Against the backdrop of the profound adjustment of the global value chain, how technological spillovers from imported intermediate goods affect the heterogeneous innovation paths of firms is a core issue for developing countries. Based on the panel data covering 278 prefecture-level cities in China, this paper constructs micro-trade and spatial Durbin models to empirically examine the differential impacts of technological spillovers from imported intermediate goods on high- and low-technology innovation and their spatial effects. This study finds that (1) technological spillovers from imported intermediate goods significantly increase the high-technology innovation level of local firms, generating a 'technological dividend'. However, they have no significant effect on low-technology innovation, potentially triggering a 'low-end lock-in' effect. (2) Technological spillovers reduce innovation costs by enhancing regional absorptive capacity, where the import of semifinished products directly drives high-technology breakthroughs through product innovation, while the import of components indirectly optimizes innovation efficiency through process innovation. (3) The spatial spillover effect of high-technology innovation is significant, forming innovation clusters centred on the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas, while the regional collaborative effect of low-technology innovation is relatively weak. This research provides a theoretical basis for developing countries to balance import expansion and independent innovation. It suggests strengthening regional absorptive capacity and innovation ecosystem construction to avoid the risk of low-end lock-in and to achieve global value chain upgrading.

We note that export trade has been instrumental in fostering economic growth and sustainable development (Jahira et al., 2022), particularly in developing countries in the early stages of industrialization, due to the 'double gap' dilemma faced by these countries (Aglietta & Bai, 2012; Mei et al., 2020; Yülek & Santos, 2022). Import trade can lead to product substitution and industrial competition, which are often cited as reasons for trade protection. Imports are essential to promote economic development (Hongwei et al., 2023), as they bring technological spillovers to developing countries, helping them become productive and innovative (Kasahara & Rodrigue, 2008; Johnson & Noguera, 2017). The global economy has recently experienced economic stagnation due to several factors (Jones, 2023). As a result, global trade and investment are facing major challenges . Owing to vertical specialization, imported intermediate goods have become an essential component of global value chains and a crucial aspect of international trade for many countries (Lan esmann & Stöllinger, 2019; Antràs & Chor, 2022)—the structure of imported intermediates changes with the adjustment of the global value chain. Knowledge accessibility is a critical factor that can affect the innovative performance of firms, regions and countries, with intermediate imports serving as a primary channel for knowledge spillovers (Pietrobelli & Rabellotti, 2011; Kano et al., 2020).

Enterprises' innovation depends on the innovation input that occurs during this crucial economic transformation and development period. Moreover, importing intermediates from foreign markets can alter the proportion of factor inputs of local firms, regions, and countries, which can in turn affect regional innovative performance through technical externalization (Nishioka & Ripoll, 2012; Auboin et al., 2021).

Furthermore, at the core of this process lies the technological knowledge embedded in intermediate goods flowing across national borders. Despite imported intermediates in spurring nations and regions' innovations being applied in emerging developing countries, more information is needed to understand how to evaluate the technical spillover level from imported intermediates of nations and regions. It is necessary to assess whether they improve enterprises' innovation and affect neighbouring regions in order to comprehend the function of imported intermediates as vehicles for international technological spillovers. Whether importing intermediates improves regional innovation and affects neighbouring regions and how importing intermediates can influence the innovation paths of enterprises should be considered. Likewise, recent policy efforts lack theoretical foundations and unambiguous empirical evidence. The research into the relationship between imported intermediates and regional innovation would provide valuable insights into the technological innovation driving regional economic development. Such insights could also help nations and regions identify more specific roles in their policy frameworks for import trade, which is still one of the most crucial international trade policies for developing regional economies.

In recent years, there has been an increase in research investigating the impact of import intermediates on the economic development of nations. (Breisinger et al., 2019; Cimoli et al., 2020); however, only a few studies have specifically addressed the role of the technical spillover from imported intermediates in this context. These studies have focused on the effects of import intermediates, such as their impact on performance (Dhingra, 2013; Liu & Qiu, 2016), export scale (Feng et al., 2016), productivity, and innovation (Gilles et al., 2023), from the perspective of enterprises. Although the analyses of existing studies provide important evidence on the role of import intermediates in enterprise production, they seldom discuss the impact of import intermediates on different types of technological innovations and neighbouring regional enterprise innovations from a micro perspective.

This absence of knowledge can diminish import trade's significance in regional economic advancement. A thorough examination of the impact of imported intermediate goods on different types of technological innovations and neighbouring regional enterprise innovations can help comprehensively evaluate the role of imports in the global competitiveness of nations and regions. This is important to note, both in theory and in practice. However, few studies have examined the impact of the technical spillover from imported intermediates on different types of technological innovations and neighbouring regional enterprises' innovation from the integrity of micro and macro perspectives. This is due to the difficulty in obtaining data on the embedded technology of imported intermediates at the enterprise level. Therefore, our research aims to examine the abovementioned issues through theoretical and empirical analysis and explore the causal relationship between the technical spillover from imported intermediates and different types of technological innovations, including local and adjacent regions.

Compared with existing research, we make the following contributions. First, with respect to the research topic, our research adds dimensions to measuring the technological spillovers from imported intermediates. Previous studies usually employ the CH-weighted, LP-weighted, and NEW-weighted methods to assess the technological spillovers of imported intermediates and use the gross domestic product (GDP) of the technology-sourcing country, the research and development (R&D) capital stock and the importer's share of intermediates or the proportion of domestic imports at the city level as weights with which to calculate the technological spillovers from intermediates imported by cities. However, these approaches are relatively crude and cannot reflect the actual situation (Nishioka & Ripollet, 2012; Chen et al., 2017b). A key limitation of these methodologies is their reliance on macro-level data, such as GDP and the R&D capital stock of technology-sourcing countries. They adopt a unidimensional approach and lack the integration of micro-enterprise-level and meso‑city-level data, failing to accurately capture the complex process of actual technology transfer and absorption. This means that we have difficulty properly capturing the differences in the technological content of different types of intermediate goods and their actual spillover effects in different regions. This could lead to biased estimates of technological spillovers. This paper proposes a comprehensive data integration framework. Innovatively constructed, the model incorporates micro-enterprises and mega-cities in China and macro-data on exporting countries, facilitating systematic analyses. The first step involves identifying enterprise micro-imported intermediate goods data from the China Customs Database and the China Industrial Enterprise Database. The differential impact is captured by dividing imported intermediate goods into spare parts that indicate process innovation and semifinished products that facilitate product innovation. The second step involves using firms as the benchmark unit and adopting a composite measure that incorporates both the R&D capital stock and GDP of exporting countries to assess the quality of the technology source. By emphasizing the R&D capital stock relative to GDP, this approach more directly reflects the knowledge stock and innovation capacity of exporting countries, thus enhancing the accuracy of the technology level measurement. The third step in the process involves integrating enterprise and city data, with enterprise import data being disaggregated by city location to comprehensively reflect the level of technological spillovers of different imported intermediates at the regional level. This approach enhances the ability to detect regional heterogeneity in technological spillovers by integrating firm-level and city-level data, thus accounting for contextual variations, for example, between coastal regions typically characterized by higher innovation intensity and inland areas with weaker absorptive environments. The present approach to measurement is effective in addressing the issue of a lack of impact on different technologies and regions. This framework provides a more reliable empirical foundation for studying the technological spillovers effect of imported intermediate goods.

Second, the theoretical model is an essential supplement to existing research from the perspective of theoretical analysis, particularly in relation to the import trade mechanism and its impact on both high-tech and low-tech innovations. Prior studies on the relationship between import trade and innovation have employed empirical methods (Halpern et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017a; Antras et al., 2017). However, the number of analyses using theoretical methods remains very small. Antras et al. (2017) use a discrete choice model of multinational sourcing for heterogeneous firms, emphasizing the role of firm heterogeneity and decision-making in international trade. This study provides a theoretical explanation of how the technological spillovers of imported intermediates influence firm innovation. The present study combines Dhingra's (2013) competitive differentiation framework with Grossman and Helpman's (1993) theory of technological diffusion. It introduces a 'technological spillovers–product differentiation' transmission mechanism and examines the asymmetric impact of regional absorptive capacity on innovation costs. In doing so, it provides a new perspective on the “leapfrogging” feature of technological upgrading in developing countries.

Third, this paper investigates the heterogeneous innovation effect of imported intermediates from the perspective of spatial spillovers. Heterogeneous innovation theory was derived from Pavitt's (1984) classification of industry technology regimes. The theory reveals a divergence in industry technology tracks in which knowledge-intensive industries rely on breakthrough innovations, whereas traditional manufacturing is confined to incremental improvements. Global value chains have effectively extended the research boundaries, enabling developing countries to circumvent the constraints imposed by low-end lock-in through technological spillovers associated with imported intermediates (Lee & Malerba, 2017). However, excessive reliance on such spillovers can erode autonomous innovation capabilities (Archibugi & Pietrobelli, 2003). This study focuses on the 'dividend trap' double-sided effects of technological spillovers from imported intermediates and analyses their differential impacts on industries at different technological levels. This heterogeneous effect of inter-regional technological spillovers explains the polarization of technological innovation in developing countries—the co-existence of 'innovation breakthroughs' in high-technology industries and 'passive lock-in' in low-technology industries. The experience of China, which is a major importer of intermediates, can serve as a reference point for other emerging economies seeking to diversify beyond the 'import-backward-re-import' cycle. A joint fixed effects model and multiple spatial weight matrices are employed to assess the direct and spatial spillover effects of imported intermediate technological spillovers on the heterogeneous innovation of enterprises in China. Moreover, the formation of Chinese innovation clusters is explained.

We therefore test three hypotheses. Part a of the first hypothesis is that the technical spillover from imported intermediates in the local region drives the scale of high-tech innovation, leading to tech dividends. Part b of the first hypothesis is that the technical spillover from imported intermediates in the local region decreases the scale of low-tech innovation, leading to low-end traps. The second hypothesis is that the local region's technical spillover from imported intermediates improves enterprises' innovations by enhancing regional absorption capacity. The third hypothesis is that the technical spillover from imported intermediates improves enterprise innovations through process and product innovations. Several methodologies were adopted, namely the baseline by a panel fixed effects (FE) model, and the Bartik IV was used to check for endogeneity. The quantile regression approach was then used to measure the differences in the influence of technical spillover from imported intermediates on enterprise innovation across diverse high-tech and low-tech innovation levels. The final stage of the research process is to test for spatial effects and interregional spillovers via a spatial Durbin model (henceforth, SDM). The research framework is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The chosen setting for this study was China because it ranks as the world's largest importer, with total imports reaching US$ 2.6 trillion in 2023, of which intermediate imports constituted US$ 1.9 trillion. This paper uses a micro trade model to explore the theoretical effects of importing intermediates on enterprises' technological innovation. The study utilizes the panel data for 278 prefecture-level cities in China, with observation periods extending from 2000 to 2018; spatial correlation tests and descriptive analyses are conducted over the entire period (2000–2018), while regression analysis is applied explicitly from 2000 to 2013. This choice of methodology is based on data availability and a thorough review of the relevant literature.

Our findings underscore the positive role of intermediate imports in enterprises and regional innovation, which finds that the technical spillover from imported intermediates significantly boosts local enterprises' high-tech innovation, thereby benefiting adjacent regions. Further mechanism tests reveal that the import of intermediates could enhance enterprises' absorption, leading to a reduction in the cost of indigenous innovation. Process innovation and product innovation help enterprises increase their high-tech innovation. A phenomenon of innovation clusters can be observed, where the technological influence between adjacent regional high-tech innovations has a positive effect on each other. Overall, our research has significant policy implications.

The remainder of our research is structured as follows: Section 2 shows the theoretical framework and research hypotheses. Section 3 introduces factual characteristics and the empirical research strategy. In Section 4, the empirical results and exploration of the impact mechanism are reported. In the last section, we conclude our findings.

Theoretical model and research hypothesesDrawing on the theoretical model of Dhingra (2013), this section aims to integrate three critical dimensions—the level of technological spillovers from imported intermediates, the scale of high-tech innovation, and the scale of low-tech innovation—into a unified analytical framework that is informed by the principles of endogenous growth theory and the perspectives of new economic geography. The focus is on the impact of the level of technological spillovers from imported intermediates on the patterns of technological innovation of local and spatial associations (economic or geographic).it examines the intrinsic relationship between the level of technological spillovers and firms' innovation behaviour in the regions where the firms are located. In contrast, Dhingra (2013) focuses on the theoretical analysis of the impacts of firms' innovation patterns on social welfare and does not consider the spatial spillovers between firms' innovation behaviour and cities.

This work differs from that of Dhingra (2013) in the following ways. The first is the innovation in the model. We extend Dhingra's (2013) micro-decision model to analyse spatial proximity and heterogeneous innovation, revealing the dynamic effects of technological spillovers on regional innovation inequality. The second is the breakthrough in mechanisms. We propose the 'regional absorption capacity–innovation pathway differentiation' framework to explain the asymmetric effects of high- and low-technology innovations and the formation logic of spatial spillovers. The third is the policy implications. We provide empirical evidence for developing countries to achieve 'innovation upgrading' rather than 'low-end lock-in' by importing intermediate goods, emphasizing the importance of cross-regional technology sharing and innovation ecosystem development. In contrast, Dhingra (2013) focuses on the theoretical analysis of the impacts of firms' innovation patterns on social welfare and does not consider the spatial spillovers between innovation behaviour of firms and cities. The detailed analyses are presented below.

The technical spillover of imported intermediates and the enterprise's technology innovation choicesDemand methodologyThis paper integrates Dhingra's (2013) differentiation model with Grossman and Helpman's (1993) theory of technology diffusion, thereby developing a transmission mechanism termed “technological spillovers - product differentiation”. This mechanism is analyzed with respect to the level of technological spillovers from imported intermediate goods in the region where the firm is located, which influences the choice of innovation model.

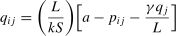

This model builds on Dhingra (2013) and assumes that the representative consumer demand function can be obtained by considering the case of product diversity as follows:

where qij represents the demand for variety i of brand j across all consumers, pij denotes the price of product i from enterprise j, and qj=∫qijdi(qj=hqij) represents the total consumption of all products from enterprise j. L represents the total number of consumers in the market. a indicates the benchmark demand quantity. It accounts for factors such as consumers' income levels, preferences and population size. δ and γ are positive. δ denotes differentiation among varieties, which affects the degree of competition among different varieties within the same brand. δ is negatively correlated with qij. The larger the value of δ is, the more significant the inhibitory effect of increased consumption on prices. γ denotes differentiation between brands, which affects the degree of competition among different brands. γ is negatively correlated with qij. The larger the value of γ is, the greater the increase in the total consumption of all varieties under the same brand, which significantly lowers prices. That is, an excessive supply of a certain brand will lead to the depreciation of the brand. When γ=0, there is no brand difference; the larger the value of γ is, the greater the brand loyalty.Using firm-level evidence from Uruguay, Zaclicever and Pellandra (2018) find that imported intermediate inputs contribute to productivity growth through technological spillovers, emphasizing the role of technology transfer and product differentiation in empirical research. The improvement in the level of technological spillovers from imported intermediates in a region (S) has a significant promoting effect on the innovation behaviour of enterprises and the degree of differentiation of firms' products, which is denoted by δ. This positive correlation can be expressed by the parameter changes in the model, that is, ∂δ/∂S>0. Regions with higher levels of technological spillovers of imported intermediates (represented by SHts) usually have more advanced innovation environments and more effective knowledge-sharing spaces (Grossman & Helpman, 1993; Keller, 2004). Furthermore, the degree of product differentiation among firms (δ) is positively correlated with the level of technological spillovers of imported intermediates in a region (SHts). In the region, innovative firms are more closely connected to the technological linkages embedded in imported intermediates, whether spatial or economic. As a result, firms located in the region can produce high-tech products that are more efficient and can better meet consumer needs, leading to greater product differentiation and lower product substitutability (Antràs & Yeaple, 2014; Boehm & Oberfield, 2020). In contrast, regions with lower levels of technological spillovers (SLts) from imported intermediates tend to be situated in general innovation environments with less-developed knowledge-sharing networks. These regions are more distant from the embedded technological linkages of imported intermediates, and the products produced by firms in these regions tend to exhibit less differentiation and, thus, greater substitutability (Bloom et al., 2013; Alfaro & Chor, 2023). The differentiation of firms' products, which is denoted by δ, is related to the level of technological spillovers from imported intermediates in a region (SLts). Therefore, the greater the technological spillovers from imported intermediates in the region (SLts) is, the greater the degree of product differentiation (δ). For convenience, in the following, parameter δ is expressed in terms of the level of technological spillovers from imported intermediates in a region, which is denoted as S. We assume that δ=kS. Then, we can include the level of technological spillovers from imported intermediates in the region (S) in the consumer demand function:

Enterprise production under technical spilloversThis model assumes that the substitutability of products is influenced by the technical spillovers from imported intermediates used by production firms. When a firm benefits from greater technical spillovers through imported materials, its overall productivity increases, leading to lower product substitutability. Dhingra (2013) argues that firms in an open economy could import intermediate inputs. Therefore, enterprises should determine the optimal quantity to produce, develop new products and optimize the production process to make informed decisions.

Extending Dhingra's (2013) model of firms' optimal decision-making, this paper argues that the technological spillovers of importing intermediates lead to changes in firms' decision-making behaviours. First, firms may adjust their optimal output due to changes in costs brought by these technological spillovers. Imported intermediates often lead to cost savings by integrating advanced technologies and practices. These savings prompt firms to reassess and adjust their production levels (Behera, 2015; Newman et al., 2015). Second, firms associated with imported intermediates upgrade their production processes. These spillovers provide firms with access to a broader range of innovations, enabling them to adopt both high-tech and low-tech solutions, which in turn allow firms to streamline operations, improve their efficiency, and produce new supporting products that complement their existing offerings (Bhattacharya et al., 2021; Özbuğday & Waqar, 2024). These innovations and optimizations lay the groundwork for the development of new products. Additionally, firms that utilize imported intermediates are likely to expand their product lines through high-tech innovation. By adopting advanced technologies, firms can better meet evolving market demands, diversify their offerings, and strengthen their competitive position. As more firms within an industry engage in these continuous cycles of innovation and optimization, the cumulative effect leads to broader industry advancements, thus improving overall productivity and accelerating technological progress across the sector (Song et al., 2022; Carrasco & Tovar- García, 2021).

The firm can either make a product at unit cost c or choose a lower unit cost c(ω) by investing in low-tech innovation ω, ω for the low-tech innovation scale [0, 1]; this is a function of diminishing marginal returns. The firm j can either make product i at unit cost c or choose a lower unit cost c(ω) by investing in low-tech innovation ω, whichcan be expressed as follows:

For firms investing in low-tech innovation, the unit cost decreases with the amount of investment, represented by rω, which is the cost per unit of low-tech innovation. On the other hand, firms can also invest in high-tech innovation, represented by the scale h, with a corresponding cost per unit rh. In addition to these innovation costs, there is an initial cost f associated with entering a new market. Following the importation of intermediates, the impact of technological spillovers on market profits can be expressed as follows:

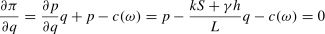

where p is the average market price of the production product, and q is the optimal output. rω represents the low-tech innovation cost per unit, h represents the scale of high-tech innovation, rh represents the cost of high-tech innovation per unit, f represents the initial cost of entry into the new market, and π represents the profit value added of the enterprise after importing intermediates.In a state of market equilibrium, the behaviours of consumers and firms must be optimal. Technological innovation (which includes both high-tech and low-tech companies) exerts a significant influence on market equilibrium. High-tech innovation frequently precipitates substantial shifts in market dynamics due to its transformative nature, and innovations in low technology are also imperative for continuous improvement and cost-effectiveness despite the less dramatic nature of such innovations. A diversity of products and services will benefit consumers, and firms can strategically allocate their resources to optimize productivity and growth in a balanced market. So, the attainment of market equilibrium is contingent on the optimal behaviour of all market participants, which is propelled by the synergy of both types of technological innovation.

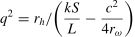

The profit function is a first-order condition with respect to the size of high-tech innovations (Eq. (6)). The optimal high-tech innovation scale can be obtained with the profit of the new product π equal to the decrease in the profit of the existing product due to the introduction of the high-tech product h(γqL)q. In other words, firms will adjust the range of high-tech products until the cannibalization effect completely cancels out the profit of the marginal product. As a result, the size of firms' high-tech innovations is shown in Eq. (7).

The scale of low-tech innovation can be expressed as follows:

Innovation choices under technical spilloversTechnological spillovers from imported intermediate goods can influence firms' decision-making behaviour, thereby enabling them to produce a wider variety of differentiated products at reduced costs and to increase the efficiency of high-tech innovation. In instances where spillovers are substantial, firms tend to favour high-technology innovations and, conversely, to reduce low-technology innovations that rely on incremental improvements and cost reductions.

According to Eq. (7) and Eq. (8), the high-tech innovation scale and the low-tech innovation scale of an enterprise, which are effect functions of the technical spillovers from imported intermediates in the region, can be written as follows:

For a detailed derivation of the push-to-talk logic for the core assumptions of this paper, see Appendix A. According to Eq. (9), we obtain Hypothesis 1a:

Hypothesis 1a The technical spillover of imported intermediates in the local region drives the scale of high-tech innovation, creating technical dividends.

High-tech innovation can yield high returns and competitive advantages but it requires significant investment and long-term commitment. These imported intermediates bring about advanced technologies and practice that local enterprises can adopt, resulting in significant technical spillovers (Xie & Wang, 2022). The technological spillovers effect of imported intermediates has a considerable effect on the high-technology innovation behaviour of enterprises (Huang & Pei, 2022). Local enterprises' absorption of advanced technologies provides a foundation for increased R&D investment, innovation and transformation in response to local demand (Kinoshita, 1997). This enables the rapid development of high-tech products with strong market competitiveness. Concurrently, technology diffusion encourages enterprises to enhance employee training, refine competencies and expedite the integration of novel technologies (Chun-Chien & Chih, 2008). In addition, technological spillovers promote collaboration between firms and research institutions and their own partners, facilitating knowledge exchange and collaborative innovation (Bekkers & Freitas, 2008). Through these mechanisms, technological spillovers have contributed to the sustained growth of high-tech achievements in the region. Eq. (9) indicates that the technical spillovers of imported intermediates in a region can boost high-tech innovation for enterprises. The scale of high-tech innovation increases with the technical spillover level of imported intermediates in the region, resulting in a 'technology dividend' (Song et al., 2022).

In addition, Eq. (10) shows that the technical spillovers from imported intermediates in the region where the enterprise is situated may reduce the scale of low-tech innovation for enterprises. Therefore, we can also obtain the following:

Hypothesis 1b The technical spillover of imported intermediates in the local region decreases the scale of the low-tech innovation region, forming a low-end lock.

Low-technology innovation is one of the innovation behaviours selected by enterprises. Hypothesis 1b shows that the enhanced spillover effect of imported intermediate goods will encourage local and spatially related enterprises to be more willing to adopt high-technology level innovation and to extrude the scale of low-technology innovation. That is the 'low-end lock-in effect.' The explanation for this phenomenon is that technological spillovers significantly increase enterprises' technological level and production capacity. Incremental improvements are no longer a clear competitive advantage (Hervas-Oliver et al., 2012; Zhong, 2017). In other words, the diffusion of new technologies requires firms to reallocate resources from incremental process improvements and product optimization and put them toward the adaptation and integration of new technologies.

In this process, the role of aggregation effects is of particular importance. Sher and Yang's (2005) research found a significant relationship between firms' innovativeness and performance and emphasized the role of industrial clusters for knowledge diffusion. This finding could indirectly support the present study that imported intermediates may enhance high-technology innovation while weakening the competitiveness of low-technology innovation under a similar knowledge diffusion mechanism. Hervas-Oliver et al. (2012) suggests that introducing external technologies alters firms' innovation priorities, with incremental innovation activities gradually being superseded by innovation behaviours more reliant on high technology. So, the imported technological spillovers not only enhance the overall productivity of firms but also undermine the effectiveness of incremental innovation by accelerating technology diffusion (Wang, 2021). While this model assumes stable consumer preferences and the significant influence of product diversity, variations in industry-specific conditions may provide opportunities for further refinement and application of the model.

In summary, introducing imported intermediates exposes firms to the advanced knowledge and processes embedded in them through technological spillovers (s), and they then acquire this knowledge and these processes. Under the premise of specific absorptive capacity and learning effects, these spillovers can effectively reduce the entry threshold of high-technology innovation, improve innovation efficiency, and simultaneously change the substitutability of products and enhance differentiated competitiveness. Therefore, enterprises reconfigure their innovation resources and invest more resources in high-technology fields, which ultimately manifests in an increase in the scale of high-technology innovation (∂h∂S>0) and a corresponding decrease in low-technology innovation (∂w∂S<0), resulting in a structural change in the transition to high-quality innovation. For example, in the transformation and upgrading of China's manufacturing industry, the technological spillovers effect of imported intermediate goods plays an important role in promoting high-technology innovation and suppressing low-technology path dependence. Taking China's automobile industry as an example, since the 1980s, a large number of high-precision engine parts and electronic control systems were imported. Thus, local enterprises, through the depth of their cooperation with international parts giants such as Bosch and DENSO, have gradually absorbed electronic fuel injection, turbocharging and other key technologies. Initially, decades of accumulation were needed to break through the engine technology threshold; through the technological spillovers effect, BYD, Geely, and other enterprises took only 5 to 8 years to achieve a rapid catch-up. In this process, enterprises have reallocated resources originally invested in improving traditional mechanical processing to new energy, intelligent driving and other high-tech directions, resulting in an average annual growth of 30 % in patents related to new-energy vehicles and a significant reduction in investment in low-tech improvements. Similarly, in the electronics and information industry, Huawei quickly absorbed advanced communications technologies by importing high-end chips and optical devices in the early days, and through in-depth cooperation with international suppliers, it shifted from catching up to leading. With the help of these technological spillovers, Huawei's 5 G technology development efficiency far exceeds the traditional 'starting from scratch' path, overcoming the core technology barriers and driving the entire industry towards high-end evolution. At the same time, Huawei has taken the initiative to withdraw from the low-end OEM market and to focus on high-tech innovation, effectively avoiding the low-end lock-in trap. The cases above show that imported intermediates not only enhance innovation efficiency and capability of enterprises but also prompt the reorganization of enterprise resources in the direction of high technology, thus expanding the scale of high-tech innovation and weakening low-tech path dependence.

The technical spillover of imported intermediates and the regional research absorption capacityThe concept of absorptive capacity was initially proposed by Cohen and Levinthal (1990), emphasizing the ability of firms to digest external knowledge through internal R&D. This concept was later extended to the regional level, which focused on the overall innovation ecosystem of the region (Grillitsch and Nilsson, 2015; Miroshnychenko et al., 2021). In this paper, however, we propose a novel definition of regional absorptive capacity as 'the comprehensive ability of regional enterprises to identify, absorb, transform, and apply the technological knowledge carried by imported intermediaries.' To this end, we construct a measure through the interaction term between the ratio of R&D expenditures to GDP and the number of scientific researchers in the city, emphasizing the structural matching of the knowledge carriers with the technology carriers.

The increase in technical spillover from imported intermediates can facilitate the diffusion and absorption of technology among “related industries”, “agglomerated industries”, and “upstream and downstream enterprises” (Gries et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2022). This, in turn, fosters a “learning effect” (Audretsch & Feldman, 1996) within the local and spatially connected regions that could strengthen the regional absorption capacity and reduce the cost of high-tech innovation. So, it enhances the overall technological environment and facilitates the absorption and application of new knowledge, thereby enabling more efficient innovation. In addition to traditional perspectives on innovation classification, recent years have seen increasing attention on green innovation as a distinct type of innovation. Huang et al. (2023) indicates that the impact of technological spillovers on different types of innovation exhibits significant differentiation mechanisms and that technological spillovers not only affect the quantity and quality of innovation but also influence the direction and environmental orientation of innovation. The study finds that the technological spillovers from imported intermediate products has a dual effect on green innovation. The introduction of advanced technology can enhance the environmental and technological capabilities of enterprises and this spillover effect is closely related to the strength of regional environmental regulations and the absorptive capacity of innovative entities. This finding expands our theoretical perspective on innovation types and suggests that we should also consider the environmental attributes and sustainable development orientation of innovations, thereby construct a more comprehensive innovation evaluation framework when analyze high- and low-tech innovations.

Government initiatives such as guiding clustering through industrial policy, improving infrastructure to reduce the cost of inter-firm collaboration, and accelerating the diffusion of knowledge through the mobility of talent facilitate the formation of innovation clusters. The technological spillovers of imported intermediate products promote the dissemination and absorption of technology between related industries, cluster industries, and upstream and downstream enterprises. This interconnection promotes local learning effects and extends to spatially connected areas, ultimately reducing the cost of high-tech innovation and gradually abandoning firms' investment in low-tech innovations.

First, the technological spillovers of imported intermediate products can promote coordinated development between upstream and downstream enterprises (Huang & Pei, 2022). Upstream suppliers help downstream enterprises improve product quality and production efficiency by providing high-tech intermediate products. In turn, downstream enterprises' demand and feedback promote the technological innovation of upstream suppliers. This two-way interaction forms a virtuous circle and promotes technological progress throughout the supply chain. As the scale of high-technology innovation increases, the marginal benefits of low-technology innovation gradually diminish. As high-technology innovation in a region absorbs a substantial amount of human capital and capital, the competitive advantage of low-technology innovation is reduced, thereby further decreasing enterprises' investment in low- technology innovation (Deeds & Hill, 1996; Haschka & Herwartz, 2020).

Second, the technological spillovers of the advanced technology of imported intermediate products is not limited to a single enterprise but fosters collaboration and knowledge-sharing across the entire industrial cluster (Porto et al., 2021). This cluster effect is particularly obvious, especially in geographically adjacent industrial clusters, and it improves the overall technological capabilities of the region. In regions with absorptive solid capacity, firms reallocate resources from low-technology innovation to high-technology innovation. Technological spillovers create opportunities for high-technology innovation, increasing firms' reliance on high-technology products and gradually reducing investment in low-technology innovation (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Oh, 2017).

Third, technological spillovers stimulate learning effects, reducing innovation costs and gradually emerge as technology spreads in related industries and clusters. Enterprises can achieve technological upgrades and innovations at a reduced cost by observing and emulating others' successful practices for reducing the cost of the R&D process and accelerating the application and popularisation of new technologies. Due to the expansion of high-technology products in the market, consumer demand has gradually shifted from low-technology products to high-technology products. In response to shifts in market demand, companies have become less dependent on low-technology products and innovations. This has led to an intensification of the low-end lock-in effect (Safarzynska & Bergh, 2010). Technology diffusion through imported intermediate products enhances regional absorption capacity, reducing obstacles to high-tech innovation. It can achieve higher efficiency and innovation at lower costs that companies and industries within and across regions learn from each other. This process strengthens local industries and promotes broader regional economic development.

Industrial policies and infrastructure construction promote the development of innovation clusters. Talent mobility promotes knowledge sharing in innovation clusters. The government has attracted the concentration of high-tech enterprises by providing tax incentives, research subsidies and other policies. At the same time, it has invested in the construction of science and technology parks and innovation incubators to provide enterprises with R&D office space and shared experimental equipment, lowering the cost of innovation and promoting exchanges and cooperation among enterprises. Improving transportation and communication facilities reduces the cost of logistics and information exchange among enterprises and promotes the dissemination of knowledge and technology. Public service facilities such as education and medical care attract high-quality talents and protect innovation. Talent attraction policies bring together outstanding talents, bringing rich human resources and advanced technological knowledge. Enhance regional absorption and innovation capacity.

On the basis of the above discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 Regional absorption capacity is a significant mechanism through which the technical spillover from imported intermediates can improve high-tech innovation and reduce low-tech innovation.

The import of intermediates primarily composed of parts and components and semifinished products has significantly influenced firms' innovative activities, particularly regarding the advancement of process and product innovation. The immediate impact of companies' import of spare parts is the advancement of production processes. Enterprise process innovations arise from local technological spillovers provided by imported spare parts because they often contain advanced technologies and practices and can offer better performance and durability, leading to more efficient operations and cost savings than local alternatives. Therefore, process innovations directly result from enhanced technology, which results in the incorporation of imported components. Given that imported spare parts have been demonstrated to foster process innovation, it is vital to investigate how such innovations stimulate high-tech and low-tech developments within firms.

Introducing imported spare parts stimulates process innovations by providing local enterprises access to advanced technologies that may be unavailable (Bertschek, 1995; Hu et al., 2018). Working with these advanced spare parts facilitates the transfer of knowledge and skills from international suppliers to local enterprises which enhancing the technical expertise of the workforce and improving the innovation capacity of enterprises (Chen et al., 2017a). Furthermore, introducing new and advanced spare parts stimulates research and development efforts for teams work to integrate and optimize these components within existing processes (Hu et al., 2018; Sgarbossa et al., 2021). Enterprise process innovations drive high-tech innovations by introducing new technologies and encouraging advanced research and development. Simultaneously, low-tech innovations are promoted to make existing methods and techniques more efficient and effective.

First, process innovations within firms contribute significantly to low-technology innovation. When firms import spare parts and components, local technological spillovers can improve production processes, streamline production and operational workflows, reduce the cost of incremental innovation, and promote low-technology innovation (Bekes & Harasztosi, 2019). This process shows that low-tech innovation benefits from improvements in the production process that allow firms to refine their current offerings and maintain competitiveness in cost-sensitive markets.

Second, companies enhance their productivity and product quality by optimizing processes. These improvements establish a robust foundation for high-tech innovation. By conducting in-depth analysis and learning from advanced imported spare parts technologies, enterprises can localize and re-innovate their technological knowledge, accelerating technological progress and driving the development of the entire industry (Ismanu et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022). Process innovations form the foundation for R&D and help firms explore advanced solutions to meet market demands. Knowledge management and dissemination foster collaboration and innovation. The propagation of knowledge within an enterprise establishes innovation networks, accelerating the development of advanced solutions. In this sense, process innovations have a dual effect; they not only optimize current operations but also enable firms to leverage advanced technologies for high-tech breakthroughs. The benefits of corporate process innovation extend beyond the individual enterprise, influencing the innovation ecosystem of the entire high-tech industry through supply chains, partners, and market mechanisms (Wang et al., 2021). Both high-tech and low-tech sectors can benefit when the impact of imported spare parts on innovation is considered. Low-technology innovations may be more affected than high-technology innovations by imported spare parts because high-technology innovations require more complex research and development processes, but low-technology innovations focus on process optimization and cost efficiency, which can be directly improved by integrating advanced spare parts.

On the basis of the above discussion, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3a The enterprise's process innovations, as revealed by local technological spillovers from imported spare parts, enhance low-tech innovations.

Enterprises import semifinished products, which are then subjected to a series of processes, including assembly, improvement and expansion of functionality, as well as design optimization, to meet specific market demands. By increasing the value of these imported components, enterprises can produce competitive finished products for the market. These steps represent complete product innovation, including high-tech and low-tech innovation. With semifinished products enhancing the value chain, firms are positioned to realize further product quality and innovation advancements, which manifest in various ways, including reduced defects and improved profitability (Karmakar et al., 2023). On the one hand, introducing high-quality semifinished products reduces defects in the production process, lowers product returns, and reduces waste and associated costs. Firms can capitalize on economies of scale to cut costs and improve profitability. This cost-effectiveness is critical for driving firms to invest in high-technology innovations, which often require more excellent R&D investment and greater risk-taking. On the other hand, importing high-quality semifinished products provides valuable learning opportunities for employees, whose skills and expertise are improved and whose technological proficiency is derived within the company (Psarommatis et al., 2021). Therefore, imported semifinished products of the highest quality often utilize the latest technologies and innovations, which provide the basis for developing advanced products and enhancing technological integration, particularly with respect to high-technology products. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

Hypothesis 3b An enterprise's product innovations, as revealed by local technological spillovers from imported semifinished goods, enhance high-tech innovations.

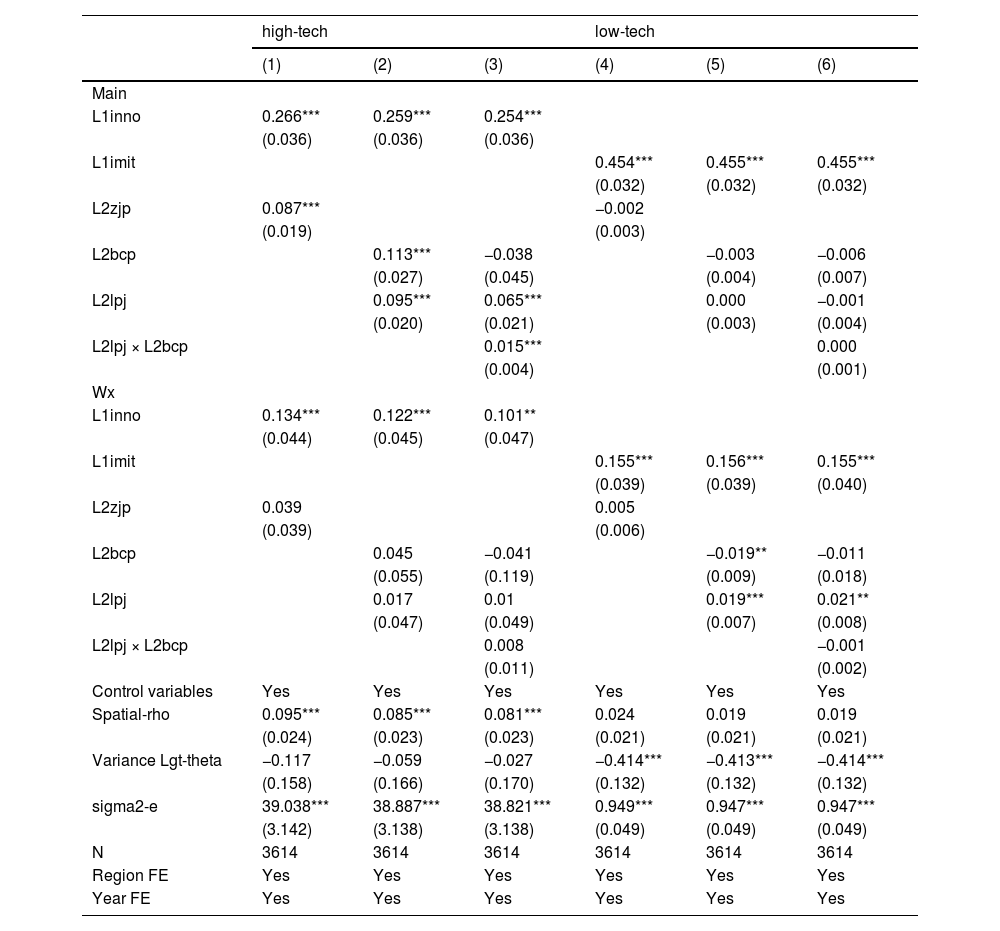

The following empirical studies could examine the impact of differences in technological advancement across industries or regions between high-tech and low-tech innovations. The basic regression finds that in an environment of technological spillovers, firms tend to prioritize investment in high-technology innovations, leading to a gradual decline in low-technology innovation inputs. Process innovation and product innovation are identified as the primary drivers of high-technology innovation; however, their impact on low-technology innovation exhibits contrasting trends and is statistically less significant. Empirical analysis of spatial measurement reveals that high-technology innovation and low-technology innovation exhibit divergent spatial diffusion patterns. Specifically, high-technology innovation demonstrates stronger spatial dependence, while low-technology innovation is hindered by technological siphoning from spatially related regions.

Data, variable construction, and empirical estimation strategyThis section provides an overview of the data, variable construction, and empirical estimation strategy employed in our study.

Data on technological innovationThis study utilizes panel data from the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database and Patent Database, covering the period from 2000 to 2013, in order to provide a more comprehensive analysis of regional high-tech and low-tech innovation capabilities. It thus moves from the analysis of patents to a more extensive examination of innovation capabilities. We primarily use invention patents as a proxy for a region's ability to achieve high-tech innovation levels, as they generally signify significant technological advancements and innovation. In contrast, design and utility model patents serve as a proxy for low-tech innovation levels because of their lower technological complexity. Additionally, the number of these patents elucidates innovation performance within specific industries, such as consumer goods and design.

The regional patents extracted from the Chinese Patent Database represent the data on technological innovation capabilities. Our final sample consists of 287 regions in China over the 2004–2018 period. We use this metric to reflect a region's overall level of technological innovation. A higher patent count typically indicates more significant innovation activity. This study employs the mean values of urban technological innovation capabilities during the sample period to construct a spatial trend map (Fig. 2) via ArcGIS 10.8 software. This map visually delineates the spatial distribution trends of urban technological innovation capabilities in China and the variable Z represents the attribute values of urban technological innovation, with the X-axis indicating the eastward direction and the Y-axis indicating the northward direction. From 2004 to 2018, the focus of China's urban technological innovation capabilities was primarily in the southeast, while there was a notable absence of similar development in the northwest. Precisely, the trend surface displays a “U-shaped” pattern that increases progressively from west to east in the east-west direction. In contrast, a curve that rises from north to south with a gradually diminishing slope is shown in the north-south direction.

Data on technical spillover from imported intermediatesTo evaluate the impact of imported intermediates on innovation across high-tech and low-tech sectors, this study examines their technical spillover within a specific region (designated i) at a given time point (t). This approach is informed by relevant literature discussing the emergence of innovative activities (Kwark & Shyn, 2006; Mazzi & Foster-McGregor, 2021; Cefis et al., 2023).

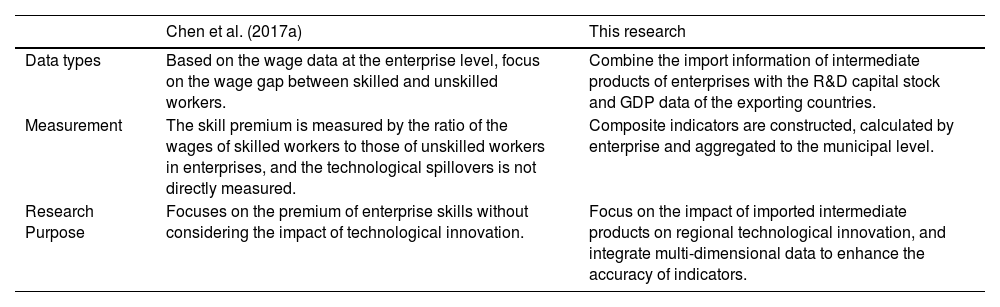

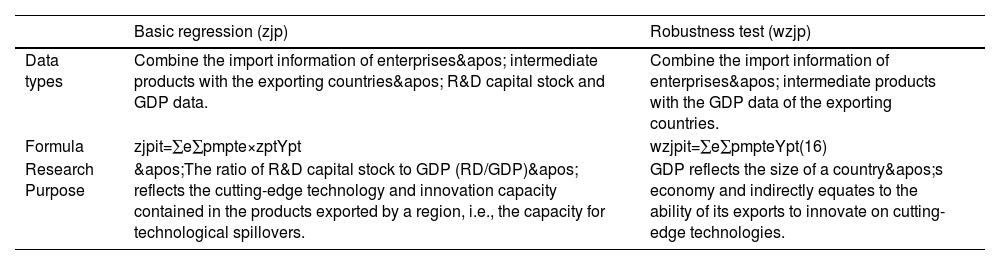

The technological spillovers measurement method in this paper has significant differences at the data integration level compared with the research of Chen et al. (2017a) (Table 1).

Comparison of measurement methods for technological spillovers.

| Chen et al. (2017a) | This research | |

|---|---|---|

| Data types | Based on the wage data at the enterprise level, focus on the wage gap between skilled and unskilled workers. | Combine the import information of intermediate products of enterprises with the R&D capital stock and GDP data of the exporting countries. |

| Measurement | The skill premium is measured by the ratio of the wages of skilled workers to those of unskilled workers in enterprises, and the technological spillovers is not directly measured. | Composite indicators are constructed, calculated by enterprise and aggregated to the municipal level. |

| Research Purpose | Focuses on the premium of enterprise skills without considering the impact of technological innovation. | Focus on the impact of imported intermediate products on regional technological innovation, and integrate multi-dimensional data to enhance the accuracy of indicators. |

This paper integrates multi-level data from enterprises, cities and exporting countries to construct more accurate indicators of technological spillovers, which is in line with the research topic and provides strong support for analyzing the impact of imported intermediate products on regional technological innovation.

This quantification is achieved through a rigorous analytical framework that integrates corporate dimensions, utilizing data from the combined data of the Chinese industrial enterprise database, customs trade database, World Bank database, and China City Statistical Yearbook to ascertain import weights at the enterprise level:

Where mpte represents the quantity of intermediates imported by firm e in region i from country p during period t. zpt represents the domestic R&D capital stock in country p during period t. Ypt represents the GDP of country p during period t. zpt/Ypt represents the proportion of a region's investment in R&D to its GDP, and is used to measure the quality of technology sources in exporting countries.This ratio provides a more accurate measure of the potential intensity of technological spillovers. When a region has a large R&D capital stock relative to its economic size, this indicates that it has invested more in R&D and that its potential for technological spillovers is greater. However, if the economic size (GDP) of a region is large, the intensity of its R&D (R&D/GDP) may not be noteworthy, even if the absolute value of its R&D capital stock is high. This is an important indicator representing the degree of emphasis and investment in technological innovation and R&D activities made by export regions. This calculation method enables the technological spillovers indicator to consider both the R&D investment (zpt) and the economic scale (Ypt) of the exporting country simultaneously, thus reflecting the technological spillovers level of imported intermediate goods more comprehensively. Firms' R&D expenditures not only yield private returns but also increase the productivity of other firms by generating positive externalities. Lucking et al. (2019) empirically identify these 'non-market returns,' demonstrating that R&D activities produce significant technological spillovers within the broader economy. Building on this idea, Tsai and Wang (2004), using data from Taiwan's manufacturing sector, find a significant positive correlation between the R&D intensity of high-tech industries and productivity improvements in traditional manufacturing sectors, highlighting the presence of inter-industry spillover effects. Furthermore, through a spatial econometric analysis of China's high-tech industries, Zhang and Liu (2018) show that regional differences in R&D intensity have a significant impact on knowledge spillovers, with local spillover effects being notably stronger than inter-regional effects. Collectively, these studies underscore the broad applicability and explanatory power of R&D intensity as a proxy for technological spillovers across different national and industrial contexts.

To objectively describe changes in the technical spillover from imported intermediates, we have created a local LISA agglomeration diagram for China's provincial technical spillover from imported intermediates in 2005, 2008, and 2018 (Fig. 3). The technological spillovers of intermediates in China are concentrated in a few provinces, and these provinces show spatial dependence in geographical space. There are three innovation circles, namely, the Yangtze River Delta, with Shanghai at its core; the Pearl River Delta, with Guangdong at its core; and the Bohai Rim, with Beijing at its core.

The spillover characteristics of intermediates exhibit notable spatial agglomeration. In the period under review, the regions presented high-high (HH), low-high (LH), low-low (LL), and high-low (HL) agglomerations. From 2005 to 2018, eastern coastal areas exhibited dominant HH aggregation; this means they could fully absorb technological spillovers from imported intermediates, thereby fostering collaborative innovation development in the surrounding regions.

From 2005 to 2008, Northwest China experienced a significant transformation that shifted from high-low agglomeration to low-low agglomeration, indicating that similar regions increasingly surround low-innovation areas. Similarly, areas in the middle reaches of the Yellow River and Northeast China transitioned into predominantly low-low agglomeration areas, indicating a decline in specific regions' innovation capacity. From 2008 to 2018, technological spillovers from the Circum–Bohai Sea region notably influenced the northeast region. The Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas regions positively influenced Central China and parts of Southwest China and Northwest China. However, regions such as Shanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Xinjiang presented weak innovation capabilities, reflecting low-low agglomeration characteristics.

Data on regional absorption capacityTo test Hypothesis 2 (see Section 2.1), we measure regional absorption capabilities on the basis of the interaction between the natural logarithm of the proportion of R&D expenditure in GDP and the natural logarithm of the number of city researchers. This is calculated as follows:

where lngovit represents the natural logarithm of the proportion of R&D expenditures in GDP in region i during period t. lnrd_presonit represents the natural logarithm of the number of city researchers in region i during period t.Cities with higher absorptive capacity can facilitate the formation of “industrial linkages” and “industrial agglomerations” and then accelerate the diffusion and absorption of technology among local enterprises and their upstream and downstream counterparts. Regional absorption capacity, in turn, fosters the emergence of a “talent dividend” and “learning effects” within the local area (and spatially related regions), which serve to reduce the costs associated with imitative innovation. Consequently, enhancing technological absorption of city is instrumental in expanding the scale of high-tech and low-tech innovation.

Data on process innovation and product innovationThe data on the technical spillover from spare parts and the technical spillover from semifinished products are the same as the data on the technical spillover from imported intermediates extracted from the combined data of the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database, Patent Database, Customs and Trade Database, and China City Statistical Yearbook.

Import of spare parts and semifinished products plays a significant role in representing different types of innovation within a region. Spare parts are imported primarily to complement and integrate with existing production equipment that leads to process innovation which can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of production processes and enhance local indigenous innovation. Additionally, the technological spillovers of import spare parts can indirectly stimulate innovation in neighbouring regions through interconnected industry chains, creating a spillover effect that promotes regional innovation clusters (Hudson, 2002; Koren, 2010). Importing semifinished products is often aimed at further processing and eventual sales, which are directly related to product innovation. This is done by investing in innovation to increase the value and competitiveness of their offerings (Fedyunina & Averyanova, 2019). Similarly, the technological spillovers of imported semifinished products can indirectly influence the innovation capabilities of adjacent regions by leveraging value and innovation chains which could potentially leading to a broader regional innovation ecosystem (MacPherson, 1994).

In summary, the import of spare parts is a catalyst for process innovation, and the import of semifinished products represents a pathway for product innovation.

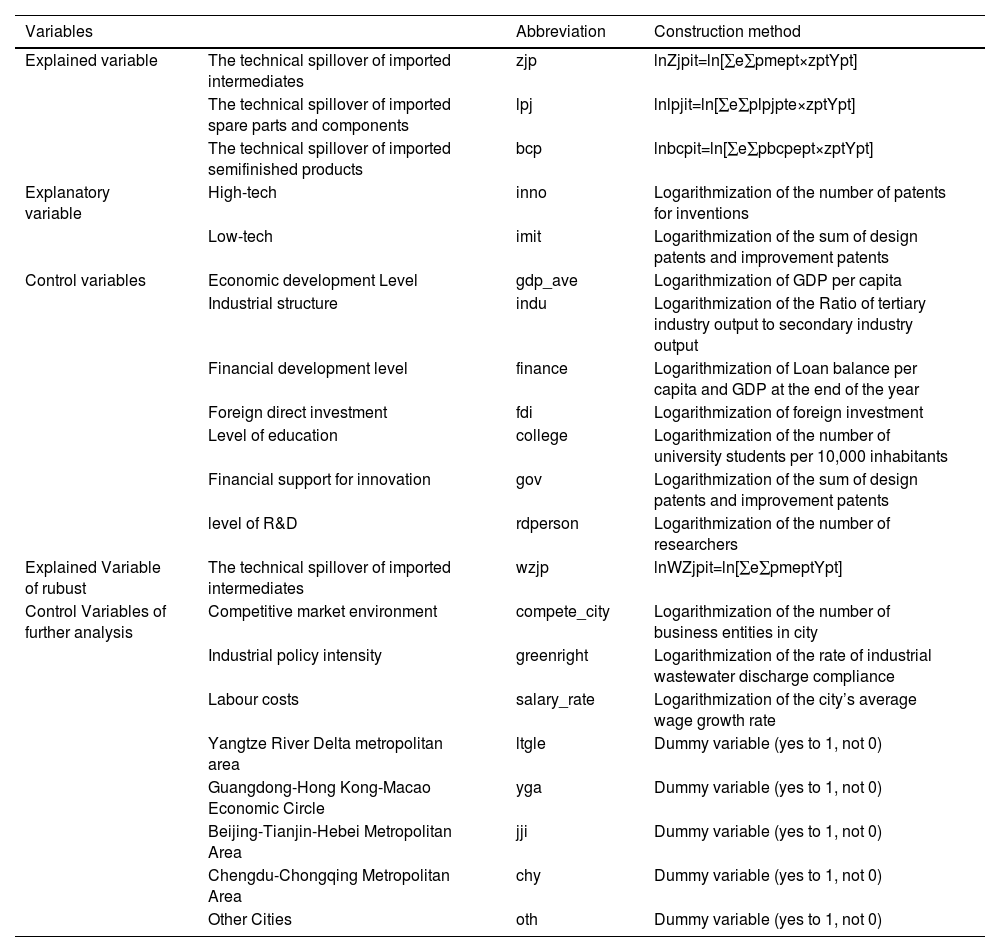

Control variablesTo mitigate to the greatest extent possible the problem of omitting important variables, which may bias the causal inference of the model, we selected the following control variables based on the research perspectives of existing studies: the economic development level, the industrial structure, the financial development level, foreign direct investment, the level of education, financial support for innovation, and the level of research and development (R&D). We use the recalculated explanatory variables (lnwzjp) from the previous literature for robustness testing. Moreover, we add the following control variables in further analyses: the competitive market environment, industrial policy intensity, and labour costs. The definitions of the variables and the descriptive statistical results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Definition of variables.

Descriptive statistical results.

This paper aims to measure the effects of technological spillovers from imported intermediates, imported intermediate innovation performance, and spatial proximity on innovation performance in high-tech and low-tech sectors. Given that the spillover effects of imported intermediates often exhibit a time lag—particularly as the impact of components and semifinished products on firms’ innovation capabilities tends to be gradual and cumulative—we fully incorporate this dynamic process into our empirical model. Accordingly, we use two-period lagged measures of overall technological spillovers from imported intermediates, as well as the specific spillover levels of components and semifinished products, as the core explanatory variables.

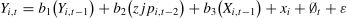

Our estimation strategy relies on the different complementary steps described in this section. Using Eq. (13), where high-tech and low-tech patents within manufacturing measure innovation performance, we investigate the influence of the technical spillovers of imported intermediates (zjpi,t−2) on these two distinct technological sectors, considering them as the dependent variables in our analysis. Then, we progressively include other controls to refine the analysis. The starting equation is as follows:

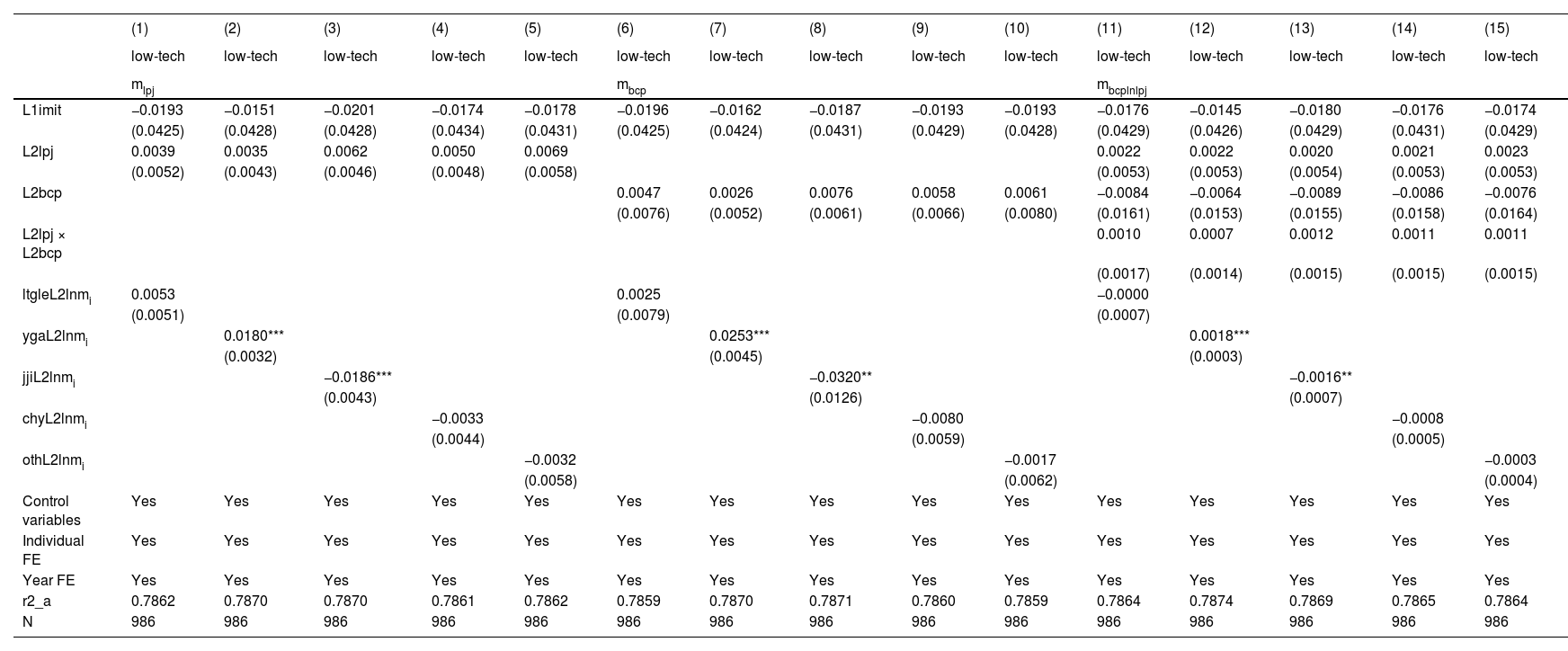

As mentioned, since we regard the technical spillover from spare parts and semifinished products as both process and product innovations that are capable of disseminating knowledge across sectors, we also investigate their impact on innovation within high-tech manufacturing sectors. Furthermore, we explore whether the interaction between these factors requires additional innovation to drive knowledge transfer effectively. To this end, we also include the interaction that occurs at t−1 between the technical spillover from spare parts in the region (lpji,t) and the semifinished products of the same region (bcpi,t). Therefore, we augment Eq. (14) as follows:

Why does the technical spillover from imported intermediates drive high-tech innovation and low-tech innovation? This is a question of great significance; thus, our research aims to provide further empirical analysis to determine the relevance of the proposed mechanism. Understanding how the intermediate input imports of firms impact high-tech innovation and low-tech innovation could have far-reaching implications for the field of innovation and technology.

The absorption capability of a region usually involves multiple aspects. This paper evaluates the absorption capabilities of a region by calculating the interaction product of the number of researchers and government investment via a simplified method, which can reflect the region's investment in human resources and technology funding (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Chen et al., 2017a). Under the premise of constant market characteristics, the scales of high-tech and low-tech innovation are positively correlated with regional technological absorption. As previously stated, we consider that regional technological absorption could improve high-tech and low-tech innovation; thus, we test whether the technical spillover from imported intermediates has an impact on regional technological absorption capabilities to test whether regional technological absorption is the mechanism of the effect on innovation through the technical spillover from imported intermediates. Therefore, we augment Eq. (15) as follows:

We employ a range of research methods for the analysis of the data, beginning with a baseline fixed effect model analysis. Next, we adopt a Bartik IV approach to check the presence of potential biases in the model variables for endogeneity. We subsequently apply quantile regression to investigate how the influence of technical spillover from imported intermediates differs across regions exhibiting disparate levels of technological innovation. Finally, we utilize a spatial model to examine the presence of spatial spillover effects, considering both the effects of the dependent variable with spatial lag and time-spatial lag.

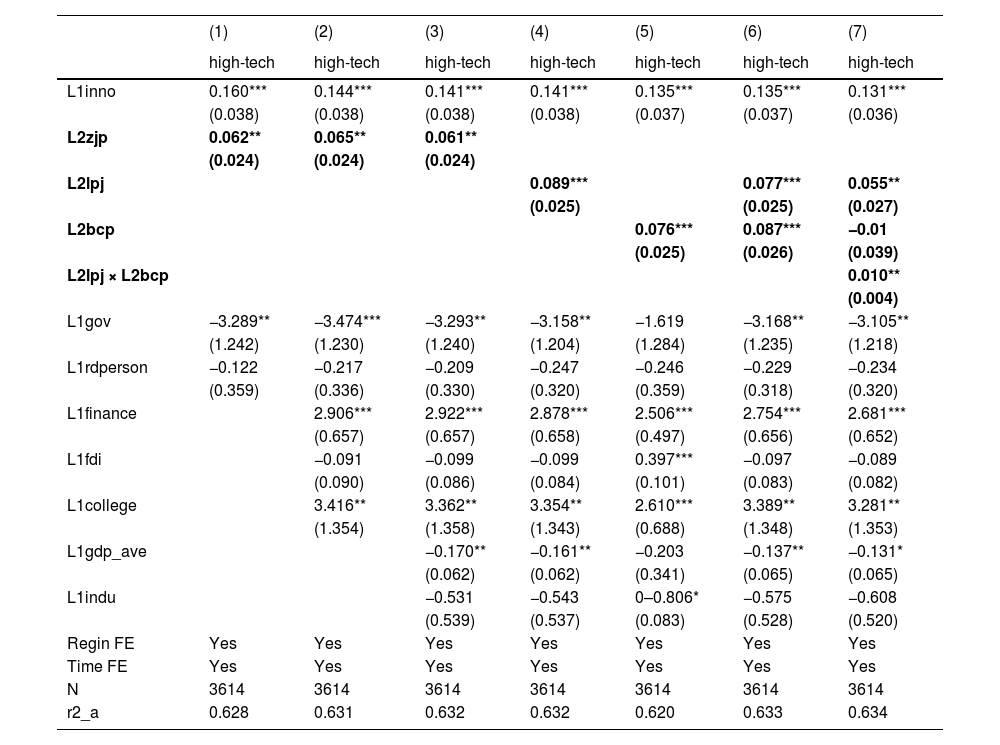

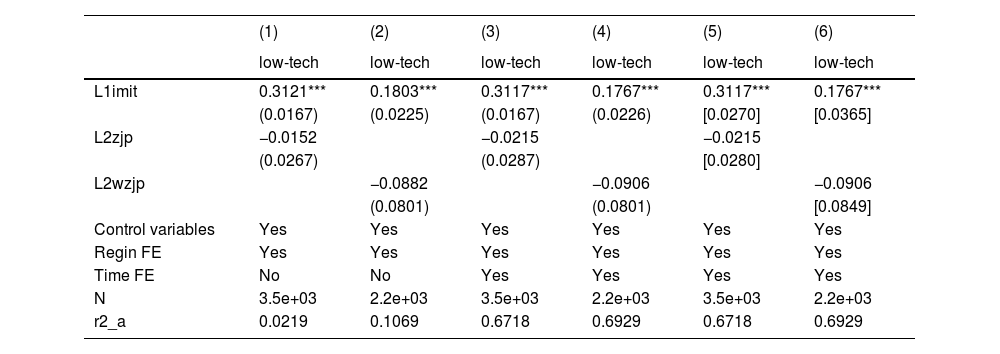

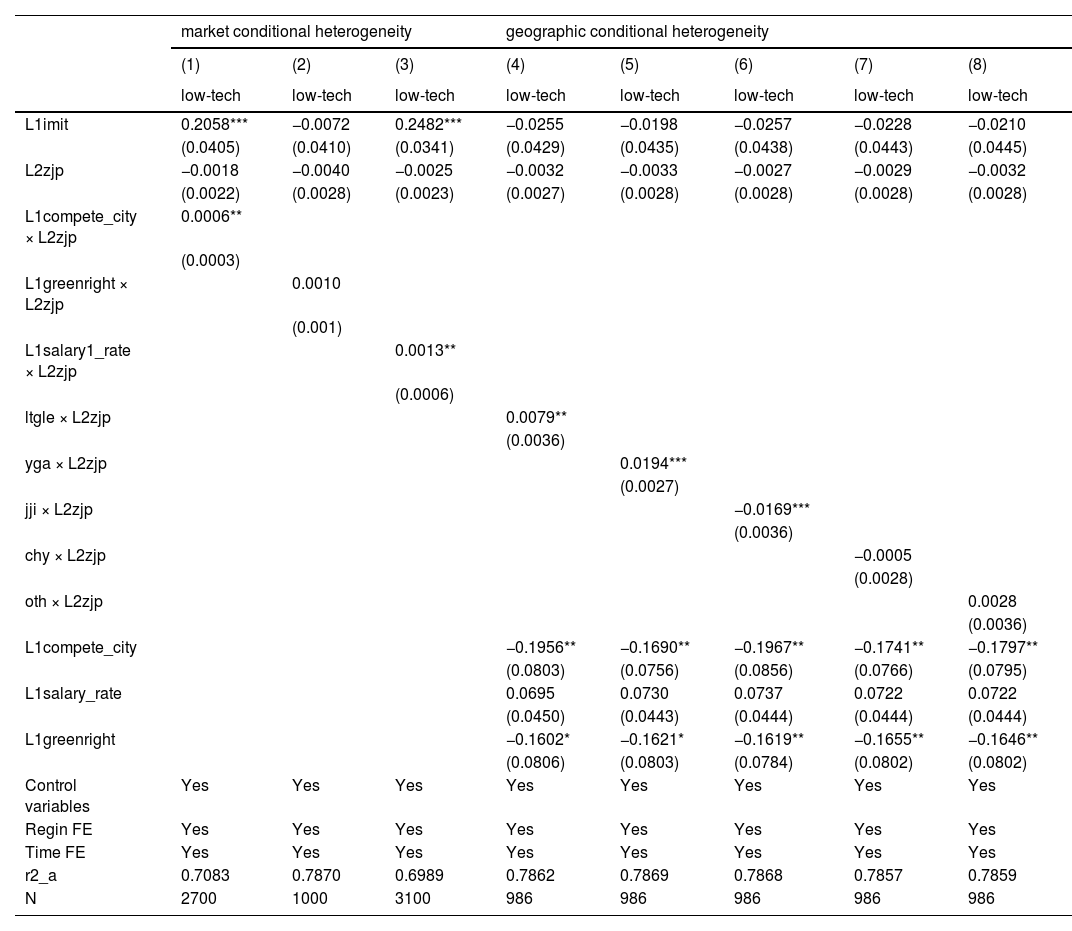

ResultsWhat imported intermediate technical spillover drives high-tech innovation and low-tech innovation?Table 4 and Table 5 shows the results of our dynamic model estimation for high-tech and low-tech innovation, as derived from Eq. (13) and Eq. (14). We introduce controlled variables and assess the impact of technical spillovers from imported intermediates, as described in Columns 1 to 3. In Columns 4–5, we estimate the effect of process innovation and product innovation, as per Eq. (14). Finally, we assess the interaction between process innovation and product innovation to determine their collective significance, as indicated in Column 6. Our initial analysis employs a panel fixed effects model incorporating regional and temporal fixed effects, facilitating control over unobserved heterogeneity and estimating region-specific and time-specific fixed effects (Bell & Jones, 2015).

FE model of the technical spillover from imported intermediates that drives high-tech innovation.

Notes: Clustered standard errors at the regional level in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1, 5, and 10 % levels, respectively. The same applies to the following tables.

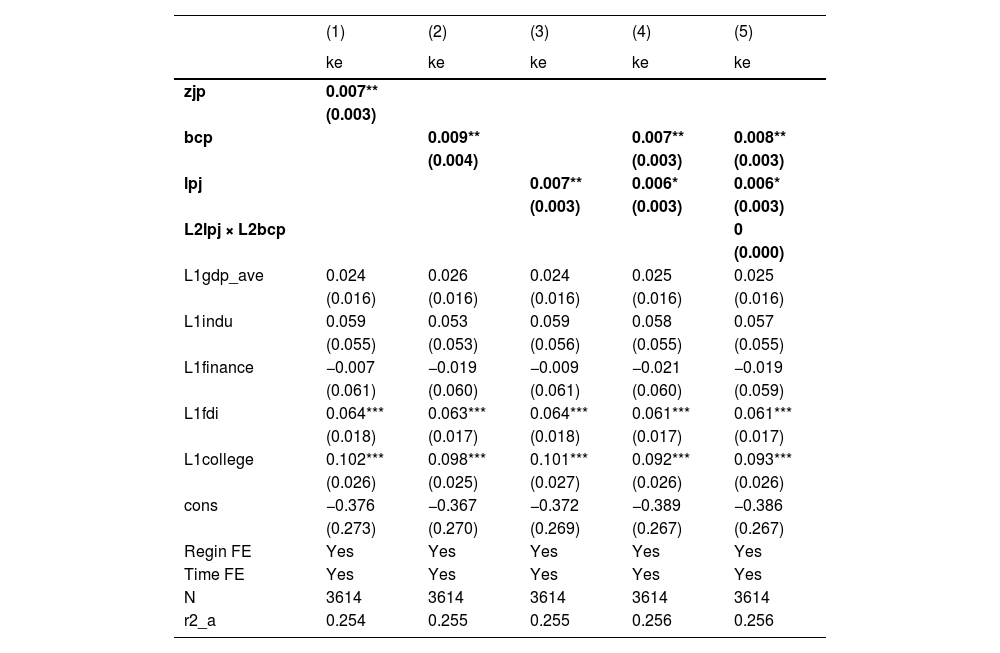

FE model of the technical spillover from imported intermediates that drives low-tech innovation.

High-tech innovation: In examining high-tech innovation, which is quantified by the total number of patents in high-tech innovation, Table 4 shows that as expected, past high-tech innovation positively influences current innovation performance. Regions with high-tech patent applications at time t-1 have a higher level of innovation at time t. Regarding our variables of primary interest, the role of imported intermediates in technical spillover is key to high-tech innovation. The technical spillover from spare parts, the technical spillover from semifinished products, and their interaction exhibit positive associations with the growth of high-tech patents, with significant coefficients observed in Columns 4–6. According to our preferred model specification (Column 3), a one-percentage-point increase in the technical spillover from imported intermediates in region I at time t-2 corresponds to a 0.06 % increase in the number of high-tech innovations in region I at time t. Simultaneously, the technical spillover from spare parts and semifinished products appears to have a pronounced impact. This effect results in an increase of 0.089 % and 0.076 % in the number of high-tech patents in a given region (i) for a specific time (t), as shown in Columns 4–6 (Fedyunina & Averyanova, 2019; Kroll, 2023). The observed positive correlation supports Hypothesis 1a and Hypothesis 3b that the local technical spillover from imported intermediates drives the scale of high-tech innovation, leading to technical dividends; then, the enterprise's product innovations enhance high-tech innovations.

The findings in Table 5 (low-tech innovation) demonstrate a positive correlation between the technical spillover from imported intermediates (including in semifinished products and spare parts) and the growth of low-tech innovation. However, this correlation is not statistically significant, as indicated in Columns 2, 4, and 7. Consequently, this finding does not substantiate Hypothesis 1b or Hypothesis 3a. The results in the table demonstrate that technological spillovers from imported intermediate goods have a positive driving effect on low-technology innovation, but the magnitude of the effect does not reach a statistically significant level. This finding coincides somewhat with our hypothesis of a ‘low-end lock-in’ effect.

The reasons may be the complex interplay of multiple external factors that results in a lack of statistically significant empirical results for low-tech innovation. First, the continuous increase in labour costs in China in recent years has increased the operational burden on firms engaged in low-end, labour-intensive activities. This heavier burden has led many firms to reduce their investment in low-tech innovation, instead favouring automation, intelligent manufacturing, or innovations with higher value added. Second, the increasingly competitive market environment has compelled firms to pursue differentiated competitive advantages, reducing the incentives for investment in easily imitable and low-margin low-tech innovations. In addition, government policy preferences have further driven firms to shift their innovation focus from low-tech to high-tech domains, such as the dual control of energy consumption and emission reduction measures. These external influences may partially obscure the real impact of technological spillovers from imported intermediates on low-tech innovation. To more accurately assess the effects of imported intermediate spillovers on low-tech innovation, Section 5 of this paper incorporates key control variables, including labour cost indices, market competition intensity, and relevant government policy indicators, to isolate and account for potential confounding factors. Furthermore, this paper systematically discusses feasible pathways for firms to avoid falling into the 'low-end lock-in' trap.

The mechanism understands this interesting observation; we provide one explanation derived from a highly simplified and stylized mode. We develop an FE model borrowed from the baseline to examine whether the imported intermediate technical spillover could increase absorption capabilities in region i. We then obtain the results of our estimation of Eq. (15) in Table 6, which show that the technical spillover from imported intermediates, semifinished products, and spare parts positively correlates with regional absorption capabilities, with statistically significant coefficients observed across Columns 1–6. This positive correlation could confirm the hypothesis that the technical spillover from imported intermediates in the local region improves regional absorption capabilities. Regional technological absorption capabilities are instrumental in fostering the diffusion and assimilation of technology among local firms and their supply chain counterparts, and this dynamic accelerates the formation of “industrial linkages” and “industrial agglomerations” (Miroshnychenko et al., 2021). This subsequently enhances the development of a “talent dividend” and “learning effects” within the local area (Chaparro et al., 2021; Cuéllar et al., 2024), which in turn reduces the costs of high-tech innovation.

FE model showing that the technical spillover from imported intermediates enhances regional absorption capabilities.

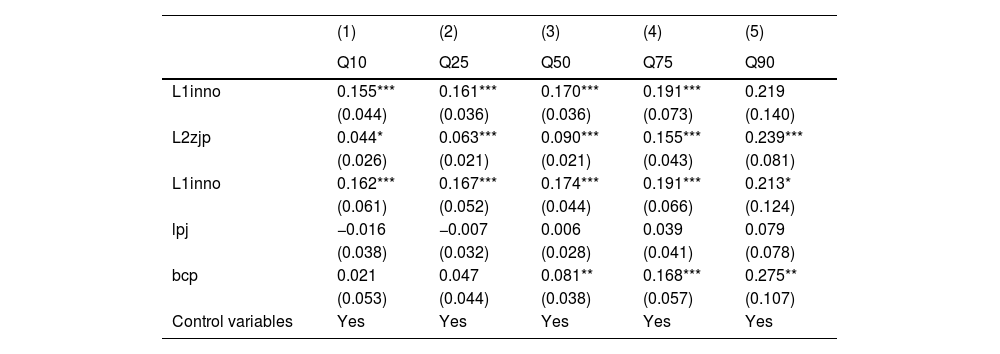

We conduct an asymmetry analysis employing the quantile regression method (Koenker & Hallock, 2001) to assess the differential impacts of technical spillover from imported intermediates on regional innovation in areas with varying levels of high-tech innovation (Sergio et al., 2023). This analysis allows us to identify threshold effects, nonlinearities and other complex relationships that traditional linear models may not capture. This analysis improves our understanding of how the technological spillovers of imported intermediates contributes to the regional innovation landscape.

As shown in Table 7, the coefficients related to the technical spillover from imported intermediates (ln2zjp) follow a positive trend across various quantiles. Specifically, these coefficients are not statistically significant at the lower decile (10th percentile). The quantile regression analysis reveals a significant positive correlation between the coefficients associated with the middle (Q50) and upper (Q75) quartiles indicating an emerging positive effect of the technical spillover from imported intermediates on high-tech innovation within the respective regions. The correlation is markedly pronounced in the highest quartile (Q90), underscoring that intermediates with greater technological spillovers are most influential in catalyzing innovation in regions characterized by a higher frequency of high-tech patent filings. These regions where likely already possess advanced innovation capabilities and technological absorptive capacity, are well positioned to exploit the technological sophistication of imported intermediates, thereby driving forward high-tech innovation.

Quantile analysis: High-tech innovation.

The quantile regression analysis in Table 7 reveals that the technological spillovers of imported spare parts (lnlpj) and semifinished products (lnbcp) on innovation activity varies across regions with differing levels of technological innovation activity. In regions with low levels of innovation activity (Q10 and Q25), the contribution of technological spillovers from import spare parts and semifinished products to high-tech innovation is muted because of the limited capacity of local firms to assimilate and apply these advanced technologies effectively. Conversely, in regions with moderate innovation activity (Q50), a positive correlation emerges between the technological spillovers of imported semifinished products and the upsurge in high-tech innovation, concurrent with increased innovation activity. These products are instrumental in product innovation and bolster market competitiveness serving as key inputs for further processing and commercialization endeavors. In regions with greater technological innovation activity (Q75 and Q90 quantiles), the technological spillovers of semifinished products becomes a substantial driver of high-tech innovation.

Moreover, although positive, the coefficient for spare parts is not significant. Firms in these regions effectively leverage the technological intricacies of imported intermediates to stimulate local high-tech innovation. The robust technological absorptive capacity and advanced innovation ecosystems in these regions provide firms with essential research and development support, human capital and financial resources, which are all critical for transforming technological spillovers into innovative outcomes.

It underscores the pivotal role of product innovation in directly fostering high-tech patents instead of process innovation. By providing an in-depth examination of the disparate influences of the technological spillovers of imported intermediates on high-tech patent generation across various regions, the nuanced analysis presented in this research deepens our comprehension of the mechanisms by which technological spillovers is transmitted throughout global value chains.

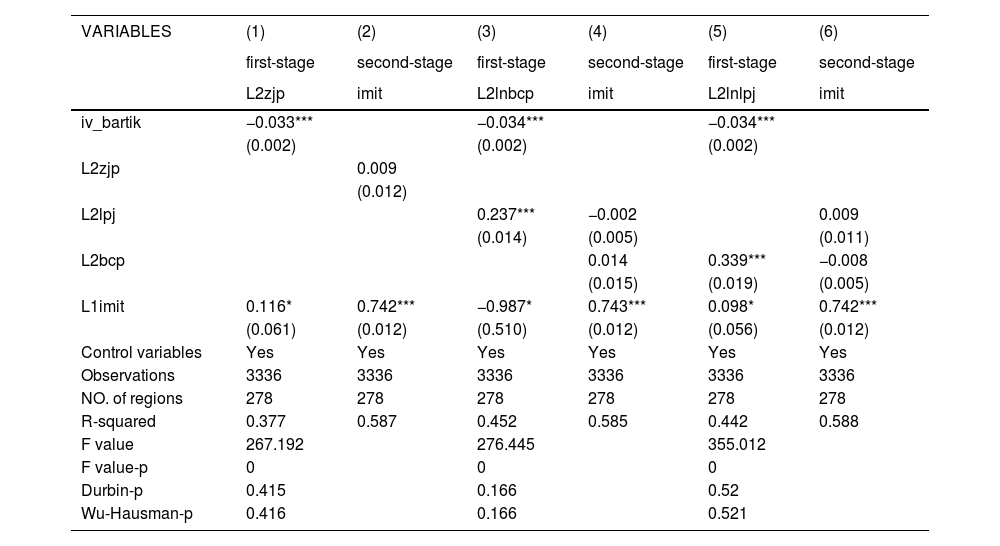

Bartik IV results: imported intermediates, process innovation and product innovation effects drive high-tech innovation and low-tech innovationIn the preceding sections, we explicated the fixed effects model delineated in the econometric which is inherently designed to regress the dependent variable at a given time against its preceding value. This methodology engenders a dynamic element, necessitating an econometric strategy to reduce potential biases in the estimation process. One such strategy employs the Bartik instrument model, which is particularly salient in addressing concerns of endogeneity that may stem from omitted variables or reverse causality.