“… very little is known about auditing in practical, as opposed to experimental, settings” (M. Power, The Audit Society. Rituals of Verification, 1997)

Society has always needed professionals who are qualified to accredit products and services which have social or individual relevance. These individuals have gained the trust of the society to whom they serve over time. This is because of their knowledge but also because they are considered to be groups of individuals who can be trusted and who can carry out the assigned task in a professional and efficient manner.

Auditors are responsible for verifying the financial statements, which represent the financial position and the activity carried out by public and private entities. In order to satisfy users’ needs, the legislation contemplates an independent report prepared by auditors on managers’ stewardship of certain size entities. This is to protect those who lack expertise and haven’t access to transaction records and documentation. In fact, legislation and practice have determined that the auditor reports on the true and fair view given by the financial statements. This is not a report on the mere compliance with accounting standards but is raised to a higher level showing the role that reporting has is in the best interests of the users.

This paper, which is intended to be a long editorial Note, aims to examine what we know and what we need to know about the auditing activity. Its objective is to point out research areas that allow us to learn something more about the auditor's function, audit techniques etc. In particular, its objective is to examine the future of the auditing activity which is likely to be subject to very significant swings and changes. Scientific activity sometimes parts from unexplained observations or from facts that contradict existing theories with the prospect of completing them or advancing scientific knowledge in some way.

There are times when contradictions or irregularities crop up in auditing which need to be explained and resolved and very often require a rational explanation from academia. Below is a sample these facts.

The first fact arises from the exercise of judgement which has to be made by audit professionals as to whether the financial statements give a true and fair view or offer a faithful representation of the financial situation of the company. This view or representation, which is included as their opinion in the audit report, is not always achieved by strictly following the standards in vigour at the time of financial statement preparation. According to Zeff (2007) there is a growing tendency, mistakenly of course, to ignore the primacy of this principle over the rules. In simple terms, it is frequently considered that the true and fair view or fair representation is obtained by simply following the rules as demonstrated by Garvey (2012). However, there has been little research on the causes of this resignation by professionals.

Unfortunately, a more than insignificant representation of the members of the audit profession consider that their duty is limited to following certain rules and manuals. They believe that these procedures will provide them with guidance on how to do hundreds of checks, which will lead them to deriving a professional judgement without involving excessive mental effort or exercising scepticism. In any case, if the opinion to be issued is not favourable it can be discussed with the managers who have hired them, so that a comfortable balance is found by pointing out the indispensable failures but allows the audit engagement to continue in the future. DeFond, Lennox and Zhang (2018) describe cases where the credibility of the audit profession was damaged because it did not grant the primacy of the true and fair view or faithful representation over simply following the rules. They use examples which have been taken from the decisions of regulators and tribunals in real cases.

A second fact to be studied is the intrusion by the public authorities in an activity that half a century ago was exclusively private and was proud of its self-regulatory power. The professional mechanisms of self-control have not worked satisfactorily in any country, and thus have given rise to important administrative and judicial penalties which has displaced the professional institutes and put them under the microscope. From the time of the Enron scandal and the disappearance of the Andersen firm, governments and market supervisors have taken the role of policemen by closely monitoring the behaviour of auditors. This role was completely unthinkable in the past.

A separate group has been established for public interest companies because they require special supervisory control and therefore have to comply with specific audit obligations. In practice, it is necessary to perform research to discover whether this division is creating two different groups of auditors. There may be a tendency to divide auditors according to their knowledge, to their working capacity and seniority which in itself could create an entrance barrier harmful to the audit activity. This division would be especially damaging where audit firms are categorized according to classes by the type of audits they perform.

A third fact is the concentration of the audit market in the hands of 8, 7, 6… 4 large firms (Big N), which absorb most of the audit revenue in developed countries. The power and organization of these entities is at the expense of competition in price and quality because they centre their efforts on being recruited by clients regardless of the size of the company or the assignment. There doesn’t seem to be a solution, at least in the short term, to this apparent oligopoly which represents a risk to the image and continuity of the professional activity. Paradoxically, empirical literature is very adamant in supporting the idea that the Big N, no matter what its size, can and do achieve a higher level of quality (DeAngelo, 1981; Defond & Zhang, 2014).

A fourth fact is the reluctant attitude by auditors to assume their responsibility to be absolutely independent of the companies being audited apart from complying with the legal requirements. The legal system and market regulators demand an attitude of mental independence by this group of professionals. However, auditors of all sizes tend to offer support to entrepreneurs and administrators in their organizational and supervisory tasks and this attitude is normally welcomed by company management. It seems that the now perhaps old-fashioned and unattractive quality of independence which has constituted the core of an auditor's skillset is being substituted by sharing their vast knowledge and expertise.

A fifth and final fact we will deal with here is the paradox that some accounting professional service companies have become real businesses where the desire for profit and growth is prevalent over any other consideration, or at least it seems to be so. This change has occurred in just a few decades in a service where quality and the public interest of the service provided should be the maximum priority. This desire to grow and earn profits together with the seasonality of the audit activity has led professionals to offer other services with the audit engagement. In this way they not only obtain more income from these companies but it creates a bond between them. As a result, professional firms are transformed into lucrative businesses, and their leaders acquire a consultants’ mentality, whose main objective is to obtain profits (Zeff, 2003:280). Meanwhile, a more conscientious part of accounting professionals, as well as some professional organizations and regulators argue with great conviction that the auditor always works in the public interest.1 In fact, the Big N in the UK are planning on dividing their audit and consultancy services after receiving pressure to take action from the regulatory body which is concerned about transparency and audit quality (The Guardian, 2018).

In recent decades, attempts have been made to systematize research problems in auditing, for example, . Lesage and Wechtler (2012) analyzed and classified several thousands of articles which were published in the 25 most prestigious accounting journals in the English-speaking world between 1926 and 2005. In the 1940s and 1950s, research focused mainly on the characteristics of the profession, in the following two decades the concern was focused on auditor education and training. In the 1980s and 90s technical problems were analyzed, such as forming a judgmental opinion, audit procedures, applying contractual theory to auditing and customer relations. Around the turn of the century, concerns shifted towards international regulation, corporate governance, the entity as a going concern, as well as the risk of fraud and its non-detection. In the present decade, we could add to the previous list, the concern about obtaining audit evidence by using information technology, the relevance of internal control or the Audit Committee's role in the work of the auditor and the effects of inspections and supervisor scrutiny on the work of the auditor.

Research approachesThere are several ways to address the research task of the facts previously described. We examine three current proposals in order to systematize the approaches, which are not exclusive nor excluding of each other.

The first two are drawn from two recent calls for papers from academic journals, both of which correspond to two very different conceptions of academic research.

The first call2 comes from the European Accounting Review, (Special issue on “New directions in auditing research”). The journal belonging to the European Accounting Association (EAA) has taken a predominantly positive empirical tendency focusing on the global academic impact and the drawbacks of research done in Europe. It has succeeded in its mission, although sometimes this success has been at the cost of sacrificing more in-depth reasoning by giving priority to the formal perfection of statistical models and tests which conform to the theories prevalent on the other side of the Atlantic. We will call this the positive approach.

The second call3 is the counterpoint offered by the journal titled Critical Perspectives on Accounting. In this case, the call comes with a better indication of the objective to be achieved (Special issue on “Critical auditing Studies: Adopting a Critical Lens toward Contemporary Audit Discourse, Practice and Regulation”), which seems to require a deep and philosophical analysis to explain the attitudes and behaviours of auditors according to their origins and their consequences in both the short and the long term, without losing sight of what they call “the bigger picture” of this activity. For many social scientists, if science is not critical, it is not really science at all.

Critical Perspectives on Accounting, was born with the intention of challenging existing theories and academic practices. The journal fostered a nonconformist style which has evolved to a less radical position but not in any way less critical. It is published by a prestigious editorial (Elsevier) and is subject to scientific evaluations which their promotors didn’t especially believe in when they founded it in 1990. Critical research is related to the human, political and social complexities that play a role in accounting (and auditing) institutions, and where political interests have a major role in the outcome and evolution of the reality that is trying to be explained. We will call this methodology the institutional approach because of its link with scientific philosophy. This methodology can also be found in other prestigious journals such as Accounting, Organizations and Society or in the Journal of Accounting and Public Policy.

The list of topics suggested by the previous calls for papers will change when the subjects are received by the authors in due course. Both calls suggest interesting fields of research, but neither have a vocation to be an exhaustive list of areas to be attended to.

The third approach to be addressed is taxonomic: it is not the produce of an epistemology, but a descriptive grouping of audit research areas. The American Accounting Association (AAA) has developed a systematic classification of audit studies which is available to those interested on its website. This taxonomy is interesting for researchers because it shows the possibilities offered in the different audit areas. Perhaps different scholars would have produced other classifications equally as useful but due to the interest this taxonomy has for audit research, it will be described and commented in this editorial Note.

The Note will be concluded by commenting on how the techniques and operating methods used in the audit world have been copied by other professional service companies. Many of them have been exported from North America to the rest of the developed and developing countries. The way of doing things in financial auditing has become a study subject for other managerial and social disciplines.

The approaches mentioned are not meant to be a classification of methodologies nor do they pretend to describe all the possible solutions to the problems explained in the introduction. They are representative of the present contemplations in this research area. These approaches are compiled and offered here as suggestions so that each individual researcher can consider them to find their own pathway.

The positive approachThe authors who use the positive approach, which are the majority of the articles consulted to elaborate this paper, undertake the detection of constants by examining data based on audit performance. This allows them to obtain conclusions about the behaviour and the reactions that can be expected from this professional activity in different settings. This methodology exploits the formulation of hypotheses, which are then tested for verification by using more or less sophisticated statistical models. The possible statistical significance found from the connections provides grounds for accepting or rejecting the hypotheses. Authors then proceed to construct a theory about the cause–effect of the statistical associations found.

The positive approach does not require, in certain cases, closed familiarity with complex economic, sociological or psychological theories but focuses on data handling provided that previous research justifies the analysis of the new posed research problem. Many young academics prefer this way because they can start their research and have papers published and cited if they adhere to this approach and send the production to proper journals. The reason is because the products that are elaborated are standardized and by including only small additions to the models or data used in previous studies they can add to the literature.

In the following paragraphs, the suggested topics offered by the EAR call for papers will be discussed. These issues, which are the object of interest by the scientific community of this journal and which have been chosen as representative by the editors of the special issue.

The first subject of interest is the interaction between auditors and the audited entities. This encompasses the framework of the audit activity, how the auditors’ activity is perceived and how it is used with the objective of serving the professionals to plan their work effectively. The area also includes how the requirement of independence is understood and by what means it can be met effectively.

In some audited organizations, the most important accounting and financial expert is the auditor himself. This allows him to impose his opinions and offer complementary services. In other entities, the auditor is an intruder that destabilizes existing power relations. This, very often, produces rejection or adherence to his figure and to his work.

The arrival and development of Audit Committees within the audited organizations has changed ostensibly the interaction that the auditor has with the organizational mechanisms of the entity. This area is very much unexplored to date due to the changes which have taken place. It is an interesting research area which can provide knowledge about the characteristics and consequences of the changes brought about by the Audit Committee.

The editors of the EAR special issue say that little is known about auditor-audited relationships, however the classification made by Lesage and Wechtler (2012) from 25 scientific journals, concludes that 52 percent of the articles reviewed are dedicated to studying parts of these relationships.

A second subject of interest are the regulatory pressures on audit professionals, which have been developed in all countries since the Enron scandal. The subsequent Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 gave birth to independent regulators in the audit profession which was previously self-regulating, a fact that the profession was particularly proud of. Although we know a lot about the effects that this regulation caused on listed companies, we know little about how this change has affected the internal organization of audit firms.

These new demands required changes in the management and working conditions of audit firms to confront the new demands in quality control, inspections and investigations. We know relatively little about how these controls work in practice, and how they have influenced the management culture and style of audit firms. Research carried out by DeFond and Francis (2005) foresee important difficulties for firms in this area and which will require further study.

A third subject is the promotion and use of big data in business analytics by auditors. Previous literature reveals little use of big data techniques in auditing to date while they are broadly extended in other disciplines such as engineering, health or marketing. Big data analytics is the name given to the process of inspecting, cleaning, transforming, and modelling a large collection of data (Big Data). Once the big data has been transformed into useful information and is used to discover and communicate facts and patterns, to suggest conclusions, the objective is to support decision-making decision-making (Cao, Chychyla & Stewart, 2015). Special types of statistical or logical software have been developed to manage these large volumes of data. Therefore, this field is now ready for experimentation, simulation and heuristics.

In auditing, big data analysis is a valuable tool when it is combined with audit techniques and expert judgement to obtain better evidence about transactions and measurements. Gepp, Kinnenluecke, O’Neill and Smith (2018) found from published papers that the most relevant uses of big data analysis have been in financial distress modelling, fraud modelling and stock market predictions some of which were related to auditing. But the door is open to other developments relating to the needs covered in the past by audit sampling. In an interesting volume that the journal Accounting Horizons devoted entirely to data analytics. Krahel and Tiera (2015) conclude that enlarging the size of the sample is costless in the case of some algorithms and there is even a possibility to test with the entire population in several circumstances.

Although it cannot be mentioned within the analytical techniques section, one of the points of maximum interest for the development of the audit is the technology related to the continuous audit and which can be developed in parallel with the continuous accounting process. This consists of a set of techniques for checking simultaneously with the elaboration of the accounting information and allows evidence to be obtained and decisions to be taken from the moment the data appears. It can even anticipate the undesired consequences in the evolution of any process or system (Kogan, Sudit & Vasarhelyi, 2018).

A fourth subject, which requires further analysis, is the expansion of services offered by audit firms. Despite the various prohibitions enforced for providing services other than auditing to clients, firms are constantly seeking to expand their business area through consulting services (tax, systems, human resources, mergers and acquisitions, etc.). Any corporation wishing to extend its activity to other countries seeks advice from his auditors, especially if they have a presence in the countries of destination and this has not changed despite the recommendations relating to the separation of audit and consulting activities. The auditor offers a network of contacts, in the country to which the employer is directed, which facilitates the entry and establishment of the business. In this sense, auditors are valuable instruments in the globalization of firms and in the development of the worldwide capitalist model.

The price of an audit is determined simultaneously with that of the related services that are provided, which was demonstrated by Whisenant, Sankaraguruswamy and Raghunandan (2003). After the introduction of the new excluding regulations for small and large firms little is known on how the firms have reacted in order to adapt to these rigorous market circumstances. However, we do know that the business figures are continuously increasing and that this growth is more evident in the non-audit services offered.

A fifth subject, which has not been the target of intense research in this area, are the efforts by the profession to create and retain talent. This subject area includes the generation by the profession of a more diverse and inclusive work environment by integrating minorities such as the disabled, new immigrants, the LGBT community and, of course, women. This latter minority has however been studied much more in the past, and its positive effects on the quality of audit work are known (Ittonen, Vähämaa & Vähämaa, 2013).

However, there are many possibilities for researching on issues relating to the staff that are hired by audit firms. For example, there is a lack of profound studies on the characteristics that determine promotion within the firms. There is also little known about the reasons for employee abandonment in a sector that has one of the highest rates of personnel turnover in the economy (in this line we can examine, for example, the celebrated article of Sheridan, 1992, on the organizational culture and the permanence of employees in the sector). On the other hand, employees who leave the firms are very often transferred to client companies which is a way of ensuring the permanence of the audit contract and other services offered by their previous employer. It seems clear, however, that firms chisel the character and personality of their employees, until they are identified with that particular organization (Covaleski, Dirsmith, Heian & Samuel, 1998).

The working environment and dedication by audit employees has itself been the subject of some studies. It appears that there is a special way of understanding the desirable behaviour of an employee within the auditing firms. This is characterized by sacrifice, the dedication of more hours than those initially planned and the acceptance of certain pressure by clients (Espinosa-Pike and Barrainkua, 2016). These characteristics could collide with ethical standards and with the tendency for a correct work-life balance.

A growing branch of literature is arising on human relations in organizations and the model of personnel management in audit firms is becoming the object of study due to its peculiarities. Thus, the studies by Spence and Carter (2014) can be mentioned, which even investigate the tastes and cultural customs of public and private auditors, which certainly differ greatly (see Spence, Carter, Husillos & Archel, 2017).

Finally, the sixth subject of the call for papers by EAR mentions the topic of small audit firms, which are now subject to special consideration in the rules and also by regulators and standard setters. The organization, operation of small business networks, recruitment and training, quality of work and reporting, response to competition pressures, the composition of their income, the way in which internal controls are designed and other behavioural issues are very interesting research fields. In these areas mentioned, it is important not to concentrate research on the differences with medium firms or with the Big N, but also to ensure their survival in the future, preventing an already oligopolistic market from becoming a monopoly.

The institutional approachThe institutional approach derives from well-established scientific traditions in economics and business administration. It is easy to understand however that it has not been the prevailing tendency in the growing volume of auditing research. Such is the case that Humprey (2008:192) called this tendency “alternative auditing research”, recognizing the lack of economic or institutional incentives, and the lack of interest by audit firms and auditing bodies to carry it out or to take advantage of its results.

However, it is a genuine intellectual effort, based both on facts (but not determined by them) and on economic, social and political theories that look at auditory activity from the perspective of the impartial observer, trying to draw long term conclusions to conceptualize the audit phenomenon. As a by-product, some findings in this approach would be useful in inspiring public policies.

In particular, Humphrey's paper criticizes the prevalence of the quantitative approach in most auditing research: many scholars are reluctant to look qualitatively and critically at the exercise of the activity. This can determine a particular way of thinking in the process of educating and training of audit professionals which now pivots on the knowledge of standards and increasingly sophisticated techniques instead of forming them in an accurate awareness of their delicate role in this current complex society.

The first topic highlighted by the publishers of the CPA special issue is the consequences of the emergence of “commercialism” in audit firms. This leads not only to the provision of other services, but has contributed to the marginalization of the audit as a service because it is less profitable than other consulting services offered by firms. Auditing is only the gateway to companies, which means that less attention is paid to it as it represents a lower percentage of customer-invoiced services. The audit partner therefore becomes the sales agent for other related services, which allows the firm to gain the loyalty of the audited company at the same time as it loses independence to make impartial judgments in the audit report to be issued.

On these lines, there are interesting research studies on the tendency of mergers between firms (small or large), as is done in industry, banking or trade, to deal better with the problems posed by a competitive market. In the case of Spain, it is also important to study the problem of audit prices, which are significantly lower than in other countries, and explain the evolution of these prices in accordance with the expectations of income for other services that can be offered during the audit tenure.

It is also interesting to see the role that managers of audited companies have in the extension of the business of firms. These managers are often recruited from the employees of the auditing firms. In short, these executives have been trained in the firms they admire and to which they reach out to when they need services that can help them in their task as managers.

The second suggested topic for contributions to the CPA special issue is the study of the effects of changes in regulation, which try to tackle situations and actions that are perceived as erroneous. According to the editors, the idea is to change the focus and question both how and with what consequences regulation is adopted, such as what is offered as new regulation in both content and form. This approach would emphasize the ultimate purpose of the regulatory explosion that is being experienced in almost all countries.

The third topic is the attempt to legitimize an audit firm's participation in the consultancy arena of audited companies by making a claim on the auditor's knowledge base as a justification for his work in both audit and non-audit areas, even when these services are rendered simultaneously. An auditor has a strong skills base and inside company knowledge that can make the auditor almost essential in the solution of company conflicts. Companies confide in auditors because managers consider them as confident professionals. There is no doubt that the auditing profession has gained this attribute over the years, but the question is whether or not this confidence characteristic could be a trade off with their obligation to be independent.

It is common belief among auditors that the consultancy services provided to audited companies help them to understand the company better. They also claim that it does not interfere in their independence requisite because what they offer is expertise and knowledge to solve problems. However, experimental empirical research suggests that users value more the information provided by the independent auditor than by others (Guiral, Ruiz Barbadillo & Choi, 2014).

The idea that knowledge is a factor which permits a relaxation of the demands of independence is not alien in academic research. It is crucial to interpret the attitude of auditors working for Big N and medium sized firms and it is therefore an attractive and desirable research area for the future. In an experiment, which is worthy of mention, Jamal and S. Sunder (2011) found that in certifying the authenticity in the American market of buying–selling cards with the image of baseball players (baseball cards), the collectors preferred the opinions of the selling intermediaries should read (cross-sellers) compared to those issued by independent certifiers, possibly due to their expertise and knowledge of the market. In fact, the background to this conception is that market discipline can replace independence: that is, if the market discipline is functioning correctly, then perhaps there is no need for auditor rotation, nor for co-audits, nor for the prohibition of offering non-audit services while performing the audit engagement.

However, this kind of reasoning that blindly trusts the market to solve social conflicts forgets that perfect markets are an ideal but not a reality. Markets are not above the people operating in them. Their functioning depends on the acceptance and respect of rules that are continually being challenged by the experts who are tempted to take advantage of the loopholes in the market. Surprisingly, this line of research, which promotes the trust in the market, must be noted here because it has loyal followers. The work of Arruñada (1999, 2000), is an example of the scepticism of the effectiveness of the rules that prevent lack of independence and proposes that it should be the market itself that discriminates, on demand, the good from the bad auditors. Researchers who follow this market religion—as if it were a deus ex machine—consider the market to be capable of resolving all the problems in which humans find themselves.

The fourth topic suggested in CPA's call for papers is the public interest of the auditing activity. Although in certain countries, as is the case of Spain, the importance that the public interest has in the audit has not reached as yet the forefront of the debate. This discussion is essential to support the intervention of the supervisory authority and the extension and conservation of the mandatory audit for companies and other entities. In this way the social relevance of the audit can be justified, by analysing the benefits it contributes to the economy in terms of security, financial stability, comfort, aiding development in less favoured countries, etc.

The most critical researchers doubt that the system of private audit firms can serve the public interest in a conscious and committed manner, even when they are supervised and regulated. They maintain that there are circumstances which prevent it, such as the fact that they are elected or that they are paid by the companies they audit, and that they can offer other services either by themselves or through other entities to which they are linked or associated. Researchers have the job of proposing and testing different models relating to the appointment and compensation of auditors that could defend the compatibility of their work and their relevance to the well-being of society.

The previous contemplations are linked to the fifth topic raised by CPA for its special edition dedicated to audit. This subject challenges the shifting identity of the auditor in society. After the scandals that audit firms and auditors have been involved in or associated with have clearly affected their reputation. It is not a question of querying their competence (which is out of doubt), but of clarifying the role that they want to have in society. A society that will judge them according to how they fulfil the mission expected from them. In short, it is a matter of foreseeing the future of audit professionals. This is a very attractive research topic, because the tensions presently being suffered by auditors who are continually questioned about their work as if they were exercising their mission in a fraudulent way, cannot and should not be maintained for much longer. The auditor's professional profile in public practice must evolve and it must recover its increasingly diluted prestige brought about by the expectation gap. This would also favour the recovery of the prestige lost recently by accounting and auditing careers in the most developed countries.

Previous research that has affected the identity of the auditor, for example Gendron and Spira (2010), concluded that the Big N auditors are very unaware of their fragile position as professionals in society, and thus do not understand the causes of Andersen's failure. On the other hand, O’Dwyer (2011) argues that by conquering the market through the issuance of environmental insurance reports, can be an escape route which may serve to modify positively its image and identity.

However, the base problem and its rectification is not resolved by the lack of awareness by the profession of its own situation. In fact, the audit profession will have no motivation to seek a new identity that reinforces the trust that society has in it because the profession won’t have any incentive to change it. A similar situation was seen in the case of Enron executives who were advised for many years to incorporate a change before the collapse occurred, but while the markets continued to favour the company they had no incentive to do so. Research may therefore have to be directed at predicting the end of professional activity by discrediting those who practise it.

The sixth and final topic raised by the CPA editors is the control and supervision of accounting firms. This subject has gained importance since the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) constituted the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) to protect investors by inspecting listed companies, auditors in North America's listed companies and broker-dealers. The failure of professional controls has triggered the implementation of quality control standards for firms, such as inspections on the procedures followed and investigations to impose sanctions.

On the same lines, a research area that is still relatively unexplored is the study of the reorganization of audit firms after the issuance of standards such as the International Standard on Quality Control No. 1 (ISQC 1) by the IFAC (2009). The analysis can be directed at both Big N and small and medium sized firms that have less resources and experience in quality control.

On the other hand, there are no comprehensive studies on the effect that the inspections are having on the firms that are reviewed by supervisors, in the countries where these controls were put into practice. This is due to their relatively recent incorporation and therefore we don’t have studies on the reactions (favourable or unfavourable) that these sanctions are having among audit firms either. It is worth mentioning the study by Fuentes, Illueca and Pucheta-Martínez (2015), in which they check the effect that the sanctions imposed from the beginning of the 1990s by the Spanish Institute of Accounting and Auditing (ICAC) have caused among auditors and audit firms that received fines. This study revealed a positive reaction showing conservative behaviours by the auditors in the years following the sanctions. This leads the authors to suggest an improvement in the quality of their performances.

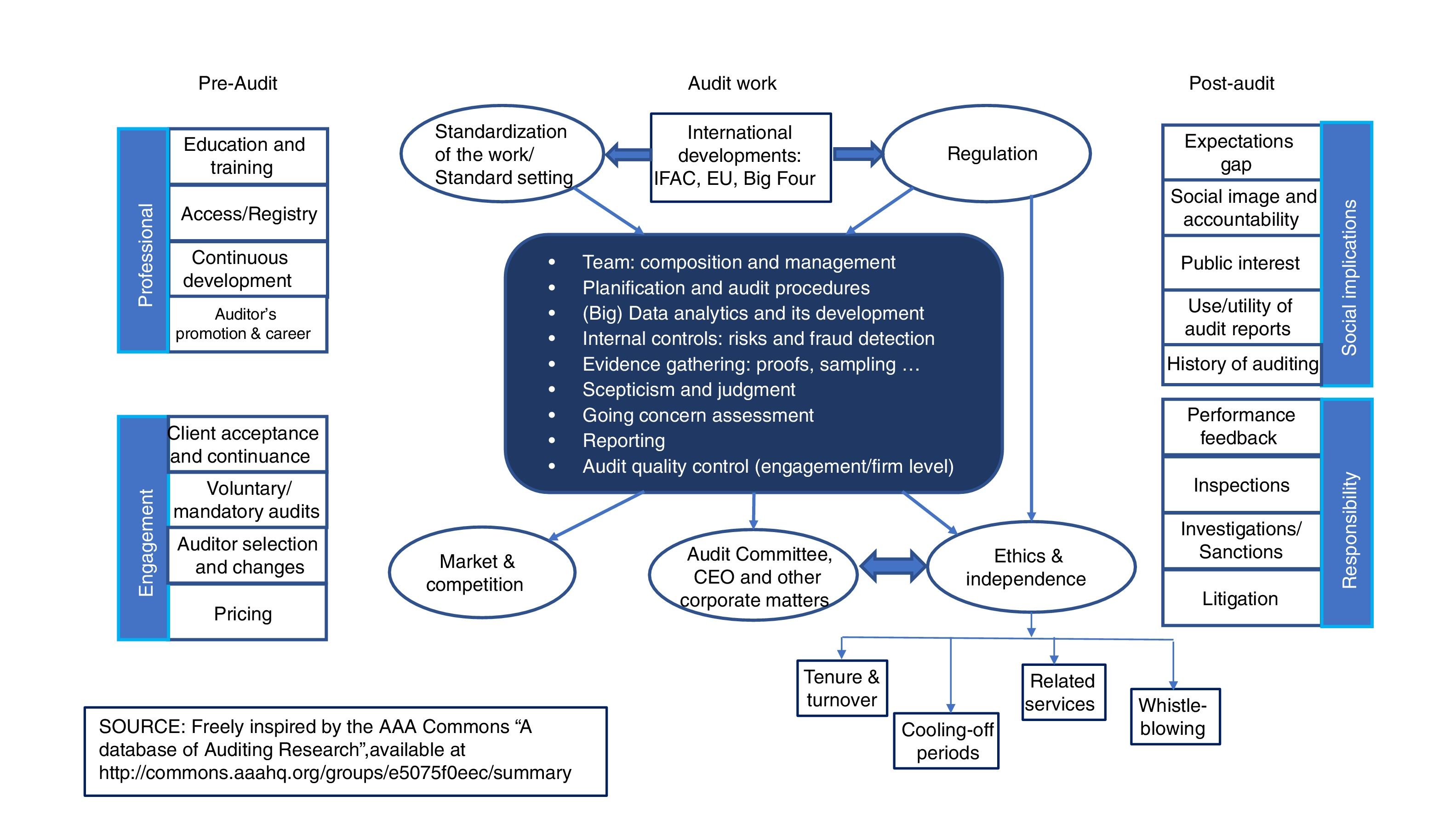

The taxonomy approachIt is possible that a good part of the readers of this editorial Note are interested in knowing the fields where research has taken place and possible research areas for the future in the subject of auditing accounts. With this objective in mind, Graph 1 has been constructed from a free inspiration of a previous graph prepared by the American Accounting Association (AAA).4

In the graph, three different fields are observed, titled Pre-audit, Audit work and Post-audit. The Pre-audit section contains issues, such as professional qualification and auditing, the pricing process and conditions of the assignment and all other issues that occur before the audit is carried out. In the Audit work section, the core is formed by the research fields which relate to the job itself. It also includes questions relating to the regulation of the activity and standardization, as well as interactions with the market and the audited company. In this field, the issues relating to independence have been included, although it affects all of the fields equally. The Post-audit section incorporates matters relating to the problems posed by the results of the audits, both in terms of their implications and the exercise of the responsibility assumed by the professional auditor.

The interesting thing about the classification is that the AAA website is conceived as a taxonomy of research work itself, so that for each of the areas analyzed (there are 15 in the first group, subdivided subsequently reaching 130 areas). The article titles can be consulted and they offer a description of the problem being dealt with, an explanation of the method used and the results achieved. Although it does not replace reading the originals, it shows what has been done previously and how the research was approached which can be very helpful to any interested party.

In early January 2018, the database contained 764 summaries of articles on auditing, from journals edited by the AAA and some other prestigious journals in the USA. These papers have been classified into the following areas: standard setting; client acceptance and continuance; auditor selection and auditor changes; Independence and ethics; audit team composition; risk and risk management (including fraud risk); internal control; auditing procedures: nature, timing and extent; engagement management; audit quality and quality control; auditors’ reports and reporting; governance; corporate matters and international matters. As the database also supports Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter accounts, users can integrate the updates into their existing social media feeds.

Some of the principal sections of Graph 1 have already been analyzed in this Note, mainly within the positive approach. From the other areas, it would be useful to deal with some of them in order to clarify research opportunities. Below, and in order to complete the description of research possibilities, we will refer to the issue of professional ethics and the expectation gap in relation to the inclusion of going concern qualifications in the audit report.

EthicsAs far as ethics is concerned, sometimes it is erroneously assumed that ethics implies compliance with behavioural standards in the education of auditors and the practice of auditing. It should be borne in mind that this deduction is very dangerous, because neither the standards capture all the ethical values required by the professional, nor the mere study of compliance with standards can lead to ethical conclusions in auditing.

On the other hand, ethics is a common research question across the different approaches. The interrelation of technology with ethical considerations over professionalism and judgement in accounting is a general concern that has been highlighted in a call for papers in the Journal of Business Ethics,5 with the proposal to reaffirm business ethics as a field think systematically about the full influence of technology on all aspects of accounting.

It is common to confuse independence with ethics in audit practice, even when independence is only a part of ethical behaviour and there are other components that must be respected, such as integrity, objectivity, professional competence and continued professional development, professionalism or confidentiality (see IFAC, 2005).

West (2017) makes an interesting observation, from the Aristotelian perspective, in a research study that tries to serve as a counterpoint to the approach focused on by IFAC standards. The study tries to demonstrate that ethical behaviour should serve the common good (a way of speaking about the public interest) as well as requiring compliance with the actions of competence and diligence. In this way, compliance with ethical principles should be projected to the consideration of whether the auditor's behaviour is appropriate to achieve that common good of the profession and society as a whole.

The field of ethical behaviour can present obvious difficulties for making observations in research studies (Jones, Massey & Thorne, 2003:91), for example in the case where survey data should be obtained, this may contain response biases, or where laboratory experiments are performed and real conditions are not always simulated.

For example, there is a growing interest in discovering the pattern of whistle blowing against auditors, both inside and outside the firms and this is a relevant and appealing research area to be explored. The ethical duty of integrity is a commitment to report incorrect behaviour either within the firm itself or before the external supervisor. This pointing the finger attitude is better accepted in some cultures than in others (Patel, 2003), which gives place to the study of professionals behaviour in non-ethical situations country by country and culture by culture. The results can help regulators to design suitable mechanisms for improving ethical behaviour in the professional activity (Latan, Ringle & Jabbour, 2016). The survey methodology is at the forefront of this field of study, taking into account the methodological biases that have been pointed out earlier.

Another relevant ethical problem, related to independence, is that of rotation. The scientific evidence available is highly controversial. As an example, we will mention two papers published in this journal that show contradictory conclusions. Firstly, the research work of Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gómez-Aguilar and Biedma (2005), with objective data on the number of qualification paragraphs in audit reports, obtained the unexpected result that the longer a company was audited by the same firm the more likely it was that the audit report would be qualified. This defended that rotation does not necessarily improve the quality of the audit. A few years later however, the work of García Blandón and Argilés (2013), using more sophisticated statistical techniques but with the same data, found no evidence of a greater number of qualification paragraphs with longer contract duration.

It is possible that auditors, and the bodies where they are associated, defend empirical studies whose results question the measures used to increase independence in order to improve the quality of the audit. However, researchers should work on models of behaviour, based on solid scientific theories, and not merely on data series from which cause–effect relationships are induced, thus discarding the mere counterintuitive statistical associations. It is quite possible that, in the coming years, with more generalized data on auditors’ rotation, the consensus now lost can be improved.

Expectation gapThe other issue that must be addressed due to its relevance in the past and its continued concern for researchers is the expectation gap in auditing. This matter is not a worry among the professionals themselves because they are protected by the laws that correspond to the practice of compulsory audits. The expectation gap arises because the users of the audit report expect to obtain more from this document then what the report really offers. The two areas where the gap is more profound have to do with the discovery of fraud and the continuity of these audited companies.

An essential research aspect of the expectation gap area is presently to discover if the new design of audit report introduced through the International audit Standard 700 (IFAC, 2015) helps to cover this gap over time. Another possibility is that professionals transform this new format back into a series of standardized useless phrases (boilerplate clauses) which occurred with the preceding models. In particular, it is interesting to know if the identification of the risks of the audited entity through the key auditing matters (KAM) and the new position and drafting of the qualifications and uncertainty opinions succeed in transmitting more useful information to users to cover their needs.

For the moment, there seems to be positive feedback from tests performed on the users’ attention to the KAM. This is due to their placement at the beginning of the report, following the opinion of the auditor and the grounds on which it is based (Sirois, Bédard & Bera, 2017). However, more evidence is required on the influence they may have on user decisions, and even on the auditors reaction to merely discharging their responsibility according to Kachelmeier, Schmidt and Valentine (2017).

The design of the new report does not, as usual, come from researchers’ proposals but from the ideas of the regulatory bodies and which have not been the subject of verification or testing. It would be interesting for researchers to make future proposals for change and not to limit themselves to validating the decisions made by the audit regulators. These proposals can be made by using the usual survey or experimentation techniques.

The second area of research which is related to the expectations gap, is the going concern qualification. Research, so far, has shown without a doubt that formal (mathematical) decision making models predict much better than auditors whether the going concern principle of the audited company is affected. This does not seem to be such a surprising observation because models do not fear the loss of a client nor are they concerned about the paradox of the self-fulfilment prophecy. This prophecy commands those who sign the qualified audit report and much more insofar as they think of the influence or effect their opinion may have (Guiral, Ruiz & Rodgers, 2011).

In the work of Ruiz-Barbadillo, Gómez-Aguilar, de Fuentes-Barberá and García-Benau (2004), they found that the bigger the size of the corporation audited the more complicated it resulted in issuing a going-concern qualification and conversely the greater the size of the audit firm the easier it is to issue a going concern qualification due to the reputational consideration of the audit firm.

Carson et al. (2013) identify three areas of interest for academic work in this field: The determinants of a qualified opinion, accuracy of predictions and consequences of the reports issued. A fairly disheartening result, for those who support the value of the audit report, is that of Guiral-Contreras, Gonzalo-Angulo and Rodgers (2007), where it is suggested that the qualified opinion on going concern is taken into account, by credit analysts, only if it contradicts previous expectations.

Conclusions: the “audit society” and its implicationsIt can be said that if the audit is the subject of detailed research, it is not only because it is a professional activity related to the verification of financial statements. If this were the case, it would not have been worth considering researchers’ concerns in such detail. On the contrary, if audit research is important it is because it has created, and is perfecting, a way of understanding economic relations and, therefore, the social relations which underlie the economic ones. This has been disseminated in many other professional activities relating to behavioural control or the results of those human and social behaviours.

We are in an “audit society”, using the title of the book by Power (1997) in which it relates the audit with the need to check the proper functioning of products and processes that matter, to be able to trust them. In the last decades of the twentieth century there was an explosion of checks (in industry, in health, in the public sector, in education, in defence, in international relations, etc.) in which the basic elements of the financial audit were repeated: A problem of agency, or trust between principal and agent, an independent third party who obtains evidence on how the agent meets the desires of the principal, a process of obtaining evidence, and a judgement or mere assertion founded on the evidence obtained and generally contained in an ad hoc report.

Although the fundamental difference between the financial audit and any other compliance audit is that, the reports issued by the financial auditors are prepared after including a professional judgement by the auditor whereas this pronouncement of a general judgement is not required in other types of audits. However, the methodology used in all audits has a lot in common and all use checking mechanisms and processes for highlighting errors and nonconformities in the system.

There is always a standard to be fulfilled (which could also be a contract, a treaty or something similar that imposes a certain behaviour), a set of verification techniques, a body of experts to which the verification is commissioned and a final report. This report usually includes the results of the verification and even includes recommendations for improvement. There has also been a control of the verification process itself which permits continuous confidence in the experts and their procedures. This verification is euphemistically called “quality control”, perhaps with the objective of not inciting rejection because those who have carried them out do not easily accept any review of tasks.

On the behavioural standards side, traditional accounting standards have given way to others that standardize other procedures. These could be from the International Standard Organization (ISO), or a standard from the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), a medical protocol for transplantation or a nuclear non-proliferation Treaty. In any case, they all represent the way to fulfil a responsibility assumed in the usual or agreed manner.

On the other hand, the verification rules already serve to guide the auditor and to pass messages to the principal about whether or not the person carrying out the procedures can be trusted. These rules give some certainty to both parties that the checks have been carried out diligently, but that they also serve to discharge the responsibility if there are errors in the evaluation or in the judgement expressed by the expert auditors. Using the words by J. Power (2003), audit produces legitimation.

In this respect, the characteristics of the financial audit were repeated everywhere, in a multitude of economic and social relations because it was best to resort to a well-known model in order to carry out so many checks. The audit firms themselves began to transform into multiple-verification firms, while offering services to amend the defective procedures at the same time, so that they would meet the relevant standards next time (to meet the desires of the principal).

For this reason, the model of audit firms and their way of acting has been traced quite faithfully in other environments and the internal audit departments in companies and other organizations have now proliferated; Public sector auditors have copied the procedures that have been used for decades by the auditors of business enterprises; A sophisticated process of information elaboration and verification of the objectives has now been set in educational and sanitary management. This gives data to the public authorities and carries out a similar process in some ways to a financial audit. In short, familiar terms from the financial audit environment are now common place terms in dozens of situations in public and private organizations. These terms include language such as, audit planning, evidence, sampling, internal control, reports, qualifications, observations or report monitoring.

This editorial Note has reviewed research in audit which stimulates increasing interest among professionals and academics. This is evidenced by the growing number of articles and papers published annually (see Fig. 1 of Lesage and Wechtler, 2012).

Part of the research is aimed at analysing what the auditor does and how he does it, that is, how the auditor is academically prepared, how to access the profession, how to obtain a client contract, what price to charge for services, how he manages his independence obligation, how they obtain evidence at work, how the auditor transforms that evidence into the audit report and how he controls the quality of the work and fulfils its contractual goal. Generally, this research uses positive methods and can serve the auditor, to direct or correct their actions, and is useful to regulators and supervisors to design appropriate policies. Accounting, individual and social psychology, information technology and theories of communication and individual decision-making can be auxiliary disciplines in this type of research. In some cases this type of concern has been compared with medical research (Hay, 2017), although its purpose and scope is not exempt from criticism (see, for example, Gendron & Bédard, 2001).

Other research endeavours are designed to study, at a higher level, the importance of auditing within the social organization to which it serves. It questions and studies the social function of the audit from a historical point of view. It examines the relationships that this professional activity has with social and political institutions, which also implies considering the audit market and the professional social prototypes being created. Of course, in this approach the future of this activity is reasoned and the relevance of continuing to rely on it as a way of preventing and solving social conflicts is taken into account. Sociology, law and legal theory, political science, economic theory and other social behavioural sciences are the auxiliary disciplines of those who work in this field. This research is probably not useful for conducting audits, and therefore is less practiced and has access to fewer resources, but can be used to question what the ultimate purpose of this activity is.

Ratzinger-Sakel and Gray (2015), plan a methodology to connect or bring together research, education and practice by following the recommendations of the Pathways Commission (2012). However, this possibility is more open to the positive approach than the institutional one.

All researchers, despite the approach they use, consider that an auditor enjoys a social privilege by being exclusively in charge of the verification of the financial statements. The auditor must win and deserve the confidence that has been deposited in him, not only by performing diligently, but by taking care of the sometimes neglected image which reflects their service to society (the public interest or the common good). J. A. Gonzalo-Angulo (1995) made this reflection more than two decades ago: the situation does not seem to have improved since then.

FundingThe authors acknowledge financial contributions from the Spanish Ministry of Innovation and Science (research projects DER2009-09539, ECO2010-17463, ECO2010-21627, DER2012-33367, ECO2015-66240-P, DER2015-67918P), Castilla-La Mancha Regional Ministry of Education and Science (research project POII10-0134-5011), and Alcalá University, Madrid (research projects CCG2014/HUM-036 and CCG2016/HUM-056).

The authors would like to thank Bernabé Escobar Peréz, the Editor-in-Chief of the Revista de Contabilidad – Spanish Accounting Review for confiding in us to participate in this journal issue. We would also like to thank the useful comments by Fabrizio Di Meo (Universidad de Acalá) and Adriana Leuro Carvajal (Universidad EAN-Bogotá), and the generous and useful review made by two anonymous referees. As usual, the authors assume full responsibility for the views included in the text.

Some of the reviewers noted the high degree of criticism in the text when examining commercialism. The authors want to highlight that the criticism refers to the profession in general and some (not all) of the social organizations created to operate this service activity. It in one way refers to any individual auditor or audit firm.

http://explore.tandfonline.com/cfp/bes/rear-si-auditing (accessed on the 1 of April 2018).

https://www.journals.elsevier.com/critical-perspectives-on-accounting/call-for-papers/special-issue-critical-auditing-studies-adopting-a-critical (accessed on the 1 April 2018).

See http://commons.aaahq.org/groups/e5075f0eec/summary (last accessed on 5 April 2018).

See the thematic symposium call for papers in the following address: [http://static.springer.com/sgw/documents/1623350/application/pdf/The+Impact+of+Technology+on+Ethics+Professionalism+and+Judgement+in+Accounting.+Sally+Gunz+Linda+Thorne.pdf] (accessed on the 10 May 2018).