The incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is variable and is still unknown in our geographical area. Poor prognostic factors have been studied, but few have analysed those that influence long-term results. The objective of this study is to know the incidence, characteristics and factors associated with disability and dependency in these patients from a population registry.

Subjects and methodsObservational study in patients diagnosed with GBS from 2009 to 2020 and registered in the Rare Disease Information System of the Region of Murcia (SIER). The crude and adjusted rates for age, sex and year of the period were calculated and the associations between disability and/or dependency with the rest of the variables were analysed.

ResultsDuring the study period, 250 incident cases were diagnosed. The standardised incidence rate (SIR) was 1.52/100,000 person-years, higher in men and increasing with age in both sexes. The disease was more frequent after respiratory infections (46.4%) and in the cold months (56.4%), and the predominant variant was AIDP (54.3%). Greater disability and/or dependence were observed in patients with prolonged hospital stay (OR = 13.19; 95% CI: 3.81–45.67), ICU admission (OR = 2.37; 95% CI: 1.11-5.06) and affected by axonal variants (OR = 3.54; 95% CI: 1.64-7.69) (P < 0.05).

ConclusionsThe regional SIR is consistent with that reported in the national and international literature. 18.4% of the cases have recognised dependency and/or disability, associated with the axonal forms of the disease. Studies based on population registries offer representative and updated information and allow us to discover characteristics associated with a worse prognosis.

La incidencia del síndrome de Guillain-Barré (SGB) es variable y aún se desconoce en nuestro ámbito geográfico. Se han estudiado factores de mal pronóstico, pero pocos han analizado aquellos que influyen en resultados a largo plazo. El objetivo de este estudio es conocer la incidencia, características y factores asociados a discapacidad y dependencia en estos pacientes a partir de un registro poblacional.

Sujetos y métodosEstudio observacional en pacientes diagnosticados de SGB desde 2009 a 2020 y registrados en el Sistema de Información de Enfermedades Raras de la Región de Murcia (SIER). Se calcularon las tasas crudas y ajustadas por edad, sexo y año del periodo y se analizaron las asociaciones entre discapacidad y/o dependencia con el resto de variables.

ResultadosDurante el periodo de estudio se diagnosticaron 250 casos incidentes. La tasa de incidencia estandarizada (TIE) fue 1,52/100.000 personas-año, mayor en hombres e incrementándose con la edad en ambos sexos. La enfermedad fue más frecuente tras infecciones respiratorias (46,4%) y en los meses fríos (56,4%), y la variante predominante fue la AIDP (54,3%). Se observó mayor discapacidad y/o dependencia en pacientes con estancia hospitalaria prolongada (OR = 13,19; IC 95%: 3,81–45,67), ingreso en UCI (OR = 2,37; IC 95%: 1,11–5,06) y afectados por variantes axonales (OR = 3,54; IC 95%: 1,64–7,69) (P < 0,05).

ConclusionesLa TIE regional es concordante con la reportada en la literatura nacional e internacional. Un 18,4% de los casos tienen reconocida dependencia y/o discapacidad asociadas a las formas axonales de la enfermedad. Los estudios basados en registros poblacionales ofrecen información representativa y actualizada y permiten conocer características asociadas a un peor pronóstico.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a rare acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy of autoimmune origin, characterised by symmetrical limb weakness with or without hyporeflexia or areflexia.1,2

Its incidence is highly variable, ranging from 0.38 to 2.53 cases per 100 000 person-years, although most studies report rates of 1.1–1.8 cases per 100 000 person-years. Rates are higher among men and increase with age.3,4 In Spain, the incidence of GBS ranges from 0.86 to 1.56 cases per 100 000 person-years. However, these rates have not been updated in recent years, with very few recent studies on the disease, none of which has been conducted in our region.5–7

Although GBS is an acute condition that typically resolves within a matter of months, some patients may present persistent sequelae.8 Some authors have described factors potentially related to poor prognosis based on the results of several disability scales.9,10 However, most of these studies use data from hospital units or specific population groups, and very few analyse factors of poor long-term prognosis.11–13

The purpose of this study is to determine the incidence and main characteristics of patients with GBS in the Spanish region of Murcia, as well as to analyse the factors associated with official recognition of disability and dependence, based on data from the region’s registry of rare diseases.

Patients and methodsStudy populationWe conducted an observational study of patients diagnosed with GBS between January 2009 and December 2020 who were included in the registry of rare diseases of the region of Murcia (SIER, for its Spanish initials).14 We excluded individuals who were not resident in the region of Murcia, patients with an inconclusive diagnosis, and patients with a definitive diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy.

Patient informed consent was not required as the SIER is listed as an exception under personal data protection legislation on public health actions related to rare diseases in the region of Murcia.15

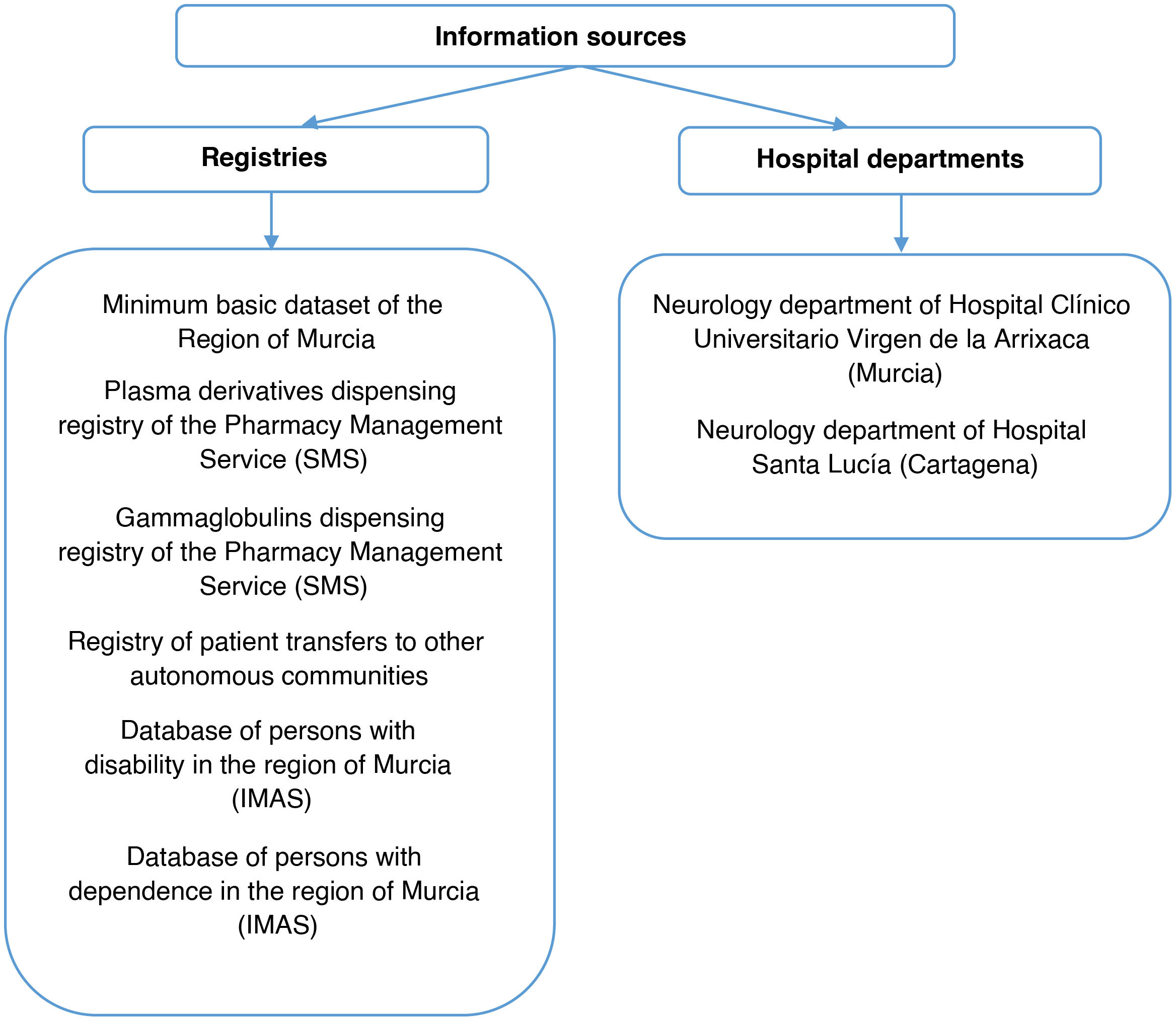

The registry of rare diseases of the region of Murcia (SIER)The SIER is a population-based registry launched in 2010 in the region of Murcia (population of 1 518 486 at 1 January 2021, amounting to approximately 3.2% of the Spanish population).16 Individuals with rare diseases are registered using the coding system of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). GBS was classified as code 357.0 of the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) until 2015, and as code G61.0 of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) from 2016 to 2020. The registry includes patients with rare diseases from 50 information sources. The sources that contributed cases of GBS to the registry are listed in Fig. 1.

The included cases are validated after review of their electronic medical records.

Data collectionWe gathered the following data from each patient:

Basic patient data. We gathered data on sex, country of origin, birth date, date at diagnosis, whether the patient was deceased at the time of study inclusion, and cause of death.

Clinical characteristics at baseline. Data were gathered on the season in which GBS was diagnosed, date of onset and initial clinical manifestations, and potential trigger factors occurring in the previous 4 weeks (gastrointestinal/respiratory/other infection, exposure to toxic substances, history of surgery or vaccination).

Regarding symptoms at disease onset, non-painful burning, tingling, or numbness of the limbs was regarded as paraesthesia, whereas hypersensitivity to stimuli associated with pain, burning sensation, or rigidity was regarded as dysaesthesia.17

Patients were classified according to GBS variant: acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP), acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN), acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), acute sensory ataxic neuropathy, Miller-Fisher syndrome (MFS), Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis, bifacial weakness with paraesthesias, and pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant. These variants were further classified as either axonal (AMAN and AMSAN) or demyelinating (the remaining subtypes) based on electrophysiological signs and the clinical characteristics described in the patients’ clinical histories. The pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant was excluded, as it was considered to be both axonal and demyelinating in the patient in whom it was diagnosed.18,19

Hospitalisation data. Data were gathered on intensive care unit (ICU) admission (yes/no); the total duration of the stay in hospital and in the ICU (in days); treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, or both; and need for tracheostomy or mechanical ventilation due to in-hospital complications.

Clinical progression. We gathered data on recurrence, sequelae at 6 and 12 months, and transfer to Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos, in Toledo, a specialised centre for the integrated care of patients with spinal cord alterations. Recurrence was defined as the occurrence of at least 2 episodes meeting diagnostic criteria for GBS with complete or near-complete recovery after the initial episode, and a minimum interval of 2 months between episodes. Patients presenting improvement after treatment with a subsequent relapse within 2 months were not considered to present recurrence of GBS.20,21 Persistence of any of the initial manifestations, development of muscle atrophy, and presence of cramps, tremor, or neuropathic pain were regarded as sequelae.21

We also gathered data about whether patients were officially recognised as having disability (≥ 33%) and/or dependence due to GBS, as well as the degree of disability/dependence, until 31 December 2021, one year after the study end date.22,23

Data analysisWe calculated crude rates and rates adjusted by age group, sex, and year of the study period. Crude rates were calculated using data from the region’s population registry, whereas standardised rates were calculated with the direct method using the 2013 European standard population.

The exact method was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI), assuming a Poisson distribution. Time trends were analysed with the Joinpoint Regression Program, version 4.9.0.0 (March 2021; Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD, USA).

We subsequently analysed the variables obtained for the total sample of patients and for each GBS subtype using descriptive statistics. Furthermore, several hypothesis tests were used depending on the type of variable and whether they were normally distributed. We tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and for equality of variance with the Welch test. Normally distributed quantitative variables were compared with ANOVA, whereas non–normally distributed quantitative variables were compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Qualitative variables were compared with the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

Lastly, crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with their 95% CIs were calculated with binary logistic regression to assess the relationship between disability and/or dependence and the study variables.

All tests were two-tailed, and the level of statistical significance was established at ≤ .05. Statistical analysis was completed using the SPSS software, version 25.0 (IBM Corporation; Armonk, NY, USA).

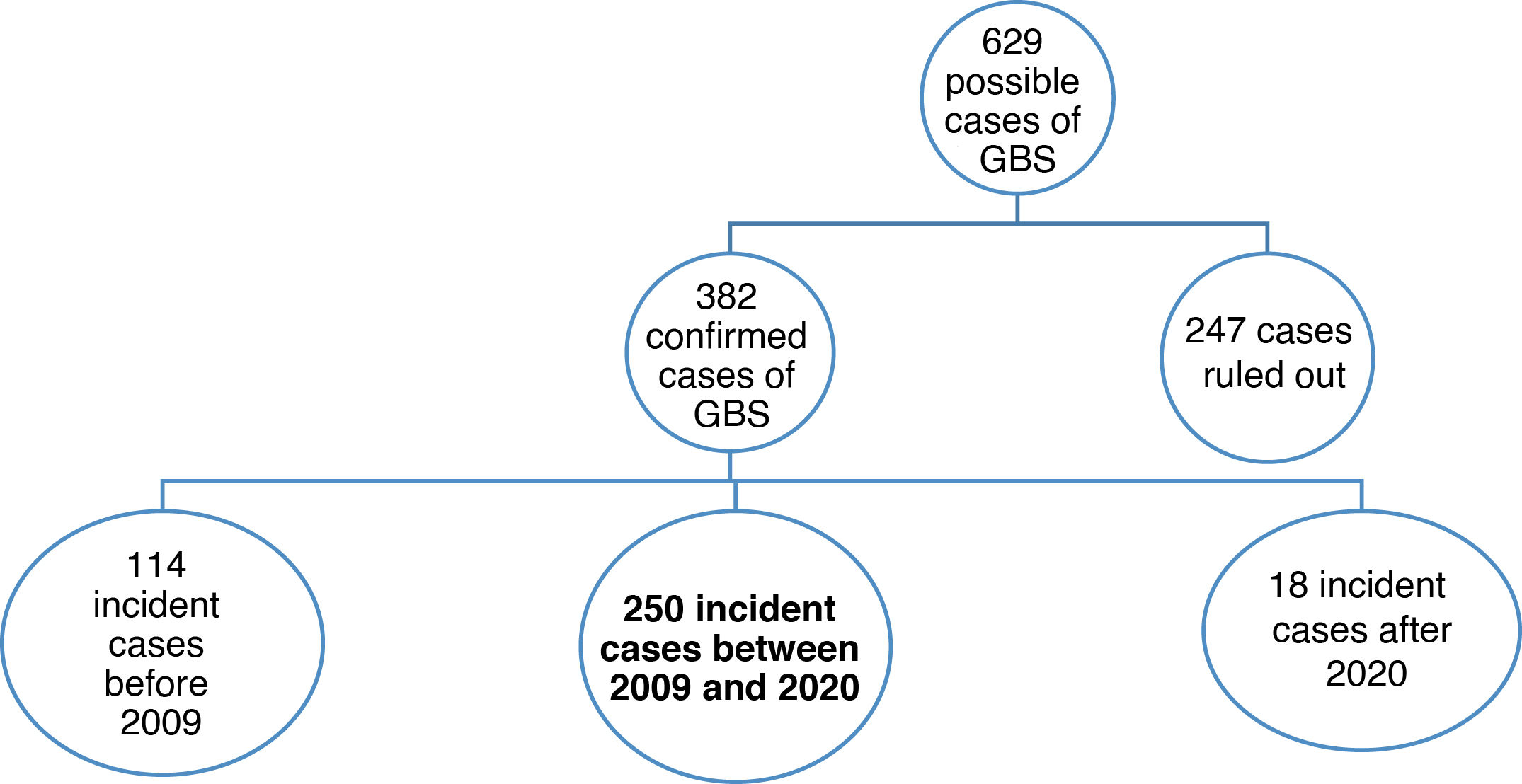

ResultsThe SIER included 629 potential cases of GBS. Diagnosis was confirmed in 382, with 250 of these being diagnosed between 2009 and 2020 (Fig. 2).

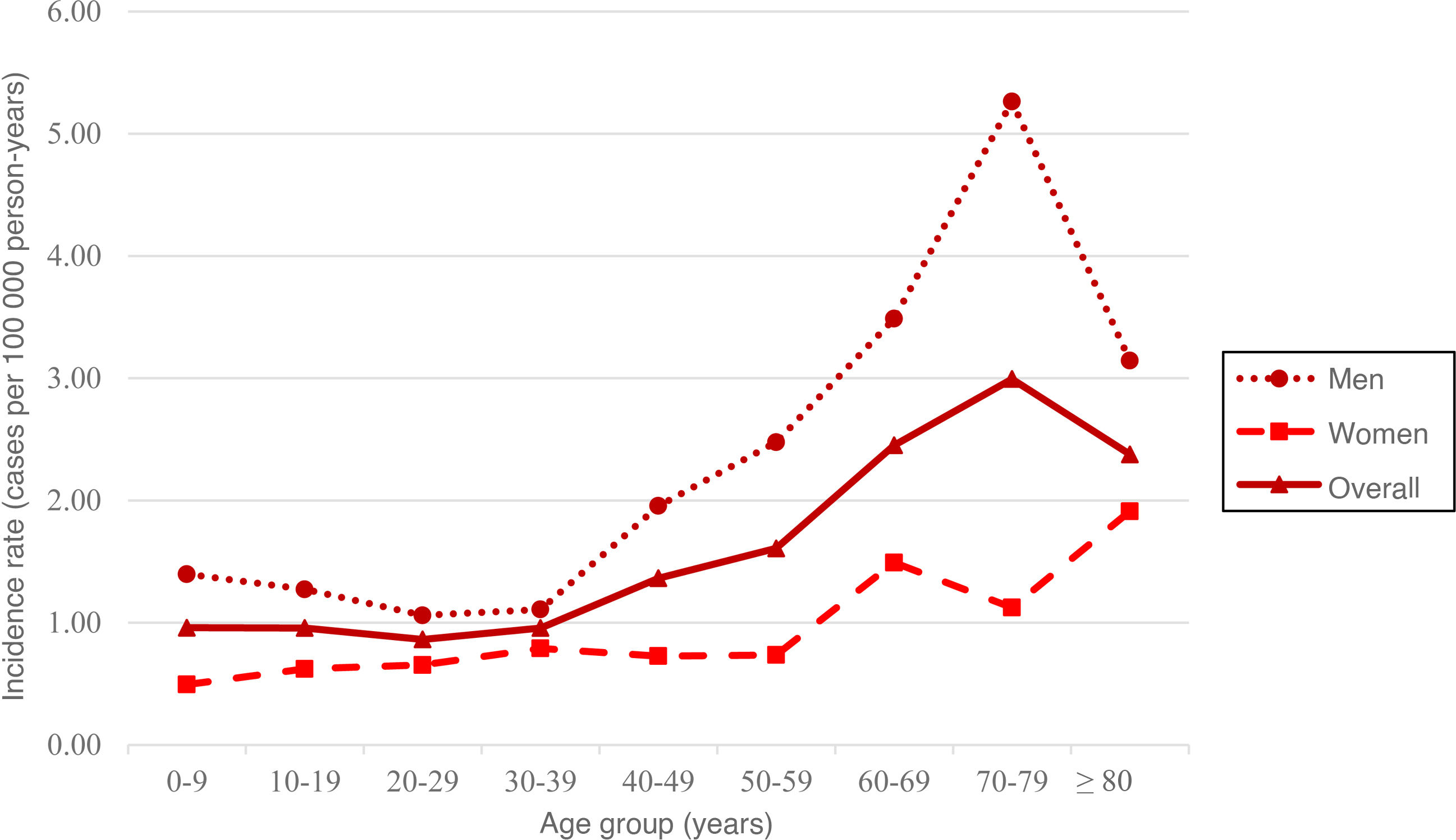

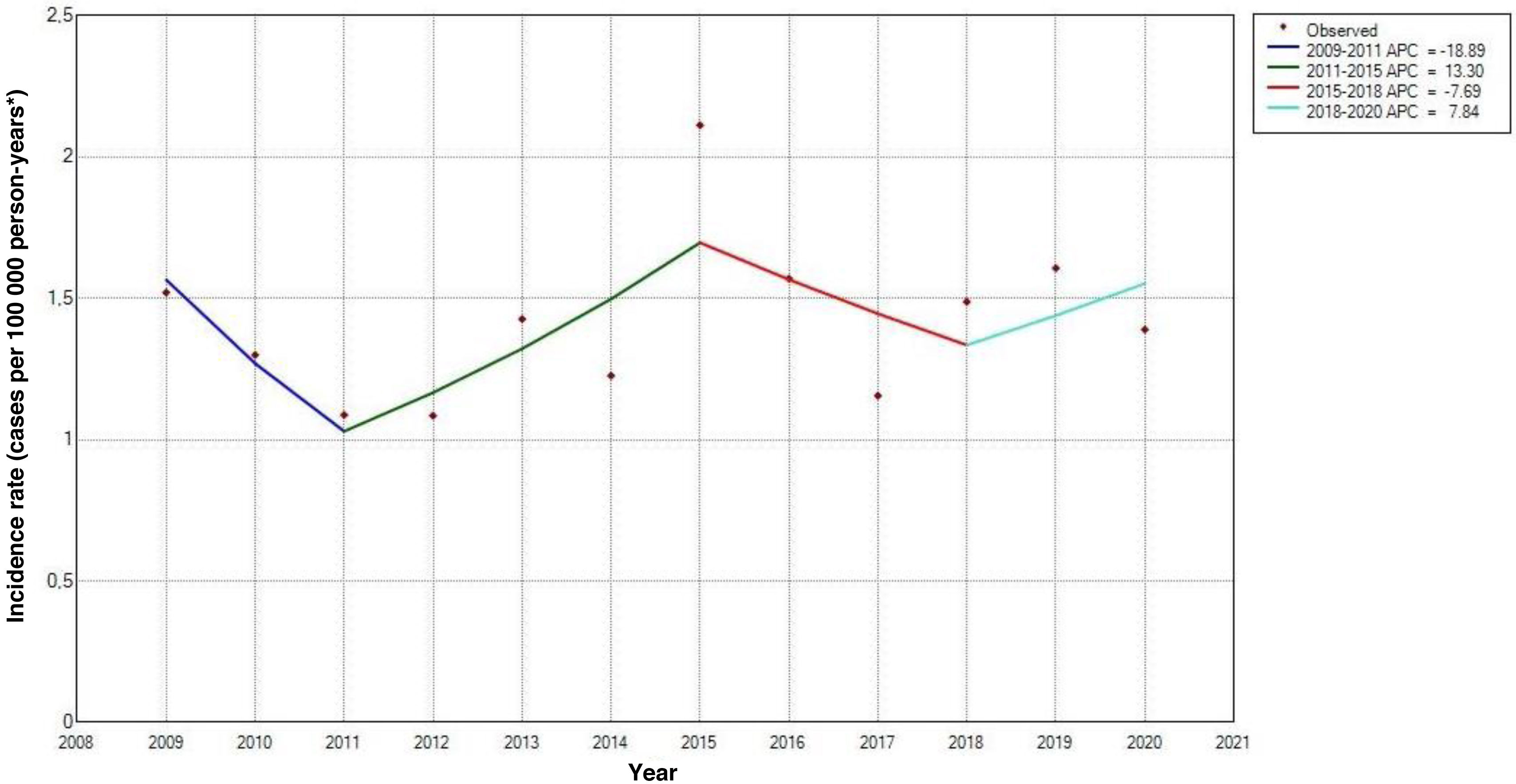

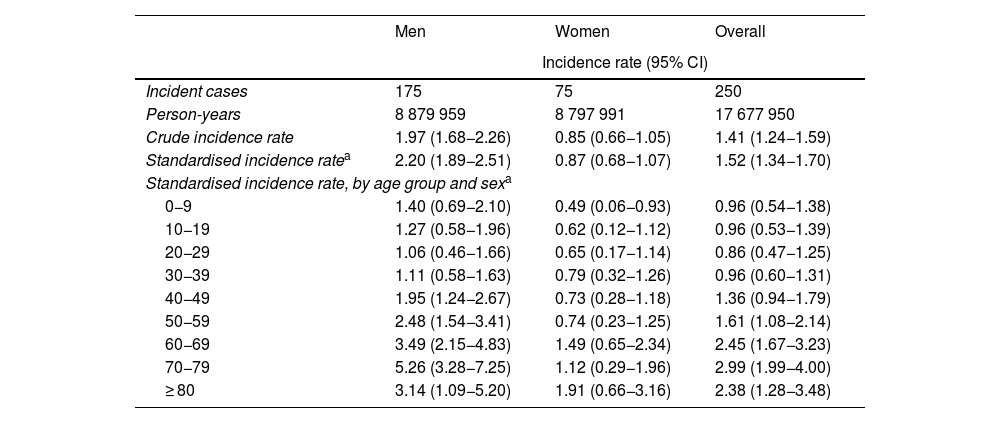

The standardised incidence rate (SIR) was 1.52 cases per 100 000 person-years (95% CI, 1.34−1.70); this rate was higher among men, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.53:1 (Table 1). Furthermore, incidence was observed to increase with age from the age group of 30−39 years, peaking at 70−79 years (SIR: 2.99; 95% CI, 1.99−4.00), followed by a generalised decrease due to the lower percentage of men in older age groups. In fact, among women the incidence peaked at the age of 80 years or older (SIR: 1.91; 95% CI, 0.66−3.16) (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Incidence rates of Guillain-Barré syndrome in the region of Murcia, by age group and sex (2009–2020).

| Men | Women | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence rate (95% CI) | |||

| Incident cases | 175 | 75 | 250 |

| Person-years | 8 879 959 | 8 797 991 | 17 677 950 |

| Crude incidence rate | 1.97 (1.68−2.26) | 0.85 (0.66−1.05) | 1.41 (1.24−1.59) |

| Standardised incidence ratea | 2.20 (1.89−2.51) | 0.87 (0.68−1.07) | 1.52 (1.34−1.70) |

| Standardised incidence rate, by age group and sexa | |||

| 0−9 | 1.40 (0.69−2.10) | 0.49 (0.06−0.93) | 0.96 (0.54−1.38) |

| 10−19 | 1.27 (0.58−1.96) | 0.62 (0.12−1.12) | 0.96 (0.53−1.39) |

| 20−29 | 1.06 (0.46−1.66) | 0.65 (0.17−1.14) | 0.86 (0.47−1.25) |

| 30−39 | 1.11 (0.58−1.63) | 0.79 (0.32−1.26) | 0.96 (0.60−1.31) |

| 40−49 | 1.95 (1.24−2.67) | 0.73 (0.28−1.18) | 1.36 (0.94−1.79) |

| 50−59 | 2.48 (1.54−3.41) | 0.74 (0.23−1.25) | 1.61 (1.08−2.14) |

| 60−69 | 3.49 (2.15−4.83) | 1.49 (0.65−2.34) | 2.45 (1.67−3.23) |

| 70−79 | 5.26 (3.28−7.25) | 1.12 (0.29−1.96) | 2.99 (1.99−4.00) |

| ≥ 80 | 3.14 (1.09−5.20) | 1.91 (0.66−3.16) | 2.38 (1.28−3.48) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

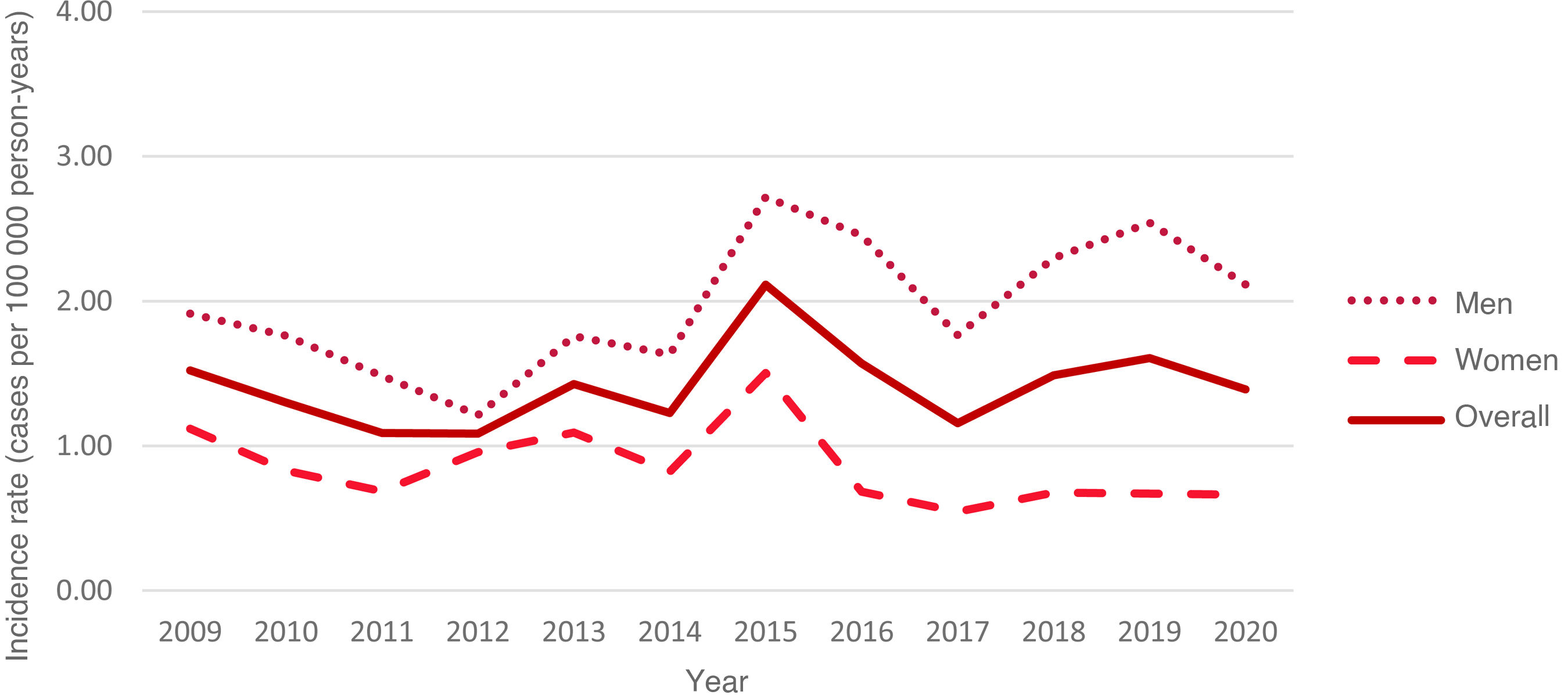

Over the study period, rates remained relatively stable for the total population, ranging from 1.52 cases per 100 000 person-years in 2009 (95% CI, 0.63-2.42) to 1.39 cases per 100 000 person-years in 2020 (95% CI, 0.55–2.23), with the highest rate being observed in 2015 (SIR: 2.11; 95% CI, 1.06–3.16) (Fig. 4). However, trend analysis identified no significant changes over the study period (P = .16) (Fig. 5).

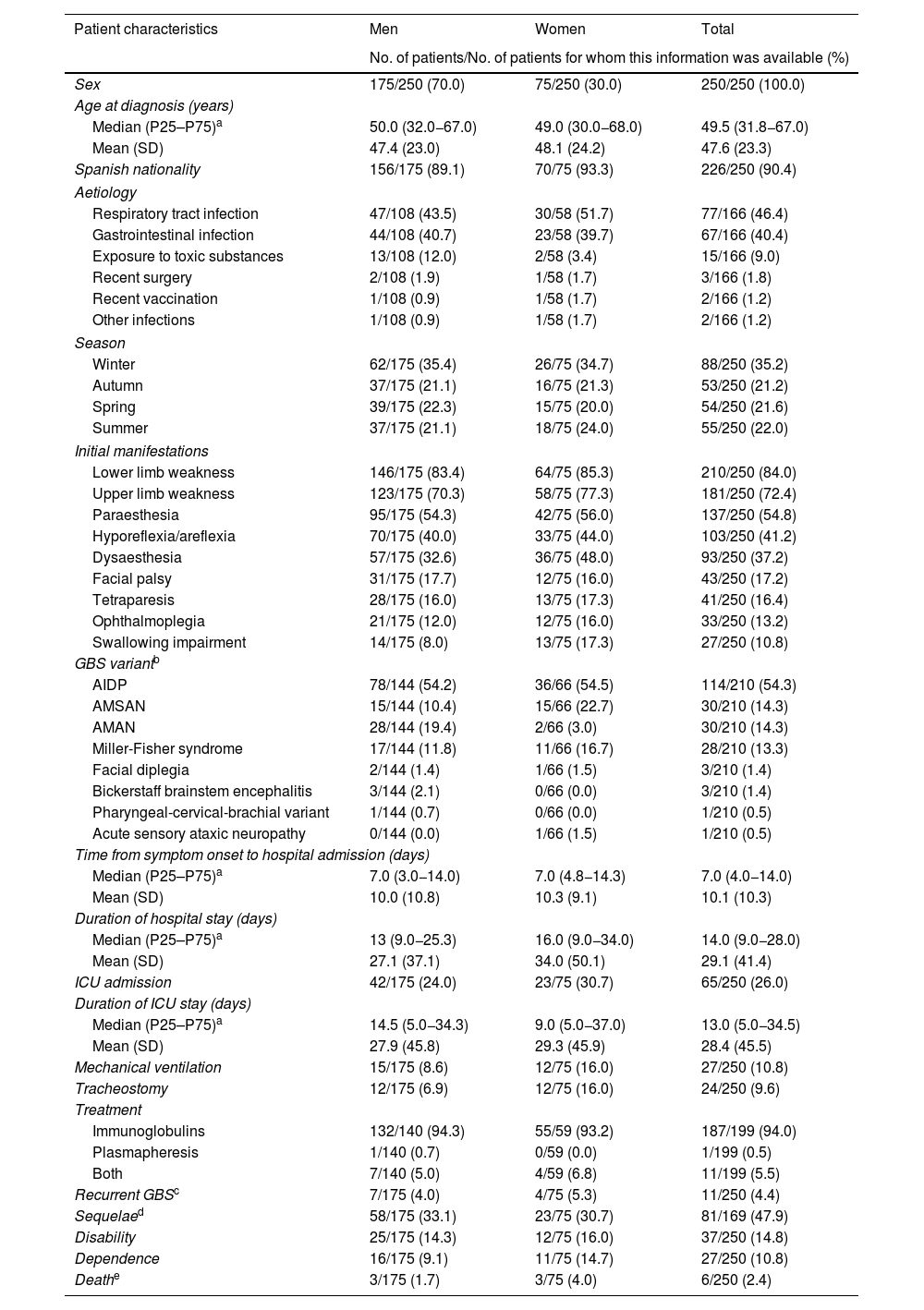

Table 2 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of our patients. Men accounted for 70% of the sample. Mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 47.6 (23.3) years. Of the patients for whom this information was available, respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections were the most common preceding factors (46.4% and 40.4%, respectively), with a slight predominance in cases occurring during the colder months (56.4%).

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome in the region of Murcia (2009–2020).

| Patient characteristics | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients/No. of patients for whom this information was available (%) | |||

| Sex | 175/250 (70.0) | 75/250 (30.0) | 250/250 (100.0) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| Median (P25–P75)a | 50.0 (32.0−67.0) | 49.0 (30.0−68.0) | 49.5 (31.8−67.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 47.4 (23.0) | 48.1 (24.2) | 47.6 (23.3) |

| Spanish nationality | 156/175 (89.1) | 70/75 (93.3) | 226/250 (90.4) |

| Aetiology | |||

| Respiratory tract infection | 47/108 (43.5) | 30/58 (51.7) | 77/166 (46.4) |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 44/108 (40.7) | 23/58 (39.7) | 67/166 (40.4) |

| Exposure to toxic substances | 13/108 (12.0) | 2/58 (3.4) | 15/166 (9.0) |

| Recent surgery | 2/108 (1.9) | 1/58 (1.7) | 3/166 (1.8) |

| Recent vaccination | 1/108 (0.9) | 1/58 (1.7) | 2/166 (1.2) |

| Other infections | 1/108 (0.9) | 1/58 (1.7) | 2/166 (1.2) |

| Season | |||

| Winter | 62/175 (35.4) | 26/75 (34.7) | 88/250 (35.2) |

| Autumn | 37/175 (21.1) | 16/75 (21.3) | 53/250 (21.2) |

| Spring | 39/175 (22.3) | 15/75 (20.0) | 54/250 (21.6) |

| Summer | 37/175 (21.1) | 18/75 (24.0) | 55/250 (22.0) |

| Initial manifestations | |||

| Lower limb weakness | 146/175 (83.4) | 64/75 (85.3) | 210/250 (84.0) |

| Upper limb weakness | 123/175 (70.3) | 58/75 (77.3) | 181/250 (72.4) |

| Paraesthesia | 95/175 (54.3) | 42/75 (56.0) | 137/250 (54.8) |

| Hyporeflexia/areflexia | 70/175 (40.0) | 33/75 (44.0) | 103/250 (41.2) |

| Dysaesthesia | 57/175 (32.6) | 36/75 (48.0) | 93/250 (37.2) |

| Facial palsy | 31/175 (17.7) | 12/75 (16.0) | 43/250 (17.2) |

| Tetraparesis | 28/175 (16.0) | 13/75 (17.3) | 41/250 (16.4) |

| Ophthalmoplegia | 21/175 (12.0) | 12/75 (16.0) | 33/250 (13.2) |

| Swallowing impairment | 14/175 (8.0) | 13/75 (17.3) | 27/250 (10.8) |

| GBS variantb | |||

| AIDP | 78/144 (54.2) | 36/66 (54.5) | 114/210 (54.3) |

| AMSAN | 15/144 (10.4) | 15/66 (22.7) | 30/210 (14.3) |

| AMAN | 28/144 (19.4) | 2/66 (3.0) | 30/210 (14.3) |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | 17/144 (11.8) | 11/66 (16.7) | 28/210 (13.3) |

| Facial diplegia | 2/144 (1.4) | 1/66 (1.5) | 3/210 (1.4) |

| Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis | 3/144 (2.1) | 0/66 (0.0) | 3/210 (1.4) |

| Pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant | 1/144 (0.7) | 0/66 (0.0) | 1/210 (0.5) |

| Acute sensory ataxic neuropathy | 0/144 (0.0) | 1/66 (1.5) | 1/210 (0.5) |

| Time from symptom onset to hospital admission (days) | |||

| Median (P25–P75)a | 7.0 (3.0−14.0) | 7.0 (4.8−14.3) | 7.0 (4.0−14.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 10.0 (10.8) | 10.3 (9.1) | 10.1 (10.3) |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | |||

| Median (P25–P75)a | 13 (9.0−25.3) | 16.0 (9.0−34.0) | 14.0 (9.0−28.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 27.1 (37.1) | 34.0 (50.1) | 29.1 (41.4) |

| ICU admission | 42/175 (24.0) | 23/75 (30.7) | 65/250 (26.0) |

| Duration of ICU stay (days) | |||

| Median (P25–P75)a | 14.5 (5.0−34.3) | 9.0 (5.0−37.0) | 13.0 (5.0−34.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 27.9 (45.8) | 29.3 (45.9) | 28.4 (45.5) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 15/175 (8.6) | 12/75 (16.0) | 27/250 (10.8) |

| Tracheostomy | 12/175 (6.9) | 12/75 (16.0) | 24/250 (9.6) |

| Treatment | |||

| Immunoglobulins | 132/140 (94.3) | 55/59 (93.2) | 187/199 (94.0) |

| Plasmapheresis | 1/140 (0.7) | 0/59 (0.0) | 1/199 (0.5) |

| Both | 7/140 (5.0) | 4/59 (6.8) | 11/199 (5.5) |

| Recurrent GBSc | 7/175 (4.0) | 4/75 (5.3) | 11/250 (4.4) |

| Sequelaed | 58/175 (33.1) | 23/75 (30.7) | 81/169 (47.9) |

| Disability | 25/175 (14.3) | 12/75 (16.0) | 37/250 (14.8) |

| Dependence | 16/175 (9.1) | 11/75 (14.7) | 27/250 (10.8) |

| Deathe | 3/175 (1.7) | 3/75 (4.0) | 6/250 (2.4) |

AIDP: acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; AMAN: acute motor axonal neuropathy; AMSAN: acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy; GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome; SD: standard deviation.

Sufficient information was available to classify the clinical variant of GBS in 84.0% of patients; the most frequent subtypes were AIDP (54.3%), AMSAN (14.3%), and AMAN (14.3%).

Mean time from symptom onset to hospital admission was 10.1 (10.3) days, with the most frequent symptoms being limb weakness and paraesthesia. The mean duration of hospital stay was 29.1 (41.4) days; 26.0% of patients were admitted to the ICU, with a mean length of ICU stay of 28.4 (45.5) days.

Furthermore, 79.6% of patients had received treatment, 4.4% presented recurrence, and 2.8% required transfer to Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos, most of whom were men (85.7%). Mortality due to GBS was confirmed in 6 cases (2.4%). A total of 46 patients had an officially recognised situation of disability and/or dependence (19 with disability, 9 with dependence, and 18 with both).

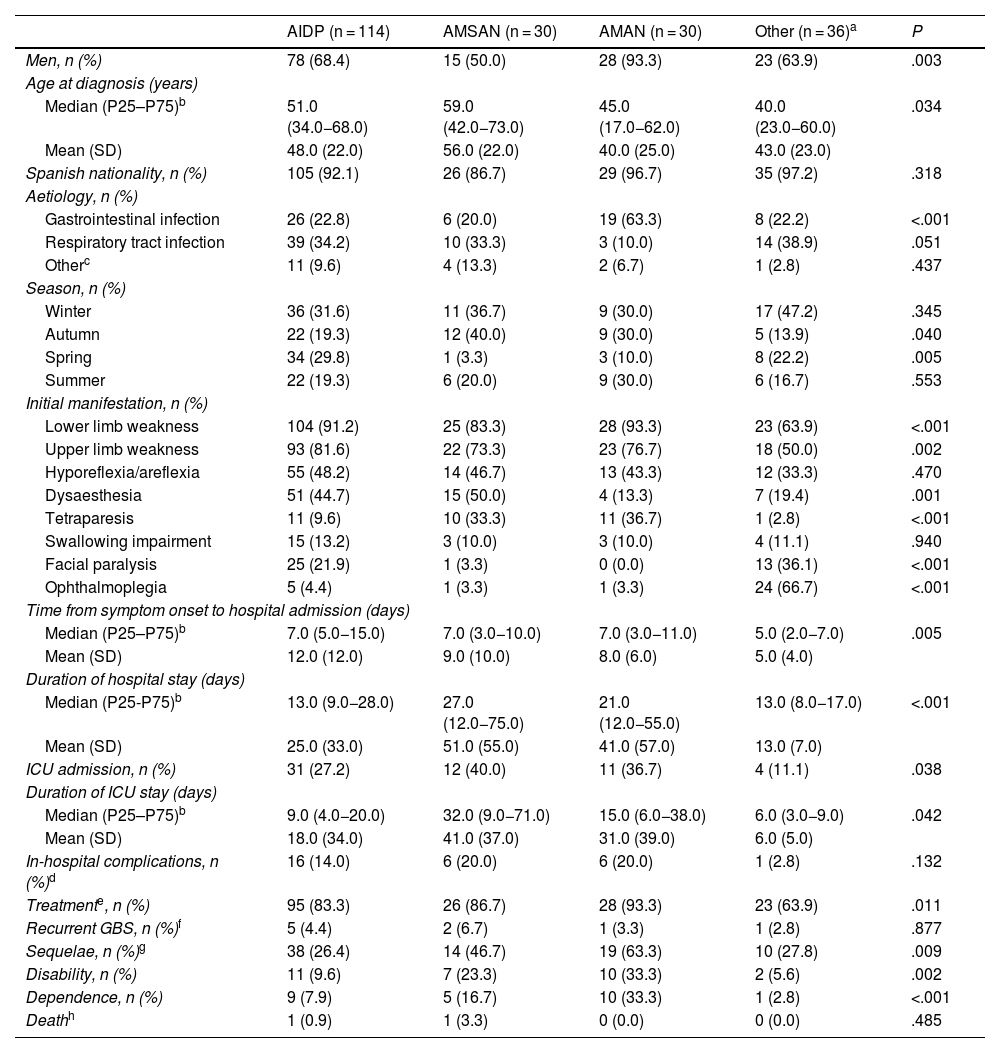

Table 3 describes the characteristics of our sample by GBS variant. Patients with axonal forms more frequently displayed tetraparesis as their initial manifestation, whereas patients with other variants (regional and functional) predominantly presented cranial nerve involvement. Likewise, axonal forms were associated with longer hospital stay, admission and stay at the ICU, greater need for treatment, greater incidence of sequelae, disability, and/or dependence; this association was statistically significant (P < .05). On the other hand, the AMAN variant was more frequent in men and was of gastrointestinal origin in most cases, whereas the AMSAN variant was more commonly observed among patients with older ages at diagnosis (P < .05).

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome in the region of Murcia, by variant (2009–2020).

| AIDP (n = 114) | AMSAN (n = 30) | AMAN (n = 30) | Other (n = 36)a | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 78 (68.4) | 15 (50.0) | 28 (93.3) | 23 (63.9) | .003 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||

| Median (P25–P75)b | 51.0 (34.0−68.0) | 59.0 (42.0−73.0) | 45.0 (17.0−62.0) | 40.0 (23.0−60.0) | .034 |

| Mean (SD) | 48.0 (22.0) | 56.0 (22.0) | 40.0 (25.0) | 43.0 (23.0) | |

| Spanish nationality, n (%) | 105 (92.1) | 26 (86.7) | 29 (96.7) | 35 (97.2) | .318 |

| Aetiology, n (%) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal infection | 26 (22.8) | 6 (20.0) | 19 (63.3) | 8 (22.2) | <.001 |

| Respiratory tract infection | 39 (34.2) | 10 (33.3) | 3 (10.0) | 14 (38.9) | .051 |

| Otherc | 11 (9.6) | 4 (13.3) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (2.8) | .437 |

| Season, n (%) | |||||

| Winter | 36 (31.6) | 11 (36.7) | 9 (30.0) | 17 (47.2) | .345 |

| Autumn | 22 (19.3) | 12 (40.0) | 9 (30.0) | 5 (13.9) | .040 |

| Spring | 34 (29.8) | 1 (3.3) | 3 (10.0) | 8 (22.2) | .005 |

| Summer | 22 (19.3) | 6 (20.0) | 9 (30.0) | 6 (16.7) | .553 |

| Initial manifestation, n (%) | |||||

| Lower limb weakness | 104 (91.2) | 25 (83.3) | 28 (93.3) | 23 (63.9) | <.001 |

| Upper limb weakness | 93 (81.6) | 22 (73.3) | 23 (76.7) | 18 (50.0) | .002 |

| Hyporeflexia/areflexia | 55 (48.2) | 14 (46.7) | 13 (43.3) | 12 (33.3) | .470 |

| Dysaesthesia | 51 (44.7) | 15 (50.0) | 4 (13.3) | 7 (19.4) | .001 |

| Tetraparesis | 11 (9.6) | 10 (33.3) | 11 (36.7) | 1 (2.8) | <.001 |

| Swallowing impairment | 15 (13.2) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (10.0) | 4 (11.1) | .940 |

| Facial paralysis | 25 (21.9) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (36.1) | <.001 |

| Ophthalmoplegia | 5 (4.4) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 24 (66.7) | <.001 |

| Time from symptom onset to hospital admission (days) | |||||

| Median (P25–P75)b | 7.0 (5.0−15.0) | 7.0 (3.0−10.0) | 7.0 (3.0−11.0) | 5.0 (2.0−7.0) | .005 |

| Mean (SD) | 12.0 (12.0) | 9.0 (10.0) | 8.0 (6.0) | 5.0 (4.0) | |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | |||||

| Median (P25-P75)b | 13.0 (9.0−28.0) | 27.0 (12.0−75.0) | 21.0 (12.0−55.0) | 13.0 (8.0−17.0) | <.001 |

| Mean (SD) | 25.0 (33.0) | 51.0 (55.0) | 41.0 (57.0) | 13.0 (7.0) | |

| ICU admission, n (%) | 31 (27.2) | 12 (40.0) | 11 (36.7) | 4 (11.1) | .038 |

| Duration of ICU stay (days) | |||||

| Median (P25–P75)b | 9.0 (4.0−20.0) | 32.0 (9.0−71.0) | 15.0 (6.0−38.0) | 6.0 (3.0−9.0) | .042 |

| Mean (SD) | 18.0 (34.0) | 41.0 (37.0) | 31.0 (39.0) | 6.0 (5.0) | |

| In-hospital complications, n (%)d | 16 (14.0) | 6 (20.0) | 6 (20.0) | 1 (2.8) | .132 |

| Treatmente, n (%) | 95 (83.3) | 26 (86.7) | 28 (93.3) | 23 (63.9) | .011 |

| Recurrent GBS, n (%)f | 5 (4.4) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (2.8) | .877 |

| Sequelae, n (%)g | 38 (26.4) | 14 (46.7) | 19 (63.3) | 10 (27.8) | .009 |

| Disability, n (%) | 11 (9.6) | 7 (23.3) | 10 (33.3) | 2 (5.6) | .002 |

| Dependence, n (%) | 9 (7.9) | 5 (16.7) | 10 (33.3) | 1 (2.8) | <.001 |

| Deathh | 1 (0.9) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | .485 |

AIDP: acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy; AMAN: acute motor axonal neuropathy; AMSAN: acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy; GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome; ICU: intensive care unit; SD: standard deviation.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Includes functional (acute sensory ataxic neuropathy) and regional variants of GBS (Miller-Fisher syndrome, Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis, bifacial weakness with paraesthesias, and pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant). Information on GBS variant was unavailable for 40 patients.

Includes exposure to toxic substances, recent history of surgery or vaccination, and other infections.

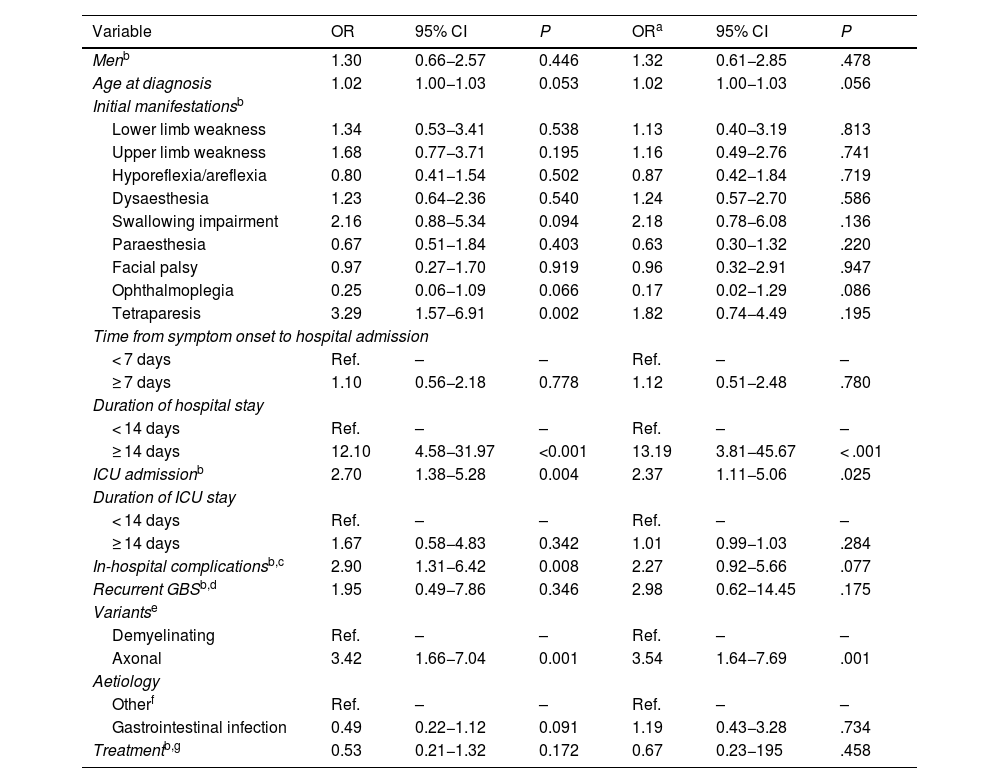

Table 4 shows the associations between patient characteristics and official recognition of disability and/or dependence due to GBS. Disability and dependence were more frequently recognised in patients with hospital stays ≥ 14 days (OR: 13.19; 95% CI, 3.81−45.67), those requiring admission to the ICU (OR: 2.37; 95% CI, 1.11−5.06), and patients with axonal forms of GBS (OR: 3.54; 95% CI, 1.64−7.69) (P < .05)

Multivariate analysis of the characteristics of our patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome and disease-related disability and/or dependence.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P | ORa | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menb | 1.30 | 0.66−2.57 | 0.446 | 1.32 | 0.61−2.85 | .478 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.02 | 1.00−1.03 | 0.053 | 1.02 | 1.00−1.03 | .056 |

| Initial manifestationsb | ||||||

| Lower limb weakness | 1.34 | 0.53−3.41 | 0.538 | 1.13 | 0.40−3.19 | .813 |

| Upper limb weakness | 1.68 | 0.77−3.71 | 0.195 | 1.16 | 0.49−2.76 | .741 |

| Hyporeflexia/areflexia | 0.80 | 0.41−1.54 | 0.502 | 0.87 | 0.42−1.84 | .719 |

| Dysaesthesia | 1.23 | 0.64−2.36 | 0.540 | 1.24 | 0.57−2.70 | .586 |

| Swallowing impairment | 2.16 | 0.88−5.34 | 0.094 | 2.18 | 0.78−6.08 | .136 |

| Paraesthesia | 0.67 | 0.51−1.84 | 0.403 | 0.63 | 0.30−1.32 | .220 |

| Facial palsy | 0.97 | 0.27−1.70 | 0.919 | 0.96 | 0.32−2.91 | .947 |

| Ophthalmoplegia | 0.25 | 0.06−1.09 | 0.066 | 0.17 | 0.02−1.29 | .086 |

| Tetraparesis | 3.29 | 1.57−6.91 | 0.002 | 1.82 | 0.74−4.49 | .195 |

| Time from symptom onset to hospital admission | ||||||

| < 7 days | Ref. | – | – | Ref. | – | – |

| ≥ 7 days | 1.10 | 0.56−2.18 | 0.778 | 1.12 | 0.51−2.48 | .780 |

| Duration of hospital stay | ||||||

| < 14 days | Ref. | – | – | Ref. | – | – |

| ≥ 14 days | 12.10 | 4.58−31.97 | <0.001 | 13.19 | 3.81−45.67 | < .001 |

| ICU admissionb | 2.70 | 1.38−5.28 | 0.004 | 2.37 | 1.11−5.06 | .025 |

| Duration of ICU stay | ||||||

| < 14 days | Ref. | – | – | Ref. | – | – |

| ≥ 14 days | 1.67 | 0.58−4.83 | 0.342 | 1.01 | 0.99−1.03 | .284 |

| In-hospital complicationsb,c | 2.90 | 1.31−6.42 | 0.008 | 2.27 | 0.92−5.66 | .077 |

| Recurrent GBSb,d | 1.95 | 0.49−7.86 | 0.346 | 2.98 | 0.62−14.45 | .175 |

| Variantse | ||||||

| Demyelinating | Ref. | – | – | Ref. | – | – |

| Axonal | 3.42 | 1.66−7.04 | 0.001 | 3.54 | 1.64−7.69 | .001 |

| Aetiology | ||||||

| Otherf | Ref. | – | – | Ref. | – | – |

| Gastrointestinal infection | 0.49 | 0.22−1.12 | 0.091 | 1.19 | 0.43−3.28 | .734 |

| Treatmentb,g | 0.53 | 0.21−1.32 | 0.172 | 0.67 | 0.23−195 | .458 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome; ICU: intensive care unit; OR: odds ratio.

Statistical significance was set at P ≤ .05.

Occurrence of at least 2 episodes meeting diagnostic criteria for GBS with complete or near-complete recovery after the initial episode, and a minimum interval of 2 months between episodes.

Demyelinating: acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, Miller-Fisher syndrome, Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis, bifacial weakness with paraesthesias, and acute sensory ataxic neuropathy. The pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant was excluded from the analysis as it was considered to present a mixed pattern (axonal and demyelinating).

Older age at diagnosis, longer ICU stay, swallowing alterations, tetraparesis at onset, in-hospital complications, and disease recurrence did not show statistically significant associations.

DiscussionThis is the only study performed to date in the region of Murcia analysing the incidence of GBS and the main characteristics of these patients, and the first to analyse factors associated with official recognition of a situation of disability or dependence. Furthermore, few studies have used information from a population-based registry including data from a long period.

The SIR of GBS in our population was estimated at 1.52 cases per 100 000 person-years. This rate is consistent with those reported in previous studies conducted in Spain,6,7 as well as in other European countries and the United States.24,25 According to our results, no significant trends were observed over the study period, and the incidence of GBS seems to increase with age, peaking at the age of 70−79 years and decreasing subsequently. Although most studies report that incidence rates begin to increase from the age of 50, in our study this occurred from the age range of 30−39 years; similar results have also been reported by other authors.26,27 We observed higher rates among men, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.53:1, in line with other studies.28,29 However, incidence of GBS among women peaks at the age of 80 years, as reported in the meta-analysis by Sejvar et al.4 and the study by Aragonès et al.30; both studies warn of the possibility that GBS may be underdiagnosed in this age group.

History of respiratory tract infection was the most frequent preceding factor in our sample; this finding is consistent with most other reports in the literature.27,31–33 However, gastrointestinal infection was observed in 40.4% of patients; this rate is higher than previously reported34,35 but is consistent with the data published by Aladro-Benito et al.7 and Piñol-Ripoll et al.36 However, in our study we did not collect data on the pathogen responsible for these infections; this would be an interesting future line of research.

Mean time from symptom onset to hospital admission and mean duration of hospital/ICU stay in our study are similar to those reported in the literature, although data vary slightly between series.9,12,34,37 Most patients (79.6%) had been treated with intravenous immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, or both, as described in previous studies,27,36 whereas 10.8% and 9.6% required mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy, respectively; these rates are lower than previously reported.7,28

Mortality due to GBS in our sample was 2.4%, a lower rate than those previously reported in Spain and other European countries (3%–7%).24,38,39 However, this analysis only considered patients whose clinical records identified GBS as the cause of death; this information may not have been available in some cases, which may explain the low mortality rate observed in our sample. This may also explain the small percentage of patients presenting certain symptoms at disease onset, such as areflexia, with a lower percentage than in most published studies.

Our results are also in line with those of studies conducted in Europe and North America regarding the predominance of AIDP, whose incidence has been reported to range from 60% to 90%.28,34,40,41 In our study, 54.3% of the patients for whom data were available on GBS variant had AIDP; however, the actual rate may be higher since 16% of patients could not be classified by type of GBS.

The multivariate analysis classified GBS variants as either axonal or demyelinating, as proposed by other authors.12,19 Axonal forms are believed to have poorer prognosis than demyelinating forms, as recovery in these patients is slower or incomplete.26,28,35 However, the relationship between the 2 forms of GBS and the long-term effects of the disease has not previously been addressed. According to our results, axonal forms, longer hospital stays, and ICU admission are associated with higher rates of disability and dependence.

Numerous studies suggest that high functional scale score, older age, and gastrointestinal aetiology may be associated with poor disease prognosis.8,9,30,38 In our study, however, these associations did not reach statistical significance.

Our study is not without limitations. Firstly, the relatively small size of our sample might potentially have resulted in type II errors; however, this was not the case, as we found statistically significant associations. Secondly, clinical and hospitalisation data were not available for all patients. In any case, no significant differences were observed between patients for whom this information was available or unavailable in terms of disability and dependence. The likelihood of information bias is therefore very low.

Disease progression time varied between patients, which may have had an impact on the official recognition of the situation of disability or dependence, as this process takes some time. In fact, mean time from diagnosis to the first disability assessment was 13 months; therefore, although data were gathered until 31 December 2021, some patients may have been assessed after that date. Furthermore, 3.2% of patients were classified as having no disability, since their degree of functional impairment was estimated to be below 33%.

The study did not evaluate patients’ performance on functional scales, which constitutes another limitation. It would be interesting to compare performance on such scales as the GBS Disability Score and the EGOS Score against disability and dependence assessment results as a measure of poor long-term prognosis.

Lastly, although we analysed a wide range of variables, some important variables were not considered, including cerebrospinal fluid analysis results or electrophysiological changes; these may be analysed in future studies. Likewise, although we gathered data on symptoms at disease onset, we did not analyse the symptoms appearing over the course of the disease, which may have provided interesting information.

One of the strengths of this study is the fact that data were gathered from a population-based registry providing representative, updated information on patients with GBS, which allowed us to analyse the frequency, distribution, and characteristics of these patients. Future studies should analyse the factors evaluated in our study using a similar methodology, but including a larger sample, with a view to confirming our results.

Our results provide insight into the impact of GBS on public health and enable healthcare resource planning, contributing to the development of strategies to optimise healthcare provision for these patients.

ConclusionsThe SIR of GBS in the region of Murcia is in line with the rates reported in other studies conducted in Spain and in other countries. Although GBS is an acute condition, 18.4% of our patients had officially recognised disability and/or dependence; this was more common among those with axonal forms. Likewise, longer hospital stays and ICU admission were found to be more frequently associated with official recognition of the situation of disability and/or dependence.

CrediT authorship contribution statementSRN and MPME designed and initiated the study. MPME, JAPR, and PCM coordinated information filtering and administered the SIER. PCM was responsible for database maintenance. MPME and ASE validated and confirmed diagnosis of the disease. SRN, MPME, ASE, and LAMR classified patients according to disease variant. ASE gathered patient demographic and clinical data. SRN and MPME performed the data analysis. MPME and SRN drafted the manuscript. JMCF assisted in manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Legal and ethical considerationsPatient informed consent was not required as the SIER is listed as an exception under personal data protection legislation on public health actions related to rare diseases in the region of Murcia.

Declaration of originalityThis is an original study. It has not been published in any other journal nor is it under consideration for publication by any other journal.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Data availabilityThe set of pseudoanonymised data used in this study are protected under Regulation (EU) 2016/679; Spanish Organic Law 3/2018, on personal data protection and digital rights; Spanish Law 14/2007, on biomedical research; and Spanish Laws 37/2077 and 18/2015, on the reuse of public sector information. Therefore, access may be granted to aggregate data only, upon reasonable request to serplan@listas.carm.es.

None.

We wish to thank all the healthcare professionals providing data to the SIER, as well as the personnel of the Health Planning and Funding Service, who are responsible for maintaining the database. We also thank Jesús Arense Gonzalo, Associate Professor at the Department of Social Health Sciences of the University of Murcia, and Pablo Herrero Bastida, neurology resident at Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, for their assistance and advice.