The Patagonian weasel (Lyncodon patagonicus) is a small, rare, and little known carnivore. Its distribution, which includes several fossil and historical records, spans western Argentina and southern Chile. According to recent studies, its populations are declining, affecting its conservation. In this paper we report a new locality of occurrence for the species based on a photographed individual from Lihue Calel National Park, La Pampa Province. The importance of this record is that it is located 173km southwest from the nearest previously known reference, and helps to fill a wide gap in the center of its range, where there were no previous records.

El huroncito patagónico (Lyncodon patagonicus) es un carnívoro pequeño, raro y muy poco conocido. Su distribución, que incluye varios registros fósiles e históricos, se extiende por el oeste de Argentina y sur de Chile. Según estudios recientes sus poblaciones estarían en retracción, afectándose su conservación. En este trabajo se registra una nueva localidad de presencia para esta especie basada en un individuo fotografiado en el Parque Nacional Lihue Calel, provincia de La Pampa. La importancia de este registro radica en que se localiza a 173km hacia el suroeste de la referencia previa más cercana conocida y contribuye a rellenar un vacío amplio en el centro de su distribución geográfica, donde no existían registros previos.

The Patagonian weasel Lyncodon patagonicus (de Blainville, 1842) is a small carnivore that inhabits herbaceous and shrub steppes in arid and semiarid areas from Argentina and Chile (Larivière & Jennings, 2009; Osgood, 1943; Prevosti & Pardiñas, 2001; Schiaffini, Martin, Giménez, & Prevosti, 2013). In Argentina, it has a wide distribution from Salta to Santa Cruz Provinces (Díaz & Lucherini, 2006), while in Chile it occurs only at the southern tip of the country (Prevosti, Teta, & Pardiñas, 2009). This species is one of the smallest and least known carnivores from South America; it is difficult to observe in the wild due to its rarity and elusive habits (Prevosti & Pardiñas, 2001). Within this wide distribution, most of its records of occurrence in the Pampas, Espinal, and Low Monte ecoregions of central Argentina correspond to historical or fossil records (Prevosti et al., 2009; Schiaffini et al., 2013). A recent work has modeled the past and extant potential distribution of the Patagonian weasel and found that this species is experiencing a retraction in its area of occurrence, an issue that will affect the conservation of this rare mustelid (Schiaffini et al., 2013).

The aim of this work is to report a new locality for this species. The new locality fills a large gap in its geographic distribution and represents the third record for La Pampa Province (Argentina).

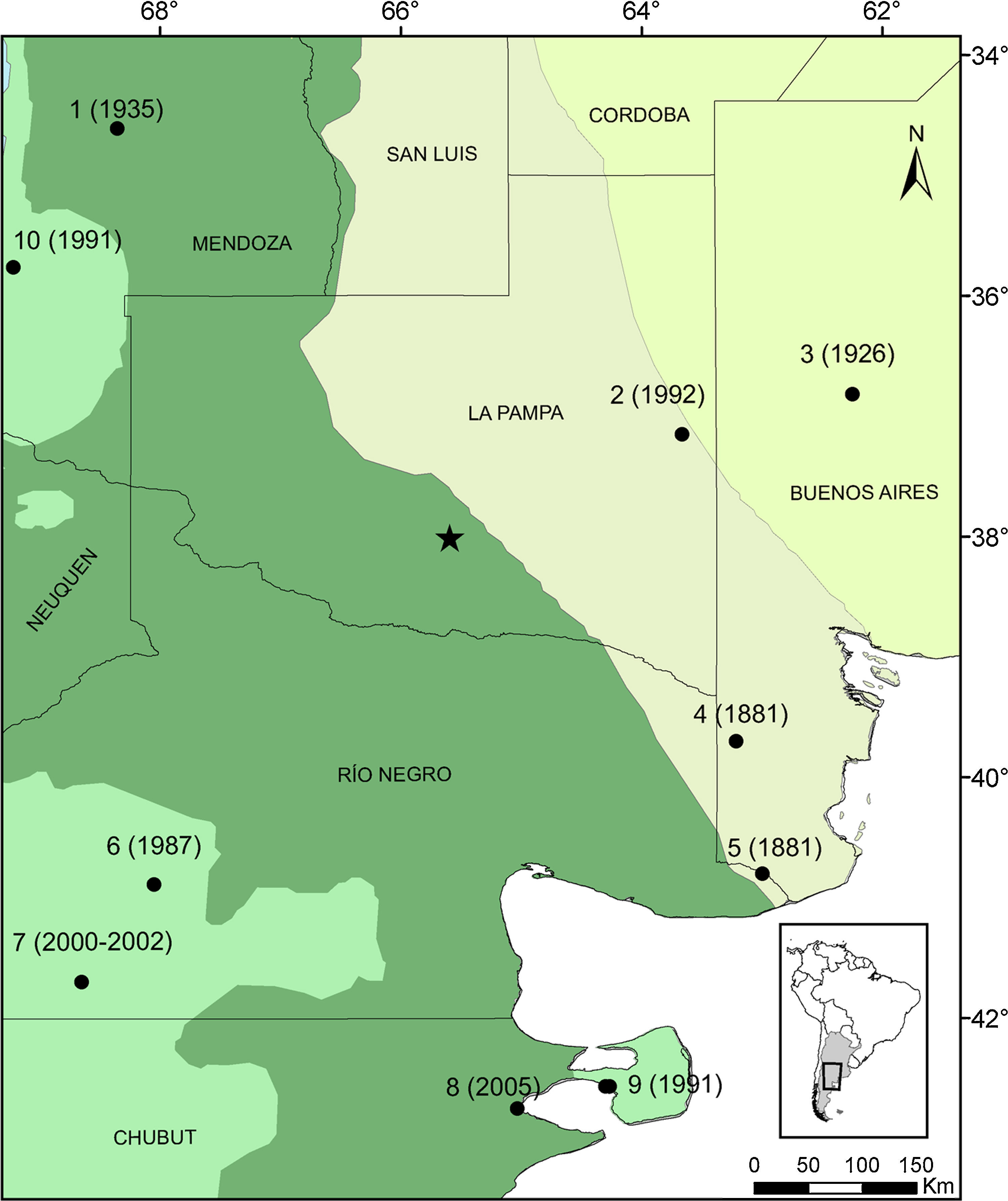

On July 11th 2015, a specimen of L. patagonicus was photographed by chance in Lihue Calel National Park (37°51′S, 65°32′W; LCNP), La Pampa Province, Argentina (Fig. 1). The climate in this park is semiarid, characterized by summers with mean temperature of 25.7°C, winters with mean temperature of 8.8°C, and mean annual rainfall of 416mm concentrated mostly during spring and summer (from September to April).

Map showing the new record for Lyncodon patagonicus (star) and the nearest previously recorded localities (black circles). Collecting year (Prevosti et al., 2009) is shown between brackets in the figure: (1) San Rafael (Roig, 1965), (2) Macachín (Prevosti & Pardiñas, 2001), (3) Bonifacio (Pocock, 1926), (4) Rincón Grande (Doering, 1881), (5) Carmen de Patagones (Doering, 1881), (6) 9km SE Los Menucos (Prevosti & Pardiñas, 2001), (7) Puesto Horno, Ea. Maquinchao (Teta, Prevosti, & Trejo, 2008), (8) Puerto Madryn (Prevosti et al., 2009), (9) Puerto Pirámide (Prevosti & Pardiñas, 2001), (10) Cueva del Tigre (Trajano, 1991). Terrestial ecoregions are colored as follows (from north-east to south-west): Humid Pampas, Espinal, Low Monte and Patagonian Steppe (Olson & Dinerstein, 2002).

The identification of the species was based on its general size (head-body 30–35cm, tail 60–90cm; measurements are approximate), long and slender body, short limbs, grayish-white pelage with a wide band of white fur on the top of head, and a dark brown pelage on the nape, cheeks, chin, throat, and limbs (Larivière & Jennings, 2009) (Fig. 2). The lesser grison, Galictis cuja, is similar to L. patagonicus, but the top of its head is grizzled-grayish, its throat and sides are black, and it has a diagonal, buffy, narrow stripe that runs from forehead to shoulder and separates dorsal buffy or gray from ventral black, clearly demarcating dorsum from ventrum (Yensen & Tarifa, 2003). Although available information indicates that L. patagonicus is active during twilight and night (Larivière & Jennings, 2009), it was observed during midday.

This species seems to be naturally scarce (Kelt & Pardiñas, 2008), and was categorized as “near threatened” in the Argentine Red Book (Díaz & Ojeda, 2000) and as “data deficient” in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Kelt & Pardiñas, 2008). These categories were primarily based on the scarcity of data, and the lack of published information on its geographic distribution, ecology, and main threats.

The new record reported here is located 194km SW from the nearest known record (Macachín, Atreuco, La Pampa Province; Prevosti & Pardiñas, 2001) and fills a gap in the center of its geographic distribution. The photograph was taken in Salitral Levalle, which is a typical salt-flat environment, where the vegetation is a halophyte shrubland with dominance of Allenrolfea vaginata, Atriplex undulata, and Cyclolepis genistoide. Lyncodon patagonicus occurs in herbaceous and shrub steppes and xerophytic woodlands, including salt flats such as those of the LCNP (Prevosti et al., 2009).

Potential distributional models based on recent (i.e., not fossil) data show a large high-prediction area for L. patagonicus in west-central Patagonia and other minor high-prediction areas that appear scattered in western Argentina and Chile (Schiaffini et al., 2013). Within this context, our record is not included in the current potential models generated by Schiaffini et al. (2013), a circumstance that merits some consideration. At least in part, this situation is the result of the low number of recent records (i.e., posterior to 1950) for this species in the Low Monte and Espinal. With the evidence at hand we cannot hypothesize if this situation reflects the absence of fieldwork by scientists in these areas, if it is the result of naturally low densities of this species in these ecoregions, or both (see Prevosti et al., 2009; Schiaffini et al., 2013). In contrast, potential distributional models based on Pleistocene and Holocene records made by Schiaffini et al. (2013), indicate that L. patagonicus occupied, under the more severe climatic conditions of these times, a broad area throughout central-eastern Argentina, including the Pampas, Espinal, and Low Monte. Thus the possibility that some populations in these ecoregions were relicts of a past, broad distribution, cannot be discarded.

We would like to thank to the ranger of Lihue Calel National Park, Miguel Angel Romero, for his help during our visit to the park.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.