Individuals with social anxiety disorder (SAD) often struggle with forming and maintaining romantic relationships, which are vital for mental and physical health. A core feature of SAD is the use of safety behaviors - strategies to reduce anxiety that may unintentionally maintain negative emotions and impede the development of genuine connections. In the present study, we examined safety behavior use during dates/romantic interactions among individuals with (n = 54) and without SAD (n = 54). We used a daily diary design, in which participants reported on dates/romantic interactions, emotions, and safety behaviors in their daily lives for 21 consecutive days. Results indicated that both individuals with and without SAD used more safety behaviors during dates compared to other interactions, with this effect being significantly stronger for individuals with SAD. Furthermore, safety behaviors during dates were associated with negative emotions, with this effect also being significantly stronger for individuals with SAD. In contrast, no significant association was found between safety behaviors during dates and positive emotions. We discuss these findings within the context of cognitive-behavioral models of SAD, and delineate implications for therapeutic interventions and for the targeting of dating-specific safety behaviors in SAD.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a common mental health condition characterized by an intense fear of social situations in which an individual may be scrutinized or judged by others (Schneier & Goldmark, 2015). It affects approximately 12 % of the population at some point in their lives, making it one of the most prevalent anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., 2005). A key feature of SAD is the use of safety behaviors, which are strategies individuals adopt to reduce or avoid negative emotions and feared outcomes in social interactions (Salkovskis, 1991; see Piccirillo et al., 2016 for a review). These strategies may include avoiding eye contact, speaking softly, or rehearsing conversations in advance. Although intended to reduce anxiety, safety behaviors inadvertently play a significant role in maintaining SAD by preventing individuals from learning that their feared outcomes and negative emotions are manageable or unlikely to occur (Clark & Wells, 1995). It is important to note that the intent or the motivation behind behaviors is the aspect that defines whether a certain behavior would be considered a safety behavior. If the behavior is conducted with the intent of facilitating positive outcomes, it will likely not be a safety behavior, but if the same behavior is done with the intent of reducing anxiety then it could very well be considered a safety behavior.

Individuals with SAD can experience impairment in a wide range of social contexts (Aderka et al., 2012). Romantic interactions in particular are especially important as they are strongly related to physical and mental health (Kansky, 2018) and are especially challenging for individuals with SAD (Alden & Taylor, 2010; Chen et al., 2023; MacKenzie & Fowler, 2013). For instance, individuals with SAD are significantly less likely to form romantic relationships compared to those without the disorder (Ranta et al., 2016), and even when they do establish romantic relationships, these relationships tend to provide less emotional support (Porter & Chambless, 2017), and to involve more criticism and negative behaviors (Porter et al., 2017). Understanding how individuals with SAD employ safety behaviors in romantic contexts can contribute to theoretical models of SAD and can help to develop targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at addressing the unique challenges present in romantic interactions.

In line with the theoretical models of SAD which highlight the important maintaining role of safety behaviors in the disorder (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995), empirical studies have found that individuals with SAD use more safety behaviors compared to individuals without SAD (Oren-Yagoda et al., 2024), and the frequency of safety behavior use was found to be correlated with the severity of SAD symptoms (Kyron et al., 2023). Similar findings have been reported in non-clinical samples (i.e., individuals with high social anxiety used more safety behaviors than individuals with low social anxiety; McManus et al., 2008; Stangier et al., 2006). Finally, the increased use of safety behaviors among individuals with SAD was specifically found in opposite-sex interactions that resembled dates (Stevens et al., 2010). Dates and romantic interactions have been found to be especially anxiety-provoking for individuals with SAD (Alden & Taylor, 2010; Chen et al., 2023; MacKenzie & Fowler, 2013). For instance, among individuals with SAD, intimate date-like interactions have been found to lead to increased anxiety compared to other interactions such as small talk (Asher & Aderka, 2020). Dating may be especially anxiety provoking as it includes a pronounced evaluation component that is focused on core aspects of the self (on who one is as a person), and this is less so in other interactions. Therefore, it is likely that individuals with SAD would utilize more safety behaviors in romantic interactions due to this heightened anxiety and/or difficulty.

A number of studies have investigated whether use of safety behaviors is associated with negative emotions and/or negative affect. For instance, Moscovitch and colleagues (2013) found an association between the use of safety behaviors and negative affect among individuals with SAD. Specifically, they found that use of safety behaviors during a speech task was associated with increased negative affect following the task (Moscovitch et al., 2013). In another study, Wells et al. (2016) found that dropping safety behaviors during exposure exercises was associated with greater reductions in anxiety. Along these lines, dropping safety behaviors was found to lead to reductions in anxiety during treatment for SAD (Morgan & Raffle, 1999). Complementing these studies on reductions in safety behaviors, Langer and Rodebaugh (2013) experimentally manipulated gaze avoidance in order to increase the use of this safety behavior during a social interaction. They found that individuals who increased their gaze avoidance experienced increases in anxiety compared to individuals who did not increase gaze avoidance throughout the interaction.

One recent study has examined safety behaviors and positive emotions (Oren-Yagoda et al., 2024). In this study, individuals with and without SAD completed an experience sampling measurement (ESM) for 21 days, and safety behaviors were not found to be significantly associated with positive emotions for the entire sample. However, the authors did find that when social anxiety levels were high (but not low or medium) a negative association emerged (i.e., safety behaviors were associated with lower levels of positive emotions). Importantly, this study focused on social interactions more broadly, rather than romantic interactions in particular.

The present study was designed to add to the literature on safety behaviors in SAD, by specifically focusing on dates which are typically the first stage of developing a romantic relationship. Examining dates is important, as romantic interactions are pivotal for mental health, and have a large impact on individuals’ quality of life (Kansky, 2018). Dating is also particularly anxiety-provoking for individuals with SAD (e.g., Asher & Aderka, 2020). Thus, understanding more about safety behaviors during dating can inform our understanding of SAD as well as the development of therapeutic interventions. In addition, the present study was designed to maximize external validity and complement previous lab studies (e.g., confederate studies), by examining dates of individuals with SAD in a naturalistic setting as part of participants’ daily lives. Whereas lab-based studies prioritize internal validity at the expense of external validity, naturalistic studies have the opposite priority. Thus, naturalistic studies can complement previous studies in the field. Finally, the present study included an examination of positive emotions following dates as positive emotions have been found to play an important role in SAD (e.g., Kashdan et al., 2011; Oren-Yagoda et al., 2023; Walukevich-Dienst et al., 2020). Specifically, we examined individuals with (n = 54) and without SAD (n = 54), who completed a daily diary assessment over the course of 21 days. Participants reported on dates and romantic interactions occurring in their daily lives, as well as on concomitant safety behaviors and positive and negative emotions.

Our preregistered hypotheses were:

(H1) Individuals with SAD will report using more safety behaviors compared to individuals without SAD throughout the daily diary period.

(H2) Participants will use more safety behaviors during dates compared to other social interactions. The difference in safety behavior use between dates and other interactions will be greater among individuals with SAD compared to those without SAD (this reflects a Diagnosis × Dating interaction effect when predicting safety behaviors).

(H3) Safety behaviors during dates will be positively associated with negative emotions. This association will be stronger for individuals with SAD compared to those without SAD (this reflects a Diagnosis × Safety behaviors interaction effect when predicting negative emotions).

***We will explore whether SAD and safety behaviors during dates predict positive emotions (i.e., a version of H3 with positive emotions as the dependent variable) without an explicit hypothesis due to the limited literature.

MethodThe design, hypotheses, and analysis plan of the present study were preregistered online (https://osf.io/t9mcv?view_only=2f6ac3d564344895a82df778820ca1fa).

ParticipantsA total of 108 individuals aged 18–33 who were not in a romantic relationship participated in the study. The participants were divided equally, with half diagnosed with SAD (n = 54) and half without SAD (n = 54). Each group was also balanced by gender, with an equal number of men and women (among both individuals with and without SAD). We sampled men and women equally, because gender can significantly influence emotions and behaviors in romantic contexts (Boyacioglu et al., 2017; Buss & Schmitt, 2019). Participants were recruited either through the Psychology Department's computerized experiment system (i.e., they were undergraduate psychology students who participated for course credit), or recruited via social media for payment.

The study was introduced to new participants as a study that examined dating. For inclusion in the SAD group, criteria were (a) being between the ages of 18 and 33; (b) having a diagnosis of SAD confirmed through a clinical interview (in cases of comorbid conditions, participants were only included if SAD was their primary diagnosis); and (c) not being in romantic relationship at the time of the study. For inclusion in the control group, criteria were (a) being between the ages of 18 and 33; (b) being ruled out as having SAD based on a clinical interview conducted in the lab; and (c) not being in romantic relationship at the time of the study. Exclusion criteria for both groups included the presence of psychotic symptoms and/or significant suicidal ideation (both exclusion criteria were assessed as part of the diagnostic interview).

Current comorbid diagnoses among individuals with SAD included major depressive disorder (n = 20, 37.0 %), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 9, 16.7 %), obsessive–compulsive disorder (n = 4, 7.4 %), panic disorder (n = 3, 5.6 %), and posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 2, 3.7 %). Current diagnoses among individuals without SAD included major depressive disorder (n = 3, 5.6 %), obsessive–compulsive disorder (n = 1, 1.9 %), panic disorder (n = 1, 1.9 %), and posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 1, 1.9 %).

ProcedureScreeningIndividuals interested in participating in the study were asked to complete a short questionnaire in which they provided their age, indicated whether they were in a romantic relationship, and completed the mini-SPIN, a brief screening measure for SAD based on three items (Connor et al., 2001). Participants who met the inclusion criteria and received high scores (8 and above), suggesting a high likelihood of having SAD, as well as those who met the inclusion criteria and received low scores (2–5), indicating a low likelihood of having SAD, were contacted by research staff via phone. During this initial phone call, participants received information about the study, and if they were interested, a diagnostic session was scheduled.

Diagnostic sessionThe diagnostic session involved completing informed consent forms, a full diagnostic interview, and a battery of self-report measures (which also included information on sexual orientation). These sessions were conducted remotely via Zoom. The diagnostic interview was based on the Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5 (ADIS; Brown & Barlow, 2014). In addition, psychotic symptoms and suicidality were evaluated using sections L and C of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998). The interviewers were graduate students who had completed training using diagnostic interviews before the study began. Training as well as ongoing supervision for interviewers was provided by a senior licensed clinical psychologist with more than 20 years of experience in diagnosing and treating SAD.

Daily diary measurementFollowing the diagnostic session, participants were asked to answer questions about their day, every evening for a period of three weeks. Specifically, each evening at 8pm participants received a link to the daily diary via SMS and were asked to complete it as soon as they could and no later than 11pm. The daily diary asked participants to rate the intensity of emotions they experienced that day (using a version of the PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1994), to describe any romantic or other social interactions they engaged in (see measures section ahead), and to report safety behaviors they used during those interactions (based on the factors of the Subtle Avoidance Frequency Examination; Cuming et al., 2009).

MeasuresScreening measureThe mini-Social Phobia Inventory (mini-SPIN; Connor et al., 2001) was utilized to screen for SAD. In this short measure, individuals indicated their level of agreement with three statements using a 5-point Likert scale. The mini-SPIN has been shown to possess good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.85) and exhibits both convergent and divergent validity (Weeks et al., 2007). The total score of the mini-SPIN has been shown to be a reliable tool for predicting a diagnosis of SAD (Connor et al., 2001).

Measures administered in the diagnostic sessionDiagnoses. Diagnoses of SAD were determined using the Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5 (ADIS; Brown & Barlow, 2014). The ADIS is a semi-structured interview designed to assign DSM-5 diagnoses (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). During the interview, clinicians rate the severity of each diagnosis on a scale of 0 to 8, with a score of 4 marking the threshold for a clinical diagnosis. The previous version of the ADIS (ADIS-IV-L) demonstrated strong reliability for diagnosing SAD (κ = 0.77; Brown et al., 2001). Additionally, studies conducted in our lab showed high inter-rater reliability for SAD diagnosis (κ = 0.86; ***MASKED FOR REVIEW***). Diagnoses for other anxiety disorders and depression were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al. 1997; Sheehan et al. 1998).

Psychotic Symptoms and Suicidality. Sections L and C of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al. 1997; Sheehan et al. 1998) were used to assess suicidality and psychotic symptoms, respectively. The MINI has shown good sensitivity (0.84) and specificity (0.89) for diagnosing psychotic disorders compared to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID; Sheehan et al. 1997). Additionally, the MINI demonstrated good predictive utility for suicidal behavior (Roaldset et al., 2012).

Social Anxiety Symptoms. Social anxiety severity was measured using the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN; Connor et al., 2000). The SPIN consists of 17 items that participants rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 4 = extremely). Scores of 20 or below indicate minimal or no social anxiety, scores between 21–40 reflect clinically impairing social anxiety, and scores above 40 indicate severe social anxiety (Connor et al., 2000). Connor et al. (2000) found that individuals diagnosed with SAD had an average score of 41.1 (SD = 10.2) on the SPIN, compared to a mean of 12.1 (SD = 9.3) for those without SAD. The SPIN has demonstrated strong internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Antony et al., 2006; Connor et al., 2000; Radomsky et al., 2006).

Depressive Symptoms. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Beck Depression Inventory – II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996a). The BDI-II is widely used and known for its high reliability and validity (Beck et al., 1996b), both in clinical samples (Sprinkle et al., 2002) and non-clinical samples (Storch et al., 2004; Whisman et al., 2000).

Daily diary measuresSafety Behaviors. Based on the three factors identified by the Subtle Avoidance Frequency Examination (SAFE; Cuming et al., 2009), participants responded to three daily questions about their use of avoidance and safety behaviors in social situations during the day. The questions were: (1) Did you do anything to reduce your anxiety during the social situation? (e.g., rehearsing what to say beforehand); (2) Did you avoid doing something to lessen your anxiety in the social situation? (e.g., talking as little as possible); and (3) Did you try to hide any visible physical symptoms of anxiety you felt during the social situation? (e.g., attempting to conceal sweating or trembling). Each question was rated from 0 (not at all) to 5 (almost always), and the sum of the responses comprised the total safety behaviors score. This measure has been previously used and validated among individuals with SAD (Oren-Yagoda et al., 2024).

Emotions. At the end of each day, participants were asked to report their emotions using a modified version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1994). Participants rated the degree to which they experienced eight positive emotions (such as excitement and calmness) and nine negative emotions (such as anger and loneliness) throughout the day on a 6-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Romantic and Other (Non-romantic) Interactions. Participants were asked whether they attended a date/romantic interaction during the last day. If they answered negatively, they were then asked if they had any other (non-romantic) social interactions that day. Further questions (such as those about safety behaviors described in the next section) referred to the romantic interactions (if they occurred), or to other, non-romantic interactions (if romantic interactions did not occur).

Analytic strategyWe used Hierarchical Linear models to analyze the data due to their nested structure. Specifically, repeated daily measurements formed the level 1 units, and these units were nested within participants (which were level 2 units). We used bootstrapped confidence intervals for all analyses, and coded categorical independent variables using effects coding (i.e., +1 and −1 for dichotomous variables). We used random intercepts as well as random slopes for all level 1 independent variables. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used in all analyses, as well as an unstructured covariance structure.

To examine H1 we used diagnosis (SAD vs. no SAD) as a dichotomous level 2 independent variable, and safety behaviors as a continuous level 1 dependent variable. To examine H2, we used diagnosis (SAD vs. no SAD; a dichotomous level 2 variable), dating (romantic date vs. other social interaction; a dichotomous level 1 variable), and their cross-level interaction as independent variables. The dependent variable was safety behaviors (continuous level 1 variable). To examine H3, we used diagnosis (SAD vs. no SAD; a dichotomous level 2 variable), safety behaviors (continuous level 1 variable), and their cross-level interaction as independent variables. The dependent variable was negative emotions (continuous level 1 variable). For our exploratory analyses, we repeated the analysis for H3 with positive emotions (continuous level 1 variable) as the dependent variable.

ResultsThe data used in the analyses, a codebook to ensure all variables are clearly understood, and the code for conducting all the analyses are available online (https://osf.io/xeqjp/?view_only=42e5ba8f33ab48528d7c1698b3259343).

Demographic and clinical measuresTable 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. The study included 54 individuals with SAD and 54 individuals without SAD, with equal numbers of men and women in each group. Among the participants, 89 (82.4 %) reported being attracted to the opposite sex, 8 (7.4 %) to the same sex, and 11 (10.2 %) to both sexes. Individuals with SAD reported significantly higher levels of social anxiety and depressive symptoms compared to those without SAD. No other significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of demographic characteristics (see Table 1).

Demographic and Clinical Measures.

Note. SAD = social anxiety disorder; Mini-SPIN = Mini-Social Phobia Inventory; SPIN = Social Phobia Inventory; BDI = Beck's Depression Inventory.

Among individuals with SAD (n = 54), 35 individuals (64.8 %) attended one or more dates over the course of the study. The average number of dates among individuals with SAD was 2.56 (SD = 3.04) and the total number of dates was 138. Among individuals without SAD (n = 54), 38 individuals (70.4 %) attended one or more dates over the course of the study. The average number of dates among individuals without SAD was 3.33 (SD = 3.65) and the total number of dates was 180. In addition, individuals with SAD reported 17.08 non-romantic social interactions on average (SD = 3.04) and individuals without SAD reported 16.36 non-romantic social interactions on average (SD = 3.65). The total number of non-romantic interactions was 921 for individuals with SAD and 883 for individuals without SAD. Of these non-romantic social interactions, 43.9 % were with peers or colleagues at work/school, 32.3 % were with friends, 13.3 % were with family members, 4.6 % were with strangers, 4.3 % were with acquaintances, and 1.6 % were with superiors at work or school (e.g., boss or professor).

The average safety behaviors score on dates for individuals with SAD was 6.51 (SD = 3.67), and the average safety behaviors score on dates for individuals without SAD was 2.13 (SD = 2.55). The average safety behaviors score in non-romantic social interactions for individuals with SAD was 3.68 (SD = 2.84), and the average safety behaviors score in non-romantic social interactions for individuals without SAD was 1.09 (SD = 1.09).

Missing dataThe present study included 2268 measurements (108 participants × 21 days). Of these measurements, 2100 (92.6 %) included complete data and 168 (7.4 %) were missing. We conducted Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test to examine the pattern of missing data and found a nonsignificant result. This indicates that the pattern of missing data did not significantly differ from a random distribution of missingness (χ2=9.48, df =9, p=.39). To sum, the amount of missing data was small, there was no indication of systematic bias (i.e., data were MCAR), and HLM is well suited for dealing with missing data (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). As a result, we chose to base analyses on complete data (number of valid measurements: 2100).

Hypothesis 1 – safety behavior use in SADWe examined an HLM model with diagnosis (SAD vs. no SAD) as a dichotomous level 2 independent variable, and safety behaviors as a continuous level 1 dependent variable. We found a significant effect for diagnosis (B = 1.39, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 1.28 to 1.49) such that individuals with SAD used significantly more safety behaviors (estimated M = 4.00) compared to individuals without SAD (estimated M = 1.22).

Hypothesis 2 – safety behavior use on dates vs. other interactionsWe examined an HLM model with diagnosis (SAD vs. no SAD; a dichotomous level 2 variable), dating (romantic date vs. other social interaction; a dichotomous level 1 variable), and their cross-level interaction as independent variables. The dependent variable was safety behaviors (continuous level 1 variable). We found a significant effect for diagnosis (B = 1.71, SE = 0.09, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 1.51 to 1.89) such that individuals with SAD used significantly more safety behaviors compared to individuals without SAD (this mirrors the effect found in the analysis for H1). We also found a significant effect for dating (B = 0.85, SE = 0.09, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.67 to 1.01) such that more safety behaviors were used on dates (estimated M = 4.10) compared to other social interactions (estimated M = 2.40). Finally, we found a significant Diagnosis × Dating interaction effect (B = 0.40, SE = 0.09, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.21 to 0.58) such that the difference between safety behaviors in dates compared to other interactions was greater among individuals with SAD (estimated difference = 2.50) compared to individuals without SAD (estimated difference = 0.90). Fig. 1 presents this interaction.

To further probe this interaction, we examined the effect of dating for individuals with and without SAD separately. We found that for individuals with SAD the effect of dating was significant (B = 1.26, SE = 0.16, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.96 to 1.57), and for individuals without SAD the effect of dating was also significant (B = 0.44, SE = 0.10, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.23 to 0.63). Thus, dating was associated with increased safety behavior use but the effect was greater in magnitude (approximately three-fold) among individuals with SAD (see Fig. 1).

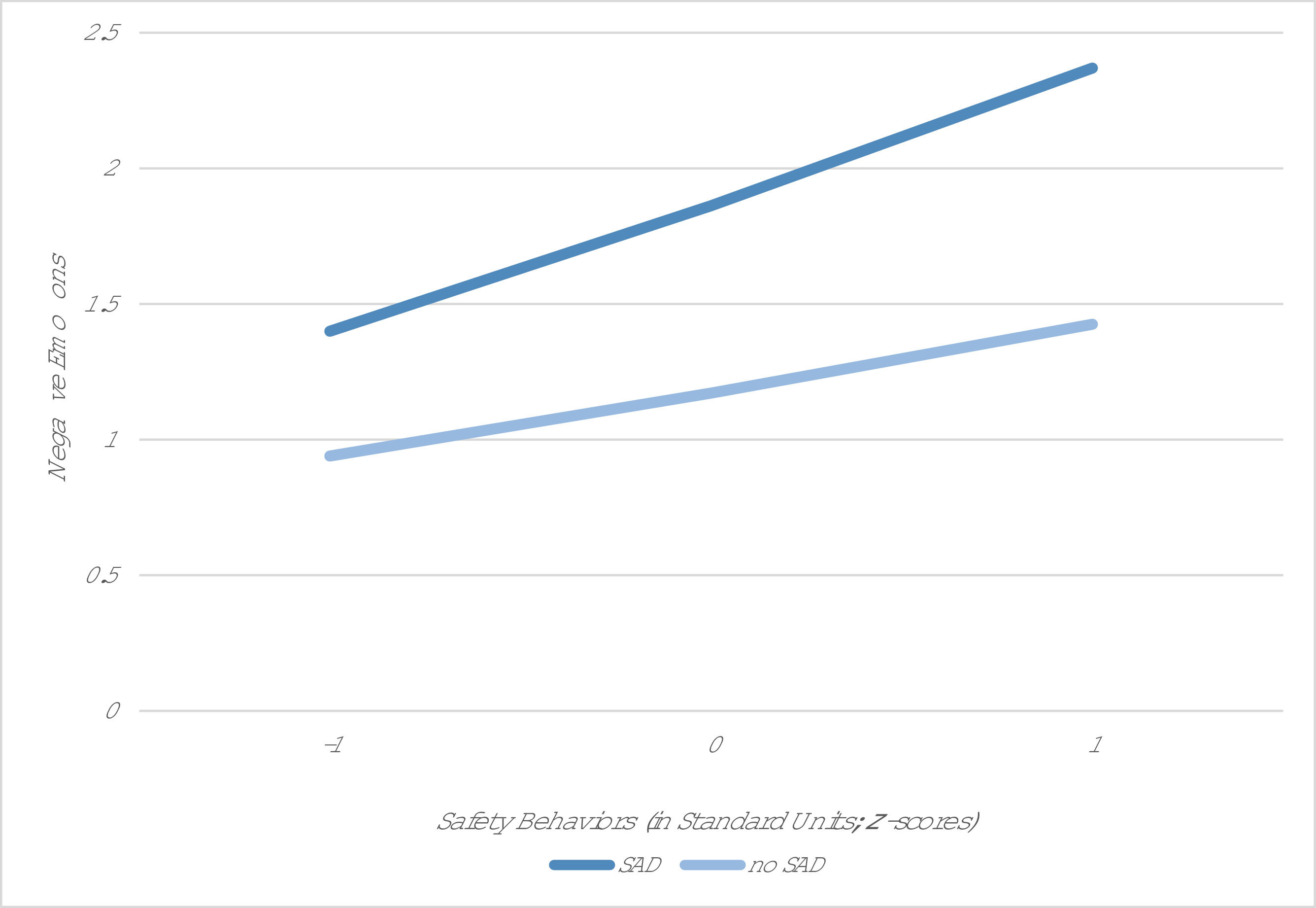

Hypothesis 3 – safety behavior use and negative emotions in SADWe examined an HLM model with diagnosis (SAD vs. no SAD; a dichotomous level 2 variable), safety behaviors in dates (a continuous level 1 variable), and their cross-level interaction as independent variables. The dependent variable was negative emotions in dates (a continuous level 1 variable). We found a significant effect for diagnosis (B = 0.23, SE = 0.08, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.08 to 0.36) such that individuals with SAD reported more negative emotions in dates (estimated M = 1.40) compared to individuals without SAD (estimated M = 0.94). We also found a significant effect for safety behaviors in dates (B = 0.09, SE = 0.02, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.06 to 0.11) such that more safety behavior use was positively associated with negative emotions. Finally, we found a significant Diagnosis × Safety behaviors in dates interaction effect (B = 0.03, SE = 0.01, p = .005, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.01 to 0.05) such that safety behaviors in dates were positively associated with negative emotions, and this association was stronger for individuals with SAD.

To further probe this interaction, we examined the effect of safety behaviors in dates for individuals with and without SAD separately. We found that for individuals with SAD the effect of safety behaviors was significant (B = 0.11, SE = 0.02, p < .001, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.07 to 0.15), and for individuals without SAD the effect of safety behavior was also significant (B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, p = .004, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = 0.01 to 0.11). Thus, safety behaviors were associated with increased negative emotions for both groups but the effect was greater in magnitude (approximately two-fold) among individuals with SAD (see Fig. 2).

Exploratory analysis – safety behavior use and positive emotions in SADWe examined an HLM model with diagnosis (SAD vs. no SAD; a dichotomous level 2 variable), safety behaviors in dates (a continuous level 1 variable), and their cross-level interaction as independent variables. The dependent variable was positive emotions in dates (a continuous level 1 variable). We did not find a significant effect for diagnosis (B = −0.07, SE = 0.08, p = .285, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = −0.22 to 0.10), nor a significant effect for safety behaviors (B = −0.01, SE = 0.02, p = .548, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = −0.05 to 0.05), nor a significant interaction effect (B = −0.01, SE = 0.01, p = .406, 95 % Bootstrapped CI = −0.03 to 0.01).

DiscussionIn the present study, we examined safety behaviors during dates/romantic interactions among individuals with (n = 54) and without SAD (n = 54). More specifically, participants completed a 21-day daily diary assessment focusing on dates and romantic interactions, as well as on concomitant safety behaviors and emotions. We found that both individuals with and without SAD used more safety behaviors during dates compared to during other social interactions, with this effect being greater for individuals with SAD compared to individuals without SAD. In addition, we found that safety behaviors during dates were associated with increased negative emotions, and this association was stronger for individuals with SAD compared to those without SAD. Interestingly, no significant association was found between safety behaviors during dates and positive emotions.

According to our first hypothesis, we found that individuals with SAD used more safety behaviors compared to individuals without SAD. This is consistent with both theoretical models of SAD (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995) as well as with empirical examinations (e.g., Oren-Yagoda et al., 2024; and see Piccirillo et al., 2016 for a review). Although this finding is not specifically related to dates/romantic interactions and is broader in scope (safety behaviors during social interactions in general), it serves as a replication of previous findings. This replication enhances our confidence in the findings and their validity, and is important in clinical psychological science (Open Science Collaboration, 2015).

According to our second hypothesis, we found that the elevated use of safety behaviors during dates compared to other interactions, is greater among individuals with SAD compared to individuals without SAD. This is consistent with previous studies that found dates to be especially anxiety-provoking for individuals with SAD (e.g., Asher & Aderka, 2020; Chen et al., 2023; MacKenzie & Fowler, 2013). Thus, it is possible that due to their heightened fear of evaluation (e.g., Weeks et al., 2024), their negative self-perception (e.g., Moscovitch et al., 2009), and due to dates being an evaluation of who one is as a person, individuals with SAD may become exceedingly anxious and resort to using safety behaviors in order to reduce this elevated anxiety (Piccirillo et al., 2016).

The use of safety behaviors, despite its intention to reduce anxiety, can have a diverse set of unintended negative interpersonal consequences. For instance, using safety behaviors has been found to reduce one’s authenticity and to result in lower levels of partners’ desire for future interaction (Plasencia et al., 2016). Moreover, it is possible that safety behaviors also negatively affect interaction partners’ authenticity in a negative way (in addition to the individual with SAD) and this can also contribute to rejection or negative responses (Asher & Aderka, 2021). Thus, individuals with SAD can use safety behaviors as an attempt to regulate elevated anxiety, but these safety behaviors may inadvertently interfere with relationship-building processes. Safety behaviors can also lead to negative interpersonal consequences via cognitive processes. For instance, one characteristic of safety behaviors is that when used, success is typically attributed to the safety behavior whereas failure, rejection and other negative outcomes are attributed to the self (Piccirillo et al., 2016). Thus, when one uses safety behaviors, a successful date may be attributed to those behaviors (“It only went well because I prepared many topics for conversation in advance”), whereas an unsuccessful date is attributed to the self (“I’m terrible at dates, no one will ever be with me”). This cognitive process can result in individuals with SAD generally feeling negative on and after dates, regardless of the nature of the interaction. This can have important negative interpersonal consequences for relationship development.

According to our third hypothesis, use of safety behaviors was associated with elevated negative emotions, but the effect was significantly stronger (twice as large) for individuals with SAD compared to those without SAD. This finding is in line with previous studies that found safety behavior use to be associated with increases in negative emotions. For instance, use of safety behaviors during a speech task was associated with increased negative affect following that task (Moscovitch et al., 2013), and increasing the use of safety behaviors led to increases in anxiety (Langer & Rodebaugh, 2013). Our findings align with these previous studies but demonstrate that the safety behaviors-negative emotions link is not limited to lab-based studies, and is also found in naturalistic contexts as part of participants’ daily lives.

One possible reason for the larger negative effect of safety behaviors among individuals with SAD may be related to experiential avoidance (i.e., the desire to avoid or reduce negative emotions). Specifically, when anxiety is low to moderate as may be the case during dates of individuals without SAD, safety behaviors may not reflect an experiential avoidance stance toward anxiety but rather a more adaptive strategy. For instance, individuals may perceive safety behavior use as a way to contribute to dates and improve their experience of dates. However, for individuals with SAD, dates can be extremely anxiety-provoking and threatening, and it is more likely that under such conditions, safety behaviors would serve an experiential avoidance role and represent attempts to avoid or fight anxiety. In these cases, negative emotions may be more likely to follow safety behaviors because attempting to suppress or fight emotions has been found to increase those very emotions (Dryman & Heimberg, 2018). An example of this could be asking a dating partner a question about themselves. If the intent or motivation behind the question is to get to know the dating partner better, then it is not considered a safety behavior and is not likely to increase negative emotions. However, if the intent or motivation behind the question is to deflect attention from the self because revealing personal information is too anxiety-provoking, then it is likely a safety behavior that could increase subsequent negative emotions.

Our findings also suggest that using safety behaviors may lead to broader increases in negative emotions rather than to increases limited to anxiety. For instance, safety behaviors could potentially lead to increases in shame. Individuals with SAD commonly use safety behaviors to hide parts of themselves that they are ashamed of (e.g., hiding one’s trembling hands so as not to appear anxious and “weak”). Thus, using safety behaviors may inadvertently result in a heightened self-focus on one’s shortcomings or inferiority (Leigh et al., 2021) thus increasing shame (Swee et al., 2021). Another potential emotional consequence of safety behavior use could be increased loneliness. Specifically, using safety behaviors to hide one’s self from others can lead one to feel distant from others, and can serve as a barrier to social connection (Plasencia et al., 2016). This may lead to enhanced loneliness (Oren-Yagoda et al., 2022). Importantly, these pathways represent possible pathways between safety behaviors and specific negative emotions, and future research is needed to directly examine such pathways in order to derive firm conclusions.

We found that safety behavior use was not significantly associated with positive emotions. This null finding may seem at odds with a recent study that found reductions in positive emotions following use of safety behaviors in interpersonal interactions (Oren-Yagoda et al., 2024). However, it is important to note that the negative relationship between safety behaviors and positive emotions reported in Oren-Yagoda et al. (2024), was found when examining social interactions in general rather than dates/romantic interactions more specifically as in the present study. In addition, most participants in Oren-Yagoda et al. (2024) were in a romantic relationship at the time of the study, whereas the present study included only individuals who were not in a relationship and were actively seeking one. Finally, Oren-Yagoda et al. (2024) conducted two sets of analyses: one with social anxiety as dichotomy (SAD vs. no SAD) and one with social anxiety as a continuum of severity. The negative relationship between safety behaviors and positive emotions was only found in the continuous analyses but not the grouped analyses. Thus, all these factors could have potentially contributed to the different findings in the present study compared to Oren-Yagoda et al. (2024). Future studies are needed to clarify the associations between safety behaviors and positive emotions in dating contexts.

Our findings have several clinical implications. First, they emphasize the importance of considering social context in treatment, as individuals (both with and without SAD) tend to engage in more safety behaviors during dates than in other social interactions. Specifically, inquiring about the safety behaviors used in dating contexts and helping clients to become aware of their safety behaviors during dates may represent an important first step in reducing or dropping such behaviors. Second, our findings can enhance psychoeducation about safety behaviors in dating contexts. For instance, therapists can explain to clients how using safety behaviors can increase negative emotions and could inadvertently hinder relationship development. This can serve as a powerful rationale for dropping safety behaviors. Therapists can also suggest that dropping safety behaviors may not necessarily lead to immediate positive emotions and this can contribute to setting realistic expectations and to focusing on the long-term benefits of reducing avoidance and facilitating social engagement. Third, our findings can inform targeted interventions for dating contexts. For instance, our findings stress the importance of addressing safety behaviors when planning exposures during dates. The ubiquity of safety behaviors in dating contexts suggests that simply conducting exposures without identification and reduction of safety behaviors may be insufficient to reduce social anxiety in these contexts.

The present study has a number of limitations. First, we assessed safety behaviors quantitatively without examining the specific content of these behaviors. Future studies could explore whether individuals with and without SAD use qualitatively different safety behaviors. In addition, future studies can utilize additional items focusing on other impression management or avoidance strategies to conduct a broader assessment of safety behaviors. Third, our sample consisted of young, primarily heterosexual individuals, so further study is needed to determine if these findings apply to older adults and individuals with a wider range of sexual orientations. For instance, age has been found to affect dating preferences and dating-related self-presentation (Davis & Fingerman, 2016; Schwarz & Hassebrauck, 2012). Fourth, our daily diary study relied on self-report measures. While self-report is essential for capturing the subjective nature of safety behaviors and emotional experiences, future studies could incorporate physiological or behavioral measures to complement self-report data. Fifth, in cases with multiple dates, we did not assess whether individuals dated the same individual multiple times or dated different individuals. Future studies can examine this to increase our knowledge on dating in SAD. Sixth, as with any study with repeated measurements, it is possible that the measurement itself influenced individuals’ actual behavior or their reporting about their behavior over the course of the study to a certain extent.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first to examine safety behaviors during dates/romantic interactions of individuals with SAD. Our daily diary design allowed for an examination of dates/romantic interactions in participants daily lives which contributed to external/ecological validity. The findings stress the importance of the unique context of dates, and the effect that dates can have on both safety behavior use and negative emotions of individuals with SAD. Our findings may be used to inform treatment interventions that focus on dates/romantic interactions in SAD.

The authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

This study did not receive grant funding.

This study received ethics approval by the IRB at the University of Haifa (365/22).

The design, hypotheses, and analysis plan of the present study were preregistered (https://osf.io/t9mcv?view_only=2f6ac3d564344895a82df778820ca1fa).

The data used in the analyses, a codebook to ensure all variables are clearly understood, and the code for conducting all the analyses are available online (https://osf.io/xeqjp/?view_only=42e5ba8f33ab48528d7c1698b3259343).