The methodology used for recording, evaluating and reporting postoperative complications (PC) is unknown.

The aim of the present study was to determine how PC are recorded, evaluated, and reported in General and Digestive Surgery Services (GDSS) in Spain, and to assess their stance on morbidity audits.

MethodsUsing a cross-sectional study design, an anonymous survey of 50 questions was sent to all the heads of GDSS at hospitals in Spain.

ResultsThe survey was answered by 67 out of 222 services (30.2%). These services have a reference population (RP) of 15 715 174 inhabitants, representing 33% of the Spanish population.

Only 15 services reported being requested to supply data on morbidity by their hospital administrators. Eighteen GDSS, with a RP of 3 241 000 (20.6%) did not record PC. Among these, 7 were accredited for some area of training. Thirty-six GDSS (RP 8 753 174 (55.7%) did not provide details on all PC in patients’ discharge reports. Twenty-four (37%) of the 65 GDSS that had started using a new surgical procedure/technique had not recorded PC in any way. Sixty-five GDSS were not concerned by the prospect of their results being audited, and 65 thought that a more comprehensive knowledge of PC would help them improve their results. Out of the 37 GDSS that reported publishing their results, 27 had consulted only one source of information: medical progress records in 11 cases, and discharge reports in 9.

ConclusionsThis study reflects serious deficiencies in the recording, evaluation and reporting of PC by GDSS in Spain.

Se desconoce la metodología para objetivar las complicaciones postoperatorias (CPs). El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar cómo se registran, evalúan y notifican los CPs en los Servicios de Cirugía General y Digestiva (GDSS) en España, y analizar su actitud ante una auditoría de morbilidad.

MétodosEstudio transversal en el que se envió una encuesta anónima de 50 preguntas a todos los responsables de los GDSS de los hospitales españoles.

ResultadosRespondieron 67 de 222 servicios (30,2%) con una población de referencia (RP) de habitantes, que representa el 33% de la población española.

Sólo se solicitó a 15 servicios datos sobre morbilidad por parte de las direcciones hospitalarias. Dieciocho GDSS, con una RP de 3.241.000 (20,6%) no registraron CPs. De estos, siete estaban acreditados para alguna área de capacitación. Treinta y seis GDSS (RP 8,753,174 (55,7%) no detallaron todas las CPs en los informes de alta.

Veinticuatro (37%) de los 65 GDSS que habían iniciado un nuevo procedimiento/técnica quirúrgica no habían registrado CPs de ninguna manera. Sesenta y cinco GDSS no estaban preocupados si sus resultados fueran auditados y 65 pensaban que el conocimiento real de las CPs les ayudaría a mejorar sus resultados. De los 37 GDSS que informaron haber publicado sus resultados, 27 habían consultado una fuente de información: en once casos registros de evolución médica y en nueve informes de alta.

ConclusionesEste estudio refleja un grave déficit en el registro, evaluación y comunicación de las CPs por parte de los GDSS en España.

Postoperative complications (PC) are the most important short-term quality outcomes of surgical interventions.

Currently, the methodology used to record, evaluate and report PC is very deficient. There are no surgical services anywhere in the world that audit the morbidity associated with every single procedure that they perform. However, the advantages of audits are obvious, and the disadvantages of failing to carry them out are serious.1

Even so, little is known about PC rates in General and Digestive Surgery Services (GDSS) around the world.

Today, the most widely used system for classifying PC is the Clavien-Dindo classification (CDC),2 with more than 22 648 bibliographic citations to date.3 The drawback of the CDC is the fact that when patients have more than one complication, only the most serious one is recorded. This situation led to the creation of the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI), which analyzes all PC classified by the CDC.4 Both systems have been validated from the clinical and economic perspectives for all procedures carried out by general surgery services 90 days after surgery.5,6

The overall aim of this study was to assess how Spanish GDSS manage different factors when recording PC. Thus, the specific aims were to determine the following: 1) the information that services record regarding PC; 2) the data sources used, and the people responsible for recording and possibly publishing PC; 3) the correlation between different facets of morbidity and the organizational and demographic characteristics of the GDSS and hospitals; 4) respondents’ views regarding the auditing of morbidity data and transparency issues.

MethodsThe data in this manuscript are reported in accordance with the STROBE Statement on cross-sectional studies7 as well as the published clarifications.8

Study designA cross-sectional study was carried out using a 50-item survey that was completed anonymously (https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/4zjfpxv57h/1).

ParticipantsThe survey was sent by email to all the heads of the GDSS of the hospitals registered in the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC) database. The department heads were asked to either fill out the survey themselves or delegate the task to a staff member. Thus, only one survey was completed for each of the participating GDSS.

SettingsThe questions in the survey were drafted by the first author and were discussed by the members of the Quality, Safety and Management Division of the AEC in April 2021, until a consensus was reached on the wording. The e-mail was sent out on October 6, 2021, followed by reminders on October 22, November 15, and December 1. Access to the survey closed on December 12, 2021.

In the surveys, all questions had to be answered prior to submission. However, there was no obligation to answer the survey, and only a percentage of the total number of respondents did so.

VariablesThe unit of analysis was the hospital, and information was recorded for its size (estimated according to the number of beds), reference population, and hospital level. As for the GDSS, variables indicating size and importance were recorded, including numbers of senior staff and the presence of resident interns and medical students.

A series of quality variables were also included, namely whether the service was accredited in a particular area of training, whether it was a reference center for a specific surgical procedure, and whether a new surgical procedure/technique had been introduced in the past 10 years. Respondents were also asked if they organized sessions on morbidity and mortality.

Information on PC was collected in order to establish the following: whether they were reflected in patients’ medical histories or discharge reports; the length of follow-up; the person in charge of recording morbidity and mortality data; and the classification system used.

Respondents were asked whether their hospital administrators expected them to provide morbidity data. They were also asked about the sources of the clinical data used to investigate PC.

Finally, information was collected on whether respondents were concerned about the possibility of PC being audited, which institution they believed should perform the audit, and whether the results should be made public. The data sources used were the surveys completed by the GDSS, which were made available to the researchers in an Excel table.

BiasBefore the start of the study, steps were taken to avoid certain possible sources of bias. The first was to ensure that the survey be completed anonymously, thereby ensuring that respondents gave honest, objective answers. In addition, to avoid multiple responses from the same surgery department and to maintain anonymity, the survey was sent to the heads of the department with the instruction that only one person should complete it.

Data from the AEC were used in order to access as many general and digestive services as possible. The researchers did not have access to the surgeons or the hospitals to which the questionnaire was sent.

Statistical methodsThe quantitative variables were described as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Non-parametric tests, such as the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal Wallis H test, were used as appropriate to compare these variables between groups. Normality was tested with the Shapiro Wilks test.

The qualitative variables were described as frequencies and percentages. To compare these variables between groups, either the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used.

The statistical study used the program STATA/SE v16.0. All comparisons are 2-tailed, and P-values below 5% were considered significant. P-values were reported to 3 decimal places and in all rows.

ResultsParticipantsThe survey was sent to the GDSS heads at 222 hospitals, and 67 (30.2%) completed the survey. In 62 cases, the respondent was the department head, and in 5 cases another staff member of the department responded.

A total of 3618 Excel cells with plain or free text were analyzed.

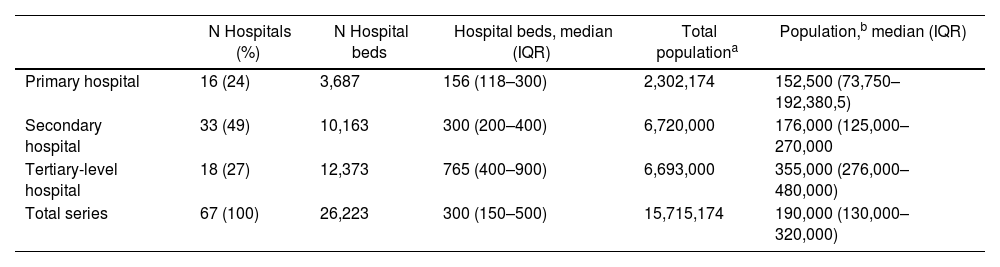

The reference population (RP) was 15 715 174 inhabitants, accounting for 33% of Spain’s 47 331 302 inhabitants (July 1, 2021).9 The population per GDSS ranged from 40 000 to 800 000 inhabitants (median 190 000, IQR: 13 000–320 000) (Table 1).

Characteristics of the hospitals/surgery departments participating in the survey: Beds and reference population.

| N Hospitals (%) | N Hospital beds | Hospital beds, median (IQR) | Total populationa | Population,b median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary hospital | 16 (24) | 3,687 | 156 (118–300) | 2,302,174 | 152,500 (73,750–192,380,5) |

| Secondary hospital | 33 (49) | 10,163 | 300 (200–400) | 6,720,000 | 176,000 (125,000–270,000 |

| Tertiary-level hospital | 18 (27) | 12,373 | 765 (400–900) | 6,693,000 | 355,000 (276,000–480,000) |

| Total series | 67 (100) | 26,223 | 300 (150–500) | 15,715,174 | 190,000 (130,000–320,000) |

N Number; SD Standard Deviation; IQR Interquartile range.

The number of beds in the participating hospitals ranged from 33 to 1200. The median number of surgeons at a GDSS was 14 (IQR 8–24). Other hospital characteristics are shown in Table 1.

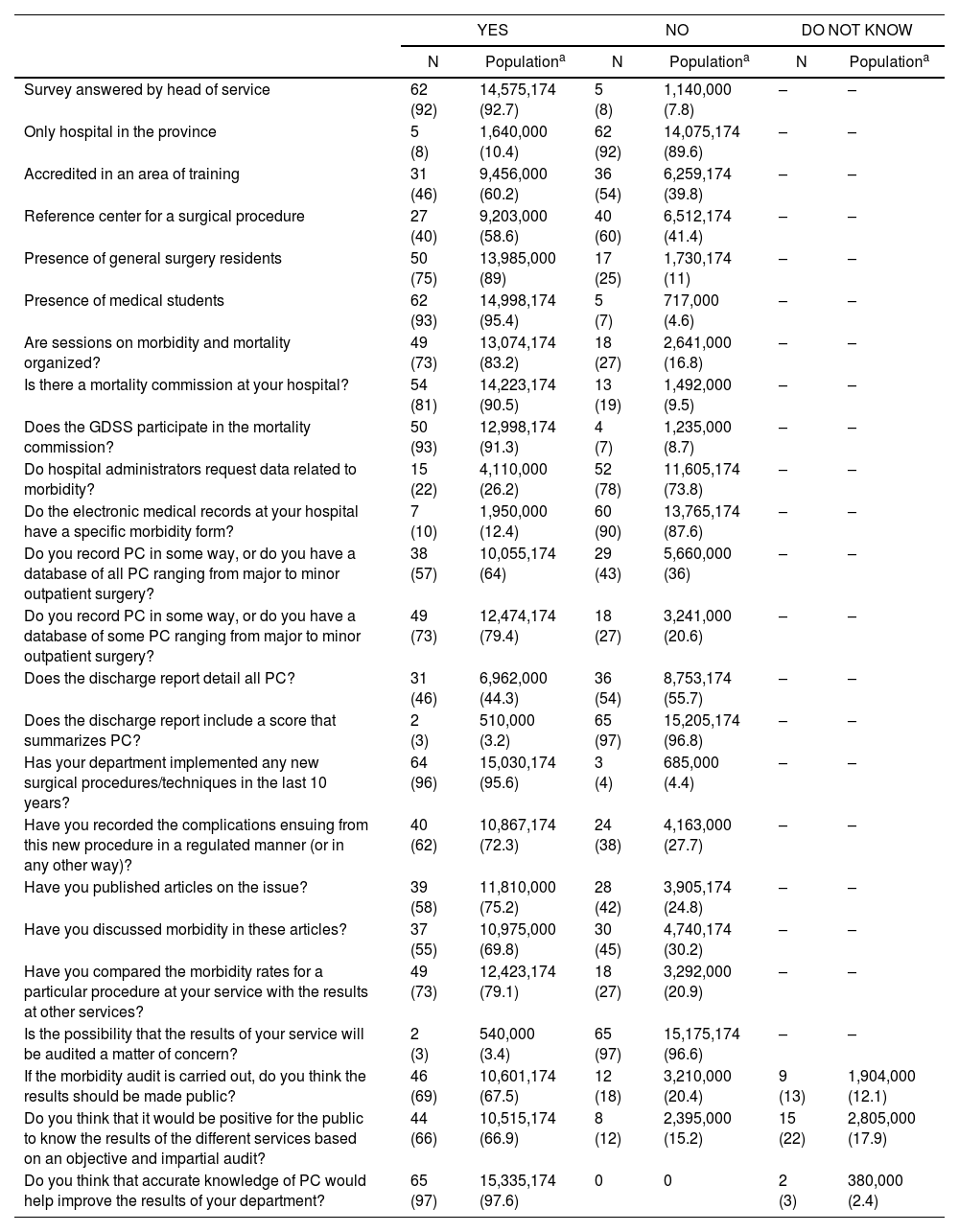

At 50 hospitals (RP 13 985 000; 89%), the GDSS included general surgery residents. At 62 hospitals (RP 14 998 174; 95.4%), medical students were trained (Table 2).

Answers to the main questions in the survey and number of hospitals and population represented.

| YES | NO | DO NOT KNOW | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Populationa | N | Populationa | N | Populationa | |

| Survey answered by head of service | 62 (92) | 14,575,174 (92.7) | 5 (8) | 1,140,000 (7.8) | – | – |

| Only hospital in the province | 5 (8) | 1,640,000 (10.4) | 62 (92) | 14,075,174 (89.6) | – | – |

| Accredited in an area of training | 31 (46) | 9,456,000 (60.2) | 36 (54) | 6,259,174 (39.8) | – | – |

| Reference center for a surgical procedure | 27 (40) | 9,203,000 (58.6) | 40 (60) | 6,512,174 (41.4) | – | – |

| Presence of general surgery residents | 50 (75) | 13,985,000 (89) | 17 (25) | 1,730,174 (11) | – | – |

| Presence of medical students | 62 (93) | 14,998,174 (95.4) | 5 (7) | 717,000 (4.6) | – | – |

| Are sessions on morbidity and mortality organized? | 49 (73) | 13,074,174 (83.2) | 18 (27) | 2,641,000 (16.8) | – | – |

| Is there a mortality commission at your hospital? | 54 (81) | 14,223,174 (90.5) | 13 (19) | 1,492,000 (9.5) | – | – |

| Does the GDSS participate in the mortality commission? | 50 (93) | 12,998,174 (91.3) | 4 (7) | 1,235,000 (8.7) | – | – |

| Do hospital administrators request data related to morbidity? | 15 (22) | 4,110,000 (26.2) | 52 (78) | 11,605,174 (73.8) | – | – |

| Do the electronic medical records at your hospital have a specific morbidity form? | 7 (10) | 1,950,000 (12.4) | 60 (90) | 13,765,174 (87.6) | – | – |

| Do you record PC in some way, or do you have a database of all PC ranging from major to minor outpatient surgery? | 38 (57) | 10,055,174 (64) | 29 (43) | 5,660,000 (36) | – | – |

| Do you record PC in some way, or do you have a database of some PC ranging from major to minor outpatient surgery? | 49 (73) | 12,474,174 (79.4) | 18 (27) | 3,241,000 (20.6) | – | – |

| Does the discharge report detail all PC? | 31 (46) | 6,962,000 (44.3) | 36 (54) | 8,753,174 (55.7) | – | – |

| Does the discharge report include a score that summarizes PC? | 2 (3) | 510,000 (3.2) | 65 (97) | 15,205,174 (96.8) | – | – |

| Has your department implemented any new surgical procedures/techniques in the last 10 years? | 64 (96) | 15,030,174 (95.6) | 3 (4) | 685,000 (4.4) | – | – |

| Have you recorded the complications ensuing from this new procedure in a regulated manner (or in any other way)? | 40 (62) | 10,867,174 (72.3) | 24 (38) | 4,163,000 (27.7) | – | – |

| Have you published articles on the issue? | 39 (58) | 11,810,000 (75.2) | 28 (42) | 3,905,174 (24.8) | – | – |

| Have you discussed morbidity in these articles? | 37 (55) | 10,975,000 (69.8) | 30 (45) | 4,740,174 (30.2) | – | – |

| Have you compared the morbidity rates for a particular procedure at your service with the results at other services? | 49 (73) | 12,423,174 (79.1) | 18 (27) | 3,292,000 (20.9) | – | – |

| Is the possibility that the results of your service will be audited a matter of concern? | 2 (3) | 540,000 (3.4) | 65 (97) | 15,175,174 (96.6) | – | – |

| If the morbidity audit is carried out, do you think the results should be made public? | 46 (69) | 10,601,174 (67.5) | 12 (18) | 3,210,000 (20.4) | 9 (13) | 1,904,000 (12.1) |

| Do you think that it would be positive for the public to know the results of the different services based on an objective and impartial audit? | 44 (66) | 10,515,174 (66.9) | 8 (12) | 2,395,000 (15.2) | 15 (22) | 2,805,000 (17.9) |

| Do you think that accurate knowledge of PC would help improve the results of your department? | 65 (97) | 15,335,174 (97.6) | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) | 380,000 (2.4) |

N, Number of surgical services.

Table 2 shows the responses to the main survey questions, as well as the number of GDSS and the population represented. The main findings and population figures were as follows: 1) 49 services (RP 13 074 174; 83.2%) organized sessions on morbidity and mortality; 2) 15 services (RP 4 110 000; 26.2%) were required by their hospital administration to provide data on morbidity; 3) 18 GDSS (RP 3 241 000; 20.6%) did not record data about PC. Among these, 7 (RP 1 871 000: 19.8%) were accredited in some area of training. Overall morbidity was recorded at 3 services; 4) 36 services (8 753 174 inhabitants; 55.7%) did not list all PC in patients’ discharge reports; 5) Among the 64 services that reported having started a new surgical procedure/technique, 24 (4 163 000 inhabitants; 27.7%) kept no records about PC; 6) 65 services (15 175 174 inhabitants; 96.6%) reported not being concerned by the idea that the results might be audited; 7) If an audit of morbidity data was carried out, 46 services (10 601 174 inhabitants; 67.5%) agreed that the results should be made public; 8) 44 services (10 515 174 inhabitants; 66.9%) believed that it would be positive for society to be informed of the results obtained by different GDSS via an objective and impartial audit; 9) 65 services (15 335 174 inhabitants; 97.6%) responded that an accurate assessment of PC would help their unit improve their results.

Other data: 1) Sessions about morbidity and mortality were held monthly in 49% of the surgical departments, and every 3 months in 16%. They were presented by residents in 41%, by senior staff in 29%, or by either group in 29%; 2) If morbidity data were to be audited, 38 would prefer the audit to be carried out by a centralized national public entity; 18 would choose the regional Department of Health, 7 a private entity, 3 the department itself, and one the hospital administration team; 3) 16 of the respondents believed that the results of the audit should be reported overall for all surgeons; 8 believed that they should be presented individually, by surgeon; and 43 favored both overall and individual assessments.

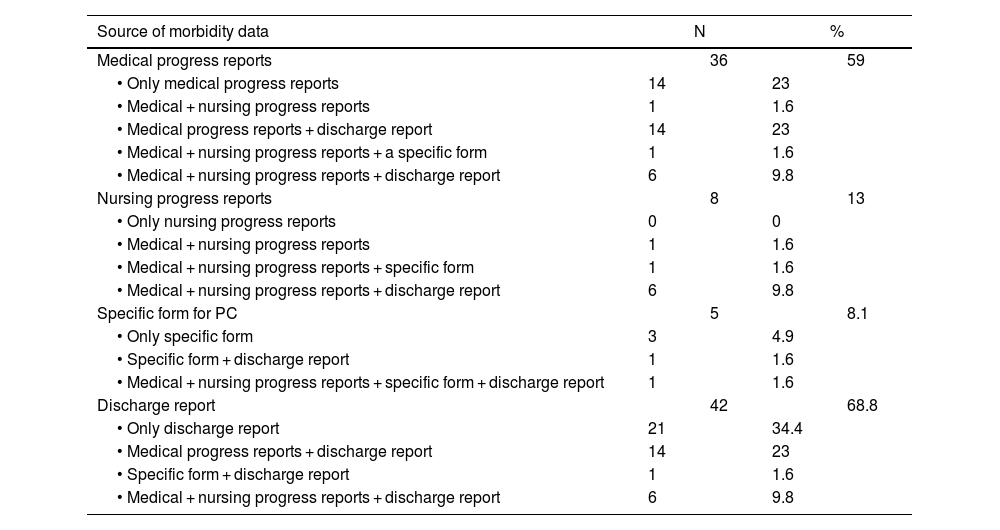

Data sources used to assess postoperative complicationsWhen evaluating PC, 38 out of the 61 GDSS used a single data source: the discharge report in 21 cases, medical progress reports in 14 cases, and a specific form for PC in 2 (Table 3). Patients with PC were followed up for 30 days by 46 study groups, while 7 groups followed up patients for 90 days.

Data sources used by the 61 participating services that had collected data to assess postoperative complications (multiple-choice questions).

| Source of morbidity data | N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical progress reports | 36 | 59 | ||

| • Only medical progress reports | 14 | 23 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| • Medical progress reports + discharge report | 14 | 23 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports + a specific form | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports + discharge report | 6 | 9.8 | ||

| Nursing progress reports | 8 | 13 | ||

| • Only nursing progress reports | 0 | 0 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports + specific form | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports + discharge report | 6 | 9.8 | ||

| Specific form for PC | 5 | 8.1 | ||

| • Only specific form | 3 | 4.9 | ||

| • Specific form + discharge report | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports + specific form + discharge report | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| Discharge report | 42 | 68.8 | ||

| • Only discharge report | 21 | 34.4 | ||

| • Medical progress reports + discharge report | 14 | 23 | ||

| • Specific form + discharge report | 1 | 1.6 | ||

| • Medical + nursing progress reports + discharge report | 6 | 9.8 | ||

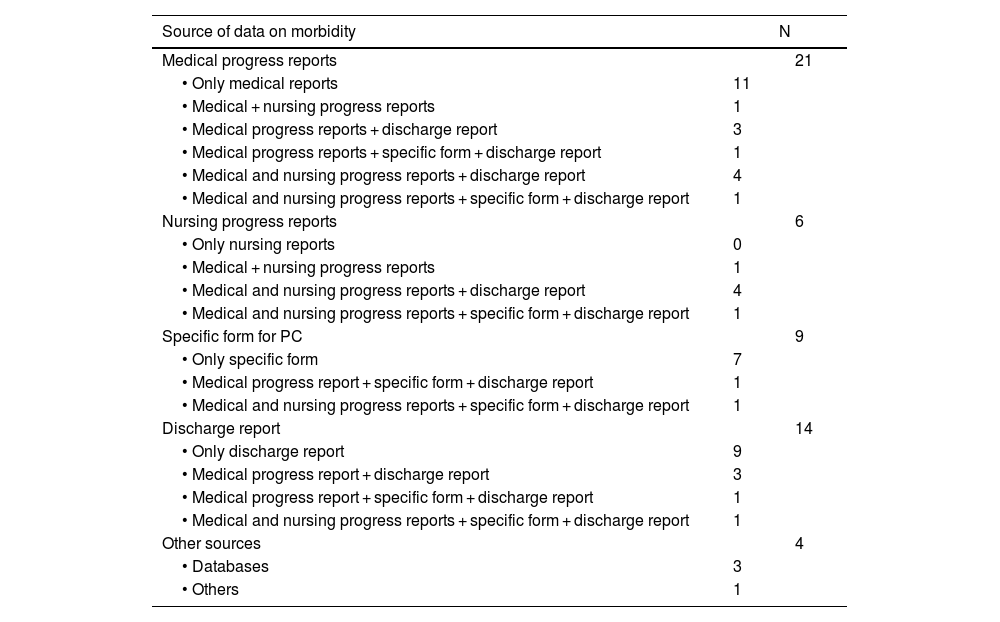

Thirty-seven departments reported morbidity data in a scientific publication (Table 4). Among these, 27 had consulted only one source of information: medical progress reports (11), discharge reports (9), or a specific form for PC (7).

Data sources used by the 37 surgery services that have published a scientific study to determine postoperative complications (multiple answers are possible).

| Source of data on morbidity | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Medical progress reports | 21 | |

| • Only medical reports | 11 | |

| • Medical + nursing progress reports | 1 | |

| • Medical progress reports + discharge report | 3 | |

| • Medical progress reports + specific form + discharge report | 1 | |

| • Medical and nursing progress reports + discharge report | 4 | |

| • Medical and nursing progress reports + specific form + discharge report | 1 | |

| Nursing progress reports | 6 | |

| • Only nursing reports | 0 | |

| • Medical + nursing progress reports | 1 | |

| • Medical and nursing progress reports + discharge report | 4 | |

| • Medical and nursing progress reports + specific form + discharge report | 1 | |

| Specific form for PC | 9 | |

| • Only specific form | 7 | |

| • Medical progress report + specific form + discharge report | 1 | |

| • Medical and nursing progress reports + specific form + discharge report | 1 | |

| Discharge report | 14 | |

| • Only discharge report | 9 | |

| • Medical progress report + discharge report | 3 | |

| • Medical progress report + specific form + discharge report | 1 | |

| • Medical and nursing progress reports + specific form + discharge report | 1 | |

| Other sources | 4 | |

| • Databases | 3 | |

| • Others | 1 | |

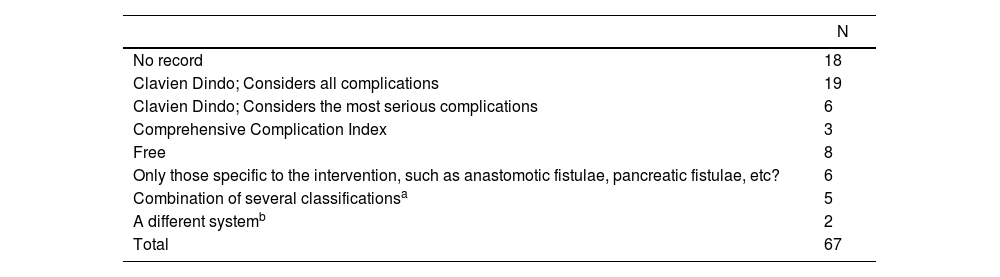

Regarding the PC classification system used by the 49 services that recorded them, 25 used only the CDC (6 considered only the most serious PC), and 2 used it in association with the CCI. Three used the CCI alone, and 6 recorded only the PC specific to a particular procedure (Table 5).

Do you record PC in some way, or do you have a PC database ranging from major to minor outpatient surgery? Please state which classification system you use for PC.

| N | |

|---|---|

| No record | 18 |

| Clavien Dindo; Considers all complications | 19 |

| Clavien Dindo; Considers the most serious complications | 6 |

| Comprehensive Complication Index | 3 |

| Free | 8 |

| Only those specific to the intervention, such as anastomotic fistulae, pancreatic fistulae, etc? | 6 |

| Combination of several classificationsa | 5 |

| A different systemb | 2 |

| Total | 67 |

PC, Postoperative complications; N, Number of services surveyed.

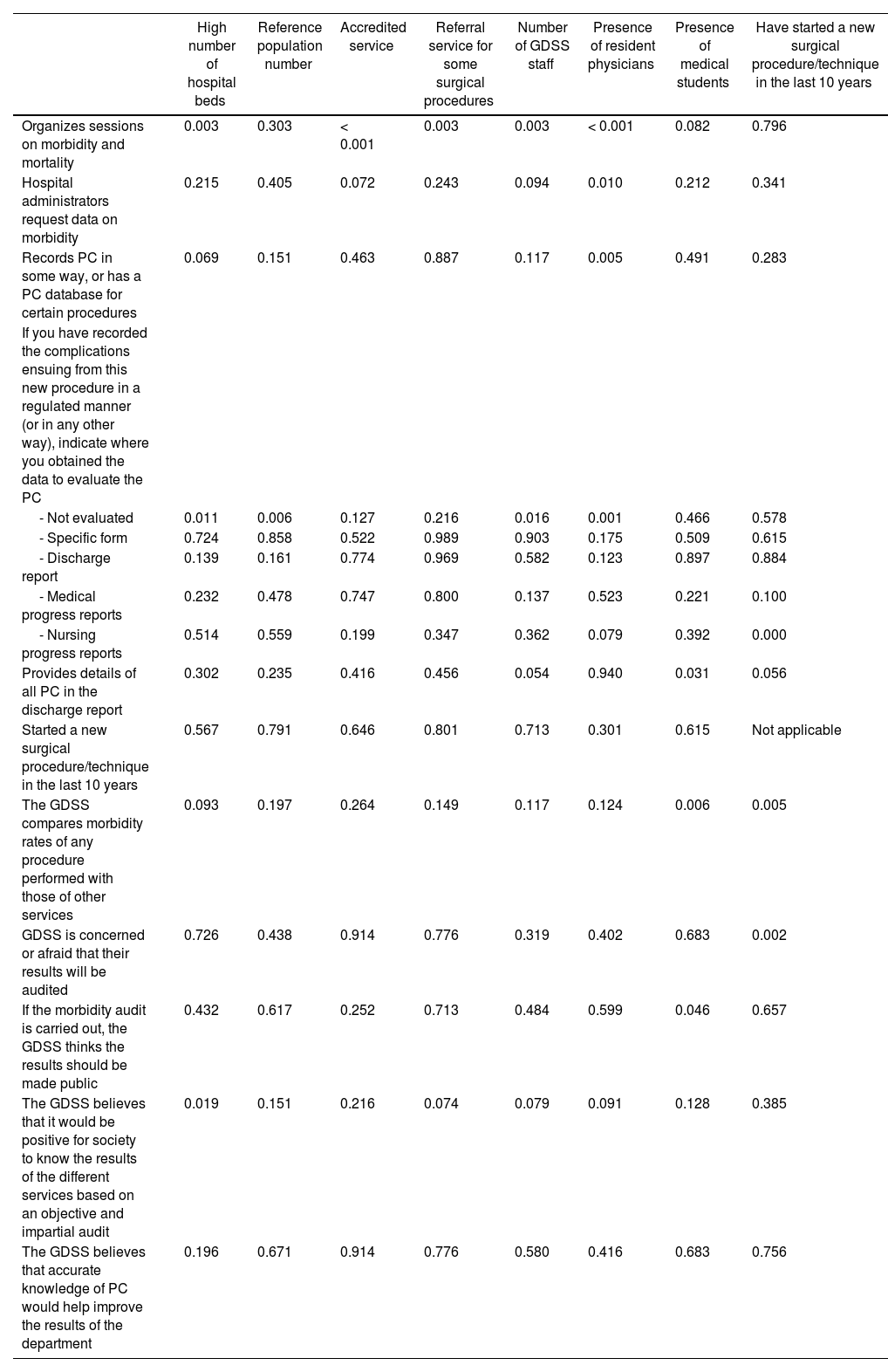

Statistical relationships are presented in Table 6.

Statistical relationships (P-value) between different characteristics of the General and Digestive Surgery Services (GDSS) and the management of Postoperative Complications (PC).

| High number of hospital beds | Reference population number | Accredited service | Referral service for some surgical procedures | Number of GDSS staff | Presence of resident physicians | Presence of medical students | Have started a new surgical procedure/technique in the last 10 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizes sessions on morbidity and mortality | 0.003 | 0.303 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.082 | 0.796 |

| Hospital administrators request data on morbidity | 0.215 | 0.405 | 0.072 | 0.243 | 0.094 | 0.010 | 0.212 | 0.341 |

| Records PC in some way, or has a PC database for certain procedures | 0.069 | 0.151 | 0.463 | 0.887 | 0.117 | 0.005 | 0.491 | 0.283 |

| If you have recorded the complications ensuing from this new procedure in a regulated manner (or in any other way), indicate where you obtained the data to evaluate the PC | ||||||||

| - Not evaluated | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.127 | 0.216 | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.466 | 0.578 |

| - Specific form | 0.724 | 0.858 | 0.522 | 0.989 | 0.903 | 0.175 | 0.509 | 0.615 |

| - Discharge report | 0.139 | 0.161 | 0.774 | 0.969 | 0.582 | 0.123 | 0.897 | 0.884 |

| - Medical progress reports | 0.232 | 0.478 | 0.747 | 0.800 | 0.137 | 0.523 | 0.221 | 0.100 |

| - Nursing progress reports | 0.514 | 0.559 | 0.199 | 0.347 | 0.362 | 0.079 | 0.392 | 0.000 |

| Provides details of all PC in the discharge report | 0.302 | 0.235 | 0.416 | 0.456 | 0.054 | 0.940 | 0.031 | 0.056 |

| Started a new surgical procedure/technique in the last 10 years | 0.567 | 0.791 | 0.646 | 0.801 | 0.713 | 0.301 | 0.615 | Not applicable |

| The GDSS compares morbidity rates of any procedure performed with those of other services | 0.093 | 0.197 | 0.264 | 0.149 | 0.117 | 0.124 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| GDSS is concerned or afraid that their results will be audited | 0.726 | 0.438 | 0.914 | 0.776 | 0.319 | 0.402 | 0.683 | 0.002 |

| If the morbidity audit is carried out, the GDSS thinks the results should be made public | 0.432 | 0.617 | 0.252 | 0.713 | 0.484 | 0.599 | 0.046 | 0.657 |

| The GDSS believes that it would be positive for society to know the results of the different services based on an objective and impartial audit | 0.019 | 0.151 | 0.216 | 0.074 | 0.079 | 0.091 | 0.128 | 0.385 |

| The GDSS believes that accurate knowledge of PC would help improve the results of the department | 0.196 | 0.671 | 0.914 | 0.776 | 0.580 | 0.416 | 0.683 | 0.756 |

The key results of the present survey can be summarized by the following strengths and weaknesses. The strengths were: most of the 67 GDSS that responded were not concerned about the possibility of being audited and thought that it would be positive for society to be informed of the results obtained by the GDSS as determined by objective, impartial audits. They also believed that accurate information on PC would help improve the results of their service, and they thought that morbidity audits should be carried out by a public body. The weaknesses were: there are too many GDSS that do not conduct sessions on morbidity and mortality, are not required by their hospital management authorities to provide morbidity data, do not record PC at all, and used the discharge report as the only source of data for published reports. Most GDSS acknowledged that the discharge reports do not include details about all PC, and one-third acknowledged that no PC were registered when starting a new surgical procedure or technique. These weaknesses (and therefore areas for improvement) have a great impact, especially considering that 75% of the GDSS included in the study trained surgeons, and 93% of the hospitals trained medical students.

To our knowledge, this is the first survey of its kind in the literature. We performed a search in PubMed updated on May 12, 2023, with the following search terms: “postoperative complications” and “survey” and “nation”, obtaining 708 results. Two studies provided data, although not anonymously.10

Hospital administrators and healthcare authorities rarely monitor the morbidity associated with various surgical procedures. In the Netherlands, however, the Dutch National Registry is extremely active in auditing PC and indeed leads the way in this area among comparable countries. The registry audits morbidity results associated with different surgical procedures, although the thoroughness of the methodology is debatable.11–24 Other attempts have been made to audit morbidity in colorectal cancer in Australia and New Zealand,25,26 in adult cardiac surgery in the United Kingdom27 and in endovascular management of abdominal aortic aneurysm in Canada.28 In addition, better outcomes have been reported in patients included in medical audits than among those who are not included.29

In order to reach cross-national conclusions on the real situation of the evaluation of morbidity in surgery departments, it would be necessary to externally validate these results by using similar surveys. The data that emerge from the present study are extremely negative in terms of the low level of monitoring of PC at many GDSS, particularly considering the rather biased impression given of the situation in some of the articles published.

As indicated in previous articles, it is possible for the health authorities to audit all patients operated on in all surgical departments continuously over time. There is a methodology to do this objectively, provided the auditors have no conflict of interest. Electronic health records allow audits to be carried out in a centralized manner, and the CCI is a numerical score of complications that enables comparisons to be made among services. The analysis of the clinical history of a surgical patient, which includes consulting all medical data sources and evaluating the comments of physicians and nurses, takes an average of 5−10 min. Auditing must be maintained over time; one-off audits are not acceptable. Obviously, similar procedures and patients should be compared.5,30,31 In future studies, it would also be important to investigate the difference between adverse events (errors in surgical care) and complications, as well as to reinforce the detection of events in the perioperative period, thereby being able to prevent adverse outcomes.

It is not known how surgical departments manage their data on PC. In general, however, PC are not widely recorded or are only recorded in association with certain surgical procedures.

There are multiple advantages to an impartial audit (avoiding conflicts of interest). It provides patients, surgeons and managers with objective data to be able to determine optimal results, increase efficiency, reduce costs, and avoid errors. This should allow for the definition of a Gold Standard and benchmarking GDSS, while enhancing the quality of publications presenting surgical results. It may even be the case that innovative services and/or techniques with poor results are reference centers for training.1

Society today expects transparency. However, this is rarely achieved in the treatment of surgical results because of the presence of conflicts of interest and bias. Patients have the right to know the likely results of a surgical procedure and, specifically, the morbidity associated with its performance by a particular surgical unit. In addition, surgeons must be accountable for their practices. Unfortunately, audits carried out by the services themselves may involve multiple biases.1,5,30,31

Among the limitations of this study, the first is that the survey was answered by 30% of all the services contacted. The population represented amounted to 15 715 174 inhabitants, accounting for 33% of Spain’s 47 331 302 inhabitants (July 1, 2021).9 Also, this population may be overestimated given that some GDSS share a healthcare region. In addition, it is possible that the AEC database does not contain data for all the heads of GDSS in Spain.

The choice of the head of department as respondent may have increased selection bias; that is, the answers regarding the evaluation of morbidity may have been more positive than if other doctors in the service had responded to the survey. Furthermore, even though the survey was answered anonymously, the influence of conflict of interest cannot be determined.

ConclusionThis study highlights serious deficiencies in the recording and understanding of the real situation of PC in Spanish GDSS. Steps to introduce improvements are urgently required. Most heads of surgical departments agree that auditing by the health authorities is probably the best solution and likely to produce the least bias. We want our research to incite improvements in the registration and communication of PC.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have contributed to the study concept and design, data interpretation, critical review of the intellectual content, and the final approval of the version presented. RDLPL also contributed to the data analysis of the drafted article. All authors are members of the Quality, Safety and Management Section of the Asociación Española de Cirujanos.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare they do not have any conflicts of interest.

The authors are extremely grateful to the Asociación Española de Cirujanos for its support and cooperation and also thank the anonymous surgeons who took the time to complete the survey.

Please cite this article as: de la Plaza Llamas R, Parés D, Soria Aledó V, Cabezali Sánchez R, Ruiz Marín M, Senent Boza A, et al. Evaluación de la morbilidad postoperatoria en los hospitales españoles: resultados de una encuesta nacional. Cir Esp. 2024.