Digital green technology convergence (DGTC) has emerged as a critical pathway for fostering high-quality productivity and promoting sustainable economic development. This study investigates the impact of DGTC on Chinese manufacturing firms’ total factor productivity (TFP) using a fixed-effects model with patent data from listed firms spanning 2003–2022. We determine that DGTC significantly enhances TFP, and this effect surpasses the combined impact of each technology independently. The effect is stronger for labour-intensive firms and regions with stronger intellectual property protection. Further investigation reveals that improved resource utilisation and management efficiency are mechanisms through which DGTC increased manufacturing firms’ TFP growth. These findings contribute to the academic understanding of DGTC in driving productivity while offering actionable insights for policymakers and industry leaders seeking to design strategies that balance innovation, competitiveness, and sustainability.

Digital technologies such as 5G, big data, cloud computing, artificial intelligence (AI), 3D printing, quantum computing, the internet and distributed ledgers have powerful capabilities for convergence and penetration. These technologies drive profound changes across industries, cities and micro-level fields, reshaping the global economy and society (Koga, 1998; Wang et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2023). The phenomenon of digital technology convergence was recognised as early as the late 1970s (Farber & Baran, 1977; Hacklin, 2008) and has accelerated significantly in recent years. Within the domain of digital technologies, notable examples of convergence include AI with high-performance computing (Huerta et al., 2020) and blockchain (Li et al., 2025; Pandl et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2022; Zuo, 2025), blockchain technology with digital twin technology (Somma et al., 2024) and communication technologies (Luo et al., 2025), big data with high-performance computing (Usman et al., 2018) and cloud computing with big data (Rahman & Rana, 2021) and network technologies (Cao et al., 2024; Duan et al., 2020; Han & Sohn, 2016; Song et al., 2022; Zhang, 2025). Beyond these, convergence has also been observed across multiple digital subfields (Fazel et al., 2024; Hariharan et al., 2020; Keith et al., 2024; Lim et al., 2018; Saidu et al., 2025). Furthermore, digital technologies exhibit robust cross-technology convergence potential (Hussain, 2021; Wang et al., 2024), influencing fields such as biotechnology (Elgabry & Johnson, 2024; Geum et al., 2012; Huang & Huang, 2015; Peters et al., 2021), medical technology (Fountzilas et al., 2025; Thirunavukarasu et al., 2023; Wang & Lee, 2023), accounting technology (Ibrahim et al., 2021), financial technology (Ayinde et al., 2024), nanotechnology(LEE & LIM, 2020; Tripathy et al., 2024; Yadavalli, 2025) and grid technologies(Adnan et al., 2024; Contzen, 2025). This ability to converge across diverse fields underscores the pivotal influence of digital technologies on fostering innovation and shaping the future of industries and societies.

The intersection of the digital technology revolution and escalating climate challenges has imposed unprecedented pressure on manufacturing firms (Tian et al., 2023). To remain competitive and comply with increasingly stringent environmental regulations, manufacturers must leverage digital technologies to enhance information processing and management efficiency and adopt green technologies to improve clean production capabilities and achieve emissions reduction goals. Consequently, Digital Green Technology Convergence (DGTC) has attracted growing attention, particularly within the manufacturing sector (Loeser et al., 2017; Ye et al., 2024; Yu & Zhang, 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). This trend is reflected in the rapid increase in innovations that combine (converge) digital and green capabilities. As illustrated in Figure 1, the number of DGTC-related patents filed by listed manufacturing firms surged from fewer than 100 in 2003 to over 22000 by 2022, underscoring the rapid and sustained growth of this technological trajectory. DGTC has become a vital strategy for sustaining manufacturers’ competitive advantage and long-term sustainable development (Yin & Yu, 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). Despite this growing momentum, empirical research on the effects of DGTC on manufacturing firms’ total factor productivity (TFP) remains limited. While recent studies have begun to examine this convergence (Hu et al., 2024; Li et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2025; Shan et al., 2025; Wang & Hou, 2024; Zhang et al., 2024), the extent of its impact on TFP remains insufficiently explored. This gap highlights the need for further empirical investigation to assess how DGTC can drive TFP improvement while advancing broader sustainability goals.

This study examines the impact of DGTC on manufacturing TFP using patent data from Chinese listed manufacturing firms between 2003 and 2022 to investigate how firms’ TFP evolves with the adoption of digital green technological innovations. At the outset, we pose the key question: does digital and green technology convergence deliver superior TFP outcomes compared with standalone adoption of either technology? To address this, we compare the effects of digital and green technologies individually and along with their combined influence. While previous research has explored digital technologies’ convergence in other domains, it remains unclear whether all digital technologies possess convergence potential or are equally effective. To delve deeper, we categorise digital technologies into four groups based on core industry digital standards, which enables us to evaluate the distinct productivity effects of each category when converged with green technologies.

Firms’ strategies are inherently connected to their development, which makes it challenging to establish a clear causal relationship between DGTC and firm TFP. This issue is crucial for determining whether this study can effectively examine how such convergence impacts TFP. To address this challenge, we implement the instrumental variable (IV) method and introduce external policy shocks and lagged core explanatory variables. To explore external policy shocks, we reviewed China’s existing policies on digital and green technologies and few policies directly reflect the convergence of these two fields. To overcome this limitation, we indirectly represent technology convergence policies employing a spatio-temporal overlay of relevant policies. Specifically, we analysed the characteristics of digital and green technologies and matched digital technology policies with green technology policies at temporal and spatial levels. This enabled us to construct a difference-in-differences model based on these policy overlaps to identify causal effects.

To strengthen the causal interpretation of our findings, we explore the mechanisms through which DGTC affects manufacturing TFP. Guided by resource-based and dynamic capability theories(Barney, 1991; Teece et al., 1997), we analyse the influence of resource allocation, utilisation and management efficiency in driving this impact. Since technological change influence labour dynamics (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019), we hypothesise that the TFP effects of DGTC could vary depending on a firm’s labour intensity. Moreover, the relationship between technological innovation and the external institutional environment, particularly intellectual property protection (IPP) (Lerner, 2009), has a critical influence on the productivity outcomes of digital green technology integration. To investigate these considerations, we conduct subgroup regression analyses based on firms’ labour intensity and the strength of regional IPP.

This study contributes to the extensive literature on the productivity paradox of digital technology. While digital technologies have demonstrated significant potential across various domains (Goldfarb & Tucker, 2019; Nambisan et al., 2017), overall TFP has fallen short of expectations, raising concerns about the productivity paradox (Acemoglu et al., 2014; Brynjolfsson et al., 2017; Goldfarb & Tucker, 2019; Karacuka et al., 2024). Scholars have debated this extensively, often emphasising the degree to which digital technologies integrate with other technological domains. For example, some attribute the paradox to delayed returns on digital investments (Brynjolfsson et al., 2021; Van Ark, 2016) or low digital tool utilisation rates (Nicoletti et al., 2020; Nucci et al., 2023; Sorbe et al., 2019). This implies that deeper digital technology convergence with other fields could produce higher productivity gains. While previous studies have largely focused on theoretical perspectives, the empirical evidence of this study establishes a direct link between theory and data. Specifically, we demonstrate the substantial productivity gains achieved through DGTC. Moreover, our findings reveal a heterogeneous impact of various types of DGTC in manufacturing firms, offering a novel explanation for the productivity paradox. Therefore, fostering and selecting appropriate DGTC may be a critical strategy for overcoming the productivity paradox, particularly in the manufacturing sector of the world’s largest developing economy.

This study aligns closely with previous research on DGTC. Several studies have examined its influence on economic performance. For example, Zhang et al. (2024) found that DGTC significantly increased firms’ asset contribution ratios and enhanced their competitiveness. Similarly, Wang and Hou (2024) quantitatively analysed the direct effect of DGTC on TFP using data from 30 Chinese provinces and revealed that DGTC significantly boosts regional TFP. Another stream of research has explored the environmental performance effects of DGTC. For example, Hu et al. (2024) demonstrated that DGTC can significantly reduce firms’ carbon emissions, and Shan et al. (2025) concluded that greater AI–green technology convergence efficiency lowers urban carbon emissions. However, the focus of our study differs by investigating the productivity implications of DGTC for manufacturing firms. Using a large, micro-level dataset of manufacturing firms, our research identifies and explores the transmission mechanisms through which DGTC influences TFP, providing fresh insights into the economic impacts of this convergence and extending the literature on manufacturing firms’ performance.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 develops the theoretical framework. Section 3 introduces the data and outlines the empirical strategy. Section 4 reports the main empirical results and conducts robustness checks. Section 5 provides additional analyses on potential mechanisms and heterogeneity. Section 6 discusses the findings in relation to the theoretical and empirical literature. Section 7 concludes the paper.

Theoretical analysis and research hypothesesDGTC and manufacturing firms’ TFPDigitalisation and green transformation present opportunities and challenges for traditional manufacturing firms. Although the benefits of digital and green transitions for socio-economic development are widely recognised and strongly supported by Chinese government policies, many businesses remain reluctant to embrace these changes. This reluctance often stems from the high costs, uncertainties and risks associated with green transformation and limited awareness of the potential synergies between digital and green initiatives (Ye et al., 2024). Digital and green transformations each rely on distinct sets of complex technologies. Digital transformation requires the adoption of digital tools and systems, while green transformation requires environmentally sustainable technologies. Because these technologies’ technical foundations and implementation requirements differ significantly, firms that only focus on one type can encounter barriers that make it difficult to adopt the other. Consequently, manufacturers may either pursue one path in isolation or avoid both altogether, unsure of how to integrate them or what benefits such convergence might yield. This study addresses that gap by exploring why DGTC is desirable and necessary and demonstrating how this convergence can significantly enhance firm performance. Specifically, we investigate the impact of DGTC on manufacturing TFP, offering practical insights for firms seeking to navigate this dual transformation.

Digital technologies offer significant advantages for manufacturing firms, particularly in production planning, energy management and pollution control. They can reduce emissions, improve resource efficiency and enhance both and environmental performance (Joshi & Gupta, 2019; Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2024). However, their environmental impact is not uniformly positive and overinvestment in digital technologies can undermine long-term environmental quality (Li, 2022). Ahmadova et al. (2021) argued that excessive digitisation raises electricity consumption, radioactivity, and e-waste. Moreover, not all digital tools contribute to sustainability. Technologies like additive manufacturing, industrial robots and autonomous mobile systems have been correlated with environmental performance decline (Chiarini, 2021). The extensive data required for digital operations, spanning storage, mining and analysis, also demands substantial energy input (Cohen, 2018). Therefore, while digitalisation can drive efficiency and growth, it can also introduce new sustainability challenges that manufacturers must address (Kiel et al., 2017).

Proactive green technology investment enables firms to reduce resource waste and emissions, improving environmental outcomes (Li & Li, 2023). Beyond environmental gains, such investments strengthen firms’ ability to integrate and reconfigure resources, enhance environmental awareness and boost product competitiveness (Qiu et al., 2020). These capabilities contribute to economic returns (Zhang et al., 2019) and enable firms to pursue environmental and financial goals in tandem (Jie & Zhu, 2021). For example, Aftab et al. (2022) determined that green technologies help modernise outdated processes, products and systems, improving environmental, social and economic performance. Similarly, Suki et al. (2023) demonstrated that green innovation enhances firms’ green intellectual capital and supply chain management, supporting long-term competitive advantages. However, despite these benefits, green technologies often fall short in areas such as information processing and data-driven production decision-making.

Amid intensifying environmental pressure, manufacturing firms must pursue strategies that simultaneously improve economic and environmental performance to enhance TFP. This will not only strengthen resource efficiency and pollution control to reduce costs but also cultivate the ability to process and integrate internal and external information for more effective resource management. Research indicates that a green strategic orientation can mitigate digital technologies’ negative environmental impacts (Loeser et al., 2017). Furthermore, digital tools can amplify the positive effects of green innovation on carbon performance (Zhao et al., 2024). Whether through digitised green practices or green-oriented digital initiatives, both pathways have been demonstrated to support improved economic and environmental outcomes (Ye et al., 2024). These findings indicate that DGTC has synergistic effects, offsetting the shortcomings of green technologies in areas such as information management and operational flexibility, while green technologies reduce the energy and environmental costs associated with digital applications. When converged, these technologies can enable firms to achieve cleaner, more adaptive and cost-effective production, ultimately raising productivity. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 Digital green technology convergence enhances manufacturing firms’ total factor productivity.

The resource-based view (RBV) argues that a firm’s competitive advantage arises from possessing valuable, rare and hard-to-imitate resources and capabilities (Barney, 1991). While firms cannot entirely avoid the disruptive effects of Schumpeterian shocks such as industrial restructuring, sustained technological innovation can enable them to maintain a strategic lead and reduce the threat of rapid imitation, which is akin to increasing their ‘escape velocity’ from intense competition. As the RBV has evolved, greater emphasis has been placed on dynamic capabilities, referring to a firm’s ability to adapt and reconfigure resources in response to changing environments (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2007). Similarly, resource orchestration theory contends that competitive advantage depends on the possession of heterogeneous resources as well as firms’ ability to deploy and manage them efficiently (Sirmon et al., 2011).

Within this framework, efficient resource utilisation and management are core drivers of sustained competitiveness and technological convergence aligns closely with these capabilities. Technological convergence, defined as the blending and overlapping of previously distinct technologies, has been shown to foster breakthrough innovations and accelerate technological discovery (Kodama, 1992; Nemet & Johnson, 2012; No & Park, 2010). As such, it is increasingly considered to be a key dynamic capability in innovation management (Hacklin, 2008), essential for developing long-term competitive advantages. Building on this theoretical foundation, this study adopts the RBV as an analytical lens to explore how DGTC influences TFP, with particular attention to resource utilisation and resource management efficiency improvements.

Resource utilisation efficiencyDGTC significantly enhances a firm’s capacity to acquire, allocate and consolidate resources, improving resource utilisation efficiency. According to the RBV, competitive advantage depends on access to valuable resources as well as the ability to deploy them effectively (Barney, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984). Technological convergence provides a powerful means of maximising resource value. By combining digital and green technologies, firms can increase transparency, precision and coordination in how resources are used. DGTC enables real-time resource consumption, energy use and emissions monitoring, reducing waste, minimising human error and facilitating dynamic resource allocation optimisation. For example, the convergence of quantum computing with energy-efficient technologies supports real-time power management in data centres, significantly lowering energy consumption. Similarly, converging digital systems with green design and material reuse technologies can improve recycling efficiency. DGTC also enhances the structural quality of resource use. Dynamic capabilities theory contends that firms can improve adaptability and resilience through continuous learning and resource reconfiguration (Teece et al., 1997). Firms often undertake upgrades to hardware and software infrastructure and restructure their workforces to fully leverage the benefits of green technologies (Acemoglu et al., 2023; Dranove et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2022). These changes typically increase the demand for highly skilled, interdisciplinary labour, particularly individuals with expertise spanning environmental science and information technology, while displacing lower-skilled positions. This structural shift contributes to improved resource utilisation and higher labour productivity. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 DGTC improves firms’ resource utilisation efficiency, promoting manufacturing firms’ TFP improvement.

DGTC substantially enhances firms’ capacity to acquire, analyse and integrate information related to production and operations, improving resource management efficiency. Strategic decision-making is central to business performance, directly influencing cost control and productivity, while managerial errors can lead to avoidable costs (Bloom & Van Reenen, 2010). Access to large-scale, diverse and real-time data is essential for accurate and timely decision-making (Brynjolfsson et al., 2011; Merendino et al., 2018). DGTC enables firms to collect real-time information on production processes, resource consumption and environmental performance, supporting resource allocation efficiency. For example, for inventory management, this convergence allows real-time tracking of market conditions and operational data, enabling firms to align inventory with demand, swiftly adjust production schedules and reduce waste. Similarly, combining digital tools such as big data analytics and AI with green technologies facilitates real-time energy use monitoring and intelligent operational optimisation, enhancing management efficiency (Chauhan et al., 2022; Tian et al., 2023). Furthermore, DGTC drives organisational optimisation by making structures more flexible and responsive. While green technologies advance sustainability by lowering pollution and emissions, digital technologies improve managerial agility through enhanced information flow, reduced communication costs and streamlined resource coordination across departments (Warner & Waeger, 2019). For example, the convergence of 5G with green energy scheduling platforms enables real-time cross-departmental information sharing, strengthening resource allocation responsiveness and accuracy. In addition, DGTC transforms traditional management systems. By embedding digital and green management principles, firms increasingly emphasise cross-functional collaboration, fostering innovative approaches to resource integration and management. Based on this analysis, we propose the final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 DGTC improves resource management efficiency, promoting manufacturing firms’ TFP improvement.

Our analysis uses panel data from Chinese A-share listed manufacturing firms spanning 2003–2022. The dataset is primarily sourced from the Cathay Pacific, China Stock Market & Accounting Research (CSMAR) database, which includes detailed firm-level data on patents, financials and other relevant fundamental information. The A-share market, predominantly including companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, is one of the largest equity markets in the world in terms of market capitalisation and trading volume. Listed companies are subject to strict disclosure and governance requirements set by the China Securities Regulatory Commission, ensuring high data reliability and comparability across firms. Due to its comprehensive coverage of publicly listed enterprises, A-share data have been extensively used in empirical studies examining corporate governance, innovation and productivity in China (Sun et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2025). The final dataset contains 25686 observations.

TFPWe adopt the Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) (LP) methodology to estimate TFP, which effectively addresses potential estimation bias. For robustness, we validate our findings using the Olley and Pakes (1996) (OP) approach. Specifically, we estimate TFP using the following model proposed by Lu and Lian (2012):

where Yit denotes firm i’s value added in year t, measured as the sum of depreciation of fixed assets, employee wages, employee benefit expenditure, taxes, surcharges and operating profits. K denotes capital input, measured as net fixed assets. L denotes labour input, which is measured by the number of employees. ρt, τj and ϑp respectively denote year, industry and province fixed effects (FEs). ε represents random disturbances and measurement errors.To address the significant missing data on listed companies’ investments, we use intermediate inputs (M) to proxy for observable TFP in our estimation, which are calculated as the difference between operating income and value added. To objectively capture the contribution of capital and labour to economic growth, we convert all nominal variables in the sample into real values, with 2003 as the base year. Nominal variables are adjusted using industrial producer ex-factory price indices categorised by region, industry and year, with deflators sourced from the CElnet Statistics Database. In addition, to account for potential discrepancies in industry classifications, we carefully standardise sub-industry classifications based on the National Economy Industry Classification and Codes (GB/4754-2017). This meticulous alignment ensures accurate and comprehensive sample matching with the corresponding price indices.

DGTCPatent classification analysis using International Patent Classification (IPC) codes is a well-established method for measuring technology convergence indicators, extensively validated in previous research (Curran & Leker, 2011; Gauch & Blind, 2015; Kim & Sohn, 2020; Song et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2023). Based on this methodological foundation, recent studies have specifically applied this approach to convergence indicators (Shan et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2024). Our research adopts a similar methodological approach to construct DGTC indicators.

We begin with listed companies’ patent data, employing a rigorous selection process. Design patents are excluded to focus solely on utility model and invention patents, ensuring the analysis captures high-value technological advancements. To identify IPC codes related to digital and green technologies, we use two authoritative documents, the Reference Relationship Table of Digital Economy Core Industry Classification1 and the Patent Classification System of Green Technologies2 (both 2023 editions), published by the State Intellectual Property Office of China (SIPO).

We employ a text analysis method to identify DGTC, classifying patents as digital–green patents if they contain IPC codes corresponding to both digital and green technologies. We aggregate the number of such patents at the firm–year level to construct a quantitative proxy for the degree of DGTC. We standardise the DGTC variable by dividing the number of digital–green patents by 100 to enhance the comparability between regression coefficients and standard errors. As a result, the estimated coefficient reflects the impact associated with every 100 digital–green patents. This transformation does not alter the substantive results of the analysis but improves the interpretability of significance levels and the clarity of the economic implications.

Control variablesDrawing on existing studies(Cui et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2023), we also control for firm-level characteristics in the analysis using data from the CSMAR database. The key variables include firm size (Size): logarithm of the number of employees, firm age (Age): logarithm of (listing year + 1), financial leverage (Lev): total liabilities divided by total assets, growth rate (Growth): annual revenue growth, current ratio (Liquidity): current assets divided by current liabilities, capital intensity (Kint): total assets divided by revenue, stock investment value (PER): current price divided by the ratio of net profit to paid-in capital, intangible asset ratio (Intang): net intangible assets divided by total assets, fixed asset ratio (Fixed): net fixed assets divided by total assets, book-to-market ratio (BMR): shareholders’ equity divided by market value, ownership type (Property): binary variable differentiating state-owned from non-state-owned enterprises, based on ultimate controlling shareholder and dual roles (ConPos): binary variable indicating whether the chairperson and CEO positions are held by the same individual.

Prior to regression analysis, we processed the initial sample by (1) retaining only manufacturing sector samples, (2) keeping samples with annual revenue of at least 5 million RMB, (3) excluding samples with eight or fewer employees, (4) removing outliers and samples with missing values and (5) applying a 1 % two-sided winsorisation to continuous variables. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for all variables.

Descriptive statistics.

We exploit a multiple FEs model for the empirical analysis to identify the impact of DGTC on firm TFP. The baseline empirical specification is as follows:

where i represents firm, t represents year, j denotes industry and r denotes city. TFPit denotes firm i’s TFP in year t. DGTCit is the key regressor of interest, representing firm i’s DGTC level. β is our main coefficient of interest, which captures the direction and magnitude of the relationship between DGTC and firm TFP. A negative sign for β indicates that DGTC is associated with reduced firm TFP, and a positive sign indicates the opposite effect. This interpretation enables us to evaluate the impact of DGTC on firms’ TFP performance.Controls represent a set of control variables that potentially influence firm TFP. To account for unobserved heterogeneity and time-varying effects, our model incorporates multiple FEs, encompassing firm FEs (σi) to control for time-invariant characteristics specific to each firm, time FEs (ρt) to capture common shocks or trends over time, industry FEs (τj) to account for variations across industries and city FEs (υc) to reflect local economic and regulatory conditions. The error term (εit) captures random disturbances. To ensure robust statistical inference, the model uses firm-level clustered standard errors, which address potential within-firm correlation of residuals over time. This approach provides reliable estimates of the relationship between DGTC and firm TFP.

Empirical resultsBaseline resultsTable 2 presents the baseline regression results, systematically examining the impact of DGTC on firm TFP. In Column (1), without controlling for any variables or FEs, DGTC is positive and statistically significant, initially indicating that DGTC positively influences TFP. Control variables are introduced in Column (2), and the coefficient remains strongly significant, implying that the positive effect is not driven by omitted firm-level heterogeneity. Columns (3)–(6) progressively incorporate firm-, year-, industry- and city-level FEs. Despite these increasingly stringent controls, the coefficient of DGTC remains stable and significant at the 1 % level across all model specifications. This consistent pattern reinforces the robustness of our baseline finding.

Effects of digital green technology convergence on TFP: baseline estimates.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

In Column (6), the coefficient of DGTC is 0.0325. As the DGTC variable is scaled (number of digital–green patents divided by 100), this coefficient implies that for every 100 additional digital–green technology patents, a firm’s TFP increases by approximately 0.31 % (0.0325 / 10.34), holding other factors constant. While the coefficient may appear numerically small, its statistical significance is high and the economic effect is meaningful in the context of aggregate TFP improvement over time.

These findings offer compelling empirical support for our theoretical expectations, demonstrating that DGTC substantially enhances manufacturing firms’ TFP. The significance of the results across multiple model specifications, including comprehensive FEs, confirms the robustness and generalisability of this relationship. Moreover, the rise in the adjusted R-squared (R²) from 0.04 in Column (1) to over 0.78 in Column (6) confirms the improved explanatory power of the models when firm-level and contextual characteristics are included. This indicates that DGTC operates alongside other firm and environmental factors in shaping productivity outcomes.

In summary, the baseline regression results provide strong and consistent evidence that DGTC is a significant driver of the manufacturing sector’s TFP improvement. These results justify further exploration of the underlying mechanisms and heterogeneity across different digital technologies and firm characteristics, which are addressed in subsequent sections.

Independent and convergence effects of digital and green technologiesDigital technologies enable manufacturing firms to make evidence-based production decisions, manage energy use more effectively and detect pollution, reducing emissions and enhancing resource reuse efficiency (Joshi & Gupta, 2019). These improvements drive enhanced economic performance (Huang et al., 2023) and environmental outcomes (Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2024). Similarly, proactive green technology investment and innovation strategies minimise resource waste and pollution, delivering environmental benefits (Li & Li, 2023) and enhance firms’ ability to integrate and reconfigure resources, improve environmental insights and boost product competitiveness (Qiu et al., 2020). These advancements generate economic returns (Zhang et al., 2019) and facilitate the synergistic achievement of environmental and economic goals (Jie & Zhu, 2021). While these findings may imply that digital and green technologies independently suffice to drive sustainable growth, they do not capture the full potential of technological convergence.

To comprehensively assess the impact of digital and DGTC, we analyse the independent and combined effects of these technologies on firm TFP. Table 3 presents the regression results for this analysis. Column (1) reveals that the coefficient for digital technology patents (Pat_Digtal) is 0.0113 and statistically significant at the 1 % level, indicating that digital innovation alone contributes positively to TFP. Column (2) shows that green technology patents (Pat_Green) also exert a significantly positive effect on TFP, with a coefficient of 0.0110. These findings confirm that both types of technological innovation independently enhance firm-level TFP. However, the most noteworthy insight emerges in Column (3), which only includes the digital–green convergence variable (DGTC), which captures patents that simultaneously meet digital and green criteria. The coefficient of DGTC is 0.0325, nearly three times the size of the individual effects observed in Columns (1) and (2). This demonstrates that the convergence of digital and green technologies generates substantial synergistic benefits, beyond their separate contributions.

Independent and convergence effects of digital and green technologies.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

The magnitude and statistical significance of the DGTCcoefficient support Hypothesis 1. Specifically, digital capabilities may enhance the effectiveness of green technologies in real-time monitoring, predictive optimisation and adaptive control, while green imperatives may shape digital applications towards more sustainable outcomes. Therefore, convergence fosters novel value creation mechanisms that are not present when each technology is implemented in isolation. Overall, these results provide robust empirical support for the transformative potential of DGTC. While previous studies have examined the isolated impact of digital or green innovation (Zhang et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2023), the productivity gains associated with their convergence remain underexplored. Our findings fill this gap by demonstrating that the DGTC not only reinforces individual benefits but also unlocks new synergistic pathways for TFP enhancement, offering valuable insights for firms seeking to maximise innovation returns and policymakers aiming to incentivise sustainable technological development.

Types of DGTCThe enabling effect of DGTC varies significantly across different types of digital technologies. To examine this heterogeneity, we classify digital technologies into digital product manufacturing, digital product services, digital technology c the Core Industry Classification of the Digital Economy and IPC Reference Relationship Table (2023). By matching the IPC codes of digital technologies in each category with those of green technologies, we construct four convergence indices, which are expressed as DigProManGreen, DigProSerGreen, DigTecAppGreen and DigFacDriGreen.

Table 4 presents the regression results examining the impact of each DGTC type on manufacturing firms’ TFP. In Column (1), the coefficient of DigProManGreen is 0.0350, which is statistically significant at the 1 % level, indicating that convergence between digital product manufacturing technologies (e.g., computers, sensors and communication hardware) and green technologies enhances firms’ TFP. Similarly, Column (2) reveals a significantly large coefficient for DigProSerGreen, also at the 1 % level, indicating that digital services such as cloud computing, data analytics and software platforms are highly effective in boosting TFP when integrated with green technologies.

Effect of digital green technology convergence on total factor productivity by digital technology type.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

By contrast, Columns (3) and (4) present results for the other two DGTC categories. DigTecAppGreen, representing digital technology applications such as internet and communication services, yields a positive but statistically insignificant coefficient. Similarly, DigFacDriGreen, which reflects digital factor-driven technologies such as e-commerce and online finance is insignificant. These findings indicate that convergence of virtual economy–oriented digital technologies can not translate into measurable TFP gains for manufacturing enterprises.

The underlying mechanisms may lie in the nature of technological support each category provides to the real economy. Digital product manufacturing and service industries offer tangible infrastructure and technical capabilities that align more directly with manufacturing firms’ production needs. For example, hardware systems can enhance automation and software platforms can optimise resource allocation and monitor emissions in real time. These features make their convergence with green technologies more actionable and impactful. Conversely, digital technology applications and digital factor-driven technologies tend to serve broader market or consumer-facing functions and are less directly embedded in physical production process, limiting their synergy with green technologies. Overall, the regression results demonstrate that not all digital technologies contribute equally to TP when converged with green innovations. The digital technologies that are most embedded in the real economy, particularly those for hardware production and software services, exhibit the strongest economic effects when integrated with environmental technologies. These insights deepen our understanding of the conditions under which DGTC can most effectively drive sustainable industrial transformation.

Robustness testsEndogeneityWhile this study focuses on the impact of DGTC on firms’ TFP, a potential endogeneity problem stemming from reverse causality remains, as firms with higher TFP may be more inclined to adopt DGTC practices. We employ the IV method, external policy shocks and lagged core explanatory variables to address endogeneity concerns.

(1) Instrumental variable approach

Although technology convergence quantitative impact on firm development has been widely explored in the existing literature (Chen et al., 2023; Gao et al., 2024; Giachetti & Dagnino, 2017; Kim et al., 2019; Lee, 2023; Pan et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023; Huang & Gao, 2023), the issue of endogeneity poses a significant challenge in this area of research. Converging multiple technological fields makes it particularly difficult to identify appropriate IVs. The shift–share IV (SSIV) method offers a promising solution to this problem (Borusyak et al., 2022). Referencing Li et al. (2022) and Xu et al. (2024), we adopt the SSIV method to construct an IV for DGTC as follows. (1) Calculate the annual growth rate of the mean value of DGTC across all firms as the overall growth rate (Shift). (2) For each firm, compute the mean value of DGTC among other firms in the same industry from the previous year as the initial industry-level share (Share). (3) Use theShift×Share interaction term as the DGTC simulated incremental value of each firm for each year. (5) Following Lewbel (1997), calculate the third power of the deviation between the firm’s actual DGTC level and its simulated incremental value as the IV.

We re-estimate the model using two-stage least squares (2SLS), presenting the results in Table 5. The first-stage results in Column (1) reveal that the IV is strongly correlated with DGTC, at a 1 % significance level, satisfying the relevance condition. In the second-stage regression in Column (2), the coefficient on DGTC remains positive and significant (0.0179, p < 0.01), consistent with our benchmark estimates. The Kleibergen–Paap F-statistic of 54.088 exceeds the critical value of 10, ruling out weak IV bias. These results confirm that DGTC has a robust and significantly positive effect on firm TFP, after accounting for potential endogeneity.

(2) External policy shocks

Digital green technology convergence and total factor endogeneity.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

We further address endogeneity using external policy shocks to proxy for DGTC. While direct policies targeting DGTC are uncommon, numerous policies have independently promoted digitalisation or green initiatives. Theoretically, if these policies overlap across time and regions, they can generate combined external effects that reflect the characteristics of digital and green policies.

Therefore, we screen for digital and green policies that coincide temporally and geographically. We demonstrate that the National Big Data Comprehensive Pilot Zone policy (BigData) and the Low-Carbon City Pilot Policy (LowCarbon) overlap in specific years and regions. As these two policies have significantly impacted digital and green technology adoption (Xu & Cui, 2020; Zhang et al., 2024), their overlap could be an external shock to DGTC. Therefore, we construct a policy shock variable (Policy_DGTC), assigning a value of 1 to observations exposed to both policies at the city and year level and 0 otherwise. The regression results in Column (3) of Table 5 reveal that the coefficient of the policy shock variable is significantly positive. Notably, the individual effects of each policy (BigData, LowCarbon) are statistically insignificant, emphasising that their joint implementation (a proxy for DGTC) drives TFP improvement. This quasi-natural experiment provides additional causal evidence supporting our baseline findings.

This method introduces a new approach for measuring external policy shocks to technology convergence, enriching the empirical methodology in this field. While this approach can theoretically be extended to other areas of technology convergence, the complexity of policy selection increases exponentially with the number of technological fields considered. Consequently, its applicability across multiple domains of technology convergence may be limited, necessitating further methodological advancements.

(3) Lagged DGTC

To further mitigate endogeneity concerns, we lag DGTC by one and two periods and re-estimate the baseline model. Results in Columns (4) and (5) of Table 5 reveal that the coefficients for the lagged variables remain significantly positive. These findings mitigate reverse causality concerns and confirm that the productivity gains from DGTC are not immediate but persist over time.

In summary, the results of all three robustness tests support a consistent conclusion that DGTC has a positive, causal impact on firm TFP. The coefficients’ strength and stability across different identification strategies reinforces the validity of our findings and provide compelling empirical support for promoting the DGTC in manufacturing.

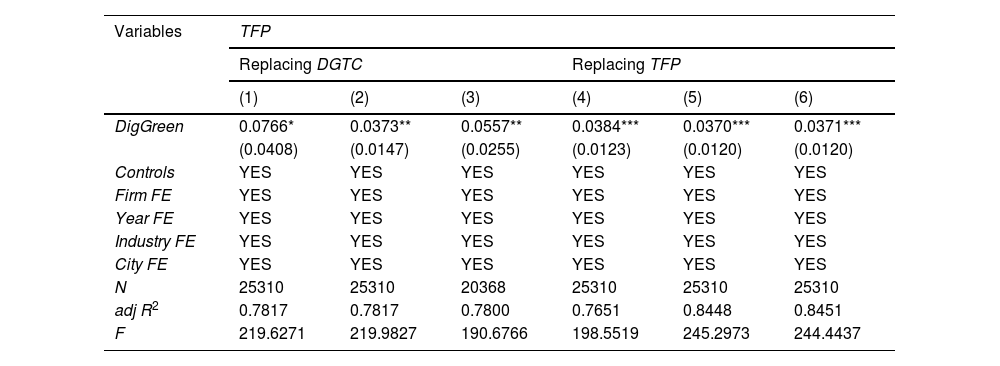

Alternative measuresTo further ensure the robustness of our baseline findings, we adopt a series of alternative measurements for the DGTC and firm-level TFP indicators. These robustness tests confirm that our baseline conclusions are not sensitive to the specific definitions or calculation methods used.

- (1)

Alternative DGTC measures

We construct three alternative DGTC indicators to verify that our results hold under different convergence identification strategies. First, we refine IPC code classification. The IPC codes in the Green Technology Patent Classification System (2023) are categorised into ‘fully’ and ‘partially involved’. Partially involved codes include non-exclusive green technologies, which can overestimate green patents. To address this, we only use fully involved IPC codes to re-measure the DGTC index. Second, we focus on invention patents. While utility model and invention patents reflect technological progress, invention patents have higher technological content and better represent technological advancements retain only invention patent data for identifying DGTC. Third, we separate granted patents from patent applications. Patent applications only reflect the degree of importance enterprises attach to technology, whereas granted patents represent actual technological advancements. Thus, we use only the data of patents granted after application to re-identify DGTC.3 Regression results based on these three redefined DGTC indicators in Columns (1)–(3) of Table 6 all yield significantly positive coefficients, consistent with our benchmark findings. This demonstrates that our conclusion that DGTC promotes firm TFP remains robust to alternative definitions of DGTC.

Table 6.Robustness tests: alternative digital green technology convergence and total factor productivity measures.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

- (2)

Alternative TFP measures

We introduce two alternative TFP measures. To address potential bias in our TFP calculation, we use the OP method to re-measure TFP. The regression results in Column (4) of Table 6 are consistent with our main results based on the LP method. Furthermore, controlling for time, industry and province FEs in the baseline model may lead to over- or underestimation of TFP. To address this, we remove all FEs and re-measure TFP using LP and OP methods. As shown in Columns (5) and (6) of Table 6, the coefficients on DGTC remain significantly positive and are similar to the baseline. These results confirm that our conclusions are not driven by specific modelling choices regarding TFP estimation. DGTC consistently demonstrates a positive impact on firm TFP after relaxing control variables and applying alternative estimation methods.

Regardless of whether we redefine DGTC using more restrictive patent categories or recalculate TFP using alternative methodologies, the results remain consistent and statistically significant across all specifications. These findings further reinforce the validity and robustness of our baseline conclusion, validating that DGTC has a significantly positive influence on enhancing manufacturing enterprises’ TFP.

Changing fixed effect dimensions and clustering levelsTo further reinforce the robustness of our baseline findings, we explore the sensitivity of the results to alternative model specification, particularly FE dimensions and the levels at which standard errors are clustered.

- (1)

Changing fixed effect dimensions

One potential concern in firm-level panel regressions is omitted variable bias arising from unobserved heterogeneity across multiple dimensions. To mitigate this, we augment the baseline model with interactive FEs that account for higher-dimensional heterogeneity covering year–industry, year–city and industry–city FEs. Columns (1)–(3) of Table 7 reveal that the coefficient of the DGTC variable remains significantly positive across all three models. This consistency indicates that the positive impact of DGTC on TFP is not driven by unobserved shocks specific to industries, cities or their combinations.

Table 7.Robustness tests: changing fixed effect dimensions and clustering levels.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

- (2)

Changing clustering levels

Another crucial robustness test involves the standard error clustering level choice. While our baseline model clusters errors at the firm level, which is standard in panel data settings, to ensure that our inference is not biased by intra-group correlation at alternative levels, we re-estimate the baseline model using firm–year, industry and city-level clustering strategies. Columns (4)–(6) of Table 7 show that the coefficients for DGTC remain significantly positive across all clustering schemes. Although the standard errors vary slightly across clustering levels, the sign and significance of the DGTC coefficient are stable.

The regression results remain consistent and robust after adjusting for different FE dimensions and clustering levels, further confirming the validity of the benchmark findings.

Further analyses: mechanisms and heterogeneityPotential mechanismsWe next investigate the key channels through which DGTC drives manufacturing firms’ TFP. By synergising the strengths of digital and green technologies, DGTC promotes resource efficiency and improves TFP. This study posits that DGTC enhances enterprise TFP through two primary mechanisms of optimising resource utilisation and management efficiency.

Resource utilisation efficiencyThe preceding theoretical analysis posits that DGTC enhances resource utilisation efficiency, which is reflected in adaptive resource structure adjustment and increased output per unit of resource input. To empirically test this mechanism, we specifically examine two key dimensions of labour force structure and labour resource allocation efficiency.

To quantify labour resource structure, we reference Autor et al. (2003), categorising employees into eight occupational groups encompassing management, technical, financial, marketing, production, administrative, auxiliary and other employees. As managerial, technical and financial roles are generally associated with higher skills, we define employees in these categories as high-skilled, and those in other roles are classified as low-skilled. We construct the two measures using the logarithm of the number of high-skilled employees plus one for high-skilled labour (HighEdu), and the ratio of high-skilled employees to total employees to reflect the labour resource structure (EduStruct).Columns (1) and (2) of Table 8 reveal that DGTC has a positive and statistically significant impact on both indicators, indicating that DGTC encourages firms to upgrade their workforce structure by increasing the absolute number and proportion of high-skilled employees. These findings support the perspective that DGTC drives skill upgrading in manufacturing firms.

Potential mechanism: resource utilisation efficiency.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

We reference established research (Bai et al., 2006; Liao et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2023) to quantify labour resource allocation efficiency using a proxy for the firm’s over-employment rate, which indicates labour redundancy (ExEmp). In addition, we calculate labour productivity as the natural logarithm of the ratio of operating revenue to the number of employees to assess labour allocation efficiency (LabourProd). Columns (3) and (4) of Table 8 reveal that DGTC is correlated with a significant reduction in over-employment and a significant increase in labour productivity. This indicates that DGTC helps reduce labour mismatch, enhances resource allocation efficiency and strengthens labour inputs’ output-generating capacity, validating Hypothesis 2.

Our results demonstrate the impact of emerging technologies on resource allocation structure and efficiency, with a particular focus on labour resources, which is a topic of central concern in economic and societal discourse. The findings demonstrate that DGTC increases high-skilled labour demand and promotes labour force structure upgrading. This aligns with contemporary perspectives on technology-driven transformation in the labour market. For example, using a dataset on industrial robot adoption and employment in Japan, Adachi et al. (2024) demonstrated that a higher density of industrial robot use is correlated with increased demand for highly educated and skilled workers. Furthermore, our analysis confirms the positive effect of DGTC on labour resource allocation efficiency, contributing to the broader understanding of how technological change reshapes labour structure and drives productivity growth (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019).

Resource management efficiencyOur theoretical analysis indicates that DGTC can improve resource management efficiency, which is manifested in improved efficiency in management decision-making and implementation such as resource acquisition, allocation, scheduling and recycling. To systematically measure resource management efficiency, we focus on four key indicators of inventory management efficiency, management costs, selling costs and transaction costs.

- (1)

Inventory management efficiency (DSI): We use inventory turnover days as a proxy variable, which is calculated as the ratio of days in a given period to the inventory turnover ratio. The inventory turnover ratio is defined as the ratio of operating costs to the final inventory balance. Fewer inventory turnover days indicate higher inventory management efficiency. Column (1) of Table 9 shows that DGTC significantly reduces inventory turnover days, improving firms’ inventory control, likely by enabling more accurate demand forecasting and real-time supply chain coordination through digital tools.

Table 9.Potential mechanism: resource management efficiency.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 % 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

- (2)

Management costs (ManCost): This factor reflects management efficiency (Huang et al., 2023), which we measure using the ratio of management costs to total assets. A lower ratio indicates more efficient managerial operations. Column (2) of Table 9 indicates that DGTC is correlated with a statistically significant reduction in management cost ratios, indicating that DGTC reduces administrative burdens and enhances managerial decision-making through improved information processing and automation.

- (3)

Selling costs (SelCost): Selling costs are the expenses incurred during product sales and reflect the firm’s production decision-making efficiency. We calculate this as the ratio of selling costs to total assets. Column (3) of Table 9 demonstrates that DGTC significantly reduces this ratio, highlighting its influence on streamlining market-facing activities such as consumer analytics, digital marketing and logistics, reducing the cost of reaching end users.

- (4)

Transaction costs (TranCost): This factor refers to expenses related to information dissemination, negotiation, advertising, transportation and contracting, which reflect internal management efficiency and external market interactions (Williamson, 1981). We use the ratio of the sum of sales, management and financial costs to total assets to quantify transaction costs. Column (4) of Table 9 reveals a significant reduction in transaction costs under DGTC, confirming its capability to facilitate more efficient information flow and reduce friction across firm boundaries.

The evidence presented in Table 9 validates Hypothesis 3. DGTC enhances the precision and speed of internal processes, reducing various operational costs. These improvements ultimately translate into higher TFP for manufacturing firms.

In summary, our analysis reveals that (1) DGTC enhances manufacturing firms’ TFP by improving resource utilisation efficiency through optimised labour resource structures, reduced over-employment and increased labour productivity and (2) improves resource management efficiency by enabling precision decision-making, reducing inventory turnover days and lowering management, selling and transaction costs, which fosters overall operational efficiency. Our findings demonstrate the influence of DGTC on enterprise management, confirming its positive effect on resource management efficiency. In recent years, growing scholarly attention has focused on the relationship between technology and organisational management, which is closely associated with the rapid development of digital technologies such as big data analytics (Brynjolfsson et al., 2011; Uršič & Čater, 2025). Previous research has also demonstrated the critical influence of digital technologies on reducing administrative costs and improving managerial efficiency (Guo et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023). Building on this foundation, we introduce the concept of green management and specifically focus on segmented resource management scenarios. In doing so, we contribute to the growing literature on the managerial implications of digital technologies and their convergence with other technological domains.

Heterogeneity analysisLabour intensityThe analysis in subsection 5.1.1 demonstrates that DGTC increases the demand for high-end, digitally skilled talent while reducing the proportion of low-skilled labour. This transformation optimises the occupational workforce structure and enhances manufacturing firms’ production efficiency. Therefore, we expect labour-intensive enterprises, which rely heavily on low-skilled labour, to experience a more pronounced labour-saving effect from DGTC, increasing productivity gains.

To test this assumption, we measure labour intensity using the ratio of total employees to total assets and divide the sample into labour-intensive and non-labour-intensive groups using the median of this ratio. Regression results in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 10 indicate that the coefficient of DGTC is positive and statistically significant in labour-intensive firms (Column (2)) but insignificant in non-labour-intensive firms (Column (1)). Specifically, DGTC improves TFP by 0.0579 in labour-intensive firms, indicating a stronger productivity-enhancing effect where labour-saving transformations are most needed. This evidence supports our theoretical prediction that DGTC complements labour-intensive firms’ production structure more effectively by replacing routine, low-skill tasks with digital solutions and process innovations.

Heterogeneous effects of digital green technology convergence on total factor productivity.

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance at 10 %, 5 % and 1 % levels, respectively. Standard errors clustered at the firm level are in parentheses.

IPP is a crucial external factor motivating firms to engage in research, development and innovation activities. Strong IPP regimes encourage firms to invest in innovation and facilitate the effective digital and green technology utilisation. We expect DGTC to be higher in regions with robust IPP, resulting in a more significant contribution to manufacturing firms’ TFP.

To examine this assumption, we use each province’s IPP index, obtained from the National Evaluation Report on Intellectual Property Development published by the SIPO, dividing the sample into high-IPP and low-IPP groups, based on the median value of the index. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 10 present the corresponding regression results.

The findings reveal that the coefficient of DGTC is only positive and significant in high-IPP regions (Column (4)) and is statistically insignificant in regions with weak IPP (Column (3)). This indicates that a strong IPP environment enhances TFP gains from DGTC adoption by reducing risks of imitation, incentivising innovation and ensuring firms can reap returns from digital–green investments. These results are consistent with previous research highlighting the complementary relationship between institutional quality and technology-driven productivity(Agostino et al., 2020; Younas, 2025).

DiscussionIn recent years, digital technologies have triggered a new wave of economic transformation, attracting increasing attention to their convergence with technologies from other fields (Fountzilas et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024). Existing research has indicated a possible slowdown in productivity growth in the digital economy era, with one explanation being digital technologies’ limited diffusion and convergence capacity (Nicoletti et al., 2020). At the same time, the global community has emphasised the need to address environmental pollution and the challenges of unsustainable development. In this milieu, promoting the coordinated development of digitalisation and green transformation has become a critical strategic direction for countries (Ye et al., 2024). At the micro-economic level, manufacturing enterprises must determine how to integrate digital and green technologies. However, the industrial sector has often underestimated the importance of DGTC and academic studies have rarely provided direct evidence of its impact on firm performance.

Our empirical analysis provides robust support for the theoretical prediction that DGTC enhances manufacturing firms’ TFP by amplifying innovation and improving operational efficiency. These findings align with previous studies on digital transformation that have highlighted the influence of digital tools in enhancing managerial efficiency (Brynjolfsson et al., 2011; Uršič & Čater, 2025). Notably, our results extend the literature by demonstrating that DGTC produces greater productivity gains than independently adopting these technologies. While previous research has largely treated digitalisation and green innovation as separate drivers (Zhang et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2023), our evidence confirms that complementarity between the two domains is a critical source of competitive advantage.

The mechanisms of improved labour allocation, reduced over-employment, enhanced labour productivity and lower transaction and coordination costs are consistent with resource-based and organisational capability theories, emphasising the synergistic effects of complementary resources. We also identify heterogeneous effects, showing that labour-intensive firms and firms in high-IPP regions experience more pronounced benefits. These findings are consistent with innovation diffusion and institutional economics perspectives, indicating that the effectiveness of technology convergence depends on firm-level capabilities and the external environment. Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of research on sustainable industrial transformation by integrating the concept of DGTC into TFP analysis.

ConclusionThis study examines the impact of DGTC on firm TFP using a panel dataset of Chinese A-share listed manufacturing companies from 2003 to 2022. By integrating patent-based innovation data with detailed firm-level financials, we provide novel empirical evidence on the magnitude and mechanisms of the DGTC effect. Our analysis demonstrates that DGTC significantly outperforms the separate adoption of digital and green technologies in enhancing TFP. The primary drivers of this effect are improved labour skills, optimised workforce composition, reduced operational redundancy and enhanced resource allocation and management efficiency. Theoretically, our findings extend the literature on digital transformation and environmental innovation by demonstrating that complementarity, rather than substitution, enhances the relationship between these two technological domains. We empirically validate for the proposition that digital technologies can act as enablers of green innovations and vice versa, resulting in superior performance outcomes, enriching ongoing debates on the productivity implications of the digital economy and the green transition.

From a practical perspective, our results indicate that manufacturing firms should strategically prioritise DGTC as an integral aspect of their long-term competitiveness agenda. Combining advanced digital tools with environmentally sustainable practices can generate simultaneous economic and ecological benefits such as reducing production costs, lowering carbon emissions and improving operational resilience. Firms can leverage AI, big data analytics and the Internet of Things to monitor energy consumption in real time, optimise production scheduling and enhance supply chain transparency to achieve superior environmental performance while also boosting profitability. Managers should also recognise the critical influence of human capital and organisational culture on advancing the benefits of DGTC. Investments in workforce upskilling, interdisciplinary training and fostering a culture that values innovation and sustainability are essential for maximising convergence-related returns. Moreover, integrating DGTC into corporate governance and performance evaluation systems can align organisational incentives with long-term sustainability goals. Firms that successfully combine digital and green initiatives are also likely to improve their reputations among stakeholders, attract environmentally conscious investors and gain early-mover advantages in emerging green markets.

For policymakers, our findings underscore the importance of designing integrated policy frameworks that simultaneously promote digitalisation and green transformation rather than treating them as isolated agendas. This could involve coordinated tax incentives and targeted research and development subsidies that encourage firms to invest in convergence-related projects. Policymakers should also consider establishing digital–green demonstration zones and industry clusters, where firms can share technological resources and best practices. Development of digital–green infrastructure such as smart energy grids and carbon tracking platforms is particularly critical for enabling convergence, particularly in less-developed regions where resource constraints are more severe. Furthermore, strengthening IPP frameworks and harmonising standards for digital and environmental technologies will provide firms with the guidance and confidence to invest in innovation without fear of imitation or regulatory uncertainty. Finally, fostering cross-sector collaborations between technology providers, manufacturing firms, universities and research institutions can accelerate convergence technologies’ diffusion and create innovation ecosystems that amplify economic and environmental benefits at a national level.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the focus on listed firms means that the results may not fully capture the experience of smaller or less financially constrained enterprises. Listed firms often have stronger financial resources, better technological capabilities and greater access to external financing, which can amplify the positive effects of DGTC. Second, our analysis does not incorporate the long-term dynamic effects of DGTC or potential diminishing returns as adoption deepens. Questions such as whether convergence effects accumulate gradually, weaken over time or exhibit path dependence remain unexplored. Third, the study is limited to a single-country context and institutional, regulatory or industrial differences across countries may produce divergent convergence outcomes. Future research could address these limitations by incorporating broader and more diverse firm samples, exploring dynamic adjustment processes and conducting cross-country comparative analyses. Such extensions would enrich our understanding of how DGTC evolves under different organisational and institutional conditions and whether it consistently generates sustainable productivity gains. As digital and green technologies continue to progress, examining these contingencies is crucial for developing more effective industrial and policy strategies that align competitiveness with sustainability objectives.

CRediT authorship contribution statementZan Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Qian Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization.

The classification codes and naming conventions for the core digital economy industries in this document adhere to the Statistical Classification of the Digital Economy and Its Core Industries (2021). These core industries include all economic activities that deliver digital technologies, products, services, infrastructure and solutions to support industries’ digital transformation. Additionally, the codes include activities entirely dependent on digital technologies and data as key elements. To provide clarity, we categorised these industries are into four major groups. 01 Digital Product Manufacturing Industry encompasses computer manufacturing, communication and radar equipment manufacturing, digital media equipment manufacturing, intelligent equipment manufacturing, electronic components and equipment manufacturing and other digital product manufacturing. 02 Digital Product Service Industry includes a digital product maintenance subcategory. 03 Digital Technology Application Industry includes software development; telecommunication, broadcasting, television and satellite transmission services; internet-related services; information technology services; and other digital technology application industries. 04 Digital Factor-Driven Industry includes internet platforms, information infrastructure construction and other digital factor-driven industries.

The classification system employs international patent classification to identify green technology, drawing on the World Intellectual Property Organization green technology list to enable comparability of the international classification system to support the construction and statistical analysis of the global green technology patent database and the international exchange and transfer of green technology patents.