Sustainable fashion consumption can be promoted only by understanding the motivation behind consumers’ decision to purchase sustainable clothing. This study explores the determinants of consumers’ purchasing intentions for two clothing items with different functions, characterized by different levels of visibility and skin contact (underwear and jacket) made with two sustainable materials (biobased and recycled). A conceptual framework was tested using the SEM technique on data collected through a questionnaire administered to 768 Italian consumers. Sustainable fashion knowledge, availability of sustainable garments, influence of celebrities and influencers, and environmental concerns significantly affected purchase intentions for the four product categories investigated. Moreover, gender and age significantly influenced purchase intention. The findings highlighted that purchase intentions and their determinants vary based on the levels of visibility and skin contact associated with the products and the type of sustainable materials used. Several contributions to the theory and managerial implications are provided.

The fashion industry, one of the primary contributors to environmental issues, is responsible for approximately 8–10 % of global CO2 emissions and contributes to high water consumption and pollution (e.g., via chemical pollutants and microplastics released during textile production and clothing use) (Chowdhury et al., 2023; Niinimäki et al., 2020). Fast fashion trends intensify clothing consumption patterns by reducing the lifespan of single clothing items and generating excessive waste, contributing to soil and air pollution (Dissanayake & Sinha, 2015; Ramkumar et al., 2021). Further, the fashion industry has garnered negative attention for its association with child labor and labor exploitation practices within its supply chain Mazotto et al. (2021), Venkatesh et al. (2021). The sustainable development goals must be advanced through immediate action to address the fashion industry’s environmental impact. Current efforts focus on transitioning the industry toward sustainability (European Commission, 2023), with an increasing number of companies shifting production to offer consumers innovative sustainable products (Fung et al., 2021; Madzík et al., 2024; Abbate et al., 2023).

Sustainable fashion has emerged as a new trend (Fuxman et al., 2022), driven by advancements in materials, design, and production processes. Among various eco-design options for clothing, innovative solutions crafted from biobased or recycled materials represent promising sustainability-oriented offerings (Centobelli et al., 2022; Dangelico et al., 2022a). Biobased garments are realized using materials derived from biomass (renewable materials of plant or animal origin), such as lyocell, bioplastics, and eco-leather. Crafting biobased garments mitigates the reliance on heavily polluting fossil-derived materials, offering biodegradable or compostable products at the end of their lifecycle (Schiaroli et al., 2025). Recycled clothes are made from waste (textiles and other waste), including leftover fabrics, old garments’ fibers, plastic bottles, and nylon. Recycling mitigates negative environmental impacts by recovering waste materials, conserving resources, reducing waste, and lessening pollution from disposal (Leal Filho et al., 2019). However, the high prices, limited consumer knowledge, and scarce availability prevent the wide diffusion of and acceptance toward these innovative sustainable garments in the fashion market (Harris et al., 2016; Papamichael et al., 2024). Nevertheless, understanding consumers’ purchase motivation is critical for companies to enhance their sustainable offerings and encourage consumers to choose this kind of product (Apaolaza et al., 2023; Pranta et al., 2024).

Product knowledge, which can significantly impact consumer behavior regarding sustainable fashion, has been recognized as a fundamental driver of sustainable transitions in various industries, influencing consumer decision-making and fostering the acceptance of environmentally responsible products (Bernard et al., 2015; De Canio & Martinelli, 2021; Wang et al., 2019). The fashion industry is no exception, as informed consumers will more likely recognize the benefits of sustainable garments and integrate them into their purchasing decisions (Abrar et al., 2021; Frommeyer et al., 2022). Fashion choices are strongly tied to aesthetics, self-expression, and social identity (Kaiser, 1990; Niinimäki, 2010), and the perceived value of sustainable clothing extends beyond its environmental impact. Without sufficient knowledge, consumers may struggle to assess the quality and benefits of sustainable apparel, hindering its market acceptance (De Koning et al., 2015; Maloney et al., 2014). Consumers’ lack of knowledge about sustainable garments may increase perceived performance risks and lead to negative attitudes toward their attributes (Connell, 2010; Harris et al., 2016; Perry & Chung, 2016). Consequently, consumers might view these garments as less stylish and of lower quality compared to mainstream apparel, associating them with stereotypes such as a “hippie” look, inferior design, lack of special functions, or poor fit (Joy et al., 2012; Moon et al., 2013). Conversely, consumers with a better understanding of sustainability in fashion products perceive these garments as innovative and stylish rather than merely ethical alternatives, demonstrating their willingness to adopt them (Johnstone & Lindh, 2022). Additionally, understandable and clearer information on product attributes and terminology used by fashion firms highlights product differentiation, builds trust in sustainable fashion brands, and promotes purchase behaviors toward sustainable fashion (Feuβ et al., 2022; Byrd & Su, 2021; Dhir et al., 2021), emphasizing the relevance of knowledge in sustainable fashion consumption.

Studies have highlighted how social media channels and the digital environment facilitate the spread of knowledge and awareness about sustainable fashion among consumers (Schiaroli et al., 2024). Within this digital landscape, celebrities and influencers can leverage their credibility and popularity to shape purchasing decisions and encourage sustainable consumption (Khare et al., 2021; Schouten et al., 2020). Celebrities, with their broad media presence, and influencers, through direct engagement with online communities, can raise awareness about sustainable fashion and challenge negative stereotypes associated with it, fostering greater consumer involvement in sustainable fashion products and choices (Djafarova & Foots, 2022; McKeown & Shearer, 2019).

Gap of literature and research questionsRecently, sustainable consumer behavior in the fashion industry has been receiving increasing scholarly attention. Although many studies have explored purchasing decisions for sustainable garments (e.g., Amaral & Spers, 2022), the literature has critical gaps. First, despite its recognized relevance in shaping beliefs and behaviors in the fashion context (Schiaroli et al., 2024), the role of sustainable fashion knowledge (SFK) must be explored comprehensively (Abrar et al., 2021; Bernard et al., 2015). In particular, prior studies have acknowledged that informed consumers are more likely to adopt sustainable products (Frommeyer et al., 2022; Johnstone & Lindh, 2022). However, research has yet to fully address how SFK shapes consumer perceptions and purchase decisions across different sustainable materials and clothing items. Second, regarding the sustainable material studied, most existing research has focused on generic sustainable garments (e.g., Jacobs et al., 2018) or specific sustainable categories, such as organic (e.g., Thompson & Tong, 2016). The literature suggests expanding research to other sustainable categories (Ilmalhaq et al., 2024), especially on biobased garments and innovative recycling solutions (Johnstone & Lindh, 2022). Moreover, the limited research efforts comparing consumers’ perceptions and behavioral intentions toward clothing made with different sustainable materials indicate that relevant differences may be present, emphasizing the need for further exploration in this direction (e.g., Dangelico et al., 2022a; Hong & Kang, 2019; Park & Lin, 2020). Third, while most studies have focused on generic sustainable clothing, only a few have investigated specific items, such as t-shirts (e.g., Sonnenberg et al., 2014). Consumer behavior may vary significantly by clothing type (e.g., Laitala et al., 2012; McNeill et al., 2020), especially regarding purchasing behaviors (e.g., Nassivera et al., 2017; Notaro & Paletto, 2021). Clothing visibility is a key factor in social signaling (Kaiser, 1990). Outerwear, such as jackets, are often chosen for functionality and to align with fashion trends and social expectations, making their appearance and sustainability attributes more noticeable and influential in consumer decisions. Conversely, undergarments, which come into direct contact with sensitive body areas and bodily secretions (e.g., sweat, genital drips), are primarily chosen for comfort, hygiene, and protection (Yu, 2011). Therefore, consumers tend to be more concerned about the safety and quality of the materials used in these clothing items (Magnier et al., 2019; Meng & Leary, 2021). This fact underscores the need to explore sustainable fashion preferences for specific items to comprehend how consumer behaviors differ across garment types (Seo & Kim, 2019). Fourth, the literature suggests extending existing theories to study consumer behavior toward sustainable fashion products (Dhir et al., 2021) by incorporating new variables (Park & Lin, 2020), such as examining how social media influencers and celebrities affect sustainable product promotion (Nekmahmud et al., 2022; Pop et al., 2020), as clothing often reflects self-identity and social affiliation (Khare et al., 2021; O’Cass, 2000). Additionally, the perceived unavailability of sustainable fashion options remains a significant barrier, warranting further study on its impact on purchasing decisions (Kang et al., 2013; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). Environmental concern and awareness are also critical, directly influencing consumers’ openness to adopt sustainable products (Khan et al., 2022), including in the fashion industry (e.g., Abrar et al., 2021; Park & Lin, 2020). Finally, age and gender are essential demographic factors in understanding sustainable fashion behaviors, as they shape consumer preferences and purchasing choices (e.g., Laitala et al., 2021; Lin & Chen, 2022; Rausch et al., 2021).

Thus, this study investigates how the abovementioned factors influence consumers’ purchase intention for garments made of two different types of sustainable materials: biobased and recycled. Furthermore, two distinct garment items related to two opposite levels of visibility and skin contact - underwear and jacket - are selected as product types. Specifically, the paper addresses the following research questions:

- ■

RQ1 – How does prior knowledge on sustainable fashion influence consumer purchase intention for sustainable clothing? Does this effect depend on the type of sustainable material used and clothing item?

- ■

RQ2 - What effect do sustainable garments availability, celebrities and influencers, and environmental concern have on consumer purchase intention for sustainable clothing? Does this effect depend on the type of sustainable material used and clothing item?

- ■

RQ3 – Are there differences in consumer purchase intentions and willingness to pay based on the material used and clothing item?

To answer the research questions, we developed a theoretical model based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) and a questionnaire reporting consumer behavioral intentions to survey a sample of Italian consumers. Four products were investigated: (1) biobased jackets; (2) biobased underwear; (3) recycled jackets; and (4) recycled underwear. With “product category,” we refer to any of the four combinations between material used (biobased or recycled) and clothing item type (jacket or underwear). These two clothing items are different in terms of functions and are characterized by opposite levels of visibility and skin contact, high visibility and low skin contact for jackets, and low visibility and high skin contact for underwear. Consumer behavior was tested in different conditions - specific clothing items in relation to specific sustainable materials. The model was tested using structural equation modeling (SEM), and a robustness check was performed to verify the robustness of the results obtained across the four product categories, following previous studies (Dangelico et al., 2024, 2022a). Additionally, the Friedman test (Friedman, 1937) was performed to compare consumer behavior based on garment visibility, skin contact, and sustainable materials.

Italy was chosen as the study setting due to several reasons. The country is characterized by a strong fashion heritage (Cappelli et al., 2019), is among the top three European spending countries for fashion products (Fashion United, 2022), and is the cradle of some of the most valuable fashion brands worldwide (e.g., Gucci and Prada) (Statista, 2024). Further, the Italian market stands out as a relevant case for sustainable consumption, with studies highlighting commitment among consumers to responsible purchasing behaviors (e.g., Corsini et al., 2024; Dangelico et al., 2021; Rapporto Coop, 2024). The COVID-19 pandemic has further accelerated this shift, increasing awareness and consideration of sustainability in daily consumption choices (Dangelico et al., 2022b). This trend is evident in the fashion industry, where consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable clothing (Dangelico et al., 2022a; Notaro & Paletto, 2021). While cross-country comparisons remain limited, existing studies have suggested that Italian consumer engagement with sustainable fashion varies compared to other markets (e.g., Khan et al., 2024). Thus, contextualizing consumer behavior within specific cultural and industry dynamics is important.

This paper has several elements of novelty. First, while little attention has been given to comparing consumer behavior toward different types of garments, this study compares consumer purchase intention and willingness to pay (WTP) for different innovative sustainable garments categories (garments made using biobased and recycled materials) and clothing items (underwear and jacket). Second, this research enhances the TPB by incorporating additional variables, emphasizing the roles of digital social agents and SFK in promoting sustainable clothing consumption. Third, focusing on the Italian market - one of the foremost entities within the fashion industry - can provide valuable insights applicable in many other contexts.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the theoretical background of the research, and Section 3 details the methodology. Subsequently, Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 discusses the findings. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and lists future research directions and study limitations.

Theoretical background and hypotheses developmentThe theoretical framework for this study is grounded in TPB. This study modifies the TPB model by incorporating new variables, extending the original framework. Such an integration would enable a thorough understanding of sustainable fashion consumption because it adds industry-specific variables into a general model of consumer behavior.

Theoretical backgroundThe TPB, a theoretical model created to predict and explain human behavior (Ajzen, 1991), is widely used in psychological, social, and marketing research to investigate numerous topics, including sustainable purchases (e.g., Baltaci et al., 2024; Judge, Warren-Myers & Paladino, 2019; Kalafatis et al., 1999) and behaviors (e.g., De Leeuw et al., 2015; Fielding et al., 2008; Nguyen, 2024). The TPB model identifies three main components to explain individual intentions to perform a given behavior: attitude (“the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question”); subjective norms (“the perceived social pressure to perform or not to perform the behavior”); perceived behavioral control (“the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior”) (Ajzen, 1991, p. 188). Several studies have validated the effectiveness of these variables in predicting consumers’ behavioral intention toward sustainable products (e.g., Sreen et al., 2018; Yadav & Pathak, 2016). Many scholars have suggested extending the TPB model by adding other variables to boost its predictive power (e.g., Chaturvedi et al., 2020), as done by previous authors (e.g., Pavlou & Fygenson, 2006). In sustainable fashion research, TPB has been used for investigating consumer intentions in its original form (e.g., Han, 2018; Iran et al., 2019) and with extended models (e.g., Becker-Leifhold, 2018; Srivastava et al., 2024).

In this study, to investigate sustainable fashion choice behavior, the three components of the TPB were operationalized as follows. First, “environmental concern” was a proxy for attitude, consistent with previous research (e.g., Alzubaidi et al., 2021; Dangelico et al., 2021). According to Jackson (2005), individuals with strong pro-environmental attitudes are more likely to develop sustainable intentions because their behaviors align with their personal beliefs and sense of moral responsibility. Second, “celebrities’ and influencers’ influence” was a proxy for subjective norms. As Peattie and Belz (2012) suggest, prominent figures can create perceived social pressure to adopt sustainable behaviors, as individuals often model their choices on those they admire or view as societal role models. Celebrities and influencers, specifically, are known to generate this social pressure through their promotional messages (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017; Khare et al., 2021). Third, “sustainable fashion knowledge” and “sustainable garments’ availability” were the control components. Perceived behavioral control is shaped by internal factors (e.g., knowledge and skills) and external factors (e.g., availability and accessibility) (Ajzen, 2002). Within this framework, we consider SFK an internal control factor and sustainable garments’ availability (SGA) an external control factor. Sustainable product knowledge is crucial in making consumer purchase decisions by empowering them with the information necessary for sustainable choices (Bernard et al., 2015; Jackson, 2005; Wang et al., 2019). SGA was recognized as a major determinant of perceived behavioral control, as access to sustainable options in the marketplace significantly influences consumers’ perceived ease of making eco-friendly choices (Peattie & Belz, 2012; Tomić et al., 2016; Verbeke & Vackier, 2005). Finally, we add the demographic variables of gender and age into our model, as these factors are relevant in shaping sustainable fashion consumption behaviors (e.g., Bulut et al., 2017; Confetto et al., 2023; Horrich et al., 2024).

Fig. 1 displays the theoretical model investigated in this paper. The next section presents hypotheses about the relationships depicted in the model.

Hypotheses developmentSustainable fashion knowledgeProduct knowledge can be defined as the amount of information available in consumers’ memory about product features and attributes (Philippe & Ngobo, 1999). Sustainable product knowledge influences the consumers’ decision-making process of purchasing goods (Bernard et al., 2015). If consumers have limited knowledge of the product, their intention to purchase it is reduced (Maloney et al., 2014), and product acceptance can be hindered (De Koning et al., 2015). Conversely, product knowledge reduces the risks associated with a good purchase because the consumer is aware of the quality and benefits of the product (Nekmahmud et al., 2022). Many scholars have employed sustainable product knowledge in their theoretical framework as an antecedent of consumers’ purchase intention, finding a positive effect for several product types, encompassing organic and “clean label” food (Chang & Chen, 2022; Garg et al., 2024), natural cosmetics (Tengli & Srinivasan, 2022), remanufactured products (Singhal et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2013), solar photovoltaic systems (Goodarzi et al., 2021), and green products (Sun & Wang, 2020; Sun et al., 2022). Concerning sustainable fashion, SFK can be defined as the consumers’ information and awareness about the sustainability features of garments and the impacts of their production processes (Khare & Sadachar, 2017; Kim & Damhorst, 1998). Previous studies found positive relationships between SFK and purchasing intention toward sustainable clothing (Abrar et al., 2021; Albloushy & Hiller Connell, 2019; Frommeyer et al., 2022; Su et al., 2019). Furthermore, existing literature substantiates the positive influence of SFK on consumers’ purchase intentions within specific categories of sustainable apparel, particularly organic clothing (Maloney et al., 2014; Sandhya & Mahapatra, 2018). Based on the considerations above, we hypothesize as follows:

H1a:SFK positively influences purchase intention toward sustainable garments.

SFK has proven effective in positively influencing purchase behaviors across various categories of sustainable products (e.g., Frommeyer et al., 2022; Su et al., 2019). While previous research suggests that visibility and skin contact may introduce variations in consumer perception and behaviors (e.g., McNeill et al., 2020; Notaro & Paletto, 2021), these factors are unlikely to alter the fundamental role of knowledge in shaping purchase decisions. Knowledge about sustainable fashion enables consumers to make informed choices across clothing items (Harris et al., 2016; Perry & Chung, 2016), regardless of whether these are visible items (e.g., jackets) or intimate garments (e.g., underwear). Consequently, SFK remains a key driver of sustainable apparel adoption, mitigating perceived risks and reinforcing consumer confidence in sustainable fashion value (Schiaroli et al., 2024). Therefore, we expect its impact to be consistent regardless of the type of garment or material used. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H1b:The effect of SFK on purchase intention is consistent among the four product categories.

Sustainable garments’ availabilityProduct availability can be defined as the consumer’s effortlessness in procuring the product (Chakraborty et al., 2022). The term “perceived availability” indicates if a consumer feels they can easily obtain or consume a certain product (Vermeir & Verbeke, 2008, p. 544). Despite having positive attitudes toward sustainable products, consumers often hesitate to purchase them due to high prices and limited availability (ElHaffar et al., 2020). Buying sustainable items frequently requires consumers to incur additional costs or invest more time and effort (Peattie, 2010). Improving the availability of sustainable products can alleviate these challenges, making it easier for consumers to evaluate options and encouraging them to act on their green attitudes through sustainable purchases (Nguyen et al., 2019; Ottman et al., 2006). The literature highlights the positive effect of product availability on consumers’ purchase intention toward green products (e.g., Tudu & Mishra, 2021; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2008; Walia et al., 2020). Such a positive relationship was also confirmed for specific product types, including sustainable health-related products (Chakraborty et al., 2022) and ethical food products (Oke et al., 2020). In the fashion industry, sustainable fashion is often linked to limited collections and styles (Connell, 2010), while consumers desire a broader selection of sustainable garments (Rausch et al., 2021). Consumers struggle to find sustainable options in traditional stores, facing a limited range of desired attributes (Connell, 2010; Perry & Chung, 2016; Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). This lack of availability discourages sustainable purchases (Tran et al., 2022). Conversely, Ho et al. (2020) found that higher product availability is positively associated with high purchase intention toward sustainable garments, ceteris paribus. Based on the above considerations, we hypothesize as follows:

H2a: Sustainable garments’ availability (SGA) positively influences the consumers’ purchase intention toward sustainable garments.

The market penetration of apparel made from different sustainable materials varies significantly (e.g., comparing the established supply chain for recycled materials with the developing infrastructure for biobased materials) (Textile Exchange, 2023). This discrepancy arises from factors such as the availability and cost of raw materials, technological advancements, consumer demand, and regulatory frameworks, which shape the sustainable fashion market landscape and affect consumers’ perceptions of material availability and product sustainability. The impact of product availability on purchase intentions differs between sustainable and non-sustainable products (Weissmann & Hock, 2022). Extending this concept, the effect of product availability on purchase intention may vary depending on the type of sustainable material. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H2b: The effect of SGA on purchase intention is inconsistent when comparing the same clothing items made with different types of sustainable materials (the effect of SGA on purchase intention depends on the type of material from which the garment is made).

Celebrities’ and influencers’ influenceCelebrities and influencers can be viewed as individuals who enjoy popular recognition in the community and influence others (Khare et al., 2021). Celebrities, including actors, supermodels, and athletes, can leverage their popularity and use multiple media channels to spread messages across the populace (Schouten et al., 2020). Influencers create a personal brand on social media and disseminate information to their followers’ networks (Khamis et al., 2017). Currently, many companies are appointing celebrities and influencers as brand ambassadors because people consider them a reliable source of information (De Veirman et al., 2017; Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017). Thus, celebrities and influencers can influence the consumers’ purchasing process (Belanche et al., 2021). Online celebrities’ performances can intensify consumers’ purchase intention toward several product types recommended (Meng et al., 2021). In the context of sustainable consumer behavior, influencers’ recommendations enable ethical purchases among GenZ consumers (Djafarova & Foots, 2022). Murwaningtyas et al. (2020) found a positive impact of celebrities’ trustworthiness, expertise, and attractiveness on consumers’ purchase intention via Instagram toward organic cosmetics. Regarding the fashion industry, celebrities and influencers can enhance the consumer acceptance of new fashion products (e.g., biobased or recycled textile) by acting like fashion opinion leaders (Saleem et al., 2014). Certainly, a fashion leader who promotes a given product increases the chance of the product spreading on the market swiftly, as in the case of Emma Watson’s sustainable promotion during the Oscar (2018) (Mohr et al., 2022). Social media positively influences consumers’ purchase intentions for sustainable fashion (e.g., Kautish & Khare, 2022). Johnstone and Lindh (2022) found that influencers and celebrities significantly impact European millennials’ online fashion consumption, enhancing their purchase intentions and reinforcing the link between corporate social responsibility communication and buying behavior. Additionally, Khare et al. (2021) demonstrated that celebrities promote sustainable clothing purchases among Indian consumers by increasing their involvement with sustainable fashion. Based on the above-mentioned reasons, we hypothesized as follows:

H3a: Celebrities’ and influencers’ influence (CII) positively affects the consumers’ purchase intention toward sustainable garments.

Owing to the unique characteristics of sustainable fashion products, which are considered high-involvement items and serve as forms of personal expression (O’Cass, 2000), the influence of celebrities and influencers may vary according to the garment’s visibility. The higher visibility of a garment enhances its capacity to convey the consumer’s identity in social settings, likely increasing the effect of celebrities and online influencers on purchasing decisions. Therefore, the degree of visibility may significantly influence how this variable affects consumer behavior. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H3b: The effect of CII on purchase intention is inconsistent when comparing different types of clothing items made with the same material (the effect of CII on purchase intention depends on the level of visibility and skin contact of the garment).

Environmental concernEnvironmental concern (EC) can be defined as “the degree to which consumers are concerned about environmental problems and support efforts to solve them” (Dunlap & Jones, 2002, p. 485). It has received extensive attention from scholars as a relevant predictor of customers’ green purchasing (Testa et al., 2021) because it is critical in the consumer decision-making process (Diamantopoulos et al., 2003). Scholars have defined environmentally concerned consumers as “people who hold strong positive attitudes toward preserving the environment” (Crosby et al., 1981, p. 20–21). EC can be conceptualized as a consumer’s attitudinal beliefs (e.g., Lee, 2011). According to the literature, a high level of EC may be directly associated with a high level of purchase intention and WTP for sustainable products (e.g., Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Shetzer et al., 1991). The positive effect of EC on purchase intention has been highlighted for numerous sustainable products, such as electric vehicles (He et al., 2018,; 2017; Wang et al., 2021), organic (Saleki et al., 2019) and fair trade (Konuk, 2019) food, and recycled products (t-shirt, mobile phone, and toilet paper) (Dobbelstein & Lochner, 2023). Regarding sustainable fashion, several studies found that EC positively influences purchases (e.g., Sobuj et al., 2021). Notably, it enhances purchase intentions for various product types, including organic (Yoo et al., 2013), second-hand (Cervellon et al., 2012), biobased (Dangelico et al., 2022a), and recycled (Park & Lin, 2020) garments. Based on the considerations above, we hypothesize as follows:

H4a: EC positively influences the consumers’ purchase intention toward sustainable garments.

As EC has proven effective in positively influencing purchase behaviors across various categories of sustainable products, we expect its impact to be consistent regardless of the type of garment or material used. Thus, we hypothesize as follows:

H4b: The effect of EC on purchase intention is consistent among the four product categories.

Gender and ageNumerous studies indicate that consumer behavior varies significantly based on demographic characteristics, such as gender and age (e.g., Bulut et al., 2017). Concerning gender, sustainable consumption research suggests that women are generally more inclined than men to engage in environmentally friendly behaviors (e.g., Brough et al., 2016; Horrich et al., 2024), influenced by cultural and societal factors that foster prosocial behavior and altruism (Chwialkowska et al., 2020; Lee & Holden, 1999). This trend is evident in the fashion industry, where women are more likely to consider sustainability in their purchasing decisions (e.g., Baier et al., 2020; Rausch et al., 2021) and engage in sustainable use and disposal practices (e.g., Laitala et al., 2021; Nenckova et al., 2020). Regarding age, younger generations, raised in an era marked by an increased awareness of environmental challenges and sustainability, will likely prioritize these values more in their purchasing decisions, compared to older generations, who may have different priorities or less exposure to sustainability issues during their formative years (Confetto et al., 2023; Dabija et al., 2019). Younger consumers are more environmentally conscious and eager to adopt sustainable lifestyles (Djafarova & Foots, 2022; Yamane & Kaneko, 2021), a trend reflected in their fashion consumption choices (e.g., Liang & Xu, 2018; Lin & Chen, 2022; McNeill & Venter, 2019). Understanding these demographic differences is crucial for predicting consumer behavior in the sustainable product market. Based on the above considerations, we hypothesize as follows:

H5a:Gender negatively influences purchase intention toward sustainable garments - men are less likely to choose sustainable garments compared to women.

H6a:Age negatively influences purchase intention toward sustainable garments - young consumers are more likely to choose sustainable garments compared to old consumers.

Further, we expect these relationships to be consistent regardless of the type of garment or material used. The preference for sustainability in consumption is not confined to a specific product category but embodies a general principle that extends to various types of consumption or lifestyle (Lubowiecki-Vikuk et al., 2021; Moisander, 2007). These more environmentally responsible consumer groups - women and young people - might choose sustainable products irrespective of the product category. Consequently, the focus on sustainability and interest in sustainable materials can transcend product-specific differences, applying equally to visible items, such as jackets, and intimate garments, including underwear, as sustainability is a cross-product characteristic. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5b:The effect of gender on purchase intention is consistent among the four product categories.

H6b:The effect of age on purchase intention is consistent among the four product categories.

Sustainable materials and clothing itemsGarments can be made more sustainable through several options (Schiaroli et al., 2025). Innovative solutions crafted from biobased and recycled materials are becoming increasingly common in the fashion industry, contributing to a growing market presence for sustainable garments (Statista, 2022). As sustainable materials have gained prominence, researchers focus on the factors influencing consumer intentions and behaviors, noting that consumer choices can vary significantly based on the visibility and material type of the garments (e.g., Dangelico et al., 2022a; Notaro & Paletto, 2021). As clothing is a high-involvement product that communicates personal style and identity, the visibility of sustainable garments is particularly relevant to consumers (O’Cass, 2000). Social approval and external influence can reinforce sustainable behaviors, especially for visible items, often subject to social scrutiny (Peattie & Belz, 2012). High-visibility sustainable items allow consumers to express environmental values, integrating sustainability into their identity (Jackson, 2005). Therefore, social pressure might have an irrelevant effect on purchasing behaviors of garments with low visibility; alternatively, consumers highly interested in fashion might be more willing to buy garments with high visibility (e.g., jackets) compared to those with lower visibility (e.g., underwear). The material used in sustainable garments also shapes consumer behavior. Consumers’ perceptions and behavioral intentions may vary based on sustainable materials (Hong & Kang, 2019; Kumagai, 2020; Park & Lin, 2020). Some consumers perceive risks associated with recycled materials, particularly for items with high skin contact (e.g., underwear), due to contamination concerns (Kim et al., 2021; Magnier et al., 2019; Meng & Leary, 2021). Additionally, perceptions of quality can differ depending on the material’s origin; for instance, recycled fabrics are sometimes considered lower in quality or durability than new fibers, influencing consumption choices (Hamzaoui Essoussi & Linton, 2010; Newman et al., 2014). Therefore, sustainable materials and clothing items may affect consumers’ behavior. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H7a:Consumers’ behavioral intentions (purchase intention and willingness to pay) toward sustainable fashion are affected by the type of clothing item.

H7b:Consumers’ behavioral intentions (purchase intention and willingness to pay) toward sustainable fashion are affected by the sustainable material used.

MethodologyData collection and sampleData were collected through an online survey using a questionnaire. All scales were drawn from previous research and adjusted for the fashion context (Table A1). For each question, a five-point Likert scale was used from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree.” The environmental concern (EC) scale comprised three items (D’Souza et al., 2015), the CII scale consisted of six items (Johnstone & Lindh, 2022), the SGA scale comprised three items (Singh & Verma, 2017), the SFK scale had four items (O’cass, 2004), and the purchase intention (PI) scale had three items (Sweeney et al., 1999). WTP was assessed through one item, and respondents could use a slider to indicate their WTP more for a sustainable item of clothing from “0 %” to “100 %” more.

The questionnaire was divided into four sections: (i). questions about EC and CII; (ii) questions on biobased garments; (iii) questions about recycled garments; (iv) questions on the demographic characteristics of consumers: gender (a dummy variable coded as 0 for female and 1 for m”ale), age (from 1 = “18–24” to 6 = “over 65”), net month income (from 1 = “less than EUR 1000” to 6 = “over EUR 3000”), and education (from 1 = “Primary” to 6 = “PhD”). A brief description of the meaning of biobased garments and recycled garments was provided at the beginning of the second and the third sections, respectively. Questions related to product knowledge, SGA, purchase intention, and WTP were repeated for the two sustainable materials. Furthermore, questions related to the intention to purchase and the WTP premium price were repeated for the two clothing items: jacket and underwear. As the survey was distributed among Italian consumers, the questionnaire scales were translated into Italian with the support of a language expert. Similar to the practice in consumer behavior studies, a convenience sampling approach was used (Kim & Lennon, 2013; Yadav & Pathak, 2017). The questionnaire was created using Qualtrics and distributed online via instant messaging and social networks in Italy from March to September 2023. All questions were mandatory, requiring respondents to answer each one before proceeding. Consequently, only fully completed responses were collected, with no missing data. A sample of 768 Italian consumers was collected. Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

SPSS 26 and AMOS 26 were used for data analysis. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the measurement models. Subsequently, structural equation modeling (SEM) technique was employed to test the structural models (H1a, H2a, H3a, H4a, H5a, and H6a). The statistical analyses were first performed for the biobased jacket product category. Further, as a robustness check for the obtained results and to test H1b, H2b, H3b, H4b, H5b, and H6b, the same analysis was performed using scales pertaining to the other product categories - biobased underwear, recycled jacket, and recycled underwear. Owing to the large sample size and the sensitivity of the chi-square (χ²) statistic to sample size, several additional indices were employed to evaluate the overall model fit (Bagozzi, 2010): the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the global fit index (GFI), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SMRS). Finally, the Friedman test (Friedman, 1937) was used to compare consumers’ purchase intention and WTP for the four products under investigation to test H7a and H7b.

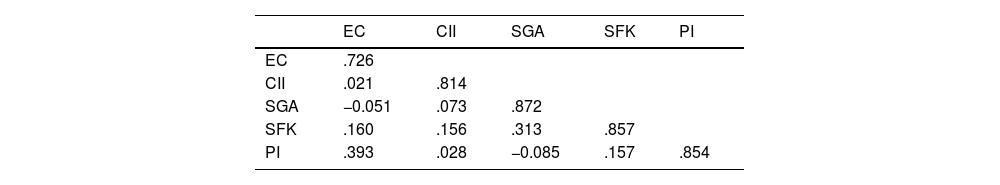

Results and discussionMeasurement modelsCFA was used to test the measurement model. This model included five multi-item scales (EC, CII, SGA, SFK, and PI). As the standardized factor loading of the fifth and sixth items of the CII construct were less than 0.5 for all product categories, these items were dropped from the scale. Referring to the biobased jacket, the measurement models showed adequate model fit, with a χ²/df ratio of 3699 (p = 0.000) - the model aligned well with the data (Mulaik et al., 1989). Given the chi-square statistic’s sensitivity to large sample sizes, additional fit indices (CFI, TLI, GFI, RMSEA, and SRMR) were calculated to enhance reliability. These indices met or exceeded recommended thresholds (CFI = 0.963, TLI = 0.953, and GFI = 0.940), affirming a solid model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1998). RMSEA = 0.059 and SRMR = 0.0410 values are below or close to 0.05, reflecting a good fit (MacCallum et al., 1996). The reliability and convergent validity of each construct were evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2006). Table 2 shows that all factors have Cronbach’s alpha above 0.75 and standardized factor loadings exceeding 0.50. CR values for each dimension range from 0.7 to 0.9, and each construct surpasses the 0.5 threshold for AVE. Consequently, each construct exhibited good levels of convergent validity and reliability.

Confirmatory factor analysis for the measurement model (biobased jacket).

Model fit: χ² = 403.220 df = 109 p = 0.000; CFI = 0.963; TLI = 0.953; GFI = 0.940; RMSA = 0.059; SRMR = 0.041.

We used the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion to assess discriminant validity. Table 3 shows the correlation matrix and AVE values for each construct. According to this criterion, the square root of each construct’s AVE was higher than its correlations with other constructs, confirming discriminant validity across the measurement model.

We applied this same procedure to the other three product categories. The validation results for the measurement models are presented in Tables A2 through A7 in the Appendix.

Hypotheses testingTo test the structural model, the hypothesized paths were added. First, the biobased jacket model was tested (Table 4). The structural model displayed a good model fit. Four out of the six hypotheses were supported. The results confirmed the positive influence of SFK and EC on purchase intention, and women and younger respondents were more likely to purchase sustainable fashion. Thus, H1a, H4a, H5a, and H6a were supported. Conversely, results related to the impact of SGA and CII on purchase intention reported results contrasting with the hypotheses. The relationships were found to be significant but negative. Hence, H2a and H3a were not supported.

Structural model results (Biobased Jacket).

Model fit: χ² = 534.770; df = 133; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.951; TLI = 0.937; GFI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.0630; SRMR = 0.0412.

The same structural models tested for the biobased jacket were also tested for the other product categories to verify the consistency of results across the categories (Dangelico et al., 2022a, 2024). The structural model was evaluated for biobased underwear (Table 5), recycled jackets (Table 6), and recycled underwear (Table 7), showing a good model fit across all sustainable clothing categories.

Structural model results (Biobased Underwear).

Model fit: χ² = 520.354; df = 133; p: 0.000; CFI = 0.953; TLI = 0.939; GFI = 0.930; RMSEA = 0.0620; SRMR = 0.0394.

Structural model results (Recycled Jacket).

Model fit: χ² = 518.630; df = 133; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.960; TLI = 0.948; GFI = 0.930; RMSEA = 0.0610; SRMR = 0.0385.

Structural model results (Recycled Underwear).

Model fit: χ² = 487.172; df = 133; p = 0.000; CFI = 0.964; TLI = 0.954; GFI = 0.934; RMSEA = 0.0590; SRMR = 0.0342.

In Table 8, the results of hypothesis testing are reported for each of the four types of sustainable clothing analyzed in this study. Two hypothesized relationships are robust across all the sustainable fashion categories. Specifically, H4a and H6a were supported for all four products investigated. Indeed, the results demonstrated consistency in the impact of EC and Age on PI across materials and clothing types. Therefore, H4a, H4b, H6a, and H6b were fully supported. Results confirmed the positive impact of SFK on purchase intention (H1a) for all the products considered, except for recycled underwear (although the p-value is very close to significance), demonstrating only a partial consistency across the same garment type and the same material. Thus, H1a and H1b were partially supported. The negative impact of gender on purchase intention (H5a) was confirmed for the two jackets, while the impacts were not significant for the two underwear, showing inconsistency across different garment types; H5a and H5b were partially supported. Conversely, the impacts of SGA (H2a) and CII (H3a) on purchase intention were found to be negative or not significant, rejecting both the hypothesized paths. Hence, H2a and H3a were not supported. Nonetheless, the impact of SGA on purchase intention was inconsistent across the same clothing items made with different types of sustainable materials, supporting H2b. Similarly, results showed that the impact of CII on purchase intention was inconsistent across different types of clothing items made with the same materials, supporting H3b.

Summary of hypotheses testing (H1–H6).

“B U” = biobased underwear; “B J” = biobased jackets; “R U” = recycled underwear; “R J” = recycled jackets; “+” stands for a positive impact, “-” stands for a negative impact, “N.S.” stands for a non-significant impact.

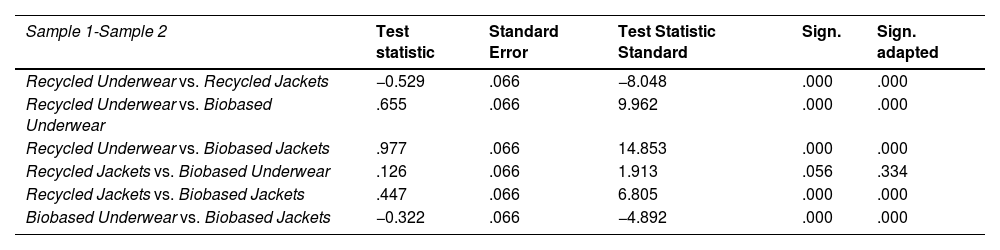

The results of the Friedman test (Friedman, 1937) showed that differences in consumer’s purchase intention and WTP among the four sustainable product categories investigated do exist, supporting H7a and H7b (Tables 9 and 10). Concerning purchase intentions for sustainable fashion products, the results showed that consumers have higher purchase intentions for jackets compared to underwear for the recycled material category and that they have higher purchase intentions for the biobased version of the Underwear. Concerning the sustainable material used, the results on the WTP indicated that consumers were more willing to pay for the biobased version of the same clothing item. Additionally, with equal material, consumers were more willing to pay for jackets compared to underwear. The complete results of the test are available in the Appendix (Tables A8 and A9).

This study evaluates the influence of SFK, SGA, CII, EC, and two demographic variables (gender and age) on consumers’ purchase intentions of sustainable fashion products. This study examines four categories of sustainable fashion products to assess whether the factors influencing consumer behavior are consistent across different product types (RQ1 and RQ2). Additionally, it compares the effects of sustainable material types (biobased vs. recycled) and the clothing item’s types (jacket vs. underwear) on purchase intention and WTP (RQ3).

With regard to RQ1, SFK positively influenced consumers’ purchase intention for sustainable fashion, consistent with extant studies (e.g., Abrar et al., 2021; Frommeyer et al., 2022; Su et al., 2019). When consumers are well-informed about sustainable clothing, their intention to purchase these products increases. SFK mitigates skepticism and negative attitudes toward sustainable fashion by enhancing consumers’ understanding of its quality and value (Schiaroli et al., 2024), attributes highly relevant to fashion consumption (Joy et al., 2012; Moon et al., 2013). This aligns with broader research on sustainable consumption, where product knowledge has been shown to reduce perceived risks, enhance trust, and increase consumer confidence in purchasing decisions (Maloney et al., 2014; Nekmahmud et al., 2022).

The results showed consistency across all sustainable fashion garments analyzed, except for recycled underwear. The non-significant result for recycled underwear may be due to its limited market representation and low penetration, potentially influenced by perceived contamination risks (Magnier et al., 2019; Meng & Leary, 2021). This limited exposure could undermine the impact of SFK on purchase intention. This result reflects the unique consumer behavior associated with the specific combination of sustainable material and clothing items - intimate apparel made from recycled materials. Thus, while SFK remains a key driver of sustainable fashion adoption, its influence may be reduced in categories where functional and safety attributes take precedence over sustainability considerations. Nevertheless, our results highlighted the pivotal role of SFK in facilitating informed and rational consumption decisions among consumers.

Regarding RQ2, the results indicated that EC is a key driver of purchase intention for sustainable fashion products, aligning with prior research on sustainable consumer behavior (e.g., Saleki et al., 2019) and sustainable fashion (e.g., Fu & Kim, 2019; Park & Lin, 2020). Environmentally concerned consumers showed a higher propensity to buy sustainable fashion, a trend consistent across all product categories studied, underscoring EC’s critical role in stimulating sustainable purchasing decisions. CII had a negative influence on purchase intention, contrary to previous studies’ findings (e.g., Khare et al., 2021). The results showed inconsistency across different product types, negative effects for the high visibility products (jackets), and no significant effect for low visibility ones (underwear). These results can be explained by the fact that the influence of celebrities and influencers could be less effective or even counterproductive if perceived as overly commercial or inauthentic (e.g., Martínez-López et al., 2020). The literature demonstrates how the perception of authenticity, trustworthiness, and credibility are fundamental characteristics for the effectiveness of the endorsement of celebrities and influencers (Johnstone & Lindh, 2022; Lee et al., 2022; Santos et al., 2019). For high-visibility products (e.g., jackets), expectations regarding their sustainability and ethicality may be elevated. If these expectations are not met, such as when celebrities and influencers are perceived as lacking credibility or not aligning with ecological values in the realm of sustainability, their influence on purchase intention can become negative. Nevertheless, the results confirmed that for high-visibility products, CII is relevant in consumers’ purchasing choices (negatively in our case). For low-visibility products (e.g., underwear), consumers may perceive these products as less important in the expression of their style, considering the influence of celebrities and influencers irrelevant. SGA negatively impacted purchase intention for sustainable fashion products, contrary to existing literature (e.g., Ho et al., 2020; Tran et al., 2022). The results showed inconsistency across different materials, with a negative effect observed for biobased garments and no significant effect for recycled ones. These results may stem from their market presence (Textile Exchange, 2023). Recycled garments are widely available and familiar to consumers, making SGA less relevant. Conversely, biobased garments might be perceived as less available in the market and associated with exclusivity and uniqueness. This perception likely drives consumers to purchase biobased garments to distinguish and express themselves. Our results highlighted the importance of perceived availability in shaping purchase intention for different sustainable materials.

Concerning the role of demographic variables, gender and age influenced purchase intention. It is found to have a negative influence of gender on purchase intention - women have higher purchase intention compared to men. This finding supports existing literature (e.g., Baier et al., 2020; Rausch et al., 2021). The results showed inconsistency across different product types, confirming this relationship for the high visibility products (jackets) and reporting no significance for low visibility ones (underwear). These results may be attributed to women’s tendency to use fashion as a means of social signaling. High-visibility products enable a greater expression of personal style and status, which can be particularly influential for female consumers. Women might perceive these products as enhancing their image and social standing. This inclination toward using fashion for social and self-expressive purposes underscores the higher purchase intentions for high-visibility products among women. According to the results, the younger the consumer, the higher the PI, supporting previous research findings highlighting that the younger generations are more prone to choose sustainable fashion products (e.g., Liang & Xu, 2018; Lin & Chen, 2022). The results showed consistency across all the sustainable product categories investigated, confirming how young consumers are instrumental in the transition toward sustainable consumption models.

Finally, regarding RQ3, the results of this study showed that the consumers’ purchase intention and WTP may vary based on the clothing item and the sustainable material. This is in accordance with previous literature, which highlighted differences in consumer behavior among different clothing items (e.g., McNeill et al., 2020) or sustainable materials (e.g., Dangelico et al., 2022a). Consumers are prone to spend more money for biobased fashion products. These results might have multiple explanations. Consumers might perceive that recycled clothing has a lower quality and a heightened risk of associated contamination, contrary to their biobased counterparts. Consumers might also believe that biobased materials offer greater environmental benefits than recycled ones, enhancing their perceived value. Additionally, as biobased garments have relatively lower market availability, these products may be considered exclusive, as previously discussed. Concerning clothing items, the visibility of the item affects the consumption decision, with consumers expressing higher WTP and intention to purchase jackets compared to underwear. This could be related to the extrinsic characteristics of clothing, as these products help express identity and status. Furthermore, based on the results on the underwear items (characterized by high skin contact), the type of sustainable material affects consumer behavioral intention. Consumers might perceive a higher risk linked to the contact of recycled materials with intimate parts compared to biobased materials. These results suggested that the role of specific product characteristics (e.g., sustainable material used and clothing item) were critical in sustainable consumption and that considering generic sustainable clothing items without providing detailed information about their characteristics can be misleading in studies on consumer behavior.

Conclusion, implications, and future research directionsThe findings of this study reinforce key insights from existing research and add new perspectives on sustainable fashion consumption. These results offer several noteworthy implications for theory and practice.

From a theoretical perspective, this paper has several elements of novelty compared to the extant literature. First, this study contributes to sustainable consumer behavior literature, reinforcing the pivotal role of SFK in shaping consumer purchasing behavior. By demonstrating its generally positive effect across different garment categories, our findings suggest that SFK is an important determinant of purchase intention, although its impact may be reduced for clothing items where functional and safety aspects outweigh sustainability concerns. Second, the study compares consumer preferences across different sustainable materials (biobased vs. recycled) and garment types (jackets vs. underwear). Given the limited attention to comparative consumer behavior across different types of sustainable garments, this focus allows for a better understanding of consumer beliefs and purchase intentions related to distinct sustainable materials. Future research could expand on this by comparing products within the same material category (e.g., recycled garments) sourced from different materials, such as textile versus plastic waste, or by investigating specific materials like Tencel versus Econyl to highlight unique consumer responses. Third, this paper highlights the role of clothing items (jackets and underwear) in influencing sustainable consumer behavioral intention, addressing an underexplored area. The findings suggest that product functions are critical in shaping sustainable purchase behaviors, especially for items worn publicly versus privately. This distinction underscores how sustainability attributes may be perceived differently depending on the garment’s purpose, contributing to a deeper understanding of sustainable fashion consumption patterns. Future research should explore this area by examining a broader range of clothing categories and their unique influence on consumer behavior. Fourth, this study extends the TPB by integrating fashion-specific factors into the general model. This framework may be employed for future studies on consumer behavior in the fashion industry to explore additional contexts. Our results underscore the significance of key determinants in shaping sustainable fashion consumption. This contributes to the literature on sustainable fashion by revealing insights that warrant further exploration, especially the roles of CII and SGA, which showed divergence from existing findings. Fifth, this research is focused on the Italian market, a global leader in fashion, providing insights that could be highly relevant to other fashion-forward markets worldwide.

From a managerial perspective, this research provides several insights for sustainable fashion marketers. Fashion companies should leverage our findings in formulating sustainable product marketing strategies. First, SFK is significant in shaping consumer behavior. Marketers should invest in educational initiatives, such as sustainability reports, blogs, videos, and infographics, to enhance consumers’ understanding of the benefits and features of sustainable products. Companies should improve product transparency through digital product passports and certifications to build consumer trust. Providing clear, accessible, and verifiable information on product sustainability directly on labels and packaging can further reinforce consumer confidence and reduce skepticism. Eco-labeling and third-party certifications should be prominently displayed to signal credibility and ensure that consumers can easily differentiate sustainable garments from conventional alternatives. These actions align with recent European policy guidance - the European Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles (European Commission, 2023) - to enhance transparency and traceability within the fashion industry. Strengthening regulatory frameworks that mandate clearer sustainability disclosures supports informed consumer choices and drives the transition toward more sustainable consumption patterns. Additionally, public campaigns to increase general consumer awareness of sustainable fashion should be promoted, reinforcing the link between knowledge and purchasing behavior. Second, marketing campaigns should emphasize environmental aspects and the sustainability of materials. Consumer segments can be identified based on their sensitivity to environmental issues, and those with higher sensitivity should be specifically targeted. Third, marketers aiming to promote biobased clothing should capitalize on the perceived scarcity of availability as a strategic advantage. Companies should position limited availability as a marker of exclusivity and value by emphasizing the unique benefits and features of biobased clothing in marketing communications. Fourth, based on demographic insights, campaigns should target younger consumers and women. For women, emphasizing the prestige and status-enhancing qualities of high-visibility sustainable fashion items, such as limited-edition collections, can increase appeal. Loyalty programs and discounts should also be designed to incentivize purchases. Companies could offer discounts or rewards for sustainable purchases to encourage younger, generally high-price-sensitive. Additionally, to raise awareness and generate interest, they should collaborate with schools, colleges, and universities to organize workshops and seminars promoting sustainable fashion. Finally, the study’s comparison of two distinct items of clothing made from two specific sustainable materials offers valuable insights into how product visibility, skin contact, and material type affect consumer behavior. Marketers should tailor their strategies for different sustainable garments based on the preferences and behaviors identified among consumers. For instance, companies ought to undertake measures to shift consumer perceptions about recycled products, making them more attractive in terms of quality and style.

This study has certain limitations. This study conceptualizes SFK in terms of familiarity, depth of knowledge, user experience, and expertise. However, a more comprehensive assessment of consumer SFK could be explored in future research, incorporating dimensions, such as the use of sustainable materials, ethical labor practices, waste reduction, and other circular economy principles. Notably, this study does not account for the specific traits and attributes of celebrities and influencers, such as their trustworthiness, expertise, and attractiveness. Future research could enhance our model by incorporating these variables into the analysis of celebrities and influencers, providing a more comprehensive understanding of their impact on consumer behavior. Another limitation of this study is the sample used, which is not fully representative of the Italian population and is mainly composed of female respondents. This may have influenced the results because women are generally more prone to sustainable consumption behaviors, ceteris paribus (e.g., Brough et al., 2016; Horrich et al., 2024). Therefore, caution should be taken when generalizing the findings to the broader population. Additionally, this study was conducted within a single country. While Italy’s prominent role in the fashion market provides valuable insights, it may restrict the generalizability of the results. Research should be conducted in other countries to investigate whether and how the findings vary across different national cultural contexts.

This study is expected to prompt further interest and efforts of the academic and practitioners’ communities to reduce the impact of the fashion industry and foster sustainable consumption behavior within this industry (Tables A3-A6 in the Appendix).

CRediT authorship contribution statementValerio Schiaroli: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Rosa Maria Dangelico: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. Luca Fraccascia: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

None

The authors would like to thank Ivan Coramusi, Chiara Favuzzi, and Stefano Signore for their support in data collection.

Rosa Maria Dangelico acknowledges the support provided by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3 - Call for tender No. 341 of 15/03/2022 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union - NextGenerationEU. Award Number: PE00000004, Concession Decree No. 1551 of 11/10/2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP D93C22000920001, MICS (Made in Italy - Circular and Sustainable).

Luca Fraccascia acknowledges the support provided by Sapienza University of Rome within the project “Propensione dei Consumatori verso Prodotti da Simbiosi Industriale”.

The questionnaire.

| Variable | Reference |

|---|---|

| Environmental ConcernEC1 - I am very concerned about the environment.EC2 - I would be willing to reduce or change my consumption to help protect the environment.EC3 - Protecting the natural environment increases my quality of life. | (D’Souza et al., 2015) |

| Celebrities’ and Influencers’ InfluenceCII1 - I follow various celebrities. bloggers and/or influencers online.CII2 - The relationship I have with a social media influencer (e.g., a celebrity or blogger) informs my fashion choices.CII3 - The ability to exchange information on fashion garments with a social media influencer is important to me.CII4 - I am more likely to buy a product if an online influencer reviews it positively.CII5 - Being part of an online community is important to me.CII6 - Connecting with people online who have similar values is important to me. | (Johnstone & Lindh, 2022) |

| Sustainable Garments’ AvailabilitySGA1 - Biobased/Recycled garments are easily obtained in the market.SGA2 - It is easy to find biobased/recycled garments.SGA3 - It is easy to have access to biobased/recycled garments. | Adapted from (Singh & Verma, 2017) |

| Sustainable Fashion KnowledgeSFK1 - I am very familiar with clothing made from biobased/recycled material.SFK2 - I feel I know a lot about clothing made from biobased/recycled material.SFK3 - I am an experienced user of clothing made from biobased/recycled material.SFK4 - I would classify myself as an expert on biobased/recycled textiles. | Adapted from (O’cass, 2004) |

| Purchase IntentionPI1 - I would consider buying underwear/jackets made from biobased/recycled material.PI2 - I am willing to purchase underwear/jackets made from biobased/recycled material.PI3 - There is a strong likelihood that I will buy underwear/jackets made from biobased/recycled material. | Adapted from (Sweeney et al., 1999) |

| Willingness to payWTP - How much more are you willing to pay for underwear/jackets made from biobased/recycled material compared to traditional garments? | Adapted from (Dangelico et al., 2021) |

Confirmatory factor analysis for the measurement model (biobased underwear).

Model fit: χ² = 386.316 df = 109 p = 0.000; CFI = 0.965; TLI = 0.956; GFI = 0.942; RMSA = 0.058; SRMR = 0.039.

Confirmatory factor analysis for the measurement model (recycled jackets).

Model fit: χ² = 417.416 df = 109 p = 0.000; CFI = 0.967; TLI = 0.958; GFI = 0.935; RMSA = 0.061; SRMR = 0.039.

Confirmatory factor analysis for the measurement model (recycled underwear).

Model fit: χ² = 388.368 df = 109 p = 0.000; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.963; GFI = 0.939; RMSA = 0.058; SRMR = 0.034.

Friedman test results (pairwise comparison of purchase intentions).

Significance values were adjusted based on the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.

Friedman test results (pairwise comparison of willingness to pay).

Significance values were adjusted based on the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests.