Focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) type II, or Taylor-type FCD, is considered a common cause of drug-resistant epilepsy, with specific characteristics. In many cases, these patients respond well to surgery.

Patients and methodsThe study included patients with FCD type II who had undergone an epilepsy protocol brain MRI scan, evaluated by an expert neuroradiologist, since 2012. We performed a retrospective observational analysis of diagnostic variables, clinical correlations with presurgical evaluation studies, indications for surgery, and response.

ResultsThe sample included 50 patients (50% women, with a mean [SD] age at seizure onset of 13 [9.7] years). All patients were diagnosed with focal-onset seizures. Some 12.5% of patients also presented functional non-epileptic seizures. Seizure frequency was daily or weekly in 70% of cases, and drug-resistant epilepsy was diagnosed in 72%. FCD was most frequently located in the frontal lobes (68%). In 87% of cases, a correlation was observed between the FCD region and hypometabolism on FDG-PET. Twenty-six patients underwent surgical treatment, and two other patients are currently awaiting surgery. In the surgery group, 79% of patients were seizure-free at 2 years after the procedure.

ConclusionsFCD type II is not always associated with drug-resistant epilepsy. Diagnosis does not rule out the presence of functional seizures. Because of the need for neurophysiological and protocolised neuroimaging tests, these patients should be managed at expert units within referral centres. Surgery achieves clinical improvement in most cases, with complete seizure freedom in approximately 80% of our series.

Las displasias corticales focales (DCF) tipo II o tipo Taylor se consideran causas frecuentes de epilepsia farmacorresistente, con algunas características propias. En muchos casos muestran buena respuesta al abordaje quirúrgico.

Métodos y pacientesSe incluyeron pacientes con DCF tipo II en RM cerebral con protocolo de epilepsia evaluados por un neurorradiólogo experto desde el año 2012. Se realizó un análisis observacional retrospectivo de las variables diagnósticas, la correlación clínica con los estudios de evaluación prequirúrgica, la indicación quirúrgica y la eventual respuesta.

ResultadosCincuenta pacientes (50% mujeres con 13±9,7 años de edad en la primera crisis). Todos los pacientes fueron diagnosticados de epilepsia de inicio focal. Un 12,5% de ellos presentaban también trastornos paroxísticos no epilépticos (TPNE). La frecuencia de las crisis fue diaria o semanal en el 70% de los casos y se diagnosticó epilepsia farmacorresistente en el 72%. Las DCF se localizaron con mayor frecuencia en los lóbulos frontales (68%). En el 87% de los casos, se observó una correlación entre la DFC con hipometabolismo en la FDG-PET. Veintiséis pacientes fueron operados, y otros 2 están actualmente en lista de espera. Dentro del grupo quirúrgico, la ausencia de crisis desde la intervención hasta los 2 años se alcanzó en el 79%.

ConclusionesLas DCF tipo II no siempre se asocian a epilepsia farmacorresistente. Tampoco excluyen la presencia de TPNE. Debido a la necesidad de pruebas neurofisiológicas y de neuroimagen protocolizadas, deben estudiarse en unidades de referencia y especializadas. El abordaje quirúrgico consigue una mejoría clínica en la mayoría de los casos, con ausencia total de crisis en aproximadamente el 80% de nuestra serie.

Since Taylor et al.1 published the first descriptions of focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) in a series of 10 patients in 1971, there has been growing interest in this entity. On the one hand, its aetiological diagnosis is essential for the management of epilepsy, especially in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE), which underscores the important role it should play in the differential diagnosis of focal epilepsies. On the other hand, advances in neuroimaging have made it possible to identify and more accurately diagnose those dysplasias that are more difficult to visualise.

The International League Against Epilepsy's (ILAE) 2022 update of the 2011 Blümcke classification highlights the large body of new evidence obtained in recent years in relation to FCD, particularly regarding its molecular/genetic characterisation involving the mTOR pathway and the definition and validation of electro-clinical-imaging phenotypes.2 FCD type II is probably the most thoroughly studied.

Most studies of FCD are series of patients evaluated for epilepsy surgery; therefore, the incidence of FCD lesions in patients without DRE is unknown. In addition, most of the current evidence stems from either heterogeneous populations or exclusively paediatric populations; this is also the case with the most significant series published to date.3 We present a series of adult patients with well-controlled epilepsy and DRE and findings of FCD on 3T MRI with an epilepsy protocol from a tertiary hospital, a national reference centre for preoperative evaluation of patients with DRE.

Material, patients, and methodsThis is a single-centre, observational, descriptive retrospective study. We reviewed the patients’ clinical histories, including seizure semiology, presence of DRE according to the latest ILAE definition, neuroimaging findings, electroencephalography recordings, presence of non-epileptic seizures, and surgery in all patients under follow-up at our epilepsy unit. Since 2012, when 3T MRI scanners began to be used in clinical practice at our hospital, we recruited 50 patients who met the following inclusion criteria:

- -

Age 15 years or older (age of transition from paediatric to adult neurology at our centre).

- -

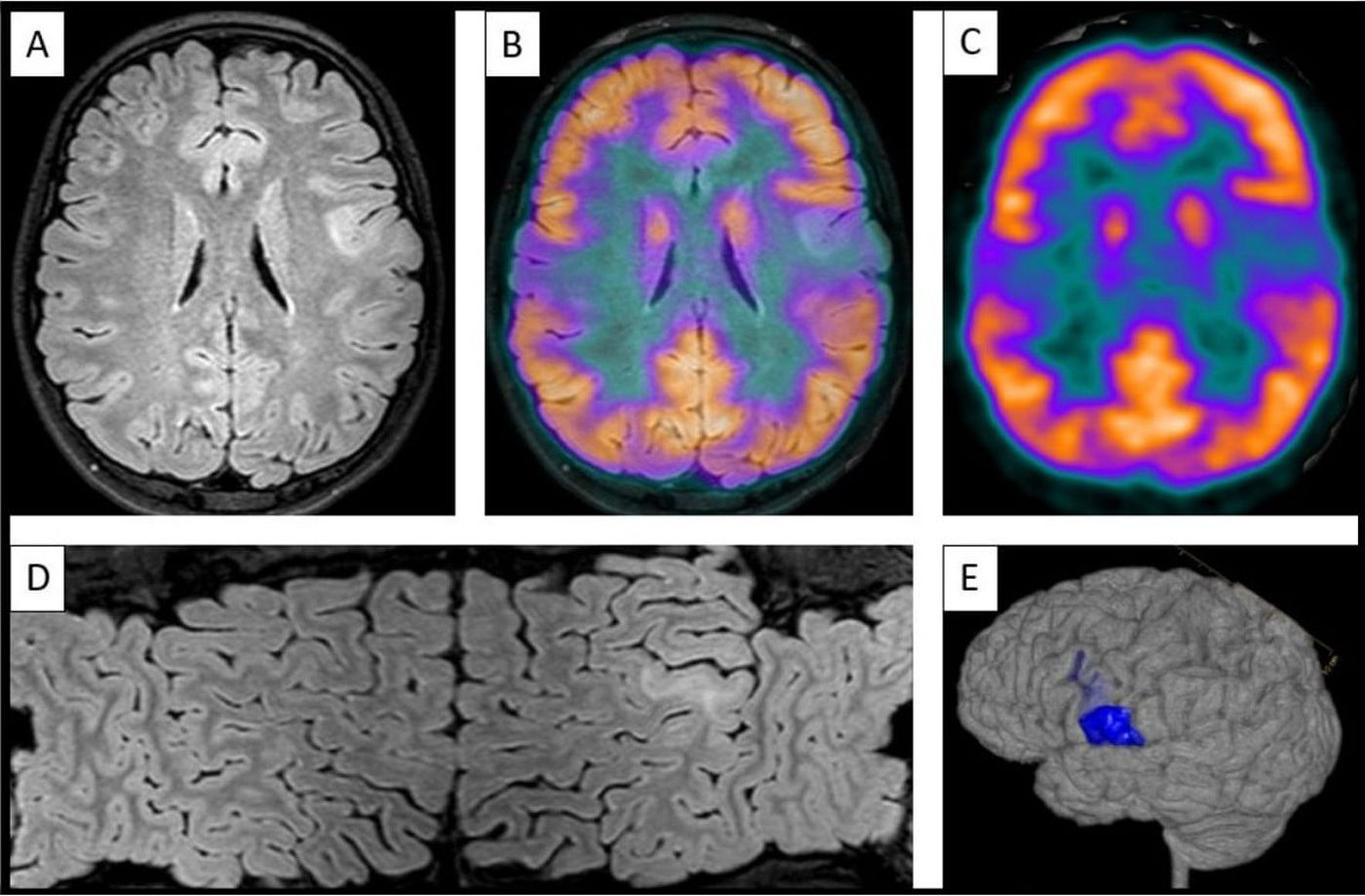

Undergoing 3T MRI with an epilepsy protocol, including specific sequences (3D T1-weighted TFE, 3D T2-weighted FLAIR, 3D T2-weighted TFE, axial SWIp, axial TSE-DWI), as well as brain MRI-PET image fusion when available (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.Images showing left opercular bottom of sulcus focal cortical dysplasia type II. (A) Axial FLAIR sequence on 3T MRI. (B) Fusion of images (A) and (C). (C) Axial FDG-PET sequence at the location of FCD. (D) Mercator reconstruction, based on FLAIR sequences. (E) 3D MRI volumetric reconstruction.

- -

Imaging evidence of FCD type II on 3T MRI with an epilepsy protocol, evaluated by the same neuroradiologist with expertise in epilepsy neuroimaging.

All patients underwent a 3T MRI study with an epilepsy protocol, and were evaluated by a neuroradiologist specialised in epilepsy during follow-up at our adult neurology epilepsy clinic (attending patients ≥15 years old). Patients who developed epilepsy in childhood or early adolescence were also included; in 32 patients, symptom onset occurred before the age of 15 years.

Our patients were evaluated and followed up by epileptologists at our unit, who established seizure type, semiology, lateralisation, relationship between epilepsy and FCD, and correlation with complementary test results (≥24h EEG monitoring in most patients, and brain FDG-PET, when indicated).

Prolonged video-EEG monitoring was performed 24h per day over several days until all types of episodes reported by the patients were recorded. The study was performed in all patients with DRE, whereas non-drug-resistant epilepsy was studied either with 24-h EEG or, in isolated cases, repeated EEG evaluations.

The brain MRI sequences mentioned above were acquired with a 3T MRI scanner. Regarding functional neuroimaging techniques, FDG-PET was conducted using a single dose of 189MBq. Brain metabolism was studied with 3D-acquisition mode and attenuation correction using low-dose brain CT. Image fusion with brain MRI was also performed.

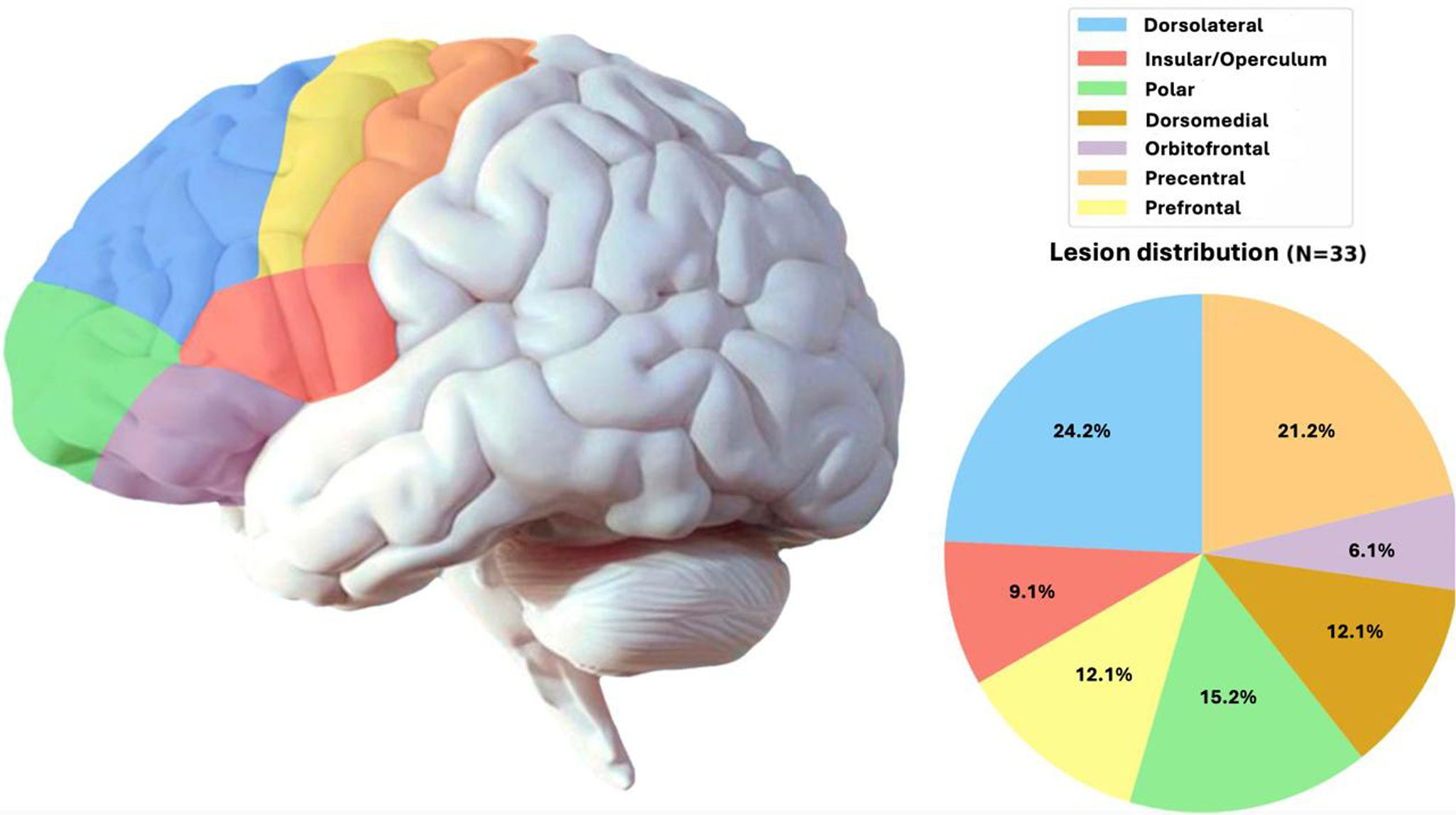

We also studied the neuroanatomical localisation of FCD according to the classical division of the cortex into the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. Within the frontal lobe, regions were subdivided on the basis of established neuroanatomical criteria (Fig. 2).

Surgical samples were analysed by our hospital's pathology department. When needed, immunohistochemical techniques were applied. Cases were classified into types I, II, and III. Subsequently, when technically feasible, type II cases were further classified as either IIa or IIb.

For the neuropathological study, whole tissue samples from the surgical specimen were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-μm sections with primary antibodies against Vimentin-V9 (1:200, Dako #IR630), neurofilament protein-2F11 (Dako #GA607), polyclonal glial fibrillary acidic protein (Dako #Z0334), CD34-QBEnd-10 (Dako #M7165), and NeuN-1B7 (1:100, Gennova #AP10823). Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

The dysplastic region in the fixed surgical specimen shows poor differentiation between grey and white matter. For the microscopy study, all tissue samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded, and a 4-μm section was used for H&E staining and immunohistochemistry. While the dysplastic pattern is recognisable in H&E, dysmorphic and hypertrophic neural cells show marked neurofilament protein labelling, revealing their abnormal morphology, alignment, and laminar position, as well as the abnormal cortical networks of axons and thick dendrites. Balloon cells are labelled with vimentin, GFAP, and NeuN.

ResultsFifty patients were included in our study, 50% of whom were women. Mean age (SD) was 44 (13.7) years, with a median age (Q1–Q3) of 47 (34.7–54) years. Mean age at epilepsy onset was 12.9 (9.7) years (median: 10 [7–17]). All patients were over the age of 18 years.

These 50 patients with findings of FCD type II represent 4% of all patients undergoing 3T MRI scans with an epilepsy protocol at our unit since 2012 (n=1207).

All patients presented focal-onset seizures, in most cases with impaired level of consciousness (n=39; 78%). In 26 cases (52%), focal-onset seizures progressed to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures at least on one occasion; 22 of these (85%) presented focal onset and altered level of consciousness.

Clinical history data and seizure semiology revealed hemispheric lateralisation in 21 patients (42%), with most patients presenting seizures with motor onset in one hemibody or in a single limb. In 40 patients (80%), this clinical analysis suggested involvement of a specific lobe of the brain; the frontal lobe was identified as the epileptogenic focus in 29 (72.5%) of these patients (Fig. 2).

Regarding the response to pharmacological treatment, our sample included 36 (72%) patients with DRE, who continued to present seizures despite treatment with 2 well-indicated antiseizure medications (ASM) at adequate doses.4 Fourteen patients (28%) maintained good seizure control with 2 ASMs or fewer. In the drug-resistant group, 3 patients presented a significant decrease in seizure frequency with 3 or 4 ASMs, in most cases decreasing from daily/weekly to monthly/sporadic seizures. Twenty-one (42%) patients had at least one seizure per day, 14 (28%) presented a weekly frequency, 4 (8%) had approximately one seizure per month, and 11 (22%) had sporadic seizures (less than one seizure per month).

Video EEG monitoring was performed in 40 patients (80%), including all patients with DRE. Eight of the remaining patients (80%) underwent prolonged monitoring with Holter-EEG. Regarding video EEG findings, seizure localisation correlated with 3T MRI lesions in 23 patients (57.5%). In the remaining patients, results only allowed us to predict either seizure lateralisation or the lobe where the lesion was located.

In 5 patients (12.5%), video EEG revealed non-epileptic paroxysmal events compatible with functional seizures, coexisting with epileptic seizures.5

Regarding neuroimaging and lesion location, the lesion was located in the frontal lobe in 34 patients (68%), in the temporal lobe in 10 (20%), in the parietal lobe in 4 (8%), and in the occipital lobe in 2 patients (4%). Fig. 2 further explores lesion location within the frontal lobe in our sample.

A total of 38 patients (76%) underwent FDG-PET, which revealed hypometabolism in 33 of them (87%).

Of the entire sample, 29 patients (58%) had an indication for surgery. Of the remaining patients, 14 had non-refractory seizures, 5 refused surgical treatment, and 2 were undergoing preoperative evaluation at the time of inclusion.

The most common surgical procedure was lesionectomy, performed on 24 patients (92%). One patient underwent lobectomy due to presence of an extensive lesion, and another patient underwent thermocoagulation since the epileptic focus was located in an eloquent area.

Regarding postsurgical clinical outcomes, most patients achieved seizure control. In the group of patients who were followed up for at least 2 years after surgery (n=24), 19 (79%) presented no seizures or epileptic aura (Engel Outcome Scale, class IA); 2 (8%) were classified as Engel class II, and the remaining 3 (13%) were classified as Engel class III, but underwent a reintervention, with expansion of the resection margins with regard to the initial lesionectomy, achieving seizure freedom at 2 years of follow-up. Therefore, the reoperation rate in our subgroup of patients undergoing surgery was 12.5% (3 patients, including 2 with FCD type IIa).

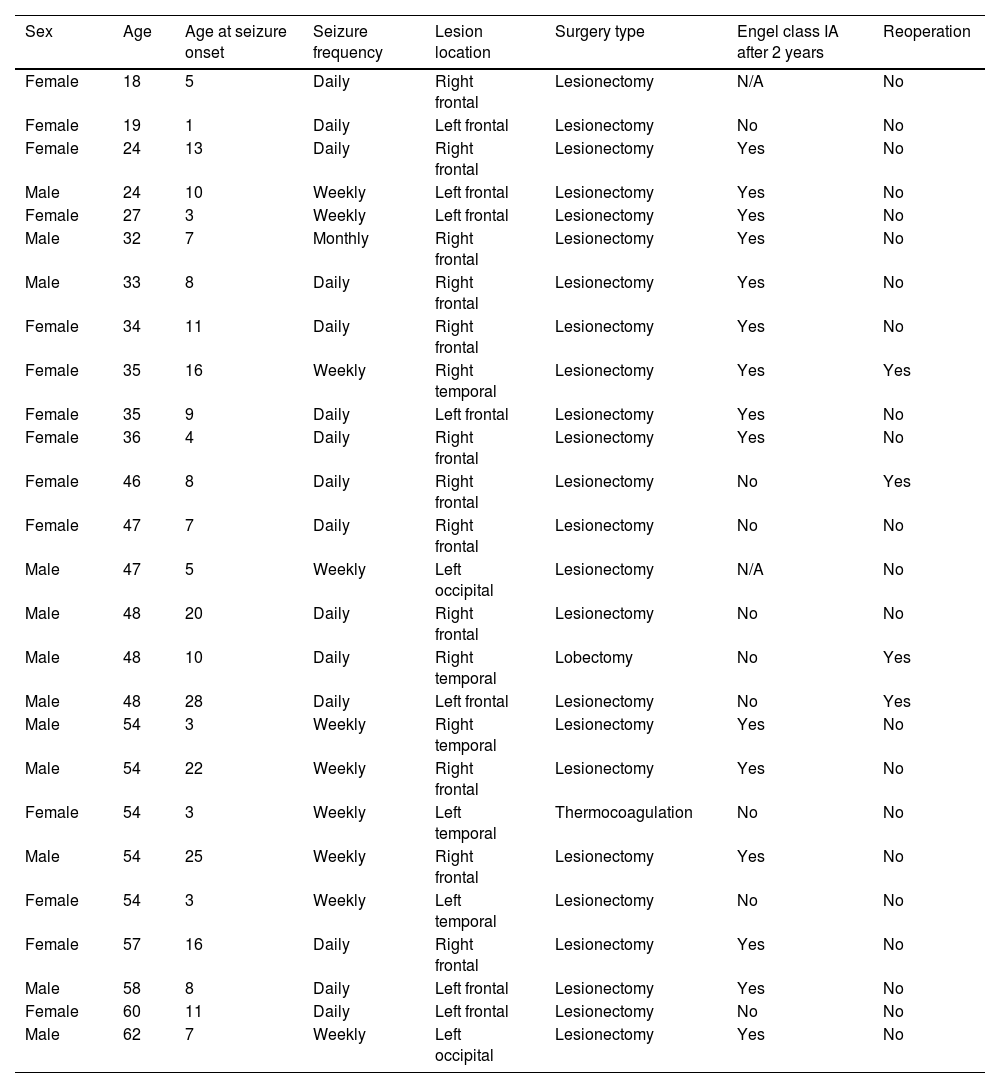

The characteristics of the 26 patients who had undergone surgery at the time of inclusion (90% of those with an indication for surgery) are summarised in Table 1.

Summary of the most significant variables in the subsample of patients undergoing epilepsy surgery.

| Sex | Age | Age at seizure onset | Seizure frequency | Lesion location | Surgery type | Engel class IA after 2 years | Reoperation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 18 | 5 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | N/A | No |

| Female | 19 | 1 | Daily | Left frontal | Lesionectomy | No | No |

| Female | 24 | 13 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Male | 24 | 10 | Weekly | Left frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 27 | 3 | Weekly | Left frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Male | 32 | 7 | Monthly | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Male | 33 | 8 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 34 | 11 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 35 | 16 | Weekly | Right temporal | Lesionectomy | Yes | Yes |

| Female | 35 | 9 | Daily | Left frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 36 | 4 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 46 | 8 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | No | Yes |

| Female | 47 | 7 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | No | No |

| Male | 47 | 5 | Weekly | Left occipital | Lesionectomy | N/A | No |

| Male | 48 | 20 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | No | No |

| Male | 48 | 10 | Daily | Right temporal | Lobectomy | No | Yes |

| Male | 48 | 28 | Daily | Left frontal | Lesionectomy | No | Yes |

| Male | 54 | 3 | Weekly | Right temporal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Male | 54 | 22 | Weekly | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 54 | 3 | Weekly | Left temporal | Thermocoagulation | No | No |

| Male | 54 | 25 | Weekly | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 54 | 3 | Weekly | Left temporal | Lesionectomy | No | No |

| Female | 57 | 16 | Daily | Right frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Male | 58 | 8 | Daily | Left frontal | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

| Female | 60 | 11 | Daily | Left frontal | Lesionectomy | No | No |

| Male | 62 | 7 | Weekly | Left occipital | Lesionectomy | Yes | No |

Two additional patients underwent surgery less than a year ago, and have presented no seizure recurrence to date. One of them presented a notable reduction in seizure frequency (>50%), but has not achieved seizure freedom.

Subsequent assessment of the sample using pathology techniques revealed 8 cases of FCD type IIa and 14 cases of FCD type IIb. Furthermore, in one case lesionectomy was not performed, but rather thermocoagulation.

Concerning the possibility of neuropathologically “overlooked” cases of FCD type IIb (when only the cortical part but not the white matter part of the lesion has been removed), we retrospectively reviewed the cases of FCD type IIa, looking for the presence of the transmantle sign in the MRI study performed prior to surgery and analysing whether that region had been resected in the follow-up MRI study. Of 8 cases, only one could be included in the category of FCD type IIb on MRI, and was classified neuropathologically as FCD with dysmorphic neurons, compatible with FCD type IIb.

DiscussionWe present a series of adult patients with epilepsy and neuroimaging findings of FCD type II, with the aim of describing the characteristics of patients in whom this lesion was the cause of their epilepsy.

Published series usually focus on the description of cases of DRE with FCD. In our study, we included all patients with epilepsy and MRI evidence of FCD, which allowed us to determine the proportion of cases of FCD that do not cause DRE (approximately 30% of our sample). Our results provide a more accurate prediction of the prognosis in patients with these findings, and also reinforce the need for protocolised neuroimaging studies in patients with epilepsy, in order to better predict the risks of ASM withdrawal in patients with negative structural imaging results (non-targeted MRI). Regarding non-epileptic paroxysmal disorders, 13% of our patients had at least one functional seizure during the course of their disease5; this rate is lower than that estimated for epilepsy patients in general,6 which underscores the need for video EEG monitoring in patients with DRE.

In relation to seizure frequency in the entire sample, our results reveal that FCD frequently causes a high number of seizures, with 70% of our patients presenting daily or weekly seizures. This could also be connected to their preferential localisation in the frontal lobe.7

Several other studies have found FCD to more frequently affect the frontal lobes (50%–65%).8–10 Our results are in line with these data; in our sample, the temporal lobe was the second most frequent location, contrary to previous evidence.11 As far as we are aware, no study has addressed the most commonly affected frontal lobe subregions, which in our patients were the dorsolateral and precentral areas.

FDG-PET showed a strong correlation with other complementary tests, with 87% of studies displaying hypometabolic areas where FCD was observed on 3T MRI. Other studies have described similar results, with correlation values between 70% and 90%.12,13

In general, the intrinsic epileptogenicity of FCD type II lesions is restricted to the dysplastic sulcus, and justifies resection or ablation confined to the MRI-visible lesion as the first-line surgical approach.14

Almost 80% of the patients undergoing surgery achieved seizure freedom, including resolution of auras, during at least 2 years of follow-up; this rate is similar to that reported in previous series.11,15–17 However, most of these included paediatric patients, and given that early intervention has been shown to have a significant impact on prognosis,15 the rate of seizure freedom in our series provides useful information for adult populations (our youngest patient was 18 years old when the MRI study was performed). It is worth mentioning that the patients undergoing a second surgery achieved Engel class IA; thus, the overall percentage of seizure freedom would increase to 91%. It is noteworthy that 66% of these reoperated lesions (2 of the 3 patients) presented temporal FCD, which is reported to have a good prognosis (in paediatric patients, and compared to parietal and occipital lesions).9

The strengths of this work lie in the thorough clinical and diagnostic characterisation of a large patient sample, reporting surgical outcomes in all cases. Furthermore, given that most publications include paediatric patients, we believe that our study provides useful data for the characterisation of FCD in adult populations. Another noteworthy finding is the observation that 30% of patients with FCD did not present DRE. The limitations of our study include its retrospective nature, with the potential for bias arising from the use of medical record data. Another potential source of bias is the fact that all patients were recruited from a single centre, limiting the size of the sample and the conclusions of subgroup analyses.

ConclusionsFCD type II is not always associated with refractory epilepsy, as was the case with 28% of our patients. Likewise, presence of lesional epilepsy does not rule out the possibility of concomitant non-epileptic paroxysmal disorders (observed in roughly 13% of our series). The most common cerebral localisation of FCD is the frontal lobe, particularly the precentral and dorsolateral regions. In our series, localization in the temporal lobe was associated with poorer prognosis after surgery. Surgical treatment has been shown to be very effective, achieving improvements in quality of life in most patients, as well as complete seizure freedom at 2 years in 78% of our adult case series.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAMMP, JGS, and JPD collected the variables and processed the data. AMMP, JGS, and XRO participated in the drafting of the manuscript. AMMP and XRO elaborated the design and conceptualisation of the study. XRO, FJLG, and AJF evaluated patients and issued diagnoses and indications for treatment. CFD and APG performed epilepsy surgery. KVO performed the anatomopathological analysis of surgical material. JCH processed and evaluated FDG-PET images. EPS evaluated the EEG recordings. JACM evaluated and reported 3T MRI images. All authors made substantial contributions to the conception of the study; or the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Compliance with ethical standardsThis study design followed a retrospective, and non-interventionist approach.

It was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki on Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and the Oviedo Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine.

Patients’ clinical data were collected by the investigator in a study-specific data collection notebook (DCN). Each DCN was coded/pseudonymised, protecting patient anonymity. Only the research team and the healthcare authorities, who have a duty of confidentiality, have access to all the data collected for the study.

All patients gave consent to participate in the study, and granted access to their clinical records. All patients consented to the publication of their data and are aware that they may access the results of this study upon request.

FundingThis work has not been funded, either in full or in part.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Special thanks to Santiago Pendón Minguillón, who collaborated in the creation of the figures and tables included in the manuscript.