Fostering rural e-commerce entrepreneurial vibrancy is crucial for achieving regional economic transformation and sustainable development. However, existing research has predominantly examined the net effects of individual factors, overlooking the diverse pathways and complex causal mechanisms that shape high levels of entrepreneurial activity. Integrating entrepreneurial ecosystem theory with a configurational perspective, this study proposes an analytical framework that incorporates resource, social, and institutional elements. Using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis on 28 provincial-level administrative regions in China, the study identifies three equifinal pathways to high rural e-commerce entrepreneurial vibrancy: the endogenous factor-driven path, a formal institution-driven path, and a multi-source support-compensatory path. An in-depth analysis of the underlying mechanisms reveals that these pathways correspond to the logics of opportunity leveraging, opportunity building, and institution empowering, respectively. A cross-configurational comparison further identifies two higher-order driving logics: opportunity anchoring and institution anchoring. By moving beyond traditional linear assumptions, our findings highlight the configurational effects that drive rural entrepreneurship, including the substitutional and complementary relationships among constituent elements. These insights not only provide policymakers with a foundation for developing precise, context-specific strategies that transcend "one-size-fits-all" approaches but also offer a novel theoretical perspective on how less-developed regions can achieve endogenous development through diverse combinations of resource endowments.

Against the backdrop of global digital transformation and balanced regional development strategies, rural e-commerce is widely regarded as a key engine for stimulating endogenous rural dynamics and fostering sustainable economic development (Li & Qin, 2022; Huang et al., 2023; Ye et al., 2024; Song et al., 2024a). A substantial body of research has demonstrated its significant potential in industrial upgrading, poverty alleviation, income growth, and bridging the urban–rural divide (Leong et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2025). However, despite widespread policy support and expanding market opportunities, the development of rural e-commerce entrepreneurship exhibits pronounced regional heterogeneity: while some regions demonstrate vibrant entrepreneurial activity, others yield minimal results or even face stagnation (Zang et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2024). This disparity poses a central question: in rural contexts constrained by resources and institutions, what mechanisms drive high levels of entrepreneurial vibrancy? Attributing this phenomenon to the influence of any single factor is inadequate to explain its complex reality (Wallis, 2009; Huang et al., 2023). Therefore, investigating the specific configurations of antecedent conditions that lead to high rural e-commerce entrepreneurial vibrancy (REEV) is crucial for deepening our understanding of rural entrepreneurship and informing effective policy design.

The extant literature offers multiple theoretical perspectives for understanding rural e-commerce entrepreneurship. Scholars drawing on institutional theory emphasize the critical role of formal institutional arrangements, such as government policies and regulations (Cui et al., 2017; Su, 2021), whereas others highlight the influence of informal institutions such as family support (Soluk et al., 2021). From the resource-based view, the availability of physical and financial resources is considered a fundamental prerequisite for new venture creation (Mei et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2023; Song et al., 2024a). Social network theory, in contrast, centers on social capital, positing that role modeling by elites and knowledge sharing can effectively compensate for entrepreneurs' deficiencies in experience and skills (Mei et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Some scholars even argue that social capital may be a prerequisite for entrepreneurship in certain contexts (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006; Hertel et al., 2021). While these studies have each illuminated important drivers of rural e-commerce entrepreneurship, the fragmentation of these perspectives has led to two key limitations. First, the findings are often divergent or even contradictory. For instance, in assessing the role of government intervention, some studies view it as essential support (Cui et al., 2017), while others suggest it may stifle organic market dynamism. These inconsistencies indicate that the influence of any single factor is likely context-dependent and contingent upon its interactions with other elements. Second, the current research lacks a systemic framework capable of explaining how entrepreneurial activities emerge and thrive in rural settings characterized by deficits in resources, institutions, and social support. It remains unclear how breakthroughs occur through the synergistic interplay of multiple factors.

Moreover, the methodologies employed in prior research suffer from significant limitations. Past studies have predominantly relied on analytical approaches grounded in net-effect logic, such as linear regression and structural equation modeling (Li & Qin, 2022; Huang et al., 2022; Song et al., 2024a). These methods seek to isolate the independent contribution of each variable to an outcome, operating under the core assumption that antecedent conditions function independently of one another. However, from the perspective of complexity theory, socioeconomic phenomena such as entrepreneurship are classic examples of complex adaptive systems, where outcomes emerge from the non-linear interplay of multiple, interdependent factors (Wallis, 2009). Consequently, traditional linear paradigms overlook the synergistic and substitutional relationships among factors and fail to address critical questions—such as whether alternative configurations of conditions can yield equally successful outcomes in the absence of a particular favorable condition (Furnari et al., 2021). These theoretical and methodological limitations hinder a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms that drive REEV.

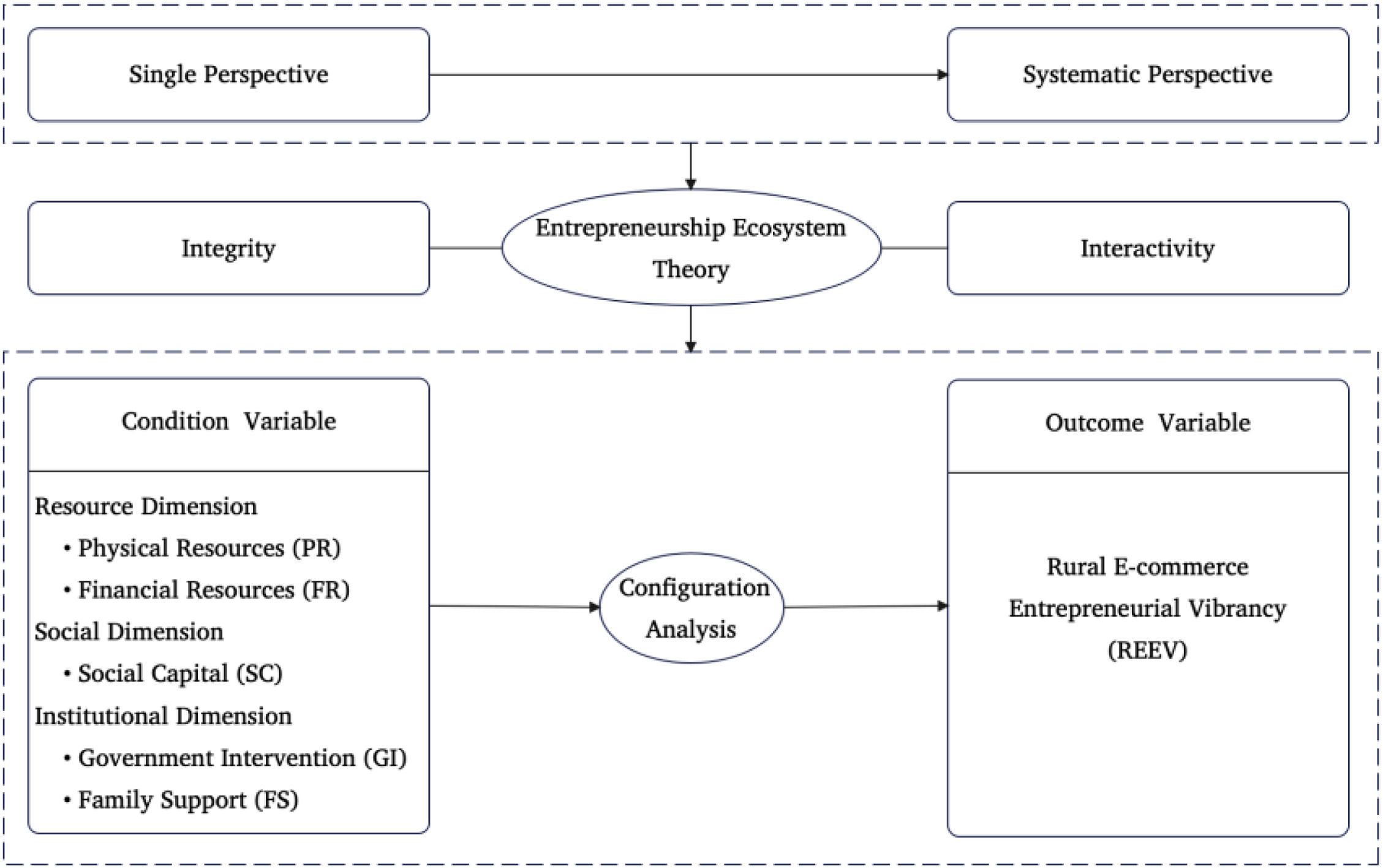

To address these challenges, this study introduces entrepreneurial ecosystem theory as a systemic analytical framework and adopts a configurational perspective. Entrepreneurial ecosystem theory posits that entrepreneurial activity arises not from the isolated effects of individual factors but from the interaction and co-evolution of multiple actors and environmental elements within a region (Stam & van de Ven, 2021). This systemic perspective aligns closely with the configurational approach, which holds that outcomes are shaped by specific combinations of antecedent conditions rather than by single variables (Hertel et al., 2019). Accordingly, this study utilizes a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design centered on fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) (Mitzinneck et al., 2024). We integrate five key conditions into a unified analytical framework, spanning the resource dimension (physical resources, financial resources), the social dimension (social capital), and the institutional dimension (government intervention, family support). This research aims to address the following core questions:

RQ1: What configurational paths of antecedent conditions lead to high REEV?

RQ2: Within these successful configurations, what are the core and peripheral conditions?

RQ3: Do substitutional or complementary relationships exist among the different conditions, thereby offering multiple pathways to achieving high entrepreneurial vibrancy?

This study aims to contribute to both theory and practice in the following ways: Theoretically, it advances the literature in three primary areas. First, by introducing the entrepreneurial ecosystem as a systemic framework, it moves beyond the fragmented, single-dimensional perspectives of prior research and offers a holistic explanation of the systemic mechanisms that drive rural e-commerce entrepreneurship. Second, this study applies configurational theory and methods to the context of rural e-commerce in China. In doing so, it responds to the growing call within entrepreneurship research to adopt a complexity perspective for investigating causal complexity, thereby enriching the understanding of entrepreneurial phenomena as outcomes of multiple conjunctural causation. Third, at a methodological level, the study demonstrates the unique advantages of fsQCA in identifying equifinal pathways to successful outcomes and uncovering their underlying mechanisms, thus providing a rigorous methodological reference for future research in this domain. Practically, the findings reveal multiple pathways for fostering REEV, offering policymakers guidance for designing targeted and adaptive support strategies that align with the specific resource endowments and developmental stages of different regions. This provides a stronger basis for implementing rural revitalization policies more effectively.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and elaborates on the theoretical foundation of this study. Section 3 details the research methodology, including the research design, sample, data, and analytical methods. Section 4 presents the analysis results. Section 5 discusses the key findings, theoretical contributions, practical implications, limitations, and directions for future research. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

Theoretical background and model constructionConceptualizing rural E-commerce entrepreneurship and its vibrancyEntrepreneurship is not only a driver of economic growth but also a pivotal force for social transformation (Mitzinneck et al., 2024). Rural E-commerce Entrepreneurship (REE) has emerged as a significant phenomenon, garnering considerable attention for its ability to transcend the spatio-temporal constraints of traditional rural markets through the use of digital technologies (Huang et al., 2023). This study defines REE as the entrepreneurial process through which rural actors leverage digital tools—such as e-commerce platforms, social media, and live-streaming technologies—to conduct commercial activities (Duan et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023). These activities are deeply embedded in the local context and aim to generate both economic and social value for the region (Li & Qin, 2022).

Compared with traditional entrepreneurship, which typically requires physical storefronts and substantial upfront investment, REE exhibits distinct characteristics. First, it demonstrates a stronger dependence on elements within the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem, including supportive government policies and local social networks (Lin & Tao, 2024). Second, it is characterized by three core features—low cost, high flexibility, and deep local embeddedness—which collectively lower barriers to entry and contribute to a diffusion effect (Zang et al., 2023). Through mechanisms such as demonstration learning, knowledge spillovers, and resource sharing, this diffusion effect enhances potential entrepreneurs’ perception of opportunities and encourages broader participation. Such widespread engagement not only expands the scale of entrepreneurship but also stimulates model innovation, evidenced by the rise of live-streaming e-commerce (Duan et al., 2023), and promotes the clustered development of local specialty industries (Chu et al., 2025).

The inherent local embeddedness of REE ensures that entrepreneurial activities remain closely aligned with local resources, cultural contexts, and community needs (Vestrum et al., 2017). This alignment enables REE to respond precisely to urgent rural needs, such as income generation and employment expansion (Song et al., 2024b; Zhang et al., 2025). As the digital economy increasingly permeates rural areas, REE has become a key driver of comprehensive rural revitalization (Huang et al., 2024). Given its demonstrated value in alleviating poverty (Zhang et al., 2025), improving employment (Song et al., 2024b), and enhancing living standards (Naminse et al., 2019), this study positions REE as a core phenomenon, underscoring its significant practical relevance.

Disparities in resource endowments, social structures, and institutional environments across China's regions have led to significant variations in the breadth of diffusion and depth of embeddedness of rural e-commerce activities. These disparities ultimately manifest as differences in REEV across regions. Broadly defined, entrepreneurial vibrancy refers to the frequency, intensity, and diversity of new venture creation, development, and related activities within a specific region (Acs et al., 2017; Cullen et al., 2014). This study conceptualizes REEV as a multidimensional and dynamic construct that captures the overall extent to which diverse rural entrepreneurial actors leverage digital technologies to generate commercial value within a given geographic and temporal context. It is reflected not only in breadth indicators—such as the quantity and frequency of entrepreneurial activities—but also in depth indicators, including entrepreneurial quality, innovation, and sustainability. Furthermore, entrepreneurial vibrancy is shaped by the complex interplay of multiple antecedent conditions, such as regional characteristics and policy support (Zhou et al., 2021; Zang et al., 2023).

In the context of Chinese rural e-commerce, high levels of entrepreneurial activity have given rise to "Taobao Villages," a landmark phenomenon in economic geography (Yong, 2022; Chu et al., 2025). According to the quantitative criteria established by AliResearch, a "Taobao Village" must meet three standards: (1) business operations are located in a rural area; (2) annual e-commerce sales reach or exceed 10 million RMB (approximately 1.4 million USD); and (3) the number of active online stores totals at least 100 or accounts for 10 % or more of registered households (Chu et al., 2025). These criteria directly reflect the scale, concentration, and vitality of e-commerce entrepreneurship at the village level. Scholars widely regard "Taobao Villages" as exemplary cases of the deep integration between endogenous rural development dynamics and digital empowerment, representing a clear manifestation of high REEV (Lin & Tao, 2024). Therefore, the formation and proliferation of "Taobao Villages" provide this study with a measurable and observable proxy for identifying regions that have achieved high levels of entrepreneurial vibrancy.

Theoretical foundationEntrepreneurial ecosystem theoryA review of the literature reveals that previous studies have predominantly explored the factors influencing rural e-commerce entrepreneurship from single-dimensional perspectives, offering valuable but fragmented insights into the phenomenon (Hu et al., 2023; Song et al., 2024a). However, the findings arising from these single-dimensional approaches are often divergent and even contradictory. For instance, institutional perspectives emphasize that formal institutional arrangements—such as supportive government policies and regulations—are essential conditions for rural e-commerce entrepreneurship (Cui et al., 2017; Su, 2021). In contrast, the social network perspective focuses on informal support, positing that family support (Soluk et al., 2021) and social capital derived from local elites and entrepreneurial role models (Mei et al., 2020) foster entrepreneurship by facilitating knowledge sharing and demonstration effects (Li et al., 2021). Meanwhile, research grounded in the resource-based view argues that physical resources (e.g., agricultural land, infrastructure) (Mei et al., 2020; Miles & Morrison, 2020; Song et al., 2024a) and financial resources (Huang et al., 2023) are fundamental prerequisites for initiating rural e-commerce ventures. Consequently, no consensus has been reached on which type of support (e.g., formal versus informal) or which resource (physical resources versus social capital) plays the most central role in rural entrepreneurship (Cui et al., 2017).

Given this lack of consensus, a single-dimensional research paradigm is insufficient to systematically explain how entrepreneurial activities emerge and thrive through the synergy of multiple factors in rural areas, which are often characterized by resource scarcity and underdeveloped institutional environments (Huang et al., 2023). Accordingly, this study argues that understanding the mechanisms underlying REEV requires shifting from a single-factor lens to a systematic and integrative perspective (Huang et al., 2024, 2023).

The entrepreneurial ecosystem theory offers a valuable theoretical framework for this study. Its origins can be traced to ecological systems thinking, first applied to human development by Bronfenbrenner (1979), and it has since evolved into a core perspective in entrepreneurship research. The theory’s central premise is that entrepreneurial activity does not occur in isolation but is embedded within a complex network of diverse actors, resources, institutions, and cultural elements (Isenberg, 2011). Scholars commonly define an entrepreneurial ecosystem as a complex adaptive system that fosters new venture creation and growth, comprising dynamically evolving and interconnected components such as policy, finance, markets, culture, human capital, and support networks (Isenberg, 2011; Stam, 2015). Following this logic, this study argues that a region's REEV is shaped not only by any single factor but by the synergistic interaction of multiple ecosystem elements.

Empirical research has confirmed that a well-functioning entrepreneurial ecosystem can effectively promote entrepreneurial activity and regional value creation (Stam & van de Ven, 2021a). Within such ecosystems, the coordinated interaction among government actors, support organizations, and resource providers enhances entrepreneurs' ability to access critical resources (Spigel & Harrison, 2018), thereby contributing to broader socioeconomic goals such as regional economic growth (Audretsch et al., 2019). A core tenet of this theory is that a cohesive socioeconomic system can provide sustained support for the emergence and growth of new ventures (Spigel, 2017). This suggests that a rural ecosystem comprising diverse elements from multiple sources can enhance both the quantity and quality of entrepreneurial activities, ultimately strengthening REEV.

In summary, given the explanatory power of entrepreneurial ecosystem theory in regional entrepreneurship research (Wurth et al., 2022), this study adopts it as the core analytical framework to identify the configurational pathways that drive REEV. Rural e-commerce entrepreneurship is influenced by the complex interplay of multidimensional factors. Traditional linear research paradigms, which focus on the net effects of individual variables, are ill-equipped to capture the concurrent synergies and substitution effects that characterize this phenomenon. As a result, they fail to fully reveal the underlying mechanisms at play (Huang et al., 2024, 2023). In contrast, the holistic, interactive, and configurational orientation of entrepreneurial ecosystem theory provides the theoretical foundation needed to address this complexity, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional linear approaches (Isenberg, 2011).

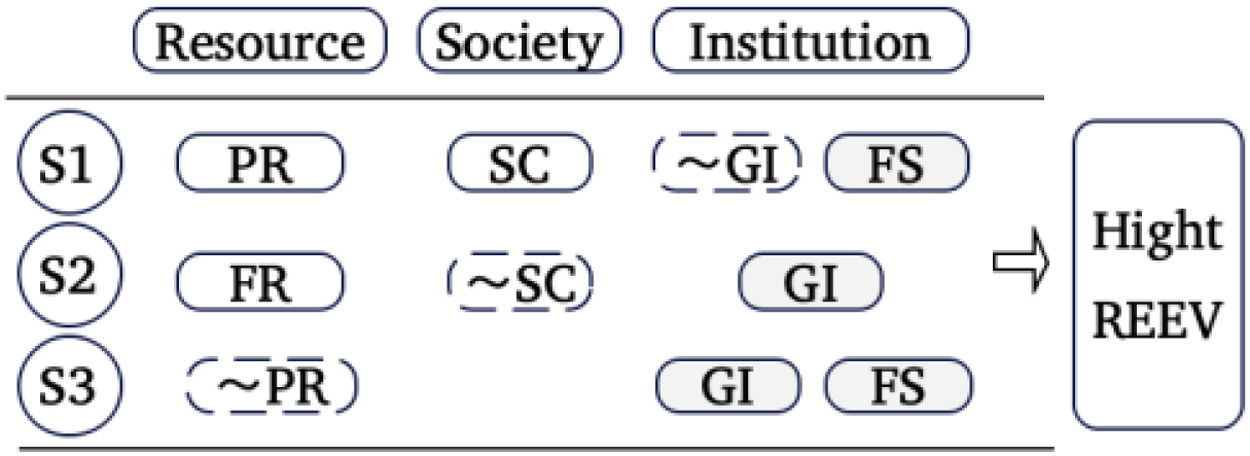

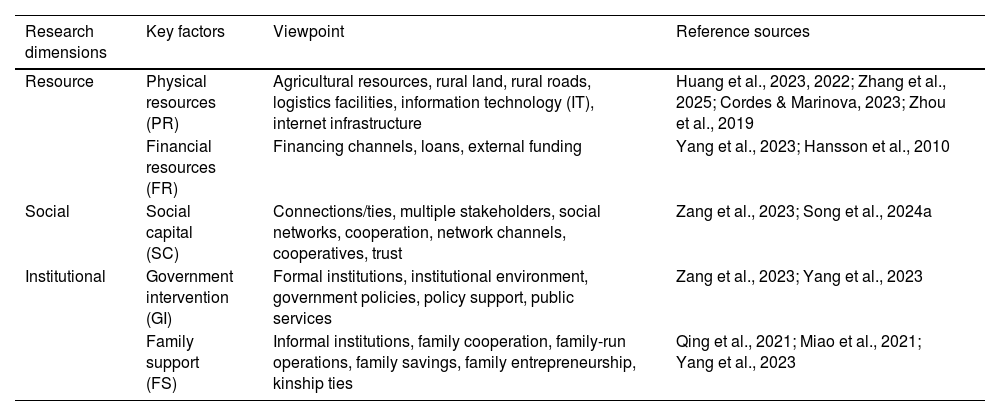

Systemic factors and rural e-commerce entrepreneurial vibrancyAs discussed above, rural e-commerce entrepreneurship is influenced by three core dimensions: resources, social context, and institutional frameworks (Cui et al., 2017; Su, 2021; Mei et al., 2020; Miles & Morrison, 2020; Song et al., 2024a; Huang et al., 2023). We posit that these three dimensions collectively constitute the configurations of key antecedent conditions that influence regional entrepreneurial activity. Specifically, this study systematically investigates the combined effects of five factors on REEV: physical resources, financial resources, social capital, government intervention, and family support (as detailed in Table 1). The selection of these factors aligns with the core tenets of entrepreneurial ecosystem theory, offering a robust theoretical foundation for adopting a configurational approach to understanding how these elements interact to drive entrepreneurial vibrancy.

An analytical framework for rural e-commerce entrepreneurial vibrancy.

| Research dimensions | Key factors | Viewpoint | Reference sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource | Physical resources (PR) | Agricultural resources, rural land, rural roads, logistics facilities, information technology (IT), internet infrastructure | Huang et al., 2023, 2022; Zhang et al., 2025; Cordes & Marinova, 2023; Zhou et al., 2019 |

| Financial resources (FR) | Financing channels, loans, external funding | Yang et al., 2023; Hansson et al., 2010 | |

| Social | Social capital (SC) | Connections/ties, multiple stakeholders, social networks, cooperation, network channels, cooperatives, trust | Zang et al., 2023; Song et al., 2024a |

| Institutional | Government intervention (GI) | Formal institutions, institutional environment, government policies, policy support, public services | Zang et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023 |

| Family support (FS) | Informal institutions, family cooperation, family-run operations, family savings, family entrepreneurship, kinship ties | Qing et al., 2021; Miao et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2023 |

Physical and financial resources are fundamental inputs to entrepreneurial activity, directly corresponding to the "physical infrastructure" and "financial capital" components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem theory. In rural areas, accessible infrastructure, such as efficient logistics systems and reliable digital networks, along with the availability of start-up capital, is essential for launching and sustaining e-commerce ventures. As an economic activity highly dependent on external linkages, rural e-commerce entrepreneurship also relies on entrepreneurs’ ability to identify opportunities and integrate resources to capitalize on them (Huang et al., 2023). A regional deficit in key resources or a lack of commercial foundations can significantly constrain the breadth and depth of rural e-commerce entrepreneurial development (Zhang et al., 2025).

(1) Physical resources (PR)

Physical resources provide the foundational basis for the local embeddedness of rural e-commerce entrepreneurship. They are reflected primarily in local resource endowments—such as distinctive agricultural products, natural scenery, or cultural heritage—which serve as sources of differentiated competitive advantages and unique value propositions (Yang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2025). Physical resources also encompass the infrastructural conditions necessary for e-commerce operations. Well-developed transportation networks and stable digital infrastructure (e.g., high-speed internet, data centers) are prerequisites for rural e-commerce to connect with external markets, conduct online transactions, and manage supply chains (Haugh, 2021; Philip & Williams, 2019).

However, the abundance of physical resources does not automatically translate into entrepreneurial vibrancy. In resource-scarce regions, entrepreneurs may creatively leverage limited conditions through resource bricolage (Huang et al., 2023). Conversely, even in areas with strong infrastructure, e-commerce development may be limited if distinctive products are lacking. Emerging business formats such as livestreaming e-commerce exemplify this interplay: they require a combination of physical resources—“a smooth network (infrastructure) + stable product supply (local endowments) + rapid logistics (infrastructure)" (Duan et al., 2023).

(2) Financial resources (FR)

Financial resources are a key driver of venture creation, growth, and sustained competitiveness (Soto-Simeone et al., 2020), and rural e-commerce ventures are particularly dependent on them (Huang et al., 2023). Financial capital is needed to build online channels, conduct digital marketing, assemble professional teams, maintain operational liquidity, and invest in product and technological upgrades.

Rural entrepreneurs, however, face unique challenges in securing financial resources. Agriculture-related projects often require substantial initial investment (Yang et al., 2023), yet rural micro and small enterprises are frequently excluded from the traditional financial system due to their small scale, lack of collateral, and non-standardized financial practices (Yang et al., 2023). This "financing gap" opens the possibility that financial resources may be substituted by other factors. For instance, when formal financial channels are constrained, substantial government subsidies, microcredit programs, or informal local financing (such as private lending or mutual aid funds) may serve as effective alternative pathways (Block et al., 2021). Gompers et al. (2010) noted that financial capital plays a vital role throughout a venture’s lifecycle, particularly during the start-up phase. Therefore, a robust financial system is crucial for providing the necessary capital required to support the development of rural e-commerce entrepreneurship.

Antecedent conditions: the social dimensionSocial capital aligns closely with the emphasis in entrepreneurial ecosystem theory on networks and entrepreneurial culture. In relationship-based rural societies, characterized by information asymmetry and underdeveloped market mechanisms, social networks grounded in trust and reciprocity serve as crucial channels through which entrepreneurs gain access to information, experience, and tacit knowledge (Song et al., 2024b).

As a key condition influencing REEV (Song et al., 2024b), social capital stimulates entrepreneurial activity by reducing transaction costs and uncertainty (Putnam, 2000). Specifically, social capital provides entrepreneurs with network channels for sourcing and integrating resources.

First, dense community networks rooted in kinship and locality foster collective action (Putnam, 1993). By establishing connections with entrepreneurial leaders or influential village actors (bridging social capital), entrepreneurs can access heterogeneous information, external market channels, and potential capital (Zang et al., 2023), thereby overcoming constraints related to limited market power and resource endowments (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Vedula & Frid, 2019).

Second, in the virtual e-commerce marketplace, new entrants typically face the liability of newness due to a lack of reputation. Trust relationships embedded in offline communities can be extended to online transactions, providing nascent e-commerce ventures with initial credibility and significantly lowering the transaction costs associated with acquiring early customers (Zhang et al., 2025). This trust-based environment, rooted in norms of reciprocity, serves as a core for maintaining stable transactions and enabling the efficient flow of resources within the rural e-commerce ecosystem (Kleinhempel et al., 2022).

Finally, within these tightly knit community networks, the success of established e-commerce entrepreneurs not only inspires imitative start-ups through demonstration effects (i.e., “herd effects”) (Mei et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021) but, more importantly, also cultivates a shared belief in the feasibility of entrepreneurship. This collective narrative lowers the cognitive barriers for potential entrepreneurs. Concurrently, tacit knowledge related to platform operations, live-streaming techniques, and customer relationship management diffuses efficiently through informal communication channels (Song et al., 2024b). This diffusion substantially reduces the learning curve for new entrants, thereby enhancing both the breadth and depth of e-commerce entrepreneurship in the region.

Antecedent conditions: the institutional dimensionThe institutional environment is a pivotal force in shaping entrepreneurial activity, helping to alleviate the resource constraints faced by rural e-commerce entrepreneurs, especially in the early stages of venture development (Leong et al., 2016). This study focuses on two core institutional conditions: government intervention, representing formal institutions, and family support, serving as a critical informal complement.

(1) Government intervention (GI)

Government intervention refers to the influence exerted on economic activities through policies, resource allocation, and regulatory frameworks (Ahi et al., 2023; Martinez-Bravo et al., 2022). Its impact on REEV is multifaceted. First, it directly reduces entrepreneurial barriers and costs through fiscal subsidies, tax incentives, and streamlined administrative procedures, thereby stimulating participation in entrepreneurial activities (Mei et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023). Second, it drives the development of essential infrastructure—such as broadband networks and logistics centers—providing the public goods necessary for e-commerce operations (Zhang et al., 2025). Finally, through industry regulations and official endorsements, government intervention grants legitimacy and establishes a stable market order for rural e-commerce, safeguarding its sustainable development (McKague & Oliver, 2012; Cordes & Marinova, 2023; Yang & Liu, 2021).

However, the literature offers no consensus on the overall effect of government intervention. On the one hand, proactive government support can provide social entrepreneurs and social enterprises with substantial resources and opportunities, helping them secure institutional legitimacy and enhancing regional entrepreneurial vibrancy (Stephan et al., 2015). Policy support can alleviate resource bottlenecks, such as funding constraints, that hinder entrepreneurial activities (Lim et al., 2016), and government bureaucratic behavior can influence entrepreneurs’ capacity to engage in venture creation (Chen et al., 2021; Du et al., 2023; Weber et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2024). On the other hand, some scholars argue that strong government intervention can have inhibitory effects by crowding out entrepreneurial initiative and reducing the perceived need for social enterprise activity (Hoogendoorn, 2016). These divergent perspectives may stem from oversimplifying the causal complexity that characterizes the relationship between government action and entrepreneurial dynamics.

(2) Family support (FS)

In rural contexts, family support functions as a critical informal institutional arrangement embedded within the entrepreneurial process. It transcends individual-level action and complements the formal institutional environment (Khavul et al., 2009; Sambharya & Musteen, 2014). As the fundamental organizational unit of rural society, the family's resources and roles permeate all stages of entrepreneurship. Its influence can be understood through three interconnected dimensions: resource provision, cognitive and emotional empowerment, and legitimacy building (Miller et al., 2015; Adjei et al., 2019; Soluk et al., 2021).

First, in rural areas characterized by underdeveloped capital and labor markets, start-up ventures often face severe financial and human resource bottlenecks. Families help address these constraints by providing tangible assets—such as initial capital and storage space—as well as low-cost labor, thereby securing the venture's basic operational needs. Second, families offer entrepreneurs vital cognitive and emotional support. Emotional reassurance and moral encouragement can enhance entrepreneurs’ psychological resilience, while family members’ deep knowledge of local culture and markets provides valuable insights for decision-making, improving the venture’s adaptability (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Third, family support helps activate kinship-based and locality-based social networks, enabling new online stores to secure early orders rooted in trust—an essential mechanism for overcoming the liability of newness and establishing initial market credibility (Aldrich & Auster, 1986). Moreover, intergenerational knowledge complementarity within families can compensate for capability gaps, reducing challenges associated with insufficient legitimacy (Khavul et al., 2009; Gümüsay & Smets, 2020).

Admittedly, family support carries a "double-edged sword" effect: excessive involvement may lead to conservative decision-making, stifled innovation, or internal conflict (Schulze et al., 2001). Nonetheless, in the nascent stages of rural entrepreneurship, characterized by resource scarcity and weak trust mechanisms, the positive, empowering effects of family support as an informal institution typically outweigh its potential drawbacks.

Model constructionThe preceding discussion has identified the antecedent conditions that potentially influence REEV. Prior research has often overlooked the complex, conjunctural effects through which these conditions interact to shape entrepreneurial vibrancy, hindering deeper exploration of the underlying causal mechanisms (Furnari et al., 2021) and contributing to inconsistent findings in the literature (Kiss et al., 2012; Lim et al., 2016). Recent studies have begun to acknowledge the interdependencies among these antecedent conditions. For instance, social capital, as a critical relational resource, can significantly moderate an entrepreneur's ability to efficiently acquire other resources (Mitzinneck et al., 2024). Robust social networks not only provide direct material and informational support but also function as a signaling mechanism that enhances the entrepreneur’s legitimacy with governmental bodies and financial institutions. This can, to some extent, substitute for or complement shortfalls in financial resources (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Hertel et al., 2021). Moreover, family support offers a foundational base of trust and initial capital, serving as a cornerstone for entrepreneurs to further leverage their social capital in mobilizing a broader set of resources (Khavul et al., 2009). Concurrently, government-led infrastructure development and public service platforms foster an environment conducive to the formation and effective utilization of social capital. Conversely, entrepreneurs with abundant social capital are more likely to access preferential policy treatment and resource-matching opportunities (Zang et al., 2023).

From the perspective of complexity theory, however, interrelated elements interact in non-linear and dynamic ways, generating emergent behaviors and outcomes that cannot be fully understood by examining individual components in isolation (Wallis, 2009). This implies that even in the absence of sufficient funding, a combination of strong social capital, robust family support, and targeted government intervention can collectively compensate for the lack of external financing (Hertel et al., 2021). This combined effect of "multiple concurrent factors," often conceptualized as a configuration, extends beyond the simple interaction effects examined in traditional linear frameworks. As Stenholm and Renko (2016) argue, the effective combination of resources is more crucial than the sheer quantity of any single resource.

In light of the preceding analysis, this study adopts a configurational perspective to understand the combinations of antecedent conditions that shape REEV. A configurational perspective is a systemic approach that, in contrast to single-variable analyses, emphasizes understanding complex phenomena by examining multiple dimensions of influence and focusing on their interplay and holistic effects (Monat & Gannon, 2015; Arnold & Wade, 2015). This approach aligns with the principles of holism and interactivity central to entrepreneurial ecosystem theory (Stam, 2015; Isenberg, 2011).

Configurational theory posits that social phenomena arise from complex causal logic. Its core tenets include equifinality—where different combinations of factors can lead to the same outcome—and causal complexity—where the effect of a particular condition may vary fundamentally across different configurations (Fiss, 2011). Traditional variable-oriented research paradigms are often ill-equipped to capture such complexity. By contrast, a configurational perspective enables systematic investigation of several key questions: (1) What configurational paths of antecedent conditions lead to high REEV? (2) Within these successful configurations, do certain conditions function as core or peripheral elements? For instance, scholars have suggested that social capital may be a prerequisite for entrepreneurship in specific contexts (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006; Hertel et al., 2021); whether this holds true in the domain of rural e-commerce warrants empirical investigation. (3) Do substitutional or complementary relationships exist among the different factors, thereby offering multiple pathways to achieving high entrepreneurial vibrancy?

To systematically address these questions, this study develops a configurational model of the factors influencing REEV, as shown in Fig. 1.

MethodologyMethodOur core research question seeks to systematically uncover the complex causal pathways and underlying mechanisms that drive high levels of REEV. Rural e-commerce entrepreneurship is inherently complex (Huang et al., 2023): its vibrancy is not determined by any single variable in a linear manner but emerges from the complex interplay among various support conditions, including physical resources, financial resources, social capital, government intervention, and family support (Wallis, 2009). Rather than examining the net effects of isolated variables, this study focuses on how these conditions combine to form distinct causal recipes (Fiss, 2011).

Traditional analytical methods grounded in correlational logic and net-effect assumptions (e.g., multiple regression analysis) are insufficient for explaining phenomena characterized by equifinality and contextual dependence (Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2013; Furnari et al., 2021). Therefore, to capture these configurational effects, this study employs fsQCA as the core analytical method. This approach is well aligned with complexity science and the configurational perspective (Fiss, 2011; Roig-Tierno et al., 2017; Kallmuenzer et al., 2025), enabling systematic analysis of how different configurations of causal conditions are sufficient for achieving high levels of REEV. This approach thus provides a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of complex phenomena (Rihoux & Ragin, 2009; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012; Greckhamer et al., 2018; Bennett et al., 2025). Notably, fsQCA has gained growing prominence in innovation and entrepreneurship research due to its strengths in capturing causal complexity (Douglas et al., 2020; Ding, 2022; Kumar et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2024; Vargas-Zeledon & Lee, 2024; Kallmuenzer et al., 2025).

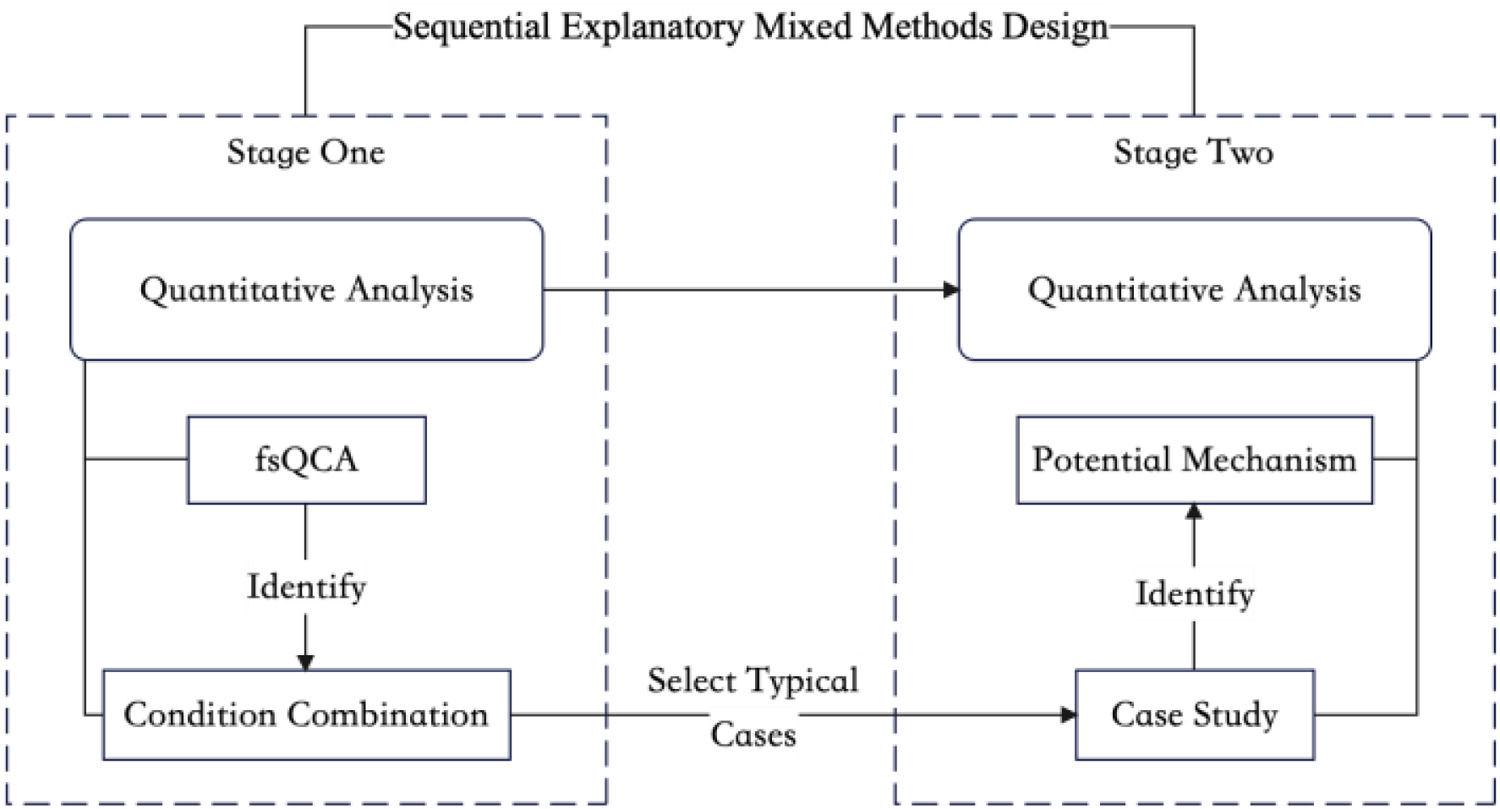

This study also responds to recent calls to advance fsQCA research beyond identifying configurations toward explaining underlying mechanisms (Furnari et al., 2021; Mitzinneck et al., 2024). Traditional fsQCA applications often describe configurations without exploring the mechanisms that produce them (Vargas-Zeledon & Lee, 2024). To address this limitation, we employ an fsQCA-based sequential explanatory mixed methods design (Ivankova, 2014; Modem et al., 2023) (see Fig. 2). This approach integrates the strengths of fsQCA and case study analysis, advancing the broader call for deeper integration of quantitative and qualitative methods (Rihoux, 2009; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012).

- •

Stage 1: Identifying Configurational Paths. We first apply fsQCA, an analytical technique grounded in set theory and Boolean algebra (Ragin, 2008), to identify the multiple, equifinal configurations of conditions that lead to high REEV (Fiss, 2007, 2011). This cross-configurational comparative analysis uncovers substitutional and complementary relationships among conditions (Beynon et al., 2021; Deng et al., 2019).

- •

Stage 2: Uncovering Causal Mechanisms. Building on the configurational results, we select typical cases that exhibit high membership in each core path for in-depth qualitative analysis. This enables us to examine how the constituent conditions interact synergistically to generate high REEV. The primary objective is to identify the causal mechanisms linking antecedent configurations to outcomes, thereby offering a richer and more compelling causal explanation (Greckhamer, 2016).

In summary, this study provides an analytical framework that combines breadth—by identifying multiple pathways—and depth—by revealing underlying mechanisms—to advance the understanding of complex entrepreneurial phenomena. All analyses will be conducted using fs/QCA 3.0 software, following standard procedures for condition calibration, truth table construction, and logical minimization.

Sample and data collectionGiven the significant regional clustering and environmental heterogeneity of rural e-commerce entrepreneurship in China (Zang et al., 2023), this study adopts provincial-level administrative regions as the unit of analysis. This level of analysis not only captures regional disparities effectively but also ensures data availability, reliability, and cross-regional comparability.

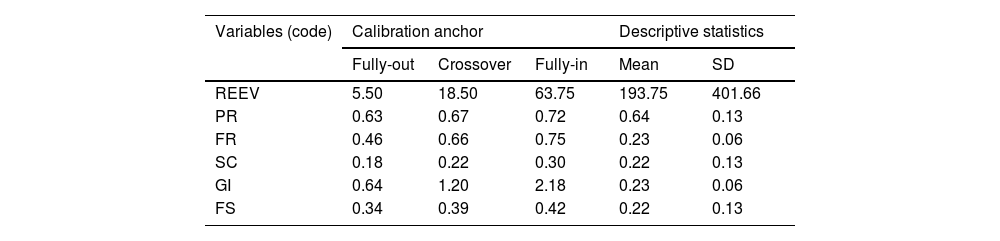

The primary data were obtained from the official database of the National Bureau of Statistics of China and supplemented with data from the "Taobao Village" database published by the AliResearch Institute. To avoid the atypical shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurial activity from 2020 onward, the observation period was confined to 2019–2020. After excluding provinces not covered by the "Taobao Village" statistical system, the final effective sample comprised 28 provincial-level administrative regions. To mitigate potential reverse causality, the measurement of the outcome variable was lagged by one year relative to the antecedent conditions (Gupta et al., 2020). Table 2 presents detailed measurement descriptions and descriptive statistics for all variables.

Variable measurementOutcome variableThe outcome variable, REEV, is measured using the number of “Taobao Villages” within each provincial administrative region as a proxy indicator. This measure is justified for two reasons. First, the official designation of a “Taobao Village” requires meeting stringent criteria for transaction volume and the number of active online merchants (Lin & Tao, 2024). Thus, it reflects not sporadic entrepreneurial behavior but a mature stage of entrepreneurial development characterized by industrial clustering and ecosystem formation (Long et al., 2011). Accordingly, the number of these villages serves as a comprehensive measure of regional entrepreneurial vibrancy. Second, the list is published by an authoritative institution, ensuring clear definitions and high data reliability.

Condition variablesWe analyze the contribution of five antecedent conditions to REEV: (1) physical resources (PR), (2) financial resources (FR), (3) social capital (SC), (4) government intervention (GI), and (5) family support (FS).

PR refer to the tangible assets and infrastructure that shape business opportunities for rural e-commerce ventures. Their availability is critical. Scholars note that agricultural conditions and general infrastructure constitute key physical resources for rural e-commerce development (Zhang et al., 2025). Accordingly, this condition is assessed using three subcomponents: agricultural resource availability, digital infrastructure, and logistics infrastructure.

FR pertain to the ability of nascent rural e-commerce ventures to secure funding from financial institutions (Bailey, 2012). Because substantial capital investment is often required, access to bank loans is vital. We therefore use the scale of regional total social financing to measure this condition.

SC reflects the potential for locally mobilized collective action. Since cooperatives are a core indicator of social capital (Putnam, 2000), this condition is measured using the prevalence of rural e-commerce cooperative organizations.

GI captures the degree of support provided by government agencies to rural e-commerce entrepreneurship. Due to the lack of official data on direct government support for REEV, and given the significant correlation between rural e-commerce and agricultural development, we use public expenditure in agriculture, fisheries, and forestry as a proxy measure.

FS assesses the level of support entrepreneurs receive from their families. Direct data on FS for entrepreneurial activities are limited. However, households with stronger economic capacity are more likely to support entrepreneurial endeavors. Therefore, household operational income is used as a proxy indicator for FS.

Data calibrationBecause fsQCA is grounded in set theory, it is necessary to convert raw data into set membership scores ranging from 0 (fully out) to 1 (fully in). To determine the membership score of each case for each condition, researchers must define qualitative anchors (i.e., fully in, fully out, and the crossover point) based on theoretical and/or empirical justification (Fiss, 2007). When such justification is not feasible, percentile-based direct calibration can be employed (De Crescenzo et al., 2020). Accordingly, this study applies the direct method, using the 75th, 50th, and 25th percentiles of the raw data as the fully in, crossover, and fully out anchors, respectively (see Table 2).

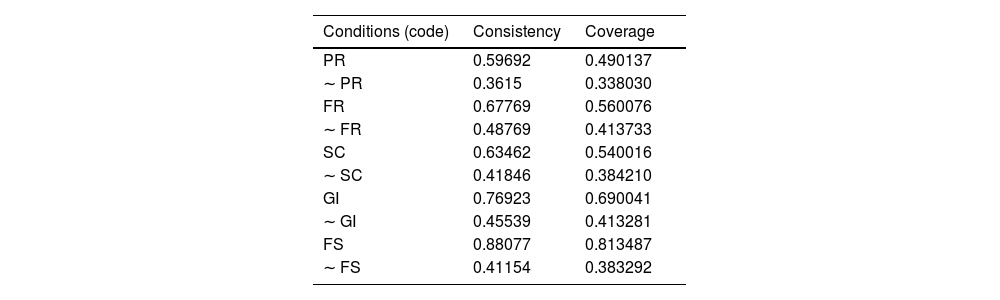

Analysis and resultsAnalysis of necessityFsQCA allows for tests of both sufficiency and necessity (Greckhamer et al., 2018). Accordingly, this study first evaluates whether any single condition is necessary for achieving high REEV. As shown in Table A3, the consistency scores for all individual conditions fall below the conventional 0.90 threshold. This indicates that none of the five antecedent conditions are individually necessary for high REEV.

Analysis of sufficiencyFor the sufficiency analysis, rigorous analytical thresholds were set. The frequency threshold was set at 1 to retain all configurations with at least one observed case. The consistency threshold was set at 0.80, exceeding the commonly accepted 0.75 benchmark (Fiss, 2007). The proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) threshold was set at 0.65, above the recommended 0.50 threshold (Greckhamer et al., 2018).

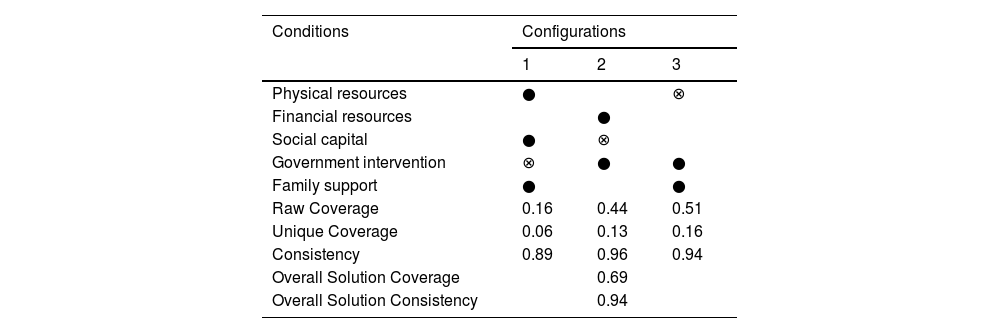

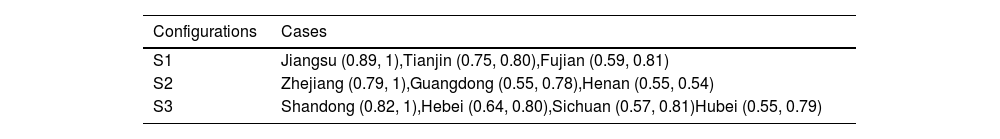

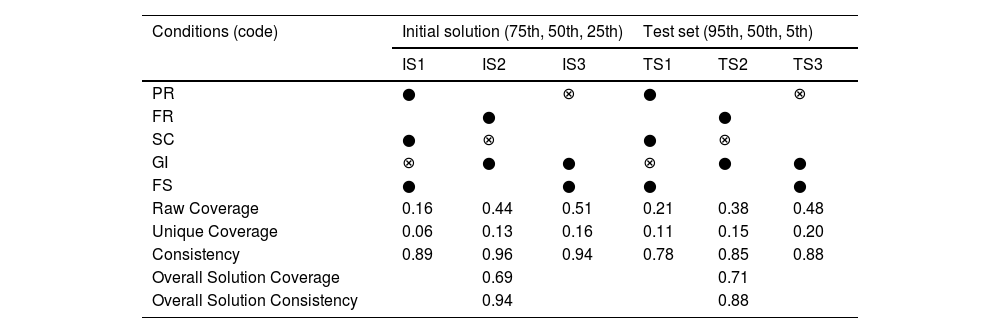

Table 3 presents the sufficient configurations for achieving high REEV. The overall solution consistency is 0.94, well above the established threshold of 0.75 (Greckhamer et al., 2018), indicating that the configurations reliably explain high REEV. The overall solution coverage is 0.69, suggesting that the identified configurations account for a substantial proportion of high-REEV cases. Robustness tests further confirm the stability of the findings (see Table A5). Three distinct configurational pathways were identified and are interpreted below.

(1) Configuration 1: Endogenous factor-driven (PR * SC * ∼GI * FS)

Configurations leading to high rural e-commerce entrepreneurship vibrancy (REEV).

Note. Black circles indicate the presence of a condition, crossed-out circles indicate its absence, and blank spaces indicate "don't care." Large circles indicate core conditions, and small circles denote peripheral conditions (Ragin & Fiss, 2008; Fiss, 2011).

The raw coverage of Configuration 1 (0.16) indicates that this "endogenous factor-driven" pathway accounts for over 16 % of high-REEV cases. This configuration shows that high physical resources, high social capital, and high family support—as core conditions—lead to high REEV even in the absence of strong government intervention. This suggests that when regions possess adequate material resources, robust social networks, and strong family-based support systems, high entrepreneurial vibrancy can emerge organically from market-based and community-driven forces. This represents a development model primarily driven by internal and informal mechanisms.

(2) Configuration 2: Formal institution-driven (FR * ∼SC * GI)

Configuration 2 has a raw coverage of 0.44, accounting for over 44 % of high-REEV cases. This formal institution-driven pathway shows that high financial resources, low social capital, and strong government intervention—as core conditions—can jointly produce high REEV. This configuration reflects a development model in which a supportive financial environment and proactive government policies can compensate for weak social networks. It underscores the substitutability between formal institutional support (e.g., policy incentives, public services, financial capital) and informal mechanisms (i.e., social capital).

(3) Configuration 3: multi-source support-compensatory (∼PR * GI * FS)

The raw coverage of Configuration 3 (0.51) reveals that this "multi-source support-compensatory" path accounts for over 51 % of the cases exhibiting high REEV. This configuration shows that the absence of high material resources, combined with high government intervention and high family-based support as core conditions, leads to high REEV. It highlights a development pathway for regions with relatively weak material foundations. The analysis indicates that even when a region's material resource endowment is insufficient, strong government intervention together with prevalent family support can still foster high levels of REEV. This configuration demonstrates that top-down policy support (GI) and bottom-up informal support (FS) can produce a complementary effect that jointly offsets the constraints imposed by a scarcity of physical resources.

Mechanism analysis: typical cases based on configurationsTo elucidate the causal mechanisms embedded in the configurations, this study conducts a typical case analysis. Following the “typical case” principle (Ragin, 2008), cases were selected based on two criteria: (1) they exhibit high membership scores (approaching 1) in both the target configuration and the outcome, and (2) they are information-rich, enabling in-depth qualitative analysis. The membership scores for all cases are presented in Table A2. To ensure analytical validity, we triangulated evidence from multiple sources, including media reports, official documents, and statistical reports. Accordingly, Shuyang County (Jiangsu Province), Lin'an District (Zhejiang Province), and Cao County (Shandong Province) were selected to represent Configurations 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Key qualitative evidence supporting each mechanism is summarized in Table A1.

Configuration 1: the opportunity leveraging mechanismThe underlying mechanism of Configuration 1 is conceptualized as opportunity leveraging. Qualitative evidence is provided by the case of Shuyang County in Jiangsu Province (see Table A1). This mechanism is rooted in the region's abundant pre-existing physical resources. Shuyang County's long-established floriculture and nursery industry provides local entrepreneurs with readily accessible physical resources that constitute the primary source of entrepreneurial opportunities. However, the mere presence of opportunities is not sufficient; what is critical is the ability of entrepreneurs to identify and exploit them effectively.

High levels of social capital accelerate the diffusion of entrepreneurial skills through demonstration effects and knowledge spillovers generated by successful entrepreneurs. Concurrently, strong family support significantly lowers entry barriers by offering initial resources and serving as a buffer against risk. Together, these factors form an enabling ecosystem that allows entrepreneurs to fully leverage local opportunities.

A defining characteristic of this mechanism is that it functions even in the absence of government intervention (∼Government Intervention), revealing a pattern of "bottom-up" organic growth (Chu et al., 2025). By 2019, Shuyang County's total postal service revenue had reached RMB 1.091 billion (a 108.6 % increase), and the county was home to 45,000 active online retailers and 86 "Taobao Villages." These figures not only illustrate the scale and specialization of the local e-commerce sector but also provide compelling evidence that the opportunity leveraging mechanism has effectively driven high levels of REEV.

Configuration 2: the opportunity building mechanismThe underlying mechanism of Configuration 2 is conceptualized as opportunity building. Qualitative evidence for this mechanism is provided by the case of Lin'an District in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province (see Table A1).

In contrast to the opportunity leveraging mechanism, this mechanism centers on creating new opportunities rather than exploiting existing ones. Its key driver is government-led industrial integration and digital transformation, which systematically generate new business opportunities by proactively cultivating novel fields (e.g., the integration of agriculture and tourism). This process relies heavily on both financial resources and government intervention. First, abundant financial resources provide the foundation for capital-intensive ventures, such as the renovation of rural guesthouses. Second, proactive government intervention—through policy guidance and initial public investment—reduces the risks faced by entrepreneurs entering these emerging sectors. This top-down model also explains the absence of social capital, as the combined influence of government and financial markets substitutes for the functions typically performed by social networks in resource coordination and risk sharing (Chu et al., 2025).

In 2019, rural tourism in Lin'an District attracted 20.72 million visitors (a 57.1 % increase) and generated RMB 2.068 billion in operating revenue (a 62.6 % increase). These figures demonstrate the effectiveness of the opportunity-building mechanism in driving entrepreneurial vibrancy.

Configuration 3: the institution empowering mechanismThe internal mechanism of Configuration 3 is interpreted as institution empowering. Qualitative evidence for this mechanism is illustrated by the case of Cao County in Heze City, Shandong Province (see Table A1).

At the core of this mechanism, formal and informal institutions exhibit strong complementarity, jointly overcoming the region’s dual scarcity of physical and financial resources. On the one hand, informal institutions rooted in the family unit form the endogenous foundation for entrepreneurship. The family workshop model, built on kinship-based trust, significantly reduces transaction costs and alleviates initial start-up challenges through internal division of labor and resource pooling. On the other hand, government intervention, as a key formal institution, addresses scaling bottlenecks that family-based ventures cannot overcome independently. By upgrading infrastructure, providing public services, and injecting external resources, the government mitigates market failures related to logistics, talent shortages, and information asymmetry.

This combination of top-down institutional support and bottom-up endogenous drive generates a powerful synergistic effect, systematically empowering entrepreneurial activities (Zang et al., 2023). Consequently, Cao County achieved rapid development despite its initial resource disadvantages. By 2019, the county hosted 124 "Taobao Villages," over 50,000 online stores, and generated RMB 51.6 billion in e-commerce transactions—clear evidence of the effectiveness of the institution empowering mechanism in driving REEV.

Cross-configurational analysis: driving logics and underlying principleDriving logics: opportunity-anchoring vs. institution-anchoringThe preceding section identified three mechanisms underpinning high REEV. A cross-configurational comparison reveals two distinct driving logics: an opportunity-anchoring logic grounded in market opportunities, and an institution-anchoring logic rooted in the institutional environment.

(1) Opportunity-anchoring

The opportunity-anchoring logic captures the shared characteristics of Configuration 1 (opportunity leveraging) and Configuration 2 (opportunity building). In both cases, regional entrepreneurial activity is organized around a clear and strong market opportunity. In essence, opportunity-anchoring represents an exogenously driven model in which the level of REEV depends directly on the presence of a compelling opportunity and the effective allocation of resources around it (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000).

(2) Institution-anchoring

The driving logic of Configuration 3 differs fundamentally from that of Configurations 1 and 2, exhibiting endogenous characteristics distinct from the opportunity-anchoring model. Here, high REEV does not stem from specific market opportunities but is instead underpinned by a stable and efficient institutional environment—what we refer to as "institution-anchoring." This logic is based on a strong coupling between formal institutions (government intervention) and informal institutions (family support). While informal institutions provide low-cost trust and initial resources, formal institutions confer legitimacy and enable access to external markets. Their synergy creates the foundational conditions for widespread entrepreneurial behavior (North, 1990; Xiong et al., 2024).

Underlying principle: the substitutional effect among conditionsA cross-configuration comparison reveals complex substitution and complementarity effects among elements of the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

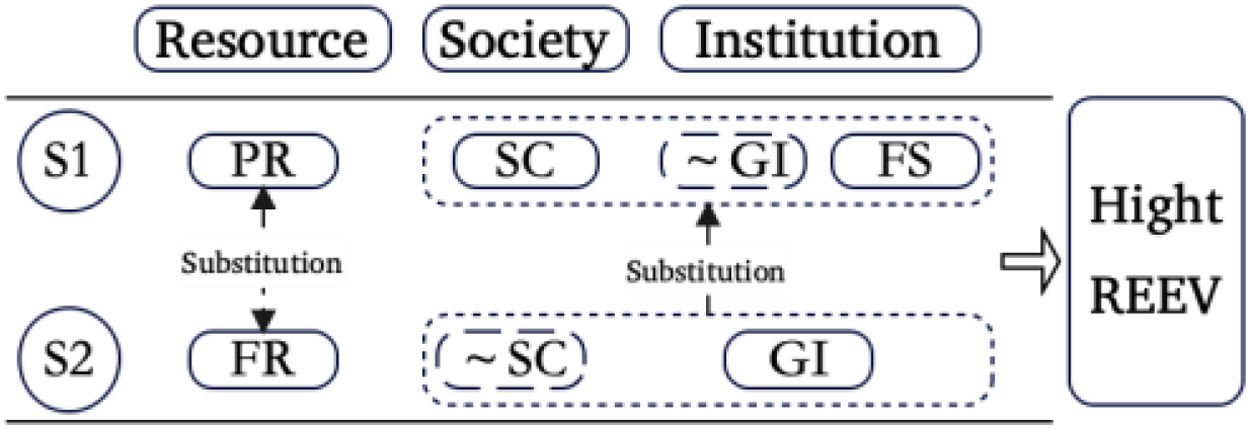

First, comparing Configuration 1 (PR * SC * ∼GI * FS) with Configuration 2 (FR * ∼SC * GI) highlights substitution among elements within the same dimension. In the resource dimension, physical resources (PR) are substituted by financial resources (FR). In the institutional dimension, the combination of family support (FS) and the absence of government intervention (∼GI) is replaced by the presence of strong government intervention (GI). As illustrated in Fig. 3, this suggests that the core resources driving REEV are not static. Entrepreneurs may either leverage existing physical assets or obtain liquid financial capital to launch and expand their ventures. This finding indicates that different resource types must be matched with the appropriate institutional conditions (Bals et al., 2023).

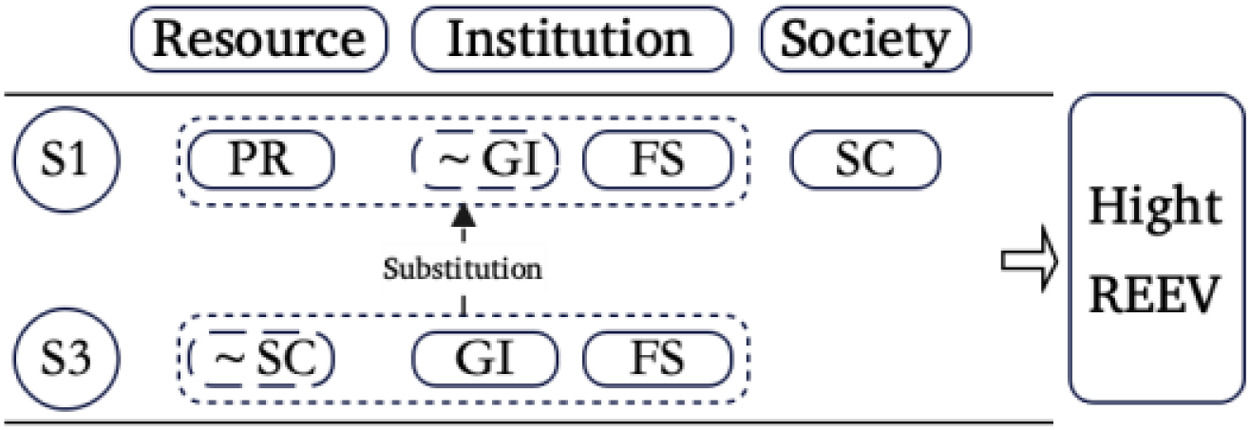

Second, a comparison between Configuration 1 (PR * SC * ∼GI * FS) and Configuration 3 (∼PR * GI * FS) reveals a critical distinction. In Configuration 1, physical resources (PR) function as the core driver, whereas in Configuration 3, which lacks physical resources (∼PR), government intervention (GI) emerges as the core driver (see Fig. 4). This pattern suggests a substitutional effect between market-based endogenous resource endowments and government-led external institutional support. In resource-abundant regions, market mechanisms alone are sufficient to stimulate entrepreneurship. Conversely, in resource-scarce regions, government involvement becomes the essential mechanism for filling this functional void and unlocking entrepreneurial potential (Hoogendoorn, 2016).

Finally, a comparison of Configuration 1 (PR * SC * ∼GI * FS), Configuration 2 (FR * ∼SC * GI), and Configuration 3 (∼PR * GI * FS) reveals that elements from the institutional dimension, specifically government intervention or family support, appear as core conditions in all three. Notably, family support (FS) is a core element in both Configuration 1 and Configuration 3 (see Fig. 5). This suggests that physical resources, financial resources, and social capital must be embedded within appropriate institutional arrangements in order to be effectively activated, thereby underscoring the critical role of institutional factors in rural e-commerce entrepreneurship (Yin et al., 2024).

Robustness checksTo ensure the robustness of our findings, we followed previous studies (Dul et al., 2020; Vargas-Zeledon & Lee, 2024) and conducted an additional series of robustness checks for both the necessity and sufficiency analyses.

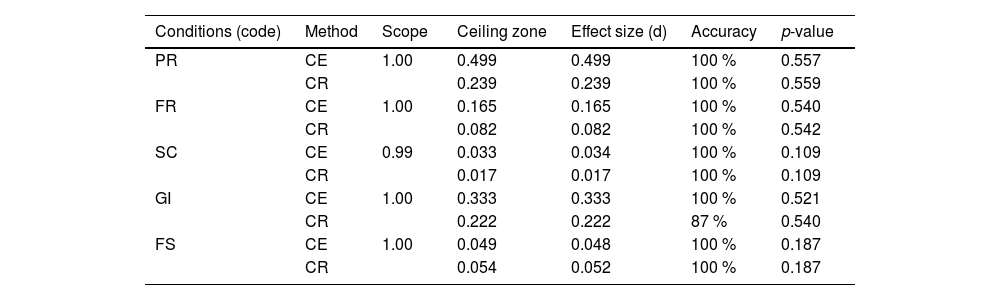

First, we employed necessity condition analysis (NCA) to identify potential necessary conditions. According to NCA criteria, a condition is deemed necessary if its effect size (d) is at least 0.1 and the permutation test yields a significant result (p < 0.05) (Dul et al., 2020). As shown in Table A4, no single condition met these criteria, consistent with the results of our main necessity analysis.

Second, we performed two robustness checks for the sufficiency analysis. In the first check, we adjusted the calibration anchors from the conventional 75th, 50th, and 25th percentiles to the more stringent 95th, 50th, and 5th percentiles. Following Ding (2022), this specification better preserves variation among high-scoring cases and reduces information loss during calibration. In the second check, we repeated the sufficiency analysis using a higher proportional reduction in inconsistency (PRI) threshold (PRI ≥ 0.75 rather than PRI ≥ 0.70 in the main analysis) (Misangyi & Acharya, 2014). As presented in Table A5, the resulting solution configurations remained highly similar to those in the primary analysis.

In summary, these tests collectively confirm the robustness of our findings.

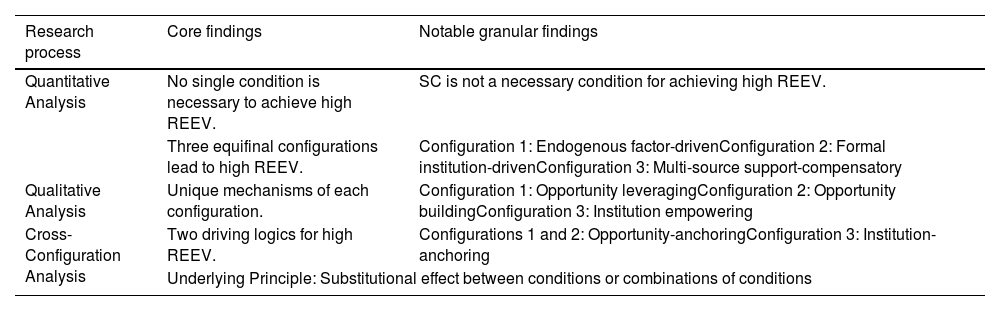

DiscussionThis study investigates the key mechanisms driving REEV in China. Drawing on entrepreneurial ecosystem theory and a configurational perspective, it examines how physical resources, financial resources, social capital, government intervention, and family support jointly shape rural e-commerce entrepreneurship. Employing a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design centered on fsQCA, the study identifies three heterogeneous pathways leading to high REEV (see Table 4). These findings corroborate the principle of equifinality within configurational theory, which posits that different combinations of conditions can generate the same outcome (Schneider & Wagemann, 2012). This research not only contributes new empirical evidence to the understanding of the complexities of rural e-commerce entrepreneurship in China but also offers significant theoretical and practical implications.

Summary of study findings.

First, this study deepens the core propositions of holism and interactivity within entrepreneurial ecosystem theory by applying a configurational perspective. Existing literature predominantly employs a net-effect logic, analyzing individual factors in isolation (Xie et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2022). This approach creates a methodological tension with the systemic, interdependent nature of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Qoriawan & Apriliyanti, 2023). By identifying multiple equifinal configurations that lead to high REEV, this study offers a means of resolving this inherent "theory-method" contradiction. Specifically, its contributions manifest in the following ways:

- (1)

A paradigm shift from factors to configurations: This study identifies three equifinal pathways to high REEV: the endogenous factor-driven path, the formal institution-driven path, and the multi-source support-compensatory path. This finding confirms that success does not stem from a simple aggregation of "best" factors but from specific synergistic configurations among them (Tekic & Kurnosova, 2024). For instance, financial resources act as a core condition in one configuration, yet their absence is part of the causal recipe for success in another. This insight transcends the conventional debate over the relative importance of individual factors and shifts the analytical focus from "What are the key factors?" to "How do key factors combine?" Accordingly, this research advances entrepreneurial ecosystem studies from a factor-centric to a configurational perspective, providing robust empirical support for the holistic nature of entrepreneurial ecosystems articulated by Isenberg (2010).

- (2)

Revealing the micro-mechanisms of interaction among entrepreneurial ecosystem elements (substitution and complementarity): Addressing a critical gap in empirical research on the internal interaction processes within entrepreneurial ecosystems (Isenberg, 2010), this study’s cross-configurational analysis clearly elucidates the mechanisms of functional substitution and complementarity among elements. The findings indicate significant substitutional effects between physical and financial resources, as well as between endogenous resources and external institutional support. This implies that REEV can emerge from the functional interchangeability of these elements, echoing core tenets of resource orchestration theory (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Bals et al., 2023). Furthermore, the results demonstrate that resources and social capital become effective only when embedded within appropriate institutional arrangements. This insight deepens the theoretical understanding of the pivotal role played by institutions in entrepreneurial processes (North, 1990; Xiong et al., 2024) and challenges simplistic interpretations of institutional determinism (Yin et al., 2024).

- (3)

This study reinforces the contextual embeddedness of entrepreneurial ecosystem theory. While mainstream entrepreneurial ecosystem research has predominantly focused on urban, high-tech contexts, emphasizing formal support factors such as venture capital (Isenberg, 2010; Roundy et al., 2017; Stam, 2015), our research shifts the theoretical lens to rural China. We find that informal institutions, represented by family support, serve as a core condition in multiple configurations leading to high REEV. This finding not only responds to calls for deeper institutional analysis within entrepreneurial ecosystem research (Huang et al., 2023) but, more significantly, confirms that in social contexts characterized by strong relational ties, informal institutions can play a more influential role in shaping the ecosystem than conventional formal factors (Xiong et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2024). This indicates that the key elements of an entrepreneurial ecosystem and their interaction patterns are profoundly shaped by the socio-cultural context in which they are embedded. Consequently, this study extends the theoretical boundaries of entrepreneurial ecosystem theory, advancing its evolution from a universalist framework toward a more context-contingent perspective (Roundy et al., 2017).

Second, this study contributes to the literature on rural e-commerce entrepreneurship by introducing a framework of "causal complexity," identifying the dual logics of "opportunity" and "institution" that drive this phenomenon. Whereas previous research has tended to seek single, linear drivers (Huang et al., 2022), this study employs fsQCA to reveal complex causal patterns characterized by non-linearity, conjunctural causation, and equifinality (Schneider & Wagemann, 2012; Huang et al., 2023).

- (1)

Moving Beyond the Assumption of Necessary Conditions to Uncover Diverse Entrepreneurial Pathways: This study finds that no single condition is sufficient on its own to induce high REEV. Even social capital (Peredo & Chrisman, 2006; Hertel et al., 2021), widely regarded as essential, must be embedded within specific configurations of factors for its effects to manifest. This finding challenges the implicit assumption in the existing literature regarding the universal importance of certain factors and instead offers a more nuanced theoretical perspective for understanding the diverse pathways through which rural entrepreneurship can emerge (Huang et al., 2023; White et al., 2021).

- (2)

Identifying Dual Logics (Opportunity-Anchoring and Institution-Anchoring): The three configurational paths identified in this research reflect two overarching theoretical logics. The first two configurations exemplify opportunity-anchoring, where entrepreneurs endowed with relatively superior resources succeed by identifying and exploiting business opportunities. This aligns with mainstream theories of entrepreneurial opportunity (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Mei et al., 2020). However, the third configuration reveals a complementary logic of institution-anchoring: in contexts with scarce market-based resources, formal institutions (government-led) and informal institutions (family-level support) can interact synergistically (North, 1990; Xiong et al., 2024) to reduce entry barriers and provide inclusive support, thereby stimulating entrepreneurial activity (Huang et al., 2023). This finding enriches the understanding of entrepreneurial mechanisms by showing that depending on the resource context, entrepreneurial activity may be driven by distinct core logics, which in practice may manifest as "bottom-up" versus "top-down" models of entrepreneurship (Zang et al., 2023; Chu et al., 2025).

Finally, this study makes a methodological contribution by developing a two-stage analytical framework that moves “from configuration identification to mechanism elucidation,” thereby enhancing the causal explanatory power of qualitative comparative analysis. This framework responds to long-standing calls within the qualitative comparative analysis community to integrate “variable-oriented” and “case-oriented” approaches (Ragin, 2008; Schneider & Wagemann, 2012). In the first stage, fsQCA is used to identify multiple, equifinal configurations associated with the outcome. In the second stage, process tracing is conducted on typical cases within each configuration to elucidate the underlying micro-level causal mechanisms (e.g., opportunity leveraging, opportunity building, and institution empowering). This is followed by a cross-case comparison that abstracts these specific mechanisms into higher-level theoretical logic. The framework offers researchers a replicable pathway for theory development that combines generalizability, achieved through identifying multiple equifinal configurations, with deep causal explanatory power gained through mechanism elucidation.

Practical implicationsThe findings of this study yield specific and context-sensitive policy implications for promoting rural e-commerce. The core message is that policymakers should abandon a "one-size-fits-all" approach and instead adopt "place-based" configurational strategies, consistent with calls for context-specific approaches in rural development (White et al., 2021).

First, for regions characterized by opportunity-anchoring, the core policy orientation should be empowerment rather than intervention. These regions often possess abundant material resources, a strong entrepreneurial culture, and favorable commercial conditions. As such, they exhibit bottom-up entrepreneurial dynamics (Lin & Tao, 2024), where local residents engage in entrepreneurship spontaneously and organically, making excessive policy intervention unnecessary.

For opportunity-utilization regions (Configuration 1), policy should focus on optimizing channels for resource monetization. Governments could invest heavily in modern cold-chain logistics to connect production areas with urban markets, support the creation of regional public brands to enhance value-added, and offer targeted e-commerce skills training to enable residents to better leverage digital platforms.

For opportunity-construction regions (Configuration 2), policy should serve as a catalyst. Key measures include guiding social and financial capital into local industries through start-up funds and tax incentives, encouraging cross-sector innovations such as "agriculture + cultural tourism" or "e-commerce + live streaming," and providing institutional safeguards and “room for trial and error” to support the initial development of emerging business models.

Second, for regions driven by "institution-anchoring," the core policy principle should be synergy. These regions often lack market-based resources and depend more heavily on formal institutional support and family-level informal institutions. They exhibit top-down entrepreneurial characteristics (Lin & Tao, 2024).

In such regions (Configuration 3), informal institutions centered on the family form the bedrock of entrepreneurial vitality. A strategic approach is to foster functional coupling between government-led institutional support and micro-level family dynamism. For example, inclusive financial products could be designed with families as the credit unit, or collective training and resource-matching events could be organized at the village or community level. Such measures can generate synchronized momentum between macro-level empowerment and micro-level initiative.

Limitations and future research directionsWhile this study offers several important contributions, it also has limitations that point to directions for future research.

First, the analysis focuses on rural e-commerce activity at the macro-regional level, and thus the external generalizability of the findings requires further verification. Future research could conduct cross-context comparative analyses in other developing countries or in rural areas with different cultural and institutional contexts to test the robustness of the theoretical framework proposed in this study.

Second, this study uses one-period lagged data. While this approach helps reveal associations between different combinations of conditions and the outcome, it does not capture the dynamic evolutionary processes underlying the configurational paths. Future research could employ longitudinal case studies or dynamic analytical methods to explore how regions transition over time into "opportunity-anchoring" or "institution-anchoring" states.

Finally, this study focuses on identifying the configurational paths that lead to "high entrepreneurial activity." It does not examine the paths associated with entrepreneurial failure, nor does it investigate differences in the quality of entrepreneurship (such as innovativeness, sustainability, or social value) across successful configurations. Future research could extend this work by developing a more comprehensive configurational theory encompassing the success, failure, and quality dimensions of rural entrepreneurship.

ConclusionThis study systematically uncovers three heterogeneous paths that drive REEV and, based on these, identifies two underlying driving logics—opportunity anchoring and institution anchoring—as well as substitution effects among conditions. The core argument is that the enhancement of rural e-commerce entrepreneurial activity does not depend on the isolated presence of individual regional factors. Instead, it arises from the strategic anchoring and interactive effects formed by different supportive conditions within a region, shaped by its unique resource and institutional endowments. These insights deepen our understanding of the complexity of entrepreneurial processes and provide a more context-contingent analytical perspective for promoting endogenous and sustainable development in less-developed regions. They also offer more feasible and context-sensitive policy guidance for addressing the challenges of non-ideal regional environments.

FundingThis work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21BGL032) and the High-Level Talents Project in Social Sciences at Xiamen University of Technology (Grant No. YSK24005R).

Ethics statementNot applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statementLijuan Huang: Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Yi Huang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zhe Rong: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Guojie Xie: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Lijuan Huang received research funding from the Project of National Social Science Fund of China (No. 21BGL032) for this study. This work was also supported by the High-Level Talents Project in Social Sciences at Xiamen University of Technology (Grant No. YSK24005R). Other author has no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors. We confirm that these interests do not influence the design, execution, or reporting of this research, and we are committed to maintaining the integrity and objectivity of our work throughout the entire publication process.

We sincerely appreciate the anonymous scholars for their constructive revision suggestions on the preliminary version of this study. We also extend our gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback and recommendations. Their contributions have significantly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

Table A1; Table A2; Table A3; Table A4; Table A5

Qualitative evidence for rural e-commerce entrepreneurial vibrancy.

| Configurations, Mechanisms, Case | Qualitative evidence |

|---|---|

| S1: Opportunity leveraging Shuyang, Suqian, Jiangsu |

|

| S2: Opportunity building Lin’an district, Hangzhou, Zhejiang |

|

| S3: Institution empowering Cao County, Heze, Shandong |

|

Cases and Membership Scores for Each Configuration.

Note: The first number in parentheses indicates the membership score in the configuration (solution) set, and the second number indicates the membership score in the outcome set. For example, “Shandong (0.82, 1)” means that Shandong has a membership score of 0.82 in configuration S3 and a score of 1 in the set of high REEV.

Analysis of Necessity for High REEV.

Note: ∼ indicates the absence of or a low level of a condition. For example, ∼ family support refers to the absence of family support or low family support (i.e., a membership score in the set of family support < 0.5).

Results of Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA).

Note: Effect sizes are based on 10,000 random samples generated via approximate permutation. The necessity of a condition is expressed by the effect size d (i.e., the size of the space above the ceiling divided by the total observed space). Benchmarks for d: 0 ≤ d < 0.1: small effect, 0.1 ≤ d < 0.3: medium effect, 0.3 ≤ d < 0.5: large effect, and d ≤ 0.5: very large effect.); * p < 0.05.

Comparison of Initial Solution and Test Set.

Note: Black circles indicate the presence of a condition; crossed-out circles indicate its absence; blank cells indicate "don't care." Large circles represent core conditions, while small circles represent peripheral conditions.

Prof. Huang received the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Nanchang University, Nanchang, China, in 1991 and 2006, respectively. She is currently the Director of the Academy of E-Commerce Research, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China. She has authored over 90 articles in international/national authoritative journals. Her current research interests include rural e-commerce and entrepreneurship, and supply chain management.