Sarcopenia and metabolic syndrome are present in a large percentage of the elderly population throughout the world. Much of its management is focused on primary prevention, and considering that sleep disturbances also accompany the same aging process associated with these two pathologies, we propose a relationship between sleep impairment and the development of sarcopenia in individuals with metabolic syndrome. A search was carried out in databases following he PRISMA scheme, obtaining fifteen studies. As for the main results: four of eight studies referring to sleep duration relate more than nine hours of sleep with an increased risk of sarcopenia, three of the five studies relate poorer sleep quality with worse body composition data or increased risk of sarcopenia and two studies related late chronotype with a higher risk of sarcopenia and metabolic syndrome. After analyzing the disparity of outcomes, it is necessary to homogenize methodologies to compare the different results.

La sarcopenia y el síndrome metabólico están presentes en un gran porcentaje de la población anciana a nivel global. Gran parte de su manejo se centra en la prevención primaria, y teniendo en cuenta que las alteraciones del sueño también acompañan al mismo proceso de envejecimiento asociado a estas dos patologías, proponemos una relación entre la alteración del sueño y el desarrollo de sarcopenia en individuos con síndrome metabólico. Se realizó una búsqueda en bases de datos siguiendo el esquema PRISMA, obteniéndose quince estudios. Cuatro de los ocho estudios referidos a la duración del sueño relacionan más de nueve horas de sueño con un mayor riesgo de sarcopenia, tres de los cinco estudios vinculan una peor calidad del sueño con mayor riesgo de sarcopenia, y dos estudios asocian el cronotipo tardío con un mayor riesgo de sarcopenia y síndrome metabólico. Tras analizar la disparidad de resultados, resulta necesario homogeneizar las metodologías para poder comparar las diferentes conclusiones.

Over the last two decades, there has been a considerable increase in global life expectancy. The previous WHO (World Health Organization) report published in 2023 on global health statistics rated 73.4 years of life expectancy in 2019 – while in 2000, life expectancy stood at 66.8 years – and is expected to reach 77 years in 2048.1 According to the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), this increase is due to a rise in healthcare spending, better education, higher income, and healthier lifestyles.2 This last point has been analyzed in numerous studies.3,4 For example, Harvard University has determined that changing five essential habits (healthy diet, exercising regularly, controlling body weight, not abusing alcohol, and not smoking) in the adult population can lead to an increase in life expectancy of 14 years in the case of women and 12 years in the case of men.5 However, an increment in life expectancy implies an increase in morbidity6 and chronic diseases such as metabolic syndrome,7 or sarcopenia.8

This study defines sarcopenia as a degenerative disease characterized by a reduction in muscle mass with a consequent and progressive loss of strength over the years.9 Although some studies establish it is prevalent in 10% of the population,10 it is estimated that this percentage may be higher due to underdiagnosis.11 The consequences of sarcopenia are multiple and affect different areas. From an economic point of view, as early as 2003, it was estimated that 18.5billion dollars spent annually in the United States were associated with sarcopenia-related expenses,12 such as an increase in the duration of hospitalizations.13 A more recent study published in Europe in 2016 points to a rise in hospital admission costs of 58.5% in patients under 65 years of age due to sarcopenia.14 On the other hand, the consequences and implications on health are wide-ranging from a sanitary point of view. These include an increase in bone fractures, an increment in risk of mortality, and a deterioration in the functionality and independence of the patient.15–17

On the other hand, the Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) encompasses the set of conditioning factors that – in combination – increase the risk of suffering from specific pathologies that accompany the aging process. Although there are discrepancies between the different scientific associations when it comes to including the different conditions that make up MetS, we will stick to those agreed upon by most of them, namely: insulin resistance, hypertension, abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL (high-density lipoprotein) levels.18 Understanding the influence and interaction of these diseases with other pathologies becomes relevant in terms of their high prevalence among the current population and their enormous interference with these individuals’ health-related quality of life.19 Already in 2012, a study published in the Spanish Journal of Cardiology established a prevalence of MetS of 31% in the Spanish population,20 and it is to be expected that this figure may have been increasing in recent years. A subsequent study quantified at 36.9% the prevalence of MetS in 2016 in the United States population,21 impacting a more significant increase in the diagnosis of young adults in recent years.

Since both sarcopenia and MetS lead to a process of progressive deterioration, much of its treatment focuses on delaying the progression of the disease through the same actions that limit and prevent its onset.22 Prevention consists of making a series of changes in behavioral patterns associated with modifiable risk factors. Several studies point out how balanced nutrition23 and moderate physical exercise24 positively affect the prevention of the development of sarcopenia and chronic diseases associated with MetS, such as diabetes or hypertension. However, a less studied aspect is sleep and its association with sarcopenia, an association that has already been established by some authors25 between sleep and metabolic syndrome.

A recent review published in 2022 titled “Inflammaging: implications in sarcopenia”26 highlights some critical issues in understanding the underlying interrelationships between age, sarcopenia, and metabolic syndrome. It opens the door to possible implications for the sleep process. Thus, it points to the chronic inflammation associated with age and metabolic syndrome as one of the factors responsible for the development of sarcopenia.

Therefore, due to the scarcity of studies encompassing these characteristics, it is necessary to review the published evidence to draw conclusions that may guide new research needs. This systematic review attempts to evaluate the possible relationship between sleep and sarcopenia in individuals with metabolic syndrome, suggesting that a deterioration in sleep quality or duration leads to an increase in the occurrence of sarcopenia in individuals with metabolic syndrome.

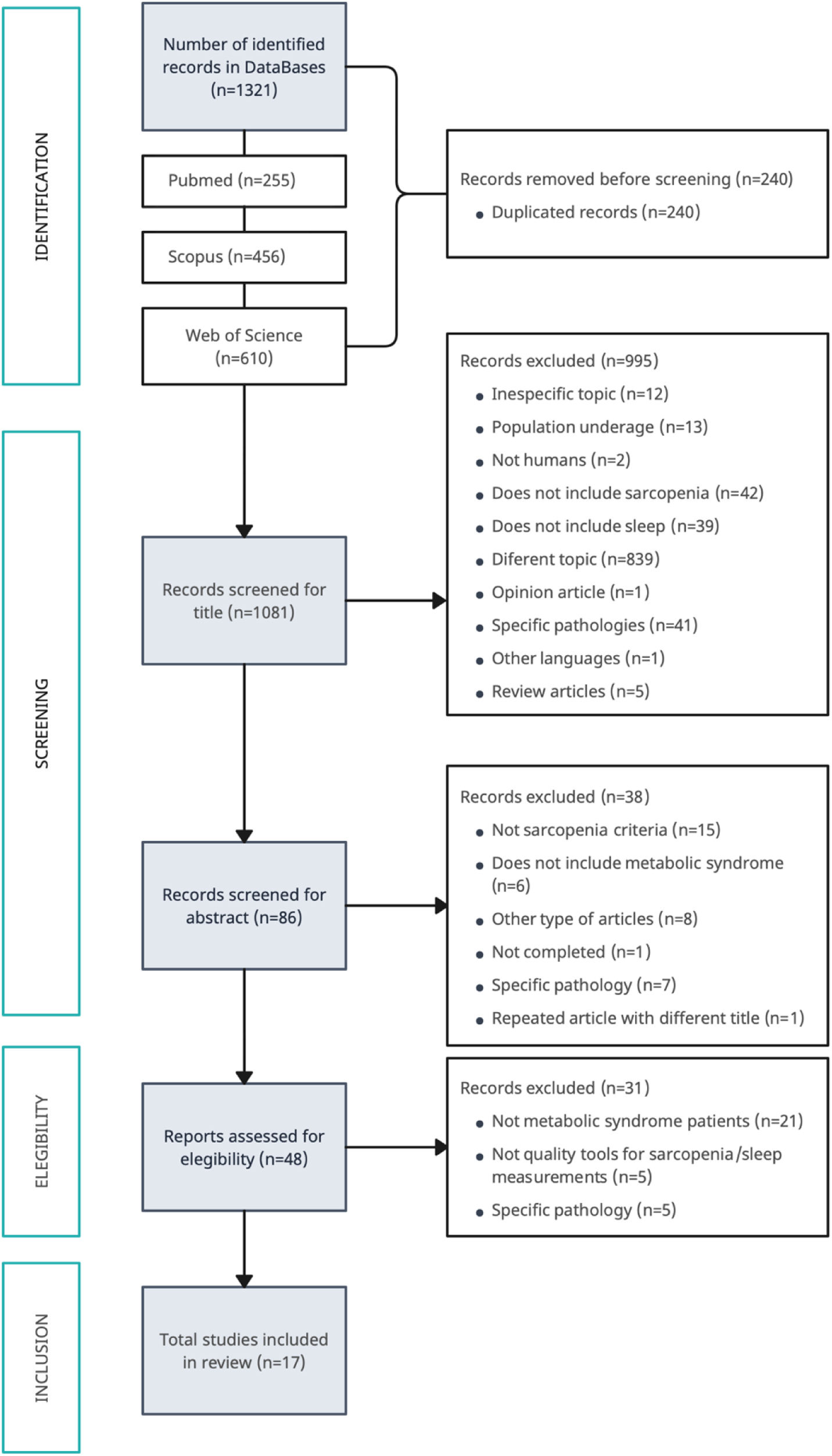

MethodsStudy designThis systematic review was carried out following the guidelines of the PRISMA guide,27 and the review protocol is registered in PROSPERO with registration number CRD42022337015.

For the selection of the studies, the inclusion criteria were articles in Spanish or English dealing with the influence of sleep quality on sarcopenia, whose population was 18 years or older, cross-sectional or cohort study design, and which included metabolic syndrome criteria among the study population.

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria were studies with a younger population, studies whose individuals suffered from a specific acute pathology, and studies for which an open-access version was unavailable.

Search strategies and data sourcesThe initial search was conducted from March 2022 to October 2023 in the following databases: Web of Science, Pubmed, and Scopus. The inclusion and exclusion criteria described previously were followed for filtering by title and abstract. No temporality criteria were established when selecting the articles. Fig. 1 shows the diagram of this search process. As can be seen, after the initial search in the databases, 1321 articles were obtained, and 17 of them were finally included in this review.

In addition, to facilitate the focus of the study, the following PICO question was established following the Patient-Intervention-Comparison-Results criteria:

P (patients with sarcopenia and metabolic syndrome), I (measurement of the quality/quantity of sleep), C (patients who sleep the recommended daily amount of hours vs. those who do not sleep it -by excess or default- or the quality is not adequate), O (results of the affectation of the degree/severity of sarcopenia in patients with metabolic syndrome criteria according to the quantity/quality of sleep).

Once the research question was posed, the MeSH keywords and boolean operators were established to start the search, being: ‘Sarcopenia’ OR ‘muscle strength’ OR ‘muscular atrophy’ AND ‘metabolic syndrome’ OR ‘obesity’ OR ‘insulin resistance’ OR ‘abdominal obesity’ OR ‘diabetes mellitus, type 2’ OR ‘hypertension’ OR ‘dyslipidemias’ OR ‘cardiovascular diseases’ AND ‘sleep’ OR ‘sleep disorders’ OR ‘sleep hygiene’.

Screening guidelinesA first researcher (IFG) searched the databases mentioned earlier and downloaded the titles, authors, IDs, and journal of the articles resulting from the search, unifying them in a Microsoft Excel file. After discarding duplicates, two researchers independently performed the first filtering (IFG, DCP).

Articles that were identified as “discarded” by both investigators were definitively excluded, while articles that were identified as “doubtful” or “accepted” by both investigators were included.

Those articles that implied a discrepancy were discussed between both researchers, with the support of other authors (PYG) (AMD), and categorized as accepted or discarded depending on the agreement reached.

Finally, the articles included in this review were selected after being read thoroughly.

Data extractionOnce the articles were selected, a comparative table of their contents was made, including the following information: author and year of publication, country of origin of the study, type of study, sample size, age (range, mean and standard deviation) and distribution by sex, data collection instruments (referring to sleep quality/duration and body composition/degree of sarcopenia) and conclusions or relevant information.

Assessment of risk of biasThe risk of bias assessment of each article included in this analysis was carried out by IFG using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist tool specifically for either cross-sectional studies28 or cohort studies29 and reviewed by TFV, LBJ, and AMD.

This tool poses eight questions to assess the risk of bias, each of which can be answered as “Yes,” “No,” “Unclear,” and “Not Applicable.”

Regarding cross-sectional studies, a final score of 7/8 and 8/8 was assumed to be low risk, a score of 6/8 was taken as medium risk, and figures below these were classified as high risk. It was decided to exclude from the review those articles that resulted as “high risk.”

Evaluating cohort studies, a final score higher than 9/11 was assumed to be a low risk, 5–8 out of 11 was considered medium risk, and a score lower than 5/11 was classified as high risk.

Data synthesisThe primary data from the 17 studies were compiled in tabular form according to descriptive criteria. It was agreed to divide the studies according to the measured sleep characteristics, resulting in a table structured in four sections: sleep quantity (in hours), sleep quality, obstructive sleep apnea, and chronotype. Within each category, the studies were arranged in chronological order.

ResultsSearch resultsFollowing the selection process, 17 articles were considered for the present review. These publications date from 2009 to 2022, and more than half correspond to Asian studies. From a structural point of view, 15 of the 17 articles correspond to cross-sectional studies, while only two belong to cohort research. Table 1 compiles the main characteristics and conclusions of all the studies mentioned above.

Main characteristics and conclusions about the studies included.

| Mean author/year | Country/study design | Sample | Tools for data collection | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration studies | ||||

| Lee et al., 202245 | KoreaCohort (2 years) | N=135370–84 years53.4% female | - Sleep data: PSQI, self-reported question (sleep duration and latency)- Body composition: DEXA- Physical fitness: handgrip strength, usual gait speed, 5-time chair stand test, SPPB score (Short Physical Performance Battery) | - Long sleep duration was associated with a higher incidence of sarcopenia only in men (OR 2.41, CI 95%: 1.125–5.166, p=0.024).- The association is found in low muscle mass and strength parameters. This association does not occur in the parameter of physical performance. |

| Lu et al., 202230 | ChinaCross-sectional | N=1407≥65 yearsMean: 71.91SD (5.59)58.7% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question (seven days)- Body composition: BIA- Physical fitness: handgrip strength, gait speed (6meters walking test), 5-time chair stand test | - Short sleep duration is associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia (OR 0.561, CI 95%: 0.346–0.909, p=0.019). |

| Han et al., 202246 | ChinaCohort (3 years) | N=754≥60 years56.7% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question- Body composition: BIA- Physical fitness: handgrip strength, gait speed (4 meters walking test) | - Both long (OR 1.84, CI 95%: 1.07–3.14) and short (OR 2.74, CI 95%: 1.05–7.13) sleep duration associated with increased diagnosis of sarcopenia (p=0.001). |

| Smith et al., 202243 | China, Ghana, India, Russia, South AfricaCross-sectional | N=13,210≥65 yearsMean: 72.6SD (11.3)55.0% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question (two nights)- Body composition: SMI- Physical fitness: handgrip strength, gait speed (4 meters walking test) | - Long sleep is associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia (OR 2.19, CI 95%: 1.26–3.81, p<0.001) and severe sarcopenia (OR 2.26, CI 95%: 1.20–4.23, p<0.05) in women. |

| Petermann-Rocha et al., 202031 | United KingdomCross-sectional | N=396,28338–73 years52.8% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question- Body composition: BIA- Physical fitness: IPAQ (International Physical Activity Questionnaire) | - No associations found between sarcopenia and short or long sleep. |

| Kim et al., 201832 | KoreaCross-sectional | N=3532≥40 yearsMean: (54.82)SD 1.0656.4% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question- Body composition: DEXA, ASM/weight (muscle mass percentage) | - Long sleep in women is associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia (OR 1.77, CI 95%: 1.06–2.96, p<0.001). |

| Kwon, MD et al., 201733 | KoreaCross-sectional | N=16,148>20 yearsMean: 44.1SD 0.255.7% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question- Body composition: DEXA | - Long sleep duration (9h or longer) is independently associated with sarcopenia in Korean adults (OR 1.621, CI 95%: 1.100–2.295) |

| Chien et al., 201534 | TaiwanCross-sectional | N=448≥65 yearsMean: 76.8SD 6.954.6% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question, PSQI- Body composition: BIA | - Short sleep in older women is associated with obesity.- U-shaped pattern shows an association between sleep duration and sarcopenia: <6h (OR 2.76, CI 95%: 1.28–5.96) and ≥8h (OR 1.89, CI 95%: 1.01–3.54) p=0.001. |

| Sleep quality studies | ||||

| Szlejf et al., 202135 | BrazilCross-sectional | N=7948≥50 yearsMean: 59.5SD 6.953.7% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question (sleep duration and insomnia), Stop-bang questionnaire (OSA)- Body composition: BIA- Physical fitness: handgrip strength (dynamometer) | - High risk of OSA associated with low muscle mass (OR 2.17, CI 95%: 1.92–2.45, p<0.001).- High risk of OSA associated with low muscle strength (OR 1.68, CI 95%: 1.07–2.64, p=0.024) and low muscle mass (OR 1.68, CI 95%: 1.40–2.02, p<0.001) in obese.- No associations were found between sarcopenia and sleep duration or insomnia. |

| Vargas et al.,202136 | ChileCross-sectional | N=2618–60 yearsMean: 39.9SD 11.3100% female | - Sleep data: PSQI- Body composition: BIA- Physical fitness: 6MWT (Six-minute walking test), hand grip strength | - Poor sleep quality associates negatively with body fat percentages (OR 8.39, CI 95%: 1.13–62.14, p=0.037), morbid obesity (OR 8.44, CI 95%: 1.15–66.0, p=0.036), metabolic outcomes (OR 8.44, CI 95%: 1.15–66.0, p=0.036) and low HGS (OR 12.2, CI 95%: 1.79–83.09, p=0.011). |

| Piovezan et al., 201937 | BrazilCross-sectional | N=359>50 yearsMean: 61SD 8.859.1% female | - Sleep data: PSQI, ESS, UNIFESP Sleep Questionnaire (for evaluating insomnia), actigraphy, polysomnography- Body composition: BIA | - OSA associates with sarcopenic obesity (OR 3.14 CI 95%: 1.49–6.61, p<0.0001).- Nocturnal hypoxemia associated with sarcopenic obesity (OR 2.92, CI 95%: 1.49–4.49, p<0.0001) and general obesity (OR 2.59, CI 95%: 1.39–6.13, p<0.0001).- No associations between sleep quality and sarcopenia. |

| Lucassen et al., 201738 | NetherlandsCross-sectional | N=91545–65 yearsMean: 55SD 656.0% female | - Sleep data: PSQI- Body Composition: DEXA | - Decreased sleep quality (OR 1.10, CI 95%):1.02–1.19), sleep latency (OR 1.14, CI 95%: 1.03–1.14), and later sleep timing (OR 1.54, CI 95%: 0.91–2.61) associates with increased risk of sarcopenia, firmly in women and with influences of menopausal status.- Sleep duration did not affect the risk of sarcopenia. |

| Kim et al., 201539 | JapanCross-sectional | N=191 total80–92 yearsMean: 83.4SD 2.6100% female | - Sleep data: triaxial accelerometer- Body composition: DEXA | - An inconsistent sleep–wake correlates with higher fat mass (β=0.170, CI 95%: 0.038–0.303, p<0.05) and lower lean mass figures (percentage lean mass β=−0.168, CI 95%: -0.304–0.032, p<0.05). |

| OSA studies | ||||

| Stevens et al., 202040 | AustraliaCross-sectional | N=61341–88 yearsMean: 63100% male | - Sleep data: polysomnography- Body Composition: DEXA- Physical fitness: hand grip measurement with dynamometers | - Severity of OSA associated with lower HGS (OSA indices such as Oxygen nadir: β=0.20, CI 95%: 0.10–0.31, p<0.001) data and increased whole body fat mass percentages (OSA indices such as T90%: β=0.10, CI 95%: 0.05–0.16, p<0.001 95% p<0.001). |

| Endeshaw et al., 200941 | USACross-sectional | N=1042≥65 yearsMean: 77SD 456.0% female | - Sleep data: polysomnography- Body composition: BMI (body mass index), self-reported unintentional weight loss- Physical fitness: walking speed, dynamometer, Modified Minnesota Leisure Time Activities (physical activity questionnaire), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale questionnaire (for exhaustion evaluation) | - Severe sleep-disordered breathing in women associated with slow walking speed (OR 2.67, CI 95%: 1.04–6.84), low grip strength (OR 3.29, CI 95%: 1.36–7.96), and frailty indicators (OR 4.85, CI 95%: 1.40–16.78). |

| Sleep chronotype studies | ||||

| Xu et al., 201844 | ChinaCross-sectional | N=2412>60 years42.0% female | - Sleep data: self-reported question- Body Composition: BIA- Physical fitness: dynamometer, 6MW (gait speed), RCS (repeated chair stands), TUG (Timed Up and test) | - Daytime sleep associated with high ALM/Ht2 (low ALM/Ht OR 0.78, CI 95%: 0.63–0.98, p=0.032) and faster RCS (long RCS OR 0.77, CI 95%: 0.65–0.92, p=0.004).- MetS associated with slower gait speed. (OR 1.38, CI 95%: 1.09–1.76, p=0.008). |

| Yu et al., 201542 | KoreaCross-sectional | N=162047–59 yearsMean: 52.96SD 350.6% female | - Sleep data: PSQI, ESS (Epworth Sleepiness Scale), MEQ (Horne–Ostberg Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire)- Body composition: DEXA | - Late chronotype associated with sarcopenia (OR 3.16, CI 95%: 1.36–7.33) and diabetes (OR 1.73, CI 95%: 1.01–2.95) in men, independent of sleep duration.- Evening chronotype associated with MetS in women independent of sleep duration (OR 2.22, CI 95%: 1.11–4.43). |

Meaning of acronyms included inTable 3: N: study sample; SD: standard deviation; SMI: Skeletal Muscle Index; BIA: Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis; SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery; IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire; DEXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; ASM: appendicular skeletal muscle mass; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; T90%: amount of sleep with oxygen saturation below 90%; 6MWT: 6meters walking test; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; UNIFESP: Universade Federal de Sao Paulo; HGS: hand grip strength; RCS: repeated standing; TUG: Timed Up and test; ALM: appendicular lean mass; MEQ: Horne–Ostberg Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire; RCS: repeated standing.

The 15 cross-sectional studies included in the analysis were evaluated using the risk of bias tool created by JBI for cross-sectional studies. Thirteen of the articles obtained a low risk of bias,29–41 while the remaining two studies43,44 obtained a medium risk of bias. The main reasons for these lower scores were poorly objective sleep measurement scales, less recommended sarcopenia measurement methods, and unclear descriptions of the study sample. No articles were discarded due to a high risk of bias (see Table 2).

JBI Checklist for cross-sectional studies.

| 1. Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 2. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way?a | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 4. Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition?a | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 5. Were confounding factors identified? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 6. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way?a | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 8. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration studies | |||||||||

| Lu et al.30 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Smith et al.43 | Yes | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6/8 |

| Petermann-Rocha et al.31 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Kim et al.32 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Kwon et al.33 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Chien et al.34 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 |

| Sleep quality studies | |||||||||

| Szlejf et al.35 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Vargas et al.36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Piovezan et al.37 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 |

| Lucassen et al.38 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 |

| Kim et al.39 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/8 |

| OSA studies | |||||||||

| Stevens et al.40 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Endeshaw et al.41 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

| Chronotype studies | |||||||||

| Xu et al.44 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6/8 |

| Yu et al.42 | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7/8 |

The remaining two articles are cohort studies. Both obtained a punctuation of 8 out of 11 on the checklist. The main reasons for the unchecked standards were poorly objective sleep measurement scales and unclear descriptions of the sleep group's proportion (see Table 3).

JBI Checklist for cohort studies.

| 1. Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 2. Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to both exposed and unexposed groups? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way?a | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 4. Were confounding factors identified? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 5. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 6. Were the groups/participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or at the moment of exposure)? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 8. Was the follow up time reported sufficient to be long enough for outcomes to occur? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 9. Was follow up complete, and if not, were the reasons to loss to follow up described and explored? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 10. Were strategies to address incomplete follow up utilized? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| 11. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

As seen in the first section of Table 1, eight of the seventeen studies included in this systematic review have the influence of sleep duration on sarcopenia as their object of study. The publishing period of these articles ranges the years 2015–2022. All of them have large study samples and cover both sexes. They all measure sleep duration through a simple self-answered question. Only two34,45 use the validated PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) questionnaire to obtain sleep quality and quantity.

Seven of the eight articles use sarcopenia diagnostic measures standardized by the EWGSOP2 (European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People) algorithm, such as bioimpedance (BIA)30,31,34 or bone densitometry (DEXA)32,33,45 while one of them43 uses Skeletal Muscle Index (SMI) and tools used in its grading (hand grip and gait speed).

As for the results, only one does not establish associations between the variables.31 Four studies32,33,43,45 find a positive relationship between long sleep duration and the risk of sarcopenia. However, the first two only establish it in women, and the last only in men. Only one study30 directly relates the few hours of sleep (<6h) with a higher risk of sarcopenia. Finally, two authors34,46 establish a parabolic function between sleep duration and the risk of sarcopenia.

Results in “Sleep quality studies”Regarding studies relating sleep quality to sarcopenia, five articles published between 2015 and 2021 were analyzed. Two36,39 are based on a 100% female study sample. The other three studies35,37,38 include population-based samples with more equal distributions.

Regarding data collection methods, three studies35,36,38 are based on questionnaires or self-reported questions (simple questionnaire, validated PSQI questionnaire, and validated Stop-Bang questionnaire for assessing obstructive sleep apnea). Only two of them resort to more objective methods, such as actigraphy and polysomnography, in addition to self-reported questionnaires37 or triaxial accelerometry.39 On the other hand, body composition was mainly studied employing BIA. Only two authors38,39 used DEXA. Two authors included physical fitness assessments, both utilizing the dynamometer35,36 and, in addition, the 6MWT (six-meter walking test).36

As for the results, three of them found associations between poor sleep quality and body composition outcomes: increased body fat percentage, metabolic and fitness alterations,36 increased fat mass and reduced lean mass,38 and an association with sarcopenia in women.38

The remaining two articles, although they do not establish positive associations between sleep quality and sarcopenia, do establish positive associations between the risk or suffering from obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and low muscle mass and low muscle strength in obese persons,35 and sarcopenic obesity37 (also directly associating general and sarcopenic obesity with nocturnal hypoxemia).

Results in “OSA studies”Two cross-sectional studies evaluating the association of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA) with sarcopenia were examined.

In 2009, a study was published in the United States with 1042 participants aged 65 years or older, 56% of whom were women.41 It used polysomnography to obtain data related to sleep and the degree of OSA and hypoxemia; it also employed the dynamometer and standardized questionnaires to evaluate physical activity and the degree of exhaustion, quantification of weight loss, and walking speed. As a result, an independent direct association measure is obtained between the severity of respiratory disorders during sleep and slower walking speed, lower grip strength, indicators of frailty, and dependence on basic activities of daily living (frailty reflexes in older adults).

More recently, in 2020, the survey by Stevens et al. analyzed a sample of 613 individuals between 41 and 88 years of age, all men.40 It used polysomnography to measure sleep/apnea, DEXA as a measure of body composition, and the dynamometer as a measure of grip strength. In conclusion, it highlights the independent positive association between OSA and lower grip strength and higher fat mass; this association is not established with muscle mass.

Results in “Chronotype studies”Finally, the articles summarized in the last section of Table 1 show the chronotype. The two studies analyzed on the chronotype-sarcopenia relationship are of Asian origin. Both have a large population sample, although one selects older individuals for its research44 (>60 years) in the case of Xu et al. as opposed to Yu et al., whose sample ranges from 47 to 59 years of age.42

There are also differences when measuring sleep-related parameters; while Xu et al. resort to Self-reported individual response, Yu et al. extend his tools to the PSQI, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and the Horne–Ostberg Morningness–Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ) (all validated questionnaires).

As for the diagnosis and assessment of sarcopenia, both use tools included in the EWGSOP2: BIA, dynamometer (grip strength), 6MWT, and Timed-Up and test (TUG) are used in the first study44; DEXA is the resource selected in the second one.42

In assessing the results, Xu et al. describe a positive correlation between daytime sleep and higher ALM/Ht2 ratio results (lean body mass index in upper and lower limbs) and faster results in the Repeated Chair Stand (RCS) test. Another noteworthy observation of this study is the association between metabolic syndrome and lower UGS (Usual Gait Speed) test scores.

By contrast, Yu et al. conclude their study with a direct and independent correlation between late chronotype and diabetes, sarcopenia (in men), and metabolic syndrome (in women).

DiscussionAs initially stated, the main objective of this review was to examine and summarize the primary scientific evidence published to date regarding the influence of sleep and its disorders on sarcopenia in patients with metabolic syndrome.

Firstly, it is important to describe two of the risk factors that generate the main results in the studies analyzed: sex and age. It should be noted that both are non-modifiable risk factors, so their importance is major when it comes to classifying the population to apply the different preventive interventions.

On the one hand, taking into account the different results in terms of sex, we found three studies32,38,43 that establish relationships between sleep and sarcopenia only in women, all of them relating it to sleep of more than 8h. All three articles have in common that they analyze sleep in a self-reported manner and through questionnaires. However, Kim et al. (2018) and Lucassen et al. analyze a younger sample (mean age around 55 years) than other studies included in this review.

Diverging slightly from these results, two authors (both referring to sleep quality studies) found no association between worsened sleep quality and sarcopenia in all-female samples but with fitness (low HGS), altered metabolic outcomes,35 and body composition (body fat percentages, lower lean mass36,39 and morbid obesity36). It should be noticed that one of the samples36 is remarkably small and around 40 years of age on average, while the other,39 larger, represents a more aged population.

As for the results in men, two articles establish a relationship with the male sex. Both employed DEXA and self-reported questionnaires for data extraction. While one of them42 establishes in its cross-sectional study the relationship in late chronotype (regardless of sleep duration) with both sarcopenia and diabetes, the other one45 relates in its cohort study a prolonged sleep duration with the appearance of sarcopenia. Interestingly, the first author42 obtains an association between evening chronotype and Mets only in women.

These sex differences have already been analyzed by several authors, finding answers in the differences in the body composition of men and women (greater muscle mass, skeletal muscle mass, and potassium levels in men than in women47,48 or the hormonal influence related to testosterone and estrogen levels.49,50 Nevertheless, this issue is still controversial, as Gao et al., in their systematic review with meta-analysis of 202,51 found no difference in the prevalence of sarcopenia between men and women.

It is essential to consider the sample age since a more significant senescence of the population is associated with a higher incidence of both metabolic syndrome52 and sarcopenia.53 There are multiple reasons for this: accumulation of risk factors, lifestyle changes, changes in hormone secretion (both insulin and sex hormones at menopause), and inflammation.26 In this aspect, the mean ages of the samples in each study differ significantly. Within this review, there are articles with mean age samples under 45 years33,36 and unequal conclusions; in contrast, an article with a mean age sample over 8039 found an association between low sleep quality (inconsistent sleep–wake pattern) and the mainstay of sarcopenic diagnosis – the decrease in lean mass accompanied by an increase in fat mass.

However, it is necessary to point out a limitation in the availability of relevant data concerning age since four of the reports included in this review do not present the mean age of the study sample. This makes it difficult to extract or compare results on this age issue.

Concerning sleep, it is crucial to take into account the method used to measure it since, as shown in other studies,54–56 the self-perception of the duration or quality of sleep does not always correspond to that shown by other more objective methods such as polysomnography or actigraphy. The vast majority of the articles presented in this review use self-reported questionnaires to measure sleep, and only three40–42 employ more objective methods. Two out of these three studies belong to those related to “OSA studies”, and the third one to “Sleep chronotype studies”. Interestingly, the OSA studies conclude without associating sleep with sarcopenia, while the third one42 associates late chronotype with sarcopenia in men, independent of sleep duration. However, they establish associations with worse body composition,40 higher frailty indicators41 and Mets in women.42 These more objective sleep measurement methods bring greater weight to be considered more rigorous studies.

Another association that has already been studied has been the quality and duration of sleep with parameters related to sarcopenia, as in the 2020 review by Pana et al.57: sleep intervenes both in hormonal pathways (both catabolic and anabolic) and in the inflammatory response of the organism, both of which affect muscle metabolism. In addition, it underlines a lower physical activity in individuals who spend more time in bed. This would be in line with the study by Lucassen et al. but is contrary to the results of the other four studies included in the “sleep quality” category.

On the other hand, a review carried out58 concerning the sleep duration-sarcopenia association concludes by establishing a parabolic relationship between sleep and sarcopenia in women. In contrast, men are only affected by long sleep duration. This parabolic relationship also appears in the analyzed articles by Chien et al. and Han et al., although none of them discriminate the results by sex.

Another vertex of the possible interactions in this sleep-sarcopenia-metabolic syndrome triangle was also analyzed. Although the relationship between the influence of metabolic syndrome on sarcopenia is clear,59,60 the association of “sleep duration” with the presence of metabolic syndrome is less so. Although some studies relate a short sleep pattern with increased presence61 and incidence62 of metabolic syndrome, these relationships are not sufficiently studied. Stefani et al. (2013)63 present an article concluding with age- and gender-associated differences in the relationship between sleep-metabolic syndrome. In this article, the highest prevalence rates of metabolic syndrome appear in middle-aged women with a sleep pattern of less than 5h/day. This statement conflicts with the results found in the review since most of the associations established have long sleep patterns.

Although we have schematized the multiple components and relationships that make up our study to facilitate their understanding, the aim of this review is to encompass and understand them all, without isolating them, so that the study population can be visualized as a whole, composed of its different characteristics, pathologies, risk factors, etc. in constant interaction. This holistic view of human health64 and its determinants will allow us to create more realistic policies and interventions.

From this point of view, the aforementioned article by Antuña et al.26 offers some insights into this inflammation-based interaction between sarcopenia and metabolic syndrome. Finally, the authors point to melatonin as one of the components that may contribute to counteract this process, raising the need to include sleep in our focus of study.

To our knowledge, no other systematic reviews on this subject have been published, although the most similar may be the one proposed by Prokopidis et al.65 in 2021. In this document, the author suggests a relationship between sleep pattern disturbances and the risk of sarcopenia in conjunction with the risk of weight gain. Although it mentions the role of testosterone/cortisol, inflammatory markers, insulin resistance, and increased dopamine levels, it does not establish a conclusive effect.

Limitations and strengthsThe results of this work should be considered with caution, as this work has some limitations. One of the limitations of this review is that most of the studies included were of cross-sectional design, so it is impossible to establish causal relationships. In addition, the significant heterogeneity of the population samples and study methodology limited the generalization of the results.

Furthermore, and due to the lack of a clear common framework for the ‘metabolic syndrome,’ this review has considered the risk factors and different pathologies belonging to this syndrome,18 which appear in different proportions in the different samples, so in the search for more defined or homogeneous results it would be necessary to pre-establish a definition of this group of pathologies and consider populations with a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome as a whole.

However, this review also has important strengths. By considering other pathologies in addition to sarcopenia that are widely present in the older population, such as metabolic syndrome, we can obtain a more global vision of the interactions that can influence these individuals.

This review has shown the breadth of discrepancies and diagnostic range within these fields and the scarcity of articles covering all the study terms, thus opening a new avenue of study for the current multiple chronic–pathologic population.

ConclusionsDespite the numerous studies referring to the sleep-sarcopenia association, metabolic syndrome-sarcopenia relationship, and those, although fewer, relating to the sleep-metabolic syndrome association, no studies have been found that analyze the three vertices of this study triangle. From the articles analyzed, population samples and sources of data collection are very heterogeneous, so the results are also very heterogeneous. Studies with objective measurement tools, large samples, with a consensus diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, of advanced average age, and with an equal distribution of sexes are necessary to achieve standardization in the study methodology. The importance of the object of study lies in the morbidity of these two chronicities and in the importance of their prevention and knowledge of modifiable risk factors to improve these people's quality of life.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestsIrene de Frutos Galindo, Daniel Catalina Palomares, Paula Yubero García, Lorena Botella Juan, Daniela Vargas Caraballo Lockwood, Alba Marcos Delgado, Tania Fernández Villa declare no conflicts of interest or non-financial interests to disclose.