In order to form critical citizenship, history teaching and learning should foster the development of social and civic competence. To this end, it is necessary to introduce changes in teaching methods and in the training of future teachers. The aim of this research is to evaluate the effectiveness of Project 1936 in initial teacher training, as well as to verify whether there are differences between perceptions of participating and non-participating students with respect to the use of innovation strategies, the interest in the study of history, and the acquisition of social and civic competence. A total of 239 students from the UPV/EHU Primary Education Degree participated in this study: 116 in the experimental group and 122 in the control group. A 21-item questionnaire was used, divided into three variables. Analyses of mean differences and their respective effect sizes, and multiple linear regression analyses were carried out. Following the teaching intervention, a statistically significant high-magnitude increase was observed in all variables for the experimental groups. We can conclude that the introduction of innovative teaching strategies, such as the approach to socially controversial topics and the use of technological teaching resources, increase the interest in the study of history and indirectly affect the development of social and civic competence.

La enseñanza-aprendizaje de la historia debe auspiciar el desarrollo de la competencia social y cívica, para formar una ciudadanía crítica. Para ello, es necesario introducir cambios en los métodos de enseñanza y formar al futuro profesorado. El objetivo de esta investigación ha sido evaluar la efectividad del Proyecto 1936 en la formación inicial del profesorado y verificar si se han producido diferencias entre la percepción del alumnado participante y no participante, sobre el uso de estrategias de innovación, el interés por el estudio de la historia y la adquisición de la competencia social y ciudadana. Han participado 239 estudiantes del Grado de Educación Primaria de la UPV/EHU: 116 grupo experimental y 122 grupo control. Se ha utilizado un cuestionario de 21 ítems, dividido en tres variables. Se han realizado análisis de diferencias de medias y sus respectivos tamaños del efecto, y análisis de regresión lineal múltiple. Tras la intervención, se ha producido un incremento estadísticamente significativo de elevada magnitud en todas las variables para los grupos experimentales. Se ha podido concluir que la introducción de estrategias de innovación docente, como el abordaje de temas socialmente controvertidos y el uso de recursos didácticos tecnológicos, han aumentado el interés para el estudio de la historia, afectando de manera indirecta al desarrollo de la competencia social y ciudadana.

History teaching-learning processes should be targeted at signifying and mobilising academic knowledge about the past so as to help students understand current social phenomena and experience (Barton & Levstik, 2004) and to develop social and civic competence in order to promote the exercise of critical, tolerant and democratic citizenship (Ortuño et al., 2012; Puig & Morales, 2015). Far from perpetuating a purely transmissive learning model based on the uncritical memorisation of concepts, data and dates and on the adherence to a textbook-centred and expository method (Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2018b; Martínez et al., 2006), alternatives are being proposed to reorient pedagogical practices in different directions (Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2018a).

One such alternative advocates the use of digital technology and mobile learning in educational environments (Hylén, 2012), especially mobile applications or apps, which have become an interesting resource that allows for scenes and realities distant in time and space to be recreated. In this way, new uses are provided for teaching resources that involve a more dynamic and immersive learning experience (Ibáñez-Etxeberria et al., 2020). In studies conducted in formal education settings, it has been proven that, in addition to increasing student motivation (Faria et al., 2019), this kind of technology facilitates the acquisition oh history-related knowledge (Kortabitarte et al., 2018) and the development of citizenship skills (Castrillo et al., 2021), so that their use should be part of the bundle of contents of initial teacher training (Ally et al., 2014; Baran, 2014).

Against the backdrop of proposals for didactic renewal, strategies based on the introduction of socially controversial topics in the classroom have likewise acquired a special prominence due to the potential they afford in terms of building capacities for the interpretation of social facts, as well as promoting the development of critical thinking and argumentative skills (Berg et al., 2003; Hand & Levinson, 2012; Santisteban, 2019), all of which is related to social and civic competence.

In Spain, the vindication of historical memory related to the Civil War and the Francoist regime occupies a pre-eminent place among these conflictive topics that possess an educational potential, as it involves approaching divergent interpretations of the past and fostering the learning of history as knowledge under constant and conscious reexamination (Delgado-Algarra & Estepa-Giménez, 2016; Martínez & Sánchez, 2018). It also allows students to practise the historical method by analysing primary sources in the form of testimonies of first-hand witnesses, which can help increase their motivation (Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2021). Furthermore, it can contribute to the formation of historical thinking on the basis of a more humanistic and empathetic approach to the victims of history itself (Rüsen, 2013; Seixas, 2015) and facilitate the heritagization of aspects ignored by hegemonic historical narratives (Castrillo et al., 2022).

However, historical memory is an area that is rarely addressed, both in basic education (Arias et al., 2019) and in initial teacher training (Luna et al., 2022). Therefore, it seems relevant to reclaim its inclusion in training programmes for future teachers without eschewing its controversial dimension (Claire, 2001), especially if we consider the difficulties confronted by the active teaching staff in dealing with this type of issues in the classroom (Kello, 2016; Toledo et al., 2015).

Inspired by the conviction that it is necessary to train teachers in new strategies for the teaching-learning of history, the University of the Basque Country (UPV-EHU) has designed Project 1936, which combines work on controversial situations and the use of digital technologies with a view to implementing its findings in initial training classrooms. This paper evaluates the effect of such an implementation on students in relation to the researched variables: (1) Student perception regarding the use of innovation strategies, the interest in the study of history and the acquisition of social and civic competence in connection with historical memory, both before and after the intervention; and, (2) Variation in all three constructs following participation in Project 1936.

MethodDesignThis has been a quasi-experimental study involving pre- and post-intervention data collection from two parallel arms (intervention group and control group). The initiative grew out of a previous pilot study (Gillate et al., in press).

ParticipantsSample size calculationOn the basis of data obtained in the phase II study, it was determined that in order to have a statistical power of 90% in the detection of pre-post intervention differences of lesser magnitude between the control and experimental groups (corresponding to the variable interest in the study of history, with an associated effect size of 0.19 and a risk level of 5%), 122 students per group had to be enrolled in this phase. Since it is common for dropouts during follow-up to occur, and more so in the Covid-19 pandemic situation in which the study was carried out, this figure was raised by 30%, resulting in an initial sample size of at least 318 students, 158 per group.

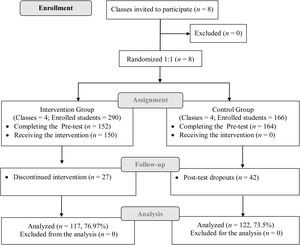

Selection and assignment of classesIn order to achieve the sample size, and given the practical limitations imposed by the pandemic, a number of possible participant classes identified as stable cohabitation groups were selected for convenience purposes. All invited teachers and their respective classes agreed to participate. The eight classes were randomly assigned to the control or experimental group in a 1:1 ratio. The experimental group included all 4 classes of the Faculty of Education in Bilbao, while the control group comprised 2 classes of the Faculty of Education and Sports in Vitoria-Gasteiz and 2 classes of the Faculty of Education, Philosophy and Anthropology in San Sebastian. By choosing groups from different campuses, we aimed at avoiding the contamination effect in the case-control subgroups and, in this way, increase the validity of the research.

Inclusion/exclusion criteriaThe criteria for inclusion in the study were: (1) regular class-attendance in the subjects for which the research was implemented and (2) signature of the informed consent form.

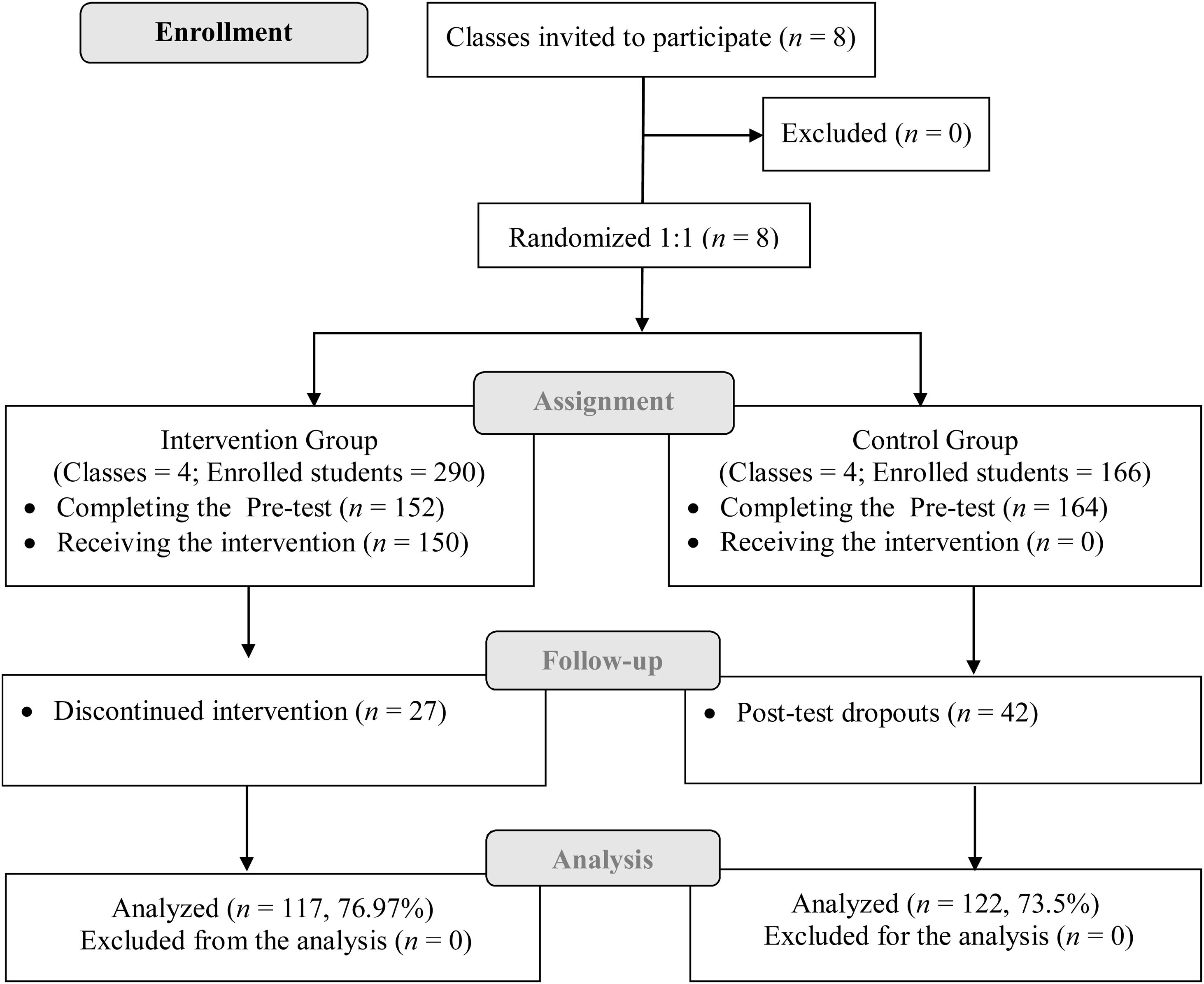

Participation flowchartFigure 1 summarizes the process of participation in the research study. As can be seen, of the 456 potential participants, 316 joined the initial evaluation (69.30%), while 239 (52.41% of the potential participants —i.e. 75.63% of those who completed the pre-test) were taken into account for the purpose of analyzing the information. Dropouts were high, but they were to be expected given the current health situation, involving lockdowns, preventive absenteeism, etc., which involved the discontinuation of class attendance by many students.

ParticipantsFinally, 239 students from 8 third year classes of the Primary Education Degree at the University of the Basque Country, aged between 20 and 58 (M = 21.60, SD = 1.37), took part in the research study and enrolled in Project 1936, which ran between January and April, 2021. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of gender (χ21 = 0.29, p = .585) and age distribution (χ23 = 3.04, p = .386) (Table 1).

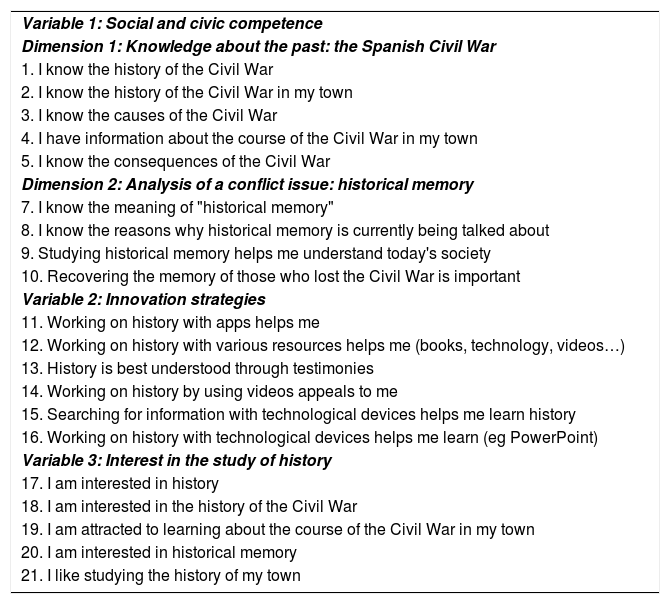

InstrumentsThe main outcome measure was the changes in knowledge about the civil war and historical memory, as indicators of the development of social and civic competence, while the secondary measures were the changes in the perception of the use of innovation strategies in education and the interest in the study of history. In order to operationalize them, a 21-item questionnaire (Appendix 1) on a Likert response format (1 = very little and 5 = very much) was used following its design and optimization in phase II. It consisted of the following variables, whose psychometric characteristics are shown below:

Social and civic competence in relation to the Civil War and historical memory. This was split up into two dimensions. The dimension that assessed the perception of competence with regard to knowledge of the past: the Spanish Civil War, consisting of 6 items, shows goodness-of-fit to the one-factor model [χ2 = 41.90, p = .001, χ2/df = 4.65, CFI = .97, TLI = .95, RMSEA (CI90%) = .090 (.082-.13), SRMR = .09] and high reliability (CF = .83, α = .91, ω = .90, AVE = .64). The one-dimensional scale that assessed the second dimension, analysis of a conflict issue: historical memory, consists of 4 items [χ2 = 64.97, p = .001, χ2/df = 1.91, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA (CI90%) = .060 (.00-.13), SRMR = .05] and has high reliability (CF = .75, α = .82, ω = .83, AVE = .56).

Innovation strategies. This is a one-dimensional scale made up of 6 items that measured the students' perception of the use of a set of innovative learning strategies [χ2 = 3.38, p = .641, χ2/df = 0.68, CFI = .98, TLI = .99, RMSEA (IC90%) = .001 (.00-.07), SRMR = .04] whose reliability proved high (CF = .80, α = .82, ω = .83, AVE = .52).

Interest in the study of history. Evidence has been found supporting goodness-of-fit of the data to a one-dimensional model for interest estimated by responses to 5 items [χ2 = 7.41, p = .192, χ2/df = 1.48, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA (IC90%) = .045 (.00-.10), SRMR = .06]. The CF ratio was .80, the alfa value was .80, the ω coefficient equalled .80 and the AVE was .65.

ProcedureThe project started once the informed consent of participants was obtained.

InterventionProject 1936 has sought to train future teachers in the integration of controversial topics in the social sciences classroom, as well as in the use of mobile devices and apps for teaching-learning processes. Specifically, work was carried out on the Spanish Civil War and the recovery of historical memory by using the app Eibar 1936-1937 Guía as the central resource of this training intervention. The project lasted a total of 12 hours structured into 8 sessions (Table 2) dedicated to teaching theoretical and procedural contents about the potential of using apps in primary education. In addition, and from the point of view of social and civic competence, work was done on knowledge about the Civil War, historical memory and the approach to controversial issues in the classroom. Various educational materials and formats were combined, such as presentations by teachers and by participants, video viewings and the app Eibar 1936-1937 Guía, where students conducted information searches.

Structure of sessions and tasks of Project 1936

| Session | Activities |

|---|---|

| 1 | - Project presentation. |

| - Theory: Apps and education. | |

| - App download. | |

| 2 | - Theory: The Civil War and historical memory. |

| 3 | - Questionnaire on basic concepts of the civil war. |

| 4 | - Viewing of the documentary "Gernikaren Egiak". |

| - Analysis of the testimonies in the app. | |

| 5-6 | - Researching sources on a passage from historical memory, retrieving the latter and proposing a site in the surrounding environment to promote its heritagization. |

| 7-8 | - Theory: How to deal with controversial issues in the classroom. |

| - Written discussion. |

Eibar 1936-1937 Guía is an app launched in 2016 by Eibar’s Town Council which offers three thematic tours around the Spanish Civil War in this Basque population center (Vicent et al., 2020). Although the app lacks explicit learning objectives, it features a didactic orientation of an interpretative type and makes a point of relating its informative contents to the reality of Eibar’s environment. Among its strengths, mention must be made of the extensive information it provides on the Civil War and its course in this municipality and in the Basque Country at large. This information is structured into several levels and is easy to access. It also features historical photographs, videos including the testimonies of survivors, and the use of geopositioning technologies. It also allows users to select their areas of interest and program customized visits.

MeasurementIn order to collect information on changes brought about by the intervention, participants completed an evaluation questionnaire in ordinary teaching conditions before and after the intervention itself.

Data analysisInitially, an analysis was carried out in order to assess the presence and pattern of missing values and outliers for each of the aspects that were measured. Since missing data have been scarce, no value imputation techniques were used. Next, the validity of inferences made on the basis of the scores obtained from the questionnaire in the present sample were assessed by means of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs). Given the ordinal nature of the items, the estimation method was diagonal weighted least squares (DWLS) on the polychoric correlation matrices. The assessment of the models’ goodness-of-fit to the data was based on the value of the chi-square/df ratio (χ2/df), as well as on information provided by the incremental goodness-of-fit (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis (TLI) indices and the absolute fit indices for root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its standardisation (SRMS) (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kenny et al., 2015). Models with values lower than 5 for the χ2/df ratio, equal to or greater than .90 for CFI and TLI and equal to or less than .10 for RMSEA and SRMS were considered acceptable. Composite reliability (CR), the McDonald's omega reliability coefficient (ω) and the average variance extracted (AVE) were also calculated as indicators of the internal consistency of the scores.

In addition, to ensure the adequacy of the measurements at the two moments of data collection, factorial scale invariance analyses were carried out in the pre-test and post-test phases. Equivalence levels were defined in terms of the parameters conditioned to be equal in the groups being studied. The simplest model was that of configural invariance (factor loadings pattern), while restrictions were added so as to evaluate metric invariance (magnitude of factor loadings), scalar invariance (intercepts) and strict (residual) variance. In order to establish the relevance of the goodness-of-fit differences between the models, a double criterion was used based on the differences between values in the CFI index (the decrease must be equal to or less than 0.010) and in the RMSEA index (the increase must be equal to or less than 0.015) between one model and the next more restrictive one, as suggested by Chen (2007), Cheung and Rensvold (2002).

After calculating the aggregate scores and given the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity, the associations between the dimensions were estimated and the effect attributable to the intervention was calculated by the difference in scores on social and civic competence, the use of innovation strategies and the interest in the study of history in the intervention group and the control group for both measurements. Sex, age and class were adjusted for possible confounding or modifying covariates of the intervention effect by means of the analysis of covariance models. These results were accompanied by corresponding partial Eta squared effect size calculations (η2). The effect size was considered negligible if it was smaller than 0.01, small between 0.01 and 0.039, medium between 0.04 and 0.11 and large from 0.12 onwards (Cohen, 1988).

Finally, the relationship between changes in the variables innovation strategies and interest in the study of history, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, social and civic competence has been evaluated taking into account the assigned group by means of multiple linear regression analysis. The analyses were performed by means of software packages psych, lavaan and semPlot included in software environment R 4.0.2. (R Core Team, 2017).

ResultsLongitudinal invariance of measuresThe analysis of longitudinal invariance yielded the results shown in Table 3. Regarding knowledge of the past: the Spanish Civil War, the fit indices obtained enable us to accept the configural equivalence of the model scale between measurements. The addition of restrictions on the regression coefficients, the values shown in the table and the differences between CFI (ΔCFI = -.006) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA = .006) induced us to accept the metric invariance model, which in turn led us to evaluate the equivalence between the intercept values. The values obtained supported the acceptance of this scalar invariance model (ΔCFI = -.050, ΔRMSEA = -.011). The same occurred when testing for strict invariance (ΔCFI = -.050, ΔRMSEA = -.011). The indices associated with analysis of a conflict issue: historical memory also allowed us to accept configural, metric, scalar and strict equivalence as there were no changes in CFI and no increases in RMSEA until the last stage (ΔCFI = -.006, ΔRMSEA = .001). These findings have been repeated in the case of perceived use of innovation strategies and interest in the study of history.

Fit indices for factorial invariance between pre-test and post-test

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | p | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge about the civil war | ||||||

| Unrestricted model | 53.50 | 18 | 2.97 | <.001 | .985 | .093 |

| Restricted weights | 73.87 | 23 | 3.21 | <.001 | .979 | .099 |

| Restricted intercepts | 91.27 | 28 | 3.36 | <.001 | .974 | .100 |

| Restricted residuals | 94.54 | 34 | 2.78 | <.001 | .975 | .089 |

| Knowledge about historical memory | ||||||

| Unrestricted model | 5.39 | 4 | 1.35 | .249 | .999 | .039 |

| Restricted weights | 6.02 | 7 | 0.86 | .537 | .999 | .001 |

| Restricted intercepts | 8.40 | 10 | 0.84 | .590 | .999 | .001 |

| Restricted residuals | 19.54 | 14 | 1.40 | .145 | .993 | .040 |

| Innovation strategies | ||||||

| Unrestricted model | 5.15 | 10 | 0.51 | .881 | .999 | .004 |

| Restricted weights | 6.17 | 14 | 0.44 | .962 | .999 | .001 |

| Restricted intercepts | 13.78 | 18 | 0.76 | .743 | .999 | .001 |

| Restricted residuals | 22.81 | 23 | 0.99 | .472 | .999 | .001 |

| Interest in the study of history | ||||||

| Unrestricted model | 10.04 | 10 | 1.00 | .437 | .999 | .004 |

| Restricted weights | 11.39 | 14 | 0.81 | .655 | .999 | .001 |

| Restricted intercepts | 12.68 | 18 | 0.70 | .811 | .999 | .001 |

| Restricted residuals | 16.46 | 23 | 0.71 | .835 | .999 | .001 |

Note. χ2 = chi-square test, df = degrees of freedom, χ2/df = value of the chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio, p = level of significance, CFI = incremental goodness-of-fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

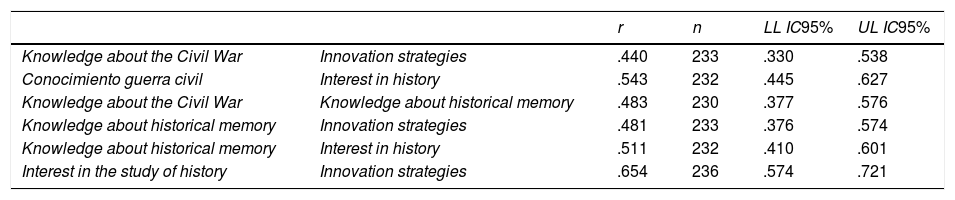

Table 4 shows a pattern of positive and moderate associations between all possible pairs of variables studied.

Pearson product-moment correlations and their confidence intervals at 95%

| r | n | LL IC95% | UL IC95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge about the Civil War | Innovation strategies | .440 | 233 | .330 | .538 |

| Conocimiento guerra civil | Interest in history | .543 | 232 | .445 | .627 |

| Knowledge about the Civil War | Knowledge about historical memory | .483 | 230 | .377 | .576 |

| Knowledge about historical memory | Innovation strategies | .481 | 233 | .376 | .574 |

| Knowledge about historical memory | Interest in history | .511 | 232 | .410 | .601 |

| Interest in the study of history | Innovation strategies | .654 | 236 | .574 | .721 |

Note. r = Pearson correlation coefficient; n = sample size; LLCI 95% = lower limit for confidence interval at 95%; ULCI 95% = upper limit for confidence interval at 95%.

Tables 5 and 6 show the scores obtained before and after the intervention by the intervention and control groups on the variables being studied, as well as the results of the analyses of differences between the groups carried out at each time point, after verifying the non-existence of statistically significant effects of the possible confounding variables sex, age and class attended.

Scores and analysis of mean differences between the groups in the pretest

| Pre-intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | ANOVA | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | F | p | η2 | |

| Knowledge about the Civil War | 2.99 | 0.70 | 2.39 | 0.86 | 3.39 | <.001 | 0.13 |

| Knowledge about historical memory | 3.67 | 0.75 | 3.35 | 0.87 | 4.47 | .002 | 0.04 |

| Innovation strategies | 3.99 | 0.60 | 3.66 | 0.60 | 18.67 | <.001 | 0.07 |

| Interest in the study of history | 4.11 | 0.67 | 3.48 | 0.98 | 33.26 | <.001 | 0.12 |

Note. M = arithmetic mean; SD = standard deviation; ANOVA = Analysis of variance.

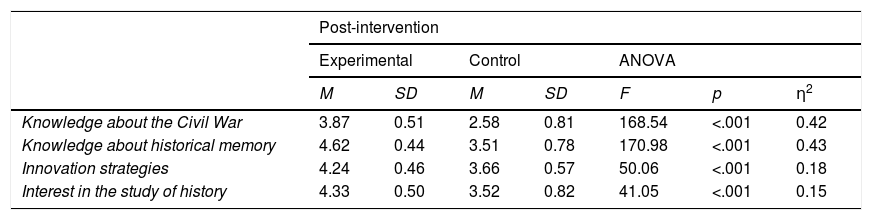

Scores and analysis of mean differences between groups on the post-test

| Post-intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | ANOVA | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | F | p | η2 | |

| Knowledge about the Civil War | 3.87 | 0.51 | 2.58 | 0.81 | 168.54 | <.001 | 0.42 |

| Knowledge about historical memory | 4.62 | 0.44 | 3.51 | 0.78 | 170.98 | <.001 | 0.43 |

| Innovation strategies | 4.24 | 0.46 | 3.66 | 0.57 | 50.06 | <.001 | 0.18 |

| Interest in the study of history | 4.33 | 0.50 | 3.52 | 0.82 | 41.05 | <.001 | 0.15 |

Note. M = arithmetic mean; SD = standard deviation; ANOVA = Analysis of variance with pretest as a covariate.

Contrary to expectations, in the pre-intervention assessment, we overall found quite high scores (above the theoretical mean of 2.5 points) and initial inequivalence between the groups. The experimental group scored significantly higher than the control group on all dependent variables. For this reason, analyses of post-intervention differences were conducted while controlling for baseline level by introducing them as covariates in the analyses.

In the evaluation carried out after the intervention, statistically significant differences of a high magnitude were found in the means between the groups in all the variables measured. In the case of knowledge about the past: the Spanish Civil War, the difference was 0.96 points (95% CI = 0.82-1.10), while in the case of analysis of a conflict issue: historical memory, the difference was 0.99 (95% CI = 0.84-1.14). In the secondary variables, the following differences were found between the groups: 0.40 points (95% CI = 0.29-0.51) for perceived use of innovation strategies and 0.44 (95% CI = 0.30-0.58) for interest in the study of history. No statistically significant effect of the variables gender, age and class was found. In addition, it was found that the evolution in the variables analyzed was much bigger in the intervention group, with scarcely relevant changes in the control group (Table 7).

Difference in means between the scores before and after the intervention in the experimental and control groups

| CI 95% | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | LL | UL | T | df | p | η2 | |

| Experimental | ||||||||

| Knowledge about the Civil War | -.88 | .74 | -1.01 | -.74 | -12.72 | 114 | <.001 | .58 |

| Knowledge about historical memory | -.94 | .87 | -1.10 | -.77 | -11.33 | 110 | <.001 | .54 |

| Innovation strategies | -.26 | .55 | -.36 | -.15 | -5.00 | 114 | <.001 | .18 |

| Interest in the study of history | -.24 | .59 | -.35 | -.13 | -4.28 | 114 | <.001 | .14 |

| Control | ||||||||

| Knowledge about the Civil War | -.19 | .53 | -.29 | -.09 | -3.91 | 116 | <.001 | .11 |

| Knowledge about historical memory | -.14 | .63 | -.26 | -.03 | -2.53 | 120 | .056 | .05 |

| Innovation strategies | -.01 | .45 | -.09 | .07 | -.28 | 115 | .392 | <.01 |

| Interest in the study of history | -.03 | .60 | -.14 | .08 | -.62 | 117 | .270 | <.01 |

Note. M = mean difference; SD = Standard deviation of differences; CI 95% = Confidence interval for mean differences; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; T = Student's T-Statistic for repeated measures; df = degrees of freedom; p = significance level associated with the statistic value; η2 = partial Eta squared effect size.

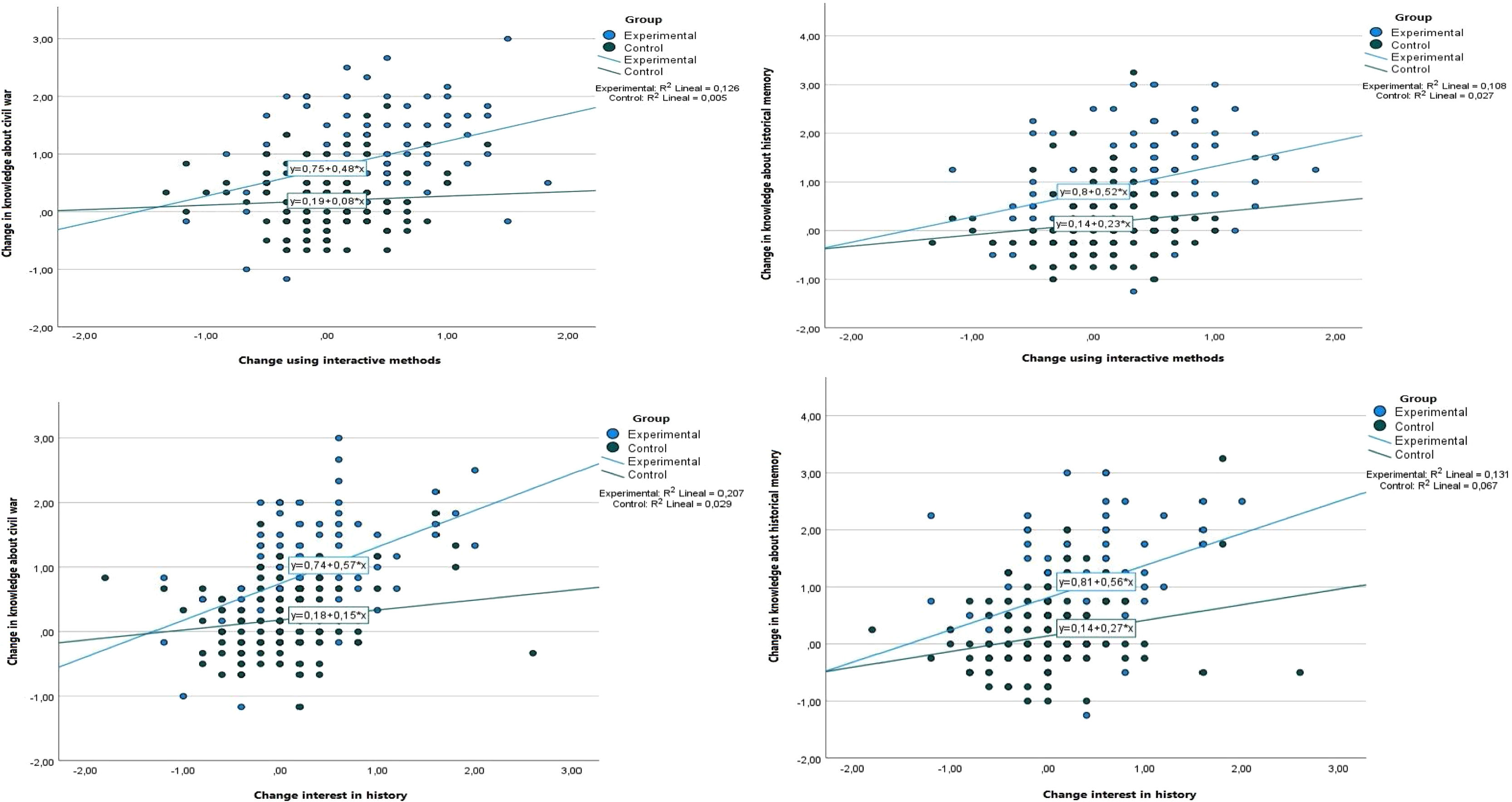

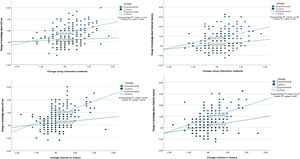

Finally, it can be posited that the changes in the perception of the use of innovation strategies and the increase in interest in the study of history have only been significantly related to the changes in knowledge about the past: the Spanish Civil War and in the analysis of a conflict issue: historical memory in the experimental group, as can be seen in Figure 2.

DiscussionThe project whose effectiveness has been evaluated is based on the premise that it is necessary to change the traditional paradigm of history teaching, in which teachers deliver the presentation of contents and students memorize a series of concepts, dates and events from the past (Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2018b; Martínez et al., 2006). Such a model does not take into account either the students or their environment, and is based almost exclusively on the transmission of declarative knowledge, thus relegating to the background procedural and attitudinal knowledge. This is ineffective for the development of social and civic competence, which should ultimately be one of the main purposes of history learning (Ortuño et al., 2012; Puig & Morales, 2015).

In order to foster this competence, it is necessary to effect changes in teaching-learning strategies. In this sense, Project 1936 has combined the introduction of methodological changes, such as working with apps, and the approach to controversial issues like historical memory in connection with the Civil War. The pilot study developed around the project underscored the validity of the explanatory model according to which the introduction of teaching innovation strategies increases the interest in the study of history while positively affecting the development of social and civic competence (Gillate et al., in press). The current study has confirmed this hypothesis, since the correlation between the three variables has been significant only in the experimental group, and not in the control group.

The results seem to corroborate the effectiveness of the project, as already suggested by the pilot study, since, after the intervention, there has been a statistically significant high-magnitude increase in all three variables (innovation strategies, interest in the study of history, and social and civic competence in relation to the Civil War and historical memory) in the groups of participants in Project 1936, while in the control groups changes have been statistically insignificant.

Thus, it can be argued that the use of seldom-used teaching resources in history classes, such as working with apps and primary sources, has increased the positive perception that future primary education teachers have about the incorporation of innovation strategies. The results for this variable have been statistically significant in the experimental group, and of lesser importance in the control group. This fact is particularly relevant insofar as it has brought students closer to a history teaching model far removed from the rote learning tradition, which as a general rule they have not been exposed to in their previous educational trajectory, so that they find it difficult to put it into practice.

The results indicate that the use of technological resources such as apps can improve the interest in the study of history, since the changes in relation to this variable following the implementation of the classroom project were greater for the experimental group than for the control group, where such changes were less noticeable. The benefits to be drawn from the use of this type of device in the classroom have already been pointed out in the studies by Kortabitarte et al. (2018), Faria et al. (2019) or Castrillo et al. (2021). Certainly, the versatility of apps makes it possible to introduce into educational practice elements that were traditionally found in coursebooks, such as photographs or texts, but also others such as audios, videos or itineraries, which contribute to invigorating the teaching of history.

In addition, the history contents that our trainees learned to teach in Project 1936 were understood as knowledge in permanent construction. On the one hand, the app Eibar 1936-1937 Guía provides a more tangible approach to the scene of the historical events being studied and a more humanistic and experientially perceived history of the Civil War, as recounted by the testimonies of the main actors of the events, which in turn fosters historical empathy (Rüsen, 2013; Seixas, 2015). On the other, they have worked with historical sources and this has had an impact on the increase in their interest in the subject under examination (Gómez-Carrasco et al., 2021). Indeed, they have had to investigate so as to retrieve a fragment of the memory of the Civil War which they themselves chose and later turned into a piece of heritage of their own. Thus, what happened in the past becomes embodied: memories that transcend official history are visibilized and those who lost the war and were ignored by the hegemonic historical narratives now find a place in the map of history (Castrillo et al., 2022).

The participants’ enhanced perception regarding their social and civic competence in relation to the Civil War and historical memory was remarkably higher in the experimental group than in the control group. This suggests the convenience of introducing in the classroom controversial issues and real social problems which connect students with the society in which they live (Berg et al., 2003; Hand & Levinson, 2012; Santisteban, 2019). It also foregrounds the usefulness of historical memory in promoting a citizenry committed to understanding the past and solving the problems of the present (Bjerg et al., 2014; Delgado-Algarra and Estepa-Giménez, 2016; Martínez & Sánchez, 2018; Nygren & Johnsrud, 2018). In short, the choice of a current controversial topic, such as historical memory and the Spanish Civil War, has enabled trainee teachers to understand the importance of problematizing the past and teaching it in relation to the consequences it had for the population, especially from the perspective of those who were victims of retaliation. In this way, prospective teachers have been able to realize the importance of moving from teaching the phases of war and its several military episodes, which is what is mostly transmitted in compulsory education classrooms (Luna et al., 2022), to reflecting on the effects that the war had on people and society, and, ultimately, on our present time.

This study has several limitations that make it difficult to generalize the results. The first has been the choice for convenience reasons of the target participants: the students of the Degree in Primary Education at UPV/EHU. The second shortcoming, possibly derived from the previous one, has been the initial inequivalence between the experimental and control groups. This may be due to the fact that the project being assessed was carried out during the second semester, and the students of the experimental group had already worked on two other projects in the first semester, so that they were already familiar with the methodology used by the teaching staff. Among this study’s strengths, mention must be made of the confirmation of longitudinal invariance. This has provided evidence about the validity of the scores obtained from the measurements performed at the two moments when the evaluation was carried out, that is, before and after the intervention.

In any case, initiatives such as Project 1936 are designed as valid alternatives for the purpose of training future teachers according to a history education model that is far removed from the traditional rote learning paradigm and advocates preparing students to critically understand the social phenomena of their time with a view to building a future society based on values like tolerance and democracy.

FundingThis study has received funding from research groups Sociedades, Procesos, Culturas (IT1465-22) and GIPyPAC (IT1193-19) at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) and from the project “Modelos de aprendizaje en entornos digitales de educación patrimonial” (PID2019-106539RB-I00) financed by MINECO/FEDER.

| Variable 1: Social and civic competence |

| Dimension 1: Knowledge about the past: the Spanish Civil War |

| 1. I know the history of the Civil War |

| 2. I know the history of the Civil War in my town |

| 3. I know the causes of the Civil War |

| 4. I have information about the course of the Civil War in my town |

| 5. I know the consequences of the Civil War |

| Dimension 2: Analysis of a conflict issue: historical memory |

| 7. I know the meaning of "historical memory" |

| 8. I know the reasons why historical memory is currently being talked about |

| 9. Studying historical memory helps me understand today's society |

| 10. Recovering the memory of those who lost the Civil War is important |

| Variable 2: Innovation strategies |

| 11. Working on history with apps helps me |

| 12. Working on history with various resources helps me (books, technology, videos…) |

| 13. History is best understood through testimonies |

| 14. Working on history by using videos appeals to me |

| 15. Searching for information with technological devices helps me learn history |

| 16. Working on history with technological devices helps me learn (eg PowerPoint) |

| Variable 3: Interest in the study of history |

| 17. I am interested in history |

| 18. I am interested in the history of the Civil War |

| 19. I am attracted to learning about the course of the Civil War in my town |

| 20. I am interested in historical memory |

| 21. I like studying the history of my town |