The epIdeMiology landscape PAtient Care paThways of Obesity (IMPACT-O) study was a multi-country, retrospective cohort study that utilised healthcare databases to determine the landscape/impact of overweight and obesity. Here we describe the sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of adults with a first record of overweight/obesity or obesity in Spain between 2018 and 2022.

Materials and methodsThe IQVIA longitudinal patient database in Spain was used to identify individuals with a first record of overweight/obesity, as determined by diagnosis codes and/or body mass index (BMI) measurements (overweight/obesity cohort: BMI ≥25kg/m2; obesity cohort: BMI ≥30kg/m2), in the years 2018–2022. Demographic and clinical parameters, including obesity-related complications (ORCs), as recorded by primary care providers and specialists contributing to the database, were described.

ResultsThe overweight/obesity cohort included 25,016 individuals, and the obesity cohort 13,441 individuals. Most individuals with overweight/obesity (60.1%) and obesity (63.6%) presented with ≥1 ORCs. The most frequent ORCs among people with obesity were hypertension (25.3%), dyslipidaemia (19.8%), anxiety (19.0%), osteoarthritis (14.3%), low-back pain (10.9%) and depression (10.9%). The proportion of individuals receiving pharmacological therapies with an effect on weight was <1%. There were no records of lifestyle interventions or bariatric surgery in the database for this population.

ConclusionsThis study highlights the high ORC burden at first documented diagnosis of overweight/obesity. Very few individuals with obesity in Spain receive pharmacological treatment with an effect on weight. Patient management could be improved by systematically recording all interventions in this population.

El estudio IMPACT-O (epIdeMiology landscape Patient Care paThways of Obesity) es un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo y multinacional que utilizó bases de datos de historias clínicas para determinar la situación e impacto del sobrepeso y la obesidad. Aquí se describen las características y el tratamiento de adultos con un primer registro de sobrepeso/obesidad en España entre 2018 y 2022.

Materiales y métodosSe utilizó la base de datos longitudinal de pacientes de IQVIA en España para identificar a personas con un primer registro de sobrepeso/obesidad, determinado por códigos de diagnóstico y/o mediciones del índice de masa corporal (IMC) (sobrepeso/obesidad: IMC ≥25kg/m2; obesidad: IMC ≥30kg/m2). Se describieron los parámetros demográficos y clínicos, y las complicaciones asociadas a la obesidad.

ResultadosLa cohorte de sobrepeso/obesidad incluyó 25.016 personas y la cohorte de obesidad 13.441 personas. La mayoría de las personas con sobrepeso/obesidad (60,1%) y obesidad (63,6%) presentaron ≥1 complicación asociada a la obesidad, siendo hipertensión (25,3%), dislipidemia (19,8%), ansiedad (19,0%), osteoartritis (14,3%), dolor lumbar (10,9%) y depresión (10,9%) las más frecuentes. Menos del 1% recibieron terapias farmacológicas con efecto sobre el peso. No hubo registros de intervenciones en el estilo de vida o cirugía bariátrica en la base de datos para esta población.

ConclusionesEste estudio destaca la alta carga de complicaciones asociadas a la obesidad en el primer diagnóstico de sobrepeso/obesidad. En España, pocas personas con obesidad reciben tratamiento farmacológico con efecto sobre el peso. El manejo de los pacientes podría mejorar con un registro sistemático de intervenciones.

Obesity is a chronic, multifactorial, and relapsing disease affecting a large proportion of adults globally.1 A survey of the prevalence of overweight and obesity conducted in 12 European countries in 2017–2018 found that, in Spain, overweight was self-reported by 38.7% of participants, and obesity by 15.1%.2 The ENPE study in Spain estimated that the prevalence of overweight in the population aged 19–64 years was 36.1% and that of obesity was 22.0% in 2014–2015.3 However, a recent study found strong geographical and sex differences.4 Further, a trend analysis of the prevalence of obesity using data from the complete historical series of the Spanish National Health Survey and the European Health Survey in Spain showed that obesity increased from 7.3% in 1987 to 15.7% in 2020.5 The prevalence of overweight and obesity in the younger population (<24 years old) is also high in Spain6 and has substantially increased in the last decade.7 Given the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents, the World Obesity Federation projects a sustained annual increase in adult obesity in Spain of 0.9% for the period 2020–2035.8

Misunderstanding of the complex causes of obesity can result in an oversimplification of the disease as a lifestyle condition solely dependent on personal choices and reinforce stigma. These perceptions could be present in some healthcare professionals, leading to a reduction in patient engagement and delayed or inadequate treatment options.9,10 In an effort to change the situation in line with other European countries, the Spanish Society for Endocrinology and Nutrition published a comprehensive clinical guideline in 2021,11 and Spanish authorities have presented initiatives to prevent obesity in children.12 Also, in 2024 the Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity, in collaboration with other medical societies, published a guide for the integrated and multidisciplinary management of obesity in adults,10 covering all aspects related to this disease.

Lifestyle changes and physical activity are the main approaches for the management of obesity in Spain, and some obesity management medications (OMMs), such as orlistat and the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) liraglutide, have been available for use since 1998 and 2016, respectively.10 In 2024, the GLP-1 RA semaglutide and the dual GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) RA tirzepatide were also authorised for the treatment of obesity as an adjunct to diet and exercise. However, none of these OMMs are currently approved for reimbursement for the treatment of obesity by the National Health System. Bariatric surgery is indicated in people with a body mass index (BMI) >40kg/m2, or with a BMI ≥35kg/m2 who have high-risk obesity-related complications (ORCs); however, waiting lists for surgery are long, and complications may arise during the surgical procedure.10

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of other chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease, kidney disease and cancer.13 A study in Spain revealed that obesity was strongly associated with cardiovascular risk factors.3 A cohort study based on population-based electronic health records in Catalonia found that higher BMI was associated with an increased risk of 12 cancer types and that longer duration, greater degree and younger age of onset of overweight and obesity during early adulthood were positively associated with a risk of 18 cancers.14

Despite many studies documenting the increase in obesity prevalence in Spain and other European countries,3–7 there are still major uncertainties regarding the demographic and clinical characteristics of people when they are first identified as having obesity or overweight, and the management and care pathways they follow. Although obesity can be treated with lifestyle changes, surgery or OMM, a national clinical care pathway is lacking in Spain, and the proportion of people with obesity who are treated for the disease is unknown.

Data routinely recorded in electronic medical records (EMR) in large population-based healthcare databases could potentially aid in the understanding of the landscape and impact of obesity in healthcare settings, but this resource has not yet been explored systematically. The epIdeMiology landscape and PAtient Care paThways of Obesity (IMPACT-O) study was a multi-national real-world study that used existing healthcare databases to characterise adult people with overweight or obesity in seven European and Asia-Pacific countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Australia and Japan) for the period 2018–2022.15 The initial analyses of the IMPACT-O study found a record of overweight or obesity (documented by BMI records and/or diagnosis codes) in only 11.8% of active individuals in the Spain Longitudinal Patient Database (LPD) during the 2018–2022 period.15 Of these, only 36.5% had a formal diagnosis code indicating overweight or obesity in their records. Further, it found that, in Spain, >80% of people with recorded overweight or obesity have one or more ORCs.

Here we present further analyses of data from the IMPACT-O study in which we characterise the sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of adult people with a first record of overweight/obesity or obesity in the years 2018–2022 in Spain.

Material and methodsStudy designThe IMPACT-O study was a retrospective observational cohort study using EMR and claims databases standardised to the Observed Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) Common Data Model (CDM). Methodologies and multi-country results for those with any record of overweight or obesity during 2018–2022 have been described previously.15 All analyses performed in this study were conducted in accordance with Data Use Agreement terms as specified by the data owner (IQVIA).

This analysis reports country-level data for those with a first record of overweight/obesity or of obesity from the Spain LPD, with data extracted in April 2023 for the study period 1 January 2018 to December 2022. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona (Spain) reviewed and approved the protocol, in accordance with the Royal Decree 957/2020.

Data sourceThe Spain LPD comprises of anonymised EMR collected from software used by primary care providers (PCPs) and other specialists during an office visit to document patients’ clinical records. Patient data are linked and can be followed across PCPs and other selected specialties. Data coverage includes approximately 2.7 million cumulative patients with at least one visit. The average number of active patients in the database (those with at least one record or claim for diagnosis, prescription, procedure, device, measurement or visit to care sites recorded in the database in the last 12 months) was approximately 937,200, so it is estimated that the coverage of the total population of Spain is 5.8%. The data derive from three autonomous regions. Approximately 2300 PCPs and 11,100 other specialists contribute to the database. Dates of service of the database include from 2012 through to the present.

Diagnoses were captured with the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, mapped to Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) diagnosis codes in the OMOP CDM. Drugs were captured as prescription records specific to Spain.

Study populationThe analysis focused on two cohorts of individuals with a first record of overweight or obesity during 2018–2022 (Fig. 1). The overweight/obesity cohort consisted of all people with at least one diagnosis code for overweight/obesity and/or BMI measurement above ≥25kg/m2, as defined by the World Health Organization,16 in the period 2018–2022 (not before). The obesity cohort consisted of all people with at least one diagnosis code and/or BMI measurement above ≥30kg/m2 in the period 2018–2022.

For the overweight/obesity and the obesity cohorts, the index date was defined as the patient's first record, in the study period, of either a diagnosis code or BMI measurement which defined overweight/obesity or obesity, respectively. For both cohorts, subjects were included if ≥18 years of age at index date, with ≥12 months of follow-up before and ≥12 months of follow-up after the index date. Subjects were excluded if data on age or gender were missing, there was a BMI record that indicated non-overweight/obesity or non-obesity within ±30 days from the index date or if there was a BMI record that indicated overweight/obesity or obesity at any time prior to the index date.

VariablesDemographics (age and gender) were captured at index date (Fig. 1). In individuals identified by a diagnosis code for overweight/obesity, BMI was captured within ±60 days of the index date and, if there was >1 recorded measurement, the one on the date closest to the index date was used. BMI was utilised as recorded or as derived from weight and height measurements (BMI=[weight in kg]/[height in meters squared (m2)]). Baseline cardiometabolic parameters (glycated haemoglobin, lipids, estimated glomerular filtration rate) were captured within ±60 days of the index date and, if there was >1 recorded measurement, the one on the date closest to the index date was used.

ORCs were captured within 12 months before index date, including the index date, based on availability of diagnosis codes, or diagnosis codes and medication (where possible to assign medication to a specific disease and available in the database; ORCs identified using diagnosis codes and medication were hypertension, dyslipidaemia, T2D, depression and anxiety). ORCs of interest were pre-established in the study protocol (Supplementary Table S1). Selection of ORCs of interest was guided by previous literature, clinical guidance, and the feasibility of identifying records indicating the presence of an ORC in the study datasets.

The number of clinical visits and the type of physician/specialist documenting the first record was captured at index date (where available). Captured interventions within the 12-month follow-up were lifestyle interventions, pharmacological treatments with an effect on weight (defined as GLP-1 RAs and orlistat) and bariatric surgery, as well as concomitant treatments.

Statistical analysesGiven the descriptive nature of the study, the sample size was determined by the availability of data and the number of subjects retrieved from the database. Analyses were conducted using OMOP analytical tools in Structured Query Language (SQL) through snowflake and R (https://www.r-project.org). Descriptive statistics were reported using frequency and percentage distributions for categorical variables, including percentage of missing data as applicable. Continuous and count variables were described using mean, median and standard deviation (SD). Results are presented for each of the cohorts separately.

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical characteristicsOf a total of 1,570,445 active people in the Spanish LPD database, 50,660 (3.2%) adults had at least one BMI measurement of ≥25kg/m2 and/or diagnosis code of overweight/obesity, and 28,761 (1.8%) adults had at least one BMI measurement of ≥30kg/m2 and/or diagnosis code of obesity. After all inclusion and exclusion criteria had been applied, the number of individuals in the overweight/obesity and obesity cohorts were 25,016 and 13,441, respectively (Fig. 2).

Cohort attrition. The index date was defined as the patient's first record, in the study period, of either a diagnosis code or BMI measurement which defines overweight/obesity or obesity. Active individuals were defined as those who had at least one clinical event (diagnosis, prescription, procedure, device, measurement or visit to care sites) recorded in the last 12 months. BMI, body mass index; LPD, longitudinal patient database.

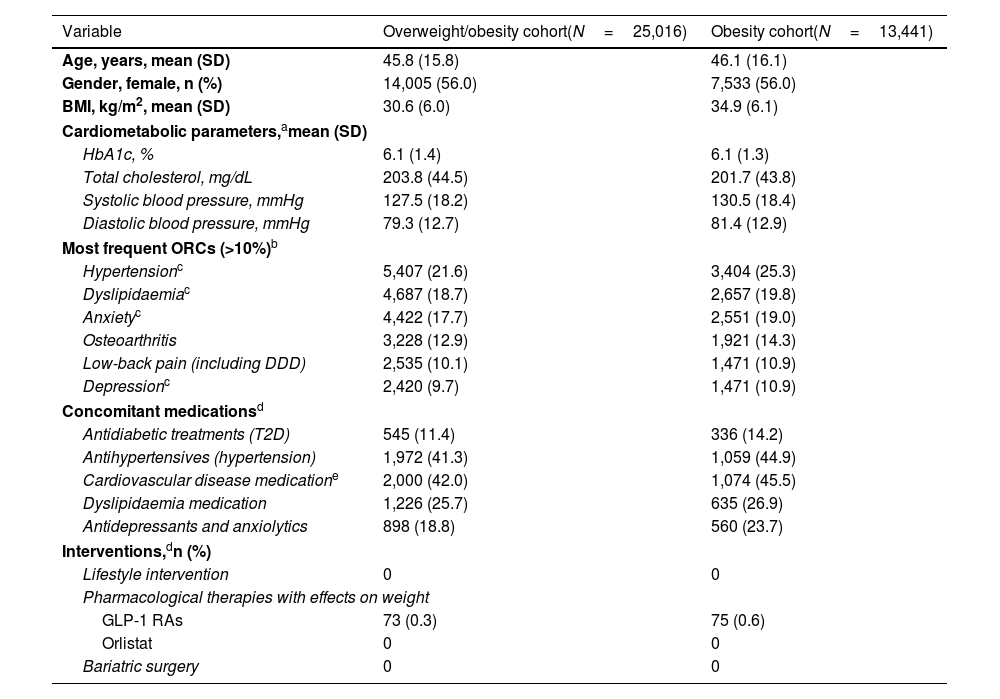

The demographic and clinical characteristics, including cardiometabolic parameters, of both cohorts are shown in Table 1. Adults in the overweight/obesity cohort had a mean (SD) age of 45.8 (15.8) years, were mostly women (56.0%) and had a mean (SD) BMI of 30.6 (6.0) kg/m2. Subjects in the obesity cohort presented with a mean (SD) age of 46.1 (16.1) years and a mean (SD) BMI of 34.9 (6.1) kg/m2. The distribution by BMI ranges for both cohorts is shown in Fig. 3. In the overweight/obesity cohort, 59.1% of subjects presented with a BMI of 25.0 to <30.0kg/m2, and 40.9% a BMI of ≥30.0kg/m2. Only 6.0% had a BMI ≥40.0kg/m2. In the obesity cohort, most subjects (68.2%) had a BMI in the range 30.0 to <35.0kg/m2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of people with overweight/obesity or with obesity (2018–2022).

| Variable | Overweight/obesity cohort(N=25,016) | Obesity cohort(N=13,441) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 45.8 (15.8) | 46.1 (16.1) |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 14,005 (56.0) | 7,533 (56.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.6 (6.0) | 34.9 (6.1) |

| Cardiometabolic parameters,amean (SD) | ||

| HbA1c, % | 6.1 (1.4) | 6.1 (1.3) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 203.8 (44.5) | 201.7 (43.8) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 127.5 (18.2) | 130.5 (18.4) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 79.3 (12.7) | 81.4 (12.9) |

| Most frequent ORCs (>10%)b | ||

| Hypertensionc | 5,407 (21.6) | 3,404 (25.3) |

| Dyslipidaemiac | 4,687 (18.7) | 2,657 (19.8) |

| Anxietyc | 4,422 (17.7) | 2,551 (19.0) |

| Osteoarthritis | 3,228 (12.9) | 1,921 (14.3) |

| Low-back pain (including DDD) | 2,535 (10.1) | 1,471 (10.9) |

| Depressionc | 2,420 (9.7) | 1,471 (10.9) |

| Concomitant medicationsd | ||

| Antidiabetic treatments (T2D) | 545 (11.4) | 336 (14.2) |

| Antihypertensives (hypertension) | 1,972 (41.3) | 1,059 (44.9) |

| Cardiovascular disease medicatione | 2,000 (42.0) | 1,074 (45.5) |

| Dyslipidaemia medication | 1,226 (25.7) | 635 (26.9) |

| Antidepressants and anxiolytics | 898 (18.8) | 560 (23.7) |

| Interventions,dn (%) | ||

| Lifestyle intervention | 0 | 0 |

| Pharmacological therapies with effects on weight | ||

| GLP-1 RAs | 73 (0.3) | 75 (0.6) |

| Orlistat | 0 | 0 |

| Bariatric surgery | 0 | 0 |

BMI, body mass index; DDD, degenerative disc disease; ORCs, obesity-related complications; SD, standard deviation; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Within ±60 days of the index date, closest to index date. For HbA1c, the number of patients with data available were 3,387 and 2,155 for the overweight/obesity and the obesity cohorts, respectively; for total cholesterol, N=9,094 and N=5,205; for systolic blood pressure, N=13,518 and N=6,984; and for diastolic blood pressure, N=13,612 and N=7,037.

Within 1 year before index date, including index date. See full list of ORCs in Supplementary Table S1.

Distribution of BMI ranges in the overweight/obesity and obesity cohorts. Percentages calculated over baseline BMI (within ±60 days of the index date, defined as the patient's first record, in the study period, of either a diagnosis code or BMI measurement which defines overweight/obesity or obesity, respectively) for patients with BMI records: overweight/obesity, N=25,016; obesity, N=13,441. BMI, body mass index.

The type of healthcare professional documenting the first overweight/obesity diagnosis at index date, and the number of clinical visits during the 12-month follow-up period for both cohorts is shown in Supplementary Table S2. As reported in the Spain LPD, the first documentation of overweight/obesity was mainly conducted by PCPs, and in very small proportions (<1%) by other specialists in Obstetrics/Gynaecology or Endocrinology.

Obesity-related complications and interventionsIn the overweight/obesity cohort, 60.1% of subjects presented at least one ORC (Fig. 4). In the obesity cohort 63.6% of subjects presented at least one ORC. Three or more ORCs were identified in 18.8% of subjects in the obesity cohort. The most common ORCs were cardiovascular, present in 30.7% of the overweight/obesity cohort and 33.8% of the obesity cohort (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Of these, hypertension (21.6% and 25.3%, respectively) and dyslipidaemia (18.7% and 19.8%, respectively) were the most frequent. Anxiety (17.7% and 19.0%, respectively) and depression (9.7% and 10.9%, respectively) were highly prevalent in the overweight/obesity and obesity cohorts, and osteoarthritis was also identified in 12.9% and 14.3% of these cohorts, respectively (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). T2D was only reported in 6.5% of the overweight/obesity cohort and 7.8% of the obesity cohort (Supplementary Table S1).

The concomitant medication recorded for subjects in the overweight/obesity and obesity cohorts in the 12-month follow-up reflected the frequency of these diseases and was mainly antihypertensives (41.3% and 44.9%, respectively), medication for cardiovascular disease (42.0% and 45.5%, respectively; treatments included aspirin, statins, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin receptor inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers and diuretics), dyslipidaemia (25.7% and 26.9%, respectively) and antidepressants and anxiolytics (18.8% and 23.7%, respectively) (Table 1).

Regarding pharmacological interventions with effects on weight, GLP-1 RA use was recorded in <1% of the overweight/obesity and obesity cohorts, respectively, in the 12-month follow-up; orlistat was not recorded for any subject in these cohorts (Table 1). Lifestyle interventions and bariatric surgery were not recorded for either cohort.

DiscussionThis study described the demographic and clinical characteristics of new cases of overweight/obesity or obesity at first available record in Spain in the period from 2018 to 2022. The results show that these populations present with a high rate of ORCs, mostly cardiovascular in nature. The study also showed a lack of recording of interventions outside of pharmacological treatment with effects on weight (GLP-1 RAs and orlistat), with no cases of lifestyle interventions or bariatric surgery recorded.

In the present study, we found that the level of recording of overweight/obesity in the Spain LPD likely underestimates the impact of overweight and obesity, as suggested by the previous analysis of the IMPACT-O study.15 The IMPACT-O multi-country analysis of people with any record of overweight or obesity found that only 25.0% of active subjects in Spain in the database had at least one BMI recording, and of the 11.8% of subjects identified with overweight or obesity using BMI and/or a diagnosis code, only 36.5% had a diagnosis code. Low recording rates of BMI and/or diagnosis codes by healthcare professionals could result in the underestimation of the prevalence and incidence of overweight/obesity, as observed in epidemiological studies in Spain and other countries.15,17 For example, the ACTION-IO observational study on the barriers to obesity management in Spain noted that only 44% of all people with obesity had been formally diagnosed.18 Obesity coding is important for early intervention and management, as individuals who receive a recorded diagnosis are more likely to be offered intervention and follow-up for their excess body weight19 and to succeed in weight loss.20 Additionally, poor recording of obesity in databases can lead to an underestimation of its impact on healthcare, resulting in under-funding and reduced prevention efforts.21 Of note, coding for obesity tends to be higher in subjects with concomitant chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease or T2D.

While BMI is useful for population surveys and primary care screening, and to guide nutritional and lifestyle counselling, it must be adjusted for body build, age, and ethnicity.22 Importantly, BMI is a poor predictor of individual chronic disease risk, and it should not be used alone in the prescription of weight-reduction therapies.22 Currently, additional obesity indicators beyond BMI, such as waist circumference or direct fat measurements, have been proposed to improve diagnosis and management.23,24 The Spanish Guide to Comprehensive and Multidisciplinary Management of Obesity in Adults (GIRO) promotes a diagnosis of obesity based on a complete morpho-functional assessment, including anthropometric measurements and especially body composition, along with the evaluation of potential contributing factors and possible complications and comorbidities.10 In this regard, data from the IBERICAN study revealed that a higher percentage of people met the criteria for abdominal obesity compared with BMI ≥30kg/m2 (55.6% versus 33.7%).25 However, these tools for obesity-related risk assessment have not yet been incorporated into routine clinical practice and are rarely recorded in databases.

The subjects in the Spain LPD presented with a high rate of ORCs at their first record of overweight/obesity. Predominant ORCs were cardiovascular, in agreement with previous studies.26,27 The RESOURCE online survey of six European countries showed that the most frequently self-reported ORCs were hypertension (39.3%), dyslipidaemia (22.8%) and T2D (17.5%),28 which are consistent with the present study. Depression and anxiety were also highly frequent in people with overweight and obesity in our study. In this regard, the GIRO guidelines strongly recommend that people with obesity should be screened for depression and other mood disorders.10 The presence of high rates of pre-existing ORCs in the population suggests that these could be triggering the recording of overweight/obesity in these patients. ORCs could be a catalyst for starting discussions of weight management and possible treatments. Individuals who self-identify as having obesity often struggle with their weight for a long time before consulting a healthcare provider about weight management, and this delay may contribute to the onset of obesity-related health conditions.

In the present study, people with overweight or obesity were mostly female (56.0%). Although this sex imbalance was observed in other European EMR databases evaluated in the IMPACT-O study (e.g. Italy, France, UK and Germany), this is in contrast with other epidemiological studies in Spain and elsewhere, which show a higher prevalence in men.8,10 For example, the recent ENE-COVID study, a Spanish nationwide representative survey with 57,131 participants, showed obesity in 19.3% of men versus 18.0% in women, although severe obesity was higher in women.4

At the time the information was recorded in the LPD database (2018–2022), the only drugs approved for the treatment of obesity were liraglutide and orlistat. Currently, the drugs approved by both the European Medicines Agency and the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products for the pharmacological treatment of obesity also include the GLP-1 RA semaglutide 2.4mg and the dual GLP-1/GIP RA tirzepatide.10 The latter was approved in July 2024 as a drug for weight management (including weight loss and maintenance) as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity, in adults with a baseline BMI >30kg/m2 (or >27kg/m2 in the case of comorbidities such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obstructive sleep apnoea, cardiovascular disease, prediabetes or T2D). Real-world evidence studies indicate that, although the use of GLP-1 RAs is recommended in clinical guidelines in Spain for people with T2D and high cardiovascular risk, they are still used mostly in people with high BMI and at advanced stages of T2D.29 In Spain, current regulations provide reimbursement for GLP-1 RAs only to people with T2D and BMI ≥30kg/m2.

Regarding other interventions, such as lifestyle changes and bariatric surgery, these interventions were coded in the Spain LPD; however, no records of these codes were identified in the analysis. Low recording of lifestyle interventions in Spain has been described previously, with diet prescription documented in only 25% of clinical records, and physical activity and behavioural changes documented in <2%.30 That study also showed that patients whose medical records included mention of diet prescription and physical activity and had follow-up visits for those factors had lower BMI and waist circumference; thus, a lack of recording of these aspects of obesity management is likely to lead to suboptimal outcomes. In Spain, treatment of obesity could be mostly or only started in the context of other chronic diseases. Recognition by physicians of the strong complexity of the disease is still lagging.18 Similarly, social stigma and recognition of the disease by people with obesity also adds to the problem. In this regard, a recent study showed that the mean delay in discussing weight for the first time with a physician was 6 years in Spain.18 With respect to the lack of recording of bariatric surgery in the Spain LPD, it is possible that the specialists performing these interventions were not included in the database.

Consistent with other studies, our study suggests that strengthened multidisciplinary and integral approaches are needed to improve the care of people with obesity, including systematic and comprehensive recording of interventions for weight management and data sharing between disciplines/specialties. The IMPACT-O study in Spain included data supplied by both PCPs and other specialists. In this regard, guidelines often recommend an interplay between primary care and other specialised care in the treatment of obesity.

Limitations of the study include the following: as the EMR collected by PCPs and other specialists in the Spain LPD were not originally designed for research purposes, it is possible that they are incomplete or contain errors; some ORCs could be misclassified or poorly recorded, and interventions, such as lifestyle interventions or bariatric surgery, were not recorded in the EMR despite the availability of codes; and as the data were derived from the subjects who visited the PCPs and other specialists associated with the LPD, it may not be fully representative of the Spanish population. Numerous studies have revealed strong disparities between regions in Spain,4,5 and these were not reflected in the LPD, which includes only three autonomous regions. It should be noted that the GLP-1 RA class of drugs was included in the list of pharmacological treatments assessed, although these medications have been marketed and reimbursed until recently only for the treatment of T2D and not obesity. It is not possible to determine whether GLP-1 RAs were prescribed for the treatment of hyperglycaemia or for weight loss in our data sources, due to a lack of data on dosage and indication.

In conclusion, this further analysis of the IMPACT-O study in Spain suggests that the recording of overweight and obesity is suboptimal in Spain. Improvement of the recording of obesity in the databases could help with its management and should be a priority, especially in primary care. Proper recording would increase awareness of obesity as a disease that requires treatment and would provide the basis for follow-up in subsequent primary care visits. The presence of ORCs was high in people even at first record of overweight and obesity identified in the Spain LPD in both overweight/obesity and obesity cohorts. Patient management could be improved with systematic and comprehensive recording of all interventions aimed at obesity control, including structured diet and exercise programmes and bariatric surgery, which were not captured in this database despite the option for recording being available.

FundingThis work was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Conflicts of interestIrene Breton reports receiving consulting fees from Vegenat, Abbott, Nestle, Novo Nordisk, and Eli Lilly; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, abstract (and subsequent poster) writing or educational events from FAES, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Vegenat, and Abbott; and president of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition Foundation (2020–2023). Igotz Aranbarri reports payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, abstract (and subsequent poster) writing or educational events from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Astra Zeneca, and Roche; payment for expert testimony from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Astra Zeneca; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Astra Zeneca; participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Boards from Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Astra Zeneca; and leadership or fiduciary roles in the Fundación RedGDPS. Anastasia Lampropoulou is a former employee and a former minor shareholder of Eli Lilly and Company. Javier Ágreda, Jennifer Redondo-Antón, and Esther Artime are employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. Atif Adam reports no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge Francisco López de Saro and Sheridan Henness (Rx Communications, Mold, UK) for medical writing assistance with the preparation of this manuscript, funded by Eli Lilly and Company.