Smart manufacturing (SM) has emerged as a viable solution for small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs) to remain sustainable and globally competitive. However, many SMMEs are not ready for SM and the existing frameworks for SM adoption are unsuitable for supporting SMMEs, as they do not address context-specific preconditions. The objective of this study was to empirically develop a suitable conceptual framework for supporting SMME readiness for SM adoption. A critical realism research cycle using the emergent theory development approach was chosen for the study. A qualitative research design, utilizing multiple case studies, was adopted. The study found that a suitable SMME readiness framework for SM adoption should consider SM Knowledge Competence (SMKC), SM Relative Advantage (SMRA), and SM Compatibility (SMC) as preconditions for SM adoption, as well as Self-Directed Digital Learning (SDDL), Business Model Innovation (BMI), Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) and a Culture of Innovation (CoI) as factors influencing these preconditions. Furthermore, the study revealed that a CoI is an enduring structure with generative powers in the real domain; SDDL, BMI and EO are causal mechanisms prevailing in the real domain when the generative powers of CoI are triggered or activated; and SMKC, SMRA, and SMC are the actions (preconditions) that are triggered in the empirical domain when causal mechanisms are activated. The findings also highlighted stark social and cognitive differences between high-tech SMMEs and non-high-tech SMMEs.

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic severely impacted small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs) in the manufacturing sector globally (Tairas, 2020; Saturwa et al., 2021). The effects ranged from decreased revenue and reduced productivity to increased costs of production and operations (Susanty et al., 2022). For example, South Africa's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell by 10.8 percentage points in the second quarter of 2020 (Statistics South Africa, 2020), while Indonesia experienced a 0.39% decline in GDP as a direct result of the pandemic's impact on the manufacturing sector (Syarifuddin & Setiawan, 2022).

COVID-19 has exposed the vulnerabilities of traditional manufacturing (Bragazzi, 2020). There are early signs that the pandemic is just one of many disruptive health phenomena that may occur in the future (Ettaboina et al., 2021). It is also evident that these types of pandemics are becoming more frequent and severe, as COVID-19 marks the third serious coronavirus outbreak in less than 20 years, following the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) coronavirus in 2002–2003 and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus in 2012 (Yang et al., 2020).

The manufacturing sector is currently transitioning to what is known as Smart Manufacturing (SM). SM refers to a fully integrated, collaborative, and automated modern manufacturing system (Mourtzis et al., 2022). The concept is implemented through the convergence and integration of Advanced Digital Technologies (ADTs) such as cloud computing, the Internet of Things (IoT), Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), big data analytics, and smart sensors. SM is seen as a key solution for the viability, competitiveness, and sustainability of SMMEs (Mittal et al., 2020) in the current era of modern manufacturing. The largest economies in the world by GDP, namely, the United States (US), China, Japan, Germany, and India, are also the leading global manufacturing countries by output (Statista, 2023). This underscores the manufacturing sector's indispensable role in driving global economic growth. In developing countries such as South Africa, SMMEs play a key role as a source of employment and driver of economic growth in the manufacturing sector (Gumbi et al., 2023).

The advent of pandemics such as COVID-19, coupled with the emergence of SM, provides a compelling motivation for manufacturing firms to digitally transform to remain sustainable and viable in the current business environment (Priyono et al., 2020). While a small group of large, high-tech multinational corporations are adopting the SM concept, many SMMEs are not prepared for SM adoption due to context-specific preconditions (Gumbi & Twinomurinzi, 2020; Mittal et al., 2020). Existing frameworks are inadequate for supporting manufacturing SMMEs in achieving SM readiness and adoption, as they fail to address the systemic context-specific preconditions unique to SMMEs (Mittal et al., 2018a; Mittal et al., 2020; Gumbi & Hossana, 2022).

This study, therefore, sought to empirically develop an SMME readiness framework for SM adoption, tailored specifically for manufacturing SMMEs, using a critical realist perspective. The choice of critical realism was motivated by its philosophical stance, which embraces a scientific approach to explanatory theory development based on some degree of objective reality, while also allowing for the emergence of context-specific social structures and constructions (Modell, 2009; Saunders et al., 2009). This perspective recognizes that objective observations are also shaped by personal, social, historical, and cultural contexts (Mukumbang, 2023). Critical realism supports the notion of independent structures influencing the actions of actors in a particular context, while also acknowledging the role of subjective knowledge and reasoning by these actors (Mukumbang, 2023). It combines elements of both positivism and interpretivism to facilitate the development of new knowledge or theory (Mukumbang, 2023). This philosophical stance is essential for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the structures and mechanisms present in the manufacturing SMMEs’ environment concerning their readiness for SM adoption and their experiences with SM. Furthermore, it is instrumental in developing a suitable SMME readiness framework for SM adoption, as it enables the researcher to thoroughly incorporate context-specific conditions, structures, and mechanisms into the framework. The critical realist approach comprises of three stages of retroductive theorizing: the emergent phase, the construction phase, and the confirmatory phase (Mukumbang, 2023). This study focuses on the construction phase. The critical realism approach was deemed to be the most suitable philosophical paradigm to address the study's research questions (RQs) because it acknowledges the existence of an objective reality while considering the subjective interpretations of that reality. Its focus on uncovering causal mechanisms and the underlying structures aligns well with the study's aim to explore and explain the following RQs comprehensively

RQ1 What is the level of SMME readiness for SM adoption in the manufacturing sector?

RQ2 What are the preconditions for SMME readiness for SM adoption in the manufacturing sector?

RQ3 What are the factors influencing the preconditions for SMME readiness for SM adoption in the manufacturing sector?

RQ4 What constitutes a suitable conceptual framework for SMME readiness for SM adoption in the manufacturing sector?

This paper makes a theoretical contribution to knowledge generation by identifying context-specific preconditions, namely, SM Knowledge Competence (SMKC), SM Relative Advantage (SMRA), and SM Compatibility (SMC), as well as the factors that influence these preconditions, namely, a Culture of Innovation (CoI), Self-Directed Digital Learning (SDDL), Business Model Innovation (BMI), and Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO). The paper also makes a practical contribution by providing an SMME readiness framework for SM adoption, offering a practical guide to support SMMEs in the manufacturing sector in their transition from traditional manufacturing to SM.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: "Section 2 - Literature Review" presents the literature review; "Section 3 - Emergent Phase: Theoretical Framework" discusses the theoretical framework of the study; "Section 4 - Research Design and Methodology" outlines the research methodology adopted; "Section 5 - Results and discussion" presents and discusses the results; "Section 6 - Conclusion" presents the conclusion, "Section 7 - Implications" discusses the implications of the study; and finally, "Section 8 - Limitations and future work" presents limitations, and suggestions for future work.

Literature reviewSmart manufacturingThe concept of SM is not new, and various terms have been used to describe digitalization and automated manufacturing since the Third Industrial Revolution, including Flexible Manufacturing (FM), Computer Integrated Manufacturing (CIM), Intelligent Manufacturing (IM), and SM (Kusiak, 2018). There is no generally accepted or standard definition of SM (Kusiak, 2018; Zheng et al., 2018). This lack of consensus has led to definitional variations, resulting in diverse descriptions and conceptualizations of SM (Gumbi & Twinomurinzi, 2020).

While there are many definitions of SM (Davis et al., 2012; Riddick et al., 2016; Thoben et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2019; Mittal et al., 2020), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defines it as a “fully-integrated and collaborative manufacturing system that responds in real-time to meet the changing demands and conditions in the factory, supply network, and customer needs” (Kusiak, 2018). While definitions vary, they all emphasize the use of converged ADTs as key enablers of integrated, collaborative, and automated manufacturing intelligence across both the value and supply chain networks, as shown in Fig. 1.

SM optimization techniques can be applied at the manufacturing enterprise (business) level, manufacturing equipment (shop floor) level, and manufacturing processes (operations) level by deploying ADTs such as the IoT, cloud computing, big data analytics, smart sensors, Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), and Artificial Intelligence (AI)/Machine Learning (ML) (Ghahramani et al., 2020). Smart sensors and IoT/CPS enable data acquisition while AI/ML anomaly detection algorithms are deployed at the process monitoring, control, and production levels. AI/ML applications are used to optimize manufacturing operations and improve production efficiencies at the operations management level. Cloud-based analytics leveraging AI/ML applications are implemented to provide real-time manufacturing decision support at the enterprise planning level.

SMME readiness for smart manufacturing adoptionGumbi & Twinomurinzi (2020) conducted a systematic review to assess the state of SM readiness and adoption by manufacturing SMMEs. The study found that existing research treats SMMEs homogenously, overlooking context-specific challenges such as sector or industry and location-specific challenges. Most research on SM has focused on developed, high-income countries in Europe and the US, creating research gaps regarding SM readiness and adoption in emerging economies, developing countries, and low- and upper-middle-income countries, such as South Africa. The study further found that SMMEs lack awareness of SM, struggle to perceive the relative advantage of SM, and are incompatible with SM due to a lack of expertise, skills, and resources.

According to Gumbi and Hossana (2022), SM trends in emerging economies, developing countries, and low-income countries indicate that current adoption rates are quite low, and these countries are underprepared for the digital transformation phenomenon. Their study revealed that the primary contextual challenges for SMME readiness for SM adoption in these regions include a lack of digital skills and expertise, inadequate broadband and information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure, unreliable electricity supply, limited knowledge of core SM technologies, insufficient investment, and a lack of an entrepreneurial mindset.

SMME readiness frameworks for smart manufacturing adoptionMittal et al. (2018a) conducted a comprehensive systematic review to evaluate the current suitability of existing frameworks for SMME readiness for SM adoption. The study found that existing frameworks are unsuitable for supporting SMME readiness for SM adoption, as they were developed for large firms, particularly those in high-tech industries, and do not consider context-specific SMME requirements. These frameworks fail to address preconditions such as ADT skills, knowledge of advanced manufacturing technologies, limited computer and internet usage, an appropriate mindset for adopting new ADTs, and the lack of an organizational culture conducive to innovation. The study argues that the current starting “level 1” (base level) of most existing frameworks appears disconnected from the actual digitization and SM maturity levels of many SMMEs, thus creating a need for new SM readiness frameworks that define a “level 0” to align with the reality of many SMMEs. Similar to Mittal et al. (2018a); Rahamaddulla et al. (2021) evaluated various frameworks and models, ranging from readiness to maturity models. Their study found that existing frameworks and models are primarily suitable for large firms and that there is still a lack of frameworks and models specifically tailored for SMMEs.

Proposed smart manufacturing frameworksMittal et al. (2018b) developed and proposed an SM maturity model for SMMEs called SM3E. The SM3E is a three-axis maturity model comprising (1) five organizational dimensions (finance, people, strategy, process, and product), (2) five maturity levels (novice, beginner, learner, intermediate, and expert), and (3) seven toolboxes (manufacturing/ fabrication toolbox, design and simulation toolbox, robotics and automation toolbox, sensors and connectivity toolbox, cloud/storage toolbox, data analytics toolbox, and business management toolbox). While the SM3E maturity model clearly defines the process (maturity levels), key organizational dimensions, and capabilities (toolboxes) that must be considered for SMMEs, the model falls short in clearly defining the factors or conditions that influence the progression of SMMEs through the maturity levels. For example, the factors or conditions that will enable an SMME to move from using spreadsheets to store data (novice level) to using fog computing (expert level), in the application of the cloud/storage toolboxes are not defined. Factors such as knowledge competence in ADTs like cloud computing are crucial starting points for SMMEs in emerging economies and low-income countries.

Mittal et al. (2020) proposed and developed an SM adoption framework for SMMEs. The framework consists of five steps: (1) identifying manufacturing data available within the SMME, (2) assessing the readiness of the SMME data hierarchy, (3) developing SM awareness among SMME leadership and staff, (4) developing an SM-tailored vision for the SMMEs, and (5) identifying appropriate SM tools and practices necessary to realize the tailored SM vision. This framework guides SMMEs towards SM adoption. Since the proposed SM adoption framework is based on the SM3E maturity model, it shares the same shortcomings as the SM3E model.

Rahamaddulla et al. (2021) proposed and developed a conceptual framework for SM readiness and maturity assessment. The framework focuses on four key areas: (1) dimensions, (2) thrust, (3) analytic method, and (4) measurement approach, along with five measurement scale levels: (1) technology beginner, (2) technology newcomer, (3) technology learner, (4) technology expert, and (5) technology leader, for SMME SM readiness and maturity assessment. While the analytic method and measurement approach components are useful additions to the discourse of SM readiness frameworks, the proposed conceptual framework offers a very limited explanation of how the elements of the framework interact or influence the process of SMME progression through the measurement scale levels. For example, it is not clear how an SMME moves from a technology beginner (level 1) to a technology leader (level 5).

Yang et al. (2023) proposed and developed a framework called q-ROF-MEREC-RS-DNMA. The objective of the framework is to support SMMEs with decision-making criteria regarding the adoption of information and digital technologies for sustainable SM. The framework uses an algorithm to compute objective and subjective criteria weighting values to assist SMMEs in deciding on the adoption of SM information and digital technologies for the enterprise. This framework falls short in identifying key dimensions, factors, or conditions that influence the adoption of digital technologies by SMMEs.

Innovation adoption theoriesAccording to Hameed et al. (2012), no single theory of innovation adoption exists. Researchers have been using various theories and theoretical models in different contexts of Information Technology (IT) adoption (Hameed et al., 2012; Van Oorschot et al., 2018). However, it is argued that these theories and theoretical models lack a rigorous theoretical foundation and are too simplistic as they fail to consider contextual differences such as contingency variables (Van Oorschot et al., 2018).

Hameed et al. (2012) and later Van Oorschot et al. (2018) conducted an extensive review of IT innovation adoption theories. The authors found that, amongst all innovation adoption theories, Diffusion of Innovation (DOI), Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) are the most widely and commonly used theories in IT innovation adoption studies.

The DOI is a communication or sociological theory used to describe patterns of innovation adoption (Hameed et al., 2012). It was developed to analyze individual-level adoption behavior, and the theory suggests that innovation adoption is contingent on five attributes, namely, relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability of the innovation (Hameed et al., 2012). The limitations of the DOI theory are that it focuses on innovations being adopted autonomously by individuals and, secondly, it is unable to address the full IT innovation adoption process (Hameed et al., 2012).

The TRA is a user acceptance behavior explanatory theory (Al-Suqri & Al-Kharusi, 2015). It postulates that a user's behavior can largely be predicted by their attitudes toward performing the behavior in question and their subjective norms, through the intervening effect of behavioral intention (Al-Suqri & Al-Kharusi, 2015). Subjective norms are determined by the normative beliefs of the user, while attitudes are determined by the user's salient beliefs (Hameed et al., 2012). The TAM is a variant of the TRA and incorporates Perceived Usefulness (“the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance”) and Perceived Ease of Use (“the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort”) into the theoretical model as key attributes that influence user innovation acceptance (Hameed et al., 2012).

The TPB is also an adaptation of the TRA. In the TPB, a variable (Perceived Behavioral Control) that influences the intention towards behaviors is added to the TRA (Hameed et al., 2012). The TRA, TAM, and TPB as innovation adoption theories are largely limited to predicting and explaining innovation usage and user acceptance of the innovation at the post-adoption stages of the adoption processes (Hameed et al., 2012).

The TOE framework postulates that innovation adoption is influenced by the technology context, organizational context, and environmental context (Awa et al., 2015). The technology context relates to factors such as the firm's internal and external pool of technologies as well as the innovation's perceived relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability (Awa et al., 2015). The organizational context relates to factors such as the firm's business scope, top management support, organizational culture, complexity of managerial structure, resources, and size (Awa et al., 2015). The environmental context relates to facilitating and inhibiting factors such as government incentives and regulations/policies (Awa et al., 2015; Bryan & Zuva, 2021). The limitations of the TOE framework are that it assumes factors that are generic to predict the likelihood of innovation adoption and that some of the constructs are more applicable to large organizations than to SMMEs (Awa et al., 2015).

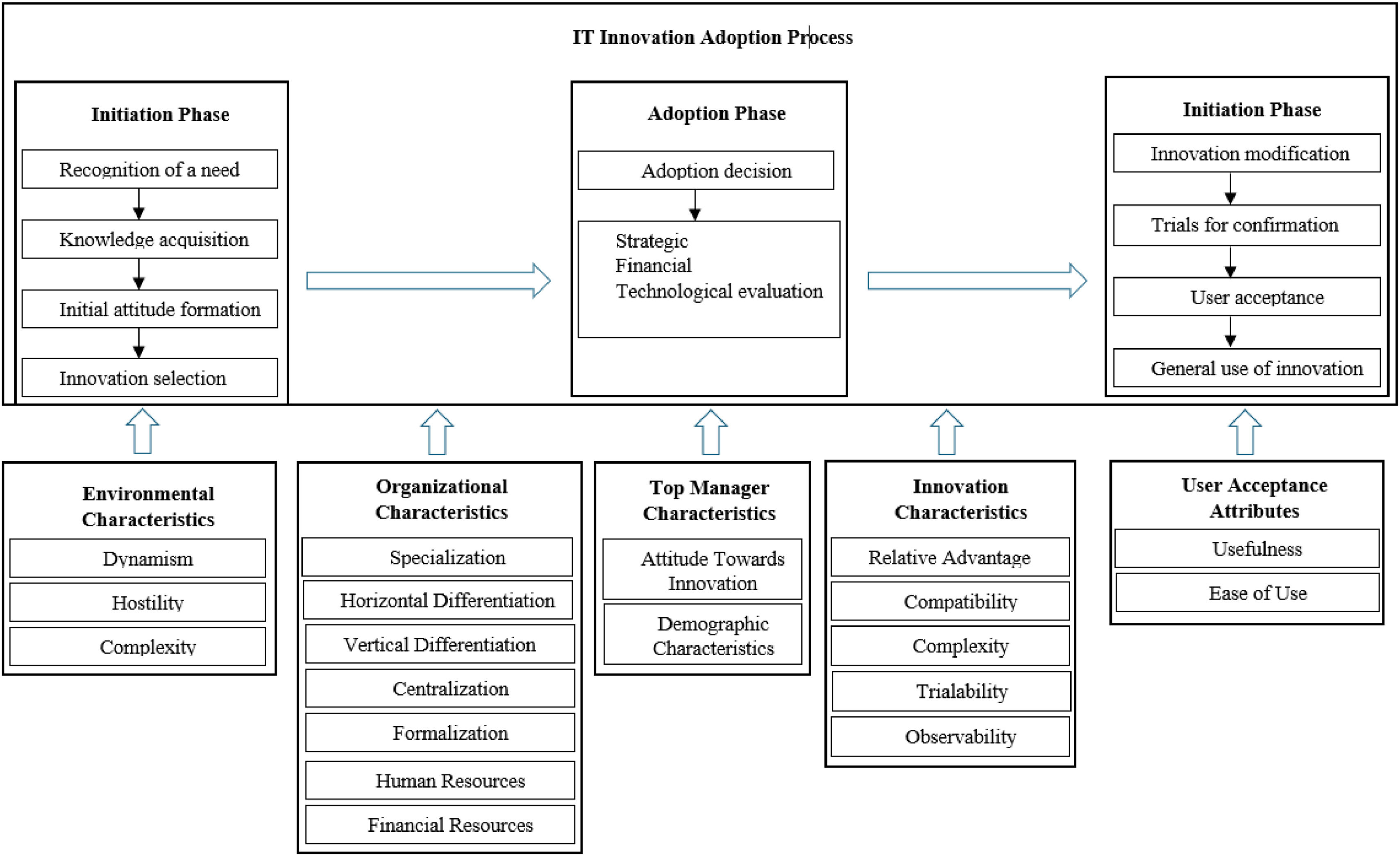

IT innovation adoption follows a three-stage process – initiation phase, adoption decision phase, and implementation phase – where the initiation phase constitutes the preadoption activities; the adoption decision phase concerns the managerial decision to adopt an innovation; and the implementation phase emphasizes the post-adoption activities (Pichlak, 2016). Based on this three-stage IT innovation adoption process, Hameed et al. (2012), developed a conceptual model for IT innovation adoption by integrating DOI, TRA, TAM, TPB, and TOE. Pichlak (2016) modified Hameed et al.’s model and conceptualized an IT innovation adoption framework, as shown in Fig. 2.

Emergent phase: theoretical frameworkGumbi & Twinomurinzi (2020) conducted an extensive systematic review to assess the state of SMME readiness for SM adoption. The study found that SMMEs lack awareness (adequate knowledge) of SM, lack the know-how to perceive the relative advantage of SM, and are incompatible with SM due to a lack of expertise, skills and resources. Gumbi and Hossana (2022) expanded on these findings by conducting a conceptual research study to identify preconditions for SMME readiness for SM adoption and factors that influence these preconditions in emerging economies and low-income countries. The study identified SMKC, SMRA, and SMC as key preconditions for SMME readiness for SM adoption in emerging economies and low-income countries. SMKC refers to the development of SM awareness and knowledge competence in SM ADTs. SMRA refers to having a comprehensive understanding of the benefits of SM and the value that may be derived from it. SMC refers to making high-risk, proactive strategic investments to exploit market opportunities for compatibility with SM requirements. Gumbi and Hossana (2022) further identified that contextual preconditions (SMKC, SMRA, and SMC) may be influenced by SDDL, BMI, EO, and a CoI. SDDL is a method, process, or practice by which knowledge competence related to digital innovations and ADTs is developed. BMI refers to a firm's capability to assess the strategic objective and rationale for adopting technological innovations. EO is a measure of how a business operates strategically to discover and exploit market opportunities. A CoI refers to a set of organizational cultural values, norms, and artifacts which support a company's innovativeness.

The proposed SM frameworks as discussed in the previous section do not include or consider the context-specific (emerging economies and low-income countries) SMME preconditions (SMKC, SMRA, and SMC) or the factors influencing these preconditions, as uncovered by previous studies (Gumbi & Twinomurinzi, 2020; Gumbi & Hossana, 2022). Additionally, the proposed SM frameworks do not indicate the process or factors that influence SM readiness for adoption. The Conceptual Framework for IT Innovation Adoption, as shown in Fig. 2, explicitly identifies a process and factors under which innovation adoption is influenced. However, the process and factors are generic and broad, making them unsuitable for SMME readiness for SM adoption in emerging economies and low-income countries.

In this study, the Conceptual Framework for IT Innovation Adoption (Fig. 2) is adapted to formulate a conceptual SMME readiness framework based on Gumbi and Hossana (2022) approach, as shown in Fig. 3.

A research model theoretically conceptualized by Gumbi and Hossana (2022), as shown in Fig. 4, was adopted in this study. The research model was conceptualized based on the IT innovation adoption process (Fig. 2) as discussed in the preceding sections. The primary objective of this study was to empirically develop an SMME readiness framework from the research model (Fig. 4) to answer the research study questions (RQ1, RQ2, RQ3 and RQ4) posed in the introduction.

Research design and methodologyIn this study, critical realism (philosophy), multiple case studies (strategy), interviews (data collection method), retroduction and abduction (approach), and thematic analysis (data analysis technique) comprised the research design and methodology.

Critical realismCritical realism is a realist meta-theoretical social philosophy introduced by Roy Bhaskar (Bhaskar, 1975). The philosophy is regarded as a systematic realist account of science, presenting itself as a comprehensive alternative to positivism, which is underpinned by the Humean theory of causality laws (Bhaskar, 2013). Bhaskar argues that a sequence of events is neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for causal law (scientific theory) as postulated by the Humean theory. Instead, these events can enable the identification or emergence of causality (theory development) (Bhaskar, 2013). Ontologically, a distinction exists between scientific laws of causality and patterns of events (Bhaskar, 2013). According to Bhaskar, a scientific law must be backed by a theory with presumed causal links (Bhaskar, 2013). At the core of the theory is the conception of structures and mechanisms at work (Bhaskar, 2013). The universality of a theory (scientific law) can only be sustained if the structures and mechanisms can be empirically shown to be independent of the patterns of events they generate (Bhaskar, 2013). Bhaskar argues that positivism cannot explain why, or under what conditions (structures and mechanisms), experience (patterns of events) is significant in science. Bhaskar further elaborates that some real structures and mechanisms exist independently of the events they generate and that the relationship between structures/mechanisms and events can only be understood through empirical findings (experiments). Thus, Bhaskar concludes that causality should be viewed as a function of three domains: the real (structures and mechanisms), the empirical (experience), and the actual (events), from an ontological perspective (Fleetwood, 2005).

Critical realism accepts the existence of a reasonably stable and mind-independent reality (ontological perspective) but rejects the possibility of verifying research findings in any absolute or objective sense (epistemology perspective) (Modell, 2009). Critical realism proposes a tripartite, stratified ontology divided into the domains of the real, the actual, and the empirical (Bhaskar, 1975; Bhaskar, 2009; Bhaskar, 2013; Mukumbang, 2023). The real consists of social/political structures with causal powers to activate mechanisms that can generate events in the actual domain (Modell, 2009; Mukumbang, 2023). The actual domain represents events and non-events that take place in the real domain (Mukumbang, 2023). The empirical domain comprises observable events, which are a subset of the actual, relating to human perception, individual actions and experiences of what happens (Mukumbang, 2023).

Critical realism in manufacturing and other traditional industriesJarvis & Dunham (2003) developed a conceptual framework using critical realism to understand the competitive behavior of rural manufacturing SMEs. The study found that structures and mechanisms (sectoral supply chains, production, and governance) produce four possible outcomes: constrained behaviors, cooperative behaviors, compliant behaviors, and research behaviors, as concrete outcomes of causal processes. Khan & Nicholson (2015) investigated buyer-supplier interactions in the Pakistani automotive industry using critical realism. The study found that agency at the micro level is constrained by structures at the macro level. Stohr et al. (2024) used critical realism to identify generative mechanisms of AI-enabled predictive maintenance implementation within the manufacturing industry. The study found that five generative mechanisms – experimentation, knowledge building and integration, data, anxiety, and inspiration – influence the implementation of AI-enabled predictive maintenance. Aastrup & Halldórsson (2008) and Jeppesen (2005) evaluated the usefulness of critical realism in traditional industries (logistics and manufacturing). The authors concluded that critical realism could be a valuable approach for research in traditional industries to uncover deeper levels of complexities when used in qualitative studies in conjunction with case studies.

Justification for using critical realismSMMEs in the manufacturing sector have context-specific preconditions (actions and experiences that are observed or unobserved in the empirical domain) that need to be captured through deeper empirical probing to ensure that the SMME readiness framework for SM adoption is responsive and relevant to SMMEs. This study was therefore undertaken to empirically develop a deeper understanding of these context-specific preconditions and the factors (structures and mechanisms in the real domain) influencing them, to enable the construction of an SMME-relevant readiness framework for SM adoption (an event in the actual domain).

A critical realist research design has, therefore, supported this study in answering the following research questions:

Real Domain

RQ3 What are the factors influencing the preconditions for SMME readiness for SM adoption in the manufacturing sector?

Empirical Domain

RQ2 What are the preconditions for SMME readiness for SM adoption in the manufacturing sector?

Actual Domain

RQ1 What is the level of SMME readiness for SM adoption in the manufacturing sector?

A critical realist research cycle using the emergent theory development approach was chosen for this study. Critical realist research is based on a scientific approach to the construction of explanatory models and theories (Mukumbang, 2023). The construction of these explanatory models and theories follows three stages of retroductive theorizing: the emergent phase, the construction phase, and the confirmatory phase (Mukumbang, 2023). The emergent phase, discussed in Section 3, has been completed, and its key results were published in Gumbi and Twinomurinzi (2020) and Gumbi and Hossana (2022). This paper focuses on presenting the key findings of the construction phase.

In the construction phase, the explanatory theory is built (constructed) using empirical data (Mukumbang, 2023) based on the conceptual theoretical framework (Fig. 4) discussed in Section 3. Explanatory theory-building generally includes case study research (single or multiple cases) involving formal data collection and analysis methods aimed at supplementing and confirming aspects of the developing theory in the emergent phase (Mukumbang, 2023). A multiple case study qualitative research design was used to answer the research questions and to facilitate the empirical development of the SMME readiness framework for SM adoption. Qualitative research designs and methods are utilized to understand a complex reality and the meaning of actions in a given context (Almeida et al., 2017). Multiple case study research provides an in-depth analysis of context-dependent knowledge and is a highly useful and powerful method for developing new theories (Mittal et al., 2020). SMMEs in the South African manufacturing sector were selected as the case studies for this research.

Multiple case studies: selected cases within the South African manufacturing sectorThe manufacturing sector is the third largest sector in South Africa (Statistics South Africa, 2023), as shown in Fig. 5. The sector's GDP contribution is currently at 13% making manufacturing indispensable to South Africa as a means to achieving envisaged economic growth targets. However, despite this recognition, the sector's contribution to South Africa's economic growth prospects has been declining over the last two decades (Bhorat & Rooney, 2017; Kreuser & Newman, 2018). The sector's GDP has declined from approximately 21% in 1994 (Industrial Development Corporation, 2013) to 13% in 2022 (Statistics South Africa, 2023). Employment in the sector has continued to decline from 1.9 million jobs in 2008 (Statistics South Africa, 2009) to 1.1 million jobs in 2022 (Statistics South Africa, 2023b).

SMMEs in the South African manufacturing sectorSMMEs in the South African manufacturing sector are defined and classified according to the National Small Business Act 102 of 1996 (Republic of South Africa, 1996, 2003, 2004), as shown in Table 1.

The manufacturing sector comprises a total of 198 274 SMMEs across the nine South African provinces (Small Enterprise Development Agency, 2022). Manufacturing SMMEs account for approximately 8% of the total SMME population in South Africa (Small Enterprise Development Agency, 2022). The provinces of Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Western Cape account for more than 80% of all manufacturing SMMEs in the country, while the Northern Cape has the lowest number (less than 1%). The manufacturing sector is dominated by large enterprises when it comes to income contribution; however, in the past decade, the SMME sector has been steadily growing, as shown in Fig. 6 (Statistics South Africa, 2008a; Statistics South Africa, 2019).

Target population for the selected case studiesThe target population for the selection of case studies consisted of micro and very small enterprises, as shown in Table 2. Since the primary objective of the study was to empirically develop an SMME readiness framework for SM adoption, the developed framework needed to take into account the lowest building blocks of small business enterprises (micro and very small enterprises). The unit of analysis was owners of chief executive-level managers of SMMEs, as shown in Table 2. In SMMEs, critical business decisions are typically made by a single owner/manager (Hinde & Van Belle, 2012). Owners/managers also provide the strategic direction for the business, including relevant strategies for developing a highly skilled organizational workforce. This aligns with the views of Ritchie & Brindley (2005) who indicate that the introduction, growth, and long-term survival of an SMME largely depend on the entrepreneurial abilities of the individual who owns and manages the business.

SMME profile.

Semi-structured interviews were used for data collection. These interviews are well-suited to a case study research strategy as they enable the gathering of qualitative data that facilitates the investigation, exploration, deeper understanding, and explanation of contextual factors of a phenomenon within its specific context and setting (Saunders et al., 2009). Due to their distinctive flexibility, semi-structured interviews are regarded as the most important form of interviewing in case study research (Gillham, 2010). A questionnaire with seven SMME background (profile) questions and 25 open-ended interview questions, as shown in Appendix E, was used for data collection.

Purposive samplingRandom purposive sampling (Nyimbili & Nyimbili, 2024) was used to identify the SMMEs to be interviewed. This approach is applied when the researcher has prior knowledge about specific people or events and deliberately selects them because they are likely to provide the most valuable data (Denscombe, 2007). Random purposive sampling selects participants from a larger group (for example, a database) to add credibility to the sample; however, this technique is not intended to ensure generalization or sample representativeness (Nyimbili & Nyimbili, 2024).

Participants in purposive sampling are selected with a specific purpose in mind, reflecting their relevance to the topic of the investigation (Denscombe, 2007). The researchers accessed the database of manufacturing SMMEs through interactions with the Manufacturing, Engineering, and Related Services Sector Education and Training Authority (MERSETA), the Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA) and the Department of Small Business Development (DSBD). Thirty cases were selected randomly from Gauteng, which has a significantly higher proportion of formal SMMEs and the most diversified industries within the manufacturing subsectors compared to other provinces (Small Enterprise Development Agency, 2022). One of the researchers, working within the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), facilitated access to key stakeholders such as MERSETA, SEDA, DSBD, manufacturing experts, and ADT research specialists. Based on the exploratory discussions with these stakeholders, 10 cases were selected from the initial 30, considering a dichotomy between those utilizing ADTs and those not employing ADTs in their business operations.

Of the 10 selected cases, only four were accessible and used in this study. Similar studies (Mittal et al., 2020) researching the SM phenomenon have generally used two case studies. In this study, four case studies were deemed adequate as data saturation was achieved in line with the guidelines of Fucsch and Ness (2015). Data collection occurred from October 2021 to October 2022. The duration of the data collection process was influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic and new data privacy policies, which made it difficult to access SMME databases from state entities such as SEDA, MERSETA and DSBD. Additionally, many manufacturing SMMEs declined to participate due to low confidence arising from limited knowledge competence of the subject matter, that is, SM.

Retroduction and abduction: Logic of inference and reasoningRetroduction is the logic of inference-making espoused by critical realism (Mukumbang, 2023). As a logic of inference, retroduction is typically associated with various forms of abductive reasoning, applied as the researcher moves back and forth between obtained data and an a priori theoretical framework (Mukumbang, 2023). Thus, the two logics of inference (retroduction and abduction) are considered highly complementary (Mukumbang, 2023). Retroduction and abduction are key analytical tools used in critical realism-based research studies (Meyer & Lunnay, 2013). When used together, these inference-making tools are crucial for formulating new conceptual frameworks or theories (Meyer & Lunnay, 2013). They enable a more rigorous form of analysis capable of differentiating the actual from the real by uncovering and understanding the complex processes of research participants (Meyer & Lunnay, 2013). Retroductive and abductive inferences are also complementary to deductive inference, particularly in advancing data analysis beyond the original research premise (Meyer & Lunnay, 2013), which is characteristic of critical realism-based research studies. In this study, retroduction, incorporating abduction, was used to empirically develop the SMME readiness framework for SM adoption. This process involved moving back and forth between qualitatively obtained data, the innovation adoption process (Fig. 3 in Section 3), and the a priori conceptual theoretical framework (Fig. 4) discussed in Section 3.

Data AnalysisAbductive Thematic Network Analysis (ATNA) (Moutinho & Sokele, 2018; Rambaree, 2018) was used for data analysis, the development of the SMME readiness framework for SM adoption, and to answer the study's research questions. ATNA combines Abduction (abductive reasoning), Thematic Analysis (TA), and Thematic Network Analysis (TNA). Abduction is a process of enquiry for forming or explaining research propositions through the use of back-and-forth reasoning between theory and empirical evidence. TA is a process of identifying patterns to formulate themes from collected empirical data. Using TA researchers can organize segments of gathered data into themes, facilitated through coding (Moutinho & Sokele, 2018). TNA is a creative and systematic framework for linking themes in qualitative research. Through TNA, researchers can identify themes and then develop graphical representations of the linkages (networks) between them (Moutinho & Sokele, 2018). TNA can be data-driven, theory-driven, or a combination of both. This flexibility allows Abductive Theory to be combined with TNA, forming ATNA, for qualitative data analysis.

Content Analysis (CA) and TA are two of the most widely and frequently used approaches in qualitative data analysis (Humble & Mozelius, 2022). Both CA and TA identify themes, patterns, or codes inductively or deductively. However, CA is better-suited for broader applications, including both qualitative and quantitative research, larger data sets, and positivistic studies (Humble & Mozelius, 2022). In contrast, TA is more suited for deeper analysis, a more in-depth understanding of phenomena, and “pure qualitative” analysis, and is considered a “flexible method for qualitative analysis” applicable to various research designs (Humble & Mozelius, 2022). In this study, the objective of data analysis was to formulate and explain research propositions, identify patterns and themes, and link themes to empirically construct an SMME readiness framework for SM adoption and answer the research study questions (RQ1, RQ2, RQ3, and RQ4) as posed in the introduction. Thus, CA was deemed unsuitable, as it is constrained in formulating or explaining research propositions and linking themes to construct a framework. While TA is part of ATNA, on its own, it shares CA's limitations in these aspects.

Accordingly, ATNA was employed to formulate and explain research propositions, identify patterns, and link themes to empirically construct an SMME readiness framework for SM adoption. TA was used to open-code the data from transcribed text files, axial code the code groups, and develop the themes. TNA was applied to establish the linkages among the themes, using both obtained data and the adapted innovation adoption process. ATLAS.ti v.22.1.5.0 software was utilized for data analysis, following the steps proposed by Rambaree (Moutinho & Sokele, 2018), as shown in Fig. 7.

Reliability and validityReliability and validity in qualitative research may be attained using the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Zachariadis et al., 2013; Anney, 2014; Connelly, 2016; Cypress, 2017). Credibility was ensured through prolonged engagement with the participants, peer debriefing, and member checks. One of the researchers spent three months in the business environments of the participating SMMEs (prolonged engagement). Peer debriefing was conducted through discussions with manufacturing and ADT research experts within the CSIR. Member checks were carried out through iterative engagements with participants during the data coding process. Transferability was enhanced by employing purposive sampling and providing a thick description of the participants’ lived experiences, which were captured directly from the participants. Dependability was achieved by maintaining an audit trail which included the interview protocol, recordings, and transcribed documents. The coded data, memos, and themes in the transcribed documents were reviewed and validated by an expert and a senior researcher. Confirmability was established by utilizing the innovation adoption theory (Section 3), maintenance of an audit trail (interview protocol, recordings, and transcribed documents), and validating the coded data, memos, and themes through expert reviews. Additionally, iterative engagements with participants during and after the data analysis process further ensured confirmability.

Results and discussionTo answer the research questions posed in the introduction section, a four-step ATNA process was followed, as discussed in the data analysis section (Fig. 7). This section begins with an overview of the selected case studies, followed by a detailed discussion of the key results obtained from the ATNA analysis.

Overview of the selected case studiesA total of four cases were selected and used in this study, as discussed in the overview of selected case studies section.

Case ACase A is an SMME operating within the aerospace industry of the manufacturing sector for more than 20 years. The SMME has expertise in engineering, software capabilities, design, production, assembly, operations, and maintenance of Unmanned Air Systems (UAS). It offers a full package of integrated solutions to its client base. The SMME has extensive experience spanning more than two decades in acquisitions, operational testing, experimental flight testing, aerospace product development, mission engineering, mission support systems development, operational mission analysis, modeling and simulations for intelligent decision support systems, safety and risk management, and optimized operational application of aerospace resources at tactical, operational, and strategic levels. The company has unique capabilities in integrating UAS assets, smart sensors, IoT, AI/ML, and geospatial (satellite) applications into fully packaged, end-to-end solutions to address complex challenges and use cases, such as disaster management. It currently employs nine people, including the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), with expertise ranging from flight test and system engineers to software and aerospace engineers. The SMME has a flat organizational structure with minimal administrative functions. The company's mission is to become a leading AI-based operational decision support systems global solutions provider, leveraging modern technologies such as smart sensors, IoT, AI, UAS, blockchain, and satellites to offer comprehensive solutions for complex challenges and unique use cases.

Case BCase B is a startup company operating in the digital services industry within the manufacturing sector and across various industries for over five years. The Managing Director (MD) has an extensive career in ICT with global expertise and experience gained from working overseas, particularly in the United Kingdom (UK). The SMME partners with leading technology providers such as IBM, research institutions, and universities to provide tailored solutions that meet specific business requirements and needs. It specializes in the design, engineering, manufacturing, operations, and maintenance of IoT sensors. The company combines this expertise with capabilities in cloud computing, AI, ML, data science, and analytics, sourced from strategic alliances and partners, to deliver unique solutions to clients by leveraging BMIs. The SMME's products, including an IoT-based cloud platform, utilize IoT, ML, blockchain, and data analytics to monitor production environments in real-time, enhance efficiency, increase yield and production capacity, and establish best practices through performance benchmarking. The SMME has a flat organizational structure with minimal administrative functions. The company's mission is to use the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and emergent digital technologies to provide tailored solutions that enhance operational efficiencies, reduce risks, and lower the total cost of ownership for its clients.

Case CCase C is an SMME that has been operating in the electronics industry of the manufacturing sector for over 16 years. The company has extensive experience in electronics manufacturing, telecommunications, high-performance computing, Research and Development (R&D), engineering consultancy, and professional services. The SMME comprises three business units: an electronic engineering unit specializing in electronics manufacturing, system design, software design, engineering, training, and consultancy; a built environment unit; and an ICT unit. The company has a manufacturing plant that is currently being automated and modernized for SM to enhance operational efficiencies and increase production capacity. The SMME also possesses extensive capabilities in fifth-generation (5G) Radio Access Network (RAN) technologies and other wireless networking technologies. It has a flat organizational structure with minimal administrative functions. The company's vision is to leverage highly automated manufacturing processes and operations to optimize the efficacy of its flat organizational structure in management, operations, and administration. The SMME is currently exploring expansion to overseas markets, such as the US.

Case DCase D is an SMME established in 2021, operating in the perfume manufacturing industry. Although recently founded, the business owner has over a decade of experience in the perfume industry, having worked in various positions from lower level to top management. The company operates using a hybrid business model of direct selling to customers and multi-level network marketing and selling through distributors. Its primary objective is sustainable development, focusing on empowering independent distributors to achieve financial freedom. The SMME primarily targets domestic markets in the short to medium term. The company is not well-versed in digital technologies and utilizes traditional manufacturing practices and labor-intensive processes. It perceives SM and emergent digital technologies as conflicting with its business model and core vision, which centers on job creation through the sustainable development of distributor businesses. The SMME's vision is to become a leading black-owned direct selling and multi-level marketing perfume manufacturing company.

Empirically developing an SMME readiness framework for smart manufacturing adoptionA four-step ATNA process was followed to empirically develop an SMME readiness framework based on the research model (Fig. 4) to answer the research study questions (RQ1, RQ2, RQ3 and RQ4) as posed in the introduction. TA was conducted to formulate themes (constructs) from the collected empirical data (step 1 and step 2). TNA was conducted to link (connect) the themes (step 3). Abductive reasoning was utilized in step 4 to empirically explain the research model's (Fig. 4) research propositions. Retroduction incorporating abduction was used to move back and forth between qualitatively obtained data and the innovation adoption process (Fig. 3 in Section 3) and the research model (Fig. 4) across all the steps (steps 1 to 4) of the ATNA process.

Step 1: Thematic analysis (Data Coding)In step 1, audio data was transcribed into text files and subjected to open coding, as shown in Fig. 8. Following the process outlined in Fig. 8, 152 codes were generated from 239 quotations, as depicted in Fig. 9. Additional details can be found in Appendix A.

Step 2: Thematic analysis (Formulating themes - constructs)Development of code groupsIn step 2, 32 code groups were formed from the 152 codes using axial coding, supported by 16 analytical reflexive group memos, as illustrated in Fig. 10. This process was guided by the a priori conceptual theoretical framework discussed in Section 3 (Fig. 4). Further details can be found in Appendix B – Table B.1.

Emergent themes: constructsEight themes emerged from the aggregation and categorization of code groups: SMKC, SMRA, SMC, SDDL, BMI, EO, CoI, and SMMERA. The aggregation and categorization of code groups into themes were guided by the a priori conceptual theoretical framework discussed in Section 3 (Fig. 4). Through back-and-forth abductive reasoning between the empirical data and the SM innovation adoption process (Fig. 3), the study determined that the participating SMMEs can be classified as high-tech SMMEs and a non-high-tech SMME. A comparative analysis between the high-tech SMMEs and the non-high-tech SMME is shown in Appendix D – Table D.1.

Smart manufacturing knowledge competence (SMKC)SMKC for the high-tech SMMEs emerged as a theme from the analysis of 24 codes categorized into four code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.2. The theme (SMKC) revealed that high-tech SMMEs have high levels of SM awareness and knowledge competence of SM ADTs. For example, when asked about their understanding and knowledge of the SM concept, the CEO of Case A responded: “My understanding is that when you use smart manufacturing is that you utilize technology such as 3D printing and software tools to enable you to optimize the efficiencies of manufacturing.” The theme (SMKC) further revealed that the high-tech SMMEs are using ADTs such as smart sensors and see these ADTs as very important for their current and future business operations. The CEO of Case A elaborated: “We integrate sensors into aircraft as well, so it's not just on UAVs but it is also on aircraft, we have operational knowledge of how to use them, we've been using them for years.” The CEO further added: “Some of the tools that we are developing are dealing with the IoT, so in other words, the disaster management solution we are working on incorporates real things in the virtual world. That's the IoT using smart techniques to be able to optimize efficiencies… I think from where we stand today, we believe that is the future for the next 20-30 years.”

The SMKC theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of 10 codes categorized into four code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.3. In contrast to the high-tech SMMEs, the analysis of the SMKC theme for the non-high-tech SMME revealed that it has low levels of SM awareness and very limited knowledge competence of SM ADTs. The MD of Case D confirmed: “It's actually the first time to get really engaged with what this is when you sent me the questions and invited me.” The assessment of the theme (SMKC) further revealed that the non-high-tech SMME is not using any ADTs and considers even very basic digital technologies, such as barcodes, to be very expensive. The MD of Case D admitted that her knowledge of SM ADTs is “definitely low” and stated: “Right now we don't, we don't have that; we are not using any technologies as such because it's a hard labor kind of environment right now.” The MD added: “Another thing is that you have, I mean, you have other companies that still use this digital technology where they have barcodes, but barcoding is expensive for a small business.”

Smart manufacturing relative advantage (SMRA)SMRA emerged as a theme from the analysis of 11 codes categorized into three code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.4. The theme (SMRA) revealed that the high-tech SMMEs comprehensively understand the benefits (relative advantage) offered by SM from a value capture, value proposition, and value creation perspective. The CEO of Case A confirmed that SM offers cost reduction (value capture): “If you don't use smart manufacturing, which means optimizing costs and lowering costs for the consumer, you don't have a business.” The MD of Case C identified improved quality (value proposition) as a benefit: “…increased quality, meaning much more measurable quality”, while the MD of Case C identified improved production (value creation) as a benefit: “…increase productivity…And then also I would say even the throughput.”

The SMRA theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of one code and one code group, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.5. In contrast to the high-tech SMMEs, the analysis of the SMRA theme for the non-high-tech SMME revealed that it found it difficult to explain the relative advantage of SM when asked to elaborate on the perceived value and benefits of SM from its own understanding. The MD of Case D could only manage to identify improved production as the relative advantage of SM: “I can say one of the benefits of adopting smart manufacturing would be consistent with our production. You see, the other thing is when you are working with people, sometimes they don't come to work, they're sick. But if a computer will not get sick as often, so once it's set up and it is serviced, the machines are serviced, production will continue.”

Smart manufacturing compatibility (SMC)SMC emerged as a theme from the analysis of 10 codes categorized into three code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.6. The analysis of this theme revealed that the high-tech SMMEs are making long-term capital investments in ADTs and associated skills, digitally enabled manufacturing infrastructure, and their own electricity from renewable energy sources despite barriers such as government policies, access to patient capital, corruption, and limited availability of ADT skills in the country. For example, the MD of Case B confirmed: “IoT plays a big role… we will have investment in terms of sensor development… [and] data analytics, machine learning will be massive investments … blockchain is going to be a combination of getting the right skills in terms of developers that are experienced and how one manages that, so that again there will be investment with technology partners.” The MD of Case C stated: “We want to implement the model ourselves where we decrease our dependence on the national grid… and start generating renewable energy… I'm looking for such a place where it's in a farm area where I can put the factory and have a massive solar facility, at least if I can generate two megawatts or one MW.”

The SMC theme further revealed that the high-tech SMMEs have embraced an entrepreneurial mindset (a growth mindset). The SMMEs strongly believe that they will not survive in the future manufacturing business environment unless they make the necessary long-term investments to transition from legacy manufacturing to SM. The CEO of Case A explained: “You cannot stay small, if you stay small you are dead… businesses work like that, you know, so you can't remain small forever. If not then you going to die and that's what I think is not well understood.” The MD of Case C added: “So, it is impossible to be in the manufacturing space and remain small, without automation, really, I don't see factories in the future becoming anything. I mean, it's either you do it or you're dead, you know.”

The SMC theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of three codes categorized into two code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.7. The analysis of the SMC theme revealed that, in contrast to the high-tech SMMEs, the non-high-tech SMME is not making any investments in elements or requirements of SM due to a lack of knowledge. The MD of Case D elaborated: “Well, I understand the importance of it, but it's not something that we have, we have really looked at like now…. one of the things is lack of knowledge about what smart manufacturing can do for your business, so a lot of research. I don't think small businesses really go out to understand what this is. Like I said, it's actually the first time that, like formally, I get to engage with someone about it ... But if you don't know, it doesn't become a priority.”

Self-directed digital learning (SDDL)SDDL emerged as a theme from the analysis of 23 codes categorized into four code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.8. It is observed from the theme (SDDL), that the high-tech SMMEs have a desire to learn and are intentional regarding learning about SM ADTs as well as other emergent 4IR digital technologies. This is confirmed by the CEO of Case A: “I am at least actively learning a lot…because I believe that blockchain will change how we do things in our business, and moving forward we need to understand it… I mean, right now, I'm learning about Web 3.0.” They display a high level of information acquisition competence, as evidenced by the MD of Case B: “Partners, so collaboration partners, in my instance, it would be universities. So, I engage the university quite a bit, and that is where the guys on both engineering and things like the data analytics, AI side of things.” Additionally, they demonstrate a high level of digital competence, as reflected in the statements of the MD of Case B: “I would say most structured kind of learning comes in, it's OK, a lot of research papers which are that I forgot to mention earlier, so there's a lot of kind of dissertations and PhDs, so the published documents that's available online… a vast array of online resources, so whether that be your MOOCS, the free, OK, free and sometimes there's a cost to it, online courses etcetera.”

The SDDL theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of four codes categorized into four code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.9. The analysis of the theme (SDDL) revealed that in contrast to high-tech SMMEs, the non-high-tech SMME has a very low interest in learning (desire to learn) about digital innovations, including SM and its related ADTs. They are not actively and deliberately seeking out information (learning with intention) about ADTs or any emergent 4IR technologies and are not using or accessing online platforms and resources to develop their knowledge competence of SM and its related ADTs, or acquire any information or knowledge related to digital innovation. The MD of Case D explained that, from their perspective, learning is ad hoc, reactive and happens once in a while: “So, once in a while, you try and find what is the best way of doing certain things. So, it's a developing thing every day, every day you learn, like today I'm learning smart manufacturing.” The MD also attested that they do not use any online platforms and resources as they largely rely on previous experiences for learning and developing knowledge competence: “No, I haven't done that. Most of what we are doing right now, I already like learned everything from my previous work. So, it was just to take whatever that was working and make it perfect.”. The MD further confirmed that they have limited digital competence when it comes to online platforms and accessing online resources: “I haven't went on Google to check it out like that. No, I don't know.”

Business model innovation (BMI)BMI emerged as a theme from the analysis of 10 codes categorized into six code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.10. It is extracted from the evaluation of the theme (SDDL) that the high-tech SMMEs are innovating their business models in multiple ways to exploit the relative advantages of SM. For example, the CEO of Case A is building a specific human resource capability to change the business model: “Cross qualification, so for instance, we try to look for people who can do multiple things, not just one thing… You have to have people who are specialists in multiple things.” Meanwhile, the MD for Case B is adopting AI/ML for data analytics and business intelligence applications to adapt the business model: “Okay, firstly capture as many data points as possible that's contextual and relevant to a process… start using things like machine learning and AI with that then actually start informing decisions… Then the second is adding business intelligence to that … add business logic and automate that business logic so that effectively, you have a platform that can inform you and understands your business model.”

The BMI theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of one code and one code group, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.11. In contrast to the high-tech SMMEs, the analysis of the BMI theme for the non-high-tech SMME revealed that they are finding it extremely challenging to determine which components of their business model need adaptation to exploit SM. This is expected, as it has very limited knowledge competence of SM and how this innovation could be exploited to the benefit of the firm. When asked to elaborate on the changes that would be made to the current business model if SM was to be adopted, the MD responded: “Ohh, I don't know. I don't know how it will change now because, you see, it will not [change] because we started small.”

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO)EO emerged as a theme from the analysis of five codes categorized into five code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.12. It is evident from the appraisal of the theme (EO) that the high-tech SMMEs are proactively engaging in long-term, high-risk investments to strategically discover and exploit new market opportunities. These SMMEs are willing to commit significant investments and resources to market opportunities in uncertain environments, with highly unpredictable outcomes, to stimulate future market growth. For example, the CEO of Case A confirmed: “We take as much risk as we can tolerate. So, our view is that you have to continuously do that.” The MD of Case C added: “Basically, every opportunity has been a risk, every new product, it's basically being done at the risk. The factory is being done, I mean it's only now that we are gonna be getting people who want to manufacture in the factory, but it was all done without an order or without even a promise of an order… even if we lose, it doesn't stop the business.”

The EO theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of five codes and five code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.13. In contrast to the high-tech SMMEs, the analysis of the EO theme for the non-high-tech SMMEs, indicates that its focus is on short term objectives and goals (short-term orientation) and is not willing to proactively take risks to explore opportunities and growth in new markets. For example, when asked if the SMME would consider proactively pursuing and investing in long-term opportunities and projects, the MD of Case D responded: “…you know what, I would, I would really wait it out, I would not yeah. I would wait a bit and not really just jump to it, I would wait and see how it goes…”. When further asked if the SMME would consider pursuing high-risk, long-term opportunities and projects, the MD responded: “No, no, no, no, somebody must first go and get their hands burnt and then fingers burnt and then we'll come. It's a risk when you are still small, you know, don't try to take on an elephant at your first bite.”

Culture of innovation (CoI)CoI emerged as a theme from the analysis of 10 codes categorized into three code groups, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.14. From the theme (CoI), it is determined that the high-tech SMMEs have a culture (values, norms, and behaviors) that facilitates organizational learning, for example, through self-management (Martínez-León & Martínez-García, 2011). This is evidenced by the CEO of Case A: “So, I spend a lot of time trying to recruit people, making sure that we recruit the right people so we don't have to manage anymore. So, we believe that people who are working for us self-manage. If they cannot self-manage then they should not be working here.” Additionally, they foster a culture that promotes innovation propensity, entrepreneurial spirit, creativity, and a risk-taking attitude (Bunyakiati & Surachaikulwattana, 2016). This is reflected in the CEO's statement: “We allow the environment where it is ideas that thrive not your position. That for me is important, that is part of our culture…It's not that kind of heavy management hierarchy, and that agile approach – it's how we just get on with doing things and getting work done. So, it's very much principles around agile working and also as a team.”

The CoI theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of two codes and one code group, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.15. In contrast to the high-tech SMMEs, the analysis of the CoI theme indicates that the non-high-tech SMME appears to emphasize values, norms, and behaviors that focus on respect and restoration. This emphasis is highlighted by the MD of Case D: “I want the whole organization or company to be all about respect for our colleagues, respect that we give to each other, respect that we give in what we do… we are also all about restoration…I believe you get restored when your basic conditions are sort of somehow met at a certain level, so restoration is one of our culture elements that we are bringing in.”

SMME readiness for smart manufacturing (SMMERA)SMMERA emerged as a theme from the analysis of two codes categorized into one code group, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.16. The analysis of the theme (SMMERA) reveals that the high-tech SMMEs are currently investing in SM and using SM ADTs such as cloud computing, the IoT, big data analytics, and smart sensors. When the high-tech SMMEs were asked whether they would be investing, adopting, and implementing SM within the next three years, the MD of Case B responded: ‘Yes, solidly yes… Umm, the next three years. I would say, a minimum of R10 million”, and the MD of Case C added: “Yeah, we will be, yeah.” According to Mittal et al. (2018b, 2018c), when an SMME has spent sufficient time, effort, and resources in practicing the SM paradigm and has developed new SM capabilities, the SMME is considered to be at an intermediate level of readiness for SM adoption. This indicates that the high-tech SMMEs are at an intermediate level of readiness and only one step away from being ready to implement SM (expert level).

The SMMERA theme for the non-high-tech SMME emerged from the analysis of two codes and one code group, as shown in Appendix B – Table B.17. In contrast to the high-tech SMMEs, the analysis of the SMMERA theme indicates that the non-high-tech SMME is not currently investing in SM, is not using SM ADTs, and is not aware of the concept of SM. When the non-high-tech SMME was asked whether it would be investing, adopting, and implementing SM within the next three years, the MD of Case D responded: “Ok, currently we are not ready, within the next three years, I have to make this business work.”Mittal et al. (2018b, 2018c) believe that when an SMME is largely unaware of the SM paradigm and SM relative advantage, the SMME is considered to be at a novice level of readiness for SM adoption. This means that the non-high-tech SMME is at the very lowest level of SM readiness for adoption.

Step 3: Thematic network analysis: linking themes (connecting constructs)Innovation adoption is a phase-based process comprising the initiation phase, the adoption decision phase, and the readiness for the adoption phase (Fig. 4 in Section 3). In the initiation phase, knowledge competence associated with the innovation to be adopted is developed (Gumbi & Hossana, 2022). In the adoption decision phase, the assessment of the innovation's relative advantage from a practical, strategic, financial, and/or technological perspective for resource allocation, as well as whether the innovation supports the goals and objectives of the firm, is conducted (Gumbi & Hossana, 2022). In the readiness for adoption phase, the organization is prepared (made ready) for the innovation's adoption and general use (Gumbi & Hossana, 2022). Thus, for SMMEs to be ready for SM, SMKC needs to be developed in the initiation phase, the SMRA (value/benefits) needs to be assessed in the adoption decision phase, and the required SM investments for resource allocation need to be made in the readiness for adoption phase for SMC.

According to Gumbi and Hossana (2022), SDDL is used as a primary method and core competence in the development of knowledge competence related to digital innovations and ADTs. The authors further explain that for SMMEs to realize (perceive) SMRA, they need to innovate (change or adapt) their current business models (BMI). Gumbi and Hossana (2022) also identified EO as a key factor influencing SMC. According to the authors, a firm's SDDL, BMI, and EO are likely to emerge, develop, and mature in the presence of a CoI. Thus, a CoI is a key factor influencing SDDL, BMI, and EO. Based on the adapted innovation adoption process (Gumbi & Hossana, 2022), which is described in detail in Section 3, the linkages between the emergent themes were established through TNA (Appendix C – Fig. C.1 to Fig. C.11) and network diagrams, as shown in Appendix C – Fig.s C.12 and C.13.

Step 4: Abductive reasoning: pesearch propositionsInitiation phaseThe first stage of any innovation adoption is to develop knowledge competence (awareness and acquisition of knowledge) of the innovation to be adopted. The high-tech SMMEs are using SDDL to develop SMKC, as shown in Appendix C – Fig. C.12. These SMMEs are continuously seeking information on SM ADTs (that is, big data, IoT, cloud computing, smart sensors, AI, and ML) by accessing online platforms such as Google, YouTube, podcasts, Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs), online courses, online research articles, and dissertations. They are also forming strategic alliances with universities and Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to develop SMKC. The non-high-tech SMME is not seeking out information on SM ADTs, is not interested in learning about SM ADTs, and is not accessing and using online platforms to develop SMKC, as shown in Appendix C – Fig. C.13. Consequently, the high-tech SMMEs have adequate levels of SMKC while the non-high-tech SMME has a low level of SMKC.

It is, therefore, proposed that:

Proposition 1 (P1): There is a positive relationship between SMKC and SDDL.

To decide on the adoption of any innovation, a firm must evaluate whether the innovation supports the goals and objectives of the firm from practical, strategic, financial, and/or technological perspectives. Consequently, in this phase, the relative advantage (benefits) of the innovation from the value capture, value creation, and value proposition/offering perspectives must be assessed to evaluate the fit of the innovation for the business.

The high-tech SMMEs have advanced levels of SMKC, enabling them to innovate (change or adapt) their existing business models to capture value (cost reduction, decision support making, performance benchmarking, and standardization of production facilities), create value (improved production, resource efficiency, scalability, improved predictability, improved reliability, and automation), and offer value (improved quality) for their businesses and customers, as shown in Appendix C – Fig. C.12. High-tech SMMEs are innovating their business models by adding new key resources such as AI/ML tools, capturing big data as a key resource for the enterprise, and reskilling the human capital base to be multi-skilled resources (for example, individuals with commercial, business, and technology acumen). They are also automating the business logic of key business activities and adding business intelligence as a key business activity for decision support. These SMMEs are further reconfiguring their key partnerships to leverage SM for reduced delivery and lead times. By reconfiguring their key partnerships, adding key resources, and renewing key business activities, the high-tech SMMEs can leverage SM to realize a flexible, adaptable, and scalable cost structure. This cost structure is responsive to market uncertainty, has a very low capital expenditure (Capex) and operational expenditure (Opex), and minimizes labor-intensive activities. A flexible, adaptable, and scalable cost structure enables the high-tech SMMEs to seamlessly diversify revenue streams, models, and income by efficiently accessing new markets and customer segments.

In contrast, the non-high-tech SMME does not know how to innovate (change or adapt) its traditional business models to strategically fit SM into its businesses for competitiveness and sustainability, as shown in Appendix C – Fig. C.13. The non-high-tech SMME does not understand the relative advantage (benefits) of SM or how to use it to create value for the firm, capture value for the firm, and offer (propose) value to customers.

It is, therefore, proposed that:

Proposition 2 (P2): There is a positive relationship between SMKC and SMRA.

Proposition 3 (P3): There is a positive relationship between BMI and SMRA.

A broad-scale, full implementation of any innovation requires a firm to test, use, and confirm the relative advantage of the innovation in alignment with the strategic objectives and goals of the organization. Long-term strategic investments, such as infrastructure, skills, and technologies need to be made to assimilate the innovation. These strategic investments must be made proactively, taking high risks in anticipation of future business growth. Thus, SMME SMC can only be achieved when SMMEs comprehensively understand the relative advantage of SM (SMRA), perceive it as outweighing the risks and costs of adoption, and proactively make long-term high-risk investments in anticipation of future growth (EO).

The high-tech SMMEs comprehensively understand SMRA and have high levels of EO, as shown in Appendix C – Fig. C.12. The non-high-tech SMME does not understand or know SMRA and has a very low level of EO, as shown in Appendix C – Fig. C.13.

It is therefore proposed that:

Proposition 4 (P4): There is a positive relationship between SMRA and SMC.

Proposition 5 (P5): There is a positive relationship between EO and SMC.

To be ready for SM adoption (SMMERA), an SMME must reach an expert level (level 1) of readiness for SM adoption (Mittal et al., 2018a; Mittal et al., 2018b; Mittal et al., 2018c). At the expert level (level 1), the SMME is fully compatible with SM (SMC). This means that the SMME has begun experimenting with SM ADTs, has some successful SM pilot projects, and has started to strategically deploy some SM ADTs within the enterprise (Mittal et al., 2018a; Mittal et al., 2018b; Mittal et al., 2018c).

In this study, Mittal et al.’s (2018c) guideline was utilized to assess the level of SMME readiness for SM adoption, as illustrated in Appendix D – Table D.1, addressing RQ1. The high-tech SMMEs are at an intermediate level of readiness for SM adoption (SMMERA), only one step away from level 1 (expert level). These SMMEs have developed a pipeline of projects to initiate SM implementation, have invested sufficient time, effort, and resources in practicing the SM paradigm, and developed new SM capabilities. In contrast, the non-high-tech SMME is at a novice level (level 0) of readiness for SM adoption (SMMERA), which is the lowest level of SM readiness. The SMME does not have any SM pipeline projects, has not invested time, effort, or resources in SM, and has not developed any SM capabilities. Moreover, the non-high-tech SMME is neither ready nor willing to invest in the SM paradigm.

It is, therefore, proposed that:

Proposition 6 (P6): There is a positive relationship between SMC and SMMERA.