Executive dysfunction in schizophrenia profoundly impairs functional outcomes and remains insufficiently addressed by standard pharmacological treatments. While computerized cognitive training offers promise, traditional evaluation methods often fail to capture nuanced improvements along the psychosis-health continuum. This study aims to quantify executive function (EF) profile changes following working memory training and identify robust baseline predictors of treatment response.

MethodsNinety-four schizophrenia patients were randomized to adaptive N-back training (n = 32), non-adaptive 1-back control (n = 33), or treatment-as-usual (n = 29). EF was assessed across working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control domains. A support vector machine classifier, trained on an independent sample (195 patients, 169 controls) and calibrated via Platt scaling, quantified EF profile changes. An exploratory framework based on Granger causality principles identified baseline treatment predictors.

ResultsAdaptive training produced significant near-transfer effects on untrained working memory tasks and reduced general psychopathology (pfdr < 0.05), but no far-transfer effects to other EF domains. The probability of neurotypical EF classification increased substantially in the adaptive group (13.21 % to 38.79 %, p < 0.001), correlating with symptom reduction. Working memory maintenance and response inhibition emerged as the most robust baseline predictors of treatment response.

ConclusionsWorking memory training induces meaningful shifts in EF profiles in schizophrenia, promoting movement along the psychosis-health continuum toward neurotypical functioning. The classifier-based approach provides a more refined assessment compared to traditional binary measures, while the exploratory framework identifies specific EF domains predicting treatment response with potential causal relevance. These findings warrant validation through larger, multi-center trials with extended follow-up periods.

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder characterized by positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations and delusions), negative symptoms (e.g., diminished emotional expression and social withdrawal), and pervasive cognitive deficits that collectively impair daily functioning and quality of life (McCutcheon et al., 2020). Among the affected cognitive domains, executive function (EF) deficits are particularly problematic due to their strong association with poor functional outcomes, such as impaired social relationships and occupational achievement (Bowie et al., 2006; Kurtz et al., 2008; Puig et al., 2008). EF impairments hinder goal-directed behavior and contribute to aggression, violence, poor treatment adherence, and medication noncompliance, ultimately worsening clinical outcomes (Orellana & Slachevsky, 2013). Therefore, ameliorating EF deficits represents a critical therapeutic priority in schizophrenia management. However, current antipsychotic medications have shown limited efficacy in addressing cognitive impairments (McCutcheon et al., 2023), and some anticholinergic treatments may even exacerbate cognitive dysfunction (Lally & MacCabe, 2015). Given these limitations, neuroplasticity-based computerized cognitive training (CCT) has emerged as a promising adjunctive intervention.

CCT leverages principles of learning-induced neuroplasticity to enhance neuromodulatory processes underlying brain structure, function, and connectivity (Zhang et al., 2024b). Meta-analyses have demonstrated small-to-moderate effects of CCT across multiple cognitive domains, such as attention and working memory (WM) (Lejeune et al., 2021; Prikken et al., 2019), which are attributable to cortical neural plasticity associated with newly acquired perceptual and cognitive skills following CCT interventions (Haut et al., 2010; Mothersill & Donohoe, 2019). Numerous studies have also confirmed the efficacy of CCT in enhancing EF in schizophrenia (Subramaniam et al., 2018). Despite these promising findings, traditional CCT investigations have primarily focused on discrete EF domains, potentially overlooking the multidimensional nature of executive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Indeed, EF comprises multiple dimensions with severity ranging from nearly normal to globally impaired (Raffard & Bayard, 2012). Various EF deficits, including impaired inhibition of automatic responses, reduced cognitive flexibility, and difficulties in maintaining or updating goal-related information, align with Miyake et al.'s (2000) influential three-factor model of EF—inhibition control, cognitive flexibility/switching, and WM (Orellana & Slachevsky, 2013). This heterogeneity suggests that conceptualizing intervention effects as binary outcomes oversimplifies this complex neuropsychological process. Instead, examining shifts along a "psychosis continuum"—the extent to which patients' EF profiles approach those of healthy controls—may provide more nuanced insights (Berberian et al., 2019; Hanlon et al., 2019; Owen & O’Donovan, 2017). Recent advances in multivariate machine learning offer quantitative metrics to capture patients' positions along this continuum (Haas et al., 2021), potentially enhancing our ability to predict and improve real-world functional outcomes.

Previous meta-analyses have revealed heterogeneous effects of cognitive interventions on cognitive performance and daily functioning in schizophrenia (McGurk et al., 2007; Wykes et al., 2011), highlighting the importance of identifying baseline predictors of treatment response. Recent studies have applied machine learning to capture baseline latent variables that predict cognitive intervention outcomes a priori (Shani et al., 2019). For example, Vladisauskas et al. (2022) trained a support vector classifier that predicted improvement in children following cognitive interventions using baseline individual differences. Others have built models to predict adherence to cognitive training protocols (He et al., 2022; Singh et al., 2022) or functioning in early psychosis patients using baseline cognitive data (Walter et al., 2024). Although machine learning methods excel at modeling high-dimensional, nonlinear relationships, they are essentially associative prediction frameworks that cannot establish potential causal relationships. To address this limitation, researchers have proposed integrative models that apply temporal precedence principles inspired by Granger causality alongside the advantages of machine learning (Biazoli Jr. et al., 2024; Hofman et al., 2021). Granger causality posits that (i) the cause precedes the effect and (ii) the cause must contain unique information that helps predict the effect (Shojaie & Fox, 2022). Importantly, and in contrast to interventional accounts of causality, determining Granger causality depends only on prediction, making it straightforward to integrate into data-driven approaches. By leveraging feature ablation and bootstrap significance testing while constraining the temporal precedence of the cause and the informational uniqueness of the predictive effect, XGBoost can be used to screen for robust predictive factors associated with symptom alleviation. Further, a series of regression validation analyses can be constructed to examine the robustness of the candidate factors’ effects after controlling for potential confounders, ensuring the relative independence and robustness of their potential causal interpretations. Based on this framework, we can systematically identify robust baseline predictors for treatment outcomes following cognitive intervention, aiming to screen for factors that exhibit temporal associations and predictive robustness in relation to the alleviation of EF deficits from observational data, thereby providing testable hypotheses for future cognitive intervention research.

The present study aims to advance the evaluation of CCT interventions in schizophrenia by employing multivariate machine learning to quantify shifts in patients’ EF profiles along the psychosis continuum. We applied a previously developed classifier to a new longitudinal intervention sample and evaluated the intervention's efficacy in promoting shifts toward a healthy EF profile (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we implemented an exploratory framework inspired by Granger causality principles to identify baseline predictors with potential causal relevance for these shifts. Through this integrated approach, we aim to advance precision psychiatry and guide the development of targeted cognitive interventions for schizophrenia.

Schematic diagram of the study design and analysis pipelines.

Note: The study comprised three main steps: Step 1: Participant recruitment and development of SVM classifier. Two independent samples were recruited: a cross-sectional discovery sample and a longitudinal intervention sample. All participants underwent comprehensive clinical assessments and completed five paradigms measuring executive function (EF) across three dimensions. Using data from the discovery sample, we developed a support vector machine (SVM) classifier to distinguish individuals with schizophrenia from healthy controls based on seven EF assessments derived from the five paradigms (Zhang et al., 2024a). The longitudinal intervention sample participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: (1) working memory training with adaptive N-back training, (2) active control with non-adaptive 1-back training, or (3) treatment-as-usual. Step 2: Application of the SVM classifier to the longitudinal intervention sample. EF features from all three intervention groups were normalized and adjusted for age, gender, and education level before being input into the SVM classifier developed in Step 1. We applied Platt scaling to calibrate the classifier's decision scores, fitting a logistic regression model to the original healthy control-schizophrenia classifications and applying it to the intervention dataset. Step 3: Identification of baseline predictors influencing executive dysfunction changes. We employed an exploratory causal discovery framework combining Granger causality inference with XGBoost, supplemented by univariate and multivariate regression analyses, to identify baseline factors associated with changes along the executive dysfunction continuum.

This single-blind, randomized controlled three-arm trial investigated adaptive WM training in patients with schizophrenia. The trial compared adaptive N-back training and non-adaptive 1-back training with treatment-as-usual in clinically stable patients. Outcome assessments evaluated EF across three core dimensions using behavioral tasks and machine learning approaches. The study was conducted between May and October 2024 at the Third People's Hospital of Lanzhou City. The trial was retrospectively registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2400089970; https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=283970).

Ethics approval and consentThe authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Ethics Committees at the Third People's Hospital of Lanzhou City and Northwest Normal University (Lanzhou, China; ethics approval no. NWNU202405). All participants provided written informed consent after receiving comprehensive information about the study aims, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

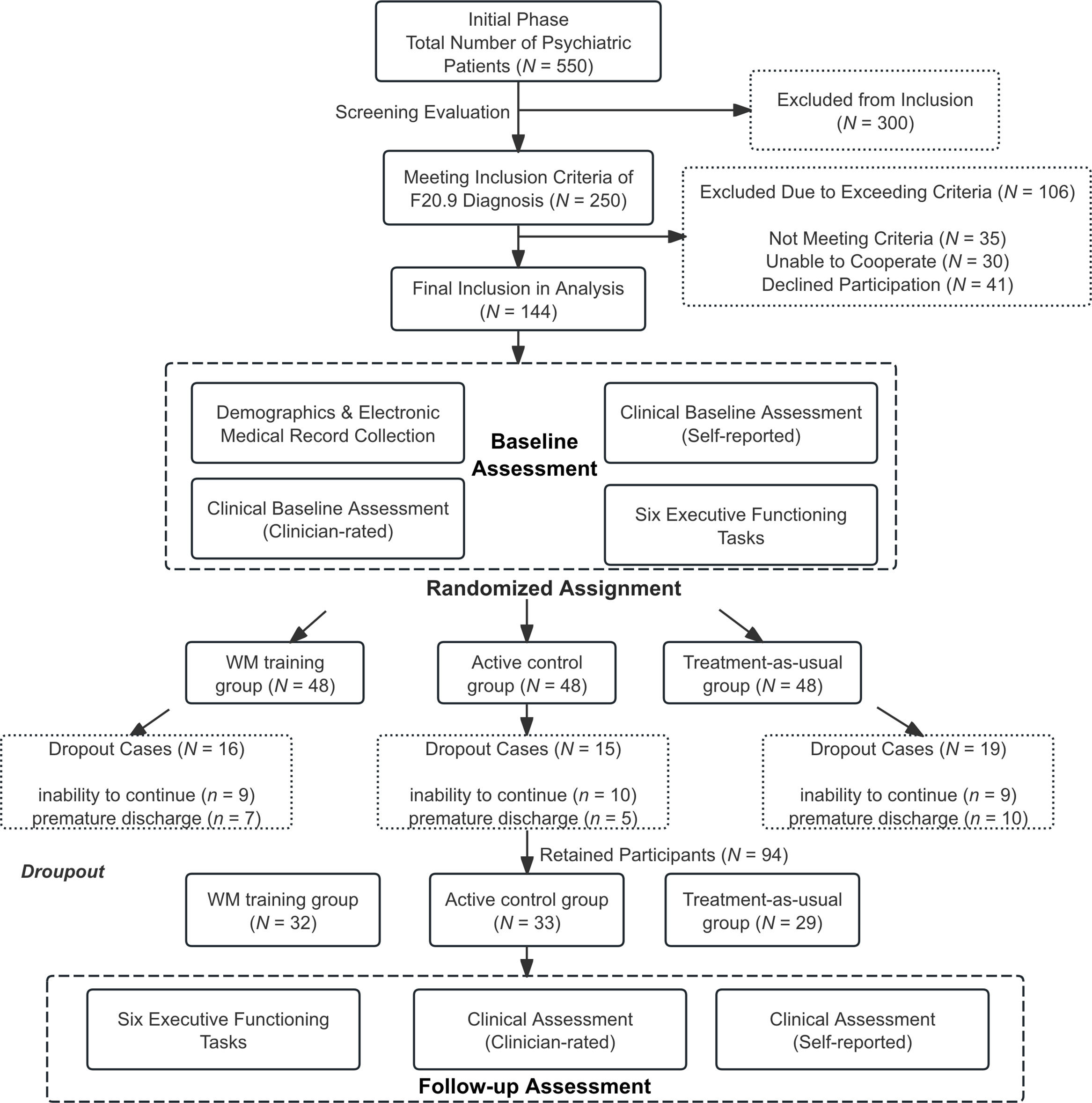

Data collectionParticipant recruitmentTwo samples were recruited from the Third People's Hospital of Lanzhou City. The cross-sectional discovery sample consisted of 195 patients with schizophrenia and 169 age- and sex-matched healthy controls, previously recruited and described in Zhang et al. (2024a). The longitudinal intervention sample comprised 144 patients who had received inpatient treatment within the past two years. Both patient samples were recruited using identical inclusion and exclusion criteria. Schizophrenia diagnoses were established by two resident psychiatrists using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) criteria (F20.9) and confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I). All patients were clinically stable, undergoing consistent treatment, with no anticipated medication changes during the study. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18–65 years; (2) capacity to provide informed consent and complete study procedures; and (3) ability to understand and follow task instructions in computerized cognitive assessments. Exclusion criteria included: (1) severe physical illnesses; (2) visual impairments; or (3) adverse drug reactions (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1). Symptom severity was evaluated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987). Detailed clinical information, such as illness duration and medication regimens, was obtained from electronic medical records.

Flow Diagram of Participant Recruitment and Retention.

Note: During the study period, 550 psychiatric inpatients were screened for eligibility. Initial screening excluded 300 patients (180 with non-schizophrenia diagnoses, 75 with acute medical conditions, 45 with severe cognitive impairment). Secondary screening of 250 patients with confirmed schizophrenia excluded 106 additional individuals (35 not meeting inclusion criteria, 30 unable to engage with study procedures, 41 declining participation). The remaining 144 patients were randomized equally to three study arms (n = 48 each). During the intervention period, 50 participants (34.7 %) discontinued treatment, resulting in 94 study completers (32 in adaptive training, 33 in active control, 29 in treatment-as-usual). Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

This study was based on the influential model, which subdivides EF into three core dimensions (Fig. 3A): inhibitory control, WM (updating and maintenance), and cognitive flexibility (Friedman & Miyake, 2017). We selected five behavioral tasks of varying complexity to measure these EF dimensions (details in Supplementary Methods) (Zhao et al., 2023): (1) Running-memory (RM) updating task was used to examine WM updating (Zhao et al., 2022); (2) Digit span backward task (DSBT) was used to measure WM maintenance (span) (Zhao et al., 2023); (3) Stroop task was used to measure interference inhibition (Stroop, 1935); (4) Go/No-Go task was used to measure response inhibition (Gomez et al., 2007); and (5) Number-switching task was used to measure cognitive flexibility (Kray et al., 2002). All behavioral tasks were performed using E-Prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

EF Behavioral Tasks and Working Memory Training Procedures.

Note: (A) Schematic illustrations of the five behavioral tasks used to measure EF dimensions across varying levels of complexity. (B) Radar plots comparing EF feature profiles at baseline and follow-up across the three intervention groups: 1) working memory training with adaptive N-back training, 2) active control with non-adaptive 1-back training, and 3) treatment-as-usual. All plots employ Min-Max normalization (0–100 scale) for standardized comparison. (C) Schematic illustration of the computerized working memory training paradigms. The adaptive N-back training task (upper panel) requires participants to view a sequence of stimuli and subsequently identify the final three items in correct order. The non-adaptive 1-back control task (lower panel) requires immediate comparison of each stimulus with the immediately preceding item. (D) Training session schedules for the adaptive N-back WM training task and the non-adaptive 1-back WM training task.

Two computerized WM training programs were used: an adaptive N-back task for the training group and a non-adaptive 1-back task for the active control group. Both training groups completed 20 sessions over 4 weeks (5 sessions per week, 30−60 min per session), while the treatment-as-usual group received standard care without additional cognitive training.

Adaptive N-back WM training taskThe adaptive N-back training program included three tasks targeting different domains: animals, spatial locations (Mario), and letters (Zhao et al., 2022). In each task, a series of 5, 7, 9, or 11 stimuli were presented sequentially (Fig. 3C). Participants were required to continuously remember the last three items presented. At the end of each series, the nine stimuli were displayed, three of which corresponded to the final three stimuli from the current series. Participants were required to select these three target stimuli in the correct order and received accuracy feedback after each trial. Each training session consisted of six blocks, with each block containing one series of each length (5, 7, 9, and 11 items). The stimulus presentation time started at 1750 ms and was adaptively adjusted based on performance. If accuracy was above threshold, presentation time decreased by 100 ms for the next block. If accuracy fell below threshold, presentation time increased by 100 ms. The presentation time attained at the end of each session was carried over to the beginning of the next session. Participants in the training group completed all three N-back tasks (animals, Mario, letters) during each session and were allowed to select the task order themselves. The Mario spatial task is illustrated in Fig. 3C, while the animal and letter variants are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Performance on each task was quantified as the average stimulus presentation time used across the six blocks.

Non-Adaptive 1-back control training taskThe active control group completed three non-adaptive 1-back WM tasks (Fig. 3C) identical in design to the adaptive training tasks, except that task difficulty was fixed at the 1-back level (Beloe & Derakshan, 2020). On each trial, participants simply compared the current stimulus with the one presented immediately before it.

Randomization and blindingFollowing baseline assessment, participants were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to adaptive N-back WM training (n = 48), non-adaptive 1-back training (n = 48), or treatment-as-usual (n = 48). The randomization sequence was generated prior to study initiation using permuted block randomization, implemented through the randomizeR package (version 3.0.2) in R statistical software (Uschner et al., 2018). An independent team member who had no involvement in participant enrollment, assessment, or intervention delivery maintained the randomization list securely. Group allocations were disclosed to the intervention team only after completion of baseline assessments.

This study employed a single-blind design. Participants remained unaware of their group allocation throughout the study period, and the psychiatrist conducting clinical symptom assessments was blinded to group assignments. However, the nature of behavioral interventions precluded blinding of research team members conducting EF assessments, as they were involved in intervention delivery. Statistical analyses were conducted with knowledge of group assignments to ensure appropriate model specification.

Behavioral task and clinical scale analysisPrior to analysis, missing values were handled through multiple imputation, and outliers exceeding ±3 standard deviations from the mean were winsorized to these threshold values (Jakobsen et al., 2017). Demographic, clinical, and electronic medical record data were compared between the three participant groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. False discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons. EF task performance was analyzed using linear mixed models (LMMs), with group and time point (pre- vs. post-intervention) as fixed effects, and age, sex, education, and olanzapine-equivalent dose as covariates. LMM results were FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons. Correlations between EF measures, PANSS scores, and electronic medical record data were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients, with FDR correction (Supplementary Figure S2).

Evaluating the continuum of executive dysfunction via machine learning classifiers following working memory trainingA previously developed support vector machine (SVM) classifier, trained to discriminate individuals with schizophrenia (SCZ) from healthy controls (HCs) using seven EF assessments across three dimensions ( Zhang et al., 2024a), was applied to the intervention sample at baseline and follow-up without requiring retraining (Fig. 1). The classifier employed nested cross-validation (inner loop k = 3 for hyperparameter optimization using Optuna (Akiba et al., 2019), outer loop k = 5 for model validation), repeated 100 times to ensure robust performance estimation (Habets et al., 2023) (detailed methods in Supplementary Materials). The classifier generated subject-specific linear SVM decision scores for each patient at both timepoints. SVM-predicted probabilities were calibrated to align with expected class distributions and clinical reality using Platt scaling, fitting logistic regression to the decision scores of the original HC-SCZ model and applying it to the intervention dataset classifications (Haas et al., 2021). To control for potential confounders, the intervention group’s EF scores at both timepoints were normalized using the healthy control group's mean and standard deviation, and adjusted for age, gender, and education level using regression weights estimated from the healthy population. The residualized EF scores (adjusted EF scores after removing covariate effects) were input into the SVM to obtain decision values for each schizophrenia participant at baseline and follow-up. The difference in probability scores between follow-up and baseline, termed “changes in the continuum of executive dysfunction,” quantifies the direction of shift across the SVM hyperplane post-intervention. A higher follow-up probability means a shift toward a healthier profile, while a lower probability implies a shift toward a more psychosis-like profile. Correlation analyses confirmed that the results were not biased by antipsychotic medication or illness duration (Haas et al., 2021).

Identifying baseline predictors of executive dysfunction continuum changes via an exploratory causal discovery frameworkTo identify baseline factors with potential causal relevance that influence treatment outcomes across the executive dysfunction continuum, we implemented an exploratory framework inspired by the temporal precedence principle of Granger causality (which posits that predictors must precede outcomes and contain unique predictive information). Baseline predictors included demographics, clinical data from electronic medical records, and EF features. The primary outcome was movement along the executive dysfunction continuum, operationalized as the difference in SVM probability scores between baseline and follow-up. We employed a 70/30 train-test split following established best practices for moderate sample sizes (Vabalas et al., 2019). An XGBoost model was trained on 70 % of the data, with hyperparameters optimized through 3-fold cross-validation using Optuna (Akiba et al., 2019). Model performance was validated on the remaining 30 % test set using individual-level mean squared error, mean absolute error, and R-squared metrics. A systematic ablation study was then conducted, sequentially excluding each predictor to quantify its impact on model performance. Predictors whose exclusion significantly decreased performance (p < 0.05; 3000 FDR-corrected bootstrap iterations) were identified as robust predictive factors (Fig. 4).

Subsequently, univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to examine the robustness of these factors while controlling for confounders and establishing their independent predictive contributions. Two sets of multiple regression models were built: one with the full set of predictors, and another including only the candidate factors identified through the XGBoost ablation study with bootstrap resampling. Additionally, univariate regressions were implemented for each factor independently to obtain uncorrected estimates. If the factors are causally related to the outcomes and independent of each other, the uncorrected and corrected regression coefficients from single and multiple regressions would be similar. Convergent results across these regression models would reinforce that the predictive factors are independent of each other (Biazoli Jr. et al., 2024).

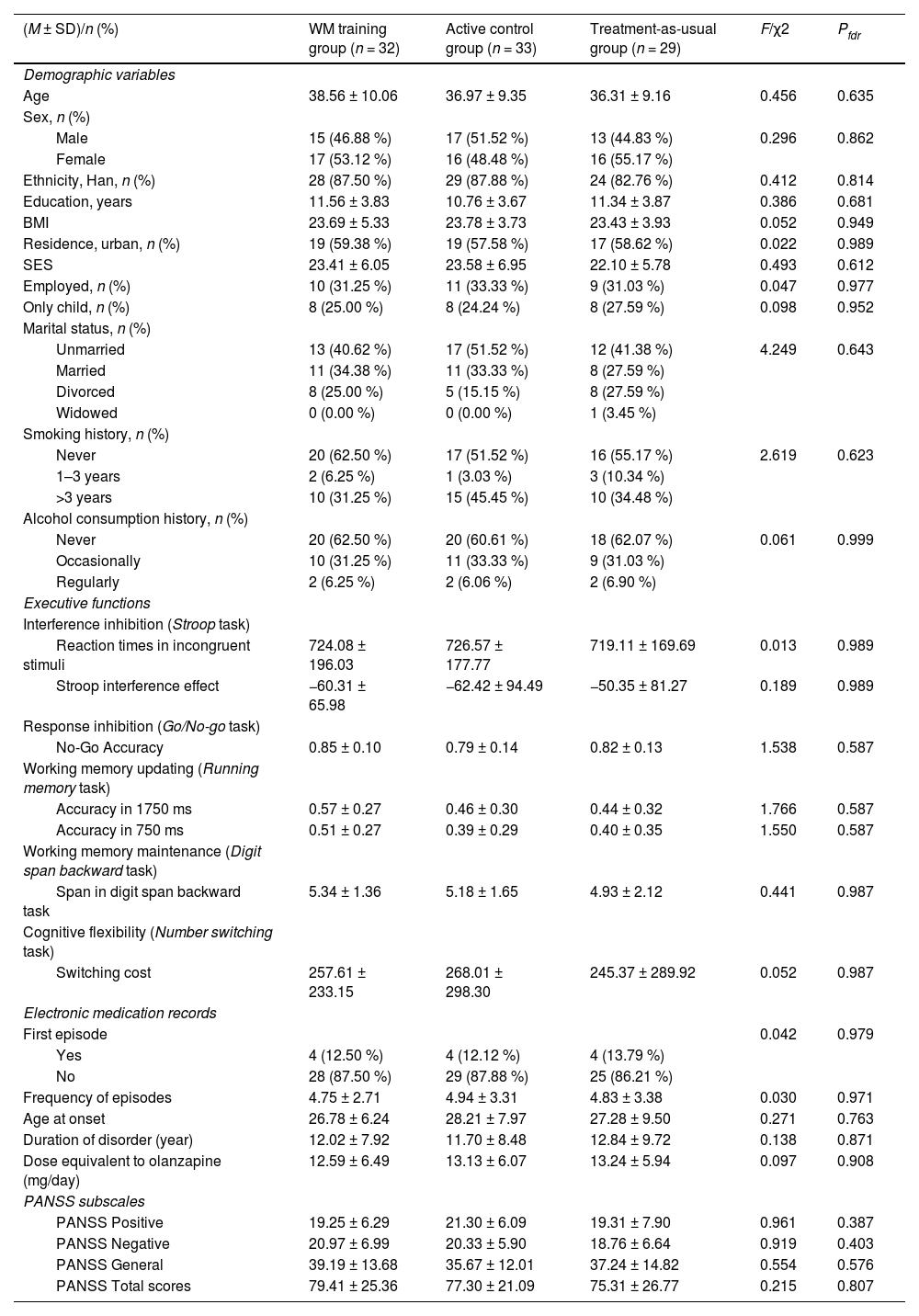

ResultsSample characteristics and treatment participationThe cross-sectional discovery sample (N = 364) comprised 195 individuals with schizophrenia (age 35.35 ± 9.35 years, 58.5 % male) and 169 healthy controls (age 37.69 ± 13.71 years, 52.1 % male), which was used to establish baseline EF profiles across the psychosis continuum (Supplementary Table S2, Figure S3). In the longitudinal intervention sample, 94 of 144 participants (65.3 %) completed the trial. The adaptive training group had 16 participants lost to follow-up due to inability to continue the intervention (n = 9) or premature discharge from the healthcare facility (n = 7), resulting in a final sample of 32 participants (age 38.56 ± 10.06 years, 46.88 % male). The active control group experienced similar attrition, with 15 participants discontinuing due to inability to complete the intervention (n = 10) or premature discharge (n = 5), yielding a final sample of 33 participants (age 36.97 ± 9.35 years, 51.52 % male). In the treatment-as-usual group, 19 participants did not complete the study protocol due to inability to continue (n = 9) or premature discharge (n = 10), with 29 participants remaining at study completion (age 36.31 ± 9.16 years, 44.83 % male). Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in each intervention group. As expected for a properly randomized trial, no significant between-group differences were observed at baseline in EF metrics, demographic variables, or clinical characteristics (all pfdr > 0.05; Fig. 3B, Table 1, Supplementary Figure S4).

Participant demographics and clinical characteristics (N = 94).

Note: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). Bold p-values indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). Calculation: BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). SES was assessed by summing scores across four dimensions: material wealth, parental education, parental occupation, and monthly household income; higher scores indicate greater family socioeconomic status (see Supplementary Materials for details). First episode indicates whether patients were currently in their first psychotic episode. Frequency of episodes refers to the total number of distinct psychotic episodes requiring hospitalization. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SES, socioeconomic status; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; fdr, false discovery rate correction.

Fig. 3D illustrates the mean stimulus presentation time across the 20 training sessions for the adaptive N-back WM training task. A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects of training session (p < 0.001) for all tasks, indicating consistent reductions in presentation time. Polynomial trend analyses yielded excellent model fits, with significant linear trends for the animal (β = –78.44, p = 0.011), letter, and Mario tasks. Mean presentation times decreased substantially from Session 1 to Session 20 in all tasks (e.g., from 1804.69 ms to 671.88 ms in the animal task). These results suggest that the adaptive N-back WM training successfully enhanced WM updating efficiency. Similar improvements were observed in the non-adaptive 1-back WM training task, with significant session effects and robust model fits for all tasks (animal: R² = 0.974; letter: R² = 0.957; Mario: R² = 0.982). Reaction difficulty indices decreased from Session 1 to Session 20 in the animal (from 1.61 to 0.92), letter (1.62 to 0.74), and Mario tasks (1.60 to 0.64).

Near-transfer effects on working memory and general psychopathology, but no far-transfer effectsThe results demonstrated that computerized training produced near-transfer effects, as evidenced by significant improvements in WM updating performance following adaptive N-back WM training. Specifically, in the 1750 ms condition of the WM number-running task, LMM analysis revealed a significant main effect of time (F = 13.573, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). Post hoc comparisons indicated that while baseline performance was comparable across groups, the WM training group outperformed both the active control group (p < 0.001) and treatment-as-usual group (p < 0.001) at follow-up, with no significant difference between the latter two (p = 0.530). Similar findings emerged for the 750 ms condition (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table S3).

Evaluating the Continuum of Executive Dysfunction via Machine Learning Classifiers Following Cognitive Intervention.

Note: (A) Linear mixed model results examining whether working memory training significantly improved EF relative to an active control group receiving non-adaptive 1-back training and a treatment-as-usual group, with age, sex, education, and olanzapine-equivalent dose as covariates. (B) Test set classification performance of the SVM classifier for discriminating schizophrenia from healthy controls. (C) The continuum of executive dysfunction scores for the three intervention groups, obtained by inputting baseline and follow-up EF features into the SVM classifier. (D) Correlations between change scores in the continuum of executive dysfunction and baseline EF features, as well as change scores in the PANSS (N = 94).

Abbreviations: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; AUC, area under the curve; acc, accuracy; rt, reaction time.

In contrast, computerized adaptive N-back WM training did not yield far-transfer effects (Supplementary Figure S5, Table S3), as training did not lead to improvements in inhibition control, WM maintenance, or cognitive flexibility (other dimensions of EF). Although these functions showed significant improvements from baseline to follow-up, no significant between-group differences were observed (all p > 0.05).

Analysis of clinical outcomes revealed that both the PANSS general psychopathology and total scores demonstrated significant group-by-time interactions (Supplementary Table S3). For general psychopathology, LMM analysis showed a significant group-by-time interaction (F = 4.413, p = 0.013) and a significant main effect of time (F = 6.732, p < 0.001), with significant reductions in scores from baseline to follow-up observed in all three groups (WM training group: p < 0.001; active control group: p < 0.001; treatment-as-usual group: p = 0.006). Although the overall group effect did not reach significance (p = 0.549), post hoc comparisons showed that the WM training group achieved significantly lower general psychopathology scores at follow-up compared with both the active control group (p = 0.024) and treatment-as-usual group (p = 0.022), with no significant difference between the latter two (p = 0.442). Similarly, PANSS total scores showed a significant group-by-time interaction (F = 3.421, p = 0.035) and a significant main effect of time (F = 67.452, p < 0.001), with all groups demonstrating significant improvements from baseline to follow-up (p < 0.001 for all groups). However, post hoc comparisons for total scores revealed no significant between-group differences at follow-up (all p > 0.24) (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table S3).

Sensitivity analyses without covariate adjustment (i.e., without adjusting for age, gender, and education level) yielded consistent findings (Supplementary Table S4). The pattern of near-transfer effects on WM updating performance remained unchanged, with significant group-by-time interactions for both the 1750 ms condition (F = 5.497, p = 0.005) and 750 ms condition (F = 7.168, p = 0.001). Similarly, clinical outcomes showed comparable results, with significant group-by-time interactions for PANSS general psychopathology (F = 4.388, p = 0.014) and total scores (F = 3.330, p = 0.038), supporting the robustness of the main findings.

Working memory training increases probability of healthy-like EFAn SVM classifier distinguished patients with schizophrenia from healthy controls, achieving a cross-validated AUC (Area Under the Curve) of 0.86, balanced accuracy of 0.82, sensitivity of 0.76, and specificity of 0.88 (Fig. 5B). Residuals from the EF assessments were then input to the SVM classifier, trained on healthy control and schizophrenia data, to generate a predicted probability for each subject, representing their “healthy-like” EF profile. A generalized linear model (GLM) analysis of these probabilities revealed a significant group-by-time interaction (p < 0.001) across the WM training, active control training, and treatment-as-usual groups at baseline and follow-up (Fig. 5C). Post hoc Tukey’s HSD tests indicated no significant inter-group differences at baseline (p > 0.05). However, the WM training group exhibited a substantial increase in the healthy-like probability from 13.21 % at baseline to 38.79 % at follow-up (p < 0.001), while the active control training and treatment-as-usual groups showed no significant changes (p > 0.05).

Associations between healthy-like EF probability and clinical measuresPearson correlation analyses examined the relationship between changes in the predicted healthy-like probability and various baseline cognitive and clinical measures in the overall sample (N = 94). Baseline accuracy on the 1750 ms (r = 0.305, pfdr = 0.003) and 750 ms (r = 0.249, pfdr = 0.016) conditions of the WM number-running task was significantly positively correlated with the change in predicted probability (Fig. 5D). Conversely, baseline reaction time for incongruent stimuli on the Stroop task was significantly negatively correlated with the change in predicted probability (r = –0.245, pfdr = 0.017), indicating that faster responses were associated with a greater increase in healthy-like probability. Baseline accuracy on the Go/No-Go task was also positively correlated with the predicted probability change (r = 0.260, pfdr = 0.011).

Regarding clinical symptomatology, significant inverse correlations were observed between the change in predicted probability and changes in PANSS Negative (r = –0.320, pfdr = 0.002), PANSS General Psychopathology (r = –0.335, pfdr = 0.001), and PANSS Total scores (r = –0.320, pfdr = 0.002) (Fig. 5D). Notably, the predicted probability showed no significant correlation with olanzapine dosage or illness duration (all pfdr > 0.05), suggesting that these factors were not systematically associated with medication intake or illness chronicity (Supplementary Figure S6).

Predictors of changes in the executive dysfunction continuum identified through an exploratory causal discovery frameworkTo predict changes in the continuum of executive dysfunction, we developed an XGBoost regression model incorporating 24 baseline predictors. The model showed strong performance on the test set (R² = 0.45, mean squared error [MSE] = 0.04), with over 90 % of individual prediction errors below 20 % of the maximum possible score (Fig. 6A, 6C). Then, we conducted a systematic ablation study to investigate potential causal predictors, sequentially excluding each baseline predictor from the model over 3000 bootstrap resampling iterations. Predictors whose exclusion significantly impaired model performance (pfdr < 0.05) were identified as robust predictive factors (e.g., smoking status, RM 750 accuracy) (Fig. 6D, Supplementary Table S5).

Identifying Baseline Predictors of Executive Dysfunction Continuum Changes via Exploratory Machine Learning Framework.

Note: (A) Performance (top) and feature importance (bottom) of the XGBoost model for predicting changes in the continuum of executive dysfunction using all baseline predictors, including demographics, electronic medical records data, and EF features, evaluated on the test set. (B) SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values for the full model incorporating all baseline predictors. Colors towards yellow indicate higher feature importance, while colors towards red indicate lower importance. The circular plot displays the proportional contribution of each feature category to overall model performance. (C) Individual prediction errors for the baseline model (top) and individual prediction errors for the ablation study (bottom). (D) Predictors whose exclusion significantly decreased performance (p < 0.05; 3000 false discovery rate-corrected bootstrap iterations) were identified as robust predictive factors. (E) To validate the independence of candidate predictors identified through the exploratory causal discovery framework, univariate and multivariable regression analyses were conducted. (Left) Univariate regression analyses with variables selected through XGBoost ablation. (Middle) Multiple regression analyses with variables selected through XGBoost ablation. (Right) Multiple regression analysis with all baseline predictors included in the XGBoost model. Variables highlighted in black boxes demonstrated statistical significance across all three regression approaches, indicating robust and independent predictive value.

Abbreviations: MAE, mean absolute error; MSE, mean squared error; BMI, body mass index; SES, socioeconomic status; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; acc, accuracy; rt, reaction time.

We next validated the independence of candidate predictors identified via the exploratory causal discovery framework. Specifically, we performed univariate and multivariable regression analyses. Univariate analyses revealed DSBT span and No-go accuracy at baseline as strong predictors of changes in healthy-like probability (both β = 0.121, p < 0.001), with Stroop interference effect also showing a significant relationship (β = 0.069, p = 0.006) (Fig. 6E, Supplementary Table S6). RM 750 accuracy had a smaller effect in updated results (β = 0.062, p = 0.016). In a multivariable model using only variables identified through XGBoost ablation, DSBT span remained the strongest significant predictor (β = 0.099, p < 0.001), followed by No-go accuracy (β = 0.086, p = 0.001) (Fig. 6E, Supplementary Table S7). A comprehensive model with all baseline variables (Fig. 6E, Supplementary Table S8) confirmed DSBT span (β = 0.079, p = 0.003), No-go accuracy (β = 0.088, p = 0.001), years of education (β = 0.085, p = 0.003), and frequency of episodes (β = 0.053, p = 0.024) as significant predictors of changes in the continuum of executive dysfunction. In summary, our findings indicate that DSBT span (WM maintenance) and No-go accuracy (response inhibition) represent the most robust baseline predictors of predicting changes in the continuum of executive dysfunction following cognitive intervention.

Additionally, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis (Lundberg & Lee, 2017) of the full baseline model incorporating all predictors (Fig. 6B) corroborated our exploratory causal discovery framework findings. Stroop incongruent reaction time, No-go accuracy, Stroop interference effect reaction time, and DSBT span showed the largest contributions to model predictions, consistent with their roles as key baseline EF measures influencing treatment response.

Supplementary analyses for attritionParticipant attrition represents a well-documented challenge in cognitive training research among individuals with schizophrenia (Szymczynska et al., 2017; Twamley et al., 2011). To evaluate whether differential attrition might have influenced our findings, we conducted comprehensive analyses examining both predictors of dropout and the robustness of our results under various missing data scenarios.

Dropout rates did not differ significantly across the three intervention arms: 33.3 % (16/48) in the adaptive WM training group, 31.3 % (15/48) in the active control group, and 39.6 % (19/48) in the treatment-as-usual group (χ² = 0.81, p = 0.67). Participants discontinued primarily due to inability to continue the intervention (n = 28) or premature discharge from healthcare facilities (n = 22) (Supplementary Table S9). Importantly, binary logistic regression analysis revealed that baseline cognitive performance did not predict participant withdrawal (χ² = 4.28, p = 0.584), with none of the EF measures showing significant associations with dropout (all p > 0.05; Supplementary Figure S7), indicating that attrition was not systematically related to participants' baseline cognitive abilities.

To address potential bias from incomplete data, we conducted intention-to-treat analyses under three different scenarios (Jakobsen et al., 2017). First, intention-to-treat analysis using Random Forest multiple imputation (details in Supplementary Methods) confirmed our primary findings: adaptive WM training produced robust near-transfer effects on the running memory task (maintained for the 750 ms condition and enhanced for both 750 ms and 1750 ms conditions; Supplementary Table S10, Table S11), while no significant far-transfer effects emerged for other EF domains. The WM training group demonstrated greater reduction in PANSS general psychopathology scores compared to both control groups, although the interaction effect for PANSS total scores was attenuated to non-significance (Supplementary Table S11). The healthy-like EF probability for the WM training group increased substantially from 14.6 % at baseline to 40.2 % at follow-up (p < 0.001), with a highly significant group × time interaction (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S10, Figure S8). The associations between healthy-like EF probability and cognitive-clinical measures remained robust, with significant correlations observed for WM performance at 1750 ms (r = 0.291, p < 0.001), No-go accuracy (r = 0.214, p < 0.01), PANSS general change (r = −0.231, p < 0.001), and PANSS total change (r = −0.222, p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S10, Figure S9).

Additionally, sensitivity analyses under best-case and worst-case scenarios tested the boundaries of our conclusions. Under best-case assumptions (mean improvement rate of completers + 1 SD; details in Supplementary Methods), all effects were enhanced, with the WM training group's healthy-like EF probability increasing from 14.6 % at baseline to 44.0 % at follow-up (p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S10, Figure S8). Under worst-case assumptions (mean improvement rate of completers - 1 SD; details in Supplementary Methods), core findings remained intact despite attenuated effects: near-transfer effects persisted for both tasks (Supplementary Table S10, Table S12-S13), the group × time interaction for general psychopathology remained significant (Supplementary Table S12-S13), and the healthy-like EF probability for the WM training group increased from 14.6 % at baseline to 21.3 % at follow-up with marginal significance (p = 0.057; Supplementary Table S10, Figure S8).

Across all intention-to-treat analyses, key patterns remained consistent: WM performance at 1750 ms consistently emerged as the strongest baseline correlate of improvement (r = 0.269 to 0.305), clinical improvements maintained robust negative correlations with healthy-like EF probability (PANSS general: r = −0.231 to −0.335; PANSS total: r = −0.204 to −0.335), and DSBT span was consistently identified as a predictor through the exploratory framework based on temporal precedence principles, with No-go accuracy emerging as a co-predictor in most analyses (Supplementary Table S10, Figures S10-S11).

DiscussionThe present study introduces a novel machine learning framework to evaluate and predict the efficacy of WM training in schizophrenia. In contrast to conventional approaches that rely on binary classifications of interventions as simply “effective” or “ineffective,” our method quantifies cognitive improvements as continuous shifts along a psychosis-health continuum while identifying robust baseline predictors associated with these changes. After completing 20 sessions of adaptive N-back WM training, patients with schizophrenia demonstrated significant near-transfer effects to untrained WM updating tasks compared to both active control and treatment-as-usual groups. These cognitive gains were associated with clinically meaningful reductions in general psychopathology symptoms, despite the absence of far-transfer effects to other EF domains (e.g., inhibitory control). Notably, our machine learning classifier revealed a significant shift in EF profiles along the psychosis continuum, with the WM training group exhibiting a substantial increase in the probability of being classified as having a neurotypical profile, rising from 13.21 % at baseline to 38.79 % at follow-up (p < 0.001). This shift exhibited a significant positive correlation with reductions in PANSS scores. By implementing an integrative model that combines Granger causality principles with machine learning, we identified WM maintenance and response inhibition as the most robust predictors of EF shifts, providing valuable insights for developing personalized cognitive interventions.

Efficacy of working memory training and transfer effectsOur engaging WM training protocol with visually appealing stimuli produced significant near-transfer effects on untrained WM tasks with similar cognitive demands across 20 sessions. Despite comparable baseline performance across all groups, the WM training group exhibited superior performance on the number-running memory task at follow-up. These findings align with previous research indicating that patients with schizophrenia exhibit neural activation changes similar to HCs and significant cognitive improvements following WM training (Li et al., 2015) and targeted interventions (Hubacher et al., 2013; Prikken et al., 2019; Subramaniam et al., 2018).

The absence of far-transfer effects to other EF domains (e.g., inhibitory control) is consistent with the process-specific nature of cognitive training effects documented in the literature. Prior research has consistently demonstrated that training specific cognitive processes yield transfer effects primarily on related cognitive constructs rather than enhancing global cognitive functioning (Hubacher et al., 2013; Melby-Lervåg et al., 2016; Minear et al., 2016; Ramsay et al., 2018; von Bastian & Oberauer, 2013; Zhao et al., 2020). Neuroimaging evidence further suggests that WM training predominantly modulates task-specific neural activity (Cai et al., 2022), with different training protocols targeting distinct perceptual/cognitive domains and producing distinct neural effects.

Interestingly, we observed a transfer of WM training benefits to general psychopathology symptoms. Patients who received adaptive WM training exhibited more substantial improvements in general psychopathology compared to both the active control group and patients receiving standard antipsychotic treatment alone. Specifically, schizophrenia patients exhibited significant reductions in scores on the general psychopathology subscale of the PANSS following WM training, echoing previous findings (Moritz et al., 2014; Pontes et al., 2013). While standard antipsychotic treatment effectively reduces overall symptom severity in schizophrenia, our results indicate that augmenting standard treatment with WM training produces enhanced therapeutic outcomes. Previous research has shown that these augmented improvements remain detectable at 6-month follow-up assessments (Fekete et al., 2022). WM training appears to improve inattention symptoms and enhance WM efficiency, potentially reducing cognitive load during daily activities and thereby freeing cognitive resources for improved emotional regulation and social functioning (Li et al., 2019). These improvements are particularly significant given the intrinsic link between inattention symptoms and general psychopathological manifestations, including thought disturbances, emotional dysregulation, and social withdrawal in schizophrenia.

A novel framework for evaluating cognitive training efficacyA key innovation of our study was the application of machine learning classification to quantify shifts in EF profiles along the psychosis continuum following cognitive control training. Rather than utilizing binary outcome assessments (e.g., "effective" versus "ineffective"), we conceptualized EF changes as shifts along a continuum from psychosis-like toward neurotypical profiles. This approach provides a more nuanced understanding of cognitive improvement following intervention. Our SVM classifier, which achieved an area under the curve of 0.86 in distinguishing patients with schizophrenia from HCs (Zhang et al., 2024a), revealed that the WM training group exhibited a substantial increase in the probability of being classified as having a neurotypical EF profile—from 13.21 % at baseline to 38.79 % at follow-up (p < 0.001). Neither the active control group nor the treatment-as-usual group showed significant changes in classification probabilities. These findings suggest that adaptive WM training not only improves specific EF processes but also promotes a broader reorganization of executive functioning that more closely resembles that of individuals without psychosis. Moreover, the significant correlations observed between changes in the predicted neurotypical probability and reductions in PANSS scores further highlight the clinical relevance of these EF shifts.

While most cognitive remediation studies in schizophrenia have employed univariate analytical techniques (Prikken et al., 2019), such approaches may lack sensitivity to detect subtle, distributed improvements that machine learning algorithms can identify in high-dimensional data. Our classifier probably captured not only changes in absolute performance levels but also modifications in the pattern of relationships among EF dimensions. Schizophrenia is characterized by disrupted connectivity among cognitive processes (Sheffield & Barch, 2016), and WM training may have partially normalized these inter-dimensional relationships, resulting in a more integrated EF architecture without necessarily improving each component to the same degree. Enhanced WM updating ability may have served as a core cognitive process in enhancing functional coordination between different EF components, even when these components showed no measurable improvements when assessed in isolation. This interpretation aligns with mounting evidence that WM updating may be a fundamental process underlying other cognitive deficits in schizophrenia (Anticevic et al., 2013; Galletly et al., 2007). Furthermore, improvements in this updating function can transfer to daily life situations and various EF tasks (Levaux et al., 2009; Reeder et al., 2004). Our findings extend this work by demonstrating that such improvements are associated with a global shift in the EF profile toward a more neurotypical pattern, suggesting a reorganization of cognitive architecture with significant functional implications.

By leveraging Platt scaling to transform SVM decision scores into clinically interpretable probability values, we enable clinicians to intuitively understand patients’ cognitive states and their changes over time. This transformation enhances the interpretability of assessment results and provides a standardized evaluation framework for cognitive training interventions. This framework quantifies individualized intervention effects and offers a reliable tool for future large-scale, multi-center studies and clinical translation.

Baseline predictors of treatment response identified by an exploratory causal discovery frameworkPrevious studies have demonstrated that baseline cognitive abilities serve as strong predictors of individual response to cognitive interventions (Foster et al., 2017). For patients with schizophrenia, accurate identification of predictive relationships among baseline factors is crucial for optimizing treatment outcomes. While previous studies have employed machine learning algorithms (e.g., LASSO) to predict intervention responses (He et al., 2022; Ramsay et al., 2018; Vladisauskas et al., 2022), these approaches have been limited by their reliance on correlational rather than potentially causal relationships.

We addressed this limitation by implementing an exploratory framework that combines Granger causality principles with machine learning to identify baseline factors that may have causal relevance for treatment outcomes across the psychosis continuum (Hofman et al., 2021). Our analyses revealed several baseline characteristics that significantly predict response to treatment, including sociodemographic factors (e.g., residence, smoking status) and EF features (e.g., No-go accuracy). To determine whether these factors function independently, we conducted regression analyses with candidate factors alone as well as all baseline factors as predictors. Performance on the backward digit span test (WM maintenance) and accuracy on the No-go trials (response inhibition) emerged as robust and relatively independent cognitive predictors, maintaining significance consistently across all regression models.

These findings align with previous research demonstrating that cognitive intervention gains can be predicted by pre-existing cognitive traits (Vladisauskas et al., 2022; Walter et al., 2024), supporting the 'Matthew effect' in cognitive training—whereby individuals with stronger baseline abilities tend to show greater training gains. Previous studies found that Go/NoGo task performance predicts completion of substance abuse treatment (Steele et al., 2014), and individuals with high WM capacity show larger gains from EF training (Foster et al., 2017). WM likely facilitates retention of training strategies, while inhibitory control enables patients to maintain focus during intervention sessions. These results have important clinical implications for personalizing cognitive interventions in schizophrenia. Treatment approaches could be tailored based on individual cognitive profiles, with patients displaying lower baseline WM or inhibitory control potentially benefiting from additional support or modified protocols. Alternatively, preliminary interventions specifically targeting these foundational cognitive abilities may improve subsequent response to comprehensive cognitive remediation.

Our exploratory framework offers distinct advantages over conventional approaches. While previous studies have applied machine learning models to baseline features and examined feature importance metrics such as SHAP values (Kim et al., 2025; Koutsouleris et al., 2016; Van Hooijdonk et al., 2023), these approaches often lack statistical significance testing for individual predictors. Similarly, traditional regression analyses for treatment response (Chen et al., 2018; Enache et al., 2021) provide significance tests but cannot adequately account for predictor independence or capture nonlinear relationships. Our framework identifies factors with strong temporal associations and predictive independence while accounting for nonlinear relationships through multivariate machine learning and rigorous statistical validation. However, while this approach provides a systematic method to identify predictors that warrant experimental validation, our two-timepoint observational design cannot establish definitive causality. The baseline predictors identified through our analyses represent variables that meet statistical criteria for potential causality but require experimental manipulation to confirm true causal effects. Future randomized controlled trials that experimentally manipulate these identified predictors (e.g., pre-training interventions targeting WM maintenance or response inhibition) would provide definitive causal evidence and could inform the development of optimized, personalized cognitive training protocols. Such studies would validate whether enhancing these baseline cognitive abilities genuinely improves subsequent response to comprehensive cognitive remediation, thereby advancing precision medicine approaches in schizophrenia treatment.

Limitations and considerationsDespite these promising results, several limitations warrant consideration. First, similar to previous cognitive training studies in psychiatry (Lejeune et al., 2021; Prikken et al., 2019), our sample size was relatively modest, and we did not conduct extended follow-up assessments to evaluate the long-term maintenance of intervention effects. The attrition rate (approximately 35 %) could potentially introduce selection bias, although our analyses indicated that participants who withdrew did not significantly differ from study completers on key sociodemographic characteristics or clinical parameters, and our ITT analyses demonstrated that primary findings remained robust across different missing data strategies (see Supplementary materials). Future research should address these limitations through larger, more adequately powered trials and implementation of longitudinal follow-up protocols to determine whether the observed improvements in EF profiles persist over time. Second, several methodological constraints warrant consideration. This trial was not prospectively registered before participant enrollment, though retrospective registration has been completed. Additionally, while we maintained participant blinding and ensured that clinical symptom assessors were blinded to group allocation, complete double-blinding was not achieved—EF assessors and data analysts were aware of group assignments. This limitation is common in cognitive training research due to the interactive nature of behavioral interventions, with previous major trials (Mahncke et al., 2019; Nuechterlein et al., 2023) facing similar constraints. These design features may introduce potential biases in behavioral assessments and analytical decisions. Future studies should implement prospective registration, employ independent blinded assessors for all outcomes, and conduct blinded data analysis using coded group labels where feasible. Third, our study's generalizability is limited by its single-center design and exclusive focus on hospitalized patients. Additionally, participants received various antipsychotic medications, which we standardized using olanzapine equivalents (Gardner et al., 2010; Leucht et al., 2015). While no significant baseline differences were observed between groups, the potential differential effects of specific pharmacological agents cannot be entirely ruled out. Future multi-center studies incorporating both inpatient and outpatient populations, with more controlled medication protocols, would strengthen external validity.

ConclusionThis study provides preliminary evidence that adaptive WM training produces improvements in domain-specific executive functioning and general psychopathology symptoms in schizophrenia. Our multivariate machine learning approach revealed that WM training is associated with shifts in EF profiles along the psychosis-health continuum. The identification of baseline WM maintenance and response inhibition as robust predictors rather than causal determinants offers insights for developing personalized intervention strategies. However, these findings require cautious interpretation given the single-center design, modest sample size, 35 % attrition rate, and lack of complete assessor blinding. Replication in larger, multi-site longitudinal studies is essential to validate these preliminary results and establish the generalizability of both the intervention and the machine learning framework.

Authors’ contributionsTongyi Zhang designed the study, conducted the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Meifang Su acquired the data and drafted the manuscript. Xiaoning Huo made significant contributions to data acquisition. Xin Zhao designed the study, critically revised the manuscript, and provided funding. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding statementThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32260207 [to Xin Zhao]).

Ethical standardsThe authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Ethics Committees at the Third People's Hospital of Lanzhou City and Northwest Normal University (Lanzhou, China; ethics approval no. NWNU202405). All participants provided written informed consent after receiving comprehensive information about the study aims, procedures, potential risks, and benefits.

Data availability statementThe raw data of our sample are protected and are not publicly available due to data privacy. These data can be accessed upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (Xin Zhao). Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Xin Zhao) upon request.

Code availability statementScripts to run the main analyses have been made publicly available and can be accessed at github.com/tyzhang98/ML-PsyExecShift.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.