Sensory neuronopathy (SN), or sensory ganglionopathy, is a rare subtype of peripheral neuropathy characterised by damage to the soma of peripheral sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia, the Gasserian ganglion, and the enteric nervous system.1–3

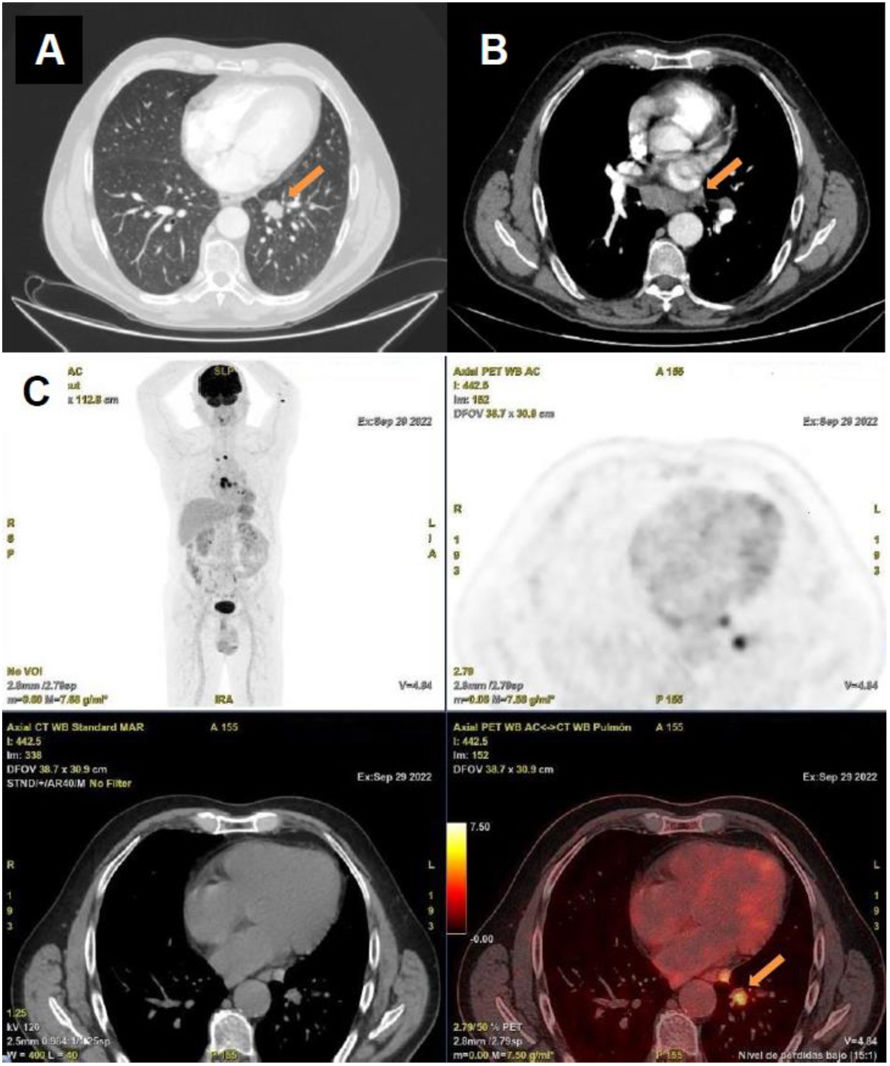

We present the case of a 57-year-old man with history of smoking, seronegative cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and pulmonary sarcoidosis under treatment with corticosteroids. Following SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent vaccination, he developed subacute onset of paraesthesias and neuropathic pain, which slowly progressed in a proximal direction affecting all 4 limbs. Symptoms eventually caused gait instability and impaired manual dexterity. The examination revealed impaired proprioception, generalised areflexia, and sensory ataxia. Sensory nerve conduction studies revealed a marked decrease in sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitudes, with a mild decrease in conduction velocity, predominantly affecting the upper limbs, suggesting a non-length-dependent pattern. The ulnar sensory-motor amplitude ratio (USMAR)4 was 0.24, supporting the diagnosis of SN. H-reflexes and somatosensory evoked potentials were also abnormal (Fig. 1). Motor nerve conduction studies, needle electromyography, autonomic function testing, and spinal cord MRI yielded normal results. Serological testing revealed positivity for anti-FGFR3 antibodies, while results for onconeural antibodies (anti-Hu, anti-Yo[PCA-1], anti-Ri, anti-CV2/CRMP5, anti-PNMA2[Ma2/Ta], anti-amphiphysin, anti-recoverin, anti-SOX1, anti-Zic4, anti-GAD65, anti-Tr[DNER], anti-titin), neuronal surface antibodies (anti-NMDAR, anti-GABABR, anti-AMPA, anti-LGI1, anti-CASPR2, anti-DPPX), and antiganglioside antibodies were all negative. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed pleocytosis (20 cells/µL; 98% lymphocytes) and elevated protein level (63.2 mg/dL). A CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a pulmonary nodule in the right lower lobe with mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Positron emission tomography revealed hypermetabolism in these areas (Fig. 2). Biopsy of the lesion confirmed a diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with immune-mediated SN of paraneoplastic and/or dysimmune origin associated with anti-FGFR3 antibodies.

Neurophysiological study including sensory nerve conduction study (A), H-reflex testing (B), and somatosensory evoked potentials (C).

The images illustrate a part of the neurophysiological evaluation conducted on the patient. A) Sensory nerve conduction in the upper limbs (bilateral median, ulnar, and radial nerves) and lower limbs (bilateral sural nerves). The upper limbs show a decrease in sensory nerve action potential amplitudes, associated with diffuse slowing of conduction velocities consistent with secondary axonal damage. These findings are observed in both orthodromic and antidromic studies, indicating non–length-dependent fibre involvement. B) The H-reflexes are absent bilaterally. C) Somatosensory evoked potentials show decreased amplitude and delayed latencies bilaterally in the lower limbs. In the upper limbs, pathological responses were detected on the right side, characterised by delayed latencies and less well-defined waveforms compared to the contralateral side, revealing clear asymmetry.

Staging imaging study conducted as part of the diagnostic workup performed to rule out an occult neoplasm. The chest CT scan (A) reveals a pulmonary nodule measuring 21 mm in its largest diameter, located in the left lower lobe, as well as bilateral prevascular (largest measuring 12 mm), infracarinal (largest measuring 21 mm), and hilar adenopathies (largest measuring 17 mm) located on the right side (B). The PET-CT scan (C) revealed hypermetabolism in the pulmonary nodule and the mediastinal adenopathies.

Damage to the soma of peripheral sensory neurons may result from paraneoplastic, inflammatory, viral, toxic/nutritional, or genetic causes.1–3,5 The most frequently identified aetiology of SN is paraneoplastic, and is considered one of the high-risk phenotypes of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes.6 The onconeural antibodies most frequently associated with paraneoplastic SN are anti-Hu, anti-CV2/CRMP5, and anti-amphiphysin antibodies,2,3,5,6 which are present in up to 90% of patients,3,7 usually in association with small cell lung carcinoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and other carcinomas.5–7 However, despite exhaustive aetiological work-up, no cause is identified in up to 50% of cases,5 although a underlying dysimmune origin is suspected in nearly half of them.8 The systemic autoimmune disease most frequently associated with SN is Sjögren syndrome, with positivity for anti-SSA antibodies.5,9 However, other systemic autoimmune diseases may also be associated with small-fibre neuropathy, which should be considered in the differential diagnosis.10 Recent anti-AGO and anti-FGFR3 antibodies in up to 13% and 15%-19% of patients with SN, respectively.3,5,11,12 Debate is ongoing as to whether these antibodies play a pathogenic role in SN or rather act as biomarkers of the underlying dysimmune process.5,13 To date, no prior cases of SN with positive anti-FGFR3 antibodies and lung cancer have been reported in the literature, while the association between anti-FGFR3 antibodies and sarcoidosis in patients with SN has only rarely been described.13 Therefore, the relationship between anti-FGFR3 antibodies and lung adenocarcinoma is yet to be established. In our patient, it is unclear whether SN was caused exclusively by anti-FGFR3 antibodies in the context of other immune processes (sarcoidosis and cutaneous lupus erythematosus) or by a seronegative paraneoplastic syndrome, or whether anti-FGFR3 antibodies were of paraneoplastic origin and were therefore associated with both SN and lung adenocarcinoma. Further research is needed to determine this association.

Among the limitations of this study, we were unable to analyse antibody production by the tumour in the pathological specimen.

In conclusion, this case shows that multiple potential causes of SN may coexist in a single patient. In paraneoplastic cases,where tumor-directed therapy is critical, early diagnosis is particularly necessary due to its vital prognostic implications. Hence, thorough malignancy screening should be conducted even in the absence of onconeural antibodies, as up to 10% of cases may be seronegative or associated with other, known or unknown, types of antibodies.7 Although it remains unclear whether there is a causal link between anti-FGFR3 antibodies and lung adenocarcinoma, or whether the presence of antibodies reflects dysimmune SN related to sarcoidosis, the case presented here raises the possibility of an association between both conditions.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors provided intellectual content to this study and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical considerationsPatient confidentiality was preserved. The patient gave verbal and written informed consent for the publication of this case report.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to the neurophysiology, radiodiagnosis, and nuclear medicine departments of Hospital Universitario de Cruces for their constant and willing collaboration with the neurology department, and particularly in this case for the images and complementary test results.