Stress promotes affective, neural, endocrine, and immune responses. The glymphatic system, essential for waste clearance and immune homeostasis, protects the brain against adverse neurobiological changes. However, it remains unclear how the glymphatic system changes during acute stress, coordinates with multi-level stress responses, and relates to psychological resilience in humans.

MethodsWe recruited 84 healthy middle-aged adults (mean age 29.26 ± 2.91, 50 males) without major physical, neurological, or psychological conditions. Glymphatic system function was assessed via the coupling between global blood-oxygen-level-dependent and cerebrospinal fluid signals (gBOLD-CSF coupling) before, immediately after, and 60 min after the Montreal Imaging Stress Task. Mood states, neural responses (BOLD signal changes), acute and awakening cortisol responses, and psychological resilience (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale) were measured. We compared gBOLD-CSF coupling changes over time using repeated-measures ANOVA, and investigated their associations with affective, neural, endocrine responses, and resilience with linear models and network analysis.

ResultsgBOLD-CSF coupling was stronger at baseline and after recovery compared to immediately after stress. Changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling were associated with stress-related negative affect and prefrontal neural response. The cortisol response to acute stress was related to gBOLD-CSF coupling response to stress, depending on the level of the cortisol awakening response. The glymphatic system emerged as a central mediator of multi-organ stress response. Finally, post- to pre-stress changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling were associated with psychological resilience.

ConclusionsThe glymphatic system transiently fluctuates during acute stress, synergizing with affective, neural, and endocrine networks, playing significant roles in stress response and psychological resilience.

Perceived stress (stress) is a common mental health challenge worldwide. Acute stress triggers a fight-or-flight response (Lupien et al., 2009), involving changes in mood states (Giles et al., 2014), disturbances in prefrontal cortex activities (Elbau et al., 2018; Berretz et al., 2021), activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the release of stress-related hormones (Arnsten, 2015; Charmandari et al., 2005), and immune activation (Benson et al., 2009; Marsland et al., 2017). Chronic stress, resulting from prolonged acute stress, increases the mortality rates (Prior et al., 2016), elevates the risk of chronic diseases (Hackett & Steptoe, 2017; Kivimäki & Steptoe, 2018), and depressive episodes (Stroud et al., 2008). Yet, psychological resilience is a process that protects against the adverse effects of stress (Davydov et al., 2010; Watanabe & Takeda, 2022). Higher psychological resilience was associated with reduced mortality risk and multiple positive health outcomes (Musich et al., 2022; A. Zhang et al., 2024).

Located in the perivascular space, the glymphatic system plays a crucial role in the brain's immune system, facilitating efficient substance exchange with the aid of aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channels on the astrocyte endfeet (Lohela et al., 2022), and has also been implicated in modulating systemic inflammation (Lin et al., 2025; Xia et al., 2025). The coupling between the global blood-oxygen-level-dependent signal and cerebrospinal fluid signal (gBOLD-CSF coupling) is a non-invasive way to assess the glymphatic system in humans (Fultz et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021). This metric captures the coordination between cerebrospinal fluid oscillations and cortical hemodynamic responses indicated by the large-scale, slow oscillation in the global BOLD signal. It is hypothesized that this coupling reflects the underlying neural and physiological processes that drive glymphatic clearance (Mestre et al., 2018; Yamada et al., 2013). Reduced gBOLD-CSF coupling was observed in patients with neurodegenerative diseases and affective disorders compared to healthy controls (Qian et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024), and was significantly associated with cortical thinning and neuropathological protein accumulation (Han et al., 2024a). Nevertheless, there is currently insufficient understanding about the role of the glymphatic system in the stress response in the context of healthy individuals to elucidate how it effectively buffers against the stress-related adverse neurobiological effects to support mental well-being (Rasmussen et al., 2018).

The plasticity of neural and immune responses during stress is a critical physiological feature that underpins psychological resilience. Specifically, psychosocial stress temporally impeded efficient prefrontal processing, but this impact was reversible (Liston et al., 2009). Meanwhile, social status altered leukocyte composition and impacted gene expression in immune cells in a reversible and plastic manner, suggesting the intrinsic plasticity of the immune system (Snyder-Mackler et al., 2016). If the glymphatic system is essential for immune functioning that maintains an optimal microenvironment for neurons, acute stress may initially disrupt the functioning of the glymphatic system, which may recover after successful stress coping. We propose that these reversible functional changes in the glymphatic system during stress may serve as an essential immune basis for psychological resilience, a compelling association that has yet to be fully investigated.

Multi-system coordination is another key feature in stress response and resilience (Hodes et al., 2014; Ménard et al., 2017), with which the glymphatic system may potentially interact. In normal conditions, stress not only exerts mood changes, but also activates the HPA axis to release glucocorticoid hormone, induces neural changes in frontal and temporal lobes and subcortical structures (Berretz et al., 2021; Noack et al., 2019), and activates immune cells (Dhabhar, 2009a, 2009b; Padgett & Glaser, 2003), facilitating the body to adapt to external challenges (Chen et al., 2017; McEwen, 2004; McInnis et al., 2015). As a significant immunological component and neural correlates, the glymphatic system and its dynamic response may coordinate with these bodily systems to form an integrated multi-organ network that copes with stress and supports adaptive recovery following adversity, ultimately contributing to psychological resilience. For example, glucocorticoids exhibit immunomodulatory effects by regulating the immune system (Cain & Cidlowski, 2017). This signalling pathway may modulate the glymphatic system under stress, potentially through the interactions indexed by the cortisol awakening response (CAR), a major biomarker of basal HPA axis activity (Boehringer et al., 2015). In specific, animal studies discovered that blocking corticosteroid signalling at the choroid plexus—a critical hub for immune-brain communication—under stress promotes stress coping and alleviates behavioral symptoms that emerge after stress exposure (Kertser et al., 2019). Stress-induced prolonged glucocorticoid signalling impaired the AQP4 channels on astrocytes and AQP4-dependent glymphatic transport in mice (Wei et al., 2019). However, empirical evidence validating the participation of the glymphatic system in this multi-system coordination during stress response and resilience in humans is scarce.

Although evidence suggests the protective role of the glymphatic system in psychological well-being and potential coordination with affective, neurobiological, and endocrine stress responses, critical research gaps remain. The impact of stress on the glymphatic system, the interrelationship between the glymphatic system and multi-level stress responses, and the relationship between these stress-related changes and psychological resilience in humans are still poorly understood. In this study, we first hypothesized that the gBOLD-CSF coupling strength, which reflects the function of the glymphatic system, would be temporarily weakened during acute stress and subsequently recover. Second, we hypothesized that stress-related changes in the glymphatic system would coordinate with multi-level stress response. Specifically, larger changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling would be associated with more pronounced mood changes over time, increased cortisol release, and significant alterations in neural activity within stress-related brain regions during acute stress. Considering the immunomodulatory effect of glucocorticoids, we speculated that the cortisol response to acute stress and cortisol awakening responses would have an interactive effect on the stress-related changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling. Third, given that plasticity in the glymphatic system response is essential for adaptive stress coping, we speculated that a larger change in gBOLD-CSF coupling would be associated with better psychological resilience and a greater cortisol awakening response. Finally, we explored the multivariate relationship between the complex multi-organ response network and psychological resilience to provide more holistic insights. Addressing these knowledge gaps will deepen our understanding of the adaptive changes in the glymphatic system and multi-organ system in supporting stress response and resilience in healthy conditions, thereby elucidating the role of the glymphatic system in mental health and facilitating the development of preventive and intervention strategies targeting this system to promote brain and psychological health.

MethodParticipantsThe ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong. The participants were recruited through posters, printed advertisements, social media, and from the FAMILY Cohort – a participant registry of Hong Kong residents (Leung et al., 2017). Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) healthy adults aged 18-45, 2) normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing, 3) literacy level higher than grade 2, 4) no history of major physical or psychiatric disorders, no substance use, and no heavy smoking (defined as > 20 cigarettes per day), 5) not pregnant, breastfeeding, or using oral contraceptives, and 6) not having any medication or under treatment within two weeks before the study that may affect the endocrine system. Trained research staff and students administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® Disorders—Clinician Version (First et al., 2016) either online or in person to exclude individuals who met the diagnostic criteria for major psychological disorders (i.e., mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance-related and addictive disorders, feeding and eating disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder). The final sample included 84 participants aged 24 to 36 (M = 29.26, SD = 2.91), with 50 males. We obtained informed consent from all participants.

Tasks and proceduresThe Trier Social Stress Test (Allen et al., 2014; Kirschbaum et al., 1993) and the Montreal Imaging Stress Task (Dedovic et al., 2005) were administered to the participants to elicit cortisol and neural responses, respectively. They participated in the two tasks on different days, and most of them completed the TSST prior to the MIST. The average interval across the two experiments was 241 days (SD = 235), with a range of -101 to 814 days. Both tasks were conducted between 14:00 and 18:00. Debriefing was not provided to the participants until their second participation in the experiment was completed. Upon completion of each experiment, participants were thanked and compensated with cash for their time and travel.

Trier social stress test (TSST)Before the experiment, participants were instructed to (1) no eating or drinking within 1 h before the experiment, (2) avoid intense physical activity or teeth-brushing within two hours, (3) abstain from caffeine and smoking on the day of the experiment, and (4) no alcohol consumption in 24 h before the experiment.

Participants completed demographic forms upon arrival. They then rested for 30 min in a quiet room with neutral reading material to allow their cortisol levels to return to a resting state. After this rest period, participants completed the first Profile of Mood States (POMS) and provided the first saliva sample (Ta). They were then taken to another room for the TSST, which included three 5-minute sections: Anticipation/Preparation, Speech, and Mental Arithmetic. Dummy cameras and audio devices were installed in the room to enhance the realism of the scenario. To begin, participants were asked to imagine they would be interviewed for their ideal job and to prepare a 5-minute speech to a panel of examiners. In the subsequent Speech section, they delivered their speech to three judges dressed in lab coats whose facial expressions remained neutral. If the participant could not continue before time was up, the chief judge would ask prompt questions; otherwise, they kept silent till the end of the Speech section. In the final section, participants performed a mental arithmetic task, repeatedly subtracting 17 from 2,023, and had to start over whenever they made a mistake. Following the TSST, participants returned to the quiet room, where their second saliva sample (Tb) and second POMS were collected. The third (Tc) to sixth (Tf) saliva samples were collected at a 20-minute interval. The third measurement of POMS was conducted 30 min after TSST. The 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10; Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007) was administered after the collection of the fourth saliva sample (Td).

Montreal imaging stress task (MIST)The Montreal Imaging Stress Task (MIST) is a widely used laboratory paradigm to induce acute stress in participants (Dedovic et al., 2005). In this study, we employed a modified MIST (Figure S1A), consisting of two repeated sessions in a block design, each lasting for approximately seven minutes. Each session consisted of six 40-second blocks with three conditions (Control, No-stress, and Stress), each repeated twice. Participants were instructed to solve an arithmetic problem and select the answer using an on-screen dial with a button box, with the directive to respond as quickly and accurately as possible.

During the Control condition, participants were provided with the answers directly and could input them without a time limit. In the No-stress condition, they solved the arithmetic and selected the calculated answer without a time limit. Participants were informed that their responses would not be recorded by the computer to minimize their stress. In the Stress condition, participants had to solve arithmetic questions within a set time limit, indicated by a time-progressive colour bar on the screen. They were informed that their accuracy was recorded. An algorithm was employed in this condition to adjust the task difficulty and time limits, aiming to maintain a correct response rate of 40-60 %. Social stress was further introduced in the Stress condition by informing participants that they were competing against a real participant in terms of speed and accuracy, with pre-recorded performance data displayed at the top of the screen. They were encouraged to match or exceed the competitor's results, unaware that the competitor was actually an algorithm-controlled indicator designed to outperform them consistently before the end of the block. After session 1, the experimenter would provide scripted verbal negative feedback regarding the participants' previous performance. This feedback included the following messages: 1) informing participants that their performance did not meet expectations; 2) emphasizing the need to perform at least as well as, if not better than, their competitor; and 3) warning that if their performance in the next session remained poor, their data might not be considered included for the study, thus imposing additional social stress.

Three resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) scanning sessions were performed before the MIST task (T1), immediately after the MIST task (T2), and after a 60-minute resting period out of the scanner (T3; Figure S1B).

Participants completed their first POMS assessment (T1) before entering the scanner. The second POMS (T2) was administered immediately after participants exited the scanner following the MIST and resting-state scanning. The third POMS (T3) was completed after the 60-minute rest.

The TSST and MIST demonstrated good consistency in inducing stress-associated mood changes, as verified by the significant association in the changes in both positive (unstandardized estimate = 0.336, p < 0.001) and negative affect (unstandardized estimate = 0.464, p < 0.001) across time between TSST and MIST (Table S1 and Table S2). Both experimental tasks were conducted in the afternoon to minimize the individual differences in diurnal cortisol variations.

MRI acquisition and analysisImaging acquisition parametersAll imaging data were collected using a 3T Prisma Scanner (Siemens Healthineers) with a 64-channel head coil, and participants were scanned in the head-first supine position. A mirror was attached at the top of the head coil to reflect a computer screen behind the scanner. A high-resolution T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) image was acquired as anatomical reference at the beginning of the scanning session (repetition time [TR] = 2500 ms, echo time [TE] = 2.22 ms, inversion time = 1120 ms, flip angle = 8°, field of view [FOV] = 256×240×166.4 mm, voxel size = 0.8×0.8×0.8 mm). The task-based fMRI of the BOLD responses to each MIST run were measured with multiband gradient-echo echoplanar pulse sequence (475 volumes, TR = 800 ms, TE = 37 ms, flip angle = 52°, FOV = 208×208×144 mm, matrix size = 104×104, slice thickness = 2 mm, multiband acceleration factor = 8). The same imaging sequence was used for the rs-fMRI scans with 750 volumes in each session.

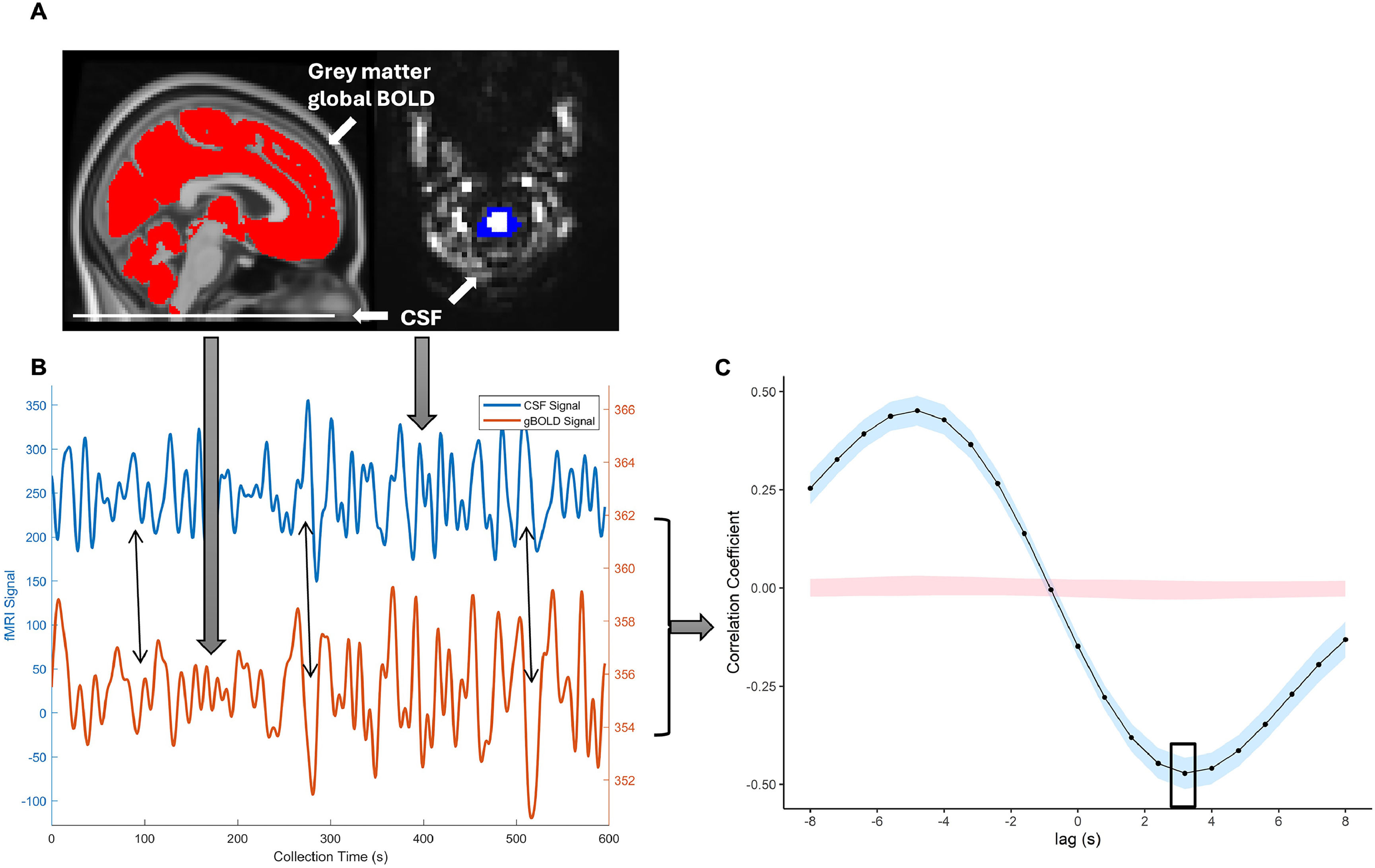

gBOLD-CSF coupling quantificationgBOLD-CSF coupling (Jiang et al., 2023) was derived from rs-fMRI data after preprocessing, signal extraction, and coupling strength calculation using DPABI (http://rfmri.org/DPABI; Yan et al., 2016) and MATLAB (The Mathworks, Natick MA, USA; Fig. 1). Analyses were performed in the individual’s original space. For CSF signal extraction, rs-fMRI preprocessing included removing the first 5 time points, slice-timing correction, detrending, and band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz). The accurate motion correction estimation cannot be fully achieved for the edge slices where the CSF signal was extracted because tissue continuously moves in and out of the imaging volume (Fultz et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2023; Y. Zhang et al., 2024). The most inferior edge slice was selected to maximize CSF signal intensity, where CSF regions of interest (ROIs) were manually drawn to extract the average signal (Fig. 1A). For gBOLD signal extraction, preprocessing included removing the first 5 time points, slice-timing correction, head movement correction, detrending, band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz), and spatial smoothing (4 mm kernel). For each timepoint, the global BOLD signal was extracted from the average grey matter mask for the study sample. The gBOLD and CSF signals from one participant were plotted for demonstration (Fig. 1B).

Quantification of gBOLD-CSF coupling.

To quantify gBOLD-CSF coupling, the cross-correlation between the gBOLD and CSF signals was calculated at various time lags (-8 s to +8 s). Previous studies have shown that the negative peak of coupling strength typically occurs at a time lag of +2 to +4 seconds (Han et al., 2021; Y. Zhang et al., 2024). In this study, the negative peak was at a +3.2 s time lag (Fig. 1C), and the correlation coefficient at this lag was used to measure gBOLD-CSF coupling strength. The lag time for identifying this peak was consistent at three times. Considering the functioning of the glymphatic system resulting in a negative correlation between global BOLD and CSF signals with a slight time lag, a higher value of gBOLD-CSF coupling indicates a weaker strength of the coupling, thus reflecting a worse functional status of the glymphatic system. Previous research reported good test-retest reliability of the gBOLD-CSF coupling in healthy middle-aged adults with normal sleep (Zhao et al., 2025).

The levels of gBOLD-CSF coupling were quantified before the MIST task (T1), immediately after the MIST task (T2), and after a 60-minute resting period out of the scanner (T3). The changes in its level were quantified as the general changes over three time points, post- and pre-stress change, or change from recovery to baseline.

Task-based analysisTask-based fMRI data were pre-processed in SPM12 (Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging, London, UK) in MATLAB (The Mathworks, Natick MA, USA) and DPABI 5.3. For the MIST task fMRI data, the first five volumes of scans were discarded for signal equilibrium and participants’ adaptation to scanner noise. The remaining images were then corrected for slice acquisition timing and realigned for head motion. Nuisance regressors, including mean signals from white matter, cerebral-spinal fluid signals, and global signals, as well as the Friston 24-motion parameters (six motion parameters, six motion derivatives, and their squares), were regressed out from the data. Stress and No-stress conditions in session 2 were defined as separate regressors in the general linear model (GLM) and convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function in SPM12. A high-pass filter (cutoff: 1/128 Hz) was applied to the data. Serial correlations were addressed using a first-order autoregressive model [AR(1)]. We computed the contrast maps at the individual-subject level to identify regions with increased activation during the Stress condition compared to the No-stress condition. The identified neural correlates of stress are consistent with the literature (Table S3, Supplementary Materials). We proceed to group-level multiple regression analyses based on the individual-level contrast images with changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling (post- and pre-stress; and from recovery to baseline) as an independent variable and age and sex as covariates. Significant clusters were determined at a family-wise error (FWE)-corrected threshold of p < 0.05. Finally, the estimated beta coefficients of significant clusters were extracted to characterize activation patterns.

QuestionnairesProfile of mood states (POMS)The POMS measured five negative emotional states (tension, anger, fatigue, confusion and depression) and two positive emotional states (vigor and esteem; Grove & Prapavessis, 1992). Sample item for each state includes “uneasy” for tension, “annoyed” for anger, “exhausted” for fatigue, “uncertain about things” for confusion, “hopeless” for depression, “energetic” for vigor, and “proud” for esteem. Participants rated each item on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The average internal consistency across the subscales was 0.942 (Cheung & Lam, 2005). To evaluate positive and negative emotional states, the total scores for all items in each domain were summed. Cronbach’s alphas for positive and negative affect subscales ranged from 0.863 to 0.962 for TSST and 0.902 to 0.964 for MIST.

Connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC-10)The CD-RISC-10 is a shortened version of the original 25-item CD-RISC (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007) designed to assess trait psychological resilience. The Chinese version of CD-RISC-10 has demonstrated good reliability and validity (She et al., 2020). The responses include 0 (“not true at all”) to 4 (“true nearly all of the time”). Responses are scored from 0 ("not true at all") to 4 ("true nearly all of the time"), with total scores ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate greater resilience in effectively coping with challenging situations. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.942 in the current administration.

Saliva sample collection and assaysSalivary cortisol samples were collected using the Salivette Cortisol Kit (Sarstedt, cat. no. 51.1534.500). Participants chewed a cotton swab for 45 s and held it under their tongue for 15 s, allowing the cotton swab to absorb the saliva, then placed the swab into the Salivette tube. Samples were processed onsite by centrifugation at 3000 x g for 5 min and sent to the Centre for PanorOmic Sciences, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis to quantify cortisol levels (Raff & Phillips, 2019).

Cortisol response to acute stressSalivary cortisol was collected at six time points before and after the TSST, as introduced in the 2.2.1 Trier Social Stress Test (TSST). The cortisol response to acute stress was quantified by the Area Under the Curve incremental (AUCi) from levels Ta to Tf.

Cortisol awakening responseParticipants provided the saliva samples the day before they participated in the MIST. Prior to any sampling, participants were instructed to read the user manual provided by the manufacturer. Saliva was collected at five time points: before sleeping, immediately after waking, and at 15, 30, and 60 min after waking. Participants were instructed to: 1) abstain from caffeine (such as coffee) and alcohol for 24 h before the first saliva sample, 2) refrain from eating or drinking for one hour before each sampling, and 3) avoid toothbrushing, chewing gum, smoking, flossing, or using any mint-flavoured products for one hour before each sampling. Samples were stored in sealed tubes in the fridge at 4 °C and transported to the experiment site in an isothermal bag with an ice pack.

Cortisol awakening response was quantified by the AUCi across the five time points.

Statistical analysisFirst, to investigate the effect of acute stress on the functioning of the glymphatic system, we conducted repeated measures ANOVA and post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction among the gBOLD-CSF coupling levels at baseline, after stress and in recovery. Repeated measures ANCOVA was further conducted to exclude the effect of age and sex as covariates.

Second, we examined the associations between the glymphatic system and multi-level stress responses. Linear mixed models were used to examine the associations between mood states and the gBOLD-CSF coupling over time (i.e., baseline, post-stress, recovery). The models included gBOLD-CSF coupling as the dependent variable and person-centered mood states as the fixed effect, and controlled for age, sex and average score as between-person fixed effects and mood states and participant as random effects. Models were estimated using the “GAMLj3” module in jamovi, which is based on the “lmer” function in R. The relationship between neural responses and the glymphatic system was analysed by group-level multiple regression analyses with age and sex as covariates in SPM12 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK) as described in 2.3.4 Task-based analysis. The response in the glymphatic system was measured by examining the gBOLD-CSF coupling level immediately after stress while controlling for baseline. The recovery of the glymphatic system was measured by examining the gBOLD-CSF coupling level after recovery while controlling for baseline or post-stress levels. Similarly, the direct relationship between cortisol response and the glymphatic system was analysed by multiple linear regression, with 5000 times bootstrapping, while controlling for age and sex. Moreover, the immunomodulatory effect of the glucocorticoid, the interaction between the cortisol response to acute stress and cortisol awakening responses in predicting the response of the glymphatic system, was examined by moderation analysis with Bootstrapping technique at 5,000 iterations (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) in PROCESS macro 4.0 (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017). Simple slope test(s) on significant interaction effect(s) would be conducted to decipher the association between cortisol response to acute stress and the glymphatic system functioning with Johnson-Neyman method for estimating the significant regions. Effects were considered significant if the bias-corrected and accelerated (Bca) 95 % confidence intervals (CI) did not include zero.

Third, we used multiple linear regression to examine the association between the glymphatic system immediately after stress and psychological resilience, when controlling for age and sex, and baseline levels. The association between changes in the glymphatic system and cortisol awakening response was also examined by multiple linear regression with the same set of covariates.

Finally, the comprehensive association between multi-level responses and psychological resilience was tested through a network analysis in RStudio with packages of “qgraph” (Epskamp et al., 2012) and “bootnet” (Epskamp et al., 2018). We built the partial correlation network to examine the inter-relationship between the acute responses of the glymphatic system, cortisol response, positive and negative affect response, and neural response, with cortisol awakening response and psychological resilience. Affect response and the gBOLD-CSF coupling changes were quantified by subtracting baseline levels from their levels after stress. The neural response was quantified with the beta value extracted from the clusters showing significant activation differences between Stress and No-stress conditions. We examined the betweenness, closeness, and strength of each node thus identifying the most influential nodes. Network stability was assessed using nonparametric bootstrapping (5,000 bootstrap samples) to compute 95 % CIs for edge weights and centrality measures. Case-dropping bootstrapping was used to evaluate the robustness of centrality indices to subset resampling.

All the statistical analyses were conducted in R Studio, Jamovi, and SPSS. The visualization for MRI was performed in mricroGL (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricrogl/). The plots were produced in R Studio with packages of “ggplot2”, “ggpubr”, and “interactions”. Age and sex were included as covariates in all analyses due to their significant associations with the variables of interest (Gonçalves et al., 2025; Han et al., 2024b; Luine et al., 2007; Novais et al., 2016; Roelfsema et al., 2017).

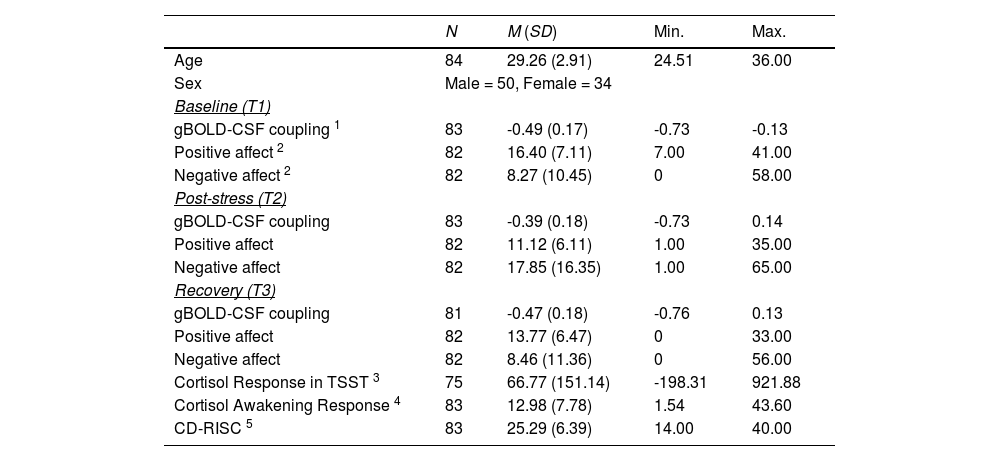

ResultsDescriptive statistics of the study variables are summarized in Table 1. gBOLD-CSF coupling at baseline was positively correlated with its level after stress (r = 0.59, p < 0.001) and the level after recovery (r = 0.53, p < 0.001). gBOLD-CSF couplings after stress and recovery were also associated with each other (r = 0.41, p < 0.001).

Descriptive information about demographics, gBOLD-CSF coupling, affect changes, cortisol responses, and CD-RISC score.

| N | M (SD) | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 84 | 29.26 (2.91) | 24.51 | 36.00 |

| Sex | Male = 50, Female = 34 | |||

| Baseline (T1) | ||||

| gBOLD-CSF coupling 1 | 83 | -0.49 (0.17) | -0.73 | -0.13 |

| Positive affect 2 | 82 | 16.40 (7.11) | 7.00 | 41.00 |

| Negative affect 2 | 82 | 8.27 (10.45) | 0 | 58.00 |

| Post-stress (T2) | ||||

| gBOLD-CSF coupling | 83 | -0.39 (0.18) | -0.73 | 0.14 |

| Positive affect | 82 | 11.12 (6.11) | 1.00 | 35.00 |

| Negative affect | 82 | 17.85 (16.35) | 1.00 | 65.00 |

| Recovery (T3) | ||||

| gBOLD-CSF coupling | 81 | -0.47 (0.18) | -0.76 | 0.13 |

| Positive affect | 82 | 13.77 (6.47) | 0 | 33.00 |

| Negative affect | 82 | 8.46 (11.36) | 0 | 56.00 |

| Cortisol Response in TSST 3 | 75 | 66.77 (151.14) | -198.31 | 921.88 |

| Cortisol Awakening Response 4 | 83 | 12.98 (7.78) | 1.54 | 43.60 |

| CD-RISC 5 | 83 | 25.29 (6.39) | 14.00 | 40.00 |

Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant difference in the level of gBOLD-CSF coupling across time (F(2,160) = 14.10, p < 0.001; Fig. 2). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with the Bonferroni correction demonstrated that its strength was stronger at baseline (M = - 0.49, SD = 0.17) compared to immediately after stress exposure (M = - 0.39, SD = 0.18; p < 0.0001). Moreover, the post-stress coupling strength was weaker than after recovery (M = - 0.47, SD = 0.18, p = 0.001). No significant difference was observed between baseline and post-recovery levels (p = 1). This effect remained significant after controlling for age and sex in a repeated-measures ANCOVA (F(2,156) = 3.25, p = 0.041), and remained significant in post-hoc analysis.

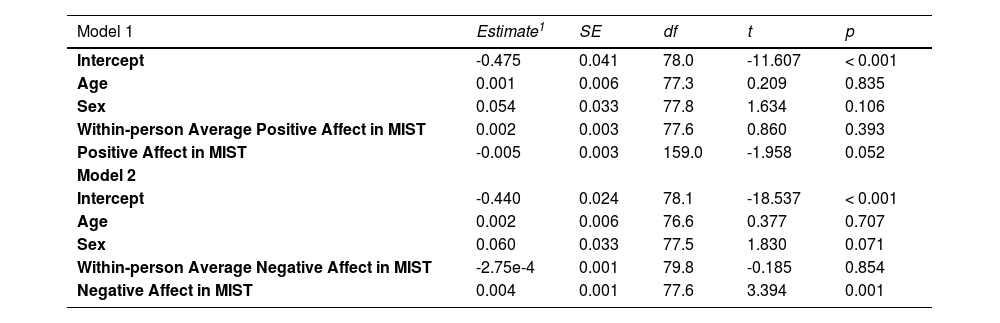

The association between changes in mood state and changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling during stressWe further investigated the relationship between the stress-induced changes in the glymphatic system and stress-associated mood alterations in MIST. The positive affect was significantly different during the acute stress, F(2,162) = 55.65, p < 0.001 (Figure S2A), and the same for the negative affect, F(2,119.81) = 51.80, p < 0.001 (Figure S2B). The linear mixed model revealed a marginally significant association between positive affect and gBOLD-CSF coupling over time (unstandardized estimate = -0.005, p = 0.052), including random effects for participant and positive affect and controlling for age, sex and average positive affect as fixed effects (Table 2). The relationship between negative affect and gBOLD-CSF coupling across time was significant (unstandardized estimate = 0.004, p = 0.001, Table 2) with the same model settings.

Results of the linear mixed-effects model (fixed coefficients) examining the stress-related changes in positive affect, negative affect, and the gBOLD-CSF coupling during MIST.

| Model 1 | Estimate1 | SE | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.475 | 0.041 | 78.0 | -11.607 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.006 | 77.3 | 0.209 | 0.835 |

| Sex | 0.054 | 0.033 | 77.8 | 1.634 | 0.106 |

| Within-person Average Positive Affect in MIST | 0.002 | 0.003 | 77.6 | 0.860 | 0.393 |

| Positive Affect in MIST | -0.005 | 0.003 | 159.0 | -1.958 | 0.052 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Intercept | -0.440 | 0.024 | 78.1 | -18.537 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 0.002 | 0.006 | 76.6 | 0.377 | 0.707 |

| Sex | 0.060 | 0.033 | 77.5 | 1.830 | 0.071 |

| Within-person Average Negative Affect in MIST | -2.75e-4 | 0.001 | 79.8 | -0.185 | 0.854 |

| Negative Affect in MIST | 0.004 | 0.001 | 77.6 | 3.394 | 0.001 |

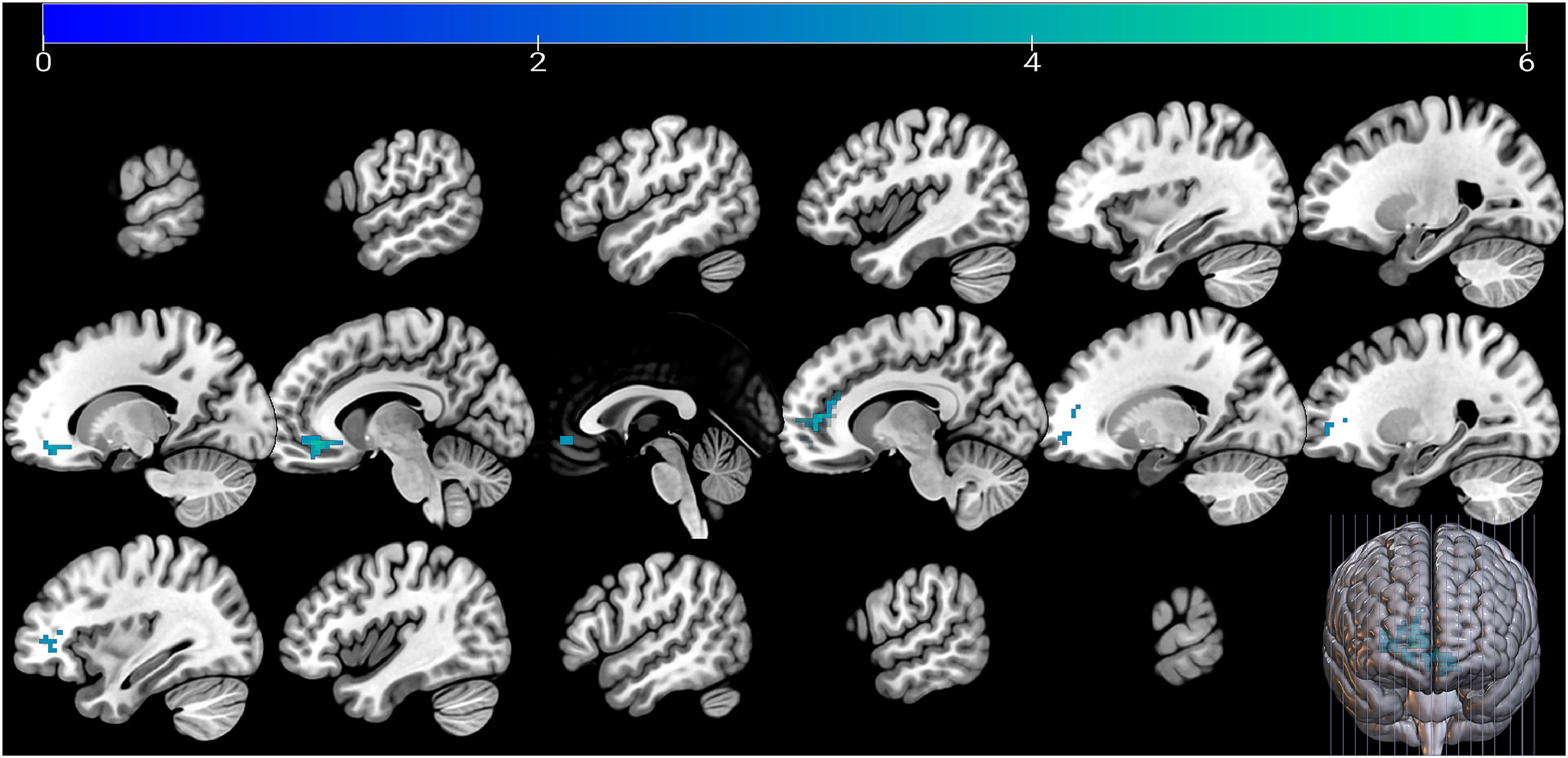

No significant voxel was observed regarding the post-stress change in gBOLD-CSF coupling after FWE correction, when controlling for baseline coupling values, age, and sex. Change in gBOLD-CSF coupling from recovery to baseline was negatively associated with the difference in neural activation between “Stress” and “No-stress” conditions in MIST task session 2 with extra social stress imposed, specifically in the left orbitofrontal (Brodmann Area 11) [-6, 39, -9] and the right anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC; Brodmann Area 10) [6, 57, 3]. This association was significant with FWE correction (p < 0.05 for cluster-level inference), with extent thresholds = 91 voxels (N = 83), while controlling for baseline level of gBOLD-CSF coupling, age, and sex (Fig. 3).

The significant neural activation was further associated with cortisol response. The beta value extracted from the above significant clusters was also associated with the cortisol response during TSST, unstandardized B = -0.002, Beta = -0.482, p < 0.001, 95 % CI = [-0.003, 0]. Covariates include age, sex, and time interval in days between TSST and MIST.

The modulatory role of glucocorticoids on the stress-related change in the glymphatic systemWe first applied multiple linear regression to examine the direct association between cortisol response induced by TSST and changes in the level of the glymphatic system (post- and pre-stress change, or change from recovery to baseline). No significant direct association was observed between cortisol response and changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling over time.

Next, we examined the hypothesized immunomodulatory effect of glucocorticoids on the glymphatic system, specifically, the interaction between the cortisol response to acute stress and cortisol awakening responses, which reflect long-term HPA axis functioning. We observed that the association between cortisol response, as reflected by the AUCi of cortisol levels in the TSST, and the gBOLD-CSF coupling level immediately after stress varied depending on the level of the cortisol awakening response (R-squared changes = 0.038, p = 0.029) when controlling for age and sex. No interaction effect was observed regarding the recovery of the glymphatic system. According to the estimation based on the Johnson-Neyman method, the association between cortisol response to acute stress and the gBOLD-CSF coupling became significantly positive (unstandardized B = 0.0004, p = 0.050, 95 % CI = [0, 0.0007]) when the AUCi of the cortisol awakening response was higher than 26.05 (Upper 8.22 %). However, the association was not significant when the AUCi of the cortisol awakening response was below this level until -4.10 (Figure S3).

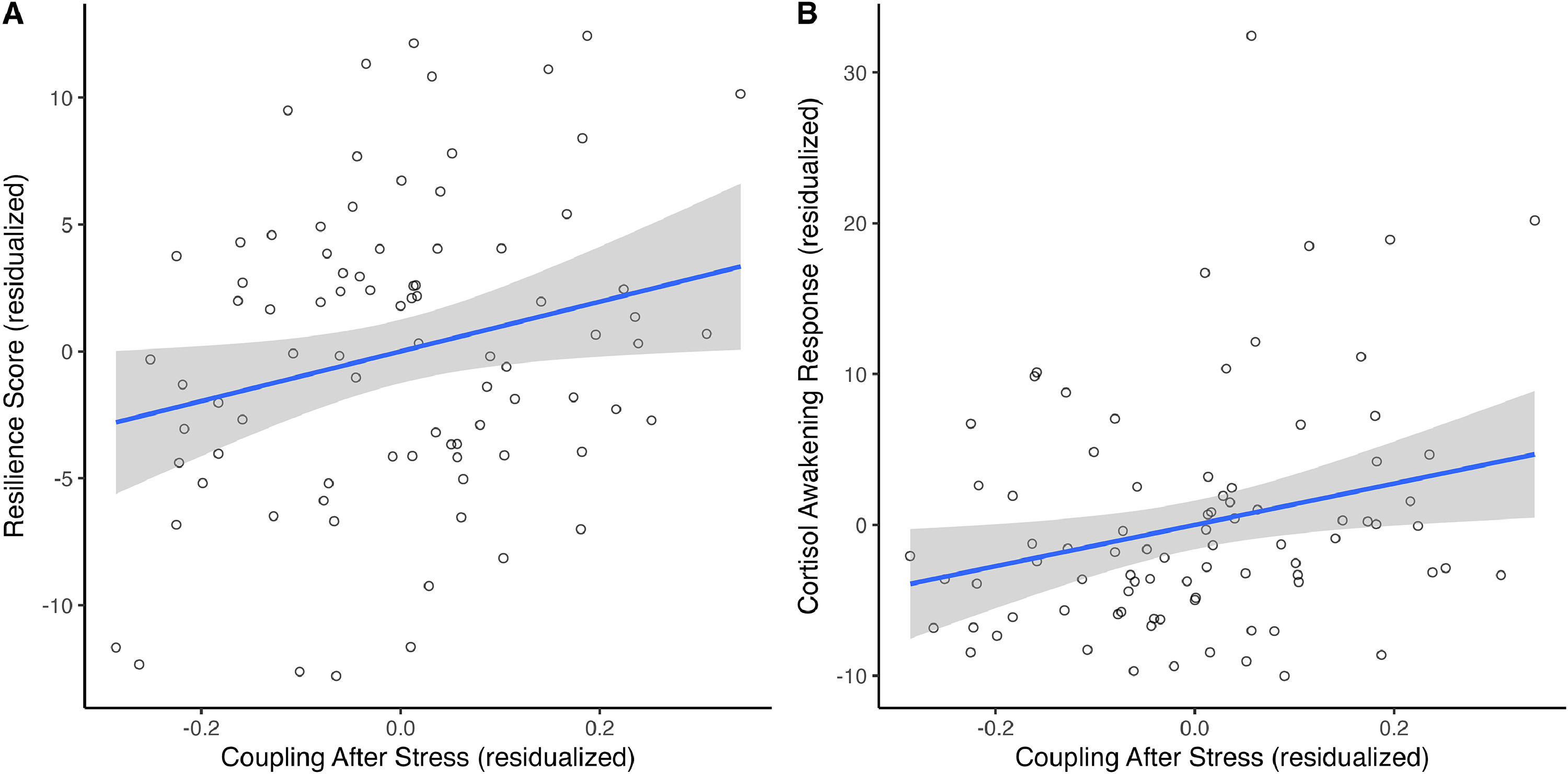

The association between stress-related changes in the glymphatic system and psychological resilienceThe post- and pre-stress change in gBOLD-CSF coupling was positively associated with the CD-RISC score reflecting trait resilience (unstandardized B = 10.188, Beta = 0.292, p = 0.029, bootstrapping 95 % CI = [1.688, 18.162]), when controlling for baseline glymphatic system level, age, and sex (Fig. 4A). No association was observed concerning the change in gBOLD-CSF coupling during the recovery.

Relationship between gBOLD-CSF coupling after stress and resilience (A) and the relationship between gBOLD-CSF coupling after stress and cortisol awakening response (B).

The post- and pre-stress change in gBOLD-CSF coupling was also positively associated with AUCi of cortisol awakening response on the day of MIST (unstandardized B = 13.670, Beta = 0.320, p = 0.023, bootstrapping 95 % CI = [2.650, 24.826]), when controlling for baseline glymphatic system level, age, and sex (Fig. 4B). No association was observed concerning the change in gBOLD-CSF coupling during the recovery. The AUCi of the cortisol awakening response was also significantly correlated with changes in positive affect during acute stress (Supplementary Materials S2).

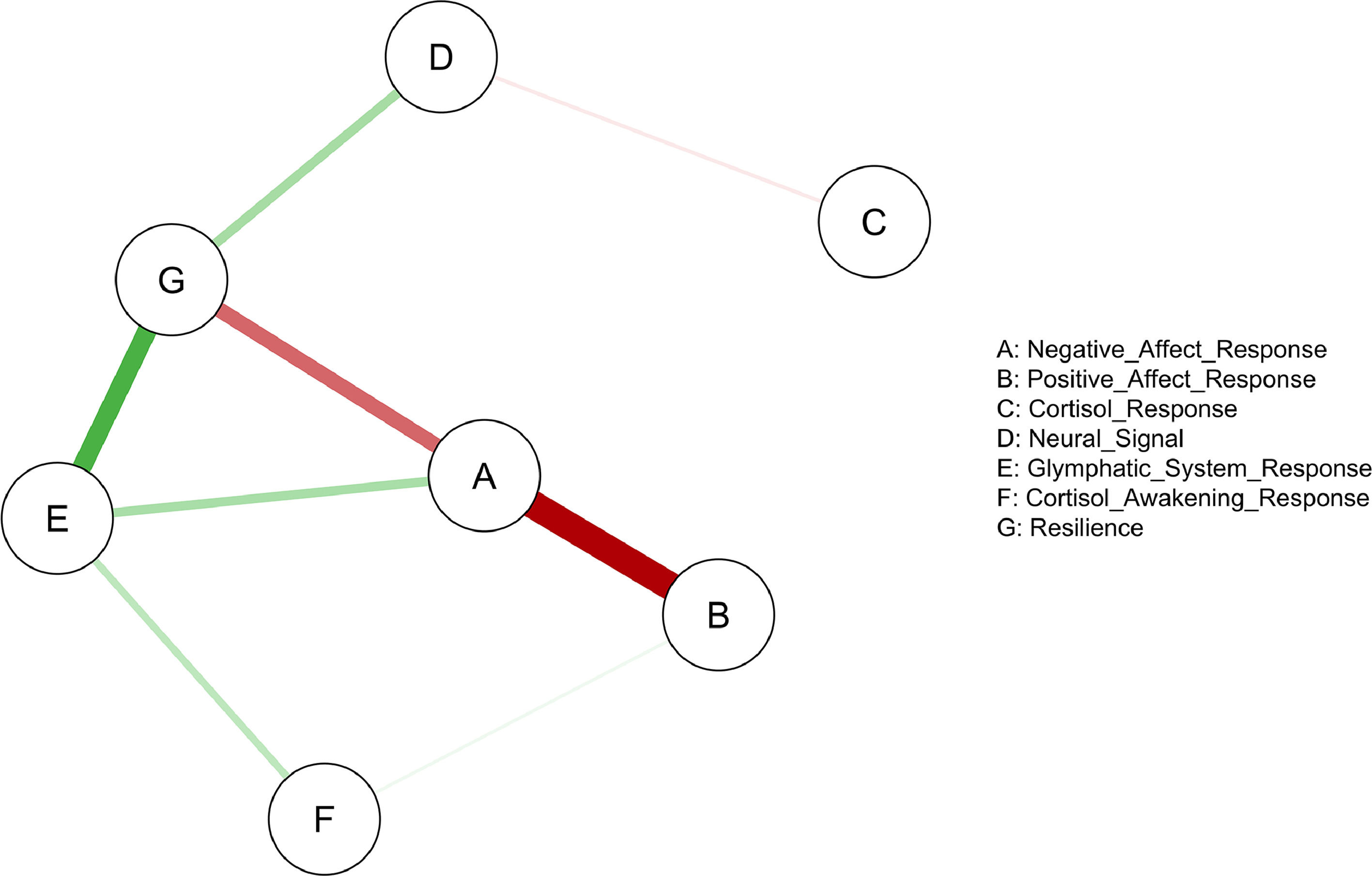

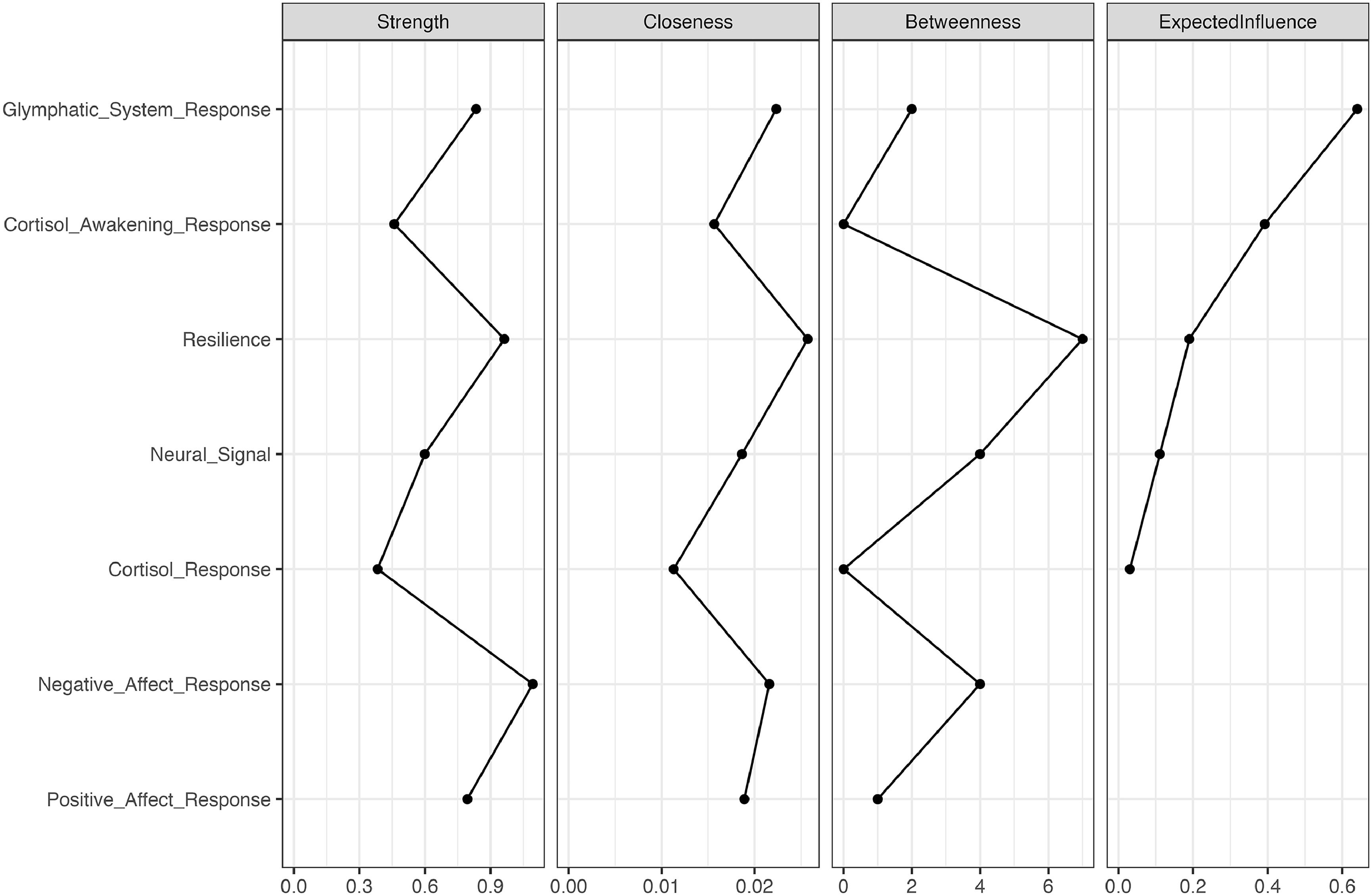

The relationship between multi-level stress responses and psychological resilienceWe examined the network association between multi-level stress-related changes, including post- and pre-stress changes in positive and negative affect, gBOLD-CSF coupling, and the stress-induced changes in cortisol and neural responses, cortisol awakening response, and psychological resilience. Network analysis revealed a significant network among 7 nodes (Fig. 5), comprising 8 edges with edge weight absolute strength thresholded over 0.1 with a density of 0.381. Edge weights ranged from -0.455 to 0.333. Centrality indices are plotted in Fig. 6.

Expected influence centrality identified the post- and pre-stress change in the gBOLD-CSF coupling as the most central node in the network (expected influence centrality = 0.640; see Figs. 5and6), showing positive connections with cortisol awakening response and post- and pre-stress changes in positive affect.

Among the seven nodes, resilience showed the highest betweenness (betweenness = 7) and closeness (closeness = 0.026). Resilience was positively associated with the post- and pre-stress change in the gBOLD-CSF coupling and the neural signal extracted from the previously identified clusters, and negatively associated with the post- and pre-stress changes in the negative affect during the acute stress (thresholded weight = 0.1).

Strength centrality outlined the node of the response of negative affect with the highest value (strength centrality = 1.094), which demonstrated a strong association with resilience and the post- and pre-stress changes in the positive affect.

The correlation stability coefficients (CS) for strength centrality were 0.202 and 0.440 for expected influence, and 0.131 for closeness, indicating relatively stable results after 5,000 case-dropping bootstrapping iterations.

DiscussionOur findings indicated that the gBOLD-CSF coupling fluctuated temporarily during and after acute stress, suggesting that the glymphatic system may be transiently disrupted during stress with subsequent recovery. These dynamic changes in the glymphatic system were closely linked to multidimensional stress responses, including fluctuations in negative affect and neural activity in prefrontal regions (e.g., orbitofrontal cortex, anterior prefrontal cortex). The association with cortisol reactivity was observed only when the cortisol awakening response was heightened, validating the immunomodulatory role of the glucocorticoids. These findings suggest an intrinsic interaction between stress-associated affective changes, neuroendocrine responses, and the brain waste clearance process. Moreover, a larger post- and pre-stress change in the glymphatic system was associated with higher trait resilience. Notably, this glymphatic response emerged as a critical hub within the network of multi-level stress response, immune homeostasis, and psychological resilience.

We highlighted the plasticity of the glymphatic system during acute stress in healthy middle-aged individuals, which manifested as gBOLD-CSF coupling strength decreased immediately after stress but returned to a level comparable to baseline following a 60-minute rest. Similar to the functional plasticity in immune cells (Almeida & Belz, 2016) and the transient glucocorticoid release during stress (Aguilera, 2011), the dynamic fluctuation and recovery are essentially necessary for maintaining immune homeostasis, neuronal plasticity, and normal brain function (Russell & Lightman, 2019). The captured changes in gBOLD-CSF coupling under stress may reflect subtle changes in the volume, speed, and properties of the CSF fluid and the hemodynamic waves that it potentially affects during the stress response. Nevertheless, a successful recovery was eventually achieved to buffer against the stress-related neurobiological changes in healthy conditions.

The observed stress-related changes in the glymphatic system were associated with multifaceted stress responses. Specifically, reduced coupling strength after stress and its subsequent recovery were related to more post-stress negative affect which also recovered, and showed a marginal relationship with positive affect. Stress significantly increases negative affect and anxiety (Feldman et al., 1999; Nordberg et al., 2022). In contrast, recalling positive memories or maintaining a positive outlook helps buffer against the negative consequences of stress (Aschbacher et al., 2012; Speer & Delgado, 2017). Maintaining positive affect through active coping processes may benefit in resolving the stress response (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). In summary, this study revealed consistent dynamic patterns in transient, stress-induced changes in affective and immune systems.

We observed impaired coupling strength reflecting poorer glymphatic system recovery with significantly weaker neural activations under stress conditions, especially in areas of the left orbitofrontal cortex (OFC; Brodmann Area 11) and right aPFC (Brodmann Area 10), two regions implicated in emotion regulation, and stress response and coping (Cerqueira et al., 2008; Gathmann et al., 2014; Kern et al., 2008; Seo et al., 2011). Stress modulates the dendritic characteristics and affects neuron structure in OFC in rodents (Sequeira & Gourley, 2021). Stronger baseline aPFC activity was associated with attenuated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms following trauma in high-risk individuals (Kaldewaij et al., 2021). Considering the reversible effect of stress on disrupting neural activation (Liston et al., 2009), a poorer recovery of the glymphatic system, related to blunted activation in the above area, may reflect the poor plasticity of the system linked to the inefficiency of the neural system in coping with stress. In this case, the glymphatic system was unable to provide efficient support, thereby preventing the neural network from recovering, especially when stress persisted over time. Similarly, Han et al. (2024a) observed weaker regional BOLD-CSF coupling in the default mode and frontoparietal networks in older adults with amyloid-β accumulation. This highlights the promise of investigating the coupling between CSF and BOLD signals in functional connectivity networks or stress-related regions to provide more nuanced insights into stress responses.

The change in the glymphatic system after acute stress from baseline was positively associated with psychological resilience and the magnitude of cortisol awakening response. Individuals with higher trait resilience exhibited greater dynamic reactivity in their glymphatic function, demonstrating a more sensitive and robust response to external stress challenges. Similarly, larger reactivity in the glymphatic system was associated with a greater cortisol awakening response, indicating a basal hyperactivation of the HPA axis enabling the body to better prepare for the day's stressors and potentially sensitizing the immune system (Clow et al., 2010; Fries et al., 2009; Silverman et al., 2005). This also echoes the observed neuroendocrine-immune interaction between the HPA axis and the glymphatic system, where a larger acute cortisol response was associated with a larger change in the glymphatic system exclusively in individuals with a very high cortisol awakening response. Lower cortisol awakening responses were found to be associated with chronic stress (Duan et al., 2013) and lower levels of trait resilience in individuals vulnerable to suicide (O'Connor et al., 2021). In healthy conditions, the observed heightened reactivity in the glymphatic system and cortisol reactivity may better signal the body to prepare for disturbances, thereby enabling more efficient recovery and a greater capacity for adaptation (Chen et al., 2017; McEwen, 2004), which are potential mechanisms that contribute to psychological resilience. Together, these findings suggest that a more responsive and flexible glymphatic system and neuroendocrine system may be considered as adaptive physiological underpinnings of psychological resilience.

Ultimately, we identified the response of the glymphatic system as the key node in the multi-level stress-response network, while the node of psychological resilience showed the highest centrality. The glymphatic system stood out from the multi-layer affective, endocrinological, and neural responses; thus, not only did we verify it as an essential part of the stress response, but also outlined its critical role as a lever in the network to impact other processes. The highest betweenness and closeness centrality of resilience in the network suggests the importance of harmonious synchronization and integration of neuroendocrine, immune, and neural reactions in promoting psychological resilience (Bottaccioli et al., 2019). These findings emphasize the pivotal role of the glymphatic system in the stress response framework, inspiring future translational research investigating this relationship in clinical populations such as individuals with major depressive disorders and PTSD. Furthermore, designing interventions targeting this system to improve neuro-immune homeostasis and alleviate maladaptive stress response cascades would help foster psychological resilience.

Several limitations are worth noting. First, due to the inconvenience of collecting saliva samples multiple times during MRI scanning, acute stress was induced by two paradigms in two studies. Nevertheless, the MIST was derived and developed from TSST to adapt for MRI scanning for stress induction (Dedovic et al., 2005). Future studies utilizing robust physiological sampling to re-examine the nuanced relationships between cortisol response and gBOLD-CSF coupling response under stress in a single sample are necessary. Second, the cortisol awakening response was only measured over a one-day sampling period. Future studies should follow the guidelines for measuring the cortisol awakening response and control for additional comprehensive covariates that may affect endocrinological responses (Stalder et al., 2016). Third, we did not include a control condition with three rs-fMRI collected but without going through the MIST task to fully rule out the effect of confounding factors such as fatigue, neurovascular dynamics, or other mental and physiological processes during the acute stress task, which may influence the level of gBOLD-CSF coupling. However, this well-established stress-induced paradigm applied a within-subject design to control for stable individual differences, and the observed changes were explicitly associated with affective, neural, and endocrine stress responses, suggesting stress-specific changes not simply due to general hemodynamic or neurovascular fluctuations. Future studies may include a non-experimental manipulation control group to exclude the effect of the confounding factors further. Additionally, while the glymphatic system may vary with sleep-wake states and time of day (Benveniste et al., 2019; Fultz et al., 2019), it is generally stable during the daytime (Han et al., 2024b). Since all images were acquired within a narrow afternoon time window, the influence of diurnal variation has been largely controlled. Fourth, the complex nature of resilience results in various quantification approaches. We measured the trait resilience using a well-established questionnaire because it reflects a more stable characteristic of a person over a period. Future studies may consider measuring the dynamic nature of resilience and verify its relationship with the glymphatic system. Finally, the sample size for the network analysis was relatively small, which affected the stability of the network, and all participants were of Chinese ethnicity. Future studies may consider replicating these findings in a larger, multi-ethnic sample.

In conclusion, this study revealed the sensitive and dynamic response of the glymphatic system to acute stress, demonstrating its coordination with psychological, neural, and endocrine pathways in the stress response. This elucidates its influential role in the multi-organ response network within the broader context of stress and psychological resilience. These findings illustrate glymphatic system plasticity as a critical orchestrator of whole-body stress adaptation and a key immune component that underpins psychological resilience.

FundingThis project was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council Collaborative Research Fund (C7069-19G), the Guangdong-Hong Kong Joint Laboratory for Psychiatric Disorders (2023B1212120004), and The University of Hong Kong May Endowed Professorship in Neuropsychology.

CRediT authorship contribution statementRachel R. Jin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Li Liang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. Horace Tong: Data curation, Methodology. Menglu Chen: Data curation, Methodology. Tatia M.C. Lee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Anthony Liu of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and Dr. Deming Jiang of Capital Medical University for their methodological comments and suggestions.