Alumina-based insulators are widely used in regions with extreme temperature fluctuations, such as polar areas, due to their high mechanical strength, low thermal expansion, and excellent electrical insulation properties. To improve the reliability of electrical transmission lines in such environments, a detailed understanding of their structural and physical characteristics is needed. This study investigates the mechanical and microstructural properties of high-strength alumina-based insulators using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (SEM-EDAX). The manufacturing process is analyzed, focusing on density, porosity, and phase structure validation. The results show that increased mullite formation within the insulator structure improves mechanical strength, especially with low porosity (10.8%), having homogeneous size distribution and high density (2.73g/cm3). Strength tests indicate that the produced insulators resist forces up to 14kN. Among the samples, those produced using alumina powder show better mechanical strength and reliability, likely due to more controlled mullite formation and reduced impurity content. As a result, an improved production process for reliable alumina-based C12.5-650 insulators was produced. These findings provide valuable insights for significantly improving the production of alumina-based insulators for harsh environments.

Los aisladores a base de alúmina se utilizan ampliamente en regiones con fluctuaciones extremas de temperatura, como las zonas polares, debido a su alta resistencia mecánica, baja expansión térmica y excelentes propiedades de aislamiento eléctrico. Para mejorar la fiabilidad de las líneas de transmisión eléctrica en dichos entornos, es necesario comprender detalladamente sus características estructurales y físicas. Este estudio investiga las propiedades mecánicas y microestructurales de aisladores a base de alúmina de alta resistencia mediante difracción de rayos X (DRX) y microscopía electrónica de barrido con análisis de rayos X por dispersión de energía (SEM-EDAX). Se analiza el proceso de fabricación, centrándose en la densidad, la porosidad y la validación de la estructura de fases. Los resultados muestran que una mayor formación de mullita en la estructura de alúmina mejora la resistencia mecánica, especialmente con una baja porosidad (10,8%), una distribución de tamaño homogénea y una alta densidad (2,27g/cm3). Las pruebas de resistencia indican que los aisladores producidos resisten fuerzas de hasta 14kN. Entre las muestras, las producidas con polvo de alúmina de alta pureza presentan mayor resistencia mecánica y fiabilidad, probablemente debido a una formación más controlada de mullita y a un menor contenido de impurezas. Como resultado, se desarrolló un proceso de producción mejorado para aisladores C12.5-650 fiables a base de alúmina. El proceso produjo aisladores con una porosidad del 10,8%, una densidad de 2,27g/cm3 y un rendimiento mecánico superior al de los tipos tradicionales C8-650. Estos hallazgos aportan información valiosa para mejorar significativamente la producción de aisladores a base de alúmina para entornos hostiles.

The efficient transmission of electrical energy from production sites is carried out through power transmission lines. In these lines, the materials that secure conductors to poles, separate the conductors and provide insulation from the ground are called insulators. Insulators have two main functions: first, to electrically isolate the conductors from each other and from the ground; and second, to mechanically support the conductors and any additional loads acting on them [1–4]. Insulators, by definition, require both electrical resistance and exceptional mechanical strength. Insulators must withstand mechanical loads at both low and high temperatures while maintaining reliable performance under diverse environmental conditions [5–13].

Insulators are classified according to the materials they are made from, their intended applications, and their types. Ceramic insulators, glass insulators, and silicone (composite) insulators are commonly used in transmission lines. Ceramic insulators are the preferred choice for low-, medium-, and high-voltage networks due to their long service life. In low- and medium-voltage transmission lines, the ceramic insulators used are SiO2-based quartz insulators. These insulators are produced from raw materials composed of 50% kaolin, 25% quartz, and 25% feldspar [1,2]. Their microstructure contains a significant amount of quartz, which leads to the formation of many microcracks; hence, these insulators are typically used in low-voltage lines where high mechanical loads are not required.

Quartz-based insulators tend to have lower strength, which is why they are mainly used in medium and low-voltage transmission lines. In these lines, the insulators are smaller in size because they are designed to withstand lower bending strength and electrical load. However, quartz-based insulators are not suitable for areas with extreme weather conditions, such as near the polar regions, where there are big temperature changes between day and night. These temperature changes generate thermal stress in the material, which can cause the tiny cracks in quartz-based insulators to expand over time. This can harm the insulator's mechanical integrity and lead to failure in the transmission lines [1,2,12,14]. The proportion of quartz formations in the microstructure of bauxite-based insulators is higher compared to alumina-based insulators. The proportion of quartz formations in the microstructure of bauxite-based and SiO2 based insulators is also high. Quartz structures cause microcracks in the ceramic material. In regions with high temperature fluctuations, it has been observed in past applications that these microcracks increase and cause deformation of the insulators [14–16]. Therefore, alumina-based insulators are used in regions with significant temperature fluctuations (deserts, polar areas) [17]. In alumina-based insulators, quartz structures are less common compared to other types. This contributes to safer use in transmission lines. Failures occurring in these lines lead to high costs.

Bauxite-type insulators (C8) are employed in transmission lines with lower mechanical loads (around 8kN), while alumina-based insulators (C12.5) are used where mechanical loads are higher (around 12.5kN). A higher alumina content increases the strength of the insulator. Numerous studies in the literature have focused on improving the aluminum oxide (Al2O3) strength of insulators [1,3,12,16,18]. Bauxite-based insulators are produced from bauxite raw material containing 85% Al2O3. Alumina (aluminum oxide) is a high-melting-point ceramic known for its excellent electrical insulation and superior mechanical properties—high hardness, robust compressive strength, and a high elastic modulus—and is widely employed in cutting tools [4], protective coatings [6,7], thermal barrier systems [16–18], and structural components [11]. It also has outstanding chemical and thermal stability, making it resilient in harsh, high-temperature environments.

Since bauxite with such high Al2O3 content is not available everywhere, alumina powder is widely used to manufacture insulators for high-voltage transmission lines [21,22]. Alumina-based insulators are specifically engineered to meet strength requirements, particularly for types like C8 and C12.5. This is why alumina-based insulators are commonly used in electric power transmission systems to provide isolation between conductive components. Alumina-based insulators are often employed in applications such as circuit boards, high-voltage electrical equipment, spark plugs, and more [23–25]. Known for their high dielectric strength, excellent mechanical properties, and thermal stability, alumina insulators are ideal for environments where both electrical insulation and resistance to temperature extremes are critically important. For applications where both strength and temperature fluctuations are critical, alumina-based insulators are preferred [26].

Alumina-based insulators are the better choice for regions with extreme temperature changes because they are more resistant to cracking, mechanical shocks, and electrical flashovers. Made from high-quality alumina ceramics, they handle expansion and contraction better than bauxite-based insulators, preventing damage from thermal stress. Their higher strength makes them more durable against ice-shedding impacts. Their strong build helps them last longer, even in harsh weather conditions. C12.5 insulators are designed to withstand extreme temperature fluctuations, typically ranging from −40°C to +50°C or more [4,8]. Due to this characteristic, it can also be used in regions with a desert climate.

In the literature, there are studies aimed at enhancing the strength of insulators by using various additives in addition to Al2O3. One of the most commonly employed additives in research is MgO [1,16,24,27,28]. In [1], Xu et al. created alumina/zirconia composite ceramics comprising α-Al2O3, partially stabilized zirconia, MgO and TiO2, using the pressureless sintering technique. These ceramics were used to produce alumina-based ceramic insulators known for their remarkable physical strength and exceptional freeze–thaw resistance, making them suitable for extremely cold regions. Mehtaa et al. [16] analyzed the effect of sintering temperature and SiO2 percentage that aimed to produce a high-strength, low-thermal conductivity insulator and to reduce raw material costs by increasing the silica ratio and reducing the alumina concentration in the basic porcelain composition. Recent articles, such as [24,27,28], also investigate the effect of MgO addition into alumina-based ceramic composites.

Montoya et al. [29] explored the impact of incorporating secondary mullite crystals into standard alumina porcelain via TiO2 addition, assessing their effects on microstructure and flexural strength. The authors noted improvements in the mechanical properties of alumina porcelain, along with increased quantities of secondary mullite and enhanced density [29]. On the other hand, alumina-based porcelains do not undergo phase transformations and are less vulnerable to crack formation during cooling, contributing to quartz's general robustness compared to porcelain. The grain size, quantity, and distribution of produced phases during the production process emerge as the primary factors influencing the physical and mechanical properties of porcelains [30].

In our previous work [19], we investigated the production process of bauxite-based insulators, which are cheaper because bauxite is readily available in nature. However, bauxite of suitable quality for insulator production is limited. The bauxite raw material used must contain more than 85% Al2O3 content to ensure adequate strength in the produced insulator. The higher the Al2O3 content, the stronger the resulting insulator will be. In this study, alumina-based insulators, specifically C12.5-650, are preferred over bauxite-based C8-650 insulators due to their superior mechanical strength, higher resistance to high temperatures, corrosion, and better performance under extreme weather conditions.

This paper investigates the detailed production process of alumina-based insulators by examining the specific manufacturing stages, material composition, and process conditions that contribute to the enhanced performance of these insulators. We explore the use of alumina powder and the specific sintering processes that result in the desired properties, providing concrete proof of how these factors directly influence the mechanical strength and durability of the insulators in challenging environments.

Appropriate fabrication processes play a crucial role in ensuring the creation of high-quality, dependable insulators [31]. This study aims to examine in detail the stages and processes integral to the production of high-voltage insulators from alumina, offering valuable insights for insulator manufacturing. Errors occurring during production can directly impact insulator quality. Therefore, this study investigates real-time production stages in a high-voltage insulator manufacturing factory to enhance understanding and refine manufacturing practices. This study was conducted at the production facility of one of the largest ceramic manufacturers in Ankara, Turkey. In this research, we collaborated with this company, which specializes in the production of porcelain insulators. Over the years, this company has manufactured various types of porcelain insulators. The results of this research have been used by this company to produce high-quality insulators commercially, including the C12.5-650 model.

Insulators are manufactured under approval from the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation (TEIAS), based on electrical testing to assess the insulation capacity against high-voltage flashover.

Usually, in the literature, microstructures have been examined without specifying the sintering program, which is an important stage in porcelain production [31,18]. In this study, we conducted an oxidative investigation using a natural gas sintering furnace within an actual production setting. This approach allows for a more detailed understanding of the sintering process and its impact on the microstructure, contributing to a more comprehensive analysis of alumina-based insulator production. The results presented in this study are based on extensive testing and data accumulated over several years, ensuring the reliability and robustness of the findings. These insights are particularly valuable for improving the manufacturing processes of alumina-based insulators and enhancing their performance in challenging environments.

The rest of the paper has been organized as follows: Section 2 describes the main manufacturing process. Then, Section 3 presents the analysis results of the applied process and discusses the results. Finally, Section 4 gives concluding remarks.

Materials and experimental procedureMaterial processingThe raw materials used in insulator production include Al2O3 (purity 99.87%, Esan, Istanbul, Turkey), feldspar (Esan, Istanbul, Turkey), ball clay (Esan, Istanbul, Turkey), and two distinct types of clay (both from Ömer Ertürk Madencilik, Afyon, Turkey). Clay type 1 has high alumina content. Clay type 2, on the other hand, has a relatively lower alumina content but higher binding capacity. Rigaku Rint 2000 was used to perform an XRD analysis to identify the elements in the raw material. In order to determine the crystalline structure of materials, an analysis was conducted to extract their elemental composition and respective percentage values. The mineralogical composition ratios in the mixture were subsequently calculated, as presented in Table 1. The alumina powder serving as the foundational material was required to have a particle size smaller than 40μm. Therefore, alumina with a particle size of around 40μm was chosen. This also reduces the porosity ratio (Fig. 1). The particle size distribution was measured using a MALVERN M2000 (Malvern Instruments Ltd, Worcestershire, UK) instrument.

Raw material composition.

| Material | Elements (percentage (%)) | Ratio in mixture (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | CaO | MgO | NaO2 | K2O | P2O5 | Others | ||

| Al2O3 | 0.08 | 99.87 | 0.05 | – | 0.05 | 0.01 | 32 | ||||

| K. Felspat | 70.74 | 16.43 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 3.04 | 8.27 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 20 |

| Ball clay | 54.94 | 27.45 | 2.85 | 0.268 | 0.25 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 2.73 | 10.72 | 18 | |

| Clay1 | 47 | 37.61 | 0.53 | 2 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 12.29 | 10 | |

| Clay2 | 65 | 23 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 0.04 | 6.36 | 20 |

| Raw material | 47.552 | 40.872 | 0.956 | 0.7436 | 0.206 | 0.304 | 0.72 | 2.682 | 0.042 | 5.94 | 100 |

Alumina, feldspar, ball clay, and two distinct clay raw materials are added to the mill (milling process) and mixed. A 12-h milling process was applied to the prepared mixture to ensure homogenization of its constituents. Subsequently, the mixture was shaped into cylindrical forms measuring 420mm in diameter and 2.2m in length using a vacuum press.

Drying processAfter exiting the vacuum press, these materials exhibited a humidity level of 17–18%. Precise control of moisture content is crucial in ceramic processing to ensure successful shaping [32]. Before the shaping process, the moisture content of the cylindrical material (taken from the vacuum process) should be 14–15%. If the moisture content exceeds the specified range during shaping on the CNC vertical lathe, the material cannot be properly formed, resulting in structural failure or breakage during rotation. This narrow moisture range is critical for maintaining the material's green strength and dimensional stability during machining.

The insulator shaping process is performed at spindle speeds of 40–50rpm. During machining trials, higher moisture content led to breakage of the insulators at these speeds. These parameters were established experimentally to ensure the shed shape of the insulator is maintained during processing and to prevent cracking. Moisture levels above the optimal range result in breakage, while levels below it cause cracks in the shed. These findings are essential for achieving high mechanical strength in the final product.

This drying process (reducing moisture from 17–18% to 14–15%) can be done by storing vacuum-formed cylindrical materials in a humidity-controlled environment. Alternatively, an electric drying process can be applied. Since air-drying takes a long time, the electric drying method was used in this study [21]. During this process, humidity was measured and controlled using a moisture analyzer (Labtex Humidity Moisture Meter).

The processed materials undergo a heating process in drying rooms, transitioning from an initial temperature of 20°C to a range of 100–120°C at a controlled rate of 5°C per hour. The drying chamber is controlled automatically using a thermocouple for temperature control and humidity sensors, with Siemens S7-1200 PLC control. This heating process is accompanied by humidity and temperature control. After CNC processing at a moisture content of 14–15% for 30h, the insulators undergo a drying process, reducing the moisture content by 0.5–0.6% per hour. It is important to make sure that the moisture content of the materials before this heating phase falls into the range of 1–1.5%. Deviation from this moisture content threshold may lead to the formation of cracks within the insulator body during the subsequent sintering process.

Insulator neck designThe neck diameter of the insulator, where it hangs in the furnace, must be large enough to support its own weight at high temperatures. This is important for obtaining flawless products during the sintering process. During sintering, the material should shrink and, after reaching 900°C, lose contact with the surface it was in contact with and remain suspended. Through experiments conducted during raw material preparation, the expansion and shrinkage percentages are calculated. These percentages are used in calculating the suspension lengths (Fig. 2).

Otherwise, the insulator may experience breakage at the neck area due to the inability to withstand its own weight at 900°C. During cooling, the shrinkage of the insulator's length and diameter allows it to remain suspended, ensuring the production of a flat insulator. If the base surface of the insulator contacts the ground too early or if it does not remain suspended during cooling, the insulator will bend. This affects the insulator's linearity. The shrinkage percentages of the insulator have been calculated for this process. Beyond a certain temperature, insulator shrinkage stabilizes, resulting in the production of a linear insulator. The insulator must maintain its shape and remain horizontal. Failure to do so may cause the insulator to deform under its own weight, leading to non-linearity.

The percentage shrinkage rates for the insulator in this process were calculated as follows:

- •

Dry shrinkage values: Diameter 3.56%/Length: 4.98%

- •

Sintering shrinkage values: Diameter: 10.10%/Length: 10.26%

Using Netzsch, model STA 409PG/4/G (Luxx, USA) TG-DTG analysis of the raw material was conducted to obtain information about the percentage shrinkage and phase change points. TG-DTG analyses were conducted according to ISO 11358 and ASTM E 1131-20 standards.

Sintering processThe sintering program for a natural gas oven is outlined in Fig. 3(a). According to the graph in Fig. 3(b), the initial sintering program was created. As the produced items at all stages were examined, updates were made to the sintering program. The material is gradually heated up to 540°C at an average rate of 30°C/h. Between 540 and 580°C, the temperature is increased at a slow rate of 5°C/h to remove flammable materials (organic, sulfide, and carbonate) without damaging the integrity of the insulator. The transition between 570°C and 580°C is critical to avoid the formation of cracks. Therefore, this temperature transition is carried out at a rate of 5°C/h (see Fig. 4).

The subsequent heating from 580°C to 920°C is carried out at a rate of 20°C/h. To induce phase transformations at 920°C, a gradual temperature rise rate of 3–5°C/h is applied until reaching 950°C. Temperatures then increase from 950°C to 1350°C at a rate of 30°C/h. During this phase, the quartz melting and mullite needle structure transformations start to occur, between 1150 and 1350°C. These phase transformations are allowed to proceed for 3h.

At elevated temperatures, around 1350°C, the material transitions into a molten or semi-molten state, establishing thermodynamically favorable conditions for mullite formation. Rapid cooling from this temperature range, implemented at a controlled rate of 150°C/h down to 900°C, is critical for suppressing the development of undesirable crystalline phases—particularly the recrystallization of quartz—while promoting the formation of a glassy matrix. This thermal management strategy enhances the mechanical properties of the material by reducing microstructural defects and minimizing the likelihood of microcracking. This phenomenon has also been documented in the literature; for instance, Wilke et al. (2022) reported that rapid cooling significantly reduces crystallization tendencies [33].

Upon reaching 900°C, a transition to a slower cooling rate becomes essential to mitigate thermal stresses associated with phase transformations. As the temperature approaches 573°C—corresponding to the β→α quartz transformation, which is known to induce microcracking if not properly managed—the cooling rate is further reduced to 15°C/h. This gradual transition minimizes thermal gradients and relieves stress accumulated during the earlier rapid cooling phase. After passing this critical transition, the material is cooled to room temperature at a rate of 25°C/h. Overall, the precise control of cooling rates across these temperature ranges plays a vital role in optimizing the final microstructure and enhancing the mechanical performance of the product.

Analysis of results and discussionThe C12.5-650 insulators are manufactured in accordance with the technical specifications outlined in Table 2, which define the expected electrical and mechanical performance parameters. These specifications are based on international standards. The specifications have been formally approved by the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation (TEIAS). Prior to market release, each production batch undergoes TEIAS inspection to ensure full compliance with the approved standards. The data presented in Table 2 serves as the foundation for both production and quality control processes. The results of this study confirm that the manufacturing process consistently meets the specified requirements, thereby ensuring the reliability, conformity, and suitability of the insulators for commercial application.

C12.5-650 insulator values (IEC 60168).

| Electrical and mechanical properties | C12.5-650 |

|---|---|

| Dry lightning impulse withstand voltage (kV) | 650 |

| Wet power frequency withstand voltage (kV) | 275 |

| Minimum bending load (kN) | 12.5 |

| Minimum torsion load (kNm) | 6 |

| Insulator piece height ‘H’ (mm) | 1500±2.5 |

| Insulator piece maximum diameter ‘D’ (mm) | 240 |

| Upper metal hole axis diameter ‘d2’ (mm) | Ø127 |

| Upper metal connection hole-tooth quantity/size (mm) | 4xM164xØ18 |

| Lower metal hole axis diameter ‘d3’ (mm) | Ø254 |

| Lower metal connection hole-tooth quantity/size (mm) | 8xØ18 |

After completing the production stages of the C12.5-650 insulator (Fig. 4), as described above, and whose electrical and mechanical properties are given in Table 2, sections taken from different regions of the insulator, from the inner diameter and various places from the outer diameter, were examined for deeper analysis (Fig. 5). Extracted sections of the final product were examined using the Zeiss Supra 50 VP Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Germany) imaging technique and bending strength tests. The results of these analyses are presented below.

The mechanical tests of the insulator were carried out according to the IEC 60383-1:1993 MOD standard.

Porosity and densityPores form within insulator bodies because of the decomposition of organic and inorganic compounds found in raw materials, such as carbonates and sulfates, among others. The homogenous distribution, size, and shape of these pores within the microstructure are critical. Ideally, the pores should have dimensions and shapes that do not cause cracking. The bulk density of samples was calculated according to ASTM C373-88.

The porosity in the microstructure was calculated using the ImageJ program. SEM images were obtained from separate samples taken from four different regions to determine the average porosity value (Table 3). Porosity calculations were performed using section images taken from four different regions of the insulator (from the inner diameter and various places from the outer diameter). When the microstructure was examined with the ImageJ program, microstructural examination showed that the pores are predominantly uniform, (Fig. 6a), often circular, and occasionally elliptical. The analyses showed that in the samples closer to the center, the size of the porosity increased while the number of pores decreased (Sample I), whereas toward the outer diameter, the size of the porosity decreased while the number of pores increased (Sample IV). The average pore size is 2.59μm, and a few larger pores (above 100μm) are also observed. Calculations obtained from ImageJ, based on SEM images of the microstructures yield a porosity percentage of 10.8% and a standard deviation is 0.092g/cm3 (Table 3). The minimum size of pores that can be observed is 0.541μm. Using the software, we have extracted exactly the same size from all four samples for analysis.

Porosity calculation.

| Number of pores | Porosity area (μm) | Total porosity area (μm) | Total sample area (μm) | Porosity percentage % | Densty g/cm3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | Max. | Mean | ||||||

| Sample 1 | 9642 | 0.541 | 562.284 | 8.642 | 83,324.380 | 751,334.00 | 11.09 | 2.79 |

| Sample 2 | 12865 | 0.541 | 338.452 | 6.116 | 78,683.380 | 751,334.00 | 10.47 | 2.58 |

| Sample 3 | 25750 | 0.541 | 393.058 | 3.690 | 95,017.310 | 751,334.00 | 12.64 | 2.74 |

| Sample 4 | 42071 | 0.541 | 101.644 | 1.609 | 67,691.820 | 751,334.00 | 9.00 | 2.82 |

| Average porosity percentage % | 10.80 | |||||||

| Standard deviation | 1.305 | 0.092 | ||||||

In the literature, this percentage ranges from 9% to 11% [12–16,20]. Furthermore, there are limited irregularities in the pores that could impact insulator strength. A few pores capable of promoting crack formation were identified which can be seen in Fig. 6b.

The increase in porosity percentages correlates with the decrease in density. Higher insulator density enhances both its mechanical strength and electrical properties. Density measurements indicate a porcelain density of 2.73g/cm. In the literature, it was determined that 2.8, 2.6 and 2.56g/cm3[12,19,20]. That is why the density value that we have obtained is very similar to the results presented in the literature. This shows that although the porosity is high, the corundum and mullite structures in the microstructure are also high. Higher density values indicate lower porosity percentages and huge amounts of primary and secondary mullite needle structures within the microstructure. Sintering alumina-based ceramics up to 1350°C causes the melting of amorphous structures, which results in filling the pores and reducing porosity while increasing density.

Microstructure analysisMicrostructural analysis reveals the existence of corundum structures, which play a crucial role in strengthening the insulator. Corundum has a high Young's modulus, exceptional hardness, a high melting point, and a low coefficient of expansion, making it highly resistant to deformation [34].

Fig. 7 shows SEM images of corundum formation, highlighting its distribution within the microstructure. These corundum structures appear as unmelted particles embedded within the material. The elemental composition of these regions is detailed in Table 4, which provides a breakdown of the elements detected in the area marked as spectrum 3 in Fig. 7.

Distribution of elements of the region marked as spectrum 3 in Fig. 7.

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | Compd% | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al K | 52.93 | 40.00 | 100.00 | Al2O3 |

| O | 47.07 | 60.00 | ||

| Totals | 100.00 |

Additionally, the EDS pattern in Fig. 8 further confirms the composition of corundum in the analyzed region. The presence of these structures, along with surrounding mullite needle formations, helps prevent crack formation and enhances the overall mechanical strength of the insulator [35]. The corundum formations are observed to range in size from 18 to 22μm.

EDS pattern of corundum formation of the region marked as spectrum 3 in Fig. 7.

Microstructure analysis also shows the presence of both primary and secondary mullite structures which significantly contribute to the mechanical strength and thermal stability of the insulator material. Fig. 9 presents SEM images illustrating the formation of primary and secondary mullite. Primary mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2) results from the transformation of substances like metakaolin and pyrophyllite during the sintering process. It can be described as a short and dense morphology, which enhances the compactness of the material. Secondary mullite (2Al2O3·SiO2), on the other hand, forms through reactions between the melt and clay residues, generating needle-like structures that improve the toughness of the final product.

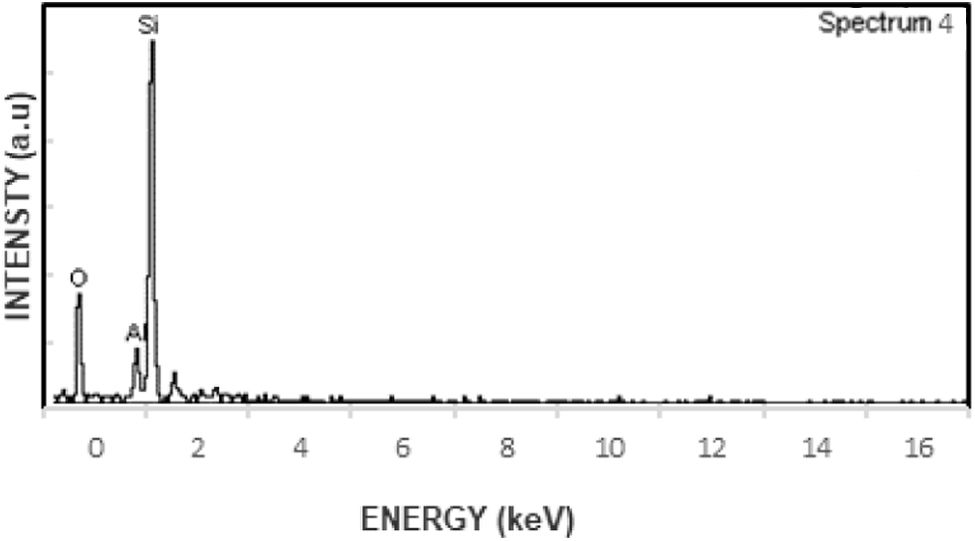

Fig. 10 provides the EDS pattern for primary and secondary mullite, specifically for the region marked as spectrum 1 in Fig. 9. This pattern confirms the elemental composition of the analyzed area. The distribution of elements in the same region is detailed in Table 5, which further supports the identification of mullite structures within the microstructure. Additionally, Fig. 11 presents another set of SEM images highlighting the formation and distribution of primary and secondary mullite, reinforcing their significance in improving the overall performance of the insulator material.

EDS pattern of primary and secondary mullite formation of the region marked as spectrum 1 in Fig. 9.

Distribution of elements of the region marked as spectrum 1 in Fig. 9.

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | Compd% | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al K | 30.16 | 22.88 | 56.98 | Al2O3 |

| Si K | 18.61 | 13.57 | 39.81 | SiO2 |

| K K | 2.67 | 1.40 | 3.22 | K2O |

| O | 48.57 | 62.15 | ||

| Totals | 100.00 |

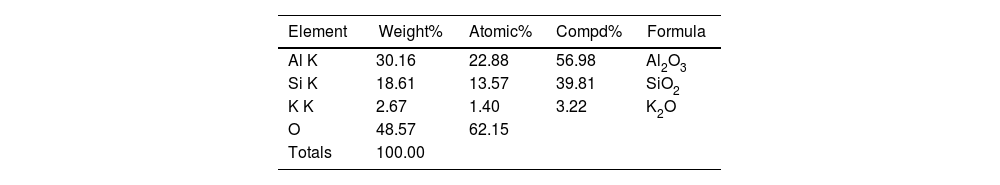

Additionally, SEM images (Fig. 12) reveal areas where corundum and quartz coexist, with their chemical composition further analyzed in Fig. 13 and Table 6. These phases are essential in balancing the mechanical and thermal properties of the material. A closer examination of the quartz phase is provided in Fig. 14, supported by its EDS analysis (Fig. 15) and elemental distribution data (Table 7), which highlight its structural characteristics.

EDS pattern of corundum and quartz of the region marked as spectrum 4 in Fig. 12.

Distribution of elements of the region marked as spectrum 4 in Fig. 12.

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | Compd% | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al K | 4.37 | 3.25 | 8.25 | Al2O3 |

| Si K | 42.89 | 30.63 | 91.75 | SiO2 |

| O | 53.26 | 66.13 | ||

| Totals | 100.00 |

EDS pattern of quartz formation of the region marked as spectrum 2 in Fig. 14.

Distribution of elements of the region marked as spectrum 2 in Fig. 14.

| Element | Weight% | Atomic% | Compd% | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si K | 46.74 | 33.33 | 100.00 | SiO2 |

| O | 53.26 | 66.67 | ||

| Totals | 100.00 |

One key finding is that mullite structures form around the non-crystalline material, helping to strengthen the insulator and prevent cracks from spreading [35]. The well-distributed mullite needles act as reinforcement, preventing the uncontrolled growth of microcracks that could otherwise compromise the insulator's performance under mechanical and thermal stress [35].

Microcrack structureMicrocracks, which typically occur around corundum and quartz structures, were examined within the microstructure. These cracks, measuring 15–20μm in size, are distributed in limited areas and have acceptable dimensions (see Fig. 16) [36]. Cracks primarily result from volume reduction and around 572°C β-α phase transformations during cooling, particularly in quartz structures. Widespread formation of these cracks is prevented during the sintering process by maintaining a temperature of around 573°C. These temperature points were determined from the DTG graphs, specifically from the peak points. Based on these points, a sintering program was developed. Additionally, the presence of mullite needle formations around these structures reduces the impact of these cracks.

Bending strength testTo assess the strength of the produced insulators, they were cut to the insulator's pre-flange assembly dimensions (Table 1), and connection parts were mounted on both ends using cement. Because a standard test device of this size was not readily available, a hydraulically driven test device tailored to the insulator's requirements was designed and produced by a specialized test device manufacturing firm, whose photograph is shown in Fig. 17(b). Comprehensive tests conducted on the fully finished products reveal a flexural strength of 12.5kN. The insulator was tested by applying a force of 12.5kN from three different points, each 120° degrees apart from the outermost point (d2, shown in Fig. 5). It has been observed that the insulator did not break under this force. However, when the force has been increased from a single point, it finally broke at 14kN in the lower flange region (d3, shown in Fig. 5). The bending test was performed on four samples, and the standard deviation was found to be 0.196kN (Table 8). This suggests that the insulator has a uniform structure, and the fracture occurred in the area where the moment is at its maximum.

The cross-section of the fractured insulator is depicted in Fig. 17(a). Following this test, it was observed that the C12.5-650 high-voltage insulator satisfies the necessary strength requirements. Fig. 17 shows the fracture image of the insulator from the base flash area after the test. It can be observed that the insulator is sintered all the way to its innermost region. This test's outcome leads to the conclusion that the production stages and raw material selection for the high-voltage insulator are appropriate according to IEC 60383-1:1993 MOD standard.

Shrinkage and TG-DTG analysisThe values for dry shrinkage and cooling shrinkage were derived by examining the TG analysis (Fig. 3b). Prior to production, the raw material undergoes testing in a laboratory setting. Small-scale samples are prepared and sintered in an electric furnace, and the resulting shrinkage rates are determined. These determined values are then applied in the full-scale production process. After preliminary data is obtained from TG analyses, the actual shrinkage rates are determined based on the results of these tests. When this graph is analyzed, it can be observed that the raw material experiences approximately 5% volume loss at around 120–130°C, and a volume loss of nearly 20% occurs when the temperature rises to 1200–1300°C. These losses are attributed to organic materials and phase structure transformations. Initially, calculations were made based on these values, and in later trial productions, dry shrinkage was measured at approximately 3.56% in diameter and 4.98% in length, while sintering shrinkage reached 10.10% in diameter and 10.26% in length.

Phase transition temperatures were identified with the help of the DTG analysis. When this graph is examined, peaks are observed at certain temperatures. These peak points correspond to the temperatures at which the structure of the raw material changes. At these temperatures, sufficient time must be allowed for the material's structure to change, or the sintering process should be carried out with a low-temperature increase. Initially, a structural change occurs at approximately 300°C as organic materials are removed from the raw material. The second transformation is observed at around 570°C. Therefore, when developing the sintering program, a temperature increase rate of 5°C/h was applied between 540 and 580°C to include this transition point. This ensured the completion of the phase structure transformations. The final phase transformation temperature is around 920°C. Thus, a gradual temperature increase of 3–5°C/h is used between 900 and 950°C.

ConclusionIn this study, we investigated the production processes of alumina-based high-strength, high-voltage insulators. Raw material compositions were identified through elemental analysis. SEM and EDAX analyses on insulator porcelain microsections revealed microstructures like corundum, quartz, mullite, and microcracks. Relationships between these microstructures to specific production stages are established, in order to determine the precision of the production processes.

Our investigation extended to the production site, where we determined the raw material preparation, drying, and sintering program. This allowed us to closely follow the production stages of these high-strength, high-tensile insulators. The porosity ratio was calculated from the microstructures obtained from SEM images and found to be 10.8%. It was observed that the porosity has a homogeneous size and distribution. The density value that we have obtained in our experiments (2.73g/cm3) is close to the upper limit of the results in the literature (2.58–2.80g/cm3). The result of the strength test shows that the insulator's structure is resistant up to 14kN. This observation indicates that the resulting microstructure formations were effective, reflecting good compatibility between the provided raw materials and the applied sintering programs.

The suitability of the sintering process, an important component of porcelain production, was evaluated by examination of microstructures. It is noteworthy that in many studies within the literature, the sintering program remains undisclosed. We have observed that our carefully designed sintering program promotes the melting of amorphous structures, which fills the pores, reduces porosity, and increases density.

Microcracks are a commonly observed feature in porcelain materials. These cracks are usually observable around quartz particles. During cooling, the glassy structure surrounding the quartz particles shrinks more, causing the formation of microcracks around them. Therefore, the thermomechanical performance of quartz porcelains is less stable compared to alumina-based porcelains. This issue can cause problems, especially in regions with significant temperature differences between day and night (polar regions), during the use of quartz porcelain insulators. In this study, the production processes of the alumina-based insulator were significantly improved to minimize the formation of quartz structures in the microstructure of the insulator. The formation of corundum in the microstructure was maximized.