Edited by: Assoc. Professor Joaquim Reis

(Piaget Institute, Lisbon, Portugal)

Dr. Luzia Travado

(Champalimaud Foundation, Lisboa, Portugal)

Dr. Michael Antoni

(University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, United States of America)

Last update: November 2025

More infoNeighborhood disadvantage generates chronic adversity and negatively impacts breast cancer (BCa) survival. Greater social support may correspond with less adversity in BCa patients via physiological stress mechanisms. We evaluated the association between neighborhood disadvantage and serum cortisol, a physiologic marker of stress, and whether social support moderates this relationship in BCa patients.

MethodsWomen diagnosed with stage 0-III BCa post-surgery and before adjuvant treatment provided a late afternoon-evening serum cortisol sample and completed the Social Provisions Scale (SPS). Area Deprivation Index (ADI), a validated measure of neighborhood disadvantage, was determined using home addresses. Multivariable regression tested the relationship between SPS scores, ADI, and cortisol controlling for age, surgery type, and receptor status.

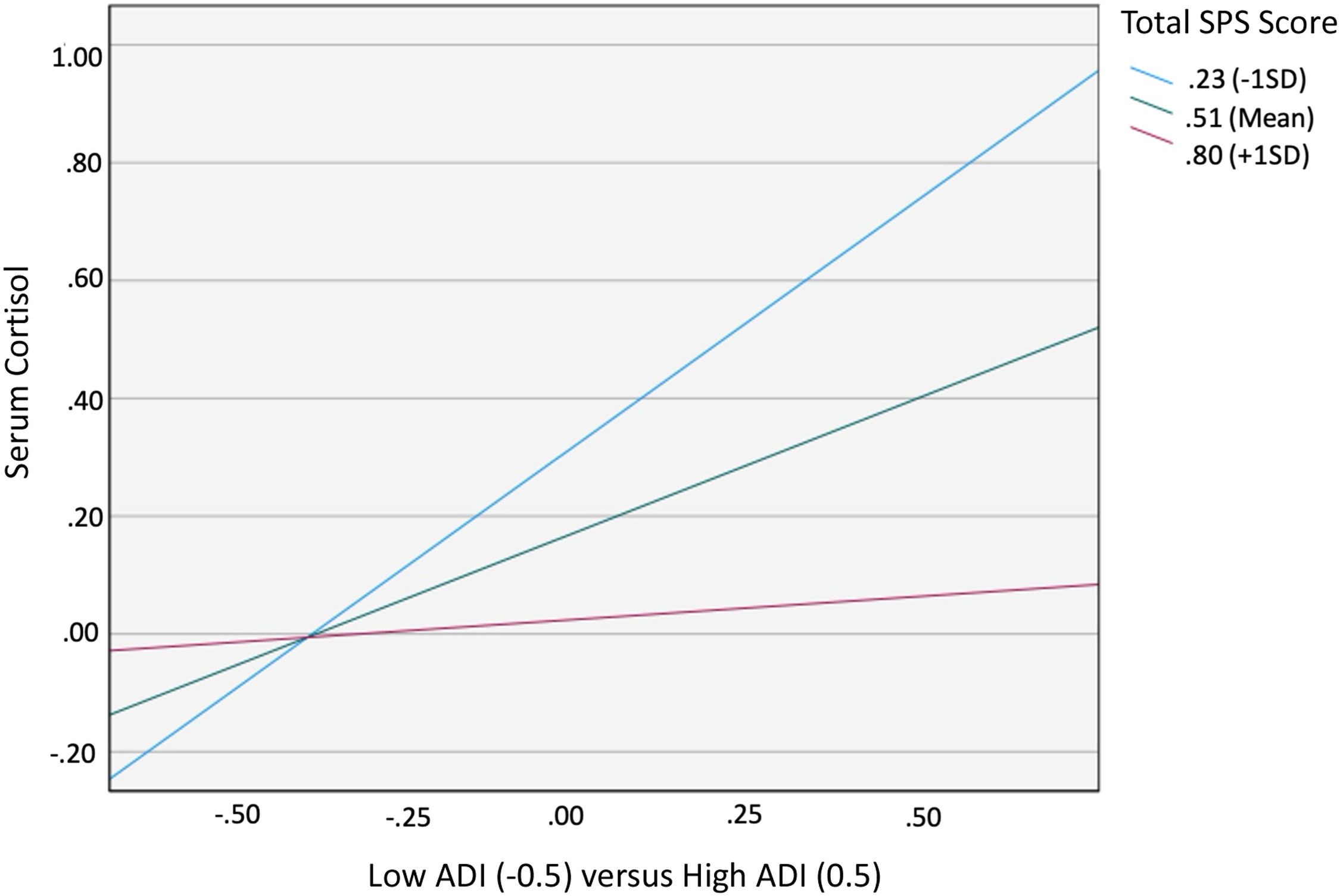

ResultsOf 178 participants, 24.7 % lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods (ADI 4 -10). High ADI (4–10) predicted greater cortisol (B = 0.417, 95 % CI [0.35, 0.800], p = 0.033). There was a significant interaction effect between ADI and SPS on cortisol levels (B= -1.776, 95 % CI [-2.974, -0.559], p = 0.004). Simple slope test showed the conditional effect of ADI on cortisol was statistically significant at low (M = 0.23; p < 0.001) and middle (M = 0.51; p < 0.05) but not high (M = 0.80; p = 0.901) SPS levels.

ConclusionSocial support moderates the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and serum cortisol levels in women with BCa undergoing treatment. While the neighborhood may generate elevated stress, social support is a modifiable element that may be protective. Secondary analyses indicated that perceiving higher levels of social attachment may confer this protective effect, suggesting future targets for interventions.

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of mortality among women, with outcomes influenced by a complex interplay of biological, social, and environmental factors (Diez Roux & Mair, 2010). In the United States specifically, socioeconomic and racial and ethnic disparities persist, even despite advancements in screening, diagnosis, and treatment (Goel et al., 2022). One important factor leading to these disparities is the intersection of structural racism and the neighborhood in which one lives (Bailey et al., 2021). Neighborhoods reflect complex environments with unique cultural, physical, and economic attributes, and their social and built environments contribute to one’s health (Diez Roux & Mair, 2010; Smith et al., 2017). Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood has been linked to an increased risk of aggressive breast cancer subtypes and mortality, yet the underlying mechanisms driving these associations are not fully understood (Saini et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2022). Disparities brought about by economic and residential segregation contribute to this disadvantage, leading to environments with higher rates of crime and violence, limited access to green spaces and healthy food options, and greater exposure to noise and chemical pollutants. Historically rooted racial residential segregation has led to certain racial groups being disproportionately impacted, and such conditions have been consistently associated with adverse health impacts, including cancer incidence and patient survival outcomes (Clark et al., 2013).

Chronic stress is posited as a key factor in the causal pathway linking neighborhood disadvantage with poorer breast cancer prognoses (Saini et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2021). Disadvantaged neighborhoods are epicenters of chronic stress, with stressors from the built and social environments contributing to the development or exacerbation of chronic diseases and mortality. These repeated stressors carry a psychological burden leading to activation of neuroendocrine stress responses orchestrated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (Cole, 2013, 2014; Goel et al., 2024a). Social adversity induced activation of neuroendocrine stress responses can subsequently influence the immune landscape and tumor microenvironment, potentially impacting cancer progression and survival (Antoni & Dhabhar, 2019; Chang et al., 2022; Goel et al., 2024a; Smith et al., 2017). A recent study found that breast cancer patients living in disadvantaged neighborhoods experienced higher levels of anxiety compared to those living in advantaged neighborhoods. Furthermore, breast cancer patients living in disadvantaged neighborhoods were also found to have elevated afternoon-evening serum cortisol levels, a biomarker of the body's stress response (Goel et al., 2023). Glucocorticoids, including cortisol, are known to influence cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment directly, encouraging tumor growth, impeding cell death, and fostering conditions favorable for cancer advancement (Flaherty et al., 2017; Obradović et al., 2019). In the context of cancer, dysregulated cortisol levels have been implicated in suppressing protective immune responses, promoting inflammation, and potentially aiding tumor cells in evading the effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy (Chang et al., 2022; Sephton et al., 2000).

Despite the well-documented association between neighborhood disadvantage and deleterious health outcomes in breast cancer patients, the potential for mitigating factors to alter these associations is not well understood. Social support, a critical component of an individual's social environment, has been shown to play a significant role in health and recovery from illness (Cole et al., 2015; Kroenke et al., 2006). Research has consistently shown that social support positively affects breast cancer outcomes. Greater social support, for example, is associated with better quality of life (Kroenke et al., 2006) and more resilience (Zhang et al., 2017). The Stress Buffering Hypothesis offers a theoretical framework to support this finding. This model suggests that individuals who encounter a stressful event are able to utilize social support at two points: the initial appraisal (limiting the interpretation of the event as “stressful”) and the reappraisal of the stressor (enabling individuals to reinterpret the “stressful” label). In changing one’s view of the stressor, they are able to cope more adaptively, engage in more positive health behaviors, and positively influence immune functioning (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Other studies have found important associations with social support and clinical outcomes such as breast cancer incidence and survival (Hilakivi-Clarke & de Oliveira Andrade, 2023; Kroenke et al., 2006). Lack of social support, or social isolation, has not only been associated with higher levels of cortisol in breast cancer patients, but also with activation of pro-inflammatory pathways, immunosuppression, and multiple metastasis-related processes in the tumor microenvironment (Aizpurua-Perez et al., 2024; Turner-Cobb et al., 2000). Despite compelling evidence of the deleterious effects of social isolation on breast cancer biology and outcomes, the role of social support as a moderator of the physiological impact of neighborhood disadvantage remains to be elucidated.

This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the moderating effect of social support on the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and afternoon-evening serum cortisol levels in patients who have recently undergone surgery for breast cancer treatment. We hypothesized that women living in more disadvantaged neighborhoods would have higher levels of afternoon-evening (PM) cortisol and that this association would be mitigated in those reporting greater social support. By examining the interplay between social and environmental stressors and physiological stress responses, we seek to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how social factors may influence patient outcomes. This information may help create enhanced targeted interventions to help improve health equity in breast cancer outcomes.

MethodsParticipantsThis study used baseline data from a clinical trial for stress management from 2006–2014 (National Institutes of Health Clinical Trial NCT02103387). Women living in South Florida aged between 28–80 years old and with stage 0-III breast cancer were enrolled in a clinical trial for stress management 2–10 weeks post-surgery and before initiating adjuvant treatment. Enrollment occurred via a community sampling method, utilizing local community clinics and health centers. Institutional review board approval was obtained, and all patients gave informed consent. Exclusion criteria included a previous diagnosis of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer), age >80 years, metastatic disease, prior hospitalization or diagnosis for psychosis, major depressive episode, panic disorder, suicidality, or substance dependency, and non-English fluency. Participants were also excluded if they had a comorbid major medical condition, were taking medications with known effects on endocrine functioning, or if they began adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation treatment. Patient addresses were used to determine the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), a validated measure of neighborhood disadvantage. Addresses were self-reported by patients and collected from the electronic medical record. All patients provided a late afternoon to evening serum cortisol sample (between 4pm–6:30pm; PM cortisol) and were administered a survey including the Social Provisions Scale (SPS) to measure social support. The SPS is a previously validated measure of social support with excellent reliability both on total score and individual item sub-scores (https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Ft06213-000).

MeasuresNeighborhood disadvantage. The ADI is a validated composite measure of multilevel measures of socioeconomic disadvantage and is calculated for each patient using census block group data from American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates. We used the 2015 ADI, a 5-year average of ACS data from the years 2011–2015, as earlier ADI measures were not publicly available (Kind & Buckingham, 2018). The ADI was determined using patient addresses and zip codes and calculated using the following ADI mapping atlas: https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/mapping. The ADI score (1–10) includes factors from the domains of income/employment, education, housing, and household characteristics. State deciles are typically categorized into tertiles where tertile 1 is the lowest ADI (most advantaged) and tertile 3 is the highest ADI (most disadvantaged) (Corkum et al., 2022). Consistent with previous analyses we grouped women into two categories to obtain reasonably sized groups for comparisons: those falling into the lowest tertile (ADI= 1–3) versus those in the top two tertiles (ADI= 4–10) (Goel et al., 2023). The lowest tertile was defined as living in an “advantaged neighborhood” and the top two tertiles as living in a “disadvantaged neighborhood” (Goel et al., 2023).

Social support. The Social Provision Scale (SPS) evaluates the extent to which participants believe their social interactions furnish them with support (Cutrona & Russell, 1987). The questionnaire consists of 24 items, each scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The total score ranges from 24 to 96, with higher scores indicating greater perceived social support. In addition to a composite score for overall perceived social support (SPS-Total), the SPS has six subscale scores corresponding to six distinct social roles: Attachment (ATT); Social Integration (SI); Guidance (G); Reliable Alliance (RE); Reassurance of Worth (ROW); and Nurturance (NUR). For this study, a modified version of the SPS scale was utilized, which included five new items intended to evaluate the Financial/Instrumental Support (FIS) extended to patients (Weiss, 1974). Also, the four items that constitute the Nurturance subscale were omitted since they refer to the respondent’s provision of support to others. The adapted version demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.912). Our primary social support moderators were conceptualized as Total Social Support (SPS-Total) and the Social Attachment (SPS-ATT) subscale based on prior literature relating these to biobehavioral processes and clinical outcomes in cancer patients (Lutgendorf et al., 2012, 2020). Both the SPS-Total and SPS-ATT subscale were treated as continuous variables for the purposes of the analyses.

Serum cortisol. Serum cortisol was used as a measure of physiological stress. A single blood sample was collected from each patient between 4–6:30pm to control for circadian fluctuations. This time window was chosen based on our prior work, which demonstrated good participant availability for assessments (Cruess et al., 2000; Goel et al., 2023; Phillips et al., 2008; Sephton et al., 2000; Taub et al., 2022). Furthermore, higher afternoon-evening cortisol levels can represent a dysregulation in diurnal cortisol slope, which has been linked to negative health outcomes in women with breast cancer (Sephton et al., 2000). Because cortisol levels can be affected by multiple lifestyle factors, we instructed participants to refrain from alcohol use, recreational drug use, and caffeinated beverages on the day of the blood draw. During assessments, a phlebotomist collected peripheral venous blood via venipuncture in red-topped vacutainer tubes, which contain no anticoagulants and allowed for the serum to be separated from cells when centrifuged. Cortisol levels in serum were measured by competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with kits from Diagnostic Systems Laboratories (Webster, Texas).

CovariatesCovariates for each model included age, type of surgery (lumpectomy vs. mastectomy), and breast cancer receptor status based on estrogen receptor (ER) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status. Receptor status was categorized into four groups: ER+/HER2-; ER-/HER2+; ER+/HER2+; ER-/HER2-. These covariates were chosen based on known confounders and subject matter expertise. Age was included as a covariate as cortisol levels are known to vary by age group (Moffat et al., 2020; Roelfsema et al., 2012; Wen & Sin, 2022). Race was not included as a covariate in our analysis due to the small number of Black or Asian patients in each subgroup.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using SPSS statistics (Version 28). First, data were screened for outliers and tested for normality assumptions. For continuous variables that did not follow a normal distribution, the Bloom transformation was applied, which is one of the best transformations for dealing with asymmetric distributions (Noel Rodríguez Ayán & Ruiz Díaz, 2008). ADI was treated as a categorical variable and did not require transformation. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to assess the influence of ADI, social support (SPS-Total score and the Social Attachment subscale), and their interactions on PM serum cortisol. Control variables included age, surgery type, and receptor status. Surgery type was dummy coded with lumpectomy as the reference category and receptor status was dummy coded with ER+/HER2- as the reference category. Education and household income were initially included as covariates but were excluded for model parsimony, as they did not improve predictive power; sensitivity analyses including both are reported in the Supplementary Materials. Interaction effects were evaluated using moderation analyses with the Johnson–Neyman technique (Miller et al., 2013). Statistical significance was set at a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Additionally, a confirmatory analysis was performed to test the effect of the Social Attachment subscale and exploratory analyses were performed to test the effects of other SPS subscales.

Data availabilityThe data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

ResultsModel assumptionsThe assumptions of multiple linear regression were examined for each model. Visual inspection of residual plots indicated no violations of linearity or homoscedasticity. The histogram and P–P plots suggested normally distributed residuals. Multicollinearity was not a concern (all VIF values < 2). Independence of errors was confirmed by Durbin-Watson statistics (range= 1.79–1.85).

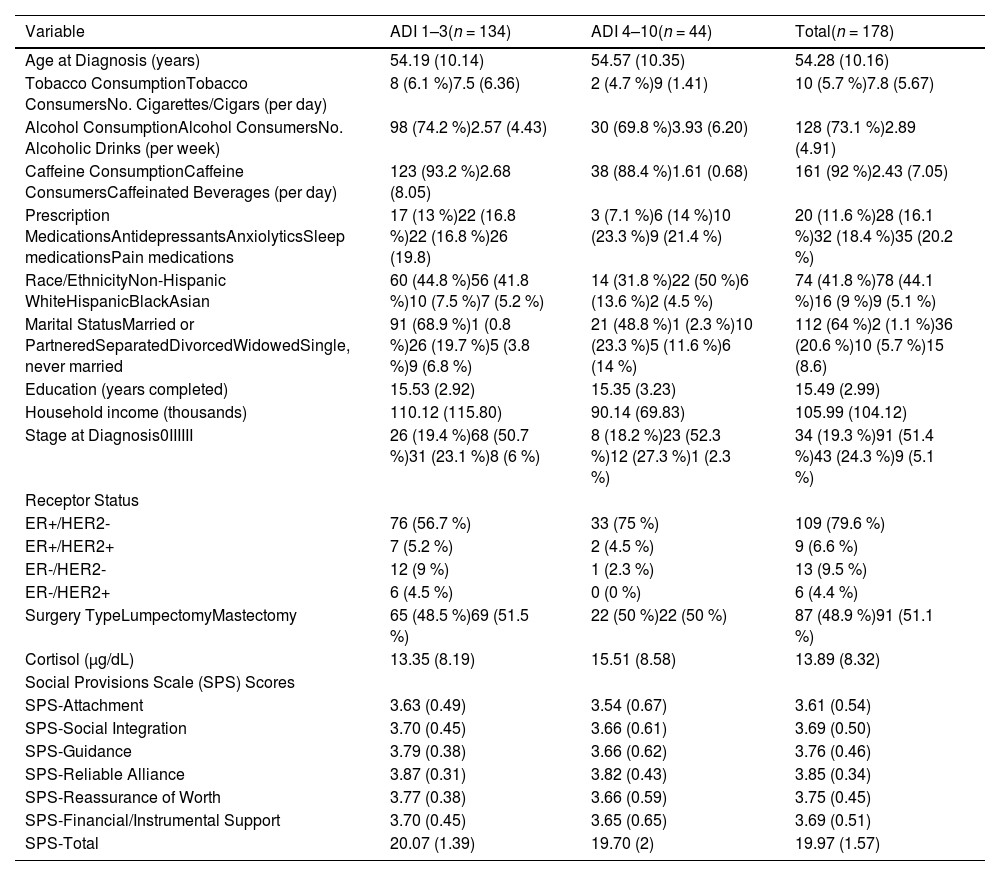

Patient demographics and tumor characteristicsThe demographics and clinical characteristics of the sample, along with study variables, are summarized in Table 1 for descriptive purposes. The cohort consisted of 178 individuals, with 134 (75.3 %) residing in advantaged neighborhoods and 44 (24.7 %) in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Additional descriptive statistics are included in Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics by ADI.

Note. ADI = Area Deprivation Index.

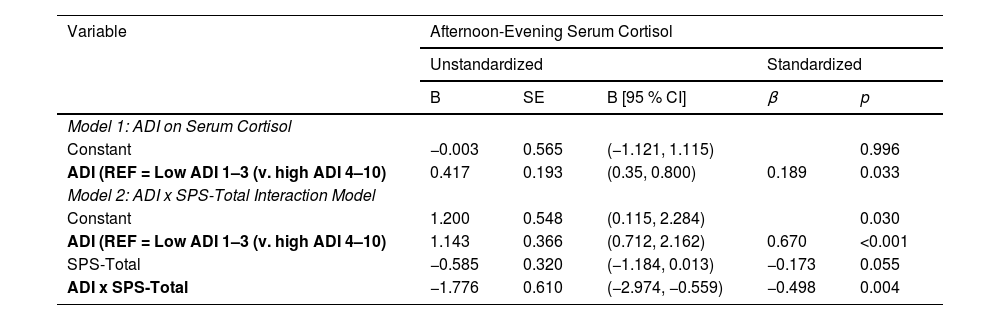

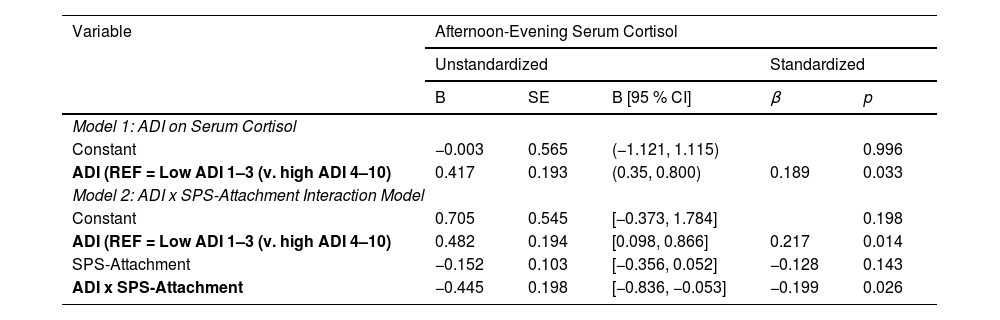

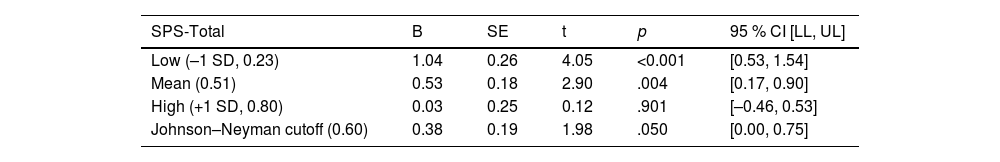

A statistically significant direct effect was found for ADI on cortisol (B = 0.417, 95 % CI [0.35, 0.800], p = 0.033). The interaction between ADI and SPS-Total on cortisol was significant (B= −1.776, 95 % CI [−2.974, −0.559], p = 0.004) with the overall regression analysis being significant (R2= 0.129, F [8118]= 3.342, p = 0.0002; Table 2). Specifically, the conditional effect of ADI on cortisol was significant at low (M = 0.23; p < 0.001) and middle (M = 0.51; p < 0.05) levels of SPS-Total, but not at high (M = 0.80; p = 0.901) levels. Thus, when SPS was average or below average (−1 SD), high ADI patients had higher cortisol levels than low ADI patients (Fig. 1). The Johnson–Neyman technique further indicated that the effect of ADI on cortisol was significant for SPS-Total values below 0.60 (≈58 % of the sample) but became nonsignificant above this threshold. Detailed conditional effects and regions of significance are presented in Table 4. There was no individual effect of education or household income on serum cortisol levels in the interaction between ADI and SPS-Total.

Multiple regression showing the relationship between ADI, SPS-total, and serum cortisol.

Total Model 1: Adjusted R2= 0.037, F [6, 127]= 1.851, p = 0.094.

Total Model 2: Adjusted R2= 0.129, F [8, 118]= 3.342, p = 0.0002.

Note. All models control for age, surgery type, and receptor status. ADI = Area Deprivation Index; SPS = Social Provisions Scale.

Moderating Effect of SPS-Total on the Relationship between ADI and PM Serum Cortisol. When SPS-Total was average or low (1 standard deviation below average), high ADI participants had higher cortisol levels than low ADI participants. There was no difference in cortisol for high vs. low ADI participants when SPS-Total was high (1 standard deviation above average).

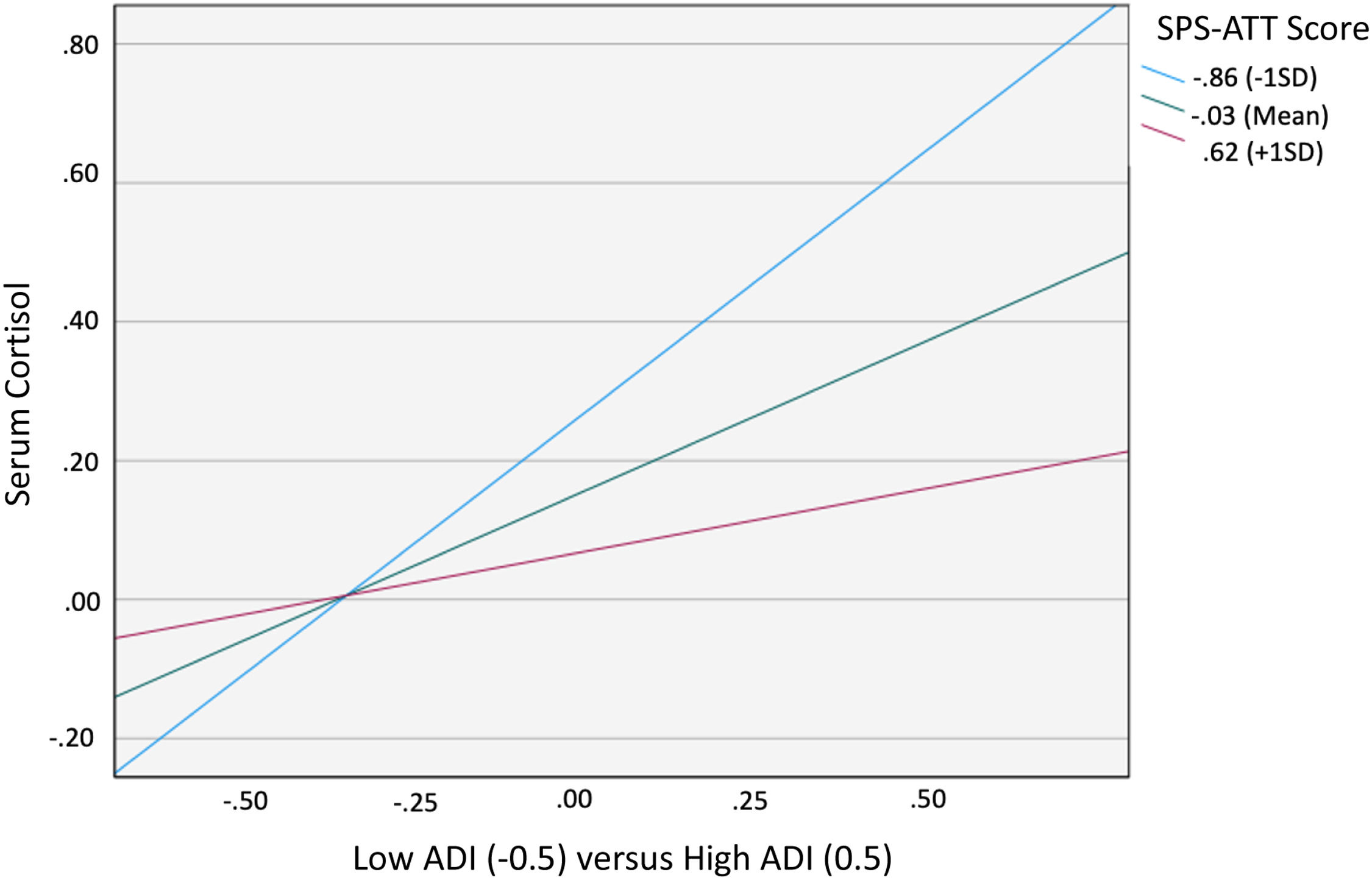

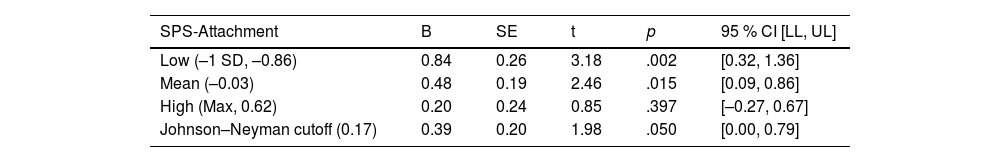

When examining the effects of social support attachment, the interaction between ADI and SPS-ATT was also significant (B= −0.445, 95 % CI [−0.836, −0.053], p = 0.026), with the overall regression analysis being significant (R2= 0.081, F [8, 120]= 2.402, p = 0.019; Table 3). Specifically, the conditional effect of ADI on cortisol was significant at low (M= −0.86; p = 0.002) and middle (M= −0.03; p = 0.015) levels of SPS-ATT, but not at high (M = 0.62; p = 0.397) levels. Therefore, as with SPS-Total, when SPS-ATT was average or below average (−1 SD), patients with high ADI (ADI 4–10) had higher cortisol levels than patients with low ADI (ADI 1–3; Fig. 2). The Johnson–Neyman technique further indicated that the effect of ADI on cortisol was significant for SPS-ATT values below 0.17 (≈43 % of the sample) but became nonsignificant above this threshold. Detailed conditional effects and regions of significance are presented in Table 5. Exploratory analyses indicated no significant interactions using other SPS subscales. There was again no individual effect of education or household income on serum cortisol levels in the interaction between ADI and SPS-ATT.

Multiple regression showing the relationship between ADI, SPS-attachment, and serum cortisol.

Total Model 1: Adjusted R2= 0.037, F [6, 127]= 1.851, p = 0.094.

Total Model 2: Adjusted R2= 0.081, F [8120]= 2.402, p = 0.019.

Note. All models control for age, surgery type, and receptor status. ADI = Area Deprivation Index; SPS = Social Provisions Scale.

Conditional effects of ADI on serum cortisol across values of SPS-total.

Note. The conditional effect of ADI on afternoon-evening cortisol was significant when SPS-Total was below 0.60 (approx. 58 % of the sample) but nonsignificant at higher values, indicating a moderating effect of social support; ADI = Area Deprivation Index; SPS = Social Provisions Scale.

Moderating Effect of SPS-Attachment on the Relationship between ADI and PM Serum Cortisol. When SPS-Attachment was average or low (1 standard deviation below average), high ADI participants had higher cortisol levels than low ADI participants. There was no difference in cortisol for high vs. low ADI participants when SPS-Attachment was high (1 standard deviation above average).

Conditional effects of ADI on serum cortisol across values of SPS-attachment.

Note. The conditional effect of ADI on afternoon-evening serum cortisol was significant when SPS-Attachment was below 0.17 (approx. 43 % of the sample) but nonsignificant at higher values, indicating a moderating effect of social support; ADI = Area Deprivation Index; SPS = Social Provisions Scale.

In this study, we validated our prior observations in an independent sample of breast cancer patients initiating treatment for non-metastatic disease showing that greater neighborhood disadvantage is associated with greater afternoon-to-evening cortisol levels (Goel et al., 2023). We also observed, as hypothesized, a protective effect of social support on the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and serum cortisol levels. Our findings lend support to the hypothesis that social environments characterized by high levels of social support may be associated with lower physiological stress responses typically exacerbated by disadvantaged neighborhoods. This may in turn potentially blunt some of the negative biological consequences that may lead to more aggressive tumor biology and poorer clinical outcomes. Additionally, we found that the social support attachment subscale was a significant moderator of the neighborhood disadvantage and serum cortisol association. Previous research among cancer patients suggests that social attachments have a stress buffering effect, in which they downregulate hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis activity and fight-or-flight responses (Lutgendorf et al., 2012). Given that the attachment subscale of the SPS is most closely tied to emotional social support and the perception of close relationships. Emotional support can be distinguished from other forms of support (e.g., tangible aid, instrumental support, and informational support) that are often incorporated into broader measures of total social support. Our finding is in line with prior work and highlights targetable areas for future interventions.

While several studies have shown that neighborhood disadvantage is associated with increased or dysregulated cortisol patterns, especially in women (Barrington et al., 2014; Karb et al., 2012), only one recent study has shown neighborhood disadvantage to predict greater cortisol levels in an independent sample of breast cancer patients (Goel et al., 2023). The role of cortisol in cancer biology and survival is an important area of focus. A study in a cohort of ovarian cancer patients observed that for every one standard deviation increase in evening cortisol there was an associated 46 % greater likelihood of mortality (Schrepf et al., 2015). Additionally, that study found increased IL-6 associated with increased cortisol levels, further highlighting the activation of systemic pro-inflammatory pathways associated with increased cortisol (Schrepf et al., 2015).

Cortisol can also directly affect the tumor and tumor microenvironment through binding to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Animal models have found that glucocorticoids inhibit not only apoptosis, but also paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in breast and gynecological malignancies (Huang et al., 2000). Furthermore, GR activation may coregulate beta-adrenergic receptor activity, suggesting that cortisol can facilitate sympathetic nervous system signaling in tumor and stromal cells (Basarrate et al., 2024). For example, cortisol has been shown to affect cancer-associated fibroblasts, which are involved in cancer growth and metastasis (Hidalgo et al., 2011). Moreover, cortisol has been shown to induce insulin resistance in adipocytes within the mammary microenvironment, leading to the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and growth factors that facilitate tumor metastasis through processes such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Shi et al., 2019). This is further compounded by the adipocytes' increased expression of the 11β-HSD1 enzyme, which enhances local cortisol levels and potentially intensifies tumor signaling (Volden & Conzen, 2013). Important in the context of this study and these findings is that prior work from our team has shown that greater neighborhood disadvantage is associated with greater expression of SNS-related transcriptional factors in the breast cancer tumor microenvironment (Goel et al., 2024b). Knowing the deleterious effects of cortisol on breast cancer tumor biology highlights the importance of our study’s evaluation of moderating factors that have the potential to decrease cortisol levels.

Our finding that greater social support was associated with lower levels of serum cortisol for those in more disadvantaged neighborhoods complements current literature on social support and cortisol in breast cancer patients. Notably, studies have shown the detrimental biological effects of a lack of social support, or social isolation, on multiple aspects of tumor pathophysiology and clinical outcomes, including tumor biology, cancer incidence, and mortality. Lower social support was associated with increased risk of mortality (Lutgendorf et al., 2012) and increased EMT polarization (Lutgendorf et al., 2020) in ovarian cancer patients. In breast cancer, studies have shown social isolation to be associated with altered gene expression and increased risk of developing aggressive metastatic forms of breast cancer (Volden et al., 2013), including upregulated expression of genes involved in EMT. Interestingly, most of these studies only used the Attachment subscale of the SPS in their social isolation measures, which underscores our focus on this specific subscale in our analysis (Bower et al., 2018; Lutgendorf et al., 2020).

These biobehavioral studies contextualize our findings that neighborhood disadvantage acts as a chronic social stressor that may be associated with greater levels of biological markers of stress, an association that may be mitigated by social support and specifically social attachments. While prior studies have shown that neighborhood disadvantage is associated with higher cortisol levels and increasing social support is associated with decreased cortisol levels (Turner-Cobb et al., 2000), the present study is the first to demonstrate the possible contribution of social support on the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and cortisol in breast cancer patients.

From a psychological standpoint, social support is a major contributor to patient resilience, which is a measure of one’s ability to cope successfully with stressful life events, such as a cancer diagnosis. On a practical level, social support may be protective against the deleterious effects of neighborhood disadvantage beyond biopsychological wellbeing by also helping address access to care barriers. Especially considering our findings regarding the SPS-ATT subscale, close social relationships on an individual and interpersonal level can help address social needs that affect access to care such as transportation and childcare. On a community level, social support can increase access to shared health resources, health information, and shared cultural norms around healthcare such as trust in medical providers (Ahern & Hendryx, 2003). Neighborhoods, through the built and social environment, can help reinforce feelings of closeness and attachment with one’s neighbors (Thompson et al., 2016). Social support throughout a neighborhood can be strengthened by shared culture, language, and values such as those living in neighborhoods with a high density of a particular race or ethnicity, such as Hispanic and Asian ethnic enclaves and communities (Yang et al., 2020).

This study was limited by a cross-sectional design and a lack of information on cortisol levels over the course of treatment. In addition, the majority of patients had stage I and II disease, were White, and lived in advantaged neighborhoods, thus limiting generalizability. However, our population consisted of a large proportion of Hispanic patients compared to other regional and national studies (Duma et al., 2018). Furthermore, the catchment area for our institution included four South Florida counties (Miami-Dade, Monroe, Broward, and Polk) that together make up >30 % of the total Florida population. We attempted to mitigate the effects of patients generally living in advantaged neighborhoods on the power of our analyses through our use of ADI grouping.

We were also limited in data availability, such as the inclusion of other markers of physiological stress including neuroendocrine or inflammatory markers. We also lacked data related to physical activity, sleep, comorbid psychiatric symptoms, and caregiving burden, which may have been important potential confounding variables to include in our analyses. Additionally, we also lacked access to detailed comorbidity data, as patients were primarily recruited at community clinics where complete medical histories were not collected. Therefore, results should be interpreted with these limitations in mind. However, according to recent literature, the majority of cancer clinical trial recruitment occurs within major academic medical centers (Copur, 2019) and the overwhelming majority of cancer patients across the United States receive their care in the community setting (Tucker et al., 2021). Thus, even though complete medical histories were not collected, a strength of our study is the community sampling, which increases diversity of clinical trial participation and thereby increases the generalizability of our findings. Another limitation of our study is that we were not able to fully confirm the accuracy of patient addresses. While addresses were self-reported and assumed to be true, it is possible that addresses could be falsified. Additionally, this study did not control for the length of time a patient lived at a particular address. While such length of time information may influence the level of social stress one receives in their environment, this information was not collected for this analysis. However our prior work on examining the effects of ADI and other structural indicators in South Florida breast cancer populations indicates that residence is reasonably stable with a mean time lived at current address of 17.9 ± 14.2 years (Goel et al., 2024b).

Another important limitation is that clinical trial populations often do not adequately represent the broader population, and in the context of this study specifically, may differ from the general population in characteristics that impact serum cortisol levels (Tan et al., 2022). This study did not have a non-trial group to which to compare serum cortisol levels. Furthermore, cortisol levels are highly variable, and a serum level measured at a single point in time may not provide complete clinical utility. However, our study attempted to reduce variability by limiting the blood sampling window to 4–6:30pm. Our study also required participants to refrain from behaviors that may influence cortisol levels, including alcohol and drug use and the consumption of caffeinated beverages on the day of blood draw. While serum cortisol levels may allow us to explore a mechanistic connection between neighborhood disadvantage and breast cancer outcomes, tracking cortisol levels over time and correlating differences in cortisol levels with differences in clinical outcomes is an important next step. Nevertheless, this study, to our knowledge, is the first to assess the moderating effect of social support on the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and serum cortisol levels in breast cancer patients initiating treatment.

Our results warrant further investigation in a larger and diverse cohort from more disadvantaged neighborhoods. A strength of our study is the recruitment of women in the 2–10-week post-surgical period, a time when they had not yet begun adjuvant therapy regimens, thus giving us measures of their stress state and HPA axis function free of the confounding effects of chemotherapy and radiation which can include the use of glucocorticoid therapy. Another strength is the use of ADI, which compared to other indices, provides detailed information integrated in the housing domains; and a smaller geographic measure in the census block group versus the broader census tract (Kind & Buckingham, 2018). Future directions should include longitudinal information on cortisol patterns and identifying other potential psychosocial moderators (e.g., coping skills) for additional intervention targets.

Our findings provide useful information for future interventions aimed at enhancing social support and well-being which could impact the physiological consequences of stress and adversity, potentially influencing cancer progression and patient recovery. Individual-level interventions such as cognitive-behavioral stress management can enhance social support by providing psychoeducation around social support, in addition to teaching assertiveness and interpersonal communication skills to strengthen social connections. These could be delivered in individual or group format and in clinical as well as community settings. Moreover, our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of how social determinants of health, such as neighborhood disadvantage and social support, intersect to influence biological processes relevant to cancer progression. Increasing social support in the built environment is a key focus of health organizations like the Center for Disease Control and the World Health Organization as well as a goal for the U.S. Healthy People 2030 (Gómez et al., 2021). Interventions to improve social cohesion in individual and built environments have already shown promise. Psychological therapies can target individuals while community-based support groups, physical activities, and education can enhance the built-environment (Thompson et al., 2016). Studies that have employed group-based interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management (CBSM) have shown to contribute to increases in perceived social support and reductions in serum cortisol (Phillips et al., 2008). To structurally influence the social environment, changes to the built environment such as creation, expansion, and improvements on public spaces such as parks and community buildings as well as urban planning that increases mobility and facilitates community interaction and participation can drive meaningful change.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that social support influences the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and serum cortisol levels in women with breast cancer. First, we replicated prior findings from an independent sample that women from more disadvantaged neighborhoods undergoing breast cancer treatment have higher serum cortisol levels, reflecting greater physiological stress. Second, these effects were only found in women reporting lower social support levels. Specifically, while these patients’ neighborhood social environments may generate elevated stress, social support, a modifiable element, when lacking may amplify this effect and when high may be protective. The findings also indicate that perceiving higher levels of social attachment may confer this protective effect, suggesting that this element of social support may be a target for future interventions. Future studies associating social support, as well as other resiliency factors, with clinically relevant outcomes are warranted.

FundingResearch reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R37CA288502. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Goel reports grants from NIH/NCI R37CA288502, NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748, Breast Cancer Research Foundation, American Surgical Association Fellowship Award, American Society of Clinical Oncology Career Development Award, Society of Surgical Oncology, and V Foundation award during the conduct of the study. Dr. Antoni is funded by grants from the NIH (R01CA206456, UG3 CA260317, R61 CA263335, R37 CA255875, R37 CA288502-01), PCORI (AD-2020C3-21171), the Florida Breast Cancer Foundation, and a Cancer Center Support Grant (1P30CA240139-01). Dr. Taub receives support from the UAB O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Aizpurua-Perez would like to thank the Basque Government predoctoral grant PRE_2020_2_0047 that supported her research until January 2024.

Dr. Antoni is a paid consultant for Blue Note Therapeutics. He is also the inventor of Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management, filed with the University of Miami as UMIP-483, which is licensed to Blue Note Therapeutics. Dr. Taub reports past employment and consulting fees from Blue Note Therapeutics (now dissolved). Dr. Taub also reports consulting fees from Swing Therapeutics, unrelated to the current work. The other authors declare no disclosures or potential conflicts of interest.