Edited by: Assoc. Professor Joaquim Reis

(Piaget Institute, Lisbon, Portugal)

Dr. Luzia Travado

(Champalimaud Foundation, Lisboa, Portugal)

Dr. Michael Antoni

(University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, United States of America)

Last update: November 2025

More infoPatients with breast cancer (BC) are at risk for cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) due to BC-related stress and cancer treatment. Optimism and positive health behaviors may mitigate CRCI. This study examined relationships between optimism, health behaviors (sleep quality and physical activity) and CRCI in BC patients during the post-surgical period and whether optimism and health behaviors interacted in this relationship.

MethodsWomen with recently diagnosed BC enrolled in a stress management trial following BC surgery. At baseline, participants completed questionnaires that measured CRCI, optimism, sleep quality, and physical activity.

Results79 patients were enrolled (M = 61 years; range=50–85). Multiple regression models controlling for patient age, stage, surgery type, body mass index, and comorbidities revealed that optimism was associated with fewer perceived cognitive impairments (β=0.32, p=.01) and greater perceived cognitive abilities (β=0.38, p=.001). Poorer sleep quality was associated with poorer perceived cognitive abilities (β =-0.37, p=.01) and greater impact of cognitive impairments on quality of life (β=-0.39, p=.01). Moderation models revealed an interaction between optimism and sleep quality on perceived cognitive impairments (β=2.06, p=.02), such that among those low in optimism, poorer sleep quality was associated with greater perceived cognitive impairments (b=-2.42, p=.01) but not among those with high optimism (p=.46). No other models were statistically significant.

ConclusionsResults suggest that optimism and sleep quality may be associated with better cognitive function in BC patients in the post-surgical period. Interventions that improve optimistic expectancies and sleep quality may help to mitigate CRCI in mid-to-older BC patients initiating treatment.

Aging is characterized by progressive molecular, cellular, and intracellular changes, which results in molecular and cellular damage over time, and leads to impaired function, heightened risk of age-related diseases, and an elevated vulnerability to death (López-Otín et al., 2013). Previous work has found that biological aging processes are accelerated in patients with cancer due to the underlying mechanisms of cancer treatment (Benitez-Buelga et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2016; Demaria et al., 2017). However, the current aging literature suggests psychosocial stressors can also accelerate biological aging processes (Hansen et al., 2024; Polsky et al., 2022; Rentscher et al., 2022, 2019). Patients with breast cancer (BC) experience significant levels of distress due to the impact of the diagnosis (Braga Mendonça et al., 2022; Lacourt et al., 2023), fear of unknowns in treatment course and outcomes (Braga Mendonça et al., 2022; Lacourt et al., 2023), loneliness (Hilakivi-Clarke & de Oliveira Andrade, 2023), and financial burdens (Lee et al., 2023). Distress in patients with BC has been found to be the most elevated prior to initiation of a new treatment due to uncertainty surrounding side effects, impacts to daily life, and outcomes of the treatment (Braga Mendonça et al., 2022; İzci et al., 2020; Lacourt et al., 2023). Additionally, there is substantial distress in BC that arises from surgery due to changes in body image perception and difficulties in activities of daily living (Reich et al., 2008). Therefore, those with BC in the post-surgical period waiting to start adjuvant treatments may be at particular risk for stress-induced accelerated biological aging.

A hallmark of biological aging, cellular senescence, results from excessive cellular and DNA damage caused by both stress and cancer therapy (López-Otín et al., 2023; Polsky et al., 2022). Cellular senescence stimulates the release of the pro-inflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) that causes systemic inflammation (Coppé et al., 2010). Chronic inflammation has been found to be a driver of cognitive decline among patients with BC (Carroll et al., 2023; Mandelblatt et al., 2023). Cancer-related cognitive impairment (CRCI) is a commonly reported symptom among patients with BC, and current work suggests that older BC survivors and patients often have both subjective and objective cognitive impairment (Boscher et al., 2020; Crouch et al., 2022; Lange et al., 2019; Mandelblatt et al., 2018), which is related to significant declines in quality of life (Crouch et al., 2022; Maeir et al., 2023). CRCI has been most associated with adjuvant therapies like chemotherapy and radiation; however, some studies suggest that those in the post-surgical period, prior to the receipt of adjuvant systemic therapies, also experience cognitive impairment (Kaiser et al., 2019; Reid-Arndt & Cox, 2012). Psychosocial mechanisms that impact CRCI in the post-surgical period remain largely unknown. There is some evidence to suggest that lower distress levels may protect against CRCI. One study found that greater distress tolerance was associated with greater perceived cognitive abilities and less perceived cognitive impairments in patients with BC during the post-surgical period (Saez-Clarke et al., 2025). Resiliency characteristics and adaptive coping through engagement in positive behaviors may be potential mechanisms that buffer the impacts of stress-induced aging on CRCI.

One such resiliency characteristic that may act as a buffer on stress-induced aging is dispositional optimism, which is the tendency to expect positive outcomes in the future. Optimism has often been associated with healthy aging and physical health (Rasmussen et al., 2009; Scheier & Carver, 2018). Greater optimism was found to reduce all-cause mortality (Jacobs et al., 2021), improve healthy aging (James et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019) and was associated with reduced risk of cognitive impairment in general population studies (Gawronski et al., 2016; Sachs et al., 2023). Older adults with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia were found to have lower optimism compared to healthy controls (Dos Santos et al., 2018). In a study of mixed cancer patients, optimism was associated with less subjective cognitive impairment (Taber et al., 2016); however, little is known about how optimism relates to CRCI in middle-to-older aged patients with BC specifically. Moreover, those with greater optimism have been found to have better sleep quality (Monroe et al., 2024) and physical functioning (Koga et al., 2024), which may suggest that high optimism may interact with positive health behaviors in facilitating cognitive functioning.

Adaptive coping strategies like engaging in more positive health behaviors, such as sleep or physical activity, may also mitigate CRCI. Greater physical activity in older adults generally has been widely associated with better cognition (Northey et al., 2018); however, the literature is mixed on the impact of physical activity on CRCI (Campbell et al., 2019, 2020). Several studies have found that higher levels of physical activity improve perceived cognitive function, but not objectively measured cognitive function in patients with BC (Artese et al., 2024; Hartman et al., 2024; Koevoets et al., 2022), and other studies have found that increased physical activity was associated with objectively measured cognitive function (Koevoets et al., 2024; Tometich et al., 2023). One study found that replacing sedentary time with moderate to vigorous physical activity was associated with better performance on neurocognitive tests suggesting that lower engagement with physical activity may contribute to CRCI (Ehlers et al., 2018). However, little is known about the impact of physical activity on CRCI in older BC patients during the post-surgical period.

Additionally, poor sleep is often reported by patients with BC, and sleep difficulties and poor sleep quality have been associated with poor perceived cognitive impairment in BC survivors (Boscher et al., 2020; Henneghan, 2016). One study found that BC survivors with mild, moderate, and severe insomnia all reported greater perceived cognitive impairment compared to those without insomnia (Liou et al., 2019). Moreover, cancer survivors had a reduction in insomnia severity and significant improvement in CRCI when given Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (Garland et al., 2024), which further suggests that improvements in sleep paralleled improved cognitive function in cancer survivors. However, little is known about the impact of sleep on CRCI in middle-to-older patients with BC during the post-surgical period.

The present study tested whether health behaviors (sleep quality and physical activity) were related to CRCI in middle-to-older aged patients with BC during the post-surgical period. Additional aims assessed whether optimism was associated with less CRCI and if optimism mitigated the impact of poorer sleep quality and low physical activity on CRCI in the post-surgical period. We hypothesized that poorer sleep quality and less physical activity would be associated with greater levels of CRCI. We also hypothesized that higher levels of optimism would be associated with less CRCI, and that optimism would buffer the effects of these negative health behaviors on CRCI. All analyses controlled for relevant demographic and medical characteristics.

MethodsParticipants and proceduresParticipants were enrolled from academic medical centers in South Florida as part of a larger stress management intervention randomized controlled trial (NCT03955991), which was approved by an Institutional Review Board (6/7/2016; IRB#: 20160525), and all procedures were performed in compliance with the Institutional Review Board. Women were eligible for the study if they were 50 years of age or older, had newly diagnosed stage 0-III BC, completed surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy) at least 2 weeks prior to completing baseline measures but had not received neoadjuvant therapy or initiated adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation, had a life expectancy of >12 months, and had a score of >14 on the Impact of Event Scale Intrusion subscale (Weiss, 2007) for cancer-specific distress or self-reported moderate distress over the past week (a score of 4 or greater out of 10). Women were excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of cancer (with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer) within the past 2 years, a diagnosis of a major mental disorder (i.e. schizophrenia and/or bipolar disorder) or active (in the past 12 months) major depressive disorder, panic disorder, PTSD diagnosis, or a history of suicidal ideation or attempts, a co-morbid medical condition with known effects on the immune system (e.g. HIV infection or autoimmune disease), prior neoadjuvant therapy, current medications that act as direct immunomodulators, significant cognitive impairment (<31 on the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status), or could not speak and read English. After providing informed consent, participants completed self-report measures at baseline. In total, 109 women were enrolled to the larger intervention trial, and 79 women completed baseline cognitive function self-report measures and at least one other self-report measure assessed in the present study.

MeasuresCRCI. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Cognitive Function (FACT-Cog) was used to assess CRCI (Wagner et al., 2009). The FACT-Cog assesses cognitive function over the past week across 4 different subscales: Perceived Cognitive Impairments (18 items), Perceived Cognitive Abilities (7 items), Impact of Perceived Cognitive Impairments on Quality of Life (4 items), and Comments From Others (4 items). Perceived Cognitive Impairments, Impact of Perceived Cognitive Impairments on Quality, and Comments From Others were reversed scored in order for higher FACT-Cog scores to indicate better cognitive function. A cut-score of < 54 on Perceived Cognitive Impairments and ≤19.5 on the Perceived Cognitive Abilities has been previously published as potential indicators of CRCI (Dyk et al., 2020; Fardell et al., 2022). The FACT-Cog has demonstrated good psychometric properties in other cancer populations (Jacobs et al., 2007).

Optimism. The Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) was used to assess optimism. The 10-item scale measures general optimistic and pessimistic expectancies for the future. Scores on the LOT-R range from 0 to 24 with higher LOT-R scores indicating greater optimism. This scale has previously demonstrated adequate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) as well as predictive and discriminant validity (Scheier et al., 1994), and has been used previously in several studies to assess optimism in patients with BC (Calderon et al., 2019; Faye-Schjøll & Schou-Bredal, 2019).

Sleep Quality. The global score of the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality (Buysse et al., 1989). The 19-item scale measures sleep duration, disturbance, latency, daytime dysfunction from sleepiness, sleep efficiency, overall sleep quality, and sleep medication use over the past month. Scores range from 0 to 21 with higher PSQI scores indicating worse sleep quality, and a cut-score of 8 indicates clinical sleep disturbance in cancer populations (Carpenter & Andrykowski, 1998). The scale has previously demonstrated good validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.72) among patients with BC (Carpenter & Andrykowski, 1998).

Physical Activity. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) was used to assess physical activity (Washburn et al., 1993). The scale asks participants to recall the duration and frequency of leisure, household, and work-related activities over the past 7 days. Scores are calculated by multiplying the amount of time spent on each activity (hours/week) with empirically derived item weights that capture the intensity of each activity and then summing across all activities. Higher PASE scores indicate greater physical activity. The PASE has been found previously to have excellent test-retest reliability and good content validity in patients with cancer (Liu et al., 2011). To further qualitatively understand the intensity of activity in which participants engaged, items on the PASE were sorted by intensity level based on the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines, and the amount of time spent on each activity was summed into light activity (METs < 3), moderate activity (3 ≤ METs < 6) and vigorous activity (METs ≥ 6) subcategories (Piercy et al., 2018). Intensity of each item was determined using the Compendium of Physical Activities (Herrmann et al., 2024).

Covariates. Several variables that might affect aging and cognition were evaluated as covariates in the main analysis based on previous research (Diaz et al., 2021; McDeed et al., 2024), which included age, cancer stage, surgery type, body mass index (BMI), and number of comorbidities. We extracted age, cancer stage, surgery type, and BMI from the participant’s electronic medical record. The number of comorbidities was collected using self-report items from the Charlson Comorbidity Index (Charlson et al., 1987).

Statistical analysisStatistics were conducted using R programing language. Participants were excluded only from analyses from which they were missing data. To analyze the main effects of optimism and health behaviors on CRCI, we conducted separate linear regression models for each predictor and outcome that controlled for age, stage, surgery type, BMI, and number of comorbidities. To examine whether optimism buffers the effects of reduced engagement with health behaviors, we conducted moderation models with the same covariates. For significant interactions, subsequent simple slopes analyses were conducted to further probe the nature of the interaction using Mean-1SD and Mean+1SD groupings. Regression and moderation models were run using the “Psych” package (Revelle, 2024), and standardized β coefficients were calculated using the “lm.beta” package (Behrendt, 2023). Simple slopes analyses and graphing were conducted using the “interactions” package (Long, 2024).

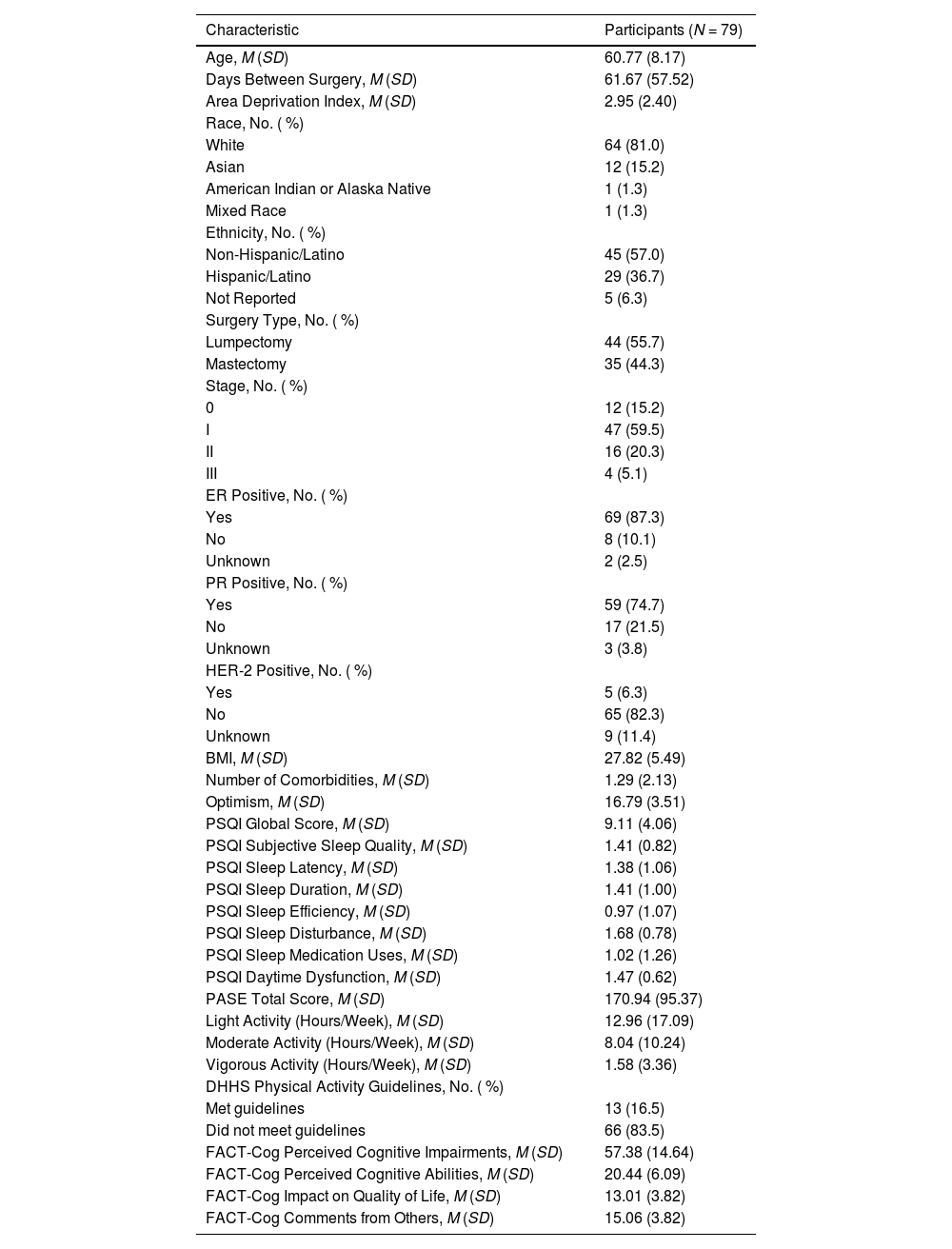

ResultsSample characteristicsDemographic, medical, and study variable descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1. Participants had a mean age of 60.77 years (SD = 8.17) and were on average 61.67 days (SD = 67.52) post-surgery at the time of enrollment. Participants were also, on average, 72.12 days (SD = 58.76) post-surgery at time of questionnaire administration. The majority of patients were White (81.0 %) and 36.7 % of the sample identified as Hispanic/Latino. About half of participants had stage I BC (59.5 %) and underwent a lumpectomy (55.7 %) as their primary cancer treatment. The majority of participants had ER (87.3 %) and/or PR positive cancer (74.7 %).

Characteristics of the sample.

Note. Demographics were assessed by self-report and confirmed by electronic medical record review. ER = Estrogen Receptor, PR = Progesterone Receptor, HER-2 = Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2, BMI = Body Mass Index. DHHS = Department of Health and Human Services.

The mean optimism score of the sample was 16.79 (SD = 3.51), which is in the mid-range of potential optimism scores (Range = 0 – 24). The mean sleep quality score was 9.11 (SD = 4.06), which is a full point above the cut-off score for sleep disturbance in patients with cancer on the measure (Carpenter & Andrykowski, 1998) and well above the cut-off of 5 for the general population (Buysse et al., 1989). In total, 36 (45.6 %) patients had sleep quality scores that were above the clinical cut-off score of 8 for sleep disturbance in persons with cancer. The mean PASE score was 170.94 (SD = 95.37), which is significantly above the activity levels of previous research that found an average score of 125.2 (SD = 79.9) in a healthy adult sample (Washburn & Ficker, 1999) and a median score of 87 (IQR = 52–162) in a sample of patients with different cancer types (Liu et al., 2011). Most participants reported high amounts of light activity (M = 12.96 h/week, SD = 17.09) as well as modest amounts of moderate activity (M = 8.04 h/week, SD = 10.24) and vigorous activity (M = 1.58 h/week, SD = 3.36). However, only 13 (16.5 %) participants met the Department of Health and Human Service guidelines for physical activity in adults and older adults (Greater than 2.5 h of moderate activity or between 1.25 h and 2.5 h of vigorous activity per week and muscle-strengthening activities at least 2 days a week) (Piercy et al., 2018). This was due in large part to most participants not endorsing muscle-strengthening activities rather than participants not meeting other criteria as 62 (78.5 %) patients reported engaging in moderate or vigorous activity for the recommended amount of time. The mean Perceived Cognitive Impairments score was 57.38 (SD = 14.64), which was just above the suggested cut-point for cognitive impairment of 54 (Dyk et al., 2020). In total, 21 (26.6 %) participants had Perceived Cognitive Impairment scores that fell below the cut-point indicating cognitive impairment. The mean Perceived Cognitive Abilities score was 20.77 (SD = 60.9), which was also just above the suggested cut-point for cognitive impairment of 19.5 (Fardell et al., 2022). Thirty-two (40.5 %) participants had Perceived Cognitive Abilities scores that fell below the cut-off, suggesting cognitive impairment. Both the mean scores for Impact of Perceived Cognitive Impairments on Quality of Life (M = 13.01, SD = 3.82) and Comments From Others (M = 15.06, SD =3.82) were at the high end of the subscales, suggesting less impairment in the sample within these domains.

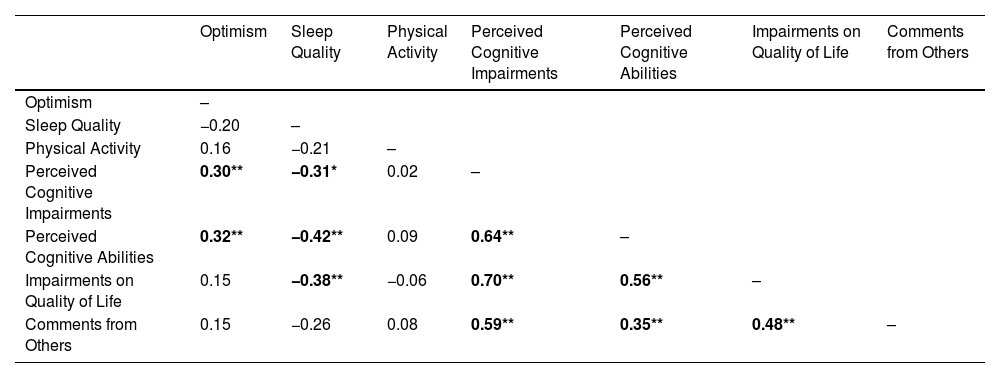

Bivariate correlationsAll bivariate correlations are reported in Table 2. Greater optimism was correlated with less perceived cognitive impairments (r = 0.30, p < .009) and greater perceived cognitive abilities (r = 0.32, p = .005). Poor sleep quality was correlated with greater perceived cognitive impairments (r = −0.31, p = .020), less perceived cognitive abilities (r = −0.38, p = .001) and greater impact of perceived cognitive impairments on quality of life (r = −0.42, p = .004). Physical activity was not significantly associated with any of the variables assessed. Additionally, the FACT-cog subscales were each strongly intercorrelated with the weakest correlation being between Perceived Cognitive Abilities and Comments From Others (r = 0.35, p < .001) and the strongest correlation being between Perceived Cognitive Impairments and Impact of Perceived Cognitive Impairments on Quality of Life (r = 0.70, p < .001).

Bivariate correlations of predictors and outcomes.

Note. Estimates are denoted as Pearson’s r. Bold denotes statistically significant results; * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01.

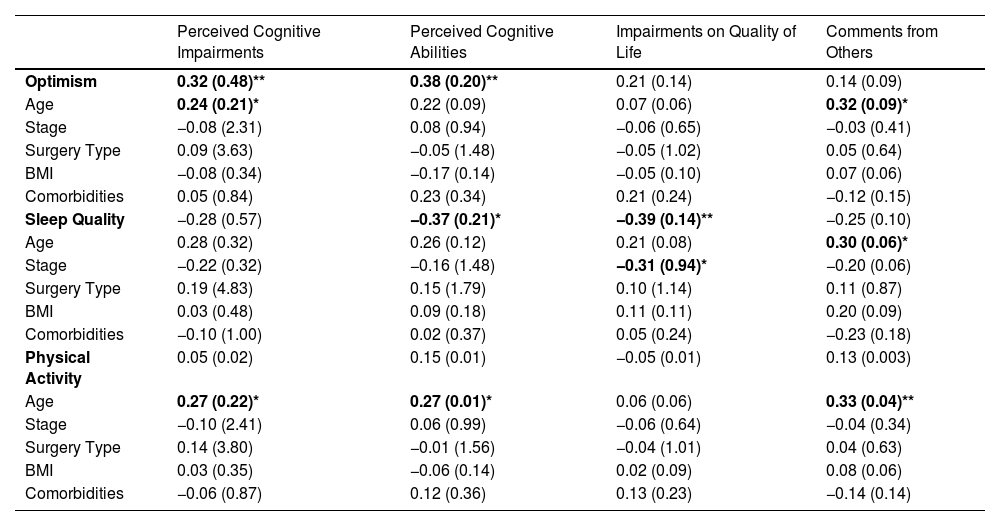

Full multiple regression models are presented in Table 3. Greater optimism was significantly associated with less perceived cognitive impairments (β = 0.32, SE = 0.48, p = .007) and greater perceived cognitive abilities (β = 0.38, SE = 0.20, p = .001). Poorer sleep quality was associated with poorer perceived cognitive abilities (β = −0.37, SE = 0.21, p = .011) and greater impact of perceived cognitive impairments on quality of life (β = −0.39, SE = 0.14, p = .006). A similar trend was observed for the other subscales, such that poorer sleep was associated with greater perceived cognitive impairments (β = −0.28, SE = 0.02, p = .056) and comments from others (β = −0.26, SE = 0.10, p = .078); however, neither achieved statistical significance. Physical activity was not significantly associated with any subscale of the FACT-Cog.

Multiple regression models with optimism, sleep quality, and physical activity predicting CRCI.

Note. Sample size differed for each model; optimism (n = 75), sleep quality (n = 54), and physical activity (n = 79). Results are noted as Standardized β (SE). Bold denotes statistically significant results; p < .05 = *, p < .01 = **.

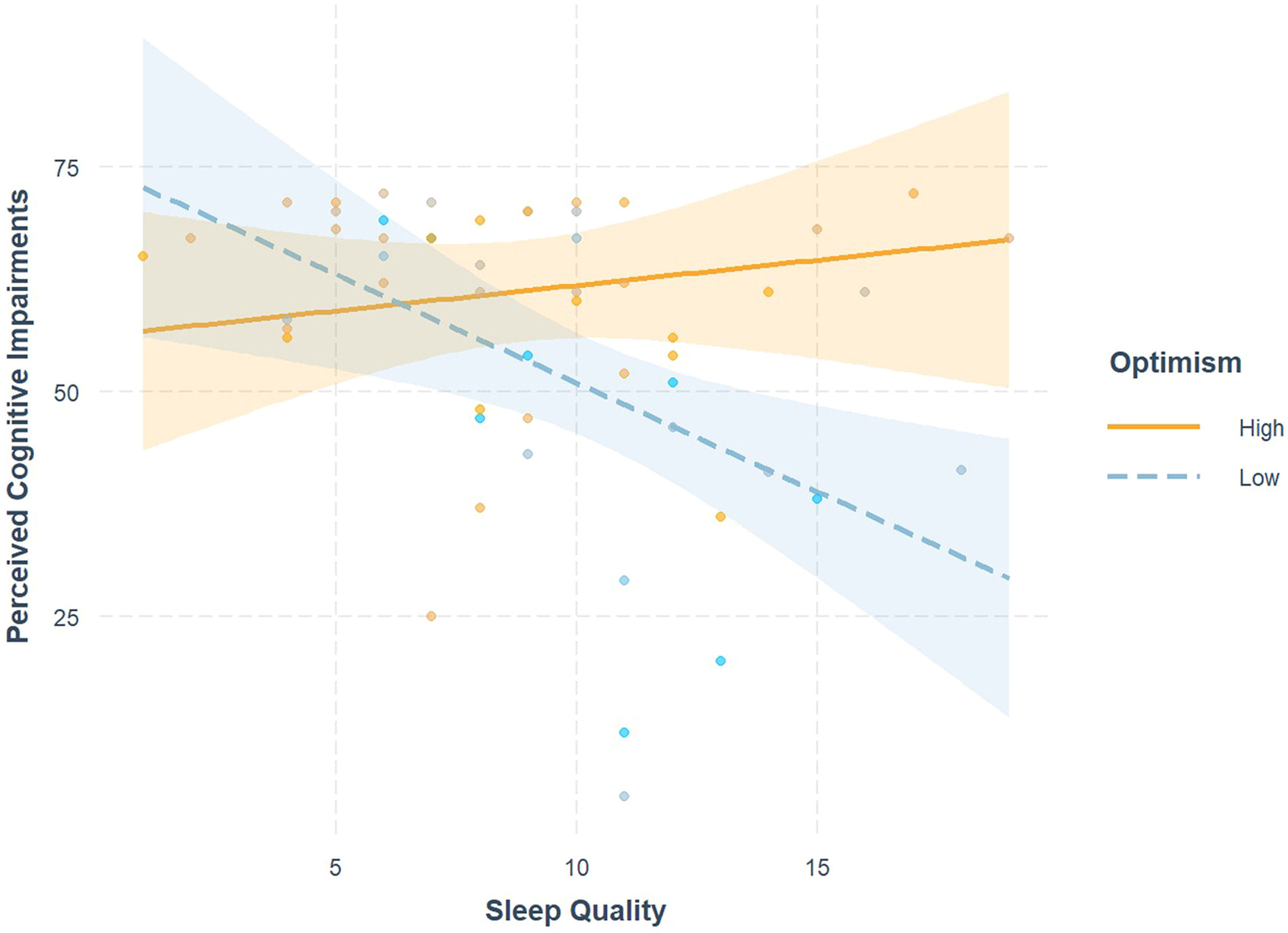

Full moderation results are provided in Table 4. An interaction existed between sleep quality and optimism on perceived cognitive impairments (β = 2.06, SE = 0.18, p = .015) and is visualized in Fig. 1. Simple slopes analysis revealed that when patients have lower state optimism (M-1SD = 13.73), poorer sleep quality is significantly associated with greater perceived cognitive impairments (b = −2.42, SE = 0.83, p = .006); however, when optimism is high (M + 1SD = 20.27), poorer sleep quality is not significantly associated with perceived cognitive impairments (b = 0.56, SE = 0.76, p = .462). No other moderation models were statistically significant.

Interaction effects of optimism and health behaviors on CRCI.

Note. Sample size differed for each predictor model; sleep quality (n = 54), and physical activity (n = 75). Results are noted as Standardized β (SE). Bold denotes statistically significant results; p < .05 = *, p < .01 = **.

Interaction effects of optimism and sleep quality on cognitive impairment. High sleep quality scores indicate poorer sleep quality, and lower perceived cognitive impairment scores indicate greater impairment. High vs. Low was quantified as +/−1 SD from mean optimism. Optimism significantly buffered the effect of poor sleep quality on perceived cognitive impairments, such that among those low in optimism the poor sleep quality was significantly associated with greater perceived cognitive impairments, but the association was not significant among those high in optimism.

Our findings indicate that middle-to-older aged patients with BC who were more optimistic in the post-surgical period reported less perceived cognitive impairments and greater perceived cognitive abilities, and those who had poorer sleep quality reported worse perceived cognitive abilities and greater impact of perceived cognitive impairments on quality of life. Additionally, our results suggest that optimism may buffer the impact of poor sleep quality on perceived cognitive impairments. Contrary to our hypotheses, physical activity was not significantly associated with perceived cognitive impairment.

The results of this study are consistent with previous literature documenting associations between optimism and cognitive impairment in older adults (Dos Santos et al., 2018; Gawronski et al., 2016; James et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Sachs et al., 2023) and cancer populations (Taber et al., 2016). In this sample of middle-to-older aged patients with BC, optimism was strongly associated with greater perceived cognitive abilities and lower perceived cognitive impairments. There were modest effects of optimism on the impact of perceived cognitive impairments on quality of life and comments from others; however, these were non-significant.

These findings add to a much larger literature in which optimism and physical health have long been associated, and the work in this literature provides three potential theories as to the mechanisms that may underly the association between optimism and CRCI (Scheier & Carver, 2018). First, more optimistic individuals may tend to persevere through stress even when adversity is encountered and employ more adaptive coping strategies to face the stressor (Scheier et al., 1986). This could mean that even when a challenge to memory or concentration occurs, optimists continue to attempt to remember or concentrate for longer than pessimists and may employ strategies to cope with cognitive decline, such as learning about CRCI, engaging in positive behaviors that may improve their cognition, or seeking support from their large social support networks. Second, because optimists are more likely to employ more adaptive coping strategies, they are more likely to experience a decrease in long-term distress which may lead to a decrease in biological stress and sympathetic nervous system hyperactivation, which may in turn slow biological aging, leading to less cognitive decline (Mandelblatt et al., 2025, 2023; Scheier & Carver, 2018; Segerstrom, 2001). Pessimists, on the other hand, often use avoidant coping strategies and engage in damaging health behaviors like alcohol use or smoking, which may only further exacerbate distress and accelerated biological aging (Scheier & Carver, 2018). Third, it may be that optimists objectively have similar levels of CRCI but do not perceive declines in cognition as pessimists do. One study found that optimists have an attention bias towards rewarding stimuli rather than punishing stimuli (Kress et al., 2018), and another found that “pessimistic” rats were more prone to negative feedback than “optimistic” rats (Rygula & Popik, 2016). It may be that pessimists tend to be more sensitive to noticing and dwelling on evidence of their cognitive problems when they present themselves whereas optimists may focus on evidence to support cognitive successes rather than cognitive problems. This theory is supported by a meta-analysis, which found that there were significantly larger effects of optimism on physical health when subjective measures were used rather than objective measures; however, it should be noted that there was a significant effect of optimism on physical health when objective measures were employed (Rasmussen et al., 2009).

Similarly, as hypothesized, poor sleep quality was significantly associated with poorer perceived cognitive abilities and impairments on quality of life, extending previous findings (Garland et al., 2024; Henneghan, 2016; İzci et al., 2020; Liou et al., 2019) to BC patients in the post-surgical period, where sleep disturbance is a prevalent problem (St Fleur et al., 2022). Perceived cognitive impairments and comments from others were not significantly associated with sleep quality; however, both models had modest effect sizes and trended towards significance, which potentially suggests that the lack of statistical significance may be due to low power rather than the effect not truly existing. These results are not entirely surprising as poor sleep has widely been associated with poor attention, concentration, and memory in healthy populations due to altered brain function and connectivity (Khan & Al-Jahdali, 2023; Krause et al., 2017). However, sleep may also be acting through biobehavioral pathways to reduce the impacts of surgery and cancer-related distress on CRCI. During sleep, circulating levels of stress hormones drop (Besedovsky et al., 2012); reductions in norepinephrine and epinephrine reduce the binding of hormones to β-adrenergic receptors and reduce signaling cascades that activate the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes, and these reductions in gene transcription lead to a reduction of the overall systemic inflammation (Irwin & Cole, 2011) that exacerbates CRCI (Carroll et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2019). Moreover, much of the sample (64.3 %) suffers from clinical levels of sleep disturbance suggesting that sleep is a particular health behavior that needs to be improved during the post-surgical period. Interventions like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (Garland et al., 2024), Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management (Vargas et al., 2014), or Tai Chi (Irwin et al., 2014), may be beneficial to improving sleep and decreasing inflammation, accelerated aging, and CRCI in women before they receive adjuvant cancer therapy.

A novel finding was that optimism buffered the relationship between poor sleep quality and CRCI. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a moderator on the relationship between sleep quality and CRCI in any cancer population. Among those high in optimism, poor sleep quality was not associated with perceived cognitive impairments, while among those low in optimism, poor sleep quality was significantly associated with greater perceived cognitive impairments. As stated previously, this finding may be due to a number of factors; optimists employing more adaptive coping strategies, persisting through cognitive challenges, reduced distress and stress biology, or optimistic attention bias. Modifiable optimistic behaviors like employing more adaptive coping strategies should be further investigated as a mechanism in the pathway with great potential to be targeted with psychosocial interventions.

Surprisingly, physical activity was not significantly associated with any measures, and effect sizes from the models were minimal to small, which adds to the mixed literature on the benefits of physical activity on CRCI. There may be a few reasons as to why minimal effects were seen for physical activity. First, a weakness of the PASE and similar subjective measures of physical activity is the potential for recall bias. Participants may have inaccurately recalled how often or how long they performed an activity, which may have led to null results. Second, there may be potential ceiling effects as physical activity scores were extremely high in this sample. Only 33 % of participants reported PASE values under the mean found in a healthy sample, which is likely due the majority of our participants being on the younger side of older-adulthood (Washburn & Ficker, 1999). Additionally, the majority of participants (78.5 %) met DHHS guidelines for hours of moderate to vigorous activity per week, which further supports the claim of high activity in this sample. However, the majority of participants (83.5 %) did not meet the full DHHS guidelines because they did not endorse engaging in muscle strengthening activities. This, taken with the mixed literature, suggests that greater nuance may be required to understand the effects of physical activity on CRCI during the post-surgical period; it might not solely matter whether the patients are engaging in activity, but rather the kinds of activities they are engaging in may also be critical. There has been some preliminary evidence to support this in patients with BC during other periods in BC treatment. One study in BC patients undergoing adjuvant therapy found that resistance training in addition to aerobic training significantly improved self-reported cognitive function compared to treatment as usual, but aerobic training alone did not significantly improve cognitive function compared to treatment as usual (Mijwel et al., 2018). Another study found that participants engaging in an intervention that included a combination of strength and aerobic training also reported better cognitive function compared to a treatment as usual control group (Koevoets et al., 2022). Moreover, the intensity of activity may also be important as well. Previous work has found that moderate to vigorous physical activity has been linked to better self-reported cognition in breast cancer survivors (Artese et al., 2024; Hartman et al., 2024). However, the link between activity intensity and cognition may be more nuanced as a nationally representative study of healthy mid-to-older adults found that those with both high levels of light physical activity paired with average levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity was associated with less cognitive decline over 9 years compared to those with low levels of physical activity (Hamm et al., 2025). However, further investigation is required to better understand the nuance of the effects of physical activity type and intensity on CRCI in the post-surgical period.

The current study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of optimism and health behaviors on CRCI in a sample of middle-to-older aged women with BC during the post-surgical period as well as to examine optimism as a buffer on the relationship between poor engagement with health behaviors and CRCI. Additionally, this study makes use of well-validated measures, and results held with the adjustment of relevant covariates based on prior literature. However, the results of this study should also be considered in light of several weaknesses. First, the small sample size limits the power of the study to detect small to medium effects, and therefore, there may have been important effects present that the study was not powered to detect. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to examine mediators of optimism effects on CRCI. Moreover, the study employs subjective measures of CRCI, sleep quality, and physical activity rather than objective measures like extensive neurocognitive testing, actigraphy, and accelerometers, which may be less subject to attention bias and recall bias. Finally, the limited racial diversity of the study limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should investigate the relationship between sleep, optimism, and CRCI with objective neurocognitive testing over the course of treatment and into survivorship in a more diverse sample. Additionally, studies investigating underlying biobehavioral mechanisms (e.g. neuroimmune drivers of cancer-accelerated biological aging) may be helpful in understanding associations between optimism and sleep quality on CRCI.

Despite these limitations, the results provide preliminary evidence that dispositional optimism may play a critical role in improving CRCI and buffering the negative effects of poor sleep quality on CRCI in middle-to-older aged patients with BC during the post-surgical period. Taken together, these findings suggest that interventions that promote optimistic expectancies while improving sleep may be beneficial as an adjunct therapy in middle-to-older aged patients with BC during the post-surgical period.

FundingThis research is supported by the Florida Department of Health (6BC06), Florida Breast Cancer Foundation, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, & University of Miami Maytag Fellowship.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests Michael Antoni reports a relationship with Blue Note Therapeutics that includes: consulting or advisory. Michael Antoni has patent #UMIP-483 licensed to University of Miami. Co-author is an author of books and treatment manuals on stress management for which he receives a small royalty - MA If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.