Although monolithic ceramics have many desirable properties, such as high-temperature resistance, excellent hardness, and chemical inertness, they also have limitations that can restrict their use in various applications. The limitations include, but are not limited to, low fracture toughness, low ductility, high electrical resistance, and low thermal conductivity. Researchers have been able to address some of these limitations by developing ceramic composites, nanocomposites, and hybrid nanocomposites. The later are ceramic matrices that incorporate two or more reinforcements. They represent an advanced class of materials that combine the excellent characteristics of monolithic ceramics and the outstanding properties of the reinforcements, offering exceptional mechanical, thermal, and functional properties for advanced applications. There are many comprehensive review papers on ceramic composites and nanocomposites, however, only one review paper on hybrid ceramic nanocomposites has been published, and it was dedicated solely to alumina-based nanocomposites prepared by spark plasma sintering. The aim of this work is to review the properties of hybrid ceramic nanocomposites, highlight their potential applications in various industries, and formulate directions for future research endeavors.

Aunque las cerámicas monolíticas tienen muchas propiedades deseables, como resistencia a altas temperaturas, excelente dureza e inercia química, también tienen limitaciones que pueden restringir su uso en diversas aplicaciones. Las limitaciones incluyen, pero no se limitan a, baja tenacidad a la fractura, baja ductilidad, alta resistencia eléctrica y baja conductividad térmica. Los investigadores han podido abordar algunas de estas limitaciones desarrollando compuestos cerámicos, nanocompuestos y nanocompuestos híbridos. Estos últimos son matrices cerámicas que incorporan dos o más refuerzos. Representan una clase avanzada de materiales que combinan las excelentes características de las cerámicas monolíticas y las propiedades sobresalientes de los refuerzos, ofreciendo propiedades mecánicas, térmicas y funcionales excepcionales para aplicaciones avanzadas. Hay muchos artículos de revisión exhaustivos sobre compuestos cerámicos y nanocompuestos; sin embargo, solo se ha publicado un artículo de revisión sobre nanocompuestos cerámicos híbridos, y este se dedicó exclusivamente a nanocompuestos a base de alúmina preparados por sinterización por plasma de chispa. El objetivo de este trabajo es revisar las propiedades de los nanocompuestos cerámicos híbridos, resaltar sus aplicaciones potenciales en diversas industrias y formular direcciones para futuros esfuerzos de investigación.

Ceramics are materials used in various engineering applications because of their unique properties. Some of their important characteristics include: (i) the ability to withstand high temperatures, (ii) excellent wear and abrasion, (iii) chemical resistance, (iv) electrical insulation, (v) biocompatibility, and (vi) lightweight and low density [1–4]. These properties make ceramics suitable for: (i) use in harsh environments, (ii) manufacturing of cutting tools, bearings, and wear-resistant coatings, (iii) applications where corrosion resistance is critical, such as in the chemical industry, semiconductor manufacturing, and healthcare, (iv) electrical and electronic applications where high levels of insulation are required to prevent electrical leakage or short circuits, (v) medical implants and dental prosthetics, and (vi) applications where weight reduction is important, such as in the transportation, automotive, and aerospace industries [1–4]. Nevertheless, the utilization of ceramics in some applications has been restricted because of their low resistance to fracture, insufficient strength, high electrical resistance, and low thermal conductivity. As a result, composites [5], nanocomposites [6], and hybrid nanocomposites [7] were developed to overcome the limitations of unreinforced ceramic materials. Composites are materials made up of a matrix that incorporates particles, whiskers, fibers, or sheets, resulting in enhanced properties when compared to ceramics that are not reinforced. Additional enhancements to the properties have been achieved through the development of nanocomposites and hybrid nanocomposites. In the former, the matrix is reinforced with a single phase, while in the latter, the matrix is reinforced with two or more phases that have different dimensionalities, morphologies, and properties. Fig. 1[14] shows typical reinforcements and structures for ceramic nanocomposites while Fig. 2[33] displays the structure of Al2O3–SiC–CNTs nanocomposites. In the later, CNTs are present within the grain boundaries of Al2O3 while SiC particles are present within grains and at the grain boundaries. The properties of hybrid ceramic nanocomposites are influenced by: (i) the inherent characteristics, type, size, dimensionality (0D, 1D, 2D), and distribution of the reinforcements, (ii) nature and composition of the matrix, and (iii) process parameters. The matrix offers high strength, high hardness, and thermal stability, while the reinforcements further improve these properties and adds functionalities such as enhanced toughness, wear resistance, and electrical, magnetic, or optical properties. This enables the development of materials with tailored properties that are well-suited for a wide range of applications [8–13]. Review papers on ceramic composites and nanocomposites can be found in the literature [14–20]. However, only one review paper on spark plasma sintered hybrid ceramic nanocomposites [7] has been published so far. The objective of this work is to review the properties of hybrid ceramic nanocomposites, highlight their potential applications in various industries, and formulate directions for future research endeavors.

Some common nanoreinforcements and nanocomposite structures for ceramics. (a) zero-dimensional (0-D) round nanomaterials, (b) one-dimensional (1-D) needlelike-shaped nanomaterials, (c) two-dimensional (2-D) platelike shaped nanomaterials, (d) 0D nanomaterials embedded in the matrix grains, located at the grain boundaries or occupy both inter- and intra-granular positions, (e) 1D nanomaterials embedded in a micronic matrix, (f) 2D nanomaterials embedded in a micronic matrix, and (g) mixture of 0D and 1D nanoscale phases that are embedded in a micron-sized matrix [14].

A schematic of hybrid microstructure design [53].

Carbonaceous reinforcements, such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphite, and graphene, along with other reinforcements like SiC, exhibit outstanding mechanical and physical properties that make them highly suitable for enhancing the performance of ceramic composite materials. For example, CNTs have a high stiffness of around 1TPa [21,22] and a tensile strength of up to 60GPa [23]. As for thermal properties, at 300K, CNTs have an electrical conductivity of around 106S/m for single walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and greater than 105S/m for multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) [24,25]. Moreover, they have very high thermal conductivity [26,27], with room temperature measured values of 3000W/mK for MWCNTs [28] and 3500W/mK for SWCNTs [29]. Graphene is a two-dimensional material consisting of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms and has exceptional mechanical properties. A perfect single-layer graphene has a stiffness of 1.0TPa and a fracture strength of 130GPa [30]. In contrast to monolayer graphene, graphene nanosheets (GNSs) or graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) possess outstanding mechanical properties [31–33]. The stiffness of GNPs with a thickness of 2–8nm is reported to be around 0.5TPa [34]. The fracture toughness of graphene was found to be equal to 4MPam1/2[35]. Graphene possesses outstanding in-plane thermal conductivity in the range of 1000–5300W/mK and through-plane thermal conductivity in the range of 5–20W/mK. The room temperature thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene was reported to be around 5300W/mK [36]. Moreover, graphene has a negative coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) of −1.28×10−6 to −8×10−6K−1[37,38]. SiC is known to have a hardness of approximately 30GPa [39], and it possesses a thermal conductivity and CTE of 200–300W/mK and 4.5×10−6K−1, respectively [40].

Hybrid ceramic nanocompositesAl2O3 nanocompositesAlumina is the most widely applied and investigated ceramic material because of its exceptional mechanical properties and excellent thermal stability. However, its inherent brittleness limits its use in a wider range of structural applications [41]. Improvements in alumina toughness were made possible through the addition of a second phase such as CNTs [41–44], SiC [41,45–48], graphene [49,50], TiC [51], WC [51], and Si3N4[52]. Additionally, it was found that reinforcing alumina with two phases, resulting in hybrid nanocomposites, can further improve its properties through the synergistic toughening mechanisms of reinforcements [53]. Below is a summary of published work on alumina-based hybrid nanocomposites.

Al2O3–SiC–CNTs nanocompositesHybrid microstructure design for Al2O3–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite materials was first introduced by Ahmad and Pan [53]. The authors prepared alumina and Al2O3–1vol.%SiC–(5, 7, 10)vol.% CNTs hybrid nanocomposites through spark plasma sintering (SPS) at 1550°C. The relative density of alumina was found to be 100%, but decreases with the increase in the reinforcement content and reached 95.1% for Al2O3–1vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs nanocomposite. Although no significant reduction in hardness was observed, the fracture toughness and bending strength of the nanocomposites increased by 117 and 44%, respectively, compared to alumina. In another study, Ahmad et al. [54] reported the effect of SiC on the microstructure of spark plasma sintered Al2O3–(1–3)vol.%SiC–5vol.% CNTs nanocomposites as presented in Figs. 3 and 4, and on the mechanical properties as shown in Fig. 5[54]. A 104% increase in fracture toughness and 46% increase in bending strength were reported for the Al2O3–1vol.% SiC–5vol.%CNTs nanocomposite, compared to alumina. Al2O3 thermal conductivity decreased from 29.5 to 23W/mK at 1vol.% SiC and 5vol.% CNTs and further decreased with an increase in reinforcement content. A very high electrical conductivity of 9S/m was reported for the Al2O3–3vol.% SiC–5vol.%CNTs nanocomposite, compared to 10−12S/m for alumina.

Microstructure of Al2O3–SiC–CNT hybrid nanocomposites [54].

Toughening in Al2O3–SiC–CNT hybrid nanocomposites [14].

Properties Al2O3–(1–3)vol.% SiC–5vol.% CNT hybrid nanocomposites [54].

Mohammad and Saheb [55] used molecular level mixing to prepare homogeneous Al2O3–5wt.%SiC–1wt.%CNTs nanocomposite powder with uniform distribution of SiC and CNTs, and sintered it using SPS at 1500°C. They obtained full density alumina (100%), but the relative density of the nanocomposite decreased to 91.65%. The fracture toughness of the nanocomposite increased by 33% compared to alumina, while a slight decrease in hardness (4%) was observed. In another work, Saheb and Mohammad [56] investigated the influence of SiC and CNTs on mechanical and microstructural properties of Al2O3–SiC–CNTs hybrid nanocomposites as shown in Fig. 6[36]. Al2O3–(5, 10)wt.%SiC–(1, 2)wt.%CNTs nanocomposite powders were prepared using sonication and ball milling. Spark plasma sintering at 1500°C resulted in densification higher than 98% for all samples. All nanocomposites showed improved hardness than alumina (18.56HV) except Al2O3–10wt.%SiC–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite (17.5HV), which was attributed to low densification. An increase of a maximum of 12.12% in hardness was reported for Al2O3–10wt.%SiC–1wt.%CNTs nanocomposite. Similarly, all nanocomposites displayed enhanced fracture toughness values, with maximum increase of 93.95% for Al2O3–10wt.%SiC–2wt.%CNTs, compared. The effect of varying sintering temperature on microstructural and mechanical properties of Al2O3–5wt.%SiC–1wt.%CNTs nanocomposite was investigated by Saheb and Mohammad [57]. Nanocomposite powder, produced by molecular level mixing, was spark plasma sintered at 1500°C, 1550°C and 1600°C. The relative density, hardness, and fracture toughness were found to increase with the increase in temperature, and reached maximum values of 98.91%, 23.32GPa, and 7.10MPam1/2, respectively, at 1600°C. The increase in hardness (25.65%) and fracture toughness (96.67%) compared to monolithic alumina was attributed to higher densification, finer microstructure, change of fracture mode to transgranular along with other toughening mechanisms such as CNTs pull-out, CNTs breaking, crack deflection and crack bridging. In another work, Saheb and Hayat [58] reported thermal and electrical properties of spark plasma sintered Al2O3–SiC–CNT hybrid nanocomposites as shown in Fig. 7[58]. Thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat capacity values of 34.44W/mK, 7.62mm2/s and 1.24J/gK for alumina decreased to 21.2W/mK, 6.64mm2/s and 0.87J/gK, respectively, for the Al2O3–5wt.%SiC–1wt.%CNTs nanocomposite. These properties continued to decrease with further addition of reinforcements. However, a drastic increase in electrical conductivity was observed with the addition of SiC and CNTs reinforcements, where the electrical conductivity of alumina increased from 6.87×10−10S/m to 8.87S/m for the Al2O3–5wt.%SiC–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite. Siddique et al. [59] presented a model for the estimation of thermal conductivity of spark plasma sintered Al2O3–SiC–CNTs hybrid nanocomposites. In the proposed model, thermal conductivity was taken as a function of average matrix crystallite size compared to conventional approach of using constant thermal conductivity for the matrix. They found good agreement between the predicted and experimentally measured values, as shown in Fig. 8[59].

Properties of Al2O3–SiC–CNTs hybrid nanocomposites prepared by spark plasma sintering (a) density, (b) hardness, and (c) fracture toughness [56].

Physical properties of spark plasma sintered Al2O3–SiC–CNT hybrid nanocomposites (a) relative density, (b) electrical conductivity, (c) thermal conductivity, (d) thermal diffusivity, and (e) specific heat capacity [58].

Predicted and measured thermal conductivity of alumina as a function of its average crystallite size [59].

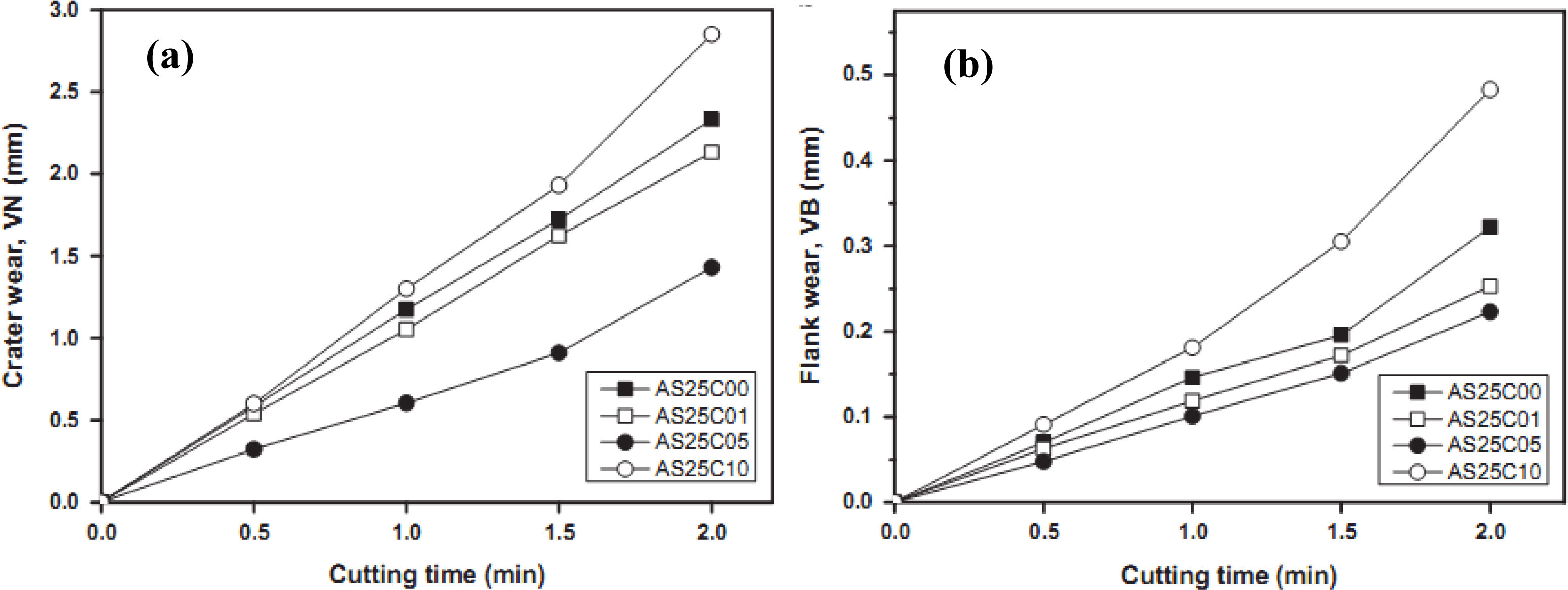

Ahmad and Islam [60] investigated the effect of SiC nanoparticles and CNTs on mechanical properties, bonding characteristics, and thermal stability of Al2O3–SiC–CNTs hybrid nanocomposites. The relative density of inductive hot-pressed Al2O3–6wt.%SiCnp–4wt.%CNTs nanocomposite, sintered at 1500°C, was found to be 97.2% while that of alumina was 99.2%. Moreover, a 160% refinement in microstructure, a 81% increase in fracture toughness, and a 25% increase in hardness were reported for the Al2O3–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite, compared to alumina. However, 11% decrease in elastic modulus was recorded for the Al2O3–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite. Interfacial and thermal analysis suggested the formation of intermediate phase (Al2OC) at Al2O3/CNTs interface in the nanocomposite. The Al2O3–SiC–CNT nanocomposite showed good thermal stability up to 760°C in inert atmosphere and up to 425°C in oxygen-rich environment. In another study, Ahmad et al. [61] used high frequency induction heat sintering (HFIHS) method to consolidate alumina nanocomposite reinforced with SiC nanoparticles (SiCnp) and CNTs (Al2O3–5wt.%SiCnp–2wt.%CNTs) at 1600°C. Fourfold reduction in grain size along with 110% increase in fracture toughness and 30% increase in hardness were reported for the nanocomposite, compared to alumina. However, the elastic modulus of alumina decreased from 418MPa to 350MPa for the Al2O3–5SiCnp–2CNTs nanocomposite. Enhancements in mechanical properties and cutting performance of alumina–matrix nanocomposite reinforced with silicon carbide whiskers (SiCw) and CNTs were reported by Lee and Yoon [62]. They prepared Al2O3–25wt.%SiCw–(0.1–1)wt.%CNTs nanocomposites using hot pressing at 1750°C. All the Al2O3–SiCw–CNTs nanocomposites showed relative density higher than 99%. Improvements in fracture toughness and flexural strength of more than 60% were reported for all Al2O3–SiCw–CNTs nanocomposites, compared to Al2O3–CNTs. The cutting performance of Al2O3–SiCw–CNTs nanocomposites was evaluated by finish turning of Inconel 718 super alloy. Fig. 9[62] shows the crater wear and flank wear performance of various Al2O3–SiCw–CNTs nanocomposites. All Al2O3–SiCw–CNTs nanocomposites showed lower wear rate compared to Al2O3–25wt.%SiCw, with Al2O3–25wt.%SiCw–0.5wt.%CNTs nanocomposite showing the lowest wear rate.

(a) Crater wear and (b) flank wear performance for various Al2O3–SiCw–CNT nanocomposites as a function of time [62]. (AS25C00 represents Al2O3–25wt.%SiCw, AS25C01:Al2O3–25wt.%SiCw–0.1wt.%CNT, AS25C05: Al2O3–25wt.%SiCw–0.5wt.%CNT, AS25C10: Al2O3–25wt.%SiCw–1wt.%CNT nanocomposite).

Al2O3ZrO2MWCNTs nanocomposites were prepared through colloidal processing and freeze drying, followed by hot pressing at 1500°C [44]. Increase in fracture toughness was observed for all nanocomposites, with a maximum of 35% for Al2O3–5vol.%ZrO2–1vol.%MWCNTs. However, around 21% decrease in hardness was reported for all Al2O3–5vol.%ZrO2–(0.5–2)vol.%MWCNTs nanocomposites. The electrical conductivity increased for all composites with a maximum value of 0.22S/m for Al2O3–5%ZrO2–2%MWCNTs as compared to 10−12S/m for alumina. In another work, a slight increase in thermal conductivity, from 29W/mK for Al2O3 to 30W/mK for Al2O3–5%ZrO2–0.5%MWCNTs nanocomposite, was observed [63]. Further increase in CNTs content caused a decrease in thermal conductivity. Mechanical properties of Al2O3 hybrid nanocomposite were enhanced by addition of 8vol.% ZrO2 nanoparticles and 4vol.% MWCNTs [64]. The materials were prepared using hot-pressing at 1600°C for 60min. High relative density values of 99.7% and 98.3% were obtained for Al2O3 and the nanocomposite, respectively, and the microstructure was refined by 10 folds. The fracture toughness and hardness of monolithic alumina were increased by 116% and 12%, respectively, as a result of the addition of reinforcements. The improvements in mechanical properties were attributed to the synergistic role of nano-ZrO2 and CNTs reinforcements through grain refining and the introduction of various toughening mechanisms. Duntu et al. [65] studied the mechanical and wear properties of CNTs and graphene (GN) reinforced Al2O3–ZrO2 hybrid nanocomposites. They prepared Al2O3–4wt.%ZrO2–2wt.%CNTs and Al2O3–4wt.%ZrO2–0.5wt.%GN nanocomposite powders and hot pressed them at 1600°C and 60MPa for 1h. All samples showed a relative density of at least 99%. Grain size refinements of 77% and 37% were observed for the CNTs and GN reinforced hybrid nanocomposites. As a result, hardness and flexural strength were found to increase by 26 and 44% for CNTs-reinforced composites and by 14 and 23% for graphene-reinforced Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites. Moreover, 118 and 97% increases in fracture toughness were reported for Al2O3–4wt.%ZrO2–2wt.%CNTs and Al2O3–4wt.%ZrO2–0.5wt.%GN nanocomposites, respectively. The enhancements in mechanical properties were attributed to grain refinement, crack bridging, crack deflection, and strong interfacial bonding of reinforcements. Enhanced wear performance with a decrease in wear rate of up to 90% and 98% was also reported in CNTs and GN reinforced nanocomposites, respectively, compared to alumina. The effect of MWCNTs on zirconia-toughened-alumina (ZTA) reinforced with MgO composite was investigated by Biswas et al. [66]. The authors fabricated ZTA–0.6wt.%MgO and ZTA–0.6wt.%MgO–(0.05, 0.1wt.%)MWCNTs nanocomposites by hot-pressing at 1500°C for 30min. All nanocomposites showed relative density of 99%. XRD analysis revealed the formation of MgAl2O4 secondary phase during sintering in all nanocomposites. The addition of MWCNTs resulted in grain refinement. Hardness and elastic modulus increased with increase in MWCNTs content, reaching values of 31.25 and 341.15GPa for ZTA–MgO–0.1wt.%MWCNTs compared to 24.57 and 302.88GPa for ZTA–MgO. The fracture toughness was found to be 22% higher in the ZTA–MgO–0.05wt.%MWCNTs nanocomposite. The ZTA–MgO–0.05wt.%MWCNTs nanocomposite also showed superior wear properties, with 42% and 81% reduction in specific wear rate at room temperature and high-temperature, respectively. Moreover, 23% and 29% decrease in coefficient of friction was reported for the ZTA–MgO–0.05wt.%MWCNTs nanocomposite at room temperature and high-temperature, respectively.

Al2O3–SiC–Graphene nanocompositesAhmad et al. [67] studied the mechanical, interfacial, and thermal performance of Al2O3 reinforced with SiCnp and GN hybrid reinforcements. The alumina and Al2O3–3wt.%SiC–0.5wt.%GN nanocomposite were inductively hot-pressed at 1300–1600°C. Relative density values of 99% were obtained for all samples. Compared to alumina, the nanocomposite displayed 70% reduction in grain size, 97% increase in fracture toughness, 15% increase in hardness, and 78% higher ballistic performance. The superior ballistic performance was attributed to higher densification, finer microstructure, high hardness, and high fracture toughness. The authors performed an interfacial investigation and concluded that a carbo-thermal reduction reaction between Al2O3 and GN resulted in the formation of Al2OC phase during sintering. In another investigation, Ahmad et al. [68] reported a 160% increase in fracture toughness and a 27% increase in hardness, when alumina was reinforced with 0.5wt.%GN and 5wt.%SiC to form a hybrid nanocomposite. Both Al2O3 and Al2O3–5wt.%SiC–0.5wt.%GN nanocomposite, were prepared through inductive sintering at 1300–1600°C, and showed relative density values greater than 99%.

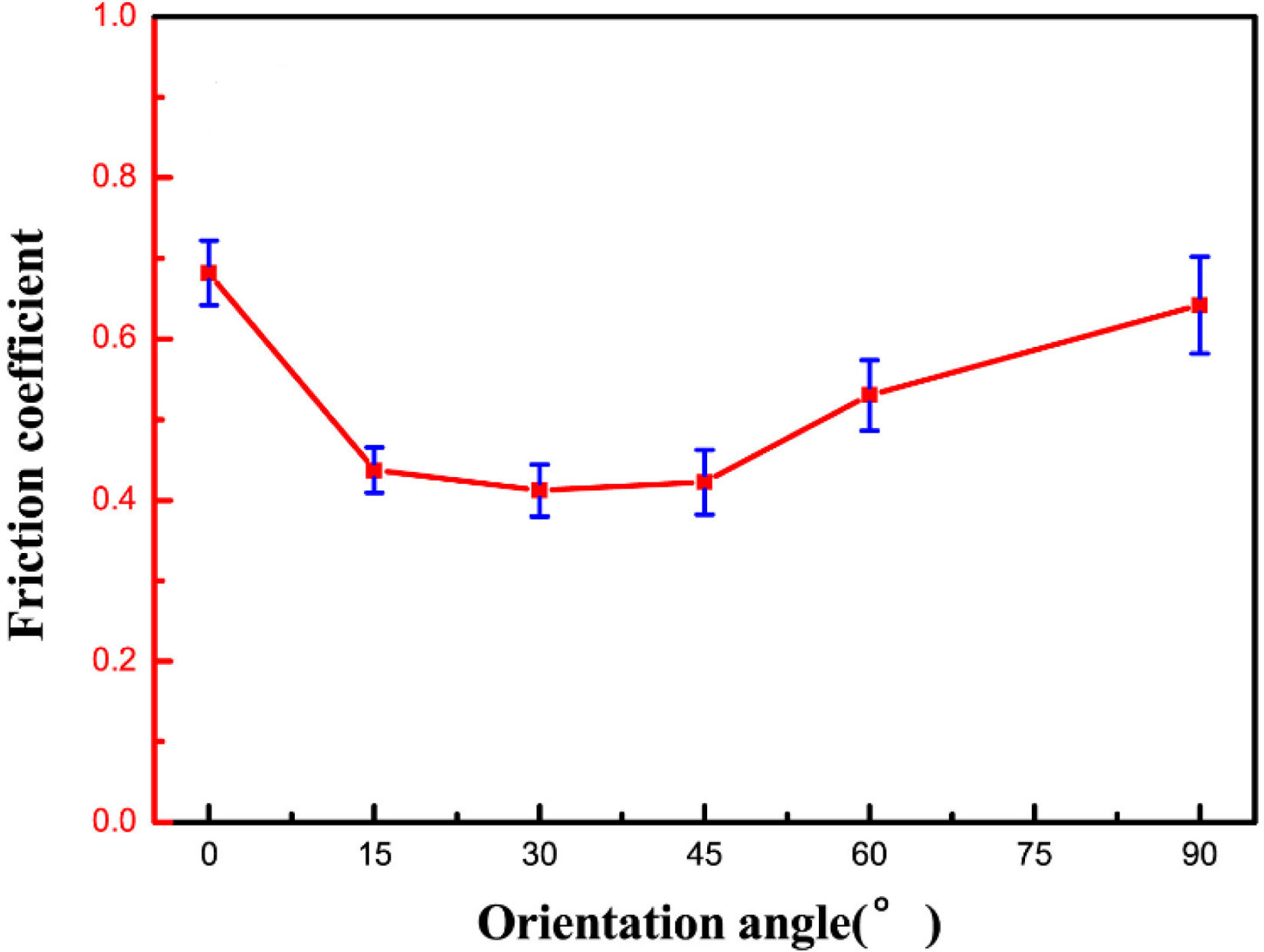

Improvements in mechanical and electrical properties of Al2O3–SiCw reinforced with graphene oxide (GO) have been reported by Grigoriev et al. [69]. They prepared Al2O3–17vol.%SiCw–(0.2–5)vol.%GO nanocomposites using colloidal processing, followed by SPS at 1780°C. Compared to Al2O3–SiCw composite, the Al2O3–SiCw–0.5wt.%GO displayed increases of 4%, 29%, and 10% in hardness, strength, and fracture toughness, respectively. The electrical resistivity was found to decrease with the increase in GO content and reached 2.2Ωcm for Al2O3–17vol.%SiCw–5vol.%GO nanocomposite. In other work, spark plasma sintered Al2O3–(1–5)vol.%SiC–0.38vol.%GPLs nanocomposites showed increased hardness, flexural strength, and fracture toughness by 36%, 40%, and 50%, compared to alumina [70]. Zhang et al. [71] prepared Al2O3–5vol.%SiC–(0.5–1)vol.%GNS nanocomposites by SPS at 1450°C. All nanocomposites had relative density values higher than 99%. The electrical conductivity of Al2O3–5vol.%SiC–1vol.%GNS nanocomposite was found to be 13 orders higher than that of alumina. The Nanocomposites showed moderate improvements in hardness and fracture toughness. The Al2O3–5vol.%SiC–1vol.%GNS nanocomposite displayed 29.4% decrease in coefficient of friction and 90.1% decrease in wear rate. The enhanced tribological properties of the hybrid nanocomposites were attributed to the formation of graphene tribofilm as sketched in Fig. 10[71], refined microstructure, and enhanced mechanical properties. Smirnov et al. [72] investigated the wear behavior of Al2O3–SiCw–GO nanocomposites. They prepared nanocomposite powder of Al2O3, 17vol.% SiCw and 0.5vol.% GO using colloidal processing and sintered it by SPS at 1780°C. The authors also prepared Al2O3–17vol.% SiC composite at same conditions for comparison. The Al2O3–SiCw–GO nanocomposite displayed better tribological performance than Al2O3–SiCw. At 10N load, Al2O3–SiCw–GO nanocomposite showed 20 and 45% decrease in the coefficient of friction and wear rate, respectively, compared to Al2O3–SiCw. And at 40N load, the coefficient of friction and wear rate further decreased to 30 and 55%, respectively. The decrease in the wear rate and coefficient of friction was attributed to the formation of a tribofilm in Al2O3–SiCw–GO nanocomposite. Shah et al. [73] produced alumina reinforced with multilayer graphene (MLG) and SiC composites. Al2O3–0.4wt.%MLG–(5, 10, 15wt.%)SiC nanocomposites were prepared by SPS at 1500°C and 21MPa for 3min. The authors investigated the effect of SiC content on the mechanical and thermal properties of the nanocomposites. They found that the densification decreased with the increase in the SiC content, however, all samples showed relative density values higher than 97%. The Al2O3–0.4wt.%MLG–5wt.%SiC nanocomposite displayed the highest mechanical properties where the bending strength and hardness increased by 57% and 19.22% compared to Al2O3. The enhancements were attributed to matrix grain refinement, homogeneous microstructure, toughening effects of the reinforcements, and change in fracture mode. The thermal conductivity and diffusivity of alumina were found to be 25.5W/mK and 8.1mm2/s at 50°C, respectively, which decreased with increase in the SiC content as well as with the increase in temperature, as shown in Fig. 11[73].

Schematic of the wear behaviour of alumina (a), and alumina–SiC–GNSs composites [71].

(a) Thermal conductivity and (b) thermal diffusivity of Al2O3–0.4wt.%graphene–(0, 5, 10, 15wt.%)SiC hybrid nanocomposites [73].

Microstructural, mechanical, and ballistic properties of GNPs and ZrO2 reinforced-alumina hybrid nanocomposites were investigated by Ahmad et al. [74]. The authors produced Al2O3 and Al2O3–4wt.%ZrO2–0.5wt.%GNPs nanocomposite by hot-pressing at 1600°C. Compared with alumina, the nanocomposite displayed: (i) slight decrease in relative density from 99.7 to 98.5%, (ii) 68% decrease in grain size, (iii) 155% increase in fracture toughness, (iv) 17% increase in hardness, and (v) 88% increase in ballistic properties. These enhancements were attributed to grain refinement as well as toughening mechanisms induced by the reinforcements. Microstructural analysis showed wrapping and anchoring of graphene around alumina grains, resulting in very good interfacial strength. Petrus et al. [75] reported mechanical and tribological properties of GML and GO reinforced Al2O3–ZrO2 nanocomposites where 0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.7 and 1wt.%MLG and nikel-coated-graphene were added to Al2O3–ZrO2. The samples were consolidated by SPS at 1550°C for 4min. All nanocomposites had relative density values larger than 98%. The Al2O3–ZrO2–0.2wt.%GO nanocomposite displayed highest hardness and fracture toughness values of 1940HV and 5.5MPam1/2, compared to 1840HV and 5.2MPam1/2 for Al2O3–ZrO2. Also, all graphene-reinforced nanocomposites showed higher coefficient of friction and higher wear rate (at a load of 10N), compared to Al2O3–ZrO2.

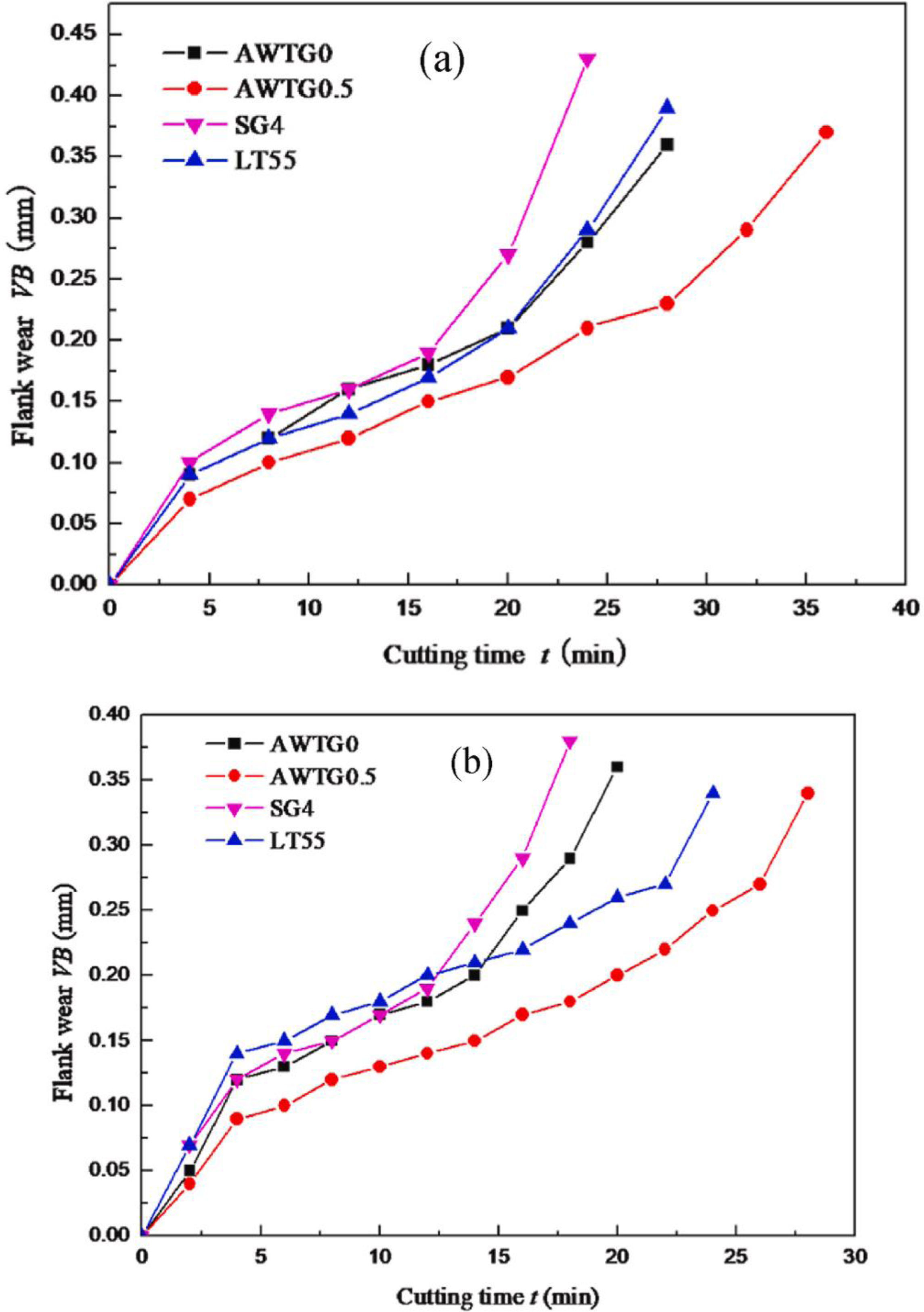

Al2O3–WC–TiC–graphene nanocompositeWang et al. [76] reported improvements in fracture toughness of Al2O3–WC–TiC ceramic tool material due to the addition of single layer graphene (SLG). Al2O3–18vol.%WC–6vol.%TiC was reinforced with 0.5–2vol.%SLG and hot pressed at 1700°C. Increase in densification and enhancements in mechanical properties were observed with the addition of 0.5vol.% SLG, beyond which properties began to decrease. Densification, flexural strength, hardness, and fracture toughness values of 99.58%, 646MPa, 24.64GPa, and 9.42MPam1/2, respectively, were obtained for Al2O3–WC–TiC–0.25vol.%SLG nanocomposite, compared to values of 98.94%, 550MPa, 23.54GPa, and 8.76MPam1/2 for Al2O3–WC–TiC. The enhancements in properties were attributed to rugged graphene surface, grain refinement during densification, and crack bridging and deflection. In another work, Wang et al. [77] reported superior cutting and wear performance of Al2O3–WC–TiC–0.5vol.%Graphene nanocomposite while machining hardened 40Cr steel, in comparison with Al2O3–WC–TiC and other commercial tool materials including Al2O3–(W, Ti)C and Al2O3–TiC, as shown in Fig. 12[77]. Cutting force and cutting temperature were found to be lower in graphene reinforced Al2O3–WC–TiC tool. Moreover, reinforcement with graphene (thickness: ∼0.8nm, lateral size: 0.5–5μm) resulted in reduction in coefficient of friction from 0.33 for Al2O3–WC–TiC to 0.1 for Al2O3–WC–TiC–0.5vol.% Graphene nanocomposite. The superior properties of graphene-reinforced nanocomposite were attributed to; increased mechanical properties due to graphene reinforcement, good lubrication properties and higher thermal conductivity which resulted in friction reduction and decrease in cutting temperatures. Wang et al. [78], in another work, studied the mechanical properties and interfacial structure of Al2O3–WC–TiC–Graphene nanocomposite. They used graphene with a thickness of ∼0.8nm and lateral size of 0.5–5μm. Al2O3–WC–TiC composite and Al2O3–WC–TiC–0.5vol.% Graphene nanocomposite, with constant 18vol.% WC and 6vol.% TiC, were hot-pressed in two steps, first heated to 1750°C and without dwell time cooled to 1600°C for dwell period of 15min. Apart from parent phases, (W, Ti)C solid solution was formed in sintered samples. Al2O3–WC–TiC composite and Al2O3–WC–TiC–0.5vol.% Graphene showed relative density values of 98.41% and 99.52%, respectively. Hardness, flexural strength and fracture toughness were found to be 22.5GPa, 860MPa, and 9MPam1/2 for Al2O3–WC–TiC–Graphene nanocomposite; compared to 19GPa, 500MPa, and 6MPam1/2 for Al2O3–WC–TiC, respectively. A TEM analysis showed three type of interfaces; Al2O3–graphene, graphene–Al2OC, and graphene–WC interface. On basis of calculated adhesion energy and interfacial strengths, the authors ranked the interfaces; Al2O3–graphene>graphene–WC>graphene–Al2OC. Effects of different thickness and lateral sizes of graphene reinforcement on Al2O3–WC–TiC nanocomposites were reported by Wang et al. [79]. Al2O3–18vol.%WC–6vol.%TiC composite and Al2O3–18vol.%WC–6vol.%TiC–0.5vol.%graphene nanocomposites, with different types of graphene, were hot-pressed at 1700°C for 10min. A relative density of 98.4% was reported for Al2O3–WC–TiC while other nanocomposites showed values greater than 99%. Compared to Al2O3–WC–TiC, the Al2O3–WC–TiC–graphene nanocomposite with SLG displayed increased hardness, flexural strength, and fracture toughness by 14.80%, 67.59%, and 54.10%, respectively. Moreover, the authors concluded that graphene thickness and lateral size has no effect on matrix grain size and hardness. However, thinner graphene with larger lateral area was found beneficial to improve densification, flexural strength, and fracture toughness. Cheng et al. [80] investigated the effect of varying GNPs content on mechanical and microstructural properties of Al2O3–TiC–GNPs nanocomposite ceramic tool material. 60wt.%Al2O3, 30wt.%TiC, 0.2–0.8wt.%GNPs along with 10wt.%sintering aids (Mo, Ni, MgO, Y2O3) were used for composite preparation. The samples were consolidated by microwave sintering at 1700°C for 10min. The densification of sintered samples decreased with the increase in GNPs content. As compared to Al2O3–TiC composite, the fracture toughness of Al2O3–30wt.%TiC–0.2wt.%GNPs increased by 67.3% while the hardness decreased by 12.7%. Similar investigation was made by Cui et al. [81], where (0.2–0.8wt.%) GNP was used for toughness enhancement in Al2O3–(W, Ti)C ceramic tool material. Maximum improvements were reported for 0.2wt.%GNP reinforced Al2O3–(W, Ti)C nanocomposite, with 35.3% increase in fracture strength and 49% increase in flexural strength, as compared to Al2O3–(W, Ti)C without graphene. The enhancements were attributed to break of GNPs and crack guiding along with other conventional toughening mechanisms. Improvements in fracture toughness and flexural strength of multi-layer graphene (MLG) reinforced Al2O3–TiC nanocomposite tool material were reported by Li et al. [82]. The authors hot pressed 65.4wt.%Al2O3 and 33.2–33.7wt.%TiC reinforced with 0.1–0.5wt.%MLG nanocomposites at 1650°C. Fracture toughness and flexural strength values of 6.14MPam1/2 and 981.5MPa were obtained for Al2O3–TiC–0.2wt.%MLG nanocomposite, which are 23.2% and 30.9% higher, respectively, than those of the Al2O3–TiC composite without MLG reinforcement. Zhao et al. [83] investigated the effect of varying the content of WC microparticles and TiC nanoparticles on the properties of Al2O3–TiC–WC ceramic tool material. They prepared Al2O3–(21–36)vol.%TiC–(14–4)vol.%WC nanocomposites by hot pressing at 1700°C for 10min and found that the Al2O3–24vol.%TiC–16vol.%WC nanocomposite show optimal mechanical properties with flexural strength of 842MPa, fracture toughness of 6.82MPam1/2, and hardness of 22.19GPa.

Wear behavior of different tool materials Al2O3–WC–TiC (AWTG0), Al2O3–WC–TiC–0.5vol.%Graphene (AWTG0.5), Al2O3–(W, Ti)C (SG4) and Al2O3–TiC (LT55) in machining hardened 40Cr steel at; (a) 100m/min. (b) 150m/min [77].

Synergistic effects of 1wt.%CNTs and 0.5wt.%graphene nanoplatelets (GNP) on alumina have been investigated by Rahman et al. [84]. The authors used spray drying for powder preparation and sintered the samples by SPS at 1500°C. They reported an increase in relative density from 91% to 99.9%, a 44% decrease in grain size, and a 20% decrease in hardness for Al2O3–1wt.%CNT–0.5wt.%GNP nanocomposite compared to alumina. The interfacial shear stress for Al2O3–1wt.%CNT–0.5wt.%GNP nanocomposite was found to be 28 times higher than that of Al2O3–1wt.%CNT. Improvements by 29% and 250% in the elastic modulus and fracture toughness, respectively, were reported for Al2O3–1wt.%CNT–0.5wt.%GNP nanocomposite compared to alumina. The significant enhancement in toughness was linked not just to conventional toughening mechanisms like CNT pullout, grain gluing, bridging, graphene pullout, bending, sliding, and grain wrapping, illustrated in Figs. 13 and 14[84], but also to other toughening mechanisms such as CNT yarning and CNT-embedded graphene, as depicted in Fig. 15[84]. Furthermore, the high interfacial shear stress could have played a role in the toughness improvement [84]. Damavandi et al. [85] examined the effect of different powder preparation processes and varying content of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and CNTs on mechanical and microstructural properties of alumina nanocomposites. Al2O3–(0.5–2)wt.%rGO–(0.5–4)wt.% CNT nanocomposites were prepared using two different powder mixing techniques i.e. wet mixing and sol–gel mixing, followed by hot pressing at 1650°C. All the nanocomposites showed relative density values higher than 98%. The nanocomposites prepared using sol–gel process displayed superior properties i.e. 13, 70, and 14% improvements in hardness, fracture toughness, and flexural strength for Al2O3–1wt.%rGO–1wt.%CNT compared to alumina. The Al2O3–1wt.%rGO–1wt.%CNT nanocomposite prepared by sol–gel showed 62% reduction in grain size, 13% increase in hardness, 14% increase in fracture toughness, and 13% increase in flexural strength, compared to the same nanocomposite prepared through wet-mixing. Effect of changing the sintering route on microstructural and mechanical properties of Al2O3–GNP–CNT nanocomposites was studied by Yazdani et al. et al. [86]. Al2O3–(0.5–1)wt.%GNP–(0.5–2)wt.%CNT nanocomposites were prepared at 1650°C using hot pressing for 1 hour and SPSfor 10min. All nanocomposites had relative density values greater than 98%. Samples prepared using HP showed finer microstructure with homogenous grain distribution, than those prepared through SPS. Consequently, hardness and flexural strength of hot-pressed samples were larger than those of samples prepared by SPS. Highest values of flexural strength and hardness, in both cases, were reported to be >400MPa and 5.5MPam1/2, respectively. The Al2O3–0.5wt.%GNP–0.5wt.%CNT nanocomposite, prepared by SPS, showed highest mechanical properties. While for the hot-pressed samples, the Al2O3–0.5wt.%GNP–1wt.%CNT nanocomposite displayed highest mechanical properties. A 63% increase in fracture toughness and a 12% increase in flexural strength were observed [87], compared to alumina. In another investigation, Yazdani et al. [88] reported tribological properties of hot pressed Al2O3–GNP–CNT hybrid nanocomposites, under various loading conditions, using ball-on-disk wear test configuration. The Al2O3–0.3wt.%GNP–1wt.%CNT nanocomposite showed 20% reduction in coefficient of friction and 74% reduction in wear rate, compared to alumina. The enhanced tribological properties of the nanocomposite were attributed to the formation of a tribofilm as well as superior mechanical properties due to CNT and GNP reinforcements.

(a) CNT-grain gluing and (b) CNT-grain bridging or anchoring in the composite [64].

(a) graphene sliding and bending between Al2O3 grains and (b) graphene-grain wrapping [84].

(a) CNT yarn in Al2O3–1wt.% CNT and (b) CNT implanted graphene in Al2O3–1wt.% CNT–0.5 wt% GNP sintered nanocomposites [84].

Shah et al. [89] prepared Al2O3 and Al2O3–1wt.%CNT–(0.4, 0.8wt.%) graphene nanocomposites by SPSat 1500°C and 21MPa for 3min. All sintered samples had relative density values greater than 99%. The authors reported 49.5% increase in the fracture toughness of Al2O3–1wt.%CNT–0.4wt.%graphene nanocomposite, compared to alumina. The Al2O3–1wt.%CNT–0.4wt.%graphene nanocomposite and alumina had flexural strength values of 494 and 415MPa, respectively. The thermal properties decreased with the increase in reinforcement content. At 50°C, thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of Al2O3 were found to be 23.25W/mK and 7.56mm2/s, respectively, which decreased to values of 16W/mK and 5.5mm2/s for Al2O3–1wt.%CNT–0.8wt.%graphene nanocomposite. Duntu et al. [90] investigated the fracture behavior of graphene and/or CNT reinforced Al2O3–ZrO2 hybrid nanocomposites. Al2O3–10wt.%ZrO2 was reinforced with 0.5wt.%graphene and 2wt.%CNTs, and the nanocomposite powders were hot pressed at 1600°C for 1h. Addition of 10wt.%ZrO2 and 0.5wt.%graphene to Al2O3 resulted in 56% increase in fracture toughness. Similarly, Al2O3–10wt.%ZrO2–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite showed fracture toughness and bending strength values of 7.55MPam1/2 and 460MPa, compared to 3.4MPam1/2 and 259MPa for Al2O3. Highest increases of 159% in fracture toughness and 86% in bending strength were observed when 2wt.%CNTs and 0.5wt.%graphene were added to Al2O3–10wt.%ZrO2. In another work, Duntu et al. [91] studied the wear behavior of Al2O3–ZrO2–graphene/CNT hybrid nanocomposites. Al2O3–ZrO2–0.5wt.%GN showed 2% increase in hardness and 91% increase in wear resistance compared to alumina. Similarly, the hardness and fracture toughness of Al2O3–ZrO2–2wt.%CNT increased by 11 and 92%, while those of Al2O3–ZrO2–0.5wt.%GN–2wt.%CNT increased by 48 and 93%.

Other Al2O3 nanocompositesThe effect TiC and Ni on alumina was investigated by Rodrigues Suarez et al. [92]. They produced Al2O3–25vol.%TiC–1.9vol.%Ni nanocomposite by SPS at 1375°C. Improvements of 30% and 75% in hardness and flexural strength, respectively, were reported for Al2O3–TiC–Ni nanocomposite, compared to alumina, while no significant change in fracture toughness was observed. A very low value of electrical resistivity (very high electrical conductivity) of 3.15×10−5Ωm was reported for the Al2O3–TiC–Ni nanocomposite. Moreover, the wear rate of Al2O3–TiC–Ni nanocomposite was found to be 25 times lower than alumina. In other work [73], no significant change in fracture toughness was observed when Al2O3 was reinforced with 10vol.% niobium and 5vol.% single wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) [93]. SPS sintering at 1200°C resulted in 98.4% densification, fracture toughness of 3.3MPam1/2, and hardness of 19.3GPa for Al2O3–5vol.%SWCNT–10vol.%Nb nanocomposite. The authors proposed that the damage to SWCNTs during sintering and the non-optimal interfacial bond at the SWCNT–alumina interface were reasons for not observing improvements in fracture toughness. Effects of varying TiC content (2–6vol.%) and particle size (40–500nm) on mechanical and microstructural properties of Al2O3–20vol.%SiC–TiC nanocomposites were investigated by Zhao and co-authors [94]. Increase in hardness, fracture toughness, and flexural strength were observed with the increase in TiC content up to 4vol.%, beyond which the properties decreased. Varying particle size was found to affect only flexural strength, while hardness and fracture toughness remained unaffected. Optimized properties were obtained at 40nm particle size and 4vol.% TiC content for the Al2O3–20vol.%SiC–4vol.%TiC nanocomposite. In another work, Zhao and co-authors [95] used the same optimized Al2O3–20vol.%SiC–4vol.%TiC nanocomposite and studied its mechanical properties at elevated temperatures up to 1200°C in comparison with Al2O3–20vol.%SiC composite. Hardness and fracture toughness of the Al2O3–SiC–TiC nanocomposite at all temperatures were higher than those of the Al2O3–SiC composite. The Al2O3–SiC–TiC nanocomposite showed low high temperature flexural strength, in contrast with high flexural strength at room temperature, compared to Al2O3–SiC composite. The low high-temperature flexural strength was attributed to change in fracture mode to intergranular at elevated temperatures. Both hardness and flexural strength decreased with the increase in temperature. At 1000°C, the Al2O3–SiC–TiC nanocomposite maintained 68.4% of its room temperature hardness. At 1100°C, the flexural strength of the Al2O3–SiC–TiC nanocomposite was maintained at 60% of the room temperature value. The elastic modulus of both Al2O3–SiC and Al2O3–SiC–TiC nanocomposites remain unchanged up to 1000°C and begin to decrease at 1100°C. Sun et al. [96] studied the properties of Al2O3-based tool materials reinforced with nano-TiC and graphene. They prepared Al2O3–(0–30vol.%)TiC–(0–0.75vol.%)Graphene nanocomposites using hot pressing at 1650°C for 10min. They used 10vol.% nano-Al2O3, 0.5vol.% MgO, and Y2O3 as sintering aid and 0.5vol.% Ni and Mo as metal binders. The optimum composition was found to be Al2O3–10vol.%TiC–0.5vol.%Graphene giving flexural strength of 705MPa, fracture toughness of 7.4MPam1/2, and hardness of 20.5GPa. The enhancement in toughness was attributed to the toughening mechanisms induced by both reinforcements. Mechanical and tribological properties of graphene-reinforced Al2O3–Ti(C,N) nanocomposites have been reported by Petrus et al. [75]. They used 0, 0.2, 0.5, 0.7 and 1wt.%graphene in form of multilayer graphene (MLG), graphene oxide (GO), and nikel-coated-graphene to produce Al2O3–Ti(C,N) hybrid nanocomposites by SPSat 1550°C for 4min. All nanocomposites showed relative density values between 95 and 98%. The Al2O3–Ti(C,N)–0.2wt.%GO nanocomposite showed slightly higher hardness value of 2025HV compared to 1950HV for Al2O3–Ti(C,N) composite. A decrease in fracture toughness was reported for the graphene-reinforced Al2O3–Ti(C,N) nanocomposites. However, the Al2O3–Ti(C,N)–0.2wt.%GO nanocomposite showed 800% lower wear rate, compared to Al2O3–Ti(C,N) composite. Sun et al. [97] reported the properties of Al2O3–TiC–GNP–MWCNTs prepared by addition of 0.2–0.8wt.%MWCNT and 0.2–0.7wt.%GNP to Al2O3–TiC. The composites were spark plasma sintered at 1600°C for 5min. The Al2O3–TiC reinforced with 0.8wt.%MWCNTs and 0.2wt.%GNP nanocomposite showed the best properties with relative density of 97.3%, hardness of 18.38%, and fracture toughness of 9.40MPam1/2. Toughening mechanisms like crack bridging and branching, crack deflection and drawing by CNT and GNP reinforcements were mainly responsible for the enhanced toughness. Chen et al. [98] investigated the effect of sintering parameter and graphene content on mechanical properties of Al2O3–TiB2 nanocomposites. Al2O3 was reinforced with 20wt.%TiB2 and varying GNP content (0.1–0.6wt.%), and 0.5wt.%MgO and 0.5wt.%Y2O3 were used as sintering aids. The authors sintered Al2O3–TiB2 samples by SPS at varying temperatures and times to find the optimum conditions. They found that 1525°C and 5min give the optimum mechanical properties and sintered the graphene-reinforced nanocomposites at the same conditions. All nanocomposites showed relative density greater than 98%. The Al2O3–TiB2 reinforced with 0.3wt.%GNP showed optimum mechanical properties with 6.4% increase in flexural strength and 46.1% increase in fracture toughness compared to Al2O3–TiB2 composite. Nevertheless, a 5.2% decrease in hardness was observed.

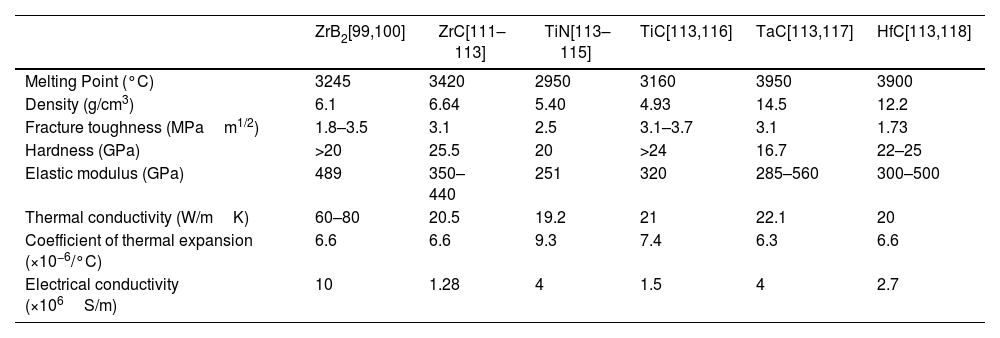

ZrB2 nanocompositesZirconium diboride (ZrB2) belongs to the class of advanced materials known as ultrahigh temperature ceramics (UHTC) [99], which are applied in extreme environments as electrodes for electric discharge machining, crucibles in the metal industry, and structural and functional parts in the aerospace industry [99,100]. Among various UHTC materials, ZrB2 is the most widely investigated and applied ceramic material because of its very high melting temperature, relatively low density and cost, chemical inertness, high temperature stability and strength, acceptable thermal and electrical conductivity [99]. Typical properties of ZrB2 are listed in Table 1. However, despite such an excellent combination of properties, there are certain challenges that limit the use of ZrB2 ceramic such as brittleness and difficulty to sinter. While the use of hot pressing (HP) and SPS improved the sinterability of ZrB2, the improvement of its fracture toughness was possible by introducing a single reinforcement such as SiC [101–103], CNTs [104,105], and graphene [105,106], resulting in the formation of nanocomposites [99]. It was also reported that introducing reinforcements in ZrB2 ceramic facilitated densification, and contributed to the improvement of fracture toughness and resistance to oxidation [107,108]. Moreover, it was found that further enhancements in fracture toughness were possible through the incorporation of two distinct reinforcements in the ZrB2 matrix [109,110], forming hybrid nanocomposites.

Properties of some ultrahigh temperature ceramics.

| ZrB2[99,100] | ZrC[111–113] | TiN[113–115] | TiC[113,116] | TaC[113,117] | HfC[113,118] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point (°C) | 3245 | 3420 | 2950 | 3160 | 3950 | 3900 |

| Density (g/cm3) | 6.1 | 6.64 | 5.40 | 4.93 | 14.5 | 12.2 |

| Fracture toughness (MPam1/2) | 1.8–3.5 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 3.1–3.7 | 3.1 | 1.73 |

| Hardness (GPa) | >20 | 25.5 | 20 | >24 | 16.7 | 22–25 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 489 | 350–440 | 251 | 320 | 285–560 | 300–500 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/mK) | 60–80 | 20.5 | 19.2 | 21 | 22.1 | 20 |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion (×10−6/°C) | 6.6 | 6.6 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 6.3 | 6.6 |

| Electrical conductivity (×106S/m) | 10 | 1.28 | 4 | 1.5 | 4 | 2.7 |

Asl and co-authors [119] investigated the effect of SPS parameters and nano-graphite flakes (Gnf) content on the densification of ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–(5, 10wt.%)Gnf nanocomposites. The authors used Taguchi design of experiments approach to set the experimental conditions. They observed that, among all parameters, sintering temperature and Gnf content had the most influential effect on the relative density. The ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–5wt.%Gnf nanocomposite sintered at 1900°C and 40MPa for 4min had a relative density of 99.5%. Microstructural analysis of the fully dense sample showed the formation of ZrC/B4C clusters at ZrB2/Gnf interface. The addition of Gnf helped in the removal of oxide film from ZrB2 surface as well as formation of ZrC/B4C within the grain boundaries, both of which have contributed toward increased sinterability of the nanocomposite. In another work, Asl et al. [120] investigated the interfacial behavior of spark plasma sintered ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%GNPs nanocomposite. Full densification was achieved using SPS conditions of 1800°C and 6min. Analysis of TEM nanographs of ZrB2/SiC and ZrB2/ZrB2 interfaces did not reveal the presence of ZrC or B4C compounds. Because of these clean interfaces, it was concluded that GNPs acted as sintering aids, by facilitating diffusion-induced joining of particles. Other researchers [107] reported the densification and mechanical behavior of GNSs reinforced ZrB2–SiC nanocomposites, prepared by in situ thermal reduction of graphene oxide during hot-pressing. Formation of GNSs was confirmed by Raman spectroscopy. The relative density of the ZrB2–SiC composite (98.2%) increased to 98.9% and 99.2% for the ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–2vol.%GNSs and ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–5vol.%GNSs nanocomposites, respectively. The fracture toughness and flexural strength increased with the increase in the content of GNSs, and reached 7.32MPam1/2 and 1055MPa for the ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–5vol.%GNSs nanocomposite, which are 73.8% and 100% higher than those of ZrB2–SiC. However, slight decrease in hardness was observed, from 23.07GPa for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC composite to 22.76GPa for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–5vol.%GNSs. Asl et al. [110] investigated the effect of the addition of Gnf (0–10wt.%) on the properties of spark plasma sintered ZrB2–25vol.%SiC composites. A relative densification more than 98% was reported for all samples. The ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–5wt.%Gnf nanocomposite showed uncommon relative density of 100.7% which was attributed to the in-situ formation of ZrC phase. The hardness of ZrB2–25vol.%SiC composite decreased from 19.5 to 12.1GPa for ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–10wt.%Gnf. However, fracture toughness increased with the increase in graphite content and reached a value of 8.2MPam1/2 for ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–7.5wt.%Gnf, which is twice the value of ZrB2–25vol.%SiC. The increase in fracture toughness was attributed to toughening effect of the reinforcements, microstructure refinement, and in-situ formation of ZrC and B4C compounds. In another work, Asl et al. [121] reported an increase in relative density from 90.1% to 99.6%, with the addition of 20vol.%SiC and 10vol.% Gnf to ZrB2. Also, the hardness and fracture toughness of ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Gnf nanocomposite increased by 38 and 294%, respectively, compared to ZrB2. In a similar work, Asl et al. [122] reported 30% increase in hardness and more than 250% increase in fracture toughness of hot-pressed ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–5wt.%GNPs nanocomposite, compared to ZrB2. The effect of varying the content of Gnf on microstructural and mechanical properties of ZrB2–SiCw–Gnf nanocomposites has been investigated by Asl et al. [123]. ZrB2–SiCw–Gnf nanocomposites were prepared by reinforcing ZrB2 with 25vol.%SiCw and 0–7.5wt.% Gnf. The samples were sintered using SPS at 1900°C for 7min. A relative densification of more than 99.9% was observed for all samples significant grain refinement was observed with the increase in graphite content. The obtained hardness and fracture toughness of ZrB2–SiCw–Gnf nanocomposites are shown in Fig. 16. A 10% decrease in hardness and 32% increase in fracture toughness were reported for ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–7.5wt.%Gnf and ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–5wt.%Gnf nanocomposites, respectively, compared to ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw. Enhancements in fracture toughness of ZrB2 because of the addition of 0–7.5wt.% GNPs and 25vol.% SiCw were reported by Xia et al. [124]. The ZrB2–GNPs–SiCw hybrid nanocomposites were sintered by SPS at 1900°C for 7min. All nanocomposites showed relative density values higher than 99.75%. Microstructural analysis showed grain growth inhibition in the hybrid nanocomposites by GNPs. The average grain size of ZrB2 in ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw composite decreased from 5.2 to 3.1μm for ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–7.5wt.%GNPs nanocomposite. A slight increase in hardness, from 22 to 22.2GPa was observed because of the inclusion of 2.5wt.%GNPs in ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw nanocomposite. However, 30% increase in fracture toughness was reported for ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–7.5wt.%GNPs nanocomposite. A ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–Graphite nanocomposite was prepared by sol gel process and spark plasma sintered at 1950°C for 10min [125]. Microstructural analysis of the sintered sample showed uniform distribution of SiC, along with the presence of graphite nanosheets. Flexural strength and fracture toughness of the ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–Graphite nanosheets composite was found to be 318MPa and 3.09MPam1/2, respectively. Parvizi et al. [126] studied the synergistic effect of graphite nano-flakes (Gnf) and SiC reinforcements on properties of spark plasma sintered ZrB2. The relative density of ZrB2 increased from 96.1 to 100.7% for ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–5wt.%Gnf. Hardness, fracture toughness, and flexural strength of 13.1GPa, 3.2MPam1/2, and of 445MPa for ZrB2 increased to 16.6GPa, 6.7MPam1/2, and 631MPa for ZrB2–25vol.%SiC–5wt.%Gnf nanocomposite, respectively. The effect of varying diameter of graphite reinforcement on mechanical and thermal shock properties of ZrB2–20vol.%nano-SiC–20vol.%Graphite nanocomposites was investigated by Hou et al. [127]. ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–20vol.%Graphite nanocomposites, with different graphite diameters of 5, 10 and 20μm, were hot pressed at 1900°C. Relative density of more than 98% was observed for all samples. ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–20vol.%Graphite nanocomposites with 10μm diameter graphite showed the highest flexural strength of 523MPa, fracture toughness of 4.54MPam1/2, and Young's modulus of 356GPa. The nanocomposite with smallest graphite diameter showed better thermal shock resistance. Nguyen et al. [128] investigated sintering behavior and microstructure of ZrB2 reinforced with 25vol.%SiCw whiskers and 5wt.%GNPs. Fully dense ZrB2–SiCw–GNPs nanocomposite was prepared using SPS at 1900°C. XRD analysis showed no new phase formation during sintering. Microstructural analysis revealed ultra-thin amorphous layer at ZrB2–GNPs interface and dislocation in ZrB2.

(a) Hardness and (b) fracture toughness of ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–Gnf nanocomposites as a function of Gnf[123].

Tian and co-authors investigated the effect of CNTs on densification, mechanical and thermal properties of hot-pressed ZrB2–SiC [129]. Slight decrease in densification, hardness (6%) and thermal conductivity (4%) were observed for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite compared to ZrB2–20vol.%SiC. But, the same composite showed 15% increase in fracture toughness and 6% increase in flexural strength. In other work [130], hot-pressed ZrB2 reinforced with 20vol.%SiC and 10vol.%MWCNTs displayed better properties compared to ZrB2. The relative density of ZrB2 increased from 90.1% to 93.9% for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs nanocomposite. The reinforcements also contributed to inhibiting the grain growth during sintering. A 180% increase in fracture toughness while 30% decrease in hardness were reported for the ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs nanocomposite compared to ZrB2. Nisar et al. [131] reported enhancements in the properties of ZrB2 ceramic composite, produced by SPS, through the synergistic reinforcement of SiC and CNTs. The relative density increased from 93.1 (ZrB2) to 99.7 (ZrB2–20vol.% SiC–10vol.% CNTs), while the fracture toughness and flexural strength were 3 and 1.6 times higher, respectively. In other work, Nisar et al. [132] observed significant improvements in densification, mechanical properties and thermal performance of spark plasma sintered ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs nanocomposite. The relative density of ZrB2 increased from 93.1 to 99.7% for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs. To study the oxidation behavior, samples were exposed to plasma arc-jet with heat flux of 2.5 MW/m2 for 30seconds. After the oxidation test, 42% ZrB2 phase retention along with lower oxidation rate of 0.44μm/s were observed for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs, compared to 30% and 0.77μm/s for ZrB2, respectively. The thickness of oxide layer was 10μm for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs, showing more oxidation resistance, compared to 23μm for ZrB2. Compared to ZrB2, higher hardness was reported for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs nanocomposite in both cases; 1.6 times higher in unexposed samples and 2.1 times higher in exposed samples. The thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat of ZrB2 increased from 48.9W/mK, 0.236mm2/s, and 340.4J/kgK at 50°C to 61.8W/mK, 0.24mm2/s, and 485.2J/kgK for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs, respectively. The TGA results showed that the oxidation temperature shifted from 679.3°C for ZrB2 to 406.3°C for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%CNTs, an indication of enhanced oxidation resistance. Popov and co-authors [133] prepared ZrB2–31wt.%SiC and ZrB2–29wt.%SiC–8vol.%CNTs composites by reactive hot pressing ZrC, B4C, Si, and CNTs powders in the temperature range 1100–1830°C. The ZrB2–29wt.%SiC–8vol.%CNTs nanocomposite showed 60% improvement in fracture toughness compared to ZrB2–29wt.%SiC.

Nano-carbon reinforced ZrB2–SiC nanocompositesNano-sized carbon black (Cnb) was used to prepare a ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb nanocomposite by HP at 1850°C for 60min [134]. The sintered nanocomposite nearly reached fully density (99.8%). A pore-free microstructure and strong interfaces between ZrB2, SiC and Cnb could be observed in the TEM image of ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb nanocomposite shown in Fig. 17. XRD analysis revealed partial conversion of carbon-black to crystalline graphite, which was also confirmed by TEM. In other work, Azizian Kalandaragh et al. [109] studied the effect of varying carbon nanoparticles (Cnp) content on microstructural and mechanical properties of spark plasma sintered ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–Cnp nanocomposites. They reported a relative density higher than 99.8% for all sintered samples and observed reduction in grain growth. The hardness was found to decrease linearly from 21.9 to 14.6GPa for ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–7.5wt.%Cnp nanocomposite. However, the fracture toughness increased from 4.7MPam1/2 for ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw composites to 7.1MPam1/2 for ZrB2–25vol.%SiCw–5wt.%Cnp. Hu et al. [135] used carbon fibers (Cf) to produce ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–30vol.%Cf by HP at relatively low temperature of 1450°C. They reported a relative density of 95.8%, flexural strength of 341MPa, and fracture toughness of 6.12MPam1/2. The ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–30vol.%Cf nanocomposite displayed high work of fracture compared to other ZrB2-based composites without Cf. Nasiri et al. [136] studied the effect of varying the content of Cf (2.5–15wt.%) and SiC nanoparticles (2.5–10wt.%) on densification and mechanical properties of pressure-less sintered ZrB2–SiC–Cf nanocomposites. The relative density, hardness, and fracture toughness increased with the increase in SiC content up to 10wt.%, beyond which the properties began to decrease. However, the increase in Cf reinforcement content caused the density, hardness, and fracture toughness to decrease in ZrB2–SiC–Cf nanocomposites. The ZrB2–10vol.%SiC–2.5vol.%Cf had optimum properties with a relative density of 93%, hardness of 14.5GPa, and fracture toughness of 5.9MPam1/2. The effect of Cnb addition on microstructural and mechanical properties of ZrB2–SiC composites were reported by Farahbakhs and co-authors [137]. They hot pressed ZrB2, and ZrB2–20vol.%SiC and ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb composites at 1850°C. Relative density values of 90 and 93% were reported for ZrB2 and ZrB2–20vol.%SiC samples, which increased to 99.8% for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb sample. The authors observed refinement of the microstructure and concluded that Cnb acted as a sintering aid. The SEM analysis of the ZrB2–20vol.% SiC–10vol.% Cnb nanocomposite, presented in Fig. 18, showed the presence of some unreacted Cnb along with SiC and ZrB2, while some carbon was believed to react with the surface oxides of ZrB2, resulting in enhanced densification. Hardness and flexural strength values of 11.9GPa and 355MPa for ZrB2 increased to 16.7GPa and 687MPa, respectively, for the ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb nanocomposite. Moreover, a 180% increase in fracture toughness was observed for ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb nanocomposite compared to ZrB2 (2.1MPam1/2). Zhou et al. [138] also observed improvements in fracture toughness and thermal properties of hot-pressed ZrB2–20vol.%SiC composite because of the addition of 5vol.% Cnb. The ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–5vol.%Cnb nanocomposite had a high fracture toughness of 6.6MPam1/2. Also, the thermal shock resistance parameter of the hybrid nanocomposite was 15% higher than ZrB2–20vol.%SiC nanocomposite. Savari and co-authors [139] investigated the densification and toughness of ZrB2 reinforced with SiC (15 and 30vol.%) and Cnb(10 and 15vol.%). The nanocomposites were spark plasma sintered at 1850°C and 35MPa for 8min. The ZrB2 showed low relative density of 81%, however, nearly full density was obtained when ZrB2 was reinforced with SiC and Cnb. Significant improvements in fracture toughness were reported for single reinforcement with Cnb, but only a marginal increase of 26% was observed for hybrid reinforcement in ZrB2–30vol.%SiC–(10, 15vol.%)Cnb nanocomposites.

TEM image of ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb nanocomposite [134].

FE-SEM image of fractured surface of ZrB2–20vol.%SiC–10vol.%Cnb nanocomposite showing unreacted nano-carbon black [137].

Li et al. [140] reported properties of hot-pressed ZrB2–15vol.%SiCw–(10,15,20)vol.%MoSi2 nanocomposites. A relative density of 99.9% was obtained for all samples at 1750°C. ZrB2–15vol.%SiCw–15vol.%MoSi2 nanocomposite showed the highest mechanical properties, with hardness of 17.64GPa, fracture toughness of 5.52MPam1/2, and flexural strength of 564MPa. Yue et al. [141] used SPS to prepare ZrB2–SiC reinforced with mixture of boron nitride nanotubes (BNNT) and boron nitride nanoplateles (BNNP). While the hardness and elastic modulus remained unchanged, a 24% increase in the fracture toughness was observed in the ZrB2–20vol.% SiC–1wt.% (BNNT–BNNP) nanocomposite compared to ZrB2–20vol.% SiC. Fattahi et al. [142] studied the effect of 0–3wt.% nano-diamond on microstructural and mechanical properties of ZrB2–25vol.% SiC nanocomposites. They prepared samples using SPS at 1900°C for 7min. All nanocomposites showed relative density higher than 98.8%. The authors analyzed the microstructure of the reinforced nanocomposites and observed the formation of ZrC and B4C. They reported increased hardness and fracture toughness, and the highest values were 24.6GPa for ZrB2–25vol.% SiC–2wt.% nano-diamond nanocomposite and 5.8MPam1/2 for the ZrB2–25vol.% SiC–3wt.% nano-diamond, as compared to 19.5GPa and 4.3MPam1/2 for ZrB2–25vol.% SiC composite, respectively. They attributed the increase in hardness to the formed hard phases during sintering, while the toughness increase was attributed to the establishment of toughening mechanisms such as crack deflection, branching, and crack bridging due to the presence of nano-diamond.

ZrC nanocompositesZirconium carbide (ZrC) belonging to the UHTCs group and has low density, very good mechanical and electrical properties, and good chemical and thermal stability [111]. Typical properties of ZrC are listed in Table 1. Difficulty to sinter and small fracture toughness are some challenges in the application of ZrC. [143]. Using new sintering techniques along with reinforcing ZrC matrix with a second phase have resulted in significant improvements in both fracture toughness and sinterability [112,144–147]. However, limited work is available on ZrC reinforced with hybrid reinforcements.

Acicbe et al. [111] studied the effect of TiC and MWCNTs on densification and mechanical properties of ZrC–TiC and ZrC–TiC–CNTs nanocomposites. ZrC showed relative density of 95.5%, which increased to more than 98% for all ZrC–TiC and ZrC–TiC–CNTs nanocomposites. Microstructural analysis showed homogeneous distribution along with some micro-cracks in ZrC–TiC composite, which disappeared by introducing CNTs in case of ZrC–TiC–CNTs nanocomposite. The hardness of ZrC increased from 17.6 to 22GPa for ZrC–TiC. However, introduction of CNTs caused the hardness to decrease, reaching a value of 20GPa for ZrC–20vol.%TiC–1wt.%CNTs nanocomposite. Increase in fracture toughness of ZrC (3.30MPam1/2) was observed with increasing the reinforcement content, reaching a value of 4.27MPam1/2 for ZrC–20vol.%TiC–1wt.%CNTs nanocomposite. Similar enhancements in properties of ZrC, by addition of 20vol.% Ti and 3vol.%CNTs, have been reported by Sha et al. [143]. A relative density of 98.27%, a hardness of 18.11GPa, a flexural modulus of 207GPa, and a flexural strength of 415MPa were measured for ZrC–20vol.%Ti–3vol.%CNTs nanocomposite. Moreover, a fracture toughness of 5.27MPam1/2 was obtained for the nanocomposite, which is 32% higher than that of ZrC. Li et al. [147] investigated the effect of 20vol.%Nb and 3vol.%CNTs on properties of hot-pressed ZrC as shown in Fig. 19. Improved sinterability was observed for ZrC–20vol.%Nb–3vol.%CNTs nanocomposite, reaching 99.28%. Microstructural analysis showed the formation of (Zr, Nb)C solid solution and ZrxCyOz compound during hot-pressing. An 80% increase in fracture toughness was reported for the nanocomposite, compared to ZrC. Furthermore, a hardness of 17.93GPa, a flexural modulus of 281GPa, and a flexural strength of 590MPa were obtained for ZrC–Nb–CNT nanocomposite. The effect of GNPs addition on microstructural and mechanical properties of ZrC–TiC based nanocomposites have been reported by Ocak et al. [148]. ZrC–(20−x)vol.%TiC–xvol.%GNPs (where x=0–9vol.%) nanocomposites were spark plasma sintered at 1700°C. Microstructural analysis showed the formation of (Zr, Ti)C solid solution by substitution of Zr+4 ions by Ti+4 during sintering. Densification of 99.49% and fracture toughness of 5.17MPam1/2 for ZrC–17vol.%TiC–3vol.%GNPs nanocomposite was found to be highest. Further addition of GNPs beyond 3 vol % resulted in a decrease in densification and fracture toughness. The hardness was found to decrease with an increase in GNPs content in ZrC–TiC–GNPs nanocomposites.

Properties of ZrC-based composite doped with Nb and CNT (a) relative density, (b) flexural stress–strain, and (c) load–displacement [147].

Typical properties of titanium nitride (TiN) are listed in Table 1. TiN has very high melting temperature, high hardness, good thermal and electrical conductivity, and very high corrosion resistance. It is mostly used in fabricating cermets and as coatings on metals and cutting tools [114,115]. Its use in many industries is limited because of its inadequate fracture toughness and poor sinterability [114,149]. Some of these limitations have been countered by the addition of a single reinforcement such as TiC [149], Si3N4[150], AlN [151], HfC [152], and graphene [115]. Due to the fact that TiN is employed as reinforcement for ceramic matrices, very limited work is available on TiN hybrid nanocomposites.

The effect of SiC and MWCNTs on densification and microstructure of TiN was investigated by Delbari and co-authors [114]. TiN and TiN–20vol.%SiC–5wt.%MWCNTs nanocomposite were produced by SPS at 1900°C and 40MPa for 7min. The relative density decreased from 81.5% for TiN to 79.9% for the TiN–20vol.%SiC–5wt.%MWCNTs nanocomposite as can be seen in Fig. 20. The authors analyzed the microstructure and observed the presence of SiC and MWCNTs at grain boundaries, which believed to hinder grain growth. They examined the fracture surface of the sintered nanocomposite, which showed several toughening mechanisms such as crack bridging, crack deflection, crack branching, and intergranular fracture mode [114].

Density of TiN-based ceramics [114].

Titanium carbide (TiC) has very high melting temperature, low density, high hardness, high thermal stability and conductivity, and high electrical conductivity as listed in Table 1. It is a suitable material for hypersonic space applications, cutting tools, refractory components, and in the nuclear industry [153–155]. To address issues associated with the sinterability and the inadequate fracture toughness of TiC, researchers developed TiC nanocomposites reinforced with a single phase such as graphene [154], SiC [155,156], ZrC [157], WC [158,159], nano-diamond [160], TiN [161] and CNTs [116], and hybrid nanocomposites that incorporates two phases [116,153,162–168].

TiC and hybrid TiC nanocomposite reinforced with 3.5wt.% WC and 2wt.% MWCNTs were prepared by SPS [116]. The relative density of TiC increased from 89 to 99% due to the addition of WC and CNTs. Furthermore, a reduction of 38% in grain size was observed for the TiC–3.5wt.%WC–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite compared to TiC. The hardness, elastic modulus, and fracture toughness of the TiC–3.5wt.%WC–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite increased by 41%, 42%, and 141%, respectively, compared to TiC [116]. In another study, Sribalaji et al. [153] investigated the thermal shock resistance of spark plasma sintered TiC and TiC–3.5wt.%WC–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite. The samples were thermally shocked at 1700°C in open air for 10 thermal cycles. Microstructural analysis of thermally shocked nanocomposite showed retention of most of CNTs, while some of them collapse to carbon. The nanocomposite showed 63% lower rate of mass change and 89% higher thermal shock resistance parameter (Rst), compared to the monolithic ceramic. The significant increase in thermal shock resistance was attributed to higher densification, higher fracture toughness, and homogenous distribution of CNTs. The thermally shocked TiC–3.5wt.%WC–2wt.%CNTs nanocomposite showed 74% higher hardness and 54% higher elastic modulus, compared to TiC. Fattahi et al. [162] studied the effect of 0–30vol.% SiCw whiskers and 3wt.% nano-WC on properties of TiC nanocomposites. Samples were prepared by SPS at 1900°C and 40MPa for 7min. The sintered nanocomposites showed high relative density and uniform dispersion of the reinforcements, and no significant grain growth was observed. The TiC–3wt.%WCn and TiC–3wt.%WCn–20vol.%SiCw samples had the highest hardness and flexural strength of 28.6GPa and 694MPa, respectively. In another work, Fattahi et al. [163] varied the amount of nano-sized WC (0, 1.5 and 3wt.%) in TiC–10vol.%SiCw; and reported an increase in the relative density of the TiC–SiCw composite from 98.73 to 99.43% with the addition of 1.5wt.% nano-WC. However, the density decreased with further addition of WC. Non-stoichiometric TiCx, in-situ TiC, SiC, and WSi2 were found to form in sintered samples. The hardness and flexural strength decreased, with the increase in the content of nano-WC, and reached 12GPa and 368MPa for TiC–10vol.%SiCw–3wt.%WC nanocomposite, compared to 24.54GPa and 511MPa for TiC–10vol.%SiCw, respectively. The authors attributed the decrease in the properties to the presence of the brittle WSi2 at grain boundaries. They reported slight increase in thermal conductivity, from 19.8 to 24.3W/mK when TiC–10vol.%SiCw was reinforced with 1.5wt.% nano-WC. Nguyen et al. [164] reinforced TiC with 0–5wt.% h-BN and 0–5wt.% Gnf to form hybrid nanocomposites and characterized the microstructure, and mechanical and frictional properties. They sintered the samples using SPS at 1900°C for 10min, and found that the hybrid reinforcements had negative impact on densification, where the relative density decreased from 95.5% (TiC) to 93.2% (TiC–5wt.%h-BN–5wt.%Gnf). Microstructural analysis of sintered samples revealed the formation of TiB2 and TiB in-situ phases, and the presence of carbon zones shown by dark areas in the scanning electron microscope (SEM) micrograph presented in Fig. 21 and confirmed by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) results. The h-BN reinforcement and the in-situ phases appeared uniformly distributed while the Gnf were present in the form of zones. Vickers hardness and flexural strength of TiC decreased from 3128HV and 504MPa to 2477HV and 457MPa, respectively, with addition of 5wt.%h-BN and 5wt.%Gnf. However, the coefficient of friction increased from 0.299 for TiC to 0.315 for the TiC–5wt.%h-BN–5wt.%Gnf. In another work, Nguyen et al. [165] reported the mechanical and thermal properties of TiC reinforced with 5wt.%TiN and 5wt.%nano-diamond. The nanocomposite was sintered using SPS at 1900°C for 10min. The authors found that the relative density decreased from 95.5 to 87.4% as a result of the addition of TiN and nano-diamond, and attributed this decrease to the formation of N2 gas due to the reaction between solid solution of Ti (C, N) formed due to TiN addition and graphitized carbon formed from the nano-diamond. The hybrid reinforcements were found to decrease the hardness and flexural strength. Similarly, the thermal conductivity decreased from 17.7W/mK (TiC) to 15.4W/mK (TiC–5wt.%TiN–5wt.% diamond). In another work, Nguyen and co-authors [166] reported the strengthening of TiC using 5wt.%AlN and 5wt.% GNPs. The nanocomposite samples were sintered using SPS at 1900°C for 10min. The relative density increased from 95.5% to 101.2% because of the addition of AlN and GNPs. Moreover, 35% increase in flexural strength was reported for TiC–5wt.%AlN–5wt.% GNPs nanocomposite, as compared to TiC. The increase in the flexural strength was attributed to grain refinement and uniform distribution of in-situ phases formed during sintering. Properties of MLG reinforced TiC–WC composites, prepared by two step sintering, have been reported by Sun et al. [167]. The authors used micro-TiC, nano-TiC, WC, and MLG powders to prepare TiC–10wt.%nano–TiC–3wt.%WC–(0–0.45wt.%)MLG nanocomposites. They sintered the samples by inductive hot-pressing in two-steps; first step at 1850°C for 5min and second step at 1750°C for 60min. All nanocomposites showed densification higher than 97%, with TiC–WC reinforced with 0.45wt.%MLG nanocomposite reaching 99.3%. Hardness and flexural strength were found to increase with the increase in MLG content, and reached 24.2GPa and 718.6MPa, respectively, for TiC–WC reinforced with 0.45wt.%MLG. The enhancements in hardness and flexural strength were attributed to the high densification and grain refinement. A relatively higher fracture toughness of 7.2MPam1/2 was also reported for TiC–10wt.%nano-TiC–3wt.%WC–0.45wt.%MLG nanocomposite. In other work, Sun et al. [168] reinforced TiC matrix with SiCnw and CNTs. TiC–2wt.%HfC–3wt.%ZrO2 were synergistically reinforced with 1.5wt.%CNTs and 0–6wt.%SiCnw. Two-step SPS was employed, 5min at 1800°C then cooling to 1650°C and holding for 30min. The relative density of all hybrid nanocomposite samples was found to be more than 98.5%. XRD analysis showed formation of solid solution with predominant phases of TiC, (Ti0.8, Hf0.2)C and ZrO2 in all samples. The hardness decreased from 24.47GPa (TiC–HfC–ZrO2) to 23.97GPa (TiC–HfC–ZrO2–1.5wt.%CNTs–3wt.SiCnw), but the flexural strength and fracture toughness increased by 48.1 and 56.9, respectively, as can be seen in Fig. 22. CNT/SiCnw bending, pullout as well as crack deflection and bridging, as shown in Fig. 23, were believed to be the primary toughening mechanisms.

SEM image of polished TiC–5wt.% h-BN–5wt.% graphite nanocomposite with EDS analysis [184].

Properties of TiC-based nanocomposites with different CNT/SiCnw ratios (a) relative density, (b) hardness, (c) flexural strength, and (d) flexural toughness [168].

Primary toughening mechanism in TiC-based nanocomposites [168].

Besides its extraordinary mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, high thermal conductivity and stability, and high electrical conductivity, tantalum carbide (TaC) has the highest melting point among all the UHTCs [169]. Typical properties of TaC are listed in Table 1. However, like other UHTCs, TaC also has poor sinterability and inadequate fracture toughness [170]. Addition of reinforcements such as graphene [171], CNTs [172], SiC [173], B4C [174], TaSi2[175], MoSi2[175] have resulted in improvements in sinterability and fracture toughness. Similarly, incorporating hybrid reinforcements in TaC have shown promising results [117,176–178].

Nisar et al. [117] studied the toughening of TaC by SiC and MWCNTs. They prepared TaC and TaC–15vol.%SiC–15vol.%CNTs nanocomposite by SPS (three-stage sintering) at 1850°C. The authors analyzed the microstructure of the sintered nanocomposite and did not observe new phases, however, they reported partial CNTs transformation to graphite. The relative density of 93%, fracture toughness of 3.1MPam1/2, and fracture strength of 23.4MPa for TaC increased to 98%, 11.4MPam1/2, and 182.6MPa for the TaC–15vol.%SiC–15vol.%CNTs nanocomposite, respectively. However, a decrease in hardness from 15.5GPa for TaC to 14.1GPa for the TaC–15vol.%SiC–15vol.%CNTs nanocomposite was observed, which was attributed to partial CNTs to graphite transformation during sintering. In another study, Nisar et al. [176] reported enhanced fretting and scratch wear behavior of TaC–15vol.%SiC–15vol.%CNTs nanocomposite. For fretting wear, the wear rate of TaC–15vol.%SiC–15vol.%CNTs nanocomposite decreased by 61% (4.1×10−7 mm3/Nm) as compared to 10.5×10−7 mm3/Nm for TaC, while for scratch wear the rate decreased from 8mm3/Nm to 2.7mm3/Nm. In another work, Nisar and co-authors [177] investigated thermal performance of spark plasma sintered TaC and TaC–15vol.%SiC–15vol.%CNTs nanocomposite. They exposed the sintered samples to plasma-arc jet under heat-flux of 2.5 MW/m2 for 30seconds. After exposure, 25% and 22% retention of TaC phase was observed in TaC and TaC–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite, respectively. Moreover, the thickness of the oxide scale layer, having major phase of Ta2O5, was found to be 30.1μm for TaC; which decreased to 20.1μm for TaC–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite. Enhanced thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat values of 40.8W/mK, 1731mm2/s, and 214.9J/kg.K were reported for the TaC–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite, compared to 18.5W/mK, 778mm2/s, and 164J/kgK for TaC at 100°C, respectively. A shift in the oxide layer formation temperature, from 735°C for TaC to 901°C for TaC–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite, was confirmed by thermogravemetric analysis (TGA). TaC was completely oxidized at 800°C during TGA analysis but not much change was observed in TaC–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite up to 1500°C. The authors attributed the enhancement in the oxidation resistance of the TaC–SiC–CNTs nanocomposite to the formation of a protective SiO2 along with grain sealing by CNTs. In other study, Al-Habib et al. [178] investigated the effect of graphene on sintering and mechanical properties of TaC–TiC–SiC composites. They obtained TaC–TiC–25vol.%SiC composite and TaC–TiC–25vol.%SiC–5wt.%graphene nanocomposite using SPS at 2000°C and 35MPa for 8min. Higher densification and hardness values of 95.1% and 19.8GPa were reported for the graphene–reinforced TaC-based nanocomposite, as compared to 92.4% and 18.5GPa for the TaC–TiC–SiC composite. Graphene was found to facilitate the densification process and improve hardness. XRD analysis of sintered samples showed the formation of many new phases during sintering such as Ti5Si3, TaC0.47, Ti3SiC2, Ti6C3.75, TiSi2 and Ta4C3.