This study investigates the determinants shaping Construction 4.0 adoption in the Australian construction sector, with a focus on organisational integration and workforce skills development. Drawing on the technology-organisation-environment (TOE), resource-based view (RBV) and socio-technical systems (STS) frameworks, the study explores how organisational readiness, skills capability and contextual infrastructure influence digital transformation. After conducting semi-structured interviews with 23 industry experts, findings reveal that while technologies such as building information modelling (BIM) and drones are gaining traction, others like artificial intelligence (AI), internet of things (IoT), robotics and 3D printing remain underutilised or siloed. Barriers include fragmented technology integration, resistance to change, limited governance and widespread digital skills gaps, particularly among small firms and in regional areas. The study highlights the need for coordinated national strategies, improved training systems and collaborative ecosystems to enable sector-wide transformation. Practical recommendations include national digital standards, micro-credential training programmes and industry–government–academia partnerships. The findings offer theoretical and practical insights relevant to Australia and other advanced economies navigating Construction 4.0 transitions.

The construction sector is undergoing a significant transformation through Industry 4.0, which involves improved efficiency, sustainability and competitiveness across industries (Changali & Mohammad, 2015). The concept of Construction 4.0 emerges from this digital revolution, inspired by converging physical and digital trends and technologies within the architecture, engineering, construction and operations (AECO) industry (Sawhney & Riley, 2020). At its core, Construction 4.0 leverages technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data, internet of things (IoT), robotics, automation and building information modelling (BIM) to reshape traditional practices, aiming to boost efficiency, reduce costs and defects, and enhance quality, safety and client satisfaction (Brozovsky et al., 2024; Sony & Naik, 2020).

Several regions and countries have recognised the potential of Construction 4.0 to address productivity challenges and embraced this digital transformation (Gong et al., 2024; McKinsey Institutes, 2020; Shaharuddin et al., 2021). However, the implementation of Construction 4.0 remains context-dependent and varies across countries (Gündoğan et al., 2024; Osunsanmi et al., 2018).

In Australia, while the construction sector has recognised the potential of digital transformation, the adoption of Construction 4.0 technologies remains inconsistent and fragmented (Martin & Perry, 2019; Perera et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Australian Government initiatives, such as the Building 4.0 Cooperative Research Centre (CRC), launched in 2020, aim to accelerate digital adoption through collaborative research and development efforts (Perera et al., 2023).

Despite these efforts, challenges remain, particularly in the areas of skills development and organisational readiness for digital transformation (Siriwardhana & Moehler, 2024; Soltani et al., 2023). Organisational barriers such as cultural aspects (Maskuriy et al., 2019), financial constraints (Kim & Kim, 2019), insufficient management commitment (Siriwardhana et al., 2025) and workforce-related issues such as limited digital literacy (Heijden, 2023), outdated skill sets (Adepoju et al., 2021; Al Amri et al., 2021) and inadequate training structures (Mazurchenko & Zelenka, 2022) have been cited as major barriers to Construction 4.0 adoption.

While studies have explored Construction 4.0 adoption in various countries, such as the United Kingdom's focus on BIM (Newman et al., 2021) or Malaysia's exploration of adoption barriers (Almatari et al., 2024), few have addressed the Australian experience. Understanding the current state of technological adoption, the preparedness of organisations and the necessary skills and training is essential for guiding Australia’s construction sector towards successful integration of Construction 4.0 (Soltani et al., 2023).

This study provides an empirically grounded investigation of the determinants of Construction 4.0 adoption in Australia, focusing on organisational and workforce skills and training aspects via the following research question:

How do organisational and workforce skills-related determinants influence the adoption of Construction 4.0 technologies in Australia?

Unlike previous studies that have evaluated these aspects in isolation or within other national contexts, this research offers a holistic and empirically grounded analysis. A qualitative methodology using semi-structured expert interviews was adopted to capture in-depth insights from diverse professional perspectives. This approach allows for a nuanced understanding of sector-wide challenges and opportunities, contributing to evidence-based recommendations for policy and practice.

Literature reviewConstruction 4.0 technologies and the state of implementationConstruction 4.0 represents a fundamental redefinition of construction practices through the integration of advanced technologies such as building information modelling (BIM), internet of things (IoT), robotics, 3D printing, augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR), artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain and big data analytics (García de Soto et al., 2022; Oesterreich & Teuteberg, 2016). Appendix A describes common Construction 4.0 technologies. These technologies open up global opportunities for cooperation and collaboration, while also enabling the management of outcomes to mitigate negative impacts and ensure equitable distribution of benefits in the construction sector (Kiepas, 2021).

However, Construction 4.0 technologies cannot be implemented in isolation, and success depends on several factors. This includes the seamless integration of multiple intelligent technologies and infrastructure, organisational adaptability and human capacity to operate in increasingly complex digital environments (Olatunde et al., 2023; Zuniga et al., 2017). Technological infrastructure maturity must be complemented by organisational strategies and workforce capabilities that can flexibly adapt to evolving technological ecosystems (Sung, 2018; Xu et al., 2018).

Theoretical models such as the technology-organisation-environment (TOE) (Tornatzky & Fleischer, 1990) framework and the resource-based view (RBV) (Barney, 1991) offer conceptual foundations for understanding these dynamics. The TOE framework highlights that successful technology adoption is contingent on the technological context, organisational structures and human resource readiness (Awa et al., 2017). Workforce readiness, specifically the availability of digital skills and access to structured training, emerges as a decisive factor (Wasudawan & Sim, 2024). Socio-technical systems (STS) theory (Trist & Bamforth, 1951) further reinforces the centrality of workforce skills by arguing that technological and human systems must be developed interdependently. This study, therefore, conceptualises Construction 4.0 adoption not simply as a technological and infrastructural endeavour but as a socio-organisational transformation, where organisational determinants and workforce skills and training structures serve as the primary determinants of success.

Organisational determinants of Construction 4.0 adoptionSuccessfully implementing Construction 4.0 technologies is shaped not only by technical feasibility but more critically by a construction organisation's internal structure, strategic outlook and adaptive capacity (Nagy et al., 2021). From a TOE perspective (Tornatzky & Fleischer, 1990), organisational readiness, comprising change culture, resourcing capacity and governance, is a key enabler of digital transformation. Within this dimension, several organisational factors emerge as central to shaping the adoption and long-term sustainability of Construction 4.0 technologies.

A key determinant affecting the current state of Construction 4.0 within organisations is the level of technology implementation (Zhang et al., 2024). Studies emphasise that Construction 4.0 cannot thrive under isolated or ad hoc technological upgrades (Siriwardhana & Moehler, 2023; Soltani et al., 2023). Implementing Construction 4.0 requires interconnecting financial, marketing and production operations to create a unified system (Kiepas, 2021). However, the construction industry has yet to achieve this level of integration, with many organisations implementing technologies in silos without a clear strategy for full digital integration (Agostini & Filippini, 2019). This disconnect highlights wider challenges related to resistance to change within the organisation and a lack of cohesive strategic direction (García de Soto et al., 2022).

Adopting Construction 4.0 technologies also requires significant changes in organisational culture (Maali et al., 2020). Firms must build the capacity to sense, seize and reconfigure in response to disruptive change (Teece, 2007). However, construction firms with risk-averse or tradition-bound cultures often lack this adaptive capability, impeding the transition to integrated digital systems (Bhattacharya & Momaya, 2021). By contrast, innovation-oriented firms characterised by a shared mindset, risk-taking and collaboration are more likely to adopt new technologies (Wilson et al., 2023).

Strategic planning and governance is another critical factor (Demeter et al., 2020). Moon et al. (2015) emphasised that many organisations have not yet developed successful digital transformation strategies. Governance gaps, such as a lack of clear policies, data standards or accountability mechanisms, further impede Construction 4.0 diffusion. Institutional theory by Scott (2005) explains how the absence of regulatory pressures and formalised standards within the industry exacerbates these challenges, leaving firms without external incentives or benchmarks to adopt digital practices.

Investment capacity and resource allocation are fundamental to adopting Construction 4.0 technologies. Construction 4.0 technologies often require significant upfront capital and long-term strategic investment in infrastructure and workforce development (Hajirasouli et al., 2025). Organisations with weak financial planning or low innovation appetite may hesitate to commit resources, particularly when the short-term return of investment (ROI) is uncertain Renjen (2019). This results in a widening divide between larger, innovation-leading firms and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that struggle to compete digitally (Agostini & Filippini, 2019).

Furthermore, workplace-level dynamics such as employee resistance, lack of digital literacy and underdeveloped internal systems can undermine adoption even in firms with advanced infrastructure. Creating a workplace environment that promotes digital learning, experimentation and collaboration is essential, yet often overlooked (Karhapää et al., 2025). Leadership and management play pivotal roles in this process since effective digital transformation requires champions who can not only allocate resources but also shape mindsets, mitigate resistance and align teams behind shared innovation goals (Demeter et al., 2020; Zizic et al., 2022).

Effective collaboration and ecosystem engagement that supports Construction 4.0 technologies are also essential (Marcon et al., 2022). Poor coordination among project teams, clients and regulatory agencies leads to duplicated efforts and fragmented data environments (Li et al., 2023). By contrast, firms that participate in cross-sector partnerships and common data platforms can better align processes, improve interoperability and accelerate collective innovation (Marcon et al., 2022). The ability to embed these ecosystem capabilities reflects a higher level of digital maturity and systemic thinking.

Accordingly, organisational determinants of Construction 4.0 adoption are interconnected, spanning from internal capabilities such as strategic clarity, investment capacity and innovation culture to broader ecosystem coordination and institutional support.

Workforce skills-related determinants of Construction 4.0 adoptionThe successful implementation of Construction 4.0 technologies depends not only on organisational determinants but also on the capability of the workforce to adapt to and work effectively within digitally enabled environments. As the industry undergoes a significant transformation, there is a growing need to redefine the skills landscape to meet the demands of this digital era (Siriwardhana & Moehler, 2023, 2024).

From a TOE perspective, workforce skills and training align with human capital readiness, which directly influences the likelihood of successful technology adoption (Awa et al., 2017; Tornatzky & Fleischer, 1990). The RBV, while traditionally focused on firm-level tangible and intangible assets (Chung, 2022), can be considered a valuable lens in this context by conceptualising workforce competencies, including digital literacy, data interpretation and adaptive problem-solving, as core strategic resources that are rare, valuable and hard to replicate (Barney, 1991; Ellström et al., 2022Jin et al., 2025). In Construction 4.0 environments, where technologies rapidly evolve, the ability of firms to develop, retain and renew such human capital becomes a distinctive capability (Yang et al., 2022). This extends the application of the RBV beyond static resource inventories to include dynamic learning systems and training mechanisms as vehicles for sustainable competitive advantage.

In Construction 4.0 environments, these capabilities are not static. Rather, they must evolve in response to technological disruption (Hajirasouli et al., 2025). Studies by Adepoju and Aigbavboa (2021) and Alaloul et al. (2018) emphasise that traditional construction skill sets are increasingly inadequate, as emerging technologies fundamentally alter work practices and operational models. As such, skills disruption caused by technologies demands a proactive and systemic reconfiguration of workforce development approaches (Omotayo et al., 2024).

The importance of training is also emphasised within STS theory, which posits that human and technological systems must be co-developed to ensure long-term operational effectiveness (Trist & Bamforth, 1951). Without targeted investment in workforce development, technological integration remains fragmented and superficial (Haleem et al., 2024). Globally, countries have begun to address this challenge by identifying future-ready skill sets and embedding them into policy and training frameworks tailored to their socio-cultural contexts (Shet & Pereira, 2021; Siriwardhana & Moehler, 2024). These frameworks highlight both technical skills (e.g., digital tool operation, computational modelling) and non-technical skills (e.g., communication, collaboration, systems thinking and adaptability) as critical enablers of digital transformation (Siriwardhana & Moehler, 2024). Studies have further noted that workforce employability measured by digital skill levels, training access and skills application serves as a key metric of Construction 4.0 readiness (Maisiri et al., 2019; Tripathi & Gupta, 2021). To address these evolving needs, diverse educational and training approaches have emerged, such as learning factories, smart education and interdisciplinary programmes (Mei et al., 2023). Moreover, as highlighted by Chan and Moehler (2008), combining formal and informal learning mechanisms, such as mentoring, on-site workshops and digital micro-credentials, helps embed continuous learning into organisational culture. This aligns with the RBV, as firms capable of institutionalising learning mechanisms are better positioned to renew their human capital and adapt to rapid technological shifts.

Despite these advancements, the current skills landscape faces persistent challenges, including skills mismatches, limited training infrastructure, cost barriers and productivity slowdowns during training transitions (Neumann et al., 2021). These issues underline the importance of evaluating current skills readiness and designing targeted, scalable and context-specific training strategies. Therefore, understanding the existing skills landscape and implementing targeted training strategies are crucial for optimising the human resources required to navigate the Construction 4.0 transition.

Based on the literature findings, the conceptual framework in Fig. 1 illustrates the key determinants influencing the current state of Construction 4.0 adoption.

As per the framework, the state of Construction 4.0 adoption includes both technology adoption and infrastructure adoption, which together represent the core of how digital transformation is unfolding in the sector. These adoption outcomes are shaped by two major groups of determinants: organisational determinants and workforce skills-related determinants. Organisational determinants encompass factors such as technology implementation, organisational culture, strategy and governance, investment capacity, workplace readiness and collaboration within the ecosystem. Workforce skills-related determinants include the availability of Construction 4.0-relevant skills and the adequacy of training approaches and structures to support continuous upskilling. This study, therefore, explores how these interconnected dimensions collectively influence the current state of Construction 4.0 adoption in Australia. Further, this study applies and extends the TOE, RBV and STS frameworks to the underexplored context of the Australian construction industry, revealing how organisational, infrastructural and workforce-related factors interact to shape Construction 4.0 adoption.

MethodsThe study adopted a qualitative empirical research design to identify the current state of Construction 4.0 implementation. This choice reflected the existing gap in comprehensive and systematic studies on Construction 4.0, particularly concerning technology adoption, organisational factors and skills and training. Yin (2014) noted qualitative methods are well-suited for examining complex, evolving and contemporary phenomena within real-life social and organisational environments, making it an ideal choice for exploring the ongoing development and implementation of Construction 4.0.

A purposive sampling strategy was employed, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with experts in Construction 4.0, including practitioners and academics. These interviews aimed to gather insights on the current state of Construction 4.0 implementation, focusing on technology adoption, organisational aspects and skills and training. Participants were recruited via LinkedIn, resulting in a diverse sample of 23 professionals, including quantity surveyors (5), architects (5), project managers (5), engineers (5) and academic experts (3). According to Guest et al. (2006), a sample size of 9–17 participants is generally considered sufficient for purposive sampling, validating the adequacy of this study's sample size. Furthermore, data saturation was achieved during the interviews, confirming that the sample size was sufficient to capture the full range of relevant insights. The participants’ strong academic and industry backgrounds further supported the reliability and depth of their contributions.

Each interview lasted approximately 45 min to 1.5 h and was transcribed for thematic analysis and coding. Thematic analysis was chosen due to its flexibility in identifying, analysing and reporting patterns within qualitative data, making it particularly well-suited for exploring under-researched and complex phenomena such as Construction 4.0 adoption (Nowell et al., 2017). The interview questions were developed based on the literature review and conceptual framework, ensuring alignment with the study’s three key dimensions: technology adoption, organisational determinants and workforce skills-related determinants. The analysis was guided by the research questions and involved inductively coding the transcripts using NVivo 14 software. NVivo facilitates the organisation, categorisation and retrieval of data, enhancing transparency and traceability in coding (Houghton et al., 2016). Similar codes were grouped into broader themes reflecting key insights across technology adoption and organisational and skills-related determinants. The semi-structured interview format provided respondents with the flexibility to share their own narratives, which not only addressed the primary research question but also revealed additional insights. These emergent findings, while not directly related to the central research question, nonetheless contributed significantly to the thematic analysis. A detailed summary of participants’ profiles is provided in Table 1.

Details of participants.

As shown in Table 1, the study includes a diverse group of 23 participants. This diversity enabled the collection of rich, cross-disciplinary insights into the organisational, technological and workforce-related factors shaping Construction 4.0 adoption. Participants’ experience levels ranged from early-career professionals to senior experts with over 30 years of industry engagement, ensuring both current challenges and evolving trends were captured. The inclusion of both industry practitioners and academics further provided a balanced view between practical implementation and strategic or policy-level considerations.

ResultsConstruction 4.0 technology adoption in AustraliaPatterns of technology adoption in AustraliaThis analysis explores the utilisation levels of pivotal Construction 4.0 technologies such as BIM, AI, AR, VR, IoT, big data analytics, blockchain technologies, sensors, robotics, drones and 3D printing and their transformative impact on the construction industry.

The Australian construction industry exhibits a fragmented but evolving pattern of Construction 4.0 technology adoption. Experts identify BIM as the most commonly used technology, serving as a cornerstone for modern construction practices. However, its application often remains superficial. As P2 explained, “Just a few companies use BIM at the initial phase… they use a Revit model and claim that they use BIM, which is an absolute misconception”. Similarly, P12 noted, “Despite the widespread use of Revit among architects, the transition from design to construction often marks the end of its active use”.

Drones represent another widely adopted technology, particularly in surveying, laser scanning and site monitoring for high-rise and infrastructure projects. P7 shared, “We do drone flights on a daily or weekly basis to track earthwork quantities”. P17 reinforced this trend, noting that the declining cost of drones has enhanced their accessibility and uptake in Australia.

Technologies such as AR, VR and AI are in earlier stages of adoption. AR/VR applications are typically limited to design visualisation, training and safety simulations, with barriers cited in terms of cost and infrastructure. Nevertheless, P11, P13 and P17 considered that the current use of AI seems to be more theoretical than practical, noting it is mostly used in specific sectors and for specialised activities.

Big data is gaining traction, particularly for tasks such as forecasting, asset management and performance analytics. As P17 explained, “We ingest data into a lake and do analytics to depict trends rather than being reactive”, reflecting growing interest in data-driven decision-making. However, this application remains limited to larger and more technologically advanced firms.

Emerging technologies like IoT, robotics, 3D printing and blockchain are still largely in pilot phases. Respondents frequently cited cost, lack of workforce expertise and uncertain ROI as barriers. For instance, P17 noted that “IoT sensors have become a thing now, but we have not fully capitalised on their potential”, and P19 added that “Blockchain is being explored, but I don’t think that is going to take off anytime soon in the industry since we don’t have trained people to use it”.

Fig. 2 shows the overall framework of Construction 4.0 technology implementation in Australia as per the findings, with detailed comments from the respondents.

Importantly, while the uptake of individual technologies is increasing, the integration of these technologies into cohesive digital systems remains limited. Several participants emphasised this disconnect as a critical barrier to unlocking the full benefits of Construction 4.0. For instance, P9 observed, “There's an opportunity to bring much better collaboration, potentially right down through the supply chain”, yet noted that such opportunities remain largely unrealised due to siloed implementation. Technologies like BIM, AR and VR are often deployed independently rather than as interconnected platforms that support end-to-end workflows. Some participants shared examples of technology integration efforts. P6 described a process where BIM, robotics and generative scripting were combined to directly control robotic fabrication of steel and wall framing, which eliminated intermediate manual steps. P7 mentioned using AI and IoT tools to activate BIM models on-site, and P13 highlighted the use of VR to navigate BIM environments in a virtual setting. However, even in these cases, integration was not systematic but largely client-dependent, based on specific project needs, according to the participants.

Infrastructure adoptionTechnology adoption is inextricably linked to infrastructure readiness, which was emphasised across multiple interviews. Participants highlighted a range of infrastructure-related barriers that hinder Construction 4.0 implementation, from internet connectivity issues in regional areas to inadequate access to advanced software and hardware. P18 stated, “There are some parts of Australia where the internet connection is really bad…if your project is in a regional area, you won’t be able to use any of these technologies”. Similarly, P2 highlighted that the cost of infrastructure both in terms of licensing software and upgrading systems, is a significant challenge, especially for SMEs. Limited investment in digital infrastructure was seen as a core inhibitor, particularly when paired with the absence of supportive organisational and industry strategies. In this context, P14 described how their firm made strategic partnerships with United Kingdom- and United States-based organisations to facilitate infrastructure investment. Innovation and research and development (R&D) practices also contribute to infrastructure development. Some firms are experimenting with technology integration through R&D, but this remains isolated and client-dependent. P6 remarked, “Adoption is largely experimental”, while P8 noted that cost concerns deter clients from supporting the pilot projects. Furthermore, P17 observed that outdated contract models (e.g., requiring hardcopy drawings as deliverables) often limit the scope for digital innovation.

Organisational determinants of Construction 4.0 technology adoption in AustraliaLevel of technology implementationThe current state of Construction 4.0 implementation at the organisational level in Australia varies significantly, with larger organisations and infrastructure-focused companies reporting higher adoption levels. P3 and P14 mentioned that their organisations are often first to market with new technologies, investing significantly in digital infrastructure. However, P19 acknowledged that certain regions, such as the Northern Territory, are “very far behind in terms of Construction 4.0 implementation”, primarily due to limited resources and workforce availability. As P17 mentioned, “Consistency of implementation is something we struggle with, especially when shifting between manual and automated processes”. Further, P12 explained that the level of technology use is also influenced by the project features and client requirements, leading to varying levels of implementation even within the same organisation.

Change management/organisational cultureChange management is crucial for successfully implementing Construction 4.0 technologies in Australian organisations. P19 emphasised that "Resistance to change comes from both management and employees”. Among employees, fear of job displacement and a lack of understanding of new technologies are major barriers. As P4 observed, “Anytime something new is introduced, people feel like it will take away their job. … Workers don’t understand the procedures and benefits of these technologies”. By contrast, management's reluctance is often tied to financial concerns and client expectations. Respondents argued that a lack of awareness about the benefits of Construction 4.0 causes this reluctance. P3 echoed this view: “The problem right now with Construction 4.0 is that all the projects that use the concept are still ongoing, which makes it difficult to quantify and communicate the benefits”. The lack of awareness continues a cycle of inaction, as organisations cannot provide data to demonstrate the tangible benefits of embracing Construction 4.0. The need for a cultural shift within organisations is also evident, particularly in companies that have relied on traditional contracting methods for decades, making them resistant to the integrated, technology-driven approaches that Construction 4.0 requires.

Despite these challenges, there are signs of progress in some organisations. P7 noted that there are companies that “want to embrace the change and start to implement some of these processes because it makes their life easier”. P17 observed that change is more easily implemented at the project level, where there are fewer stakeholders to convince and the benefits of new technologies can be more directly experienced. However, as P18 warned, "If people are not ready to adjust, the threat is that it sends the organisation backwards”.

Strategy and governanceThe successful implementation of Construction 4.0 technologies depends heavily on having robust strategies and governance structures. While technologies like BIM benefit from established standards, other emerging technologies lack comprehensive guidelines, as noted by P16. Strategic planning within organisations also plays a critical role. According to P3, the success of technology adoption often depends on whether an organisation has a “short-term perception or a long-term perception”. Firms with a long-term view are more likely to invest in these emerging technologies. The Australian construction industry lacks mandated rules and regulations for Construction 4.0 technologies, which has slowed adoption across the sector, as noted by respondents (P3). Legal concerns also hinder progress, particularly around data ownership and intellectual property. P19 described this legal uncertainty: “One of the major threats is determining who is lawfully responsible if a technology goes wrong – whether it's the person who designed the technology, the technology itself or the person who implemented it". However, some local efforts, like the Victorian Digital Asset Policy (VDAP), are helping to drive standardisation, but a more coordinated, national approach is needed.

Investment and resourcesThe high initial investment costs associated with Construction 4.0 technologies are a major challenge for organisations, especially smaller ones. P14 noted, “Small organisations haven’t got the capital to invest as we have”. Even larger companies are reluctant to invest due to concerns over ROI, and many organisations lack the resources needed for these capital-intensive technologies, as per P20. Respondents agreed that broader government support and industry-level incentives are needed to overcome these barriers.

Workplace adoptionWhile many organisations are making efforts to create supportive environments, employee resistance and a lack of incentives hinder adoption. As P4 highlighted, “Many workers are resistant to adopting new technologies because they don't understand the procedures and benefits”. Incomplete internal systems further slow the adoption process (P7). Financial constraints also discourage staff from engaging with new technologies, as P9 pointed out: “We're not being paid to do it, and they don’t provide us necessary trainings”.

Despite these challenges, some organisations, like P15’s, are proactive, providing software and financial support to encourage adoption. However, digital workflow adoption is inconsistent, with many firms still relying on manual processes. As P5 noted, “Only a small percentage of organisations' workflows and tasks are digital, while much of our work remains paper-based”. Larger firms, like P14’s, have made significant progress, with automated workflows and integrated digital platforms being implemented across operations, fostering innovation and openness to feedback.

Collaboration and ecosystemsThe fragmented nature of the construction industry poses significant challenges as guidelines and roadmaps are often used separately by different teams, leading to poor integration. P1 noted, “It’s not working because when we are working together with different teams, they have different understanding and have different tools”. P10 emphasised the need for collaboration among engineers, financiers and government, stating, “It’s not one industry. It’s actually a bunch of industries…trying to do this without the engineers in the room is not going to work”. Miscommunication and different tools hinder collaboration and lead to inefficiencies (P12).

Another critical subtheme is the involvement of various stakeholders across the construction ecosystem. P9 stressed that clients and facility managers must be engaged early, as they bear the cost implications of technology adoption. P12 added, “Conversations need to happen between the designer, the surveyor and even the construction guys at the start of the project” to align all stakeholders from the outset and avoid misalignment in design, construction and management processes.

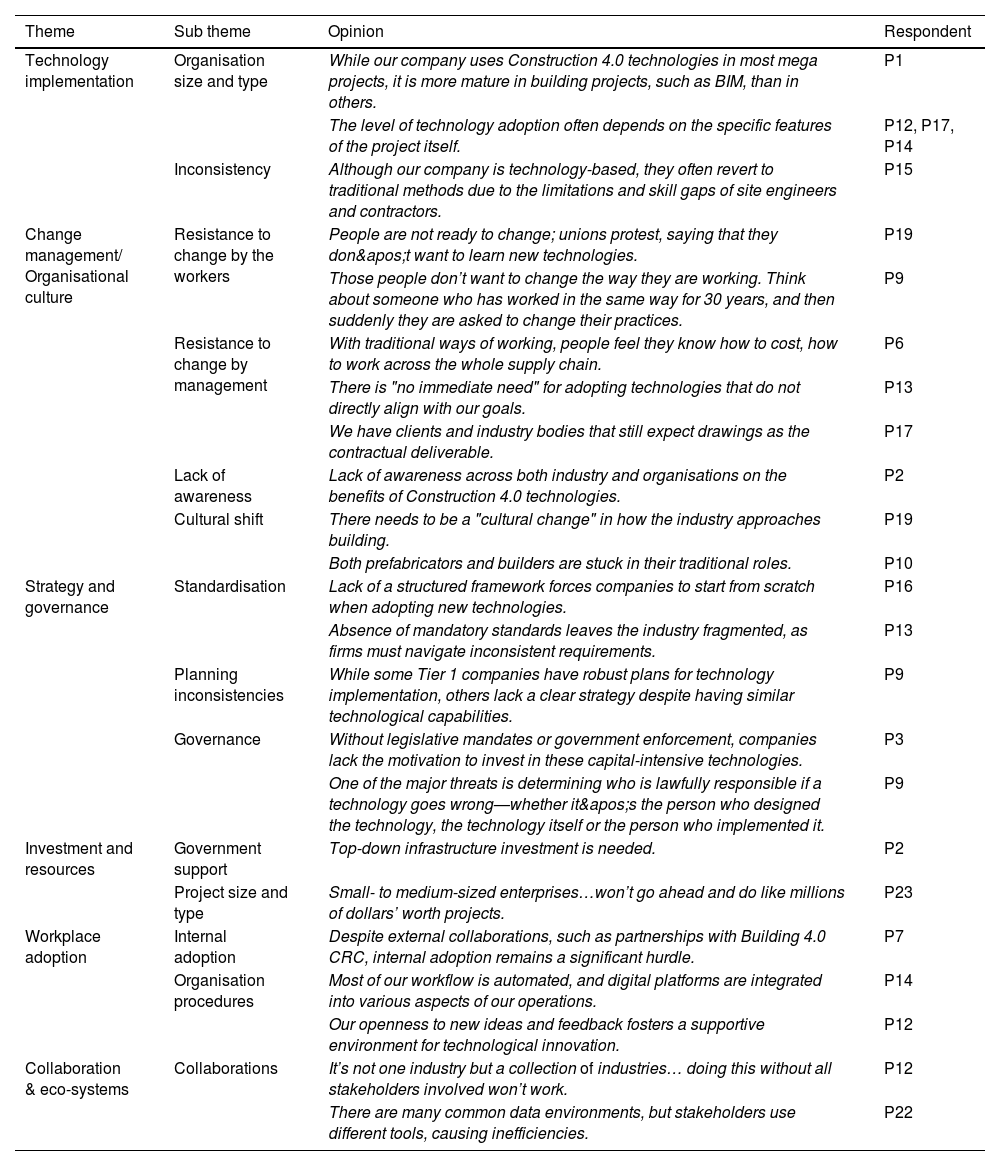

Table 2 presents the opinions of the respondents to support each theme.

Opinions of the respondents to support each theme in organisational aspect.

The thematic analysis revealed a consensus on needing the right skills to successfully navigate the rapidly changing technological landscape. The respondents unanimously agreed that skills are a “precondition to a successful implementation”, particularly in a fast-evolving environment where adaptability is key (P2, P11, P16). The results particularly highlight the need for IT skills not traditionally associated with construction, as argued by P7. Similarly, P9 emphasised that these new skills are unique and not typically taught in traditional construction education, leading to high demand. As a result, "hiring people with these skills is more expensive, and they are in greater demand" (P9).

The respondents highlighted that the lack of Construction 4.0 skills in the industry is a significant challenge in Australia. P2 noted “Skilled workforce who are familiar with implementing the technology and using the technology is limited”. P4 observed that the skills gap is evident at both the skilled/unskilled worker level and the management level. This deficiency is particularly concerning in areas where technologies generate vast amounts of data, yet nearly 90 % of this data goes to waste because “workers don't know how to use them properly” (P12). The lack of skills and knowledge prevents the effective use of even available equipment and sensors, leading to missed opportunities in leveraging these advances, according to P7. P11 agreed, stating that the industry struggles to find “good people to actually implement and manage” these technologies, with many workers opting to leave the construction sector for other industries that offer better opportunities to utilise their technological skills. This sentiment is echoed by P19, who underscored that without the “technological skilled people”, the full potential of Construction 4.0 remains untapped. Upskilling is critical, as without the right skill sets, the adoption of technologies like BIM remains limited, resulting in "a lot of missed value" across the industry (P16).

Respondents identified a range of skills necessary to implement Construction 4.0 in Australia, emphasising both technical and cognitive skills. They consistently mentioned the need for digital literacy and the ability to quickly adapt to new technologies (Adaptability) (P5, P16). As P2 suggested, professionals must possess flexible skills that can be updated continuously, rather than relying on rigid hard skills that may become obsolete as new technologies emerge. AI also plays a significant role, with P6 noting that while AI can automate tasks traditionally requiring advanced coding skills, there remains a critical need for experience and understanding of AI's outputs to effectively leverage its capabilities.

Other skills identified by respondents included data analytics, parametric or computational modelling, database integration and 4D modelling, specifically for BIM implementation (P17). P15 stated the importance of understanding programming and coding languages, such as Grasshopper, Autodesk's Lisp and Dynamo, to speed up design processes and leverage existing software more effectively.

Respondents also highlighted problem-solving and analytical skills, particularly in integrating new tools into traditional construction processes (P16). As the industry moves towards more digitalisation and the use of technologies like IoT, blockchain and robotics, the industry needs professionals who understand how to work with these technologies and incorporate them into existing workflows (P7, P8). Additionally, management skills remain crucial, especially in understanding how to integrate technologies into business operations meaningfully (P6). P11 reinforced this sentiment, pointing out the importance of requirements management, information management and contract administration so that technologies are correctly implemented and information is effectively exchanged between stakeholders. The complexity of managing these technologies also requires skills in data analytics, data visualisation and information management, as P13 and P11 noted, particularly in tasks such as processing and integrating data from drone technology into digital twin models.

Soft skills, particularly team management and leadership, are equally critical. P20 noted the need for digital skills that enable effective teamwork in this new environment, emphasising the importance of understanding how to work across teams in a digitally driven landscape. Communication skills are also vital, particularly in visual communication and clearly articulating complex information. P13 underscored the need to communicate ideas clearly and visually, especially when working with complex models like point clouds or photogrammetry, which require understanding how to combine and correlate them with existing models.

TrainingTraining is pivotal to successfully implementing Construction 4.0, as it equips the workforce with the necessary skills to navigate the complex and rapidly evolving technological landscape. While the importance of training is widely acknowledged, respondents noted they face significant challenges in providing the necessary industry-specific training programmes. As P2 highlighted, “It's a massive change. It's a big ask for people to expect them to go on board when they already are educated in a different way”. P5 stated that existing training avenues provided by organisations, suppliers and external institutions, including government bodies, offer valuable resources, but there is an urgent need to develop more targeted programmes that focus on applying these technologies in the construction environment.

Respondents’ experiences with organisational training for Construction 4.0 implementation in Australia vary significantly across three distinct categories: organisations that actively provide training, those that would like to provide training but are facing challenges, and organisations that do not offer training.

Several respondents reported that their organisations are committed to providing comprehensive training programmes. For instance, P11’s organisation develops its own training and invests in it, while also collaborating with contractors and external providers to equip staff with the necessary skills. Similarly, P12’s organisation readily sends employees to specialised training programmes like the Revit course and conferences such as the Hexagon Technology Conference, demonstrating a proactive approach to keeping their workforce up to date. Additionally, P19’s organisation has a "training budget for everyone" and a continuous improvement policy that encourages employees to innovate and suggest new strategies for which they can receive bonuses.

Some organisations stated they would like to provide training but struggle with challenges that hinder such programmes. For example, P2 noted that offering training can be overwhelming, especially when they must start from scratch to implement new technologies. Despite the willingness to train, the complexity and resource-intensive nature of setting up training programmes can be a significant barrier. However, the majority of respondents described environments where organisational support for training is minimal or non-existent, with many taking the initiative themselves. P6, for example, had to self-procure and teach themselves skills like Python and Dynamo, as their organisation did not provide any formal training. Similarly, P13 mentioned making "a lot of effort" in self-learning through online training on various topics, while P15 and P17 highlighted that they have pursued training in areas like AI, machine learning and BIM largely through self-directed research and development. P9 also pointed out that for professionals such as designers or architects in Australia, "trainings are seldom used", indicating a general lack of emphasis on formal training within certain segments. P8 highlighted the broader challenge within the sector, mentioning that "the availability of those training programmes" is a significant issue due to the industry's immaturity in establishing standardised training and skills development programmes.

In addition to organisational training, opportunities are emerging for training provided by suppliers, external institutions and government bodies. Suppliers are beginning to offer training, as noted by P8, although it is "not widespread" yet. Universities and other educational institutions are also contributing; P9 highlighted that these topics are being taught at the university level and mentioned their own participation in courses like AI image generation to improve efficiency. Similarly, P18 and P19 have engaged in BIM training and courses in data analysis, with P19 pursuing a Master’s in BIM from an external university. On the government side, P21 noted new training programmes being developed, particularly by agencies like the Office of Project Victoria (now part of the Department of Treasury and Finance), signalling the government's growing involvement in Construction 4.0 training initiatives.

Training challengesThe challenges surrounding training for Construction 4.0 implementation in the Australian construction sector are multifaceted, with cost and time being prominent concerns. P1 emphasised the significant financial and time burdens, particularly as new software versions are frequently introduced, which require continuous training. Time constraints further complicate the issue, with P4 and P17 explaining that busy schedules often leave little room for self-learning, leading many to rely on traditional methods. The unavailability of resource persons further complicates these trainings. P5 pointed out the difficulty in finding individuals who are both "willing and capable of actually training these solutions", given the complexity of the tools involved. P8 suggested that the government, industry and academia must collaborate more effectively to create a better regulatory and educational system, as currently "the government doesn't understand what is needed". P15 added, “While top-tier contractors might claim to be engaging with Construction 4.0 technologies, on-the-ground workers are still relying on the conventional methods” due to the absence of appropriate, tailored training. Additionally, the steep learning curve of new technologies presents a challenge in itself, as noted by P16, making it difficult for workers to quickly and effectively adopt these advances.

Suggestions for improved training structuresThe respondents emphasised several key areas for improving training, starting with specificity in training programmes. As P1 suggested, "more specific training" is necessary, especially when adopting new technologies, where understanding the principles behind the tools is crucial. Additionally, several respondents stressed the importance of integrating training into formal education. P2 advocated for introducing relevant methodologies at the bachelor's level, while P14 and P15 called for restructuring traditional engineering courses to better prepare graduates for industry demands. When considering these training structures, P15 highlighted that "traditionally, they choose one software to teach students", but argued that this approach is "no longer relevant", suggesting that training should instead focus on practices that can be applied to use different tools. P4 added that emerging technologies like VR/AR could be effectively used “to structure the education and training system”. Offering immersive and interactive learning experiences could better prepare students in the absence of work-based or experience-based learning. Moreover, P9 underscored the importance of collaboration between academia and industry. They argued that "working in partnership with the industry" is crucial so that what students learn in university is not only theoretical but also practical and relevant to real-world challenges.

Respondents such as P4 and P16 also supported continued self-learning, reflecting the rapid pace of technological advancement, although acknowledging the challenges this poses, given busy work schedules. On-the-job training was another recurring theme, with P7 and P9 underscoring its importance, while P12 stressed the need for industry-specific training, pointing out that current training programmes are often too generalised and not tailored to the unique needs of the construction industry. For instance, P12 highlighted that “when we take the trainings for data analysis, these programmes are mostly focused on other sectors such as the health sector”, making its application to the construction industry “somewhat useless or irrelevant”. This finding underscores the urgent need for training that is specifically designed for the construction industry.

Workshops and conferences were seen as valuable opportunities for staying informed and facilitating discussions, but respondents were concerned about whether these events reach the right audience. P12 argued events often attract “like-minded people”, such as academics and representatives from high-end geospatial or architectural companies, who discuss what “should be done” in an optimistic manner. However, these discussions rarely reach the individuals who can actually implement change on the ground, such as engineers and project managers working on construction sites. P10 echoed this sentiment by highlighting the importance of involving those directly engaged in the construction process, such as carpenters. For instance, P10 said, “Carpentry programmes aimed at accrediting carpenters to install new materials are a practical way to ensure that the right people receive the necessary training and support industry growth in these areas”.

Other ways that were mentioned to improve training included keeping curricula up to date with technological advances (as argued by P14, P16, P19 and P22) and advocating for government agencies to promote award schemes and certification processes that encourage adoption of Construction 4.0 technologies (as suggested by P18).

DiscussionTechnology adoptionThe data analysis presents the implementation of Construction 4.0 technologies within the Australian construction industry as a landscape of emerging and selective applications. While technologies like BIM and drones are somewhat accepted and recognised for their transformative potential across various project phases, others, such as IoT, AI, AR/VR, robotics and 3D printing, remain largely at the emerging or pilot stage, while blockchain technology is still in the proof-of-concept phase. Stakeholders demonstrate enthusiasm for these innovations, yet even the most widely adopted technologies, such as BIM and drones, are only partially implemented, indicating that adoption is still in its preliminary stages.

In countries such as Germany, the United States, Norway and China, BIM, drones, AI and cloud computing have reached market maturity and are widely integrated (Liu et al., 2022; Lloyd & Payne, 2019; Oesterreich & Teuteberg, 2016). By contrast, Australia's adoption is lagging due to fragmented implementation, infrastructure challenges and knowledge and skill gaps. Countries such as Malaysia and the United Kingdom have made more coordinated efforts in adopting disruptive technologies and fostering industry-wide strategies (Ślusarczyk, 2018), while Australia's progress is more client-dependent and less structured. This gap is particularly noticeable for modular construction and kitting strategies, which integrate technical interfaces across design, manufacturing and assembly stages. These approaches increase the complexity of coordinating BIM models, prototypes and on-site workflows, requiring specialised equipment such as cranes and skilled personnel who can manage system interfaces.

However, respondents are optimistic, acknowledging the need for further education and training, integration strategies and practical applications to fully harness the benefits of these technologies in Australia. This outcome aligns with the views of Osunsanmi et al. (2018), which state that, while construction professionals are eager to adopt modern technologies, they are often limited by low awareness. Similarly, in Australia, despite enthusiasm for technologies like BIM and drones, stakeholders face challenges in fully implementing them due to skill and knowledge gaps. For instance, many companies mistakenly equate using Revit or 3D models with full BIM integration, overlooking its potential for seamless collaboration and real-time data integration. This situation mirrors findings from research conducted in Finland, Norway and Sweden (Lidelöw et al., 2023), which identified the main obstacle to BIM implementation as a general lack of company-specific BIM awareness to translate technical possibilities into practice.

While literature highlights the transformative potential of these technologies (e.g., BIM, blockchain, robotics), their integration into Australian construction practices remains superficial or isolated. For example, although 3D printing promises to reduce waste and enhance customisation, its adoption in Australia is minimal due to regulatory uncertainty, investment risks and skill shortages (Soltani et al., 2023). This highlights a disconnect between theoretical propositions found in global literature and the actual state of readiness across many Australian firms.

The findings also underscore that infrastructure readiness is very important in shaping Construction 4.0 technology adoption across Australia, especially in regional and SME contexts. However, unlike countries with centralised infrastructure investment and national digitalisation plans such as Norway and Germany, where public–private partnerships and government funding have helped bridge the digital divide (Lloyd & Payne, 2019; Santiago, 2018), Australia's infrastructure development appears fragmented and uneven. The findings contrast with these cases by showing that Australian firms, especially SMEs, must often self-fund infrastructure upgrades or seek international partnerships to build capacity. This highlights a lack of coordinated national support, a gap widely acknowledged in the literature as a major barrier to scaling Construction 4.0 innovations (Allioui & Mourdi, 2023).

Innovation in the Australian construction industry remains in its early stages, largely due to clients’ reluctance to pilot new technologies and the associated costs and uncertainties. This issue is critical, as the ability to innovate and experiment with Construction 4.0 technologies is essential for long-term competitiveness and productivity (Bugeja et al., 2022). Globally, countries that lead in Construction 4.0 adoption, such as the United Kingdom and Norway, often have strong innovation cultures supported by government initiatives, R&D and industry collaborations (Lloyd & Payne, 2019). Australia's slower progress in innovation suggests a need for greater investment in R&D and collaboration between stakeholders.

Organisational determinantsThe impact of the organisational determinants on Construction 4.0 technology adoption reveals a divide between larger, infrastructure-focused organisations and smaller firms. Larger companies, particularly those involved in mega projects, invest significantly in digital infrastructure and lead the market in adopting Construction 4.0 technologies. This result aligns with international findings, such as those by García de Soto et al. (2022), where larger organisations are often better positioned to implement advanced technologies due to their available resources and long-term strategic outlooks. By contrast, smaller organisations, especially in more remote regions like the Northern Territory, face considerable challenges due to limited resources and workforce availability, a common challenge globally (OECD, 2019). This situation aligns with the fragmentation and plurality argument: Technology adoption occurs at different rates, particularly as SMEs face additional hurdles due to a lack of resources and remoteness, which further limit access to like training, infrastructure and skilled workers (Moehler et al., 2008). Meanwhile, larger organisations can adopt these technologies more readily, leading to a pluralistic system where some companies are highly advanced, while others are lagging (Mills et al., 2012).

Further, many respondents noted that the level of adoption varies not only between companies but also between projects, with more mature adoption in certain types of projects, like building and infrastructure projects utilising BIM. However, the selection of Construction 4.0 technologies depends on factors like project size, scope, type and client requirements. According to the findings, implementation decisions reflect resource limitations and uncertainties regarding productivity. This inconsistency mirrors findings in other studies, such as that by Agostini and Filippini (2019), which found that different sectors of the industry and even different departments within organisations struggle with uniform technology implementation.

Organisational culture plays a pivotal role in both facilitating and obstructing Construction 4.0 adoption. There is a clear resistance, particularly among older employees who fear job displacement, as well as from management, who are cautious of the financial and operational risks of integrating new technologies. The slow pace of organisational change, driven by a lack of awareness of the tangible benefits of these technologies, further exacerbates the reluctance. This result reflects a global issue of insufficient data to quantify and showcase the positive impacts of digital transformation (Soomro et al., 2024).

Change management and integration of new technologies are also hindered by the lack of structured governance and strategic frameworks. The absence of standardised regulations and comprehensive guidelines for many emerging technologies forces organisations to navigate the digital landscape without clear direction. This is a significant challenge, particularly in Australia, where government mandates for digital adoption are lacking. Similar issues have been reported globally; for example, Allioui and Mourdi (2023) noted that clear governance and industry-wide standards are essential for the successful adoption of Construction 4.0 technologies, yet many countries still face challenges in establishing these frameworks. In contrast, countries like Germany have made strides in creating standardised processes through industry partnerships and government policies, which have supported smoother transitions to Construction 4.0 (Santiago, 2018).

Workplace adoption further illustrates the complexity of integrating Construction 4.0 technologies, with some organisations successfully creating conducive environments while others face internal resistance or a lack of sufficient support. For instance, organisations that provide financial incentives and digital tools have seen better employee engagement in adopting these new technologies. Moreover, the fragmented nature of the industry, where different teams use varying tools and systems, further complicates collaborative efforts, a problem that has been noted in international contexts as well (Akyazi et al., 2020). Practical solutions noted by respondents included generating shared data environments, such as data lakes or central data warehouses within the organisation, as a contractual requirement.

Despite significant challenges, some Australian organisations, particularly larger infrastructure companies, are leading the way with strong investments in digital infrastructure and automation. Organisations that provide financial incentives and digital tools have seen better employee engagement in adopting new technologies. These firms are creating environments that encourage innovation, collaboration and the integration of advanced technologies, showing promise for broader industry adoption. Emerging cultural shifts and localised initiatives, such as the Victorian Digital Asset Policy, are also helping to standardise practices and support technological advances. While barriers like resistance to change, resource limitations and inconsistent implementation remain, these developments suggest that with continued efforts, Australian organisations have the potential to overcome these obstacles and emerge as leaders in Construction 4.0 adoption.

Skills-related determinantsA recurring lack of awareness and skills highlights a critical gap in the workforce’s readiness to adapt to rapidly evolving technologies. As the industry moves towards digitalisation, new skill sets are emerging that are more aligned with IT and digital disciplines, such as AI, data analytics, digital designing and programming, which are quite different from traditional construction skills. These new skills are in high demand, as noted by respondents, yet the construction sector struggles to develop and retain a workforce with these competencies. Often, skilled individuals leave the industry for others that offer better opportunities. This result mirrors the findings of previous studies, such as that of Maisiri et al. (2019), who emphasised that construction workers are generally unprepared for digitisation and industrialisation. Similarly, Adepoju et al. (2021) highlighted the global disparity between the demand for advanced digital competencies and the actual skill sets present within the construction workforce.

Importantly, the analysis spotlights the high demand for technical skills (digital literacy, data analytics, 4D modelling, parametric design and programming languages), as well as cognitive skills like adaptability, problem-solving and the ability to integrate new technologies into traditional workflows. Foundational work by Oesterreich and Teuteberg (2016) noted that these skills are indispensable for effective Construction 4.0 implementation, as they allow for advanced functions such as real-time decision-making, automation and enhanced project management. Management and soft skills, including leadership, communication and team management, are equally critical, particularly in navigating the complexity of new technologies and ensuring effective collaboration in digitally driven environments. While highly valued, these skill sets are scarce within the current workforce. This scarcity underscores the need for effective change management strategies to support workforce adoption, so employees have the skills to adapt to new technologies and workflows. The United States and United Kingdom emphasised the importance of digital literacy, adaptability and soft skills like communication and leadership and have structured frameworks addressing these needs (Speicher et al., 2019; UK Government, 2017). Germany focuses on multidisciplinary and cognitive skills for managing human–machine interaction and process optimisation and has forecast these skills will become more important as coding and programming skills become obsolete since industry practitioners have less need to manage 4.0 technologies and tools (OECD, 2019). These countries have implemented more structured training and skill development strategies, often supported by government policies and industry partnerships, compared with Australia (Siriwardhana & Moehler, 2023).

Interestingly, respondents provided a broad overview of the skills needed without focusing on specific technologies, perhaps indicating that many of these technologies are still in the early stages of adoption in Australia. That is, Construction 4.0 skills are still being shaped and formed by the ongoing evolution and maturation of the technologies. As these technologies become more integrated into the sector, they will give rise to both new skill sets and the need for evolved, more advanced capabilities.

The current state of training for Construction 4.0 in Australia highlights significant challenges but also offers opportunities for systemic improvements. One of the most pressing concerns is the scarcity of structured, industry-specific training programmes, reflecting the complexity and resource-intensive nature of developing such training initiatives – identifying the right content, technology platforms and delivery methods. Organisations struggle with the financial burden of investing in advanced technologies and workforce development. The literature echoes this challenge, with the OECD (2019) noting that globally, SMEs are at a disadvantage in adopting Industry 4.0 technologies due to financial and resource constraints.

This finding supports more collaboration between industry bodies, educational institutions like vocational education and training (VET) or technical and further education (TAFE) providers and government to develop structured, industry-specific training programmes. This would help mitigate the complexity of setting up training by standardising content, identifying practical approaches and ensuring alignment with industry needs (Oesterreich & Teuteberg, 2016). However, these initiatives remain limited and are not widespread. The Building 4.0 CRC in Australia is an example of how government bodies, private construction firms and educational institutions can collaborate to create and implement targeted training programmes. Similarly, the World Economic Forum's Digital Skills Framework guides industry and educational institutions in the United Kingdom to align training efforts with technological needs (UK Government, 2017).

The reliance on self-learning underscores the fragmented state of formal training programmes. Self-learning has become a necessary solution, providing accessible content through platforms such as YouTube and Google’s online courses. However, it cannot substitute for structured, industry-led training programmes that provide the depth of knowledge required for mastering advanced technologies like BIM, AI and data analytics (Trotta & Garengo, 2019).

The findings also support the need for industry-wide collaboration and government intervention. While isolated cases of successful training initiatives exist, particularly in larger organisations, they are not widespread. Companies often overlook that skilled performance, without the need for extensive on-the-job learning, can significantly boost productivity and quickly outweigh initial training costs. Integrated training models, such as learning factories or collaborative platforms, can help bridge the gap by offering hands-on experience with new technologies for on-the-job training (Kaasinen et al., 2020; Prodi et al., 2022). This naivety is evident as organisations tend to focus only on the upfront costs of training, neglecting the long-term benefits of skilled workers. As Moehler (2008) emphasised over a decade ago, while organisations recognise the importance of skills development, specific training can be difficult to identify and even harder to secure funding for. Despite the passage of time, little has changed, and the challenge remains, with organisations failing to truly meet the needs of the learner.

The adoption of Construction 4.0 technologies and supporting infrastructure in the Australian construction industry is shaped by a complex and interdependent set of organisational and workforce-related determinants. As conceptualised in the TOE framework, technology implementation cannot be isolated from the organisational environment; strategic planning, cultural openness to change, investment capacity and inter-firm collaboration all emerge as pivotal enablers or barriers. Simultaneously, aligned with the RBV, workforce skills, particularly in digital literacy, data analytics and interdisciplinary problem-solving, are critical strategic resources, yet remain underdeveloped across much of the sector. Importantly, the Australian context presents unique challenges and contrasts with international models: a highly fragmented industry structure, variable digital maturity between large firms and SMEs, limited national-level digital mandates and uneven infrastructure development, particularly in regional areas. These contextual features have given rise to client-dependent adoption patterns, inconsistent training provision and limited integration of emerging technologies. Moreover, while global literature often presumes centralised support and standardised governance (Allioui & Mourdi, 2023; Teixeira & Tavares-Lehmann, 2022), Australia's industry-wide transformation remains heavily reliant on isolated innovation champions and ad-hoc collaboration. These findings underscore that in Australia, the successful implementation of Construction 4.0 will depend not only on technological readiness but on a synchronised evolution of organisational systems and human skills requiring coordinated national policy, industry standards and capacity-building efforts tailored to its distinctive construction landscape.

Fig. 3 illustrates the key determinants influencing Construction 4.0 adoption in Australia. This extends the initial conceptual framework by empirically mapping the interrelationships between determinants of technology adoption, organisational factors, infrastructure readiness and workforce skills. Synthesising both enablers and barriers identified through thematic analysis, this diagram contextualises the theoretical constructs within the Australian construction sector, highlighting the dynamic and interdependent nature of these determinants in shaping Construction 4.0 implementation.

ConclusionThis study investigated the determinants of Construction 4.0 technology adoption in the Australian construction industry, with a particular focus on the interplay between organisational structures, workforce capabilities and infrastructure readiness. Guided by the TOE, RBV and STS frameworks and drawing on expert interviews, the study highlights how these dimensions interact to shape technology uptake and digital transformation within the Australian construction sector. It identifies key areas on which the industry needs to focus to enhance productivity, innovation and sustainability through Construction 4.0 technologies. The analysis of Construction 4.0 technology implementation in Australia highlights significant gaps. While some technologies, such as BIM and drones, are gaining traction, others like IoT, AI, robotics and 3D printing are still in the early stages of use. The research revealed fragmented implementation, with larger infrastructure projects leading the adoption, with smaller firms and remote regions lagging. Additionally, barriers to technology integration, such as inconsistent implementation across projects and a lack of industry-wide standards, hinder more widespread adoption.

Australian organisations face numerous challenges in adapting to Construction 4.0 technologies. Industry fragmentation, organisational culture, resistance to change, and the absence of structured governance frameworks are critical factors that slow down adoption, with many companies failing to invest in technology and training due to financial and operational risks.

Skills-related determinants in Construction 4.0 in Australia highlight an urgent need for improvement. A widespread lack of industry-specific training programmes means many organisations rely on self-learning or ad-hoc training provided by suppliers and universities. This situation has created a significant skills gap, particularly in digital literacy, AI, data analytics and other technical areas. The study emphasises the importance of collaboration between industry, educational institutions and government to develop structured training programmes that address the construction industry’s unique needs, focusing on practical, hands-on learning and industry-specific competencies.

This study advances extant theory in three distinct ways: First, this study extends TOE by emphasising the interdependency of technological, organisational and human (skills) systems in a fragmented industry context. Second, this study contributes to RBV literature by positioning workforce skills and training structures as strategic, renewable resources that shape competitive advantage in digital transformation. This application of RBV to human capital in Construction 4.0 offers a novel lens to view training investment and skills maturity as core enablers of innovation, particularly in sectors with dynamic technological change. Third, the integration of STS theory with TOE and RBV demonstrates that successful Construction 4.0 implementation depends on synchronised development of technology and infrastructure, organisational culture and human capital, offering a more holistic view than any single framework could provide. These theoretical refinements are not limited to the Australian context but apply to other advanced economies experiencing uneven digital uptake across heterogeneous industry segments. Methodologically, the study adopts a multi-dimensional qualitative approach, using expert interviews structured around the three-pillar framework (technology, organisation, skills), offering a replicable framework for future research. In terms of practical implications, the study identified several actionable priorities. First, addressing infrastructure disparity, especially in remote and regional areas, requires targeted investment, such as government-backed digital infrastructure grants or public–private partnerships models. Second, the current lack of regulatory guidance calls for the development of national digital standards and Construction 4.0 adoption roadmaps, similar to the United Kingdom’s BIM mandate or Singapore’s integrated digital delivery (IDD) framework, to ensure consistency, accountability and interoperability. Third, industry-specific training should be expanded through partnerships between TAFE/VET providers, universities and peak bodies. This includes the development of nationally endorsed micro-credentials focused on BIM, AI applications in construction and data-driven project management. Finally, in order to address ecosystem fragmentation, collaborative platforms involving government, industry, academia and technology providers should be established to co-develop Construction 4.0 strategies. National taskforces or regional hubs like the Centre for Digital Built Britain (CDBB) in the United Kingdom can support alignment, knowledge-sharing and coordinated implementation.

While this study is grounded in the Australian construction context, many of the identified organisational and workforce-related determinants, such as fragmented implementation, resistance to change and skills mismatches, are consistent with barriers observed in other countries undergoing Construction 4.0 transformation, such as the United Kingdom and Canada. As such, the findings offer valuable insights applicable to other developed economies with similar industry structures and policy landscapes. Future comparative studies could further validate and refine these conclusions across international settings. Future research should also consider longitudinal studies to monitor the progression of technology adoption over time and assess the economic advantages of early implementation. Additionally, further investigation is needed into effective strategies for supporting SMEs in their digital transformations, with particular emphasis on designing training programmes that address their specific constraints and needs.

Funding sourcesThis work was supported by the Monash Graduate Scholarship and Monash International Tuition Scholarship provided by Monash University, Clayton, Australia.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSenuri Disara Siriwardhana: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Robert C. Moehler: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Yihai Fang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Investigation.

The work described has not been published previously and it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Building 4.0 CRC, which provided research collaborative resources that enabled this work. We also wish to thank Jennifer Flynn for her professional proofreading and language editing services, which greatly enhanced the clarity and readability of this manuscript.