To evaluate the benefits of martial arts on the functional aspects and quality of life of elderly individuals, and the level of evidence of the results.

MethodsA systematic review of randomized clinical studies was performed using the Cochrane, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SciELO, LILACS and PEDro electronic databases. A specific search strategy was developed for each database, and all published studies were included, regardless of the data collection instruments or the date of publication. The eligibility criteria followed the PICOT strategy, and the level of evidence of all outcomes was assessed using the GRADE scale. Initially, 1682 studies were retrieved, and duplicates were identified and excluded using the RAYYAN platform. After analyzing the title and abstract, eligible studies were read in full, and ten studies were selected for inclusion in this study.

ResultsThe meta-analysis showed a significant difference in the assessment of functional mobility for the martial arts group, whereas the control group (physically active) showed a difference in balance and handgrip strength. Quality of life meta-analysis was not possible because of study heterogeneity. In the evaluation of the level of evidence, GRADE results indicated a serious risk of bias because there was no blinding of the raters and a serious risk of imprecision because of the low number of patients evaluated; thus, the evidence has low clinical certainty.

ConclusionTaekwondo (adapted) and Muay Thai (ritual dance) are indicated as intervention approaches to improve the functional mobility of elderly people. However, the results of related studies have a low level of evidence. Future studies may change the state of the art.

RegistrationThe review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (ID number and hyperlink: CRD42022313588).

Living longer is one of the greatest achievements of humankind, but a longer life, in and of itself, is not sufficient; it is necessary to live with a quality of life.1 Adding satisfaction to years lived is the most appropriate construct of successful ageing because it takes into account quantitative data, i.e., years lived, and qualitative data, i.e., the increased perception of values and goals achieved.2

In contrast, with advancing age, the occurrence of falls becomes more prevalent, and falls directly decrease the quality of life and life expectancy of elderly individuals. Individuals in this age group commonly report a fear of falling, affecting the confidence and autonomy of the individual, thus decreasing exposure to physical activities.3 Within this context, the World Health Organization recommends active ageing through regular physical activity because it confers several benefits, such as a decreased mortality rate. These activities can be performed as part of recreation and leisure (playing, games, sports, or planned exercise), through locomotion (walking or cycling), and while performing work tasks or completing household chores.4

Thus, body practices can be used as intervention strategies because they are “individual or collective expressions of body movement, arising from knowledge and experience around games, dance, sports, wrestling, or gymnastics, constructed in a systematic (at school) or unsystematic (free time/leisure)” way.5 These are culturally relevant physical practices that concern humans in motion, who express themselves bodily through gestures full of values and meanings.

Martial arts are body practices that use attack and self-defence techniques and have as objectives physical and mental improvements in individuals.6 Therefore, it is important to critically analyze the state of the art so that health professionals can understand the therapeutic effects of martial arts in elderly people and indicate its practice as a strategy for successful ageing. Thus, the objectives of this study were to evaluate the benefits of martial arts with regard to the quality of life and functional aspects of elderly individuals and to analyse the level of evidence of the results.

MethodsType of studyThis was a systematic review registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (number: CRD42022313588). The eligibility criteria followed the Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Time (PICOT) strategy as indicated by PRISMA7 (Table 1). The PICOT question was as follows: Compared with elderly individuals in any control group, do elderly patients undergoing martial arts interventions have a lower risk of falls and better quality of life at any time point evaluated after the intervention, based on the results for specific outcomes (balance, fear of falling, fall event, muscle strength, and quality of life)?

PICOT strategy.

P, Patient; I, Intervention; C, Comparison; O, Outcome; T, Time.

All published clinical trials, regardless of the data collection instruments or the date of publication, were included. Clinical trials that dealt exclusively with tai chi were excluded because there are already several systematic reviews regarding its clinical efficacy.8-14 Studies that addressed patients with Parkinson’s disease with locomotor system impairment, thus preventing their comparison with other groups, and studies without a control group were excluded.

The CENTRAL (Cochrane), PubMed, Embase, CINAHL and PEDro electronic databases were searched using strategies specific to each database. The search strategy was constructed using as a reference Cochrane reviews13,15 with variations of MeSH keywords: martial arts, elderly, and gerontology. Duplicate articles were identified using EndNote and excluded.

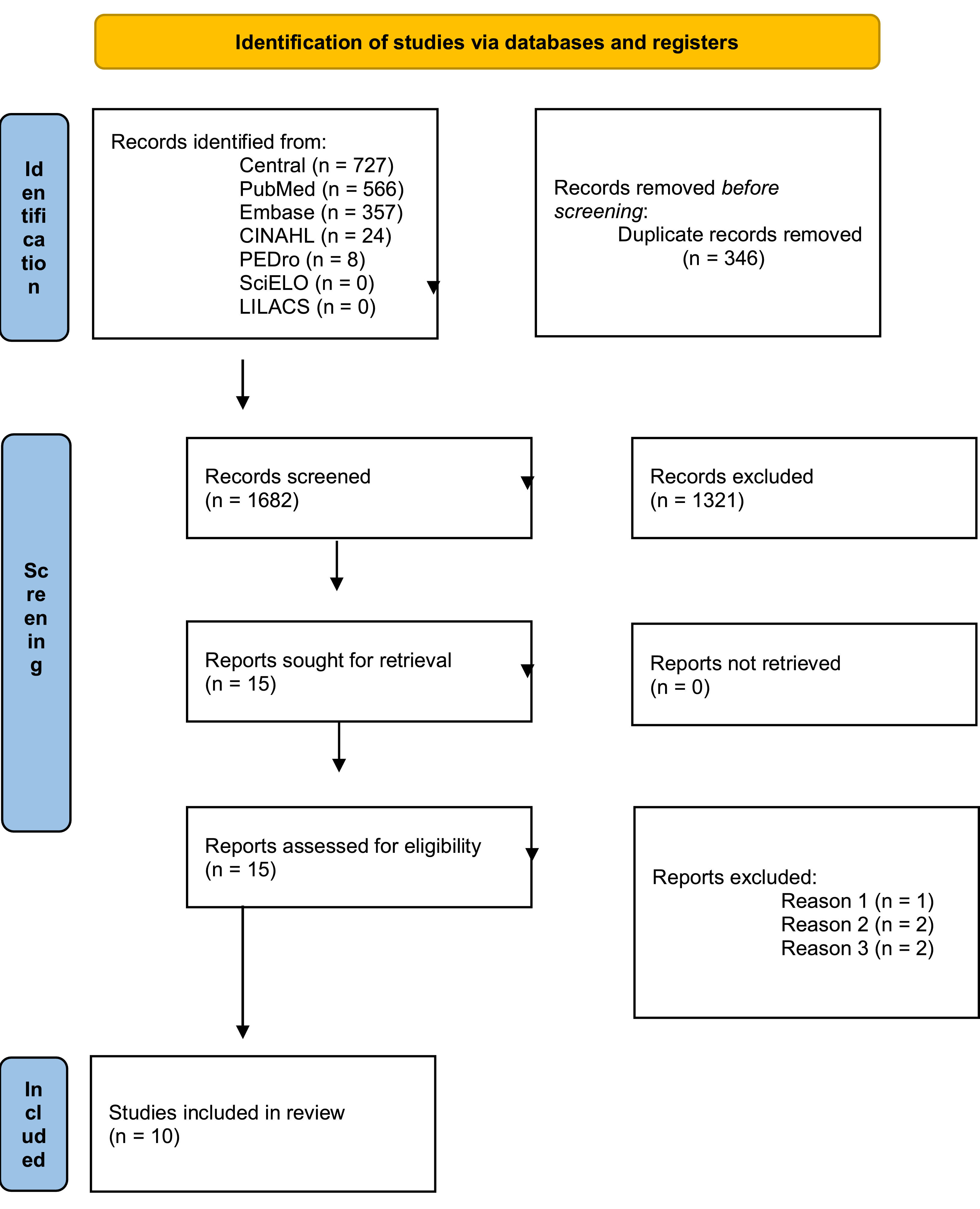

The articles were selected by three independent examiners (DLCM, JMRJ and LBBS) based on reading the title or abstract, and cases of disagreement were decided by consensus after discussion. In the absence of consensus, a fourth reviewer (LEGL) was consulted. Then, the potentially eligible articles were read in full, and the reference lists of all selected articles were consulted with the purpose of finding new publications for this review. The last active search occurred in July 2025. The article retrieval and selection process is shown in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only. Legend: Reason 1 ‒ Participants younger than 60-years of age, Reason 2 ‒ Participants had severe functional impairment due to Parkinson’s disease, and Reason 3 ‒ The study did not have a control group. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71.

Initially, 1682 articles were identified in the databases consulted: 727 in CENTRAL (Cochrane), 566 in PubMed, 357 in Embase, 24 in CINAHL and 8 in PEDro. No eligible studies were found in the SciELO and LILACS databases. A total of 347 duplicates were identified using EndNote and excluded. A further 1319 articles were excluded after reading the title and, in cases of doubt, after reading the abstract. Thus, 16 articles were selected for full-text reading and analysis. After analysing the studies, one article was excluded because the participants were not elderly, two articles were excluded because the participants were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and two articles were excluded because they did not have a control group. Thus, ten eligible articles were selected that included elderly individuals and evaluated the proposed outcomes, regardless of the time of analysis (Table 2).

Characteristics of the eligible studies.

N, Sample size.

The tool for the assessment of study quality and reporting in exercise (TESTEX) was used to assess the methodological quality of the randomized clinical trials and thus determine their level of bias. This scale was chosen because it evaluates clinical trials of physical exercise interventions, and as one of the quality criteria of other scales is the blinding of the participant and the researcher, its application with the type of intervention studied herein is more appropriate. Thus, the TESTEX is suitable for the present study.16

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system was used to assess the level of evidence and thus classify the strength of evidence. This system is used to evaluate outcomes individually, and the results yield recommendations that help specialists in clinical decision-making.17

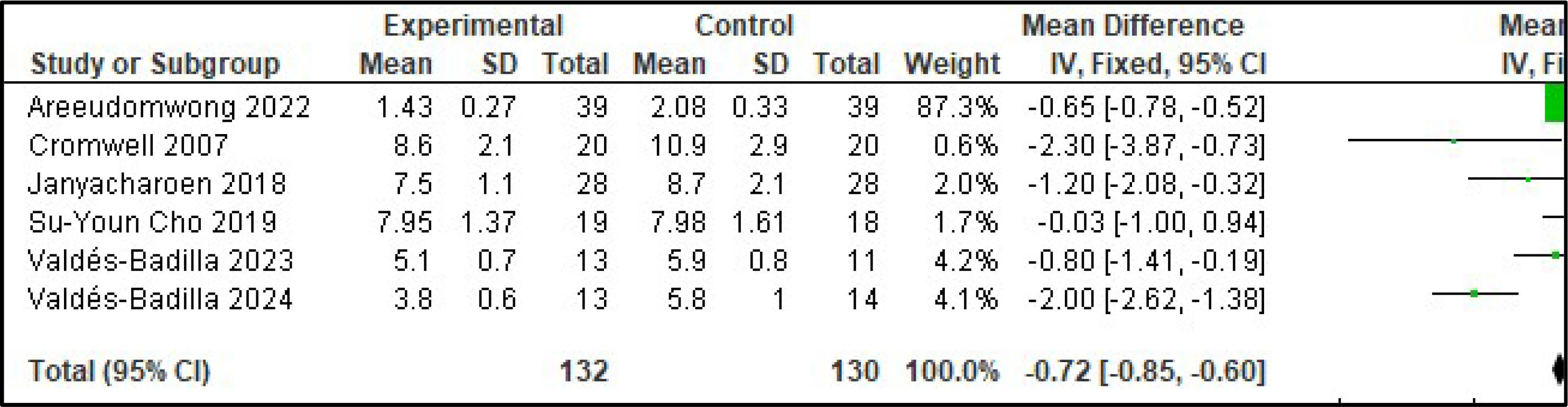

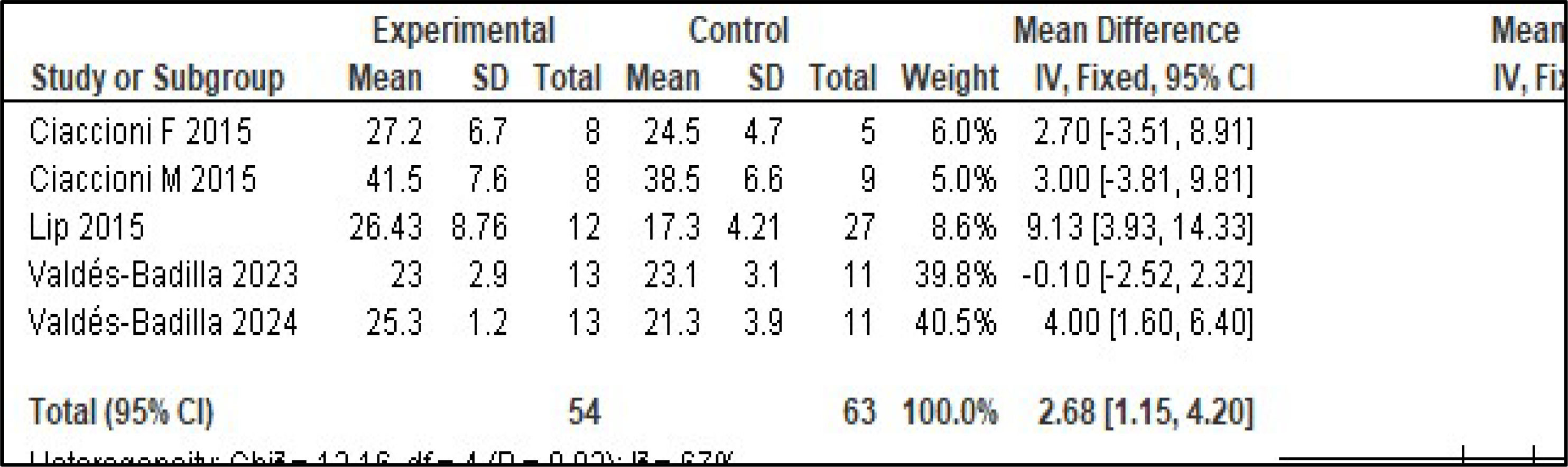

ResultsIt was not possible to perform a meta-analysis of quality of life with the eligible studies. However, it was possible to perform a meta-analysis of the assessment of postural balance18,19 (Fig. 2), functional mobility18,20-22,24,25 (Fig. 3), and handgrip strength19,23-25 (Fig. 4).

To assess the risk of falls, a meta-analysis of postural balance (Berg Balance Scale ‒ BBS) and functional mobility (Timed Up and Go Test ‒ TUG) was performed. The control group showed statistical superiority in the assessment of balance, but the martial arts group showed statistical superiority in the assessment of functional mobility [BBS ‒ heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.85; Chi² = 1.26, df = 1 (p = 0.26); I² = 20 %; global effect test: Z = 4.12 (p < 0.0001). TUG ‒ heterogeneity: Chi² = 24.65, df = 5 (p = 0.0002); I² = 80 %; test for overall effect: Z = 11.33 (p < 0.00001)]. To assess muscle strength, a meta-analysis of handgrip strength was performed, and the control group showed statistical superiority [heterogeneity: Chi² = 12.16, df = 4 (p = 0.02); I² = 67 %; test for overall effect: Z = 3.44 (p = 0.0006)].

Second, in the evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies (TESTEX; score 0/12) (Table 3), the studies showed fair methodological quality: Janyacharoen, 518; Lip, 319;; Areeudomwong, 520; Su-Youn Cho, 621; Cromwell, 522; Ciaccioni, 423; Youm, 426; and Kujach, 5.27 However, two studies exhibited high quality: Valdés-Badilla, 10.24,25

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the randomized clinical trials (TESTEX).

Legend: 1 — yes; 0 — no; Risk of bias — the higher the score, the lower is the risk of bias.

The methodological control in the studies directly influenced the quality of evidence on the outcomes. In the evaluation of the level of evidence of outcomes (GRADE system) (Table 4), all outcomes exhibited low clinical certainty, severe risk of bias due to nonblinding of raters, and severe data imprecision due to the low number of participants assessed.

GRADE evaluation of the methodological quality of the primary and secondary outcomes.

CI, Confidence interval; MD, Mean difference; severe (a) No blinding of the evaluators; severe (b) Total number of participants in the comparison is below the optimal information size.

When analysing the general state of the art of martial arts interventions for elderly people, it was possible to observe that there is a lack of studies on the subject and that, according to TESTEX scores, most studies have low methodological control due to challenges with regard to masking the interventions, thus increasing the level of bias in their results. The low number of participants in the groups also reflects negatively on GRADE scores because it makes it difficult to extrapolate the results to the external population. The results with a low level of evidence indicate low confidence in the effect; however, the results of future studies should have a significant impact on the estimation of the effect.28

Risk of fallsTaking into account that the event with the highest risk of falling is a dynamic task, it is necessary to have good reach and functional mobility to be able to maintain balance during motor performance. Therefore, it is understood that having good functional control decreases the risk of falls.29 Thus, when analysing the meta-analysis of studies that evaluated the functional mobility of the elderly who received a martial arts intervention, the results showed significant improvement in the intervention group compared to the control group.18,20-22,24,25 Janyachoren18 and Areeudomwong20 evaluated the effect of interventions involving the ancient ritual dance of Thai boxing, Muay Thai. Cho21 and Cromwell22 evaluated the effect of interventions involving Taekwondo, and Valdés-Badilla adapted Taekwondo.24,25 In a systematic review conducted to evaluate the effect of Tai Chi in frail older adults and those with sarcopenia, older adults who received the intervention showed better performance on mobility tests, sitting down and standing up from a chair in 30-seconds, and physical activity, with a decrease in the number of falls and fear of falling.30

However, the results of the meta-analysis of the studies that used the BBS (Berg Balance Scale) showed significant improvement in the control group compared to the ancient Thai boxing group18 and compared to the Ving Tsun group.19 Among the studies analyzed, Janyachoren18 reported a significant result for martial arts in the TUG test and a significant result for the control group in the BBS evaluation. This result was not expected because in another systematic review that evaluated balance,31 a significant result in the TUG test was followed by a significant result in the BBS. The low methodological quality of the studies analyzed, as determined using the TESTEX (Table 2), may be the reason for the divergence in the results found.

Muscle strengthThe results of the meta-analysis of the evaluation of handgrip strength showed significant improvement in the physically active control group compared to the intervention group.19,23-25 Lip19 studied the effect of one hour of Ving Tsun training per week for 12-weeks, Ciaccioni23 studied the effect of one hour of Judo every 15-days for 16-weeks, Valdés-Badilla24 studied the effect of one hour of adapted Taekwondo three times a week for 16-weeks and for eight weeks.25 Handgrip strength is an important marker of general health status because a decline in this index is associated with decreased cognition, mobility, and functional status and increased mortality in elderly individuals.32-34 Thus, the result indicates that the practice time used was not sufficient to generate a significant difference from the physically active control group.

Quality of lifeIn the present study, only one randomized clinical study was identified that used the WHOQOL-BREF,18 and one research group used the SF-3624,25 to assess the quality of life of participants, thus making it impossible to perform a meta-analysis. The Muay Thai ritual dance study18 showed that 12-weeks of practice improved the quality of life of elderly participants in the physical and psychological domains. The adapted Taekwondo studies.24,25 showed that eight weeks of practice increased the mental health and general health dimensions, and 16-weeks improved the body pain and general health dimensions. The results are consistent with those of a study in which a higher level of physical activity was associated with a better perception of quality of life among elderly people with different health conditions.35 A similar result was found in an observational study in which the short version of a quality-of-life questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) and a specific version for the elderly (WHOQOL-old) were used. In that study, compared to physically active elderly people, elderly Kendo practitioners reported better quality of life, especially in the physical domain but also in the environment domain, in addition to the social participation and past, present and future activity domains.36

ConclusionCompared with control interventions, interventions involving Taekwondo (adapted) and Muay Thai (ritual dance) led to significant differences and, therefore, should be considered as approaches to improve the functional mobility of elderly individuals. The state of the art of martial arts interventions reveals that there is little academic production regarding martial arts interventions and successful ageing, and that the results have a low level of evidence. Thus, future studies with better methodological control may modify the results obtained in this study.

Authors’ contributionsMendonça DLC was responsible for the study design, data collection, data analysis and preparation of the manuscript; Raider Junior JM was responsible for the study design, data collection, data analysis and critical review of the manuscript; Silva LBB was responsible for the data collection and data analysis; Alonso AC was responsible for the study design and critical review of the manuscript; Greve JMD was responsible for the study design and critical review of the manuscript; and Garcez-Leme LE supervised the study and was responsible for the study design and critical review of the manuscript.

FundingThere was no funding for the preparation, execution, or submission of the study.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article is the result of a thesis for obtaining a Doctor of Sciences of Musculoskeletal System Sciences degree from the Orthopedics and Traumatology Program of the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo.