Edited by: Assoc. Professor Joaquim Reis

(Piaget Institute, Lisbon, Portugal)

Dr. Luzia Travado

(Champalimaud Foundation, Lisboa, Portugal)

Dr. Michael Antoni

(University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, United States of America)

Last update: November 2025

More infoPsychosocial adaptation to cancer involves interactions among emotional, cognitive, and biological processes. Although the efficacy of psychological interventions is well documented, the mechanisms linking psychological adaptation to physiological outcomes remain fragmented across disciplines. The Special Issue of the International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, “Advancing Health Psychology Research in Oncology: Biobehavioral Models, Stress Pathways, and Stress-Management Interventions for Cancer Patients” addresses this gap and this paper serves as an overview.

As an overview for the Special Issue, this paper proposes an integrative biobehavioral model that synthesizes findings on brain function, stress-response systems, and psychosocial variables to explain how stress management interventions— including those delivered via digital platforms—may influence health trajectories in cancer care.

Using a targeted narrative approach, we draw upon recent empirical findings and prior integrative reviews conducted by the authors to examine: (a) the impact of perceived stress and inflammation across the cancer continuum; (b) brain-body stress response pathways linking affective, neuroendocrine, and immune function; (c) the evidence for psychological interventions to modulate these systems and improve behavioral and health outcomes; (d) future challenges for this line of research and cancer care.

Evidence suggests that cancer-related distress is associated with neural and immune dysregulation, with inflammation emerging as a central pathway. Stress management interventions, based on cognitive-behavioral theory and using digital delivery modalities, show promise in altering these biobehavioral mechanisms, thereby enhancing resilience, quality of life, and potentially long-term health outcomes in cancer survivors.

A cancer diagnosis often carries a life-threatening prognosis, confronting patients with profound psychological and physical challenges. This journey, spanning diagnosis, treatment, remission or progression, and survivorship or end-of-life care, imposes unique emotional demands at each stage (Deshields et al., 2014; Sheikh-Wu et al., 2023; Young et al., 2020). Emotional instability, loss of autonomy, and dependency frequently elevate cancer-related distress, which often manifests as anxiety and depression. These emotional states are not only distressing but when persisting are also associated with poorer health outcomes, including reduced quality of life and increased mortality risk (Mehnert et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2012; Okeke et al., 2023; Spiegel, 2012; Zabora et al., 2001). Beyond psychological burden, symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and impaired concentration further compound the challenges faced by patients (Blaxton et al., 2017; Bovbjerg, 2003; Payne et al., 2006; Roscoe et al., 2007; Strollo et al., 2020).

The biological mechanisms underpinning cancer-related distress involve the activation of key stress-response systems, including the sympathetic nervous system (SNS)-associated activation of brainstem and noradrenergic neurons along the spinal ganglia and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axes (Gianaros & Wager, 2015). Chronic stress, however, can disrupt these systems, leading to maladaptive responses, including the sustained release of catecholamines and glucocorticoids, which can promote angiogenesis, tumor progression, and immune dysfunction, exacerbating both cancer outcomes and comorbidities (Antoni et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2022; Cole et al., 2015; Falcinelli et al., 2021; Petrova et al., 2021; Spiegel, 2012). For example, chronic stress has been shown to increase levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) (Antoni et al., 2006; Coussens & Werb, 2002) which can promote tumor growth and metastasis (Ben-Baruch, 2022; Chen et al., 2022). Chronic stress may also contribute to cancer-accelerated aging (Guida et al., 2019; Mandelblatt et al., 2024) hastening immune senescence and atherosclerosis, which may amplify comorbid conditions in cancer survivors (Reis et al., 2020). These pathways, while well-established in isolation, have rarely been examined together through an integrative neurobiological perspective, which we propose is central to understanding the health effects of cancer-related distress and stress management interventions. This highlights the importance of addressing distress comprehensively to mitigate both its psychological and physiological impacts. Understanding the bidirectional communication between the brain and body systems is fundamental to elucidating how stress contributes to health and disease. This complex interaction is especially relevant in chronic conditions such as cancer, where psychological stress and biological processes intersect, influencing emotional states, immune function, and overall health outcomes (Dantzer, 2018; Pavlov & Tracey, 2017a). Neuroimaging studies have provided critical insights into the neural mechanisms underlying stress and resilience, revealing changes in brain regions associated with emotional regulation and stress processing in cancer patients (Reis et al., 2020a, 2023, 2020b). The evidence reviewed in this paper reflects targeted, empirically grounded selections from the literature, informed by our prior integrative review (Reis et al., 2020a). While not systematic in scope, this narrative approach allows for a coherent synthesis of emerging cross-domain evidence relevant to stress-related adaptation in cancer. Furthermore, stress management interventions, including Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management (CBSM), have been shown to improve psychological adaptation, modulate neuroendocrine and immune responses, and enhance clinical outcomes, such as disease-free survival and overall survival (Antoni et al., 2023).

The present overview. Psychosocial adaptation to cancer involves dynamic interactions among emotional, cognitive, and biological processes. Although the efficacy of psychological interventions is well documented in facilitating adaptation, the mechanisms linking psychological adaptation to physiological outcomes remain fragmented across disciplines. This Special Issue of the International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, “Advancing Health Psychology Research in Oncology: Biobehavioral Models, Stress Pathways, and Stress-Management Interventions for Cancer Patients” addresses this gap in the literature and this paper serves as an overview for the Special Issue.

To better understand these complex interactions, we previously proposed an integrative biobehavioral model that underscores the interconnected pathways through which stress, neural processing, and immune responses influence cancer trajectories (Reis et al., 2020a). This model organizes key processes into seven domains, encompassing psychosocial adaptation, neurobiological mechanisms, biobehavioral pathways, tumor biology, health behaviors, clinical outcomes, and stress-management interventions. The present overview builds on our integrative model, incorporating recent advancements in biobehavioral research and psychosocial interventions, with emphasis on specific domains relevant to cancer-related stress and adaptation. What distinguishes this article is its integration of updated findings linking CNS/brain activity with peripheral biobehavioral processes, and its emphasis on how behavioral, and in some cases, pharmacological interventions, may modulate both systems to optimize health outcomes in cancer patients. We begin by exploring the physiological and neural mechanisms through which stress influences cancer progression, highlighting the role of the SNS, HPA axis, and immune dysregulation. Next, we delve into the bidirectional communication between the brain and body, emphasizing how cognitive and emotional processes shape physiological responses and how peripheral signals, such as cytokines, influence brain function and behavior. We then examine the impact of psychosocial stress on cancer biology, including the role of the Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity (CTRA) (Cole et al., 2015) and the effects of chronic stress on tumor progression and metastasis. Additionally, we discuss the influence of social and environmental determinants, such as neighborhood disadvantage, on cancer outcomes and the potential of social support to mitigate these effects. Finally, we review the efficacy of CBT-based interventions including those categorized as stress management interventions (SMIs) in improving psychological adaptation, modulating biobehavioral processes, and enhancing clinical outcomes. Finally, we address the challenges and limitations of implementing digital SMIs, such as low engagement and accessibility barriers, while highlighting their potential to expand the reach of evidence-based care. By integrating these insights, we aim to provide a comprehensive perspective on the biobehavioral processes underlying cancer-related distress and to inform future research and clinical applications aimed at improving patient well-being and outcomes.

From brain to body: how stress shapes health and diseaseWhile acute stress responses are evolutionarily adapted to enhance short-term survival, chronic stress leads to sustained dysregulation of the SNS and HPA axis, disrupting brain function and peripheral physiological systems, including the cardiovascular, immune, and endocrine systems (Davidson & McEwen, 2012; McEwen et al., 2016). These effects can persist long-term, as psychological stress experienced during childhood and adolescence has been associated with an increased risk of health problems across the lifespan, with inflammation recognized as a key underlying mechanism (Chiang et al., 2022). Psychological stress arises from the cognitive appraisal of events perceived as threats (Scherer & Moors, 2019). As the central regulator of stress and adaptation, the brain integrates sensory, cognitive, and emotional inputs to appraise events and orchestrate physiological and behavioral responses aimed at maintaining adaptive regulation (McEwen, 2012).

Physiological responses to stressStress triggers a set of physiological responses: SNS activation of the locus coeruleus (LC) in the Pons, which produces norepinephrine (NE) and stimulates noradrenergic ganglia along the spinal column and their projections to release NE into multiple organs; and activation of the sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) axis, which releases NE and epinephrine (E) from the adrenal medulla, and activation of the HPA axis, which releases cortisol from the adrenal cortex into the circulation (Godoy et al., 2018; Russell & Lightman, 2019). When these systems are persistently activated, stress-related pathways can disrupt immune and inflammatory processes, contributing to a cascade of effects that exacerbate health conditions (Alotiby, 2024; Bower & Irwin, 2016; Gupta & Agarwal, 2024). For example, chronic stress has been shown to suppress immune function, increasing susceptibility to infections and potentially accelerating tumor growth (Bernabe, 2021; Cui et al., 2021; Lutgendorf & Sood, 2011; Mravec et al., 2020).

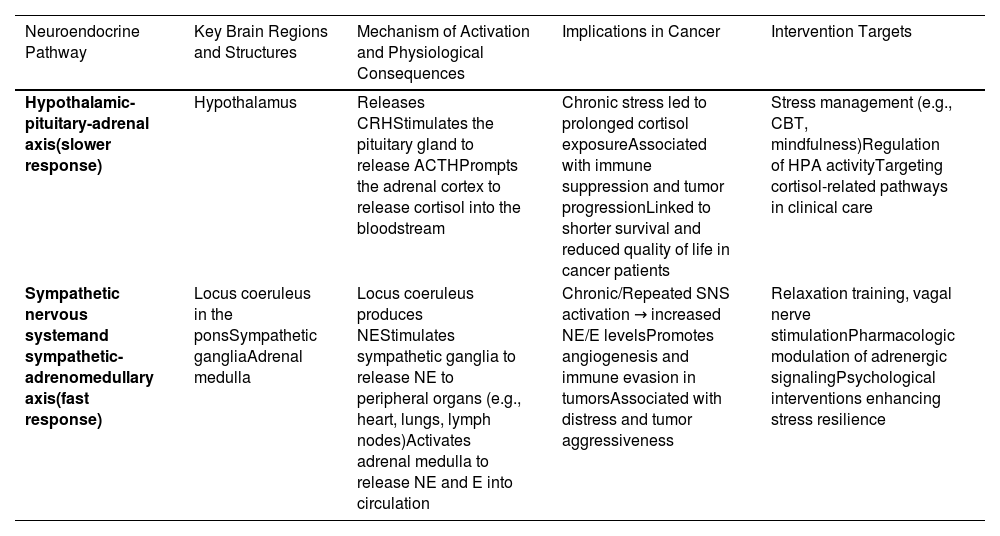

Stress and cancer progressionPsychosocial adversity, including emotional distress, has been shown to worsen clinical outcomes, reducing survival times and compromising quality of life in cancer (Antoni et al., 2006; Giese-Davis et al., 2011; Lutgendorf & Andersen, 2015; Zhou et al., 2020). For instance, chronic stress has been associated with increased angiogenesis and immune evasion in breast cancer models, highlighting the complex interplay between stress and tumor biology (Antoni et al., 2006; Bernabe, 2021; Cui et al., 2021; Eckerling et al., 2021a; Falcinelli et al., 2021; Giese-Davis et al., 2011; Lutgendorf & Andersen, 2015; Zhou et al., 2020). These may explain the established association between chronic states of distress and shorter disease-free interval and overall survival. To clarify the physiological and clinical relevance of these stress-related mechanisms, Table 1 summarizes the major neuroendocrine pathways activated by psychological stress, their effects on cancer progression, and key psychosocial and biological intervention targets.

Neuroendocrine stress response: implications for cancer and intervention targets.

This table outlines the principal neuroendocrine pathways activated by psychological stress: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which mediates slower hormonal responses, and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), including the sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) axis, responsible for rapid physiological responses. Dysregulation of these systems can impair immune function and contribute to cancer progression. Evidence-based psychosocial and biological intervention targets relevant to each are also summarized.

HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; NE, norepinephrine; E, epinephrine; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Although evidence links stress to cancer outcomes, the neural mechanisms underlying individual variations in emotional responses remain insufficiently explored. Understanding these mechanisms is critical, as they may explain why some individuals exhibit greater resilience to stress, while others are more susceptible to its adverse effects on health. Stress appraisals and coping processes are mediated by a network of brain regions involved in evaluating environmental threats and orchestrating physiological and behavioral adaptations (McEwen, 2012, 2017a; Peters et al., 2017). Key regions implicated in this process include the lateral prefrontal cortex (lPFC), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and insula, which process sensory and emotional information, enabling adaptive responses to uncertainty (Peters et al., 2017; Reis et al., 2020a). Uncertainty—a defining feature of stress in cancer patients—activates these neural networks (Peters et al., 2017), leading to dynamic interactions between cognitive appraisal, decision-making, and emotional regulation (Ahadzadeh & Sharif, 2018; Mishel, 1988, 1999).

A review of neuroimaging studies with cancer patients that examined the associations between negative affect (distress) and differences in the metabolism or structure of brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, cingulate cortex (mainly subgenual area), hypothalamus, basal ganglia (striatum and caudate), and insula, which are associated with greater anxiety, distress, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms (Reis et al., 2020a). More recent studies with metastatic breast cancer patients, showed that higher perceived stress is associated with reduced activity in regions such as the insula, thalamus, and hypothalamus, while greater perceived stress management skill efficacy correlates with enhanced activity in these areas (Reis et al., 2023, 2020b). These findings underscore the possible role of these brain circuits in mediating resilience and emotional adaptation in cancer patients. Interestingly, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has been shown to increase activity in the ACC and vmPFC, regions associated with emotional regulation and stress resilience (Creswell, 2017).

Integrating these insights into clinical practice is essential. By targeting the neural mechanisms underlying stress and resilience, neuroscience-informed psychosocial interventions have the potential to enhance brain function, alleviate distress, and improve psychological well-being and clinical outcomes in cancer care. Future research should prioritize multidisciplinary approaches that combine psychosocial assessments with neuroimaging, immune, and neuroendocrine markers. Such efforts will be essential for developing targeted interventions to enhance outcomes in cancer care. For example, personalized treatment approaches could use biomarkers to tailor interventions to individual patients.

Body to brain, brain to body: the bidirectional dance of communicationUnderstanding the dynamic bidirectional communication between the brain and body is essential for uncovering how psychosocial stress interacts with and influences cancer biology and health outcomes. This communication operates through both top-down and bottom-up pathways, creating a continuous feedback loop where cognitive and emotional processes influence physiological responses, and peripheral signals inform and modulate brain function. While top-down pathways regulate physiological systems through cognitive and emotional control, bottom-up pathways play a complementary role by transmitting immune and sensory signals to brain regions (Dantzer, 2018; Mravec et al., 2008; Pavlov & Tracey, 2017b; Reardon et al., 2018; Taylor et al., 2010).

Brain to body: cognitive and emotional regulationTop-down pathways emphasize cognitive and emotional regulation, such as cognitive appraisals of stressors and coping processes, which shape both emotional responses and physiological adaptations (Davidson & McEwen, 2012; Franks & Roesch, 2006; McEwen, 2009, 2017b). Interventions like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) leverage these mechanisms by employing techniques such as cognitive reframing to reinterpret stressors and modify maladaptive thoughts (Hofmann et al., 2013). These interventions not only reduce subjective reports of distress but also positively modulate neuroendocrine and autonomic systems, which could improve health outcomes (Nakao et al., 2021). For example, psychosocial interventions including CBT and relaxation training reduce cortisol in breast cancer patients (Antoni et al., 2023; Mészáros Crow et al., 2023).

Body to brain: peripheral signals and brain activityIn contrast, bottom-up pathways highlight the role of peripheral signals in shaping brain activity. Cytokine signaling exemplifies bottom-up communication. Cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α), transmit information about inflammation and immune responses to the brain, influencing emotional regulation, behavior, and cognitive functions (Goshen & Yirmiya, 2009; Kronfol & Remick, 2000; Quan & Banks, 2007; Wilson et al., 2002; Yirmiya & Goshen, 2011). One of these influences is the trigger of “sickness behaviors” like fatigue and anhedonia (Dantzer et al., 2008; Dantzer & Kelley, 2007). In cancer patients, pro-inflammatory cytokines mediate these pathways, exacerbating cognitive dysfunction (often referred to as “cancer-related cognitive impairment” or CRCI) (Hurria et al., 2007) and stress-related symptoms (Kesler, 2014). Interventions such as biofeedback and vagus nerve stimulation target these pathways to enhance emotional resilience and systemic health (Taylor et al., 2010). These interactions underscore the complex feedback loops through which immune and neural dysregulation perpetuate one another.

Interoception and allostasis: bridging brain and bodyTo better understand these feedback loops, it is essential to consider the roles of interoception and allostasis in bidirectional brain-body communication. Interoception refers to the brain’s capacity to perceive and interpret sensory signals from within the body, providing an internal map of physiological states (Strigo & Craig, 2016). This process, encompassing dimensions such as attention, accuracy, sensitivity, and insight, is fundamental to shaping how individuals experience and respond to bodily signals (Khalsa et al., 2018). Through key brain regions like the ACC, insula, and hypothalamus, interoception translates physiological states into conscious experiences, shaping emotion, behavior, and stress responses. Allostasis complements this process by dynamically regulating internal states to ensure adaptive responses to changing demands. This system relies on the interplay between top-down predictions and bottom-up interoceptive signals to fine-tune energy management. Allostasis emphasizes predictive regulation, enabling the brain to anticipate and meet energy needs by balancing resources proactively (Barrett & Simmons, 2015; Hutchinson & Barrett, 2019; Sterling, 2012). However, chronic dysregulation of this system can lead to overestimations of energy requirements, disrupting homeostasis and contributing to immune dysfunction and systemic inflammation (Barrett & Simmons, 2015) with long-term effects on the viability of immune cells and poor health outcomes. For instance, allostatic load refers to energetic burden required to support allostasis and stress-induced energy needs (Bobba-Alves et al., 2022) with a resultant breakdown in immune defenses, poor metabolic control (rising HbA1c levels) and chronic generation of inflammatory signals, which may lead to cellular hypermetabolism or excess energy beyond an organism’s optimal range, and is hypothesized to drive biological aging (Picard et al., 2018). This may explain the confluence of cancer, its treatments and chronic stress on accelerated biological aging (Antoni et al., 2023; Guida et al., 2019) and the development of co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease (Mehta et al., 2018).

Psychosocial interventions: targeting interoceptive and allostatic dysregulationPsychosocial interventions, such as CBT, directly target interoceptive and allostatic dysregulation by enhancing emotional regulation and fostering greater awareness and mastery over the interpretation of bodily sensations. CBT employs techniques such as interoceptive exposure to help individuals confront and reinterpret distressing internal sensations, reducing avoidance behaviors and maladaptive responses (Funaba et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2006). These interventions have been shown to restore functionality in brain regions central to interoception, including the ACC, insula, and prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Aupperle et al., 2013; Goldapple et al., 2004; König et al., 2025). By recalibrating interoceptive pathways, these interventions aim to restore balance within the broader allostatic system (Deacon et al., 2013).

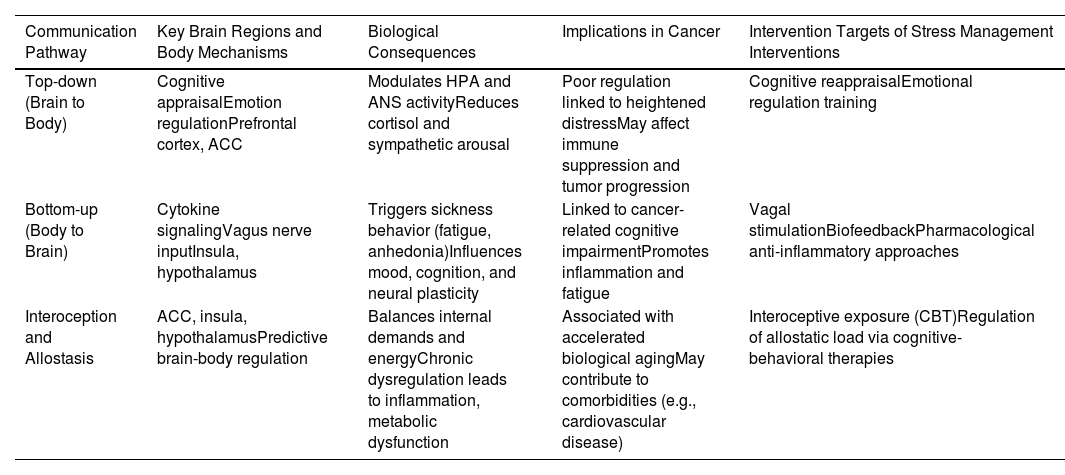

In conclusion, integrating insights from stress neuroscience, biobehavioral processes, and psychosocial interventions provides a comprehensive framework for understanding cancer-related distress. By addressing interoceptive and allostatic dysregulation, psychosocial interventions offer a pathway to improve emotional regulation and systemic health. Future research should prioritize multidisciplinary approaches that combine psychosocial assessments with neuroimaging, immune, and neuroendocrine markers. Such efforts will be essential for developing targeted interventions to enhance outcomes in cancer care. For example, personalized medicine approaches could use biomarkers to tailor interventions to individual patients, while digital health tools (e.g., biofeedback, CBT and mindfulness apps) could enhance accessibility and effectiveness. To visually synthesize the core mechanisms discussed, Table 2 presents a summary of the bidirectional brain–body communication pathways involved in psychosocial stress and their relevance to cancer biology and care.

Bidirectional brain-body communication in psychosocial stress and cancer.

This table illustrates top-down and bottom-up pathways involved in brain-body communication during psychosocial stress. It highlights relevant mechanisms such as interoception and allostasis, their implications for cancer outcomes, and targeted psychosocial interventions.

ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; ANS, autonomic nervous system; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

Several recent reviews have focused on research establishing associations between indicators of psychological adaptation, biobehavioral processes and clinical health outcomes in cancer (Antoni et al., 2023; Chang et al., 2022; Eckerling et al., 2021b).There is an emerging consensus, based on studies of animal models and humans, that exposure to persisting and uncontrollable stressors and social isolation, and experiencing depression, anxiety and chronic stress are associated with: (1) Neuroendocrine dysregulation - Characterized by elevated cortisol levels and disrupted diurnal secretion patterns, increased norepinephrine levels, and altered leukocyte and tumor gene expression reflecting SNS activation (e.g., upregulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element-binding protein (CREB)) and glucocorticoid resistance; (2) Immune system dysregulation – Marked by weakened cellular immune function and down-regulated leukocyte expression of anti-viral genes (e.g., interferon type I and II), and increased circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, leukocytes show upregulation of genes involved in inflammatory cytokines, chemokine signaling, oxidative stress, and wound healing; (3) Cancer progression and pro-metastatic processes – Including angiogenesis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and anoikis resistance, all of which contribute to tumor survival and dissemination and, (4) Clinical health outcomes - Such as cancer metastasis and increased mortality risk.

The neuroimmune patterning revealed in these studies often converges on an association between states of threat and adversity with a distinct transcriptional signature involving the differential expression of 53 genes in immune and tumor cells. This pattern, known as the Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity (CTRA), is characterized by: (1) down-regulation of “protective” genes involved in anti-viral and anti-tumor immune responses; and (2) upregulation of pro-inflammatory and pro-metastatic genes, which promote chronic inflammation, tumor progression and metastasis (Cole et al., 2015). This transcriptional shift underscores the biological embedding of psychosocial stress, linking it to immune dysfunction and cancer progression through well-defined molecular pathways. Several studies have established a strong link between elevated CTRA expression, psychosocial adversity, and poorer clinical outcomes in cancer patients. For example, in women with ovarian cancer, higher tumor CTRA expression has been associated with greater depression and lower social support (Chang et al., 2022). Conversely, interventions that reduce stress appear to mitigate CTRA expression and improve health outcomes. In breast cancer patients, stress management through Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management (CBSM) has been shown to lower leukocyte CTRA expression, a change that parallels reductions in negative affect and predicts longer disease-free survival (Antoni et al., 2016). These findings underscore the intricate interplay between psychosocial factors, immune system regulation, and cancer progression, suggesting that targeted stress management may offer a pathway to improved clinical outcomes.

Social and environmental determinants of health in cancer: biobehavioral processesOver the past few years there has been a growing interest in applying this biobehavioral oncology approach to better understand the mechanisms underlying well-documented disparities in cancer outcomes linked to sociodemographic factors such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Miller et al., 2017). One key area of research attention focuses on the role of chronic adversity states to explain the poorer health outcomes in women with breast cancer (Goel et al., 2024). Work using geo-epidemiological methods has identified how structural features in the neighborhoods and living conditions of breast cancer patients in the U.S. are linked to poorer survival, even after controlling for disease and treatment factors (Goel et al., 2023). These sources of chronic adversity may contribute to cancer progression and poor clinical outcomes through stress-related “biobehavioral” pathways, reflected in immune and tumor cell activity linked to the CTRA gene expression profile (Goel et al., 2024). Recent findings indicate that breast cancer patients living in more disadvantaged neighborhoods – determined using geocoding systems like the Area Deprivation Index (Kind & Buckingham, 2018) exhibit higher circulating levels of cortisol and increased anxiety symptoms (as assessed by interviews) (Goel et al., 2023), and more aggressive tumors (Goel et al., 2023). In a separate cohort of patients greater ADI was associated with elevated SNS activity, reflected in the expression of stress-responsive genes such as CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) and with CTRA-patterned gene expression in their tumors (Goel et al., 2024) both of which were in turn related to poorer recurrence-free survival. Furthermore, higher perceived overall subjective reports of neighborhood adversity and concerns over safety were also strongly associated to greater tumor SNS activity and CTRA-patterned gene expression (Goel et al., 2024) in this cohort suggesting that some processes (e.g., stressor appraisals) may be modifiable with CBT-based stress management interventions.

Among the potentially modifiable targets being studied in this context are social support and stress management skill efficacy. Evidence suggests that perceived social support and stress management skill efficacy may moderate (buffer) the effects of both cancer-related and environmental stressors on psychological outcomes (e.g., anxiety), neuroendocrine responses (e.g., cortisol levels), and inflammatory markers and leukocyte inflammatory gene expression in breast cancer patients (Diaz et al., 2021; Jutagir et al., 2017; Reis et al., 2022; Taub et al., 2019). Recently investigators observed that the effects of neighborhood disadvantage on cortisol elevations were mitigated in post-surgical breast cancer patients reporting greater social support (Hernandez et al., 2025a). Similarly, in another cohort of over 5000 breast cancer patient’s greater neighborhood disadvantage (measured by higher ADI scores) predicted shorter survival. However, this effect was mitigated in patients living in an ethnic enclave—a geo-region characterized by high Hispanic density (Hernandez et al., 2025b). Another study found among breast cancer patients living in Higher ADI neighborhoods that those reporting greater stress management skill efficacy and active coping and social support showed lower subjective neighborhood adversity (Taub et al., 2025). Together these studies reinforce the need for interventions that build stress management skills and foster supportive social environments. Such interventions can help modulate neural-mediated psychological adaptation (e.g., mood, distress, sense of efficacy), regulate neuroendocrine processes (e.g., HPA axis, SNS activity) and reduce leukocyte and tumor CTRA expression, ultimately improving health outcomes (recurrence-free and overall survival) in cancer patients.

CBT skill training can be particularly beneficial in helping breast cancer patients manage stress and improve psychological resilience. Techniques that focus on modifying stressor appraisals, such as cognitive restructuring and coping skills training, can help patients develop more adaptive ways of interpreting and responding to stress. Additionally, strategies aimed at reducing anxiety and SNS activation, including relaxation techniques, may contribute to improved emotional regulation and physiological stability. Enhancing communication skills is another crucial aspect, as training in assertiveness and social resource utilization can help patients build, maintain, and effectively engage with their support networks.

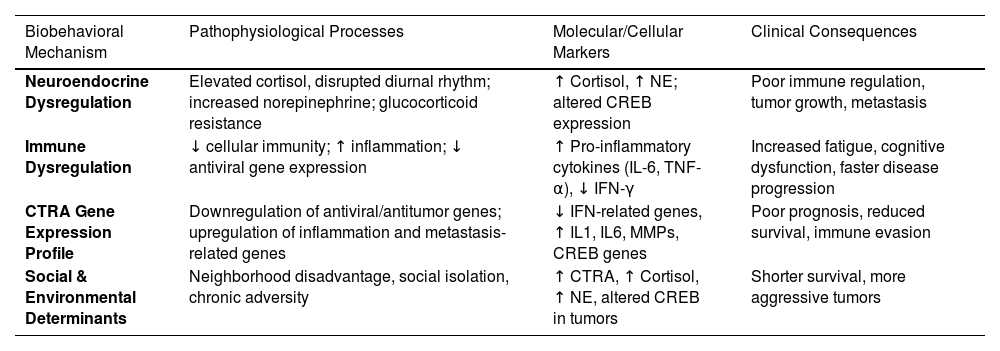

Recent work suggests that CBT-based SMIs such as group-based Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management (CBSM), lowers anxiety and PM cortisol levels in breast cancer patients from high-disadvantage neighborhoods (Ream et al., 2025). These findings indicate potential clinical benefits, particularly for underserved populations, by addressing both psychological distress and stress-related biological pathways that may influence cancer progression and overall health outcomes. However, it is anticipated that these interventions will have to be modified to be relevant to the unique stressors experienced by these populations. Table 3 integrates findings across Sections 4.1 and 4.2, highlighting the main biobehavioral processes through which psychosocial stress, immune function, and contextual adversity contribute to cancer progression and poorer health outcomes

Biobehavioral mechanisms linking psychosocial stress and cancer outcomes.

SNS, Sympathetic Nervous System; HPA axis, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis; SAM axis, Sympathetic-Adrenomedullary axis; NE, Norepinephrine; E, Epinephrine (Adrenaline); CRH, Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone; ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic Hormone; CTRA, Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity; CREB, cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein; PM cortisol, Afternoon/Evening (Post-Meridian) Cortisol Levels; ADI, Area Deprivation Index.

Over the past decade several scoping reviews and meta-analyses have summarized the effects of CBT-based interventions including those categorized as SMIs on a wide variety of outcomes in cancer patients (Antoni et al., 2023). This body of research provides evidence for improvements in psychological adaptation such as reductions in anxiety, depressive symptoms and distress as well as enhancements in quality of life (Getu et al., 2021). Additionally, SMIs have been shown to alleviate physical symptoms and treatment-related side effects, including sleep disturbances and fatigue (Cobeanu & David, 2018). Their impact extends to biobehavioral processes as demonstrated by changes in serum, cellular and molecular markers of neuroendocrine function, cellular immune activity and inflammation (Antoni et al., 2023; Antoni & Dhabhar, 2019). Moreover, evidence suggests that these interventions may influence clinical health outcomes, including disease-free survival and overall survival (Eckerling et al., 2021a; Mirosevic et al., 2019; Oh et al., 2016). In addition to demonstrating the efficacy of psychological interventions, this research—supported by a strong evidence base—has also identified potential biobehavioral mechanisms that may explain their long-term effects on clinical outcomes. Despite these promising findings, a major contemporary challenge of psycho-oncology is effectively disseminating these interventions to cancer centers where primary oncology care is delivered, ensuring they are both cost-effective and accessible to the most disadvantaged populations, who are likely to benefit the most. Persistent cultural, ethnic, and racial disparities in cancer morbidity and mortality further underscore the urgency of this issue, yet there is limited data on whether SMIs can help reduce these disparities (Antoni et al., 2023). This gap in knowledge likely stems from barriers to accessing evidence-based behavioral interventions among lower SES and marginalized cancer patients, particularly those in remote areas who lack proximity to specialized cancer centers. Even in well-funded settings, staffing shortages limit the widespread implementation of these interventions. Addressing these challenges in accessibility and healthcare resources requires harnessing technological advances in telecommunication while also recognizing the need to tailor interventions to the unique needs of diverse populations. Here, we focus on recent technological innovations for delivering empirically validated SMIs.

Technology-enhanced and remote interventionsRecent reviews have highlighted numerous ways in which technology-enhanced and remotely delivered behavioral and psychological interventions can expand the reach of patient-centered care in oncology. One review identified several innovations that may improve symptom management, health-related quality of life, and other patient-reported outcomes (Penedo et al., 2020). These include integrating psychological interventions and measurement tools into electronic health records (EHRs) and leveraging patient portals to enhance communication between patients and providers (Penedo et al., 2020). However, the review also underscored significant challenges related to accessibility, scalability, and implementation, which must be addressed for these approaches to be effectively integrated into routine care.

Since this review, a growing number of studies have provided evidence supporting the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of various electronic (e-Health) and mobile-based (m-Health) interventions across different cancer populations. These interventions have been delivered and tested either independently or as hybrid models, using both synchronous and asynchronous formats. They include: (1) telehealth sessions facilitated by human providers, (2) web-based platforms and mobile applications, and (3) virtual human agents.

Telehealth sessionsTelehealth is broadly defined as the use of remote or virtual technologies in healthcare. However, in the practice of psychological interventions, it most commonly refers to synchronous, scheduled sessions facilitated by a therapist via phone or videoconferencing. These sessions can be delivered in individual, dyadic, or group-based formats (Walsh, Safren, Penedo & Antoni, 2024). Recent completed clinical trials using videoconferencing to deliver CBT-based interventions have demonstrated feasibility and acceptability across various cancer populations, including: (a) middle-to-older-aged breast cancer patients undergoing primary treatment (Walsh et al., 2023); (b) older Spanish-speaking men who recently completed treatment for prostate cancer (Penedo et al., 2018); (c) breast cancer patients on a long-term adjuvant endocrine therapy (AET) regimens (Jacobs et al., 2022); and, (d) young adult cancer survivors (Fox et al., 2024; Oswald et al., 2022). These studies have also identified key patient characteristics associated with higher engagement and benefit from these interventions. Ongoing efforts aim to further refine and adapt these approaches to maximize accessibility and uptake, considering factors such as disease severity and sociodemographic characteristics (Walsh et al., 2023, 2024)

Websites and mobile applications (Apps)Websites and mobile applications are designed as asynchronous resources, allowing users to access them at their convenience. While these platforms often lack direct interaction with a facilitator or therapist, they may include interactive components such as diaries, chat functions, and bulletin boards to enhance user engagement. Many of these interventions have been tested in women with breast cancer. A recent scoping review (Walsh et al., 2024) identified poor engagement as a key limitation of asynchronous platforms and emphasized the need for more precise measurement tools beyond standard usage metrics. The review advocated for applying objective engagement measures using the FITT model (Frequency, Intensity, Time/Duration, and Type of Engagement), originally developed to quantify participation in physical exercise trials. This review analyzed 56 studies published through 2023 that utilized asynchronous telehealth interventions for breast cancer patients, revealing a wide variability in platform types and engagement levels. The reviewed interventions fell into six primary modalities: (1) computer/ web-based platforms; (2) smartphone mobile applications (including one commercial app); (3) virtual assistants (e.g., Amazon Alexa); (4) tablet-based interventions; (5) social media-based interventions, and (6) text message interventions.

The intervention content varied significantly, including CBT, mindfulness-based stress reduction, psychoeducation, exercise programming, communication training, prosocial skills training, and coping effectiveness strategies. This review highlighted both the rapid expansion of digital health interventions in oncology and the inconsistent measurement of engagement across studies. Notably, only about half of the studies assessed the relationship between engagement and patient outcomes. The authors recommended integrating Human-Centered Design principles to improve telehealth development and provided strategies to optimize patient engagement in asynchronous telehealth interventions (Walsh et al., 2024).

Recently completed efficacy trials have demonstrated the potential of standalone mobile applications (apps) that can be either prescribed by an oncologist or independently downloaded by patients. Additionally, trials have evaluated apps integrated within electronic health records (EHRs) to enable continuous monitoring of psychological status and symptom-based algorithms for personalized intervention.

The RESTORE trial, was a national decentralized randomized controlled trial that evaluated a 10-module CBSM-based app called ATTUNE. The study compared ATTUNE to CERENA, a time-matched health information app, in a sample of 449 patients with non-metastatic (Stage I–III) cancers who were either currently receiving systemic treatment or had completed treatment within the past six months (Zion et al., 2023). Over a 12-week period, patients assigned to ATTUNE demonstrated: (a) significantly greater reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms compared to those using CERENA (Zion et al., 2023); and (b) decreased cancer-specific distress and improved quality of life (Taub et al., 2024), further reinforcing the efficacy of CBSM-based digital interventions in oncology care.

Another trial in Norway compared the effects of a CBT-based stress management app and a mindfulness-based stress management app to treatment as usual in 430 women diagnosed with breast cancer 6 - 9 months prior (Svendsen et al., 2023). Each intervention consisted of 10 modules, with 9–16 brief steps per module, covering various stress management techniques, including diaphragmatic breathing, visualization, and attentional focus. These exercises were presented through text, audio, video, and illustrations, making them multimodal and accessible. Although self-guided, the interventions included a built-in 3-day pause between module releases to encourage reflection and practice. The primary outcome of this trial is changes in perceived stress over six months, with secondary outcomes including health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression, fatigue, mindfulness, sleep, and coping skills. Results are pending. Beyond breast cancer, CBT-based apps have also been developed to support adults and children undergoing hematologic stem cell transplants (HSCT) for blood cancers, addressing psychological distress and symptom management (Newcomb et al., 2024; Racioppi et al., 2021; Skeens et al., 2022).

Integration of digital interventions with electronic health records (EHRs)Another research line has focused on integrating distress and depression screening via EHR systems with the use of app-based interventions in cancer patients (Yanez et al., 2023). In this approach, cancer patients with elevated depressive symptoms, identified through screenings done through the patient portal in two large comprehensive cancer centers in the U.S., are participating in a pragmatic Type 1 effectiveness-implementation hybrid study. The trial evaluates the impact of a 7-week CBSM-based app, My Well-Being Guide, compared to treatment as usual, which involves referrals to supportive care within the participating cancer centers. The primary outcomes include changes in depressive symptoms and implementation outcomes over a 12-month period. The trial in ongoing.

Another hospital-based intervention tested CARES, a web-based stepped collaborative care (SCC) model, in 29 oncology outpatient clinics (Steel et al., 2024). Eligible patients presented with elevated levels of at least one of three symptoms—depression, pain, or fatigue. The intervention involved: (a) weekly 50–60-minute CBT-based telehealth sessions delivered by care coordinators via telephone or videoconferencing; (b) pharmacotherapy adjustments, as needed, based on clinician recommendations or patient preference, and (c) a control group receiving standard care, which included symptom screening and referral to healthcare providers. Patients randomized to SCC demonstrated greater improvements in health-related quality of life over six months, with benefits persisting at 12 months (Steel et al., 2024). They also showed greater gains in emotional, functional, and physical well-being, along with reductions in depression, pain, and fatigue symptoms, which were sustained over a 12-month period. Additionally, SCC reduced healthcare costs, as patients in this condition had shorter hospital stays, fewer emergency room visits, and lower 90-day readmission rates. However, SCC did not influence inflammatory cytokines, and its effects on long-term clinical health outcomes are yet to be reported.

Virtual humans (VH) as AI-Based telehealth interventionspositioned between human-delivered telehealth and fully automated digital apps and websites, virtual humans (VH) represent an emerging AI-driven approach that integrates the relational aspects of a teletherapist with the scalability of eHealth and mHealth platforms (Loveys et al., 2023a). These AI-powered agents are designed with human-like embodiments, featuring customizable appearance, voice, and language, along with full-range facial and body expressions that enable real-time emotional and interpersonal interactions. Using “affective computing” (Pei et al., 2024) VHs can mirror users’ facial expressions and analyze vocal cues, transforming speech into text to interpret emotional states. In conversations, VHs collect auditory and visual data, classify facial muscle movements, words, and nonverbal behaviors, and generate verbal and nonverbal responses based on multimodal emotional analysis (Chattopadhyay et al., 2020). This allows them to emulate human-like “empathy” in therapeutic interactions. They have been programmed to engage with humans, conduct interviews and assessments, and deliver a range of interventions including health education (e.g., diet and physical activity guidance) and CBT-based stress management, such as CBSM modules (Loveys et al., 2023a).

Recent randomized controlled trials comparing VH-delivered interventions to teletherapist-led, chatbot-based, and e-manual stress management approaches have demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy in reducing stress and inducing relaxation or mindfulness states across diverse populations, from college students to distressed middle-aged adults (Karhiy et al., 2024; Loveys et al., 2023a; Loveys et al., 2022). Current research is exploring VH-delivered psychological interventions for individuals undergoing cancer treatment. In the future, VHs may also incorporate dynamic digital models of psychoneuroimmunological responses to stress, illustrating how stress impacts cancer progression and how CBT-based interventions can mitigate these effects, thereby enhancing patient motivation for behavioral change (Loveys et al., 2023a).

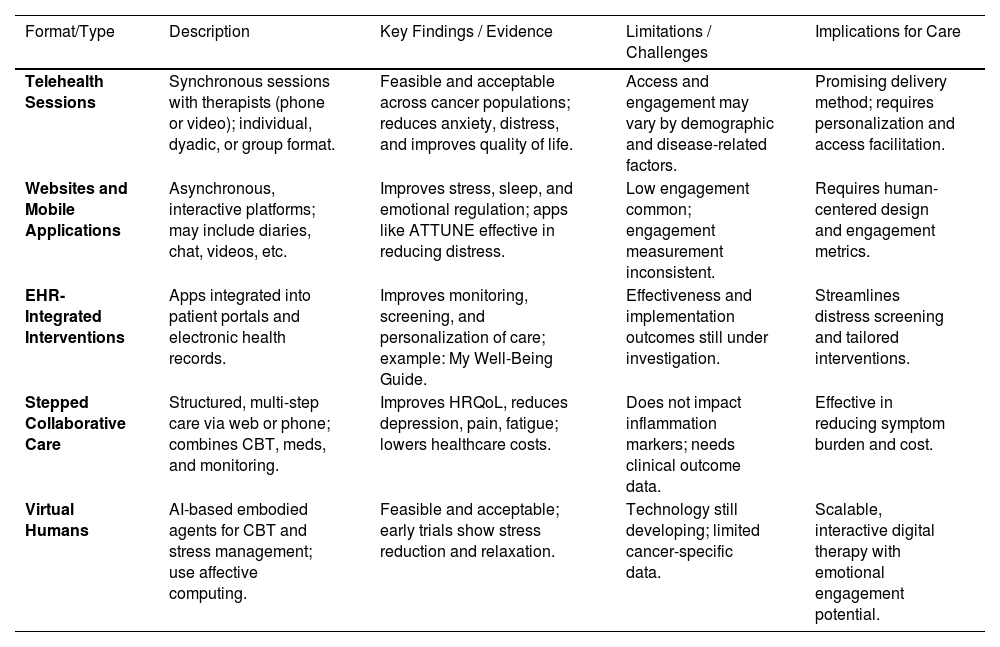

Summary of remotely-delivered interventions in cancerRemotely delivered stress management interventions (SMIs) offer key advantages, including scalability, healthcare cost savings, and broader accessibility. While increasing evidence supports their efficacy in improving health literacy and stress management skills, research on their effects on biobehavioral processes and clinical health outcomes in cancer patients remains limited. Preliminary evidence from RCTs suggests that teletherapist-led CBSM interventions can modulate immune system functioning in breast cancer patients, yet their effects on long-term clinical outcomes are still unknown (Antoni et al., 2022). No studies to date have assessed the impact of mobile apps or VH-based SMIs on biobehavioral processes or clinical outcomes (Antoni et al., 2022). Moving forward, comparative effectiveness trials are needed to assess the cost-benefits of various remote delivery methods compared to traditional face-to-face (F2F) approaches. Additionally, research should expand its focus beyond psychological adaptation to include biobehavioral and clinical health outcomes across diverse cancer populations. Future research should explore strategies to optimize adherence and personalize interventions based on patient needs. Ultimately, the optimal balance between efficacy and scalability may involve a hybrid approach, combining brief teletherapist- or VH-guided training for initial stress management skills with ongoing mobile app-based training, monitoring and reinforcement to help patients apply techniques to real-world stressors throughout cancer treatment and survivorship. Given the breadth of technology-based approaches currently under investigation, Table 4 summarizes the key intervention formats, delivery modalities, and emerging evidence supporting their use in psycho-oncology.

Technology-enhanced and remote interventions in cancer care.

HRQoL, Health Related Quality of Life; CBT, Cognitive Behavior Therapy; HER, Eletronic Health Records.

This article explored the complex interplay between psychological stress and cancer progression, emphasizing the dynamic and bidirectional communication between brain and body systems. Cancer patients frequently endure significant psychological distress, which can adversely affect treatment outcomes and survival rates. Chronic stress activates neuroendocrine pathways (e.g., the SNS and HPA axis) and leads to immune dysregulation, fostering inflammation (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α) and tumor growth through mechanisms such as the Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity (CTRA). Biobehavioral mechanisms matter: stress-induced inflammation (e.g., CTRA gene expression) and neural alterations can contribute to disease progression, underscoring the importance of integrated psychobiological approaches in cancer care.

Neuroimaging studies show that stress-related changes in brain regions involved in emotional regulation (e.g., prefrontal cortex, insula) are linked to poorer adjustment. However, psychosocial interventions such as Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management (CBSM) demonstrate promising effects in improving emotional resilience and modulating biological stress responses. Social determinants—like neighborhood disadvantage and low social support—can amplify stress-related health disparities. Conversely, strong social support and evidence-based stress management may buffer these effects. Although CBSM interventions can enhance resilience, reduce stress biomarkers, and potentially improve survival, their accessibility remains limited. We reviewed scalable, technology-enhanced interventions (e.g., telehealth, mobile applications, and virtual humans), which hold promise for addressing these limitations. Digital tools show promise, but their sustained engagement and long-term impact still require refinement.

To move the field forward we further develop a multilevel and integrative framework from what we have previously proposed to explain the links between psychological distress and cancer-related outcomes. This evolving updated model builds upon our earlier work by integrating insights from psychoneuroimmunology, biobehavioral oncology, cognitive neuroscience, and molecular cancer biology. Future research should incorporate cutting-edge methodologies—such as neuroimaging, transcriptomic profiling (e.g., CTRA), and real-time digital phenotyping—to uncover how stress affects immune function, tumor biology, and clinical outcomes.

Clarifying these brain-body pathways will enable the development of more precise, theory-driven interventions—including CBSM, mindfulness-based therapies, and AI-enhanced digital tools—targeting key processes such as SNS activation, HPA axis dysregulation and inflammation. The integration of digital phenotyping (e.g., smartphones, wearables, ecological momentary assessment methodology) (Insel, 2017; Jenciūtė et al., 2023) into psycho-oncology studies will allow for the capture of real-time, high-resolution characterization of patients’ behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and physiological patterns using data collected passively and actively from digital devices (e.g., smartphones, wearables). This approach offers an ecologically valid way to monitor cancer patients’ psychological and physical well-being outside clinical settings, capturing dynamic fluctuations in stress, mood, sleep, physical activity, and social interaction throughout the cancer experience, paving the way for personalized interventions and just-in-time adaptive interventions (Nahum-Shani et al., 2018). These precision approaches may not only reduce distress but also interrupt biological pathways linked to tumor progression, ultimately improving both survival and quality of life.

Translating these insights into real-world clinical impact will require coordinated efforts among researchers, clinicians, and policymakers. Priorities include: validating scalable digital interventions across diverse patient populations; integrating biomarker-informed stress management into standard oncology care; and addressing disparities by tailoring interventions for high-risk groups (e.g., individuals in underserved communities). To translate these findings into actionable improvements in cancer care, several key strategies should be implemented. First, routine psychosocial screening should become an integral part of standard oncology workflows. By systematically monitoring distress, healthcare providers can identify high-risk patients early and intervene before psychological symptoms escalate or interfere with treatment adherence. Second, it is essential to prioritize evidence-based stress management interventions (SMIs)—particularly those grounded in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). These interventions have demonstrated efficacy in reducing anxiety and depression among cancer patients (Antoni et al., 2023). When possible, delivering them through blended models—which combine human support with digital tools—can enhance accessibility, personalization, and engagement. Finally, addressing health disparities must be a central focus. Patients from low-income or socially disadvantaged backgrounds often face greater psychological burdens and barriers to care. Community-partnered approaches that are culturally sensitive and tailored to the needs of these populations can help bridge the gap and ensure more equitable access to psychosocial support.

Psychosocial oncology care is increasingly recognized as a human right and a critical component of high-quality cancer treatment. In this review, we have highlighted current scientific evidence demonstrating the complex, bidirectional interactions between psychological distress and biological processes in cancer. These mind–body dynamics not only contribute to emotional suffering but may also influence disease progression and survival. Psycho-oncological interventions play a pivotal role in interrupting these negative pathways, transforming them into opportunities for improved adaptation, resilience, and ultimately, better clinical outcomes. Fig. 1 presents the integrative model proposed and outlines key targets for future intervention and research in this field.

This integrative framework illustrates how psychosocial distress—shaped by individual, social, and contextual factors—influences cancer outcomes through central nervous system (CNS) mechanisms and biobehavioral processes. Stress-related dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, sympathetic nervous system (SNS), and immune system contributes to tumor progression and adverse clinical outcomes. Mediating variables include alterations in brain regions involved in emotion regulation and inflammatory signaling pathways. The model highlights multiple levels of intervention, including evidence-based stress management interventions (e.g., Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management, CBSM), pharmacologic strategies (e.g., beta-blockade), lifestyle approaches (e.g., anti-inflammatory diets, exercise), and digital health tools (e.g., mobile apps, virtual humans, and just-in-time adaptive interventions). Preventive strategies are organized by risk level, encompassing primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention efforts.

Joaquim C. Reis and Luzia Travado declare no competing interests.

Michael H. Antoni is funded by grants from the NIH (R01CA206456, UG3 CA260317, R61 CA263335, R37 CA255875), PCORI (AD-2020C3-21171), the Florida Breast Cancer Foundation, and a Cancer Center Support Grant (1P30CA240139-01).