Vat polymerization has been employed to fabricate porous poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA)/hydroxyapatite (HA) composite bioscaffolds and ceramic HA bioscaffolds with controlled geometry for bone tissue regeneration. UV-curable slurries were formulated using bimodal HA powder derived from bovine bones. A bimodal particle size distribution enhanced powder packing density and mechanical properties, ensuring effective sintering. Tartrazine (0.14wt%) was incorporated as a photoabsorber to improve geometrical accuracy and the printability of complex bioscaffold architectures. Rheological analysis revealed viscosity dependence on solid content, with 50wt% HA providing superior dispersion stability. Sintering at 1250°C facilitated densification, achieving the highest compressive strength (4.7MPa for G50 samples) and exhibiting the highest porosity (89% for G30 samples). Notably, the mechanical properties of both sintered and non-sintered samples were examined, revealing comparable results, thereby demonstrating the robustness of the developed materials and processes.

La fotopolimerización se ha empleado para fabricar andamios de composición PEGDA (polietilenglicol diacrilato) e hidroxiapatita (HA), así como andamios cerámicos de HA con geometría controlada para ser aplicados en la regeneración de tejido óseo. Se formularon suspensiones fotocurables utilizando un polvo de distribución de tamaño bimodal de HA obtenido a partir de huesos de origen bovino. La distribución bimodal del tamaño de partícula mejoró la densidad de empaquetamiento del polvo y las propiedades mecánicas, garantizando una sinterización efectiva. Se incorporó tartrazina (0.14% en peso) como fotoabsorbente para mejorar la precisión geométrica y la imprimibilidad de arquitecturas complejas de los andamios. El análisis reológico reveló que la viscosidad depende del contenido sólido, siendo 50% en peso de HA el valor que proporcionó mayor estabilidad en la dispersión. La sinterización optimizada a 1250°C facilitó la densificación, logrando la mayor resistencia a la compresión (4,7MPa para muestras G50) y exhibiendo la mayor porosidad (89% para muestras G30). Cabe destacar que se evaluaron las propiedades mecánicas tanto de las muestras sinterizadas como de las no sinterizadas, revelando resultados comparables y demostrando así la robustez de los materiales y procesos desarrollados.

Nowadays, bioceramics are widely used to repair bone defects. Bioceramics have unique properties such as bioactivity, osteoconductivity, and in some cases biodegradability, which make them ideal for interacting with living tissues [1]. HA is one of the main members of the calcium apatite family, which has structural and chemical similarities to natural bone [2]. Known for its bioactive and biocompatible properties, HA commonly used for bone tissue regeneration (osteogenesis) and as a carrier in drug delivery systems [3]. Serving as an artificial bone substitute, HA facilitates the adhesion, proliferation, and mineralization of bone cells on its surface [4].

Natural HA can be derived from animal bones [5]. Studies have shown that treating animal bones at high temperatures or with aqueous solutions of NaOH and KOH effectively removes organic components, leading to the formation of natural HA [6–8].

The wide use of HA bioscaffolds is limited by their mechanical properties, particularly brittleness and low elastic modulus. It is often combined with different biocompatible polymers to fix bone tissues and deal with bone defects [9]. To improve this disadvantage polymers are used with ceramic composites [10,11]. The polymer-ceramic bioscaffolds also have disadvantages, such as the possibility of polymer degradation over time in biological environments and low mechanical strength [12].

It was reported that the mechanical properties of the bioscaffolds depend on their porosity, pore size distribution, and structure [13]. The microstructure cannot be controlled by traditional methods, such as gel-casting [14], freeze casting [15], foam replica [16], hydrothermal [17]. Conversely, additive manufacturing (AM) enables the creation of complex geometric bioscaffolds, matching the structure to the designed architecture to mimic the functionality of hard tissue [18]. Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP) are vat polymerization technologies that have attracted considerable attention for the manufacturing of bioceramics and bioceramic-polymer composites [19,20].

Porosity and pore size distribution not only influence mechanical properties but also affect the bioactivity of the bioscaffolds. Particularly, interconnected pores with a diameter greater than 400μm are necessary for the migration and proliferation of osteoblasts and stem cells, which have sizes of 15–50μm and 5–12μm, respectively [21]. Such porosity is necessary for transporting nutrients and metabolic wastes effectively [22]. Therefore, the precise control of the microstructure of the bioscaffolds plays significant role in cell activity, mechanical functionality, and bone tissue regeneration.

Achieving high-quality porous structures requires careful optimization of the photoabsorber and photoinitiator (PI) concentrations. The photoabsorber regulates light penetration by selectively absorbing irradiation, allowing precise control over the polymerization depth. This prevents excessive light penetration, ensuring accurate, well-defined features in the fabricated structures [23]. There are numerous attempts to precisely control the geometry and porosity of the bioscaffolds [24,25]. Even though one can design CAD models with unrealistically thin walls (fine structures), the printed objects produced exhibit more blurred features. Schrijnemakers et al. concluded that the fine structures can be achieved by controlling the energy doses [26]. They succeeded in manufacturing of complex shape structures with >1mm wall thickness HA based samples. Chen et al. designed implants with micro-holes with of hexagonal shape in diameter of 500μm. After printing the shape of holes were changed to oval [27]. Navarrete-Segado et al. found out that the printing orientation influences on the accuracy/reproducibility of the model structure [17]. Baino et al. [28] used commercial LithaBone HA 480 E slurry (unknown composition) to prepare 3D porous bioscaffolds with macropore size is in the range of 100–800μm. The structure of the sintered bioscaffolds closely reproduced the initial structure. The wall thickness (strut diameter) was about 259±30μm.

The primary aim of this study is to develop and optimize a novel ceramic UV-curable slurry for SLA of bioscaffolds with controllable geometry. The influence of the photoabsorber, particularly tartrazine, on the geometrical resolution and mechanical properties of HA and HA-PEGDA bioscaffolds was investigated. Bovine-derived HA with a bimodal particle size distribution was used as the source of bioceramic.

Materials and methodsMaterialsNatural HA extracted from bovine bone. PEGDA was used as a photopolymer (Mw=575g/mol, MDL Number: MFCD00081876, Sigma–Aldrich, Germany), diphenyl (2,4,6-trimethyl-benzoyl) phosphine oxide (TPO, 97%, MDL Number: MFCD00192110, Sigma–Aldrich, Germany) was used as a PI, and tartrazine dye (MDL Number: MFCD00148908, Sigma–Aldrich, Germany) was used as a photoabsorber.

Preparation of HA powderBeforehand, the cleaned and treated bone [29] was cut into small pieces and dried for 4h at 250°C. The obtained pieces were thermally treated in a furnace (Atmosphere Muffle Furnace GCF 1400, Across International) for 5h at 900°C heating rate of 5°C/min. The calcined pieces were milled in a planetary mill (Vertical Planetary Ball Mill BKBM-V2) at 240rpm for 6h using zirconia balls with diameters of 8mm and 10mm (weight ratio 2:1, respectively), at a ball-to-powder weight ratio of 7:1. The resultant HA powder underwent sieving through a 325-mesh sieve to remove large particles.

Slurry preparation for vat polymerizationUV-curable slurries were prepared by dissolving TPO in PEGDA under continuous stirring at 600rpm using a magnetic stirrer for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). Once the PI was fully dissolved, tartrazine was introduced and mixed under identical conditions until complete dissolution was achieved. Natural HA was then added and dispersed using a mechanical stirrer at 300rpm for 2h at RT to ensure uniform distribution and homogeneity of the slurry. To prevent premature polymerization, all preparation, mixing, and storage steps were conducted under light-protected conditions. The compositions of all slurries are presented in Table 1.

Slurries composition and printability.

| Slurry | PEGDA (wt%) | HA (wt%) | TPO (wt%) | Tartrazine (wt%) | Printability | Sample name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL1 | 70 | 30 | 0.1 | – | Printed without pores | C30.1 |

| SL2 | 70 | 30 | 0.1 | 0.03 | Printed without pores | C30.2 |

| SL3 | 70 | 30 | 0.1 | 0.1 | Printed without pores | C30.3 |

| SL4 | 70 | 30 | 0.1 | 0.14 | Printed with pores | C30.4G30 |

| SL5 | 70 | 30 | 0.1 | 0.2 | Printed with pores, soft | C30.5 |

| SL6 | 70 | 30 | 0.1 | 0.25 | Not printable | C30.6 |

| SL7 | 60 | 40 | 0.15 | 0.14 | Printed with pores | G40 |

| SL8 | 50 | 50 | 0.2 | 0.14 | Printed with pores | G50 |

In this study, the samples were printed using vat polymerization, specifically SLA technology (Formlabs, Form 2, 405nm). The printer utilizes a layer-by-layer approach with a 0.1mm layer thickness, ensuring high precision in fabricating complex geometries. The printed samples were cleaned with isopropyl alcohol for 5min to remove any unpolymerized slurry and then dried at RT for 12h to ensure complete evaporation of the solvent and stabilization of the printed structures.

Two different 3D structures were printed: a cylindrical mesh (C) (10mm×7mm, H×D) and a gyroid structure (G) (10mm×10mm×10mm) (Fig. 1).

Mesh structures were initially chosen to evaluate and improve the printability of the slurries, as they allow for easier visualization of printed pore structures and assessment of resolution. This approach helped optimize the formulation and printing parameters. After achieving satisfactory printability, we transitioned to gyroid structures due to their well-known advantage in providing improved mechanical properties.

Following 3D printing, the samples underwent a two-stage thermal post-processing procedure consisting of debinding and sintering. Debinding was performed using an furnace (MLM D13-12L, Termolab, Portugal), during which the temperature was increased step by step to 400°C. Subsequently, sintering was carried out at 1250°C in a high-temperature furnace (MLR 18-12L, Termolab, Portugal). Finally, the samples were cooled to RT inside the furnace (see Section 3.3).

CharacterizationParticle size measured by laser scattering using Mastersizer 3000 equipment (Malvern Panalytical B.V., Almelo, and The Netherlands).

Phase characterization was accomplished using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The data on the phase composition were collected by Rigaku MiniFlex 600 X-ray diffractometer (40mA, 40kV, CuKα radiation, λ=0.1542nm, step size of 0.02°, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with a D/teX Ultra 250 1D detector and processed via the JCPDS-ICDD database.

Chemical analysis was carried out by X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) using MagiX from Philips Co.

Microstructural characterization was performed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Prisma E, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Hillsboro, OR, USA), equipped with an EDS detector. Samples were coated with a 20nm layer of Au to provide sufficient conductivity.

Rheological properties were measured using a rheometer (Anton Paar MCR 92 Software: Rheocompass, Austria) at 25°C with a shear rate range of 0.1–100s−1.

The thermal treatment was conducted with an electric furnace (MLR 18-12L, Termolab, Portugal). Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis was performed by devise STA 449 F3 Jupiter with SKIMMER Furnace (NETZSCH, Germany). Dilatometry was performed using a horizontal dilatometer, DIL L75 HX 1600 (LINSEIS, Germany).

The compressive strength of the samples was measured using a universal mechanical testing machine (Instron Legend 5965 testing system, USA), equipped with a 5kN load cell, with a crosshead speed of 20mm/min at RT.

Relative density (pr) was measured [30] by Eq. (1):

where Pb is the bulk density of the HA sintered bioscaffold, which was calculated using the geometric method, and Pt stands for the theoretical density of HA (3.16g/cm3)

Total porosity (P) was determined [31] using an Eq. [2]:

where Pb represents the density of HA bioscaffolds.The sintering shrinkage [32] for each axis (x, y, z) of HA bioscaffolds was calculated by Eq. [3]:

where η is sintering shrinkage (%), L and L1 are sample lengths (mm) before and after sintering, respectively.Results and discussionPowderThe particle size distribution of HA powder extracted from bovine bone is shown in Fig. 2a. This bimodal characteristic, with particle size ranges of 0.2–2μm and 5–50μm is beneficial for the sintering process, as the bimodal particle size distribution can significantly improve packing density, enhance mechanical properties, thereby promoting effective densification during the sintering process [33].

Fig. 2b displays the XRD patterns of natural HA powder in comparison with standard HA (JCPDS No. 9-432). The main diffraction peaks of the natural HA align precisely with those of standard HA, confirming the phase purity and crystallinity of the synthesized material.

The morphology of HA powder is shown in Fig. 2c, d. SEM micrographs illustrate that the HA powder is free from significant agglomerates (Fig. 2d). The particle size plays a crucial role in the stability of the slurry [34]. The particle size distribution ensures consistent photopolymerization during SLA, which is critical for achieving improved mechanical and structural properties in the final bioscaffolds [35].

The EDS spectrum revealed calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), and oxygen (O) as the primary elements, confirming the characteristic composition of HA (Fig. 2e).

As EDS provides qualitative to semi-quantitative elemental data, XRF analysis was additionally employed to obtain a more accurate quantitative determination of the Ca/P atomic ratio. According to XRF results, the Ca/P nominal (atomic) ratio of the extracted HA was found to be close to 1.67. The obtained ratio is slightly higher than the theoretical value, although it remains within the uncertainty range of XRF measurements, particularly due to the error propagation associated with division operations in ratio calculations.

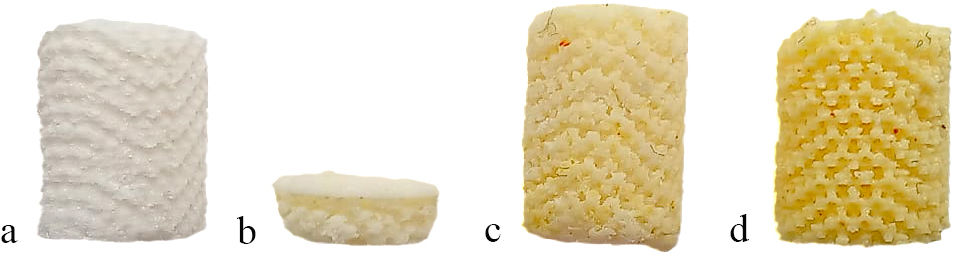

SlurryInitially, the slurries (SL1–SL6) were used to print mesh structures (C30.1–C30.6) to improve pore printability. The first slurry formulation (SL1) contained 30wt% solid loading and 0.1wt% photoinitiator (based on PEGDA), without the addition of a photoabsorber. However, printing was unsuccessful, as the resulting cylindrical mesh samples (C30.1) lacked porosity (Fig. 3a). To address this issue and achieve a porous structure, tartrazine was selected as a photoabsorber and incorporated into the slurry. Without a photoabsorber, light penetrates too deeply into the layers, leading to uncontrolled polymerization and reduced printing accuracy as observed by other authors [36].

Initially, a tartrazine concentration of 0.03wt% and 0.1wt% (calculated based on PEGDA) was added to the slurry, producing printed cylindrical samples (C30.2, C30.3) with minimal porosity (Fig. 3b, c). To further enhance porosity, the concentration of tartrazine in slurry (SL4) was gradually increased, resulting in porous samples (C30.4) at 0.14wt%. At this concentration, the printed samples exhibited well-defined structural characteristics and good porosity (Fig. 3d) (see Section 3.4). However, when the tartrazine concentration exceeded 0.14wt%, the printed samples became (C30.5) overly soft, rendering the slurries (SL5, SL6) unsuitable for the SLA process.

To continue the development process, after optimizing the slurry formulation using mesh structures, the sample geometry was changed to a gyroid design. While cylindrical mesh structures were beneficial for evaluating the printability and optimizing the pore resolution during the early stages, they lacked mechanical complexity. Gyroid structures, in contrast, offer a continuous, triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) architecture, which is well known for combining high porosity with improved mechanical performance. Additionally, gyroids closely mimic the anisotropic and interconnected structure of trabecular bone, making them suitable candidates for bone bioscaffold applications. This transition allowed for a more relevant assessment of the mechanical behavior and application potential of the final composite materials.

After optimizing the photoabsorber concentration (0.14wt%), solid loading was adjusted from 30wt% to 50wt%. However, incomplete prints occurred. To resolve this issue, the PI concentration was increased from 0.1wt% to 0.2wt%, leading to final formulations (SL7, SL8) that successfully produced printed gyroid samples. The compositions of the different slurries are shown in Table 1.

The increase in solid loading affects the rheological properties of the ceramic slurry. Fig. 4a shows the viscosity of the slurries with different solid loadings at shear rates of 0.1–100s−1. The viscosity of all slurries decreased with increasing shear rate (Fig. 4a). It is noteworthy that with increasing solid loading, the viscosity also increases correspondingly due to enhanced particle interactions and reduced free movement of the liquid phase [37]. The shear stress increases with shear rate for all slurries, further confirming non-Newtonian behavior. SL8 exhibits the highest shear stress at all shear rates, indicating higher resistance to flow, likely due to increased solid loading (Fig. 4b).

To evaluate the stability of the slurries containing 30, 40, and 50wt% HA, sedimentation tests were performed by observing the degree of particle settling after 24h at RT.

The sedimentation test revealed noticeable settling in the 30wt% solid loading slurry after 24h, indicating low dispersion stability. The reason is the low viscosity of the slurry, which reduced frictional resistance during particle movement, allowing particles to aggregate and sediment easily. In contrast, the 40–50wt% solid loading slurries exhibited significantly higher viscosity, increasing frictional resistance and preventing particle sedimentation. As a result, these slurries demonstrated minimal settling, suggesting improved homogeneity and better particle suspension (Fig. 4c).

Following SLA, the green samples (polymer based composites) underwent microstructural analysis (see Section 3.4) and mechanical testing (see Section 3.5).

Post processingTG was conducted to investigate the thermal behavior of the PEGDA-HA composite green body (Fig. 5a). The TG curve shows mass loss in multiple stages, the moisture evaporation (<200°C) and organic decomposition (200–500°C). The results indicated that photopolymer (PEGDA) degradation begins at approximately 200°C. To ensure complete removal of the photopolymer and avoid defects such as cracks, the debinding process was carefully controlled and extended appropriately. For the sintering process, dilatometry was performed to determine the optimal temperature, and a sintering temperature of 1250°C was chosen accordingly (Fig. 5b). The dried samples were subjected to debinding and sintering in a furnace to remove the organic components and promote ceramic particle densification. The debinding and sintering schedule is shown in Fig. 5c.

Microstructural analysisFigs. 6 and 7 depict the microstructure of gyroid samples (G30–G50), while Fig. 8 shows a representative cylindrical mesh sample (C30.4), used during the optimization stage of the printing process.

A microstructural analysis of green samples (G30–G50) is illustrated on Fig. 6. The results showed no cracks or damage (Fig. 6b, d and f), with a homogeneous distribution of HA powder. Importantly, no significant agglomerates of HA powder were observed (Fig. 6(c, e and g).

Fig. 7 represents a microstructural analysis of the sintered (ceramic) G30–G50 samples. The bioscaffolds retained their intended shape after sintering, as shown in Fig. 7a. In case of, G30 samples (Fig. 7b, c) noticeable porosity was observed, resulting in brittleness after sintering. This brittleness is attributed to the lower HA content, which hampers densification during sintering. In contrast, Fig. 7d–g demonstrates that increasing the powder content from 30wt% to 50wt% effectively mitigates this issue, resulting in samples with improved structural integrity.

A microstructural analysis of the sintered C30.4 samples is shown in Fig. 8a, b, with uniform, well-distributed macropores (∼100–200μm). Bioscaffold maintains its intended cylindrical shape after sintering. No significant warping or geometric distortion was observed, indicating good shape retention and dimensional stability of the printed structures during sintering, despite the expected material shrinkage. At higher magnification, the bioscaffold exhibits polygonal HA grains (∼10–25μm), indicating a controlled sintering process. The formation of distinct grain boundaries suggests a balance between densification and porosity. The bioscaffold maintains a well-defined macroporous structure while exhibiting microporosity, which can enhance mechanical interlocking with surrounding tissues.

Mechanical propertiesThe relative density, total shrinkage and porosity of sintered HA bioscaffolds are presented in Table 2. Results showed that the G30 samples experienced the highest level of shrinkage rate. This is due to the low amount of HA powder, as it can cause large shrinkage deformation, cracks and defects after sintering. The overall total porosity of the bioscaffolds was relatively high, with a porosity value of approximately 89% for samples containing 30wt% HA. The primary reason for this increased porosity is the internal shrinkage that occurs during thermal sintering. The total porosity of bioscaffolds is crucial because it facilitates the absorption of nutrients and the excretion of metabolic waste, thereby creating a suitable environment for bone tissue growth [37].

Dimensions and properties of green and sintered samples.

| Samples name | Green samples (HxLxW) (mm) | Sintered samples (HxLxW) (mm) | Relative density after sintering (%) | Total porosity after sintering (%) | Total shrinkage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G30 | 10×10×10 | 7.3×8.5×8.6 | 89 | 89 | 19 |

| G40 | 10×10×10 | 8×9.1×9.1 | 84 | 84 | 13 |

| G50 | 10×10×10 | 8.5×9.2×9.2 | 78 | 78 | 10 |

The results of the compression test are presented in Fig. 9a. For G30 samples, the compressive strength improved slightly from 0.8MPa to 1.0MPa after sintering. The limited strength gain and high shrinkage suggest incomplete densification within the green bioscaffold. The compressive strength was similar to green and sintered samples, but the mechanical behavior is different. Green samples exhibited elastic behavior deforming under stress and returning to their original shape after load removal, which is a characteristic property of polymers. In contrast, sintered samples were brittle exhibiting limited deformation before cracking under stress, which is typical for ceramics.

A notable improvement in compressive strength was observed in the G40 and G50 samples, reaching up to 4.7MPa. This indicates that the compressive strength increases with the amount of HA (Fig. 9c).

Cylindrical mesh samples (C30 series) were not evaluated for mechanical properties due to their brittle structure and use solely for printability optimization during slurry development.

ConclusionsIn this study, we successfully optimized the formulation and processing of a photocurable ceramic slurry for vat polymerization. The use of HA powder with a bimodal particle size distribution (0.2–2μm and 5–50μm) improved packing density and mechanical performance, supporting effective sintering. XRD analysis confirmed the phase purity of HA derived from bovine bone.

To enhance printability and structural accuracy, tartrazine was incorporated as a photoabsorber at an optimal concentration of 0.14wt%. Increasing the HA solid loading from 30wt% to 50wt% necessitated corresponding adjustments in photoinitiator content (0.1–0.2wt%) to maintain adequate curing. Rheological characterization revealed a strong dependence of viscosity on solid content, with slurries containing 40–50wt% HA demonstrating higher viscosity, improved dispersion stability, and reduced sedimentation.

Post-sintering analysis showed that bioscaffold porosity and density varied with HA content, directly affecting mechanical properties.

The compressive strength of the sintered G50 sample (4.7MPa) is comparable to or slightly higher than that of similar HA-based bioscaffolds fabricated by DLP reported in recent literature, where compressive strength values typically range from 1 to 4MPa [38,39].

Among the evaluated geometries, gyroid bioscaffolds outperformed cylindrical mesh structures in terms of mechanical strength, shape retention, and applicability for load-bearing tissue engineering. Cylindrical structures were mainly used to optimize printability and were not suitable for mechanical testing due to their fragile architecture.

Among all tested formulations, the 50wt% HA gyroid structure demonstrated the best overall performance in terms of mechanical strength, dimensional stability, and biomedical relevance, making it the most promising candidate for bone tissue engineering applications.

These findings offer valuable insights into optimizing the composition and processing of SLA-fabricated polymer-based composites and ceramic HA bioscaffolds for biomedical applications, particularly in bone tissue engineering.

Future studies will focus on evaluating the biocompatibility and performance of the optimized bioscaffolds in in vivo models to further assess their potential for clinical applications.

CRediT authorship contribution statementLiana Mkhitaryan: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Lilit Baghdasaryan: Investigation, Formal analysis. Zhenya Khachatryana: Investigation, Formal analysis. Marina Aghayan: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Miguel A. Rodríguez: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Viktorya Rstakyan: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This work was supported by the Higher Education and Science Committee Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport RA [grant number №22rl-050, 2022].