This paper advances our understanding of the transformative role of innovation in labor share dynamics over recent decades of rapid technological evolution. We introduce a novel methodology to disentangle the direction and substitution effects of technological change, drawing on comprehensive Penn World Table (PWT) data across 136 countries from 1991 to 2019. The findings reveal notable temporal and spatial variability, challenging fixed-parameter assumptions within traditional production functions. Key insights include: (i) developed economies exhibit a labor-oriented direction of technological change compared with developing countries; (ii) there is a pivotal shift from capital-augmenting to knowledge-augmenting technological paths in developed economies; (iii) there is a persistent complementarity between capital and labor. These results suggest that labor-oriented technological advancements are boosting labor share growth, especially in knowledge-driven economies. Finally, we explore the profound implications of these findings for political and corporate strategy.

The dynamics of the labor share are puzzling, and their examination has emerged as a focal point in the economics of innovation and knowledge (Gil-Alana et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022). Throughout much of the last century, economists tended to view this variable as constant (Kaldor, 1961; Keynes, 1939), consistently assuming that technological change was neutral. In the latter part of the century, empirical evidence on the sharp changes in the shares of inputs in income prompted a reconsideration of the neutrality assumption (Solow, 1958; Blanchard, 1997).

The observation of non-neutral technological change requires a precise distinction between key concepts that describe its direction and effects. Technological bias refers to the systematic tendency of innovation to favor one production factor over another, altering the factor shares. Factor intensity indicates the extent to which a given technology relies more on one input factor than the other. In contrast, augmenting technological change reflects a dynamic shift that enhances the productivity of a specific input factor. For instance, a country adopting capital-intensive technology is leveraging technology that predominantly utilizes capital rather than labor. If technological change is also capital-augmenting, this trend is further reinforced. However, if technological change is labor-augmenting, it signals a shift that increases labor productivity relative to capital, even if the technology itself could remain capital-intensive.

By the turn of the century, a strong consensus emerged around the traditional biased technological change approach, which posited that technological change would be directed towards the intensive use of capital due to the secular reduction in capital user costs. Both theoretical and empirical evidence supported the hypothesis that the direction of technological change was capital-intensive (Acemoglu, 2002a; Bentolila & Saint-Paul, 2003; Bassanini & Manfredi, 2014; Karabarbounis, 2024). Recently, the literature began to highlight a new global trend: the increasing labor share and a shift towards a labor-intensive direction of technological change (O'Mahony et al., 2021; Ugur, 2024; Steher, 2024; Antonelli & Feder, 2020, 2021a, and 2021b).

The empirical data have evolved in accordance with this research, weaving a rich and intricate tapestry that demands even more thorough exploration. Scholars are now exploring the underlying causes behind this puzzling evidence (Autor et al., 2020; De Loecker et al., 2020). Among others, technological change emerges as a crucial element in understanding these dynamics (Stockhammer, 2017; Yasar & Rejesus, 2020). Indeed, these changes in labor share directly result from technological change through both the introduction of directed technological change, which alters the output elasticity of production factors, and the technological complementarity of production factors, which affects their elasticity of substitution and accelerates the structural transformation that reshapes the sectoral composition of advanced economies.

The methodology introduced in this paper provides fresh evidence of this labor-augmenting shift by disentangling the effects of the new direction while accounting for changes in the elasticity of substitution. These two aspects of technological change are closely intertwined. However, the literature has traditionally focused on one aspect at a time, with a minimal attempt to analyze them together. The literature on induced technological change based upon the Cobb-Douglas (CD) production function approach relies on Euler's theorem and utilizes the labor share to estimate the output elasticity (Hicks, 1932; Acemoglu, 2002b and 2015; Feder, 2022) and subsequently gauges the direction of technological change. In contrast, the constant elasticity of substitution (CES) literature predicts an indissoluble link between labor share and elasticity of substitution (Arrow et al., 1961; Piketty & Zucman, 2014; Ballestar et al., 2021; Menga & Wang, 2023) and, consequently, on the technological complementarity of inputs. However, the utilization of a CES production function necessitates the assumption of constant factor income shares.

In summary, studies relying on standard production functions overlook two important changes that have occurred in developed economies over recent decades: the change in the elasticity of substitution within countries (Mallick, 2012; Knoblach et al., 2020; Knoblach & Stöckl, 2020; Ialenti & Pialli, 2024), and the endogenous direction of technological change in a global economy characterized by competition in quite homogeneous product markets between rivals based in heterogeneous factor markets (Goos et al., 2014; Acemoglu, 2015).

This paper bridges these two bodies of literature by introducing a novel procedure to disentangle the effects of technological change on labor share. By applying this method to Penn World Table (PWT) national accounts, we obtain comprehensive evidence on the determinants of labor share dynamics across 136 countries from 1991 to 2019. All variables exhibit significant variability over time and space, highlighting the inadequacy of production functions that assume invariant output elasticities and elasticity of substitution (Pereira, 2003; Palivos, 2008; Bellocchi & Travaglini, 2023).

The proposed disentangling procedure is versatile and straightforward, enabling its application to a diverse range of countries, including those facing poverty. These countries are typically the most challenging to monitor, despite their critical relevance to income inequality and quality of life. The general applicability of this approach enhances global comparability and provides a broader view of macro-level technological trends. Although there is significant heterogeneity in the results, our findings suggest that three major shifts have emerged: (i) a decline in the labor-intensive direction of technological change in developing countries; (ii) a recent reversal of this trend in developed countries; and (iii) a rise in the elasticity of substitution observed across most countries.

The suggested decoupling technique explains how the two dimensions of technological change interact to affect the labor share, aiming to clarify its complex path. Indeed, the increase in the elasticity of substitution can mask the simultaneous introduction of labor-intensive technologies. Indeed, both theoretically and empirically, the two components of the labor share tend to offset each other. This makes the labor share to appear relatively stable despite significant hidden technological changes shaping both the labor market and income distribution. These two facets of technological change may either amplify or mitigate each other.

All the evidence of this paper regarding the global dynamics of the labor share and the role of the elasticity of substitution calls into question both the CD and CES production functions, suggesting the development of a new methodological framework to appreciate the joint effects of the changing levels of output elasticity and elasticity of substitution.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the disentangling procedure for determining the direction and substitutability of technological change. Section 3 provides a detailed descriptive analysis of the empirical evidence. Section 4 presents an interpretative framework. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the results and highlights the main policy and managerial implications.

Partitioning methodologyThe literature has developed the CD and the CES production functions to estimate, respectively, the output elasticity of productive factors and their elasticity of substitution. However, the CD production function identifies the output elasticity only under the constraint that the elasticity of substitution always equals 1, and factor shares cannot differ from their output elasticities. Conversely, the CES production function identifies the elasticity of substitution at the cost of assuming constant levels of factor income shares (Blanchard, 1997; Ialenti & Pialli, 2024).

Assuming constant returns to scale, where each factor is remunerated based on its marginal productivity without any residual effects, the standard microeconomic theory asserts that, with a CD production function, the labor compensation share in GDP is equivalent to the output elasticity of labor. Conversely, with a broader CES production function, the empirical labor compensation share in GDP serves as the distribution parameter.

Its determination is contingent upon a specific level of elasticity of substitution, denoted as σ. When σ is equal to 1, the CES production function assumes the structure of a CD function, leading to the labor share being equivalent to the output elasticity of labor. Otherwise, in a capital-abundant country where the elasticity of substitution is greater (less) than 1, the labor share is higher (lower) than the output elasticity of labor. The Appendix provides a demonstration of this relationship and reverses the result for labor-abundant countries, although the PWT data show that all countries are capital-abundant. Intuitively, in capital-abundant countries, the labor share decreases due to the technological substitution of labor with capital, unless labor and capital are highly complementary (i.e., the elasticity of substitution is low). Conversely, in labor-abundant countries, the labor share increases as capital is substituted with labor, and this effect is stronger when the two inputs are substitutes.

The standard CES production function, which aggregates productive factors between capital (K) and labor (L), assumes the following form:

where Y is the GDP; A is the TFP; L is the labor; K is the capital; σ=1/(1−ρ) is the elasticity of substitution; and β is the empirical labor compensation share in GDP.The standard approach to estimating the CES production function is via the normalization method (Klump et al., 2012), which presents several advantages in parameter identification and estimation, including the elasticity of substitution. Irrespective of the integration of factor-augmenting technical change, in this procedure, both capital and labor shares are fixed to their national accounting equivalents under the assumption of perfect competition. Therefore, the labor share value can be directly derived through standard national accounting practices and equals the labor compensation share in GDP, which is defined as the total labor compensation over the national income. This empirical labor share indicates the proportion of output allocated to employee compensation compared with the share designated for capital, and it is mathematically expressed as:

where w is the unitary cost of labor.Vice versa, with a CD production function:

the optimal allocation of factors is derived from its equilibrium solution:where r is the unitary cost of capital.It is thus feasible to compute the labor share value in the CD production function, βCD, as follows:

Assuming a CD production function and the validity of Euler's theorem, this theoretical labor share could also be interpreted as the output elasticity of labor. Its changes might be regarded as the outcome of the introduction of directed technological change. If βCD>(<)0.5, it indicates a (capital-) labor-intensive direction of technological change. Furthermore, an increase (decrease) in the output elasticity of labor, ΔβCD>(<)0, denotes a (capital-) labor-augmenting technological change.

If the elasticity of substitution is equal to 1, σ=1, the two production functions yield the same labor share over GDP, β=βCD. Otherwise, as described in the Appendix, in capital-abundant countries, if β>(<)βCD, then σ>(<)1. Consequently, when K>L, there is an extra component of the labor share, denoted as βσ which serves as a proxy for the elasticity of substitution and can be calculated by comparing (2) and (5):

The difference between the CD and the empirical labor shares serves as a reliable measure of the effects of the changing levels of the elasticity of substitution. Indeed, when, in capital-abundant countries, the technology makes production factors substitute (complement), the elasticity of substitution is larger (lower) than 1, σ>(<)1, and the labor share is larger (smaller) than the output elasticity of labor, βσ>(<)0. Therefore, elevating positive (negative) values of the extra component of the labor share, Δβσ>(<)0, indicates a trend where labor increasingly substitutes (complements) capital.

The derivation of (4)–(6) relies on the assumption of constant returns to scale and equilibrium in both factor and product markets, as embedded in the production function (3). However, besides changes in the elasticity of substitution, the unexplained component of the labor share may stem from either departures from equilibrium in factor markets or non-constant returns to scale. In the Appendix, we demonstrate that the behavior of the elasticity of substitution closely mirrors that of the residual labor share, suggesting that variations in the elasticity of substitution are the predominant factor. Consequently, while departures from equilibrium or non-constant returns to scale might have some impact, their influence appears marginal in comparison. This finding could suggest that economic systems are not perpetually out of equilibrium but rather are characterized by continuous change. An alternative view is that the effects of market disequilibrium and variable returns to scale are more strongly reflected in the TFP measure than in the labor share. Although these explanations may not hold uniformly across all industries or countries, they underscore the necessity for production functions that can dynamically adjust to evolving technological components.

In this paper, we implicitly associate technological change with technological advancements, though the interpretation can be broader. Indeed, there are three additional possible interpretations, each complementary to innovation: (i) structural change driving alterations in production or sectoral mixes; (ii) out-of-equilibrium conditions; and (iii) other exogenous factors, such as institutions or the labor force size. While all these variables contribute to explaining the labor share, moving forward, technological change will be broadly interpreted as productivity change, encompassing all these factors together. Furthermore, both the Appendix and the literature on induced technological change make clear that technological change affects both the output elasticity and the substitutability of production factors, together explaining almost all the variability in the labor share.

The proposed methodology becomes increasingly relevant as the scope of technological change expands. In line with the Schumpeterian legacy, our analysis views technological change as encompassing not only the introduction of new products and processes but also the adoption of new inputs, entry into new markets, and, importantly, the development of new models of management and labor organization within firms, along with shifts in the sectoral composition of an economic system. The proposed methodology offers significant advantages. Firstly, its remarkable simplicity of estimation facilitates the measurement of the two components of the labor share across a wide range of scenarios. For instance, it allows for the refinement of the granularity of previous analyses. Secondly, this methodology combines an overall measure of both elasticity (output and substitution) levels and their impact on labor share. This double nature enables, for instance, the measurement of the importance of each productive component and their comparison.

Empirical analysisDatabaseAll previously described measures can be readily empirically computed for a diverse array of countries and years by utilizing the standard data of the PWT version 10.01 (Feenstra et al., 2015). Specifically, we leverage the following variables: the labor compensation share in GDP at current national prices (β); the output-side real GDP at current PPPs in millions of 2017 US Dollars (Y); the number of persons engaged in millions (L); the capital stock at current PPPs in millions of 2017 US Dollars (K); and the real internal rate of return (r).

Regrettably, a genuinely dynamic estimate of the labor compensation share in GDP only becomes available with the advent of the new generation of PWT countries (Feenstra et al., 2013; Inklaar & Timmer, 2013). Consequently, we propose a comprehensive database encompassing 136 countries spanning 1991 to 2019 (i.e., when nearly all countries exhibit varying labor share values over time). Table 2 enumerates the countries.

From a global perspective, 1991 marks the beginning of a period characterized by increased globalization and the emergence of transformative technologies. Indeed, the early 1990s can be regarded as the start of intense globalization and the advent of groundbreaking innovations such as the Internet, mobile communications, and digital computing, which have since re-defined the world economy. This enables our analysis to focus on the dynamics of labor markets and technological change from their early stages.

The labor share is a valuable metric for observing its actual value (β)and the unitary wage (w). Indeed, from (2), the wage level is directly defined as:

Consequently, (5) and (6) allow us to quantify the labor share in a CD production function (βCD) and the extra labor share (βσ). The first focuses on output elasticity, while the second offers valuable insights into the level of the elasticity of substitution. Both elements are intimately tied to technological advancements, providing an accurate measure and a more profound comprehension of temporal and spatial economic transformations. Remember that when βCD is greater (or less) than 0.5, technologies are labor- (or capital-) intensive. This means that if βCD>0.5, labor productivity is higher than capital productivity, and vice versa. Moreover, if βCD increases (or decreases), the technological change is labor- (or capital-) augmenting, meaning that it enhances the productivity of labor (or capital). Finally, in capital-abundant countries, where K/L>1, if βσ is less (or greater) than 0, technology makes labor complementary (or substitutive) to capital.

To analyze the temporal and spatial variability of the derived labor share components, we used panel data. For each country and year, the PWT database directly provides the labor compensation share in GDP (β), the unitary cost of capital (r) derived from the real internal rate of return, and the labor-capital ratio (K/L) based on the capital stock and the number of persons engaged. The elasticity of substitution (σ) was then implicitly derived using the relationship outlined in the Appendix. Finally, the labor share under the Cobb-Douglas assumption (βCD) and the extra labor share (βσ) were computed directly from eqs. (5) and (6), respectively. Our analysis primarily examines the evolution of these derived measures and their cross-country variations, offering insights into the changing nature of technological progress without imposing fixed parameters, as is often done in traditional production function estimations.

Table 1 presents the main descriptive statistics for all the variables under consideration. The last three rows are of particular importance for our objectives. Notably, the mean, variability, and range of values for labor share in the CD production function (βCD) exceed those observed in the empirical labor share (β). These overall traits suggest that the key to understanding the levels and effects of the elasticity of substitution over the empirical labor share tends to be negative and heterogeneous. Consequently, the global elasticity of substitution is, on average, below unity, implying that capital and labor are complementary. Additionally, it becomes apparent that βσ cannot be reconciled with the output elasticity levels derived from the equilibrium Cobb-Douglas (βCD). Finally, the variability and magnitude of the three values (β, βσ, and βCD) underscore the importance of the topic, which we will now explore in greater detail.

Descriptive statistics.

Source: PWT 10.01 and our own elaboration.

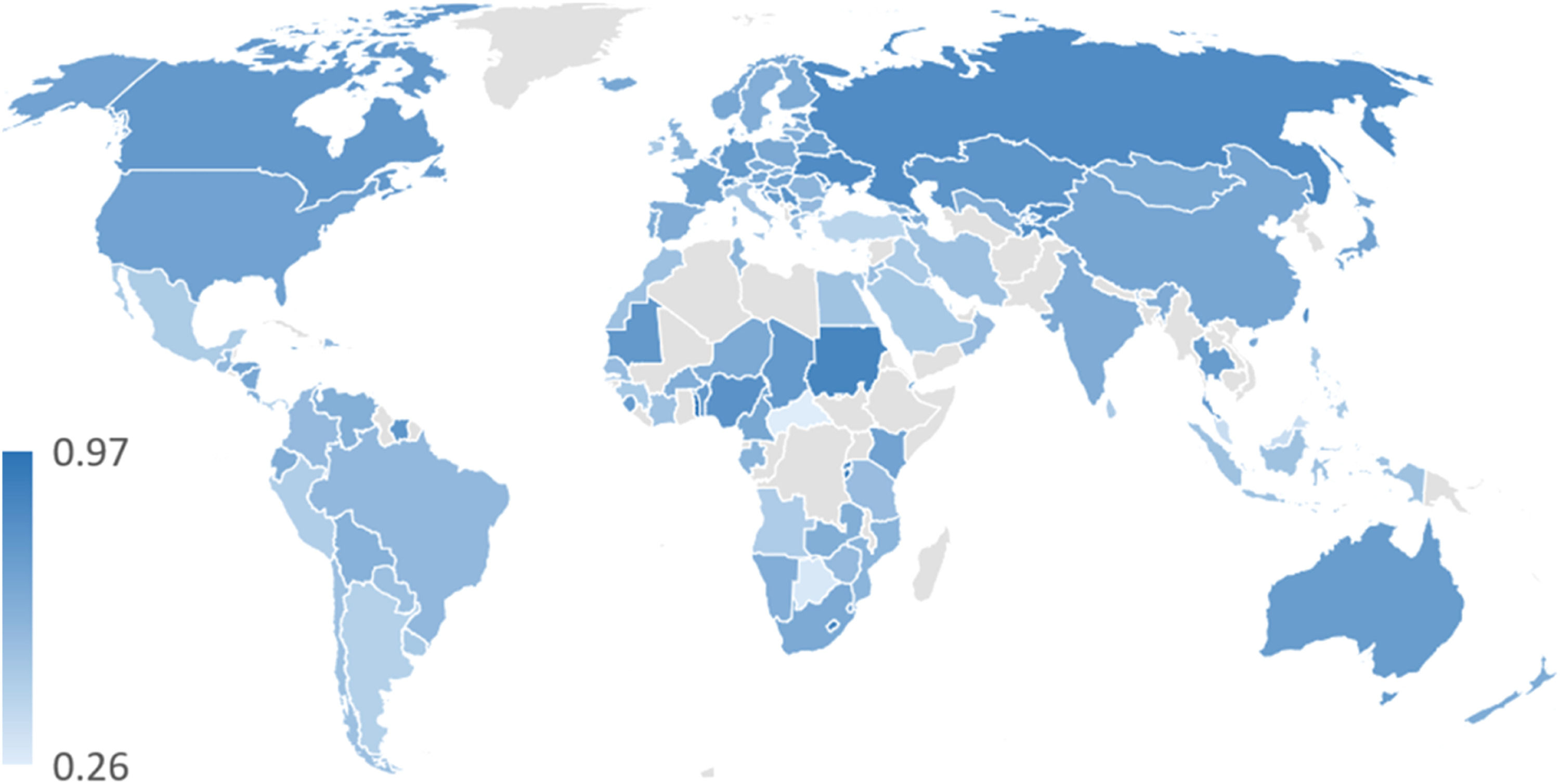

Fig. 1 depicts the spatial heterogeneity of the average values of labor share for the 136 countries under consideration. The shading intensity corresponds to the magnitude of the values, with darker shades indicating higher values. Notably, North America stands out with significantly high labor shares. In Central and South America, labor share tends to be comparatively lower. However, certain countries like Ecuador or Jamaica exhibit values comparable to those of Canada and the United States, which is difficult to explain without delving into the composition of the labor share. In Europe, values are generally moderately elevated, with the remarkable exception of Ireland. Australia and New Zealand showcase values on a par with Europe, while the rest of Oceania displays lower values. Similarly, in Asia, most countries have upper-mid range values of labor share (e.g., China, India, Russia, and Thailand), although others exhibit low labor shares, particularly in the Arabian Peninsula. Even in Africa, labor share tends to be low overall, but significant outliers exist, such as Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan, and Togo, which boast some of the highest labor shares globally.

Fig. 2 shows the average labor share over 29 years. The central line depicts the mean values of the labor share for each considered year. The dynamics analysis reveals that the labor share experienced a general decline until 2006, when it stopped. Since 2011, the global labor share has slightly reversed its trend. A similar trend is observed for non-OECD countries (the lighter line). Notably, the labor share in these countries consistently lags behind the average. Indeed, despite the more pronounced U-shape, the labor share remains low and just below 0.5. Conversely, OECD countries (the darker line) demonstrated a consistently higher average labor share throughout the entire period, always larger than 0.55. Additionally, the declining trend was less pronounced, while in recent years, there has been a gradual increase in the labor share.

The evidence on dynamics suggests that, over the past 29 years, the labor share has followed a U-shaped trend in both OECD and non-OECD countries. It is crucial to ascertain whether this trend results from the new labor-augmenting direction of technological change and to assess whether the dynamics of the elasticity of substitution reinforce or weaken it.

The labor output elasticityFig. 3 replicates Fig. 1 and represents the spatial distribution of the average output elasticity of labor. While the top-six countries with the highest values of average labor output elasticity are all located in subtropical regions, it is noteworthy that countries in the northern hemisphere generally exhibit far larger values than their southern counterparts. This evidence starkly contradicts the prevailing theory. Indeed, the labor output elasticity is significantly higher in countries where capital is supposed to be abundant relative to labor and vice versa. Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Switzerland, and Ukraine register the highest values above the Tropic of Cancer. Additionally, China, North America, and several European nations also display notable levels of average output elasticity. Conversely, certain European countries (e.g., Italy, Greece, and Ireland), Central America, and the Middle East show, on average, lower output elasticities of labor, resembling those found in sub-equatorial countries. In summary, traditional theories of directed technological change ‒ which argue that technological change should shift towards a capital-augmenting direction due to the secular decline in capital user costs and the relative rise in wages ‒ appear to hold true only for a limited number of less-developed countries.

This cross-sectional solid evidence suggests that the output elasticity of labor and, hence, the labor intensity of technology are stronger in countries where wages and revenue per capita are larger. Like Fig. 2, Fig. 4 illustrates the evolution of the analyzed variable, in this case, the average output elasticity, 1991-2019. The global trend (the central line) declines from 0.65 to 0.56. The trend was even more striking for non-OECD countries (the lighter line), experiencing a drop of over ten percentage points. A more intricate pattern emerged for OECD countries. In the early 1990s, the decline was most pronounced, but there was a recovery around the turn of the century, reaching its highest average value in 2002 (0.658). In the subsequent years, it followed the global decreasing trend. However, since 2014, labor output elasticity has resumed growth.

The theory of directional technological change effectively elucidates the non-OECD trends depicted in Fig. 4. Specifically, developing countries showcase labor-intensive, βCD>0.5, but capital-augmenting, ΔβCD<0, technologies. Conversely, the OECD trends present a somewhat surprising pattern: (i) technological change is, on average, more labor-intensive than in developing countries; (ii) technological change has been labor-augmenting at least since 2014.

The elasticity of substitutionFig. 5 displays the average extra labor share values ‒ our clue of the elasticity of substitution ‒ across various countries. The dynamics of the extra labor share confirm that the elasticity of substitution changes considerably across countries and over time and exhibits high levels of variance (Bellocchi & Travaglini, 2023). Except for Oceania, each continent includes at least one country which displays a positive value, indicating an elasticity of substitution larger than 1. However, only 17 nations exhibit a positive average value: Argentina, Bahrain, Botswana, Cayman Islands, Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lao People's DR, Luxembourg, Macao, Malta, Portugal, Singapore, Turkey, and Uruguay. In these countries, the elasticity of substitution is above 1 (i.e., they employ technologies that support the enhanced substitutability between capital and labor). In these cases, firms introduce new technologies that enable them to better react in the substitution process: when wages increase, firms can sharply reduce employment levels.

In the remaining 119 scrutinized countries, the elasticity of substitution is smaller than 1 (i.e., they employ technologies that support the complementarity between capital and labor). In other words, the increase in either factor's cost results in a corresponding rise in its income share without any change in its output elasticity. Nevertheless, the negative average extra labor share values are not particularly substantial in (North and South) America and Europe. A similar pattern emerges in Oceania and Asia, from China downwards. In contrast, the average extra component of the labor share is notably negative in the remaining Asian countries and Africa. This likely stems from the fact that, in more developed countries, labor is highly skilled and tends to be more flexible and adaptable, reducing the relevance of complementarity with capital compared with workers in developing countries.

Symmetrical to Figs. 2 and 4, Fig. 6 shows the temporal variations in the extra component of the labor share. The values are consistently negative, supporting an elasticity of substitution lower than 1 not only spatially but also temporally. However, the global trend (represented by the central line) is on an upward trajectory over the analyzed period, indicating an increase in the elasticity of substitution. In other words, while technologies facilitate the swift complementarity between production factors, this capability is decreasing over time. It is worth noting that the new pattern has been consolidating at the turn of the century. Similar trends are evident for non-OECD countries, although their average values are always lower than the global average. Conversely, in OECD countries, the trend takes a U-shape, with mid-1990s values not differing significantly from those in 2019.

This analysis provides direct insights into the levels and rates of change in the elasticity of substitution ‒ a crucial and key technological aspect ‒ across countries and over time. In general, our results align with the most recent empirical literature that observes an elasticity of substitution lower than 1 (Mallick, 2012; Federici & Saltari, 2016; Chirinko & Mallick, 2017; Oberfield & Raval, 2021), although there are notable exceptions. The analysis of Figure 6 reveals four significant and somewhat surprising findings: (i) capital and labor are complementary production factors; (ii) overall, the levels of the elasticity of substitution have increased over time; (iii) developing countries exhibit a lower degree of technological complementarity between factors compared with developed ones; and (iv) since the end of the last century, the elasticity of substitution trend has become convex, particularly in non-OECD countries.

Indeed, in OECD countries, the transition to a knowledge economy, where labor is the pivotal element, is already underway. Moreover, efficiency wages and labor hoarding are becoming commonplace practices in many countries, exerting a positive impact on the elasticity of substitution and, consequently, boosting the labor share (Stiglitz, 1976; Arif, 2021; Acemoglu, 2015).

It is intriguing to note that this same U-shaped pattern is mirrored in the labor share trend. Indeed, initially, technologies that diminish complementarity between factors facilitate the capital-augmenting direction of technological change, particularly in non-OECD countries. In recent years, a new trend has been found in OECD countries: the degree of complementarity among productive factors is rising. This (extra) component reduces the growth in the OECD's labor share but is insufficient to reverse its path, driven by labor-augmenting technological changes.

The following subsection will further explore the comparison between the two technological components of labor share.

An overall comparisonThe novel methodology developed in this paper has enabled us to disentangle the dual effects of technological change on the global dynamics of the labor share. This has allowed us to identify both the U-shaped trend in labor output elasticity and the increasing levels of the elasticity of substitution. Our findings suggest that the technological changes associated with the early phases of knowledge economy, such as automation and digitalization, have generally reduced both the labor-augmenting direction and its complementarity with capital in developing countries. However, this trend appears to be reversing in developed countries, where human capital is more abundant, with the advent of more advanced digital technologies. Since the mid-2010s, innovations such as the internet of things and collaborative robotics seem to enhance both the labor-augmenting direction and complementarity between labor and capital, potentially reshaping the global trajectory of labor share dynamics.

The rise of remote working and the transition to the Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterized by advances in artificial intelligence and digital technologies, will also reshape the relationship between capital and labor. These transformations will allow firms to expand their capital investments across a broader range of activities, potentially reducing the overall elasticity of substitution by strengthening complementarities between skilled labor and digital tools. However, in some contexts, automation and based systems on artificial intelligence may improve substitutability by simplifying routine tasks and reducing reliance on human labor. Furthermore, the growing availability of data and the rise of data-driven decision making could improve the efficiency of resource allocation, potentially altering the dynamics of substitutability between production factors depending on how firms exploit these technologies.

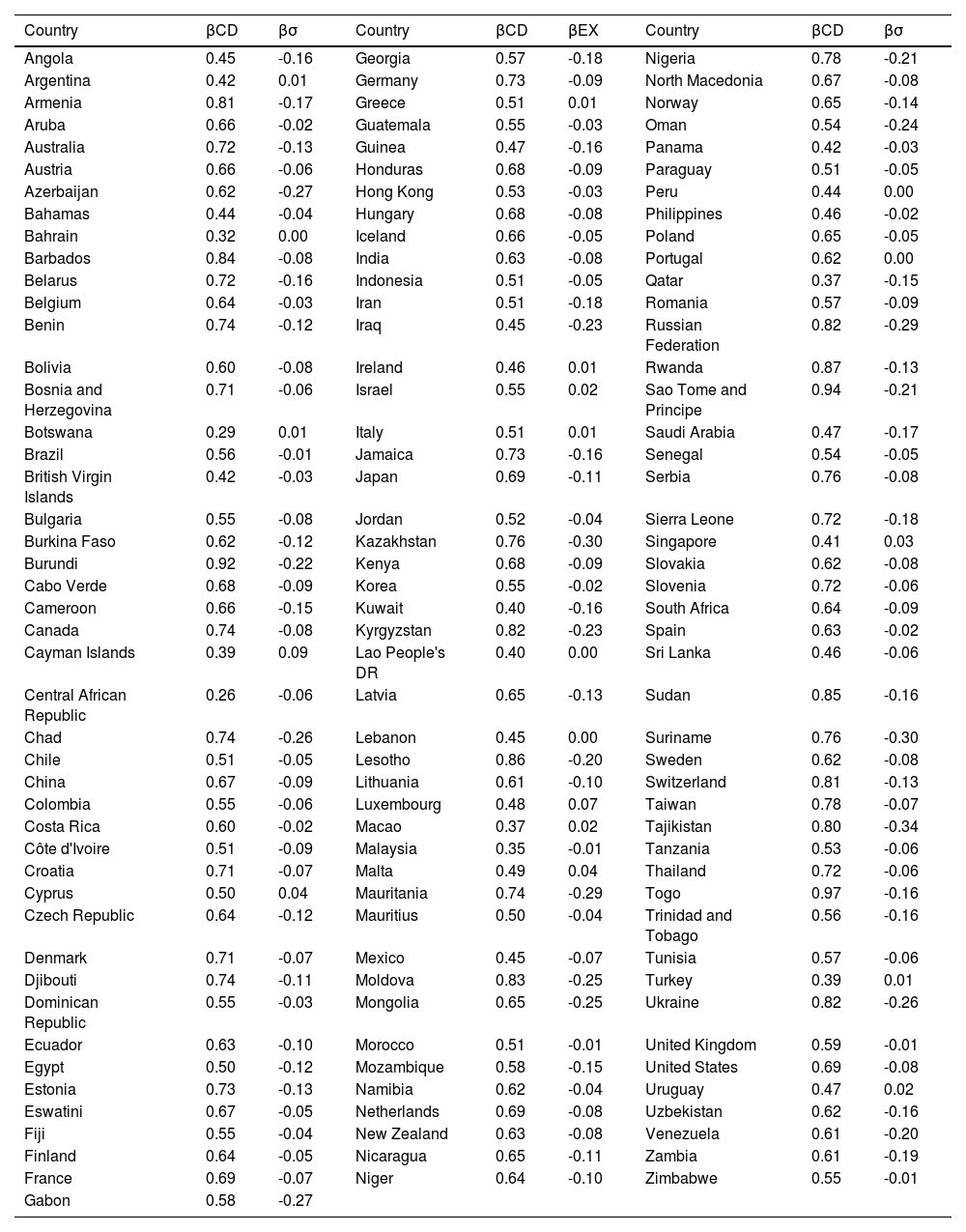

Table 2 delves into the spatial heterogeneity of these two effects. In OECD countries, technology tends to be labor-intensive, with βCD>0.5, and exhibits complementarity among productive factors, with βσ<0. In non-OECD countries, the directionality of technological change varies widely among countries, even though the technological substitutability of productive factors is generally higher than in OECD countries. It is intriguing to note that, in the few countries where βσ>0, there is both a substitutability between capital and labor and a low direction of technological change towards labor (i.e., βCD is low).

The average labor share components by country.

Source: PWT 10.01 and our own elaboration.

This evidence, in which the two effects counterbalance each other, appears to be pervasive across all analyzed countries. This observation has a clear theoretical explanation. The directionality of induced technological change theory assumes a Cobb-Douglas elasticity of substitution (i.e., σ=1). In real-world scenarios, when the cost of labor exceeds the cost of capital,1 firms tend to substitute labor with capital. However, when productive factors are complementary, it becomes impossible to replace the more expensive factor (labor) with the cheaper one (capital). In this case, higher wages increase the labor share without reducing the amount of labor employed. Conversely, when the elasticity of substitution is greater than 1, it becomes easier to substitute labor with capital, causing the labor share to decrease rapidly.

The key methodological insight here is that, despite being averages, both components of technological change display significant variability. This suggests that similar labor share values can arise from markedly different circumstances. Essentially, each country's observed average labor share results from the cumulative impact of these two average components. For instance, while the United States and Spain may share a similar labor share in GDP, the underlying values of the two components in absolute terms are considerably larger in the United States. An even more pronounced distinction is evident in the comparison between Italy and Russia. Although their labor shares appear similar, the structure of the two countries is very different. Indeed, Italy has a low labor output elasticity (0.51), augmented by a small and positive extra labor share (0.01). Conversely, Russia has a high labor output elasticity (0.82), yet the extra labor share is large and negative. In other words, seemingly comparable observed labor share values stem from considerable differences in the complementarity and direction of technological change.

Notably, some of the lowest levels of βσ are observed in several former Soviet Union countries (e.g., Russia -0.29, Azerbaijan -0.27, Georgia -0.18, Kazakhstan -0.30, Kyrgyzstan -0.23, Ukraine -0.26, Tajikistan -0.34). This finding aligns with the hypothesis proposed by Nakamura (2015) and Knoblach & Stöckl (2020), which suggests that planned economies tend to exhibit a lower capacity to substitute production factors. Nakamura (2015) argues that in such contexts, distorted prices and rigid economic policies restricted firms' incentives and authority to efficiently substitute capital for labor. Meanwhile, Knoblach and Stöckl (2020) highlight the role of institutional frameworks in shaping the effective elasticity of substitution. Our empirical findings suggest that the legacy of centralized economic systems may have left a lasting imprint on the labor market dynamics of these economies, opening up intriguing avenues for future research.

Fig. 7 complements Table 2 by presenting both CD (in blue) and CES (in green) average labor shares for each country based on PWT data. Generally, the empirical values are lower than the theoretical ones, and this disparity is attributed to the extra labor share component: the elasticity of substitution is below 1. Moreover, it confirms the conclusion of Chen et al. (2022) that the directional effect is the main positive component of the increase in the labor share. Once again, this graphical representation underscores the profound variations in the analyzed phenomena and highlights the relevance of the dual and yet intertwined effects of technological change over labor share: the elasticity of substitution and output elasticity.

Both the standard CD and CES approaches are then inappropriate for analyzing the dynamics of the labor share. The labor share keeps changing with high levels of variance across countries and time because of the underlying continual introduction of technological and organizational innovations that change both the labor output elasticity and the elasticity of substitution. Accounting procedures based upon either the constant unitary value of the elasticity of substitution, as in the CD, or the invariant levels of the factor output elasticity, as in the CES, are unreliable and likely to yield inaccurate information.

The novel methodology implemented by this paper at the national level can also be applied successfully at the industrial and regional levels, contributing to the structuralist approach to the economics of development with in-depth analyses of the effects of all the aspects of technological change ‒ in terms of rate, direction, and elasticity of substitution ‒ on the changing structure of economic systems.

An interpretative frameworkThe new evidence of the cross-sectional and intertemporal dynamics of the distribution of the output elasticity of labor and of the elasticity of substitution calls for an interpretative framework that integrates and reconsiders contributions from established theories. Merging different approaches into a single coherent interpretative framework provides a robust basis for understanding the novel patterns identified in our approach.

This section explores the emerging divide between two distinct growth regimes: the persistence of a traditional capital- and manufacturing-intensity in industrializing countries and the transition of advanced economies towards a knowledge-based paradigm. The theories of induced technological change and Schumpeterian innovation offer key insights for this interpretation. We analyze their contributions in turn.

The induced technological change hypothesis offers fundamental insight to unravel the observed puzzles, but only when considering the dynamics of factor markets in depth. Indeed, technological change is directed towards the more intensive use of the cheaper factor by increasing its output elasticity. However, several factors play a pivotal role in the continual shifts of supply and demand in factor markets, significantly impacting their relative abundance and costs with direct consequences on the levels of technological congruence (Antonelli & Feder, 2024).

A large literature impinges upon the skill-biased approach. Here the surge in the supply of skilled labor triggered by the college boom in advanced countries plays a central role. The increase in the relative abundance of skilled labor and human capital exerted a strong incentive to direct technological change towards its intensive use. The demand for skilled labor increased substantially with positive effects on the average and the variance of wage levels. The skill intensive direction of technological change of wages triggered a radical change in the composition of the work force: the decline of the share of blue collars and the sharp increase of the share of white collars. The change in the mix of the composition of the work force boosted absolute wage levels–as well as the levels of wage inequalities–and ultimately engendered the increase of the labor share (Acemoglu, 1998, 2002a, and 2002b).

The routine biased technological change approach complements the skill biased. The analysis here concentrates attention on the changing mix of tasks in production activities. Technological change is directed to reduce the role of routine activities and enhance the productivity of creative ones. The share of creative labor increases while the share of routinized labor shrinks. Wage dynamics mirrors the dynamics of the composition of the work force with direct and powerful effects on the increase of the labor share (Acemoglu & Autor, 2011).

The identification of the so-called headquarter effect provides further support to the analysis. Firms based in advanced countries reduce their manufacturing activity and rely more and more on international outsourcing from third parties based in industrializing countries and the manufacturing capacity of subsidiaries established abroad in the same industrializing countries by means of foreign direct investment. Firms retain at home the highbrow and skill-intensive activities such as R&D, finance, marketing, advertising with a strong change in the composition of their work force. Labor with low levels of human capital decline and labor with high levels of human capital increases. Wage levels parallel the change in the mix of labor force and directly affect the aggregate labor share (Foss, 1997).

Globalization has forced radical changes in the direction of technological change and the structure of economic systems. It has reshaped the international division of labor by altering the relative specialization of countries. Global corporations have retained their skilled-labor-intensive activities at their headquarters in developed countries of origin, while relocating capital-intensive manufacturing plants to developing countries. Developed economies have specialized in the production and use of knowledge ‒ an activity highly labor intensive ‒ and are adopting efficiency wage and remote work strategies in order to enhance inclusion and incentives to foster labor force participation in the generation of new knowledge. Additionally, the liberalization of financial markets has spurred capital outflows to developing countries, transforming the dynamics of capital abundance. Indeed, the gap in the access conditions to capital markets and in the capital rental cost, between developing and developed countries, has narrowed substantially, increasing the relative incentives to introduce capital-intensive technologies in developing countries (Baldwin, 2016).

The evolving direction of technological change mirrors transformations in the economic structure of developed economies. Manufacturing industries, traditionally characterized by high capital intensity, have sharply declined in output and employment, shifting the bulk of economic activity to service industries with generally lower capital intensity. Industrializing economies, on the other hand, specialize in capital intensive manufacturing activities that rely on a work force with low levels of skills, human capital and consequently low wages.

These shifts in factor intensity stem from standard substitution processes, further increased by the introduction of directed technological changes aimed at enhancing the efficient use of the relatively more abundant factor. According to the theory of induced technological change, skilled labor–embodying knowledge–emerged as the cheaper input in developed economies, steering technological change towards labor-intensive processes. Contrary to the expected capital-intensive direction of technological change in developed countries, a new labor-intensive trend has gained prominence, particularly in the last few years. In developed economies, the accumulation of large stocks of quasi-public knowledge has supported the intensive utilization of skilled labor and human capital. As knowledge becomes the cheaper input, a fundamental shift occurs in the direction of technological change, favoring skill intensity over capital intensity (Pialli, 2025).

The results of the analysis based on the induced technological change approach align closely with the outcome of the Schumpeterian approach. This framework posits that, in developed countries, competition is driven by product and process innovations. Firms in these economies increasingly depend on intensive, knowledge-based labor, internally developed through inclusive learning processes that involve motivated, highly skilled workers. The bottom-up processes of learning play a central role and support both the increase of wage levels–of skilled and creative workers–and of the complementarity between capital and labor. This knowledge, recombined with the quasi-public knowledge available locally, enables firms to raise factor productivity and outcompete rivals, particularly when and if knowledge costs are below equilibrium levels. When competition hinges on the introduction of productivity-enhancing innovations, labor shares are large (Antonelli & Feder, 2021a, 2021b, 2022, and 2024).

Price competition dominates commodity markets, where firms in developing countries aim to minimize costs by directing technological change towards capital, the relatively cheaper input available locally. This trend is fueled by growth savings, globalization of financial markets, substantial foreign direct investment, and access to financial markets in developed countries. As a result, developing countries have become the target of substantial foreign direct investment specialized in capital-intensive technologies, which have driven their growing specialization in the supply of capital-intensive activities within global value chains (Koopman & Wacker, 2023). Shifts in factor intensity in these areas reflect substitution processes enriched by technological innovations that augment the utilization of the more abundant factor.

The Schumpeterian approach aligns closely with, and is indeed reinforced by, the hypothesis of localized technological change, which suggests that the direction of technological change is directed toward increasing the output elasticity of inputs that are becoming more expensive. The secular rise in wages, for example, drives the introduction of labor-intensive innovations. This dynamic is shaped by the localized nature of learning processes, which can realistically occur only within the techniques already in use. Such localized learning constrains firms to adhere to their original isoclines and exert a strong negative effect on the levels of the elasticity of substitution of labor to capital. Innovation becomes possible only when firms can leverage the competencies and technological knowledge acquired through these localized learning processes (Atkinson & Stiglitz, 1969; Antonelli, 2019). The dynamics of localized technological change are particularly relevant in knowledge-driven economies, such as those of the OECD countries (Abramovitz & David, 1999).

The Schumpeterian perspective also provides insight into the increasing divergence in the direction of technological change between developing and developed countries. Indeed, in developed economies, the transition toward a knowledge economy, where labor is the pivotal element, is well underway. Practices like efficiency wages, labor hoarding, remote working, and an array of inclusive mechanisms are becoming common, in a broad range of knowledge intensive activities, exerting a positive effect on the output elasticity of labor and a negative effect on the levels of the elasticity of substitution between labor and capital (Stiglitz, 1976; Arif, 2021; Acemoglu, 2015).

The potent effects of globalization on factor markets and its dual direct and indirect effects in both developed and developing countries lie at the core of the U-shaped trajectory of the direction of technological change and its implications for the labor share and the elasticity of substitution between labor and capital.

In sum, the hints provided by the induced technological change approach and the Schumpeterian literature reviewed so far help provide an integrated interpretative framework that suggests that a major divide has been taking place between advanced and industrializing economies. Industrializing countries remain embedded in a Fordist growth regime characterized by capital-intensive manufacturing industries. Advanced countries have become already full-fledged knowledge economies where knowledge is at the same time the key input and one of the most important outputs. Advanced countries specialize in the production and exploitation of knowledge because knowledge has become the cheaper input in local factor markets. Because of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge, the new vintages of R&D expenditures add to the existing ones and cumulate, increasing the size of the stock of quasi-public knowledge available in advanced economies. Firms based in advanced countries have easier access to the stock of quasi-public knowledge and enjoy relevant pecuniary knowledge externalities. The decline of the cost of knowledge has triggered the dynamics of technological congruence inducing the knowledge-intensive direction of technological change and the related structural change that favors the growth of knowledge intensive activities. The sharp difference in knowledge costs between advanced and industrializing countries acts as a powerful additional incentive to the knowledge intensive direction of technological change. The cost difference in fact becomes a powerful mechanism of de-facto appropriability. Competitors based in industrializing countries can imitate the new knowledge intensive technologies but cannot access knowledge at the same (low) costs. The appropriability of innovation rents is larger and can last far more when competitors cannot access inputs at the same costs. The new knowledge economy seems characterized by the central role of human capital and skilled labor that becomes the central input. In the new knowledge economy, the core of the economic activity is the skilled-labor-intensive generation of technological knowledge with enhanced levels of complementarity between labor and capital with the consequent large levels of the labor share and the lower levels of the elasticity of substitution (Antonelli, 2019; Antonelli et al., 2023).

The identification of the U-shaped trend in the direction of technological change across the world economies calls attention to the problems facing middle-income countries that have been able to foster their growth by implementing a capital-intensive direction of technological change. The increased levels of revenue expose them to the need for a drastic change in their growth regime from a low to a high wages, a capital- to a skilled labor-intensive direction of technological change, and a reduction of their elasticity of substitution. The radical shift in the growth regime exacerbates the well-known middle-income trap (Lee, 2013).

ConclusionsThe paper makes three main contributions to the induced technological change literature: (i) it elaborates and applies a novel methodology that allows for the disentanglement and identification of the dual, yet distinct, effects of the direction and substitutability of technological change on labor share; (ii) it examines worldwide evidence regarding the dynamics of labor share and provides a preliminary identification of its components; iii) it provides evidence about the divide between the trends shaping advanced and industrializing countries, particularly regarding the direction of technological change, its impact on the labor share, and the complementarity between capital and labor.

Leveraging the properties of labor in both CD and CES production functions, we have introduced a straightforward measure capable of disaggregating the direction of technological change and its complementarity in utilizing production factors. Our analysis reveals substantial spatial and temporal heterogeneity in both the labor share and its technological components, with distinct trends observable in each country. Given that both aspects of technological change under examination impact labor share, these measures serve a dual purpose: to estimate the characteristics of technologies employed and to comprehend their effects on the labor market.

By integrating these observations, we provide new evidence of a clear divide between advanced and industrializing countries. In industrializing countries, the labor share continues to decline alongside a weakening complementarity between capital and labor. Growth in these economies still relies on a Fordist model, characterized by capital-intensive manufacturing, low wages, and high substitutability between labor and capital.

In contrast, in advanced countries, the labor share decline has plateaued, and, recently, it has begun a gradual but steady increase. In these countries, recent technological change has been more labor-augmenting and exhibits larger complementarity between capital and labor. Advanced countries are now transitioning towards a fully developed knowledge economy, where knowledge serves as both the prime input and output. This shift is reflected in rising levels of human capital, skills, and wages, which in turn contribute to increasing labor shares and stronger complementarity between capital and labor.

This evidence becomes even more compelling when viewed through a historical lens. The database, available from 1991, coincides with the early phase of rapid globalization and technological advancement that have shaped the international economy since the late 20th century. From the outset of globalization, the knowledge economy has already begun to significantly impact labor markets in advanced countries, influencing income redistribution.

However, further empirical analyses will be needed to confirm and strengthen this hypothesis. While a simple analysis of the overall labor share fails to capture this shift in composition, our detailed examination, which differentiates the two effects of technological change on the labor share as proposed in this paper, has successfully identified the actual trends at work.

The cross-sectional analysis of the direction of technological change in the global economy, as identified by the levels of output elasticity of labor, reveals that the labor-augmenting direction is more pronounced in developed knowledge-driven countries. In these countries, where wages and revenue levels are higher, the substantial stock of knowledge requires intensive use of skilled labor to maximize its positive effects on productivity and competitiveness. This cross-sectional evidence is further supported by recent trends showing an actual increase in the output elasticity of labor and a decline in the elasticity of substitution between labor and capital.

Our analysis reveals a significant divergence in the direction of technological change between OECD and non-OECD countries. In many advanced economies, innovation is increasingly driven by labor-augmenting processes that rely on skilled labor and human capital, while numerous developing countries continue to pursue rapid capital deepening. This divergence suggests that the rapid increase in capital intensity in these weaker economies is likely to clash with frontier technological advancements characterized by high labor intensity, thereby quickly rendering their capital-intensive technology obsolete. Such misalignment not only exacerbates wealth and income inequality–particularly given that even high levels of elasticity of substitution can adversely affect labor markets–but it may also contribute to the persistence of the middle-income trap, limiting the long-term viability of their growth models.

Considering these findings, it is imperative that governments in industrializing economies reorient their policies toward strengthening human capital. Targeted vocational training programs, improvements in higher education curricula with an emphasis on digital skills, and fiscal incentives for research and development in labor-intensive sectors are essential measures. Additionally, establishing public-private partnerships to facilitate technology transfer and innovation can help shift technological trajectories toward more sustainable, labor-intensive solutions. Reinforcing the reduction in elasticity of substitution–by, for instance, supporting organizational practices based on efficiency wages–can further mitigate adverse effects on income distribution and labor markets. Based on our results, we recommend that governments promote policies that incentivize investment in education and continuous training to prepare workers for the new skills required by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. At the same time, companies should adopt strategies that value human capital by promoting technical knowledge and making machines more user-friendly and user-centered.

The methodology proposed in our analysis is both simple and flexible, making it adaptable to various contexts and levels of granularity–from local to macroeconomic scales. Firms must acknowledge that the emerging paradigm is characterized by a shift toward labor-intensive rather than capital-augmenting technological change, highlighting the critical need for robust investments in worker training and human capital. Future research should focus on post-2019 trends in the labor share, including the impact of remote working and the reorganization of global supply chains in response to the pandemic, as these elements are essential for tracking the key components of global innovation trends. In advanced economies, policymakers should also consider implementing measures that support a resilient labor market by incentivizing flexible work arrangements, adopting efficiency wage policies, and rebalancing capital allocation to ensure that technological investments are complemented by efforts to nurture and retain human capital. These strategies are vital for fostering innovation, maintaining workforce productivity, and building sustainable competitive advantages in a rapidly evolving global market.

By aligning these targeted policy measures and corporate strategies with the dynamic patterns of technological change, both governments and firms can better navigate the ongoing economic transformation, thereby promoting more inclusive growth and reducing the potential adverse effects on income distribution. Our article represents a first step in this direction, laying the groundwork for further research and the development of effective policy and corporate strategies.

CRediT authorship contribution statementChristophe Feder: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Cristiano Antonelli: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Conceptualization.

In this appendix, we demonstrate that the residual component of the labor share, βσ, is closely related to the elasticity of substitution of a CES production function. Therefore, variations in the elasticity of substitution, along with the direction of technological change, are the primary drivers of labor share dynamics. While factors such as market disequilibrium or returns to scale may influence labor share fluctuations, their impact appears limited. This suggests that economic systems are in constant flux, underscoring the need for production functions that can adapt to evolving technological conditions.

We begin by replicating the procedure used to estimate βCD, in order to estimate β as well. In equilibrium, the optimal allocation of factors under a CES production function, as described in (1), is:

Note that, when σ=1, we revert to (4), and it is also feasible to compute the labor share in the CES production function, β:

Using (5), (6) e (A.2), we can rewrite βσ as:

The first term incorporates the elasticity of substitution, while the second term, which is subtracted, replicates the first term without the elasticity of substitution. Consequently, the remaining difference is a function of σ. To understand how the elasticity of substitution affects the residual component of the labor share, βσ, it is useful to compute the first derivative:

This derivative shows that an increase in the elasticity of substitution raises (reduces) the residual of the labor share when the country is capital-abundant (labor-abundant) (i.e., when K>(<)L). Indeed, the sign of (A.4) depends solely on the value of ln(K/L). Intuitively, in capital-abundant countries, the shift from labor to capital leads to a reduction in the labor share, except when labor and capital are complementary inputs. Vice versa, in labor-abundant countries, the labor share grows as capital is replaced by labor, with the effect being more pronounced when the two inputs act as substitutes.

We can observe this relationship empirically using PWT data. Starting from the equilibrium condition in (A.1), we can quantify σ as follows:

Table A.1 presents the key descriptive statistics for this appendix and demonstrates that all countries are capital-intensive, indicating a positive relationship between βσ and σ. It also shows the scalarization of σ in relation to βσ. The threshold level is 1 for the elasticity of substitution and 0 for the residual of the labor share.

Descriptive statistics: new insights and comparisons.

Source: PWT 10.01 and our own elaboration.

Figs. A.1 and A.2 replicate Figs. 5 and 6 but for the elasticity of substitution. These new figures confirm the findings previously discussed in subsection 3.4. To further verify this, we observe that the correlation between the two variables is positive and very high, at 90.73%.

Although the comparison between the factor costs depends on the unit of measurement used, Zuleta's (2012) methodology allows us to confirm the excellent approximation provided by the PWT.

We gratefully acknowledge the detailed comments and suggestion of two anonymous referees.

This paper is part of the project NODES which has received funding from the MUR – M4C2 1.5 of PNRR funded by the European Union - NextGenerationEU (Grant agreement no. ECS00000036).