GLP1 receptor agonists (GLP1-RAs) are currently the most widely used pharmacological option to treat obesity. However, considerable heterogeneity in weight loss response has been observed with different anti-obesity drugs and response predictors to these drugs still remain ambiguous. Furthermore, very few published data have been available on cases of high-responders to treatment with GLP1-RAs. In this article, we present the case of a patient with grade 4 obesity (initial body mass index, 50.2kg/m2) with associated mechanical and metabolic complications who achieved an initial weight loss of 40% at 1 year with hygienic-dietary measures and drug treatment with liraglutide. We also review the available literature on factors potentially contributing to variations in weight loss with GLP1-RAs in general and liraglutide, in particular.

Los agonistas del receptor de GLP1 (AR-GLP1) son la opción farmacológica más empleada en el tratamiento de la obesidad en la actualidad en nuestro medio. Sin embargo, existe una gran heterogeneidad en cuanto a la respuesta en pérdida de peso con los diferentes fármacos antiobesidad y aún no se conocen bien los factores predictores de respuesta a dichos fármacos. Además, hay muy pocos datos publicados sobre casos de súper-respondedores al tratamiento con AR-GLP1. Se presenta el caso de un paciente con obesidad grado 4 (índice de masa corporal inicial 50,2kg/m2) con complicaciones mecánicas y metabólicas asociadas, que consiguió una pérdida del peso inicial del 40% en un año con medidas higiénico/dietéticas y tratamiento farmacológico con liraglutida. Se revisa la literatura sobre los factores que pueden contribuir a las variaciones en la pérdida de peso con AR-GLP1 en general y con liraglutida en particular.

A 56-year-old man was referred to the Endocrinology and Nutrition Department for obesity. The patient had a personal history of hypertension and a family history of obesity from his father's side of the family and brothers, one of whom had undergone bariatric surgery.

Regarding the patient's weight history, he reported weight gain since puberty. He had been on multiple low-calorie diets, which made him lose up to 20kg with a subsequent progressive recovery. In recent years, however, he experienced more significant weight gain, which he attributed to increased anxiety related to work-related stress, reaching his current maximum weight. His dietary records revealed poor eating habits with high consumption of refined and ultra-processed sugars. Aside from being a picky eater, he was tagged as a heavy eater who found it difficult to achieve satiation, especially during periods of increased stress. Moreover, he followed a very sedentary lifestyle.

In the apparatus-guided interrogation, he reported dyspnea on exertion and reduced mobility due to joint overload. He also reported snoring and daytime hypersomnia, with an Epworth scale score of 10/24. His GI symptoms included dyspepsia and constipation.

Initial physical examination revealed a weight of 139.3kg and a height of 1.66m, with a body mass index (BMI) of 50.2kg/m2. Body composition reflected high adiposity, with a fat mass of 48.3%, lean mass of 51.6% and musculoskeletal mass of 35kg. His blood pressure (BP) was 138/84mmHg. Further examination revealed no remarkable findings except for acanthosis nigricans in the skin folds.

Lab test results showed an impaired fasting glucose, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the pre-diabetes range, elevated HOMA index, low high-density lipoprotein levels and vitamin D deficiency. Hemogram, hepatorenal, ferric and thyroid profiles were unaltered, and no albuminuria was detected (Table 1). Liver fibrosis markers were as follows: FIB4, 0.88 (≤1.3); NAFLD Fibrosis Score – 0.45 (≤1.455); and Hepamet Fibrosis Score, 0.02 (≤0.12). Abdominal ultrasound revealed diffuse hepatic steatosis.

Changes in analytical parameters.

| Baseline | At 3 months | At 6 months | At 12 months | At 24 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 103 | 96 | 92 | 88 | 86 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.9 | 5.2 | 5 | 4.9 | 5.2 |

| Insulin (μU/mL) | 27.6 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 3.2 | 4.5 |

| HOMA-IR | 7 | 1.69 | 1.85 | 0.7 | 0.95 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 140 | 124 | 113 | 143 | 141 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | 38 | 36 | 36 | 54 | 55 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | 73 | 75 | 67 | 80 | 77 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 144 | 65 | 49 | 47 | 45 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 1.04 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.1 |

The patient was referred to the Pneumology Department upon clinical suspicion of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA). After confirming diagnosis, non-invasive mechanical ventilation (CPAP at 8cmH2O) was started. He was also assessed by a cardiologist who performed a negative stress test for ischemia. Echocardiography revealed mild left ventricular hypertrophy.

After establishing a diagnosis of grade 4 obesity with complications (hypertension, pre-diabetes, insulin resistance, OSA, metabolic hepatic steatosis and joint overload), bariatric surgery was proposed, an option that was initially ruled out and replaced for hygienic-dietary measures and pharmacological treatment.

The patient was, therefore, referred to a nutritionist for consultation, who subsequently prescribed a dietary plan of 1800kcal divided into four meals based on the Mediterranean dietary pattern. Nutritional education was provided to improve eating habits, working on chewing speed, control of emotional hunger and monitoring by means of a weekly food record. He was also prescribed liraglutide, with up-titration to 1.8mg daily and, 1 capsule of calcifediol 0.266mg monthly.

At the 3-month follow-up, he reported good drug tolerance and a significant feeling of satiety that facilitated a reduction in portion size and eliminated snacking. Physical examination revealed a weight of 104kg, BMI of 37.3kg/m2, fat mass of 42.5%, lean mass of 57.4% and normalization of analytical parameters (Table 1). Given the excellent weight response (−35.3kg; 25.3% with respect to baseline) and good drug tolerance, liraglutide was continued at 1.8mg/day as requested by the patient due to the significant response at that dose. The dietary plan was adapted, emphasising protein intake and increasing strength training to avoid sarcopenia.

The 3-month follow-up consultation revealed a significant change in the patient's dietary pattern, with elimination of refined and processed sugars, increased consumption of fruit and vegetables and excessive restriction of carbohydrates and protein, especially at the end of the day. He walked for 1h daily and did strength training with a personal trainer 3 days a week. Physical examination showed a weight loss of 35.9% in 6 months: weight, 89.3kg; BMI, 31.3kg/m2; waist circumference, 109cm; and fat mass, 27% (Table 2). Lab test results revealed no alterations. Given the significant weight loss, drug discontinuation and imaging modalities were considered to rule out organicity. However, due to his excellent clinical condition, we ultimately decided to maintain treatment (without increasing the dose), actively monitor his weight control every 15 days and optimize his dietary plan to ensure adequate intake of macro and micronutrients, proper hydration and increased protein intake (up to 1.2g of protein/kg/day). Throughout the following weeks, his weight loss slowed down to around 1kg per month, reaching a stable weight of 84kg 6 months after the last visit (12 months of follow-up overall). The patient followed the prescribed dietary guidelines and went jogging almost daily. Clinically, he felt very well and his blood tests showed no abnormalities. CPAP was withdrawn and his liver ultrasound reported normal findings (no steatosis). His BP remained adequate without antihypertensive treatment. Considering the improvement in the patient's condition, liraglutide treatment was discontinued to monitor weight with maintenance purposes. Six months after discontinuation of the drug, his weight remained stable at 83kg with a BMI of 29.4kg/m2 and a waist circumference of 103cm. One year later, his weight remained stable, with a BMI indicating grade 2 overweight, no associated complications and normal blood test results. He followed a healthy Mediterranean dietary pattern and engaged in daily physical exercise, fundamental elements for long-term weight loss maintenance.

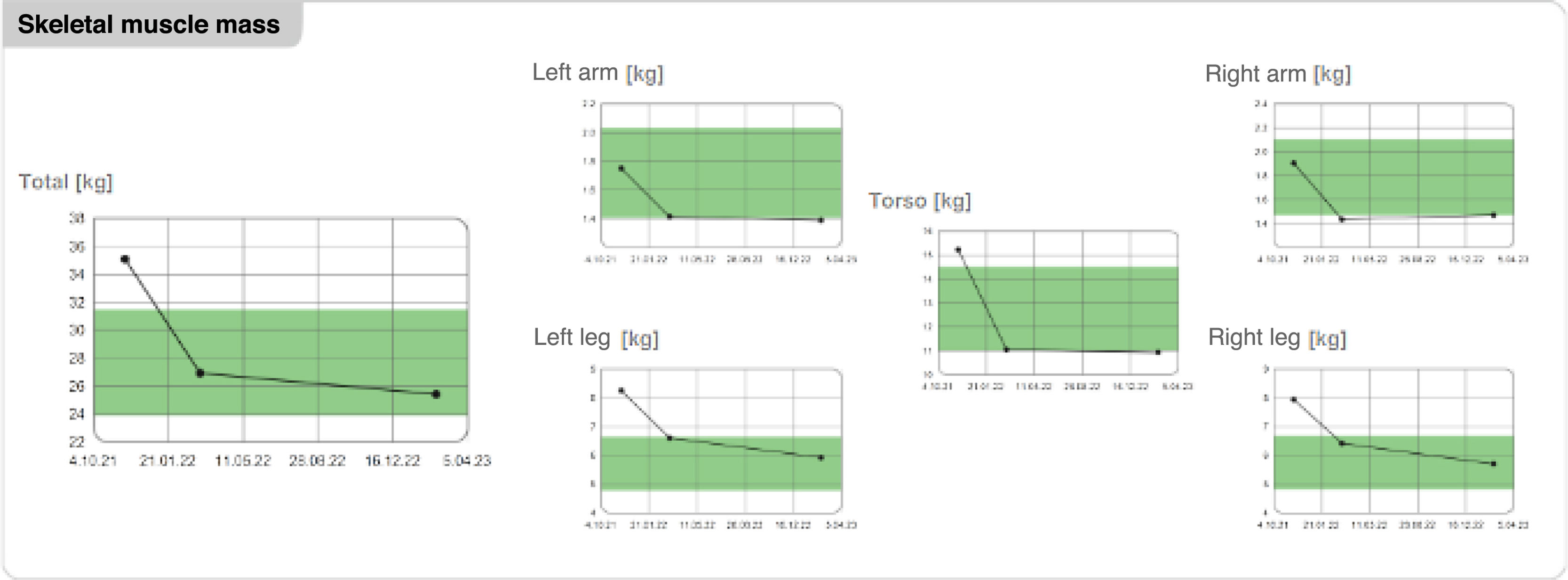

Changes in anthropometric and body composition data.

| Baseline | At 3 months | At 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 139.3 | 104 | 83 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 50.2 | 37.3 | 29.7 |

| Fat mass kg (%) | 66.9 (48.3) | 44.3 (42.5) | 25.1 (30.3) |

| Fat mass index (kg/m2) | 23.9 | 15.9 | 9.0 |

| Lean mass kg (%) | 71.5 (51.6) | 59.9 (57.5) | 57.7 (69.6) |

| Fat-free mass index (kg/m2) | 25.6 | 21.4 | 20.7 |

| Skeletal muscle mass (kg) | 35.1 | 26.9 | 25.4 |

| Right arm | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Left arm | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Right leg | 7.9 | 6.4 | 5.7 |

| Left leg | 8.6 | 6.6 | 5.9 |

| Torso | 15.2 | 11.0 | 10.9 |

| Total body water, L (%) | 52.9 (37.9) | 43.3 (41.2) | 41.9 (50.3) |

We herein present a case involving a male patient experiencing grade 4 obesity (BMI >50kg/m2) with associated metabolic and mechanical complications, in whom bariatric surgery and lifestyle changes were proposed as the treatment of choice due to their greater effect on body weight and improvement in complications, an option that the patient initially rejected.

Studies have shown that surgical treatment of obesity promoted greater weight loss (30–40% depending on the series and surgical technique used); greater reduction in overall, cardiovascular and cancer mortality1; and better improvement/resolution of comorbidities vs conventional optimal medical therapy in subjects with a BMI of ≥35kg/m2.2

Considering the patient did not wish to undergo surgical treatment, pharmacological treatment with liraglutide, a GLP1 receptor agonist (GLP1-RA) approved for obesity at that time in Spain was offered instead. Liraglutide exerts an anorectic action on hypothalamus level, acting on the proopiomelanocortin pathway and inhibiting orexigenic neurons (neuropeptide Y), slowing gastric emptying, and increasing the sensation of fullness and satiety after ingestion.3 Furthermore, GLP1-RA has shown multiple benefits beyond glycemic control and weight loss (e.g. improvements in lipid profile, BP and hepatic steatosis, cardiovascular prevention and nephroprotection) at metabolic and cardio-renal levels. Since the patient had associated pre-diabetes, hypertension, metabolic hepatic steatosis and OSA aside from his eating behaviour, liraglutide was the right choice to improve his comorbidities and induce satiety to promote dietary compliance.

The satiety and clinical adiposity liraglutide evidence obesity and pre-diabetes study revealed that the liraglutide group experienced a weight loss of 8% at 56 weeks, whereas the placebo group experienced a weight loss of 2.6% within that same period.4 Among patients on liraglutide 3mg/day, 77.3% were considered ‘early responders’ (weight loss of ≥5% at 16 weeks on therapy), achieving a weight loss of 10.8% at 56 weeks. Therefore, based on the results published in former studies, weight response 1–4 months after starting the drug has been used to predict long-term weight loss.5,6 Conversely, evidence has shown that liraglutide 3mg/day along with an intensive lifestyle change program promoted even greater weight losses (11.8±1.3%).7 In addition, the weight loss response to GLP1-RAs in people living with obesity, particularly with liraglutide in real-life settings, tends to be equally variable, usually being greater or not inferior to that of clinical trials. It has been reported that up to 14% of responders achieve weight losses ≥25% of their initial weight per year, even with higher degrees of obesity.8 However, the weight loss observed in the current case (40% in one year) was extremely exceptional.

Up-titration studies have indicated that the maximum effectiveness of liraglutide on weight occurs at doses higher than those used in patients with diabetes (3mg/day vs 1.8mg/day, respectively). However, something else we should mention in the current case was the significant weight response achieved without reaching full doses, with a maximum dose of 1.8mg/day having been reached and maintained until the end of treatment.

In addition, high-responders tend to be early responders. The increased weight loss seen among early responders is accompanied by early and marked improvements in cardiometabolic parameters, such as lower baseline glucose, HbA1c and BP levels, and improved lipid profile, as seen in the current case (Table 1).

Nonetheless, up to 25% of the weight loss achieved with low-calorie diets in obese older adults is lean mass. Therefore, to prevent sarcopenia, clinical practice guidelines recommend avoiding very low-calorie diets (recommended calorie restriction range between 200 and 750kcal/day) due to their negative effects on skeletal muscle and bone mineral density and ensuring adequate protein intake (1–1.2g/kg/day), along with a physical activity plan that incorporates resistance exercises to improve strength and preserve muscle mass,9 all of which had been recommended to our patient at the follow-up visits considering the striking weight reduction. Analysis of body composition via bio-impedancemetry showed loss of skeletal muscle mass within the first 3 months after treatment initiation, with subsequent stabilization after intensifying diet and exercise recommendations (Figs. 1 and 2).

We note that the substantial weight loss (40% in 1 year) occurred promoted significant metabolic benefits, namely improvement in hepatic steatosis, resolution of hypertension and OSA and normalization of carbohydrate metabolic parameters, which precluded the need for surgery, a treatment initially indicated given the high adiposity and associated complications.

Areas of uncertaintyAn important aspect to consider in the management of obesity is the existence of substantial heterogeneity in the weight loss response to anti-obesity drug therapy. To date, predictors of individual response to pharmacotherapy have yet to be identified. In addition, hardly any published data have been available on high-responders to GLP1-RA treatment.

A study in overweight and obese women randomized to receive treatment with twice daily exenatide or placebo plus low-calorie diet sought to identify factors contributing to long-term weight loss in hyper-responders. The above-mentioned study classified high-responders and super-responders as patients who experienced weight losses ≥5% and ≥10% at 12 weeks, respectively. Afterwards, they analyzed if age, baseline weight and BMI, waist circumference, total cholesterol and total energy expenditure could possibly predict weight losses >5%. However, none of these variables served as predictors of greater response in weight loss, although super-responders were slightly older and had greater waist circumferences. The authors concluded that earlier and greater weight losses predict super-responder status in both groups and suggested that individuals with higher baseline BMI were more likely to be super-responders.10

Furthermore, former studies have attempted to analyse factors potentially contributing to variations in the weight loss response to liraglutide. Early identification of this response may be beneficial in limiting drug exposure in non-responders and optimizing its benefits in responders.11 Factors associated with greater weight loss with liraglutide included female sex,12–14 absence of diabetes,13,14 high initial body weight15 and, at least, 4% weight loss after 16 weeks on therapy.6 In our case, the patient started at a very high weight, with immediate weight loss response having occurred from the first weeks after starting pharmacological and nutritional treatment. Other covariates that can predict response to treatment included central effects, the presence of nausea, slowed gastric emptying and genotype, whereas initial BMI, race and age seemed to be less relevant in predicting response to liraglutide.11

Regarding central effects, studies have shown that patients on a 16-week regimen of liraglutide experienced lower sugars and fats cravings vs those receiving placebo.16 Likewise, another study showed that a 5-week regimen of liraglutide promoted decreased food intake and pleasure with food17 and that these factors were significantly associated with weight change. Nausea may also predict drug response. In fact, a randomized clinical trial in patients on liraglutide at 3mg/day showed a mean 1-year weight loss of 9.2kg among those who reported nausea and vomiting vs 6.3kg among those who did not.18 One possible explanation is that nausea could be a marker of increased plasma exposure to the drug. Alternatively, several studies have shown that greater slowing of gastric emptying for solids caused by liraglutide was associated with greater weight loss.19,20

Studies have also examined the impact of genotype on weight development. Different responses to low-calorie diets and liraglutide treatment have been associated with genetic variants in the GLP receptor gene.20–22 The most explored genetic variant in obesity and type 2 diabetes is GLP1R (rs6923761). The (A) allele of this variant has been associated with better anthropometric outcomes after 9 months on a hypocaloric diet vs the GG19 genotype. In fact, a pharmacogenomic assay found that the TCF7L2 CC variant promoted greater weight loss with liraglutide than did the CT/TT genotype and that rs69234761 AG/AA did not promote a greater reduction in fat mass vs the GG18 genotype.

Other factors that may influence variability in response to liraglutide treatment include cerebral blood flow, gut hormone levels and dietary adherence.11 A determining factor in the patient's obesity was hyperphagia and the difficulty he had in feeling satisfied, an aspect that substantially improved with the use of drugs and possibly influenced the greater weight loss achieved. Additionally, in this case, a determining factor that conditioned the excellent response to treatment and the maintenance of weight once the drug was discontinued was adherence to dietary guidelines and routine physical exercise. We should mention that with the advances made in the use of anti-obesity drugs, the focus on lifestyle change interventions has evolved significantly, with the incorporation and maintenance of healthy habits such as a balanced diet based on a Mediterranean diet pattern, avoiding sedentary behaviour, promoting physical activity and, adequate nightly rest being crucial to ensuring the success of weight loss and maintaining lost weight in the long-term.

This case provides insights into the weight response of high-responders to the new anti-obesity drugs GLP1-RA (semaglutide 2.4mg weekly) and GLP1-GIP biagonist (tirzepatide). The clinical development program of semaglutide 2.4mg has demonstrated weight losses of 17% at 68 weeks (almost 40% of patients achieved weight losses >20%).23 The SURMOUNT-1 trial confirmed losses of 20.9% with tirzepatide 15mg weekly, while 36.2% of participants achieved weight reductions >25% at the maximum drug dose.24

Therefore, it is expected that new anti-obesity drugs with greater potency in weight loss, improvement in metabolic parameters and, the advantage of weekly administration will gradually replace the use of liraglutide in favour of these drugs. Finally, the recent commercialization of these drugs provides a unique opportunity to enhance the phenotyping of these patients and optimize outcomes in obesity treatment. Likewise, real-world studies could contribute to better identify patients who do not respond adequately to treatment and those who show exceptionally good response. This would allow for a more precise adjustment of adjuvant measures in the management of obesity.

Conclusions and recommendationsWeight loss responses to GLP1-RAs have been considerably variable. Unfortunately, the reasons for these variations still remain poorly understood to this date. Rapid weight losses >4% within the first few weeks after starting liraglutide may predict weight loss at 1 year. Although other factors associated with this response have been explored, further studies are still needed. Therefore, the analysis of factors contributing to the heterogeneity of responses to drug treatment is an area of growing clinical and public health interest.

Similarly, early identification of high-responders is of great interest for providing adequate care in these cases, assessing appropriate drug dose titrations (whether to stop up-titration or reduce dosage) and individualizing nutritional interventions to provide sufficient protein intake. This should be combined with structured physical activity – mainly focused on resistance training – to preserve muscle mass and prevent sarcopenia. Moreover, the importance of the nutritional approach, behavioural changes and close follow-up in the successful results obtained in the current case cannot be understated. Finally, the identification of weight loss predictors would facilitate the personalization of the optimal medical therapy and lifestyle interventions for people living with obesity.