The widespread diffusion of information and communication technologies, along with post-pandemic work arrangements, has led organizations to increasingly utilize dispersed teams to integrate knowledge across various locations. Despite the potential benefits, dispersed teams often fail to continuously innovate their processes because of hampered feedback exchange among team members. Our study explores how team dispersion affects the development of team feedback climate, and, in turn, team process innovation. We rely on a structural equation modeling approach applying the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique to analyze survey data from 594 team members and leaders, as well as objective data across 123 teams. The study highlights that the lack of co-location hinders an effective feedback climate, which is essential for fostering teams’ ability to continuously innovate their work processes. Additionally, it examines how team empowerment can mitigate the negative effects of dispersion by giving team members greater control. Our findings underscore the importance of feedback climate and suggest that empowerment can alleviate the negative effects of dispersion, offering valuable insights for managers and organizations to reap the advantages of new distributed work models and alleviate the burden of liabilities.

The widespread adoption of information and communication technologies, coupled with the post-pandemic emergence of new work arrangements, has enabled organizations to increasingly leverage the intellectual resources of a dispersed workforce (Kraus et al., 2023; Orlandi et al., 2024). Despite the potential benefits, distributed teams often fail to meet performance expectations because of overlooked social and managerial challenges. While distributed teams can facilitate an optimal allocation of team members, they can also increase the risk of errors and impede the effective sharing of important information (Bauer et al., 2022; Civera et al., 2022). This could jeopardize process innovation—that is, the continuous improvement of the work processes underlying the production of products or services.

Creating a team environment where members can reflect and learn is paramount for process innovation (Lei et al., 2022). From such a perspective, team feedback climate represents a collective perception about the extent to which feedback-related behaviors are enacted and supported within the team. Indeed, rather than being rooted in isolated personal experiences, team climate depends on a collective understanding of team interactions (Schneider, 2020). By anchoring the concept of feedback at the team level and focusing on the shared perspective of team behaviors (i.e., giving, receiving and using feedback), team feedback climate reflects a deeper layer of the team’s social environment.

Although the pivotal role of feedback in team functioning is recognized by previous research (McLarnon et al., 2019), several important gaps remain. First, most studies have focused on product development and highly innovative projects (Nieto et al., 2015). Research on more traditional work settings that rely on the constant efforts of team members to improve their processes remains scarce (Hervas‐Oliver et al., 2016). Recent research suggests that continuous improvement behaviors enhance organizational performance, resilience, and long-term growth (Tortorella et al., 2021). In this context, it is pertinent to explore team behaviors aimed at constant improvement.

Second, existing research has mainly examined co-located environments, ignoring the impact of new work arrangements on the development of a positive feedback climate and its effects on team members’ ability to innovate. From this standpoint, Feitosa and Salas (2021) called for empirical research, arguing that a situation characterized by low proximity may hinder team members’ optimal interaction and hamper the development of effective feedback processes. In this context, our first goal is to elucidate how the dispersion of team members restricts the development of a feedback climate, and, in turn, adversely impacts team process innovation.

In addition to examining the impact of dispersion on team feedback climate, it is imperative to ascertain how organizations can harness the benefits of dispersion while mitigating its negative effects (Baptista et al., 2020). For example, recent evidence outlined that a crucial challenge for organizations is identifying the appropriate managerial approach to facilitate team members’ interactions in dispersed settings (Forbes, 2024). Research suggests that providing significant decision control to team members (i.e., team empowerment) can facilitate team interaction (Mansoor et al., 2025). Thus, team empowerment can help address the challenges of dispersion and foster a feedback climate by substituting for many control functions typically performed by a physically present team leader (Greimel et al., 2023). Given these considerations, our second goal is to investigate how team empowerment can mitigate the adverse effects of dispersion on feedback climate and process innovation.

To elucidate these phenomena, we rely on the Social Information Processing (SIP) theory (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978), which posits that individuals form behavioral patterns based on the social cues available in their environment, especially under conditions of ambiguity. This renders the SIP theory particularly relevant for understanding how team members’ dispersion affects team feedback climate, and, in turn, influences innovation, and how team empowerment can promote individuals’ interpretation and uptake of these social signals.

Our study makes several theoretical and practical contributions. First, by highlighting the importance of feedback climate for team process innovation, we draw attention to the challenges that novel work arrangements pose to its development. Feedback climate could represent a way to sustain continuous improvement and long-term collective development (London & Sessa, 2006; Casalegno et al., 2023). From a managerial perspective, this underscores the need to intentionally foster feedback-rich environments in dispersed teams.

Second, we address calls from previous research to examine how organizational choices regarding team decision latitude impacts team outcomes. For instance, by investigating team empowerment as a mechanism through which organizations delegate authority to teams, we extend the research that shows that enabling team empowerment promotes effective interaction (Lunkes et al., 2018). Our findings suggest that empowerment can help mitigate the challenges of team dispersion while leveraging its potential benefits. These insights are particularly relevant for managers designing distributed workforce models, as they highlight the importance of granting teams greater autonomy and decision-making latitude (Grabner et al., 2022).

Third, consistent with Breuer et al. (2024), we aim to balance theoretical advancement with practical implications. By exploring the roles of feedback climate and empowerment in dispersed teams, we help organizations make more informed staffing decisions by highlighting both the risks of dispersion and the benefits of team empowerment for effective distributed team design, which is particularly relevant for meeting the challenges of future work scenarios (Klaser et al., 2023).

Finally, from a methodological perspective, our study collected data from multiple sources within each team, including both team members and leaders, to reduce common-source bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). This is particularly valuable given the difficulty of gathering such data in field settings. Our sample—594 individuals across 123 teams—is relatively large compared to previous field studies in this area. Additionally, we incorporated both objective and subjective measures of team dispersion, aligning with O’Leary and Cummings’s (2007) call to integrate these distinct approaches in complex team research.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of the SIP theory and develop our hypotheses. Next, we discuss the methodological approach and present the results obtained through structural equation modeling analyses performed with the Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique. Finally, we present the findings and outline their theoretical and practical implications.

Theory and hypothesesSocial information processing theoryResearchers have developed several models and constructs to analyze the environment that shapes the way team members interact with each other. The present study is framed within the theoretical perspective of Salancik and Pfeffer’s (1978) SIP theory, which emphasizes social cues and context in shaping individual attitudes and behaviors. According to this theory, employees do not operate in an organizational vacuum. Instead, they engage in active interactions with each other to comprehend events that occur in their workplaces, suggesting that attitudes and behaviors are formed based on information collected from the social environment (Chen & Weng, 2023). For example, Glomb and Liao (2003) identified that employees were more likely to engage in aggressive behavior themselves when other members of their work group engaged in aggression—this reveals how group behavior guides the actions of individual employees. In this vein, others have outlined that team members develop a sense of collective fairness by observing the cues by other colleagues within the team (Magni et al., 2018).

This process of meaning-making is fundamentally shaped by the availability and accessibility of social cues, and it is shaped by what is visible, salient, and reinforced in their social environment (Grippa et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). When workers lack direct interaction, they look to others to understand what is expected of them, how their work is valued, and what behaviors are appropriate. In this manner, the presence of social information becomes a defining factor in how employees develop a shared representation of the behaviors that characterize the team environment.

This interpretive process becomes especially relevant in the context of geographically dispersed teams, where social information is often more difficult to access. In co-located teams, workers are embedded in a shared physical space where information flows organically through informal conversations, observations, and spontaneous interactions (Civera et al., 2022). In contrast, dispersed teams operate in settings where many of these ambient signals are absent, and where individuals must actively seek out information to comprehend their environment.

Team feedback climate is particularly consistent with the SIP theory because it emerges from the visible, socially embedded behaviors that occur in the team—such as giving, seeking, and receiving feedback. When feedback behaviors are enacted regularly and visibly within a team, they send unambiguous social signals about the team’s norms, values, and expectations regarding feedback. These signals become the basis for shared perceptions, which represent the essence of climate. Conversely, when social information is scarce or difficult to access, employees are less likely to develop a shared understanding about feedback behaviors within the team.

Moreover, the SIP theory emphasizes cultivating environments where meaning can be shared, reinforced, and aligned (Chiu et al., 2016) despite the absence of physical co-presence (Wang et al., 2022). Consistent with this perspective, we theorize that team empowerment could represent a key factor that mitigates the negative effects of team dispersion on feedback climate. This is because empowered teams are more likely to take initiative, communicate openly, and model supportive behaviors, thereby providing unambiguous social information that helps maintain a constructive feedback climate despite physical separation. In this manner, empowerment acts as a compensatory mechanism, shaping the interpretive context that guides team members’ perceptions and interactions even in the absence of co-location.

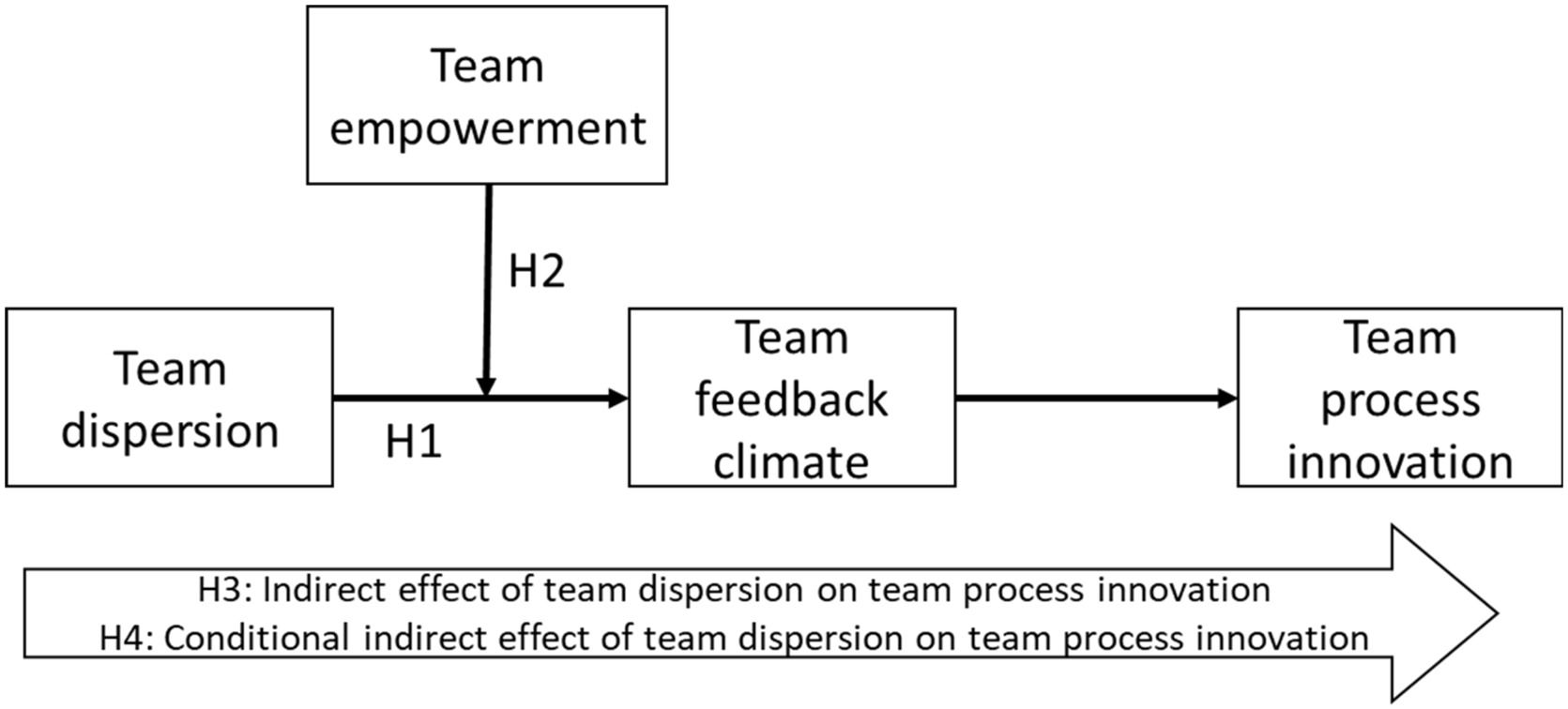

In the context of these considerations, Fig. 1 illustrates the theoretical model as well as the hypotheses we tested by relying on the SIP theory.

The effect of team dispersion on team feedback climateTeam feedback climate is a pivotal element of teamwork regulation. It represents a shared cognition held by team members regarding the manner in which they share information about actions, events, or behaviors, and apply such information to improve activities and promote teamwork (London, 2003; London & Sessa, 2006). Therefore, team feedback climate reflects the extent to which team members perceive that feedback behaviors are present to stimulate critical reflection for adjusting their behaviors and guiding their actions toward the outcomes or the processes of a team activity (Bartram & Roe, 2008). Additionally, recent studies suggest that feedback among teammates stimulates behaviors that serve the needs of the team by fulfilling multiple functions, such as providing information when team members deviate from their goals, or encouraging critical reflection on tasks and situations to generate novel insights and approaches (Bartram & Roe, 2008). As such, the existence of a team feedback climate, wherein members promote mutual development, may be crucial in supporting the team achieve its goals. This is especially important in contexts where teams must continuously innovate their business processes.

Consistent with the SIP theory, the development of a feedback climate within the team is guided by the interaction among team members, who develop a set of shared principles and expectations about how to manage their activities and their information exchange. However, when team members are dispersed across different sites, they have limited opportunities for spontaneous communication, rendering the exchange of information that guides team activities more challenging (Gabelica et al., 2012; Magni & Maruping, 2019). This limitation prevents them from acquiring and maintaining knowledge about team activities, adjusting future actions, and implementing new courses of action (e.g., Carter et al., 2019; Donia et al., 2018). In a dispersed setting, the opportunities to observe others in their daily activities are limited, which hinders the development of a team environment based on the exchange of feedback among team members (e.g., Geister et al., 2006; Klaser et al., 2023). Dispersed team members have limited ability to mutually monitor task progress and verify necessary information for continuous improvement (Civera et al., 2022; Handke et al., 2024). This impedes the provision of timely feedback to other team members during the decision-making process. Moreover, research indicates that when individuals operate in a dispersed setting they are more likely to focus on their local tasks and tend to overlook their team members’ concerns across different locations (Handke et al., 2024). This diminishes team members’ mutual consideration, thereby eroding the likelihood of exchange of constructive feedback. In this context, we hypothesize that team members’ dispersion hampers the development of a team feedback climate:

Hypothesis 1 Team members’ dispersion has a negative effect on team feedback climate.

Team empowerment implies delegation of control to the team level, where individuals have a better understanding of the work environment and more informed and aware decisions can be made based on daily activity (Kirkman et al., 2004; Mansoor et al., 2025). Essentially, team empowerment focuses on the shift of control from the leader to the team members. It can be defined as team members’ collective belief that they have the authority to control their work environment, and are responsible for their team’s functioning. For instance, Bauer et al. (2022) indicated that members’ ability to share knowledge is essential to managing distributed expertise to ensure effective application of necessary expertise in time-critical and novel contexts. In line with this perspective, team empowerment could mitigate the challenges arising from team members’ dispersion by creating an atmosphere wherein members share a perception of having direct control and impact on team activities. As such, we expect that team empowerment mitigates the negative effects of dispersion on the team’s ability to develop a feedback climate environment.

When team members share a sense of autonomy and responsibility toward the team activities, they are more likely to consider other members’ perspectives and express their opinions to foster continuous improvement (Grabner et al., 2022), thus identifying opportunities to interact despite team dispersion. As such, team members would be more likely to provide each other timely feedback and enhance their ability to conduct team activities. Indeed, when team members feel a sense of control over team activities, they tend to be proactive and persistent in identifying how they can handle these activities, thus overcoming the interaction liabilities rooted in team dispersion (Peñarroja et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022). Furthermore, empowerment reflects team members’ feeling of having autonomy in making team decisions, thus inducing team members to increase their communication flow and limit a wait-and-watch approach. Therefore, when the team perceives a sense of empowerment, it is more likely to activate communication channels—even in a dispersed setting—and facilitate effective feedback exchange among team members.

Hypothesis 2 Team empowerment moderates the relationship between team dispersion and team feedback climate, such that the relationship is less negative when team empowerment is higher.

The ability of teams to achieve their goals can be traced back to the manner in which team members interact to ascertain the contextual situation in which are embedded, and to activate the knowledge of different team members (Handke et al., 2024). A feedback climate enables team members to acquire and apply relevant knowledge (Carter et al., 2019; DeShon et al., 2004; Geister et al., 2006) to make adjustments for future actions and strategies (e.g., Carter et al., 2019). This promotes the team’s ability to innovate the business processes. However, in a situation where team members are dispersed, the development of a feedback climate appears particularly challenging because individuals’ spontaneous interactions are limited, thus hampering team members’ ability to embrace innovative actions (Rafique et al., 2022). Dispersion of team members may affect team process innovation by hindering team members’ ability to develop a constructive feedback climate, which is pivotal for enabling team members to build new knowledge and guide their activities toward the goal. Moreover, as the effects of members’ dispersion on team feedback climate are contingent on the degree of control team members have in terms of empowerment, we expect that the relationship between team members’ dispersion and process innovation through feedback climate is moderated by team empowerment. Teams with a higher degree of empowerment are less likely to suffer the effect of dispersion on feedback climate, thus enabling team members to better activate feedback exchange processes that facilitate innovate. In other words, a high degree of empowerment decreases the potential misalignment among team members, fostering continuous evaluation and adjustment of team members’ behaviors to ameliorate business processes. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3 Team feedback climate mediates the relationship between team dispersion and team process innovation.

Hypothesis 4 Team empowerment moderates the indirect effect of team dispersion on team process innovation through team feedback climate, such that the indirect effect is less negative when team empowerment is higher.

Data for our study were collected in naturally occurring conditions within different organizations. Particularly, our study involved team leaders working in the accounting function who participated in executive education courses on leadership development at a European business school between 2021 and 2022, and who decided to involve their team in an elective activity to enhance their awareness about their leadership impact. The decision to focus on teams in the accounting domain is grounded in both practical and theoretical considerations. First, while the use of distributed teams is expanding across industries (Deloitte, 2024), accounting stands out as particularly well-suited to remote work owing to its task structure, reliance on digital tools, and low need for physical presence (Forbes, 2023). This renders it an ideal setting to study the dynamics of dispersed collaboration. Second, the role of feedback climate is especially crucial in accounting teams, where professionals must frequently identify and address deficiencies in formal control systems (Choudhury, 2015). In this context, feedback serves not only as a performance-enhancing tool but also as a key error-detection mechanism, supporting learning, accountability, and continuous improvement (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; London & Sessa, 2006). Thus, accounting teams offer a highly relevant context to examine how dispersion and empowerment shape feedback dynamics and innovation in professional knowledge work. At the beginning of the training program, a researcher presented in synthesis the purpose of the activity: team leaders and team members were invited to complete a questionnaire. Each team leader had the opportunity to receive a personalized report (with aggregated data) highlighting the strengths and areas of improvement of their team. We asked each team leader to invite their members and provide the rosters of contacts of team members interested in participating. Interested individuals received an invitation email describing the process for completing the online survey and were informed about the confidentiality of their data. Their participation was voluntary. A total of 594 individuals belonging to 123 teams provided usable responses.

From a research-design standpoint, collecting data from multiple sources in each team, including obtaining team process innovation ratings from team leaders, enabled us to avoid potential common-source bias. Moreover, from a research-design perspective, team feedback climate, team process innovation, and team empowerment have been modeled as reflective constructs, while dispersion was modeled as a formative construct.1 Furthermore, because some of the data from this team-level study were collected from multiple individuals within each team, it was necessary to justify the aggregation of individual-level within-team ratings to team-level scores (Klein & Kozlowski, 2000). This included a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on team membership to test the between-group variation, and the computation of ICC(1) to verify the between-group versus within-group variability in the individual-level responses. We also calculated the within-group agreement index (rwg), which indicates the extent to which team members’ responses to the survey questions converge greater than would be expected by chance (James et al., 1984).2

MeasuresTeam process innovationTeam leaders assessed team process innovation with a four-item scale based on Kim et al.’s (2012) measure, examining the extent of the team’s innovation. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94, indicating good internal consistency.

Team feedback climateMembers within each team were asked to evaluate the existence of a team feedback climate in their team based on four items derived from Ostroff et al. (2013) to estimate the extent to which team members mutually shared and applied feedback. Results of a one-way ANOVA were statistically significant, suggesting significant differences in between-team ratings of team feedback climate (F = 1.34, p < 0.05). The ICC(1) value was 0.10, while the mean rwg was 0.85. These statistics indicate acceptable levels of within-group agreement and between-groups variability, allowing us to ascertain that a team-level score was computed by averaging the responses from team members, as indicated by Liao and Rupp (2005).

Team dispersionTo measure team dispersion, we considered both the structural and psychological facets (Raghuram et al., 2019). From a structural standpoint, we relied on the site index, which represents an objective measure that examines the proportion of team members who work in different locations. Specifically, we asked team leaders to rely on their team members’ rosters and report the percentage of team members located across different buildings. In addition to the physical dispersion across sites, we considered the cognitive facet of dispersion by asking team members their level of agreement about the degree to which their team relied on communication technologies to define the best course of action for the team (1=fully disagree; 5=fully agree). Together, these indicators were applied to model dispersion as a formative construct.

Team empowermentTeam members reported their level of agreement with a four-item scale of empowerment from Kirkman et al. (2004). The results of a one-way ANOVA based on team membership suggested significant between-team variation in members’ ratings of team empowerment (F = 2.49; p < .01). The ICC(1) for the scale was 0.18 and the median rwg was 0.90, justifying the aggregation of individual within-team scores on the empowerment to the team level.

ControlsTo isolate the impact of dispersion and team feedback climate, several variables that may affect team process innovation were included as controls, thus considering them as predictors of process innovation in the analytical model. In addition to controlling for the number of team members, we controlled for task interdependence, average team members’ work tenure, and managerial tenure of the team leader because they may potentially affect team outcomes (Handke et al., 2024; Grabner et al., 2022). Specifically, interdependence was measured using three items from Campion et al. (1993). Average team tenure was calculated by computing the mean number of years of overall work experience among team members. Managerial team tenure was assessed based on the number of years the team leader had held managerial responsibilities. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for the variables in the study.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Notes: **p<.01.

Consistent with previous research, we tested our model with a two-step approach: first, we verified the robustness of the measurement model through some preliminary analyses, and thereafter, we ran a structural model to test our hypotheses. To conduct our analyses, we applied a Partial Least Squares (PLS) technique relying on SmartPLS 4.1 to assess the robustness of our measurement model and test our research hypotheses. PLS is a component-based structural equation modeling approach that aims to maximize the variance explained in the dependent latent variables with fewer constraints and statistical specifications if compared to covariance-based techniques (Fornell & Bookstein, 1982). The reason to consider PLS an appropriate analytical technique for our study is threefold (Hair et al., 2022). First, many of our variables are based on several indicators, and PLS calculates indicator loadings in the context of the model rather than in isolation. Second, PLS has been shown to be a superior technique when interaction terms are present because it attenuates the potential biases of the measurement error. Third, PLS enables dealing with reflective and formative measures within the same model.

Preliminary analysesTo ensure a first assessment of the quality of our feedback climate, team empowerment, and team process innovation measures, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses. A three-factor model provided a significantly better fit (χ2 (51)=95.42; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) =0.08; Comparative Fit Index (CFI)=0.96) than the single-factor model (χ2(54) =552.90; RMSEA=0.27; CFI=0.50), and a two-factor model where team empowerment and feedback climate loaded on the same factor model (χ2(53) =137.36; RMSEA=0.11; CFI=0.92). This evidence is consistent with previous research suggesting that values of 0.08 or less for RMSEA indicate good fit (Dilalla, 2000) and CFI values higher than 0.90 reflect better-fitting models (Byrne, 2010). Furthermore, we examined convergent validity by analyzing the average variance extracted (AVE), and verified internal consistency by examining Cronbach’s alpha. The suggested threshold for demonstrating internal consistency are 0.50 for AVE and 0.70 for Cronbach’s alpha. Moreover, we assessed the discriminant validity in two ways. First, we examined the construct loadings and cross-loadings for latent constructs. Each item loading is higher on the construct of interest than on any other latent variable, suggesting a good discriminant validity of our constructs (Hair et al., 2022) (see Table 2). Furthermore, we relied on Fornell and Bookstein’s (1982) criterion by comparing the square root of AVE with inter-construct correlations. Results show a good discriminant validity as the square root of the AVE of each latent construct is greater than the highest correlation with any other construct (Fornell & Bookstein, 1982).

Loadings, cross-loadings, scale reliability, and Average Variance Extracted.

Notes: AVE = Average Variance Extracted; PCSINN=process innovation, EMPOW=team empowerment, FEEDCL=feedback climate.

Hypothesis 1 posited a negative influence of team dispersion on team feedback climate. Results reported in Fig. 2 indicate that team dispersion has a significant negative effect on team feedback climate (β = −0.45, p < .001), thus corroborating our hypothesis. We calculated Cohen’s ƒ2 for assessing the effect size of the hypothesized relationship, with values of 0.02 indicates a good effect size in field studies (Kenny, 2016). Cohen’s ƒ2 for the model is 0.51, indicating a large effect size of geographical dispersion on team feedback climate.

Hypothesis 2 posited that team empowerment moderates the relationship between team dispersion and team feedback climate such that the relationship is weaker when team empowerment is high. Support for the moderation hypothesis was assessed in several ways. First, the coefficient for the interaction between team empowerment and team dispersion is positive and significant (β = 0.16, p < .001), suggesting that team empowerment mitigates the negative effect of team separation on team feedback climate. Second, following the guidelines outlined by Aiken and West (1991), the interaction effect was plotted at one SD above and below the mean for team empowerment (see Fig. 3).

Finally, to verify the magnitude of the moderating effect, we calculated Cohen’s ƒ2 for the hypothesized interaction. Cohen’s ƒ2 for the interaction model predicting team feedback climate is 0.07 corroborating a medium-high magnitude of the interaction between team dispersion and team empowerment.

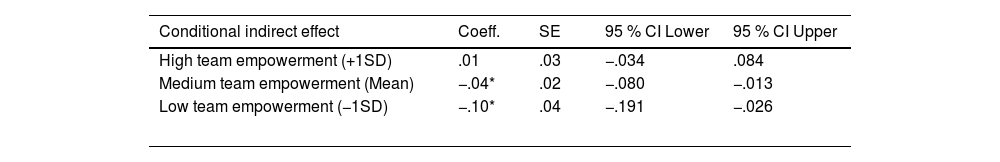

Hypotheses 3 and 4 pertained to the indirect effects of team separation on team process innovation and the conditional effect at different degrees of empowerment. To test the indirect effects, first, we examined the effect of feedback climate on team process innovation (β = 0.24, p < .01), and thereafter, ran a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 replications to investigate the indirect effect. Results show a negative indirect effect of dispersion on team process innovation (effect = −0.11, p < .05, 95 % CI [−0.174; −0.039]), corroborating Hypothesis 3. Moreover, to test Hypothesis 4, we also examined whether team empowerment moderated the mediated relationships between team dispersion and process innovation through feedback climate by calculating the magnitude of the indirect effect at the mean and at ± 1 standard deviations for team empowerment. Results reported in Table 3 suggest the indirect effect of team dispersion on process innovation through feedback climate is contingent on team empowerment, corroborating Hypothesis 4. Moreover, the index of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015) is significant 0.013 p<.05 CI [.001;.037]).

Conditional indirect effect of team dispersion on team process innovation through feedback climate at different levels of team empowerment.

Notes: Results are based on 10,000 bootstrap samples. *p<.05.

Our results show that team dispersion exerts a strong negative effect on the development of a feedback climate, which in turn undermines teams’ ability to innovate their processes. At the same time, empowerment emerges as a crucial factor that mitigates these detrimental effects, thus contributing to the debate on new work settings. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, our results indicate that dispersion hampers the development of a team feedback climate. The strong coefficient linking dispersion to feedback climate (β = –.45) emphasizes that even modest spatial separation can create significant barriers for social exchange. This finding aligns with that of previous research showing that physical separation decreases opportunities for spontaneous conversations, observation of colleagues’ work, and informal learning (Geister et al., 2006; Handke et al., 2024). Specifically, our study extends the argument that dispersion impedes information exchange by demonstrating that dispersion undermines the development of a team feedback climate, which plays a pivotal role in fostering team members’ innovative abilities. In line with the SIP theory, our study outlines that when cues about others’ behaviors are scarce or unintelligible, employees struggle to develop a shared understanding around feedback among team members. This hinders the development of a team climate fostering continuous development and improvement. This result echoes the concerns raised by Feitosa and Salas (2021), who argued that the absence of proximity can create relational blind spots in virtual teams.

In the context of Hypothesis 2, we identify that team empowerment significantly attenuates the negative effect of dispersion on feedback climate. The moderating effect of empowerment (β = 0.16) is particularly meaningful because it indicates that organizational practices can buffer a substantial portion of dispersion’s negative impact. This contingent view contrasts with studies that portray virtual collaboration primarily in terms of limitations (Civera et al., 2022) and emphasizes exploring the enabling conditions under which dispersed teams can thrive. Our finding corroborates existing evidence that granting autonomy and decision latitude fosters proactive behaviors and mutual exchange among team members (Kirkman et al., 2004; Mansoor et al., 2025). Indeed, empowerment acts as a compensatory mechanism that enables team members to assume greater ownership of their work and interactions, enabling them to overcome the liabilities of dispersion. Thus, rather than treating dispersion as an insurmountable barrier, organizations may view it as a contingent challenge that can be addressed via intentional design choices. Combining the results from Hypotheses 1 and 2 is particularly relevant for the debate on new work arrangements, as it clarifies how organizations can alleviate the liabilities of dispersion by providing individuals with greater decision latitude.

A third important insight pertains to the indirect effect of dispersion on team process innovation through feedback climate contingent to team empowerment—this is related to Hypotheses 3 and 4. Existing studies have mainly explored product innovation in creative or technological domains (Nieto et al., 2015). However, our results demonstrate that even process innovation in professional services relies on the existence of an environment rooted in feedback climate. This is consistent with the results of studies highlighting the centrality of continuous improvement behaviors for long-term organizational performance and resilience (Tortorella et al., 2021). By confirming that dispersion erodes process innovation through its negative influence on feedback climate, our study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how virtual work arrangements may constrain process innovation that pertain to more traditional work environment, and how empowerment plays a pivotal role in alleviating the role of dispersion and enables team process innovation.

Theoretical contributions and practical implicationsThe reliance on dispersed teams has been increasing in recent years, raising the interest of scholars and managers in how they can support organizations in dealing with the challenges associated with this work configuration and support continuous innovation (Bristol-Alagbariya et al., 2022). Our study aims to build on previous literature to provide further insights into the pivotal role of a feedback climate in shaping team process innovation, and how team dispersion may hamper the development of this climate. Specifically, our study makes significant contributions to the theoretical debate and provides actionable insights for the managerial community.

Theoretical contributionsFirst, our findings contribute to the literature by extending the focus from information exchange to the broader construct of feedback climate. While previous research has emphasized information sharing in dispersed settings (Grippa et al., 2021), information exchange remains largely unidirectional. Feedback climate, instead, captures the dialogical and reciprocal processes through which teams collectively evaluate, refine, and improve their work (Ostroff et al., 2013). Thus, by examining the role of feedback climate, we offer a richer perspective of team members’ interaction, showing that team process innovation can be achieved by leveraging on a climate of continuous improvement and development shared among team members. In doing so, our study contributes to the SIP theory by illustrating how dispersion shapes not only the flow of information, but also the interpretive and reciprocal social processes that underlie team continuous improvement (Rafique et al., 2022). By discussing the importance of feedback climate, we highlight the conditions under which dispersed team members can collectively comprehend of their environment, reinforcing the core SIP premise that meaning is socially constructed through interaction.

Second, our research extends previous literature on team decisions latitude (Greimel et al., 2023) by considering how empowerment represents a pivotal managerial leverage to address the liabilities associated with team members’ dispersion. By bringing the decision-making process closer to the action, team empowerment facilitates the fluidity of team members’ interactions, thus alleviating the negative effects of team members’ dispersion on the team’s ability to engage in feedback behaviors that support continuous development. This evidence is consistent with and complements recent findings underscoring that initiatives enabling higher decision-making latitude to the team are more effective in supporting team members’ interactions in comparison with a centralized approach (e.g., Lunkes et al., 2018). Similarly, our study contributes to the SIP theory by showing that structural mechanisms—such as empowerment—can shape the social interpretive processes central to the SIP theory. By enabling team members to exercise greater autonomy and ownership over their interactions, empowerment reinforces their capacity to actively engage in feedback behaviors, even in dispersed settings. This highlights how organizational design can create conditions that sustain social sense-making and meaning construction, which are foundational to the SIP theory.

Third, our findings advance the theoretical debate by showing that the effects of dispersion on innovation are not deterministic but contingent on contextual enablers such as empowerment. Existing literature has mainly treated dispersion primarily as a structural liability that inherently undermines collaboration and innovation (O’Leary & Cummings, 2007). Our research complements this view by demonstrating that dispersion affects process innovation indirectly through feedback climate, and that this pathway can be substantially weakened when empowerment is high. This contributes to the SIP theory by illustrating how structural features of the team environment shape the way social cues are interpreted and enacted, thereby influencing whether dispersion becomes a barrier or a manageable condition. In doing so, our study shifts the focus from whether dispersed teams can innovate to identifying the conditions under which they are most likely to succeed.

Finally, our study expands the application of the SIP theory beyond the traditional focus on R&D or highly creative domains (e.g., Nieto et al., 2015) by examining process innovation in professional service functions such as accounting. By demonstrating that the feedback climate is equally pivotal for continuous improvement in these more traditional settings, we advance the literature by broadening the scope of the SIP theory to contexts where innovation is less about radical breakthroughs and more about the incremental refinement of processes. In doing so, we highlight that the interpretive and reciprocal social processes emphasized by SIP are fundamental not only for product innovation in high-tech environments but also for sustaining ongoing process innovation across a wider range of organizational domains.

Practical implicationsFrom a practical standpoint, our results offer several insights for managers and organizations. First, our results highlight the importance of intentionally fostering a feedback climate in distributed teams. Organizations should implement practices that encourage employees to give, request, and use feedback collectively. For example, structured feedback rituals can help create a feedback climate in team settings. This managerial recommendation is further substantiated by empirical evidence from previous research on dispersed teams, which indicates that creating an organizational environment enabling digital collaboration is crucial in assisting individuals who operate within geographically dispersed teams (Mikalsen et al., 2021; Johns, 2018).

Second, our results suggest that empowerment represents a crucial managerial lever. Granting teams greater decision latitude not only increases autonomy but also stimulates proactive feedback-seeking and dialogue. Managers should, therefore, adopt leadership practices that delegate authority and responsibility to teams, rather than centralizing decision-making. For instance, managers could involve teams in setting their own performance goals, enabling them to select the digital tools that best fit their needs, or encouraging shared leadership roles (Pearce et al., 2019). In this context, our results warn organizations against the risks of dispersion when not balanced by empowerment. Over-reliance on technology as the sole channel of interaction may isolate individuals and fragment collective sense-making. As suggested by previous studies (Peñarroja et al., 2021), the reliance on technology as a means to communicate could be socially isolating, and the lack of control of team members may enhance the negative effects of such isolation. As such, empowerment stimulates the direct interaction among team members, thus alleviating the negative effects of isolation on the development of a positive climate within the team.

Finally, our findings are particularly insightful for organizations that are willing to rely on a distributed workforce. Our evidence suggests that organizations should not approach dispersed work arrangements in a one-size-fits-all manner. Instead, they should recognize that the success of dispersed teams hinges on contextual enablers—particularly, empowerment and a feedback climate. This implies that distributed workforce models must be accompanied by deliberate cultural and structural interventions, rather than relying solely on technological solutions.

Limitations, and future lines of researchThis study has a few limitations. First, while one of the strengths of our research is the reliance on teams in real work settings, rather than in a lab environment, we have been able to collect our data at one point in time. This design induces the possibility of common-method bias, as participants might have engaged in hypothesis guessing and social desirability when completing the questionnaire (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, this concern is mitigated by adhering to the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2003) by including multiple respondents within each team, and by considering the structural distribution of the team members to assess team dispersion. Future research should adopt longitudinal or multi-wave designs to explore how feedback climate develops over time within dispersed teams. Such studies could offer richer insight into the temporal dynamics of SIP processes, clarifying how feedback climate evolves in response to ongoing collaboration and contextual shifts. This would help establish more robust causal inferences and offer a dynamic view of how teams adapt to dispersion over different project phases.

Moreover, while the manager is often considered a reliable informant for assessing team outcomes, future research would benefit from incorporating objective indicators of process innovation to more accurately capture the magnitude and impact of this phenomenon because it would address perceptual bias. For example, future studies could assess quantifiable improvements in process efficiency that are directly attributable to novel practices or solutions introduced by the team. Additionally, researchers could track implementation timelines for new procedures, as well as the frequency process modifications following team-led initiatives.

From a methodological standpoint, our study focused on teams operating within a single organizational function, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other functional areas. Future research should replicate this study in different functional domains (e.g., marketing, R&D, operations) to assess the extent to which the relations observed hold across varied team contexts. Such efforts would help determine whether the mechanisms identified here are function-specific or more broadly applicable across organizational settings.

Finally, despite controlling for potential confounding variables, it was not feasible to measure all possible factors that might have influenced the between-team dispersion, team-feedback climate, and team-process innovation. We opted for a parsimonious model because of the limited degree of freedom available, given the sample size of 123 teams. However, we believe that developing a parsimonious model that links team dispersion and process innovation through feedback climate could serve as an initial step towards acquiring a deeper understanding of how to effectively support organizations in dealing with the growing phenomenon of dispersed teams. Future research could enrich this framework by incorporating additional mediating and moderating mechanisms rooted in different theoretical frameworks. For instance, concepts such as psychological safety, team identity, or digital communication richness could help explain how dispersed teams maintain or lose effective SIP processes. Similarly, exploring technological affordances (e.g., synchronous vs. asynchronous tools) as moderators may clarify under what conditions digital tools can support or hinder feedback-based learning and development. Indeed, as communication technology functionalities are becoming increasingly sophisticated (Bittner et al., 2021; Kraus et al., 2023), future research should investigate how such technologies could support the exchange of effective feedback among individuals, thus promoting a climate of continuous development despite the dispersion of individuals across different sites. With these considerations in mind, our research makes novel contributions to existing literature and opens new avenues for exploring how organizations can foster team innovation in increasingly dispersed work environments.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMassimo Magni: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Leonardo Caporarello: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Emilia Paolino: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

This paper was developed within the MUSA – Multilayered Urban Sustainability Action – project CUP B43D21011010006, funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU, under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) Mission 4 Component 2 Investment Line 1.5: Strenghtening of research structures and creation of R&D “innovation ecosystems”, set up of “territorial leaders in R&D.

According to Hair et al. (2022), in a reflective measurement model, the latent variable is viewed as the underlying cause of its indicators. Indicators are expected to be interchangeable, highly correlated, and reflective of the same conceptual domain. This model is appropriate when the indicators represent manifestations or effects of a unidimensional construct (e.g., satisfaction, trust, commitment). Conversely, a formative measurement model assumes that the indicators define and compose the construct. Here, the direction of causality flows from the indicators to the construct. Each indicator captures a unique aspect. This approach is suitable when the construct represents a combination of distinct elements (such as the different facets of geographical dispersion). Indeed, the structural and cognitive dimensions represent complementary facets that together form the overall construct of dispersion. This formative specification is consistent with established guidelines for construct modeling (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001) and mirrors recent approaches that advocate for a multidimensional conceptualization of dispersion (e.g., Raghuram et al., 2019) and allows for a nuanced understanding of how both physical and perceptual factors jointly influence team dynamics.

In field research, ICC(1) values as low as .06, and rwg values higher than .70 are considered commonly acceptable thresholds for justifying the aggregation at the team level of analysis (James et al., 1984; Klein & Kozlowski, 2000).