Provide consensus recommendations for the optimal management of fixed-dose combination therapies (FCT) in patients with cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) in primary care (PC).

Material and methodsA modified Delphi technique was used. A scientific committee wrote 80 statements addressing controversial issues regarding adherence and the use of FCT in patients with CVRF. A panel of 52 PC specialists, experts in CVRF management and adherence evaluated the questionnaire in two rounds. The work was promoted by the Network of Experts in Adherence in Primary Care (REAAP).

ResultsAgreement was reached on 66 of the 80 issues (82.5%). The panellists considered that the adherence of patients with CVRF treated in PC was inadequate, which could have clinical implications. The use of FCT might increase adherence compared to separate treatments. FCT usage promotion in PC was considered necessary, especially in polymedicated patients. Measures such as establishing specific protocols or improving the training of professionals in the FTC use are necessary. The FTC use was recommended as a reduction in long-term cardiovascular events in hypertension was observed, together with changes of the concept of high-intensity statins to high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy in dyslipidemia, or considering the use of FCT if the option was available in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

ConclusionsThe expert consensus recommendations from this work may facilitate the use of FCT in patients with CVRF in PC.

Dar recomendaciones consensuadas sobre el manejo óptimo de las terapias combinadas a dosis fijas (TCDF) en los pacientes con factores de riesgo cardiovascular (FRCV) en atención primaria (AP).

Material y métodosSe utilizó una técnica Delphi modificada. Un comité científico redactó 80 aseveraciones que abordaban cuestiones controvertidas sobre adherencia y uso de TCDF en los pacientes con FRCV. Un panel de 52 especialistas en AP expertos en el manejo de FRCV y adherencia evaluó el cuestionario en dos rondas. El trabajo fue promovido por la Red de Expertos en Adherencia de Atención Primaria (REAAP).

ResultadosSe llegó a un acuerdo en 66 de las 80 cuestiones (82,5%). Los panelistas consideraron que la adherencia de los pacientes con FRCV atendidos en AP es inadecuada, lo que tiene implicaciones clínicas. El uso de TCDF podría aumentar la adherencia en comparación con los tratamientos por separado. Se consideró necesario fomentar el uso de TCDF en AP, especialmente en pacientes polimedicados. Son necesarias medidas como el establecimiento de protocolos específicos o mejorar la formación de los profesionales en su uso. Se recomendó el uso de TCDF que hayan demostrado reducción de eventos CV a largo plazo en la hipertensión arterial (HTA), cambiar el concepto de estatinas de alta intensidad por el de terapia hipolipemiante de alta intensidad en las dislipemias, o considerar el uso de TCDF si estuviera disponible la combinación requerida en la diabetes mellitus (DM2).

ConclusionesLas recomendaciones consensuadas de expertos de este trabajo pueden facilitar el uso de TCDF en los pacientes con FRCV en AP.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the main cause of mortality in Spain. They were responsible for 121,342 deaths in 2022, 26.1% of total deaths in Spain overall, and 29.5% of the total number in people above 80 years old.1 CVD are largely associated with modifiable risk factors, such as arterial hypertension (HTN), dyslipidaemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2).2 These CVRF are among the so-called major and independent risk factors, they are closely related to CVD and are very frequent in the general population.2

We currently have safe and efficacious treatments to control CVRF. Despite this, medication adherence is around 50% for the primary prevention of atherosclerotic CVD and 66% for secondary prevention.3 The lack of adherence to the treatment regimen involves multiple consequences, both clinical and economic, derived from the increasing mortality or morbidity observed in non-compliant patients, particularly those with high CVR or metabolic syndrome.2 Among the strategies that are used to increase the adherence of patients with chronic diseases, the simplification of treatment is particularly noteworthy, including the use of fixed-dose combination therapies (FCT) in a single pill.4 The evidence suggests that patients treated with FCT may have better adherence and greater satisfaction compared to those treated with treatments separately, in the management of HTN,5 dyslipidaemia6 or DM2.7,8 Although the clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of FCT,3,9–11 there are numerous uncertainties regarding the optimisation of their management. For example, there are no clear recommendations as to what the optimal combination therapy is for each patient profile, what the best time is to introduce it into the evolution of the disease, in what population it might be inadvisable or how to perform treatment escalation.

It is important to know the opinion of family and community specialists who are experts in the management of CVRF and in adherence. This consensus may be used to come up with recommendations that may be useful to all PC doctors when prescribing FCT and translate into better control of patients’ CVRF and therefore reduce morbidity and mortality. Consequently, a project falling within the work lines of the Red de Expertos en Adherencia de Atención Primaria (REAAP), a group of experts in adherence and CVRF who address the issue of adherence in the management of cardiovascular risk patients in PC with a practical approach was produced.12

The objective of this project was to reach a consensus and issue recommendations on questions that are controversial or have not been fully clarified in the literature regarding the optimal management of FCT in patients with CVRF in PC.

MethodsAn expert agreement was reached using a modified Delphi method following the RAND/UCLA recommendations.13,14 The first step, at the proposal of the REAAP, was to assemble a scientific committee of experts in adherence and the management of CVRF involving ten members of the SEMERGEN GIS Group (Medication Management, Clinical Inertia and Patient Safety Working Group).

Following a bibliographic search and a qualitative review of the literature, and also based on the scientific committee's clinical experience, 80 items or statements were drafted that reflect controversial or not fully-clarified situations in the literature regarding FCT HTN, dyslipidaemia and DM2 in PC. Subsequently, a panel of experts in the management of CVRF and adherence was selected. The panellists were experts in family medicine and belonged to working groups of the Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria (SEMERGEN) related to the management of CVRF. Their mission was to evaluate the items drafted by the scientific committee. The panellists did not receive any remuneration for their participation in the consensus.

The questionnaire was sent to the panellists to be answered online in two rounds. The items were scored on an ordinal 9-point scale (1=totally disagree; 9=totally agree). Their answers were grouped into three regions (1–3=disagree; 4–6=neither agree nor disagree; 7–9=agree). The panellists had the opportunity to voice their opinion about the statements in the first round. Between rounds, the panellists were informed of the detailed distribution of the answers from the first analysis. The panellists who did not respond to the first round were excluded from the next analysis.

For an item to be regarded as having a consensus agreement, the median of the answers had to be included in the 7–9 region. Consensus disagreement was defined as when the median was included in the 1–3 region. Similarly, for an item to be regarded as having consensus, the number of panellists voting outside the 1–3 or 7–9 region had to be <1/3 of the total and the interquartile range had to be <4. The items on which no consensus was reached in the first round were reassessed in the second round. The results of the consensus were used to draft recommendations on the management of CVRF with FCT (Tables 1–4).

General and specific recommendations in the office to improve adherence to combination therapy.

| General recommendations |

| • Give healthcare professionals enough time to be able to do their job properly. |

| • Create or increase awareness among professionals about treatment adherence in order to achieve the control objectives. |

| • The use of fixed-dose combination therapies (in a single pill) may increase treatment adherence in patients with CVRF in PC compared to the treatments given separately. The use of fixed-dose combination therapies in PC must be encouraged, particularly in multi-medicated patients, to improve treatment adherence. |

| • Specific care protocols need to be established for the management of CVRF with fixed-dose combination therapies in PC. |

| • Training for PC doctors in the use of fixed-dose therapies needs to be improved. |

| • All interventions that consist of providing information about the disease verbally or in writing, through audiovisual media, by telephone, email, in person or in groups or by means of home visits, may help to improve treatment adherence. |

| • Telephone appointments and other technologies linked to telemedicine can help to improve therapeutic adherence. However, these tools must be just one of the other complements on PC personnel's agendas and should never completely replace the face-to-face appointment. |

| • The role of the nursing staff in the adherence of patients with CVRF in PC should be encouraged. |

| • Adherence-focused patient education programmes must be implemented. |

| • “Active patient-” or “Expert patient”-type programmes must be implemented to promote adherence in PC through workshops given by people with chronic conditions. |

| • Community chemists’ must be involved in the care and follow-up of chronic and multiple-pathology patients. |

| • Dissemination campaigns should be implemented in the media addressing the importance of treatment adherence and the value of medication. |

| • It is advisable to create and disseminate materials with supporting messages on adherence in the form of leaflets made available in waiting rooms, in doctors’ and nurses’ offices and in pharmacy offices. |

| • The different autonomous (regional) healthcare services must have a specific programme targeting the improvement of treatment adherence, explaining the different activities to be performed in each healthcare tier. |

| • The administrations must develop training programmes in therapeutic adherence for all PC healthcare professionals, ensuring that patients always receive the same message. |

| Specific recommendations in the office in primary care |

| • Investigate treatment adherence in any poorly-controlled patient. |

| • Adapt the treatment to the patient's characteristics (age, multiple medications, lifestyle, primary prevention, secondary prevention, etc.) to optimise adherence. |

| • Establish scheduled appointments lasting at least 10 minutes in patients with CVRF at which the patient can voice all their questions, fears, beliefs or objections. |

| • Provide medical instructions in writing. |

| • Reach an agreement with the patient about the therapeutic regimen. |

| • Simplify drug regimens, either by changing the dosage regimen or the formulation or by prescribing fixed-dose combination drugs. |

| • Facilitate continuity of care. |

| • Use validated adherence control tools systematically. |

| • Use the new technologies to issue reminders or warnings about taking medication. |

| • Hold a motivational interview/behavioural intervention. |

| • Recommend the use of pillboxes or PDDS that are prepared in chemists. |

PC: primary care; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; PDDS: personalised drug delivery systems.

Recommendations for improving adherence to combined therapy in patients with hypertension.

| General recommendations |

| • The choice of the first drug or drugs to be used will be personalised and will be based on the profile of special indications, precautions for use and contraindications of the different antihypertensive drug groups. |

| • In the treatment of patients with HTN in PC, it is advisable to: |

| ∘ Consider the use of initial fixed-dose combination therapies in most patients to achieve control within a maximum term of 3 months. |

| ∘ Use fixed-dose combination therapies that have been proven to reduce long-term cardiovascular events. |

| ∘ Use fixed-dose combination therapies that facilitate treatment escalation and make it possible to increase the dose of the drugs included in the combination without switching medication. |

| ∘ Always use initial fixed-dose combination therapies in patients with HTN and high cardiovascular risk. |

| ∘ Consider monotherapy for patients with low-risk stage 1 HTN and with baseline BP levels close to the target. |

| ∘ Consider monotherapy for frail or elderly patients. |

| ∘ Use fixed-dose combination therapies that do not affect other CVRF. |

| ∘ Use fixed-dose combination therapies with two drugs that are included in triple-drug combinations to facilitate escalation if necessary. |

| ∘ Always consider the use of triple-drug fixed-dose combination therapies if the objectives are not reached with the two-drug fixed-dose combination therapy. |

| Recommendations according to comorbidities |

| • In hypertensive patients without other comorbidities who initiate a fixed-dose combination therapy, generally speaking the most recommendable combination is: |

| ∘ ACE inhibitor+diuretic. |

| ∘ ARB+diuretic. |

| ∘ Any combination of ACE inhibitor+ARB+calcium channel blocker or diuretic. |

| • In HTN patients in PC, as a rule the first-line diuretics of choice are the thiazides or thiazide-type diuretics such as chlorthalidone or indapamide. |

| • In patients with HTN associated with ischaemic heart disease, the initial treatment of choice is: |

| ∘ Fixed-dose dual combination therapy with ACE inhibitors or ARB+calcium channel blocker or diuretic. |

| ∘ Combination therapy with ACE inhibitor or ARB+beta blocker. |

| • In patients with HTN associated with chronic kidney disease, the initial treatment of choice is fixed-dose dual combination therapy with ACE inhibitor or ARB+calcium channel blocker or diuretic. |

| • In patients with HTN associated with heart failure, the initial treatment of choice is fixed-dose triple combination therapy with ACE inhibitor or ARB+diuretic (or loop diuretic)+beta blocker. |

| • In patients with HTN associated with heart failure, the initial treatment of choice is fixed-dose triple combination therapy with ACE inhibitor or ARB+diuretic (or loop diuretic)+beta blocker or quadruple therapy with sacubitril/valsartan+anti-aldosterone agents+beta blocker+SGLT2i. |

PC: primary care; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; IQR: interquartile range; ACE inhibitor: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; HTN: hypertension; SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors.

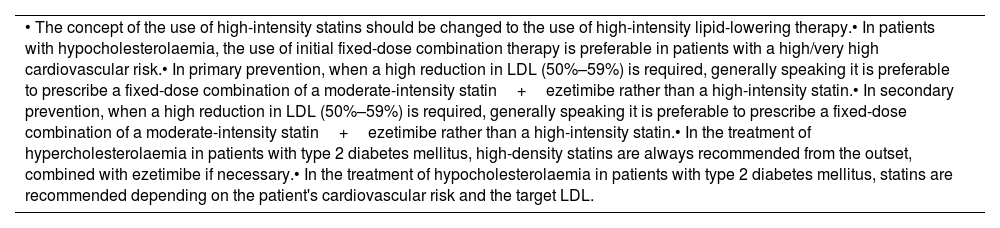

Recommendations for improving adherence to combined therapy in patients with dyslipidaemia.

| • The concept of the use of high-intensity statins should be changed to the use of high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy.• In patients with hypocholesterolaemia, the use of initial fixed-dose combination therapy is preferable in patients with a high/very high cardiovascular risk.• In primary prevention, when a high reduction in LDL (50%–59%) is required, generally speaking it is preferable to prescribe a fixed-dose combination of a moderate-intensity statin+ezetimibe rather than a high-intensity statin.• In secondary prevention, when a high reduction in LDL (50%–59%) is required, generally speaking it is preferable to prescribe a fixed-dose combination of a moderate-intensity statin+ezetimibe rather than a high-intensity statin.• In the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, high-density statins are always recommended from the outset, combined with ezetimibe if necessary.• In the treatment of hypocholesterolaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, statins are recommended depending on the patient's cardiovascular risk and the target LDL. |

LDL: low-density lipoproteins.

Recommendations for increasing adherence to combined therapy in patients with diabetes mellitus.

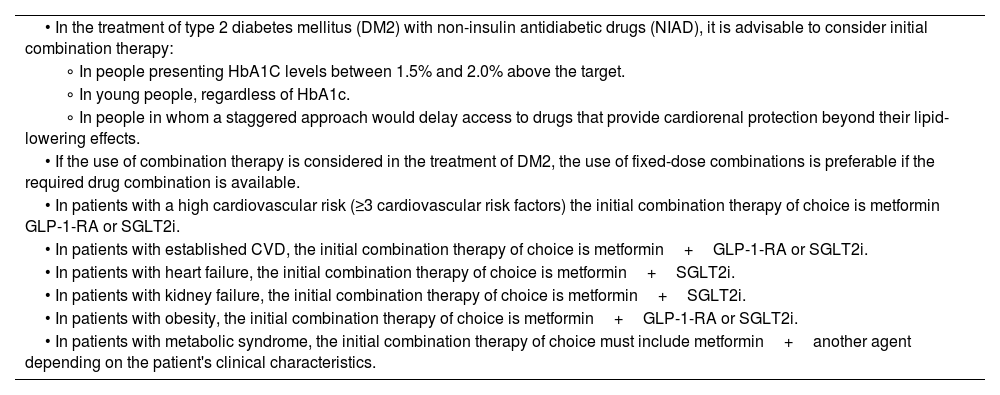

| • In the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) with non-insulin antidiabetic drugs (NIAD), it is advisable to consider initial combination therapy: |

| ∘ In people presenting HbA1C levels between 1.5% and 2.0% above the target. |

| ∘ In young people, regardless of HbA1c. |

| ∘ In people in whom a staggered approach would delay access to drugs that provide cardiorenal protection beyond their lipid-lowering effects. |

| • If the use of combination therapy is considered in the treatment of DM2, the use of fixed-dose combinations is preferable if the required drug combination is available. |

| • In patients with a high cardiovascular risk (≥3 cardiovascular risk factors) the initial combination therapy of choice is metformin GLP-1-RA or SGLT2i. |

| • In patients with established CVD, the initial combination therapy of choice is metformin+GLP-1-RA or SGLT2i. |

| • In patients with heart failure, the initial combination therapy of choice is metformin+SGLT2i. |

| • In patients with kidney failure, the initial combination therapy of choice is metformin+SGLT2i. |

| • In patients with obesity, the initial combination therapy of choice is metformin+GLP-1-RA or SGLT2i. |

| • In patients with metabolic syndrome, the initial combination therapy of choice must include metformin+another agent depending on the patient's clinical characteristics. |

GLP-1-RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors.

Fifty-two (52) panellists participated, and a consensus was reached in 66 of the 80 issues addressed (82.5%), 64 in the first round and two in the second round. The recommendations are summarised in Tables 1–4. Tables S1–S4 (supplementary material) detail the result of the voting per item.

Block I. Generalities about adherenceThe panellists considered that the treatment adherence of patients with CVRF seen in PC is inadequate (item 1) and that it this factor is not taken sufficiently into account in the event of poor CVRF control (item 3). This has relevant clinical implications, because it is associated with a greater morbidity and mortality (item 2).

Moreover, they considered that the use of FCT (in a single pill) may increase treatment adherence in patients with CVRF in PC compared to the treatments given separately (item 10) and that the use of FCT should be encouraged in PC, particularly in multi-medicated patients in order to improve treatment adherence (item 12). Therapeutic inertia reduces the use of FCT in PC (item 11). A consensus was reached on a set of general and specific recommendations and strategies to be implemented in the PC office and which are summarised in Table 1.

No consensus was reached in two questions in this block. The first one (item 4) stated that there is scant availability of fixed-dose drugs for the control of patients with CVRF in PC, and the second (item 5) addressed the existence of the penalisation of healthcare systems for the use of fixed-dose drugs and its negative impact on the improvement of treatment adherence.

Block II. Adherence and hypertensionRegarding the management of HTN, the recommendation was to consider beginning with FCT in most patients in order to achieve control within a maximum term of 3 months (item 35), using FCT that have been proven to reduce long-term cardiovascular events (item 36) and facilitate treatment escalation and make it possible to increase the dose of the drugs included in the combination without switching medication (item 37). Moreover, they recommended that FCT always be used initially in patients with HTN and high cardiovascular risk (item 38). With an eventual triple therapy in mind, the use of FCT with two drugs that are included in triple-drug combinations was recommended to facilitate escalation to triple therapies if necessary (item 42). Moreover, the use of triple-drug FCT should always be considered if the objectives with the FCT are not reached with two drugs.

A consensus was reached on other general recommendations for the management of HTN with combination therapies and specific recommendations depending on the patient's comorbidities (Table 2). The lack of a consensus on the use of calcium channel blockers in patients with other comorbidities (items 45, 47, 50) or in patients with HTN and ischaemic heart disease (item 55) or HTN and atrial fibrillation (item 59) should be noted.

Block III. Adherence and dyslipidaemiasWith regard to dyslipidaemias, the panellists recommended changing the concept of the use of high-intensity statins to the use of high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy (item 60). For hypercholesterolemia, the use of FCT was recommended in patients with high/very high cardiovascular risk (item 62). In both primary prevention (item 64) and secondary prevention (item 66), in general prescribing a fixed dose with a moderate-intensity statin+ezetimibe was considered to be preferable to a high-intensity statin when a high reduction of LDL is required (50%–59%). There was no consensus for when a moderate reduction of LDL (30%–49%) is required (items 65 and 67).

In patients with hypercholesterolaemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus, the use of high-density statins from the beginning was recommended, combined with ezetimibe if necessary (item 68). In these patients, the use of statins was recommended depending on the patient's CVR and the target LDL (item 69).

Block IV. Adherence and diabetes mellitusIn this block, initial combination therapy with non-insulin anti-diabetic agents (NIAD) was recommended in people presenting HbA1C levels of between 1.5% and 2% above the target (item 70), and in people in whom a staggered approach would delay access to drugs that provide cardiorenal protection beyond their lipid-lowering effects (item 72). Moreover, they considered that if the use of combination therapy is addressed in the treatment of DM2, FCT is preferable if the required drug combination is available (item 73) (Table 4). Recommendations were also made for the initial combination treatment of choice depending on other DM2 patient comorbidities which are summarised in Table 4. There was no consensus for using FCT to treat young people regardless of HbA1c (item 71) or for the treatment of frail patients with monotherapy (item 74).

DiscussionThe REAAP is an initiative that addresses the problem of adherence in the management of patients with CVRF from a practical standpoint, thus contributing to the development of advice to help clinicians to improve patients’ therapeutic adherence and, therefore, their clinical evolution. A recently published first project12 included a qualitative study with experts in adherence from different Spanish Autonomous Communities (regions). The following key issues were identified regarding: (1) the approach to adherence in clinical practice, (2) barriers to proper adherence, and (3) interventions to improve adherence. Continuing in the line undertaken by the REAAP, the current project produced a consensus between general practitioners who are experts in adherence and in the management of CVRF which provides recommendations about the treatment of CVRF with FCT in PC with a view to improving treatment adherence and consequently health outcomes.

With regard to the general aspects, the panellists agree that the treatment adherence of patients with CVRF who are seen in PC is inadequate and that this factor is not taken sufficiently into account in the event of poor CVRF control. They opine that this has relevant clinical implications because it is associated with greater morbidity and mortality. These perceptions concur with studies performed in Spain that suggest that approximately only one in every two patients aged ≥65 years adheres to their dyslipidaemia or HTN treatment.15 Similarly, and with regard to NIAD adherence, several studies in our setting suggest that about one in every three patients does not adhere to their DM2 treatment.15,16 The lack of treatment adherence translates into an increase in hospitalisation rates, loss of productivity and increased morbidity and mortality, and the impact goes beyond the effect on individual patient health because it constitutes a huge burden in economic and societal costs.4,17

The FCT, which combine different active ingredients with different mechanisms of action in a single pharmaceutical dosage form, were developed as a response to this lack of adherence that characterises chronic diseases.4 The convenience of taking several active ingredients in a single product facilitates adherence, since it lightens the patient's pill burden.4 The increase in adherence to fixed-dose treatments compared to treatments given separately has been demonstrated in both HTN and in dyslipidaemia or DM2,18,19 as well as in patients with or without a history of CVD.20 Moreover, the use of FCT is associated with greater safety due to the simplification of the dosage routine, which reduces the possibility of confusion when the drugs are taken.4,21 All these benefits are greater than the potential risk of the patient discontinuing therapy and, therefore, all the medications included in the combination.

Besides patient-related factors, doctors’ therapeutic inertia, together with other healthcare system-related factors, such as the associated costs or the lack of treatment availability, may also contribute to the lack of adherence.22 In this regard, no consensus was reached by the panellists when they were asked about the availability of fixed-dose drugs or the existence of a penalisation for prescribing these treatments, suggesting that it does not constitute a limitation on their prescribing in general. It could also indicate the varying availability of FCT and the differing policies regarding their use in the different regions of Spain. For this reason, the approach to improving the use of FCT may involve other channels agreed to by the panellists, such as the improvement of PC specialist training, the establishment of specific care protocols for the management of CVRF with FCT in PC, besides an increase in the role of nursing personnel or the implementation of patient education programmes focusing on adherence. Moreover, numerous specific recommendations are made that can be implemented in the office which include establishing scheduled appointments lasting at least 10min in patients with CVRF in the course of which patients can raise all their questions, fears, beliefs or objections.

Regarding the use of FCT in patients with HTN, the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology and a further 12 medical societies recommend initiating antihypertensive treatment with a two-drug combination in the majority of patients, preferably as a single-pill combination. The exceptions are frail elderly patients and patients with low-risk and stage 1 hypertension (particularly if SBP <150mmHg). They recommend that combinations include an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), together with a calcium channel blocker or a diuretic, although other combinations of the five main classes (ACE inhibitor, ARB, beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, thiazide/thiazide-type diuretic) may be used. The choice of the best antihypertensive treatment strategy must take the overall CV risk profile, the primary or secondary prevention setting, comorbidities and treatment adherence of each patient into account.23 In this regard, the panellists make some recommendations depending on the comorbidities and they seem to lean more towards the combined use of an ACE inhibitor or an ARB with a diuretic rather than a calcium channel blocker in patients without other comorbidities. Moreover, they recommend anticipating that the patient may require triple therapy and use FCT therapies that facilitate treatment escalation and make it possible to increase the dose of the drugs included in the combination without switching medication. Therefore, it would be advisable to use two-drug FCT included in triple-drug FCT. They also recommend the use of fixed-dose combination therapies that have been proven to reduce CV events in the long term, such as FCT with perindopril, indapamide and amlodipine.24

With regard to dyslipidaemia, the panellists recommend talking about high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy rather than high-intensity statins. The available evidence indicates that the clinical benefit in CV prevention does not depend so much on the type of lipid-lowering treatment as on the degree of reduction in LDL attained with this treatment, which is why they recommend switching from the concept of high-intensity statins to that of high-intensity lipid-lowering therapy.25–27 This is a relevant change of paradigm, because it includes other treatments, such as ezetimibe, which may boost the effect of statins combined in fixed doses. In this same line, the panellists emphasise the use of FCT with a moderate-intensity statin+ezetimibe compared to high-intensity statins when a high reduction in LDL (50%–59%) is required in both primary and secondary prevention.

Finally, a combined treatment is frequently necessary in the management of DM2.11,28 The panellists make some recommendations about their initial use or in patients with DM2 and other comorbidities. With regard to FCT in DM2, the panellists consider that the use of fixed-dose combinations is preferable if the required combination of drugs is available. There is no recommendation for groups of patients of extreme ages or situations (young and frail).

Our work has the limitations inherent in the Delphi method, which means that it is impossible to discuss the recommendations in depth or that there could have been some bias in the selection of the panellists. However, the scientific committee took the panellists’ comments into consideration when drafting the discussion, and the choice of participants was made prudently and included only physicians with accredited experience in this field.

ConclusionsIt is necessary to create or increase awareness among professionals about treatment adherence in order to achieve the control objectives in patients with CVRF. The use of FCT may increase adherence in this setting, although it is necessary to establish protocols, improve the training of professionals and to encourage their use in PC. The consensus-based recommendations given regarding the use of FCT in HTN, dyslipidaemia or DM2, may help to increase the use of FCT in PC and consequently increase the adherence and health outcomes of patients with CVRF.

Ethical considerationsThis article is based on the clinical practice reported by general practitioners and does not contain any study with human participants or animals. The questionnaire sent to the general practitioners did not collect patient data.

FundingThe REAAP project was funded by Servier, which provided logistical support, including publication service and medical writing fees.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the panellists for their collaboration in the study. The list of the panellists is provided below:

Antonio Abril Rubio (Málaga); Josep Alins Presas (Barcelona); Ezequiel Arranz Martinez (Madrid); Francisco Atienza Martin (Sevilla); Custodio Buil Ferrero (Barcelona); Maria Carnicero Iglesias (Ourense); José Manuel Carvajal Jaén (Sevilla); Marta Casado Marcos (Burgos); Ana María Cieza Rivera (León); José Manuel Comas Samper (Toledo); Natalia Diaz Ferreiros (Asturias); Jose Fausto Franco Pineda (Murcia); Manuel Frias Vargas (Madrid); Paula Gago Chaguaceda (Salamanca); Alberto García Cabello (Ávila); Lisardo Garcia Matarín (Almería); Leticia Gómez Sánchez (Cádiz); Antonio Gonzalez Cabrera (Albacete); Amanda González González (Valladolid); Paula Juárez Gonzálvez (Cáceres); María Dolores Just Cardona (Valencia); Francisco Manuel Lidón Muñoz (Alicante); Jaime López De la Iglesia (León); Henry Luis (Barcelona); Juana María Machado Gallas (Ávila); Manuel Luis Mellado Fernández (Cádiz); Sonia Miravet Jiménez (Barcelona); Francisco Jesús Morales Escobar (Gran Canaria); Manuel J. Mozota Núñez (Navarra); Vicente Olmo Quintana (Gran Canaria); Tania Ortiz Puertas (Granada); Miren Itxaso Orue Rivero (Bizkaia); Viviana Rocio Oscullo Yépez (Madrid); José Luis Pardo Franco (Alicante); David Pedrico Farré (Tarragona); Juan Fernando Peiró Morant (Islas Baleares); Isabel Maria Peral Martinez (Murcia); María Paz Pérez Unanua (Madrid); Jose Carlos Pérez Sánchez (Málaga); Ana Piera Carbonell (Asturias); Marta Porta Tormo (Valencia); Daniel Rey Aldana (Pontevedra); Antonio Rivas Mena (Tenerife); Juan Carlos Romero Vigara (Zaragoza); Antonio Ruiz García (Madrid); Elisa Pilar Salazar Gonzalez (Zaragoza); Ana María Sánchez Sempere (Madrid); Alberto Serrano López de las Hazas (Madrid); Miguel Turégano Yedro (Cáceres); María Esther Uceda Gómez.

We would like to thank Dr Pablo Rivas for the editorial support he provided in writing this article on behalf of Content Ed Net.

Representing the Grupo de Trabajo Gestión del Medicamento, Inercia clínica y Seguridad del paciente [Medication Management, Clinical Inertia, Patient Safety Working Group] of SEMERGEN.