X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM) is a severe, rare, familial neuromuscular disease caused by mutations in the MTM1 gene. XLMTM presents a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, including neuromuscular symptoms such as hypotonia and severe generalised muscle weakness, which lead to respiratory and orthopaedic complications; and extramuscular manifestations such as hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal involvement. As there is no curative treatment for XLMTM, and given the complications associated with the disease and its high morbidity and mortality, survival and quality of life in these patients rely on a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach.

MethodsA group of paediatric neurologists, one pulmonologist, one hepatologist, one intensivist, and rehabilitation specialists from Spain and Portugal with in-depth understanding and experience in XLMTM management present a multicentre series of 24 patients with XLMTM and problems and experience on its clinical management.

ResultsSevere phenotypes showed significant neuromuscular and non-neuromuscular involvement. Multidisciplinary management, including respiratory support, nutritional interventions, and rehabilitation, is essential. Unmet needs include better neurocognitive assessment tools, improved access to multidisciplinary care, and resources for physical therapy. Communication aids are crucial for patient development.

ConclusionMultidisciplinary management of XLMTM is essential for improving outcomes, with significant unmet needs in several areas of clinical care.

La miopatía miotubular ligada al cromosoma X (XLMTM) es una enfermedad neuromuscular hereditaria, rara y grave, causada por mutaciones en el gen MTM1. La XLMTM presenta un amplio espectro de manifestaciones clínicas, incluidas manifestaciones neuromusculares como hipotonía y debilidad muscular generalizada severa, que llevan a complicaciones respiratorias y ortopédicas, así como manifestaciones extramusculares como afectación hepatobiliar y gastrointestinal. Dado que no existe un tratamiento curativo para la XLMTM, y considerando las complicaciones asociadas con la enfermedad y su alta morbimortalidad, la supervivencia y la calidad de vida de estos pacientes dependen de un enfoque integral y multidisciplinario.

MétodosUn grupo de neurólogos pediátricos, un neumólogo, un hepatólogo, un intensivista y especialistas en rehabilitación de España y Portugal, con un conocimiento profundo y experiencia en XLMTM, presentan una serie de casos multicéntrica de 24 pacientes con XLMTM, discutiendo los problemas y la experiencia en el manejo clínico.

ResultadosLos fenotipos severos mostraron síntomas neuromusculares y no neuromusculares significativos. La gestión multidisciplinaria, incluyendo el apoyo respiratorio, intervenciones nutricionales y rehabilitación, es esencial. Las necesidades no satisfechas incluyen mejores herramientas de evaluación neurocognitiva, mejor acceso a cuidados multidisciplinarios y recursos para fisioterapia. Las ayudas para la comunicación son cruciales para el desarrollo de los pacientes.

ConclusiónEl manejo multidisciplinar es esencial para mejorar los resultados en la XLMTM, con necesidades no cubiertas significativas en varias áreas del cuidado clínico.

X-linked myotubular myopathy (XLMTM) is a severe, rare genetic neuromuscular disease linked to the X chromosome. It is caused by mutations in the MTM1 gene, which encodes the enzyme myotubularin. As MTM1 is mainly expressed in skeletal muscles, XLMTM mainly results in a wide range of neuromuscular symptoms such as hypotonia and muscle weakness, which lead to respiratory and orthopaedic complications. However, MTM1 is also expressed in other tissues, and recent studies have identified extramuscular manifestations of the disease, including hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal involvement.1,2

Around 90% of patients with XLMTM present with gastrointestinal and feeding difficulties.3 Other gastrointestinal comorbidities are also prevalent, such as constipation or pyloric stenosis.4 Liver involvement is very frequent in these patients, with recent studies reporting incidence of up to 91%.4 The most frequently reported hepatic abnormality reported is peliosis hepatis, a potentially fatal vascular lesion characterised by blood-filled cystic cavities, which affects between 5% and 10% of patients.5-7 However, improvements in the characterisation of the hepatobiliary pathology have allowed clinicians to detect other presentations: cholestasis, cholelithiasis, elevated transaminases, hepatomegaly,8 etc. In a recent study, several patients diagnosed with XLMTM presented intrahepatic cholestasis,9 which was associated with various MTM1 gene mutations and presented at between 7 and 16 months after birth. All patients responded well to cholestasis treatment. These new data suggest that myotubularin plays a role in the synthesis and excretion of bile acids.

The incidence and prevalence of XLMTM vary depending on the geographic area and the patient group, with the disease affecting approximately 1 in 50000 boys.2,10 This figure, however, most probably underestimates the true incidence and prevalence of all phenotypes of disease, as it does not include late-onset cases and girls with manifestations of XLMTM.2,11 Early-onset XLMTM shows a high early mortality rate (between 25% and 50% of patients die within the first year of life)1,5,6 and high morbidity due to the frequent need for hospitalisation and surgery in severe phenotypes. It also places a considerable burden on the healthcare system as a whole, insofar as patients are highly dependent on healthcare services and need to be treated by several different specialists and care providers. Eighty percent of patients with severe manifestations of the disease are dependent on mechanical ventilation (MV) for more than 12h per day, require an enterostomy tube for enteral feeding, rely on wheelchairs, and need assistance for all activities of daily living.12

Patients with XLMTM are usually classified according to the clinical classification proposed by Herman et al.7 Although it is useful and widely applied, this classification shows some limitations, with the most significant being: (1) it divides a phenotypic continuum into classes, while there are patients who are difficult to categorise and (2) it assumes that dimensions of motor, respiratory, and bulbar severity are well correlated within the same patients, which is not necessarily true in all patients. This classification divides XLMTM patients into three phenotypes, based on clinical severity and dependence on MV:

- (a)

Patients with the severe phenotype require 12h or more per day of MV and present hypotonia, hypomimia, generalised muscle weakness, ophthalmoplegia, and dysphagia. These symptoms are usually observed at the time of birth, and present as respiratory failure with or without history of perinatal asphyxia.5 In most cases, patients develop chronic respiratory failure at an early age, with respiratory failure and death occurring in the early years of life.1,5,6

- (b)

The moderate phenotype requires less than 12h per day of MV and presents milder muscular symptoms.

- (c)

Patients with the mild phenotype do not require MV, but their neuromuscular symptoms are similar to those of the moderate phenotype.4

Diagnosis of XLMTM should be based on clinical manifestations, biopsy findings, and genetic testing. After noting the clinical signs and symptoms, a muscle biopsy is usually taken for histological study. However, this diagnostic technique is falling into disuse due to the widespread availability of next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques. If a muscle biopsy study is performed, diagnosis can be based on the following histological findings: abnormal placement of the nucleus and a predominance of small type I fibres, mislocalisation of mitochondria and other sarcotubular elements, and the progressive appearance of necklace fibres over time.1,13

Real-world observational studies3,4,12 in XLMTM have contributed fundamental knowledge that has been used to define the key clinical characteristics of the disease and its natural history and progression during childhood and adulthood. There is currently no curative treatment for the disease, and survival and quality of life depend on an integral approach to management and early detection and prevention of the principal complications.

In this article, a group of paediatric neurologists, pulmonologists, hepatologists, intensivists, and rehabilitation specialists from Spain and Portugal analysed a series of 24 cases of XLMTM, focusing on the multidisciplinary management of these patients.

MethodsWe collected data from patients who were followed up at different centres in Spain and Portugal. We collected data on age at the last visit, age at diagnosis, detailed clinical presentation and motor manifestations, diagnosis method and detected mutation, the presence of symptoms or of the mutation in other family members, respiratory manifestations and intervention, gastrointestinal manifestations and management, and physical and orthopaedic manifestations. All patients were presented at a roundtable in March 2023 by a paediatric neurologist involved in the care of the patient, and manifestations and management were discussed within the group. DGA and CO collected the information and proposed a summary of a proposed management. This summary was shared with the rest of the authors, who provided corrections and feedback to refine the initial draft of this article.

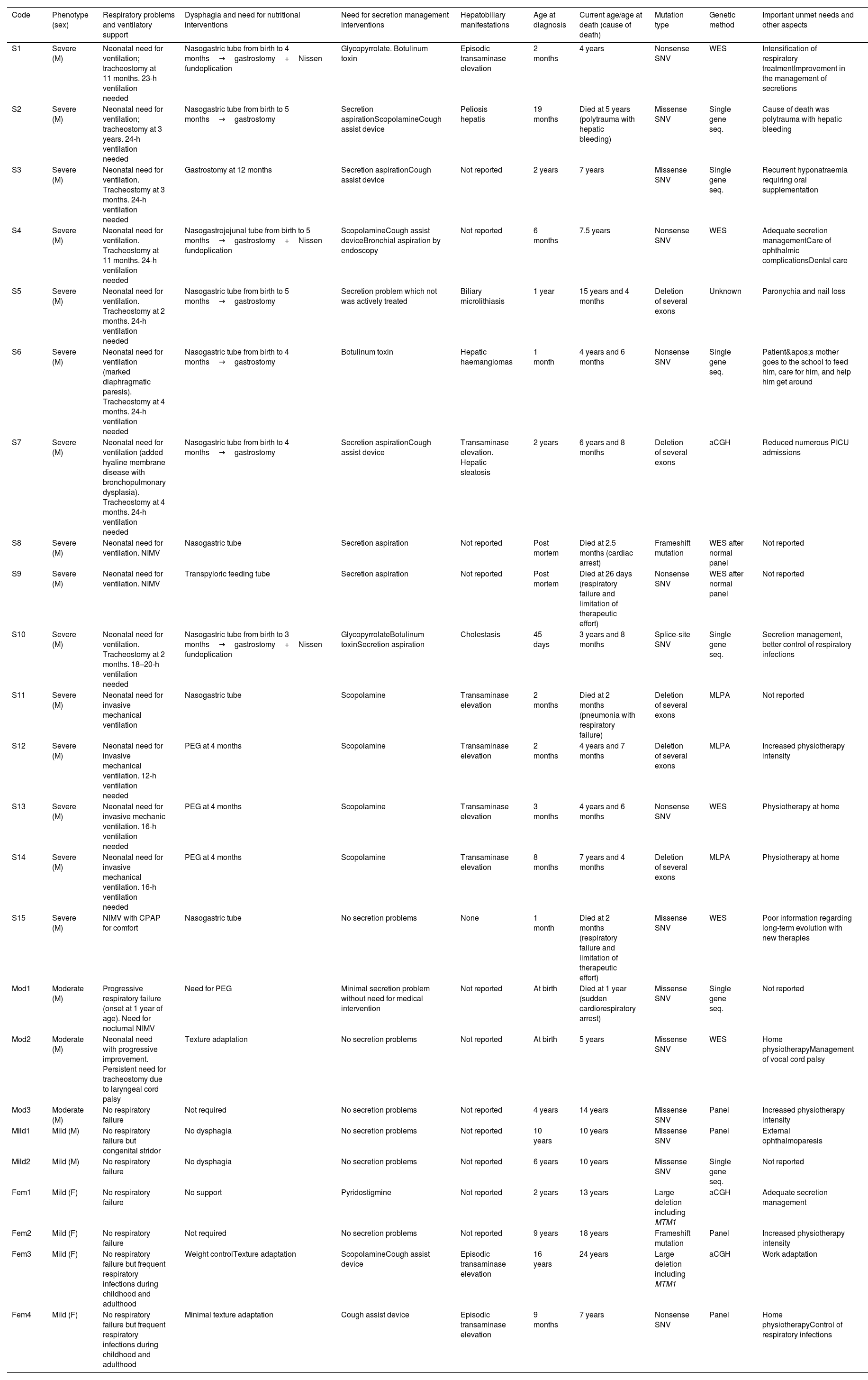

ResultsClinical manifestations of XLMTMThe most frequent clinical manifestations and the different phenotypes are discussed below and are exemplified in the cases shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. We collected data from 24 cases diagnosed in Spain and Portugal. Twenty of these patients were male (15 with a severe phenotype, 3 with a moderate phenotype, and 2 with a mild phenotype) and 4 were female carriers with mild-to-moderate phenotypes. At the time of writing, 18 of the 24 patients described here are still alive, and range in age from 4 to 24 years.

Clinical manifestations, genetic features, and therapeutic approach in our series of patients with XLMTM. Patients are ordered according to their phenotype. Further information is included in the Supplementary Materials.

| Code | Phenotype (sex) | Respiratory problems and ventilatory support | Dysphagia and need for nutritional interventions | Need for secretion management interventions | Hepatobiliary manifestations | Age at diagnosis | Current age/age at death (cause of death) | Mutation type | Genetic method | Important unmet needs and other aspects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation; tracheostomy at 11 months. 23-h ventilation needed | Nasogastric tube from birth to 4 months→gastrostomy+Nissen fundoplication | Glycopyrrolate. Botulinum toxin | Episodic transaminase elevation | 2 months | 4 years | Nonsense SNV | WES | Intensification of respiratory treatmentImprovement in the management of secretions |

| S2 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation; tracheostomy at 3 years. 24-h ventilation needed | Nasogastric tube from birth to 5 months→gastrostomy | Secretion aspirationScopolamineCough assist device | Peliosis hepatis | 19 months | Died at 5 years (polytrauma with hepatic bleeding) | Missense SNV | Single gene seq. | Cause of death was polytrauma with hepatic bleeding |

| S3 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation. Tracheostomy at 3 months. 24-h ventilation needed | Gastrostomy at 12 months | Secretion aspirationCough assist device | Not reported | 2 years | 7 years | Missense SNV | Single gene seq. | Recurrent hyponatraemia requiring oral supplementation |

| S4 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation. Tracheostomy at 11 months. 24-h ventilation needed | Nasogastrojejunal tube from birth to 5 months→gastrostomy+Nissen fundoplication | ScopolamineCough assist deviceBronchial aspiration by endoscopy | Not reported | 6 months | 7.5 years | Nonsense SNV | WES | Adequate secretion managementCare of ophthalmic complicationsDental care |

| S5 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation. Tracheostomy at 2 months. 24-h ventilation needed | Nasogastric tube from birth to 5 months→gastrostomy | Secretion problem which not was actively treated | Biliary microlithiasis | 1 year | 15 years and 4 months | Deletion of several exons | Unknown | Paronychia and nail loss |

| S6 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation (marked diaphragmatic paresis). Tracheostomy at 4 months. 24-h ventilation needed | Nasogastric tube from birth to 4 months→gastrostomy | Botulinum toxin | Hepatic haemangiomas | 1 month | 4 years and 6 months | Nonsense SNV | Single gene seq. | Patient's mother goes to the school to feed him, care for him, and help him get around |

| S7 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation (added hyaline membrane disease with bronchopulmonary dysplasia). Tracheostomy at 4 months. 24-h ventilation needed | Nasogastric tube from birth to 4 months→gastrostomy | Secretion aspirationCough assist device | Transaminase elevation. Hepatic steatosis | 2 years | 6 years and 8 months | Deletion of several exons | aCGH | Reduced numerous PICU admissions |

| S8 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation. NIMV | Nasogastric tube | Secretion aspiration | Not reported | Post mortem | Died at 2.5 months (cardiac arrest) | Frameshift mutation | WES after normal panel | Not reported |

| S9 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation. NIMV | Transpyloric feeding tube | Secretion aspiration | Not reported | Post mortem | Died at 26 days (respiratory failure and limitation of therapeutic effort) | Nonsense SNV | WES after normal panel | Not reported |

| S10 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for ventilation. Tracheostomy at 2 months. 18–20-h ventilation needed | Nasogastric tube from birth to 3 months→gastrostomy+Nissen fundoplication | GlycopyrrolateBotulinum toxinSecretion aspiration | Cholestasis | 45 days | 3 years and 8 months | Splice-site SNV | Single gene seq. | Secretion management, better control of respiratory infections |

| S11 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for invasive mechanical ventilation | Nasogastric tube | Scopolamine | Transaminase elevation | 2 months | Died at 2 months (pneumonia with respiratory failure) | Deletion of several exons | MLPA | Not reported |

| S12 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for invasive mechanical ventilation. 12-h ventilation needed | PEG at 4 months | Scopolamine | Transaminase elevation | 2 months | 4 years and 7 months | Deletion of several exons | MLPA | Increased physiotherapy intensity |

| S13 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for invasive mechanic ventilation. 16-h ventilation needed | PEG at 4 months | Scopolamine | Transaminase elevation | 3 months | 4 years and 6 months | Nonsense SNV | WES | Physiotherapy at home |

| S14 | Severe (M) | Neonatal need for invasive mechanical ventilation. 16-h ventilation needed | PEG at 4 months | Scopolamine | Transaminase elevation | 8 months | 7 years and 4 months | Deletion of several exons | MLPA | Physiotherapy at home |

| S15 | Severe (M) | NIMV with CPAP for comfort | Nasogastric tube | No secretion problems | None | 1 month | Died at 2 months (respiratory failure and limitation of therapeutic effort) | Missense SNV | WES | Poor information regarding long-term evolution with new therapies |

| Mod1 | Moderate (M) | Progressive respiratory failure (onset at 1 year of age). Need for nocturnal NIMV | Need for PEG | Minimal secretion problem without need for medical intervention | Not reported | At birth | Died at 1 year (sudden cardiorespiratory arrest) | Missense SNV | Single gene seq. | Not reported |

| Mod2 | Moderate (M) | Neonatal need with progressive improvement. Persistent need for tracheostomy due to laryngeal cord palsy | Texture adaptation | No secretion problems | Not reported | At birth | 5 years | Missense SNV | WES | Home physiotherapyManagement of vocal cord palsy |

| Mod3 | Moderate (M) | No respiratory failure | Not required | No secretion problems | Not reported | 4 years | 14 years | Missense SNV | Panel | Increased physiotherapy intensity |

| Mild1 | Mild (M) | No respiratory failure but congenital stridor | No dysphagia | No secretion problems | Not reported | 10 years | 10 years | Missense SNV | Panel | External ophthalmoparesis |

| Mild2 | Mild (M) | No respiratory failure | No dysphagia | No secretion problems | Not reported | 6 years | 10 years | Missense SNV | Single gene seq. | Not reported |

| Fem1 | Mild (F) | No respiratory failure | No support | Pyridostigmine | Not reported | 2 years | 13 years | Large deletion including MTM1 | aCGH | Adequate secretion management |

| Fem2 | Mild (F) | No respiratory failure | Not required | No secretion problems | Not reported | 9 years | 18 years | Frameshift mutation | Panel | Increased physiotherapy intensity |

| Fem3 | Mild (F) | No respiratory failure but frequent respiratory infections during childhood and adulthood | Weight controlTexture adaptation | ScopolamineCough assist device | Episodic transaminase elevation | 16 years | 24 years | Large deletion including MTM1 | aCGH | Work adaptation |

| Fem4 | Mild (F) | No respiratory failure but frequent respiratory infections during childhood and adulthood | Minimal texture adaptation | Cough assist device | Episodic transaminase elevation | 9 months | 7 years | Nonsense SNV | Panel | Home physiotherapyControl of respiratory infections |

aCGH: array comparative genomic hybridisation; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; F: female; M: male; MLPA: multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification; NIMV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation; PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PICU: paediatric intensive care unit; seq.: sequencing; SNV: single-nucleotide variation; WES: whole exome sequencing; XLMTM: X-linked myotubular myopathy.

The disease usually presents at a very early age, shortly after birth (Supplementary Table 1). Presence of polyhydramnios was frequent, and two of the patients were born prematurely. At birth, some patients presented specific symptoms suggestive of a primary neuromuscular disease.

Neuromuscular manifestationsThe neuromuscular manifestations detected in the patients, described in Table 1, are consistent with the typical presentation of XLMTM, i.e., severe, diffuse muscle weakness and hypotonia manifesting in the neonatal period. However, some of these symptoms may be masked by other symptoms and systemic manifestations, such as persistent respiratory symptoms. Patients with severe phenotypes present severe weakness and hypotonia, absent reflexes, few spontaneous movements, congenital limb deformities, cranial malformations, and different orofacial manifestations, including hypomimia, ptosis, ophthalmoparesis, or retrognathia (Supplementary Table 1). In patients with intermediate and mild phenotypes, the most frequent neuromuscular manifestations observed are hypotonia, muscle weakness, and motor clumsiness.

Scoliosis was detected in 6 patients with a severe phenotype, one of whom also presented hip dysplasia. These manifestations are consistent with those described elsewhere in the literature.12

Systemic manifestationsRespiratory manifestationsThe severe phenotype is determined by the severity of respiratory manifestations. As shown in Table 1, patients with a severe phenotype had respiratory distress and failure at birth, with 9 having no sign of spontaneous respiratory movements. In one patient, respiratory failure developed over time. These patients often present with recurrent infections and/or atelectasis.

Gastrointestinal and oromotor manifestationsPatients with a severe phenotype have significant difficulties in sucking, chewing, and swallowing, and often present with gastrointestinal disorders that require interventions to ensure adequate nutrition. Only 5 of our 24 patients were free of any kind of feeding adaptation (2 female patients, 1 moderate case and the 2 mild cases). Three patients required texture adaptation (2 of the 4 symptomatic female patients and 1 of the 3 moderate cases). The remaining patients needed a nasogastric or nasogastrojejunal tube and, if they survived, a gastrostomy.

Hepatobiliary manifestationsEight patients (Table 1) presented hypertransaminasaemia without liver dysfunction (one of these presented hepatic steatosis, detected by ultrasound), one presented hepatic haemangiomas, one presented cholestasis, and one presented biliary microlithiasis. Increased liver enzyme levels seem to be unrelated to presence of the motor phenotype in mild cases in boys and in female patients.

Other manifestationsOther comorbidities were found in some patients, such as one case of severe bradycardia due to sinus node dysfunction, requiring pacemaker implantation; one case of grade IV intraventricular haemorrhage secondary to premature birth, requiring implantation of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (DVP); and one case of kidney involvement with lithiasis and nephrocalcinosis (Supplementary Table 1). A common manifestation in boys was bilateral and unilateral cryptorchidism (with one patient requiring left orchidopexy).

Manifestations in symptomatic female carriersFour patients in our series were symptomatic female carriers of XLMTM with a milder phenotype. In case FEM1, like others described in the literature, the patient was stable with no motor complications. In case FEM2, the patient presented mild axial hypotonia, muscular diameter asymmetry, and facial hypotrophy. Patient FEM3 started with early hypotonia in the context of a mild hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy, but clinical phenotype was not consistent with a central disorder, and EMG and muscle biopsy were performed. Patient FEM4 presented with a congenital myopathy and the mutation was identified in a gene panel. Symptoms included motor retardation, symmetric muscle weakness and amyotrophy, fatigue, proximal muscle weakness, and occasional elevation of creatine phosphokinase (CPK), myogenic electromyography, and findings compatible with XLMTM in the muscle biopsy. Extensive Xq28 deletions were found in 2 patients, who presented neuromuscular symptoms, no respiratory symptoms, hypotonia, generalised muscle weakness, and orofacial involvement; another patient presented a frameshift mutation in MTM1 in heterozygosis (c.960del; p.Asp310Glufs); the last patient presented a missense mutation in the MTM1 domain in heterozygosis.

Diagnosis of XLMTMTable 1 shows the genetic study and mutation in each case of our series. Further details can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Genetic diagnosis was generally performed using genetic panels targeting congenital myopathies or exome sequencing. Some patients were studied with single gene sequencing due to high level of suspicion and/or lack of availability of the other techniques. Array CGH or MLPA were useful for detection of deletions.

The partial genotype–phenotype correlation described in other series3,14,15 can be observed in the cases shown in Table 1. Nonsense or truncation mutations and frameshift mutations cause the severe phenotype of XLMTM in male patients. Missense mutations show a less predictable phenotype in boys. Female phenotypes seem more related with other factors, such as skewed X inactivation, than with the type of mutation.

Supplementary Table 1 also shows the muscle biopsy findings from the patients in whom this information is available, such as predominance and hypotrophy of small type I fibres; centrally located nucleus; or scattered, atrophied round fibres.

Multidisciplinary management of XLMTMAfter diagnosis, the only currently available recommended therapeutic option or strategy to increase survival and improve quality of life is multidisciplinary management. Table 1 describes the interventions performed in our series of patients.

Respiratory managementAs shown in Table 1, all patients in our series presented signs of significant respiratory failure: many required and still require mechanical ventilation, and 13 have undergone tracheostomy. Respiratory complications, such as recurrent atelectasis and infections16 requiring hospitalisation and admission to the paediatric intensive care unit, were very frequent.

Management of gastrointestinal and nutritional needsMost patients required long-term tube feeding, so gastrostomy was performed.3 Although there are no specific guidelines for the management of gastrointestinal and nutritional needs in patients with XLMTM, a consensus document on congenital myopathies published in 2012 provides some general recommendations that serve as a valid guide for the authors, and the reported patients were managed accordingly,17 including close monitoring and administration of a supplemented diet adapted to the needs of each patient. Gastroenterologists and/or speech therapists are responsible for the management of sialorrhoea, and usually work together to help improve swallowing.

Rehabilitation therapyMost patients benefited from physical and/or occupational therapy, and rehabilitation physicians were involved in the periodic monitoring of patients with XLMTM.

Physical and occupational therapists focused on maintaining and/or improving muscle strength and joint mobility, and on maximising the patient's developmental function. Occupational therapists worked on activities of daily living and advised caregivers on the use of support devices and home adaptation. Speech therapists worked on both communication and swallowing, when required.

The most frequently identified osteoarticular complications, especially in non-ambulatory children, are scoliosis, limited joint movement, hip subluxation, osteoporosis, and increased risk of fractures. Conservative management involving physical therapy and stretching, which improves such typical features of XLMTM as pes equinus and knee flexion, was used to prevent these complications. As shown in case 8 (Supplementary Table 1), some complications, in this case scoliosis, may require surgical treatment.

Real-world challenges in comprehensive patient management. Unmet needsIn Table 1 we list a series of needs that were unmet in our patients, which can be summarised as follows:

- •

One of the main needs is to deepen our understanding of the neurocognitive profile of patients and to standardise and validate objective neurocognitive tools and scales. This will allow clinicians to correctly characterise these patients, despite their significant mobility limitations, to understand the course of the disease in each patient, and to administer personalised treatment to maximise treatment efficacy and patient well-being. Neuropsychological evaluations were limited due to lack of availability of experts and restricted to severely handicapped children.

- •

All patients should have rapid access to multidisciplinary management of their disease through referral and interconsultation channels.

- •

Resources for physical therapy are insufficient for the needs of some patients.

- •

Management of secretions could be difficult in patients with severe bulbar impairment.

- •

The use of patient communication aids should be encouraged. The use of electronic and augmentative communication systems such as tablets and picture books in specific cases facilitated patient communication and allowed them to develop cognitively at a normal level. All patients should have access to this professional support and to communication devices.

We present a large series of patients with XLMTM, a rare myopathy for which no curative therapy is currently available. These patients heavily depend on multidisciplinary management targeting the prevention and management of systemic complications, which may or may not be related to their neuromuscular involvement. This study focuses on non-neuromuscular complications, multidisciplinary management, and unmet needs. Due to the retrospective collection of data, this work presents certain limitations, but the large size of the series and the inclusion of non-neurologist experts in neuromuscular disorders are important strengths.

No curative therapy is currently available for XLMTM, but several therapies are under research. This makes it even more relevant to analyse our current experience with these patients, with two final aims: (1) keeping current patients in the most optimal state to receive any potential therapy in the future, and (2) our preparedness for future patient management in a clinical scenario in which at least one targeted therapy exists. Three therapies for XLMTM have been studied so far, and two potentially curative therapies are currently under investigation. The first is gene replacement therapy, which was shown to be effective in the treatment of XLMTM in 2008, and is currently at an advanced stage of development.18 After good efficacy results were achieved in various pre-clinical studies in vitro and in murine and canine models,19 a clinical trial of AT132 in humans (ASPIRO trial, NCT03199469) was approved. To date, 24 patients with XLMTM (aged <6 years, and treated with >12h of permanent ventilation at the start of treatment) have been enrolled in the AT132 trial. Efficacy data have so far been promising, although the trial is on hold pending identification of the causes of four adverse events of fatal liver failure.1,9,20,21 The other strategy under investigation is tamoxifen as a disease-modifying drug. Results from the preclinical phase have shown that daily administration of tamoxifen in a MTM1 knockout mouse model prolongs survival and improves different phenotypic aspects, such as muscle contractility,22,23 and could reduce expression of the DNM2 protein. A multinational clinical trial to test tamoxifen in patients with XLMTM aged 2–65 years (TAM4MTM trial, NCT04915846) was recently launched and has started recruiting.

Regarding the other treatment under investigation, the UNITE-CNM (NCT04033159) trial was cancelled due to safety and tolerability concerns.24,25

ConclusionsThe current management strategies for XLMTM include the interventions performed to treat each manifestation of the disease and comprehensive, multidisciplinary health and welfare care. Our review of the management of our patients and of the experience of other authors has prompted us to put forward a series of recommendations for the management of patients with XLMTM:

- •

Most cases, and all severe and moderate cases, are studied and diagnosed in the neonatal unit. However, patients with a mild phenotype may appear in the practices of various specialists, and diagnostic suspicion is essential for a rapid diagnosis and access to appropriate care. Therefore, it is important to raise awareness of this disease among medical professionals.

- •

The diagnosis of XLMTM must involve several specialists and must be studied with clinical, anatomical pathology, and genetic testing.

- •

Management must be multidisciplinary. To maximise treatment efficacy, management is highly personalised and involves different specialists: paediatricians, paediatric neurologists, paediatric pulmonologists, gastroenterologists, rehabilitation specialists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and ophthalmologists; patients can be treated at paediatric long-term care units and palliative care units. Patients should be monitored and treated at reference hospitals specialising in XLMTM or at a hospital with links to such reference centres.

- •

Early, proactive treatment can be the key to survival, especially with regard to respiratory management. This significantly increases the median survival of patients with respect to palliative management (19.2 years vs. 0.2 years, respectively).6 In most patients, respiratory muscle strength is severely impaired, requiring home mechanical ventilation; tracheostomy is needed for invasive home ventilation in most cases.2 Patients must be evaluated by a pulmonologist as soon as XLMTM is suspected.

- •

Other pillars of respiratory treatment are assisted coughing and removal of secretions, measures to prevent chronic aspiration syndrome (most ventilated patients require a feeding tube), and prevention and early treatment of respiratory infections. Caregivers should be trained in respiratory physiotherapy and assisted coughing techniques, and dietary strategies, pharmacological measures, and/or specific devices must be used to avoid saliva/food aspiration and gastroesophageal reflux. Training in hygiene measures and adherence to a schedule of vaccinations and/or prophylaxis against respiratory infections are important for preventing respiratory diseases. Population vaccination is recommended, with influenza vaccination from 6 months, 23-valent pneumococcal vaccination after 24 months, SARS-CoV-2 vaccination according to the general rule in our countries (adult patients with neuromuscular disorders and people living with and caring for paediatric patients are vaccinated as patients at risk, and paediatric patients follow the general vaccination strategy for the paediatric population), and the administration of specific anti–respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibodies during the epidemic season for the first 2 years of life. Rapid diagnosis and treatment of any respiratory infection is also important. Treatment involves assessing whether respiratory physiotherapy should be increased and whether assisted coughing and/or ventilatory support is required; considering early administration of antibiotics, given the greater risk of superinfection of retained secretions; and optimising the patient's hydration and nutritional status.

- •

It is particularly important to monitor patients for hepatobiliary involvement and cholestasis, due to the considerable incidence of hepatobiliary manifestations described recently in patients with XLMTM. It would be recommendable to conduct serial laboratory studies, with a complete liver profile, and annual abdominal ultrasound scans, as well as to be alert to the possible appearance of cholestatic symptomatology.

- •

Personalised nutritional support is highly important. The patient's diet and vitamin D levels must be closely monitored, and supplements must be given to correct any nutritional deficiencies. Gastrostomy should be performed if needed.

- •

All patients with XLMTM require physical and respiratory therapy, regardless of their phenotype. According to the available evidence,3,6,7,10 physical and occupational therapy help improve the quality of life of patients with XLMTM. In order to optimise their functional capacity as far as possible, all patients and caregivers should be advised on the use of support products. Depending on the patient's needs, clinicians may choose between conservative treatment and surgical interventions to prevent muscle and bone injuries and joint retractions.

- •

Assessment and treatment by a phoniatrist or speech therapist, depending on the patient's needs, can significantly improve these patients’ quality of life and cognitive, verbal, and non-verbal communication skills.

- •

The use of functional scales for monitoring disease progression is highly recommended. The most common paediatric scales used to assess motor milestones in XLMTM patients are the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND)26 and the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination (HINE)27 in children under 2 years old, while the Motor Function Measurement (MFM) scale is used in children aged over 2 years.18,19

- •

An ophthalmologist should be included in the multidisciplinary management of XLMTM due to the frequency of ocular alterations, such as ophthalmoparesis.

These considerations may be useful for clinicians treating patients with XLMTM. However, management remains palliative, and interdisciplinary teamwork is essential. A proactive approach will allow clinicians to intervene at an early stage and give caregivers and families the support and education they need. In the absence of a curative treatment, patients with XLMTM rely on clinicians’ best efforts. The pathophysiological mechanisms of the disease are not fully understood, and it is essential to continue researching the aetiology, presentation, and progression of the disease in order to, above all, develop a curative treatment that reduces the burden of the disease and increases patient survival.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors contributed to the conception of the study. All authors wrote the original draft. All authors made substantial contributions to the original draft and to the final manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for submission. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FundingTechnical support in writing of this manuscript from Medical Statistics Consulting was funded by Astellas.

Conflicts of interestAll authors who provided clinical cases declare that they have obtained informed consent from the parents if contact was possible.

TM in the last 3 years has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or participant in clinical studies from (in alphabetical order): Astellas, Avexis, Biogen, Novartis, and PTC.

JM in the last 3 years has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or participant in clinical studies from (in alphabetical order): Biogen, Roche, and PTC.

IPP in the last 3 years has received fees as a speaker or scientific advisor from (in alphabetical order): Astellas.

CMB in the last 3 years has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or participant in clinical studies from (in alphabetical order): Albireo, Alexion, and Astellas.

MCR in the last 3 years has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or participant in clinical studies from (in alphabetical order): Audentes Therapeutics, Biogen, Organon, Roche, and Vertex.

MM in the last 3 years has received fees as a speaker, scientific advisor, or participant in clinical studies from (in alphabetical order): Astellas, Roche, Novartis, and PTC.

The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data availabilityData sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during this study.

Medical writing support was provided under the guidance of the authors by Laura Vilorio Marqués, PhD, and Blanca Piedrafita, PhD, from Medical Statistics Consulting (MSC), Valencia, Spain, in accordance with Standard Operating Procedures from Astellas (SOP-709 and POL-168). Translation and proofreading of the manuscript were provided by a native English speaker at MSC. MSC technical support in writing this manuscript was funded by Astellas.