Women play an important role in entrepreneurship although feminine entrepreneurship is lower than masculine entrepreneurship. However, the distance between both entrepreneurship rates (male–female) varies across countries because of the influence of different roles and stereotypes on entrepreneurial behavior. In order to understand those differences, this paper analyzes the distance between male and female entrepreneurship from a cultural perspective in 55 countries. Findings show that there is no clear relation between country masculinity and gender entrepreneurship breach.

Las empresas creadas por mujeres representan una parte sustancial del emprendimiento, a pesar de que los hombres superan a las mujeres en la tasa de creación de empresas. A pesar de ello, un análisis de las cifras a nivel mundial muestra que la distancia entre tasas de emprendimiento según el género varía en función del país analizado. Esto es así debido a que los roles y estereotipos influyentes condicionan una conducta más o menos emprendedora. Para analizar estas diferencias en este trabajo se estudia la distancia existente entre el emprendimiento de hombres y mujeres desde una perspectiva cultural utilizando una muestra de 55 países. Los resultados observados no permiten establecer una relación entre el nivel de masculinidad del país y la brecha de género en emprendimiento, tal como habíamos propuesto.

Since entrepreneurship is considered as a source of economic development, innovation and growth, the study of factors that influence rates of creating new companies has become an important issue on the agendas of economists, researchers and politicians in most countries. Understanding the role played by the social, cultural and economic factors in entrepreneurship is key to comprehend how to encourage culture and entrepreneurial behavior.

There is a widespread appearance of policies and actions supporting business creation by women due to the lower proportion of women related to men who decide to start a business is lower (Minniti, 2010; Singer, Amoros, & Moska, 2015).

A first explanation for this stems from Sociology. From this perspective, it is stated that women are less entrepreneurial than men due to stereotypes and roles that are attributed according to their gender and move away from attitudes of domain or achievement, placing them in roles near housework, childcare and their elders (Eagly, 1987). Also, within this perspective other researches say how men are positioned in society today, through certain patterns, ideologies and speeches reinforce its dominant position in the labor market and relegates women to the background (Connell, 1990).

Secondly and closely related to the above, understanding the national culture is essential to analyze how each country values and rewards the behaviors that promote entrepreneurial behavior. In this sense, in those countries where social roles are closer to competitiveness, ambition and achievement, that is to say, where highlight the roles attributed to the male group would be expected lower rates of female entrepreneurship (McGrath, Macmillan, & Scheinberg, 1992; Shane, 1992, 1993).

From these perspectives, this research seeks to deepen a basic question in entrepreneurship research, why more men than women become entrepreneur? Likewise, an international vision of entrepreneurial activity rates masculine and feminine will be offered, analyzing them from a cultural perspective.

To achieve the objectives, the work is structured as follows. First, the sociological perspective is analyzed through gender roles and hegemonic theory. Secondly, based on the theory developed by Hofstede (1980), the influence of culture is discussed in the entrepreneurial orientation of individuals in a country. This revision proposes the existence of the relationship under study. Next, this relationship is studied with a sample of 55 countries. The paper ends with a discussion of the results and analysis of the implications of the results.

Theoretical framework and research hypothesesGender roles and entrepreneurshipThe existing literature on gender and entrepreneurship is quite extensive, finding a broad consensus on the fact that men are those who start businesses to a greater extent (Eagly, 1987; Langowitz & Minniti, 2007; Mckay, Phillimore, & Teasdale, 2010; Themudo, 2009).

This greater propensity of the male group is explained by different theories. Currently, the most accepted theory is the social role developed by Eagly (1987). This theory states that people, to be socially acceptable, must develop certain stereotypes. Some of these stereotypes are attributed according to their gender. Thus, gender stereotypes refer to preconceived ideas and to previous judgments that have a significant emotional charge and reflect the views of society on both men and women, so that the male group is more likely to have higher domain or achievement attitudes, while women are closer to care behaviors and docility.

The theory of social role has its applicability in explaining the observed differences in gender behavior and is based on the theory of gender role (Eagly, 1987). In itself, this theory is based on patterns of each gender, appealing to social customs that define appropriate behavior for women and men (Eagly, 1987; Eagly & Carli, 2003; López-Zafra, García-Retamero, & Eagly, 2009). Specifically, social customs put women in the home, doing housework and caring for children and elderly, while men are responsible to work and bring home money to support the family. Therefore, the male group is configured as the ideal to start and run businesses (Bird & Brush, 2002), while women find barriers in exploiting business opportunities (Carter & Rosa, 1998).

Other authors, like Connell (1990) developed the theory of gender role, arguing that the gender-related stereotypes of the individual derive what he calls ‘hegemonic masculinity’. Hegemonic masculinity is how men are positioned in society today, through certain patterns, actions, ideologies and discourses that allow them to gain and maintain an advantage over women (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005).

The argument of hegemonic masculinity reaffirms the division that occurs in the labor market, watching men as ideal workers and qualifying women as secondary labor versus male (Acker, 1990; Eagly & Carli, 2003; Furst & Reeves, 2008; Godwin, Stevens, & Brenner, 2006; López-Zafra et al., 2009). Therefore, in the business field a hierarchical order is established, where men are seen as the standard and women as the exception to the rule (Eddleston & Powell, 2012; Godwin et al., 2006; Gupta, Turban, Wasti, & Sikdar, 2009).

It seems logical that entrepreneurship is also represented with the attributes that characterize the male group (Bird & Brush, 2002; Díaz, Hernández, Sánchez, & Postigo, 2010; Eddleston & Powell, 2012; Gupta et al., 2009). The argument of hegemonic masculinity explain why males are more likely than women to perform tasks related to the business world, while they tend to occupy less attractive business niches for males (Hechevarría, Ingram, Justo, & Terjesen, 2012). It also states that there are greater difficulties in adapting women to the areas where the emotional component is forgotten. Working in a business environment is rated as more rational and less emotional. On the contrary, the home is considered the main emotional domain with a less rational component (Acker, 1990).

On the other hand, when it comes to starting a business, access to capital and necessary resources are also different for men and women (Díaz et al., 2010; Lamolla, 2007; Sampedro & Camarero, 2007). Authors like Godwin et al. (2006) argue that women are discriminated when trying to access to the resources needed for their business. Usually, female entrepreneurship is stereotyped with features that are incompatible with those observed in entrepreneurs who have achieved success in their business activities. This means that, sometimes, entrepreneurial women receive fewer credits than men because of unfair prejudice such as women are not qualified to manage money (Bruni et al., 2004).

Therefore, the existence of men symbolic domain lies in the genre attributes associated with it. Heilman analyzes this fact in 1983, by developing the so-called theory of adjustment. This theory suggests that when a certain role in the organization, such as the administrator, is associated with men, women are seen as not ‘fit’ into the role because they are not perceived as having the necessary skills to perform their duties in an efficient manner (Godwin et al., 2006).

Therefore, as mentioned above, the lowest rates of business creation in the female population may be due to the unequal competences between men and women that promote patriarchal society. Also men would start a business activity with the main objective of maximizing their own economic benefit, while women feel more comfortable in service activities that in addition have social and environmental objectives, that is to say, more intangible motivations, leading them in this way to be outside the productive area (Brush, 1992; Eddleston & Powell, 2012; Godwin et al., 2006; Mueller & Conway Dato-on, 2008).

Cultural dimensions and entrepreneurshipThe degree to which the residents of a country have positive opinions toward entrepreneurship and to the creative and innovative thinking to create value is determined by culture, values, beliefs and norms of a country (Busenitz, Gómez, & Spencer, 2000; George and Zahra, 2002; Hayton, George, & Zahra, 2002; McGrath et al., 1992).

The analysis of the influence of culture on entrepreneurship has received increasing attention in the literature (Hayton et al., 2002; McGrath & Macmillan, 1992; Mitchell et al., 2000; Mueller & Thomas, 2001; Mueller et al., 2002; Shane et al., 1991). These investigations are based on that human behavior is not random, that is to say, some behaviors can be predicted, and certainly culture shapes thoughts, feelings and reactions (McGrath et al., 1992). One of the models which have supported much of the research that try to analyze the influence of culture on the level of entrepreneurship in the country is developed by Hofstede (1980, 1991, 2003). Although their research does not focus specifically on the creation of enterprises, analysis of differences in national cultures showing evidence of differences and similarities through the cultural patterns of the country is particularly useful. Specifically, according to this author culture can find their origin in the answers to common human problems through six dimensions that differentiate countries. These dimensions are: (1) power distance; (2) individualism collectivism; (3) masculinity/femininity; (4) control of the uncertainty; (5) long-term orientation/short term; and (6) the indulgence and restriction. The influence of these dimensions on entrepreneurship can be exercised both collectively through the awareness of institutions on the importance of entrepreneurship, and individual levels about the characteristics and attitudes of people in a particular place (Hofstede et al., 2004). On the other hand, as we have seen, one of the key variables of female entrepreneurship is related to the assignment of gender roles, variable that is collected by the Hofstede model (1980, 1991, 2003) as the masculinity–femininity dimension shows the distribution of emotional gender roles. So, this dimension reflects the importance that grants to a culture with stereotypically masculine values such as assertiveness, ambition, power and materialism, and stereotypically feminine values, as the emphasis on human relations. Cultures with a high value on the scale of masculinity tend to have more pronounced gender differences. Accordingly, it is expected that countries with a masculine orientation, have higher rates of entrepreneurship, while in those where feminine values prevail there is a greater tendency toward paid employment (McGrath et al., 1992; Shane, 1992, 1993).

However, the relationship between gender distinction of people and their cultural beliefs is still a confusing issue. On the one hand, some studies have shown that effectively in the more masculine societies, women decrease their participation in undertaking when they feel distant from the prevailing values in their society and therefore they are less able to create a company (Quevedo, Izar, & Romo, 2010). Other studies suggest that in places with high masculinity women are impregnated over those values that make up their culture and decide to undertake entrepreneurial projects more easily than in countries with more feminine cultures (Cardozo, 2010).

Thus, on the basis of the above, the study of the existence of a relationship between the level of masculinity of a country and the differences in entrepreneurial behavior of men and women is proposed.

MethodologySample and data collectionIn this work the unit of analysis is the individual, analyzing data collected by the GEM project in 2013. These were collected through telephone interviews or face-to-face, with a standardized questionnaire. We used a representative sample of adults (18–64 years) in 55 countries.

In order to ensure that respondents accurately reflect the established population, the GEM assigned to each respondent a weighting factor that takes into account gender and age. Specifically, the distribution by age and sex of the samples were compared with the database of the U.S. Census International Database 2002. Thus, weights were calculated to coincide with the sample of this standard source of estimates of structure population. For more information on the GEM and methodology go to Reynolds et al. (2005).

VariablesLevel of masculinity: To measure the variable about the country's culture in relation to their degree of masculinity or femininity we consider the value of the index of masculinity (MAS Index) developed by Hofstede for each of the countries in the sample. The countries that have low masculinity index are considered feminine oriented countries, which means a smaller difference in gender roles.

On the contrary, those countries that have a high score are those with a masculine orientation and therefore reflected in its culture a greater difference between the roles associated with each sex. The countries with intermediate values are those considered moderately female if you have a relatively low score, or moderately male if the score is higher.

Gender gap: With this variable, the distance that exists between male entrepreneurship rate, generally higher, and feminine is measured. This is calculated as a variation rate between the two rates of entrepreneurship.

Level of development of the country: Another variable that we considered is the degree of development in which each country is. This variable was obtained from the classification made by GEM (2013), among underdeveloped countries whose engine development lies in the factors of production, developing countries and developed countries.

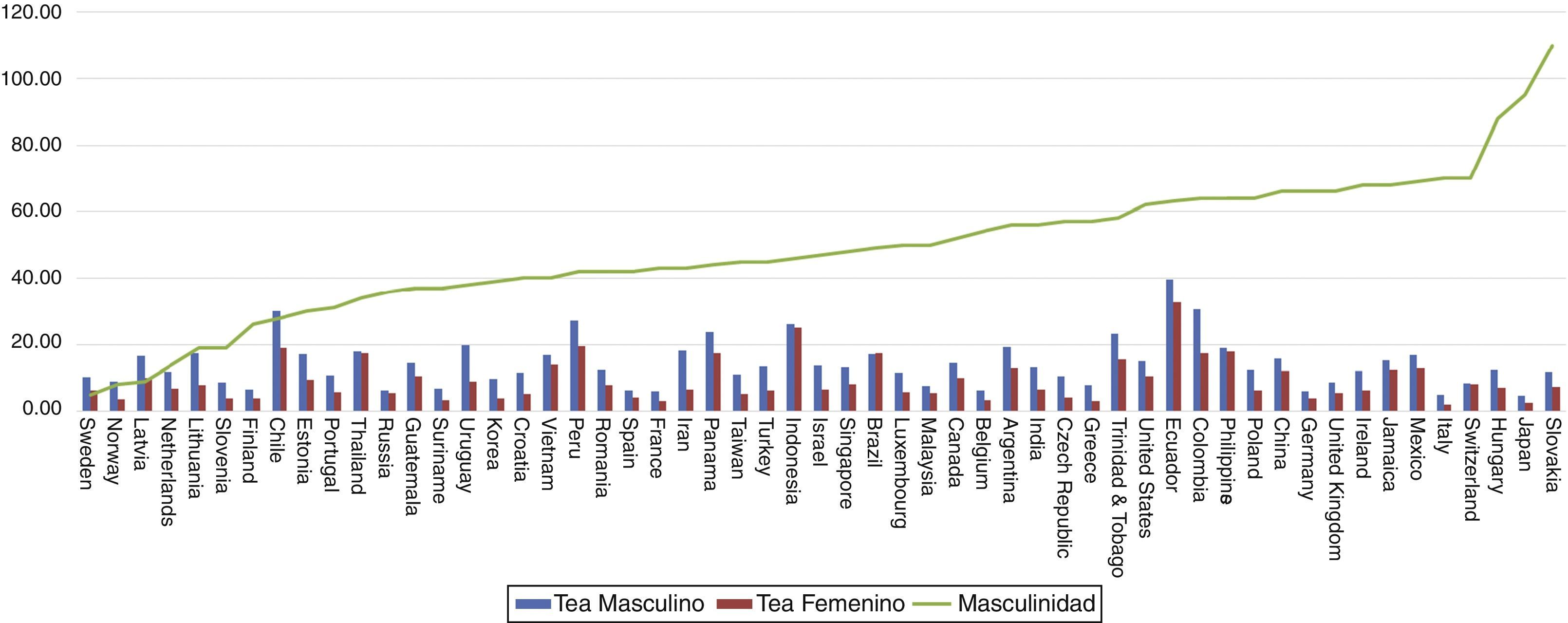

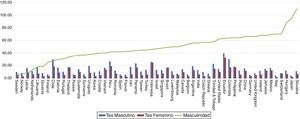

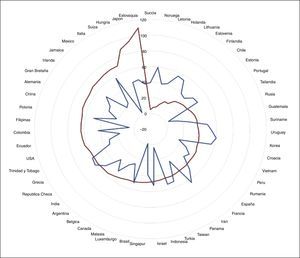

ResultsThen, in Fig. 1, the relationship between levels of masculinity of the sample countries with their respective rates of male and female entrepreneurship is shown.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, there is no relationship between levels of masculinity and entrepreneurship rates. So that the level of masculinity does not seem to be a dimension of culture that affects directly the rate of entrepreneurship in the country. In order to compare the levels of masculinity of the countries in the sample and different gaps of entrepreneurship by gender reason that have the same, we have distributed the countries according to their level of masculinity, based on the classification made by Hofstede in four levels: Female countries, moderately feminine countries, moderately male countries and male countries.

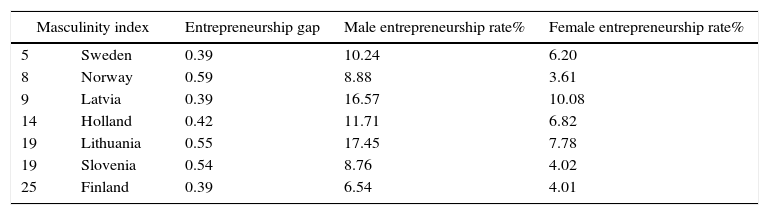

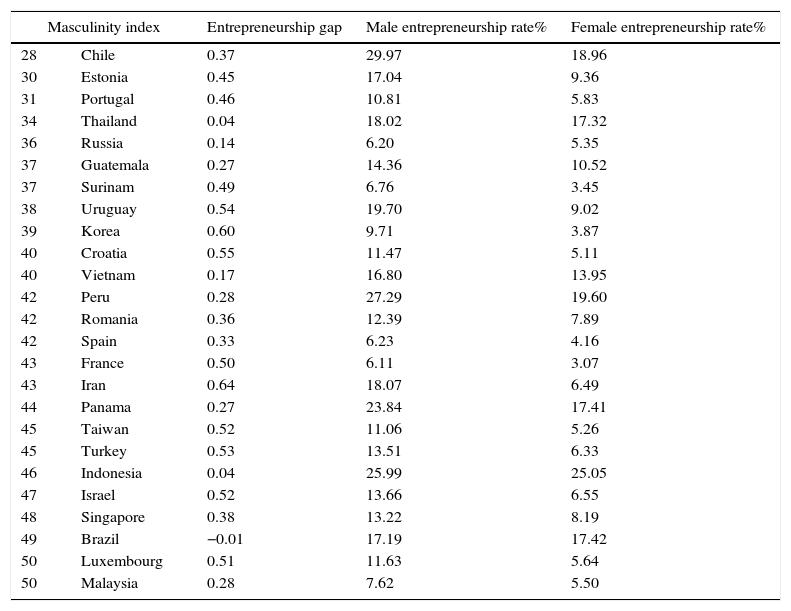

Among the countries with lower level of masculinity, and therefore considered as countries that have a cultural predominance of female values (Table 1), we find a group of European countries, particularly called Nordic countries. These countries also have in common the fact that they belong to the group of countries in a state of development 3 and that therefore its development is based on innovation. Low levels of masculinity in developed countries indicate that there are no large differences in gender roles in the country. For example, Norway has a very low level of masculinity and the gender gap is the highest in the group (0.59).

Countries with very low level of masculinity in the Hofstede scale (0–20) (Index of low Masculinity in the Hofstede scale (0–25)).

| Masculinity index | Entrepreneurship gap | Male entrepreneurship rate% | Female entrepreneurship rate% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Sweden | 0.39 | 10.24 | 6.20 |

| 8 | Norway | 0.59 | 8.88 | 3.61 |

| 9 | Latvia | 0.39 | 16.57 | 10.08 |

| 14 | Holland | 0.42 | 11.71 | 6.82 |

| 19 | Lithuania | 0.55 | 17.45 | 7.78 |

| 19 | Slovenia | 0.54 | 8.76 | 4.02 |

| 25 | Finland | 0.39 | 6.54 | 4.01 |

Table 1 shows the results of the gap existing undertaking for these countries where the level of masculinity is very low. These countries show a gender gap in the entrepreneurship similar rates, although no increase is observed from the same. In this group, there are also two countries (Latvia and Lithuania) that are developing, and therefore have a lower level of development in the Nordic countries. In this case, it does seems more evident the fact that greater masculinity (9 and 19 respectively) corresponds to greater gender gap in the entrepreneurship rates (0.39 and 0.55).

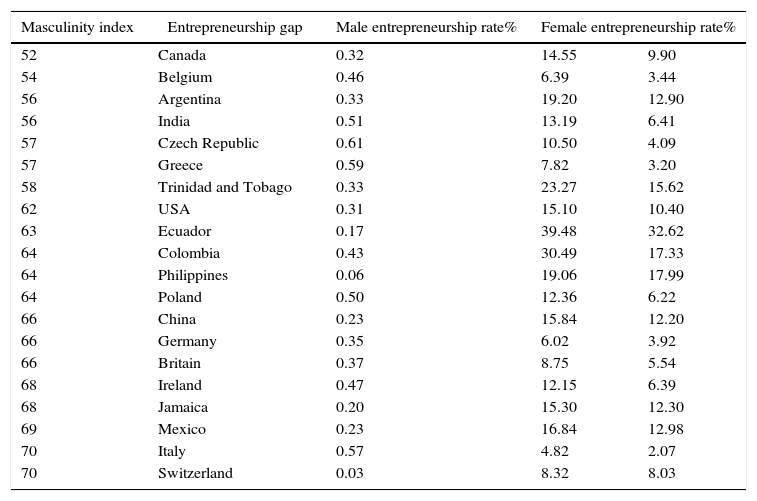

Table 2 shows the differences in gender gap of Entrepreneurship by gender associated to countries with low masculinity in the Hofstede scale (25–50). This would lead, as proposed, that the gap between male and female entrepreneurship is lower than in the previous group of countries. However, this group presents major differences between the gender gap in entrepreneurship in different countries.

Countries moderately female (Masculinity index in the medium-low Hofstede scale (25–50)).

| Masculinity index | Entrepreneurship gap | Male entrepreneurship rate% | Female entrepreneurship rate% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | Chile | 0.37 | 29.97 | 18.96 |

| 30 | Estonia | 0.45 | 17.04 | 9.36 |

| 31 | Portugal | 0.46 | 10.81 | 5.83 |

| 34 | Thailand | 0.04 | 18.02 | 17.32 |

| 36 | Russia | 0.14 | 6.20 | 5.35 |

| 37 | Guatemala | 0.27 | 14.36 | 10.52 |

| 37 | Surinam | 0.49 | 6.76 | 3.45 |

| 38 | Uruguay | 0.54 | 19.70 | 9.02 |

| 39 | Korea | 0.60 | 9.71 | 3.87 |

| 40 | Croatia | 0.55 | 11.47 | 5.11 |

| 40 | Vietnam | 0.17 | 16.80 | 13.95 |

| 42 | Peru | 0.28 | 27.29 | 19.60 |

| 42 | Romania | 0.36 | 12.39 | 7.89 |

| 42 | Spain | 0.33 | 6.23 | 4.16 |

| 43 | France | 0.50 | 6.11 | 3.07 |

| 43 | Iran | 0.64 | 18.07 | 6.49 |

| 44 | Panama | 0.27 | 23.84 | 17.41 |

| 45 | Taiwan | 0.52 | 11.06 | 5.26 |

| 45 | Turkey | 0.53 | 13.51 | 6.33 |

| 46 | Indonesia | 0.04 | 25.99 | 25.05 |

| 47 | Israel | 0.52 | 13.66 | 6.55 |

| 48 | Singapore | 0.38 | 13.22 | 8.19 |

| 49 | Brazil | −0.01 | 17.19 | 17.42 |

| 50 | Luxembourg | 0.51 | 11.63 | 5.64 |

| 50 | Malaysia | 0.28 | 7.62 | 5.50 |

It is true that the group of countries with moderate female orientation, among which is Spain, is the largest (25 countries) and more heterogeneous in terms of levels of economic development of the countries.

Thus, it is observed as exist in this country group with a minimum gap, such as Brazil (−0.01) and with the particularity that it is the only country with higher rates of female entrepreneurship over male, while it has one of the highest scores on the masculinity index group. In this case, it does not seem to be a relationship between the increased level of masculinity and a greater gender gap in entrepreneurship.

On the other hand, the country with a larger gap in the group is Iran (0.64) whose level of masculinity (43) is high for the group and very similar to Brazil (49). So, in this group does not seem to be a relationship between the increased level of masculinity and the entrepreneurial gap.

If we consider the level of development of countries according to the classification made by GEM (2013), we find underdeveloped countries like Iran and Vietnam. Developing countries such as Chile, Estonia, Thailand, Russia, Guatemala, Suriname, Uruguay, Croatia, Panama, Turkey, Indonesia, Brazil and Malaysia. Or already developed countries such as Portugal, Korea, Spain, France, Taiwan, Israel, Singapore and Luxembourg.

However, the level of development does not introduce a greater explanatory value to the analysis of the relation, as we observed that countries with the same level of development and very similar levels of masculinity, have big difference in the gender gap as the case of Iran (0 64) and Vietnam (0.17).

The same is observed between developed countries with similar characteristics.

Spain has a medium level of masculinity (42) and a gender gap below the average for all countries analyzed (0.33), while France with an almost equal level of masculinity (43) have a significantly higher gender gap (0.50).

This would therefore be the group of countries that has a greater dispersion in the gender gap, which would invalidate the idea that masculinity, as a dimension of the culture of a country, affects entrepreneurial behavior of men and women the same, making that the gender gap in entrepreneurship is similar.

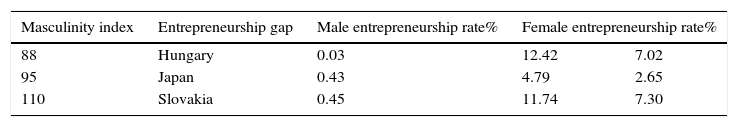

Moderately male countries are those having higher levels of masculine (50–75), as shown in Table 3, and including the gender gap between the minimum of Switzerland (0.03) and the maximum of Italy (0.57), both countries with the same level of masculinity and same level of development so that, in line with that seen in the previous groups, we cannot say that there is a relationship between both variables.

Countries moderately male (Masculinity index in the medium-high Hofstede scale (25–50)).

| Masculinity index | Entrepreneurship gap | Male entrepreneurship rate% | Female entrepreneurship rate% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52 | Canada | 0.32 | 14.55 | 9.90 |

| 54 | Belgium | 0.46 | 6.39 | 3.44 |

| 56 | Argentina | 0.33 | 19.20 | 12.90 |

| 56 | India | 0.51 | 13.19 | 6.41 |

| 57 | Czech Republic | 0.61 | 10.50 | 4.09 |

| 57 | Greece | 0.59 | 7.82 | 3.20 |

| 58 | Trinidad and Tobago | 0.33 | 23.27 | 15.62 |

| 62 | USA | 0.31 | 15.10 | 10.40 |

| 63 | Ecuador | 0.17 | 39.48 | 32.62 |

| 64 | Colombia | 0.43 | 30.49 | 17.33 |

| 64 | Philippines | 0.06 | 19.06 | 17.99 |

| 64 | Poland | 0.50 | 12.36 | 6.22 |

| 66 | China | 0.23 | 15.84 | 12.20 |

| 66 | Germany | 0.35 | 6.02 | 3.92 |

| 66 | Britain | 0.37 | 8.75 | 5.54 |

| 68 | Ireland | 0.47 | 12.15 | 6.39 |

| 68 | Jamaica | 0.20 | 15.30 | 12.30 |

| 69 | Mexico | 0.23 | 16.84 | 12.98 |

| 70 | Italy | 0.57 | 4.82 | 2.07 |

| 70 | Switzerland | 0.03 | 8.32 | 8.03 |

Among the developing countries of the group that share cultural traits derived from the denominated Latino culture, like Argentina, Ecuador or Colombia, it does not seem to be a relationship between masculinity and the gender gap.

In the first place, levels of masculinity are very similar between Ecuador and Colombia (63 and 64), but not like Argentina that has lower levels (56). And secondly, gender gaps are very different. Ecuador has the lowest gender gap (0.17), followed by Argentina (0.33) and finally Colombia where the gap is considerably higher (0.43).

Finally, only three countries in the sample show very high levels of masculinity, reflecting societies that give great importance to the stereotypically masculine values such as assertiveness, ambition, power and materialism, and where could be expected that the gender gap was higher. However, as shown in Table 4, it is not observed the largest gender gaps in all the countries analyzed as it was supposed, but in particular Hungary has one of the lowest gender gaps (0.03).

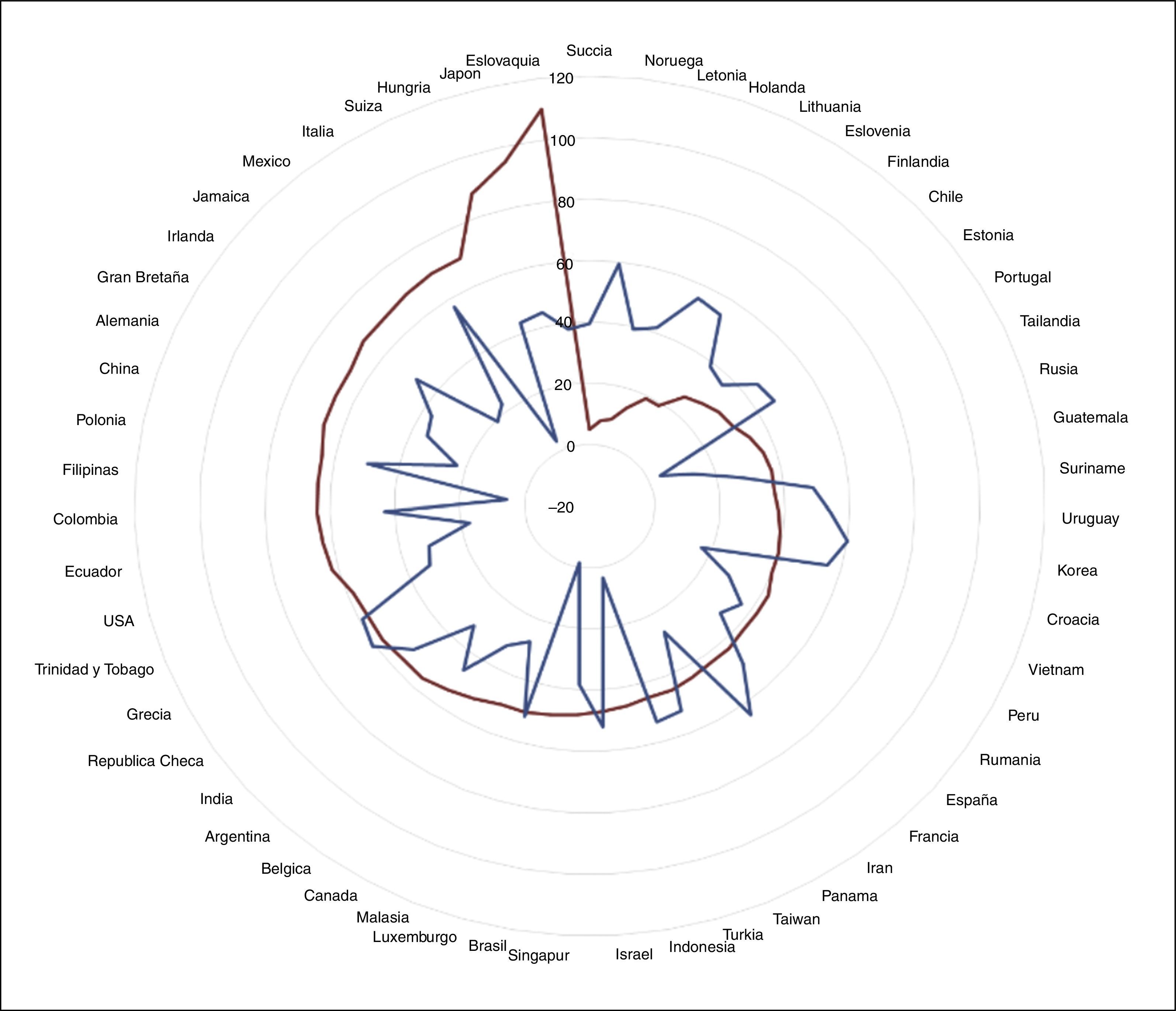

Fig. 2 shows the relationship between level of masculinity of the analyzed countries and the gender gap in entrepreneurship thereof. It shows more clearly the results discussed above. As you can see, and we have already mentioned above, a relationship between the level of masculinity of a country and the existing differences between the rates of male and female entrepreneurship is not observed.

ConclusionsThis paper aims to advance in the study of female entrepreneurship. The identification of the factors that condition and limit women's entrepreneurship is crucial for the development of itself. Much of the literature on entrepreneurship has traditionally focused on the study of these factors regardless of the differences that the promoters or detractors of the enterprise may have for gender reasons. The persistence in the different rates of male and female entrepreneurship has led in recent years to introduce gender analysis of the constraints of this behavior, but almost always from an individual perspective.

So, this paper explores the differences between male and female entrepreneurship from a cultural perspective, given that cultural factors are considered of great importance among the constraints of entrepreneurship (GEM, 2014), and in particular female entrepreneurship.

In this regard, the role of stereotypes and gender roles keeps women away from domain or achievement attitudes related to entrepreneurial behavior, placing them in roles near the housework, childcare and their elders (Eagly, 1987), so that the prevailing gender roles in a country determine the entrepreneurial behavior of its population and in particular, the differences between male and female entrepreneurship (Pérez-Quintana, 2013).

From this point of view, culture is crucial in the identification and determination of gender roles in a country, and thus it is collected by the model of Hofstede (1980, 1991, 2003) by masculinity–femininity dimension. This dimension covers the distribution of emotional gender roles and reflects the importance that a culture granted to values stereotypically masculine such as assertiveness, ambition, power and materialism, and stereotypically feminine values, such as the emphasis on human relations. Cultures with a high value on the scale of masculinity tend to have more pronounced gender differences so can be expected to have higher rates of entrepreneurship, while in those in which prevail feminine values there is a greater tendency toward employment by companies (McGrath et al., 1992; Shane, 1992, 1993).

In order to study the influence of culture on the gender gap in entrepreneurship rates in a country, it has conducted an analysis of the relationship between the degree of masculinity and gender gaps of a sample of 55 countries.

However, the observed results are not sufficient to assert that a higher levels of masculinity determine a greater gender gap in entrepreneurship rates. This is in line with previous studies that suggest that in places with high masculinity women are impregnated over those values that make up their culture and decide to undertake entrepreneurial projects more easily than in countries with more feminine cultures (Cardozo, 2010).

This leads us to believe that a deeper analysis of sex identification with the gender role is necessary, since some studies point to an evolution in the stereotypes associated with the figure of entrepreneur (Pérez-Quintana, 2013).

It is also conceivable that there is an interaction of the cultural dimension of masculinity with other dimensions, as risk aversion or individualism, which would better explain the gender differences in entrepreneurial behavior.

The main limitation of this study is related to the exploratory character of it. Thus, it is an analysis of a situation in a moment of time, although the influence of culture on the identification of roles and their subsequent influence on entrepreneurial behavior would require a longitudinal analysis to collect the dynamics of the process.

It is also important the practical application of the results obtained to the designing of measures and policies, in some cases designed to palliate the effects of a suspected male culture on gender roles and women's entrepreneurial behavior.

This work is part of the project: “Women and Entrepreneurship from a Competence Perspective” (CSO2013 – 43667 – R), developed by the University of Murcia and Bradford (UK) and funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Madrid, Spain, 2014–2016).