Most firms aspire to longevity, yet only a minority survive more than their initial years. Unsurprisingly, then, business survival has long attracted the interest of many academics. The various factors thought to influence business longevity have generated multiple studies on ownership status, such as family versus non-family business, as an important determinant of business survival. A large body of research has also concluded that firms that innovate are more likely to survive. Finally, numerous studies have found that larger, more mature firms have higher survival rates than their smaller, younger counterparts. Similarly, as suggested in recent business literature, exporting firms appear to have higher survival rates than non-exporting ones. However, there is a significant gap in the joint analysis of these variables, particularly in the case of family firms. To address this gap, the present research seeks to shed new light on the different combinations of factors that lead to success, harnessing the fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) technique to analyze complex business phenomena. The study identifies four pathways to survival. A firm’s innovativeness and exporting activity are key factors that, combined with other identifying characteristics, such as age, size and family status, make up the “survivor's recipe”. These findings not only broaden the theoretical understanding of business survival, but also provide practical tools for strategic decision-making.

Business survival is a critical phenomenon that transcends sectors and geographies, particularly in a global scenario marked by economic uncertainty, intense competition, and technological disruptions. Survival is considered the most significant manifestation of business success, especially in family firms (Colli, 2012). >50 % of businesses worldwide are estimated to fail within their first five years (Wilson & Dobni, 2020), while the rate approaches 60 % in Spain, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE, 2024). This issue is particularly critical for family businesses, which account for approximately two-thirds of all firms worldwide, contribute between 70 and 90 % of annual global GDP and generate between 50 and 80 % of total employment in most countries (Jayakumar & De Massis, 2020). These companies are not only cornerstones of the economy, but also guardians of unique socioemotional capital that influences their strategies and performance (Ahmad et al., 2020).

Although innovation is often portrayed as a safeguard for longevity, the empirical evidence remains inconsistent. While several studies suggest that innovation improves survival prospects, others report null or mixed effects depending on how innovation is measured and the context in which firms operate (Buddelmeyer et al., 2010; Børing, 2015; Cefis & Marsili, 2005; Jensen et al., 2008). This inconsistency raises the central question of when—and for whom—innovation actually improves survival. This is partly explained by the variety in the nature and quality of the innovation measures used, which also hinders cross-study comparisons (Buddelmeyer et al., 2010). Scholars have highlighted the need for more detailed and disaggregated firm-level data to resolve conflicting results and better understand how innovation affects survival (Børing, 2015; Cefis & Marsili, 2005). Recent evidence suggests that the benefits of innovation hinge on complementary conditions such as firm size, exporting activity, and the institutional environment, which can amplify or dampen survival effects (Le Thanh et al., 2022). The literature has identified other key factors associated with firm survival, including age, firm size, and export activity (Wagner, 2024; Zellweger et al., 2012).

A similar tension emerges in the family-business literature: family firms may benefit from patient capital, cohesion, and transgenerational goals, yet they can also encounter strategic inertia or succession challenges that threaten continuity (Goto, 2014; Yilmaz et al., 2024). Taken together, these contradictions suggest that survival is unlikely to be driven by a single factor in isolation, but by configurations of conditions that differ across firms. This motivates a configurational approach able to capture equifinality and conjunctural causation, which we implement by using fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) (El Sawy et al., 2010; Ragin, 2008).

This raises salient questions such as: What specific configurations of factors are determinants of business survival? How do these configurations differ between family and non-family firms? Do family firms exhibit higher survival rates? Is innovation a key factor in survival? What other factors determine survival? In response to these questions, this study adopts a configurational approach with a view to identifying combinations of conditions that foster firm survival. Using the fsQCA methodology on a sample of 51 Spanish firms, of which 43 were still active and eight were no longer in operation, four key pathways to survival were identified: (1) family firms that export, (2) mature family firms, (3) enduring small and medium-sized firms that innovate, and (4) large firms that innovate and export. These findings not only extend the theoretical understanding of business survival, but also provide practical tools for strategic decision-making.

The contributions of this study are both theoretical and practical. From an academic standpoint, it extends the literature on entrepreneurial survival by integrating multiple factors into a configurational analysis, providing a more complex and nuanced view of the phenomenon. Meanwhile, from a practical perspective, the results provide a clear framework for managers and policymakers to design tailored strategies that maximize survival based on the specific characteristics of each firm.

The paper is structured as follows. First, the existing literature is reviewed to establish the conceptual framework. Second, the methodology used is described, including the configurational analysis and the data collected. The results are then presented and discussed in relation to previous studies. Finally, the paper concludes with practical and academic implications, limitations of the study, and avenues for future research.

Firm survival: A theoretical frameworkGiven its impact on economic development and organizational sustainability, business survival has been widely studied in the academic literature. Several theories explain how firms succeed in adapting to dynamic environments (resource-based view, dynamic capabilities theory), overcoming challenges associated with the acquisition and maintenance of resources (resource dependence theory), institutional legitimacy (institutional theory), and environmental factors (population ecology theory) (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Esteve-Pérez & Máñez-Castillejo, 2008; Hannan & Freeman, 1977; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978; Senge, 2013; Teece, 2007). These perspectives have enabled scholars to identify key determinants of survival, such as innovation capacity, size, age, and orientation towards international markets, with these being essential elements for understanding the dynamics of business continuity. Notably, family ownership has received significant attention, with studies arguing that family firms tend to exhibit greater resilience due to their long-term focus, internal cohesion, and intergenerational transmission of knowledge and values (Yilmaz et al., 2024; Zehrer & Leiß, 2019). Hence, this study examines how these variables affect firm survival and primarily explores the role of family ownership and innovation on firm survival.

Authors have frequently contended that family-controlled businesses adopt a longer-term strategic horizon than their non-family counterparts, prioritizing stability and transgenerational continuity (Anderson & Reeb, 2003; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007). This long-term orientation and the patient capital of family owners can confer greater resilience, as evidenced by studies showing that family firms tend to survive longer than others (see, e.g., Morikawa, 2013). Similarly, innovation is widely documented as a critical driver of firm survival. Innovative firms enjoy a “survivor” premium because new products, processes, or technologies can enhance adaptability and competitiveness (Cefis & Marsili, 2006; Ugur & Vivarelli, 2021). Firm size and age also play important roles: larger enterprises benefit from economies of scale and greater resource slack, which improve their odds of enduring over time. In contrast, smaller firms face liabilities of limited scale, and young firms face the classic “liability of newness” (Stinchcombe, 1965; Yang & Aldrich, 2017) –lacking established routines and legitimacy– which elevates their mortality risk. Finally, engagement in export markets is generally associated with a higher likelihood of survival, as exporters diversify their revenue sources and learn from international competition. Empirical evidence indicates that exporting activity can bolster firm survival rates, especially for firms capable of meeting foreign market challenges (Schötz, 2025). Each individual factor has been posited as beneficial for firm longevity in an additive manner, with each factor being assumed to contribute independently to survival.

However, focusing on these factors in isolation, as a checklist of individual effects, provides an incomplete theoretical picture. Configurational theory argues that firm outcomes arise from non-linear combinations of conditions rather than any single factor acting alone. In other words, the influence of a given condition may depend on the presence or absence of others, a principle known as conjunctural causation (Ragin, 2008). Likewise, different configurations of conditions may achieve the same outcome, a concept referred to as equifinality (Fiss, 2011). These ideas are foundational in fsQCA and configurational research, designed to examine how multiple factors jointly produce an outcome. Recent studies in strategy and small businesses have embraced this perspective, finding that no single organizational attribute alone is sufficient for success; instead, it is the combination of key attributes that is decisive. For instance, Cobo-Benita et al. (2016) show that in the context of innovation project performance, no single organizational characteristic is decisive and no single causal path guarantees success; rather, significant interdependencies among size, innovation, and cooperation create multiple pathways to high performance. In a different context, an analysis of around 22,300 service industry small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Korea finds that elements of business-feasibility elements, such as owner capability, productization capability, and profit prospects extend survival, whereas excessive R&D or strong market status can reduce it, underscoring that the benefit of innovation depends on its complementary conditions (Lee, 2023). Likewise, a study on environmentally innovative Vietnamese SMEs shows that the survival effect of eco-innovation reverses unless accompanied by adequate internal capacities and favorable institutional context, highlighting substitution and complementarity across conditions (Le Thanh, Doan Ngoc & To Trung, 2022). Interpreted together, these studies imply plausible multi-condition paths: innovation may substitute for scale where commercialization capability is strong; exporting may compensate for youth by stabilizing demand and accelerating learning; and scale tends to pay off when matched with outward ties and productization strength (Cobo-Benita et al., 2016; Le Thanh et al., 2022; Lee, 2023). Adopting this configurational lens implies that our theoretical framework should go beyond independent, additive hypotheses. We expect firm survival to be driven not by a single factor in isolation, but by specific synergistic configurations of factors acting together.

The analysis that follows first contrasts the survival pathways of family and non-family firms. It then explores the interactions of innovation, size, and firm maturity, and concludes by evaluating exporting.

Survival of family and non-family businessesFamily businesses are a distinctive form of business organization in which ownership and control are closely linked to one or more families. This model combines family dynamics with entrepreneurial objectives, which endows them with unique traits that significantly influence their long-term survival and success. The literature has underlined that family businesses not only excel in their ability to withstand crises, but also succeed in maintaining competitive advantages rooted in their socioemotional resources and commitment to intergenerational legacy (Herrera & de las Heras-Rosas, 2020).

A key factor underpinning the greater resilience of family firms compared to their non-family counterparts is their long-term orientation and their ability to mobilize internal resources, such as social and emotional capital. According to Yilmaz et al. (2024), this orientation facilitates a stronger strategic response to crises, highlighting how family values and internal cohesion contribute to the development of resilient capabilities that strengthen business survival (Yilmaz et al., 2024). In addition, the close relationships between family members facilitate effective transfer of tacit knowledge, which favors continuity in times of uncertainty (Zehrer & Leiß, 2019).

Intergenerational management has also been identified as a critical factor for the longevity of family firms. Recent studies, such as that by Boyd et al. (2023), show that family narratives around survival and legacy play a significant role in bolstering organizational identity and the ability to address strategic challenges. These narratives, often anchored in shared values and goals, provide a frame of reference that reinforces cohesion and commitment among family members, with these being essential elements for resilience and business continuity.

The literature also highlights that family businesses are better equipped to manage crises than non-family firms. Salvato et al. (2020) report that family ownership fosters a more adaptive and proactive approach to disruptive events, allowing crises to harnessed as opportunities for recovery and growth. Their study underscores that the unique socioemotional capital of family firms gives them a unique ability to navigate adverse environments.

In addition, family businesses exhibit a high degree of organizational resilience that arises from their ability to integrate innovative strategies with traditional practices. Engeset (2020) notes that this combination is particularly evident in sectors such as rural hospitality, where the emotional connection to the business and the local community fosters enduring resilience, even in times of economic adversity. The meta-analysis by Duran et al. (2016) reveals that although family firms tend to invest less in innovation compared to non-family ones, they achieve greater efficiency in converting these investments into innovative outcomes. This phenomenon, known as “doing more with less”, suggests that family firms may be more effective in managing resources devoted to innovation, arguably due to greater internal cohesion and a long-term oriented organizational culture (Duran et al., 2016).

Recent research highlights the distinctive characteristics of family firms compared to non-family ones, especially in areas such as investment efficiency, environmental performance, and persistence in international relations. Jin et al. (2023) hold that although family firms tend to exhibit lower investment efficiency, this can be mitigated by favorable regulatory environments, highlighting the crucial role of incorporating socioemotional and gender diversity frameworks in corporate governance to improve performance. For their part, Gavana et al. (2024) explore the impact of structural and demographic board diversity on the environmental performance of family firms, finding that including women on boards has a particularly positive effect, while the length of tenure can moderate this impact. Finally, Aragón-Amonarriz et al. (2025) analyze the persistence of international export relationships in family firms, evidencing that their long-term orientation and relational dynamics, based on mutual trust and socioemotional richness, make them more resilient in contexts of high uncertainty, such as economic crises or culturally distant markets. These findings highlight that family firms balance their financial and non-financial objectives to maximize both sustainability and long-term competitiveness.

Finally, studies such as that by Ahmad et al. (2020) suggest that not only does the active involvement of family owners in corporate social responsibility initiatives enhance organizational reputation, but it also strengthens stakeholder relationships and promotes long-term sustainability (Ahmad et al., 2020). These combined elements bolster family businesses’ ability to not only survive, but also thrive in competitive and challenging contexts.

Considering the above, we can state the following:

Proposition 1 Family businesses have a better survival rate than non-family businesses.

It is widely acknowledged that innovation is an essential component for the survival and success of companies in a business environment characterized by high competitiveness, globalization, and rapid technological advances. In the last century, Schumpeter (1942) provided the first description of innovation as the main driver of economic and business progress, being a means for companies to adapt and renew their products, services and processes in order to remain relevant. A company’s capacity for innovation allows it not only to adapt to changes, but also to anticipate them, giving it a competitive advantage and strengthening its position in the market (Dosi et al., 2006). In this sense, companies that foster innovation tend to be more resilient and better prepared to survive in adverse conditions.

The relationship between innovation and business survival has been widely documented. Cefis and Marsili (2005, 2019) note that innovative firms tend to outperform their competitors in terms of longevity and sustainability. Their analysis evidences that firms investing in research and development and successfully implementing disruptive technologies tend to be more likely to survive, even during economic crises or recession periods. A key aspect of innovation is its capacity to generate adaptability. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the most innovative companies managed to reinvent themselves and rapidly adjust to new market demands, while less innovative firms faced greater challenges to remain operational (Adam & Alarifi, 2021). This highlights the critical role of innovation as a factor of business survival, particularly in contexts of high uncertainty.

Moreover, innovation is not limited only to the development of new products, but also encompasses the improvement of processes and business models. The literature emphasizes that companies that adopt innovative approaches in their organizational strategies can cope more effectively with competitive pressures and changes in consumer preferences. As argued by Hermundsdottir and Aspelund (2021), innovation enables firms to differentiate themselves from their competitors and create sustainable advantages, which strengthens their market position and prolongs their life cycle.

Meanwhile, the impact of innovation varies according to firm size. While large companies tend to have significant resources to invest in innovation, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face constraints that can limit their ability to develop innovative initiatives. However, studies such as that by Rosenbusch et al. (2011) highlight the ability of innovative SMEs to compensate for their lack of resources with agility and creativity, achieving significant results in terms of competitiveness and survival.

In conclusion, a firm's innovativeness is a critical determinant of its survival. Companies that adopt a proactive approach to innovation not only strengthen their resilience in the face of crises and changes, but also ensure their long-term sustainability and success. Therefore, the following proposition is based on a solid body of theory supported by empirical evidence:

Proposition 2 Innovative capacity is a necessary and/or sufficient condition for business survival.

Firm size is a key determinant of survival, particularly in competitive and evolving markets. Fritsch, Brixy and Falck (2006) demonstrated that firms with an initially larger size are more likely to survive, attributing this to their ability to access financial resources, implement economies of scale, and better manage market risks. This finding reinforces the notion that a large-scale entry into a market is associated with stronger expectations of success and greater resilience in the face of economic and operational fluctuations.

More recent studies continue to corroborate this relationship. Mas-Verdú et al. (2015) conclude that firm size acts as a sufficient condition for survival when combined with factors such as industry and innovation. Their analysis suggests that larger firms are better positioned to take advantage of technological and operational opportunities, which significantly improves their longevity. Additionally, Rodeiro-Pazos et al. (2021) highlight that, despite there being a minimum size above which the probability of failure decreases significantly, firms that manage to overcome this barrier enjoy greater competitive advantages and are less vulnerable to changes in the environment.

Evidence also suggests that large firms enjoy greater stability due to their ability to diversify risks and operate in multiple markets. Taken together, these perspectives underscore how size affects a firm's ability to survive:

Proposition 3 Large firm size is associated with higher survival.

Meanwhile, firm age is generally understood as the number of years from the date of incorporation to the time of the study (Choi & Phan, 2014). The relationship between firm age and firm survival has been widely documented. According to Esteve-Pérez et al. (2018), the age of a firm is a critical factor in its survival, especially during the early stages of the industrial life cycle. Younger firms face higher failure rates due to their lack of operational experience and business networks, which is known as “liability of newness” (Freeman, Carroll & Hannan, 1983). In contrast, older companies develop cumulative advantages, such as experience, operational efficiency, and strong stakeholder relationships, which strengthen their ability to withstand market challenges.

Age also plays a role in mitigating financial and operational risks. According to Coad et al. (2018), older firms tend to benefit from economies of scale and higher margins of financial stability, thus reducing the risk of market exit. The relationship is not, however, linear: while young firms have a high probability of failure, more mature firms may encounter challenges related to organizational rigidity (Loderer & Waelchli, 2010) and technological obsolescence. Additionally, Caires et al. (2023) stress that, although mature firms tend to show superior resilience, their performance is conditioned by their ability to innovate and adapt to competitive and changing environments.

Finally, the recent analysis by Esteve-Pérez et al. (2018) emphasizes that the impact of age on survival varies by firm size and industry. Their study found that mature firms, particularly those with a flexible management structure, are more likely to survive in the long term. However, these firms face risks associated with lack of innovation and the accumulation of rigid structures, reinforcing the need for dynamic strategies to ensure their competitiveness. These findings underscore the importance of considering both the benefits and limitations of firm age in the formulation of business policies and strategies:

Proposition 4 Firm age influences the survival of companies.

Export activity has proven to be a key factor in the survival of companies, particularly in an increasingly globalized environment. Participation in international markets allows companies to diversify their sources of income, thus reducing their dependence on the domestic market and mitigating the risks associated with the variability of local demand. Broadly speaking, exporting firms tend to be more productive and efficient than their non-exporting counterparts (Baldwin & Yan, 2016). The pressures and complexities inherent in international competition force firms to improve their productivity, adopt innovations more quickly, and develop more effective strategies to remain competitive, thereby increasing their survival potential compared to firms that are limited to the domestic market (Helpman, 2006; Pearce & Robbins, 1993). According to a study by Wagner (2024), exporting significantly improves a firm’s chances of survival, as those that engage in international trade have a greater ability to withstand economic crises or downturns in domestic demand, resulting in greater stability and long-term sustainability.

Exporting also has a positive impact on firms’ productivity and growth. Dzhumashev, Mishra and Smyth (2016) argue that exporting and productivity investments are complementary activities. While firms face greater uncertainty when first entering foreign markets, over time, exporting firms ultimately benefit from productivity gains that lower their risk of market exit compared to non-exporting firms. This phenomenon is known as “export learning,” where firms gain experience and improve their operations as they interact with international markets (Clerides et al., 1998; Grossman & Helpman, 1993).

Another key aspect related to survival in export markets is export experience. Albornoz, Fanelli and Hallak (2016) showed that accumulated export experience increases the probability of survival in foreign markets. Firms with more years of exporting experience are less likely to leave these markets, because familiarity with foreign market complexities reduces the costs associated with entering and staying in these markets. Companies with differentiated products and a market diversification strategy have a greater probability of success, being better able to adapt to the changing demands of international consumers.

In short, export activity not only facilitates the expansion of companies into new markets, but also improves their global competitiveness and their prospects for survival. Empirical studies show that exporting firms have a higher probability of survival, especially when they diversify their export markets and maintain a strong capacity for innovation and adaptation. Exporting can therefore be considered a key strategy for the long-term sustainability and growth of companies:

Proposition 5 Export activity influences the survival of companies.

The above five propositions (conditions) are not expected to act in isolation. On the contrary, in line with configuration theory, we assume conjunctural causation – that is, combinations of conditions will jointly determine survival (Rihoux & Ragin, 2009). No single factor is likely sufficient on its own; rather, different configurations of these factors can lead to the same successful outcome (equifinality). For example, being highly innovative might compensate for a smaller size, or a strong export presence might offset a firm’s young age. Therefore, rather than a set of independent effects, we conceive our framework as a set of overlapping influences that jointly shape survival. Fig. 1 uses a Venn diagram to illustrate this idea. Each circle represents one condition (family ownership, innovation capacity, size, age, and export activity), and the overlapping regions indicate how these elements may intersect to produce high survival. This set-theoretic depiction (adapted from fuzzy‐set logic) visually reinforces our expectation that particular combinations (intersections) of conditions – not any single factor alone – will form viable “recipes” for firm longevity (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008; Rihoux & Ragin, 2009). In summary, we propose that multiple pathways to survival exist, such that family and non-family firms alike may achieve long-term success through distinct configurations of attributes.

Data and methodDataWe used two criteria to measure company survival. The first was the conventional five-year time horizon, a standard benchmark in business survival studies. The second was a date immediately preceding the global COVID-19 crisis, in order to avoid the interference of pandemic-related exogenous factors.

A 2014 survey of CEOs and managing directors provided our data. This survey yielded a sample of 51 Spanish companies with 50 or more employees. These firms operated in the service sector and the manufacturing sector. Of these 51 firms, 43 were still active in 2019, whereas eight were no longer going concerns.

The original data collection was carried out between May and December 2014 and the selected sample was tested for survival on December 31, 2019, five years later. To determine whether the companies surveyed in 2014 remained active in 2019, we used the Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System (SABI) database developed by INFORMA D&B in collaboration with Bureau Van Dijk. This database provides all types of financial and business intelligence information corresponding to the annual accounts of >2.7 million Spanish companies and >800,000 Portuguese companies.

Data analysis and selection of variablesFollowing Yáñez-Araque et al. (2017), the fsQCA method is a powerful tool that overcomes several limitations of multiple regression analysis (MRA) and structural equation modeling (SEM), such as symmetric causal relationships and net effects (Woodside, 2013; Skarmeas et al., 2014). Unlike these methods, fsQCA offers an ideal alternative for addressing social phenomena with smaller datasets, effectively managing uncertainty and providing clearer insights (Ragin, 2000, 2008). This method is particularly valuable for conducting configurational and causal analyses, enabling a deeper understanding of the complex relationships between variables. For these reasons, the use of fsQCA is especially suitable for the present research. This approach, which was adopted to illustrate a configuration analysis based on fsQCA, follows the proposal of El Sawy et al. (2010). These authors, in turn, align with Ragin's guidelines (2008, Chapter 11), reinforcing the applicability and rigor of the method in this context.

We aim to demonstrate the influence of each variable on the outcome. The outcome and conditions are described and coded as detailed in Table 1. The outcome (i.e., firm survival) is a dichotomous variable that distinguishes active companies from those that no longer exist. The conditions include the type of firm (family or non-family), the degree or capacity for innovation, the size of the company, its age, and its presence in markets beyond the domestic one, such as exports. The type of firm is a dichotomous condition that distinguishes between family firms (coded as 1, fully in this set) and non-family firms (coded as 0, out of the set). The capacity for innovation is a fuzzy-set condition that differentiates highly innovative firms (values close to 1) from firms that are minimally, or not at all, innovative and place little importance on innovation (values close to 0). The measurement of firm size is a fuzzy-set condition based on the number of employees, where medium-sized firms are near 0, and large firms are near 1. Firm age is also a fuzzy-set condition, depending on how old the firm is, with younger firms being near 0 and older firms near 1. Export activity is a dichotomous condition indicating whether a firm exports goods or services (coded as 1, fully in this set) or operates only domestically (coded as 0, out of the set).

Outcome and conditions: description and codifications.

| Outcome/ conditions | Description | Codification |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome:surviv(survival) | Dichotomous variable indicating firm survival for the period 2014–2019 | Survived 1Did not survive 0 |

| Fambus (family business) | Dichotomous variable distinguishing between family and non-family businesses | Family business 1Non-family business 0 |

| Inn (innovative capacity) | Seven-point Likert scale. Mean score of nine-item scale suggested by Prajogo and Sohal (2006). It captures all aspects and criteria for innovative performance | Fuzzy variable |

| Size | Continuous variable that specifies the number of employees | Fuzzy variable |

| Age | Continuous variable that specifies firm age | Fuzzy variable |

| Export | Dichotomous variable that shows whether a firm exports goods or services | Exports 1Does not export 0 |

The data analysis tool used was the FsQCA software version 3.0. (Ragin & Davey, 2016).

fsQCA resultsThis section presents the results of our analysis. We first describe the characteristics of our sample, along with a set-theoretic analysis of the conditions. This is followed by a detailed analysis of necessary conditions, leading to the identification of the causal configurations that contribute to business survival, all based on our fsQCA methodology. Finally, we compare these findings in light of the propositions we initially set forth.

Sample description and set connectionsTable 2 summarizes the characteristics of the sample. Family firms show a higher survival rate (90.91 %) compared to non-family firms, whose survival rate is 72.22 %. Similarly, 90.63 % of exporting firms survive, compared to 73.68 % of non-exporting firms. Additionally, surviving firms demonstrate greater innovation capacity (an average of 5.37 compared to 4.86 in failing firms) and are significantly larger in size (3012.53 employees compared to an average of 129.75 employees). Finally, surviving firms have an average age of 44.77 years, whereas failing firms are younger, with an average of 23.75 years.

Sample characteristics (n = 51).

FB = Family business; NFB = Non-family business; CI = 95 % Non-parametric bootstrap percentile confidence interval, 3000 resamples.

Note. Internal consistency of innovative capacity was excellent (reliability assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and bootstrap percentile CI).

Following Hernández-Perlines et al. (2016), to apply the fsQCA, we first conducted a coding process known as “calibration” (Ragin, 2008). This involves calculating the degree of membership of each case in both its causal conditions and its outcome. To calibrate the continuous fuzzy variables, three thresholds were considered: two extreme points that define full membership and full non-membership, and a crossover point where the condition is neither fully in nor fully out of the set (Ragin, 2000). The degree of membership is a value between 0 and 1 that indicates the input value’s membership in a fuzzy set. In this process, the fuzzy condition for each continuous variable was obtained by prefixing the original variable code with “fs_.” The calibration values were as follows:

- •

fs_inn = calibrate(inn,2.5,4.5,6.5)

- •

fs_size = calibrate(size,800,250,100)

- •

fs_age = calibrate(age,50.5,22.5,10)

The thresholds for innovation capacity on a 7-point scale were 6.5 for extremely innovative firms, 2.5 for firms with low innovation capacity, and 4.5 as the crossover point. The size threshold for medium-sized firms was set between 50 and 100 employees, while the threshold for large firms was 800 employees. The crossover point was set at 250 employees, a typical value used to categorize medium and large firms. Finally, the thresholds for firm age were 10 years, fully out of the set, and 50.5 years, fully in the set. The crossover point was calculated by averaging the age of Spanish firms with >50 employees in the industry and services sectors from the SABI database.

The model for the analysis is:

- •

surviv = f(fambus, fs_inn, fs_size, fs_age, export),

The first step was to examine the necessary conditions for the outcome. Consistency does not exceed the recommended threshold of 0.90 suggested by Ragin (2006)) for any condition (see Table 3). Therefore, no single condition alone ensures survival. However, based on the consistency values, the most important condition, while not necessary, is that of being a family business.

FsQCA necessity analysis (necessary conditions) (outcome variable: surviv).

The symbol (∼) represents the negation of the characteristic.

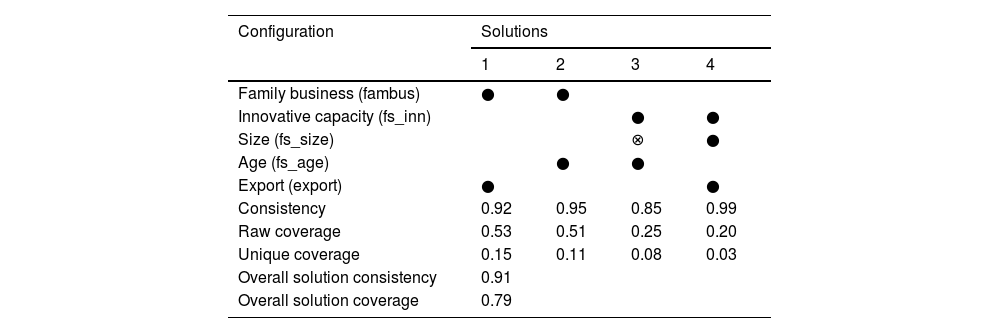

The fsQCA method allows for the analysis of combinations of conditions (causal configurations) that lead to the outcome variable, namely, survival. FsQCA calculates three possible solutions: complex, parsimonious, and intermediate. Following Ragin's (2008) recommendations, this analysis uses the parsimonious and intermediate solutions (Table 4). Causal combinations of conditions that exceed an appropriate consistency threshold are classified as sufficient and are assigned a value of 1 in the truth table. Conversely, causal combinations with a consistency level below or at the threshold are considered insufficient, and the outcome is assigned a value of 0. We set the row-level cut-off at 0.75082, which corresponds to the raw consistency of the last empirically observed row meeting or exceeding 0.75, a commonly cited lower bound for sufficiency coding in fsQCA (with substantially higher thresholds for necessity) (Schneider & Wagemann, 2010, 2012). In evaluating the sufficiency of the resulting configurations, we followed Ragin’s guideline of greater than or equal to 0.80 for configuration/solution consistency (Ragin, 2008). We also used a minimum row frequency of 1 case, appropriate for small-to-moderate N studies, and verified robustness to frequency greater than or equal to 2 (Greckhamer, Furnari, Fiss & Aguilera, 2018). Both the parsimonious and intermediate solutions exhibit solution consistencies of 0.89 and 0.91, respectively, and all reported configurations show consistencies greater than or equal to 0.83, comfortably exceeding the sufficiency benchmark of greater than or equal to 0.80 (Ragin, 2008). These values indicate that the identified combinations are consistently linked to the outcome (survival).

Sufficiency analysis based on fsQCA (truth table analysis) (outcome variable: surviv).

Note. fambus*export, export*fs_inn are prime implicants (counterfactuals). Vector of expected directions (assumptions): surviv = f(1,1,1,1,1). Ragin (2008)) recommends a consistency threshold of 0.80. All configurations meet this threshold. Truth-table parameters: row-level raw-consistency cut-off = 0.75082; frequency threshold = 1 case. The symbol * represents the logical AND operator. Configurations connected by * are sufficient conditions to cause the outcome (i.e., survival).

The notion of causal conditions belonging to core or peripheral configurations is based on these parsimonious and intermediate solutions: core conditions are those that are part of both the parsimonious and intermediate solutions, while peripheral conditions are those that are excluded in the parsimonious solution and thus only appear in the intermediate solution. Consequently, this approach defines the causal core in terms of the strength of the evidence related to the outcome, not the connection with other configurational elements (Fiss, 2011). Table 5 shows the two solutions obtained using the notation introduced by Ragin (2008)).

Configurations for achieving survival.

● Core causal condition presence, ⊗ Core causal condition absence.

● Peripheral causal condition presence.

Note. The dark shaded circles indicate the presence of an element. The crossed circles indicate the absence of an element. The large circles represent core conditions. The small circles represent peripheral conditions. The blank spaces indicate an "indifference situation," where the causal element may be present or absent.

The first configuration is fambusexport, which demonstrates that the combination of being a family business and engaging in export activity is a sufficient condition for survival. The second configuration is fambusfs_age, which means that the combination of being a family business and "longevity" is a sufficient condition for survival. The third configuration is ∼fs_sizefs_innfs_age. Smaller companies with higher innovation capacity and "longevity" are therefore sufficient conditions for survival. The last combination is exportfs_innfs_size. This configuration shows that a sufficient condition for survival is the combination of export orientation, high innovation capacity, and "large size."

These results allow for the evaluation of the five propositions based on the literature review. The results fail to confirm Proposition 1, as family businesses do not always have a better survival rate than non-family businesses. However, longer-lived family businesses and family businesses that export do have a better chance of survival, although other paths leading to survival exist, irrespective of family ownership. This is the case with Proposition 2 (a company’s survival depends on its innovation capacity), which is confirmed for smaller, long-lived companies that are highly innovative, and for larger companies with high innovation capacity and export activity. The analysis does not confirm Proposition 3. The isolated condition of “large size” (i.e., when not combined with other factors) does not lead to the survival outcome. For size (large or moderate) to influence survival, it must be combined with other factors (e.g., innovation capacity, export activity, or age). The data confirm Propositions 4 and 5, which link age and export activity with business survival, provided that these factors are combined with other conditions, such as those previously mentioned.

DiscussionThis study identifies four key configurations associated with business survival, each based on different combinations of characteristics: family ownership with exporting, family ownership with maturity, small and long-lived firms with high innovation capacity, and large firms that both innovate and export. These findings provide new perspectives for the business survival literature.

First, the combination of being a family business and exporting reinforces previous findings on the resilience and strategic flexibility inherent in family businesses. These organizations often demonstrate a greater long-term focus and a unique ability to mobilize socio-emotional resources, facilitating internationalization (Zehrer & Leiß, 2019; Aragón-Amonarriz et al., 2025). Export activity acts as an additional catalyst, providing opportunities to diversify markets and mitigate economic risks (Wagner, 2024). This path highlights the strategic importance of internationalization policies for family businesses.

Second, more mature family businesses show cumulative advantages, such as strong stakeholder networks, operational experience, and economies of scale, which strengthen their competitive position (Esteve-Pérez et al., 2018; Caires et al., 2023). However, their survival also depends on avoiding organizational rigidity and maintaining adaptability (Loderer & Waelchli, 2010). Longevity is a success factor when combined with the condition of being a family business: “the business is the family” (Campopiano et al., 2019), emphasizing the importance of effective succession planning and fostering a dynamic organizational culture.

The third path, that of small and long-lived businesses with high innovation capacity, underscores how agility and creativity can counterbalance resource limitations. Previous studies (Rosenbusch et al., 2011) have shown that innovative small and medium-sized enterprises are capable of generating significant competitive advantages, even with fewer resources. This finding reinforces the role of innovation as an essential dynamic capability for survival, especially in sectors where small and medium-sized enterprises compete in specific market niches.

Finally, large businesses that combine innovation and export activity can improve their survival prospects, highlighting the importance of synergies between substantial resources and international growth strategies. These organizations have access to financial and technological resources that enable them to lead in foreign markets, while innovation acts as a critical differentiator in remaining relevant (Grossman & Helpman, 1993). This path underlines how businesses can use their scale to seize global opportunities while rapidly adapting to technological changes and consumer preferences.

Beyond identifying four survival paths, a configurational reading clarifies why prior linear studies often disagree on the impacts of innovation or exporting: these variables do not act in isolation. Their effects depend on accompanying conditions (size, age, ownership, and market orientation) such that the same lever may be beneficial for one firm but inconsequential for others. By revealing multiple, equifinal recipes and distinguishing core from peripheral elements, fsQCA elucidates when innovation yields benefits, why exporting helps some firms but not others, and where family involvement strengthens the route to longevity (Børing, 2015; Fiss, 2011; Greckhamer et al., 2018; Le Thanh et al., 2022; Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Ugur & Vivarelli, 2021).

Implications for research and theoryTheoretically, these findings expand the understanding of business survival by demonstrating there is no single universal strategy for success; rather, it is achieved through various combinations of factors. This reinforces the validity of configurational approaches and methodologies such as fsQCA for analyzing complex business phenomena.

Our results illustrate how conjunctural causation and equifinality reframe long-standing questions in the survival literature. Rather than asking whether innovation on average raises survival, a configurational lens shows that innovation’s effect is contingent: it tends to be survival-enhancing when paired with complementary conditions (e.g., exporting or scale) and muted when those complements are absent (Le Thanh et al., 2022; Ugur & Vivarelli, 2021). Similarly, exporting improves survival for some firms (e.g., capable niche players or larger innovators) but not others, because its value depends on the surrounding combination of capabilities and constraints (Greckhamer et al., 2018; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). More broadly, the findings advance the neoconfigurational perspective by identifying core vs. peripheral elements within distinct survival “recipes,” thereby specifying boundary conditions for theories of innovation, internationalization, and family-firm resilience (Fiss, 2011; Misangyi et al., 2017). This clarifies why prior linear models report conflicting results: they estimate average net effects while the true data-generating process is configurational.

Implications for business practiceThe practical implications of these results are significant. For managers, these configurations offer clear models for prioritizing investments and strategic decisions, depending on the organizational context and the market. For example, family businesses might benefit from professionalizing their management and fostering internationalization to balance intergenerational stability with adaptability (Gutiérrez-Broncano et al., 2024). Mature family firms benefit when governance that enables a long-term orientation is paired with outward market engagement to avoid inertia. Meanwhile, smaller businesses should focus on innovative niches where their size limitations can be overcome through creativity and agility. Additionally, large firms typically need both innovation and exporting to translate resources into durability (Le Thanh et al., 2022; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). The practical implication is straightforward: complementary elements should be treated as essential. Innovation without commercialization and market access and exporting without product advantage, rarely generate survival benefits; the bundled configuration matters more than any single input (Greckhamer et al., 2018; Ugur & Vivarelli, 2021).

Limitations and research agendaThis study has certain limitations, which may create opportunities for future research. Our condition set is intentionally limited to preserve configurational interpretability given N = 51; this parsimony may constrain generalizability beyond similar contexts. Future studies with a larger N can incorporate new attributes as additional conditions or examine targeted subsamples with richer respondent metadata. While fsQCA is well-suited to small-/medium-N designs, our single-country (Spain) context and modest N may limit the portability of the four identified survival pathways; larger cross-national, multi-industry replications, ideally with richer sectoral, export-intensity, and generational metadata, should test external validity and clarify boundary conditions (Pappas & Woodside, 2021; Schneider & Wagemann, 2010, 2012). Lastly, we deliberately selected a pre-COVID window (2014–2019); later shocks (the pandemic and geopolitical disruptions) may have altered survival dynamics. While this timing does not affect the internal validity of our analysis, we propose future research should evaluate how conditions for business survival change in response to shocks and crises.

We also propose investigating other variables that may influence the survival of family businesses, such as socio-emotional wealth. Additionally, along with innovation capacity, future studies are encouraged to explore other dynamic capabilities, such as absorptive capacity, adaptability, or organizational learning, which could help explain business survival.

ConclusionsTo frame our conclusions, we briefly restate the study’s motivation, objectives, and guiding question. Motivated by persistent inconsistencies in prior work on whether innovation, ownership type, size, age, and exporting help firms endure, we set out to examine survival as a configurational outcome rather than an additive one. Our objective was to identify and compare sufficient combinations of these conditions using fsQCA on a sample of Spanish firms, with special attention to family versus non-family businesses. Accordingly, our main research question was: Under what combinations of family ownership, innovation capacity, firm size, firm age, and export activity do firms exhibit a higher likelihood of survival?

The present study examines these conditions (family business, innovation capacity, size, age, and export activity) that affect business survival, particularly the impact of the type of family business and innovation capacity. The necessity analysis reveals that no single condition ensures survival. However, the type of family business and innovation capacity are key variables. The combination of family business status or innovation capacity with other factors, such as export activity, age, and size, is associated with a greater likelihood of business survival within our Spanish sample and observation window.

Regarding family businesses, being long-lived or engaging in exporting are sufficient conditions for a higher probability of business survival. This finding has practical and theoretical implications regarding the importance of internationalization (exporting), succession and generational change, and the professionalization of management in family businesses. conversely, we find that family businesses may encounter survival issues in the second or third generation, as they may become a source of conflict among the different family members or suffer from the lack of professional management independent of ownership.

Innovation capacity, as part of dynamic capabilities, plays a crucial role in survival when combined with other characteristics. Larger, more innovative companies with export activity, as well as smaller, long-lived companies with high innovation capacity, also find opportunities to ensure their survival.

Funding sourcesThis research was funded by the 2025 Call for Expressions of Interest from research groups for grants supporting applied research projects, within the framework of the University of Castilla-La Mancha’s Own Research Plan, co-funded at 85 % by theEuropean Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (Grant No. 2025-GRIN-38506 Consolidated - OBSERVATORY OF INNOVATION IN COMMERCIAL DISTRIBUTION).

CRediT authorship contribution statementBenito Yáñez-Araque: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Maria Pilar Martínez-Ruiz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Elena Bulmer: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Resources, Project administration, Investigation.