Empathizing and systemizing abilities are respectively associated with key developmental outcomes like intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits, particularly in typically developing (TD) children. However, how specific cognitive styles—defined by the balance between empathizing and systemizing—relate to these outcomes remains unclear.

MethodsWe conducted a latent profile analysis on 502 TD children aged 6‒12 years to identify cognitive styles based on multiple dimensions of empathizing and systemizing, measured by the Children's Empathy Quotient and Systemizing Quotient. Intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits were assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Fourth Edition), the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function, and the Social Responsiveness Scale, respectively.

ResultsFour cognitive styles emerged: High B (high empathizing and systemizing), E-dominance (empathizing-dominant), S-dominance (systemizing-dominant), and Low B (low empathizing and systemizing). The High B and E-dominance groups showed higher full-scale intelligence and verbal comprehension scores compared to the Low B group. In executive function, the Low B and S-dominance groups displayed more impairments, particularly in inhibitory control, emotional regulation, and overall executive function. For autistic traits, the S-dominance group showed higher levels of both social-communication difficulties and autistic mannerisms, while the Low B group primarily displayed increased social-communication challenges.

ConclusionCognitive styles marked by high empathizing and systemizing ability correlate with stronger intelligence and social-communication skills, while a systemizing-dominant profile may lead to executive function difficulties and elevated autistic traits. These findings emphasize the role of cognitive styles in developmental outcomes, with implications for tailored educational and clinical interventions.

Cognitive development in children is influenced by various factors, including cognitive styles, which shape how individuals perceive and process information(Kozhevnikov, 2007). One framework for understanding these cognitive styles is the empathizing–systemizing (E-S) theory(Baron-Cohen, 2009). Empathizing (E) refers to the ability to identify and respond to the emotions and mental states of others, while systemizing (S) is the drive to analyze and construct rule-based systems(Baron-Cohen, 2009, 2010; Baron-Cohen & Lombardo, 2017). These two major cognitive dimensions are generally thought to be normally distributed across the population and function independently of each other (Baron-Cohen, 2010).

An individual's cognitive style can be described by the empathizing-systemizing difference (D score) rather than by each dimension alone. The D score categorizes individuals into five cognitive brain types: Extreme Type E (where empathizing is much greater than systemizing), Type E (empathizing is slightly greater than systemizing), Type B (balanced, where empathizing equals systemizing), Type S (systemizing is slightly greater than empathizing), and Extreme Type S (systemizing is much greater than empathizing) (Baron-Cohen & Belmonte, 2005). Understanding the association between these cognitive styles and developmental outcomes is critical for identifying the cognitive patterns that may underlie certain abilities and challenges in children.

Three critical developmental outcomes—intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits—are particularly relevant to both empathizing and systemizing. Prior research suggests that both empathizing and systemizing might be associated with distinct facets of each of these three outcomes. First, previous studies suggest that empathizing and systemizing may influence intelligence. Extreme Type S individuals tend to excel in tasks requiring analytical reasoning (Qin & Zhang, 2024), while empathizing is associated with social intelligence and verbal skills (Svedholm-Häkkinen & L1indeman, 2016). A meta-analysis further supports a positive link between analytical thinking and intelligence (Alaybek et al., 2021). Second, existing studies indicate that different aspects of empathizing and systemizing may be linked to specific executive function components. For instance, affective empathy appears closely related to inhibitory control, suggesting that emotional self-regulation is essential for experiencing affective empathy(Yan et al., 2020). Additionally, both systemizing and executive function involve recognizing patterns and adhering to rule-based systems, particularly among children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Cascia & Barr, 2020). Third, the D score is strongly associated with autistic traits. An extreme imbalance between empathizing and systemizing—particularly high systemizing paired with low empathizing—has been also suggested as a potential cognitive marker for ASD(Baron-Cohen, 2010). Research shows that the D score positively correlates with autistic traits, including social-communication difficulties and restricted repetitive behaviors, in both ASD and typically developing (TD) children (Pan et al., 2022). This suggests that examining cognitive styles could help identify subclinical autistic traits within the general population.

Although intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits are distinct domains, they often intersect and overlap one another (Failla et al., 2024). For instance, a strong systemizing drive may enhance analytical intelligence and specific executive function skills, such as working memory (Goldstein & King, 2021). However, if systemizing is paired with lower empathizing, it may also correspond to more pronounced autistic traits (Baron-Cohen, 2009). In contrast, individual with a balanced empathizing-systemizing profile (Type B) may perform well across multiple cognitive domains and display fewer autistic behaviors (Greenberg et al., 2024; Lai et al., 2012). Examining all three outcomes together provides researchers and practitioners with a broad, interconnected view of how E-S cognitive styles may influence a range of developmental trajectories. However, empathizing and systemizing are complex constructs with distinct subcomponents. Empathizing includes cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and social skills, while systemizing encompasses technical, abstract, organizational, and collectible systems(Wang et al., 2022). To better understand individual differences in cognitive tendencies, a refined E-S cognitive style that considers these subfactors is needed, offering a more nuanced view than the conventional approach which only based on the D score.

Previous research has refined the understanding of naturally occurring cognitive styles by using methods beyond the D score classification. For instance, Qin et al. applied a three-step latent profile analysis in a sample of Chinese undergraduate students aged 18 to 25 years, identifying five distinct E-S profiles: Disengaged, Empathizers, Navigating Systemizers, Technological Systemizers, and Self-declared All-rounders(Qin & Zhang, 2024). Similarly, a Finnish study of non-clinical volunteers aged 15 to 69 years found notable distinctions between individuals with high scores in both empathizing and systemizing and those with low scores in both(Svedholm-Häkkinen & Lindeman, 2016). This "High-High" group shared many strengths with individual's dominant in either empathizing or systemizing alone. These studies underscore the significance of methodological approaches when classifying cognitive styles and examining their associations with developmental outcomes. However, such associations remain insufficiently explored in childhood populations, where ongoing cognitive and neural development could offer further insights.

The present study aims to address this gap by investigating the associations between E-S cognitive styles and three key developmental outcomes—intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits—among children aged 6 to 12 years. Using a latent profile analysis (LPA) approach, we aim to identify distinct cognitive styles based on multiple domains of empathizing and systemizing and examine how these profiles relate to specific developmental outcomes. This study provides a more comprehensive understanding of the cognitive styles that may contribute to individual differences in children's intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits.

MethodsParticipantsThis study was based on a sample of TD children who participated in the Guangzhou Longitudinal Study of Children. The inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) children aged 6 to 12 years; (2) voluntary participation by both the child and their parents; (3) no diagnosis of neurodevelopmental or behavioral disorders (e.g., ASD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and learning disorder); (4) a Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) score above 70, measured using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV); (5) no severe visual or auditory impairments; and (6) no known genetic, chromosomal abnormalities, or hereditary diseases. In families with multiple eligible children, only the eldest child was selected for inclusion. Ultimately, 502 TD children who completed all assessments were included in the study.

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee for Biomedical Research at Sun Yat-Sen University (2018-No. 23) and South China Normal University (SCNU-BRR-2023–029). Informed consent was securely obtained from all parents or legal guardians prior to their child's participation in the study.

MeasuresDemographics informationA self-developed questionnaire completed by the parents was used to gather demographic data. This included the child's age (years), sex (male or female), only child (yes or no), maternal age (<35 or ≥35 years), paternal age (<35 or ≥35 years), maternal education level (lower education [primary, secondary, and high school] or higher education [university and above]), paternal education level (lower education [primary, secondary, and high school] or higher education [university and above]), and family income (<8000 RMB or >8000 RMB per month per person).

Empathizing, systemizing and cognitive style measurementThe Chinese version of the children's empathy quotient (EQ-C) and systemizing quotient (SQ-C) are parent-reported scales designed to evaluate empathizing and systemizing abilities in children aged 4 to 12 years. The assessment includes 45 items, with 23 items in the EQ-C and 22 items in the SQ-C. The EQ-C scale is composed of three dimensions: cognitive empathy, social skills, and affective empathy. The SQ-C scale consists of four dimensions: technical systems, abstract systems, organizational systems, and collectible systems. The total score ranges from 0 to 46 for the EQ-C and 0 to 44 for the SQ-C. Higher scores indicate stronger empathizing or systemizing traits. The Cronbach's α for the Chinese version of the EQ-C and SQ-C is 0.87 and 0.86, respectively(Wang et al., 2022).

We used the mean total EQ-C and SQ-C scores from a large sample validating the Chinese versions (EQ-C: 29.7 ± 7.9, SQ-C: 23.5 ± 8.3) to calculate the D score, which reflects the difference between empathizing and systemizing(Wang et al., 2022). The calculation formula is as follows E=observedtotalEQ(C)−meantotalEQ(C)oftheTDgroupthemaximumpossiblescoreforEQ(C),S=observedtotalSQ(C)−meantotalSQ(C)oftheTDgroupthemaximumpossiblescoreforSQ(C),Dsocre=S−E2. The D score is used to classify brain type into five categories based on the E-S theory: Extreme Type E (D < −0.166), Type E (−0.166 ≤ D < −0.029), Type B (−0.029 ≤ D < 0.034), Type S (0.034 ≤ D < 0.172), and Extreme Type S (D ≥ 0.172).

Considering the multiple dimensions within each scale, we used the LPA based on three subscales of EQ-C and four subscales of SQ-C to capture more detailed and nuanced information about cognitive style. LPA is a statistical methodology employed to identify distinct subgroups that share specific observable characteristics, leading to more accurate and representative classifications(Weller et al., 2020). We applied the maximum likelihood estimation method with 95 % confidence intervals calculated through 1000 non-parametric bootstraps. The best-fitting model was selected based on Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Consistent Akaike Information Criterion Integrated Complete-data Likelihood (CAIC) values, with lower values indicating a better fit(Weller et al., 2020). We began with one class, incrementally adding classes, and assessing model fit until the optimal number was identified. Entropy was also considered to measure the separation between classes, with values closer to one indicating clearer class distinctions, though potentially increasing the risk of overfitting. The Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) was used to compare model fits across different numbers of classes.

Intelligence measurementThe Chinese version of the WISC-IV was used to evaluate the children's intelligence. The assessment provided scores for the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI), Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI), Working Memory Index (WMI), Processing Speed Index (PSI), and FSIQ. The WISC-IV, designed for children aged 6 to 16 years, demonstrates strong reliability and validity, with a Cronbach's α coefficient of 0.96 for the full scale and a test-retest reliability of 0.91(Kaufman et al., 2006). Trained professionals administered the test following the guidelines in the instruction manual.

Executive function measurementThe Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) is a parent-reported questionnaire designed to assess executive functioning in children aged 6 to 18 years at home and school. It contains 86 items categorized into eight domains: inhibition, emotional control, initiation, working memory, planning/organization, organization of materials, and monitoring. The BRIEF is commonly summarized using three indices: the Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI), Metacognition Index (MI), and Global Executive Composite (GEC). The BRI measures the ability to manage behavior and emotions through appropriate inhibitory control, while the MI evaluates skills related to initiating, planning, organizing, and sustaining problem-solving in working memory. The GEC reflects the overall executive function, encompassing all eight subscales. Higher scores indicate greater impairment in executive function. The subscales (except initiation) and total scores show good internal consistency (≥0.74) and test-retest reliability (≥0.68) in Chinese children (Xiang et al., 2023).

Autistic trait measurementThe Chinese version of the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) is a parent-reported measure designed to assess the autistic traits of children aged 4 to 18 years over the past six months (Cen et al., 2017). The scale consists of 65 items divided into five dimensions: social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and autistic mannerisms. The first four dimensions assess social-communicative difficulties. Higher scores indicate more severe impairment. The Cronbach's α for the total scale in the Chinese version ranges from 0.87 to 0.92, demonstrating strong internal consistency.

Statistical analysisThe data were initially assessed for normality by evaluating skewness and kurtosis values outside the range of −1.5 to 1.5. Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations and compared via analysis of variance (ANOVA). For non-normally distributed data, medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) were presented and analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis tests. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and compared using the Chi-square test. Additionally, Bayesian inferential method was employed to analyze variables where no significant effects were found, providing a more nuanced interpretation of the data.

We explored the associations of cognitive styles with intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits using general linear models. The crude models included no covariates, while the adjusted models accounted for children's age, sex, only child status, maternal and paternal age, maternal and parental education levels, and family income. We also performed pairwise comparisons of intelligence, executive function, and autistic trait scores across cognitive styles, using the same covariate adjustments. To ensure robustness, Tukey's Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was applied for multiple comparison adjustments.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.0 (R Core Team, 2023). A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsIn our analysis, we observed significant decreases in both BIC and CAIC values from the 1-class to 4-class models, followed by increases from the 4-class to 10-class models (Supplemental Table 1). The 4-calss model had an Entropy value of 0.66 and a significant BLRT (P value = 0.01). Considering both statistical metrics and clinical interpretability(Kongsted & Nielsen, 2017), we identified the 4-class model as the optimal fit. Based on standardized scores across subscales, class 1 ("High B", 17.73 %) scored high on both EQ-C and SQ-C, class 2 ("E-dominance", 32.87 %) had higher EQ-C and lower SQ-C scores, class 3 ("S-dominance", 30.08 %) showed the opposite pattern, and class 4 ("Low B", 19.32 %) scored low on both EQ-C and SQ-C (Fig. 1).

Final latent profile analysis model of empathizing and systemizing (N = 502).

Abbreviations: EQ1, cognitive empathy; EQ2, social skill; EQ3, affective empathy; SQ1, technical systems; SQ2, abstract systems; SQ3, organize systems; SQ4, collectible systems; E, empathizing; S, systemizing; B, balance.

Demographic information and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age across all groups was similar, ranging from 8.29 to 8.44 years, with no statistically significant differences (P value = 0.860). However, significant differences were observed in sex distribution (P value < 0.001). Males were most prevalent in the S-dominance group (76.16 %) and least prevalent in the E-dominance group (36.36 %). The proportion of only child also differed significantly across the groups (P value = 0.030), with the highest percentage in the High B group (53.93 %) and the lowest in the Low B group (32.99 %). No significant differences were found between the groups in terms of parental age, parental education, and family income. Supplemental Table 2 presents the results of Bayesian analysis, which supports the null hypothesis for these nonsignificant variables, with low Bayes Factor (BF10 < 1/3) values indicating strong evidence for no difference(Heck et al., 2023). Additionally, posterior probabilities for the null hypothesis (P(H₀ | Data)) were high, reinforcing the absence of significant differences (Heck et al., 2023). The majority of children in the E-dominance group (92.12 %) had Extreme Type E/Type E, while S-dominance children were predominantly Extreme Type S/Type S (64.24 %). The High B and Low B groups showed more balanced distributions, with High B children having more Type B (37.08 %). Cognitive function, measured by FSIQ, VCI, and PRI, was significantly different across groups, with High B group showing the highest FSIQ (115.85 ± 13.19), and Low B group scoring the lowest (108.86 ± 12.85, P value < 0.001). In terms of executive function, Low B and S-dominance groups had significantly poorer performance on GEC (Low B: 55.12 ± 7.53; S-dominance: 54.11 ± 8.14) and MI (Low B: 58.65 ± 8.95; S-dominance: 56.36 ± 9.01, all P values < 0.001). Autistic traits, measured by SRS total scores, were significantly elevated in Low B (43.09 ± 9.96) and S-dominance (42.21 ± 9.58) compared to other groups (P value < 0.001).

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Total (N = 502) | High B (N = 89) | Low B (N = 97) | E-dominance(N = 165) | S-dominance (N = 151) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%)/mean (SD)/ median (IQR) | N (%)/mean (SD) / median (IQR) | N (%)/mean (SD) / median (IQR) | N (%)/mean (SD) / median (IQR) | N (%)/mean (SD) / median (IQR) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age (year) | 8.35 (1.60) | 8.35 (1.66) | 8.29 (1.51) | 8.30 (1.54) | 8.44 (1.69) | 0.860 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 270 (53.78 %) | 52 (58.43 %) | 43 (44.33 %) | 60 (36.36 %) | 115 (76.16 %) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 232 (46.22 %) | 37 (41.57 %) | 54 (55.67 %) | 105 (63.64 %) | 36 (23.84 %) | |

| Only child | 0.030 | |||||

| Yes | 209 (41.63 %) | 48 (53.93 %) | 32 (32.99 %) | 70 (42.42 %) | 59 (39.07 %) | |

| No | 293 (58.37 %) | 41 (46.07 %) | 65 (67.01 %) | 95 (57.58 %) | 92 (60.93 %) | |

| Maternal age (year) | 0.078 | |||||

| <35 | 452 (90.04 %) | 74 (83.15 %) | 87 (89.69 %) | 154 (93.33 %) | 137 (90.73 %) | |

| ≥35 | 50 (9.96 %) | 15 (16.85 %) | 10 (10.31 %) | 11 (6.67 %) | 14 (9.27 %) | |

| Paternal age (year) | 0.239 | |||||

| <35 | 383 (76.29 %) | 63 (70.79 %) | 71 (73.20 %) | 134 (81.21 %) | 115 (76.16 %) | |

| ≥35 | 119 (23.71 %) | 26 (29.21 %) | 26 (26.80 %) | 31 (18.79 %) | 36 (23.84 %) | |

| Maternal education level | 0.679 | |||||

| Lower education (primary, secondary and high school) | 29 (5.78 %) | 5 (5.62 %) | 7 (7.22 %) | 11 (6.67 %) | 6 (3.97 %) | |

| Higher education (university and above) | 473 (94.22 %) | 84 (94.38 %) | 90 (92.78 %) | 154 (93.33 %) | 145 (96.03 %) | |

| Paternal education level | 0.542 | |||||

| Lower education (primary, secondary and high school) | 54 (10.76 %) | 7 (7.87 %) | 13 (13.40 %) | 20 (12.12 %) | 14 (9.27 %) | |

| Higher education (university and above) | 448 (89.24 %) | 82 (92.13 %) | 84 (86.60 %) | 145 (87.88 %) | 137 (90.73 %) | |

| Family income (RMB/month/person) | 0.212 | |||||

| <8000 | 133 (26.49 %) | 19 (21.35 %) | 32 (32.99 %) | 47 (28.48 %) | 35 (23.18 %) | |

| ≥8000 | 369 (73.51 %) | 70 (78.65 %) | 65 (67.01 %) | 118 (71.52 %) | 116 (76.82 %) | |

| Brain type | <0.001 | |||||

| Type B | 121 (24.10 %) | 33 (37.08 %) | 31 (31.96 %) | 13 (7.88 %) | 44 (29.14 %) | |

| Extreme Type E/ Type E | 252 (50.20 %) | 35 (39.33 %) | 55 (56.70 %) | 152 (92.12 %) | 10 (6.62 %) | |

| Extreme Type S/ Type S | 129 (25.70 %) | 21 (23.60 %) | 11 (11.34 %) | 0 (0.00 %) | 97 (64.24 %) | |

| EQ-C | 27.37 (7.09) | 34.87 (4.45) | 21.26 (4.84) | 31.83 (3.71) | 21.99 (4.23) | <0.001 |

| EQ1-Cognitive empathy | 11.03 (3.13) | 13.89 (2.10) | 7.71 (2.25) | 12.72 (2.10) | 9.64 (2.23) | <0.001 |

| EQ2-Social skill | 10.01 (3.23) | 12.20 (2.61) | 9.45 (2.88) | 11.52 (2.30) | 7.42 (2.75) | <0.001 |

| EQ3-Affective empathy | 6.33 (2.79) | 8.78 (1.89) | 4.09 (2.22) | 7.59 (2.26) | 4.94 (2.15) | <0.001 |

| SQ-C | 18.93 (6.33) | 27.27 (4.00) | 11.54 (3.54) | 16.70 (3.77) | 21.21 (3.67) | <0.001 |

| SQ1-Technical systems | 5.23 (3.01) | 8.36 (2.60) | 2.80 (1.92) | 4.48 (2.55) | 5.75 (2.50) | <0.001 |

| SQ2-Abstract systems | 7.95 (2.60) | 9.91 (1.96) | 5.18 (2.29) | 7.82 (2.19) | 8.72 (1.94) | <0.001 |

| SQ3-Organize systems | 2.62 (2.09) | 4.85 (2.10) | 1.00 (2.00) | 2.05 (1.63) | 2.60 (1.88) | <0.001 |

| SQ4-Collectible systems | 3.13 (1.61) | 4.15 (1.22) | 1.98 (1.25) | 2.34 (1.33) | 4.13 (1.29) | <0.001 |

| Cognitive function | ||||||

| FSIQ | 113.24 (12.80) | 115.85 (13.19) | 108.86 (12.85) | 113.42 (13.12) | 114.31 (11.57) | <0.001 |

| VCI | 117.45 (14.84) | 120.20 (14.23) | 112.97 (17.47) | 118.07 (15.11) | 118.04 (12.38) | 0.006 |

| PRI | 112.20 (12.69) | 114.25 (13.70) | 109.45 (12.12) | 111.72 (12.43) | 113.29 (12.50) | 0.041 |

| WMI | 103.99 (13.29) | 105.08 (13.31) | 100.87 (13.22) | 104.04 (14.07) | 105.32 (12.21) | 0.058 |

| PSI | 102.82 (13.64) | 104.10 (15.82) | 100.57 (11.79) | 103.15 (14.10) | 103.17 (12.81) | 0.306 |

| Executive function | ||||||

| BRIEF a | ||||||

| GEC | 51.28 (8.35) | 45.00 (8.25) | 55.12 (7.53) | 46.00 (10.00) | 54.11 (8.14) | <0.001 |

| BRI | 46.00 (8.00) | 43.20 (5.97) | 48.62 (7.35) | 45.00 (8.00) | 48.00 (9.00) | <0.001 |

| MI | 53.88 (9.45) | 47.16 (7.72) | 58.65 (8.95) | 52.42 (8.60) | 56.36 (9.01) | <0.001 |

| Inhibit | 47.00 (11.00) | 44.32 (5.68) | 50.39 (8.04) | 46.23 (6.06) | 52.30 (9.30) | <0.001 |

| Shift | 47.00 (11.00) | 45.00 (9.25) | 49.33 (7.94) | 46.27 (7.42) | 48.00 (10.00) | <0.001 |

| Emotion control | 45.00 (12.25) | 42.50 (11.00) | 47.00 (11.25) | 51.02 (17.11) | 47.00 (11.00) | 0.002 |

| Initiate | 49.77 (8.87) | 44.84 (6.36) | 54.15 (9.09) | 48.73 (8.61) | 50.99 (8.70) | 0.001 |

| Working memory | 52.47 (9.44) | 46.42 (7.28) | 56.58 (9.99) | 51.33 (8.41) | 54.61 (9.32) | <0.001 |

| Plan/organize | 55.97 (10.23) | 49.80 (8.71) | 60.65 (9.84) | 54.68 (9.14) | 58.01 (10.43) | <0.001 |

| Organization | 51.98 (9.19) | 46.47 (9.22) | 54.40 (8.56) | 51.30 (9.16) | 54.40 (8.09) | <0.001 |

| Monitor | 55.96 (9.59) | 50.14 (8.96) | 60.46 (8.64) | 53.74 (9.01) | 58.92 (8.74) | <0.001 |

| Autistic traits | ||||||

| SRS | ||||||

| Total score | 37.42 (11.47) | 31.21 (11.12) | 43.09 (9.96) | 33.04 (10.64) | 42.21 (9.58) | <0.001 |

| Social-communicative difficulties | 32.85 (10.12) | 26.85 (9.69) | 38.74 (8.79) | 29.16 (9.53) | 36.64 (8.08) | <0.001 |

| Social awareness | 7.51 (2.37) | 6.20 (2.30) | 8.43 (2.16) | 7.07 (2.19) | 8.18 (2.27) | <0.001 |

| Social cognition | 8.63 (3.42) | 7.64 (3.12) | 10.01 (3.43) | 7.61 (3.42) | 9.45 (3.05) | <0.001 |

| Social communication | 10.13 (4.43) | 7.18 (4.29) | 12.40 (3.66) | 8.61 (3.99) | 12.06 (3.72) | <0.001 |

| Social motivation | 6.58 (3.17) | 5.83 (2.99) | 7.90 (3.20) | 5.88 (3.14) | 6.95 (2.98) | <0.001 |

| Autistic mannerisms | 4.56 (2.71) | 4.36 (2.92) | 4.00 (3.00) | 3.87 (2.32) | 5.57 (2.90) | <0.001 |

One child with missing data in the High B group and Low B group, respectively.

Abbreviations: FSIQ, full scale intelligence quotient; VCI, verbal comprehension index; PRI, perceptual reasoning index; WMI, working memory index; PSI, processing speed index; SRS, Social responsiveness scale; BRIEF, behavior rating scale of executive function; GEC, global executive component; BRI, behavioral regulation index; MI, metacognition index; E, empathizing; S, systemizing; B, balance; N, number; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2 shows the associations between cognitive styles and intelligence. In adjusted models, High B children had significantly higher FSIQ (β = 5.80, 95 % CI: 2.22, 9.39), VCI (β = 5.68, 95 % CI: 1.57, 9.79), and PRI (β = 4.08, 95 % CI: 0.43, 7.73) compared to the Low B group. E-dominance was also associated with higher FSIQ (β = 4.20, 95 % CI: 1.11, 7.29) and VCI (β = 4.87, 95 % CI: 1.33, 8.41). S-dominance group only showed higher FSIQ (β = 4.23, 95 % CI: 1.01, 7.45) in relative to the Low B group.

Associations between cognitive styles and intelligence in participants (N = 502).

| Variable | FSIQ | VCI | PRI | WMI | PSI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

| β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | |

| Cognitive styles (vs Low B) | ||||||||||

| High B | 7.00 ⁎⁎⁎ | 5.80 ⁎⁎ | 7.23 ⁎⁎ | 5.68 ⁎⁎ | 4.79 * | 4.08 * | 4.21 * | 3.19 | 3.53 | 3.41 |

| (3.36, 10.63) | (2.22, 9.39) | (3.01, 11.46) | (1.57, 9.79) | (1.16, 8.43) | (0.43, 7.73) | (0.41, 8.02) | (−0.61, 6.99) | (−0.39, 7.46) | (−0.51, 7.34) | |

| E-dominance | 4.57 ⁎⁎ | 4.20 ⁎⁎ | 5.10 ⁎⁎ | 4.87 ⁎⁎ | 2.27 | 2.15 | 3.17 | 2.85 | 2.58 | 2.02 |

| (1.40, 7.74) | (1.11, 7.29) | (1.42, 8.79) | (1.33, 8.41) | (−0.90, 5.43) | (−0.99, 5.30) | (−0.15, 6.49) | (−0.42, 6.13) | (−0.83, 6.00) | (−1.36, 5.40) | |

| S-dominance | 5.46 ⁎⁎ | 4.23 * | 5.07 ⁎⁎ | 3.09 | 3.84 * | 3.16 | 4.45 * | 3.27 | 2.60 | 3.24 |

| (2.23, 8.68) | (1.01, 7.45) | (1.32, 8.82) | (−0.59, 6.78) | (0.62, 7.06) | (−0.11, 6.44) | (1.08, 7.83) | (−0.14, 6.68) | (−0.88, 6.08) | (−0.28, 6.76) | |

All models were adjusted for children's age, sex, only child, maternal age, paternal age, maternal education level, paternal education level, and family income.

Abbreviations: FSIQ, full scale intelligence quotient; VCI, verbal comprehension index; PRI, perceptual reasoning index; WMI, working memory index; PSI, processing speed index; E, empathizing; S, systemizing; B, balance.

The associations of executive function were presented in Table 3. In adjusted models, High B and E-dominance groups were significantly associated with lower scores on the GEC (β = −9.37, 95 % CI: −11.59, −7.14; β = −5.72, 95 % CI: −7.63, −3.81), BRI (β = −5.26, 95 % CI: −7.27, −3.24; β = −4.01, 95 % CI: −5.75, −2.28), and MI (β = −11.14, 95 % CI: −13.67, −8.60; β = −6.30, 95 % CI: −8.48, −4.12) compared to the Low B group. The associations of cognitive styles with the eight subscales of BRIEF were shown in Supplemental Table 3 and Supplemental Table 4.

Associations between cognitive styles and executive function in participants (N = 500).

| Variable | GEC | BRI | MI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

| β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | |

| Cognitive styles (vs Low B) | ||||||

| High B | −9.65 ⁎⁎⁎ | −9.37 ⁎⁎⁎ | −5.42 ⁎⁎⁎ | −5.26 ⁎⁎⁎ | −11.49 ⁎⁎⁎ | −11.14 ⁎⁎⁎ |

| (−11.85, −7.45) | (−11.59, −7.14) | (−7.43, −3.41) | (−7.27, −3.24) | (−13.99, −8.99) | (−13.67, −8.60) | |

| E-dominance | −5.57 *** | −5.72 ⁎⁎⁎ | −3.78 ⁎⁎⁎⁎ | −4.01 ⁎⁎⁎ | −6.23 ⁎⁎⁎ | −6.30 ⁎⁎⁎ |

| (−7.48, −3.65) | (−7.63, −3.81) | (−5.53, −2.04) | (−5.75, −2.28) | (−8.40, −4.05) | (−8.48, −4.12) | |

| S-dominance | −1.02 | −0.36 | 1.04 | 1.67 | −2.29 * | −1.66 |

| (−2.96, 0.93) | (−2.35, 1.63) | (−0.74, 2.81) | (−0.13, 3.48) | (−4.50, −0.08) | (−3.94, 0.61) | |

All models were adjusted for children's age, sex, only child, maternal age, paternal age, maternal education level, paternal education level, and family income.

Abbreviations: GEC, global executive component; BRI, behavioral regulation index; MI, metacognition index; E, empathizing; S, systemizing; B, balance.

Adjusted models indicated that High B group had significantly lower total SRS scores (β = −12.05, 95 % CI = −15.03, −9.06) and social-communicative difficulties (β = −11.85, 95 % CI = −14.46, −9.24), but no association with autistic mannerisms (Table 4). E-dominant group was similarly associated with lower total SRS (β = −10.15, 95 % CI = −12.73, −7.58) and social-communicative difficulties (β = −9.62, 95 % CI = −11.86, −7.37). S-dominant group was linked to higher autistic mannerisms (β = 1.16, 95 % CI = 0.47, 1.85). The associations of cognitive styles with the four subscales of social-communicative difficulties were shown in Supplemental Table 5.

Associations between cognitive styles and autistic traits in participants (N = 502).

| Variable | SRS-Total score | Social-communicative difficulties | Autistic mannerisms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | Crude | Adjusted | |

| β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | β (95 % CI) | |

| Cognitive styles (vs Low B) | ||||||

| High B | −11.88 ⁎⁎⁎ | −12.05 ⁎⁎⁎ | −11.89 ⁎⁎⁎ | −11.85 ⁎⁎⁎ | 0.01 | −0.20 |

| (−14.84, −8.92) | (−15.03, −9.06) | (−14.48, −9.30) | (−14.46, −9.24) | (−0.75, 0.77) | (−0.97, 0.57) | |

| E-dominance | −10.06 ⁎⁎⁎ | −10.15 ⁎⁎⁎ | −9.58⁎⁎⁎ | −9.62⁎⁎⁎ | −0.48 | −0.54 |

| (−12.64, −7.48) | (−12.73, −7.58) | (−11.84, −7.32) | (−11.86, −7.37) | (−1.14, 0.18) | (−1.20, 0.12) | |

| S-dominance | −0.88 | −0.76 | −2.10 | −1.92 | 1.22 ⁎⁎⁎ | 1.16 ⁎⁎ |

| (−3.50, 1.74) | (−3.44, 1.92) | (−4.40, 0.20) | (−4.26, 0.42) | (0.55, 1.89) | (0.47, 1.85) | |

All models were adjusted for children's age, sex, only child, maternal age, paternal age, maternal education level, paternal education level, and family income.

Abbreviations: SRS, Social responsiveness scale; E, empathizing; S, systemizing; B, balance. *P value<0.05;.

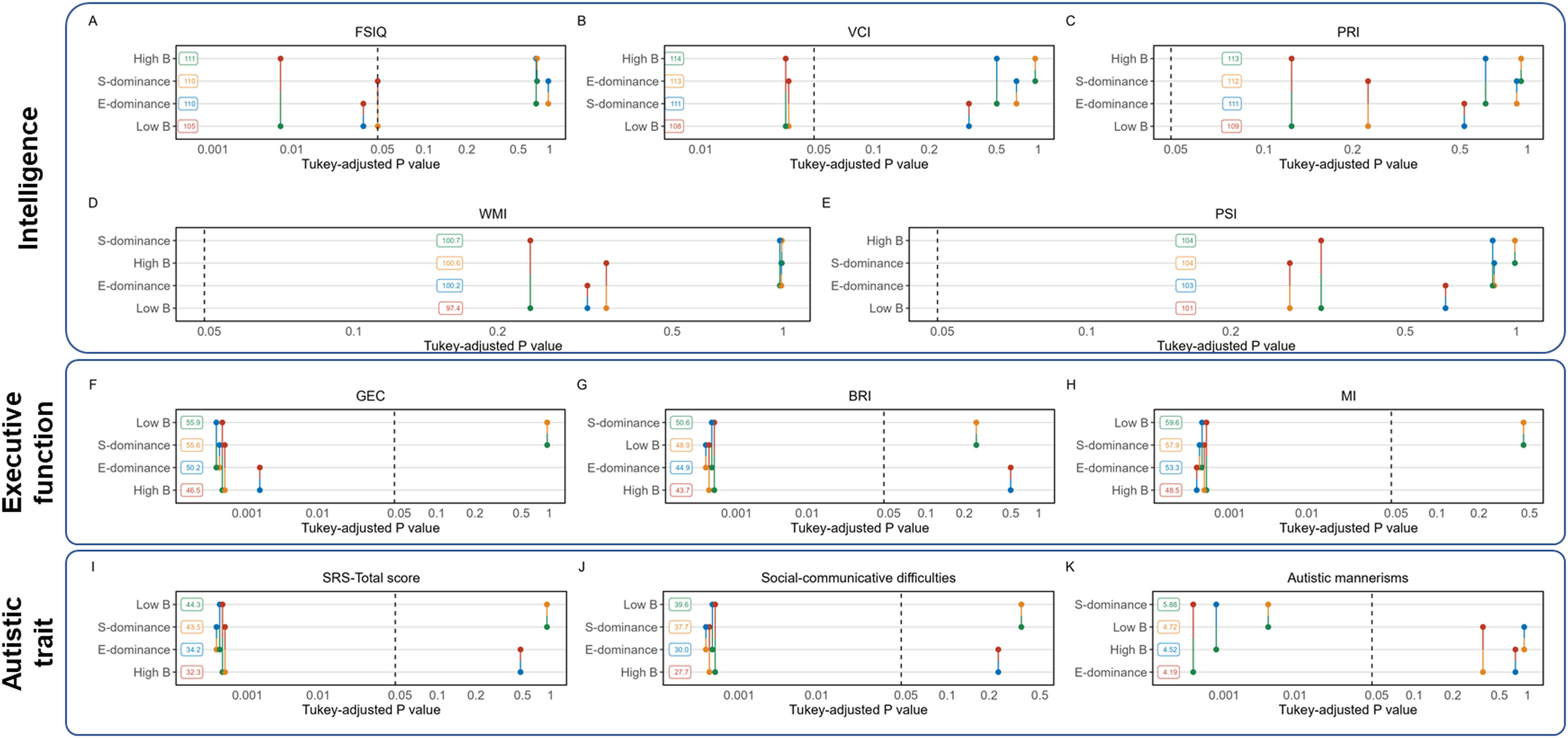

Fig. 2 presents the post-hoc pairwise comparisons of cognitive styles in adjusted models. High B and E-dominance groups had significantly higher FSIQ and VCI scores than Low B (Tukey-adjusted P values < 0.05), with no significant differences in PRI, WMI, or PSI. In terms of executive function, Low B and S-dominance groups performed worse in GEC, BRI, and MI compared to other groups, but there was no difference between these two (Tukey-adjusted P values < 0.05). For autistic traits, High B and E-dominance had lower SRS total scores and social-communicative difficulties than Low B and S-dominance (Tukey-adjusted P values < 0.05). S-dominance had higher autistic mannerisms score than the other groups, with no significant differences among the remaining groups.

Post-hoc pairwise P-value plots.

All models were adjusted for children's age, sex, only child, maternal age, paternal age, maternal education level, paternal education level, and family income.

Abbreviations: FSIQ, full scale intelligence quotient; VCI, verbal comprehension index; PRI, perceptual reasoning index; WMI, working memory index; PSI, processing speed index; SRS, Social responsiveness scale; BRIEF, behavior rating scale of executive function; GEC, global executive component; BRI, behavioral regulation index; MI, metacognition index; E, empathizing; S, systemizing; B, balance.

In this study, we used a latent profile analysis by considering the multi-dimensional nature of empathizing and systemizing to identify four distinct cognitive styles—High B, E-dominance, S-dominance, and Low B—and examined how these relate to intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits in TD children aged 6 to 12 years. We observed that High B and E-dominance groups scored higher in FSIQ and VCI, while Low B and S-dominance groups showed weaker executive function and higher social-communication difficulties. S-dominance group also exhibited more autistic mannerisms, with no significant differences among other groups. Our findings provide new insights into the complex interplay between cognitive styles and child development, shedding light on the underlying cognitive styles that may contribute to individual differences in intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits.

The four cognitive styles (i.e., High B, E-dominance, S-dominance, and Low B) identified in this study partially align with established E-S brain types (i.e., Extreme Type E/Type E, Extreme Type S/Type S, and Type B) from prior research based on D score(Baron-Cohen, 2009, 2010; Baron-Cohen & Belmonte, 2005). Comparisons between the classifications identified through LPA and classifications based on the D score show that each dominant style includes a higher proportion of individuals corresponding to the expected brain type, supporting the robustness of these findings. Unlike the brain type classifications based on the D score, our result distinguishes between two B styles: High B, with elevated levels of both empathizing and systemizing, and Low B, with lower levels of both traits. This distinction between High B and Low B aligns with previous latent profile analyses in non-clinical populations. For instance, Qin et.al identified two profiles resembling our findings: Self-declared All-rounders, who exhibit a balanced profile with higher levels of both empathizing and systemizing, and Disengaged individuals, who show lower levels of both traits(Qin & Zhang, 2024). Svedholm-Häkkinen and Lindeman found similar patterns, identifying the High-High group (comparable to our High B) with strengths in both cognitive domains, and the Low-Low group (similar to Low B) with weaker engagement in both areas(Svedholm-Häkkinen & Lindeman, 2016). These findings emphasize the importance of recognizing the complex relationship between empathizing and systemizing, which may be obscured by the D score classification.

Demographic analysis revealed that males were most prevalent in the S-dominance group and least represented in the E-dominance group, aligning with previous research showing that males generally exhibit a stronger tendency and higher performance in systemizing compared to females(Kidron et al., 2018). We also observed that the proportion of only child was highest in the High B group (53.93 %) and lowest in the Low B group (32.99 %). This difference suggests that only child may experience unique social and cognitive influences that shape their cognitive style. More focused parental attention and resources, as well as frequent one-on-one adult interactions, might foster only child cognitive flexibility and social skills, supporting adaptability in tasks requiring both empathizing and systemizing skills(Chen et al., 2024; Falbo & Polit, 1986; Guryan et al., 2008; Razza et al., 2024). Additionally, Bayesian inference analysis revealed no significant differences in parental age, parental education, and family income across cognitive styles. This result implies that variations in cognitive style might be shaped more by intrinsic, individual characteristics (e.g., personality traits, neurodevelopmental factors) or specific social experiences not captured by socioeconomic status. These findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of cognitive style, emphasizing the need to consider a complex interaction of individual and situational factors.

Our results revealed significant associations between cognitive styles and intelligence measures. The High B group showed the highest overall intelligence scores, specifically in FSIQ, VCI, and PRI. Children in the E-dominance group also demonstrated higher FSIQ and VCI scores compared to the Low B group, though this advantage was less pronounced than in the High B group. These findings align with prior research suggesting that individuals who are more empathetic tend to have higher social intelligence(Hetemi et al., 1977). Previous studies also indicated that empathy, especially cognitive empathy, significantly influences verbal comprehension and language learning(Hui et al., 2024; Sanahuges & Curell, 2020). It enhances syntactic complexity, and sensitivity to intonation, and modulates brain activity during sentence processing(Casillas et al., 2023; Li et al., 2014). Additionally, previous research indicates high systemizing ability is linked to a focus on local details and specific brain activations during perceptual tasks(Billington et al., 2008). Interestingly, while the S-dominance profile was associated with higher FSIQ relative to the Low B group, its association on specific cognitive subdomains such as VCI and PRI was less robust, reflecting prior observations that systemizing may benefit certain types of analytical reasoning but may not be as closely linked to verbal or perceptual reasoning. This difference supports the notion that high empathizing, either alone or combined with strong systemizing, may offer an advantage in verbal and perceptual reasoning abilities in children. The cognitive strengths observed in the High B profile may suggest that balanced cognitive tendencies, or high empathizing and systemizing abilities together, facilitate flexible and comprehensive problem-solving approaches across various domains of intelligence.

Our study identified significant differences in executive function across cognitive styles, with notably poorer executive function in the Low B and S-dominance groups. These groups showed elevated scores on the GEC, BRI, and MI scales, indicating greater impairments in overall executive function, particularly in inhibitory control and emotional self-regulation. These findings underscore the potential role of empathizing tendencies in enhancing executive function, as empathy may contribute to improved emotional regulation and social interactions(Yan et al., 2020). Prior research has shown that specific aspects of empathy relate to different executive functions, such as working memory's association with mentalizing and interpersonal concern, and the link between inhibition and mentalizing(Mairon et al., 2023). Additionally, the weaker executive function observed in the S-dominance group may reflect an analytic focus characteristic of high systemizing, which, while beneficial for logical reasoning(Billington et al., 2008), may limit the flexible self-regulatory skills essential for managing emotions and adapting to complex social situations.

Our analysis indicates that children with an S-dominance profile exhibit more pronounced social-communication difficulties and autistic mannerisms, while children with a Low B profile primarily show higher social-communicative difficulties relative to the High B and E-dominance groups. This aligns with previous findings that an extreme imbalance favoring systemizing over empathizing, reflected in a high D score, may signal autistic traits within TD populations(Ghim et al., 2011; Greenberg et al., 2018; Grove et al., 2013; Pan et al., 2022). The High B and E-dominance profiles, characterized by stronger empathizing abilities, seem to confer advantages in social understanding and interaction, potentially leading to more effective communication, heightened sensitivity to social cues, and deeper social connections(Eisenberg & Miller, 2023; Maliske et al., 2009, 2014, 2023). These traits appear to mitigate social-communicative challenges often linked to autistic traits. However, the S-dominance group's tendency toward systemizing—emphasizing rule-based, detail-oriented thinking—may contribute to behaviors associated with autistic mannerisms, such as repetitive actions and restricted interests(Baron-Cohen, 2010; Baron-Cohen & Lombardo, 2017). Their focus on systems and routines over social engagement may also reduce opportunities for social skill development, further reinforcing autistic mannerisms relative to the other groups. These findings suggest that cognitive styles may serve as valuable indicators for designing targeted interventions to support both social and cognitive development in children exhibiting different levels of autistic traits.

Overall, our results suggest that E-S cognitive styles relate to a spectrum of developmental outcomes in interconnected ways. Children with a stronger drive to empathize generally show higher verbal reasoning scores and more effective executive control, possibly reflecting enhanced emotional regulation and social awareness. Elevated systemizing, meanwhile, often corresponds to greater analytical and rule-based skills, aligning with theories highlighting the advantages of system-focused thinking in specific cognitive tasks(Escovar et al., 2016; Hughes et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2012). When systemizing substantially exceeds empathizing, however, this imbalance is associated with higher autistic traits, consistent with perspectives suggesting that lower empathizing may correspond to social-communication challenges(Baron-Cohen, 2008; Sindermann et al., 2019; van der Zee & Derksen, 2021). Examining intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits together provides a broader view of how different E-S profiles may underlie both cognitive strengths and social-behavioral difficulties in TD children.

Research and clinical implicationsThese findings highlight the value of examining E-S cognitive styles through data-driven methods (e.g., latent profile analysis), rather than relying exclusively on D score categories. Previous D score-based approaches did not subdivide the B type(Hendriks et al., 2022; Lasmono et al., 2022; Zheng, 2023), potentially masking important differences among children who appear to have balanced E-S tendencies. Our results reveal that High B involves relatively strong empathizing and systemizing, whereas Low B involves lower abilities in both domains. Recognizing this distinction is critical for understanding the diverse ways in which E-S cognitive styles manifest in TD children.

From a research perspective, differentiating High B from Low B refines the broader E-S framework by illustrating that even balanced children may vary in their levels of empathizing and systemizing. This insight encourages more focused investigations into how these subgroups respond to various academic, social, or clinical contexts. Future studies could also explore whether these two B subtypes diverge in their developmental trajectories or respond differently to social-cognitive interventions.

Clinically, distinguishing High B and Low B underlines the need for tailored support. Children classified as Low B may benefit from programs that systematically build both empathizing and systemizing skills, while High B children might require more specialized strategies to leverage their existing strengths in both areas. By recognizing that a single B type designation may overlook subtle but meaningful distinctions, practitioners can improve assessment, educational planning, and clinical interventions for children who fall into this balanced category.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. First, our sample only consisted of TD children, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Future research should aim to replicate these results in more diverse populations and include children with neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ASD, to further explore the relevance of cognitive styles in clinical contexts. Additionally, while the study's LPA approach allowed for the identification of distinct cognitive styles, longitudinal data would provide greater insights into how these cognitive styles might change over time and impact developmental trajectories. Future research might also consider examining environmental factors, such as parenting style, adverse childhood experience, and educational environment, that could interact with cognitive styles to influence developmental outcomes. Additionally, neurobiological studies could help elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking cognitive styles, intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits, potentially revealing neural correlates associated with each style.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study provides evidence for the association of distinct cognitive styles, defined by multiple dimensions of empathizing and systemizing, with intelligence, executive function, and autistic traits among TD children. Our findings suggest that cognitive styles characterized by high empathizing and systemizing abilities (High B) are associated with stronger intelligence and executive function, while styles dominated by systemizing (S-dominance) are linked to greater autistic traits and executive function difficulties. These insights enhance our understanding of how cognitive styles can shape developmental outcomes, offering potential applications in educational and clinical settings to support individual differences in cognitive, executive function, and social-emotional development.

Statements and declarationsEthics approval and consent to participate: This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee for Biomedical Research at Sun Yat-Sen University (2018-No. 23) and South China Normal University (SCNU-BRR-2023–029). Informed consent was securely obtained from all parents or legal guardians prior to their child's participation in the study.

Availability of data and materials: Raw data supporting this study are available upon reasonable request. Interested parties may contact the corresponding authors to discuss potential collaboration.

Funding/supportThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52400247, 82103794), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M750966), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20240522), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515110220, 2022B1515130007), Youth Foundation of South China Normal University (23KJ14), Guangdong University Featured Innovation Program Project (2024WTSCX052), Guangdong University Young Innovative Talents Program Project (2024KQNCX061), Ministry of education of Humanities and Social Science Project (24YJC190032), Autism Research Special Fund of Zhejiang Foundation For Disabled Persons (2024006), National Social Science Foundation of China (20&ZD296), and Striving for the First-Class, Improving Weak Links and Highlighting Features (SIH) Key Discipline for Psychology in South China Normal University.

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the parents and children for their valuable time and effort in participating in this research.

These authors contributed equally and should be listed as the corresponding author.

Li-Zi Lin, Joint International Research Laboratory of Environment and Health, Ministry of Education, Guangdong Provincial Engineering Technology Research Center of Environmental Pollution and Health Risk Assessment, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510080, China.