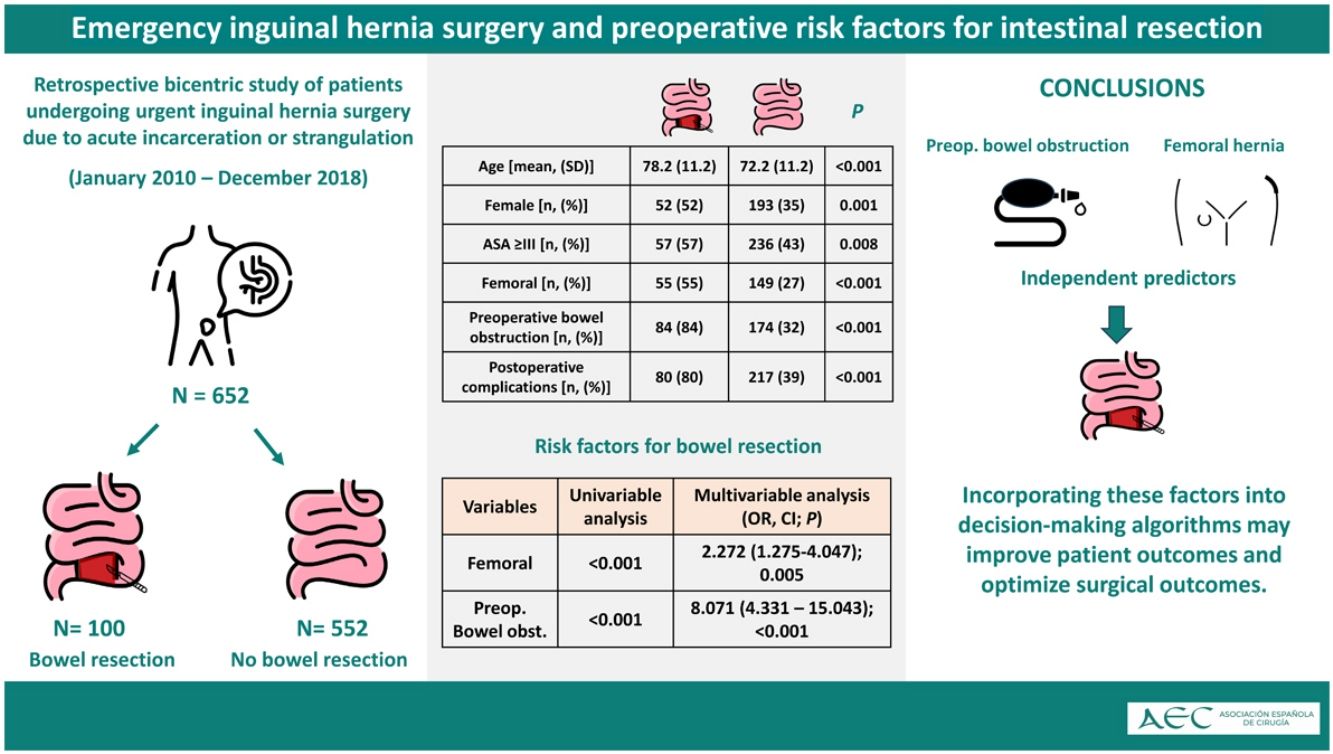

Management strategies for acute irreducible hernias vary, with recent debates on the role of manual reduction versus immediate surgery. This study aimed to identify preoperative risk factors for bowel resection in acute irreducible inguinal hernias.

MethodsA retrospective cohort study included patients from 2 university hospitals who underwent emergency surgery for acute irreducible hernias between January 2010 and December 2018.

ResultsOut of a total of 652 patients, 15% required intestinal resection; females, older individuals, and those with comorbidities were more likely to undergo resection. Multivariate analysis identified patients with femoral hernia (OR 2.272; 95%CI 1.275–4.047; P = .005) and preoperative intestinal obstruction (OR 8.071; 95%CI 4.331–15.043; P < .001). Patients needing resection experienced higher postoperative complication rates and longer hospital stays.

DiscussionFemoral hernia and preoperative intestinal obstruction were independent predictors of bowel resection in acute irreducible hernias. Incorporating these factors into decision-making algorithms may improve patient outcomes and optimize surgical management.

Las estrategias de manejo para las hernias irreducibles agudas varían, y recientemente se ha debatido sobre el papel de la reducción manual frente a la cirugía inmediata. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo identificar los factores de riesgo preoperatorios para la resección intestinal en hernias inguinales irreducibles agudas.

MétodosUn estudio de cohorte retrospectivo incluyó pacientes de dos hospitales universitarios que se sometieron a cirugía de emergencia por hernias irreducibles agudas entre enero de 2010 y diciembre de 2018.

ResultadosDe un total de 652 pacientes, el 15 % requirió resección intestinal, y las mujeres, los individuos de mayor edad y aquellos con comorbilidades tuvieron más probabilidades de someterse a una resección. El análisis multivariado identificó pacientes con hernia femoral (OR, 2,272; IC del 95 %, 1,275-4,047; P = 0,005) y obstrucción intestinal preoperatoria (OR, 8,071; IC del 95 %, 4,331-15,043; P < 0,001). Los pacientes que necesitaron resección experimentaron mayores tasas de complicaciones posoperatorias y estancias hospitalarias más prolongadas.

DiscusiónLa hernia femoral y la obstrucción intestinal preoperatoria fueron predictores independientes de resección intestinal en hernias irreductibles agudas. La incorporación de estos factores en los algoritmos de toma de decisiones puede mejorar los resultados de los pacientes y optimizar el tratamiento quirúrgico.

Acute incarceration of an inguinal hernia is one of the most common causes of acute abdomen.1 Approximately 5%–15% of patients with inguinal hernias will require emergency surgery for acute incarceration.2 Furthermore, up to 38% of patients with acute incarceration of inguinal hernia require intestinal resection,3 which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.4 Although several predictors of intestinal ischemia and bowel resection have been identified among patients with acute incarceration, this diagnosis remains challenging for emergency surgeons.5

Moreover, the management of acute incarceration of an inguinal hernia remains a topic of debate. While clinical guidelines consider this condition to be an indication for emergency surgery, a recent guideline update suggested changing the name of acute incarceration to acute irreducible hernia and manual reduction for all hernias that do not have suspicion of intestinal ischemia.6,7 Early identification of the need for intestinal resection is essential to establish appropriate management and strategy in these patients.

The objective of this study was to identify preoperative risk factors for intestinal resection in patients with acute irreducible hernias who underwent emergency surgery.

MethodsStudy design and settingThis is a retrospective cohort study of prospectively collected data from patients who underwent emergency surgery for acute irreducible hernia at 2 Spanish university hospitals. The study design was performed in accordance with the STROBE statement.8

This retrospective study used anonymized data from routine clinical practice and did not require approval from an ethics committee, in accordance with local regulations. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

PatientsPatients who met the following criteria were included: a) were over 18 years of age; and b) had acute irreducible hernia following surgery. Acute irreducible hernia was defined as a hernia in which the contents could not be reduced on physical examination but were previously reducible prior to the acute onset of symptoms.7

Patients who had undergone elective surgery after manual reduction of hernia contents were excluded.

Patients were followed up by their surgeons at regular intervals. Generally, one in-person visit was performed 2 weeks after hospital discharge, and further in-person visits were conducted based on clinical needs. The data were collected through a retrospective review of medical records and operative records.

Preoperative variablesWe collected data for both demographic variables (age, sex, body mass index) and clinical variables for all patients, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, Charlson score,9 and presence of comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, neurocognitive disorders, and liver cirrhosis. Clinical or radiological evidence of preoperative intestinal obstruction was also collected. All patients underwent a standard preoperative abdominal x-ray as part of their diagnostic evaluation. However, data on the use of computed tomography (CT) scans were not collected systematically, and information regarding which patients underwent CT imaging is unavailable. The duration of acute irreducible hernia was defined as the time in hours elapsed from the onset of the acute episode described by the patient until admission to the emergency department. For analysis, this was categorized as <24 h or ≥24 h. Variables related to the hernia, side of the hernia and type of hernia (based on the EHS classification) were included.6

Operative variablesThe operative details collected included the need to perform bowel resection, type of anesthesia, type of repair (mesh or tissue), type of open approach (anterior or posterior), and intraoperative complications. The type of repair, the criteria for performing a midline laparotomy, and the decision to perform bowel resection were at the discretion of the surgeon. The type of anesthesia used was selected at the discretion of the anesthesiologist.

Postoperative variablesThe postoperative variables evaluated were length of hospital stay (admission to discharge) and postoperative complications (within the first 90 postoperative days). Postoperative complications were defined as any condition that could prolong the hospital stay or impact outcomes. Complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo (CD) grading system.10 Wound morbidity was evaluated by analyzing the presence of surgical site occurrences (SSO). SSO was classified as surgical site infection, wound dehiscence, enterocutaneous fistula, wound cellulitis, nonhealing incisional wound, skin or soft tissue ischemia, skin or soft tissue necrosis, serous or purulent drainage from the wound, stitch abscess, seroma, hematoma, and infected or exposed mesh.11

Statistical analysisContinuous variables are reported as the means and standard deviations (SDs) and were analyzed using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test as needed. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages and were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact-test as needed. A logistic regression model was built for bowel resection and included variables that were found to be significant in the univariate analysis (P < 0.05). The results of bowel resection are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS (IBMS SPSS Statistics 23) was used for the statistical analysis.

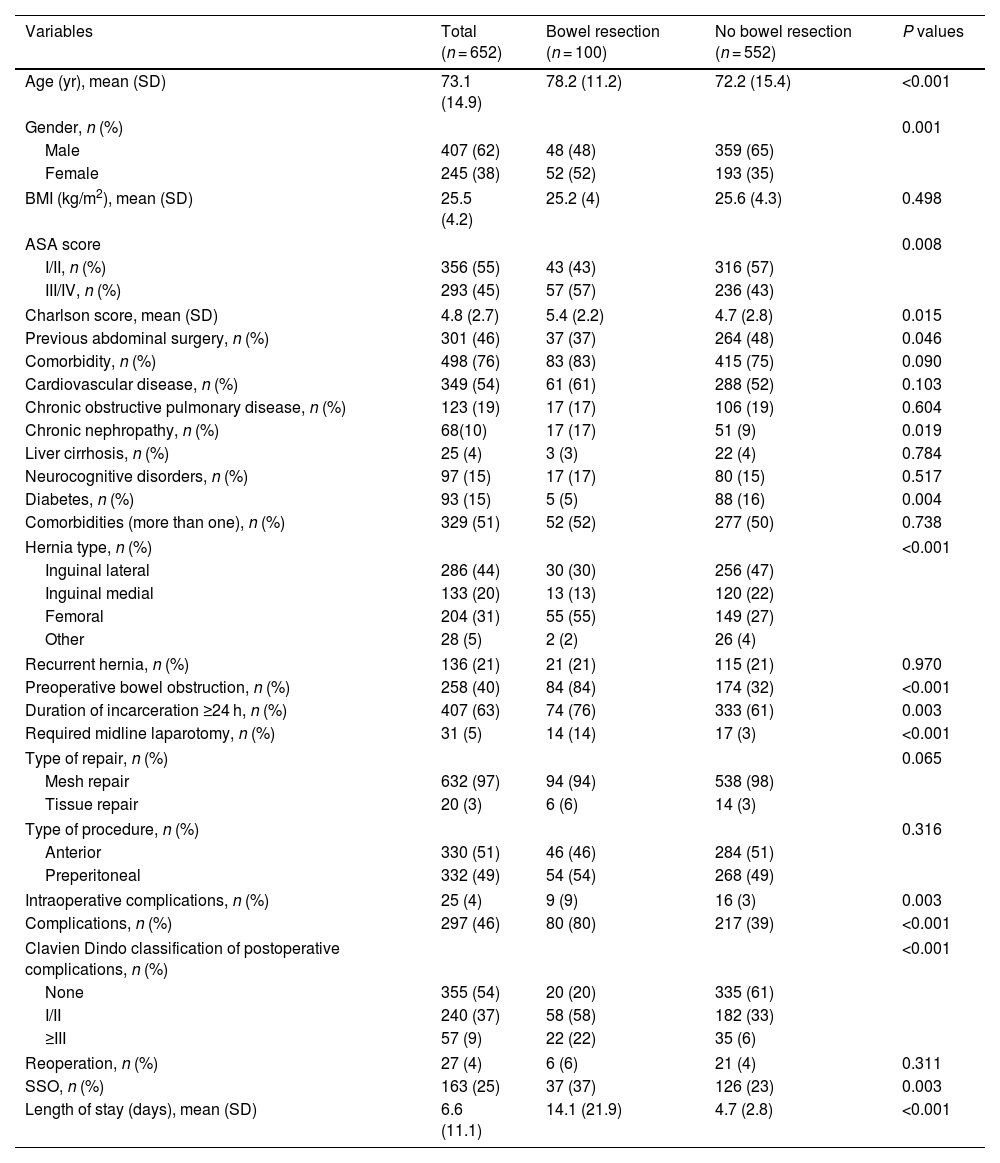

ResultsPatient characteristicsFrom January 2010 to December 2018, a total of 652 patients underwent emergency inguinal hernia surgery at 2 university hospitals, 100 (15%) of whom required intestinal resection. All repairs were unilateral and repaired using open techniques. In terms of demographic variables, in the group of patients who required intestinal resection, there was a significantly higher proportion of female patients (52% vs 35%; P = .001), significantly higher age (mean age: 78.2 ± 11.2 vs 72.2 ± 15.4 years; P < .001), significantly higher rate of comorbidities based on the ASA classification (P = .008) and Charlson Comorbidity Scale (CCI) score (P = .015), and a significantly higher rate of chronic kidney disease (P = .019) (Table 1).

Patient characteristics of the study population.

| Variables | Total (n = 652) | Bowel resection (n = 100) | No bowel resection (n = 552) | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean (SD) | 73.1 (14.9) | 78.2 (11.2) | 72.2 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Male | 407 (62) | 48 (48) | 359 (65) | |

| Female | 245 (38) | 52 (52) | 193 (35) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 25.5 (4.2) | 25.2 (4) | 25.6 (4.3) | 0.498 |

| ASA score | 0.008 | |||

| I/II, n (%) | 356 (55) | 43 (43) | 316 (57) | |

| III/IV, n (%) | 293 (45) | 57 (57) | 236 (43) | |

| Charlson score, mean (SD) | 4.8 (2.7) | 5.4 (2.2) | 4.7 (2.8) | 0.015 |

| Previous abdominal surgery, n (%) | 301 (46) | 37 (37) | 264 (48) | 0.046 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | 498 (76) | 83 (83) | 415 (75) | 0.090 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 349 (54) | 61 (61) | 288 (52) | 0.103 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 123 (19) | 17 (17) | 106 (19) | 0.604 |

| Chronic nephropathy, n (%) | 68(10) | 17 (17) | 51 (9) | 0.019 |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 25 (4) | 3 (3) | 22 (4) | 0.784 |

| Neurocognitive disorders, n (%) | 97 (15) | 17 (17) | 80 (15) | 0.517 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 93 (15) | 5 (5) | 88 (16) | 0.004 |

| Comorbidities (more than one), n (%) | 329 (51) | 52 (52) | 277 (50) | 0.738 |

| Hernia type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Inguinal lateral | 286 (44) | 30 (30) | 256 (47) | |

| Inguinal medial | 133 (20) | 13 (13) | 120 (22) | |

| Femoral | 204 (31) | 55 (55) | 149 (27) | |

| Other | 28 (5) | 2 (2) | 26 (4) | |

| Recurrent hernia, n (%) | 136 (21) | 21 (21) | 115 (21) | 0.970 |

| Preoperative bowel obstruction, n (%) | 258 (40) | 84 (84) | 174 (32) | <0.001 |

| Duration of incarceration ≥24 h, n (%) | 407 (63) | 74 (76) | 333 (61) | 0.003 |

| Required midline laparotomy, n (%) | 31 (5) | 14 (14) | 17 (3) | <0.001 |

| Type of repair, n (%) | 0.065 | |||

| Mesh repair | 632 (97) | 94 (94) | 538 (98) | |

| Tissue repair | 20 (3) | 6 (6) | 14 (3) | |

| Type of procedure, n (%) | 0.316 | |||

| Anterior | 330 (51) | 46 (46) | 284 (51) | |

| Preperitoneal | 332 (49) | 54 (54) | 268 (49) | |

| Intraoperative complications, n (%) | 25 (4) | 9 (9) | 16 (3) | 0.003 |

| Complications, n (%) | 297 (46) | 80 (80) | 217 (39) | <0.001 |

| Clavien Dindo classification of postoperative complications, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| None | 355 (54) | 20 (20) | 335 (61) | |

| I/II | 240 (37) | 58 (58) | 182 (33) | |

| ≥III | 57 (9) | 22 (22) | 35 (6) | |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 27 (4) | 6 (6) | 21 (4) | 0.311 |

| SSO, n (%) | 163 (25) | 37 (37) | 126 (23) | 0.003 |

| Length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 6.6 (11.1) | 14.1 (21.9) | 4.7 (2.8) | <0.001 |

Regarding the characteristics of the hernias, significant differences were observed between the groups in the percentage of femoral hernias (55% vs 27%; P ≤ .001), duration of incarceration ≥24 h (P = .003), preoperative bowel obstruction (84% vs 32%; P < .001), and associated midline laparotomy (14% vs 3%; P < .001). These variables were more frequent in the group of patients who required intestinal resection. There were no significant differences in the type of repair or surgical approach (Table 1). Among the patients who required an associated midline laparotomy, 8.2% (n = 27) of those who underwent an anterior approach needed this procedure, compared to 1.2% (n = 4) of patients who underwent a posterior preperitoneal approach (P < .001).

Out of the 100 patients who required intestinal resection, 13 patients did not present with a femoral hernia or preoperative intestinal obstruction. In this subgroup, 4 patients had inguinoscrotal hernias, 6 had recurrent hernias, and 4 had a duration of incarceration ≥24 h.

Postoperative resultsThe overall postoperative complication rate was 46% (n = 297/652). Patients who required intestinal resection had a significantly higher rate of postoperative complications (80% vs 39%; P < .001), SSO (37% vs 23%; P = .003), and CD ≥III complications (22% vs 6%; P < .001) and a longer hospital stay (mean: 14.1 ± 21.9 vs 4.7 ± 2.8; P < .001) than patients who did not need intestinal resection (Table 1). The overall mortality rate was 7.1% (n = 46), with a significantly higher rate in the intestinal resection group compared to the non-resection group (19% vs 5%; P < .001). The mean follow-up was 17 months (SD: 27.3).

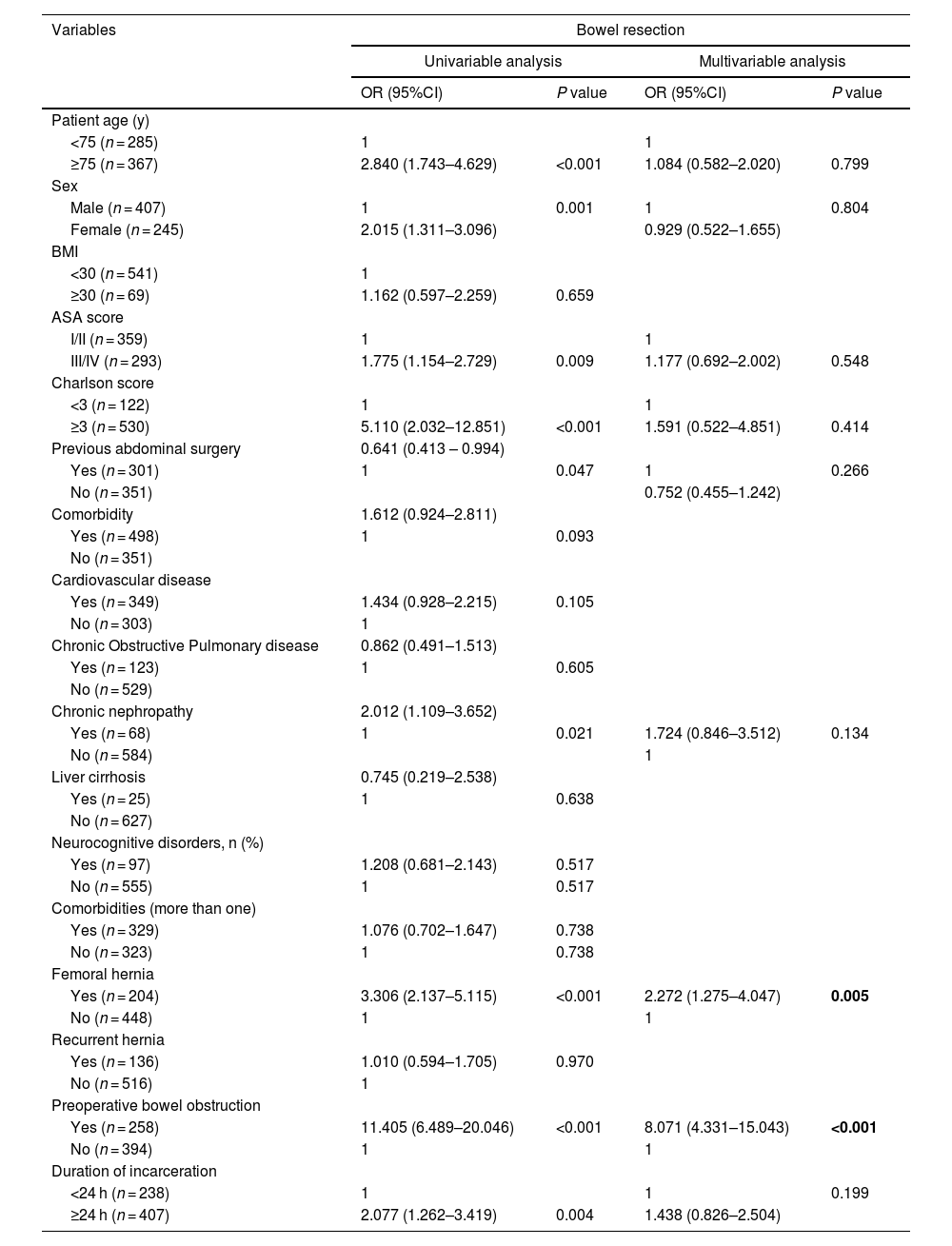

Risk factors for intestinal resectionThe results of the univariate and multivariate analyses of intestinal resection are shown in Table 2. According to the multivariate analysis, femoral hernia (OR, 2.272; 95%CI, 1.275–4.047; P = .005) and preoperative intestinal obstruction (OR, 8.071; 95%CI, 4.331–15.043; P < .001) were found to be independent risk factors for intestinal resection in urgent inguinal hernia surgery for acute incarceration.

Univariate and multivariable analysis of independent risk factors for bowel resection.

| Variables | Bowel resection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Patient age (y) | ||||

| <75 (n = 285) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥75 (n = 367) | 2.840 (1.743–4.629) | <0.001 | 1.084 (0.582–2.020) | 0.799 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (n = 407) | 1 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.804 |

| Female (n = 245) | 2.015 (1.311–3.096) | 0.929 (0.522–1.655) | ||

| BMI | ||||

| <30 (n = 541) | 1 | |||

| ≥30 (n = 69) | 1.162 (0.597–2.259) | 0.659 | ||

| ASA score | ||||

| I/II (n = 359) | 1 | 1 | ||

| III/IV (n = 293) | 1.775 (1.154–2.729) | 0.009 | 1.177 (0.692–2.002) | 0.548 |

| Charlson score | ||||

| <3 (n = 122) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥3 (n = 530) | 5.110 (2.032–12.851) | <0.001 | 1.591 (0.522–4.851) | 0.414 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 0.641 (0.413 – 0.994) | |||

| Yes (n = 301) | 1 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.266 |

| No (n = 351) | 0.752 (0.455–1.242) | |||

| Comorbidity | 1.612 (0.924–2.811) | |||

| Yes (n = 498) | 1 | 0.093 | ||

| No (n = 351) | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | ||||

| Yes (n = 349) | 1.434 (0.928–2.215) | 0.105 | ||

| No (n = 303) | 1 | |||

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease | 0.862 (0.491–1.513) | |||

| Yes (n = 123) | 1 | 0.605 | ||

| No (n = 529) | ||||

| Chronic nephropathy | 2.012 (1.109–3.652) | |||

| Yes (n = 68) | 1 | 0.021 | 1.724 (0.846–3.512) | 0.134 |

| No (n = 584) | 1 | |||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.745 (0.219–2.538) | |||

| Yes (n = 25) | 1 | 0.638 | ||

| No (n = 627) | ||||

| Neurocognitive disorders, n (%) | ||||

| Yes (n = 97) | 1.208 (0.681–2.143) | 0.517 | ||

| No (n = 555) | 1 | 0.517 | ||

| Comorbidities (more than one) | ||||

| Yes (n = 329) | 1.076 (0.702–1.647) | 0.738 | ||

| No (n = 323) | 1 | 0.738 | ||

| Femoral hernia | ||||

| Yes (n = 204) | 3.306 (2.137–5.115) | <0.001 | 2.272 (1.275–4.047) | 0.005 |

| No (n = 448) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Recurrent hernia | ||||

| Yes (n = 136) | 1.010 (0.594–1.705) | 0.970 | ||

| No (n = 516) | 1 | |||

| Preoperative bowel obstruction | ||||

| Yes (n = 258) | 11.405 (6.489–20.046) | <0.001 | 8.071 (4.331–15.043) | <0.001 |

| No (n = 394) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Duration of incarceration | ||||

| <24 h (n = 238) | 1 | 1 | 0.199 | |

| ≥24 h (n = 407) | 2.077 (1.262–3.419) | 0.004 | 1.438 (0.826–2.504) | |

In the present study, femoral hernias and preoperative intestinal obstruction were found to be independent risk factors for intestinal resection in patients who underwent emergency surgery for acute irreducible inguinal hernia. Intestinal resection was more frequent in female patients, elderly patients, patients with high comorbidity, patients with femoral hernia, and patients with a duration of acute incarceration ≥24 h. Patients who required intestinal resection more commonly required associated midline laparotomy and had greater postoperative morbidity and a longer hospital stay.

The management of acute irreducible inguinal hernia remains a controversial, evolving topic.6,7 In the recent update of the international guidelines for the management of inguinal hernia, 2 important factors stand out in the treatment of emergency inguinal hernia: the implementation of manual reduction to defer an urgent intervention to an elective intervention, and the role of minimally invasive surgery.7 In both instances, decision-making is influenced by the presence of intestinal ischemia in the irreducible contents, and it is therefore very important to study the risk factors associated with intestinal resection in this context. In our study, femoral hernia and preoperative intestinal obstruction were risk factors for intestinal resection according to multivariate analysis. Several authors have reported similar results.1,3,4 In a meta-analysis of 7 studies with a total of 762 patients and an intestinal resection rate of 21% (160/762), 8 risk factors were significantly associated with intestinal resection in patients who had undergone surgery for incarcerated inguinal hernia. These included advanced age, female sex, femoral hernia, duration of incarceration and intestinal obstruction, and inflammatory indicators. The authors concluded that the combination of these factors should be considered for early diagnosis and early surgical repair to improve the outcomes of these patients.5 Furthermore, a predictive model for intestinal resection in incarcerated inguinal hernias that includes these factors has recently been proposed.12 Out of the total series, a small number of patients with intestinal resection did not present femoral hernia or preoperative intestinal obstruction. In this subgroup, other factors that could have conditioned intestinal resection were observed, such as inguinoscrotal hernias, recurrent hernias, and prolonged duration of incarceration. These cases highlight the importance of considering multiple risk factors when evaluating patients with acute irreducible hernia, as the need for intestinal resection may be due to a combination of complex clinical conditions.

Furthermore, in the update of the recently published international guidelines for the management of inguinal hernia, manual reduction of all acute irreducible hernias without suspicion of intestinal ischemia is recommended, and a management algorithm is proposed where suspicion of intestinal ischemia is based on skin changes, duration of symptoms greater than 24 h, presence of peritonitis, and elevated serum D-dimer and phosphokinase levels.7 This recommendation is made with a very low level of evidence and was considered weak.7 Given the results of our study (which are in line with reports by other authors5), it could be risky to manage all acute irreducible inguinal hernias with no signs of intestinal ischemia by manual reduction without first considering certain factors, such as patient sex, hernia type, and presence of symptoms, such as preoperative intestinal obstruction. Therefore, we believe that the proposed algorithm should be improved by incorporating other risk factors for intestinal resection widely studied in the literature, and we consider this strategy as a secondary alternative to emergency surgery while waiting to provide more solid evidence in favor of manual reduction.

The surgical approach for treating acute irreducible hernias is another aspect that continues to be debated, and the need for intestinal resection seems to be fundamental in the decision-making process. Since there is currently insufficient evidence to support an optimal surgical approach, an individualized approach has been recommended.6,7 In our series, a higher percentage of patients who underwent intestinal resection had been treated with an open posterior preperitoneal approach, although the difference was not significant. This demonstrates that there is no standard repair method in this context, so the approach was at the discretion of the surgeon based on their experience and patient characteristics. In recent years, several studies have focused on the usefulness of the laparoscopic approach in emergency inguinal hernia repair.13,14 Some authors conclude that this approach is feasible and has acceptable results, although they admit that additional studies are needed to evaluate its effectiveness.15 In this context, the WSES guidelines for the emergency repair of abdominal wall hernias recommend considering the laparoscopic approach for incarcerated inguinal hernias in the absence of strangulation or suspected need for intestinal resection, where the open preperitoneal approach is preferable.16 Therefore, the need for intestinal resection should be considered in the decision-making process for the surgical approach of patients with emergency inguinal hernia together with other variables, such as patient condition, the surgeon’s experience, and the surgical conditions of the medical institution.12

Patients in the intestinal resection group more frequently required midline laparotomy, which has been identified as a risk factor for postoperative complications in emergency inguinal hernia repair.17 Furthermore, our findings show that the need for an associated midline laparotomy was significantly higher in patients who had undergone an anterior approach compared to those treated with a posterior approach. For this reason, some authors have suggested that the open posterior preperitoneal approach offers advantages in this context, as it facilitates exploration of the abdominal cavity and intestinal resection, when necessary, thereby avoiding the need for midline laparotomy.18,19

Performing intestinal resection in an acute irreducible hernia directly affects the results.5 The length of hospital stay was significantly longer in the intestinal resection group, which is consistent with the findings of other studies in the literature.4 Patients who had undergone intestinal resection had a higher rate of complications, and these complications were also more severe, as reported by other studies.4,5 It is therefore crucial to identify high-risk factors for bowel resection as early as possible to perform surgery.

Our findings have significant practical implications for improving the management of patients with acute irreducible hernia. Identification of femoral hernias and preoperative bowel obstruction as independent risk factors for bowel resection allows surgeons to quickly recognize high-risk patients, facilitating early and appropriate intervention. This not only optimizes preoperative planning and efficient use of resources in emergency settings but also contributes to the development of more precise management protocols and algorithms. Furthermore, by intervening in a timely manner in patients with these risk factors, it is possible to reduce the rate of postoperative complications and improve clinical outcomes, highlighting the need to consider these findings in future updates of clinical guidelines.

We propose an updated algorithm for the management of acute irreducible inguinal hernias, building upon and improving the framework outlined in recent clinical guidelines.7 Our algorithm integrates the independent risk factors identified in our study —preoperative intestinal obstruction, femoral hernia, and female sex— as key indicators for prioritizing emergency surgery. It emphasizes the open posterior approach as the preferred surgical technique in emergency settings, particularly in cases where the need for bowel resection is suspected. This approach facilitates abdominal cavity exploration, enables intestinal resection when necessary, and reduces the need for midline laparotomy, aligning with our findings and supporting evidence from the literature18,19 (Fig. 1).

The algorithm also incorporates modern surgical tools, such as diagnostic laparoscopy and indocyanine green fluorescence (IGF) imaging, to enhance intraoperative assessment of bowel viability. Although there is currently no specific evidence supporting the use of IGF in emergency groin hernia management, its proven effectiveness in evaluating intestinal perfusion in other surgical contexts highlights its potential in this setting.20,21 By providing real-time feedback on bowel viability, IGF may reduce unnecessary resections and improve surgical decision-making. By addressing gaps in current guidelines, such as the limited consideration of specific risk factors and variability in surgical approaches, this algorithm offers a more tailored and evidence-based strategy to optimize patient outcomes in emergency settings.

Our study has limitations. Due to its retrospective nature, possible selection biases could not be controlled, nor could some important variables be collected, such as inflammatory markers. When evaluating patients who had undergone emergency surgery, patients who presented with an acute irreducible hernia that was reduced and who were then discharged with a plan for a later operation were not compared. Additionally, it was not possible to collect data for imaging tests (eg preoperative CT scans) due to the variability in their availability and use in both hospitals. Furthermore, the percentage of cases in which an attempt was made to preserve the bowel loop but resection was ultimately required could not be determined, as this information was not consistently documented in the medical records.

In conclusion, this study revealed that femoral hernia and intestinal obstruction are independent predictors of intestinal resection in patients with acute irreducible hernia. Therefore, the presence of these factors must be considered when determining the most appropriate management strategy.

CRediT authorship contribution statementV. Rodrigues-Gonçalves made substantial contributions to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data and drafting the article.

M. Verdaguer-Tremolosa made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data.

A. Bravo-Salva made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data.

P. Martínez-López made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data.

J. A. Pereira-Rodríguez made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data.

M. López-Cano made substantial contributions drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and for the final approval of the version to be submitted.

Ethical adherenceThe ethics committees of both hospitals approved the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participateNo signed informed consent was needed for this study.

Source of supportThis project did not receive external funding from any source other than the authors’ institutions.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare or financial ties to disclose. Manuel López-Cano has received honoraria and travel support from BD-Bard, Medtronic and Gore for consultancy, lectures and participation in review activities