Research on consumer interactions with artificial intelligence (AI)-powered voice assistants (VAs) in ecotourism is limited. Grounded in expectation confirmation theory and the post-acceptance model of information systems (IS) continuance, this study explores how VAs influence family ecotourism behavior throughout the tourism customer journey, from decision-making to ecotourism loyalty. The conceptual model introduces the novel concept of family ecotourism engagement, which is tested as a mediator of the relationship between family ecotourism satisfaction and loyalty. For the data, 205 parents who traveled with children to Romanian ecotourism destinations completed online surveys in a three-stage data collection process, pre-, in-, and post-visit. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) were combined in a mixed-methods approach. A key symmetric finding is that VA-driven family ecotourism engagement is likely to mediate the relationship between family ecotourism satisfaction and loyalty. This finding extends research on ecotourism behavior. Asymmetric findings reveal that VA expectations are the most important predictor of family ecotourism loyalty. The study provides practical insights for potential partnerships between key stakeholders to design VAs tailored to ecotourism destinations.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly applied in the form of voice assistants (VAs). These tools rely on speech recognition systems to process human voice inputs and generate logical outputs (Buhalis & Moldavska, 2022). Text-to-speech, natural language processing, and automatic speech recognition are core components of conversational AI. VAs are essentially speech-recognition-based virtual service robots (Wirtz et al., 2018). Unlike traditional touchscreens or remote controls, users operate VAs through speech commands, enabling a more natural form of human–machine interaction. Apple Siri, Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, and Microsoft Cortana are well-known VAs. Thanks to these VAs, users can complete voice-activated, hands-free tasks such as calendar management, daily information retrieval, and smart home device control in a convenient and user-friendly way (Hoy, 2018; Moriuchi, 2019).

Studies have emphasized the role of VAs in tourism, from trip planning to post-visit feedback, thus spanning the entire customer journey (Phaosathianphan & Leelasantitham, 2021). Before vacations, tourists use VAs to search for tailored services, including ecotourism destinations (Li et al., 2024). As explained by Orden-Mejía and Huertas (2022), VAs also help tourists form mental images of destinations before their arrival, with VAs functioning similarly to interactive chatbots and AI-driven assistants. During vacations, VAs support tourists by providing on-site orientation, translation tools, and suggestions for local tourism activities, thereby offering tourists more immersive and comfortable travel experiences (Tussyadiah, 2020). Finally, post-visit, VAs contribute to tourists’ satisfaction and loyalty thanks to the personalized support they provide throughout the customer journey. VAs can also promote social inclusion by helping visually impaired users share reviews or organize photos using voice commands (Buhalis & Amaranggana, 2015; Lam et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2024).

Despite these advances, VAs remain underused in ecotourism, particularly among families with children. Moreover, although tourism service providers such as hotels, airlines, and destination management organizations (DMOs) increasingly use VAs to personalize services, enhance guest experiences, and streamline operations (Buhalis & Moldavska, 2022), research has not systematically examined how families engage with VAs throughout the ecotourism journey. This gap is relevant because ecotourism increasingly attracts families seeking sustainable, inclusive, and educational experiences.

VAs have already proven effective in diverse tourism settings. In smart hotels, they can manage lighting and temperature and can deliver concierge-type services such as wake-up calls and local recommendations (Loureiro et al., 2021). In rural or low-connectivity destinations, offline VAs help senior tourists access important travel information (Moguel et al., 2023). Research has also shown that VAs improve customer comfort and retention, even in cases of service failure (Huang & Sénécal, 2023). Additionally, expressive and emotionally aware VAs help restore customer satisfaction after service failures and encourage repeat usage (Huang & Sénécal, 2023). Finally, cultural preferences shape how tourists may interact with VAs. American users value efficiency and directness, whereas Japanese users prefer politeness and respectful tones (Seaborn et al., 2024).

In the ecotourism context, VAs have the potential to meet the complex needs of families with children. VAs simplify decision-making and offer personalized recommendations (Basu, 2024). Likewise, they can facilitate the discovery of sustainable activities, enhancing family comfort and satisfaction (Soonthodu & Wahab, 2022). They also support children’s learning by providing interactive and educational content, in alignment with the experiential goals of family-oriented ecotourism (Malik & Kumar, 2024). In this regard, educational engagement is particularly valuable, with Lestar and Hancock (2024) finding that children understand sustainability better when exposed to targeted activities during eco-vacations. Similarly, Rahman et al. (2024) reported that AI-integrated accommodation and destination services enhance personalization and immersion, which are critical factors for increasing visitor satisfaction and loyalty. In sum, VAs can be valuable for DMOs seeking to tailor services to family travelers.

Acikgoz et al. (2023) called for research on specific tourism and hospitality challenges and opportunities around effectively engaging consumers through VAs. In terms of challenges, Tussyadiah (2020) noted the persistent behavioral problems of tourism stakeholders, calling for further research to explore how AI techniques can help address or change these problems. Furthermore, tourism efficiency research increasingly focuses on sustainability and digitalization trends, highlighting the need for further research into how innovative technologies can optimize resource management and visitor experiences (Blanco González-Tejero et al., 2025).

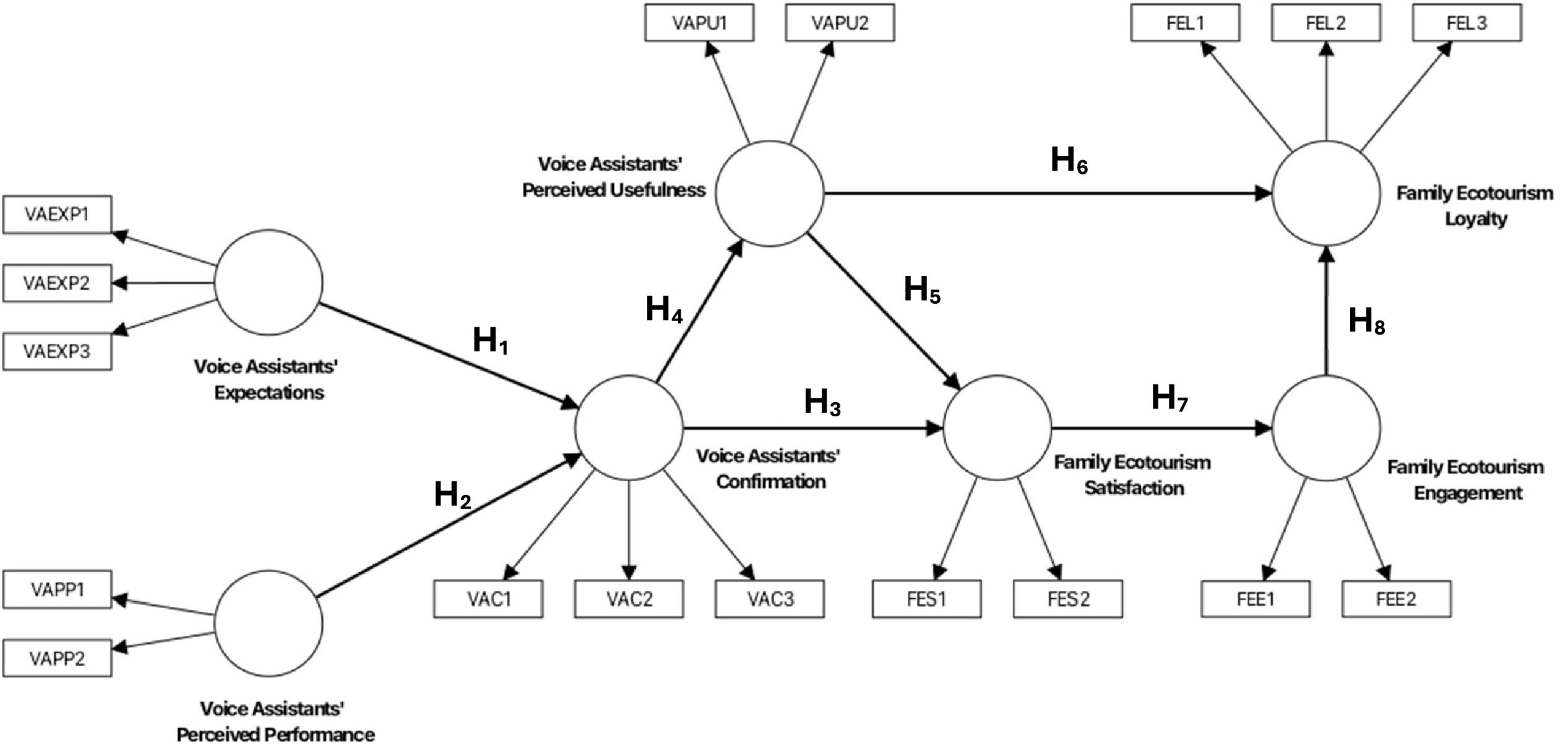

To address this gap, this study explores how VAs influence family ecotourism behavior, from decision-making to ecotourism loyalty. To do so, a conceptual model is proposed, combining expectation confirmation theory with the post-acceptance model of information systems (IS) continuance. The concept of tourist engagement is also adapted to the family ecotourism context and then tested as a mediator of the relationship between satisfaction and ecotourism loyalty (Rasul et al., 2024). This integrated research model provides theoretical and practical contributions by enabling exploration of the relationships between VA expectations, perceived performance, confirmation, and perceived usefulness and family ecotourism satisfaction, engagement, and loyalty pre-, in-, and post-visit. In sum, the study aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1 How do parents’ expectations and perceived performance of voice assistants influence family ecotourism satisfaction under mediation by confirmation?

RQ2 What are the effects of confirmation of voice assistants on family ecotourism satisfaction and loyalty under mediation by perceived usefulness?

RQ3 What is the effect of family ecotourism satisfaction on family ecotourism loyalty under mediation by family ecotourism engagement?

The findings reduce the theoretical gaps in understanding how stakeholders can tailor VAs to meet the needs of families who travel with children to ecotourism destinations. Moreover, they have practical implications for DMOs, local communities, and AI developers.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis formulationConfirmation of voice assistants in family ecotourismExpectation confirmation theory (ECT) is fundamental to understanding consumer satisfaction and post-adoption behavior (Oliver, 1980). It posits that consumers form initial expectations about a product or service and later compare these expectations with perceived performance during actual use. If perceived performance meets or exceeds expectations, then confirmation occurs, leading to high satisfaction and encouraging continued usage (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Reza et al, 2024). In contrast, if performance falls short of expectations, negative disconfirmation occurs, leading to low satisfaction and discouraging future use (Ambalov, 2021). This theory has been widely applied in IS and marketing to explain technology continuance behavior (Bhattacherjee, 2001; Mishra et al., 2023), particularly in dynamic, AI-mediated services such as tourism. Unlike adoption-focused models such as the technology acceptance model (TAM) or the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), expectation confirmation theory emphasizes the post-adoption evaluation phase. This phase depends on both pre-use expectations and post-use outcomes. Moreover, satisfaction is explicitly posited as a mediator between confirmation and future use (Ayyoub et al., 2023; Hossain & Quaddus, 2012; Liu & Huang, 2024).

Despite the relevance of VAs, there is limited empirical evidence on their use in ecotourism, particularly by families with children. Most studies of AI applications in tourism focus on general traveler demographics or hotel guests (Ivanov et al., 2020; Samala et al., 2022), leaving family ecotourism largely unexamined. Previous research on AI applications in tourism (Moguel et al., 2023; Seaborn et al., 2024) and VAs in marketing and consumer behavior (Acikgoz et al., 2023; Orden-Mejía & Huertas, 2022) have focused on smart hotels and general customer service but have rarely addressed ecotourism or family dynamics. This gap is noteworthy given that ecotourism emphasizes education, sustainability, and nature-based learning experiences (Adam et al., 2017; Lee, 2015), aspects that are highly valued by families (Buzlu et al., 2024). Although VAs are becoming more common in tourism (Huang & Sénécal, 2023; Xu et al., 2024), evidence about how families with children engage with VAs in nature-based destinations is missing. This absence of evidence limits the understanding of how expectation confirmation processes unfold in ecotourism.

Families frequently use AI assistants during travel planning and booking (Ling et al., 2023). Parents with experience using AI tools often have strong expectations that VAs will simplify planning and logistics and will offer educational and sustainable activities for children (Wang et al., 2024). Thongmak (2024) noted that well-managed expectations strengthen confirmation in AI contexts. However, uncertainty remains. Although overly high expectations can lead to disconfirmation if performance fails to deliver (Ambalov, 2021), realistic expectations can lead to high satisfaction (Bhattacherjee & Lin, 2015). In line with previous findings, the first hypothesis is proposed:

H1 Parents’ expectations of voice assistants have a significant positive effect on confirmation of voice assistants.

Although expectations are important, perceived performance during actual use is critical for confirmation. Tourism technology research has shown that tailored recommendations and reliable information increase user satisfaction by validating initial expectations (Liu & Niu, 2024; Topsakal & Çuhadar, 2024). In family ecotourism, a VA that accurately identifies edutainment activities, sustainable accommodation, and family-oriented eco-destinations is likely to meet or exceed expectations, leading to confirmation. Conversely, technical issues such as poor contextual understanding or limited connectivity in rural areas may create disconfirmation, as reported in the smart tourism literature (Yap et al., 2025). Therefore, the second hypothesis is proposed:

H2 The perceived performance of voice assistants has a significant positive effect on the confirmation of voice assistants.

Confirmation reflects the extent to which the perceived performance of VAs during use matches prior expectations (Hsu & Lin, 2015). Empirical research has shown that when confirmation is high, users feel more confident about the technology (Bhattacherjee, 2001) and report stronger satisfaction (Ayyoub et al., 2023; Mishra et al., 2023). Positive confirmation has been linked to sustained IS usage (Bhattacherjee & Lin, 2015), whereas negative disconfirmation decreases satisfaction and hinders continued use (Ambalov, 2021).

In the context of ecotourism, if families experience the anticipated benefits of a VA, such as meaningful child engagement and eco-friendly decision support, confirmation is likely to enhance family satisfaction. This prediction is aligned with the finding that expectation fulfillment fosters positive tourist experiences in AI-mediated services (Phaosathianphan & Leelasantitham, 2021). Thus, the third hypothesis is proposed:

H3 Confirmation of voice assistants has a significant positive effect on family ecotourism satisfaction.

The post-acceptance model of IS continuance proposed by Bhattacherjee (2001) extends expectation confirmation theory by focusing on post-adoption variables and introducing perceived usefulness as a determinant of continued usage. Bhattacherjee (2001) argued that the long-term success of technology relies on sustained use rather than one-time adoption. The post-acceptance model of IS continuance is applicable in this study because post-visit satisfaction is particularly relevant to family ecotourism for several reasons: (1) it captures families’ actual experiences rather than pre-visit expectations; (2) satisfied families can share positive word of mouth about sustainable ecotourism practices; and (3) continued VA use may lead to repeat or alternative ecotourism bookings, helping reduce overtourism in popular destinations.

Perceived usefulness is defined as consumers’ expectations of the benefits of using technology-based products or services (Davis, 1989). Previous research shows that users develop higher satisfaction when they perceive a system as useful (Mishra et al., 2023). This finding has been replicated in hospitality and tourism (Ivanov et al., 2020; Sousa et al., 2024). In tourism contexts, VAs enhance usefulness by reducing decision-making effort, providing hands-free access to information, and supporting tailored recommendations for families with children (Samala et al., 2022; Sousa et al., 2024). For example, a VA can help parents quickly adjust itineraries or find family-friendly eco-activities, increasing their perceptions of the VA’s practical value.

According to social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), children imitate their parents’ behaviors, particularly in early developmental stages (Jia & Yu, 2021; Krettenauer & Victor, 2017). Families that have already been exposed to VAs at home may use these practices in vacation planning, with children observing and replicating parents’ interactions with VAs (Andries & Robertson, 2023). Hence, if parents recognize a VA’s value, children may also perceive it as useful, making VA-assisted travel normative behavior in family ecotourism.

Although research has consistently found that confirmation enhances perceived usefulness in technology adoption (Mishra et al., 2023), little empirical evidence exists for ecotourism settings. However, in such settings, environmental constraints such as poor connectivity or a desire to disconnect from technology may moderate this relationship. Research on ride-hailing apps has likewise shown that user confirmation of system reliability strengthens perceived usefulness and encourages reuse (Weng et al., 2017). However, no study has tested this relationship for VAs in family ecotourism.

Building on the post-acceptance model of IS continuance and previous IS findings, it is hypothesized that when parents’ expectations of VA performance are confirmed during ecotourism trips, these parents are more likely to perceive the VA as beneficial for improving family travel experiences. Considering these arguments, the fourth hypothesis is proposed:

H4 Confirmation of voice assistants has a significant positive effect on the perceived usefulness of voice assistants.

Satisfaction is a psychological state of well-being and enjoyment triggered by a positive consumption experience (Lu & Stepchenkova, 2012). Satisfaction in ecotourism is shaped by different factors from satisfaction in mass tourism. Such factors include opportunities for social interaction, outdoor activities, eco-friendly accommodation, availability of information services, and educational value (Adam et al., 2017; Lee, 2015; Meng et al., 2008; Tsiotsou & Vasioti, 2006). Families traveling with children particularly value experiences that foster learning and relaxation while balancing the diverse preferences of family members.

AI-based tools, including VAs, have shown potential to enhance satisfaction drivers. VAs can facilitate meaningful social interactions by recommending cultural or group activities adapted to families (Barakazi, 2023), provide tailored eco-tours that reduce parental stress (Nyongesa & Van Der Westhuizen, 2024), and improve access to safety and sustainability information (Phaosathianphan & Leelasantitham, 2019). Such benefits suggest that VAs could enhance satisfaction in ecotourism settings by supporting educational and environmentally responsible travel experiences.

Despite these potential advantages, empirical evidence on family ecotourism satisfaction remains scarce. Research has largely examined mass-tourism populations or hospitability services, offering limited insights into how parents and children experience VAs during eco-travel. Furthermore, although studies recognize that perceived usefulness increases satisfaction with digital tools (Mishra et al., 2023), it is unclear whether this relationship holds in ecotourism, where low connectivity and the desire to disconnect from technology might moderate perceived usefulness. Addressing this issue is essential to determine whether VAs can improve eco-destination satisfaction for families rather than merely replicating the benefits observed in mass-tourism environments.

A VA that streamlines planning, assists with sustainable decision-making, and engages children in nature-focused learning is likely to enhance a family’s enjoyment and overall satisfaction. Conversely, a perceived lack of utility from, for example, irrelevant recommendations or poor adaptation to eco-settings may lead to frustration and diminished satisfaction. Hence, the fifth hypothesis is proposed:

H5 The perceived usefulness of voice assistants has a significant positive effect on family ecotourism satisfaction.

Customer loyalty is defined as a deep psychological commitment to consistently purchase a favorite product/service, thereby causing repetitive purchases of the same brand, despite circumstances and marketing efforts that have the potential to cause a change in consumer behavior (Oliver, 1999). In tourism, specifically ecotourism, loyalty is expressed through repeat visits and positive word-of-mouth recommendations to relatives, friends, and acquaintances (Carvache-Franco et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021). However, repeating visits in ecotourism does not necessarily imply returning to the same destination. Instead, loyal ecotourists often organize similar nature-based trips at different destinations and recommend these experiences (Chen & Gursoy, 2001).

Perceived usefulness, or “the extent to which a person believes that using a technology will enhance their performance” (Davis, 1989), is a key predictor of user intention to continue using IS (Dai et al., 2020). Bhattacherjee (2001) showed that perceived usefulness, together with satisfaction, strongly predicts IS continuance behavior. Similarly, Kang et al. (2009) found that consumers keep using social platforms when they perceive tangible benefits. These findings suggest that when a technology proves valuable in practice, users are more inclined to reuse it and develop loyalty toward it.

Applying this idea to family ecotourism, if parents perceive VAs as useful for improving their vacations by simplifying eco-friendly planning, supporting sustainable choices, and enriching children’s educational experiences, then they are more likely to use VAs again in future ecotourism trips. Furthermore, families that experience these benefits are likely to share positive recommendations with their social networks, encouraging others to adopt similar technologies when choosing new ecotourism destinations. Hence, the sixth hypothesis is proposed:

H6 The perceived usefulness of voice assistants has a significant positive effect on family ecotourism loyalty.

Customer engagement refers to the investment of a customer’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral resources in brand interactions (Hollebeek et al., 2022; Huang & Choi, 2019). As a multifaceted psychological construct, engagement encompasses cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions (Abbasi et al., 2024; Harrigan et al., 2017). It has also been described in terms of subdimensions such as identification, attention, absorption, enthusiasm, and interaction (So et al., 2016). In tourism, engagement has been defined as a visitor’s proactive interaction with an event or destination (Lim et al., 2022; Loureiro & Sarmento, 2018; Rasul et al., 2024).

Customer satisfaction is a well-established driver of engagement. Marketing studies have shown that higher satisfaction levels boost customer engagement (Brodie et al., 2013). Similarly, tourism research has revealed a robust correlation between satisfaction and engagement (Cantallops & Salvi, 2014). In practice, tourists who experience joy and excitement during trips are more likely to exhibit enthusiastic engagement behaviors (Chathoth et al., 2016).

In family ecotourism, parents’ satisfaction is critical for fostering engagement. Buzlu et al. (2024) found that child-friendly, play-based activities enhance parents’ satisfaction and family relationships. This enhanced level of satisfaction and family relationships in turn promotes higher family ecotourism engagement. Likewise, balanced vacations that cater to both parents and children strengthen family bonds and lead to greater engagement (Fu et al., 2022; Koščak et al., 2024). High-quality parent–child interactions on trips significantly increase positive emotions (Atsiz, 2022). Meanwhile sustainable activities involving children positively influence the family’s ecotourism engagement (Mandić et al., 2023).

Although research linking VAs to family ecotourism is scarce, studies of technology-enhanced travel highlight their potential benefits. Smart technologies can provide immediate, context-aware information, reducing logistical hassles for tourists and fostering more meaningful engagement (Neuhofer et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). In a family context, VAs are handy travel aides that simplify ecotourism planning, offer child-friendly recommendations, and resolve routine queries. These functions reduce parental stress and improve the overall family travel experience. Moreover, AI-driven assistants can engage children with educational and entertaining content (Han et al., 2022), enriching the family’s interaction with ecotourism. By reducing parental burdens and keeping children constructively occupied, VAs are expected to enhance overall family satisfaction. This enhanced satisfaction should in turn foster greater family engagement. Considering these arguments, the seventh hypothesis is proposed:

H7 Family ecotourism satisfaction has a significant positive effect on family ecotourism engagement driven by voice assistants.

Predicting tourism loyalty requires understanding visitors’ on-site emotional engagement. This form of engagement refers to how connected tourists feel during their experience (Taheri et al., 2014). However, previous research has provided mixed findings. For instance, although some studies have found that engagement can positively influence loyalty (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2021), other research has revealed weak or no effects (Khan et al., 2020; Kumar & Kaushik, 2020; Seyfi et al., 2021). This inconsistency is partly explained by novelty-seeking behavior, where even satisfied tourists avoid repeat visits in favor of new destinations (Assaker et al., 2011; Dolnicar et al., 2013). This trend also applies to ecotourism, with eco-travelers often pursuing once-in-a-lifetime natural experiences (Rivera & Croes, 2010) that challenge the traditional concept of destination loyalty.

Therefore, loyalty measures must be reconceptualized for ecotourism (Chen & Gursoy, 2001). Rather than revisiting the same destination, loyal ecotourists frequently choose other eco-destinations and recommend ecotourism experiences to peers. This reconceptualization is crucial for understanding loyalty in family ecotourism, where decision-making involves balancing the educational and recreational needs of both parents and children.

Despite the well-acknowledged role of on-site engagement in fostering loyalty, little empirical research has examined how technology, particularly VAs, influence engagement during ecotourism vacations. For instance, VAs can enhance family ecotourism engagement by offering context-specific guidance such as eco-trail navigation, safety alerts, interactive educational content for children, and personalized suggestions for sustainable activities (Han et al., 2022). Such on-site support reduces the logistical burden for parents and enriches the family’s connection with nature, potentially creating memorable experiences.

In this study, it is argued that families that are highly engaged during an eco-trip thanks to on-site interactions with VAs will be more inclined to continue choosing ecotourism for future vacations and to recommend this form of travel. In this case, loyalty reflects a commitment to ecotourism rather than repeat visits to the same destination. Hence, the eighth hypothesis is proposed:

H8 Family ecotourism engagement has a significant positive effect on family ecotourism loyalty driven by voice assistants.

In this study, expectation confirmation theory (Oliver, 1980) is integrated with the post-acceptance model of IS continuance (Bhattacherjee, 2001) to test a robust research model explaining the VA-driven family ecotourism journey, from decision-making to ecotourism loyalty (Fig. 1). The study adapts the following constructs from expectation confirmation theory and the post-acceptance model of IS continuance: VA expectations, VA perceived performance, VA confirmation, VA perceived usefulness, family ecotourism satisfaction, and family ecotourism loyalty. Using these constructs, the study assesses parents’ perceived alignment between initial expectations and actual use of VAs in creating outstanding ecotourism experiences, considering all three stages of an ecotourism vacation (pre-, in-, and post-visit). This conceptual research model was enhanced by adding family ecotourism engagement as a mediator of the relationship between family ecotourism satisfaction and family ecotourism loyalty.

The study thereby addresses calls for research in this area (Hollebeek et al., 2024; Rasul et al., 2024).

The study uses a mixed-methods approach combining partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). The analysis benefits from the strengths of both methodologies. PLS-SEM identifies linear cause–effect relationships between the proposed constructs. FsQCA uncovers non-linear interactions among latent concepts (Hair et al., 2021; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). This mixed-methods approach is aligned with complexity theory and accounts for the idea that VA-driven family ecotourism behavior may result from multiple, interacting antecedents that do not follow a single, symmetric causal path. Recent research in tourism has confirmed that combining symmetric and asymmetric methods enhances explanatory depth and robustness of findings by capturing equifinality and causal asymmetry in behavioral models (Seyfi et al., 2021). In this study, the PLS-SEM and fsQCA findings are complementary and largely convergent. They jointly provide a nuanced understanding of the drivers of VA-driven family ecotourism loyalty.

PLS-SEM methodologyPLS-SEM was chosen as one of the analytical methods given its broad application in business and social science research and its suitability for prediction-oriented studies (Dragan et al., 2024; Law & Fong, 2020). PLS-SEM was particularly suitable for the current study because several constructs were measured with a limited number of items (Hair et al., 2021), as reflected in Table 1. All latent variables were modeled reflectively because the items were designed to capture the same concept and were expected to vary in similar ways. To ensure robustness, the measurement model was first assessed for reliability and validity. The structural model was then tested to evaluate the hypothesized causal relationships.

Measurement model constructs and items.

To complement the variance-based results, fsQCA was also applied. This method enables the identification of different combinations of antecedent conditions that can lead to the same outcome, rather than focusing only on individual net effects. FsQCA was particularly helpful in uncovering multiple pathways through which expectations, performance, confirmation, and usefulness of VAs, as well as satisfaction and engagement, could result in family ecotourism loyalty. The analysis followed established set-theoretic procedures (Drăgan et al., 2025; Ragin, 2000). First, the 7-point Likert-scale responses were calibrated into fuzzy sets using three anchors: full membership (a score of 7), crossover (a score of 4), and full non-membership (a score of 1). Calibration translated each case into a value between 0 and 1, thereby capturing the extent of partial membership in the relevant sets (Table 2). After calibration, truth tables were constructed and minimized to identify consistent and empirically relevant configurations. Consistency and coverage scores were then examined to evaluate the sufficiency of these solutions. This configurational approach enriched the analysis by acknowledging that more than one causal recipe can explain high VA-driven family ecotourism loyalty.

Calibration thresholds and corresponding fuzzy values.

Notes. Source: Authors, adapted from Ragin (2000).

To test the study hypotheses, three short questionnaires were designed in Google Forms. Constructs were measured with two or three items to ensure parsimony and reduce respondent fatigue. Recent studies have shown that concise scales can maintain theoretical precision and acceptable reliability if items are well-defined and conceptually aligned with the target construct (Green & Elphinstone, 2025; Hernández-Fernaud et al., 2025).

Collaboration with DMOs and accommodation establishments in Romanian ecotourism destinations enabled collection at all stages of the respondent’s vacation: pre-, in-, and post-visit. Purposive sampling was used because it enabled the selection of respondents who closely matched the study’s target population. It ensured that every respondent was directly relevant to the research objectives, resulting in a contextually meaningful data set. Purposive case sampling, which identifies the population of cases based on the outcome of interest, is considered good practice in large-N qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) research (Greckhamer et al., 2018).

Sampling was limited to families visiting Romanian ecotourism destinations. They were recruited at the accommodation establishments. This strategy was aligned with established practices in tourism research and was appropriate for generating context-specific insights, even though it may limit generalizability. The longitudinal research design of collecting data at three points (pre-, in-, and post-visit) strengthened internal validity by tracking behavioral changes over time. To reduce respondent fatigue and social desirability bias, the questionnaires were concise and anonymously self-administered. This feature enhanced data reliability (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Initially, pilot surveys were conducted. In these surveys, 25 parents completed the pre-trip questionnaire online, the in-visit questionnaire at the accommodation establishment, and the post-trip questionnaire upon their return. The pilot surveys were completed between March and May 2024. Based on the preliminary results, the wording and order of the questions was improved. The post-trip pilot survey also highlighted the need for reminders to increase participation post-vacation.

The pre-visit questionnaire included three filter questions. It targeted families who had experience using VAs, used VAs to plan family vacations, and used VAs for on-site tourist experiences. Five items related to the constructs of VA expectations and VA perceived performance were considered. The link to the questionnaire was shared by email with families who booked their vacations at a participating accommodation establishment seven to 14 days before their arrival. The in-visit questionnaire had seven items related to confirmation of VAs, perceived usefulness of VAs, and family ecotourism engagement. Accommodation staff encouraged parents who had completed the pre-visit survey to complete this second survey during checkout using a QR code displayed at reception. The post-visit questionnaire had five items related to family ecotourism satisfaction, and family ecotourism loyalty. It also included additional items to provide the complete demographic profile of the participating families (Table 3). The link to this last questionnaire was sent by the accommodation staff via email in the week following checkout. Only families who completed the first two questionnaires were contacted to participate in this final stage. In total, 235 respondents completed all three surveys between June and October 2024.

Demographic profile of respondents.

Notes. Source: Authors.

The study considered only parents who traveled with children aged 7 to 12 years because children develop the ability to use smart phones and interact with advanced digital applications by age 7 years (Yadav et al., 2020).

The upper age limit of 12 years was chosen based on factors of children’s behavior and development to ensure that children were strongly tied to the family environment and were heavily reliant on parental guidance, which was crucial for the purposes of this research (Krettenauer & Victor, 2017). Of these 235 responses, 16 were removed because they did not meet the criteria for children’s ages. Responses were checked to ensure a standard deviation of less than 0.25. Values higher than this cutoff could indicate potential respondent misconduct (Collier, 2020). Accordingly, another 14 responses were deleted. The final sample therefore consisted of 205 valid responses. A prospective approach was used to estimate the minimum required sample size in quantitative research (Nakagawa & Foster, 2004). The target effect size was 0.04, twice Cohen’s minimum threshold (Cohen, 1992). For complex research models, where competing links reduce the effect size, Kock and Hadaya (2018) suggest a minimum sample size of 160, based on the inverse square root method. Data were prepared in SmartPLS Version 4. The 17 items across all three questionnaires were measured using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

ResultsPLS-SEM analysisThe measurement model’s internal consistency, discriminant validity, convergent validity, and construct loadings were first assessed (Hair et al., 2021). Items with outer loadings of less than 0.7 were removed from the model (Ali et al., 2018). Discriminant validity increased considerably following deletion of these items. To evaluate internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha and the composite confidence level (rho_and rho_c) were calculated using SmartPLS4 software. Convergent validity was also checked by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE). Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.642 (perceived usefulness of VAs) to 0.857 (family ecotourism satisfaction) were satisfactory. Composite reliability values (rho_and rho_c) were higher than the 0.7 threshold for most constructs. AVE values for all seven variables were higher than the minimum accepted threshold of 0.5 (Table 4).

Assessment of internal consistency and convergent validity of the research model.

Notes. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness.

Because the data were collected via online questionnaires, collinearity and common-method bias checks were performed. All inner-model variance inflation factors (VIFs) were below 3.3 (Kock, 2015), as reflected in Table 5.

Assessment of collinearity statistics for the inner model.

| Relationship | Variance inflation factor (VIF) |

|---|---|

| FEE → FEL | 1.608 |

| FES → FEE | 1.000 |

| VAC → FES | 1.486 |

| VAC → VAPU | 1.000 |

| VAEXP → VAC | 1.303 |

| VAPP → VAC | 1.303 |

| VAPU → FEL | 1.608 |

| VAPU → FES | 1.486 |

Notes. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness.

Discriminant validity was examined using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) (Henseler et al., 2015). In line with accepted guidelines, all values were below 0.90, providing support for the discriminant validity of the model (Table 6).

Discriminant validity using the HTMT ratio.

| Variable | FEE | FEL | FES | VAC | VAEXP | VAPP | VAPU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEE | |||||||

| FEL | 0.884 | ||||||

| FES | 0.738 | 0.779 | |||||

| VAC | 0.846 | 0.768 | 0.671 | ||||

| VAEXP | 0.653 | 0.708 | 0.689 | 0.886 | |||

| VAPP | 0.701 | 0.685 | 0.711 | 0.842 | 0.637 | ||

| VAPU | 0.888 | 0.885 | 0.819 | 0.856 | 0.895 | 0.803 |

Notes. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness.

According to the structural model, in Romanian ecotourism destinations, VA-driven family ecotourism satisfaction had the largest impact (0.594) on family ecotourism engagement. VA confirmation had the smallest impact on family ecotourism satisfaction, with an effect coefficient of 0.244 (Fig. 2).

The statistical contributions of reflective latent variables to constructs were indicated by their external loadings. The voice assistant’s accurate information will help my children discover edutainment activities that match their ecotourism vacation preferences (VAEXP1) had the largest statistical contribution to the construct of VA expectations (Fig. 2). The voice assistant suggests accurate information for selecting the most suitable ecotourism destination (VAPP2) had the greatest statistical impact on VA perceived performance. Most respondents agreed that the ecotourism destination chosen based on the voice assistant’s helpful insights confirmed both parents’ and children’s expectations (VAC3). This item had the largest statistical contribution to the latent construct of VA confirmation. Furthermore, parents reported that using the voice assistant improved the family’s overall vacation experience by providing tailored recommendations (VAPU2).

This item had the highest statistical contribution to the latent variable of VA perceived usefulness. In addition, most parents reported that they were pleased with the voice assistant’s guidance for exploring ecotourism activities (FES1). This item had the highest statistical contribution to the construct of family ecotourism satisfaction. Parents stated that during the ecotourism vacation, they frequently interacted with the sustainability education resources available at the accommodation recommended by the voice assistant (FEE1). This item had the greatest statistical contribution to the latent variable of family ecotourism engagement. Finally, most parents reported that, based on the experience with the voice assistant, their family planned to visit new ecotourism destinations in the future (FEL3). This item had the highest statistical contribution to the family ecotourism loyalty outcome variable.

Regarding explained variance: 52.9 % of the variance of the VA confirmation construct was explained by the combined effects of VA expectations and VA perceived performance (coefficient of determination R2 = 0.529); 32.7 % of the variance of the VA perceived usefulness variable was explained by the effect of VA confirmation (R2 = 0.327); 41.5 % of the variance of the family ecotourism satisfaction construct was explained by the combined effects of VA confirmation and VA perceived usefulness (R2 = 0.415); 35.3 % of the variance of the family ecotourism engagement construct was explained by the effect of family ecotourism satisfaction (R2 = 0.353); and 57.8 % of the variance of the family ecotourism loyalty construct was explained by the combined effects of VA perceived usefulness and family ecotourism engagement (R2 = 0.578).

PLS-SEM uses bootstrapping to test the hypotheses. This process means that, to estimate the structural model, subsamples are created using random observations from the original data set. In this study, fewer than 5000 samples were produced by the SmartPLS software. Statistical reports with t-test findings and asymptotic significance (p values) were generated using parameter estimations from the structural model. One-tailed tests usually result in smaller p values. Therefore, a two-tailed test was performed to validate or reject the hypotheses (Kock, 2015). All hypotheses were found to be valid given their p values of less 0.05 (Table 7). Furthermore, the t-test revealed the strength of the relationships between the constructs of the research model. Family ecotourism satisfaction had the greatest impact on the family ecotourism engagement (tvalue = 12.217).

Values for the asymptotic significance p and t-test for the structural model hypotheses.

Notes. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness.

The specific indirect effects indicated that VA confirmation significantly mediated the relationships between VA expectations and family ecotourism satisfaction and between VA perceived performance and family ecotourism satisfaction. These results suggest that families’ confirmation of their initial expectations regarding VAs and the perceived performance of VAs are factors that drive their ecotourism satisfaction. Furthermore, VA perceived usefulness had significant mediating effects on the relationships between VA confirmation and family ecotourism satisfaction and between VA confirmation and family ecotourism loyalty. A significant mediating effect was also observed for family ecotourism engagement on the relationship between family ecotourism satisfaction and family ecotourism loyalty (Table 8).

Values for asymptotic significance p and t-test for specific indirect effects.

Notes. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness.

The research identifies one probable model based on the possible outcome. The fsQCA indicates that several different combinations of conditions can lead to the outcome of family ecotourism loyalty. Following Woodside (2014), configurations with consistency scores above 0.75 were treated as sufficient. The XY plot confirmed that all six conditions surpassed this value for family ecotourism loyalty.

For the model Antecedents (VA expectations, VA perceived performance, VA confirmation, VA perceived usefulness, family ecotourism satisfaction, family ecotourism engagement) → Outcome (family ecotourism loyalty), the consistency was 0.97767, with a coverage of 0.649502. These values imply that the distribution of fuzzy sets is highly consistent with the assumption that Antecedents are a subset of the outcome and that the newly created fuzzy model covers 64.95 % of the outcome.

Further investigation was required, even though the consistency and coverage scores indicated strong causality among cases in this configuration. To identify sufficient configurations, truth tables were produced and the intermediate, parsimonious, and complex solutions were examined. A frequency cut-off of 3 was applied (Pappas & Woodside, 2021) to ensure stable configurations in the sample of 205 respondents. To reduce Type I and Type II errors, proportional reduction of inconsistency (PRI) and symmetric (SYM) consistency were checked against the 0.7 threshold (Dul, 2016). The configuration falling below this value is shown in bold in Table 9.

Truth table analysis for the outcome.

Notes. Source: Authors. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness; PRI = proportional reduction of inconsistency; SYM = symmetric.

For the model Antecedents (VA expectations, VA perceived performance, VA confirmation, VA perceived usefulness, family ecotourism satisfaction, family ecotourism engagement) → Outcome (family ecotourism loyalty), the truth table depicts all logically possible causal pairings between the different combinations of antecedent conditions and the outcome of interest (Table 9). The truth table for the negated outcome (Table 10) shows two possible configurations of antecedent conditions that may be barriers to the use of VAs and that may have little or no impact on the ecotourism loyalty of families traveling with children.

Truth table analysis for the negated outcome.

Notes. Source: Authors. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness; PRI = proportional reduction of inconsistency; SYM = symmetric.

The Quine-McCluskey algorithm was used to find the intermediate, parsimonious, and complex solutions for the positive outcome. The analysis of the positive outcome, family ecotourism loyalty = f (VA expectations, VA perceived performance, VA confirmation, VA perceived usefulness, family ecotourism satisfaction, family ecotourism engagement), revealed 12, three, and 12 causal configurations in the complex, parsimonious, and intermediate solutions leading to the outcome (Table 11).

Of the six causal conditions, VA expectations is the most important condition, appearing as a core condition in Solutions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, and 12. Its consistent presence underscores its critical role in producing the outcome. In some cases, such as Solution 7, it appears to be irrelevant for the outcome, given the presence of alternative pathways.

Family ecotourism satisfaction is the second most important condition, appearing as a core condition in half of the solutions. It has a slightly less consistent influence on family ecotourism loyalty than VA expectations. However, its absence in Solutions 5, 6, and 7 shows that high family ecotourism loyalty can still be achieved through alternative combinations of conditions such as VA expectations or family ecotourism engagement.

The results also show that family ecotourism engagement is not always essential for family ecotourism loyalty, given that other variables such as VA expectations or family ecotourism satisfaction are stronger drivers in half of the solutions. However, its status as a core condition in three solutions highlights its importance, with family ecotourism engagement enhancing family ecotourism loyalty when combined with VA perceived usefulness, VA perceived performance, and VA expectations.

VA perceived performance, VA confirmation, and VA perceived usefulness are secondary drivers for achieving family ecotourism loyalty. Their peripheral presence shows that they enhance family ecotourism loyalty only when combined with key drivers such as VA expectations or family ecotourism satisfaction. Thus, their absence in most of the solutions indicates that they are less critical. Accordingly, families view these VA features as important but not decisive, supporting ecotourism loyalty only in specific configurations.

The fsQCA results show that family ecotourism loyalty is not driven by a single dominant factor but emerges from different combinations of conditions, highlighting the configurational and non-linear nature of this behavior (Ragin, 2000). VA expectations are a core driver. The presence of this condition in most solutions suggests that families’ pre-visit expectations about the ability of VAs to deliver tailored sustainable recommendations strongly influence their loyalty. Interestingly, loyalty can still be achieved when family ecotourism engagement is moderate or when family ecotourism satisfaction is not consistently high if VA expectations are strong, supported by the presence of other conditions such as VA perceived usefulness and VA confirmation. This finding confirms that different pathways rather than a single causal route can successfully foster loyalty. The finding is thus aligned with the principle of equifinality in configurational theory (Woodside, 2014).

The analysis of the negative outcome, ∼family ecotourism loyalty = f (VA expectations, VA perceived performance, VA confirmation, VA perceived usefulness, family ecotourism satisfaction, family ecotourism engagement), revealed seven configurations for each of the complex, parsimonious, and intermediate solutions leading to the outcome (Table 12).

Truth table analysis solutions for the model Antecedents → Negated Outcome (absence of family ecotourism loyalty).

Notes. Source: Authors. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness. Black circles (●) indicate the presence of a condition; crossed-out circles (ⓧ) indicate the absence of a condition; blank squares indicate an irrelevant condition; large circles indicate core conditions; small circles indicate peripheral conditions.

The absence of family ecotourism loyalty is predicted by the absence of core conditions such as VA expectations, VA perceived performance, VA confirmation, and VA perceived usefulness. In the absence of VA expectations, family ecotourism loyalty is low. The absence of family ecotourism satisfaction and family ecotourism engagement also contributes to low family ecotourism loyalty, indicating that unfulfilled experiential and technological needs drive low loyalty. To avoid this outcome, ecotourism destinations must align VA capabilities with family expectations to generate high satisfaction and engagement.

As explained by Ragin (2000), QCA relies on configurational reasoning, according to which outcomes arise from several causes acting together. The fsQCA in this study shows that family ecotourism loyalty can be achieved through different condition sets, thereby reflecting equifinality. The changing role of some factors depending on others illustrates conjunctural causation, according to which the impact of one condition depends on the presence or absence of another.

There are 12 possible combinations of necessary conditions that could lead to the positive or negative outcome (Table 13). None of these conditions for either the positive or the negative outcome exceed the 0.9 consistency threshold, meaning that no single condition is necessary on its own. Although conditions such as family ecotourism satisfaction and VA perceived usefulness have high values for consistency, they are not individually necessary to explain the outcome. This finding highlights the configurational nature of family ecotourism loyalty, which results from combinations of conditions rather than single drivers.

Necessary conditions for the models Antecedents → Outcome (family ecotourism loyalty) and Antecedents → Outcome (absence of family ecotourism loyalty).

Notes. Source: Authors. FEE = family ecotourism engagement; FEL = family ecotourism loyalty; FES = family ecotourism satisfaction; VAC = VA confirmation; VAEXP = VA expectations; VAPP = VA perceived performance; VAPU = VA perceived usefulness.

Combining the findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA can provide valuable conclusions. Although the PLS-SEM analysis confirms a dominant linear pathway where higher family ecotourism satisfaction increases family ecotourism engagement and ultimately family ecotourism loyalty, the fsQCA adds an asymmetric perspective, revealing alternative pathways to loyalty. For instance, some families develop strong ecotourism loyalty despite moderate engagement if their expectations about VA performance are fulfilled early in the journey. This insight was not evident from symmetric analysis and shows that fsQCA complements PLS-SEM analysis by identifying multiple sufficient configurations. This mixed-methods approach thus provides a richer understanding of how VAs shape family ecotourism loyalty. Together, these findings suggest that ecotourism DMOs should not only aim to maximize satisfaction but also focus on meeting realistic expectations about VAs to achieve family loyalty outcomes.

Discussion and conclusionsTheoretical contributions and implicationsThis study advances the general understanding of technology-mediated family ecotourism by integrating expectation confirmation theory with the post-acceptance model of IS continuance. It thus offers a new conceptual framework that captures pre-, in-, and post-visit family behavior in terms of VA usage. Unlike previous research using these theories separately or focusing on other forms of tourism (Flavián et al., 2023; Ling et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2022) and technology contexts (Ashfaq et al., 2020; Bhattacherjee, 2001), this study is novel in that it includes family ecotourism engagement as a mediator in the model, thus highlighting the role of emotional and cognitive drivers in shaping satisfaction and loyalty. This approach provides new conceptual insights into how AI-driven technologies influence sustainable family travel behavior across different vacation stages. This new model could be generalized to other tourism market segments such as adventure tourism, cultural tourism, and wellness by adapting the engagement construct and sustainability expectations to reflect specific tourist motivations and environmental contexts. The model thus offers a transferable theoretical basis for studying technology-mediated tourist experiences. The study also addresses recent calls for research on customer experience and engagement in technology-mediated business (Bakir & Sak, 2025).

The validation of H1 and H2 confirms that parents’ initial expectations of VAs and parents’ perceptions of VA performance significantly enhance the VA confirmation process. This finding aligns with previous findings showing that users develop trust in VAs when their expectations are met (Flavián et al., 2023) and when VAs deliver accurate and timely responses during travel planning (Zhang, 2024). This study extends existing findings beyond the general trip planning functionalities reported in previous studies to specific functionalities in family ecotourism. It reveals that confirmation depends particularly on VAs’ ability to address child-specific needs such as recommending edutainment activities or balance family needs when selecting sustainable accommodation. However, the findings also present a nuanced view in light of the findings of Sun et al. (2022) who showed that disconfirmed expectations about VAs such as low customization negatively affect user confirmation and trust. Furthermore, Cai et al. (2022) reported that performance inconsistencies might make confirmation difficult, citing a need for trustworthy AI tools. In this context, the current findings are valuable in that they highlight the importance of meeting the specific sustainability education, sustainable accommodation, and enjoyment demands of families traveling with children in order to ensure strong confirmation.

The significant positive relationships supporting H3 and H4 show that confirmation enhances both satisfaction and perceived usefulness of VAs. This finding is aligned with those of Yu et al. (2024) and Ling et al. (2023). Unlike previous general tourism research, the current study shows that features of VAs in relation to ecotourism such as recommendations for sustainable accommodation and educational outdoor activities are central to the perceived usefulness of VAs in the eyes of families.

For H5 and H6, the results indicate that perceived usefulness is a robust predictor of satisfaction and loyalty, supporting the findings of Ashfaq et al. (2020) and Bhattacherjee (2001). In this study, ecotourism loyalty is redefined from repeat visits to the same destination (Lee et al., 2021) to include new ecotourism destinations as well. This approach highlights the idea that families who perceive VAs as useful tend to continue using VAs to explore new ecotourism destinations, thereby contributing to sustainable tourism behavior rather than traditional destination loyalty (Dolnicar et al., 2013).

The positive mediating effect of family ecotourism engagement (H7 and H8) confirms previous findings that technology-driven satisfaction deepens emotional and cognitive engagement, thereby enhancing loyalty (Buhalis & Moldavska, 2022; Maduku et al., 2024). This study provides empirical evidence that on-site engagement, supported by VAs’ recommendations of immersive, child-friendly, sustainable activities, reinforces families’ psychological commitment to ecotourism products. The results also confirm the role of VAs in creating a positive feedback loop: family ecotourism satisfaction leads to deeper engagement and eventually family ecotourism loyalty thanks to the continuing use of VAs to visit and recommend new ecotourism destinations.

The fsQCA results complement the PLS-SEM findings by revealing that family ecotourism loyalty is shaped by multiple, asymmetric paths rather than a single linear pathway. Specifically, VA expectations and family ecotourism satisfaction are consistent core conditions, frequently appearing in the configurations leading to high family ecotourism loyalty. In contrast, VA perceived usefulness, VA confirmation, and VA perceived performance are largely peripheral conditions, contributing to family ecotourism loyalty only when combined with core conditions. For instance, high family ecotourism loyalty can occur even when family ecotourism engagement is low, if VA expectations and family ecotourism satisfaction are met. In terms of its theoretical approach, this study differs from that of the traditional symmetric analyses of destination loyalty, instead introducing a non-linear, family-centered loyalty mechanism. The study thus shows that AI-mediated engagement in ecotourism depends on meeting sustainability-related expectations during pre-visit planning and on achieving post-visit satisfaction.

Implications for practiceThis research offers fresh insights for ecotourism stakeholders such as DMOs, AI developers, and local communities. Specifically, it highlights how VAs can be strategically designed and used to increase family engagement, satisfaction, and loyalty toward ecotourism destinations (Table 14). As well as showing the importance of incorporating sustainability features, the findings show that context-specific VA design is crucial. For example, family-oriented VAs should include tailored eco-trail planners, interactive storytelling for children, and real-time sustainability tips, such as energy-saving actions or wildlife protection advice during activities. Such designs would help ensure that parents and children engage together with the destination in a playful yet educational way. Moreover, the fsQCA results underscore VA expectations and family ecotourism satisfaction as core drivers of loyalty, suggesting that destination services should ensure high-quality, accurate responses for family travel needs, including child-friendly accommodation recommendations, safety guidance, and adaptive language for children. DMOs could collaborate with AI developers and residents of ecotourism destinations to design family profiles within the VA platform that adjust recommendations based on children’s ages, activity preferences, and sustainability education goals.

Practical implications for ecotourism stakeholders.

Notes. Source: Authors.nn

Despite its rigorous and relevant contributions to theory and practice, this empirical study has certain limitations. First, although the sample size is sufficient to provide an initial understanding of the influence of VAs on family ecotourism behaviors ranging from decision-making to ecotourism loyalty, a larger sample is needed. Second, the study focused specifically on parents traveling with children to Romanian ecotourism destinations, so applying the findings to other forms of tourism, tourist demographics, and regions may be difficult. Third, the perceived ease of use of VAs was not considered. Families that prefer similar text-based AI assistants may consider VAs difficult to use, which may negatively affect families’ satisfaction, engagement, and loyalty. Fourth, only parents completed the questionnaires, even though certain items referred to ecotourism services that involve parent–child socialization and engagement. Although prominent psychology studies have concluded that parents are role models for children aged 12 years and under, to study their pro-environmental behavior specifically in reference to ecotourism destinations, a focus on individual parents’ and children’s perceptions is necessary. Fifth, variables were measured using two or three items. Although this approach improves survey efficiency, it may lead to the underrepresentation of complex constructs and may slightly limit psychometric robustness (Flake & Fried, 2020).

Hence, future research could employ extended scales to strengthen construct precision. Furthermore, future studies could explore the direct effects of family ecotourism satisfaction on loyalty, besides the mediation effect via engagement. Testing for invariance between parents’ and children’s perceptions of ecotourism edutainment activities and eco-lodging services using PLS-SEM multigroup analysis could be another valuable approach. Comparative research between various destinations would also be useful, considering the limited number of studies in Europe regarding parents’ and children’s perceptions of the benefits of VAs for AI business models in tourism and hospitality. Additionally, future research should consider longitudinal designs to track VA use and engagement across multiple trips, thereby addressing cross-sectional bias. Cross-cultural studies could test the model’s applicability in different ecotourism markets, and experimental approaches could establish stronger causal links between VA features and sustainable behaviors. Finally, extending expectation confirmation theory and the post-acceptance model of information systems (IS) continuance to other demographic groups could be of interest. For example considering digital nomads, a group among which sustainable lifestyles and mobility are strongly mediated by digital platforms (Lacárcel, 2025), could clarify whether technology-mediated engagement and loyalty mechanisms can be generalized across market segments.

CRediT authorship contribution statementIulian Adrian Sorcaru: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Mihaela-Carmen Muntean: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ludmila-Daniela Manea: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Rozalia Nistor: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision.