With the growing complexity and uncertainty of the global supply chain, firms face more severe supply chain risks. This study integrates subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure into a unified analytical framework to explore the impact of supply chain digitalization (SCD) on firms’ supply chain risks. The findings indicate that SCD significantly enhances firms’ subjective risk perception while effectively reducing their objective risk exposure. After conducting robustness checks, the results remain robust. Mechanism analysis suggests that SCD primarily enhances firms’ risk perception and reduces actual risks through information and technological channels. Moreover, this study performs a heterogeneity analysis considering industry monopoly level, internal control quality, and financing constraints, revealing significant differences in the risk mitigation effects of SCD across industries and firm characteristics. Our research provides practical insights for firms in managing supply chain risks during digitalization and offers theoretical guidance for policymakers in formulating relevant strategies.

As market specialization deepens, firms form highly dependent and closely interconnected supply chain networks. While this complex network structure enhances the efficiency of resource allocation and strengthens collaboration among firms in the supply chain, it also exposes them to more significant risks (Ngo et al., 2024; Sajid, 2021). In this context, external shocks and risks are more likely to spread among firms, with any disruption or fluctuation in a single link potentially magnified through the “bullwhip effect,” ultimately leading to systemic risks in the entire network as per the saying, “a single thread pulled can move the whole body” (Dolgui & Ivanov, 2021). In recent years, the growing frequency of geopolitical conflicts, escalation of trade frictions, and recurrence of external shocks, most notably public health emergencies exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, have significantly increased risks to global supply chains (Agca et al., 2023; Bednarski et al., 2025). According to a 2020 report by McKinsey, supply chain disruptions have become the norm, with firms facing a disruption risk lasting 1 month or more every 3.7 years on average and potentially losing >40 % of annual profits every 10 years.1 Furthermore, a 2024 Blue Yonder survey of supply chain executives revealed that 84 % of respondents’ organizations experienced supply chain risks in the past year, resulting in disruptions to production, damage to reputation, and other negative impacts. In response to these risks, 79 % of the surveyed firms have increased their investments in supply chain operations, particularly in digitalization.2 This highlights supply chain risk as a major factor limiting the sustainable development of businesses. In this context, supply chain digitalization (SCD) has gradually emerged as a pivotal method for mitigating this issue (Jackson et al., 2024; Jerome et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2023).

The rapid development of digital technologies has reshaped risk management and operational models in supply chain firms, making them a vital tool for addressing risks (Cai et al., 2024; Marin et al., 2023). With the widespread adoption of digital technologies in supply chain management, firms can achieve the high integration of information, logistics, and financial flows. This facilitates real-time information sharing and intelligent data analysis among different stages of the supply chain, leading to the emergence of the digital supply chain model (Chatterjee et al., 2024). Through this, firms can more accurately identify potential risks and take timely, effective countermeasures (Liu et al., 2024; Mariani et al., 2023). Moreover, SCD enables firms to monitor various uncertainties, and to proactively identify and effectively address the negative impacts of such unforeseen events (Yang et al., 2021; Yavuz et al., 2025). More importantly, traditional supply chain management suffers from issues such as delayed information transmission and asymmetry, resulting in sluggish responses to changes within the supply chain and an accumulation of risks (Choudhary et al., 2025). Through information exchange and flow, SCD breaks down information silos between firms, promoting efficient collaboration among supply chain links (Sharma et al., 2024). The timely flow of information enables each segment of the supply chain to access global data in real-time, allowing for swift responses to unforeseen events, reducing risk exposure due to delayed reactions, and effectively minimizing the occurrence of systemic risks.

Firms are increasingly relying on digital technologies to mitigate supply chain risks. Existing studies confirm the positive impact of SCD on firms’ economic performance (Chatterjee et al., 2024), environmental benefits (Jin et al., 2025), operational models (Hahn, 2020), healthcare delivery (Beaulieu & Bentahar, 2021), green transformation (Fan et al., 2024), sustainable development (Nayal et al., 2022), and technological innovation (Radicic & Petkovic, 2023). Specifically, its role in improving supply chain transparency, flexibility, and resilience has received wide scholarly attention (Feng et al., 2024; Harju et al., 2023; Li et al., 2025; Mishra et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2024). Moreover, the existing literature has examined the main factors contributing to supply chain risks, including economic fluctuations and policy changes (Leung & Sun, 2021), crises and disruptions (Sajid, 2021; Wu, 2024), trade and globalization (Baldwin & Freeman, 2022), technological levels (Jerome et al., 2024), and company management models (Kirilmaz & Erol, 2017). However, research on how SCD affects risks remains relatively limited. While Ivanov et al. (2019) examined the effect of technologies on supply chain risks, they did not analyze it through an SCD lens. As a specific application of digital technologies in the supply chain domain, SCD focuses on the collaborative network across the entire chain, which can more effectively reduce supply chain risks (Luo et al., 2024; Sadeghi et al., 2024). This study analyzes the annual reports of listed firms to measure their subjective risk perception and quantifies their objective risk exposure from a supply-demand balance perspective. We aim to explore how SCD affects firm supply chain risk, through which mechanisms, and how it differentially impacts their subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure.

Here, SCD involves not only the application of individual digital technologies, but also emphasizes cross-departmental and cross-link information sharing and collaboration. As such, its measurement is more complex and often prone to confusion with general digital technology applications (Mishra et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2023). In 2018, the Chinese government launched the Supply Chain Innovation and Application Pilot (SCIAP), providing a valuable quasi-natural experiment for studying SCD. SCIAP identifies SCD as one of the core tasks for pilot firms, requiring them to “apply next-generation information technologies, innovate supply chain technologies and models,” and “play a leading role in enhancing collaboration with upstream and downstream firms in the supply chain.” In 2020, the Chinese government further emphasized the acceleration of SCD development and revealed the typical practices of pilot firms: nearly all have focused on SCD. Therefore, following a study by Ma et al. (2024), we treat SCIAP as an effective attempt at SCD and empirically examine its impact on firm supply chain risks.

This study uses data from Chinese listed companies to explore the impact of SCD on firm supply chain risks, with three main innovations as follows. First, existing studies often characterize supply chain risk through supplier concentration or unforeseen events, focusing on single-dimensional risk assessment and neglecting the diversity and complexity of these risks (Huynh & Le, 2025; Wu, 2024; Ye et al., 2024). This study integrates two distinct risk perspectives and employs text analysis and machine learning techniques to examine firms’ perceptions of subjective supply chain risks as expressed in their annual reports. Furthermore, based on the supply-demand balance perspective and incorporating actual operational data, we objectively measure their actual risk exposure (Bray & Mendelson, 2012). By combining subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure, we enrich the research framework of supply chain risk and offer a novel perspective on how SCD can address the risks stemming from diverse sources and types.

Second, we treat SCIAP as a proxy measure for firm SCD and explore the transmission mechanism through which policy-driven SCD affects firm risk. Previous studies mainly examined factors such as financing capabilities (Qiao & Zhao, 2023), corporate governance (Kirilmaz & Erol, 2017), and financial sustainability (Kumar et al., 2021) when explaining the transmission mechanisms of supply chain risk. However, these factors do not fully explain the underlying reasons for effectively addressing firm risks. Thus, this study examines the micro-mechanisms through which SCD affects firm supply chain risk from information and technological channels. Moreover, we identify heterogeneous scenarios in which SCD enhances firms’ subjective risk perception while mitigating objective risk exposure, including degree of industry monopoly, internal control (IC), and financing constraints (FC). These findings offer empirical evidence to inform the development of firm-specific risk management strategies.

Finally, this study integrates firms’ subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure into a unified theoretical framework, thereby expanding the analytical perspective of supply chain risk management. Existing studies in the fields of behavioral economics and psychology have examined managers’ subjective perceptions of risk (Jackson et al., 2024; Mishra et al., 2023; Sato et al., 2020), whereas the operations management literature has primarily focused on firms’ objective risk exposure from the perspectives of process resilience and supply-demand coordination (Ghadge et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2024). However, these two research streams have developed in parallel, with limited exploration of their theoretical linkages and underlying relationships. Therefore, drawing on the theories of risk perception and organizational information processing, this study clarifies the conceptual boundaries and logical connections between subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure. It further explains how firms can leverage SCD to simultaneously enhance their risk identification and response capabilities, thereby reducing overall risk levels across multiple dimensions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review and theoretical analysis. Section 3 outlines the research design. Section 4 reports the empirical results. Section 5 provides the discussion, and finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

Literature review and theoretical analysisFirms’ supply chain digitalization and risksIn highly uncertain and rapidly evolving supply chain environments, firms’ risk management behaviors are jointly shaped by both subjective perception and objective exposure. According to risk perception theory, managers’ assessments of potential risks are not solely based on the objective conditions of the external environment; instead, they are subjectively influenced by limited attention, cognitive biases, and information acquisition capabilities (Slovic, 1987). Such perceptions affect not only resource allocation, strategic decision-making, and disclosure behaviors, but also determine firms’ behavioral responses to risks in operational contexts (Shu & Fan, 2024). Moreover, firms’ actual risk exposure reflects their structural vulnerability to external shocks within the supply chain system and is influenced by factors such as supply-demand matching capability and operational coordination efficiency (Cai et al., 2024; Kirilmaz & Erol, 2017). Although subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure differ in terms of measurement, they are theoretically interconnected. As organizational information processing theory suggests, when environmental complexity increases, organizations must simultaneously enhance both their information perception and response capabilities to avoid decision-making errors and losses caused by information mismatches or delayed reactions (Belhadi et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2021). Digital technologies are increasingly embedded across all segments of the supply chain, profoundly shaping how firms perceive and respond to supply chain risks (Ivanov et al., 2019; Marin et al., 2023). In this context, SCD enables firms to identify potential risks more sensitively, while also facilitating optimized decision-making and response mechanisms, thereby reducing the likelihood of actual risk exposure (Chatterjee et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025; Mishra et al., 2024). We conceptualize subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure as complementary components within firms’ risk management systems, and develop a theoretical framework to investigate how SCD operates across both dimensions.

On the one hand, SCD enhances managerial sensitivity to external potential risks by reshaping how organizations collect and process information, thereby strengthening subjective risk perception. Risk perception theory posits that individuals’ risk cognition is not solely determined by external signals, but is significantly influenced by psychological mechanisms such as information availability, attention allocation, and cognitive biases (Mishra et al., 2023; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). As such, managers’ perceptions of risk rely heavily on their ability to acquire and interpret information. However, in highly complex supply chain systems, traditional methods of information transmission are often plagued by delays and distortions, limiting managements’ timely detection of supply chain risks (Sato et al., 2020). SCD improves this situation by enabling the development of end-to-end visibility platforms that allow firms to monitor operational activities across all stages, from raw material procurement to product delivery. This significantly increases the accessibility and transparency of information (Kessler et al., 2022; Randall et al., 2014). Managers no longer rely on traditional, delayed information reports, but instead make decisions based on real-time data, significantly improving firms’ subjective risk perception capabilities. Moreover, the intelligent analysis and risk warning systems enabled by SCD can integrate historical data, market trends, and real-time supply chain information to promptly capture risk signals and generate corresponding risk alert reports (Liu et al., 2024; Schwieterman et al., 2018). This enhanced information sensing capability changes the frequency with which managers assess potential risks and significantly increases their inclination to disclose relevant content in public documents such as annual reports (Wu, 2024).

On the other hand, SCD effectively reduces firms’ actual risk exposure by enhancing the accuracy of supply-demand matching and optimizing supply chain response capabilities (Barman, 2024). According to organizational information processing theory, the essence of supply chain risk arises from the mismatches between environmental uncertainty and an organization’s information processing capabilities (Belhadi et al., 2024). Particularly in cases of inaccurate demand forecasting or supply disruptions, the organization’s need for timely and effective information processing increases sharply. If the firm fails to acquire and process critical information with sufficient speed and accuracy, it may face tangible risks such as supply-demand mismatches and inventory imbalances (Ivanov & Dolgui, 2021). Here, SCD helps firms accurately predict changing market demand trends and adjust production plans or inventories through intelligent scheduling systems, thereby avoiding inventory shortages or surpluses caused by fluctuations in demand (Sadeghi et al., 2024). McKinsey’s tracking study of global manufacturing shows that in firms implementing SCD, inventory deviation risk due to information delays has decreased by 30–60 % on average. This outcome fundamentally reflects an improvement in organizations’ capabilities to manage external disruptions more effectively.3 Moreover, SCD enhances coordination efficiency across supply chain nodes by breaking down information silos between upstream and downstream partners (Fan et al., 2024). Through digital platforms, firms can share data with suppliers, logistics providers, and channel partners. In the event of abnormal fluctuations at any node, rapid emergency coordination can be deployed, enabling real-time adjustments in procurement, inventory, or distribution strategies to contain risks at an early stage (Maheshwari et al., 2023). As a result, the likelihood of supply chain disruptions caused by failures or delays in specific links is significantly reduced. Firms are better positioned to maintain operational continuity and balance within their supply-demand systems in highly dynamic environments, ultimately lowering their actual risk exposure (Choudhary et al., 2025).

Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: SCD enhances firms’ subjective risk perception.

H2: SCD reduces firms’ actual risk exposure.

Information channelsIn traditional supply chains, information asymmetry has always been a key factor limiting supply chain efficiency and exacerbating risks (Jung & Kouvelis, 2022; Ni et al., 2021). Due to delays and distortions in the information transmission process, firms at various supply chain nodes often fail to acquire timely and accurate key information from upstream and downstream partners, leading to problems such as delayed decision-making, inventory buildup, and excess production capacity (Primmer, 2024). Particularly under the influence of the “bullwhip effect,” even minor fluctuations in demand from downstream companies are transmitted and continuously amplified throughout the supply chain, resulting in excess capacity or inventory buildup in upstream companies, which triggers supply chain risks (Wu et al., 2024). SCD can effectively reduce the costs of information processing and transmission, alleviating the issue of information asymmetry between firms. By introducing digital technologies, firms enable end-to-end supply chain visualization management (Benzidia et al., 2021; Mariani et al., 2023). This not only helps firms monitor information such as raw material procurement, inventory status, and production progress in real-time, but also enables comprehensive monitoring and feedback of each link’s real-time status, eliminating information blind spots and data silos in traditional supply chain management, thereby significantly enhancing information transparency (Feng et al., 2024).

Signaling theory posits that improved information transparency can mitigate the degree of information asymmetry, enabling market participants to access more accurate and timely risk signals and thereby make more rational decisions (Drover et al., 2018). SCD enhances information transparency, systematically collecting and integrating dispersed and difficult-to-capture risk signals across various links, helping managers more keenly identify risks in external markets and internal operations and thereby strengthening firms’ subjective risk perception (Kessler et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025; Lu et al., 2023). Moreover, improving information transparency directly reduces firms’ objective risk exposure. According to transaction cost theory, SCD effectively mitigates the uncertainty caused by information asymmetry, reducing the additional transaction and monitoring costs incurred by parties due to incomplete information (Cai et al., 2024; Wong et al., 2021). By establishing shared information platforms, SCD enables real-time information sharing and high transparency, reducing decision errors caused by information distortion and significantly lowering firms’ objective risk exposure (Zhou et al., 2025). Furthermore, transparent information systems enable firms to conduct more accurate demand forecasting and risk management, which reduces the likelihood of supply chain risks and significantly shortens recovery time when disruptions occur (Belhadi et al., 2024).

In conclusion, we propose that:

H3: SCD enhances firms’ subjective risk perception and reduces their objective risk exposure through information channels.

Technological channelsAccording to endogenous growth theory, technological innovation is an internal engine driving firms’ long-term and stable development (Dai et al., 2025; Romer, 1990). The theory emphasizes that technological progress is not exogenously given but arises from firms’ continuous optimization of knowledge accumulation, R&D investment, and institutional environments. In this context, SCD reconstructs the innovation ecosystem, enhancing the firm’s technological innovation capabilities through innovation resources, the innovation environment, and innovative talents, which in turn affect the firm’s supply chain risks (An et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2021).

First, endogenous growth theory emphasizes the importance of accumulating innovation resources in enhancing technological capabilities. SCD brings new innovation resources to firms, particularly under the support of the SCIAP policy. Pilot firms receive prioritized access to policy-related resources including funding, digital platforms, and data infrastructure (Luo et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2024). Moreover, firms participating in the SCIAP are more likely to establish partnerships with leading technology providers and research institutions, promoting the integration of digital technologies into supply chain operations (Furstenau et al., 2022). The application of these technologies enhances firms’ ability to perceive potential risks in complex market environments and provides technical support for addressing practical challenges such as supply disruptions and order fluctuations (Yavuz et al., 2025).

Second, a conducive innovation environment is fundamental to sustaining innovation activities and ensuring the stability of innovation outcomes. SCD contributes to the creation of a more open and collaborative innovation network (Radicic & Petkovic, 2023). With support from the SCIAP, firms connect through industry collaboration platforms, enabling efficient information exchange (Di Vaio et al., 2024). This improved environment helps break down information silos, enabling firms to monitor market trends and supply chain dynamics more accurately. As a result, their capacity to anticipate and identify risks under uncertain conditions improves (Meng & Lin, 2025). Moreover, the enhanced innovation environment also improves firms’ responsiveness, enabling faster reactions to external shocks such as supply disruptions, thereby reducing their actual risk exposure.

Finally, endogenous growth theory posits that talent is the primary driver of innovation. The accumulation of human capital directly facilitates technological advancement and knowledge spillovers, which in turn drive endogenous economic growth (McGuirk et al., 2015; Romer, 1990). In the digitalization of supply chains, firms face increasing needs for data processing and complex modeling, which significantly heightens their reliance on professionals skilled in data analytics, predictive modeling, and digital operations (Jerome et al., 2024; Ling et al., 2025). Through resource and platform support, the SCIAP helps firms attract high-level talent, creating a shared talent pool that alleviates workforce shortages (An et al., 2024). SCD also provides conditions for nurturing innovative talent. Through smart training systems, firms can tailor training programs to employee skill levels and job needs, continuously improving workforce expertise and innovation capacity (Alavi et al., 2024; Ogbeibu et al., 2022). The expansion of technologically innovative talent enables firms to more effectively leverage digital tools to identify supply chain risks, simulate potential disruptions, and formulate targeted response strategies (Choi et al., 2019). These capabilities enhance firms’ risk perception capabilities while improving their efficiency in technology adoption and response, ultimately reducing objective risk exposure.

Fig. 1 illustrates the theoretical framework. Based on this, we propose that:

H4: SCD enhances firms’ subjective risk perception and reduces objective risk exposure through technological channels.

Research designEmpirical modelA central challenge in evaluating the impact of the SCIAP on supply chain risk lies in determining whether the selection of pilot firms can be considered exogenous. If the designation of SCIAP pilots is influenced by firms’ pre-existing levels of digitalization or risk exposure, the validity of causal inference may be compromised. To mitigate this concern, we argue for the exogeneity of the SCIAP by examining both the policy rationale and selection process of pilot firms. First, the SCIAP is a top-down strategic initiative at the national level, rather than a voluntary decision made by firms based on their own risk profiles or digital capabilities. Second, the list of selected firms spans a wide range of industries, from highly digitalized sectors such as telecommunications and automotive manufacturing to more traditional ones like agriculture, steel, and non-ferrous metal smelting. It also includes large state-owned enterprises as well as private and regional firms. This indicates that selection was not limited to firms with advanced digital infrastructure or superior governance capacity. Finally, the competent authorities centrally released the list of pilot firms, making it difficult for individual firms to accurately anticipate their selection prior to the policy announcement, thereby reducing the likelihood of any preemptive behavior. Therefore, we treat the SCIAP as an exogenous shock and use the difference-in-differences (DID) method to examine the causal impact of SCD on supply chain risks. The model is specified as follows:

Where SubRiskit and ObRiskit represent the subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure of firm i in year t, respectively. Thescditis the explanatory variable, and its coefficientα1 and β1reflects the causal link between SCD and supply chain risks for firms. Controlitdenotes control variables. ui represents firm fixed effects, ηt denotes time fixed effects, and εi,t is the random error term.

VariablesDependent variableThis study classifies supply chain risks into subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure. Textual data in corporate annual reports often reflect managerial assessments of current risks and forward-looking insights into future challenges, which can capture firms’ subjective awareness and emphasis on supply chain risks (Sautner et al., 2023). Following Ersahin et al. (2024) and Wu (2024), we employ Word2Vec embedding techniques to construct a supply chain-related dictionary, focusing on two key thematic categories: “supply chain” and “risk.” Leveraging text-mining techniques, we develop a subjective supply chain risk perception index by calculating the co-occurrence frequency of supply chain and risk-related terms in close textual proximity. We argue that if a sentence in a firm’s annual report contains both supply chain- and risk-related terms, it is highly likely to reflect discussions of supply chain risk faced by the firm (Hassan et al., 2019).

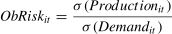

For objective risk exposure, we follow the approach of Bray and Mendelson (2012) and assess the actual supply chain risks firms face by measuring the extent of variance between production and demand fluctuations:

Productionit denotes the firm’s quarterly production volume, measured as the sum of quarterly sales costs and the net inventory balance. Demandit represents quarterly sales revenue, defined as the sum of core operating revenue and other operating income. We measure the firm’s objective risk exposure by comparing the quarterly standard deviation of production volume with demand. A higher ratio indicates a more significant imbalance between supply and demand in supply chains led by core firms, suggesting greater actual risk exposure in the firm’s supply chain.

Explanatory variablesSupply chain digitalization (scd). In April 2018, the Chinese government issued the Notice on Launching the Supply Chain Innovation and Application Pilot Program, officially initiating a nationwide pilot project and ultimately designating 55 pilot cities and 266 pilot firms (Ma et al., 2024). Following Luo et al. (2024) and An et al. (2024), we define the pilot firms as the treatment group and the remaining firms as the control group. Specifically, we construct a policy dummy variable scd, which equals 1 for firm i in 2018 and subsequent years if it was selected as a pilot firm, and 0 otherwise. Although the SCIAP also involves the city level, the role of pilot cities is to provide policy support and create a favorable environment for implementation. As firms are key nodes in the supply chain, using firm-level pilots is more appropriate. In addition, to exclude potential confounders, we further control the policy dummy variable of pilot cities (Citydum).

Control variablesFollowing the study of Chatterjee et al. (2024) and Liu et al. (2024), we select the subsequent control variables for the purposes of this study: firm size (Size), quantified by the natural logarithm of total assets; firm age (Age), quantified by the firm’s listing age; leverage ratio (Lev), namely the proportion of total liabilities to total assets; revenue growth rate (Growth), the ratio of current revenue to previous revenue; board size (Board), measured by the natural logarithm of board members; ownership concentration (Top1), the proportion of shares the largest shareholder holds relative to total equity; and Tobin's Q (Tobinq), the ratio of the market value of equity to total assets.

Data resource and sampleWe focus on Chinese A-share listed companies from 2012 to 2023, following these steps: First, we exclude samples of ST and delisted companies. Second, we remove financial companies and samples with missing key variables. Finally, we winsorize all variables at the micro level. The financial data primarily comes from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) and CNRDS databases. The annual reports of listed firms are downloaded and organized from the CNINFO to construct the firm’s subjective risk perception index. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 2 reports the regression results regarding the impact of SCD on firm supply chain risks. Columns (1)–(2) control only for time and firm fixed effects, revealing that the SCIAP policy significantly enhances firms’ subjective risk perception while reducing objective risk exposure. In columns (3)–(4), the control variables are incorporated, and the coefficient direction and significance of scd remain unchanged. This indicates that after controlling for other factors, SCD still significantly enhances firms’ subjective risk perception while reducing objective risk exposure. Therefore, H1 and H2 are supported.

Benchmark results.

SCD enhances management’s ability to acquire and interpret information. By implementing comprehensive monitoring and real-time feedback systems, it reduces the issues of information blind spots and data silos in traditional supply chain management, thereby significantly improving firms’ subjective perception of potential risks (Kessler et al., 2022; Wu, 2024). This finding aligns with risk perception theory, which posits that firms’ subjective risk assessments are shaped by their capacity to access information and the cognitive boundaries within which they operate (Belhadi et al., 2024). Furthermore, Barman (2024) emphasizes that supply-demand mismatches are a major source of actual supply chain risk. Building on this, we provide evidence that SCD, from a supply-demand balance perspective, enables firms to more accurately forecast market demand trends and effectively reduce their actual exposure to supply chain risks (Sadeghi et al., 2024). This result supports the conclusions of Chatterjee et al. (2024) and Li et al. (2025), namely that SCD improves firms’ responsiveness, and expands on the research of Ivanov et al. (2019).

Parallel trend testThe reliability of the estimation results in this study depends on the assumption that the risk levels of the treatment and control groups followed the same trend before the policy intervention. We perform a parallel trend test using the methods of Beck et al. (2010). Fig. 2 shows no notable disparity in subjective risk perception levels between the two groups prior to the policy intervention. Following the policy intervention, the subjective risk perception in the treatment group markedly increases, thus satisfying the parallel trend. The parallel trend test for objective risk exposure is presented in Fig. 3, and the assumption is similarly satisfied.

Robustness testPlacebo testTo eliminate potential biases caused by external random factors and unobservable variables, we randomly selected the treatment group for a placebo test and repeated this process 500 times. Figs. 4 and 5 present the placebo tests for subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure, respectively. The estimated coefficients from the random selection are concentrated around zero and approximately adhere to a normal distribution. The dashed line in the figures represents the baseline regression coefficient, and the mean significantly deviates from this coefficient, indicating that the placebo test passes.

Propensity score matching methodTo mitigate potential selection bias and systematic differences in the sample, we first apply the propensity score matching (PSM) method to re-select the sample. Specifically, we use control variables as matching features for 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching, followed by re-estimation using the baseline regression model to ensure comparability between the samples, thereby reducing the impact of selection bias on the results. We also introduce entropy balancing to address the potential matching quality issues inherent in traditional PSM methods. The entropy balancing method optimizes weight allocation to ensure that the treatment and control groups have the same distribution of multiple covariates, thereby improving the accuracy of sample matching. Table 3 shows that after applying the PSM and entropy balancing methods, the coefficient for scd remains significant, indicating robust results.

PSM and entropy balance test.

Regarding subjective risk perception, to mitigate potential information loss in textual analysis caused by excessive distance between supply chain and risk-related terms, we broaden the scope for measuring their co-occurrence. Specifically, we recalculate the frequency with which these two categories of terms appear within a 15-word (SubRisk15) and 20-word (SubRisk20) window in the surrounding context. This approach allows us to capture more dispersed expressions of risk in the text, thereby providing a more comprehensive representation of firms’ perception of supply chain risk. The results in columns (1)–(2) of Table 4 indicate that after adjusting the measurement range, the effect of scd on subjective risk perception remains significantly positive.

Robustness test.

For objective risk exposure, we refer to Cull et al. (2009) and measure firms’ objective supply chain risk based on the capital occupation by downstream customers and upstream suppliers. The specific formula is as follows:

Where brit denotes the net notes receivable, arit represents the net amount receivable, prpit represents the net amount of prepayments, and mbiit represents revenue from the core business. A smaller value of ObRisk1it indicates a lower level of objective risk exposure for the firm. The results are shown in column (3). After re-measuring the objective risk indicator, SCD still significantly reduces firms’ objective risk exposure, indicating robust results.

Re-examination based on SCDAs mentioned, SCD denotes the deep integration of modern digital technologies with supply chains. In the baseline regression, we use the SCIAP as a proxy variable for a firm’s SCD. Furthermore, following Zhang et al. (2024), we re-measured SCD (SuDigital) based on the company’s annual report using a text analysis approach. If a company’s annual report contains statements related to digital technologies and SCD, the company is considered to have implemented SCD. A higher intensity of digital technology application indicates a higher level of SCD. In columns (4)–(5), after re-measuring SCD, the results remain robust.

Other robustness testsWe conduct a series of additional robustness checks. First, we incorporate city-level control variables including: economic development (Pgdp), measured as the natural logarithm of per capita GDP; industrial structure (Structure), defined as the ratio of tertiary to secondary industry output; and financial development (Fin), proxied by the ratio of year-end loan and deposit balances to regional GDP. The corresponding regression results are presented in columns (1)–(2) of Table 5. Second, although the immediate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have gradually eased, its disruption to global supply chains remains significant and continues to shape the trajectory of SCD and risk management (Agca et al., 2023). To ensure the robustness of our findings, we shorten the sample period by excluding post-2019 observations and re-estimate the models. The results are reported in columns (3)–(4). Finally, since the list of SCIAP firms was released only in the second half of 2018, the policy effects may be delayed. Therefore, we set the policy intervention point to 2019 and re-estimate the regression, with results reported in columns (5)–(6). After a series of robustness checks, SCD still significantly increases the firm’s subjective perception of supply chain risk and reduces its objective risk exposure, indicating robust results.

Other robustness tests.

The extent of industry monopoly is closely related to market bargaining power, competition, and firms’ risk response ability. The impact of SCD may vary depending on the degree of monopoly (Ahmed & Shafiq, 2022). Therefore, we use the median of the Lerner index to divide the sample into low and high monopoly groups for the regression analysis. The results are presented in Table 6. The results may be because low monopoly firms have weaker market power and are more susceptible to supply chain disruptions or demand fluctuations under intense market competition. SCD enhances the firm’s ability to identify potential risks through risk warning systems and data visualization tools, prompting them to proactively perceive supply chain risks and avoid potential losses (Ivanov et al., 2019). However, due to the limited resource integration capabilities of low monopoly firms, digital technologies often only partially optimize supply chain management, with limited effects on actual risk improvement, and are unable to compete with high monopoly firms.

Heterogeneity of the degree of monopolization.

In contrast, in the high monopoly group, the impact of SCD on subjective risk perception is not significant, but its impact on reducing actual risk is significantly greater than that in low monopoly firms. This may be because high monopoly firms, with stronger market pricing power and control over resources, can deeply embed digital technologies throughout the entire supply chain process, enabling more efficient risk management and effectively reducing actual supply chain risk exposure (Shi et al., 2020). In addition, high monopoly firms typically have a stable market position and strong tolerance for short-term risk, and are less sensitive to risk warning signals. The risk information provided by digital tools has not significantly altered their subjective risk cognition, so the improvement effect at the perception level is limited.

Internal controlsIC serves as the foundation of corporate management and operations, playing a vital role in risk prevention and facilitating the smooth operation of firms (Feng et al., 2015). Typically, high-quality IC enables better utilization of digital technologies, helping firms identify and mitigate risks. To explore the differentiated effects of varying IC quality, we utilize the IC index for listed firms published by DIB, dividing the entire sample into high- and low-quality IC groups based on the median (Chen et al., 2017). The results in Table 7 indicate that for firms in the high-quality IC group, SCD significantly enhances subjective risk perception and reduces objective risk exposure. Conversely, in the low-quality IC group, the impact of SCD is not significant.

Heterogeneity of internal control.

This may be because high-quality IC can more effectively support firms in utilizing SCD tools for risk identification and management (An et al., 2024). An efficient IC can improve the identification and response level of firms’ external risks and reflect their results in annual reports and management decisions. In addition, sound IC helps enterprises reduce information distortion and processing bias when implementing SCD tools, thereby maintaining competitiveness in complex market environments (Monteiro et al., 2023). However, firms with low IC quality usually have more management loopholes and weak links in risk control, making it challenging to achieve efficient information transmission and collaborative operation across departments and links. In such cases, firm management may lack sensitivity to potential issues in the supply chain, weakening the impact of SCD on enhancing subjective risk perception and reducing actual risk exposure.

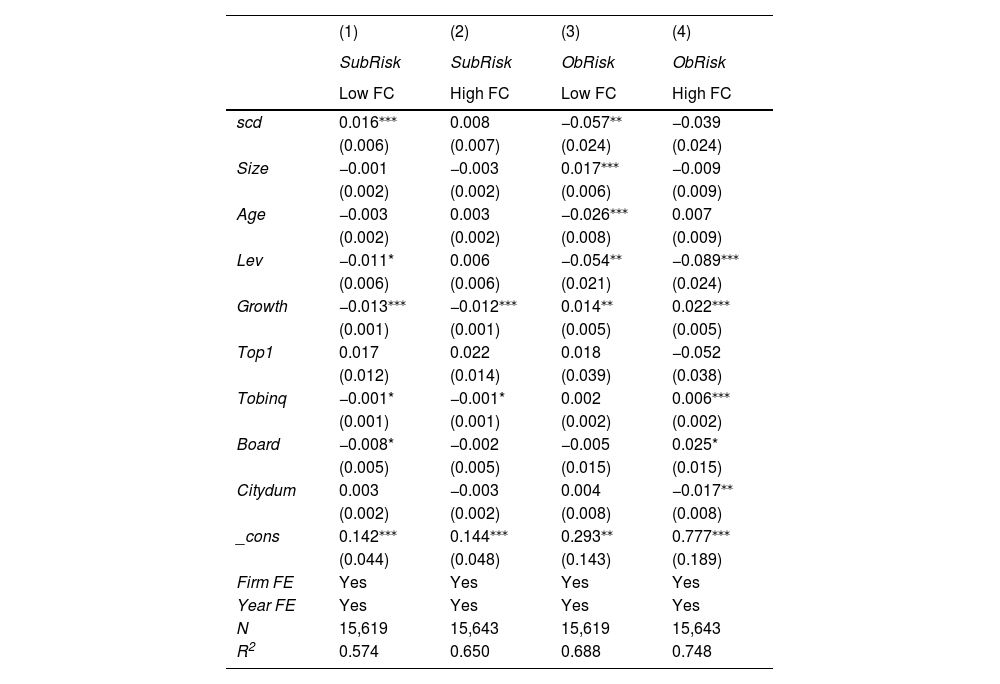

Financing constraintsWe also consider the heterogeneous effects of FC. Specifically, we divide the sample into high and low FC groups based on the median of the SA index for regression analysis. As shown in columns (1) and (3) of Table 8, in the low FC group, SCD enhances firms’ subjective risk perception and reduces actual risk exposure. Columns (2) and (4) show that the impact of SCD on firm supply chain risk is not significant in the high FC group.

Heterogeneity of financing constraints.

This may be because firms with low FC can typically secure more funding, allowing for greater investment in supply chain management and digital technologies. The introduction of advanced equipment enhances firms’ resource integration and risk management capabilities, helping them identify and address supply chain risks more accurately, thereby improving subjective risk perception and effectively reducing actual risk exposure (An et al., 2024). However, firms with high FC face greater financial pressure, with funds prioritized for daily operations and short-term debt servicing, making it challenging to allocate limited resources to potential risk identification and management (Kouvelis & Zhao, 2016). They are often more inclined to adopt short-term strategies to conceal risks to obtain credit support, rather than proactively exposing and addressing risks through digital technologies. Therefore, for firms with high FC, SCD has a limited impact on enhancing subjective risk perception and reducing objective risk exposure.

Mechanism analysisThe previous analysis examined the impact of SCD on firms’ subjective and objective risks. Based on theoretical analysis, SCD can influence firms’ supply chain risk through information and technological channels. We build models (3)–(5) on the baseline regression model to test the mechanisms of information transparency and digital innovation capabilities. The models are as follows:

Mediumit=χ0+χ1scdit+χ2Controlit+ui+ηt+εi,t (3)

Riskit=φ0+φ1scdit+φ2Transit+φ3scdit×Transit+φ4Controlit+ui+ηt+εi,t (4)

Where Riskit represents the supply chain risk of firms, comprising subjective risk perception(SubRiskit)and objective risk exposure(ObRiskit). Transit denotes information transparency, measured by the average sample percentile ranks of five variables based on the methodology in Thong (2018): earnings quality, stock exchange disclosure awards, number of analysts tracking the firm, accuracy of analysts’ forecasts, and whether the auditor is from one of the Big Four. A higher Transitvalue indicates greater information transparency. Techit represents digital innovation capability, quantified by the total number of digital invention patent applications filed by firms in a given year based on the International Patent Classification (IPC) codes from the “Key Digital Technology Patent Classification System (2023)” and the corresponding IPC reference table.

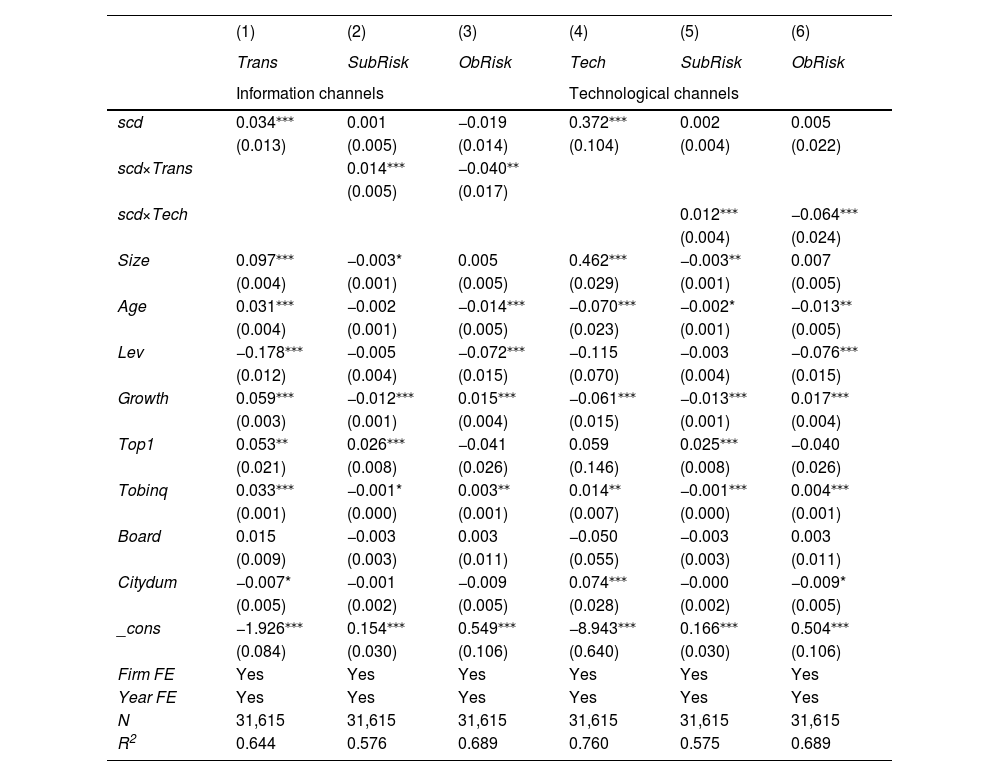

Information channelsColumns (1)–(3) of Table 9 present the outcomes of the mechanism analysis for information channels. Referring to model (3), we examine whether SCD can enhance information transparency. The results are shown in column (1). The coefficient of scd is positive, indicating that SCD has a positive effect on enhancing firms’ information transparency. To further clarify the mechanism of information transparency, we conduct a regression with reference to model (4). In column (2), the coefficient of scd×Trans is positive, indicating that for firms with high information transparency, the impact of SCD on enhancing subjective risk perception is greater. This is mainly because SCD effectively reduces the cost of information processing and transmission through end-to-end supply chain visual management, and alleviates the problem of information asymmetry between firms (Feng et al., 2024; Mariani et al., 2023). This allows them to integrate risk signals scattered across various links and challenging to detect, thereby providing managers with a more rational basis for decision-making (Drover et al., 2018). Through this transformation, firms no longer rely solely on reactive responses but can proactively identify and predict potential risks, significantly enhancing their subjective perception thereof.

Results of the mechanism analysis.

The regression results in column (3) show that SCD significantly reduces firms’ actual supply chain risks by improving information transparency. SCD realizes real-time information sharing and a high degree of visibility, effectively reducing decision-making errors caused by information errors and transmission delays in various aspects of the supply chain, thereby inhibiting firms’ actual risk exposure (Zhou et al., 2025). Moreover, information transparency strengthens the firms’ internal information processing efficiency and optimizes their ability to predict the external environment. Transparent information systems can help firms more accurately forecast demand and manage risks, reduce the probability of supply chain risks, and significantly shorten the recovery time after risks occur (Drover et al., 2018). Thus, as shown, SCD can improve firms’ subjective risk perception and reduce their actual risk exposure through information channels. As such, H3 is verified.

Technological channelsThe regression results in column (4) indicate that SCD enhances firms’ digital technological innovation, confirming its role as a technological channel. The studies by Jerome et al. (2024) and Ma et al. (2024) support this view. Furthermore, we introduce the interaction term scd×Tech into the baseline model, constructing model (5) to test the mechanism of digital innovation capacity. The results in column (5) show that the coefficient of scd×Tech is positive, indicating that SCD can more significantly enhance the subjective risk perception of firms with higher digital innovation capacity. Firms with stronger innovation capacity typically possess more advanced tools for data collection, analysis, and visualization that can extract effective signals from complex supply chain information and enhance risk perception (Meng & Lin, 2025). In addition, the integration of digital technologies allows firms to detect potential risks earlier and reduces decision-making errors stemming from subjective managerial judgment (Furstenau et al., 2022).

Column (6) investigates the mechanism effect of innovation capability on the relationship between SCD and objective risk exposure. The coefficient of scd×Tech is negative, indicating that SCD has a stronger risk-reducing effect in firms with greater technological capability. This is mainly because the application of digital technology not only enhances the perception of potential risks in complex market environments, but also provides technical support for dealing with practical risks such as supply chain disruptions and order fluctuations (Choi et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2024). Technically capable firms can transform SCD into an effective risk management tool, reducing actual risk exposure due to response lag or information mismatch (Belhadi et al., 2024).

DiscussionTheoretical contributionsIn recent years, supply chains have become exposed to uncertainty, drawing growing scholarly attention to firms’ capabilities in identifying and responding to risks. Managers are increasingly aware that traditional risk management approaches based on experience or reactive strategies are insufficient in effectively addressing supply chain risks (Kirilmaz & Erol, 2017). In this context, SCD is viewed as a critical capability that enhances information transparency and technological responsiveness, thereby improving firms’ ability to anticipate and mitigate risks (Cai et al., 2024; Kessler et al., 2022). However, much of the existing literature on digitalization and risk management focuses on process optimization and operational efficiency, while paying limited attention to the intrinsic link between subjective risk perception and objective risk exposure. For example, traditional operations management studies tend to focus on measurable risks such as supply-demand mismatches or logistics disruptions (Barman, 2024; Li et al., 2025), whereas behavioral economics and organizational psychology explore how cognitive limitations and perception biases influence managerial judgment (Slovic, 1987). These two research streams often develop independently, lacking an integrated framework.

To address this gap, our study makes three key contributions: First, we advance risk measurement methodologies within the field of supply chain research. Most existing studies rely on structural indicators or exogenous shock-based proxies, which fail to differentiate between subjective risk perception and objective exposure, or to capture their interactions (Huynh & Le, 2025; Ye et al., 2024). We quantify firms’ subjective risk perception using text analysis and machine learning techniques, and objectively measure their actual risk exposure from a supply-demand balance perspective (Bray & Mendelson, 2012; Wu, 2024).

Second, we theoretically integrate behavioral and operational risk perspectives, addressing the disconnect between cognition and action in the literature. Prior studies often examine risk perception through a psychology or behavioral economics lens, treating risk exposure as an issue of operational management, which results in fragmented theoretical insights (Ghadge et al., 2022; Jackson et al., 2024). By proposing a two-dimensional framework of cognition and response, we explain how firms can optimize risk control at both the perceptual and operational levels in the context of SCD. This contributes to extending the theoretical boundaries of risk perception and organizational information processing theories (Chatterjee et al., 2024; Mishra et al., 2024).

Third, unlike prior studies, we examine the micro-level mechanisms through which SCD influences supply chain risk by drawing on signaling theory and endogenous growth theory. We analyze how both information and technology channels affect firms’ risk outcomes (Drover et al., 2018; Kumar et al., 2021). In addition, we consider the heterogeneous effects of SCD on enhancing firms’ subjective risk perception and reducing their objective risk exposure. We specifically focus on the impact of industry monopoly, enterprise IC, and FC, which provides micro evidence for different enterprises to formulate differentiated risk management measures.

Managerial implicationsThis study offers several important practical insights for managers. First, in the face of increasing instability and complexity in global supply chains, relying solely on traditional reactive responses is no longer sufficient for effective risk management. Our findings suggest that SCD, through both informational and technological channels, provides firms with the tools necessary to integrate internal and external data, enhance risk prediction capabilities, and support dynamic adjustment. Managers should embed SCD within firms’ governance system by establishing end-to-end information systems, promoting interdepartmental and cross-functional coordination, and enabling real-time monitoring and adjustment of critical supply chain nodes. Firms should move beyond isolated emergency measures and instead elevate SCD to a strategic priority. For example, boards of directors could establish dedicated risk and digitalization committees to integrate digital risk management goals into long-term strategic planning and performance evaluation systems.

Second, many firms focus heavily on platform construction in their digitalization investments, but neglect to align institutional design with internal constraints. As a result, although information becomes accessible, it may not effectively support high-quality decision-making. Firms should thus restructure their data governance, internal audit, and process control systems to ensure orderly information flow and clearly defined accountability. Moreover, they should focus on building organizational resilience by optimizing their financial structure and resource allocation, thereby enhancing their capacity to respond to unexpected disruptions. Only when technological capabilities are embedded within a robust institutional foundation can digitalization serve as an effective tool for mitigating risk exposure in complex environments.

Finally, firms should adopt differentiated SCD and risk management strategies based on their industry structure, regional environments, and internal resource conditions. In highly monopolized industries, managers should place greater emphasis on the perception and monitoring of subjective risks to prevent risk events stemming from information opacity. In contrast, in highly competitive industries where demand is volatile, firms should prioritize the use of digital technologies to reduce actual risk exposure caused by supply-demand mismatches. Firms with strong FC should rationally plan digital investment, ensure that capital allocation considers risk prevention and control, and financial stability, and actively use government special subsidies, green credit, and other policy resources to alleviate financial pressure. For firms with ample financial resources, stronger strategic foresight is required. These firms should expand their digitalization strategies to include emerging technologies such as smart contracts and digital twins, further enhancing supply chain visibility and resilience.

Conclusion and limitationsThis study examines the impact of SCD on the supply chain risk faced by firms. The findings show that SCD enhances firms’ subjective risk perception and reduces actual risk exposure. After various robustness checks including the parallel trend, PSM, entropy balancing, changing risk measurement indicators, and placebo tests, this conclusion remains robust. The mechanism analysis reveals that SCD primarily enhances firms’ subjective risk perception and reduces actual risk exposure by improving information transparency and technological innovation capacity. Furthermore, heterogeneity analysis based on industry monopoly level, IC quality, and FC shows that low monopoly firms experience a significant increase in subjective risk perception during SCD, but the reduction in actual risk exposure is limited compared to that in high monopoly firms. High monopoly firms significantly reduce actual risk exposure through SCD, but the effect on subjective risk perception is not significant. Moreover, in firms with stronger IC and weaker FC, SCD can effectively address supply chain risks.

Finally, this study has several limitations that merit further exploration in future research. First, the analysis is based primarily on data from publicly listed companies in China. As such, the generalizability of the findings to other countries or regions remains uncertain. The effects of SCD on risk perception and risk exposure may vary under different institutional conditions. Thus, future studies could conduct cross-national or cross-industry comparisons to assess the external validity of the results of this research. Second, while this study focuses on the relationship between SCD and supply chain risk, it does not adequately address the role of digitalization within corporate governance. Due to data limitations, we were unable to investigate how digitalization may reshape the allocation of responsibilities within the board, particularly in the context of risk oversight. Therefore, future research could explore this issue from the perspective of governance structures and IC to uncover the broader organizational impact of SCD on firms’ risk management practices. Third, geopolitical factors were not included in the analytical framework. In reality, events such as trade tensions and regional conflicts have become critical sources of external shocks to supply chains. However, due to limitations in both the data and model design, we were unable to empirically assess these dynamics. Future research could thus integrate geopolitical risk with SCD to explore how firms leverage digital technologies to navigate increasingly complex global environments and to identify differentiated effects under different political regimes.

Compliance with ethical standardsThe authors declare that there are no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper. This study did not involve human participants or animals. The authors affirm that all aspects of this research were conducted with integrity and in accordance with the ethical standards expected in scholarly work.

CRediT authorship contribution statementHuiru Wei: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Kuiran Yuan: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation. Jie Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72563028) and the Western Project of the National Social Science Fund of China(24XMZ078). The usual disclaimer applies.

Present address: School of Economics and Management, Shihezi University. 221 Beisi Road, Shihezi City, Xinjiang 832,000, China

https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/risk-resilience-and-rebalancing-in-global-value-chains