Digital technology is increasingly blurring the lines between humans and machines, significantly influencing the distribution of income among workers. The question of how businesses can capitalise on the benefits of digital advancement by optimising internal human capital allocation during the digital innovation process has become a critical concern. This study utilises the Sentence-BERT(SBERT) model to identify digital innovation and examines its effects on the labour share within firms, alongside the underlying mechanisms from the viewpoint of human capital allocation. The research findings are as follows: First, digital innovation has a positive and significant impact on the labour share, a conclusion that remains robust after conducting various sensitivity tests and addressing endogeneity issues. Second, the mechanism analysis reveals that changes in human capital allocation serve as a crucial mediating factor between digital innovation and labour share. Further exploration indicates that skills training, as an element of human capital allocation, demonstrates varying levels of influence across various company sizes and industry characteristics. Third, the positive impact of digital innovation on labour share is more pronounced in regions with supportive business environments, high-tech sectors and firms with superior corporate governance. Lastly, for ordinary employees, digital innovation enhances their labour share. Conversely, for management, while digital innovation reduces their labour share, it increases their equity incentive, suggesting that digital innovation aids in bridging the digital divide within firms and fosters a more equitable distribution of benefits. This study not only enriches the theoretical understanding of the effects of digital innovation on labour income but also encourages the practical application of digital innovation in reducing the wealth gap and achieving shared prosperity.

In the era of rapid technological progress, digital innovation has become a crucial driver of global economic expansion. It has infiltrated numerous sectors and is fundamentally altering traditional production techniques and business strategies. According to the "Global Digital Economy White Paper (2024)" published by the China Information and Communication Technology Institute, the remarkable growth of digital technologies, including large-scale artificial intelligence models, has resulted in a digitalisation rate of 86.8 % across the industries of major nations. China's 14th Five-Year Plan explicitly highlights the need to deepen the integration of digital technologies into economic, social and industrial development, while also promoting innovation in digital applications and business models. Owing to its unique characteristics of connectivity, scalability and intelligence, digital innovation has not only transformed production methods but has also significantly impacted labour market dynamics and employment structures (Usai et al., 2021). Enterprises, as microcosms of economic activity, act as primary agents of digital innovation (Fang & Liu, 2024). Existing literature confirms its substantial economic influence on corporate development (Ballestar et al., 2020; Li et al., 2024), particularly regarding the distribution of labour share (Dou et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2024; Li et al., 2023a). However, the specific mechanisms driving these effects warrant further investigation.

Since the early 1980s, labour share has been in decline in most countries (Li et al., 2023a; Serres et al., 2001; Zhang, 2019). This trend has been particularly pronounced amid ongoing technological advancements and the reconfiguration of the global supply chain, leading to extensive discussions about the dynamic changes in labour share. As a developing nation, China has experienced continuous fluctuations in labour share due to the large-scale migration of labour from agriculture to manufacturing and services within the context of global integration. Data from the China Statistical Yearbook indicates that the proportion of labour remuneration to GDP has been decreasing since it peaked at 56.5 % in 1983, falling to 20.9 % in 2022, while the share of capital remuneration has been rising. Concurrently, China's Gini coefficient has been declining year on year. Although it slightly decreased to 0.471 in 2023, it remains above the warning threshold of 0.4, indicating a persistent wealth gap in China. Given this context, China's labour market is currently facing multiple challenges. On one hand, the ageing population and related demographic issues are gradually eroding the demographic dividend, leading to labour shortages and rising labour costs for Chinese enterprises (Ang et al., 2024). On the other hand, the advent of the computing power era has brought about issues such as automation replacing labour and skill mismatches, raising concerns about the potential threats that digital innovation poses to the employment stability and income prospects of traditional workers (Acemoglu et al., 2014; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018).

In light of these challenges, increasing labour share has become a pressing practical issue that must be addressed to promote sustainable economic growth and achieve common prosperity in China. In recent years, the Chinese government has placed significant emphasis on income distribution, implementing a series of policies aimed at improving workers' incomes. The 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development in the People's Republic of China and the Outline of Long-term Goals for 2035 underscore the policy objectives of raising residents' incomes and narrowing the income gap, while also highlighting the need to enhance labour share. As a metric for assessing the proportion of workers in national income, labour share is vital for maintaining social stability, fostering consumption growth and achieving a more balanced economic development model (Decreuse & Maarek, 2015). For enterprises, labour share serves not only as an important measure of the fairness of interest distribution within organisations but is also directly linked to employee well-being and the long-term growth potential of businesses. Therefore, in the context of the digital revolution, it is of great practical significance to thoroughly investigate the economic relationship between digital innovation and labour share in enterprises, to promote the co-evolution of innovation activities and labour market policies and to ensure the simultaneous advancement of high-quality economic development alongside social equity and justice.

This study aims to integrate digital innovation into the framework of income distribution within enterprises, elucidating the theoretical underpinnings of how advancements in digital innovation affect the labour share of companies. Using data from China's Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share listed companies covering the period from 2012 to 2022, the paper explores the specific impact of digital innovation on enterprise labour share and its operational mechanisms. The findings reveal that, first, digital innovation significantly boosts labour share, a conclusion that remains robust after various sensitivity analyses and treatments for endogeneity. Second, the mechanism analysis indicates that adjustments in human capital allocation play a vital mediating role between digital innovation and labour share. Further research reveals that skills training, as a factor in human capital allocation, exhibits a more significant mediating effect in larger enterprises and industries belonging to labor-intensive industries. Third, the impact of digital innovation on the labour share varies due to regional business environments, the technological nature of industries and corporate governance levels. Fourthly, digital innovation enhances the labour share of ordinary employees, while for management, it decreases their labour share but increases their equity incentive. This suggests that digital innovation helps bridge the digital divide within firms and fosters a more equitable distribution of benefits.

There are two branches of literature most relevant to this paper. The first branch explores the impact of digital transformation on firms' labour resource allocation. This strand of literature demonstrates the economic consequences of digital transformation from various dimensions and channels. Li et al. (2023a) argued that digital transformation increases labour share by relaxing firms' capital constraints. Jiang et al. (2024) also confirmed that digital transformation can increase the labour share, and further research suggested that the pledge of corporate equity weakened the positive effect of digital transformation on the labour share. In contrast, Dou et al. (2023) found that from the perspective of labour structure optimisation, the digital transformation of firms increases the proportion of tertiary-educated, high-skilled labour and R&D researchers, which, in turn, contributes to the upgrading of the labour structure. The second branch of literature examines the impact of innovation activities on labour market conditions. The effects of innovation activities on the labour market are widely recognised as complex, but there is no consensus on the implications of this Schumpeterian "creative destruction" effect (Harrison et al., 2014; Liu & Sun, 2024; Van Reenen, 1997). Specifically, studies have explored the effects of automated technologies (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018; Dinlersoz & Wolf, 2024), robots (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020; Ballestar et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2024), artificial intelligence (Aghion et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2024a; Yang, 2022; Zhang, 2023), IT technology and non-neutral technologies (Zhang, 2019). And different specific areas of innovation activities have different influence directions and degrees on the enterprise labour market.

According to our review of the literature, these two branches have the following research gaps. First, digital transformation and digital innovation do not share the same connotation and focus (Sumbal et al., 2024), and their economic effects are not directly equivalent. Digital transformation aims to improve efficiency, enhance customer experience and create new sources of value by transforming the business model, organisational structure and culture of enterprises. In contrast, digital innovation emphasises the development and application of new technologies to enhance the innovative nature of products and services, as well as improving the core competitiveness and technological advantage of companies. The existing literature on labour resource allocation primarily focuses on the effects of digital transformation, rather than the effects of the level of digital innovation itself, especially concerning firms' labour share. Second, innovation activities encompass a broader scope. As a type of innovation activity, digital innovation embodies the development of new products, the provision of new services and the optimisation of production processes in the digital domain. Few studies have directly addressed the impact of digital innovation on labour share, and different areas of innovation activities may yield opposing labour effects.

Compared to established studies, this paper contributes in three major ways. Methodologically, it evaluates the various patent identification methods available in current literature and utilises the advanced Sentence-BERT(SBERT) model to quantify digital patents, surpassing previous research that relied solely on International Patent Classification (IPC) classification codes or basic textual analyses to quantify digital patents. This choice offers a more precise tool for gauging the true impact of digital innovation. Additionally, in contrast to previous fields of innovation activities, this paper examines in depth the impact of digital technological innovation on the labour share of enterprises and its internal mechanisms from the perspective of optimising human capital allocation. Finally, an analysis of the impact of digital innovation on labour share under differing regional, industry and enterprise characteristics is also provided. The government can use this to address the challenge of declining labour share in specific digital environments with empirical support and policy implications, while laying a theoretical and practical foundation for achieving society's common prosperity goal.

Theoretical analysis and hypothesis developmentDigital innovation and enterprise labour shareLabour share is essential for firms to maintain employee motivation, ensure social stability and foster sustainable development. The key to enhancing labour share at the enterprise level lies in analysing its dual impact on improving the job market and increasing wage levels.

From the perspective of enhancing the job market, digital innovation directly contributes to the optimisation and upgrading of the employment structure by creating new job opportunities and career paths (Ballestar et al., 2020; Harrison et al., 2014). On one hand, technological advancements have led to the emergence of numerous new industries and roles (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019; Dou et al., 2023; Van Reenen, 1997), such as big data analysts and artificial intelligence specialists (Zhang, 2023). The rise of high-skilled positions absorbs a significant number of workers while also improving overall employment quality (Stehrer, 2024). On the other hand, the automation and intelligence transformation of traditional industries may lead to the downsizing of some low-skilled jobs in the short term (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020). However, in the long run, the deep integration of digital innovation can enhance production efficiency, establish a foundation for business expansion and diversification and indirectly result in the creation of more jobs (Uddin, 2024).

From the viewpoint of increasing wages, digital innovation has significantly boosted labour productivity, providing a solid basis for wage growth. First, with the application of technology, employees are required to operate more complex systems and process larger volumes of information, which enhances labour productivity and leads to increased output (Zhao et al., 2024). According to rent-sharing theory, due to the presence of frictions in the labour market, when firms earn excess profits, they are likely to share these gains with their employees to mitigate production costs associated with employee turnover (Liu & Sun, 2024). Second, in line with skill-based technological advancement, highly educated and skilled workers have gained increased bargaining power due to their irreplaceable value, allowing them to command higher wage premiums based on their marginal productivity (Chen et al., 2024a). Third, enterprises driven by digital technology are encouraged to implement more transparent and personalised digital performance management and compensation systems (Li et al., 2024), which help ensure that workers' contributions are accurately assessed and rewarded, further promoting reasonable wage increases and optimising income distribution (Jiang et al., 2024). Based on this analysis, digital innovation not only positively influences the labour market by broadening employment opportunities and optimising occupational structures but also indirectly contributes to rising wage levels by enhancing production efficiency, improving worker quality and refining compensation management systems. Together, these factors significantly increase the labour share within enterprises. Accordingly, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 1: Digital innovation increases the labour share of enterprises.

Digital innovation, human capital allocation and enterprise labour shareAccording to the Slow Growth Model, technological innovations will inevitably steer the economic system towards a more efficient and sustainable growth trajectory (Li et al., 2022). The advancement of digital innovation serves not only as a new engine for economic growth but also as a key source of competitive advantage for enterprises. It can drive improvements in labour share by optimising human capital allocation, with its internal mechanisms summarised as shown in Fig. 1.

Digital innovation optimizes human capital allocationExisting literature widely acknowledges the significant impact of digital innovation on the enhancement of human capital allocation (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019; Dou et al., 2023). Digital innovation profoundly influences the optimisation of human capital allocation through a series of complex mechanisms. First, digital innovation raises the technical skill requirements in the labour market. As digital technologies become increasingly integrated into various aspects of business operations, the demand for employees skilled in these technologies is rising (Buck et al., 2023). This technology-driven shift compels companies to reassess and adjust their internal skill composition, thereby creating a more technical and specialised workforce. Second, digital innovation provides extensive opportunities for skill enhancement and retraining. The implementation of digital technologies necessitates higher levels of technical competence from employees (Xiao et al., 2024), aligning with human capital theory, which posits that education and training are vital for improving individual skills and productivity (Bartel & Lichtenberg, 1985; Strazzullo, 2024). Thanks to the proliferation of online learning platforms and virtual training programmes, employees can more easily acquire new skills and reinforce existing ones (Chen et al., 2024c; Dinlersoz & Wolf, 2024). This not only prepares them for more complex roles but also ensures that companies remain competitive in the ever-evolving digital landscape, thereby mitigating the risk of skill gaps (Buck et al., 2023). Third, digital innovation cultivates a culture of continuous learning and innovation within organisations. By fostering an environment that encourages employees to explore new ideas and engage in technological experimentation, companies can sustain their industry leadership and competitive advantage (Sumbal et al., 2024). This culture not only attracts top talent seeking innovation and personal development but also enhances talent retention, fundamentally optimising human capital allocation. In summary, by raising technical skill standards, providing opportunities for skill enhancement and nurturing a culture of ongoing learning and innovation, digital innovation effectively optimises human capital allocation, establishing a robust human resource foundation for a company's long-term growth.

Human capital allocation promotes enterprises' labour shareThe optimisation of human capital allocation plays a vital role in fostering a more equitable labour distribution. First, as human capital allocation improves, the skill premium in the labour market increases. Workers' bargaining power strengthens with higher skill levels, leading to a rise in high-paying, high-skill jobs, while low-skill positions, such as simple, repetitive, programmable and codable tasks, are gradually being automated (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019; Graetz & Michaels, 2018). These shifts benefit workers by positioning them more favourably in the labour distribution (Bental & Demougin, 2010). Additionally, optimised human capital allocation encourages companies to place greater emphasis on skills and innovation, offering better compensation to employees with scarce skills. This skill-based pay structure contributes to a tilt in income distribution towards labour, in line with the principle of marginal productivity in economics. The increased number of high-skill workers directly results in a larger share of income distribution for labour due to their specialised knowledge and significant contributions to productivity. Finally, refined human capital allocation creates more jobs that require cognitive and creative skills, which are less susceptible to automation, offering higher wages and better job security. This elevates the status of labour in income distribution and creates conditions for labour to participate in and benefit from the digital innovation process. Moreover, the strategic realignment of the workforce, including a higher proportion of professionals with specialised knowledge and advanced education, enhances the dynamism and adaptability of the labour market, enabling it to meet the complex challenges of the modern economy and ensuring that labour remains at the forefront of technological progress and economic growth, thereby further solidifying labour's share. In summary, the optimisation of human capital allocation driven by digital innovation not only enhances the skill level of the workforce and strengthens their bargaining power in income distribution but also mitigates the risk of labour being replaced by automation by creating more high-skill, high-wage job positions. Accordingly, it is proposed that:

Hypothesis 2: Digital innovation promotes the increase of labour share by optimizing human capital allocation.

Research designVariable selectionDependent variableThe dependent variable is labour share (LS). Currently, the cost approach or income approach is frequently utilised in academia to measure labour income share. The cost method focuses on the structure of production costs and estimates the contribution of labour value by calculating the direct and indirect costs incurred by the enterprise to produce goods or deliver services. In contrast, the income method begins from the output side and directly divides the share of labour compensation, such as salaries and bonuses paid to employees, from the firm's total revenue to evaluate the economic value of labour. In this study, the factor cost approach is chosen to measure labour income share using the ratio of total cash compensation paid to employees relative to the gross business revenue of the firm. To ensure the consistency and reliability of the measurement results, this paper will also reassess the labour share of enterprises in subsequent robustness tests, including both the cost and income methods.

Independent variableBefore quantifying the independent variable (Dig), it is essential to clarify the concept of digital innovation. Digital innovation stems from the rapid advancement of information technology and the rise of the digital economy, and it is generally regarded as the process of innovating new products, services or business models through the application of digital technologies. Drawing on the research by Fichman et al. (2014), this process can be broadly divided into four stages: discovery, development, dissemination and impact. Digital innovation encompasses various forms, including process innovation, product innovation and business model innovation. In manufacturing, it typically involves integrating advanced digital technologies into traditional non-digital products and services, endowing them with new digital attributes (Autio & Thomas, 2020). In the IT sector, digital innovation is more focused on the creation of new products and processes based on software code and data(Guellec & Paunov 2017). Despite sector-specific interpretations, the core element of digital innovation remains the creation of new value through digital technology (Yoo et al., 2010). At the corporate level, the outcomes of digital innovation are often manifested in the form of patents, which serve as a proxy for a firm's innovative capacity. Consistent with the consensus in the literature (Arts et al., 2021; Yang, 2022), we use patent counts as an indicator to measure the output of technological innovation and assess the level of digital innovation in enterprises.

The academic community has yet to establish a uniform standard for research methods concerning patent tasks (see Appendix Table 1 for examples). The identification of digital technology patents primarily involves the IPC method (Fang & Liu, 2024) and text analysis methods (Acikalin et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2024). The IPC method, while normative, is based on the "Statistical Classification of the Digital Economy and Its Core Industries (2021)" and the Reference Relationship Table provided by the National Intellectual Property Administration for annual digital technology patent counts at the enterprise level. However, it may suffer from inaccuracies or incomplete classification due to potential misclassification or undercoverage of digital technology patents in emerging or interdisciplinary fields, as detailed in Appendix Table 2. After reviewing past studies and comparing different methods, this paper opts for text analysis, utilising patent abstracts as a more objective and information-rich resource. Following the approach of Acikalin et al. (2022), we employ a machine learning-based text analysis method to identify the potential impact of each company's patent portfolio.

Definitions of the main variables.

In selecting the model, we considered the importance of sentence-level semantic similarity computation and the need for efficient sentence comparison in patent classification tasks. We chose the SBERT model, an enhanced version of BERT, to determine the digital technology attributes of patents (the identification steps of the SBERT model are illustrated in Fig. 2). Since its introduction by Google in 2018, the BERT model, a deep learning model based on the Transformer architecture, has significantly improved text comprehension with its bidirectional context encoding, achieving high precision with a small corpus and demonstrating remarkable success in various natural language processing tasks (Maehara et al., 2022). Unlike the traditional BERT model, which relies solely on the first token (the [CLS] token) to represent the semantic information of the entire sentence, SBERT extracts a more comprehensive and rich sentence-level representation through a specific pooling strategy from all token embeddings (Wang & Kuo, 2020). This enhancement allows SBERT to maintain BERT's powerful context understanding while providing more accurate and efficient sentence-level representations, thus offering strong support for semantic comparison of patent abstracts. Moreover, to better handle Chinese text in the patent domain, we fine-tuned the SBERT model with Chinese-BERT-wwm, a Chinese pre-trained model based on the Whole Word Masking technique, optimised for Chinese corpora and pre-trained on the latest Wikipedia Chinese dump. This model exhibits strong capabilities in Chinese natural language processing, effectively managing complex vocabulary and phrases in Chinese patent texts.

When preparing for the identification study of digital technology patents, it is essential to ensure data quality and applicability through preliminary processing. This involves two primary tasks. First, data acquisition and integration: (1) We gather abstracts and related metadata for over 30 million invention and utility model patents from 1985 to 2022; (2) Based on the patent applicant field, we assign patents to their corresponding companies; (3) We pre-process the text information by removing special characters and stop words, minimising data noise and converting all text to UTF-8 encoding while standardising case to eliminate formatting discrepancies; (4) Using stratified sampling with 4-digit IPC codes, we draw a random sample of 60,000 patents. The dataset is then randomly divided into training, development and test sets in a conventional 8:1:1 ratio.

Second, we must establish clear definitions and boundaries for digital technology patents to provide a consistent classification standard for the subsequent SBERT model. Digital technology patents is as patents obtained through innovations based on the internet, big data, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, blockchain and other digital technologies. These technologies are directly applied to information collection, processing, transmission, storage and analysis, or play a key role in digital products, services and solutions, driving digital economic development and the transformation of traditional industries. Drawing from existing literature, expert think tanks and documents such as the "Global Digital Economy White Paper", "China Digital Economy Development White Paper", "Global Digital Economy Competitiveness Development Report" and policy files like the "Statistical Classification of Core Industries of the Digital Economy (2021)", the "14th Five-Year Plan for Digital Economy Development" and the "Master Plan for Digital China Construction", we define digital technology patents as technological innovations centred on digital technologies, achieving efficient information management, cultivating new business models, enhancing the intelligence of products and services and accelerating the digital transformation of the economy and society.

Subsequently, we employed the SBERT model to construct a digital technology patent identification system, following these steps. The first step was to prepare the pre-trained model. Based on previous discussions, we selected the Chinese-BERT-wwm model released and maintained by the joint laboratory of Harbin Institute of Technology and iFLYTEK. The second step involved fine-tuning and training the model. We initially fine-tuned the model to adapt it to the specific task of identifying digital technology patents. Given that the pre-trained model trained on the Wikipedia corpus closely aligns with patent-related information in terms of vocabulary and sentence structure, and has effectively learned Chinese language patterns, we decided to use this pre-trained model for training without additional fine-tuning steps. We then initiated the model training, employing the ChatGPT large language model for initial assessments and manual identification for secondary evaluations to classify the training data and ensure the accuracy of the training set classification. Specifically, to maintain consistent classification rules, we first inputted the definition and connotation of digital technology patents into the ChatGPT model to clarify its understanding. We then used this model for preliminary assessments, with the prompt: "Based on your knowledge, please determine whether the following patent abstract belongs to a digital technology patent. Below are the details of the patent abstract: patent name + patent abstract + claims". Next, we recruited 24 volunteers trained in classification rules and divided them into two groups to independently identify the training set and conduct cross-validation. Patents with differing classification opinions were further discussed collectively to determine their inclusion in digital technology patents. After manually identifying the training set, we began training the SBERT model to learn the classification rules. To enhance model stability and generalisation, we repeated the training 10 times by adjusting seed values.

Table 1 presents the parameter configuration used for training the SBERT model. To prevent overfitting and ensure adequate training time, we set 4 training epochs (Num_epochs). Training logs were recorded every 100 batches (Log_batch) to monitor the process. The batch size (Batch_size) was set to 256, balancing computational efficiency and model performance. Considering typical patent text length and computational efficiency, the maximum sequence length (Max_seq_len) was limited to 64. The model required performance improvement within 1000 epochs (Require_improvement); otherwise, training stopped early. Warmup steps (Warmup_steps) were set to 0, with no warmup phase. Weight decay (Weight_decay) was 0.01 to prevent overfitting. The maximum gradient norm (Max_grad_norm) was 1.0 to avoid gradient explosion. A learning rate (Learning_rate) of 1.5e-5 aided stable model convergence. Training results showed accuracy exceeding 99 % on the training set, with validation and test sets fluctuating between 95 % and 96 %. We then used the best - performing SBERT model from 10 retrained models for subsequent classification tasks. This model had a 4.47 % chance of a "Type I error" and a 3.66 % chance of a "Type II error".

The third step involves applying the trained model to unlabeled patent text abstracts to classify them as digital technology patents. To substantiate the validity of the SBERT model's identification, we independently tallied the number of digital patents using the IPC classification approach proposed by Fang and Liu (2024) and compared it with the SBERT model's outputs. The analysis in Fig. 3 reveals a consistent trend between the number of digital patents identified by the SBERT model and those observed using the IPC classification. Finally, we utilized the count of digital patent applications as a metric for a firm's digital innovation level and applied an inverse hyperbolic sine transformation to the data to mitigate the issue of exaggerated variance due to an abundance of zero and minimal values.

Mediating variableIn this study, the mediating variable is human capital allocation. First, with the rapid development of the digital age, educational background has become a significant indicator for assessing an individual's capacity to absorb knowledge and innovate. Individuals with higher education generally excel at adapting to and learning new technologies (Xiao et al., 2022). Second, the work environment, as a component of human capital allocation, stimulates employees' enthusiasm for their work (Liu et al., 2011), impacting their efficiency and innovation capabilities. Third, during the survival phase of enterprises, high-skilled labour provides crucial direction for digital innovation, playing an indispensable role in the innovation process due to their specialised knowledge (Deist et al., 2023; Huang & Gao, 2023). Fourth, skills training serves as a key pathway to enhance employees' adaptability to new technologies. It not only bridges the gap between existing skills and company requirements but also fosters continuous learning and innovation. Drawing on the methods of Chen et al. (2024a) and Jiang et al. (2024), we use employee education, work environment, skill levels and skills training to characterise human capital allocation. Notably, skills training may have endogenous relationships with other human capital variables. In the digital age, the job market is transitioning towards higher human capital, with individuals in low-skill positions at risk of job loss due to automation. Prompting a need for retraining to transition into high-skill positions (Goos et al., 2014). To isolate the independent effect of skills training, this paper adopts the residual dimensionality reduction method inspired by Richardson (2006) and Luo et al. (2011). Specifically, we regress skills training against other proxies of human capital allocation and extract the regression residuals to represent skills training, thereby capturing the portion of skills training that is not explained by other human capital factors.

Control variablesAmong the control variables used in this study are: firm size (Size), years listed (Age), profitabilit (ROA), liquidity ratio (CUR), proportion of fixed assets (Fix), market competition level (Lerner), and nature of property rights (State). Table 2 provides the definitions of the main variables in this study.

Model constructionDrawing on the research of Xiao et al. (2022), to test the impact of digital innovation on firms' labour share, as stated in Hypothesis 1, this paper constructs Model (1) for benchmark regression analysis. In this model, i denotes the firm, t represents the year. The key independent variable Dig is the firm's level of digital innovation for the current year, and the dependent variable LS is firm's labour share for that year. εitrepresents the random error term. Controls refer to the set of control variables. To mitigate the potential influence of firm-specific factors and time trends, the analysis includes firm fixed effects and year fixed effects. To address heteroscedasticity, robust firm-level clustering of standard errors is employed. A significantly positive coefficient for the explanatory variable (Dig) suggests that digital innovation has a substantial positive effect on the labour share, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1.

Data selectionIn this paper, the listed companies in China's Shanghai and Shenzhen A-shares are selected as the initial research sample from 2012 to 2022, and the sample is screened and processed according to the following principles: (1) excluding samples that have been ST or PT; (2) excluding samples that are insolvent; (3) excluding samples in the financial industry; (4) excluding samples that have missing relevant variables; and (5) applying the upper and lower 1 % for continuous variables to the Winsorize shrinkage treatment. After screening by the above criteria, the final unbalanced panel data of 20,025 year-firm sample observations for 2813 listed companies are obtained. The data sources for the initial samples are divided into two main categories: first, most of the data about firms' financial indicators and governance structure come from the CSMAR database and are supplemented using the Wind database; second, information about firms' patent-specific data, such as summaries, comes mainly from China National Intellectual Property Administration.

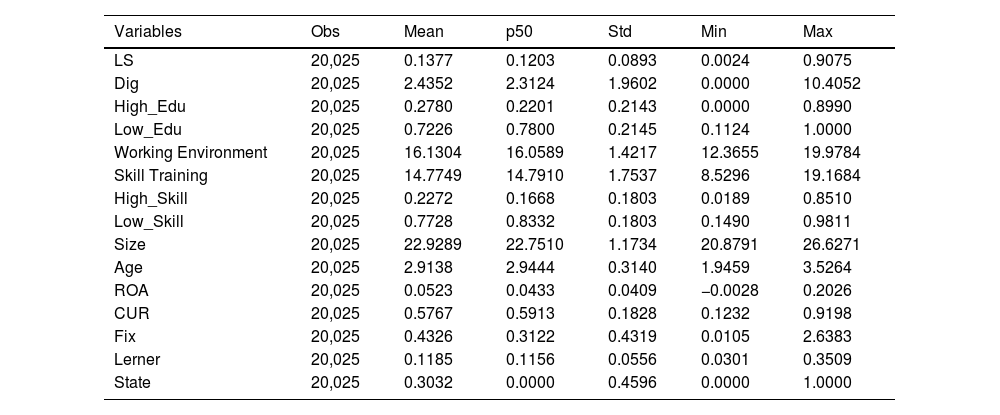

Table 3 presents the main descriptive statistics for the explanatory, explained, mediating, and control variables used in this study. The average digital innovation score for firms is 2.4352, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 10.4052, and a variance of 1.9602. This indicates significant variations in the levels of digital innovation among firms, with some yet to engage in digital innovation. The mean labour share is 0.1377, ranging from 0.0024 to 0.9075, showing pronounced differences in labour shares across firms.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

Using the framework outlined in Model (1), this paper tests the direction and strength of the role of digital innovation in influencing enterprises' labour shares. In Table 4, column (1) demonstrates the initial test of univariate variables; column (2) builds on this by including firm-level and industry-level control variables to correct for potential disturbances; and column (3) further controls for year and firm fixed effects. All of the above results show that the regression coefficients between the digital innovation (Dig) and labour share (LS) are always significant and positive at the 1 % level of statistical significance. Understanding from the economic sense, taking the estimation results in column (3) as an example, for every 1 % increase in digital innovation, enterprises' labour share will be raised by 0.16 %. Based on the above analysis, both in terms of statistical significance and economic significance analysis, it confirms that digital innovation, as a revolutionary innovation force, can effectively promote the upward movement of labour share and lead to the benign adjustment of the income distribution structure within the enterprise. Therefore, H1 is proved.

Digital innovation and enterprises' labour share.

Note: Robust standard errors clustered to the industry level are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significant at the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % levels, respectively. The following tables are identical.

(1) Instrumental variables approach

According to tournament theory, moderate intra-firm income differences can motivate employees to intensify R&D and innovation competition, so there may be a reverse causality problem between digital technology innovation and intra-firm income distribution. Goldsmith-Pinkham et al. (2020) design ideas in constructing Bartik instrumental variables, we adopt the instrumental variable method to mitigate the endogeneity problem that exists in the benchmark regression results. The specific construction method of the Bartik instrumental variable in this paper is to utilize the product of the level of digital technology innovation in the lagged period and the number of digital patent applications at the U.S. level in year t as an instrumental variable for the level of digital technology innovation in the U.S. (USApp). The main considerations for selecting this instrumental variable are as follows: on the one hand, changes in the number of digital patents between different countries will not easily affect the number of digital patents at the enterprise level in another country, which meets the exogenous criteria required for instrumental variables. On the other hand, the scale of China's digital economy development and patent investment funds ranked first and second in the world with the United States respectively,1 indicating that the level of digital technology innovation between the two countries shows strong consistency, which meets the correlation criterion required by the instrumental variable.

The results of the two-stage least squares regression are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 4. The first-stage results presented in column (1) show that the instrumental variable for the level of digital technology innovation in the United States (USApp) and the explanatory variable (Dig) are significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating that the instrumental variables selected in this paper meet the conditions for relevance. The second-stage regression results reported in column (2) show that the level of digital technology innovation (Dig) and the share of firms' labour income (LS) remain significantly positive at the 1 % level after the inclusion of the instrumental variable, suggesting that the research hypothesis H1 of this paper remains robust after mitigating the effects of endogeneity problems due to reverse causation. In addition, the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic of 316.476 rejects the hypothesis of insufficient identification of instrumental variables at the 1 % significance level, and the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic of 546.27 is greater than the critical value of the Stock-Yogo weak instrumental variable identification test at the 10 % significance level, rejecting the weak instrumental variable original hypothesis, confirming the validity of the selected instrumental variables.

(2) PSM-DID

This paper employs a combination of Propensity Score Matching (PSM) and the Difference-in-Differences (DID) method (PSM-DID) to identify the impact of firms' engagement in digital innovation activities on their labour shares, thereby mitigating endogeneity issues. First, based on firm characteristics measured by various control variables (Controls), a Logit model is used to calculate the propensity scores for each sample firm. The treatment group is defined as firms that have at least one digital patent application, with the remaining firms serving as the control group. Subsequently, a 1:2 nearest neighbor matching (NNM) with replacement is employed to find the optimal control group for the treatment group, and non-common support samples are excluded to obtain a new dataset. Considering the sensitivity of propensity score matching, in addition to 1:2 nearest neighbor matching with replacement, kernel matching (KM) and caliper matching (CM) are also conducted.2 After the matching process, in the sample post-PSM treatment, the treatment group firms have more similar characteristics to the control group firms in the year prior to engaging in digital innovation, making the digital innovation behavior of the sample firms more akin to a quasi-natural experiment setting. Thereafter, a Difference-in-Differences Model (2) is constructed to re-examine the impact of digital innovation on firms' labour shares. In this model, the variable Treat is a dummy variable constructed based on the industry-year median of digital innovation levels, and Post takes the value of 1 after the firm's first digital innovation activity, otherwise 0.

The test results presented in Table 5, columns (3)-(5), show that the estimated regression coefficients for the interaction term Treat × Post from Model (2) are significantly positive. This indicates that after employing the PSM-DID method to identify the impact of digital innovation on firms' labour shares, the findings of this paper remain valid, thus reiterating the robustness of the baseline results.

Results of endogenous treatment.

Note: L. represents the number of lag periods of variables.

(1) Quantile regression

Considering that the previous section explores the average effect of digital technology innovation on firms' labour shares, it does not note the characteristic fact that the gap in labour shares varies considerably across firms. Referring to Coad and Rao (2008), this part selects five more representative quartiles of 10 %, 25 %, 50 %, 75 %, and 90 % to examine the robustness of the test conclusions at different quartile levels and to analyze whether there is a corresponding difference in the impact effect of digital technology innovation on labour share among enterprises with various initial income distribution gaps. Compared with simple OLS regression, quantile regression can not only describe the entire conditional distribution of the explanatory variables, analyze the average effect of the impact of digital technology innovation on labour share and how it differs among enterprises with different labour shares, but also avoid the strong assumption that the relevant error terms are equally distributed at all points of the conditional distribution (Koenker & Bassett, 1978).

The quantile regression results are shown in Table 6. The estimated coefficients are positive at the 1 % significance level for all of the five quantiles, confirming the robustness of the previous benchmark regression results. Further analysis reveals that the lower the quantile, the higher the regression coefficient of digital technology innovation (Dig), which implies that firms with low labour shares can achieve more progress in income distribution within the firm by enhancing digital technology innovation compared to firms with high labour shares. The explanation for this result may be due to the fact that, first, according to the latecomer's advantage proposed by Gerschenkron, the latecomer can accelerate its own development by learning from the experience of its predecessor, avoiding its mistakes, and directly adopting more advanced technologies and production methods. As enterprises in the low-income distribution start from a lower base, these enterprises have more potential space for adopting digital technology innovation, and the introduction of digital technology can more significantly improve production efficiency and optimize processes, reduce labour costs (Chen et al., 2024a), and thus have a more pronounced uplift effect on the labour share. Second, compared with large enterprises that have solidified a high income distribution structure, enterprises with low income distribution may be more sensitive to cost control, and the application of digital technology can directly reduce operating costs and increase profit margins (Liu et al., 2023), which gives enterprises a greater incentive to transfer part of this gain to employee compensation, thus raising the share of labour income. Third, governments often tend to incentivize the application of technological innovations in SMEs through policies such as subsidies and tax incentives to promote balanced economic development. These external supports directly or indirectly promote the accelerated adoption of digital technologies by firms with low labour shares, which in turn leads to an increase in the income level of employees through technological spillovers.

(2) Replacement variable measurement

Quantile regression results.

Considering potential measurement biases in the core variables, we employ three methods to remeasure them and assess robustness through regression analysis. For the core explanatory variable, we use the count of digital patent grants (GDig) as a proxy for digital innovation for robustness testing (Fang & Liu, 2024). For the dependent variable, labour share, we adopt two alternative measurement approaches: initially, following Xiao et al.(2022)'s method, we recalculate labour share using the formula "(Cash paid to employees - Beginning accrued employee compensation + Ending accrued employee compensation) / Operating revenue", named LS1. Secondly, to address the measurement bias due to the inherent interval constraint [0, 1], we apply a logistic transformation, taking the natural logarithm of LS/(1-LS), based on Chen et al. (2024a), to expand the indicator to the entire real number domain, termed LS2. These new labour share indicators are included in Model (1) for regression analysis. The results in Table 7, columns (1)-(3), show that the regression coefficients for digital innovation (Dig) remain significantly positive, indicating robust empirical findings consistent with previous conclusions, regardless of the measurement used.

(3) Breakdown of digital patent indicators

Other robustness test results.

Considering the different patent categories, there are differences in the quality level of enterprise technological innovation refracted, among which invention patents are usually regarded as the most representative of the high quality level of enterprise technological innovation (Huang et al., 2021). In this paper, digital patents are further subdivided into invention patents (IDig) and utility models patents (UDig) divisions, and based on the model (1) of this paper, the impact of digital technology innovation on firms' labour share is examined sequentially. The regression results in columns (4) and (5) of Table 7 show that digital invention patents and digital utility model patents have passed the significance test, indicating that different patent categories have positive effects on the share of enterprise labour income, which once again verifies that the findings of this paper's research hypothesis H1 are basically robust. Further, based on the regression results, the regression coefficient of digital invention patents (IDig) is 0. 0019 at 1 % significance level, while the regression coefficient of digital utility model patents (UDig) is 0.0007 at 10 % significance level, indicating that the positive driving effect of digital invention patents (IDig) is significantly larger than that of digital utility model patents (UDig). This result reveals that digital invention patents, as a substantial innovation, are more capable of realizing key technological breakthroughs than strategic innovations, thus leading to the improvement of revenue distribution within enterprises.

(4) Excluding sample selection bias

When analyzing the dynamic impact of enterprises' digital technology innovation and labour share development, the role of macro-environmental factors such as the adjustment of the patent regulation system and industrial policy orientation should not be ignored. For instance, after major policy reforms are implemented, enterprises may need to choose their own development direction and their willingness to invest in digital technology may also differ. Based on this, this paper examines the sample data by combing the reform initiatives that may have a potential impact on the main explanatory variables during the same period and selecting the sample data after eliminating the possible influencing factors in order to verify the robustness of the regression results presented in the previous paper.

Specifically, to begin with, the time series of the sample data, the 2014 "Deepening the Reform Plan of the Salary System for the Heads of Central Management Enterprises" carried out a major reform of the salary system for the heads of central management enterprises. This document aims to control the phenomenon of excessive executive compensation, reduce the income gap, and stipulate the salary structure and assessment mechanism, to promote the balance between fairness and efficiency. Considering that in this context, the explained variables in this paper will have a certain impact. In order to test the aftereffect of income distribution changes, this paper selects the sample data after 2014 for the robustness test. What's more, given the rapid iteration of digital technology, enterprises will continue to generate and accumulate significant patent results as they implement digital technology (Tao et al., 2023). There exists a significant patent divide between the head firms and the following firms in the field of digital technology because the patents held by the head firms are dominant. In light of this, this paper makes two adjustments based on Model (1) in order to mitigate the impact of sample selectivity on the potential bias of the estimation results: first, all data prior to 2014 has been deleted; second, all firms ranked in the top five for digital patent applications in the calendar year have been excluded. The results of columns (6) and (7) in Table 7 show that the significant coefficients of Dig are still both significantly positive, consistent with the previous benchmark regression results.

Mediating mechanism of human capital allocationThe preceding theoretical analysis suggests that advancements in digital innovation enhance a firm's labour share by optimising the allocation of human capital. In practice, factors such as educational background, work environment, skill structure and skills training reflect how well internal talent allocation within firms adapts to market trends and strategic adjustments. Specifically: First, educational background serves as a crucial indicator of employees' fundamental qualities. Higher levels of education typically correlate with stronger learning capabilities and broader knowledge bases, which are essential for swiftly mastering new technologies. Existing research indicates that highly educated employees possess comparative advantages in adjusting to and implementing new technologies (Bartel & Lichtenberg, 1985). Consequently, in the context of rapid digital advancement, companies that prioritise employees' educational backgrounds are more likely to achieve effective human capital allocation. Second, the work environment directly influences employee job satisfaction and productivity. A positive work environment not only enhances job satisfaction and loyalty but also fosters knowledge sharing and team collaboration, both of which are vital for driving innovation (Amabile et al., 1996). Particularly in the digital age, a supportive and open work environment stimulates employees' creativity and problem-solving abilities, thereby impacting labour share and overall performance. Third, skill structure refers to the combination and distribution of various types of skills within a company. An appropriate skill structure is significant for long-term corporate development. As market demands evolve and technology progresses, companies must continuously adjust their skill structures to maintain competitive advantages. Firms with more diversified and advanced skill structures are often better positioned to respond to market changes, thereby achieving higher labour shares (Xiao et al., 2022). Fourth, skills training provides enterprises with a platform for continuously enhancing employees' skill levels. As digital innovation progresses and the pace of technological updates accelerates, companies require higher technical capabilities from their employees. Through ongoing skills training, employees can better adapt to technological changes, thereby optimising human capital allocation (Xiao et al., 2022).

Acknowledging the intrinsic limitations of the traditional three-stage mediation model in causal inference, this paper employs Sobel's test and Bootstrap test (with 1000 replications) to further substantiate the regression outcomes, thereby enhancing the integrity and reliability of the mediation analysis. Consequently, building on Model (1), we have developed the following mediation mechanism model. Here, Mediatoritdenotes the mediating variable, while the definitions of other variables remain consistent with those in Model (1).

Educational backgroundThe enhancement of digital innovation has contributed to the increase in the labour share of firms by raising the proportion of highly educated talent while reducing the share of employees with lower levels of education. Table 8, columns (1) to (4), present the regression analysis results with employee educational background as the mediating mechanism. Specifically, in Table 8, column (1), the regression coefficient of the proportion of highly educated employees on digital innovation is significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating that the progress in digital innovation attracts a higher caliber of talent to firms. In column (2), the regression coefficient of the proportion of highly educated employees is significantly positive at the 1 % level, suggesting that an increase in the educational level of employees significantly promotes the labour share. Additionally, the Sobel Z-statistic is significant at the 5 % level, and the Bootstrap confidence interval for the mediating effect does not include zero, confirming the effectiveness of the mediating mechanism; that is, digital innovation increases the labour share by expanding the pool of highly skilled talent.

Mechanism test 1.

Concurrently, Table 8, column (3), shows that the regression coefficient of the proportion of less educated employees on digital innovation is significantly negative at the 1 % level, implying that digital innovation discourages the entry of less skilled labor. In column (4), the regression coefficient of the proportion of less educated employees is significantly negative at the 5 % level, indicating that as firms advance in digital innovation, job positions require higher skills and educational backgrounds, thereby reducing the demand for less skilled labor. The Sobel Z-statistic is significant at the 5 % level, and the Bootstrap confidence interval for the mediating effect also excludes zero, reaffirming the effectiveness of the mediating mechanism; digital innovation optimizes the educational structure of the workforce by reducing the number of less skilled employees, thereby enhancing the labour share.

Work environmentThe advancement of digital innovation positively impacts the labour share of firms by improving the work environment. Tables 8, columns (5) to (6), display the regression analysis results with the work environment as the mediating mechanism. According to the results in column (5), the coefficient of the work environment on digital innovation is significantly positive at the 1 % level, signifying that digital innovation significantly enhances the work environment. In column (6), when the work environment is introduced as a mediating variable, its regression coefficient remains significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating that an improved work environment can significantly boost the labour share. A higher quality work environment can increase employee satisfaction and productivity, thereby contributing to higher labour remuneration and an increase in the overall labour share of the firm. Moreover, the Sobel test's Z-statistic is significant at the 1 % level, and the Bootstrap confidence interval for the mediating effect does not contain zero, further validating the effectiveness of the work environment as a mediating mechanism. This suggests that digital innovation effectively promotes the growth of the labour share through the pathway of improving the work environment.

Skill structureThe enhancement of digital innovation has increased the labour share of firms by raising the proportion of high-skilled workers while reducing the share of low-skilled employees. Columns (1) to (4) in Table 9 present the regression analysis results with the skill composition of employees as the mediating mechanism. In column (1), the regression coefficient of the proportion of high-skilled employees on digital innovation is significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating that digital innovation significantly attracts high-skilled talent to firms. Additionally, in column (2), the regression coefficient of the proportion of high-skilled employees is significantly positive at the 1 % level, suggesting that an increase in the skill level of employees promotes the growth of the labour share. Furthermore, the Sobel Z-statistic is significant at the 5 % level, and the Bootstrap confidence interval for the mediating effect excludes zero, confirming the effectiveness of this mediating mechanism; that is, digital innovation enhances the labour share by strengthening the high-skilled workforce.

Mechanism test 2.

On the other hand, Table 9, column (3), shows that the regression coefficient of the proportion of low-skilled employees on digital innovation is significantly negative at the 1 % level, implying that digital innovation discourages the entry of low-skilled labor. Moreover, column (4) reveals that the regression coefficient of the proportion of low-skilled employees is significantly negative at the 1 % level, indicating that as firms advance in digital innovation, the proportion of low-skilled employees significantly decreases. The Sobel Z-statistic is significant at the 5 % level, and the Bootstrap confidence interval for the mediating effect also excludes zero, reaffirming the validity of the mediating mechanism. Therefore, the mechanism tests suggest that digital innovation increases the labour share through a "polarization" effect, characterized by the premium on high-quality employees and the marginalization of low-quality labor, thereby raising the proportion of high-skilled employees while lowering the proportion of low-skilled employees.

Skill trainingAdvancements in digital innovation boost firms' labour shares by enhancing skills training, as shown in Table 9. In column (5), the significant positive coefficient on the interaction term between skills training and digital innovation at the 1 % level implies that digital innovation progress prompts firms to invest more in skills training. This reflects the emphasis on employee skill enhancement during digital transformation to meet new technological demands. In column (6), the significant positive coefficient on skills training at the 5 % level suggests that more frequent and higher - quality internal training drives labour share growth. Increased skills training improves employees' professional abilities, work efficiency, and innovation capabilities, positively impacting the company's labour share. Moreover, the Sobel Z - statistic's significance at the 5 % level and the Bootstrap confidence interval for the mediating effect not containing zero confirm the effectiveness of this mechanism. Thus, skills training effectively transmits digital innovation's positive impact on firms' labour shares as a mediator.

Additionally, large enterprises tend to focus more on strategic planning compared to smaller businesses, highlighting differences in skill development approaches due to varying sizes (Witek-Crabb, 2019). Conversely, labour-intensive firms face rising labour costs and, as a result, experience greater cost pressures. These firms often prefer to promote technological advancements through skills training to enhance labour productivity and overcome the bottlenecks caused by high costs (Agrawal & Matsa, 2013). Therefore, considering that the impact of skills training on labour share may differ by firm size and industry characteristics, this paper explores these differential manifestations. To differentiate between firm sizes, we follow the approach of Chen et al., (2024b) and use year-end total assets as a benchmark, categorizing firms into large and non-large based on the annual industry median. For industry heterogeneity, using the China Securities Regulatory Commission's 2012 industry classification standard, we employ two indicators: the fixed asset ratio (net fixed assets/average total assets) and the R&D expenditure-to-payroll ratio (R&D expenditure/payroll). We classify industries into labor-intensive, capital-intensive, and technology-intensive categories using cluster analysis based on the sum of squared deviations. Industries with a higher fixed asset ratio are classified as capital-intensive, reflecting the dominance of capital elements. Those with a higher R&D expenditure-to-payroll ratio are categorized as technology-intensive, indicating the core value of R&D to the enterprise. The remaining industries are classified as labor-intensive. Subsequently, capital-intensive and technology-intensive industries are grouped together as non-labor-intensive industries for regression analysis against labor-intensive industries.

The results are summarised in Table 10. Columns (1)–(2) indicate that in large enterprises, skills training, as a key component of human capital allocation, has a significantly positive effect on labour share. Liao et al. (2024) find that firms require a certain level of innovation capability and a substantial number of technical talents to undergo digital transformation. Large enterprises possess stronger human resource integration and training capabilities, leading to higher levels of technological innovation (Aboal et al., 2015). In contrast, small and medium-sized enterprises face constraints in attracting top talent and exhibit weaker competitiveness, making them more sensitive to the complexities and uncertainties of digital technologies (Jia et al., 2024). Thus, in the context of digital innovation, improved human resource allocation better adapts to the application and management of new technologies, optimising internal resource allocation and consequently promoting an increase in labour share. Columns (3)–(4) further reveal differences across industry characteristics, demonstrating that skills training has a more pronounced positive effect on labour-intensive industries. Similar to the findings of Chen and Zhang (2021), labour-intensive firms benefit more from digital enhancements. This is because labour-intensive industries rely heavily on low-skilled labour, and skills training directly enhances workers' operational skills and efficiency (Dai et al., 2022). Technological applications help replace low-skilled labour, reduce production costs and improve product quality, thereby indirectly increasing the labour share.

Heterogeneity analysis of skill training on labour share.

Given the potential endogeneity issues between the proxy variables for human capital allocation and labour share, we employ the instrumental variable method to test for endogeneity in the mediation effect model. Drawing on the approach by Li et al. (2023b), we select the annual median values of educational background, work environment, skill structure and skills training from all other firms within the same industry and year, excluding the firm itself, as the corresponding IVs. On one hand, companies within an industry typically face similar technological demands, market competition and policy environments, leading to convergent human capital allocation strategies (Zhao & Wang, 2024; Zheng et al., 2022), which satisfies the relevance criterion for IVs. On the other hand, calculating the median values of these variables from other firms does not directly affect changes in the labour share of the focal firm, thus meeting the exogeneity requirement for IVs. Table 11 presents the results of the endogeneity tests for the mediation models. In column (1), the first-stage regression shows that the instrumental variable (Educational background_IV) is significantly and positively correlated with the mediator variable (Educational background) at the 1 % level, indicating the relevance of the selected instrumental variable. Additionally, the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic is 91.54, rejecting the hypothesis of under-identification at the 1 % significance level. The Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic is 115.66, far exceeding the critical value for weak instrument tests by Stock-Yogo, confirming the validity of the instrumental variable. In column (2), the second-stage regression shows that even after adjusting for the instrumental variable, the positive impact of educational background on the firm's labour share (LS) remains significant at the 5 % level. This indicates that after accounting for endogeneity issues, educational background remains a crucial factor in enhancing the firm's labour share, validating the robustness of our research conclusions. Similarly, for work environment, skill structure, and skills training, we conducted instrumental variable tests, and the results consistently show that the relationships with the firm's labour share remain significant and robust after controlling for endogeneity issues.

Endogenous test of mechanism variables.

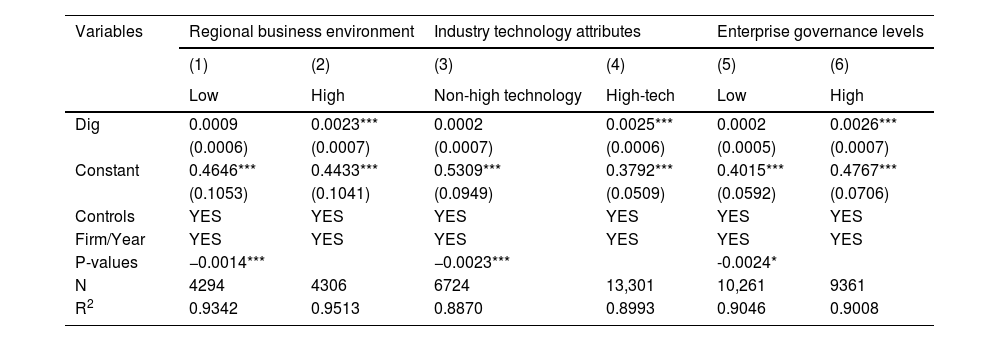

The empirical findings presented above indicate that digital innovation enhances labour share; however, the extent of this effect varies across regions, industries and enterprise characteristics. A comprehensive examination at macro, meso and micro levels will investigate the diverse pathways through which digital innovation promotes labour share within firms.

Heterogeneity in regional business environmentsDue to variations in the business environment across different regions, digital innovation may demonstrate significant heterogeneity in its impact on firms' labour share. The business environment serves as a comprehensive reflection of the regional institutional framework and resource support, indicating the institutional transaction costs faced by firms, the level of policy backing and the efficiency of resource allocation (Ma & He, 2024). In regions with a favourable business environment, governments reduce administrative barriers, optimise financing channels and strengthen intellectual property protection to attract investment, encourage competition and create employment opportunities. This provides more effective institutional guarantees and innovation incentives for corporate digital transformation (Luo et al., 2023), thereby amplifying the positive impact of digital technologies on labour share. To measure the business environment, this paper uses the "China Urban Business Environment Assessment" score from the Open Research Data Platform of Peking University, which comprehensively reflects regional institutional transaction costs and innovation support levels. Additionally, we divide the sample into two groups based on the annual median business environment score: regions below the median are classified as having a "poorer" business environment, while those above or equal to the median are classified as having a "better" business environment. Regression results in columns (1) and (2) of Table 12 show that in regions with a poorer business environment, the variable Dig does not significantly affect firms' labour share. However, in regions with a better business environment, the coefficient of the variable Dig is positive and significant at the 1 % level. Furthermore, the Fisher test's between-group coefficient p-value (based on 1000 bootstrap samples) is also significant at the 1 % level. This indicates that in regions with a better business environment, digital innovation plays a more prominent role in increasing firms' labour share.

Heterogeneity analysis results.

The heterogeneity in these results can primarily be attributed to several factors. First, in regions with a less favourable business environment, frequent personnel turnover and institutional friction significantly increase firms' transaction costs (North, 1991). These non-productive costs crowd out R&D budgets, leading managers to favour investments in lower-risk, short-term incremental technological improvements rather than the long-term resource commitments required for digital innovation projects. While this strategy may sustain firms in the short term, it inhibits the profound enhancement of total factor productivity through digital technologies, resulting in a low-level development of labour share. Second, from the perspective of the resource-based view, a firm's sustainable competitive advantage arises from the strategic allocation of scarce resources (Barney, 1991). In regions with a more favourable business environment, firms can efficiently utilise data assets and market information, accurately identifying the synergies between digital technologies and consumer demand. This not only enhances innovation returns but also directs value-added portions towards workers through performance-based pay and stock option incentives, creating a positive feedback loop of "innovation input - market value addition - labour sharing".

Heterogeneity in industry technology attributesThe varying degrees of technological intensity across industries result in significant heterogeneity in the impact of digital innovation on increasing corporate labour share. High-tech industries, characterised by their strong reliance on knowledge capital, rapid technological iteration and substantial R&D investment, possess robust capabilities in applying and absorbing digital technologies. Their innovation efforts typically focus on developing cutting-edge technologies and enhancing production efficiency. Accordingly, this paper categorizes industries such as general equipment manufacturing, specialized equipment manufacturing, transportation equipment manufacturing, electrical machinery and equipment manufacturing, computer and other electronic equipment manufacturing, telecommunications equipment manufacturing, instrument manufacturing, and cultural and office machinery into high-tech industries based on the National Bureau of Statistics' industry classification standard (GB/T4754). Other industries are classified as non-high-tech industries. In columns (3) and (4) of Table 12, the positive impact of the variable (Dig) on labour share is statistically significant only in high-tech industries at the 1 % level, with the inter-group coefficient difference test's P-value also being positive and significant at the 1 % level. Similar to the conclusions of Liu et al. (2023), the effect of digital innovation is stronger in high-tech enterprises. From an economic perspective, this is because high-tech industries have a higher elasticity of substitution between capital and labor, enabling them to more effectively utilize digital technology to replace traditional labor, thereby enhancing overall labour productivity and corresponding labour compensation.

The industry-level heterogeneity can be attributed to two primary factors. First, high-tech industries generally exhibit stronger technology absorption capabilities and greater potential for productivity growth. According to Solow residual theory, technological innovation is a primary driver of long-term economic growth. In high-tech industries, digital innovation not only directly enhances production efficiency but also indirectly boosts productivity by optimising management and operational processes. High-tech industries must rapidly respond to market changes, meaning that digital innovation helps maintain competitiveness (Verhoef et al., 2021), translating competitive advantages into higher labour remuneration and increasing labour share. Second, digital innovation tends to elevate the demand for highly skilled labour while reducing reliance on low-skilled labour. Based on the theory of skill-biased technological change, technological advancements, particularly in information technology, increase the relative demand for highly skilled workers (Strazzullo, 2024), leading to a rise in their wage premiums. This effect is especially pronounced in high-tech industries, which require a substantial number of highly skilled talents to support ongoing technological innovation and product development. Therefore, digital innovation facilitates the upgrading of human capital, increases the labour share of highly skilled employees and may simultaneously reduce the proportion of low-skilled employees.

Heterogeneity in enterprise governance levelsThe influence of digital innovation on labour share may vary according to a company's governance level. Generally, firms with robust governance structures are more adept at leveraging digital innovation, formulating clear technology strategies and demonstrating stronger execution capabilities. Corporate governance constitutes a complex adaptive system, with traditional assessments of governance performance often relying heavily on singular financial metrics (Huang & Su, 2023). Existing literature highlights the impact of non-financial factors, such as shareholder voting rights and transparency, on the effectiveness of corporate governance (Kasbar et al., 2022; Sauerwald et al., 2016). Following the approach of Hong et al. (2023), we derive a corporate governance score using principal component analysis based on seven variables: the shareholding ratio of the second to tenth largest shareholders, board size, supervisory board size, executive shareholding ratio, number of board meetings, total compensation of the top three highest-paid executives, and whether the roles of CEO and chairman are combined. Higher scores indicate better governance levels. Subsequently, governance levels are divided into two groups based on the industry median. As shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 12, the regression coefficient for digital innovation (Dig) is statistically significant only in companies with high governance levels. The P-value for the between-group coefficient difference test is significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating that in companies with well-established governance mechanisms, digital innovation has a greater impact on increasing labour share. In this sense, governance level is a critical prerequisite for the successful implementation and widespread adoption of digital technological innovations (Li et al., 2024), promoting technological progress to increase labour share and positively affecting corporate economic performance and employee satisfaction.