Edited by: Assoc. Professor Joaquim Reis

(Piaget Institute, Lisbon, Portugal)

Dr. Luzia Travado

(Champalimaud Foundation, Lisboa, Portugal)

Dr. Michael Antoni

(University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, United States of America)

Last update: November 2025

More infoDepression is common among cancer patients, adversely affecting treatment adherence, toxicity, and quality of life (QoL). However, its course during adjuvant therapy and its impact on outcomes in resected cancer remain poorly understood. This study evaluated changes in depression from treatment initiation (T1) to six months later (T2) and examined associations with demographic, clinical, and psychological factors, treatment-related toxicities, and QoL.

MethodsIn this multicenter, prospective observational study, 927 patients with resected, non-metastatic cancer receiving adjuvant treatment were enrolled. Depressive symptoms were measured using the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) at T1 and T2. Patients were classified as “never” (no symptoms at T1 or T2), “new-onset” (absent at T1, present at T2), “remission” (present at T1, absent at T2), or “persistent” (present at both time points). Treatment-related toxicities were evaluated according to CTCAE v4.0, and QoL was assessed with the EORTC QLQ-C30.

ResultsAt T2, 50.8% of patients remained asymptomatic, 12.3% experienced remission, 23.4% exhibited persistent depression, and 13.5% developed new-onset depression. Persistent depression was more common among women, younger patients, those without a partner, and breast cancer patients. Patients with persistent symptoms showed significantly higher toxicities—including hematologic, digestive, and neuropathic events, as well as increased asthenia (p < .001)—and poorer functioning with greater symptom burden, resulting in markedly reduced overall QoL. In multivariate analyses, baseline depression and ECOG performance status were the main predictors of depressive symptoms at six months, while age predicted changes over time; other sociodemographic or clinical factors were not significant. Logistic regression confirmed that younger age, female sex, breast cancer, and poorer ECOG were associated with higher odds of persistent depression compared with never-depressed patients.

ConclusionBoth baseline depression and functional impairment (ECOG) are independent predictors of depressive symptoms during adjuvant therapy. Persistent depression is significantly associated with increased treatment toxicity and poorer QoL in patients with early-stage resected cancer, highlighting the need for routine screening and early psychological intervention during adjuvant treatment.

Cancer is among the most prevalent diseases and remains a leading cause of death worldwide. Its incidence has risen steadily in recent years, reaching 18.1 million cases globally in 2020, with an estimated increase to 28 million cases by 2040 (Ferlay, 2022; Siegel et al., 2023). Beyond its physical consequences, a cancer diagnosis, the course of the disease, and the side effects and sequelae of treatment are often perceived by patients as significant stressors. These experiences are associated with a high risk of psychological distress, particularly anxiety and depression, which occur more frequently in cancer patients than in the general population (Hinz et al., 2010; MR DiMatteo et al., 2000; Pitman et al., 2018; Vyas et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2017). Depression is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms in cancer patients. A systematic review and meta-analysis in patients with both localized and advanced cancer stages reported a prevalence of 15 % for major depression, 20 % for minor depression, and 5 % for anxiety (Mitchell et al., 2011). Depression is most frequently diagnosed during the acute phase of cancer treatment, with up to 50 % of patients experiencing depressive symptoms within the first year after diagnosis (Burgess et al., 2005). These symptoms can persist from 4 to 18 months following the completion of treatment, as patients transition from the threat of cancer therapies to the emotional impact of having faced a potentially life-threatening event (M et al., 2008).

The prevalence and intensity of depression may vary depending on factors such as tumor type and prognosis (Leach et al., 2008), treatment-related symptoms, altered body image, female gender, younger age, and lack of social support (Walker et al., 2014). For instance, among patients with lung cancer, the prevalence of major depressive disorder ranges from 5 % to 13 %, and up to 44 % may experience depressive symptoms—rates that are consistently higher than those seen in other cancer types (Aaronson et al., 1993; Calderon, 2020; Calderon et al., 2020; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). More severe and persistent depressive symptoms in cancer patients have been linked to poorer treatment adherence, prolonged hospital stays, reduced quality of life (QoL), increased physical discomfort, and even a higher desire for hastened death (Calderon, 2022; Calderon et al., 2022; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009). Notably, depression diagnosed at the time of cancer diagnosis has also been associated with increased mortality, especially in lung cancer (Dunn et al., 2011; Hinz et al., 2019; Linden et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2021). In response to these findings, oncologic societies have developed clinical guidelines recommending routine psychological assessment throughout the cancer care trajectory, and the implementation of integrated, collaborative approaches to depression care. These interventions have shown positive effects on QoL and functioning in cancer patients (Ferrari et al., 2019; Goldzweig et al., 2009; Vodermaier et al., 2011). Although treating depression is already recognized as essential for improving well-being, evidence suggests that it could also impact survival outcomes—thus raising the possibility that mental health care may be as important as other adjuvant oncologic therapies (Begovic-Juhant & Chmielewski, 2012; Broeckel et al., 2000).

Despite the growing recognition of the clinical significance of psychological distress, further research is needed to elucidate the evolution of depression during cancer treatment and its interactions with sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment-related variables. In particular, it remains unclear whether these factors differ among patients who never experience depression, those with transient depressive symptoms, and those with persistent depression.

This study aims to assess depressive status and its associations with sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables, as well as with treatment-related toxicity and QoL, in patients with localized resected cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy. We also sought to identify independent predictors of depression through multivariate analyses and to examine longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms.

MethodsDesign and proceduresNEOcoping is a multicenter, prospective, observational, and longitudinal study promoted by the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM). Fifteen medical oncology departments from Spanish hospitals participated in the study. The inclusion criteria consisted of patients aged 18 years or older with completely resected, non-metastatic cancer treated with curative intent, for whom adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended according to clinical practice guidelines. Exclusion criteria included patients with cognitive impairment or any condition that, per the medical oncologist's assessment, would hinder their ability to understand the study or complete the questionnaires, as well as those who had received prior neoadjuvant anticancer therapy or who presented any condition contraindicating adjuvant systemic treatment. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards/ethics committees of all participating institutions.

Eligible patients were consecutively enrolled after they were fully informed about the study, provided written informed consent, and agreed to participate. Patient enrollment occurred during the first visit to the medical oncology department for adjuvant chemotherapy—approximately one month post-surgery—which served as the baseline time point (T1). At T1, a comprehensive baseline history was obtained, a physical examination was performed, and patients were provided with questionnaires to complete at home, which they returned at their subsequent visit. Each questionnaire included detailed written instructions and clearly stated that participation was voluntary and that responses would remain confidential. At six months follow-up—coinciding with the completion of adjuvant systemic treatment (T2)—a second questionnaire was administered to reassess both clinical and psychological parameters.

MeasuresSociodemographic and clinical data were collected using a standardized self-report form and verified through patient interviews and medical records by the attending oncologist at all participating hospitals.

Participants were categorized into four groups based on depressive status assessed at two time points: baseline (T1) and six months later, at the end of adjuvant therapy (T2). The groups were defined as follows: "never" (patients without depression at both T1 and T2), "new-onset depression" (patients without depression at T1 who developed depression at T2), "remission" (patients with depression at T1 but not at T2), and "persistent" (patients with depression at both T1 and T2).

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18) at both T1 and T2. Additionally, both patients and oncologists estimated the risk of recurrence in the absence of chemotherapy and the risk of toxicity with chemotherapy at T1. At T2, the oncologist evaluated the maximum toxicity experienced during adjuvant treatment, and patients completed the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30).

The BSI-18 is an 18-item self-report questionnaire that evaluates mental well-being over the past week and has been validated in Spanish for use in cancer patients (Calderon et al., 2020). It measures three domains: depression, anxiety, and somatization. In the present study, only the depression subscale was analyzed. This subscale comprises six items covering dysphoric mood, anhedonia, and self-deprecation, with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all” to 4 = “extremely”). Raw scores are converted to T-scores based on gender-specific normative data, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptomatology (range 0–24). Following Derogatis’ criteria, patients with T-scores between 63 and 66 were classified as having possible depression, and those with T-scores ≥67 as probable depression (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). In our sample, the subscale demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75), in line with previous validation studies of the Spanish version (α = 0.88) (Calderon, 2020).

The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a 30-item questionnaire comprising five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea/vomiting), a global health status/ QoL scale, and several single items assessing additional symptoms commonly reported by cancer patients (e.g., dyspnea, loss of appetite, insomnia, constipation, and diarrhea), as well as the financial impact of the disease (Aaronson et al., 1993). This instrument is widely used and validated in Spanish cancer patients (Calderon et al., 2022). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 ("not at all") to 4 ("a lot"), and scores are then converted to a 0–100 scale, where higher scores indicate better functioning for the functional scales and a greater symptom burden for the symptom scales. The Cronbach's alpha for Spanish cancer patients was 0.86 (Calderon, 2022).

Both patients' and oncologists' perceptions of the risk of relapse without adjuvant chemotherapy and the risk of toxicity with adjuvant chemotherapy were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (low, intermediate, high, very high) to capture their definitive impressions.

Both patients' and oncologists' perceptions of the risk of relapse without adjuvant chemotherapy and the risk of toxicity with adjuvant chemotherapy were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (low, intermediate, high, very high) to capture their definitive impressions.

At the conclusion of adjuvant treatment (T2), maximum chemotherapy-related toxicities—including gastrointestinal, hematological, neurological, and skin toxicities, as well as asthenia—were recorded. Maximum toxicity was defined as the highest grade of any toxicity experienced by each patient during adjuvant chemotherapy, classified according to CTCAE v4.0 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2009). Additionally, early discontinuation of adjuvant treatment and the reasons for withdrawal were documented as a categorical variable with five levels: completed therapy, toxicity, intercurrent problems, patient's desire, and others.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were employed to summarize sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at baseline (T1) by depression status. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the BSI-18 at baseline and after six months of follow-up (T2), with participants classified into four groups: "never" (no symptoms at T1 or T2), "new-onset depression" (symptoms absent at T1 but present at T2), "remission" (symptoms present at T1 but absent at T2), and "persistent depression" (symptoms present at both T1 and T2). Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Differences between groups were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. For pairwise comparisons of means, Student’s t-test assuming equal variances was applied. To examine the relationship between depressive status and treatment toxicity, ANOVA was used to compare mean toxicity scores across depression groups.

Similarly, QoL scores from the EORTC QLQ-C30 were analyzed according to depressive status using ANOVA.

In addition to these categorical analyses, continuous BSI-18 depression T-scores were modeled using multivariate approaches. First, a multiple linear regression was conducted with depression at T2 as the dependent variable, adjusting for baseline depression (T1) and sociodemographic/clinical covariates (age, sex, marital status, tumor site, treatment modality, and ECOG). Second, a multiple regression was performed on change in depression (Δ = T2–T1) with the same covariates. Finally, a sensitivity analysis was carried out using ANCOVA, with depression at T2 as the dependent variable and baseline depression as a covariate, controlling for the same predictors. Full results of these multivariate models are provided in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, and 3. Additionally, logistic regression models were conducted to evaluate the odds of being classified as persistently versus never depressed, based on sociodemographic and clinical predictors (age, sex, marital status, tumor site, treatment modality, and ECOG).

Survival analysis was not performed given the curative intent and the short-term follow-up period (six months). A drop-out analysis was conducted to confirm comparability between patients who completed the study and those who did not, with no significant differences observed. All statistical tests were two-sided, with significance set at p < .05. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

ResultsPatient’s characteristicsDuring the study period, 1003 potential participants were identified, of whom 927 met the eligibility criteria. Seventy-six participants were excluded (20 did not meet the inclusion criteria, 32 met an exclusion criterion, and 24 had incomplete data). Among the 927 eligible participants, 68 % (n = 628) completed the study by providing both baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) questionnaires, with the T2 assessment administered at the conclusion of adjuvant antitumor treatment—approximately six months after its initiation. No significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics between patients who completed the questionnaires (n = 628) and those who did not (32 %, n = 309).

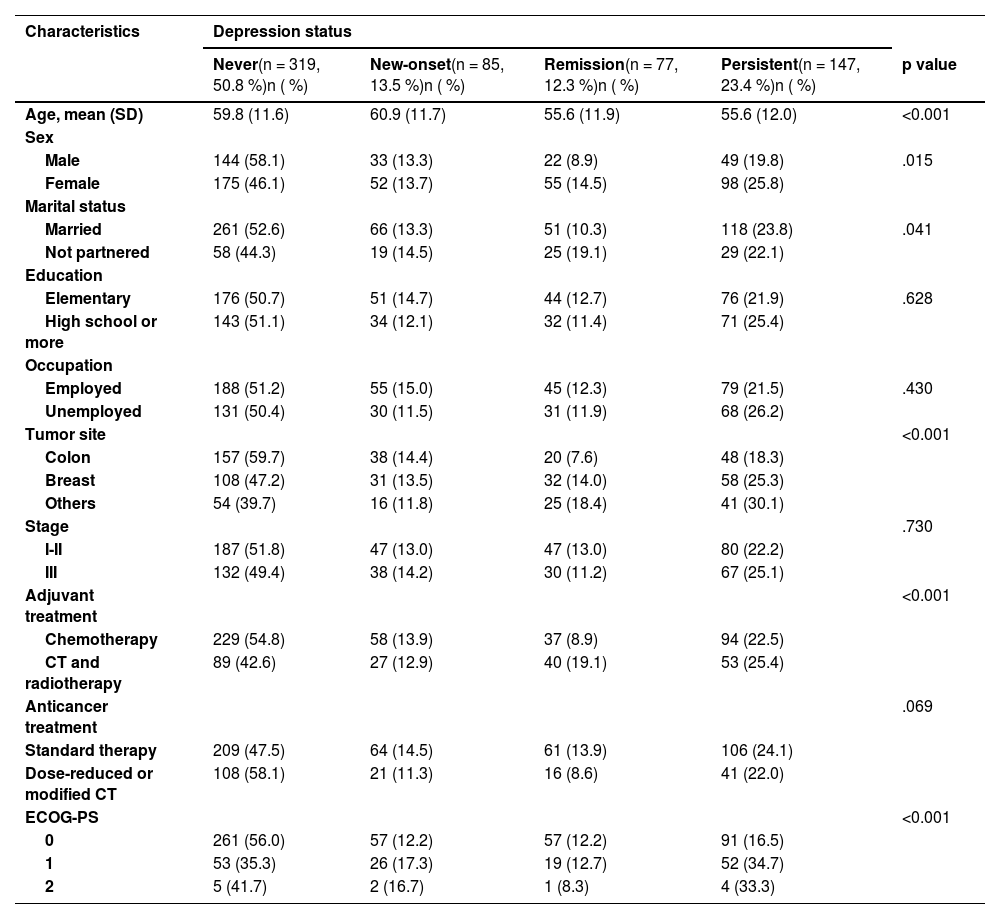

Table 1 displays the distribution of participants according to depressive status. Specifically, 50.8 % (n = 319) of patients were classified as having “no depressive symptoms” (never) at both T1 and T2. Additionally, 13.5 % (n = 85) were classified as having “new-onset depression” (symptoms absent at T1 but present at T2), 12.3 % (n = 77) as “remission” (symptoms present at T1 but absent at T2), and 23.4 % (n = 147) as “persistent” (symptoms present at both T1 and T2).

Baseline participant characteristics by depression status.

Abbreviations: N = number; SD = standard deviation; CT = chemotherapy; ECOG-PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

Regarding demographic and clinical characteristics, several significant differences were observed according to depressive status. The mean age of patients ranged from 55.6 to 60.9 years, with patients classified as having “no symptoms” and those with “new-onset depression” being older than those in remission or with persistent depression (p = .001). A significant sex difference was noted, with women exhibiting a higher prevalence of persistent depressive symptoms than men (25.8 % vs. 19.8 %; χ² = 10.452; p = .015). Married individuals were more likely to be classified as having “no symptoms” compared to unmarried individuals (52.6 % vs. 44.3 %; χ² = 8.272; p = .041). Differences were also observed by tumor type, with colon cancer patients exhibiting fewer depressive symptoms than breast cancer patients (59.7 % vs. 47.2 %; χ² = 23.809; p = .001). Patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy alone had a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to those receiving combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (54.8 % vs. 42.6 %; χ² = 16.680; p = .001). Furthermore, patients with better performance status (ECOG 0) demonstrated fewer depressive symptoms compared to those with ECOG ≥ 1 (56.0 % vs. 41.7 %; χ² = 23.817; p = .001). No significant differences were observed with respect to educational level, occupation, tumor stage, or type of anticancer treatment.

In multivariate analyses, baseline depression and ECOG performance status were the only independent predictors of depression at T2, jointly explaining about one third of the variance (adjusted R² = 0.318; see Supplementary Table 1). When examining changes in depression scores (Δ = T2–T1), the model accounted for only a small proportion of the variance (adjusted R² = 0.016; Supplementary Table 2), with age emerging as the only significant predictor and ECOG showing a non-significant trend. ANCOVA confirmed these findings, indicating that baseline depression and functional status remained the only independent predictors of depression at T2 after adjustment (Supplementary Table 3).

To further explore the classification of depression, logistic regression models were conducted comparing persistent versus never depressed patients. The model was statistically significant (χ² = 49.7, p < .001), with acceptable goodness of fit (Hosmer–Lemeshow p = .41) and modest explanatory power (Nagelkerke R² = 0.141). Younger age (OR = 0.97, 95 % CI: 0.95–0.99), female sex (OR = 1.76, 95 % CI: 1.03–3.00), breast cancer compared with colon or other tumor sites (OR ≈ 0.5), and poorer ECOG performance status were associated with higher odds of persistent depression. Marital status and treatment scheme were not significant predictors. Full results are presented in Supplementary Table 4. (Fig. 1)

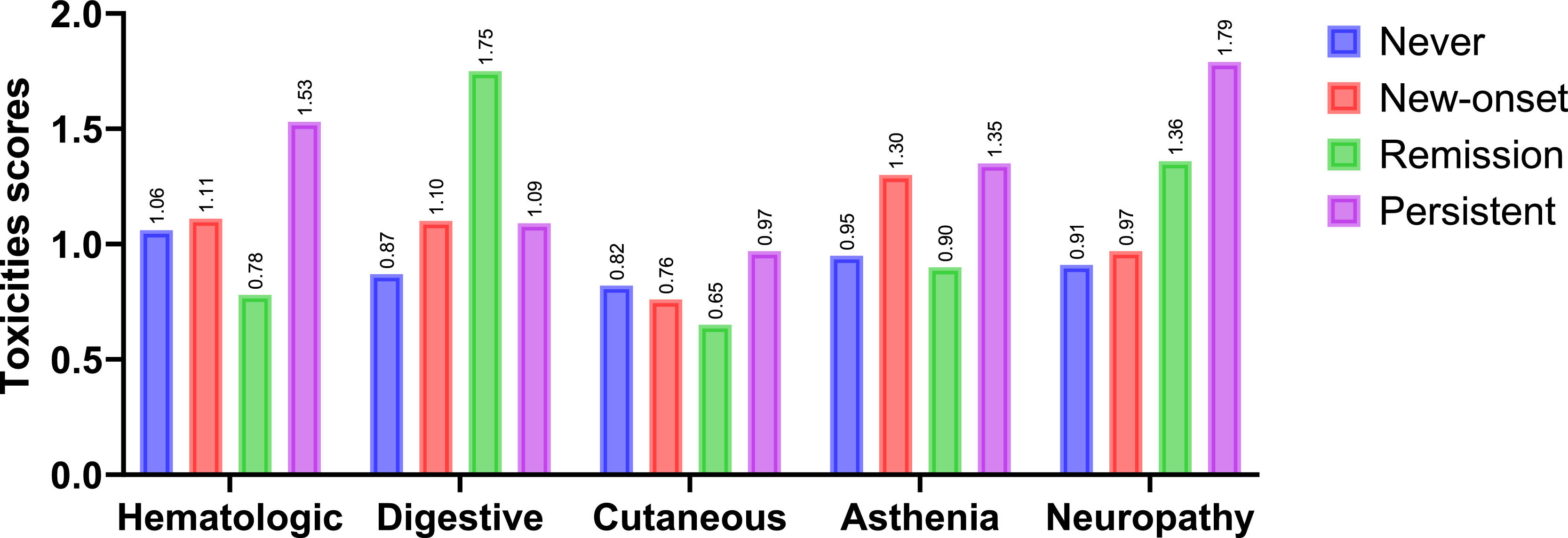

Depressive status and toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapyPatients with persistent depression exhibited the highest levels of toxicity across most domains. They showed greater hematologic toxicity compared with all other groups (M = 1.53 vs. 1.06–1.11; p < .001), higher digestive toxicity compared with the remission group (M = 1.09 vs. 0.75; p = .027), and increased neuropathic toxicity relative to the “never” and new-onset groups (M = 1.79 vs. 0.91–0.97; p < .01). Regarding asthenia, both the persistent and new-onset groups reported significantly higher levels than the “never” and remission groups (M = 1.30–1.35 vs. 0.90–0.95; p < .001). Cutaneous toxicity differences were smaller, reaching significance only between the remission and persistent groups (M = 0.65 vs. 0.97; p = .034). Overall, these findings highlight that persistent depression is consistently associated with a higher toxicity burden and a heightened perception of treatment risk. Conversely, patients in remission displayed intermediate levels across several domains, suggesting that improvements in mood symptoms may translate into better treatment tolerance and more balanced risk perceptions. These results are illustrated in Fig. 2, with full descriptive statistics and post hoc comparisons reported in Supplementary Table 5.

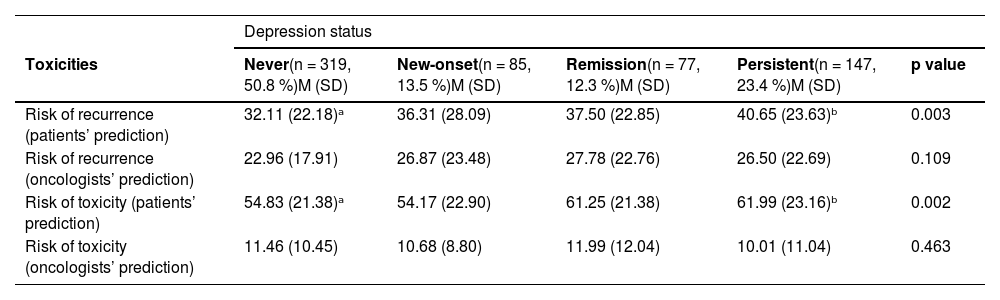

Depressive status and perception risk of recurrence and toxicityIn terms of risk perception, patients with persistent depression anticipated a greater risk of recurrence without adjuvant chemotherapy (M = 40.6 vs. 32.1–37.5; p = .003) and higher risk of treatment toxicity (M = 62.0 vs. 54.1–61.2; p = .002) compared with the other groups. In contrast, oncologists’ assessments of recurrence or toxicity risk did not significantly differ across depression categories (p = .109 and p = .463, respectively), see Table 2.

Perceived risk of recurrence and toxicity according to depression status.

Note. Values represent means (M) and standard deviations (SD). Superscripts denote significant post hoc differences based on Bonferroni correction (p < .05). Different superscripts within a row indicate significant between-group differences. Abbreviations: M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

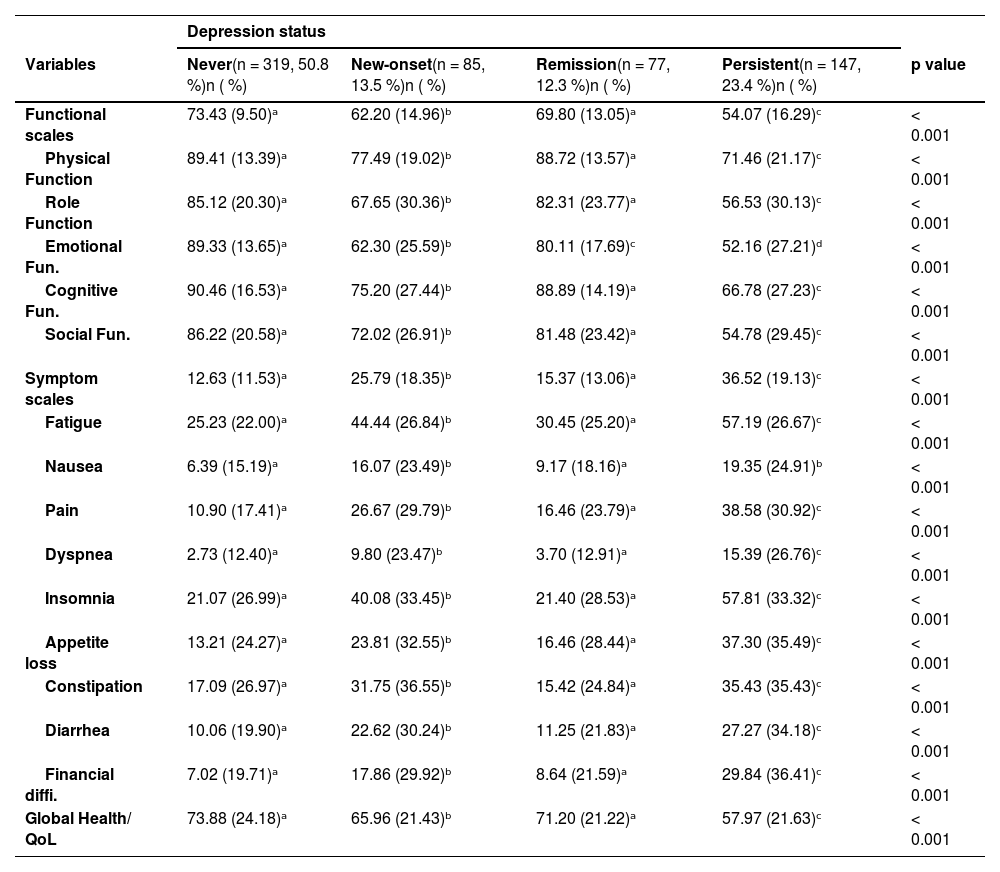

Patients with persistent depressive symptoms exhibited significantly poorer outcomes across all QoL domains compared to those without depressive symptoms or those in remission. Specifically, they showed markedly lower scores in emotional (M = 52.1, SD = 27.2 vs. 89.1, SD = 13.6, p < .001), physical (71.4, SD = 21.1 vs. 89.3, SD = 13.4, p < .001), and role function (56.5, SD = 30.1 vs. 84.8, SD = 13.4, p < .001), as well as in cognitive (66.7, SD = 27.2 vs. 90.3, SD = 16.6, p < .001) and social functioning (54.7, SD = 29.4 vs. 85.9, SD = 20.6, p < .001). On the symptom scales, patients with persistent depression reported considerably higher fatigue (57.1 vs. 25.2), pain (38.5 vs. 11.0), dyspnea (15.3 vs. 2.7), and insomnia (57.8 vs. 20.3) compared with those never depressed (all p < .001). They also showed more appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties (all p < .001).

Importantly, patients in the new-onset group also experienced worse functioning and higher symptom burden compared to never-depressed patients, though generally at intermediate levels. By contrast, patients in remission achieved QoL scores closer to the never-depressed group, suggesting that improvement in mood symptoms may translate into better treatment tolerance and well-being.

Overall, global health and QoL were significantly worse in the persistent group (M = 57.9, SD = 21.6) compared to never depressed patients (M = 73.4, SD = 24.1, p < .001). Table 3 summarizes these findings, highlighting a consistent gradient in outcomes: the best QoL in never depressed, intermediate scores in remission, worse in new-onset, and poorest in persistent depression.

Quality of life at 6 months by depression status.

Note. Values are means (M) and standard deviations (SD). Superscripts denote significant post hoc differences based on Bonferroni correction (p < .05). Different superscripts within a row indicate significant between-group differences. Abbreviations: QoL = quality of life; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

In this study, we evaluated depressive symptomatology in patients with early-stage resected cancer at the onset of adjuvant systemic treatment and its evolution at the end of treatment (six months later). We examined the association between depressive status and various demographic, clinical, and psychological factors, as well as its impact on quality of life (QoL). At baseline (T1), approximately 12.3 % of patients exhibited depressive symptoms that resolved by follow-up (T2), whereas 23.4 % showed persistent symptoms at both time points. In addition, 13.5 % of patients developed depressive symptoms during follow-up despite being asymptomatic at baseline. These prevalence rates are comparable to those reported in previous studies, although variability exists depending on the stage of cancer progression at which depression is assessed. For instance, a meta-analysis by Linden (2012), which included 1053 patients across various tumor types, reported a depression prevalence of 12.9 % (Linden et al., 2012), while other meta-analyses, such as Mitchell et al., have estimated rates exceeding 15 % (Mitchell et al., 2011). Few studies have documented the evolution of depressive symptomatology following adjuvant treatment. Nakamura’s study of 256 breast cancer patients reported baseline depressive symptom levels of up to 12 %, with an increase to 26 % over the course of chemotherapy (Nakamura et al., 2021). Similarly, Dunn et al. (Dunn et al., 2011) identified four distinct trajectories of depression in 86 breast cancer patients, with the most common pattern (46 %) reflecting stable depression scores throughout treatment, and smaller subgroups (up to 15.8 %) experiencing an increase in depression after six months.

Several studies have explored the relationship between depressive symptomatology and demographic factors such as age, gender, and marital status. Our findings indicate that older patients are less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms at the end of adjuvant treatment, consistent with previous literature showing a higher prevalence of depression among younger cancer patients. In a study by Hinz involving 3785 patients with breast and digestive tumors, higher depression scores were observed in younger women compared to older cohorts and the general population (Hinz et al., 2019). Younger patients often face significant disruptions in both their professional and personal lives during cancer diagnosis and treatment, which may adversely affect multiple social roles, while older individuals may be better prepared both cognitively and emotionally (Linden et al., 2012). Regarding gender, we found that women exhibited higher baseline depression and greater persistence of symptoms during follow-up, corroborating previous research by Ferrari et al. (Ferrari et al., 2019) and Vodermaier et al. (Vodermaier et al., 2011), which demonstrated higher anxiety and depression scores in women. Factors such as changes in social roles, alterations in body image, and hormonal fluctuations associated with treatment may contribute to this increased vulnerability in female patients (Goldzweig et al., 2009).

When considering cancer type—focusing on the two most common cancers eligible for adjuvant treatment in our setting, breast and colorectal—we found that depressive symptoms were more frequent in breast cancer patients compared to those with colon cancer (59.7 % vs. 47.2 %). Given that breast cancer predominantly affects women, these findings align with previous studies reporting that adjuvant treatments can negatively impact body image and female sexuality, thereby elevating depression levels (Begovic-Juhant & Chmielewski, 2012), which in turn adversely affects QoL (Broeckel et al., 2000; Casavilca-Zambrano et al., 2020). Moreover, concerns related to childcare and family disruption further compound the emotional burden in these patients (Javan Biparva et al., 2023). Although literature has documented high rates of depression in cancers such as pancreatic and lung cancer due to factors like proinflammatory cytokine release, paraneoplastic syndromes, and overall symptomatic burden (Grassi et al., 2023; McFarland et al., 2021; Walker et, al), our study predominantly involved patients with localized tumors, hence these cancer types are underrepresented.

Importantly, our multivariate analyses confirmed that baseline depression was the strongest independent predictor of depressive symptoms at six months, while ECOG performance status also remained significant. Other sociodemographic and clinical variables lost significance once baseline symptoms were considered. Analyses of change in depression (Δ = T2–T1) explained only a modest proportion of variance, with age being the only significant predictor, and ANCOVA models confirmed the robustness of these findings. These results emphasize that both initial psychological symptoms and functional impairment are critical clinical markers of vulnerability and highlight the need for systematic screening and monitoring of depression throughout adjuvant therapy.

Complementing these analyses, logistic regression further showed that younger age, female sex, breast cancer compared with colon or other tumor sites, and poorer ECOG performance status were associated with higher odds of persistent depression versus never depressed patients. These findings reinforce the importance of considering demographic and functional vulnerability factors when identifying patients most at risk, and they provide clinically interpretable effect sizes that can guide screening and intervention strategies.

Patients with persistent depressive symptomatology at six months also experienced greater hematologic, digestive, and neuropathic toxicities compared to those without depressive symptoms or with new-onset depression. Prior research, such as that by DiMatteo, has demonstrated that depression may result in a threefold reduction in treatment adherence (MR DiMatteo et al., 2000), which may contribute to increased toxicity, poorer outcomes, and reduced survival rates (Arrieta et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2021). In our study, medical oncologists estimated a higher risk of recurrence for patients with baseline depression, possibly reflecting a perception of increased patient fragility, although toxicity risk predictions did not differ significantly based on depressive status.

Furthermore, patients with persistent depressive symptoms exhibited significant deterioration in multiple dimensions of QoL, including emotional, physical, cognitive and social functioning. Elevated levels of fatigue, pain, and insomnia in this group suggest that persistent depression not only compromises emotional well-being but also exacerbates physical symptom burden, complicating overall oncologic management. Importantly, patients with new-onset depression showed intermediate impairments, while those in remission achieved QoL scores closer to never-depressed patients, highlighting the dynamic nature of symptom trajectories.These findings are in line with the Ardebil study, which reported increased anxiety and depression, as well as worsening QoL, in breast cancer patients during treatment compared to those who had completed therapy (Ho et al., 2013). Similarly, Omran et al. (Omran & Mcmillan, 2018) identified depression as a predictive factor for QoL deterioration in a cohort of 341 cancer patients, primarily with breast, lung, and colon cancers. Collectively, these results underscore the importance of early detection and effective management of depression in patients undergoing curative treatment, as both preventing new-onset depression and supporting remission may improve QoL and overall treatment outcomes.

Study limitationsThis study has several limitations. First, depressive symptomatology was assessed using the BSI-18 without subsequent confirmatory clinical evaluation. Additionally, the management or treatment of depression, and its potential influence on its evolution, were not analyzed. Second, while the study evaluated depression at baseline and after six months (the end of adjuvant treatment), it does not provide insights into longer-term outcomes. Third, our findings cannot be generalized to patients with unresectable advanced cancers or to cancer types other than colon and breast cancer, which were the most common in this cohort and in clinical practice for adjuvant systemic treatment. Lastly, reliance on self-report instruments may have introduced biases, such as social desirability or recall errors.

Clinical implicationsThe results of this study have significant clinical implications for patients undergoing systemic antitumor treatment. Depressive symptoms are common and adversely affect treatment tolerance by increasing toxicity, particularly when these symptoms persist throughout treatment. Women, younger patients, individuals without a partner, breast cancer patients, and those with poor performance status represent particularly vulnerable groups. Early detection and targeted management of depression in these patients are crucial to improving both treatment adherence and overall QoL. These findings emphasize that systematic monitoring of depression trajectories is essential, since improvement in mood symptoms may translate into better QoL and treatment tolerance, while new-onset depression should be considered an early warning sign requiring timely intervention.

ConclusionsOur study demonstrates that nearly 50 % of patients with early-stage resected cancer undergoing adjuvant treatment exhibit baseline depressive symptoms, with almost one-quarter experiencing persistent depression throughout treatment. Depression was notably more prevalent among women, younger patients, those without a partner, and individuals with poorer performance status. Importantly, both baseline and persistent depression were associated with increased chemotherapy toxicity and significantly reduced quality of life. These findings underscore the critical need for routine psychological assessments and early, tailored interventions to support mental health in this high-risk population, ultimately aiming to improve treatment tolerance and overall outcomes.

FundingThis research did not receive any funding.

FundingThis study was supported by the FSEOM-Onvida Grant for Projects on Long-term Survivors and Quality of Life, awarded by the SEOM in 2015, and supported by PID2022–137317OB-100 from MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501,100,011,033/ and, by FEDER—A way to make Europe. The funding did not influence the study design, analysis, or interpretation of the data or the writing of the manuscript.

Data availability statementThe generated datasets are not publicly available due to privacy concerns. However, anonymized data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical approval statementThis study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. It is an observational, non-interventional study.

Patient consent statementInformed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Conflict of interest statementThe authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the scope of this project.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the patients, investigators, and medical oncology departments involved in the NEOcoping study. We also thank the SEOM Bioethics Group for their support in promoting this study, as well as Natalia Cateriano, Miguel Vaquero, and IRICOM S.A. for their invaluable assistance with the registry website.