Rapid artificial intelligence (AI) advancements have emerged as a critical catalyst in curbing carbon emissions and fostering sustainable growth. Drawing upon balanced panel data from 30 Chinese provinces from 2000 to 2022, this study employs the spatial Durbin model, along with mediating and moderating effect models, to explore the influence of industrial intelligence on urban carbon emissions and the underlying mechanisms. The findings reveal an inverted U-shaped relationship between AI development and carbon emissions, exhibiting a critical transition threshold at 12.57 AI firms per 10,000 km². Beyond this threshold, carbon intensity transitions from persistent growth to sustained decline. Mechanism analysis demonstrates differentiated mediation effects: Industrial rationalization significantly mediates emission reduction by optimizing production processes, whereas industrial advancement shows null mediation due to energy rebound effects and time-lag constraints. Moderating effect analyses show that human capital amplifies AI’s decarbonization efficacy. Meanwhile, marketization exhibits statistically insignificant moderation effects, which is attributable to institutional failures in environmental pricing and carbon market fragmentation.

Amidst the increasing challenges posed by global climate change, carbon governance has attracted widespread attention internationally (Ding and Liu, 2023; Falatehan et al., 2025; Houten and Wedari, 2023; Khairunnisa et al., 2024; Luqman et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024b). Consequently, a key research topic is innovative and efficient social technologies that can facilitate carbon neutrality and support the broader goal of sustainable global development (Deng et al., 2024; Lin, 2023). Widely regarded as the foundational engine of the fourth industrial revolution, AI is particularly playing an increasingly transformative role in reshaping economic systems, societal frameworks, and industrial configurations worldwide (Baboe et al., 2025; Shah et al., 2024; Sohail Shaik et al., 2024). Notably, China has demonstrated exceptional progress in AI, currently leading the globe in terms of investment volume and financing scale (Xi et al., 2024). Moreover, as one of the largest carbon emitters, China's progress in AI technology is significant not only for building a complete technical system in areas such as smart chips, large models, infrastructure, and operating systems, but also for its wide application across smart cities, smart manufacturing, smart agriculture, and numerous other areas (Zhou et al., 2024). However, AI technology has two sides. On the one hand, the associated compute requires a large amount of energy, particularly electric energy. On the other hand, AI also promotes technological advancement, encourages the adoption of energy-efficient innovations, and supports industrial transformation. Within this practical context, investigating whether AI can serve as a viable tool for achieving carbon neutrality holds substantial real-world relevance.

Indeed, with the rise of the digital economy, scholarly interest has increasingly turned to examining how digital innovations and digital economic frameworks influence carbon emissions (Liu et al., 2021). Research on AI-driven carbon reduction primarily focuses on three key dimensions. First, numerous scholars have examined AI's systemic potential in climate change mitigation. AI technologies can deliver significant, scalable emission reductions through optimized energy systems, accelerated renewable energy integration, and enhanced energy efficiency improvements (Dhar, 2020; Paul et al., 2023). Second, studies have specifically examined AI's practical decarbonization effects, with robust evidence showing that industrial intelligentization, smart manufacturing, and urban-scale AI applications help reduce carbon intensity per unit output (Dong et al., 2024; Tao et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024b; Wu et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024; Zhong et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2024). Third, AI applications in carbon capture and storage (CCS) systems has emerged as a critical research frontier. Here, AI algorithms' real-time optimization of absorption-based carbon capture processes can simultaneously increase capture rates while reducing energy consumption, thereby addressing a fundamental technical barrier to large-scale CCS deployment (Aliyon et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Qerimi and Sergi, 2022; Surender et al., 2021).

However, three key limitations in extant research on the AI-carbon emissions relationship warrant attention. Theoretically, studies have yet to develop an integrated framework that combines the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) with technology diffusion theory and other multidimensional perspectives. Thus, these studies fail to adequately explain the inherent tension between AI's high energy consumption and its emission reduction potential. Empirically, most analyses overlook threshold effects and spatial heterogeneity, potentially leading to biased conclusions that overgeneralize linear negative correlations (Gaur et al., 2024). Methodologically, the predominant reliance on static econometric models lacks systematic integration with policy text analysis, case studies, and spatial econometrics, limiting the findings’ robustness and contextual validity (Shah et al., 2024).

Addressing gaps, this study develops an integrated "EKC-Technology Diffusion-Green Computing" tripartite theoretical framework to systematically analyze the "high energy consumption-high emission reduction" paradox of AI technologies and their dynamic balancing mechanisms. Building upon this theoretical foundation, a dynamic spatial Durbin model is used to capture the nonlinear carbon reduction effects of AI technologies. This is complemented by policy text analysis and in-depth case studies of representative enterprises. Together, this provides micro-level evidence on the theoretical mechanisms. Thus, this study establishes a robust analytical framework that combines macro-level quantitative assessment with meso- and micro-level qualitative validation.

Theoretical analyses and research hypothesesLiterature review(a) Overview of drivers of carbon neutrality

Carbon neutrality involves reaching a peak in carbon dioxide emissions over a certain period and then reducing them to achieve a net-zero carbon emissions state. The ultimate goal is to reach net-zero carbon emissions (Guo et al., 2022; Hasanov et al., 2024). In particular, urban carbon neutrality is influenced by social, economic, technological, and institutional aspects. The literature has primarily analyzed the impacts on urban carbon reduction through economic development, technological innovation, industrial restructuring, energy consumption pattern shifts, energy intensity variations, population concentration, and regulatory frameworks. Among them, economic development stands out as both a major contributor to carbon emissions and crucial element in constraining carbon peaks and neutrality. In the early stages, economic growth inhibits green development. However, as economic growth reaches higher levels, it fosters a greater pursuit of green development efficiency and the ability to enhance green development, following the EKC (Dumbrell et al., 2022; Ekins et al., 2017; Pattison, 2019; Seyfettin, 2021; Wang et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2024).

Second, technological innovation is essential for urban decarbonization. Self-innovation and technological progress can promote energy efficiency, pollution control technology, resource utilization, and reduce pollution emissions, thus achieving carbon reduction and increased efficiency (Bakari et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2021; Du et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021; Li and Zhu, 2024; Raihan et al., 2023; Su et al., 2020; Ullah et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2017). Meanwhile, industrial restructuring is a primary method for adjusting the carbon emission structure. By facilitating the reallocation of input factors from less efficient industries to sectors with higher productivity, it creates a "structural dividend", serving as a significant force for green development and high-quality carbon reduction (Cheng et al., 2018; Hza et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2023; Tian et al., 2019; Yu and Wang, 2021). Next, energy consumption structure adjustment is a vital pathway for promoting energy efficiency and controlling carbon emissions. Decreasing the dependence on high-carbon energy sources, such as coal, petroleum, and natural gas, within both energy production and usage can help achieve regional emission reduction goals while simultaneously ensuring steady economic development (Sahbi et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2021; Zafar et al., 2019). The shift in energy mix enables regions to meet their emissions reduction targets while maintaining economic growth (Irandoust, 2016; Rasoulinezhad and Saboori, 2018). Finally, policy regulation provides the institutional guarantee for carbon reduction. Environmental regulation policies are vital tools for controlling carbon emissions. Studies show that they can effectively curb emissions (Danish et al., 2020; Hu and Wang, 2020; Sarfraz et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2024). However, these policies also produce innovation compensation and compliance cost effects, resulting in uncertain or non-linear carbon reduction outcomes (Gao, 2024; Liu et al., 2022;).

(b) AI-driven carbon neutrality review

Rapid AI technological advancements have profoundly changed both the economy and society, particularly in relation to carbon emissions. Researchers have examined the influence of AI on carbon output from multiple perspectives: First, a substantial literature suggests that AI is poised to become a vital instrument in global carbon mitigation efforts. For instance, Dhar (2020) explored the intersection of AI and climate change, concluding that significant emission reductions can be achieved by developing tools to measure the carbon footprint of machine learning models and transitioning toward more sustainable AI infrastructures. Paul et al. (2023) analyzed AI use for energy consumption, photovoltaic power forecasting, and electric vehicle pathways based on case studies in Brazil, Tunisia, Sweden, and Luxembourg, finding significant CO2 emission reductions due to AI techniques. Wang et al. (2024c) examined panel data from 69 countries from 1993 to 2019 employing the STIRPAT (Stochastic Impacts by Regression on Population, Affluence, and Technology) model, mediation analysis techniques, and flat panel threshold models. Their findings suggest that AI plays a pivotal role in facilitating the energy transition and reduces carbon emissions.

Second, regarding the influence of AI on industrial carbon output, an increasing number of studies have concentrated on AI application within the industrial sector. These investigations generally indicate that integrating AI technologies with the real economy contributes to emission reductions. For instance, Chen et al. (2022) utilized panel data from 270 cities in China between 2011 and 2017, and applied the Bartik instrument to measure the presence of industrial robots in manufacturing enterprises. Their results demonstrate that AI significantly curbs the intensity of carbon emissions. Similarly, Tao et al. (2023) used provincial panel data from 2006 to 2019 to examine both the direct and spatial effects of industrial intelligence on carbon intensity. The authors found that industrial intelligence reduces industrial carbon intensity not only locally but also in adjacent provinces through spatial spillover effects. Wu et al. (2023) applied the STIRPAT framework to explore how AI affects energy efficiency and found that the deployment of industrial robots, a proxy for AI, substantially enhances carbon emission efficiency.

Zhou et al. (2024) employed a dynamic spatial Durbin model to empirically examine the mechanism through which AI influences carbon emissions using inter-provincial panel data from China. Their analysis revealed that the development level of AI exerts a significant negative spatial spillover effect on carbon emission efficiency, primarily manifesting as a short-term influence on energy conservation and emissions mitigation. Using data from 275 cities across China, Zhang et al. (2024) introduced an Attention Depth and Crossover Network (ADCN) framework to assess the impact of AI technologies on urban carbon output. Their results indicate that the interaction between AI development and the share of smart manufacturing significantly amplifies emission reduction. Zhong et al. (2024) applied the system generalized method of moments estimation method to explore AI’s impact on both pollutant control and carbon reduction. Their findings suggest that AI has a beneficial synergistic effect, simultaneously lowering pollutant levels and carbon emissions. Using data from 267 Chinese cities from 2008 to 2019, Dong et al. (2024) revealed that, on average, each additional unit of AI application reduces carbon emissions by approximately 40,100 tonnes.

Third, scholars have examined the role of AI in CCS. Qerimi and Sergi (2022) emphasized the broad applicability and substantial effectiveness of CCS technologies in addressing climate change. From 2015 to 2020, a growing literature has concentrated on how AI can enhance the CO₂ capture process, focusing on its integration with CCS systems to improve overall governance and operational efficiency (Liu et al., 2021). For instance, Aliyon et al. (2023) examined the implementation of AI in absorption-based carbon capture (ACC) methods and found that its application across various post-combustion capture technologies yields notable carbon emission reduction. Fourth, AI’s carbon reduction potential beyond traditional industrial applications. Researchers have increasingly acknowledged AI’s effectiveness in lowering emissions across several sectors, including agriculture (Mor et al., 2021), the construction industry (Ding et al., 2024), and healthcare (Bloomfield et al., 2021).

However, some scholars have questioned the unequivocally positive role of AI in climate change. Gaur et al. (2024) suggested that AI could be pivotal in halting anthropogenic climate change, given its potential to mitigate environmental degradation and global warming, but cautioned against overlooking the dual nature of AI's environmental impact. Shah et al. (2024) analyzed panel data from countries in East Asia and the Pacific from 2000 to 2023 using the fully modified ordinary least squares regression, dynamic ordinary least squares regression, Hausman fixed effects, random effects, generalized method of moment estimation, and variance decomposition analysis. Their findings revealed a positive association between AI development and carbon emissions; however, the variance decomposition results suggest that AI exerts only a marginal influence on overall CO₂ emissions.

Given AI’s growing role as a fundamental engine of economic and societal progress, its importance in advancing global carbon neutrality targets is becoming increasingly evident. Nevertheless, the intricate and multifaceted nature of the relationship between AI technologies and carbon emissions underscores the need for deeper, more comprehensive investigation.

(c) Research Gaps and Contributions of This Study

Through a systematic review, this study synthesizes and evaluates extant research on the relationship between AI and carbon emissions, aiming to identify key theoretical frameworks, methodological approaches, and empirical findings. The analysis reveals several critical research gaps.

Theoretically, extant studies predominantly adopt singular analytical frameworks. They either examine the macro-level relationship between economic development and carbon emissions through the EKC (e.g., Zhou et al., 2024), or investigate the micro-level mechanisms of AI technology diffusion (e.g., Chen et al., 2023). However, this theoretical segregation fails to integrate multiple perspectives to systematically explain AI's unique "high energy consumption-high emission reduction" duality. Such theoretical fragmentation impedes a comprehensive assessment of AI's dynamic environmental impacts, particularly in balancing the inherent tension between its energy demands and decarbonization potential (Gaur et al., 2024).

Methodologically, extant research primarily relies on conventional econometric approaches (e.g., static panel models). Few consider the systematic integration of qualitative methods, such as policy text analysis and case studies, with advanced quantitative techniques like spatial econometrics. This methodological narrowness limits the ability to fully capture the complex, multi-layered mechanisms through which AI influences carbon emissions. Hence, extant analyses lack both contextual depth and spatial dimensionality.

Empirically, most studies report a linear negative correlation between AI adoption and carbon emissions. However, these findings may be subject to bias due to two critical oversights (Liu et al., 2021). First, the prevalent neglect of threshold effects, whereby AI's energy consumption may offset emission reductions when penetration rates fall below critical levels (Zhou et al., 2024). Second, the widespread omission of spatial heterogeneity, as the geographically uneven diffusion of AI technologies generates asymmetric regional spillovers in emission reduction outcomes (Shah et al., 2024). These limitations underscore the need for more nuanced empirical frameworks that account for nonlinear dynamics and spatial interdependencies.

Addressing these gaps, this study makes three key contributions to the literature. Theoretically, it develops an integrated analytical framework that synthesizes the EKC, technology diffusion theory, and green computing paradigm, providing a more comprehensive understanding of AI's dual role in carbon emissions. Methodologically, this study adopts a mixed-methods approach that combines econometric analysis, policy text mining, and case study evidence to enhance the robustness of empirical findings. Empirically, this study identifies critical threshold effects and spatial spillover mechanisms that elucidate the nonlinear and regionally heterogeneous nature of AI's environmental impacts. Table 1 systematically categorizes extant research to contextualize these advancements.

Taxonomy of AI-Carbon Emissions Research.

| Classification Dimension | Sub-categories | Representative Studies | Key Findings/Methodological Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Applications | |||

| 1. EKC | AI emission-reduction effect | Wang et al. (2024c) | AI demonstrates carbon-mitigation benefits. |

| Linear emission reduction in industrial AI | Chen et al. (2022) | Significant reduction in carbon intensity | |

| AI applications in energy management and photovoltaic power generation | Paul et al. (2023) | Case studies demonstrating CO₂ reduction | |

| 2. Technology Diffusion Theory | Optimization of CCS technologies | Qerimi and Sergi (2022); Liu et al. (2021) | Significant emission reduction effects |

| Enhancement of ACC efficiency through AI | Aliyon et al. (2023) | Improved CO₂ capture performance | |

| Smart manufacturing synergy effects | Zhang et al. (2024) | ADCN framework quantifying industrial interactions | |

| 3. Green Computing Theory | Sustainable AI infrastructure | Dhar (2020) | Machine learning carbon footprint measurement framework |

| Research Methods | |||

| 1. Econometric Methods | Threshold tests | Wang et al. (2024c) | STIRPAT model applications |

| Instrumental variable tests | Chen et al. (2022) | Bartik instrument implementation | |

| Spatial spillover effects analysis | Zhou et al. (2024) | Dynamic spatial Durbin model | |

| 2. Machine Learning Methods | ADCN framework | Zhang et al. (2024) | ADCN |

| 3. Case Study Methods | Empirical case analyses | Paul et al. (2023) | Cross-country comparative studies |

| Research Findings | |||

| 1. Linear Negative Correlation | Industrial AI applications significantly reducing emissions | Chen et al. (2022); Paul et al. (2023); Tao et al. (2023); Wang et al. (2024b); Wu et al. (2023); Zhang et al. (2024); Zhou et al. (2024) | Consistent evidence across studies |

| 2. Nonlinear Relationships | Marginal emission reduction effects | Dong et al. (2024) | Approximately 40,100-ton CO₂ reduction per AI unit |

| Limited carbon reduction effectiveness | Shah et al. (2024) | The carbon-mitigation effect of AI remains uncertain. | |

EKC establishes that transformative technologies initially intensify environmental stress before enabling net decarbonization (Grossman and Krueger, 1995). This trajectory is mediated through technology diffusion stages (Rogers and Schuster, 2003), with the green computing paradigm acting as the critical catalyst for the reversal in carbon-emissions (Zhu, 2025) (Figure 1).

During the early phase of AI adoption and integration, carbon emissions are likely to increase. The innovator phase of AI diffusion is characterized by self-reinforcing carbon-intensive dynamics primarily driven by three interlocking mechanisms. First, technological lock-in perpetuates reliance on legacy infrastructures (Unruh, 2000), creating path dependencies that favor energy-intensive computational systems over sustainable alternatives (Yu et al., 2024). The absence of established green standards sustains suboptimal energy-knowledge conversion efficiency, where computational outputs fail to achieve proportional decarbonization benefits relative to energy inputs (Gu, 2022). Institutional inertia impedes the adoption of sustainable computational practices, as regulatory frameworks and industry norms lag behind the technological possibilities (Zhao et al., 2024). These mechanisms collectively create carbon lock-in: Technological choices constrain institutional reforms, while institutional rigidities reinforce technological stagnation. This creates a vicious cycle that delays green computing adoption during early diffusion phases.

The transition phase represents a critical inflection point where green computing principles initiate the systemic reconfiguration of AI architectures. As Rogers' diffusion theory predicts, this stage witnesses standardization effects dismantling the path dependencies inherited from legacy hardware deployment (Rogers and Schuster, 2003). Crucially, policy-institution synergies amplify this shift: Regulatory frameworks like the European Union’s Energy Efficiency Directive incentivize algorithmic optimization. Meanwhile, carbon pricing mechanisms internalize computational externalities (Mercure et al., 2018; Mo et al., 2023). This catalytic convergence of technical standardization meeting institutional innovation disrupts the carbon lock-in established during the innovator stage, enabling progressive migration toward energy-proportional computing models (Fu et al., 2023).

At maturity, the green computing paradigm dominates through three mutually reinforcing mechanisms: First, hardware-algorithm co-evolution enables ultra-efficient computation, wherein neuromorphic chips dynamically adapt to sparsity patterns in deep neural networks (Zhu, 2025). Second, carbon-aware systemic substitution displaces emissions-intensive processes. For instance, AI-driven demand response systems automatically redirect computational loads to renewable-rich temporal windows (Xu and Huang, 2024). Third, closed-loop innovation establishes negative carbon intensity. Blockchain-verified carbon removal credits are integrated into circular manufacturing workflows, creating verified net-negative computational lifecycles (Bardeeniz et al., 2025). This triad embodies the EKC's ultimate phase, wherein technological advancement transcends mitigation to actively regenerate environmental capacity.

Building on this analysis, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis H1: AI development and carbon emissions have an inverted U-shaped relationship: Emissions rise during the initial growth phase as computational demand and infrastructure expand, and then decline once the technology matures, efficiency gains accumulate, and widespread adoption enables systemic optimization.

As a foundational component of the latest industrial transformation wave, AI profoundly influences industrial advancement and restructuring. Industrial upgrading encompasses both industrial rationalization (i.e., optimizing resource allocation and enhancing production efficiency) and industrial advancement (i.e., transitioning to higher-end, more complex and higher value-added industries).

Building on the resource-based view, AI optimizes production resources through data-driven reconfiguration, effectively eliminating resource misallocation (Klenow, 2009). For instance, intelligent scheduling systems dynamically enhance supply chain energy efficiency, enabling regions to leverage comparative advantages while reducing the energy redundancy caused by the organizational inefficiencies in traditional production models. The economies of scale driven by AI further amplify this process. By expanding production capacity and lowering marginal costs (e.g., clustered intelligent manufacturing), AI achieves Pareto improvements in resource allocation (Fang et al., 2024). Such specialization and resource optimization significantly curb the expansion of energy-intensive industries. This aids in systematically reducing total carbon emissions through continuous declines in carbon footprint per unit output (Cervini and Joglekar, 2025). Furthermore, AI enables real-time emission monitoring and dynamic adjustment of process parameters, facilitating the diffusion of green technologies beyond corporate boundaries (Heimburg et al., 2025). Concurrently, platform-based computing lowers the barriers to green transformation for small and medium enterprises, establishing cross-regional and cross-industrial collaborative emission-reduction networks that amplify decarbonization outcomes (Wang et al., 2024b; Weber et al., 2024).

Hypothesis H2a The integration of AI technologies promotes industrial rationalization, which in turn reduces carbon emissions.

Drawing on industrial structure evolution theory (Chenery et al., 1986), AI drives the transition toward technology-intensive industries (Aghion et al., 2019), achieving systemic carbon reduction through three synergistic mechanisms: First, AI accelerates the shift to high value-added sectors (e.g., semiconductor design and intelligent algorithm services), directly displacing traditional high-carbon production capacity (Amoah et al., 2024; Ishfaq et al., 2024). Second, technological innovation shortens the regeneration phase of industrial life cycles, enhancing the penetration of low-carbon technologies (e.g., AI-enabled carbon capture systems; Marc, 2023). Third, knowledge factors systematically replace energy-intensive factors, fundamentally weakening the economy’s carbon dependency (Ayinaddis, 2025). Moreover, empirical evidence shows that a 10% increase in technology-intensive industries reduces carbon emission intensity per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) by 40–65% (Chang et al., 2023). This simultaneously decouples economic growth from emissions (elasticity declines by 0.8 percentage points), demonstrating the profound decarbonization potential of industrial upgrading (Hasan et al., 2024). Accordingly, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis H2b AI development fosters industrial advancement, thereby reducing carbon emissions.

The relationship between AI and carbon emissions is inherently complex, with human capital and marketization level serving as two critical moderating factors. Human capital determines the capacity for AI technology development and application, as a highly skilled workforce can more effectively drive AI innovation, and optimize its implementation for energy conservation and emission reduction (Alsaffar et al., 2020). Meanwhile, marketization influences the scale of investment and breadth of AI adoption through resource allocation efficiency, competitive mechanisms, and policy environments, thereby moderating AI's impact on carbon emissions (He et al., 2025; Ma et al., 2025). Consequently, AI’s carbon reduction effects are not isolated but depend on the synergistic interaction between the regional human capital endowment and market institutional environment.

Human capital’s moderating role is primarily explained by absorptive capacity theory (Levinthal, 1990). Human capital accumulation serves as a core driver of technological innovation, as highly skilled labor can more effectively assimilate and apply AI technologies to enhance energy efficiency (Balsalobre-Lorente et al., 2018). Human capital strengthens AI's carbon mitigation effects through two key pathways. The first pathway is technological absorptive capacity. A better-educated workforce can more rapidly master AI technologies, such as optimizing production processes in smart manufacturing to reduce energy waste (Tian and Zhang, 2025; Zhou et al., 2024). The second pathway is the innovation diffusion effect. Regions with concentrated human capital are more likely to develop green technology clusters, accelerating AI applications in clean energy and smart grid systems (Lei et al., 2025; Li et al., 2023). Accordingly, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis H3a The relationship between AI and carbon emissions is moderated by human capital.

Meanwhile, the moderating effect of marketization can be interpreted through institutional economics (North, 1990) and environmental innovation theory (Stavins, 2005). In regions with higher marketization, more competitive mechanisms and price signals incentivize enterprises to invest in AI technologies for reducing environmental compliance costs (Wang and Xiao, 2024). Marketization enhances AI's carbon reduction effect through two mechanisms. The first mechanism is optimal resource allocation. In highly marketized regions, capital and labor tend to flow toward high-efficiency, low-emission AI-driven industries (Yan et al., 2025). The second mechanism is the demand-pull effect. Marketization increases consumer preference for green products, motivating firms to develop low-carbon technologies (e.g., smart home devices and electric vehicles) using AI (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2018; Yang, 2025). Accordingly, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis H3b The impact of AI on carbon emissions is moderated by the level of marketization.

Figure 2 outlines the following theoretical model.

Research designVariable measurementCarbon neutrality. Carbon emissions were measured using the Inter-government Panel on Climate Change carbon emissions accounting methodology. This approach estimates emissions by aggregating outputs from multiple energy sources and subsequently normalizing the total by the region’s GDP.

- (a)

Level of AI. In current academic discourse, the degree of AI integration is often represented through metrics such as the scale of information technology services, computer-related software activity, and statistics on industrial robot deployment or density. However, these indicators often only reflect the penetration of AI in specific dimensions, making it difficult to comprehensively capture its cross-industry, multi-layered integrated impact and economic influence. To address these limitations, this study employed a more inclusive proxy variable: The number of enterprises focused on core AI businesses, measured at the provincial level. This metric can more comprehensively reflect a region’s innovation capability, concentration of high-tech talent, capital investment intensity, and level of practical technology implementation in the field of AI. Thus, it can provide a more systematic representation of the comprehensive development level of regional AI. Drawing on the classification framework presented in the "2019 China AI Development Report" jointly published by Tsinghua University and the Chinese Academy of Engineering's Knowledge Intelligence Joint Research Center, AI-related enterprises were categorized into three layers: the fundamental (enterprises engaged in AI-related hardware and software development), technical (enterprises providing data infrastructure and computing resource services), and application layers (enterprises offering AI solutions for specific practical use cases or scenarios). Enterprise data are sourced from the Tianyancha database. A complete and accurate provincial-level AI enterprise database was constructed by systematically collecting information such as registered location, year of establishment, main business scope, and operational classification, and accurately matching these to corresponding prefecture-level cities and provinces.

- (b)

Mediating variables. ① Industrial structure rationalization (isr). This concept captures the efficiency and synergy among various economic sectors, emphasizing both the inter-sectoral coordination and optimal allocation of societal and economic resources. It reflects the degree to which input factors are aligned with output structures across industries. Following Zhu and Zhang (2021) and Hui et al. (2023), the Theil index was utilized to quantitatively assess the rationality of industrial configuration (Hui et al., 2023; Zhu and Zhang, 2021) as follows:

② Industrial advancement (isu). Industrial advancement refers to the evolution and transformation of an economy’s industrial composition. It is typically characterized by a shift from lower value-added sectors, such as primary and secondary industries, toward more advanced, service-oriented tertiary industries. In line with the methodological approach adopted (Chen et al., 2023; Yang and Liu, 2025), the ratio of the output value of the tertiary sector to that of the secondary sector was used as an indicator for evaluating the degree of industrial advancement.

(d) Moderating variables. ① Human capital level (edu) was represented by the ratio of students enrolled in general undergraduate and higher education programs to the total population at year-end. ② Marketization (market) was assessed based on the provincial marketization index developed by Fang et al. (2024), which captures the overall level of market development across regions.

(e) Control variables.① Economic development level, which serves as an indicator of a region’s overall economic progress. ② Degree of openness, proxied by the share of foreign direct investment in GDP. ③ Industrial structure, measured by the proportion of the secondary sector in the regional economy. ④ Financial development, captured by the ratio of financial institutions’ deposit and loan balances to local GDP at the end of the reporting year. ⑤ Government intervention, represented by the ratio of fiscal expenditure to regional GDP.

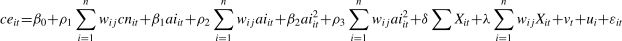

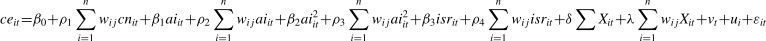

First, to verify the direct effect of AI on carbon emissions and account for the spatial spillover characteristics of carbon emissions, a spatial Durbin model was constructed as follows:

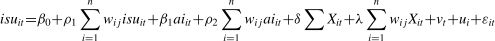

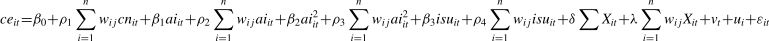

where i denotes province, t denotes year, ceit denotes the carbon emissions level for province i, t denotes year, cnit denotes carbon emissions level for province i, and aiit denotes AI for province i. wij are the elements of the spatial weight matrix used to describe the spatial proximity between regions, without loss of generality. This study uses geographical distance to calculate the spatial matrix W. vt represents the time fixed effect, ui represents the time fixed effect, εit represents the random disturbance term, and X denotes the set of control variables included in the model to account for other factors that may influence carbon emissions.Building on Dong et al.’s (2024) framework, a two-stage mediation model was adopted to investigate the mechanisms through which AI facilitates carbon emission reductions, focusing on industrial rationalization and advancing industrial upgrading. The specific model is as follows:

Equations (3) and (4), and (5) and (6) were employed to assess the mediating roles of industrial rationalization and industrial upgrading, respectively.

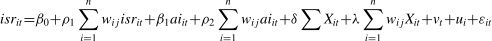

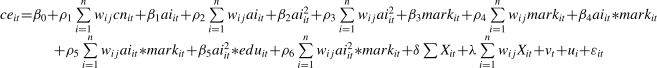

To evaluate the moderating influence of human capital and marketization level, the model incorporated the interaction terms of AI and its squared term with both human capital and marketization level in Equation (2). This yielded the two following equations:

To enhance the robustness of conclusions derived from the Spatial Durbin Model, this study integrated policy text analysis with industry datasets and representative enterprise case studies to establish multidimensional verification. For the policy analysis, topic modeling techniques were employed on provincial AI policy corpora to dissect the longitudinal evolution of regulatory orientations, thereby corroborating AI's impact on carbon emissions. Complementarily, industry-level data analytics and paradigmatic enterprise cases were utilized to triangulate the empirical findings, collectively reinforcing the inferential validity of the core research propositions.

Data sourcesThe sample period was from 2000 to 2022, drawing on data primarily sourced from the Chinese Research Data Services Platform (CNRDS) and Tianyancha databases, and provincial, municipal, and energy-related statistical yearbooks. Some missing values were computed using the interpolation method. Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics.

Descriptive statistics.

Figure 3 depicts the geographic distribution patterns of AI development and carbon emissions across provinces in 2022. Spatial distribution differences are visible across different provinces. Accordingly, AI and carbon emission levels were categorized into five grades based on their statistical distribution: low, lower, medium, higher, and high. For AI, 0, 18, 7, 3, and 1 regions belong these respective grades. Meanwhile, for carbon emissions, 5, 7, 15, 3, and 0 regions belong to these respective grades. Although Guangdong Province has the highest number of AI enterprises in 2022 and relatively high carbon emissions, the overall distribution exhibits strong spatial variation.

Figure 4 displays the Moran scatter plot illustrating the spatial correlation of AI development and carbon emissions for 2022. Most provinces fall within the first and third quadrants, suggesting a positive spatial autocorrelation between AI development and carbon emissions. Consequently, the empirical investigation should account for spatial spillover effects by applying an appropriate spatial econometric modeling approach.

The direct impact of AI on carbon neutralityFirst, the spatial correlation of the explanatory variables was examined to determine the necessity of adopting a spatial panel model. LM-lag and LM-err statistics were used for spatial diagnostic tests. The results are presented in Table 3. The LM-lag test is more significant than the LM-err test, indicating that the spatial lag model is more appropriate. Furthermore, the Hausman test confirmed that the fixed-effects model is superior to the random-effects model.

Table 4 displays the results derived from the time, spatial, and two-way fixed effects specifications within the spatial Durbin framework. The spatial autoregressive coefficients (rho) are consistently and significantly negative across all model variants, highlighting the presence of pronounced spatial dependence and negative spillover effects. Thus, changes in a region's carbon emission levels not only affect the region itself but also its neighboring regions, necessitating the use of spatial econometric models for empirical analysis.

The direct influence of AI on carbon emission levels.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time fixed effects | Spatial fixed effects | Dual-fixed effects | |

| ai | 7.713⁎⁎⁎ | 9.513⁎⁎⁎ | 9.481⁎⁎ |

| (3.292) | (2.638) | (2.567) | |

| ai2 | -0.481⁎⁎⁎ | -0.257⁎ | -0.377⁎⁎ |

| (-2.825) | (-1.995) | (-1.999) | |

| gdp | -0.500 | -0.578⁎ | -0.228 |

| (-1.431) | (-1.674) | (-0.655) | |

| fdi | -0.789⁎⁎⁎ | -0.630⁎⁎⁎ | -0.854⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-3.790) | (-3.103) | (-4.208) | |

| is | -0.722⁎⁎⁎ | -0.664⁎⁎⁎ | -0.652⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-10.875) | (-10.072) | (-9.932) | |

| finance | 3.571⁎⁎⁎ | 0.792 | 0.159 |

| (3.920) | (0.369) | (0.075) | |

| gov | -0.641⁎ | -0.526 | -0.582 |

| (-1.924) | (-1.137) | (-1.266) | |

| W×ai | -20.337 | -12.262⁎ | 12.973 |

| (-1.527) | (-1.784) | (0.530) | |

| W×ai2 | 1.879⁎⁎ | 0.465 | 1.751⁎ |

| (1.970) | (0.967) | (1.726) | |

| W×gdp | 3.956⁎ | -0.172 | 6.816⁎⁎⁎ |

| (1.699) | (-0.108) | (2.884) | |

| W×fdi | -5.216⁎⁎⁎ | -1.431 | -6.067⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-3.388) | (-1.394) | (-4.041) | |

| W×is | -0.987⁎⁎ | 0.068 | -0.443 |

| (-2.259) | (0.230) | (-1.015) | |

| W×finance | 4.321 | -11.986⁎⁎⁎ | -21.921⁎ |

| (0.845) | (-2.597) | (-1.656) | |

| W×gov | -0.265 | 0.704 | -3.772 |

| (-0.126) | (0.808) | (-1.355) | |

| Spatial rho | -0.499⁎⁎⁎ | -0.309⁎⁎ | -0.649⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-3.318) | (-2.260) | (-4.202) | |

| N | 690 | 690 | 690 |

| r2 | 0.400 | 0.162 | 0.200 |

Note: t statistics are reported in parentheses

The two-way fixed effect results show that the coefficient for the linear term representing AI is significantly positive. Meanwhile, the coefficient associated with its squared term is significantly negative. These findings suggest a statistically robust inverted U-shaped relationship between AI development and carbon emissions, thereby supporting H1.

The significantly positive coefficient associated with the linear term of AI suggests that, during the initial phases of AI technology deployment and innovation, carbon emissions may rise. This upward trend can be attributed to several contributing factors. First, the early development and implementation of AI, especially in fields like deep and machine learning, entail highly energy-demanding computational processes (James et al., 2024). These processes often rely on fossil fuel-based energy, thereby increasing overall energy use and emissions. Second, the foundational infrastructure required to facilitate AI advancement, including large-scale server farms and data centers, considerably amplifies energy demand in the short run, subsequently elevating carbon emissions (Guo et al., 2022). Third, the immaturity of AI technology and lack of energy-saving effects in its early stages can lead to inefficient energy use, thus increasing carbon emissions (Wang et al., 2024b).

In contrast, the significantly negative coefficient of the AI squared term indicates that as AI technologies continue to evolve and become more sophisticated, their influence on carbon emissions declines. This shift can be explained in several ways. First, AI advancements have contributed to enhanced energy efficiency across various applications (Chen et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024; Zhong et al., 2024). With technological progress, AI systems can perform more tasks while consuming less energy, thereby decreasing the carbon emissions generated per computational operation. For instance, AI can enable real-time monitoring, analysis, and forecasting of renewable energy systems, thereby improving energy storage efficiency and reducing operational costs. Additionally, AI plays a crucial role in mitigating the intermittency challenges associated with renewable power generation by enhancing grid stability and reliability (Aliyon et al., 2023). Second, AI can aid in achieving optimal resource allocation. AI applications in resource management, such as smart grids and supply chain optimization, play a pivotal role in minimizing energy inefficiencies and enhancing resource utilization, thereby contributing to lower carbon emissions (Wang et al., 2024a). Within smart grid applications, AI technologies can forecast both energy supply and demand, enabling electricity distribution optimization and the mitigation of energy losses (Shah et al., 2024). Furthermore, in supply chain operations, AI can streamline logistics by identifying the most efficient transportation routes, which reduces fuel consumption and lowers the emissions associated with the movement of goods (Paul et al., 2023). Third, AI improves environmental monitoring and prediction capabilities (Dhar, 2020). The application of AI in environmental monitoring and climate change prediction can help to more accurately identify and predict carbon emission sources, enabling more effective emission reduction measures (Fu et al., 2023). For instance, AI can simulate changes in the key processes of the carbon cycle in terrestrial ecosystems from seasonal to interdecadal scales, and accurately simulate and reproduce changes in terrestrial carbon sinks and their causes under extreme climate events (Mor et al., 2021). This capability is essential for timely responses to climate change and formulating appropriate mitigation strategies.

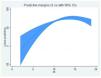

Based on the baseline regression results (βAI=9.481, βAI² =-0.377), a nonlinear equation was constructed to characterize AI's carbon impact. Further partial differentiation of this equation yielded the marginal effect function, enabling precise estimation of tipping points. The analysis revealed an inflection point at 12.57 AI enterprises per 10,000 km² (see Figure 5). This supports the existence of a definitive critical threshold in the inverted U-shaped relationship between AI and carbon emissions: When regional AI enterprise density falls below 12.57 units/10,000 km², each additional AI enterprise (i.e., +1 unit per 10,000 km²) induces a statistically significant increase of approximately 5.74 ten-thousand tons of standard coal equivalent in carbon emissions. This phenomenon stems from surging energy demands during computing infrastructure expansion and low energy efficiency attributable to technological immaturity. Conversely, once AI enterprise density exceeds 12.57 units/10,000 km², transformative technological synergy effects emerge: each additional AI enterprise drives a carbon reduction of approximately 1.83 ten-thousand tons of standard coal equivalent.

To enhance the robustness of conclusions, policy text analysis was incorporated with provincial panel econometric testing to validate the inverted U-shaped relationship between AI and carbon emissions.

For the policy text analysis, a corpus of 487 provincial AI policy documents (2000-2022) was constructed from provincial government portals and the PKULAW database.1 Using latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) topic modeling (K=10, α=0.1, β=0.01, perplexity=128.4), distinct evolutionary phases in policy orientation were identified. The results reveal three key findings: (1) During 2000-2010, policies predominantly emphasized infrastructure development, with "data centers" (TF-IDF weight=0.15) and "computing power investment" (TF-IDF weight=0.12) as high-frequency terms. Meanwhile, environmental considerations accounted for merely 7.2% of policy content. (2) Post-2016 witnessed a paradigm shift, with "intelligent energy conservation" (TF-IDF weight=0.18) and "energy efficiency optimization" (TF-IDF weight=0.16) emerging as dominant themes. (3) Notably, following the landmark Next-Generation AI Development Plan, the proportion of binding carbon emission clauses in provincial policies significantly increased from 7.2% to 23.6%. This policy transition aligns precisely with the inflection point (2015-2017) identified in the econometric models.

For provincial panel verification, data from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook was matched with the Tianyancha enterprise database. The results revealed that when provincial AI enterprise density exceeds the threshold of 12.57 firms per 10,000 km² (median value), carbon intensity shifts from growing annually to significant declines. Guangdong Province exemplifies this pattern: With an AI enterprise density of 18.3 firms/10,000 km², its carbon intensity peaked in 2016 before decreasing at an annual rate of 1.8%. Meanwhile, the share of green technologies in AI patents rose from 12.7% (2015) to 34.5% (2022). Conversely, provinces below the threshold (e.g., Hebei at 6.8 firms/10,000 km²) maintained a 0.9% annual growth rate. This multi-method validation combining policy text and provincial panel data analyses provides empirical evidence for the inverted U-shaped relationship between AI development and carbon emissions.

Mediating effect resultsTable 5 presents the estimation results on the mediating role of industrial upgrading in the relationship between AI and carbon emissions. Column (1) demonstrates a statistically significant positive association between AI and industrial structure rationalization. This can largely be explained by AI's capacity to improve industrial productivity, streamline resource deployment, stimulate technological advancement, and enhance overall product quality (Alalm and Nasr, 2018). Through automation and intelligent systems, AI increases production efficiency, leading to lower labor input and reduced time expenditure. These collectively enhance industrial output. In addition, AI technologies, particularly those involving big data analytics and machine learning algorithms, enable firms to more accurately predict consumer demand, more effectively manage inventory, and reduce resource inefficiencies. Furthermore, AI adoption fosters structural transformation and industrial upgrading, especially within knowledge-intensive and service-oriented sectors, thereby contributing to higher industrial value-added.

Mediating effect results.

Subsequently, in Column (3), which incorporates industrial rationalization, AI’s influence on carbon emissions remains robust. The coefficient of the primary term for AI continues to be significantly positive, whereas that of the secondary term is significantly negative. When compared to the two-way fixed-effects model in Table 5, the coefficient for the primary AI term decreases from 9.481 to 9.205, while the coefficient for the secondary term shifts from -0.377 to -0.447. Simultaneously, the coefficient corresponding to industrial rationalization is significantly negative, suggesting that industrial structure rationalization play a substantial role in mitigating carbon emissions.

AI optimizes the production process and improves resource allocation efficiency through its advanced capabilities in data analysis and pattern recognition, thus reducing energy consumption and waste (Liu et al., 2021). This improved efficiency is a core element of industrial rationalization and directly linked to carbon emissions reduction. For instance, AI in manufacturing can reduce machine failures through predictive maintenance, which in turn reduces energy waste and enhances productivity. Additionally, the adoption of renewable energy and low-carbon technologies during industrial rationalization effectively reduces energy consumption (Mor et al., 2021). AI technologies are increasingly being integrated during industrial rationalization to enhance energy efficiency and reduce the ecological footprint of industrial operations. In addition, AI facilitates the development of innovative, environmentally sustainable materials and production techniques, thereby fostering green innovation and contributing to the advancement of rationalized industrial structures.

This finding has been substantiated through both policy- and micro-level practical evidence. From a policy evolution perspective, China's tiered policy system strongly aligns with the econometric results. The Chinese government has established a multi-layered policy framework to promote the synergistic development of AI and industrial emission reduction.

At the policy level, the Next-Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (2017) first explicitly mandated the deep integration of AI technologies in energy-intensive industries, providing a top-level design for industrial transformation.2 Further refining the technological pathway, the Steel Industry Carbon Peaking Implementation Plan (2022) set specific targets, requiring over 80% completion of digital transformation in key production processes by 2025 and the development of more than 30 intelligent production scheduling demonstration enterprises.3 Complementary fiscal incentives, such as a 10% corporate income tax credit for AI-enabled scheduling systems under the Corporate Income Tax Preferential Catalogue for Environmental Protection Equipment, have significantly enhanced corporate adoption willingness. The synergistic effect of these policy measures has driven a rapid increase in technology penetration, with AI system coverage in key steel enterprises rising from 31% in 2020 to 63% in 2023.4

At the micro-level, the case study of Baosteel Group (600019.SH) fully corroborates the econometric findings. Empirical data from Baosteel’s production practices (2020–2023) demonstrate that its AI-based intelligent scheduling system achieved significant emission reduction through a three-stage optimization mechanism.5 First, the dynamic scheduling system based on deep reinforcement learning improved capacity utilization by 13.8 percentage points. Second, the raw material-energy synergy model reduced comprehensive energy consumption per ton of steel by 7.5% through optimized blending ratios. Third, the digital twin real-time calibration system decreased unplanned downtime losses by 23%. This case validates a key insight from the macro-level econometric model: When AI penetration exceeds an industry-specific threshold, structural rationalization effects lead to observable emission reductions. This pattern aligns with technology diffusion theory and provides micro-level evidence for policy-guided industrial low-carbon transition.

Model (2) in Table 5 shows that the effect of AI on industrial advancement is positive but statistically insignificant. Thus, Hypothesis H2b is not supported. This may be because of the following reasons: First, the shortage of skills and talents. AI technology application requires highly skilled labor. If the relevant industries lack the necessary talents and skills, the contribution of AI technology to industrial advancement will be limited. Second, technology adaptation and compatibility challenges. Existing industries may lack the infrastructure compatible with AI technology. The organizational structure and production technology facilities within firms may not be adapted to the introduction of AI technology (Xi et al., 2024). Third, AI technology R&D funding challenges. The lack of funding is a key factor that constrains enterprises from adopting AI technology. When introducing AI technologies, enterprises must invest huge sums of money to support R&D activities, experimental validation, and technology iteration. These initial investments often involve high fixed costs and operating expenses.

This study’s empirical results indicate that the mediating effect of industrial advancement in the relationship between AI and carbon emissions is not statistically significant. We propose two theoretical explanations for this finding. First, the carbon reduction effects of industrial advancement exhibit a threshold characteristic that varies across development stages. As demonstrated by Yang and Liu (2025), when the share of technology-intensive industries remains below 30%, AI applications primarily focus on equipment-level intelligent retrofitting (e.g., predictive maintenance). Here, the resulting energy rebound effect may offset potential emission reductions (Yang and Liu, 2025). Indeed, efficiency improvements during this initial transition phase may actually increase carbon emissions by 5-12% due to production scale expansion (Sharma et al., 2025). Only when the share of technology-intensive industries exceeds 30% can AI facilitate systematic substitution of energy factors through knowledge factors via industrial chain restructuring (Liu et al., 2025). Notably, 78% of provinces in our sample had not reached this critical threshold, which may explain the statistically insignificant mediating effect of industrial advancement. Second, limitations in measurement methodology may have affected our results. Current industrial classification systems likely underestimate the true penetration of AI technologies. The National Bureau of Statistics reports that only 12.7% of enterprises officially classified as "technology-intensive" computer and communication equipment manufacturers have actually deployed core AI technologies (Zhang et al., 2025). This measurement error aligns with the statistical classification bias problem (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2018). Furthermore, the IEA noted that the carbon reduction effects of industrial advancement typically exhibit a three- to five-year time lag. Meanwhile, our panel data only extends through 2022, potentially missing the complete effect cycle (Cervini and Joglekar, 2025).

Moderating effect resultsTable 6 presents the results on the moderating effects of human capital and marketization in the relationship between AI and carbon emissions. As shown in Column (1), the inclusion of the interaction terms between AI, its squared term, and the level of human capital does not influence the statistically significant inverted U-shaped relationship between AI and carbon emissions. Thus, human capital exerts a moderating influence on the effect of AI on carbon emissions, thereby supporting H3a.

Moderating effect results.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| ce | ce | |

| ai | 0.992⁎⁎ | 19.775⁎⁎⁎ |

| (2.287) | (2.790) | |

| ai2 | -0.234* | -1.211⁎⁎ |

| (-1.787) | (-2.157) | |

| ai×edu | 2.024⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (2.634) | ||

| ai2×edu | -0.222⁎⁎ | |

| (-2.369) | ||

| edu | -17.825* | |

| (-1.641) | ||

| market | 2.036 | |

| (0.466) | ||

| ai×market | -0.096 | |

| (-0.298) | ||

| ai2×market | 0.042 | |

| (1.144) | ||

| gdp | -0.390 | -0.148 |

| (-1.161) | (-0.427) | |

| fdi | -0.829⁎⁎⁎ | -0.825⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-4.150) | (-4.095) | |

| is | -0.633⁎⁎⁎ | -0.590⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-9.728) | (-8.812) | |

| finance | 2.252⁎⁎ | 0.591 |

| (2.462) | (0.281) | |

| gov | -0.455 | -0.593 |

| (-1.408) | (-1.297) | |

| Spatial rho | -0.783⁎⁎⁎ | -0.721⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-4.962) | (-4.616) | |

| N | 690 | 690 |

| r2 | 0.600 | 0.240 |

Note: t statistics are reported in parentheses

The results align with the absorptive capacity theory, as human capital determines firms' ability to effectively adopt and deploy AI for environmental improvements. Highly skilled labor facilitates both the assimilation of AI technologies and their application in energy-efficient production processes (Chang et al., 2023). Moreover, the results corroborate the dual-path mechanism outlined in our theoretical framework, wherein human capital amplifies AI's carbon mitigation effects through both technological absorptive capacity and innovation diffusion. Regions with higher human capital demonstrate superior capabilities in adopting AI-driven optimizations, such as smart manufacturing systems that enhance energy efficiency (Balsalobre-Lorente et al., 2018), while fostering innovation clusters that accelerate AI applications in clean energy and smart grid technologies (Lei et al., 2025).

Regional evidence from China substantiates the moderating role of human capital in AI's environmental performance. For instance, provinces with higher human capital endowments, such as Guangdong and Jiangsu, have achieved more substantial emission reductions through AI applications in energy-intensive industries (Chen and Wang, 2023). This spatial disparity most clearly manifests at the firm level: Enterprises in these regions demonstrate 35% higher success rates in implementing AI-driven energy optimization systems compared to their counterparts in less-developed areas. This suggests a direct linkage between workforce quality and technological efficacy.

Sectoral analyses further validate this human capital threshold effect. In Jiangsu's chemical industry, the 2021 mandate for vocational AI training correlated with a 15% faster carbon intensity reduction than the national industry average (Tian and Zhang, 2025). Conversely, in human capital-scarce regions like Gansu and Ningxia, only 40% of firms successfully deployed AI-driven emission controls (Li et al., 2024), demonstrating that workforce readiness mediates AI's environmental performance. Thus, human capital plays a dual role as both a catalyst and constraint in the AI-environment nexus.

The firm-level mechanisms underlying this relationship are threefold. First, technical workforce capacity enables the effective implementation of AI. For instance, in Guangdong's manufacturing sector, AI-powered predictive maintenance systems reduced energy consumption by 12-18% annually (Lei et al., 2025). Second, educational attainment plays a pivotal role: Firms with over 60% tertiary-educated employees exhibit 25% greater AI utilization efficiency in emission control. Third, continuous skill investment amplifies these effects, with companies conducting regular AI upskilling programs and achieving 30% faster integration of smart energy management solutions (Ye et al., 2025).

Conversely, the marketization level has a statistically insignificant moderating effect on the AI-carbon emissions relationship (β = 0.12, p > 0.1). Thus, Hypothesis H3b is not supported. This is contrary to conventional expectations that market forces would enhance AI's environmental benefits through competitive pressures and efficient resource allocation. In China's current transitional economy, marketization alone may be insufficient to amplify AI's carbon reduction effects (Xu and Huang, 2024). Theoretically, this insignificant moderating effect stems from two fundamental market failures. First, environmental externalities remain inadequately priced in market transactions. Carbon emissions rarely reflect their true social costs in China's emerging carbon markets (Stiglitz, 2019). Second, environmental innovation diffusion theory indicates that market mechanisms require mature commercialization pathways to be effective. This condition remains unmet for most AI-based emission control technologies, which remain in pilot stages with limited scalability (Stavins, 2005).

Three distinctive factors in China's institutional environment further constrain marketization's moderating role. First, the predominance of command-and-control environmental regulations (e.g., mandatory emission targets) overshadows market-based instruments, reducing variation in corporate responses across regions with different marketization levels (Zhu and Wang, 2024; Rasheed et al., 2024). Second, China's fragmented carbon trading system, with significant regional disparities in carbon pricing and coverage, fails to provide consistent market signals to guide AI adoption (Gan et al., 2024). Third, the commercialization level of environmental AI applications remains relatively low (Ayinaddis, 2025), indicating that demand-pull effects have yet to reach significant scale. These unique circumstances collectively create a distinctive analytical context where marketization indicators, despite their theoretical relevance, lose explanatory power in empirical analysis.

Robustness testSeveral robustness tests were conducted to validate the robustness of the aforementioned results. First, the spatial weight matrix was substituted with an economic-geographical nested matrix. The results are presented in Table 7. Column (1) assesses the influence of AI on carbon emissions, yielding regression outcomes that align closely with those reported in Table 4. Columns (2) and (3) examine the impact of AI on industrial rationalization and advancement, respectively. The findings remain largely consistent with those in Table 5. Furthermore, Columns (4) and (5) evaluate the effect of AI on carbon emissions after incorporating industrial rationalization and advancement as mediating variables. The results reaffirm the earlier findings. Finally, Columns (6) and (7) test the moderating roles of human capital and marketization levels, with results that corroborate the patterns observed in Table 6.

Robustness test results: Using the replacement space weighting matrix.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ce | isr | isu | ce | ce | ce | ce | |

| ai | 7.761⁎⁎⁎ | 0.006⁎⁎ | 0.025⁎⁎⁎ | 9.625⁎⁎⁎ | 7.260⁎⁎⁎ | -2.403 | 16.862⁎⁎ |

| (3.264) | (2.182) | (2.576) | (2.589) | (3.047) | (-0.625) | (2.381) | |

| ai2 | -0.484⁎⁎⁎ | -0.325* | -0.457⁎⁎⁎ | 0.359 | -1.144⁎⁎ | ||

| (-2.796) | (-1.677) | (-2.644) | (1.081) | (-2.057) | |||

| isr | -34.018⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||

| (-4.174) | |||||||

| isu | 3.267 | ||||||

| (1.447) | |||||||

| ai × edu | 2.140⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||

| (2.580) | |||||||

| ai2 × edu | -0.244⁎⁎ | ||||||

| (-2.343) | |||||||

| Ai × market | -0.026 | ||||||

| (-0.082) | |||||||

| ai2 × market | 0.044 | ||||||

| (1.239) | |||||||

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Spatial rho | -0.050 | 0.098⁎⁎ | 0.000 | -0.147⁎⁎⁎ | -0.063 | -0.104 | -0.051 |

| (-0.962) | (1.972) | (0.009) | (-2.711) | (-1.191) | (-1.380) | (-0.879) | |

| N | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 |

| r2 | 0.038 | 0.740 | 0.840 | 0.003 | 0.065 | 0.004 | 0.030 |

Note: t statistics are reported in parentheses

Finally, an additional robustness check was performed by adopting per capita carbon emissions as an alternative indicator for carbon emission levels. The results are detailed in Table 8. The estimated coefficients on the influence of AI on carbon emissions in Column (1) align with those reported previously in Table 4. Subsequently, Columns (2) and (3) replicate the mediation analysis focusing on industrial rationalization and industrial intensification, consistent with the approach used in Table 7. Again, industrial rationalization continues to exhibit a statistically significant mediating role, whereas industrial intensification does not. Finally, Columns (6) and (7) examine the moderating roles of human capital and the degree of marketization. The results remain consistent with those presented in Table 6.

Robustness test results: Replacing explanatory variables.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pco2 | pco2 | pco2 | pco2 | pco2 | |

| ai | 2.032⁎⁎⁎ | 2.032⁎⁎⁎ | 2.041⁎⁎⁎ | 1.826⁎⁎⁎ | 3.861⁎⁎⁎ |

| (8.623) | (8.612) | (8.652) | (5.421) | (7.435) | |

| ai2 | -0.110⁎⁎⁎ | -0.110⁎⁎⁎ | -0.110⁎⁎⁎ | -0.055⁎⁎ | -0.258⁎⁎⁎ |

| (-8.828) | (-8.771) | (-8.849) | (-2.372) | (-6.435) | |

| isr | 0.389⁎⁎ | ||||

| (2.731) | |||||

| isu | 0.117 | ||||

| (0.862) | |||||

| ai×edu | 0.130⁎⁎ | ||||

| (2.122) | |||||

| ai2×edu | -0.021⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| (-3.188) | |||||

| ai×market | 0.103⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| (4.565) | |||||

| ai2×market | -0.011 | ||||

| (1.387) | |||||

| Control variables | Control | Control | Control | Control | Control |

| Spatial rho | -0.144* | -0.144* | -0.142* | 0.174⁎⁎ | -0.096⁎⁎ |

| (-1.814) | (-1.816) | (-1.806) | (2.270) | (-2.553) | |

| N | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 | 690 |

| r2 | 0.207 | 0.307 | 0.106 | 0.300 | 0.220 |

Note: t statistics are reported in the parentheses

This study examines the evolving interplay between carbon emissions and AI development across urban areas in China. The three primary findings are summarized below:

- (a)

AI development and carbon emissions have an inverted U-shaped relationship, with the inflection point occurring when provincial AI enterprise density reaches 12.57 firms per 10,000 km². The threshold marks a critical transition in regional AI development from an expansion in scale phase to an increase in quality phase, reflecting the tipping point in technology diffusion where quantitative changes yield qualitative transformation. Specifically, before reaching the threshold, AI growth remains predominantly resource-input driven, exhibiting higher energy consumption intensity. However, beyond the inflection point, technological optimization and green computing applications substantially reduces energy consumption per unit GDP, with emission reduction effects becoming progressively evident. These findings provide new empirical evidence for understanding AI's environmental impacts, demonstrating that the technology's decarbonization potential can only be fully realized upon reaching a critical maturity level.

- (b)

Next, industrial upgrading has differentiated mediating effects in the relationship between AI and carbon emissions. Specifically, the industrial rationalization pathway demonstrates statistically significant mediating effects, where AI promotes emission reductions by optimizing production processes and improving resource allocation efficiency. This finding aligns with China’s tiered policy framework for AI development, which has accelerated AI adoption rates in key industries. Conversely, the industrial advancement pathway does not exhibit significant mediating effects. This may primarily be because of two aspects: insufficient AI penetration, leading to energy rebound effects in AI applications; and inherent time lags in the current deployment of AI technologies and their corresponding emission reduction effects.

- (c)

Finally, human capital and marketization levels have heterogeneous moderating effects in AI’s impact on carbon emissions. First, human capital has a positive moderating effect, demonstrating that human capital enhances AI’s marginal emission reduction effects by improving technology absorption and innovation diffusion efficiency. Conversely, the moderating effect of marketization is statistically insignificant. This is primarily due to market failures, such as inadequate pricing of environmental externalities and immature commercialization pathways for emission reduction technologies, and institutional constraints, including mandatory emission targets and fragmented regional carbon markets.

First, a multi-tiered support system for AI technological innovation should be established. At the policy formulation level, the National Development and Reform Commission should spearhead the development of a "Roadmap for AI-enabled Carbon Reduction Technologies," prioritizing R&D in key areas, such as smart grid dispatch and industrial process optimization, which being supported by a dedicated fund. At the industrial implementation level, "AI+Industrial Internet" innovation hubs should be established in manufacturing clusters like the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas, featuring sector-wide digital twin platforms for energy consumption monitoring. Finally, at the enterprise level, a "Three-Year AI Energy Efficiency Retrofit Plan" should be implemented for key energy-consuming enterprises whose annual comprehensive energy consumption exceeds the standard. This includes offering corporate income tax deductions on equipment investments while mandating integration with provincial energy monitoring systems.

Second, differentiated pathways for industrial transformation and upgrading should be developed. At the policy formulation level, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology should revise the "Green Industry Guidance Catalog" to create a separate category for AI-driven clean production technologies, setting a binding target of improvement in manufacturing intelligentization by 2025. At the industrial implementation level, pilot programs for "Intelligent Green Industrial Transformation" should be launched in regions like Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and Chengdu-Chongqing, establishing traceability platforms for carbon footprints in key industries. Finally, at the enterprise level, an "AI Carbon Reduction Star Rating System" should be introduced, granting enterprises with three-star ratings in emissions trading and green financing.

Third, a systematic talent development program should be implemented. At the policy formulation level, the Ministry of Education, in collaboration with the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, should launch a "Digital Talent for Dual Carbon Goals" initiative. Under this initiative, intelligent environmental protection programs should be established in a selected number of vocational colleges, with the aim of training a substantial cohort of skilled technicians within a defined period. At the industrial implementation level, "Green AI Training Bases" should be set up in national innovation demonstration zones, with participating enterprises in the carbon market encouraged to host a meaningful number of interns each year. At the enterprise level, corporate investment in AI skills training should be incorporated into environmental tax reduction criteria. Enterprises that allocate a certain percentage of their revenue to training should qualify for an additional reduction in corporate income tax.

Fourth, market-driven emission reduction incentives should be strengthened. At the policy formulation level, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment should integrate AI carbon reduction credits into the national carbon market, allowing certified AI-driven emission reductions to offset a certain proportion of corporate carbon quotas. At the industrial implementation level, pilot "AI Carbon Reduction Algorithm Trading Platforms" should be established in selected major cities, utilizing blockchain for the verification and trading of emission reductions. At the enterprise level, commercial banks should be encouraged to offer green loans at preferential interest rates below the standard lending rate to enterprises achieving significant annual emission reductions through AI, with priority given to carbon-neutral bond issuance quotas.

LimitationsFirst, although the absolute number of AI enterprises helps capture cluster-based economic influences, this metric may inadequately reflect technological depth or innovation quality, potentially leading to measurement errors. To prioritize the examination of agglomeration effects, this study employs the absolute count rather than normalized relative indicators. This helps mitigate the confounding biases arising from population or economic fluctuations. However, this approach may also result in a slight overestimation of AI’s impact in larger provinces. Second, while the spatial Durbin model helps control for spatial dependence and partially addresses endogeneity issues, endogeneity challenges arising from bidirectional causality and selective bias in technology diffusion still remain in assessing AI’s carbon reduction effects. Third, although the mixed-methods approach combining macro-econometric analysis with micro-level text mining enhances the robustness of conclusions, the validation of micro-level mechanisms at the enterprise level remains insufficient. In particular, in-depth case studies tracking the technology adoption pathways of representative firms are few.

Future research can construct a multidimensional AI development indicator system that integrates big data sources, such as patent text mining, and computing infrastructure to establish a more precise framework for assessing technological maturity. Next, dynamic spatial panel models and instrumental variable methods can be employed to systematically examine the temporal patterns of AI's emission reduction effects, with particular attention to potential lagged impacts. Third, a "macro-meso-micro" tri-level validation framework can be developed, especially through longitudinal case studies of leading firms in key industries. Here, quantitative assessments of production process transformation can be combined with qualitative interviews on management decision-making to enable more comprehensive and detailed investigations.

CRediT authorship contribution statementXiaohua Zhou: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yuchen Zou: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yihuan Ding: Visualization, Validation, Resources.

To analyze the orientation and evolution of provincial artificial intelligence policies, a specialized text corpus was constructed, covering 31 provincial-level administrative regions in mainland China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan).

Data Sources:

- •

Official portals of provincial people’s governments: The policy directions related to AI development across provinces were first systematically reviewed. The initial keywords such as "artificial intelligence," "smart industry," "robotics," "big data," "data governance," "machine learning," "technology application," and "infrastructure" were identified as core search terms. The retrieved policy texts were further analyzed to those closely related to AI development, ensuring the corpus’ representativeness and relevance.

- •

The PKULAW database was used as the primary source for policy text collection. As an authoritative platform specializing in Chinese laws, regulations, and policy documents, it provided a comprehensive and reliable foundation of the sampled policy texts.

Collection Process and Inclusion Criteria:

- •

Timeframe: January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2022.

- •

Document Types: Collected documents include plans, guidance opinions, action plans, and implementation schemes formally issued by provincial governments, their general offices, or relevant departments (e.g., Departments of Science and Technology, Industry and Information Technology, and Development and Reform Commissions). News articles, speeches, and provisional measures were excluded due to their limited enforceability or non-strategic nature.

- •

Final Corpus: After manual screening and deduplication, 487 valid policy texts were included, forming the study’s analytical foundation.

Text Preprocessing and Tokenization:

- •

Text Cleaning: Text was extracted from original PDF or HTML formats, with non-body content such as headers, footers, tables, and appendices removed.

- •

Chinese Word Segmentation: The jieba word segmentation toolkit was employed. A custom dictionary incorporating domain-specific terms, such as "computing infrastructure," "algorithm innovation," "smart manufacturing," "data governance," and "ethical governance," was added to enhance segmentation accuracy.

- •

Stop Word Filtering: Besides the standard Harbin Institute of Technology stop word list, a custom stop word list was created to filter out high-frequency but meaningless terms commonly found in policy texts (e.g., "provinces," "autonomous regions," "people's government," "notice," "requirements," and "conscientiously implement"). This step helped focus the analysis on substantively meaningful vocabulary.