This research investigated implicit social sequencing in adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Previous research emphasized the role of the cerebellum in autism, and in processing action sequences within social contexts requiring mental state attribution (mentalizing). We therefore hypothesized that individuals with autism would show reduced implicit sequencing in an interactive negotiation game that involves mentalizing.

MethodsParticipants included 20 adults with autism and 20 matched healthy controls. Using a novel ultimatum serial reaction time task, participants received offers for a division of 10 points from multiple proposers and responded as quickly as possible. Unbeknownst to the participants, offers were presented in repeated or random sequences. Additionally, the proposers’ implied traits (egocentric versus generous offers) and the volatility of their offers (variable versus stable) were varied to assess context effects on implicit sequencing.

ResultsAs expected, autistic participants revealed no significant speed differences between repeated and random sequences, while controls were faster in repeated sequences. Considering context effects, both groups were faster in repeated sequences when offers were stable (i.e., identical across trials). Conversely, when offers were volatile, responses slowed down under repeated sequences.

ConclusionFindings suggest reduced implicit social sequencing capacities in adults with autism. Social context factors influenced learning in both groups, indicating that autistic individuals may either perform at typical social levels when statistically controlling for their reduced sequencing capacities, or may sufficiently compensate under explicit task instructions. These results highlight social sequence learning as a promising target for intervention in training programs for autistic individuals.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD; referred to as “autism”) is a neurodevelopmental condition, affecting around 1 in 100 children worldwide (Zeidan et al., 2022). The diversity of symptoms across the spectrum is manifold, yet often characterized by challenges in social interaction and rigid and inflexible patterns of behavior and daily routines (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Murphy et al., 2016).

One widely accepted explanation for the social interaction difficulties in individuals with autism is their reduced capacity for mentalizing (Bylemans et al., 2023; Chung et al., 2014). Mentalizing, sometimes referred to as “theory of mind” (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985), refers to the ability to understand and predict the mental states of others, including their thoughts, feelings, and intentions (Schurz et al., 2014; Van Overwalle, 2009). Mentalizing abilities involve forming mental representations of another person’s perspective, even when it contradicts reality as observed by the individuals themselves (so-called false belief tasks; Saxe et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2021).

Cerebellum and Social SequencingIn the last decade, the cerebellum has been increasingly recognized for its role in social cognition (Heleven & Van Overwalle, 2018; Van Overwalle et al., 2014, 2015, 2020a; Van Overwalle, 2024) and autism (D’Mello & Stoodley, 2015; Hadaya et al., 2022; Limperopoulos et al., 2007; Olivito et al., 2018; Van Overwalle et al., 2022; Velikonja et al., 2019). A well-known function of the cerebellum involves motor coordination, error monitoring, and motor automatization, achieved by constructing internal models (unconscious mental representations) of movement sequences and their anticipated sensory outcomes (Manto et al., 2012; Popa & Ebner, 2019). Additionally, the cerebellum supports internal models of non-motor thoughts and emotions, without overt movements, especially in its evolutionarily younger posterior part (Ito, 2008; Leggio et al., 2011; Leggio & Molinari, 2015; Pisotta & Molinari, 2014; Van Overwalle et al., 2020b; Van Overwalle, 2024). Based on prediction errors, or the difference between anticipated and actual events, the cerebellum generates and continuously refines internal models of social event sequences to facilitate adequate and smooth interactions with the environment. This allows individuals to plan and anticipate social actions by predicting potential response sequences of others and identifying alternative ways to reach a certain goal (Van Overwalle et al., 2020b; Van Overwalle, 2024).

Evidence supporting the role of the posterior cerebellum in social sequencing stems from studies demonstrating that healthy adults recruit the cerebellum in tasks which test explicit sequencing abilities involving the understanding of false and true beliefs (picture sequencing task; Heleven et al., 2019) or action sequencing implying social traits (Pu et al., 2020, 2021, 2022), and implicit learning of social sequencing (belief serial response time task; Ma et al., 2021). Transcranial non-invasive stimulation of the posterior cerebellum led to stronger learning effects in generating social and non-social event sequences during a picture sequencing task, compared to a sham control condition (Heleven et al., 2021), while patients with generalized cerebellar degenerative lesions had difficulties performing this task (Van Overwalle et al., 2019). Together, these studies suggest that social sequencing is supported by the posterior cerebellum, both at the explicit and implicit level.

Social Sequencing in AutismDifficulties in social mentalizing among individuals with autism may be associated with disturbances in processing social sequences (Heleven et al., 2022; Van Overwalle et al., 2022; Van Overwalle, 2024). Specifically, they have difficulties arranging events depicted in cartoon-like pictures or behavioral sentences into the correct chronological order, especially when they involve social beliefs and scripts (Heleven et al., 2022; Zalla et al., 2006). Likewise, the organization of narratives that requires mentalizing about social protagonists is often less efficient in adults with autism, leading to challenges in maintaining a central theme and chronological sequences (Barnes & Baron-Cohen, 2012; Bylemans et al., 2023; Reese et al., 2011).

These difficulties in sequencing and understanding social situations among individuals with autism might be due to their inflexibility in signaling prediction errors (Van Overwalle et al., 2022). This inflexibility can hinder their ability to adapt to novel social sequences, contexts, and the flow of dynamic social interactions. Goris et al. (2021, 2022) suggest that the brain requires mechanisms to determine when prediction errors should inform learning and when they should be ignored. This poses challenges, especially in contexts where conditions are volatile (highly variable) and individuals need to adapt to the varying expectations of others (Arthur et al., 2023). However, to our knowledge, evidence for disrupted social sequencing in autism in implicit contexts has yet to be elucidated.

The Present StudyThe present study investigated implicit social sequence learning in adults with and without autism using a novel combination of the interactive ultimatum game (Güth et al., 1982) and the Serial Response Time task (SRT task; Nissen & Bullemer, 1987), similar to the implicit belief SRT task of Ma et al. (2021). In the ultimatum game, a proposer offers a portion of a sum of points to a receiver (i.e., the participant). If the receiver accepts, both secure the proposed shares; if rejected, both get nothing. Similar to an SRT task, in our adaptation, participants were required to respond as quickly as possible. Crucially, unbeknownst to them, the sequences of offers were either repeated or random. Rapid responses to covertly repeating sequences were intended to facilitate implicit sequence learning and decision-making, whereas random orders were intended to disrupt implicit sequence learning and slow down responding.

The volatility of the offers (i.e., stable versus volatile) and the proposers’ social character traits (i.e., generous versus egocentric) were varied, requiring participants to learn and adapt to the behavior of the proposers over multiple rounds. Specifically, stable proposers typically provide the same amount of points, whereas volatile proposers tend to change their points constantly, making their offers less predictable. In addition, generous proposers typically offer more points to the participant and fewer points to themselves, whereas egocentric proposers typically offer more points to themselves and less to the participant. Thus, participants constantly needed to weigh whether to accept or reject the offer, which makes the interaction at each trial unpredictable, especially for volatile proposers.

Our main hypothesis was that healthy control (HC) participants would reveal faster responses to repeated sequences versus random sequences, indicating intact implicit sequence learning. In contrast, individuals with ASD would show reduced capacities for implicit sequence learning, as indicated by reduced differences in response speed between repeated and random sequences. We also examined to what extent manipulating the context, such as the volatility of the offers and the proposers’ character traits, would influence implicit sequence learning. We made the following additional hypotheses: First, because stable contexts are more predictable than volatile ones, participants would generally show faster responses in stable as opposed to volatile contexts. Second, participants would respond faster when interacting with generous versus egocentric proposers because their offers are more predictable. This is because egocentric offers can sometimes be acceptable if the offer is only moderately unfair (e.g., 6 versus 4) as opposed to very unfair (e.g., 9 versus 1). In contrast, generous offers are always acceptable.

MethodsParticipantsThis study included participants with ASD and matched healthy controls (for sample demographics, see Table 1). The ASD group included 20 Belgian adults (18 years or older). Inclusion criteria consisted of a formal clinical diagnosis of autism and the absence of any concurrent neurological diseases. Candidates with a diagnosis of Schizophrenia spectrum or other psychotic disorders were excluded, while other mental disorders were allowed, given that these often coincide with ASD (Casanova et al., 2020; Lai et al. 2019). Half of the ASD participants reported an additional mental health diagnosis. The prevalence rates observed in our sample appear broadly comparable to those reported in the broader ASD population (reference values in parentheses below), although generally somewhat lower. This implies that our participants are relatively spared from comorbid mental conditions, allowing our results to reflect relatively pure effects of ASD. Specifically, among the 20 ASD participants, 4 (20%) reported a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 62.7% in children; Avni et al., 2018), 3 (15%) reported depression (54.1% in young adults; Kirsch et al., 2020), 1 (5%) reported anxiety (44.6% in children; Avni et al. 2018), 1 (5%) reported bipolar disorder (7.3% in young adults; Kirsch et al., 2020), and 1 (5%) reported post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; over 50% of young adults experience trauma; Taylor et al., 2016). In total, 10 participants (50%) of our ASD group did not report any additional mental health diagnoses. The healthy control group consisted of 20 students from the department of Psychology at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, who were matched for age, sex, and education level to the ASD group.

Demographic Variables per Participant Group.

Note. HC = Health Controls, ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder. N/n = Number of participants; M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation. A two-sided t-test was used to assess group differences on the matched variables age and sex; a chi-square test was applied for hand domination and education. None of these were significant.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. As part of a larger research context, the present study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the University Hospital Ghent and was conducted under the guidelines of the Ethics Committee Human Science (ECHS) of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, in accordance with the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

MaterialsAll information, test materials and experiments were available in Dutch and French, the two official languages of Belgium.

Ultimatum Serial Reaction Time (SRT) TaskIn the ultimatum SRT task (Figure 1), eight virtual partners (“proposers”) offer to split 10 points between themselves and the participant (who is the “receiver”). The participant needs to decide whether to accept or reject the offer. Accepting the offer would result in securing the proposed points, whereas rejecting it would lead to no points being awarded to either party. Acceptance and rejection rates depend on two context factors: (1) the proposers’ Traits, which could be generous (i.e., proposing on average 8 out of 10 points) or egocentric (i.e., proposing on average 2 out of 10 points), and (2) the Volatility of the offers, characterized by stable (i.e., repetitively offering the same split of points) versus volatile input (i.e., offering different splits of points). This resulted in four types of offers: generous-stable (a split of 2:8 for the proposer [“partner”] and receiver [“you”], respectively), generous-volatile (randomly chosen splits of 1:9, 2:8, 3:7, 4:6), egocentric-stable (a split of 8:2), and egocentric-volatile (randomly chosen splits of 9:1, 8:2, 7:3, 6:4). The mean value of the offers within the generous and egocentric conditions was consistent between the volatile and stable patterns, yielding on average offers of 2:8 and 8:2, respectively. The participants were instructed to earn the highest number of points, while responding as quickly as possible. It was explained that maximizing their points depended on both their own strategy and the proposers’ strategies.

An illustration of a block of a repeated sequence in the Ultimatum Serial Reaction Time (SRT) task (with timing expressed in milliseconds). In each condition, participants interact with four unique proposers, each presenting one type of offer: generous-stable (proposing a split of 2:8 for the proposer and receiver, respectively), generous-volatile (1:9, 2:8, 3:7, 4:6), egocentric-stable (8:2), and egocentric-volatile (9:1, 8:2, 7:3, 6:4). During each sequence, each of the four proposers presented two offers to the participant, forming a sequence of eight offers. This sequence was repeated four times, resulting in 32 trials per block. There were nine blocks for each experimental condition (i.e. repeated and random sequence).

The task was divided into two halves, each involving sequences from a set of four unique proposers. Each sequence included a total of eight offers (i.e., two offers from each of the four proposers). In one half of the game, unbeknownst to the participants, the same sequence was consistently repeated. In the other half of the game, the sequences of another set of four proposers were random. The order in which the repeated or random halves were provided was counterbalanced between participants. To maintain participants’ attentiveness and vigilance, they were occasionally presented with reversed offers, where the proposers’ typical allocation of points was reversed with that of the receiver. These reversed trials occurred pseudorandomly only during Reversed Blocks, as opposed to Normal Blocks, and typically lead to slower responses.

ProcedureTesting took place in experiment cubicles with uniform room lighting, noise levels and seating arrangements. The experiment was programmed and executed using E-Prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, 2016) on PCs. Responses were made using keys 1 and 2 on the keyboard, corresponding to left and right responses, respectively.

The participants were given the following instructions: “The goal for you and your partners is to each collect as many points as possible. The strategy you and your partners use will determine who wins the most points. This is a reaction time experiment. Respond as fast as possible, but stay accurate.” They were also shown which keys (1 or 2) to press using their index and middle fingers. It was emphasized that the key assignments could change between sequences. This was done to avoid implicit motor learning during the task. Prior to starting the main experiment, all participants underwent a practice block to familiarize themselves with the task, which consisted of two blocks of 32 trials each. The main experiment itself included nine blocks of 32 trials for each experimental condition (random and repeated sequences), amounting to 18 blocks and 576 trials for the entire experiment. After every second block, participants were given a 15-second break before continuing to the next block.

At each trial, the sequence started with a proposer display for 500 ms in the center of the computer screen. This allowed participants to recall previous offers made by the proposer and to prepare for the upcoming offer. The proposers were represented by images selected from the Radboud Faces Database (RaFD; Langner et al., 2010), which is a pool of standardized faces featuring Caucasian males and females. In total, we selected eight images with neutral facial expressions (50% males). Each proposer was depicted from the head to just below the shoulder line, wearing the same black shirt without any distinguishing features or accessories. The background color of the screen was set to white, and the dimensions of all images were standardized across trials.

The proposer display was followed by the proposer’s offer, to the left and right side of the proposer’s face image, and remained on the screen until a response was given or 10 seconds expired. Two rectangles with white background were used to display the offer (i.e., “Partner: 3, You: 7”, in black font) and the option to reject the offer (“Do not accept”, in red font). As noted earlier, the placement of these rectangles was counterbalanced across each block to minimize potential implicit motor learning effects during the task. Both rectangles overlapped with the face image to ensure that the details of the offer and the rejection option were positioned as close as possible to the face, facilitating more immediate processing of the information. Immediately after a decision was made, the participants continued to the next trial. Of note, participants were earning points throughout the experiment but received no feedback on their intermediate or total scores because our main research focus was on implicit sequence learning.

After each block, participants received a summary of their average reaction time. If averages were above 1000 ms, participants were encouraged to respond faster (“Try to react a little bit faster!”), while those with averages below 1000 ms received positive feedback (“Good, do continue!”).

Subsequently, a proposer’s face from the previous sequence appeared in the center of the screen, along with a trait-related question, for 15 seconds or until a response was made. The face was randomly selected from one of the four proposers from the previous sequence. The question was placed on top of the image (“This person is”), and two additional text boxes indicated the possible response options to the left (i.e., “generous”) or right (i.e., “egocentric”) with equal distance to the face image. Participants could “Answer by pressing the appropriate button left or right”. After a response was provided, the participants received feedback which consisted of one of three outcomes: “Correct”, “Wrong! You lose 20 points”, or “No answer. You lose 20 points” for 1500 ms. Although participants accumulated points throughout the experiment, the trait question was the only occasion where points could be deducted. This was done to encourage participants to pay more attention to the proposers’ traits during the task, so that mentalizing processes during implicit learning were ensured.

After completing the task, participants filled out a funneled questionnaire to assess their awareness of the sequence patterns (Deroost & Coomans, 2018). Questions included, for instance, whether they noticed anything unusual during the experiment. Afterward, they were instructed to “report the order in which the partners occurred”. For our implicit task design to be valid, the participants should not be able to accurately reproduce a significant part of the correct sequence. The total duration of the experiment was one hour.

Statistical AnalysesAll statistical analyses were performed using R (Version 4.4.9; R Core Team, 2024) and Jamovi (Version 2.0; The jamovi project, 2024). The primary measures for the task were reaction times (RT) and accuracy on the trait question. RTs were measured from the onset of the offer until the response. Accuracy was determined based on participants’ responses to trait questions related to one randomly-selected proposer from the preceding trials within a block.

Reaction TimesA series of Linear Mixed Models (LMM) were fitted using the ‘lme4’ R package (Bates et al., 2015). Linear mixed models are suited for the nested structure of the data, that is, they account for repeated measurements across trials and conditions within and between participants. Omnibus F-tests for the fitted LMM were conducted with the ‘car’ package (Fox & Weisberg, 2019). Post-hoc tests for significant interaction effects were carried out using the ‘emmeans’ package (Lenth, 2024). The ‘ggplot2’ package (Wickham, 2016) was used for graphical illustrations of the significant interaction effects. A standard α = .05 was set to determine significant effects. Corrections for multiple comparisons at post-hoc were made using the Bonferroni method.

The LMM included Group (ASD versus HC), Sequence (repeated versus random), Trait (generous versus egocentric), Volatility (stable versus volatile), and the second-degree polynomial of Trial (linear and quadratic) as fixed effects. Polynomials better capture potential non-linear relationships between RT and trial progression. A random intercept for Participants was added to model variability in average RTs across participants. Random slopes were not included. Although this might have increased the explained variance, it also would have further complicated the model. The LMM included all possible main effects and two-way interactions. To increase the parsimony of the model and the degrees of freedom (Aiken & West, 1991), insignificant three, four- or five-way interaction terms were dropped from the final regression model. Categorical predictors were contrast-coded using a sum-to-zero coding scheme and the continuous predictor was mean-centered.

To address violations of the LMM parametric test assumptions (i.e., normality and homoscedasticity of the residuals), the LMM was adjusted to model the natural logarithm of RT (log-transform). This approach was confirmed by a more robust method to model the data (‘robustlmm’ package; Koller, 2016) in R, which does not depend on conventional test assumptions and yielded similar test statistics compared to the log-transformed regression model. The application of the log-transformed LMM to model the data was supported by both the R2 indexes (R2marginal = .027, R2conditional = .486) and a considerable variance of means, which was significantly larger than zero (s2intercept = 0.22, LRT(1) = 6846.37, p < .001).

To control for the influence of covariates including the demographic variables age, gender, education, and handedness, two regression models (with and without covariates) were compared. Based on the goodness of fit measures, there was a better fit for a reduced model without covariate terms (Akaike Information Criterion, AIC = 159027, Bayesian Information Criterion, BIC = 159233), compared to the full model (AIC = 159054, BIC = 159326).

Trait AccuracyA Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) was performed on the accuracy measure, which is appropriate for binary data. In this model, Accuracy (1 = correct, 0 = incorrect) was treated as a response variable, with Group, Sequence, Block (1-9) and their interactions as fixed effects, as well as random intercepts across Participants to account for individual variability. The significance of the fixed effects was assessed through type III Wald tests. All other steps in this analysis were identical to the RT analysis.

To enhance parsimony of the regression model, the three-way interaction between Group, Sequence, Block, as well as the two-way interactions between Sequence and Block, and Block and Group were dropped from the final model due to insignificance. Both the R2 indexes (R2marginal = .013, R2conditional = .393) and a considerable variance of means, which was significantly larger than zero (s2intercept = 2.06, LRT(6) = 466.76, p < .001), supported the application of the GLMM.

ResultsThe overall aim of the statistical analyses was to examine to what extent implicit sequence learning in the ultimatum SRT task differed between participants with and without ASD. Group differences in sample demographics (Table 1) were analyzed using t-tests. The results showed no significant differences between the two groups on the matched variables age and sex.

To validate the implicit nature of the ultimatum SRT task, we assessed participants’ awareness of the sequences. The participants from the ASD and HC groups could accurately reproduce only a limited part of the repeated sequence (of 8 trials), respectively, for 1.7 and 2.25 trials, on average. This confirmed that they were largely unaware of the sequence.

Reaction TimesRecall that a LMM was fitted to test the fixed effects of Group (ASD versus HC), Sequence (repeated versus random), Trait (generous versus egocentric), Volatility (stable versus volatile), and the second-degree polynomial of Trial (linear and quadratic) on RT, while accounting for the variability in means across Participants (i.e., random effect).

Main EffectsThe analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed several significant main effects of the second-degree polynomial Trial (F(2, 11456) = 119.16, p < .001), and the factors Trait (F(1, 11456) = 24.21, p < .001) and Volatility (F(1, 11456) = 16.72, p < .001), but not Group (F(1, 11456) = 0.63, p = .431) or Sequence (F(1, 11456) = 2.91, p = .088). These results suggest significant RT differences across most predictors; however, both ASD and HC participants showed similar average RTs in our task. Furthermore, average RTs for both random and repeated sequences were not significantly different.

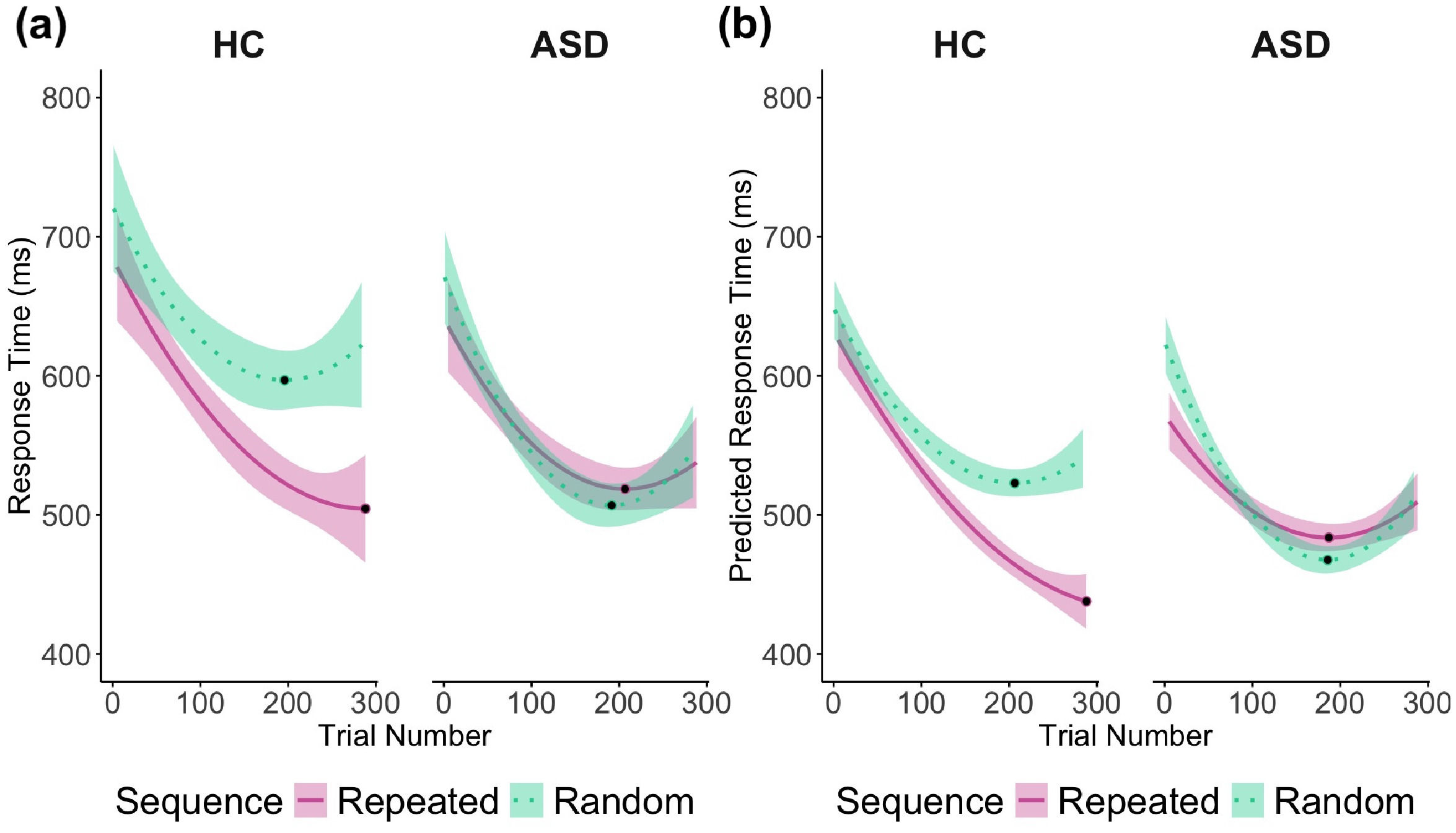

The insignificant main effect of Group is somewhat unexpected, given our hypothesis that individuals with ASD would show reduced implicit sequence learning, which we expected to manifest as relatively slower RTs in the repeated sequence condition, compared to the HC group. However, as shown in Figure 2, the RT performance of ASD participants lies approximately midway between the random (slower RTs) and repeated (faster RTs) conditions of the HC participants. Consequently, the differences between groups balanced out, resulting in the absence of a significant main effect of Group. We interpret this pattern as suggesting that the ASD group may not have shown the expected facilitation effect for repeated sequences, but also did not perform particularly slowly in the random condition. This highlights the importance of examining the interaction effects, which more clearly reveal group differences in sequence-specific learning.

Smoothed Observed (a) and Predicted (b) RTs across Trials by Sequence (repeated vs. random) and Group (ASD vs. HC). Panels (a) and (b) illustrate group-specific differences in response dynamics during the ultimatum SRT task, highlighting patterns in learning and adaptation across repeated and random sequences. RTs are smoothed with second-degree polynomial fits generated using the geom_smooth function in ggplot2. The y-axes represent RTs converted back from natural logarithms for ease of interpretation. Shaded areas display 95% confidence intervals, while black dots mark the minimum RTs for each condition. In Panel (b), predicted minimum RTs for HC occurred at trial 206 (block 7) in the random sequence (523 ms), and at trial 288 (block 9) in the repeated sequence (438 ms). For ASD, predicted minimum RTs occurred at trial 186 (block 6) in the random sequence (468 ms) and at trial 187 (block 6) in the repeated sequence (484 ms). HC = Healthy Controls, ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Our main hypothesis was that RTs would vary between groups in response to different sequences (random versus repeated) when learning progresses across trials. A significant three-way interaction effect was found between Group, Sequence, and Trial on RT (F(2, 11456) = 9.27, p < .001) (Figure 2). This suggests that the two-way interaction between Sequence and Group significantly differed across Trials (F(1, 11456) = 11.67, p < .001). The other underlying two-way interaction effects were also significant, including the interactions between Sequence and Trial (F(2, 11456) = 3.55, p = .029), and Group and Trial (F(2, 11456) = 8.85, p < .001).

Figure 2b shows that, as hypothesized, the predicted RTs for the HC group were generally faster in the repeated compared to the random sequence, and this difference became more pronounced across trials. To statistically test our main hypothesis, average RT differences between sequences were assessed for each group by comparing their slope coefficients calculated at -1 standard deviation (SD), the mean (M), and 1 SD of Trial. The results indicated that for the HC group, average RT differences between sequences increased with the progression of trials. Although these differences were not significant at the beginning trials (the -1 SD level of Trial: B(-1SDTrial) = -0.034, SE = 0.018, 95%CI [-0.070, 0.002], t(11456) = -1.83, p = .067), they became significant only at further trials (at the mean levels of Trial: B(MTrial) = -0.070, SE = 0.019, 95%CI [-0.108, -0.032], t(11456) = -3.62, p < .001; and at 1 SD levels of Trial: B(1SDTrial) = -0.143, SE = 0.018, 95%CI [-0.179, -0.107], t(11456) = -7.78, p < .001).

In contrast, as hypothesized, no significant RT differences between sequences were observed for the ASD group across all levels of Trial (F(1, 11456) = 1.47, p = .226). This indicates that, on average, RTs for both repeated and random sequences were similar across trials. However, as indicated by the significant interaction between Group and Trial, the ASD group displayed a significant decrease in average RT across trials, irrespective of the sequence (B = -0.0005, t(11456) = -7.01, p < .001), suggesting a general ability to adjust to the task.

Interaction Effects between Sequence, Volatility, and TraitOur additional hypotheses related to the extent to which context factors, such as Volatility of the offers (stable versus volatile) and Traits (generous versus egocentric) influence RTs across Sequences, Groups, and Trials. The results of the ANOVA indicated a significant three-way interaction among Sequence, Trait and Volatility on RT (F(1, 11456) = 20.65, p < .001). Additionally, there were significant two-way interactions between Sequence and Volatility (F(1, 11456) = 15.44, p < .001), and between Volatility and Trait (F(1, 11456) = 4.86, p = .027), but not between Sequence and Trait (F(1, 11456) = 1.92, p = .166). Note that no significant effects were detected when taking Group or Trial into account, suggesting that the pattern of interactions of contextual factors described below were similar across trials for both ASD and HC groups.

Considering the two-way interaction between Sequence and Volatility, participants responded faster in the repeated sequence (M = 433 ms, SE = 32.30, 95%CI [373, 504]), compared to the random sequence (M = 460 ms, SE = 34.20, 95%CI [396, 534]), when offers were stable, which is in line with our hypothesis. In contrast, RTs between sequences were similar under volatile offers. However, further analysis revealed that this interaction effect depended on the third variable Trait.

The significant three-way interaction indicated that the effect of Sequence on RTs varied depending on the combination of Trait and Volatility (Figure 3). Simple effect analyses revealed that when the proposer was generous and made stable offers, there was no significant effect of Sequence on RTs (F(1, 11456) = 2.11, p = .146). However, if the proposer was generous but made volatile offers, the effect of Sequence was significant (F(1, 11456) = 3.95, p = .047).

Mean RTs as a Function of Sequence (repeated vs. random), Volatility (stable vs. volatile), and Trait (egocentric vs. generous). This bar graph demonstrates the differential effects of the context factors trait and volatility on responses across repeated and random sequences. The y-axis represents RTs in milliseconds converted back from natural logarithms for ease of interpretation. Significant differences between repeated and random sequences are denoted by asterisks, with *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p <.001. Error bars indicate standard errors around the mean.

Specifically, a pairwise comparison indicated that in the generous-volatile condition, RTs slower in the random sequence (M = 459 ms, SE = 34.60, 95%CI [394, 534]), compared to the repeated sequence (M = 440 ms, SE = 33.20, 95%CI [378, 513]). This is in line with the hypothesis that both the unpredictability in random sequences and inconsistency of the offers slow down responding.

When the proposer was egocentric, the effect of Sequence was significant under both stable (F(1, 11456) = 17.72, p < .001) and volatile offers (F(1, 11456) = 10.15, p = .001). However, pairwise comparisons indicated that the direction of effects varied depending on whether offers were stable or volatile. That is, when the proposer was egocentric but made stable offers, RTs were faster in the repeated sequence (M = 435 ms, SE = 32.80, 95%CI [374, 507]), compared to the random sequence (M = 475 ms, SE = 35.80, 95%CI [408, 553]). This is in line with the hypothesis that predictable and consistent patterns will speed up responding. However, unexpectedly, when egocentric proposers made volatile offers, this RT difference between sequences reversed, and the repeated sequence led to slower responses (M = 513 ms, SE = 38.60, 95%CI [440, 597]), compared to the random sequence (M = 479 ms, SE = 36.10, 95%CI [411, 558]). This contradicts our hypothesis that predictable patterns would consistently speed up performance.

No significant effects were detected when taking Group or Trial into account, suggesting that the interaction among Volatility, Trial, and Sequence was similar across trials for both ASD and HC groups.

AccuracyA GLMM (logistic regression) was used to test the effects of Group, Sequence, Block and their interactions on Accuracy (0 = incorrect, 1 = correct) in analogy with the main analysis on RTs (Figure 4). The intercepts (means) were allowed to vary as random effects across Participants. Note that trait questions were asked once per block, whereas in the prior analysis RTs were measured per trial. Insignificant interaction terms were dropped from the final regression model.

Predicted Accuracy on Trait Questions across Blocks (1-9) and Groups (ASD vs. HC). This probability plot demonstrates that there were no significant differences between groups, suggesting similar accuracy patterns across blocks for both Healthy Controls (HC) and individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The predicted probabilities represent the likelihood of correct (p = 1) or incorrect (p = 0) responses to trait-related questions at the end of each block. Shaded areas display 95% confidence intervals around the predicted probabilities.

There were significant main effects of Block (χ2(1) = 7.33, p = .006) and Sequence (χ2(1) = 6.66, p = .010) on Accuracy. Specifically, pairwise comparisons indicated that participants were 1.06 times more likely to give a correct answer to the trait question for each additional block (exp(B) = 1.06, 95%CI [1.02, 1.10]). Similarly, the odds of giving a correct answer increased by 1.31 (exp(B) = 1.31 95%CI [1.07, 1.62]) in response to repeated (pcorrect = .888, 95%CI [.830, .928]), compared to random sequences (pcorrect = .858, 95%CI [.789, .907]). No main effect was observed for Group (χ2(1) = 0.001, p = .976), indicating that accuracy rates were about equal for both ASD and HC groups.

Interaction EffectsFurthermore, the analysis revealed a significant interaction effect between Block and Sequence on accuracy (χ2(1) = 10.43, p = .001). As illustrated in Figure 4, Accuracy was significantly different across blocks in the random sequence (χ2(1) = 18.40, p < .001), but not in the repeated sequence (χ2(1) = 0.13, p = .717). Specifically, for every additional block, the chance of answering correctly in the random sequence increased by 1.13 (exp(B) = 1.13 95%CI [1.07, 1.19]). In contrast, accuracy rates in the repeated sequence were similar across trials.

Because these accuracy patterns were equal for both ASD and HC groups, this suggests that previously reported differences in reaction times were not due to differences in accuracy.

DiscussionThe present study investigated implicit sequencing in adults with and without ASD, using an adapted version of the ultimatum game inspired by the classic SRT task, termed the ultimatum SRT task. Participants responded rapidly to random or repeated sequences of offers, whereby implicit learning of repeated sequences might aid in the anticipation of the proposers’ upcoming offers. Thus, successful performance on this task involved understanding and monitoring the offer behavior of multiple proposers throughout the task. This included evaluating offers with varying degrees of predictability and remaining attentive to potential inconsistencies in the proposers’ typical offers.

Implicit Social Sequence Learning in AutismConsistent with our main hypothesis, the HC group consistently showed faster RTs in repeated compared to random sequences while the experiment progressed, while the ASD group revealed similar RTs in both repeated and random sequences. This implies that the ASD group had reduced abilities to implicitly learn and make use of the predictive structure of repeated social sequences. These findings suggest reduced implicit social sequence learning in ASD in comparison with intact learning in HC.

The results from our ultimatum SRT task confirm and expand upon previous literature on implicit learning and sequencing in autism and typical development. It is possible that individuals with autism face widespread challenges in learning sequences. This is evident in their difficulties with both relatively simple motor sequences (Mostofsky et al., 2000; Sharer et al., 2016) and more complex social sequences, both explicit (Heleven et al., 2022) and implicit, as demonstrated in our study. We propose that social skills are developed through both implicit and explicit learning mechanisms, which help detect the temporal and spatial sequences of facial, gestural, and vocal cues, as well as the actions of others, in order to understand their mental beliefs and traits. In autism, there seems to be a disturbance of these mechanisms, which may contribute to the development of social and communication difficulties (Mostofsky et al., 2000).

Contrary to our results in the social cognitive domain, studies in other domains have found somewhat intact implicit sequencing abilities in autism using a range of SRT tasks measuring visuospatial (Treves et al. 2024), motor (Travers et al., 2010), and linguistic sequencing abilities (Brown et al., 2010). Zwart et al. (2017, 2018) suggested that in implicit procedural learning tasks (i.e., SRT task), individuals with autism rely on explicit (i.e., more deliberate) learning strategies to some degree, which could explain why studies often find similar behavioral outcomes when comparing participants with autism to control participants who primarily engage in implicit learning (Zwart et al., 2018). These compensatory strategies may fall short in more complex, real-life social interactions which require understanding others through implicit learning of facial, gestural, and vocal sequences (Zwart et al., 2017).

The Influence of Traits and VolatilityOur secondary hypotheses examined how implicit learning is influenced by the proposers’ traits (generous versus egocentric) and the volatility of their offers (stable versus volatile). Note from the outset that no significant differences were found between participants with and without ASD, so that the findings and implications we discuss next are equally applicable for both groups. We return to this interesting null finding at the end of this section.

Stable offers involved the same offer (i.e., 8 versus 2) across most trials by the same proposer, while volatile offers involved a varying set of offers by the same proposer (i.e., 9 versus 1, 8 versus 2, 7 versus 3, and 6 versus 4). In line with our hypothesis, participants generally showed improved performance speed in the implicitly learned sequence when the proposers’ offers were stable throughout the experiment. This effect was absent in more volatile contexts. However, further analyses revealed that this effect was more complex when taking into account the trait of the proposer.

The findings suggest that participants responded more slowly to random sequences (versus repeated sequences) when interacting with generous proposers, with a significant effect observed for volatile offers but not for stable offers. A closer examination of response times (Figure 3) confirms a slow-down effect, which could have been due to a combination of volatility and randomness, increasing variability and thereby reducing the overall predictability of the upcoming offers. Therefore, introducing more variability in typically predictable and advantageous contexts may increase the cognitive demand during decision-making and slow down responses.

In comparison, when participants interacted with egocentric proposers, learning repeated (versus random) sequences led to faster responses in stable contexts when proposers consistently made the same disadvantageous offer of 2 points while keeping 8 points for themselves. In contrast, and to our surprise, the participants revealed slower responses to repeated sequences, compared to random ones, when the offers from egocentric proposers were volatile. This implies that implicit sequence learning may not always be advantageous in certain contexts. Though this finding may initially appear counterintuitive, it is logically sound for the following reason: Although the offers from volatile-egocentric proposers are typically unfair and disadvantageous, an offer of 4 points might still be acceptable (and even perceived as fair by some), whereas an offer of 1 point likely would not. This makes the decision process more complex, as choices to accept or reject egocentric offers depend on the specific context and are therefore more likely to be evaluated on a trial-by-trial basis. Consequently, interactions with volatile-egocentric proposers increase cognitive load and are more time-consuming, leading to slower responses.

In sum, the present findings suggest that navigating and anticipating interactions with multiple partners in different social interactive contexts is more complex than previously hypothesized.

As noted earlier, an interesting finding is that none of these social context effects differed between groups. While this may seem surprising given the reduced social capacities often associated with ASD, it is consistent with our main hypothesis that sequencing difficulties are a key factor underlying many social challenges in ASD. Once sequencing performance was statistically controlled for, the social context effects in the ASD group resembled those of the HC group. An alternative explanation for these findings is that ASD participants were able to compensate for reduced social skills when given explicit task instructions related to these context factors, whereas their implicit sequencing abilities remained unaffected. Both interpretations support our central finding: that sequence processing is limited in the ASD group. If supported by future research, a key implication is that improving sequence processing may help alleviate social difficulties in individuals with ASD. This suggests that explicitly training individuals to identify the chronological order of social interactions or narratives should become an indispensable element of ASD interventions aiming to improve social skills. Supporting this notion, a six-session program (1 hour per session) focused on social sequencing in narratives and mentalizing skills led to significant improvements in the comprehension and production of chronologically coherent social narratives in young adults with ASD (Bylemans et al., 2022).

Outstanding Questions and LimitationsThis study indirectly explored the role of the cerebellum in mentalizing and implicit social sequencing in adults with autism, but left key gaps. Future research should link cerebellar activity to social difficulties, using neuroimaging or non-invasive cerebellar stimulation. Future work should also examine how context factors impact sequence learning across the lifespan. Exploring how social traits (i.e., empathy, generosity, egocentrism) and context (i.e., volatility) affect responses could reveal how unpredictability limits mentalizing and sequencing in autism, especially in early development.

The primary limitation of this study is the small sample size, which may have reduced the statistical power needed to detect significant differences and relationships between groups. However, even with this small sample size, we found significant differences between both groups, perhaps because of the use of a mixed model design and capturing individual variability at the trial level. A second limitation of the present study is that we did not account for various demographic and individual difference factors despite their increasing relevance in clinical practice and autism research (Aylward et al., 2021; Nowell et al., 2015; Russell et al., 2011; Shahid Khan et al., 2024).

Third, although the current study indicates challenges in implicit sequence learning among individuals with autism during social interactions, it remains unclear whether participants used any explicit strategies to learn the hidden sequences.

ConclusionWe applied a novel ultimatum SRT task to advance our understanding of the social difficulties faced by individuals with autism by examining implicit sequencing functions in interactive contexts that require mentalizing. Our results confirm earlier findings of reduced sequencing functions in individuals with autism and extend these to disruptions in implicit sequence learning involving complex social mentalizing. The data further suggest that both the social traits of proposers and the volatility of their offer behavior affected implicit sequence learning across both participant groups. Participants generally profited from repetitions within the learned sequence, especially in situations where participants could reliably predict that the outcome of an interaction would consistently be advantageous or disadvantageous.

Authors' contributionsJAH and FVO conceived the study, JAH, IA, YK, SKT and RMR conducted the experiment and JAH conducted the data analyses, JAH and FVO interpreted the results, JAH drafted the manuscript, FVO edited the manuscript, and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Availability of data, code and materialsAll requested (pseudonymized or anonymous) data are available upon request, excluding data that allow identifying individual participants. All manuals and code for processing the data are also available together with the data.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.