in recent years: BSch, body image, BS, BSD, description of BR, body map, etc.6 These terms are not appropriately indexed in scientific databases, and return miscellaneous results from different healthcare areas. We propose a taxonomy of concepts based on the type of mechanism (implicit or explicit) and type of representation (perceptual or conceptual). Thus, BR could be categorised into BSch, BSD, and BS (Table 1).

Regarding the selection of assessment instruments, though a large range of tests have been described, the majority are variations on a single paradigm, and no standardised protocols exist. The main parameters showing differences are: the type of instructions, the form of sensory input of the instruction and the form of response, the types of stimuli presented, the number of series presented, the selection of measures for recording, the nomenclature of the tests, and the scoring system. In experimental tasks, the majority of instruments used to evaluate BR7,18,31 are reported in a single patient8,10,11,25,68 and have been replicated with sometimes contradictory results.7,18

We also observed a lack of consensus on certain essential matters, such as with the body part localisation paradigm, in which experts question whether or not the examiner should name the body part before asking the subject to point to it18,59 (this is one of the main criticisms that can be made of the only subtests validated in the Spanish adult population),33 or whether 2 or 3 possible responses should be shown in matching paradigms.18,32 In any case, it seems reasonable to minimise verbal commands in body part localisation tasks, as suggested by Dafsari et al.59 and Razmus,18 with a view to avoiding confusion between BDS and BS. If this recommendation is not followed, then 5 of the 7 subtests of the Barcelona Test 2 would amount to assessments of BS. It also seems inappropriate to present only 2 possible responses, as this may lead to results being influenced by chance; in the light of this, the versions presented by Auclair et al.63 seem interesting, as they eliminate the multiple-choice responses from the stimulus presentation, forcing the subject to answer freely without visual cues.

In general terms, the literature is better developed in such countries as the United States and Italy,7,18,22,25,31 with BR research being conducted by a small number of study groups, suggesting that the field may benefit from other cultural perspectives that may influence this research. In Spain, the Barcelona Test 2 subtests were validated in 2019; however, the publication was not identified in the literature review, hence their exclusion from Table 2.33 In our opinion, their inclusion would provide one test of BSch (imitation of pseudogestures), one test of BSD (finger recognition), and 5 tests of BS (visual/verbal naming of body parts, verbal comprehension of body parts, left/right orientation, pantomime of object-use, and symbolic gestures of communication), which are validated in the Spanish language (336 healthy adults aged 20-87 years); this is highly relevant for their inclusion in routine examination. In general, there is a tendency for authors to use classical instruments7,17,18,31; nonetheless, there is currently no consensus on the administration protocol in this assessment, and these studies therefore present great differences in methodology. In fact, there are numerous examples31 in which the same test is given different names, and could be classified under a single paradigm, simplifying searches.

To that end, the most promising future perspective would include selecting stimuli (body parts) according to a scientific criterion, such as frequency of use or the results of factor analysis, and establishing the names of tasks and specifying variants in the procedure. In addition to standardisation efforts, recent years have seen a computerisation of tasks with an emphasis on measurement precision and replicability. Despite this, few studies have used a fully computerised test battery.13,15,32

The inclusion of BR instruments in neuropsychological assessment protocols would enable deeper understanding of the relationship between such cognitive processes as language and motor action,73–77 among others. This would also enable study of integrated body-mind therapies, which aim to improve awareness of the body and movement, or embodied cognition, and may moderate executive functions and memory.78–80 The creation of a specific, sensitive instrument for assessing BR may lead to a clinically useful screening test for pathological ageing and such other conditions as cerebrovascular lesions, enabling timely prevention with therapies that stimulate BR, and promote health and quality of life in patients with impaired BR.16

In this regard, Table 5 presents a series of screening questions for assessing different responses about the body and related to BR. Despite the main strengths of our study, which extensively gathers all cognitive instruments assessing BR and classifies them into 14 paradigms, it does present several limitations. These include the fact that we did not filter according to type of article (eg, randomised clinical trials, trials with 2 groups, etc), which hinders risk-of-bias analysis and the acquisition of synthesis measures in accordance with the PRISMA criteria34; although this was an exploratory study, these analyses would have enabled better control for possible biases. We also did not establish a working criterion for excluding articles with paediatric populations, although we filtered out these studies in the preliminary PubMed search as the number of results was unmanageable. Furthermore, the study was not registered in advance, which may compromise the transparency of the evidence.

Proposed clinical questions to explore different components of body representation.

| Construct | Clinical questions | Responses | Paradigm |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSch | How is it positioned? | Posture | Left-right judgement |

| Same/different matching | |||

| Observation and imitation (meaningless gestures) | |||

| BSD | Where is it? | Position | Body part localisation |

| Matching body parts by location | |||

| Visual construction of the body | |||

| What does it look like? Which is it? | Shape | Explicit body knowledge | |

| Implicit body knowledge | |||

| BS | What is it? What is it called? | Semantic | Body part naming |

| Reading | |||

| Designating body parts | |||

| Observation and imitation (meaningful gestures) | |||

| What is it used with? What is it for? | Affordance* | Object-body matching | |

| How does it work? How is it used? | Mechanics | Body-body matching |

BSD: body structural description; BSch: body schema; BS: body semantics.

Note: questions refer to the body or parts of the body.

We observed considerable terminological confusion, and therefore propose a taxonomy of concepts based on the type of mechanism (implicit or explicit) and the type of representation (perceptual or conceptual).

Many studies used certain classical instruments, with various levels of modification, although no validated, evidence-based consensus protocol has been established.

A BR evaluation protocol should include, as a minimum, left-right judgement, body part localisation, and object-body matching paradigms.

Appropriate assessment instruments should be developed in the light of the fact that altered BR is common to numerous diseases.

We propose that the names of the paradigms mentioned be treated as a consensus for communication in the replication of studies into BR, and that the term body representation be popularised as a supra-ordinal category to the terms BSch, BSD, and BS.

To our knowledge, ours is the first Spanish-language review of assessment instruments for BR.

FundingThis study has received no external funding of any kind.

The authors have no financial or personal relationships with other persons or organisations which could create conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

The authors thank Jordi Peña-Casanova for sharing the normative data for the Programa Integrado de Exploración Neuropsicológica-Barcelona Test 2. We also thank Rocío Polanco, Patricia Martín, Roberta Ghedina, and Magdalena Razmus.