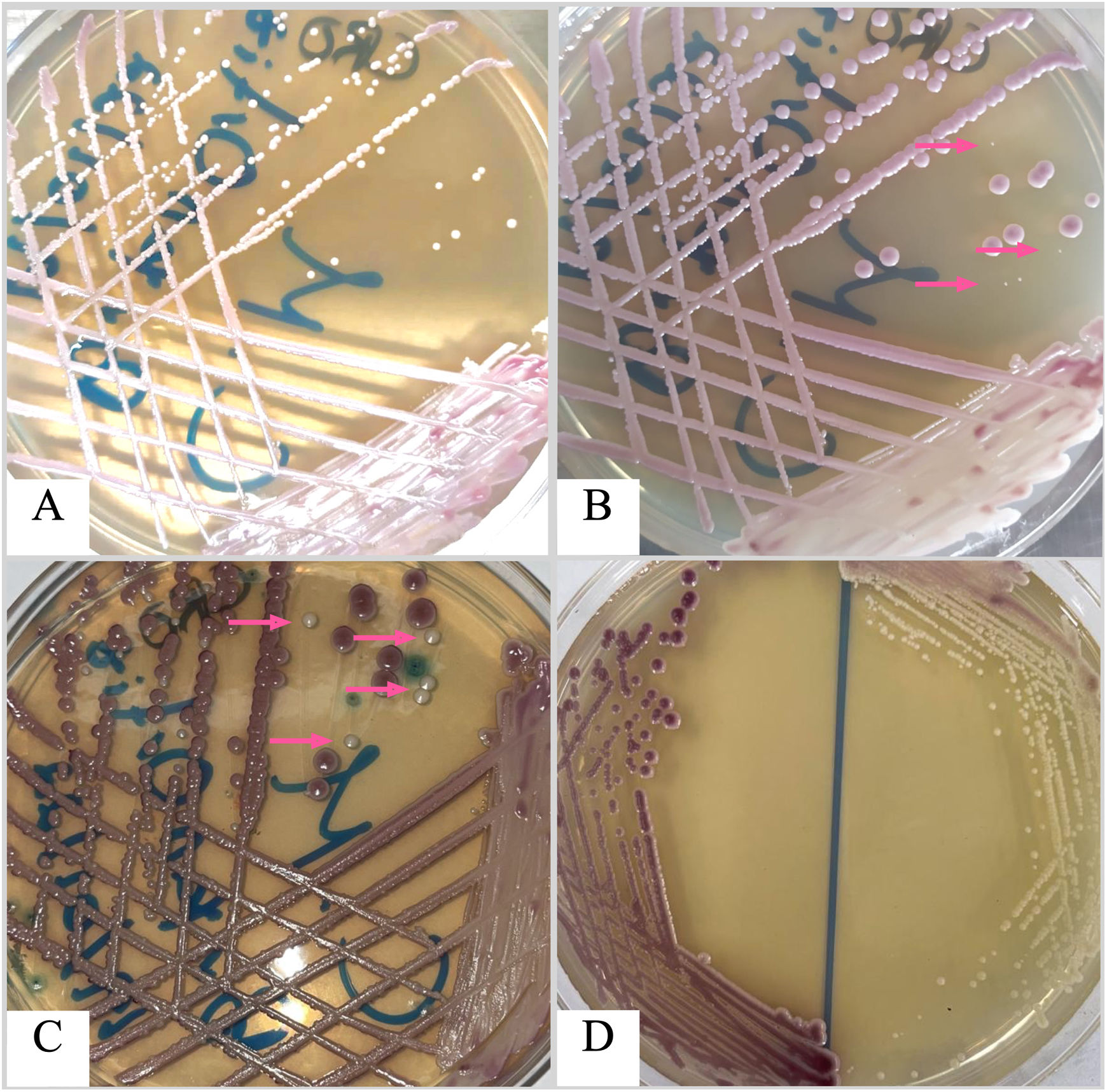

Here we present the case of a three-year-old boy with a history of total Hirschsprung's disease, diagnosed at four days of age, with eight previous surgeries for intestinal sub occlusion, causing short bowel syndrome and acid–base and electrolyte abnormalities. The patient was taken to the emergency room due to acute episodes of vomiting (more than five per day) after food intake. He had weight loss, did not tolerate oral administration, suffered diarrhea, was in a poor general condition, and suffered moderate dehydration. The patient was admitted initially for parenteral rehydration, but also underwent a new surgical gastrostomy with an intestinal splinting procedure. Nine days later, the patient developed fever of 38.5°C, and blood cultures were requested. Three days later a positive result with the BD BACTEC™ FX blood culture system was recorded (Becton, Dickinson and Co., NJ, USA). Gram stain technique showed yeast-like structures. Samples were cultured on blood agar, chocolate agar, MacConkey agar, and CHROMagar Candida®, and were incubated for 48h at 37°C. Bacterial cultures were negative; nonetheless, growth of yeast-like colonies was observed at 24h on blood and chocolate agar plates, with two different morphologies, rough white and creamy smooth white colonies. Both morphotypes were streaked on CHROMagar Candida® to get monoaxenic cultures to identify the yeasts’ species correctly, obtaining pure cultures with mauve and white colonies (Fig. 1). Yeast colonies were identified using the BD Phoenix yeast identification system, BD Phoenix™ M50 instrument.

Mixed growth of Candida glabrata (mauve colonies) and Candida parapsilosis (white colonies; pink arrow marks) on CHROMagar Candida plate incubated at 30 ̊C after 24 h of incubation (A); 48 h of incubation (B); and 72 h of incubation (C). D: Pure cultures of both isolates on CHROMagar Candida after 48 h of incubation.

The yeasts were presumptively identified as Candida glabrata species complex and Candida parapsilosis species complex. The ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) region of both isolates was sequenced according to previous works to discriminate between genetically related species.4 The sequences were trimmed and edited with the Geneious® 9.1.7 software and deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers OL604783 and OL604784. Sequences were analyzed with the NCBI BLAST tool, and yeasts were identified as C. glabratasensu stricto and C. parapsilosis sensu stricto. The minimum inhibitory concentration of antifungals was determined using the Sensititre YeastOne™ system (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Ltd., East Grinstead, United Kingdom) (Table 1). The patient was treated with fluconazole: 12mg/kg/day on the first day and 6mg/kg/day for another nine days.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and interpretation of the susceptibility of both isolates to the antifungals tested.

| Antifungal drug | Isolate Candida glabrata sensu strictoMIC (μg/ml) | Species susceptibilityCLSI/EUCAST | Isolate Candida parapsilosis sensu strictoMIC (μg/ml) | Species susceptibilityCLSI/EUCAST |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B | ≤0.12 | */S | ≤0.12 | */S |

| Anidulafungin | 0.015 | S/S | 0.5 | S/S |

| Caspofungin | 0.015 | S/** | 0.25 | S/** |

| Micafungin | 0.015 | S/S | 1 | S/S |

| Fluconazole | 0.5 | */S | 0.5 | S/S |

| Itraconazole | 0.03 | */** | 0.03 | */** |

| Posaconazole | 0.03 | */S | ≤0.008 | */S |

| Voriconazole | 0.015 | */S | ≤0.008 | S/S |

| 5-Fluorocytosine | ≤0.06 | */** | ≤0.06 | */** |

S: sensitive.

*CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute): version M60, second edition, does not include clinical cut-off points.

**EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing): E.Def 7.3, E.Def 9.4 and E.Def 11.0 procedures, version 3, 2022 do not include clinical cut-off points.

The vast majority of candidemia cases are monomicrobial, whereas mixed bloodstream Candida infections are less frequent.6,7 The prevalence of mixed candidemia is estimated to be less than 10% of all candidemia cases, being Candida albicans the most frequent causative species.1,6 In contrast, those cases caused by different Candida species are unusual. Patients with Hirschsprung's disease usually undergo multiple surgical interventions as the basis of their treatment in order to resect any damaged intestinal segment, always trying to preserve the sphincter's function.3 Multiple surgical interventions require a long ICU stay and exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics as prophylactic treatment. These scenarios, together with the intrinsic invasiveness of abdominal surgeries, predispose patients with Hirschsprung's disease to acquire infections by opportunistic pathogens such as Candida, which have increased their incidence in recent years and entail an attributable mortality of 10–15% in infants.2,5 We could not determine the origin of the mixed candidemia in the patient. It is plausible that the prolonged length of ICU stay, in conjunction with broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy, caused the infection; however, an endogenous source of contamination during surgery is also possible.