Environmentally friendly (Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3 ceramics (BCZT) are being investigated as a viable alternative to the leading commercially used lead titanate–zirconate ceramics. These ferro-piezoelectric ceramics exhibit fascinating properties for a range of applications, dependent on several multiscale characteristics, including composition, crystal structure, domain structure, ceramic microstructure and bulk issues. To provide reproducible quality, a thorough grasp of processing control is essential. This review begins with a historical overview of BCZT ceramic development, followed by a phase diagram examination. The morphotropic phase boundary is explored, detailing the intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to the system's piezoelectricity, as well as the critical aspects to consider while processing. The factors to contemplate for an industrially scalable solid state processing pathway are reviewed, with a focus on mechanical activation. Additionally, the milling processes utilized for BCZT synthesis and sintering, as well as water-based sustainable processing, are analysed. The assessment concludes with the promise of emerging uses in biotechnology for medical purposes.

En la actualidad, como alternativa viable a las principales cerámicas de titanato-circonato de plomo utilizadas comercialmente, se están investigando cerámicas del sistema (Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3 (BCZT), respetuosas con el medio ambiente. Estas cerámicas ferro-piezoeléctricas presentan propiedades interesantes para una amplia variedad de aplicaciones. Tales propiedades dependen de diversas características a diferentes escalas, tales como composición, estructura cristalina, estructura de dominios, microestructura cerámica o propiedades de volumen de la cerámica. Para ofrecer una calidad reproducible, es esencial conocer y controlar en profundidad el procesamiento. Esta revisión comienza con una visión histórica del desarrollo de la cerámica BCZT, seguida de un examen del diagrama de fases. Se explora la frontera morfotrópica de fase, detallando las contribuciones intrínsecas y extrínsecas a la piezoelectricidad del sistema, así como los aspectos críticos a tener en cuenta durante el procesamiento. Se revisan los factores a considerar para una vía de procesamiento en estado sólido industrialmente escalable, con especial atención a la activación mecánica. Además, se analizan los procesos de molienda utilizados para la síntesis y sinterización del BCZT, así como el procesamiento sostenible a base de agua. La evaluación concluye con el uso potencial en biotecnología con fines médicos.

Governing the processing method has the potential to develop new classes of materials and alter the microstructure to improve the material properties [1]. Nowadays, the sustainability of the whole process represents a further requirement due to the ever-increasing issues related with the scarcity of raw materials, human health and climate changes. With regard to these aspects, piezoceramics, the core of key technological devices, merits a special attention [2,3].

According to the most recent national and international directives, which significantly restrict the use of hazardous substances and zero-carbon emission processes, requiring an efficient and sustainable energy consumption, the replacement of the market-dominant lead zirconate titanate-based (PZT) piezoceramic with lead-free systems cannot be postponed [4,5]. Within this context, one of the most promising candidates is the (Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3 (BCZT) system, a modified BaTiO3-based compound with remarkable properties, as summarized in Fig. 1[6,7].

Comparative analysis of lead-free piezoelectric materials [(Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3, BCZT; (Bi,Na)TiO3, BNT; (K,Na)NbO3, KNN] against the lead-based PZT in terms of key properties: piezoelectric coefficient (d33), electromechanical coupling factor (kp), Curie temperature (Tc), thermal stability, favourable processing temperatures, critical raw materials, and biocompatibility. The radar chart highlights the advantages and limitations of each material, with BCZT showing promising properties as a lead-free alternative.

The optimal composition Ba(Ti0.8Zr0.2)O3–(Ba0.7Ca0.3)TiO3 presents comparable properties to those of the commercially available lead-based materials (600pC/N vs up to ≈300pC/N for hard-PZT and up to ≈550pC/N for soft PZT) [8,9]. With respect to the PZT-based systems, it has a lower density (6g/cm3 vs 8g/cm3), making BCZT suitable for acoustic applications [3]. Not less important, the absence of volatile alkaline elements (Na,K), which are present in KNN (sodium potassium niobate-based systems) allows better control of the stoichiometry chosen at the design stage [3].

However, likewise other lead-free alternatives ((K,Na)NbO3, KNN; (Bi,Na,Ba)TiO3, BNBT), its industrial scalability has been affected by the non-guaranteed reproducibility and the high processing costs, consequence of the complexity of the systems and the lack of critical knowledge at the early stages of their development [10–13]. Control and optimization of the solid-state route is then necessary for reducing the expensive treatments required for the synthesis (up to 1300°C) and sintering (up to 1550°C) steps of the BCZT-based systems. At the same time, it is essential to know the mechanisms which are at the basis of the piezoelectricity of the specific system to assure high electromechanical performance.

With respect to the past and current literature, the present review aims to introduce a critical overview of the BCZT-based systems prepared by solid-state route. At first instance, the intrinsic and extrinsic contributions to piezoelectricity in the BCZT system will be presented. Then, the methodological aspects related to the solid-state route, with a particular focus on the mechanical activation techniques, will be detailed. Finally, the toxicity evaluation of the BCTZ systems and the new emerging applications in the biomedical field, will be discussed.

Over the last decade, several reviews on BCZT-based ceramics have been reported [1,6,9,14–17]. However, a focused review on the influence of the ball milling parameters (vessel materials, ball-to-powder ratio, ball-milling apparatus used and rotation/vibration frequencies, etc.) and the processing parameters that could lead to a variation of the synthesis/sintering temperatures is still lacking.

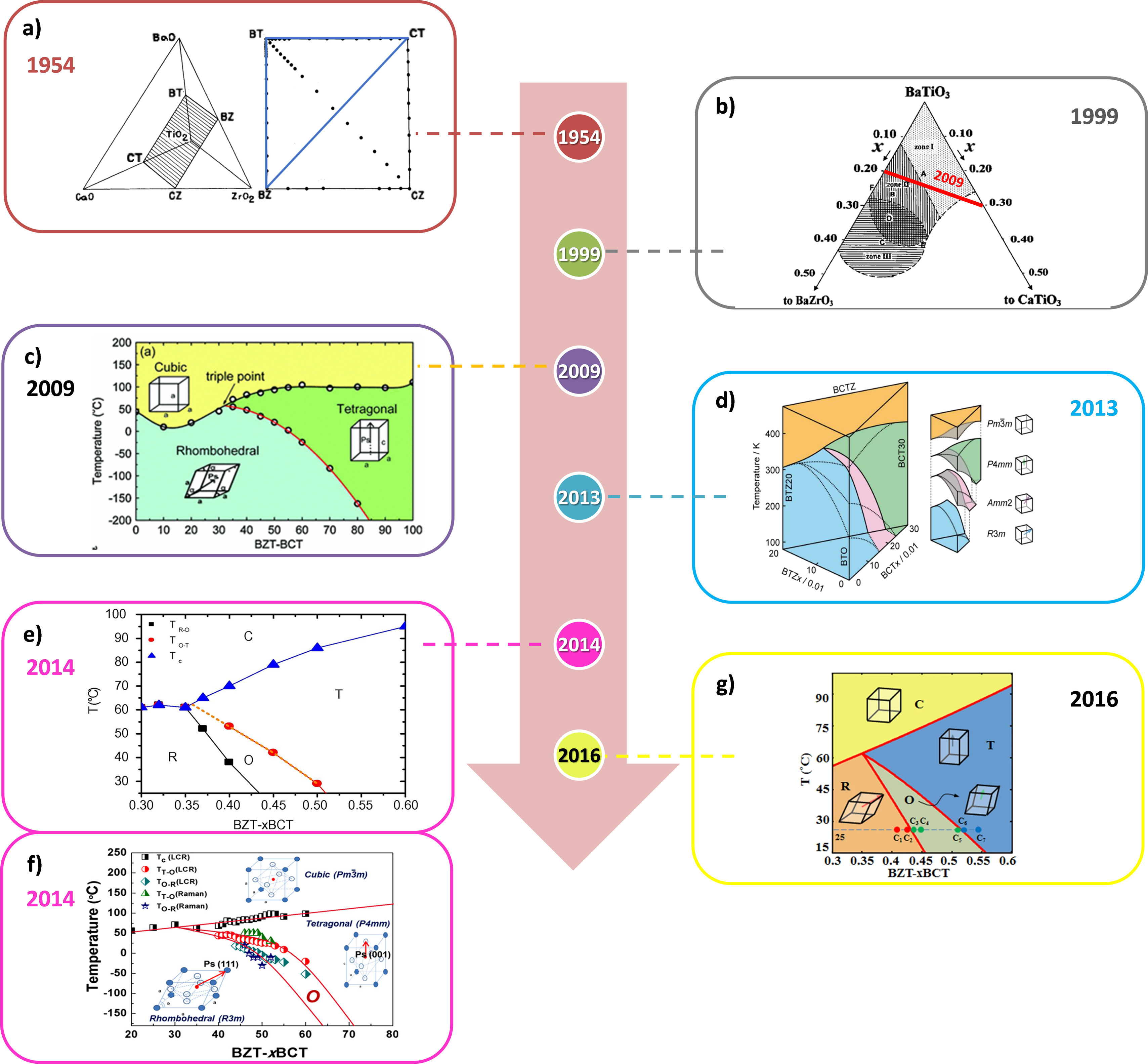

FundamentalsHistorical overview of the phase diagramAlthough the most influential manuscript on their piezoelectricity by Liu and Ren [8], was published in the early 2000s, BCZT ceramics were first studied in 1954, when McQuarrie and Behnke reported for the first time the baria–calcia–titania–zirconia tetrahedron phase diagram [18]. It was during the age of the explosive development of ferroelectric oxide ceramics that followed the discovery of the ferroelectricity of barium titanate [19] and that lead as well to the development of lead titanate zirconate (PZT), which is, so far, the market leading piezoelectric ceramic. BCZT was first studied as a relevant system for capacitor applications at the time and have been studied as such ever since. A planar square section was extracted from this solid-solution system, showing at the corners the composition of barium titanate (BT), barium zirconate (BZ), calcium titanate (CT) and calcium zirconate (CZ), respectively (Fig. 2). It should be noted that the materials, weighed in the desired proportions, were pre-processed by wet grinding. This seminal work shows that authors inspected the variation of lattice constants for the pseudo-binary composition along the four edges [18]. The near-edge of BaTiO3–BaZrO3 and CaTiO3–CaZrO3 compositions shows evidence of a complete formation of a solid solution, whereas all intermediate compositions contained two separate phases. In particular, the crystalline phases of the (Ba1−xCax)(Ti1−yZry)O3 system, and their lattice parameters identified from the X-ray powder patterns of the fired ceramic discs were determined. The values of the lattice constants along the different sides of the square composition showed marked deviations from Vegard's law indicating site occupancy changes at some points [20] especially in the corner of the barium zirconate. However, variations of Curie point temperature and ageing rate correlated reasonably well with changes in the character of the crystal structure [20].

Main milestones of the development of BCZT phase diagram (PD): (a) 1954: McQuarrie and Behnke reported for the very first time the baria–calcia–titania–zirconia composition tetrahedron showing the plane composition square of barium titanate (BT), barium zirconate (BZ), calcium titanate (CT) and calcium zirconate (CZ) [18]; (b) 1999: Ravez studied the pseudo-ternary PD (BT–BZ–CT) [29]; (c) 2009: Liu and Ren studied the PD of the pseudobinary ferroelectric BTZ20–xBC30T (BZT–xBCT), showing that, at the triple point, where there is a R–T–C phase coexistence, the piezoelectric properties are excellent [8]; (d) 2013: Keeble revised the PD of the BCZT solid-solutions using synchrotron XRD, including an orthorhombic phase [33]; (e) 2014: Acosta PD obtained from the peaks of the relative dielectric permittivity that confirmed the O/FE phase [35]; (f) simultaneous in 2014: Zhang updated the PD using Raman and permittivity results (the solid lines are a guide to the eyes) [43]; (g) 2016: Yang calculated the pseudo-binary PD of BZT–xBCT, which confirmed the experimentally obtained one; dots corresponds to the investigated following compositions: x=0.41000, 0.43360, 0.43450, 0.44750, 0.51905, 0.51913 and 0.55000 [38].

One year later, in 1955, this fervent activity of the two coexisting ternary systems, viz. the systems CaTiO3–BaTiO3–BaZrO3 and CaTiO3–CaZrO3–BaZrO3, was augmented by a study of the stability of materials with perovskite-like structure. The value of the Gibbs free energy, which determines the phase stability, was related to the degree to which the ions may or not fit into the perovskite lattice. After definition of a tolerance factor t for perovskite structure and taking the value |t−1| as a measure of the Gibbs free energy, then the most stable combination in the (Ba,Ca)(Ti,Zr)O3 system was found to be BaZrO3+CaTiO3[21]. Twenty and more years later (1977), the BCZT system subject was reconsidered by Hennings and Schreinemacher with a focus on the separated paraelectric phase of CaTiO3 that may influence the ferroelectric and dielectric properties of BCZT [22].

It was observed that the amount of secondary phase depends on the temperature of heat treatment and subsequent cooling rate. The authors suggested that the microstructure may affect the observed permittivity and reported also on the presence of contamination from milling tools. However, they could not establish any correlation between energy impacts and critical temperatures. It was also recommended to consider the effect of microstructure parameters, typically crystallite size and strain.

Interesting for the further development of ferro-piezoelectric compositions in the BCZT system are the initiation in the late fifties and early sixties of two separated lines of research of the dielectric properties in the BaTiO3–CaTiO3[23,24] and BaTiO3–BaZrO3[25–28] systems, respectively. These merged in the work by Ravez in 1999, in which, to summarize their findings, the authors drew the well-known quasi-ternary diagram BaZrO3–BaTiO3–CaTiO3[29]. This diagram could have inspired later work on the piezoelectricity of the BCZT system, specifically within the line of the solid solution system with end members (Ba0.70Ca0.30)TiO3 and Ba(Ti0.8Zr0.2)O3[21]. The optimum piezoelectric in this system is found for the composition 0.50(Ba0.7Ca0.3)TiO3–0.50Ba(Ti0.8Zr0.2)O3, which can also be rewritten as (Ba0.85Ca0.15)(Ti0.90Zr0.10)O3 and is commonly referred to as BCT–50BZT or, simply, BCZT. However, many other interesting compositions have also been studied outside this specific line of the ternary diagram [30].

Simultaneously, following the parallel research line of thin films, in 1999 Toyoda and Lubis reported the synthesis of thin films of nominal composition (Ba0.92Ca0.08)(Ti0.92Zr0.08)O3 (BC8TZ8) with single-phase perovskite structure with very good dielectric performances. For thin films heat-treated at 800°C, the value of the relative dielectric permittivity and dielectric loss, were ɛ=1200 and tan δ=0.005 respectively, and break-down voltage of 980V [31].

A few years later, Sen and Choudhary [32] performed the synthesis of polycrystalline powders of (Ba1−xCax)(Zr0.05Ti0.95)O3 (BCxTZ5) with compositions for x=0, 0.03, 0.06 and 0.09. Detailed studies of dielectric parameters as a function of temperature at 10kHz suggested that the substitution of Ca2+ ion at the Ba-site and Zr4+ at Ti-site has a strong effect on the dielectric properties of BaTiO3. It was reported that the rhombohedral (R)–tetragonal (T) structure of BaTiO3 can be changed to orthorhombic (O) structure by doping. Preliminary X-ray diffraction results suggested that R–T tetragonal structure of BaTiO3 can be changed to orthorhombic by doping, but the evidence provided remains questionable [32].

As mentioned above, the breakthrough article for the zBC30T–(1−z)BTZ20 system, hereinafter called “BCZT system”, was the 2009 article by Liu and Ren [8] which boosted considerably the interest in this system thanks to the surprisingly large quasi-static charge piezoelectric coefficient d33 ≈620pC/N reported at the optimal composition (for 50BC30T–50BTZ20 or BC15TZ10, hereinafter called “BCZT composition”). The phase diagram of the pseudo-binary ferro-piezoelectric system was constructed and the evaluation of the dielectric permittivity (ɛ) versus temperature curves (T) was reported. The structures of different phases were assessed by X-ray diffraction. The phase diagram turned out to be characterized by a so called morphotropic phase boundary (MPB) separating a ferroelectric rhombohedral R−3m (BZT side) and tetragonal P4mm (BCT side) phases. The most important feature of this BCZT system, is the existence of a cubic (C)–rhombohedral–tetragonal triple point in the phase diagram located at x≈32% and at T=57°C. According to the authors, the high piezoelectricity of the MPB compositions stems from the proximity to the critical triple point. Therefore, when a suitable tri-critical point type MPB is designed, lead-free systems may exhibit equally excellent or even better piezoelectricity at RT than those Pb-based [8].

Following this important report, other authors attempted to reproduce and detail the phase diagram with high resolution. Keeble et al. reinvestigated this BCZT system using high-resolution synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) [33]. Contrary to previous reports of unusual rhombohedral-tetragonal phase transition, they observed an intermediate orthorhombic (O) Amm2 phase, isostructural to that present in the parent phase, BaTiO3, and a T–O transition was identified. They also reported the O–R transition coalescing with the previously observed triple point, forming a phase convergence region [33]. It was also demonstrated that Ca off-centering plays a critical role in stabilizing the ferroelectric phase and tuning the polarization state in the (Ba1−xCax)(Zr0.1Ti0.9)O3 with x≈0.10–0.18 compositions. The Ca off-centering effect drives to shift the R–O and O–T phase boundaries to room temperature, leading to the occurrence of electromechanical coupling factors at RT in the system over a large composition range, which are comparable to those of PZT [34].

Nevertheless, Acosta et al. (2014) reported a detailed compositional study of the mentioned BCZT system with z=0.30, 0.32, 0.35, 0.37, 0.40, 0.45, 0.50 and 0.60 analysing dielectric, small signal d33 and large signal d33 properties as functions of temperature. The methodology employed allowed a complete assessment of the role of the convergence region on the electromechanical properties. The authors posed the question whether the convergence region is responsible for the outstanding electromechanical properties rather this is related to the R-ferroelectric/T-ferroelectric phase transitions in the system previously denominated as MPB. They concluded that the highest piezoelectric coefficients occur at R–O and O–T ferroelectric–ferroelectric phase transitions and are rather small at the phase convergence region. Nonetheless, from the data scattering it seems likely that the orthorhombic equilibrium line is merging with the tetragonal making a triple point below the equilibrium line with the cubic phase, since four phases cannot exist simultaneously in a composition vs T diagram at constant pressure. This behaviour is attributed to the low spontaneous polarization related to the small distortion of the cubic perovskite at the phase convergence region [35].

Soon after, other authors analysed the RT coexistence of phases as well as the electric field driven transformation from tetragonal to orthorhombic and to rhombohedral transformation, both by XRD [36] and in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [37]. Later, Yang et al. (2016) reconstructed theoretically this BCZT system diagram by formulating a generic sixth-order Landau free energy polynomial showing a good agreement with the experimentally measured one, confirming the presence of the orthorhombic region [38].

After all these interesting studies, another key unresolved point is the presence of a monoclinic (M) phase, already observed for the PZT system, as remarked by Cordero in his review on the factors that promote the piezoelectric effect. Indeed, analysing the relationship between the crystalline systems from a crystallographic point of view, it should be noticed the presence of a monoclinic phase transition between the rhombohedral and orthorhombic phases, as suggested for pure BaTiO3. This phase appears to be an adaptive nanotwinned tetragonal/pseudo-orthorhombic phase. Furthermore, this M-bridge phase would allow for a better accommodation between the O and T domains [39].

Theoretical work soon confirmed the existence of these phases in the BCZT composition using a large-scale atomistic scheme [40]. Besides, Liu et al. [41] constructed the three-dimensional compositional phase diagrams for this BCZT system, for the relative energies per unit cell, the lattice constants, the cell volumes and the band gaps, as functions of the Ca (up to x=0.20) and Zr (up to y=1.00) amounts by first-principles calculations and Landau–Devonshire theory. The authors claimed that the energy and structural parameters of the C, T, O, and R phases of BCZT become smaller on increasing the Zr content, and the four phases eventually merge into a multiphase condition with coexisting cubic structures under Zr-rich conditions, indicating a phase transition from normal to relaxor ferroelectrics, characterized by ferroelectric microdomains and nanodomains, respectively, in agreement with experimental observations [25–28].

Similar to previous studies on the BCZT composition using dielectric or Raman spectroscopy versus temperature measurements, or in combination with other techniques [36,42–44], Aredes and colleagues [45] used a multi-technique approach to investigate the temperature-induced phase transitions and phase coexistence in ceramics of 0.44(Ba0.70Ca0.30)TiO3–0.66Ba(Zr0.20Ti0.80)O3 (44BC30T–66BTZ20) composition. Results showed that this composition presents also three-phase transitions at temperatures of 11, 41 and 84°C, respectively. The evidence from this study suggested that such composition presents the coexistence of the tetragonal and orthorhombic phases in the temperature range from 41 to 71°C. Because of all these studies, the orthorhombic phase nowadays is considered well documented.

To conclude, (Ba,Ca)(Ti,Zr)O3 solid solutions were inspected by various authors using both experimental diffraction studies (mainly by X-rays) and numerical modelling techniques based on free energy curves calculations [33,35,43]. The literature seems to converge reporting binary composition vs. temperature phase diagrams at constant pressure with a singular point. However, the point with four phases in equilibrium may be controversial, as it breaks the general Gibbs phase rule. Assessing this particular issue from an experimental point of view is very hard considering the close similarity of distorted perovskite structures. This requires further deepening inspections clarifying the resolution limits of instrumentation adopted. We list the careful determination of lattice parameters, the necessity of working with microcrystalline powders large enough to avoid significant peak broadening effects applying Rietveld modelling of the phases especially for the high angle (or equivalently qhkl) peaks. These are trusted the most significant in order distortion effects attributable to R, T and O structures vs composition. Unfortunately, such high-angle peak shapes are biased to a certain extent because of their low intensity. On the other hand, similar to the experimental limitations, even the numerical modelling approaches suffer for insufficient accuracy in evaluation of the separating equilibrium curves and extrapolation procedures. In this context, we believe there is room for further research in order to overcome the perplexities so far enounced. To summarize, the historical evolution of the BCZT phase diagram is presented in Fig. 2.

Overview of the pseudo morphotropic phase boundary (MPB)The enhancement of the complex piezoelectric phenomenon in piezoceramics is essentially related to two main contributions [46]. The intrinsic one is represented by the effect of the electric field on the crystalline lattice, which requires the presence of non-centrosymmetric distortion of the crystal lattice (ferroelectric spontaneous polarization) and it is affected by dopants, crystalline defects, phase coexistence at the MPB, FE-FE phase transitions and the working temperature with respect to the FE-PE transition at the Curie Point. It is also affected by the field-induced transitions between polymorphs with distinct lattice distortion (such as polarization clock-like rotations between allowed crystal directions and polarization extension). The extrinsic contribution is mainly represented by the domains movement that depends also on the ceramic microstructure (grain size determining the domain size, density and porosity determining intergranular stresses) [47].

Considering the intrinsic factors, one of the key points is represented by the effective coexistence of one or more phases in a compositionally dependent, given region of the phase diagram, usually called morphotropic phase boundary (MPB). In fact, the classical approach to achieve high piezoelectricity is to place the composition of such solid solutions in the proximity of a multi-phase coexistence range or MPB, where the polarization direction can be easily rotated by an external stress or an electric field, resulting in a high piezoelectric and dielectric response [48]. So, if there are two or more polymorphs there is the possibility to have more polarization directions permitted. In this way, under and external field the polarization direction can easily assume more allowed directions close to that of the field [39].

Before discussing the characteristics of MPB in the BCZT system, it is essential to clarify the nomenclature used in the literature as it is substantive and not just formal. With specific reference to the BCZT phase diagram, unlike PZT, the MPB is not normal to the x-axis (Fig. 2), being strongly dependent on the temperature. For this the region of the phase diagram of the system, it is more appropriated to call it “Polymorphic phase boundary” [49–52], though it is reported also as “conventional MPB” [35,48,53–57] and “thermotropic phase boundary” (TPB) [39]. Furthermore, another term has been found for this system, the “multiphase coexistence point” (MPC), which is not only a point where the ferroelectric (R, O, T) phase and the paraelectric (C) phase coexist but, is a point where no energy barrier exists between the three polymorphs. In this sense, some interesting studies report a correlation between free energy ΔG and spontaneous polarization of a given polymorph, P, showing the reduction in the height of the energy barrier at this tricritical point (TCP), described as isotropic free energy surface for TCP [8]. As reported by Damjanovic and Rossetti, the rotation mechanism is associated with a reduction in the crystallographic anisotropy of polarization taking place at the MPB or TCP and the weakening of first-order phase transitions from paraelectric to ferroelectric [31]. This was also commented by Cordero, who underlined that at the TCP the thermal hysteresis of all these transitions vanishes, indicating that the free energy is particularly flat for both changes of the magnitude and orientation of the polarization [39]. Considering the polarization anisotropy (P), the correct reproduction of ferroelectric phases with different symmetries implies the introduction of anisotropic free energy expansion terms.

This means that, at the MPC, there is no energy barrier between the four phases. This situation corresponds to a flat or pan-shaped free energy landscape, as shown in the temperature phase diagram and Gibbs free energy profiles for PZT (Fig. 3a) [58], also reported in Fig. 3b, that shows that the minima of G (P) depend on βan for P|| {100}, {110} and {111} and the angular plots of min G. When βan >0, the absolute minima are along {100}, reproducing the T phase, whereas for βan <0 the absolute minima are along {111}, characteristic of the R phase. When more phases coexist, in the intermediate situation, at MPB, βan=0 is isotropic [39]. The coexistence of several phases differentiates the generic BZT-BCT systems from other BT-based systems and thus provides an explanation for the high piezoelectricity for a particular composition [59]. Although Acosta et al. provided a key study on the anisotropy energy of a sixth-order Landau potential for the BZT–xBCT system, underlining that the anisotropy energy approaches zero near the O–R rather than near the T–O phase boundary, the quantification of the degree of flatness of a free energy landscape in terms of its relation to the polarization anisotropy was still unclear [35]. Later, Yang et al. [38] tried to shed light on this open topic formulating a theoretical study in which a generic sixth-order Landau free energy polynomial was used (Fig. 3c). They concluded by affirming that the energy differences (energy barrier EBs) between the stable phase and the saddle point on the minimum energy pathway (MEP), reported as EBs and MEP, are the lowest for domain switching and polarization rotation at the T–O phase boundary. This theory is in agreement with the experimental observations of the highest piezoelectricity and highest elastic compliance for this region (reported by Cordero [39]) and shown in Fig. 3d. This study suggests that the EB can be an effective technique for measuring the degree of polarization anisotropy and the piezoelectric property of a ferroelectric system [38].

Relevant studies concerning the MPB and PPT in PZT and BCZT. (a) Composition-temperature phase diagram for PZT and Gibbs free energy profiles [58]. (b) A representation of loss of anisotropy of the spontaneous polarization in the PZT system as a function of the increase of Ti content at the MPB. The R phase obtained with βan <0 changes into T obtained with βan >0. (c) On the left: energy surfaces of selected compositions; on the right: the corresponding energy profiles intersected by the (110) C plane; bottom image: distribution of energy barrier superimposed on the computed pseudo-binary phase diagram of BZT–xBCT [38]. (d) Comparison between the elastic compliances of BCTZ and PZT and paths followed in the respective phase diagrams [39].

To summarize, the piezoelectricity is promoted by the presence of a commonly called MPB in synergic action with the elastic compliance that allow for the optimal domain orientation during the poling process thanks to the presence of a larger number of thermodynamically equivalent states, represented by the oriented dipolar sites inside the unit cells, as well accepted for PZT system [60].

Solid-state route as a straightforward method to produce BCZT-based piezoceramicsAccurate choice of reagents and industrial scalabilityWith regard to the raw materials that can be used for the synthesis of ceramic materials, a reference must be made to the European list of the so-called critical raw materials and the criteria for determining whether an element or rare earth can be considered as such [61,62]. In order to define a profile for each raw material, the Directorate-General (DG) Joint Research Centre (JRC) in cooperation with the DG for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (GROWTH) have elaborated The European Commission's (EC) Raw Materials Information System (RMIS) to monitor trends in real time [63].

An important but underestimated aspect that can have an influence on the overall processing route is the choice of precursors. In their seminal work, Liu and Ren used BaZrO3 instead of ZrO2[8]. This aspect has been recently taken into account by Amorin et al. [64] who underlined that the amorphization of monoclinic ZrO2 has been found to be the limiting step for the formation of pure BCZT perovskite by mechanosynthesis. Substituting monoclinic polymorph with BaZrO3 as raw material can enhance the reaction kinetic, that can be further promoted by the use of tetragonal ZrO2[64].

Analysing the influence of TiO2 polymorph, Chao et al. demonstrated that using anatase (D50=532nm, 99.99%) or rutile (D50=614nm, 99.99%) TiO2 type modifies the microstructure and electromechanical properties of BZT–50BCT. The introduction of the rutile allotrope seems to increase the grains size from about 5–10μm to 10–20μm and, consequently, several properties such as d33=590pC/N, Kp=0.46, ɛr=2810, tan δ=0.014, resulted significantly improved. On the other hand, it has not influence on Tc and coercive field [65].

In their study on BCZT biocompatibility, Poon et al. found the relationship between the purity of the BaCO3 used and the resulting grain size, as they obtained 10±2μm for ≥99% purity, and 35±8μm for ≥99.98%. The authors concluded that, by increasing the BaCO3 chemical purity, the grain growth is promoted, leading to enhanced properties [66].

Another preliminary study reports the synthesis of BCZT powder starting from CaZrO3 (CZ) previously prepared using ultra-fine CaCO3. According to the authors’ findings, fine CZ powder enhanced the reaction of BaTiO3(BT) and CZ [67].

Another aspect to consider is the processing of the material in terms of industrial scalability (costs, CO2 emissions, availability and transport of raw materials, processing temperatures) and the possibility of transferring basic research into real applications, depending on the material properties [68].

Concerning the properties, reproducibility is strongly affected by the processing route and still represents a significant issue in lead-free systems, as they are complex ferroelectrics polycrystals.

The role of the mechanical activation of powders via ball-millingSolid-state chemistry in perovskite systems has been increasingly involved with disordered and complex systems (e.g., deviation from stoichiometry). Specifically, non-stoichiometry in perovskite oxides and related structures (that includes transition metal oxides) are of special interest not only for the diversity of the crystallographic features, but, also, to their relevant impact on different physical properties. In the search for an optimum stoichiometry control in developing polar electroceramics, softer conditions based on wet chemistry methods have been employed [69]. These include several methods for the synthesis of different type of lead-free ceramics. In particular, for the synthesis of BCZT ceramics and films are employed rather than traditional oxide reactions: sol–gel [70–74], glycine co-precipitation [75], Pechini modified reaction [76], auto-combustion [77], hydrothermal [55,78,79] or modified by introducing the use of different chelants, such as citric acid [80].

Moreover, the use of a combined synthesis route, such as the microwave-assisted hydrothermal method, offers many advantages: short reaction times, low synthesis temperature, and small and homogeneous grain size [81–83]. On the other hand, the grain sizes of ceramics obtained from powders processed by using these approaches, resulted excessively small, making them not suitable for polarization when DC electric filed is applied. A significant reduction for both ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties has been observed for systems obtained by sol–gel methods and characterized by a grain size of 1.5μm [84].

Recently, it has been demonstrated that a grain size in the range of 1–5μm, obtained through a combination of mechanosynthesis and spark-plasma-sintering (SPS), allows maintaining high electromechanical properties [85]. Furthermore, if on the one hand, the BCZT systems prepared by wet chemistry approaches are characterized by a homogenous distribution of particles sizes and lower processing temperatures, on the other hand, the reaction efficiency (very low synthesis yields), remains its major drawback for industrial scalability. For this reason, the solid-state route (SSR), schematically represented in Fig. 4, is still the most used and useful method to produce oxide ceramics on a large scale. Firstly, the precursors are weighted in stoichiometry proportions according to the composition chosen, then annealed to form a different new solid compound, step commonly called “synthesis” or “calcination”. To obtain dense materials, the powder particles are commonly pressed, also they can be shaped by casting or extruded, through a process called “forming” or “moulding”. The as-obtained green body is heated at higher temperatures to obtain dense ceramic bodies. Two intermediate ball-milling steps are introduced for homogenizing/activating the mixture and for decreasing the particle size of the calcined powder. However, the critical dependence of the synthetic powder and ceramics on the synthesis and sintering conditions is identified as a drawback for their processing.

In the ball-milling (BM) technique, the container – vial or vessel – is usually filled with powders and milling tools (grinding media) in an appropriate mass or volume ratio, using commonly a liquid media. Vial, balls and powder are moved by an electric motor with a fixed or variable velocity, allowing milling tools to collide with each other, with the powders and with the walls of the vessel. The intensity of each collision, which depends on the ball size and material (density), milling speed and ball-to-powder volume/weight ratio, can be sufficient to induce particles mixing and particles size reduction accompanied by several structural and microstructural modifications [86]. Furthermore, grinding leads to the generation of fresh surfaces and defects which significantly increases the overall reactivity of the system [87–89]. The mechanical treatment of powders by ball milling (BM) has rapidly become one of the most extensively powder processing methods used to activate the synthesis and, even, to produce the desired compositions from stoichiometric mixtures of reactants just by milling (mechanical alloying or mechanosynthesis), reducing the synthesis temperature [90].

Hence, the BM technique, is expected to have an influence on the intrinsic piezoelectric contribution via its effect on the lattice distortion and solubility limits of the precursors. This could lead to a variation in the number and amount (weight/volume percentage) after the heat treatment and, subsequently, on the temperatures at which they form, and, finally, on the ceramic microstructure, so having an influence also on the piezoelectricity [54,57].

In the current literature, several types of high-energy ball milling equipment have been exploited to produce BCZT ceramic. They differ in the main types of collisions produced, milling intensity (balls speed) and milling tools (materials and sizes). Principally, SPEX shaker mills (3D-vibratory mills), attritor mills and planetary ball mills, reported in Fig. 5 represent the most popular and conventional ball-milling apparatus for BCZT processing of ceramics by solid state route. A detailed description of these different mills is available in a key work [91]. Another main aspect is the material used for the milling vial and balls, because during the collisions of the milling tools and powder, and the collisions of these with the inner walls of the vial, some material could be incorporated into the powders, modifying their initial stoichiometry. Hardened stainless steel, zirconia and tungsten carbide are the most common types of materials used for the vials and milling tools. Vial and balls made of polymers-based materials (teflon, polycarbonates, etc.) are, only recently, exploited for producing ceramics. In this perspective, the next paragraphs aim at elucidating how the several grinding parameters, among them, variety of vials and balls materials, milling speed and time, impact energy (if estimable), kind of milling apparatus, ball to powder ratio (BPR), milling atmosphere and liquid medium, can play a crucial role into the processing of BCZT ceramics [92,93] and other systems [94]. Furthermore, the purpose is also to highlight which issues can be encountered when using this well-established method, drawbacks that can strongly affect the electromechanical properties of the final as processed piezoceramic.

High energy ball-milling methods and setups reported in the literature for processing BCZT ceramics. The blue arrows indicate the types of movement of the milling media (balls) and the powder to be milled, as well as of the vessels, which is also indicated by black arrows in the images of the vessels. The vessel is stationary only at attrition ball milling, where the revolving arms provokes spinning of the powder and balls that gives place to a massive number of shear forces. In the shaker-type milling the vessel describes a complex movement involving vibration in three dimensions. In the planetary milling, the vessels rotate on the top of a disk and around its own cylinder axis, resembling the movement of the planets around the sun. The impacts between particles and balls and/or inner walls of the vessel can cause compression forces or shear forces depending on the angle of the impact. The upper part of the figure shows the effect of the two main types of impacts on the powder particles. The main milling parameters affecting the characteristics of the milled powder are also indicated in the upper part. The lower part of the figure depicts the relative movements of the powder particles and the balls, as well as the main types of forces on the powder arising from the impacts for each milling method. For efficient milling, all types of impacts and related effects must be present and all three methods fulfil this criteria [95].

In a typical synthetic protocol of BCZT, once the nominal composition is defined, an appropriate milling setup has to be selected in order to efficiently activate the starting reagents [87]. In this step, it is strictly important to limit, as much as possible, any contamination coming from the vial and balls materials. In fact, the involuntary introduction of foreign ions could have an effect similar to that of doping (lowering or raising the Curie Point, alteration of the chosen stoichiometry, formation of unwanted secondary phases). Even though the BCZT system does not contain volatile elements, the desired stoichiometry can be altered if other elements are introduced during the processing steps of the solid-state route (SSR) [15]. This aspect was already explored in the late 1990s by Cousin and Ross for the preparation of titanates and aluminates through mixed powders, co-precipitation and sol–gel techniques. In this work, they concluded that the most direct method for preparing these compounds is the reaction of a mixture of metal oxides, paying attention to particle size growth while avoiding contamination of the grinding media and ensuring the homogeneity and purity of the powder [96]. Thakur and collaborators studied the influence of attrition ball-milling and the contamination of the powder due to the milling media (yttria-stabilized zirconia) on the electrical properties of undoped BaTiO3. They reported that the variation in lattice parameter, polymorphic phase transitions and changes in dielectric properties. For less than 2h of attrition ball-milling, the reduction in Curie temperature can be explained by the non-intended Zr-doping in Ti-site (5at.%). After 3h of attrition ball-milling, the Curie Point decreases from 135°C for undoped BT to 100°C, showing a ferroelectric relaxor behaviour, whereas the increasing in bulk conductivity can be explained by unintentional donor-doping from the milling media (in this case, Y3+ on the Ba-site) [97].

Since the BCZT contains zirconium, it is not surprising that in the current literature the milling process is usually performed using zirconia balls [98], and vials [45,99,100]. Recently, mechanochemical reactors internally covered with Teflon™ (polytetrafluoroethylene, PTFE) [92,101] and Nylon [35] have been successfully used avoiding most of the contaminants above reported. Of course, the level of contamination depends on the ball-milling parameters, precursors and time since absence of contamination has been reported for the mechanosynthesis of BCZT in tungsten carbide grinding media for 15h of ball-milling [64,102].

Since ball milling technique allows to modulate particles size and final ceramic grain size, its utilization has a profound effect on the electromechanical properties of BCZT. First of all, a distinction must be made between the activation of precursors prior to calcination and the destruction of agglomerates formed at this step prior to the sintering (Fig. 4).

Depending on the milling conditions, the mechanical treatment can induce different modifications on the precursor and create an intimate mixture [103], enhancing their reactivity [92,104], and, eventually, also leading to the final product (mechanosynthesis) avoiding the calcination step [64].

Regarding this, different ball-milling apparatuses are used, such as [105]: attrition ball-mills [92,101,106,107], planetary mills [64,108–111], horizontal attrition ball-mills [103] and shaker ball mills [112]. Concerning the grinding media materials, the reactants for the preparation of BCZT are also mechanically processed using WC [64,102,113,114] and agate [53].

First ball-milling and calcination temperatureAlthough it is known that particle size reduction and precursor homogenization lead to a decrease in the synthesis temperature, at the current state of the art, the correlation between the mechanical activation of powders and the reduction in calcination temperature is poorly studied. In this regard, Frattini and coauthors evidenced the influence of calcination temperature (800–1200°C), on precursors previously milled using a planetary ball milling for 4h zirconia media into a zirconia jar. They underlined that BCZT pure phase was obtained only above 1100°C. In this work, the authors also reported in detail the secondary phases that can occur as a function of the calcination temperature (BaZrO3, CaZrO3) [108]. In a recent interesting work of Ciomaga and colleagues, it is pointed out how ball-milling conditions and synthesis temperatures can affect the final properties of ceramics keeping all other processing steps fixed. The best properties (compromise between good piezoelectric properties and low losses) were obtained by using a vibratory ball-milling apparatus for 60min (d33=280pC/N). The processing method used leads to the achievement of ferroelectric phase coexistence (MPB) in the final ceramic with majoritarian orthorhombic phase (O>T) [115]. Although this is not explored in depth, fairly low synthesis temperatures are reported in the literature, such as 1150°C/2h for powders milled for 2h with SPEX 8000 [112]. Bai et al. reported the calcination temperature of 1000°C/4h for the BCZT–Bi(Mg0.5Ti0.5)O3 composition, milled for 24h in a planetary mill [116]. In another work Bai and colleagues report a low synthesis temperature of 1100°C for 4h after horizontal ball milling in distilled water with zirconia balls, not analysing neither particles size nor the effect of water on precursors, but performing a study on the effect of second ball-milling on the final microstructure [103]. Nan et al. used a low temperature specifying the milling conditions. They employed an attrition ball milling apparatus using ethanol as medium (zirconia balls with 3mm diameter and the ball-to-powder ratio 1.5:1) for 2.5h at the rate of 700rpm. The powder mixture was calcined at 1100°C for 4h obtaining pure BCZT system [92,101,106].

As emerged from Table 1, despite the high energy mechanical processing to activate the precursors, the calcination temperature resulted too high (≥1000°C) when compared with wet-chemical approaches already mentioned. According to the specific literature, to trigger any physical and chemical modifications, a threshold dose of kinetic energy has to be transferred, which mainly depends on the mass of each ball and milling velocity. The apparatus type and the frequency of milling indicated in Table 1 for each composition, reveal that the powders have been subjected to impact of energy in the range of 8×10−3–0.1J, 2×10−3–1×10−2J, 1×10−3J–0.2J, for shaker, planetary and vibratory mills, respectively. These values have been estimated also taking into in account different mass of balls and the equations applied in these manuscripts [117–120]. On the other hand, the use of attrition ball milling has allowed the use of ultra-low synthesis and sintering temperatures [92] and even using water as liquid media [101].

Ball milling apparatuses, working conditions of milling, calcination and sintering steps of the BCZT processing and the corresponding physical and electrical parameters of the BCZT ceramics obtained. These works have been selected among the most interesting studies on mechanical activation of precursors by ball-milling.

| Composition | BM-a | t (min)f (Hz) | Tcalc (°C)Dtime (h) | CLBCZT | SP | M | Tsint (°C)Dtime (h) | TmT0–Tcw(°C) | ρ(%) | G.S.(μm) | CLBCZT | d33(pC/N) | kp–Qm | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC15TZ10 | P | 305.8 | 10004 | T>O | BZ | HYP | 14502 | 9392 | 76 | 20 | T>O | 180 | – | [115] |

| BC15TZ10 | V | 3030 | 10004 | T–O | BZ | HYP | 14502 | 9387 | 96 | – | O>T | 230 | – | [115] |

| BC15TZ10 | V | 6030 | 10004 | T>O | BZ | HYP | 14502 | 8788 | 95 | – | O>T | 280 | – | [115] |

| BC15TZ10 | P | 305.8 | 1200/135024/6 | T>O | – | SPSSPS | 130010 | 10397 | 97 | – | O>T | 283 | – | [115] |

| BC15TZ10 | S | 12014.6 | 11504 | – | – | UXHP | 15006 | 7185 | 9498 | 1020 | – | 350510 | 33–8044–66 | [112] |

| BC11TZ10 | P | 2405.8 | 900/1200 | – | BZ | UX | 14002 | – | 5–15 | – | – | – | [108] | |

| BC8TZ5 | A | 36011.67 | 7002 | T | CT | UX | 12802 | – | 87 | 10 | T | 320 | 32–163 | [101] |

| BC8TZ5 | A | 36011.67 | 7002 | T | CT | UX | 12806 | – | 80 | 10 | T | 455 | 35–155 | [92] |

BM-a: ball milling apparatus; P: planetary mill; V: vibratory mill; S: shaker mill (Spex); A: attrition ball miling; t: ball milling time; f: ball milling frequency; Tcalc: temperature of calcination; Dtime: dwell time refereed to the calcination step; CLBCZT: crystal phase of BCZT obtained after calcination; SP: secondary phases after calcination; BZ: BaZrO3; CT: CaTiO3; M: moulding method; UX: uniaxial; HP: hot-pressing; HYP: hydrostatic pressing; Tsint: temperature of sintering; Dtime: dwell time referred to the sintering step; Tm: transition temperature corresponding to maximum of permittivity; T0 and Tcw: the result of the fitting with Curie–Weiss and Curie–Weiss-modified laws; ρ (%): relative density of the sintered pellet; G.S.: grains size; d33: quasi-static piezoelectric coefficient; CLBCZT: crystal phase of the sintered BCZT; kp/Qm: electromechanical coupling coefficient and mechanical losses; T: tetragonal; O: orthorhombic.

Another important point is represented by the need of a second ball-milling before sintering so that the agglomerates formed during calcination are broken up, step well described and studied for other systems like KNN [92,111,121,122]. Additionally, it has been known since the beginning of the sintering science that increasing the concentration of defects in the crystal lattice can significantly improve the densification rate and ultimate density of ceramic compacts made from crystalline powders, including the single oxides. This was customarily accomplished by milling the powder to be sintered [123].

Regarding the BCZT system, Yan et al., investigated the effect of post-calcined dry ball milling treatment on BCZ–60 BCT (Ba0.82Ca0.18)(Ti0.92Zr0.08)O3 powder using a Fritsch Pulverisette 7 planetary ball-milling and 45-mL zirconia vial and zirconia balls as grinding media for increasing milling time (0–40min, at 600rpm, BPR 25:1). They obtained a significant reduction of the particle sizes starting from an irregular morphology of 1μm to achieve regular shaped particles of 3.8×10−3μm just after 10minutes of milling processing. For further increasing milling time, particles become more uniform, but agglomeration can be noticed. They conclude that the best dielectric and piezoelectric properties were reached for a grain size of 12.9μm obtained with the best combination of 30min of the second BM (2.4×10−3μm particle size) and an optimal inverse two step sintering method (1475°C/1300°C) [109]. The same was confirmed by Mittal et al. that used high-energy ball mill on calcined powders for obtaining good piezoceramics without creating any undesired secondary phase in its perovskite structure [111]. The authors declared that the key point is selecting adequate milling parameters. In this work, contrary to the previous one, they changed the ball-milling frequencies (100rpm, 150rpm, 200rpm, 250rpm, 300rpm and 350rpm) keeping the milling time fixed for 20h. The best d33 and kp have been reached by using a speed of 250rpm for an average particle size of 4×10−3μm as reported in Table 2.

Ball milling apparatuses, working conditions of milling, calcination and sintering steps of the BCZT processing and the corresponding physical and electrical parameters of the BCZT ceramics obtained. These works have been selected among the most interesting studies on mechanical activation of calcined powders by ball-milling.

| Composition | 1BM-a | BM-t (min)BM-f (Hz) | Tcalc(°C)Dtime (h) | 2BM-a | BM-t (min)BM-f (Hz) | M-binder | Tsint (°C)Dtime (h) | TmT0–Tcw(°C) | ρ(%) | G.S.(μm) | CLBCZT | d33(pC/N) | Kp | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (BZT–60BCT) BC01TZ08 | P | 6006.7 | 13503 | P | 0–4010 | –– | 1475–13000.02–6 | 105 | 94 | 13 | T–O | 330 | 40 | [109] |

| BC15TZ10 | P | 12001.7 | 12004 | P | 12004.16 | HYPPVA | 14504 | 79 | 94 | 3 | T | 210 | 22.4 | [111] |

| BC15TZ10 | H | 1440– | 11004 | V–P | –– | UXPVA | 14754 | 95 | 96 | 32 | T–O | 466 | – | [103] |

| BC15TZ10 | PLMDM | – | 13004 | PLMDM | 360– | –PVB | 14006 | 9640 | – | – | T | 38090 | [124] |

BM-a: ball milling apparatus (1BM: first ball milling. 2BM: second ball milling); P: planetary mill; A: attritor mill; H: horizontal mill; V: vibratory mill; LM: liquid milling; DM: dry milling; BM-t: ball milling time; BM-f: ball milling frequency; Tcalc: temperature of calcination; Dtime: dwell time refereed to the calcination step; CLBCZT: crystal phase of BCZT obtained after calcination; M: moulding method; UX: uniaxial; HP: hot-pressing; HYP: hydrostatic pressing; Tsint: temperature of sintering; Dtime: dwell time refereed to the sintering step; Tm: transition temperature corresponding to maximum of permittivity; T0 and Tcw: the result of the fitting with Curie–Weiss and Curie–Weiss-modified laws; ρ %: relative density of the sintered pellet; G.S.: grains size; d33: quasi-static piezoelectric coefficient; CLBCZT: crystal phase of the sintered BCZT; Kp: electromechanical coupling coefficient; T: tetragonal; O: orthorhombic.

An increase of the milling velocity induces a further decrease of particle sizes. In addition, by reducing the particle size to such a small scale, the surface area of the particles begins to dominate over the volume (increasing the specific surface energy), and, as a result, modifying its thermodynamic properties. To reach the equilibrium position, the particles begin to agglomerate, reducing the surface energy, which shows the agglomeration of particles in the powder milled at 300rpm [111]. In the investigation of Di Loreto et al. [125] on post-calcination grinding, the authors highlighted the influence of grinding intensity on BCZT powder, using zirconium balls (ball/powder weight ratio=10) for 6h. The comparison between liquid milling (LM) and dry milling (DM) showed that more energetic DM deteriorates the piezoelectric response: the d33 coefficient measured for the LM ceramic was 380pC/N, higher than that obtained for the DM sample (90pC/N). They also highlighted that Tc depends on the grinding process of the calcined powders, 40–50°C for the DM sample and 96°C for LM sample. They concluded that an intense degree of milling affects drastically the structural homogeneity. This occurs due to a mechanically activated phase decomposition process. They detected inhomogeneity in grains, resulting in BCZT grains, CaTiO3 nanocubes and an amorphous phase rich in Ba and Ti. The grinding intensity of calcined BCZT powders is a key parameter for obtaining proper sintered ceramics [124]. Nan et al. [109] considered the need of a second ball-milling to deagglomerate the powder. They treated the calcined powder with attrition ball milling (700rpm, 5h). They underlined that before being milled, the particle-size distribution exhibits three populations, including two main peaks, one centered at around 0.20μm, another small peak around 2.2μm, and a shoulder at ∼8μm corresponding to the coarser agglomerates, with D50=1.0μm and D90=4.6μm. After milling, the particle-size distribution exhibits a bimodal distribution with a main large peak centered at around 0.2μm and another small peak around 1.8μm, and with overall D50=0.17μm and D90=0.38μm. These results show that attrition milling is essential for achieving a homogeneous particle-size distribution by destroying the agglomerates [106]. Bai et al. used and horizontal ball milling with ZrO2 balls to yield a calcined powder with an average particle size (D50) of about 5μm. In order to obtain powders with different particle sizes so that their effects on material microstructures and piezoelectric properties could be investigated, vibratory milling and planetary milling were applied on portions of the calcined 5/5 BCZT powder, resulting in reductions in D50 to about 3μm and 1μm, respectively, leading to different grain size and relative density of the sintered ceramics [103].

The literature also contains works in which the authors employed high-energy ball milling techniques but treated the powders at high temperatures. Syal et al. used planetary ball milling (FRITSCH, P5) for 12h before synthesis (1350°C for 4h) and for 6h prior to the sintering (1565°C for 6h), obtaining good properties for BC15TZ10 composition (d33=512pC/N, kp=51%, Tc=104°C) [110]. In two investigations on the effect of the sintering dwell time, the authors reported the use of unspecified ball-milling in combination with high processing temperatures, 1350°C/2h for the synthesis and 1450°C and 1500°C for the sintering, respectively [125,126]. Other authors declare the use of ball-milling always using very high temperatures, 1200°C and 1350°C [127], long roll jar milling [66], attrition milling in combination with 1300°C and 1400°C as processing temperatures [107].

Up to this point, scarce literature is reported on the use of attrition ball-milling for activating the precursors and calcined powders in order to decrease the processing temperatures (calcination step and sintering step), allowing the industrial scalability [92].

Water-based solid-state routes: an urgent target for industrial scaling upAnalysing the literature, at research level the processing of BCZT precursors involves the use of organic solvents, such as isopropanol, ethanol [44,125,128], unspecified alcohol [107,110] and acetone [110]. At industrial scale, the introduction of organic solvents represents a limiting factor, due to economic, environmental, and safety reasons. In this context, the growing demand from industries for more ecological water-based routes is triggering the interest of researchers in the development of synthetic protocols based on solvent-free routes. Unfortunately, as properly reported in the literature, there are some issues that can be encountered when using water for processing ceramics: possible leaching of metal ions, deviations from the chosen composition due to the solubility of carbonates in water, formation of unwanted secondary phases, hydrolysis, demixing of the slurry due to the segregation of heavy elements as a function of the density during the slurry drying, interactions due to the high polarity of water. As remarked in an interesting review some approaches to overcome these drawbacks can be: adjustment of the pH value, or addition of surfactants, and the use of spray- or freeze-drying (lyophilization) [10,101]. So far, few articles on the use of distilled water for processing BCZT employing a horizontal ball-milling setup have been reported [103,129]. In this respect, Kaushal and colleagues, investigated the behaviour of BCZT untreated and di-hydrogen phosphate surface-treated powders in aqueous suspensions monitoring their pH value for 7 days. The authors concluded that in treated powders was detected a “negligible leaching of Ba2+, Ca2+, and Zr4+[130]. In a subsequent work, the same authors explored the possibility to produce micron-sized spherical granulates via freeze granulation in surface-treated BCZT, concluding that the green bodies obtained after this procedure demonstrated good sinterability and homogeneity [131]. In this respect, Acosta et al pointed out that in both works of Kaushal et al. the BCZT was actually obtained by a two-step calcination route with conventional ethanol processing [6].

Up to that point, the challenge of a totally aqueous-based processing of BCZT ceramics remains open. Furthermore, these authors did not report the piezoelectric properties of the final ceramics. However, they highlighted that processing strongly influenced the dielectric properties of the materials. It must be underlined that these results refer to ceramics obtained starting from calcined powders aged in water for 24h, step not usually performed for obtaining functional ceramics. This issue has been recently studied and a new sustainable water-based route was developed [101].

Biomedical applicationsOver the last decades, there has been a trend to expand the use of piezoelectric ceramics in new areas of biotechnology. The electricity has a vital role in living systems, as biological piezoelectricity, endogenous electric fields, transmembrane potentials that enhance cellular growth and differentiation. The biological piezoelectricity was firstly reported in 1941 in the wool by Martin [132]. In 1957, Fukada and Yasuda [133] reported the same behaviour in bone tissue. Then, endogenous electric fields have been discovered in cardiac and nerve tissue, demonstrating that electrophysiological microenvironment is essential for maintaining the normal physiological activities of the human body [134]. From this moment on, researchers have tried to reproduce these endogenous effects to repair tissues injuries as peripherical nerve and bones damages. In this context, piezoceramics can be promising for Tissue Engineering [135]. Thanks to the piezoelectric effect shown, they can promote cells adhesion and migration.

The two main features that a material must have to be employed in this field are biocompatibility and piezoelectricity. Due to the well-known toxicity of lead-based materials that provoke neurotoxicity, pregnancy complications, attention deficit hyperactivity and so on, new lead-free piezoceramics can be a promising alternative in this case [136,137]. In view of this, the BCZT system meets the requirements, i.e. a high d33 values and a theoretical good biocompatibility. Its main drawback is the relatively low Curie Point (∼100°C), which is still a tangible problem for technology transfer, as it reduces the operating temperature of out-of-body devices in general (sonar, sensors and so on). However, it is not a limitation for biomedical applications, and other new emerging innovative technologies, since under physiological conditions, the body temperature is about 35.5–37.5°C. With regard to the biocompatibility, a good compatibility of BCZT material with human osteoblast and endothelial cells has been demonstrated for the most studied BC15TZ10 composition [66]. The material seems promising for bone regeneration in combination with hydroxyapatite, as reported by Manohar et al. [138] (Fig. 6). Among other applications, outstanding importance can be attributed to BCZT thin films for biocompatible and flexible devices, such as BCZT-based coatings on Kapton substrate as a support for osteogenic differentiation, obtained by PLD (pulsed laser depositing) and MAPLE (matrix-assisted pulsed-laser evaporation) techniques [128]. In this sense, further progress has been made in developing more sustainable, biodegradable, flexible and biocompatible substrates, such as chitosan biocomposites for sensors applications [139], self-poled and bio-flexible films BCZT-based as piezoelectric nanogenerator (BF-PNG) functionalized with polydopamine and embedded in the polylactic acid [140]. In the recent literature, the BCZT system has been used in bio-glass-(BG) based ceramics systems to improve both the electrical properties and bioactivity as potential electroactive materials for orthopaedic applications [141]. Other interesting applications include bio-piezoelectric coatings for dental implants. The chewing as mechanical input is used to produce a piezoelectric response that promotes the alveolar bone growth. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the BCZT/TiO2 coating was non-toxic, and the proliferation of osteoblasts was higher compared to the simple TiO2 coatings. Moreover, a higher Ca deposition as apatite was observed.

(a) Novel lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric HA–BCZT nanocrystal composites for accelerated bone regeneration [138]; (b) BCZT 45 coatings on Kapton polymer substrates provide optimal support for osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in the bone marrow [128]; (c) simple schematics of device structures fabricated with BZT–BCT nanowires [145]; (d) schematics describing the comprehensive biocompatibility of high-performance lead-free flexible energy harvester [145].

Thanks to the sensibility of the ceramic system to low-intensity pulsed ultrasound, another interesting application could be on physical therapy, amplifying the piezoelectric effect within the system [142]. Recently, the production of BCZT coatings on titanium surface was implemented by adding silver as antimicrobial agent for inhibiting bacteria adhesion and proliferation that, at the same time, promotes the activity of osteoblasts, being suitable for orthopaedic implants [143]. Other studies present the possibility to produce functional BCZT-based bilayer coatings on Ti alloy for biomedical implants also [144]. In addition to in vitro studies, the most recent literature includes the report of some relevant in vivo applications such as bio implantable energy harvesters [145], implantable and wearable electronic devices on human and animal bodies [146] and intravascular ultrasound transducers [147].

Another step forward is the fusion between the piezoelectric effect and catalysis. By using piezoelectric materials, we can initiate or accelerate reactions. This feature is triggering the interest of the scientific community towards the so called “piezocatalytic medicine” for tumour therapy [148], antisepsis, biosensing, organics degradation and tissues repair and regeneration [149]. In order to push these frontier studies towards alternative applications, some crucial key points must be deeply investigated, such as material design, safety evaluation, scalability and standardization of processing routes, studies on mechanisms. In fact, although the biocompatibility of this system seems to be straightforward, at least for the absence of toxic elements, barium-based compounds can be potentially toxic depending on their solubility due to the release of Ba2+ in water environment. Therefore, on one hand, compounds like chlorides, nitrates, hydroxides and carbonates can interfere with potassium provoking gastrointestinal problems, muscles weakness, paralysis in chronic assumption. On the other hand, insoluble barium-based compounds, such as sulphates are safe and absolutely non-toxic [150]. In this sense, an aspect that must be considered is the presence of foreign elements that can be introduced into the lattice during the processing route. These ions can form other secondary compounds or diffuse into the main perovskite, affecting or changing the biocompatibility of the system [151]. For these reasons, the study of toxicity in relation to the processing route of ceramics is a key issue that needs to be further investigated. The behaviour of these materials changes drastically depending on the site of application/action and the micro-environment in which they are found, the interaction with the immune system, the possibility of interaction with assumed drugs and different diseases.

Conclusions and insights for the futureThe purpose of this review is revealing some key issues concerning the BCZT solid solution system as a potential candidate to replace PZT in both established commercial technologies and as a material suitable for new biomedical applications due to its non-toxicity and environmentally friendly nature. The review aims at understanding if there is the possibility to overcome the disadvantages with respect to the PZT system by analysing the fundamentals of the pseudo-ternary system, the milling techniques that are available to decrease the processing temperatures of the solid-state route and to make the material fabrication route suitable for industrial scaling up. In particular, it highlights how mechanical or mechano-chemical activation of precursors and synthesised powders is a key point for developing a scalable solid-state route and reducing energy consumption according to new EU directives. Moreover, as here reported, the BCZT material, indeed, can be considered a promising smart material and lead-free piezoceramic that meets all requirements to replace PZT. As it can be a valuable ally in the discovery and development of new technologies and applications, refining some of the main crucial points in its production in the near future is of outstanding importance.

The complexity of the BCZT system requires further study to understand the mechanisms that lead to good piezoelectric response and lower processing temperatures that enable industrial scaling up. Developing a trustworthy, scalable, environmentally friendly route to obtain good properties was a big challenge to which the authors have recently contributed [92,101]. Further studies are required to understand the internal mechanisms that lead to optimize piezoelectric response. To begin with, studies on individual synthesis step (synthesis mechanisms, formation kinetics), detailed information on solubility limits, stability diagrams, and surface hydrolysis are still lacking.

Additional studies on the correlation between mechanical activation and synthesis temperature are needed in the near future. In particular, in this respect, in-depth investigations of synthesis steps are lacking. Furthermore, there is the need to monitor the toxicity of the system under acute and chronic conditions for biomedical applications. Considering a number of key factors that have been here identified as crucial to the processing route, in addition to the choice of composition at MPB, we can mention: particle size selection to maximise c/a ratios in the sintered ceramic, the design of sintering procedures to allow grain growth control for optimising electromechanical properties and the scalability issues of the processing routes, as it has been done in the KNN system [152].

Dr. Armando Reyes-Montero and Prof. Lorena Pardo acknowledge the financial support of the project IN115 “Síntesis, caracterización y evaluación de cerámicos funcionales (piezoeléctricos, ferroeléctricos y multiferroicos) para su uso como captadores de energía vibracional”, financed by the Support Programme for Research and Technological Innovation Projects (PAPIIT-2024), México. Likewise, their gratitude to the PAPIIT-UNAM (IA102622) project funded by “Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica Solicitud 2022” (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM, México).

Prof. Sebastiano Garroni, acknowledges financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1, Call for tender No. 1409 published on 14.9.2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU – Project Title IUPITER – CUP J53D23014640001 – Grant Assignment Decree No. 1409 adopted on14 September 2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR).

Prof. Sebastiano Garroni and Dr. Marzia Mureddu acknowledge the financial support received for Dr. Marzia Mureddu's PhD fellowship in Chemical Sciences and Technologies, funded by the Programma Operativo Nazionale Ricerca e Innovazione 2014-2020 (CCI 2014IT16M2OP005) Fondo Sociale Europeo, Azione I.1 ‘Dottorati Innovativi con caratterizzazione industriale.’

![Comparative analysis of lead-free piezoelectric materials [(Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3, BCZT; (Bi,Na)TiO3, BNT; (K,Na)NbO3, KNN] against the lead-based PZT in terms of key properties: piezoelectric coefficient (d33), electromechanical coupling factor (kp), Curie temperature (Tc), thermal stability, favourable processing temperatures, critical raw materials, and biocompatibility. The radar chart highlights the advantages and limitations of each material, with BCZT showing promising properties as a lead-free alternative. Comparative analysis of lead-free piezoelectric materials [(Ba,Ca)(Zr,Ti)O3, BCZT; (Bi,Na)TiO3, BNT; (K,Na)NbO3, KNN] against the lead-based PZT in terms of key properties: piezoelectric coefficient (d33), electromechanical coupling factor (kp), Curie temperature (Tc), thermal stability, favourable processing temperatures, critical raw materials, and biocompatibility. The radar chart highlights the advantages and limitations of each material, with BCZT showing promising properties as a lead-free alternative.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000003/v1_202506231238/S0366317525000032/v1_202506231238/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Main milestones of the development of BCZT phase diagram (PD): (a) 1954: McQuarrie and Behnke reported for the very first time the baria–calcia–titania–zirconia composition tetrahedron showing the plane composition square of barium titanate (BT), barium zirconate (BZ), calcium titanate (CT) and calcium zirconate (CZ) [18]; (b) 1999: Ravez studied the pseudo-ternary PD (BT–BZ–CT) [29]; (c) 2009: Liu and Ren studied the PD of the pseudobinary ferroelectric BTZ20–xBC30T (BZT–xBCT), showing that, at the triple point, where there is a R–T–C phase coexistence, the piezoelectric properties are excellent [8]; (d) 2013: Keeble revised the PD of the BCZT solid-solutions using synchrotron XRD, including an orthorhombic phase [33]; (e) 2014: Acosta PD obtained from the peaks of the relative dielectric permittivity that confirmed the O/FE phase [35]; (f) simultaneous in 2014: Zhang updated the PD using Raman and permittivity results (the solid lines are a guide to the eyes) [43]; (g) 2016: Yang calculated the pseudo-binary PD of BZT–xBCT, which confirmed the experimentally obtained one; dots corresponds to the investigated following compositions: x=0.41000, 0.43360, 0.43450, 0.44750, 0.51905, 0.51913 and 0.55000 [38]. Main milestones of the development of BCZT phase diagram (PD): (a) 1954: McQuarrie and Behnke reported for the very first time the baria–calcia–titania–zirconia composition tetrahedron showing the plane composition square of barium titanate (BT), barium zirconate (BZ), calcium titanate (CT) and calcium zirconate (CZ) [18]; (b) 1999: Ravez studied the pseudo-ternary PD (BT–BZ–CT) [29]; (c) 2009: Liu and Ren studied the PD of the pseudobinary ferroelectric BTZ20–xBC30T (BZT–xBCT), showing that, at the triple point, where there is a R–T–C phase coexistence, the piezoelectric properties are excellent [8]; (d) 2013: Keeble revised the PD of the BCZT solid-solutions using synchrotron XRD, including an orthorhombic phase [33]; (e) 2014: Acosta PD obtained from the peaks of the relative dielectric permittivity that confirmed the O/FE phase [35]; (f) simultaneous in 2014: Zhang updated the PD using Raman and permittivity results (the solid lines are a guide to the eyes) [43]; (g) 2016: Yang calculated the pseudo-binary PD of BZT–xBCT, which confirmed the experimentally obtained one; dots corresponds to the investigated following compositions: x=0.41000, 0.43360, 0.43450, 0.44750, 0.51905, 0.51913 and 0.55000 [38].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000003/v1_202506231238/S0366317525000032/v1_202506231238/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![Relevant studies concerning the MPB and PPT in PZT and BCZT. (a) Composition-temperature phase diagram for PZT and Gibbs free energy profiles [58]. (b) A representation of loss of anisotropy of the spontaneous polarization in the PZT system as a function of the increase of Ti content at the MPB. The R phase obtained with βan <0 changes into T obtained with βan >0. (c) On the left: energy surfaces of selected compositions; on the right: the corresponding energy profiles intersected by the (110) C plane; bottom image: distribution of energy barrier superimposed on the computed pseudo-binary phase diagram of BZT–xBCT [38]. (d) Comparison between the elastic compliances of BCTZ and PZT and paths followed in the respective phase diagrams [39]. Relevant studies concerning the MPB and PPT in PZT and BCZT. (a) Composition-temperature phase diagram for PZT and Gibbs free energy profiles [58]. (b) A representation of loss of anisotropy of the spontaneous polarization in the PZT system as a function of the increase of Ti content at the MPB. The R phase obtained with βan <0 changes into T obtained with βan >0. (c) On the left: energy surfaces of selected compositions; on the right: the corresponding energy profiles intersected by the (110) C plane; bottom image: distribution of energy barrier superimposed on the computed pseudo-binary phase diagram of BZT–xBCT [38]. (d) Comparison between the elastic compliances of BCTZ and PZT and paths followed in the respective phase diagrams [39].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000003/v1_202506231238/S0366317525000032/v1_202506231238/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)

![High energy ball-milling methods and setups reported in the literature for processing BCZT ceramics. The blue arrows indicate the types of movement of the milling media (balls) and the powder to be milled, as well as of the vessels, which is also indicated by black arrows in the images of the vessels. The vessel is stationary only at attrition ball milling, where the revolving arms provokes spinning of the powder and balls that gives place to a massive number of shear forces. In the shaker-type milling the vessel describes a complex movement involving vibration in three dimensions. In the planetary milling, the vessels rotate on the top of a disk and around its own cylinder axis, resembling the movement of the planets around the sun. The impacts between particles and balls and/or inner walls of the vessel can cause compression forces or shear forces depending on the angle of the impact. The upper part of the figure shows the effect of the two main types of impacts on the powder particles. The main milling parameters affecting the characteristics of the milled powder are also indicated in the upper part. The lower part of the figure depicts the relative movements of the powder particles and the balls, as well as the main types of forces on the powder arising from the impacts for each milling method. For efficient milling, all types of impacts and related effects must be present and all three methods fulfil this criteria [95]. High energy ball-milling methods and setups reported in the literature for processing BCZT ceramics. The blue arrows indicate the types of movement of the milling media (balls) and the powder to be milled, as well as of the vessels, which is also indicated by black arrows in the images of the vessels. The vessel is stationary only at attrition ball milling, where the revolving arms provokes spinning of the powder and balls that gives place to a massive number of shear forces. In the shaker-type milling the vessel describes a complex movement involving vibration in three dimensions. In the planetary milling, the vessels rotate on the top of a disk and around its own cylinder axis, resembling the movement of the planets around the sun. The impacts between particles and balls and/or inner walls of the vessel can cause compression forces or shear forces depending on the angle of the impact. The upper part of the figure shows the effect of the two main types of impacts on the powder particles. The main milling parameters affecting the characteristics of the milled powder are also indicated in the upper part. The lower part of the figure depicts the relative movements of the powder particles and the balls, as well as the main types of forces on the powder arising from the impacts for each milling method. For efficient milling, all types of impacts and related effects must be present and all three methods fulfil this criteria [95].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/03663175/0000006400000003/v1_202506231238/S0366317525000032/v1_202506231238/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr5.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)