This study investigates how entrepreneurial orientation (EO) influences firm performance, focusing on both environmental and financial performance. Drawing on the resource-based view (RBV) and knowledge-based view (KBV), the study develops an integrative framework in which green product and process innovations mediate the EO–performance relationship, while tacit knowledge functions as a boundary condition that strengthens the effects of EO on green product and process innovations. Using survey and objective data from 244 firms in the Spanish textile industry, this study employs partial least squares structural equation modeling and a moderated mediation approach to test the proposed relationships. The findings suggest that green product innovation contributes similarly to environmental and financial performance, whereas green process innovation has a stronger effect on environmental performance. Moreover, tacit knowledge amplifies the impact of EO on green innovation—particularly green product innovation—by facilitating the effective use of internal knowledge resources to achieve sustainability-driven competitiveness. Overall, the study advances the understanding of how EO fosters innovation and performance within the combined frameworks of RBV and KBV, offering theoretical and practical insights for firms aiming to enhance environmental and financial performance by combining EO with knowledge-driven innovation.

As firms face increasing pressure to reconcile competitiveness with environmental sustainability, entrepreneurial orientation (EO) has become a central strategic posture through which firms respond to these challenges by fostering innovation, proactiveness, and risk-taking (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Rauch et al., 2009; Wales et al., 2021). EO reflects how firms recognize and exploit opportunities, enabling them to adapt under uncertainty, while channeling entrepreneurial behavior toward sustainability-driven competitive advantage (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003).

Although EO has been widely examined as a driver of firm performance, the empirical evidence remains inconsistent. Whereas many studies report positive effects in certain contexts (Rauch et al., 2009; Suder et al., 2025a; 2025b; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005), others find weak or even nonsignificant relationships, suggesting that EO does not automatically translate into superior performance but depends on intervening mechanisms and contextual conditions (Hughes et al., 2018; Sahi et al., 2024). This inconsistency has led to calls for identifying the pathways and contingencies through which EO creates value (Wales et al., 2021). Nonetheless, most studies have focused on organizational, market, or strategic mechanisms (Sahi et al., 2024; Suder et al., 2025a; 2025b), whereas sustainability-oriented pathways remain relatively underexplored. Some exceptions include research on sustainable practices (Courrent et al., 2018), proactive environmental strategy (Menguc et al., 2010), or EO’s role in enabling sustainability through smart manufacturing readiness (Gumbi & Twinomurinzi, 2025). However, these studies offer an initial but incomplete understanding of sustainability-oriented mechanisms, highlighting opportunities for further investigation.

In particular, limited attention has been paid to the environmental dimension of firm performance, despite its growing relevance in explaining how EO contributes to sustainable competitiveness. Although the links between EO and financial, market, or international performance are well established (Sahi et al., 2024; Suder et al., 2025a; 2025b), research examining how and when EO drives environmental performance is still in its early stages (Dias et al., 2021; Dickel, 2018). Some recent studies have begun to examine this connection (e.g., Chavez et al., 2020), but much remains to be understood about the mechanisms and boundary conditions that shape it.

In this context, the increasing adoption of green innovation as a means to achieve sustainable competitive advantage underscores the need to clarify its role within the EO–performance relationship. Green innovation—whether in products or processes—enables firms to reduce resource consumption, improve efficiency, and respond to rising expectations for environmentally responsible solutions (Chen et al., 2006; Huang & Li, 2017). Recent research has explored green innovation as a mediator in various areas of environmental management (Tian et al., 2023), but most studies linking EO and innovation have focused on general innovation rather than its environmental dimension (Al Mamun et al., 2022). Distinguishing between green product and green process innovation is therefore crucial (Cassânego et al., 2025), as evidence suggests that they may differentially affect environmental and financial performance (Hall & Wagner, 2012). Examining these innovation types as distinct mediators offers a more nuanced understanding of how EO contributes simultaneously to competitiveness and sustainability.

From a knowledge-based view (KBV), knowledge is the most critical resource explaining firm heterogeneity and competitive advantage (Felin & Hesterly, 2007). It plays a key role in opportunity recognition and exploitation (Bojica & Fuentes, 2012) and is a fundamental driver of innovation and superior performance (Operti & Carnabuci, 2014). Recent studies reaffirm that knowledge processes are vital for innovation and subsequent performance (Cristache et al., 2025; Dzenopoljac et al., 2025). Although explicit knowledge can be codified and transferred at low cost, tacit knowledge—rooted in experience, routines, and intuition—is firm-specific, difficult to imitate, and thus more likely to generate sustained advantages (Dzenopoljac et al., 2025; Maravilhas & Martins, 2019; Wang et al., 2022). In the EO context, tacit knowledge enhances firms’ ability to channel entrepreneurial behavior into environmentally sustainable innovation by improving problem-solving, decision-making, and the integration of environmental principles into products and processes (Grant, 1996; Wu et al., 2023; Wuytens et al., 2024). Despite its relevance, the moderating role of tacit knowledge in the EO–green innovation nexus remains underexplored, representing a critical research gap (Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020).

Building on these insights, this study integrates the resource-based view (RBV) and the KBV to provide a comprehensive understanding of how and when EO contributes to environmentally sustainable outcomes. The RBV highlights green product and process innovation as strategic resources through which EO can be transformed into superior environmental and financial performance. The KBV complements this by emphasizing tacit, experience-based knowledge as a key contingency shaping the effectiveness of these innovations. By combining these perspectives, the study advances EO research by embedding environmentally-oriented mechanisms and knowledge-based contingencies into a unified framework. This offers a more comprehensive understanding of how entrepreneurial firms convert their strategic orientation into sustainable competitive advantage.

Theoretical framework and hypothesisLiterature reviewResearch on EO has long highlighted its relevance as a strategic posture that enables firms to identify and exploit opportunities under uncertainty (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Rauch et al., 2009). Nevertheless, despite extensive empirical attention, findings on the EO–performance relationship remain inconclusive. Whereas several studies report positive effects, others reveal weak or nonsignificant results, indicating that EO’s influence is context-dependent and shaped by intervening mechanisms and boundary conditions (Hughes et al., 2018; Rauch et al., 2009; Suder et al., 2025a). This inconsistency has shifted scholarly focus toward understanding the processes—both mediating and moderating—that explain how and under what conditions EO translates into superior performance (Wales et al., 2021).

Two main research streams have emerged from this debate. The first centers on sustainability-oriented mechanisms, emphasizing that EO can enhance performance by driving environmentally responsible strategies and proactive responses to ecological challenges (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2019; Courrent et al., 2018; Ruiz-Ortega et al., 2025). Studies in this stream argue that entrepreneurial firms integrate environmental and social concerns into their strategic behavior, which leads to superior environmental and financial performance (Dickel, 2018; Roxas et al., 2017).

The second stream adopts a KBV, conceptualizing EO as a driver of learning and knowledge processes that ultimately determine firm adaptability and performance. From this view, EO fosters knowledge acquisition, creation, and application—core processes that enable firms to innovate and respond to dynamic environments (Hughes et al., 2022; Li et al., 2009; Real et al., 2014). Mechanisms such as absorptive capacity, learning orientation, and knowledge creation have been shown to mediate or moderate the EO–performance link, highlighting the explanatory power of KBV in understanding heterogeneity in entrepreneurial outcomes (Alegre & Chiva, 2013; Jiang et al., 2016; Keh et al., 2007).

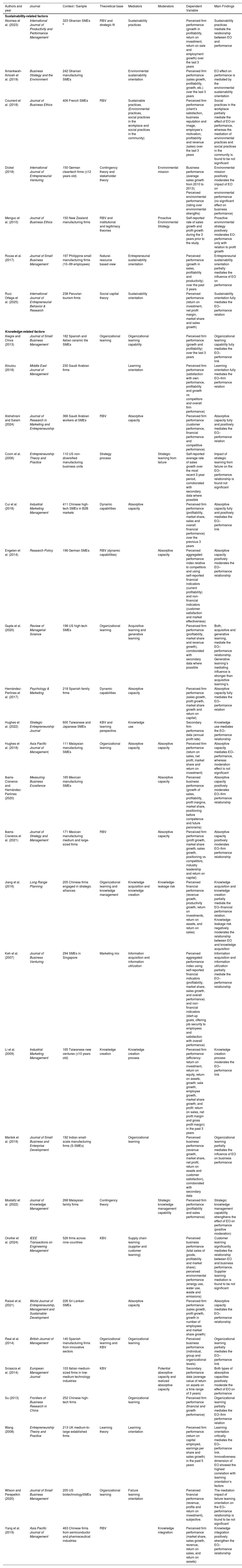

Table 1 provides an overview of the studies that examine mediating and moderating mechanisms linking EO to performance through sustainability- and knowledge-based pathways. The synthesis reveals two main insights. First, sustainability-based studies have primarily focused on environmental strategy or sustainable practices as mechanisms translating EO into performance, but few have incorporated innovation explicitly into this link. Second, knowledge-based studies have extensively examined learning and absorptive capacity as mediators or moderators, but they rarely connect these processes to environmental outcomes. This gap highlights the limited integration of these perspectives and suggests the need to examine how EO activates knowledge resources to foster green innovation and, through it, improve both environmental and financial performance.

Overview of EO–Performance Studies: Sustainability- and Knowledge-Based Mediating and Moderating Mechanisms a.

| Authors and year | Journal | Context / Sample | Theoretical base | Mediators | Moderators | Dependent Variable | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability-related factors | |||||||

| Akomea et al. (2023) | International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management | 323 Ghanian SMEs b | RBV and strategic fit | Sustainability practices | Perceived firm performance (growth in profitability, return on investment, return on sale and employment growth) over the last 3 years | Sustainability practices mediate the relationship between EO and performance | |

| Amankwah-Amoah et al. (2019) | Business Strategy and the Environment | 242 Ghanian manufacturing SMEs | Environmental sustainability orientation | Perceived firm performance (sales growth, profitability, growth, etc.) over the last 3 years | EO effect on performance is mediated by the environmental sustainability orientation | ||

| Courrent et al. (2018) | Journal of Business Ethics | 406 French SMEs | RBV | Sustainable practices. (Environmental practices, social practices in the workplace and social practices in the community) | Perceived firm performance (client’s satisfaction, business reputation and image, employee’s motivation, profitability and revenue (sales) over the last 3 years | Social practices in the workplace partially mediate the effect of EO on performance, whereas the mediation of environmental practices and social practices in the community is found to be not significant | |

| Dickel (2018) | International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing | 150 German cleantech firms (≤12 years old) | Contingency theory and stakeholder theory | Environmental mission | Business performance (average sales growth from 2010 to 2013); Perceived environmental performance (rating over environmental strengths) | Environmental mission positively moderates the impact of EO on environmental performance (no significant effect on business performance) | |

| Menguc et al. (2010) | Journal of Business Ethics | 150 New Zealand manufacturing firms | RBV and institutional and legitimacy theories | Proactive Environmental Strategy | Self-reported rate of sales growth and profit growth during the 3 years prior to the study | Proactive environmental strategy positively moderates EO-performance only with relation to profit growth | |

| Roxas et al. (2017) | Journal of Small Business Management | 197 Philippine small manufacturing firms (10–99 employees) | Natural-resource based view | Entrepreneurial sustainability orientation | Perceived performance (growth in sales, profitability and productivity) over the past 3 years | Entrepreneurial sustainability orientation partially mediates the influence of EO on performance | |

| Ruiz-Ortega et al. (2025) | International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research | 238 Peruvian tourism firms | Social capital theory | Sustainability orientation | Perceived performance (return on investment, net profit margin, market share and sales growth) | Sustainability orientation fully mediates the EO–performance relation | |

| Knowledge-related factors | |||||||

| Alegre and Chiva (2013) | Journal of Small Business Management | 182 Spanish and Italian ceramic tile SMEs | Organizational learning | Organizational learning capability | Perceived firm performance (growth and profitability) over the last 3 years | Organizational learning capability fully mediates the EO–performance link | |

| Aloulou (2018) | Middle East Journal of Management | 230 Saudi Arabian firms | Learning orientation | Perceived firm performance (satisfaction with own performance, profitability and growth vs. competitors and overall firm performance) | Learning orientation fully mediates the EO–firm performance relation | ||

| Alshahrani and Salam (2024) | Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship | 366 Saudi Arabian workers at SMEs | RBV | Absorptive capacity | Perceived firm performance (customer performance, financial performance and competitive performance) | Absorptive capacity fully and positively mediates the EO–performance relation | |

| Covin et al. (2006) | Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice | 110 US non-diversified manufacturing business units | Strategy process | Strategic learning from failure | Self-reported average rate of sales growth over the most recent 3-year period, corroborated with secondary data where possible | Impact of strategic learning from failure on the EO–performance relationship is found not significant | |

| Cui et al. (2018) | Industrial Marketing Management | 411 Chinese high-tech SMEs in B2B markets | Dynamic capabilities | Absorptive capacity | Perceived firm performance (profitability, market share, sales and overall financial performance) over the previous 3 years | Absorptive capacity fully and positively mediates the EO–performance link | |

| Engelen et al. (2014) | Research Policy | 196 German SMEs | RBV (dynamic capabilities) | Absorptive capacity | Perceived aggregated performance index relative to competitors and using self-reported financial indicators (current profitability) and non-financial indicators (customer satisfaction and market effectiveness) | Absorptive capacity positively moderates the EO–performance relationship | |

| Gupta et al. (2020) | Review of Managerial Science | 198 US high-tech SMEs | Organizational learning | Acquisitive learning and generative learning | Perceived firm performance (profitability, market share and revenue growth), corroborated with secondary data where possible | Both, acquisitive and generative learning, mediate the EO–performance relationship. Generative learning’s mediating influence is stronger than acquisitive learning’s. | |

| Hernández-Perlines et al. (2017) | Psychology & Marketing | 218 Spanish family firms | Dynamic capabilities | Absorptive capacity | Perceived firm performance (sales growth, profit growth, market share growth and return on capital) | Absorptive capacity fully mediates the EO–performance relation | |

| Hughes et al. (2022) | Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal | 600 Taiwanese and Japanese SMEs | KBV and learning perspective. | Knowledge use | Secondary firm performance data (annual profit rate) | Knowledge use mediates the EO–performance relationship | |

| Hughes et al. (2018) | Asia Pacific Journal of Management, | 111 Malaysian manufacturing SMEs | Organizational learning | Absorptive capacity | Absorptive capacity | Perceived firm performance (return on sales, net profit, market share and return on investment) | Absorptive capacity mediates EO–performance, whereas moderation effect is not significant |

| Ibarra-Cisneros and Hernández-Perlines (2020) | Measuring Business Excellence | 165 Mexican manufacturing SMEs | Absorptive capacity | Perceived business performance (growth of sales, profitability, profit margins, market share, positioning before competence and future panorama) | Absorptive capacity positively moderates EO–firm performance relationship | ||

| Ibarra-Cisneros et al. (2021) | Journal of Strategy and Management | 171 Mexican manufacturing medium and large-sized firms | RBV | Absorptive capacity | Perceived firm performance (profit growth, market share growth, sales growth, positioning vs. competitors, industry leadership and return on capital) | Absorptive capacity positively moderates EO–firm performance relationship | |

| Jiang et al. (2016) | Long Range Planning | 205 Chinese firms engaged in strategic alliances | Organizational learning and knowledge management | Knowledge acquisition and knowledge creation | Knowledge-leakage risk | Perceived financial performance (revenue growth, productivity growth, return on investments, return on assets, and return on sales) | Knowledge acquisition and knowledge creation partially mediate the EO–financial performance relation. Knowledge-leakage risk negatively moderates the relationship between EO and knowledge acquisition |

| Keh et al. (2007) | Journal of Business Venturing | 294 SMEs in Singapore | Marketing mix | Information acquisition and information utilization | Perceived aggregated performance index using self-reported financial indicators (profitability, market share, sales growth, and overall performance) and non-financial indicators (start-up goals, offering job security to employees and satisfaction with overall performance) | Information acquisition and information utilization partially mediate the EO–performance relationship | |

| Li et al. (2009) | Industrial Marketing Management | 165 Taiwanese new ventures (≤10 years old) | Knowledge creation | Knowledge creation process | Perceived firm performance (efficiency: return on investment, return on equity, return on assets; growth: sale growth, employee growth, market share growth; and profit: return on sales, net profit margin and gross profit margin) in the past 3 years | Knowledge creation process moderates the EO–performance link | |

| Mantok et al. (2019) | Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development | 192 Indian small-scale manufacturing firms (S-SMEs) | Organizational learning | Perceived business performance (revenue growth, market share, net profit, return on assets and customer satisfaction), corroborated with secondary data | Organizational learning partially mediates the influence of EO on business performance | ||

| Mostafiz et al. (2022) | Journal of Knowledge Management | 268 Malaysian family firms | Contingency theory | Strategic knowledge management capability | Perceived firm performance (profitability and sales performance) | Strategic knowledge management capability strengthens the effect of EO on performance (positive moderation) | |

| Onofrei et al. (2024) | IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management | 526 firms across nine countries | KBV | Supply chain learning (supplier and customer learning) | Perceived business performance (total sales of goods, profitability and market share); perceived environmental performance (energy use, water use, waste and emissions) | Customer learning significantly mediates the relationship between EO and business performance. Supplier learning mediation is found to be not significant | |

| Raisal et al. (2021) | World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development | 226 Sri Lankan SMEs | Absorptive capacity | Perceived firm performance (sales growth, profit growth, growth in number of employees and market share growth) | Absorptive capacity mediates the EO–performance relationship | ||

| Real et al. (2014) | British Journal of Management | 140 Spanish manufacturing firms from innovative sectors | Organizational learning and KBV | Organizational learning | Perceived business performance (individual, group and organizational levels) | Organizational learning partially mediates the EO–performance link | |

| Sciascia et al. (2014) | European Management Journal | 103 Italian medium-sized firms in low-medium technology industries | KBV | Potential absorptive capacity and realized absorptive capacity | Secondary performance data (average value of return on assets on a time range of 3 years) | Both types of absorptive capacities positively moderate the effect of EO on performance | |

| Su (2013) | Frontiers of Business Research in China | 252 Chinese high-tech firms | Organizational learning | Perceived firm performance (financial and growth performance) | Organizational learning partially mediates the EO–firm performance relation | ||

| Wang (2008) | Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice | 213 UK medium-to-large established firms | Learning theory | Learning orientation | Perceived firm performance (return on capital employed, earnings per share and sales growth) in the past 5 years | Learning orientation critically mediates the EO–performance link. Innovativeness dimension of EO showed the highest correlation with learning orientation’s factors | |

| Wilson and Perepelkin (2020) | Journal of Small Business Management | 205 US biotechnologySMEs | Organizational learning | Failure learning orientation | Perceived financial performance (revenue, profits and return on investment), subjective. | The mediation impact of failure learning orientation on the EO–performance relationship is found to be not significant | |

| Yang et al. (2019) | Asia Pacific Journal of Management | 463 Chinese firms from semiconductor and pharmaceutical industries | RBV | Knowledge integration | Perceived firm performance (market share, sales growth, revenue, return on sales, and return on assets) | Knowledge integration positively strengthen the EO–performance relationship | |

aNote: This table includes only sustainability- and knowledge-based mediating and moderating mechanisms examined in prior studies. Firm performance is classified at the organizational level and excludes product-level, export, innovation, and international performance measures for comparability purposes.

b SMEs, Small and Medium Enterprises.

Building on the RBV and KBV, this study proposes an integrative framework to explain how and when EO translates into superior performance through environmentally sustainable innovation. The RBV emphasizes that firm-specific resources and capabilities form the basis of competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993). In this sense, EO can be understood as a strategic resource that enables firms to identify and exploit opportunities through innovative actions that improve both environmental and financial outcomes. The KBV complements this reasoning by highlighting knowledge as the most critical strategic asset for developing innovation-based advantages (Grant, 1996). In particular, tacit knowledge—rooted in experience, interaction, and learning-by-doing—acts as a catalyst that allows entrepreneurial initiatives to become effective green innovations (Gunday et al., 2011; Nonaka & von Krogh, 2009). It enhances firms’ ability to integrate environmental principles into their products and processes, make informed decisions under uncertainty, and continually adapt to environmental challenges (Wu et al., 2023). Together, these perspectives provide a more comprehensive understanding of how EO, supported by tacit knowledge, drives environmentally sustainable innovation and strengthens organizational performance.

Accordingly, this study addresses the following research questions:

- •

RQ1. How does EO influence environmental and financial performance through green product and process innovation?

- •

RQ2. To what extent does tacit knowledge strengthen the effects of EO on green product and process innovation?

- •

RQ3. How does tacit knowledge condition the indirect effects of EO on environmental and financial performance through green innovation (i.e., a moderated mediation mechanism)?

Based on the preceding literature review, we propose the conceptual framework depicted in Fig. 1. Building on this integrative perspective, the following sections develop the theoretical rationale and hypotheses that explain how EO, tacit knowledge, and green innovation jointly influence firm performance.

EO and green innovationGreen innovation refers to the development and implementation of new or significantly improved products, processes, or practices that reduce environmental impact and contribute to sustainable competitiveness. The literature commonly distinguishes between green product innovation and green process innovation (Cassânego et al., 2025; Tang et al., 2018). Green product innovation focuses on designing and manufacturing products with minimal environmental impact throughout their lifecycle, whereas green process innovation involves improving technologies and production systems to reduce pollution and resource consumption (Chen et al., 2006; Tariq et al., 2017).

EO represents a firm’s strategic posture for identifying and exploiting opportunities through innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). It reflects the organization’s inclination to explore new market opportunities and enhance its competitive position by stimulating experimentation, creativity, and receptiveness to change (Suder et al., 2025b; Wales et al., 2021). From the RBV, EO can be understood as a strategic resource that mobilizes and combines firm assets to create value through innovation (Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993). Previous studies have shown that EO promotes both product and process innovation (Al Mamun et al., 2022), as firms with stronger entrepreneurial postures tend to initiate new ideas, adopt advanced technologies, and experiment with novel business practices (Suder et al., 2025b).

Firms increasingly regard green innovation as a strategic opportunity to enhance competitiveness while addressing environmental challenges (e.g., Bocken et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2012). When entrepreneurial behavior is directed toward environmentally oriented opportunities, EO encourages the adoption of eco-innovative ideas and practices that stimulate both product and process innovation (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2019). This orientation allows firms to become first movers in developing environmentally focused solutions and to transform opportunity-seeking behavior into tangible outcomes that strengthen both competitiveness and sustainability (Zhao et al., 2012).

By leveraging their proactive, innovative, and risk-taking tendencies, entrepreneurially oriented firms are better positioned to generate green innovations in products and processes, creating a pathway to sustainable competitive advantage (Huang & Li, 2017). Innovativeness reflects a firm’s willingness to experiment and support creativity and R&D efforts, fostering the development of new environmentally friendly products and improvements in production processes (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Rauch et al., 2009). Green innovation, in particular, demands a mindset focused on novelty, experimentation, and continuous improvement (Huang & Li, 2017). Proactiveness enables firms to anticipate market changes and future environmental requirements, encouraging them to adapt product–market strategies and lead rather than follow in offering sustainable solutions (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Tang et al., 2015). Finally, risk-taking pushes firms to move beyond established routines and invest in uncertain projects—an essential condition for green innovation, which often involves adopting new technologies, modifying existing structures, and allocating substantial resources despite delayed returns (Ahuja et al., 2008; Berrone et al., 2013; Chang, 2011; Chen, 2008).

Therefore, EO provides the foundation for enabling green product and process innovations. Hence, we posit that:

H1. EO positively influences (a) green product innovation and (b) green process innovation.

Entrepreneurial orientation and environmental performance: mediating role of green innovationBuilding on the premise that green innovation is a key pathway through which firms address environmental challenges, this subsection explores how EO indirectly contributes to environmental performance. Environmental performance captures the extent to which firms reduce the ecological impact of their activities by minimizing emissions, waste, and resource consumption (de Burgos-Jiménez et al., 2013). Prior research has consistently shown that green innovation is an important determinant of a firm’s environmental performance (e.g., Huang & Li, 2017; Weng et al., 2015). However, recent studies emphasize that EO rarely exerts a direct effect on sustainability outcomes; instead, it operates through internal mechanisms that align entrepreneurial behavior with environmental objectives (Chavez et al., 2020).

Extensive studies have identified green innovation—encompassing both product and process innovation—as a critical determinant of environmental performance (Huang & Li, 2017; Tian et al., 2023). Green innovation enables firms to optimize resource utilization, reduce negative ecological effects, and comply with increasingly stringent environmental regulations. Specifically, green product innovation involves designing products that minimize environmental impact across their lifecycle while satisfying environmentally conscious market demands (Chiou et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2014). Green process innovation, in turn, focuses on adopting cleaner technologies and improving production efficiency to reduce pollution and resource waste (Chiou et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2014).

Although the direct link between EO and environmental performance remains underexplored (e.g., Dias et al., 2021; Jansson et al., 2017; Niemann et al., 2020), emerging evidence increasingly suggests that entrepreneurial firms tend to frame environmental challenges as strategic opportunities for innovation, differentiation, and long-term value creation rather than as regulatory constraints (Dickel, 2018). EO fosters a forward-looking and opportunity-driven mindset that motivates firms to explore unexploited environmental niches and integrate ecological concerns into their competitive logic (Vedula et al., 2022). Thus, EO not only shapes the firm’s capacity to recognize environmental opportunities but also provides the strategic foundation for translating them into innovation outcomes.

Consequently, EO facilitates the emergence of green innovations that act as the primary mechanism through which entrepreneurial behavior translates into superior environmental performance. Rather than directly improving environmental outcomes, EO stimulates the development of eco-innovative products and processes that transform entrepreneurial intent into measurable sustainability achievements. Such innovations promote more efficient use of materials and energy, reduce waste and emissions, and foster cleaner technologies that enhance firms’ legitimacy and long-term environmental performance (Chavez et al., 2020; Huang & Li, 2017).

Accordingly, this study proposes that EO enhances environmental performance indirectly through green product and process innovation. Firms with a stronger EO are expected to identify and prioritize eco-innovative opportunities that translate into tangible environmental benefits.

H2. EO enhances environmental performance indirectly through (a) green product innovation and (b) green process innovation.

EO and financial performance: mediating role of green innovationAlthough EO has been widely associated with superior firm performance (Anderson et al., 2009; Lumpkin & Dess, 2001; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003), empirical findings regarding its financial effects remain inconclusive (Rauch et al., 2009; Suder et al., 2025a; 2025b; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). These inconsistencies suggest that EO does not automatically translate into financial success, but instead requires organizational mechanisms that enable firms to transform entrepreneurial behavior into financial value. In this regard, green innovation provides a critical channel through which EO-driven initiatives are converted into financial outcomes, linking the pursuit of environmental opportunities with efficiency, differentiation, and competitiveness.

Green product and process innovations embody this transformation by aligning entrepreneurial intent with environmentally-oriented value creation. Through the integration of environmental considerations into design and production, firms can achieve cost reductions, improve operational efficiency, and differentiate themselves in increasingly eco-conscious markets (Huang & Li, 2017; Przychodzen & Przychodzen, 2015). Eco-innovative practices such as recycling, energy optimization, and resource-efficient manufacturing not only lower input costs but also strengthen firms’ legitimacy and market appeal, generating higher revenues and long-term profitability (Aguado et al., 2013; Chen, 2008; Fraj-Andrés et al., 2009). Recent evidence further refines this relationship by showing that the financial returns of green innovation may vary over time: Although the quality and overall level of green innovation enhance financial performance in the medium term, an excessive focus on the quantity of innovations may reduce profitability in the long run (Zhang et al., 2025). Thus, green innovation acts as a bridge between the firm’s entrepreneurial inclination and improved financial performance, allowing firms to profit from ecological responsibility.

From the RBV, green product and process innovations constitute strategic capabilities that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and organized, enabling the transformation of sustainability initiatives into a durable financial advantage (Barney, 1991). EO acts as the strategic posture that activates these capabilities by mobilizing firm knowledge, encouraging experimentation, and aligning resource deployment with both environmental and market opportunities. Through this process, entrepreneurial firms can create synergies between innovation, learning, and value creation, thereby turning sustainability-driven knowledge into competitive and financial outcomes (Chang, 2011; Chen, 2008; Ireland et al., 2003).

Thus, EO’s financial impact is realized indirectly, through its influence on green innovation as a mechanism that transforms entrepreneurial and knowledge-based resources into superior financial performance. By fostering eco-innovative products and processes, firms can simultaneously enhance efficiency, achieve differentiation, and secure first-mover advantages in sustainability-oriented markets (Lisboa et al., 2011; Shum & Lin, 2010).

H3. EO enhances financial performance indirectly through (a) green product innovation and (b) green process innovation.

EO and green innovation: moderating role of tacit knowledgeAccording to the KBV, firms can be understood as entities that create, deploy, and store knowledge vital for their success, growth, and survival, making it one of their most critical strategic assets (Felin & Hesterly, 2007; Grant, 1996). Knowledge plays a central role in opportunity recognition and exploitation (Bojica & Fuentes, 2012), helping firms adapt to changing environments through learning and improvisation (Wu et al., 2023).

Particularly, tacit knowledge encompasses know-how, intuition, insights, and expertise gained through hands-on experience, observation, interaction, and learning-by-doing, allowing individuals to develop adaptive responses to dynamic market conditions (Dzenopoljac et al., 2025; Maravilhas & Martins, 2019; Rauch et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2022). Its implicit and experience-based nature allows individuals to make informed and adaptive decisions under uncertainty, a crucial ability when deploying EO. Consequently, it enhances the ability to take calculated risks and proactively identify, pursue, and exploit opportunities that may reduce waste, energy consumption, and environmental impact (Baron, 2008; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003; Zahra & George, 2002).

Although tacit knowledge is often regarded as a direct source of innovation (Gunday et al., 2011; Wuytens et al., 2024), it can also be understood as a condition that determines how effectively EO fosters green innovation. EO represents the strategic posture and the willingness to pursue new opportunities (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996), but this orientation must be supported by the knowledge and experience that allow ideas to be translated into practice (Nonaka & von Krogh, 2009; Zahra & George, 2002). Firms with high levels of tacit knowledge are more capable of using their intuition, shared experience, and informal communication to convert entrepreneurial initiatives into environmentally oriented actions (Grant, 1996; Wu et al., 2023). By contrast, when this type of knowledge is scarce, EO may fail to translate into effective environmental actions, reducing the likelihood of developing concrete green innovations (Galbreath, 2019; Subramaniam & Venkatraman, 2001; Xie et al., 2022).

Knowledge and learning-based resources have long been recognized as key drivers of innovation and firm performance (e.g., Cristache et al., 2025; D’Souza & Fan, 2022; Dzenopoljac et al., 2025; Li et al., 2009). In the context of environmental innovation, knowledge is often tacit and new to many firms, which makes its absence a major barrier to adopting sustainable practices (Galbreath, 2019; Subramaniam & Venkatraman, 2001; Xie et al., 2022). As it emerges from experience and continuous learning, tacit knowledge promotes creativity, helps identify opportunities, supports problem-solving and experimentation, and encourages collaboration across the organization (Monteiro et al., 2019; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Polanyi, 1966). This experience-based understanding allows firms to more effectively incorporate environmental principles into product design, production processes, and everyday decision-making.

Taken together, these arguments indicate that tacit knowledge strengthens the influence of EO on green innovation by providing the practical understanding needed to turn entrepreneurial ideas into sustainability-oriented results. It helps firms develop both green product and process innovations that improve efficiency and environmental outcomes (Azapagic et al., 2004; Zahra & George, 2002), contributing to sustained competitive advantage (Santos-Vijande et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2023).

H4. Tacit knowledge positively moderates the relationship between EO and (a) green product innovation and (b) green process innovation.

Building on the RBV and the KBV, we argue that tacit knowledge represents a critical and scarce organizational resource that amplifies the impact of EO on green product and process innovation, thereby reinforcing both environmental and financial performance. Therefore, our final hypotheses posit that:

H5. Tacit knowledge strengthens the mediation effect of (a) green product innovation and (b) green process innovation on the relationship between EO and environmental performance such that the associations become stronger at high levels of tacit knowledge.

H6. Tacit knowledge strengthens the mediation effect of (a) green product innovation and (b) green process innovation on the relationship between EO and financial performance such that the associations become stronger at high levels of tacit knowledge.

MethodsData collectionWe collected data from the Spanish textile industry, selecting this sector because of its significant environmental impact (Roy et al., 2020) and the expectation that firms within this industry would demonstrate diversity in entrepreneurial actions, tacit knowledge, and green innovations, providing sufficient variability in the study’s independent variables. To collect data, we distributed a structured questionnaire to general managers of firms with at least 10 employees. The initial sample consisted of 874 firms, from which we obtained 302 completed questionnaires.

Following a preliminary examination of the data, 58 responses were removed because of incompleteness or classification as outliers. The final dataset subjected to analysis comprised 244 valid entries, yielding a response rate of 27.92 %. Table 2 provides an overview of the sample characteristics.

Respondents’ characteristics (N=244).

In line with Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) recommendations, we took several steps during the questionnaire's design and administration to address concerns related to common method bias (CMB). First, we removed titles of dimensions and variables to prevent respondents from identifying the constructs being tested, thereby minimizing bias. Second, we clearly communicated to the respondents that their anonymity was guaranteed and emphasized the importance of providing sincere responses to reduce evaluation apprehension. Finally, we assured them that there were no right or wrong answers to any of the items, encouraging honest participation.

To mitigate nonresponse bias, we employed t-tests and Kolmogorov‒Smirnov two-sample tests. A comparative analysis was performed on two key characteristics of the respondents—specifically, the number of employees and the Return on Assets (ROA)—and those of the nonrespondents. The outcomes of our t-tests revealed no statistically significant variances in the mean size (t = 0.523) or the mean ROA (t = 0.324) between the two cohorts. Furthermore, the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov two-sample tests corroborated these findings, as evidenced by the p-values for both size and ROA, which were 0.423 and 0.478, respectively.

In addition to the mail survey, this study utilized archival data obtained from the Sistemas de Análisis de Balances Ibéricos (SABI) database. The SABI database includes both financial information as well as data on locations, industrial sectors, and other miscellaneous details.

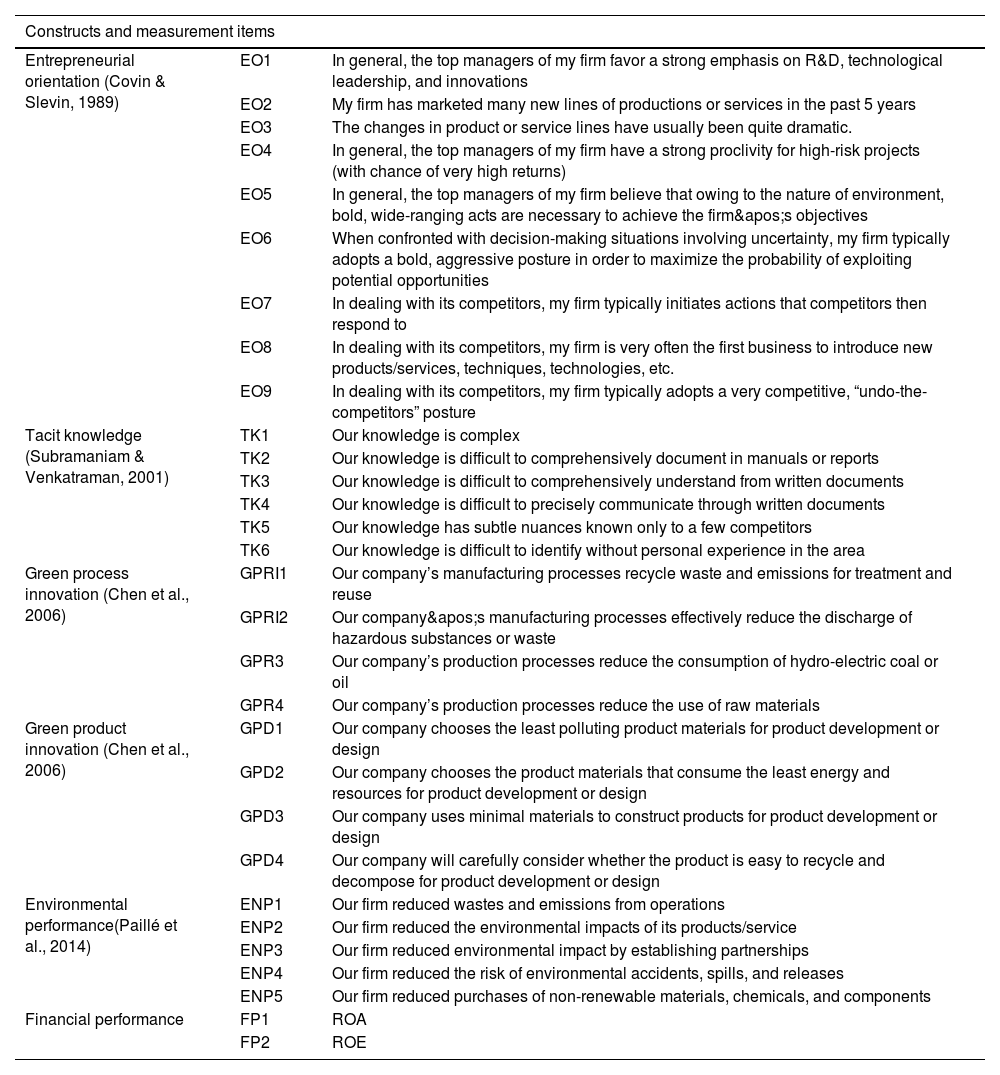

MeasuresThe constructs in this study were measured using a 7-point Likert scale. Validated scale items for measuring all the variables were adapted (with slight modifications but with caution not to change the original meaning) or taken from previously used and validated measures. Appendix A provides a detailed list of the measurement items.

Independent variablesEO was measured using the 9-item scale developed by Miller (1983) and validated by Covin and Slevin (1989). This scale evaluates the firm’s levels of innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness. A sample item is: “The changes in product or service lines have usually been quite dramatic.” EO measurement has long been the subject of scholarly discussion (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996), with some researchers adopting a unidimensional specification that captures the common variance across innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking, thereby reflecting the firm’s overall entrepreneurial posture (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Miller, 1983). In this study, we follow the unidimensional approach because it portrays EO as a holistic strategic attribute of the firm. This choice is consistent with reviews that stress the importance of aligning measurement with the research objective, noting that the unidimensional form is particularly suitable when EO is examined as an overarching organizational orientation (Wales et al., 2020). This decision is also supported by empirical evidence, with meta-analytic findings showing that the dimensions of EO tend to operate together and that the unidimensional construct provides strong predictive validity for performance (Rauch et al., 2009). More recent meta-analytic work confirms this, demonstrating that EO’s predictive power is stronger when modeled unidimensionally or through shared variance rather than as strictly multidimensional (Niemand et al., 2025). Given that our theoretical model focuses on the overall strategic role of EO in driving green innovation and firm performance, the unidimensional specification offers a conceptually consistent and parsimonious representation, also recommended in similar integrative EO models (e.g., Hodgkinson et al., 2023; Hughes et al., 2021).

Tacit Knowledge was measured with a six-item scale from Subramaniam and Venkatraman (2001). A sample item is: “Our knowledge is difficult to comprehensively document in manuals or reports.”

Green product and process innovation were assessed using the scales developed by Chen et al. (2006), which have been extensively used in the literature (e.g., Rehman et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023). Green product innovation, which reflects how firms transform green ideas into new products, was measured using four items. A sample item is: “Our company chooses the product materials that consume the least energy and resources for product development or design.” Green process innovation evaluates the extent to which a firm’s processes have been improved to reduce pollution and minimize resource waste; it is also measured using four items. A sample item is, “Our company’s manufacturing processes effectively reduce the discharge of hazardous substances or waste.”

Dependent variablesWe assessed environmental performance using the scale developed by Paillé et al. (2014), which has been extensively employed in recent research (Zahoor & Gerged, 2021). Respondents evaluated the extent to which their organization effectively manages and minimizes its environmental footprint. A sample item is: “Our firm reduced purchases of non-renewable materials, chemicals, and components.”

To assess financial performance, we utilized a two-item scale derived from secondary data obtained from the SABI database. The first metric, ROA, is calculated as Net Income divided by Total Assets, whereas the second metric, Return on Equity (ROE), is calculated as Net Income divided by Equity. Both financial indicators are widely used in prior research to assess financial performance (Duque-Grisales & Aguilera-Caracuel, 2021; Sandberg et al., 2023). These metrics provide valuable insights into a firm’s profitability relative to its assets and equity, respectively.

Control variablesTo account for possible alternative explanations, we included several control variables. Data for these variables were sourced from the SABI database. Prior literature suggests that a firm’s size and age may influence its innovation performance (Wang et al., 2021) as well as its overall performance (Martínez-del-Río et al., 2012; Zahoor & Gerged, 2021). Firm size was measured by the number of employees, and firm age was determined by the number of years since establishment.

Additionally, given that previous studies have highlighted the impact of prior financial performance on current firm performance (Labella‐Fernández et al., 2025), we controlled for this variable using a latent construct composed of four indicators. This construct includes the two financial performance metrics (ROA and ROE) from the prior two years.

Controlling for CMBTo some extent, concerns about CMB were mitigated through the use of multiple data sources and procedural remedies (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Nonetheless, because the study relied on self-reported data, potential biases in the relationships among variables may still persist. To address this issue, we employed statistical methods.

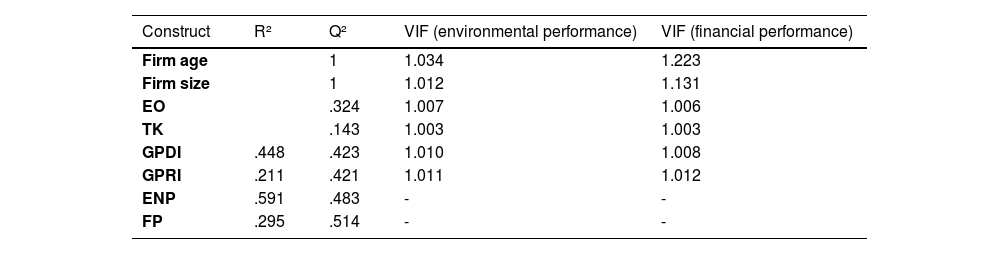

First, we applied Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) by conducting an exploratory factor analysis using SPSS, incorporating all the measurement scales included in the model. A principal component analysis with unrotated solutions revealed five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor accounting for 39.03% of the variance, indicating that no single factor dominated. Second, following Kock’s (2015) recommendation, we assessed the full collinearity of the partial least squares (PLS) model to assess potential CMB. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values did not exceed the threshold of 3.3, as presented in Table 5, indicating the absence of multicollinearity and single-source data bias in our research model. Therefore, the results from both approaches suggest that CMB is not a serious concern in this study.

Additionally, we employed the marker variable technique to control for CMB (Simmering et al., 2015). Specifically, we selected a construct theoretically unrelated to our study’s focal variables and included a three-item scale capturing respondents’ interest in fashion (Reynolds & Darden, 1971). The fashion-interest measure consisted of three items. This marker was modeled as a latent variable in our confirmatory factor analysis, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78, composite reliability (CR) of 0.85, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.62. Importantly, the analysis of the fashion-interest marker against the core constructs of our model revealed no significant correlations, reinforcing the conclusion that CMB did not substantially affect our research findings.

Finally, we applied a common latent factor (CLF) approach, allowing a method factor to load on all observed variables (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The comparison between models with and without the CLF showed no meaningful differences in standardized loadings (all below 0.20) and no significant improvement in model fit. These results further indicate that CMB is unlikely to represent a serious threat to the validity of our study’s conclusions.

Data analysis and resultsWe employed the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) approach using Smart PLS 4 software to test the research model (Ringle et al., 2024). This method is widely recognized in entrepreneurship and management research (Cristache et al., 2025). PLS-SEM was considered the most suitable approach for several reasons. First, it enables the simultaneous estimation of multiple relationships and is particularly effective for models that incorporate mediation and moderation effects, which are central to our framework (Hair et al., 2017). Second, PLS-SEM does not impose strict assumptions of multivariate normality and is well suited for medium-sized samples such as ours (n = 244) (Chin, 1998; Reinartz et al., 2009). Third, unlike covariance-based SEM, PLS-SEM is especially valuable in studies that emphasize causal-predictive analysis rather than theory confirmation, which aligns with the objectives of this research (Hair et al., 2017). Taken together, these features make PLS-SEM the most appropriate technique to capture the complexity of the relationships examined in this study.

Following the guidelines of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) and Hair et al. (2017), the analysis proceeded in two stages: First, the measurement model was assessed to establish reliability and validity, and second, the structural model was evaluated for hypothesis testing.

Measurement model assessmentFirst, we checked the individual item reliability. All item loadings for the scales exceeded the threshold of 0.60, indicating significant contributions to their respective constructs. Moreover, the AVE values were above 0.50, as shown in Table 3. These results confirm that convergent validity was achieved, as both factor loadings and AVE values met the recommended criteria.

Evaluation of the measurement model.

Abbreviations: EO, entrepreneurial orientation; TK, tacit knowledge; GPDI, green product innovation; GPRI, green process innovation; ENP, environmental performance; FP, financial performance.

For construct reliability, we examined Cronbach’s alpha and CR values. As shown in Table 3, all values are well above the recommended threshold of 0.70, demonstrating strong internal consistency.

Additionally, discriminant validity was examined using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio criteria. All HTMT ratios were below the maximum threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015), indicating that discriminant validity was established (Table 4).

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) assessment for first-order constructs.

Abbreviations: EO, entrepreneurial orientation; TK, tacit knowledge; GPDI, green product innovation; GPRI, green process innovation; ENP, environmental performance; FP, financial performance.

After confirming the measurement model, we proceeded to assess the structural model. The Coefficient of Determination (R2) is the central criterion for judging the quality of the adjusted model. The condition for the dependent variables’ R2 values is that they should be greater than or equal to 0.1 (Falk & Miller, 1992). As shown in Table 5, the values of R2 are above the recommended value, indicating good explanatory capability of the model. Next, Stone–Geisser’s predictive relevance (Q2) values were calculated using a blindfolding sample reuse technique. This approach assesses whether the data points of indicators in the reflective measurement model of the endogenous construct can be predicted accurately. Q2 values larger than zero for a particular endogenous construct indicate the path model’s predictive relevance. As presented in Table 5, the Q2 values were greater than zero, demonstrating strong predictive power.

Result of the structural model.

Abbreviations: EO, entrepreneurial orientation; TK, tacit knowledge; GPDI, green product innovation; GPRI, green process innovation; ENP, environmental performance; FP, financial performance.

To test the hypotheses, we conducted a nonparametric bootstrapping procedure to evaluate the significance of the path models. This approach used a 95 % confidence interval with 5,000 subsamples (Henseler et al., 2009). Table 6 presents the results of the hypothesis testing. EO demonstrated a positive relationship with both green product innovation (β = 0.627, p = .000) and green process innovation (β = 0.475, p = .000), providing empirical support for H1a and H1b.

Hypothesis testing.

Control variables: firm size and firm age.

Abbreviations: BI, bias corrected confidence interval; EO, entrepreneurial orientation; TK, tacit knowledge; GPDI, green product innovation; GPRI, green process innovation; ENP, environmental performance; FP, financial performance.

Additionally, to examine the mediation effects of the two parallel mechanisms—green process and product innovation—in the relationship between EO and both environmental and financial firm performance, we used the bootstrapping function in Smart PLS to assess the significance of direct and indirect effects. As noted by Hair et al. (2017), significant direct and indirect effects suggest partial mediation, whereas only significant indirect effects indicate full mediation. We also reviewed the bias-corrected 95% confidence interval values for indirect effects in the bootstrapping analysis. A mediation effect is confirmed when the confidence interval does not include zero (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

The bootstrapping results revealed that both the direct and indirect effects were significant, with confidence intervals that excluded zero, indicating that green product and process innovation partially mediate the relationships between EO and environmental as well as financial performance. Consequently, hypotheses H2a, H2b, H3a, and H3b were supported (Table 6).

Moderation analysisThe moderating effects were tested as part of the structural model. A moderating variable was created by cross-multiplying the standardized items for each construct, forming the interaction term between EO and tacit knowledge. We estimated two structural models including the main effects and the interaction term in relation with green product and process innovation. The results show that the moderating effect on green product innovation was significant (β = .345, p = .003, ΔR2 = 8.2 %), supporting Hypothesis 4a, as well as a significant moderating effect on green process innovation (β = .122, p = .01, ΔR2 = 3.8 %), which supports H4b.

Figs. 2 and 3 illustrate the moderating effect of tacit knowledge on the relationship between EO and green product and process innovation. Both plots reveal that EO had a significant positive relationship with green product and process innovation among firms with high tacit knowledge. Additionally, the figures show that the slope for firms with high tacit knowledge is steeper than that for firms with lower tacit knowledge, indicating that the effect of EO on green product and process innovation is greater for firms with higher tacit knowledge. However, the slope for firms with high tacit knowledge is steeper in Fig. 2 than in Fig. 3, suggesting a stronger moderating effect on green product innovation. This indicates that tacit knowledge has a more substantial impact on amplifying EO’s effect on green product innovation compared to process innovation.

Finally, we used Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 7) to test a moderated mediation model, examining the conditional indirect effects of EO on firm environmental and financial performance through green innovation. As shown in Table 7, these conditional indirect effects of EO were all significant (p < .05) when tacit knowledge was high, with zero not included in any lower-level confidence interval (LLCI) or upper-level confidence interval (ULCI). For both environmental and financial performance, the moderated mediation index was statistically significant, indicating that EO’s effects were mediated by green product and process innovation. Furthermore, tacit knowledge strengthened the impact of EO on both types of green innovation, highlighting its role in enhancing green innovation outcomes. Therefore, Hypotheses H5a, H5b, H6a, and H6b are supported.

Results of moderated mediation analysis.

| Dependent | Independent | Mediator | Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENP | EO | GPDI | .102 | .004 | .021 | .183 |

| GPRI | .154 | .003 | .086 | .222 | ||

| FP | EO | GPDI | .091 | .003 | .029 | .153 |

| GPRI | .123 | .007 | .045 | .201 |

Note: Method: Preacher and Hayes (2008); Moderator: tacit knowledge; Bootstrap: 5000.

Abbreviations: EO, entrepreneurial orientation; GPDI, green product innovation; GPRI, green process innovation; ENP, environmental performance; FP, financial performance.

This study develops and empirically tests a conceptual model that examines how, and through what mechanisms, EO contributes to firm performance through green innovation. Drawing on the RBV and KBV, the model explains how firms transform EO into environmentally sustainable innovation and, consequently, into superior environmental and financial performance. By introducing green product and process innovation as mediators and tacit knowledge as a moderator, the model integrates insights from entrepreneurship, environmental sustainability, and knowledge-based research.

The results confirm that EO significantly promotes both green product and process innovation, reinforcing its role as a catalyst for environmentally sustainable innovation. This outcome aligns with prior and recent research linking EO to innovative and opportunity-seeking behaviors (Castro-Lopez et al., 2025; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Suder, Kusa, Duda, & Karpacz, 2025; Suder, Kusa, Duda, & Okręglicka, 2025; Wales et al., 2021; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). This study extends the EO–innovation relationship into the environmental sustainability domain, where empirical evidence remains limited. Earlier research typically explained the EO–performance link through attitudinal or strategic mechanisms, such as environmental sustainability orientation or proactive environmental strategy (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2019; Menguc et al., 2010), or emphasized internal practices such as lean management systems that mediate the EO–performance relationship (Chavez et al., 2020). By contrast, our findings identify green innovation as a resource-driven mechanism through which EO fosters environmental value creation, bridging entrepreneurship and environmental management literature.

By distinguishing between green product and process innovation, this study provides a more detailed understanding of how EO translates into performance outcomes. Unlike previous studies that conceptualized innovation as a single, undifferentiated construct, our findings reveal distinct yet complementary pathways for product and process innovation. Green process innovation shows a stronger association with environmental performance because of its focus on efficiency and pollution reduction, whereas green product innovation contributes more evenly to both environmental and financial outcomes (Hall & Wagner, 2012; Huang & Li, 2017). These results complement recent studies suggesting that process-oriented innovations deliver more direct ecological benefits, whereas product-oriented innovations allow firms to capture both environmental and market advantages (Tian et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2025). This pattern is broadly consistent with Al Mamun et al.’s (2022) findings that both types of innovation mediate the EO–performance relationship in manufacturing SMEs. However, unlike their results—which found comparable effects for both innovation types—our findings show that the strength and nature of these relationships vary according to the environmental focus. Specifically, green process innovation emerges as a stronger driver of environmental performance, whereas green product innovation exerts a more balanced influence across environmental and financial outcomes. By explicitly incorporating the environmental dimension, this study extends the EO–innovation–performance relationship beyond general innovation settings, showing that EO activates different innovation pathways depending on firms’ sustainability objectives.

The boundary conditions introduced by tacit knowledge further clarify how firms transform EO into green innovation. The results confirm that tacit knowledge strengthens the relationship between EO and green innovation—particularly green product innovation—and, in turn, enhances both environmental and financial performance. These findings are consistent with prior research highlighting the critical role of knowledge-related capabilities such as absorptive capacity, organizational learning, and knowledge creation in supporting innovation processes (Alegre & Chiva, 2013; Cristache et al., 2025; Dzenopoljac et al., 2025; Li et al., 2009; Operti & Carnabuci, 2014) and in reinforcing the EO–performance link (Hughes et al., 2022; Hughes et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2016; Keh et al., 2007; Real et al., 2014).

However, whereas previous studies have largely viewed knowledge capabilities as mediating mechanisms that explain how EO enhances general innovation and economic outcomes (e.g., Hughes et al., 2018; Li et al., 2009; Real et al., 2014), the present results suggest a different pattern. Tacit knowledge operates as a boundary condition that amplifies and moderates the EO–innovation relationship specifically within the context of environmentally sustainable innovation (green innovation). This indicates that EO’s effectiveness depends on both a firm’s entrepreneurial posture and how deeply knowledge is shared, internalized, and diffused across organizational members, rather than on the mere presence of formal learning systems. This focus on the environmental domain refines existing understandings of the EO–knowledge interface, showing that tacit knowledge not only strengthens innovative capacity but also directs it toward environmental objectives. This differs from studies in non-environmental settings, where the moderating role of knowledge tends to be weaker or contingent on external conditions (Alegre & Chiva, 2013; Keh et al., 2007).

Consistent with this reasoning, Suder, Kusa, Duda and Okręglicka (2025) find that the influence of organizational flexibility—whether as a mediator or moderator—varies across market conditions, further emphasizing the contingent nature of the EO–performance relationship. These findings highlight that the EO–performance link is shaped by firms’ internal knowledge systems and the environmental orientation of their innovation efforts. Overall, they remain consistent with the KBV (Grant, 1996; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995), which explains how firms convert strategic orientations into innovation and performance outcomes through knowledge creation and application.

Taken together, the moderated mediation findings provide a more comprehensive understanding of how EO drives sustainable competitiveness. The results indicate that EO affects environmental and financial performance indirectly through green product and process innovation, and that these indirect effects are stronger when firms possess higher levels of tacit knowledge. To our knowledge, few studies have simultaneously examined how EO’s effects unfold through both mediating and moderating processes within an environmental context (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2019; Dickel, 2018; Wales et al., 2021). This pattern advances earlier work that tended to examine mediation and moderation independently (e.g., Hughes et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2016; Real et al., 2014), suggesting instead that both processes interact and reinforce one another. Whereas previous studies often viewed knowledge as a linear enabler of innovation, the present results reveal that tacit knowledge amplifies the mediating role of green innovation—particularly green product innovation—in translating EO into performance. In this sense, EO provides the strategic impetus for green innovation, whereas tacit knowledge enhances its depth and impact by supporting the internalization and practical application of environmentally-oriented ideas. By evidencing this interplay, the study moves beyond single-process explanations and strengthens the theoretical integration of the RBV and KBV as complementary perspectives for explaining how firms achieve sustainable competitive advantage.

ConclusionsTheoretical contributionsOur study introduces a novel perspective on the EO–performance relationship by integrating insights from the RBV and KBV. This dual-theoretical approach provides a coherent lens to understand how EO translates into environmental and financial performance through green innovation, and how tacit knowledge shapes this process. Building on this foundation, we make three main theoretical contributions.

First, this study advances the EO–performance debate by clarifying the mechanisms through which EO affects firm performance. Although numerous studies have examined the EO–financial performance link, most have relied on subjective, self-reported measures. By contrast, our research employs objective indicators of financial performance, which the literature recognizes as providing stronger validity (e.g., Wales et al., 2021; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). Moreover, prior work has paid limited attention to the environmental mechanisms through which EO influences both financial and environmental outcomes. Drawing on the RBV, we address this gap by demonstrating that green product and process innovation act as the pathways through which EO enhances firm performance. This contribution advances existing theory by embedding environmental mechanisms into the EO–performance relationship and by providing greater methodological rigor through the use of objective performance measures (Hall & Wagner, 2012; Huang & Li, 2017; Zhang et al., 2025).

Second, this study contributes to the KBV by emphasizing the unique role of tacit knowledge as a boundary condition in the EO–green innovation relationship. Although prior research has identified knowledge-related resources such as absorptive capacity or organizational learning as contingencies shaping EO outcomes, these studies have largely focused on explicit or formalized capabilities (Alegre & Chiva, 2013; Hughes et al., 2018; Real et al., 2014). By contrast, this research highlights tacit knowledge—experiential, non-codified, and embedded in organizational routines—as a distinct and underexplored resource that determines the extent to which EO fosters green innovation. In doing so, it responds to recent calls for a deeper examination of knowledge types in entrepreneurship and innovation research (Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020) and extends the KBV by showing that the experience-based dimension of knowledge conditions the effectiveness of EO in generating environmentally sustainable innovation (Wu et al., 2023; Wuytens et al., 2024).

Third, this study contributes to the entrepreneurship and sustainability literature by proposing and testing a moderated mediation framework. Prior research on EO has largely emphasized direct effects or simple mediation models, paying less attention to how mechanisms and contextual factors interact (Hughes et al., 2018; Rauch et al., 2009; Suder et al., 2025a; 2025b). EO is inherently dynamic and context-dependent, which underscores the need for integrative frameworks that capture both its mediating and moderating processes (Wales et al., 2021). Our model addresses this need by showing that green product and process innovation mediate the EO–performance relationship, and tacit knowledge conditions the strength of these indirect effects. By integrating the RBV and KBV, the framework captures both the resource-based processes through which EO generates value and the knowledge-based contingencies that shape their effectiveness.

Together, these contributions refine theoretical understanding of how EO drives environmentally sustainable value creation within firms, offering an integrative explanation of how and when EO enhances environmental and financial performance.

Managerial implicationsThe results of this study offer several important implications for managers. The findings suggest that EO should be strategically directed toward green innovation to maximize its impact on performance. Managers should therefore integrate environmental goals into their innovation strategies and ensure that these objectives are aligned with broader organizational priorities. This can be achieved by prioritizing projects that combine business growth with measurable improvements in resource efficiency or emissions reduction. Establishing dedicated budgets, defining specific performance indicators, and linking managerial incentives to these targets are practical ways to ensure that entrepreneurial behavior translates into tangible results.

A second implication of this study is the need to maintain a balance between green product and green process innovation. Whereas process improvements directly enhance efficiency and environmental performance, product innovation generates benefits in both environmental and financial terms. Managers should avoid focusing exclusively on one dimension. A balanced approach may involve upgrading production systems with cleaner and more efficient technologies, while simultaneously developing new products that integrate environmental criteria and differentiating the firm in the marketplace. For instance, redesigning packaging to reduce waste or developing products that meet environmental certification standards allows firms to improve efficiency while meeting customer expectations. Such initiatives not only enhance operational effectiveness but also open new business opportunities in markets where green differentiation creates competitive advantage.

The study also highlights the critical role of tacit knowledge and internal knowledge-sharing mechanisms. EO creates opportunities, but without organizational structures that facilitate the exchange of experiential knowledge, its potential impact remains limited. Managers can strengthen this process by promoting collaboration across departments, encouraging mentoring relationships between experienced and new employees, and organizing internal workshops to share lessons learned from innovation projects. These practices help capture and disseminate knowledge that is often difficult to codify but essential for improving products and processes. By fostering a culture of collective learning, firms increase their ability to identify, refine, and implement green innovation initiatives.

Another key implication concerns the management of organizational knowledge resources. Entrepreneurial initiatives are more effective when firms can leverage their existing knowledge and transform it into actionable innovation. Managers should therefore evaluate how knowledge flows within the organization and identify barriers that hinder its diffusion, such as departmental silos or communication gaps. Developing systems to document and share experiential insights, or using digital platforms to connect dispersed teams, can help integrate knowledge across functional areas. When internal expertise is limited, collaborations with universities, suppliers, or industry associations can provide access to complementary knowledge. Ensuring that EO is supported by strong knowledge management practices is essential to achieving tangible environmental and financial results.

In summary, EO should not be regarded as an isolated orientation but as a strategic posture that becomes most effective when integrated with green innovation and supported by tacit knowledge. Managers who establish clear environmental objectives, balance product and process innovation, and strengthen knowledge-sharing mechanisms will be better positioned to achieve both environmental and financial performance while building long-term competitive advantages.

Limitations and future researchThis study has several limitations that open avenues for future research. First, our research is centered on the Spanish textile industry, a context characterized by its focus on fashion and apparel production, intense competition, and growing pressures for sustainability. Although this setting offers valuable insights, the applicability of our findings to other industries or regions remains uncertain. Future research could broaden the scope to include diverse countries and sectors, exploring how cultural, economic, and regulatory differences influence the observed relationships. Expanding the analysis across varied contexts would enhance the robustness of our model and provide a deeper understanding of the interplay between EO, tacit knowledge, green innovation, and performance in different environments.

Second, although several procedural and statistical remedies were applied to control for CMB—including Harman’s single-factor test, full collinearity assessment, the marker variable technique, and a common latent factor test—some residual bias may still exist owing to the use of self-reported data for certain constructs. The results of these tests indicated that CMB was not a significant concern; nevertheless, future studies could further minimize this potential bias by collecting data from multiple respondents within each firm or using time-lagged data collection procedures.

Third, as with most survey-based studies, our cross-sectional design limits causal inference and raises potential endogeneity concerns. Although our theoretical framework provides a strong basis for the hypothesized causal directions and objective performance data (ROA, ROE) were used to mitigate single-source effects, unobserved variables or reciprocal relationships may still influence the results. Future research could strengthen causal validation by employing longitudinal or multi-wave designs, or by integrating qualitative methods such as interviews or case studies to capture the dynamic and context-dependent processes through which EO, tacit knowledge, and green innovation interact to affect performance.

Finally, future studies could also explore additional boundary conditions or mediating factors—such as organizational culture, dynamic capabilities, or policy instruments—to deepen understanding of the mechanisms driving eco-innovation. Moreover, investigating the social outcomes of green innovation, including sustainable job creation and community well-being, would enrich the broader implications of EO for sustainable development.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAna Labella-Fernández: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Carlos Martínez-Egea: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Belén Payán-Sánchez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Agencia Nacional de Investigacion-AEI and the European Regional Development Fund-ERDF/FEDER-UE: R&D Projects PID2020-119663GB-I00, UAL2020-SEJ-D1872 and PPIT-UAL, Junta de Andalucía-FEDER 2021-2027. Programa: 54.A.Ref (P_FORT_GRUPOS_2023/27). The authors also acknowledge the support of the Research Group SEJ334 – Gestión Estratégica y Formas Organizativas.

| Constructs and measurement items | ||

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial orientation (Covin & Slevin, 1989) | EO1 | In general, the top managers of my firm favor a strong emphasis on R&D, technological leadership, and innovations |

| EO2 | My firm has marketed many new lines of productions or services in the past 5 years | |

| EO3 | The changes in product or service lines have usually been quite dramatic. | |

| EO4 | In general, the top managers of my firm have a strong proclivity for high-risk projects (with chance of very high returns) | |

| EO5 | In general, the top managers of my firm believe that owing to the nature of environment, bold, wide-ranging acts are necessary to achieve the firm's objectives | |

| EO6 | When confronted with decision-making situations involving uncertainty, my firm typically adopts a bold, aggressive posture in order to maximize the probability of exploiting potential opportunities | |