Evaluate the prognostic of the sarcomatous component (homologous vs heterologous).

MethodsThis retrospective study evaluated patients with FIGO I‒IVA Uterine Carcinosarcoma (UCS) treated at a single cancer center. The endpoints were Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DFS) according to the sarcomatous component. The Kaplan-Meier was used for survival analyses. Hazard Ratio (HR) and 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI) were calculated using Cox regression.

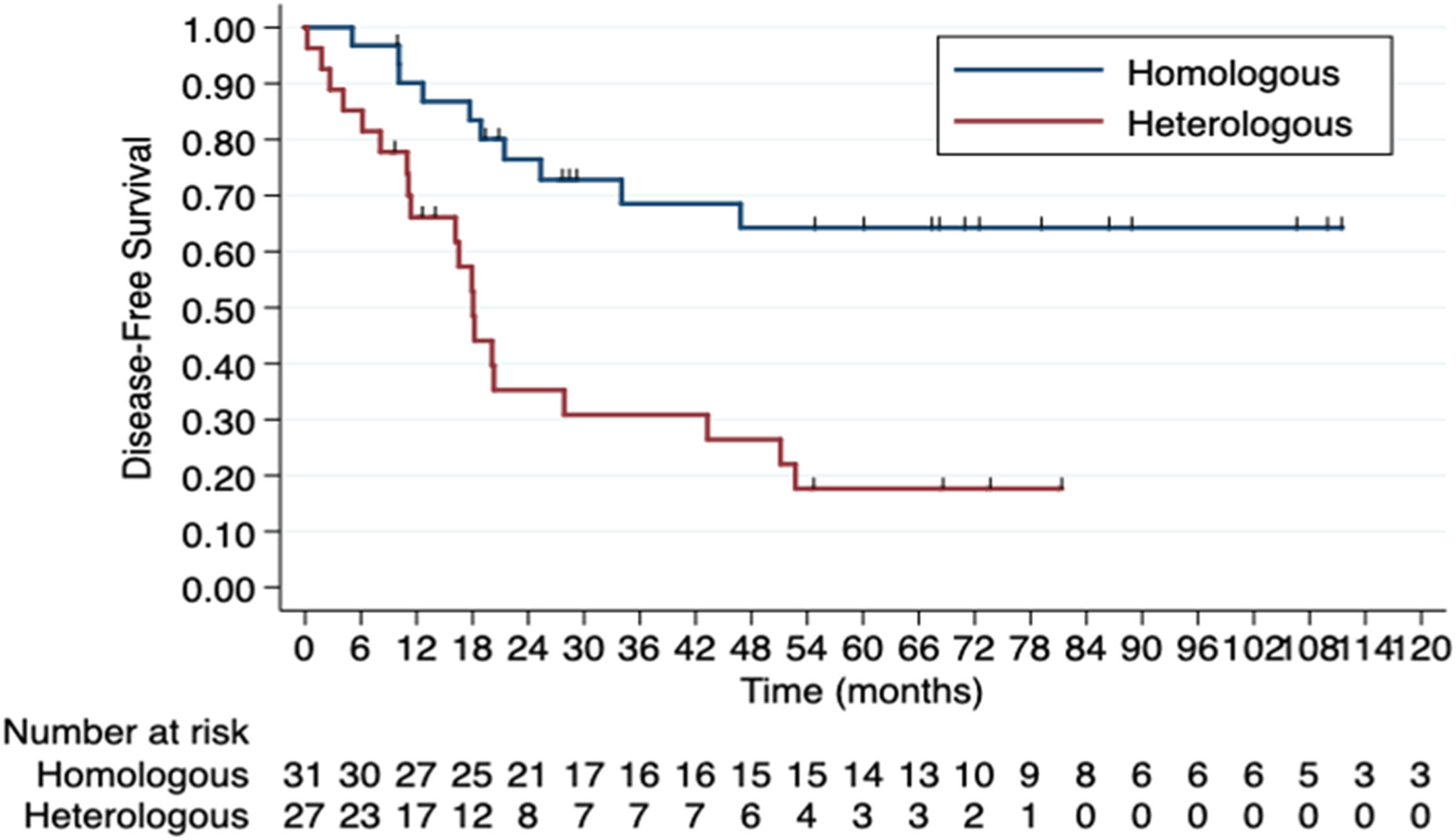

Results61 patients with localized/locally advanced disease (34 homologous vs. 27 heterologous) were included. The most common pathological subtype was Rhabdomyosarcoma (60%) in the heterologous and endometrial stromal sarcoma (95%) in the homologous group. All patients underwent surgery. Adjuvant Chemotherapy (CT) was indicated for approximately 70%. A difference was observed between patients who did not complete adjuvant CT: 32.0% vs. 57.9% in homologous and heterologous groups, respectively (p = 0.03). The main reason for this was recurrence during treatment. Comparing homologous vs. heterologous group, median DFS was 143.2 months vs. 18.0 months (HR = 3.72, 95% CI 1.73‒8.02; p = 0.001) and median OS was 143.2 months vs. 34.4 months (HR = 2.79, 95% CI 1.27‒6.13; p = 0.001), respectively. Heterologous subtype (HR = 4.34, 95% CI 1.59‒11.85, p = 0.004) and FIGO stage III (HR = 3.33, 95% CI 1.18–9.39, p = 0.023) were associated with inferior DFS and OS, while completing adjuvant CT (HR = 0.22, 95% CI 0.07‒0.69, p = 0.009) was associated with superior outcomes.

ConclusionsThe sarcomatous component has a relevant prognostic impact in localized/locally advanced UCS. The heterologous component was associated with a worse DFS and OS. Other negative prognostic factors were FIGO stage III and not completing adjuvant CT.

Uterine Carcinosarcoma (UCS), formerly known as malignant mixed Müllerian tumors, is a rare but highly aggressive neoplasm, accounting for approximately 5 % of all uterine cancers1. Although its incidence is low, it has been increasing over time, reaching 1.36 cases per 100,000 women in the United States in 2017. UCS primarily affects Black and older women, but its occurrence is also rising among younger individuals2.

UCS is a biphasic, high-grade endometrial cancer characterized by both epithelial (carcinomatous) and mesenchymal (sarcomatous) components. The sarcomatous element may be homologous (resembling uterine mesenchymal tissue) or heterologous (non-gynecologic mesenchymal tissue), while the carcinomatous component can be either low- or high-grade3,4.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this dual composition. However, molecular data support the monoclonal hypothesis, suggesting that both components derive from a carcinoma lineage that undergoes sarcomatous dedifferentiation via activation of a stable epithelial-mesenchymal transition3–6.

Given its epithelial origin, UCS is managed similarly to high-grade endometrial carcinoma, with optimal surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy – administered either concurrently or sequentially – even in early-stage, non-metastatic cases7.

Despite this classification, UCS appears biologically distinct from other high-risk histologic subtypes. Although rare, it accounts for 15 % of deaths due to uterine cancers, underscoring its poor prognosis. Even patients with localized or locally advanced disease treated with curative intent face a 5-year overall survival rate of around 50 % and a recurrence rate of 45 %7,8.

The prognostic significance of the sarcomatous and carcinomatous components remains controversial9–12. A clearer understanding of these histologic subtypes may support the development of novel therapeutic strategies. This study aimed to assess the prognostic impact of the sarcomatous component (homologous versus heterologous) in patients with localized or locally advanced UCS.

Material and methodsThis is a single-center retrospective cohort study conducted at Instituto do Cancer do Estado de São Paulo (ICESP), University of São Paulo, Brazil. This study was approved by the local review board (Ethics Committee Opinion, number 6.053.946). The requirement for consent was waived because this was a retrospective study in which most patients died. In accordance with the journal’s guidelines, the authors will provide the data for independent analysis by a selected team by the Editorial Team for the purposes of additional data analysis or for the reproducibility of this study in other centers if such is requested. This manuscript follows the specific guideline for observational studies (STROBE Statement rules).

Patients were selected from an institutional database that included all patients with UCS treated between 2003‒2024. The inclusion criteria were histology-confirmed UCS (central review was not mandatory, but only patients with a description of a homologous or heterologous component were included), FIGO I‒IVA, age ≥ 18-years, Eastern Cooperative Oncologic Group Performance Status Scale (ECOG-PS) 0‒2. The exclusion criteria were metastatic disease (FIGO IVB) or diagnosis of pure epithelial endometrial cancer or pure uterine sarcoma.

The study population was divided into two groups according to the presence of homologous or heterologous sarcomatous components. The homologous sarcomatous subtype included the endometrial stromal sarcomas and the leiomyosarcomas, while the heterologous subgroup included chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and liposarcoma5. The epithelial component was classified into two groups: endometrioid (grades 1‒3) and non-endometrioid (serous, clear cell, squamous cell, undifferentiated, and mixed serous and clear cell carcinoma).

Data on patients' demographics, surgical and histopathological features, and clinical outcomes were retrieved from hospital records. Age at diagnosis, Body Mass Index (BMI), staging according to the FIGO 2009, tumor diameter, myometrial/cervical invasion, Lymphovascular Space Invasion (LVSI), adjuvant treatments, recurrence status, date of last follow-up, date of recurrence, and time of death were recorded.

Endpoints were Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DFS) according to the sarcomatous component (homologous vs. heterologous). DFS was calculated from the diagnosis (hysteroscopic or surgical) until the disease recurrence or progression. OS was calculated from the diagnosis to death from any cause. Patients without the events were censored at the time of last follow-up.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the tendency and dispersion measurements. Frequencies were compared using the Chi-Square test. Kaplan-Meier was used to estimate survival, and curves were compared using a log-rank test. Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95 % Confidence Intervals (95 % CIs) were calculated for each comparison using Cox regression. Statistical significance was considered if p < 0.05. Univariable and multivariable analyses were performed when appropriate. For the multivariable analysis, variables were included if they were deemed clinically relevant and had a p-value ≤ 0.1 in the univariable analysis. Statistical calculations were performed using a standard software package (STATA version 15.0, StataCorp, Texas, USA).

ResultsA total of 1842 patients diagnosed with ICD-10 code C54 (Malignant Neoplasm of the Corpus Uteri) were treated at the institution between 2003 and 2024 (Flowchart in Fig. S1, Supplementary Data). Of these, patients with histological diagnoses other than carcinosarcoma and those whose pathology reports lacked documentation of homologous or heterologous components were excluded. Consequently, 85 patients with UCS were identified (45 homologous and 40 heterologous). Of these, 61 patients had localized/locally advanced disease (FIGO I‒IVA), 34 of which were homologous (Group 1) and 27 heterologous (Group 2). The two groups did not differ in terms of age, ethnic origin (most of them White), ECOG-PS, or FIGO stage (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients.

| Variables | Sarcomatous component | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous (n = 34) | Heterologous (n = 27) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), years | 70.5 (53.9 – 79.7) | 67.8 (51.5 – 85.6) | 0.98a |

| Ethnic origin, n ( %) | 1.00b | ||

| White | 25 (73.5) | 21 (77.8) | |

| Black | 3 (8.8) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Other | 4 (11.8) | 4 (14.8) | |

| Not available | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ECOG-PS, n ( %) | 0.09b | ||

| 0 | 20 (59.4) | 15 (55.6) | |

| 1 | 12 (34.4) | 6 (22.2) | |

| 2 | 1 (3.1) | 6 (22.2) | |

| 3 | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 27.2 (22.3 – 38.2) | 29.7 (19.9 – 44.3) | 0.06a |

| Surgical treatment | 34 (100.0) | 27 (100.0) | 1.00a |

| Hysterectomy | 2 (5.9) | 2 (7.4)c | |

| Hysterectomy + BSO | 32 (94.1) | 25 (92.6) | |

| Pelvic lymphadenectomy (complementary) | 25 (73.5) | 20 (74.0) | |

| Para-aortic lymphadenectomy (complementary) | 19 (55.9) | 16 (59.2) | |

| FIGO stage | 0.99a | ||

| I | 12 (35.3) | 11 (40.8) | |

| II | 5 (14.7) | 3 (11.1) | |

| III | 15 (44.1) | 12 (44.4) | |

| IVA | 2 (5.9) | 1 (3.7) | |

IQR, Interquartile Range, BMI, Body Mass Index; BSO, Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy.

Regarding the treatment employed after diagnosis, all patients underwent surgical treatment, with no difference between the groups (Table 1). Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was the most common surgical treatment, performed in 32 (94.1 %) patients in Group 1 and 25 (92.6 %) patients in Group 2. Pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed in 73.5 % and 74.0 % of patients, and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in 55.8 % and 59.2 % of patients in homologous and heterologous groups, respectively.

Among the homologous group, the most common histological subtype was endometrial stromal sarcomas (94.1 %). Among the heterologous group, most patients presented with Rhabdomyosarcoma (55.5 %), as described in Table 2. Regarding the epithelial component, the most common histology was endometrioid in Group 1 and serous in Group 2, but with no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Approximately 60 % of patients in both groups presented LVSI and depth of myometrial invasion ≥ 50 % (Table 2).

Histological features.

| Variables | Sarcomatous component | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous (n = 34) | Heterologous (n = 27) | ||

| Epithelial component, n ( %) | |||

| Endometrioid | 16 (47.06) | 10 (37.04) | 0.450 |

| Serous | 13 (38.24) | 11 (40.74) | 1.000 |

| Clear cell | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.70) | 0.443 |

| Squamous | 3 (8.82) | 3 (11.11) | 1.000 |

| Neuroendocrine differentiation/ Small cells | 0 (0.00) | 3 (11.11) | 0.081 |

| Undifferentiated | 2 (5.88) | 2 (7.41) | 1.000 |

| Not available | 5 (14.71) | 1 (3.70) | 0.214 |

| Type of homologous, n ( %) | |||

| Endometrial stromal sarcomas | 32 (94.12) | ‒ | ‒ |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1 (2.94) | ‒ | ‒ |

| Undifferentiated | 1 (2.94) | ‒ | ‒ |

| Type of heterologous, n ( %) | |||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | ‒ | 15 (55.56) | ‒ |

| Condrosarcoma | ‒ | 11 (40.74) | |

| Osteosarcoma | ‒ | 2 (7.41) | ‒ |

| Liposarcoma | ‒ | 1 (3.70) | ‒ |

| Fibrosarcoma | ‒ | 1 (3.70) | ‒ |

| Not available | ‒ | 1 (3.70) | ‒ |

| Depth of myometrial invasion | 0.695 | ||

| < 50 % | 6 (17.65) | 7 (25.93) | |

| ≥ 50 % | 23 (67.65) | 18 (66.67) | |

| Without | 1 (2.94) | 1 (3.70) | |

| Not available | 4 (11.76) | 1 (3.70) | |

| LVSI | 21 (61.76) | 16 (61.54) | 1.000 |

| PNI | 7 (21.88) | 8 (30.77) | 0.550 |

LVSI, Lymphovascular Space Invasion; PNI, Perineural Invasion.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy (CT) was indicated for 25 (73.5 %) and 19 (70.3 %) patients in homologous and heterologous groups (p = 0.77), respectively. Carboplatin-Paclitaxel was the most common CT regimen in both groups, performed in 92 % (Group 1) and 100 % (Group 2) of patients (p = 0.50). A significant difference was observed between women who did not complete adjuvant CT: 8 (32.0 %) in the homologous group and 11 (57.9 %) in the heterologous group (p = 0.03). The main reason for not completing CT was recurrence during treatment (none patients in the homologous group vs. six patients in the heterologous group). A difference was also found in the use of adjuvant external radiotherapy (p = 0.01): 27 (79.4 %) in the Group 1 vs. 14 (51.8 %) in the Group 2, which is also explained by the proportion that recurred prior to Radiotherapy (RT) in Group 2.

The most frequent recurrence pattern was distant metastases: 5 (14.7 %) patients in the homologous group vs. 14 (51.8 %) patients in the heterologous group (p = 0.002). The lung was the most common site of recurrence. Details of adjuvant treatment and recurrence patterns were comparable in the two groups in the Supplementary Data (Table S1).

In the whole series, median DFS and OS were 43.2-months and 56.2-months, respectively. The 5-year DFS and OS rates were 27.9 % and 31.1 %, respectively.

When comparing groups 1 and 2 separately, median DFS was 143.2-months in the homologous group and 18.0-months in the heterologous group (HR = 3.72, 95 % CI 1.73‒8.02; p = 0.001) (Fig. 1). The 5-year DFS rates were 45.2 % (Group 1) vs. 11.1 % (Group 2). There was also a difference in median OS: 143.2-months in the homologous group and 34.4-months in the heterologous group (HR = 2.79, 95 % CI 1.27‒6.13; p = 0.01) (Fig. 2). The 5-year OS rates were 41.2 % (Group 1) vs. 18.5 % (Group 2).

For the DFS analysis, the observed Hazard Ratio (HR) of 3.72 in a sample of 61 patients (27 in the heterologous group and 34 in the homologous group), with a two-sided alpha of 0.05, yields an estimated statistical power of 99.8 %. For OS, using similar parameters and an HR of 2.79, the estimated power was 97.2 %.

Univariable and multivariable analyses for DFS and OS are described in Table S2 (Supplementary Data) and Table 3, respectively.

Cox regression analysis of clinicopathologic factors for OS in UCS: univariable and multivariable analysis.

CT, Chemotherapy; HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval.

At univariable analysis, the presence of heterologous subtype and FIGO stage III demonstrated a negative impact on OS and DFS, whereas completed adjuvant CT and radiotherapy showed a positive impact (Table S2 and 3). Brachytherapy demonstrated a positive impact only on DFS.

At multivariable analysis, heterologous subtype (HR = 4.34, 95 % CI 1.59‒11.85, p = 0.004) and FIGO stage III (HR = 3.33, 95 % CI 1.18–9.39, p = 0.02) were identified as factors associated with inferior DFS and OS, while completing adjuvant CT (HR = 0.22, 95 % CI 0.07‒0.69, p = 0.009) was the sole factor associated with superior outcomes (Tables S2 and 3).

DiscussionSummary of main resultsPatients diagnosed with UCS and a heterologous sarcomatous component presented an inferior DFS and OS when compared to patients with a homologous component. In multivariable analysis, the heterologous component was confirmed as an independent risk factor for DFS and OS.

Results in the context of published literatureIt is known that UCS patients have a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 25 %‒30 % in previous studies4,7,13. The present results are consistent with the literature, with a 5-year OS rate of 31.1 % for patients with localized and locally advanced disease.

Given that treatment of these patients follows the risk-based guidelines defined for pure epithelial endometrial tumors, without any histology-based management adjustments, it is essential to identify other possible prognostic biomarkers to help find possible strategies to tailor peri‑ and post-operative management7.

Several studies have evaluated the prognostic impact of the carcinomatous and the sarcomatous components, obtaining controversial results9–12,14. Nordal et al9. evaluated 46 UCS (23 with a homologous and 23 with a heterologous component) and demonstrated a 5-year OS rate of 31 % and a less favorable prognosis (p = 0.027) for the carcinomatous component (serous or clear cell) in multivariable analysis, with no difference between homologous and heterologous tumors (p = 0.39). Other studies tend to indicate a worse prognosis for the sarcomatous element10,11,14. Abdulfatah et al14. evaluated 196 UCS to identify potential prognostic factors. Sarcoma dominance was a significant independent predictor of shorter disease-free interval in multivariable analysis (p = 0.012), and rhabdomyoblastic differentiation was an independent predictor of worse 3-year OS rate (p = 0.009).

In the present study, the carcinomatous component was not associated as an independent risk factor for DFS and OS. However, in the multivariable analysis, the sarcomatous subtype was a negative predictor for DFS and OS, increasing the risk of death by 4 times (Table 3).

Rhabdomyosarcoma was the most common histological sarcomatous subtype in the heterologous group. Type 2 epithelial histotype (serous, clear cell, undifferentiated) was numerically higher in the heterologous, with serous carcinoma being the most common epithelial component in Group 2. Rosati et al15. also identified this association between the non-endometrial epithelial component and the heterologous sarcomatous component (47.0 % of type 2 epithelial histotype in heterologous vs. 27.0 % in homologous group). Despite this difference, the authors did not observe an impact of the histologic subtype of epithelial component on survival, once again favoring the sarcomatous component as the main element associated with the prognosis of these patients.

Regarding the main analysis of the present study, the heterologous component was associated with worse DFS and OS when compared to the homologous element, with a fourfold risk of death (HR = 4.3, 95 % CI 1.6‒11.9; p = 0.004) and recurrence (HR = 4.0, 95 % CI 1.6‒9.9; p = 0.003).

Although some studies do not demonstrate this impact11, the present data are consistent with others that have shown worse outcomes for the heterologous components in patients with different stages14–17. Rosati et al15. evaluated 95 women with early-stage UCS (63.2 % homologous and 36.8 % heterologous) and showed that only the heterologous component was a significant negative prognostic factor on OS (HR = 1.95; 95 % CI 1.03‒3.68; p = 0.04). Can et al16. performed a similar analysis with 98 patients with all UCS stages (74.5 % homologous and 25.5 % heterologous) and demonstrated a reduction in OS associated with the heterologous component (OR = 2.86; 95 % CI 1.19‒6.84; p = 0.01).

The studied population had a median age (70.5-years) consistent with the peak incidence between 70‒79 years described in the literature7, with a numerically lower age at UCS onset for the heterologous group (Table 1).

Due to the rarity of the disease and current evidence largely coming from non-randomized studies, the benefit of adjuvant therapy is not fully understood. UCS is generally treated with concurrent or sequential adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy (aCRT), which has reduced the risk of recurrence and improved survival rates at all stages7. Odei et al18. retrospectively evaluated 1787 patients with UCS who received adjuvant CT and 1751 who underwent aCRT. When compared with CT alone, aCRT was associated with a significant OS benefit (31.3-months vs. 24-months; HR = 0.65, p < 0.01).

Regarding the CT regimen, a 2013 Cochrane review19 of data from large phase III trials in UCS (n = 579) established Paclitaxel-Ifosfamide as the standard regimen for the treatment of UCS, but with important limitations as the increased risk of central neurologic toxicity. The phase III noninferiority GOG-261 Trial20 randomized patients to receive Carboplatin-Paclitaxel (n = 228) or Paclitaxel-Ifosfamide (n = 221). Carboplatin-Paclitaxel was not inferior, with a median OS of 37-months vs. 29-months (HR = 0.87; 90 % CI 0.70‒1.07; p < 0.01 for noninferiority; p > 0.1 for superiority) and a different pattern of toxicity.

Based on these studies, most of the patients indicated for adjuvant treatment received sequential aCRT, with the most common regimen being Carboplatin-Paclitaxel. More patients in Group 1 completed the scheduled chemotherapy than those in Group 2, and the main hypothesis for this difference is the greater early recurrence observed in the heterologous group. Probably for this same reason, the authors also found a difference in the use of RT, which was higher in Group 1.

In the multivariable analysis, completion of adjuvant CT was an independent risk factor for improving OS and DFS (Tables S2 and 3), in agreement with the literature17,21. Guttman et al21. reviewed 906 cases of UCS stages I‒IV in the USA and Japan, which underwent primary surgical staging. Of these, 67.1 % received postoperative CT (88.5 % with platinum agent), and in multivariable analysis, only postoperative CT remained an independent predictor for improved progression-free survival (HR = 0.34; 95 % CI 0.27‒0.43; p < 0.001).

It is possible that the observed benefit of completing CT reflects, at least in part, the inherently more aggressive biology and potentially lower chemosensitivity of the heterologous subtype. Since all patients in Group 2 received Carboplatin-Paclitaxel – a regimen more established for epithelial histologies – its limited efficacy in sarcomatous components may have contributed to early progression and treatment interruption. This raises the hypothesis that alternatives should be explored in future trials for patients with heterologous histology.

The impact of RT on outcomes was not maintained in the multivariable analysis, contrary to some studies, such as that by Can et al16, in which adjuvant RT (performed in 62.2 % of patients) was found to significantly increase OS and DFS. In the present study, 51.8 % of patients in the heterologous group underwent adjuvant RT vs. 79.4 % in the homologous group, most of them sequentially after CT. The present study’s hypothesis is that this discrepancy could be attributed to earlier recurrence in the heterologous group, which occurred between the sequential CT and RT, removing the indication for RT.

Indeed, disease progression during adjuvant therapy is an additional indicator of the poor prognosis associated with the presence of a heterologous component. The authors performed a stratified Cox regression analysis based on treatment completion. The results remained consistent: for DFS, the stratified HR was 4.30 (95 % CI 1.65–11.18; p = 0.003); and for OS, the stratified HR was 3.73 (95 % CI 1.41–9.80; p = 0.007). This again suggests a worse prognosis for this group, raising the idea that the adjuvant treatment of these patients should be rethought.

Almost 70 % and 50 % of patients underwent pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomies, respectively. FIGO III was associated with worse outcomes in multivariable analysis, consistent with the literature, with FIGO stage being considered the most reliable prognostic factor15,16. However, there was no impact for complementary lymphadenectomy in the present data, contrary to studies that described a positive effect on OS16,22, possibly because most patients in both groups received complementary lymphadenectomy.

Strengths and weaknessesTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the negative prognostic impact of the heterologous sarcomatous component on both DFS and OS in patients with localized and locally advanced disease (FIGO I‒IVA) in Latin America, representing real-world data from patients in this continent.

The main limitation of this study is the fact that it is a retrospective cohort study conducted in a single center. Another limitation is the relatively small sample size (61 eligible patients) and the limited number of deaths in the homologous group, which may have resulted in an overestimation of the OS in this group (143.2-months) due to censoring. The small sample size could limit the statistical power to detect clinically relevant differences between the groups. However, after calculating the power of the study, the authors confirmed that the analyses had adequate statistical power to detect the observed differences.

Implications for practice and future researchThese data point to the need to reconsider the central role of the sarcomatous component for the modulation of the follow-up schedule and the adjuvant therapy, since, in addition to FIGO stage and completed CT, only the heterologous sarcomatous component was associated with worse outcomes, presenting lower OS and DFS than the homologous component in survival analyses.

Future research should be developed considering the poor prognosis of these patients with a heterologous sarcomatous component, in order to improve their therapeutic approach.

ConclusionThe sarcomatous component has a relevant negative prognostic impact in localized/locally advanced UCS. In this cohort, the heterologous component was associated with a considerably worse DFS and OS, highlighting the need to reconsider the role of the sarcomatous component in future research to personalize the therapeutic approach to these patients. Other negative prognostic factors were FIGO stage III and not completing adjuvant CT.

Previous presentationThis study was previously presented as a poster meeting on “Congresso Brasileiro de Oncologia 2024″.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statementDaniel Santos Rocha Sobral Filho: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Giulia Mazaro de Oliveira: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Letícia Vecchi Leis: Writing – original draft, Visualization. Mariana de Paiva Batista: Writing – review & editing. Vanessa da Costa Miranda: Writing – review & editing. Renata Colombo Bonadio: Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision. Maria del Pilar Estevez Diz: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Samantha Cabral Severino da Costa: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Project administration.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.