Although most of the patients affected by COVID-19 recover their health and return to their previous situation, some of them present symptoms that can last a long time after the acute illness. The main objective of this study is to assess the correlation between symptoms of long COVID and symptoms of central sensitization. Secondarily, it will try to describe the symptoms of long COVID and its correlation with alexithymia and depression.

MethodsProspective observational study in real clinical conditions. Include consecutively those patients who present long COVID and complete multidisciplinary evaluation by a somatic specialist and a psychiatrist, together with a battery of questionnaires.

ResultsThe profile we found corresponds to a woman, in the middle of her fifth decade of life, with higher education and working, who passed the SARS-CoV-2 infection 1 year earlier, without requiring hospitalization and with a severe depressive disorder and alexithymia. We found an intermediate correlation (rho .665; p < .01) between central sensitization questionnaire and the sum of symptoms of long COVID, as well as between the sum of symptoms presented and depression (rho .467; p < .01) and not between the sum of symptoms and alexithymia (rho .151; p = .359).

ConclusionsSensitization phenomena seem to be of notable importance in the symptoms of long COVID and present a symptomatic constellation characterized by fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and memory problems. Patients with persistent COVID present more severe depressive symptoms than they are capable of perceiving o express.

Aunque muchos de los pacientes afectados de COVID-19 recuperan su salud y vuelven a su situación previa, algunos de ellos presentan síntomas que pueden durar mucho tiempo tras la fase aguda de la enfermedad. El objetivo principal de este estudio es evaluar la correlación entre los síntomas de la COVID persistente y los síntomas de la sensibilización central. De manera secundaria, tratará de describir los síntomas de la COVID persistente y su correlación con alexitimia y depresión.

MétodosEstudio observacional prospectivo en condiciones clínicas reales. Incluye consecutivamente a aquellos pacientes que presentan COVID persistente y una evaluación multidisciplinar completa por parte de un especialista somático y un psiquiatra, junto con una batería de cuestionarios.

ResultadosEl perfil que encontramos corresponde a una mujer, a mediados de la cincuentena, con educación superior y trabajadora, que pasó la infección por SARS-CoV-2 un año antes, sin requerir hospitalización y con trastorno depresivo grave y alexitimia. Encontramos una correlación intermedia (rho 0,665; p < 0,01) entre el cuestionario de sensibilización central y la suma de síntomas de COVID persistente, así como entre la suma de los síntomas presentados y depresión (rho 0,467; p < 0,01), y no entre la suma de síntomas y alexitimia (rho 0,151; p = 0,359).

ConclusionesLos fenómenos de sensibilización parecen tener una importancia notable en los síntomas de COVID persistente, y presentan una constelación sintomática caracterizada por fatiga, dificultad para la concentración y problemas de memoria. Los pacientes con COVID persistente presentan más síntomas depresivos graves de los que son capaces de percibir o expresar.

Research is being conducted worldwide to learn more about the short- and long-term effects of COVID-19. We are progressively learning that it affects many organs besides the lungs and that there are many ways in which the infection can affect a person's health. Although most COVID-19 patients recover and regain their complete health or return to their pre-existing condition, some patients may have symptoms that can last for weeks or even months after recovering from the acute illness. Even people who are not hospitalized and have a mild illness can have persistent or late symptoms.

According to the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the most frequent symptoms of persistent COVID are shown in Table 11.

Most frequent symptoms of persistent COVID according to the CDC.

| Fatigue | Altered taste |

| Difficulty breathing | Altered smell |

| Cough | Memory problems |

| Joint pain | Anxiety |

| Chest pain | Irritability |

| Difficulty concentrating | Hair loss |

| Depression | Dermatological alterations |

| Muscle pain | Tachycardia |

| Headache | Sleep problems |

| Intermittent fever |

There is still no clear consensus on the origin of long COVID symptoms. One avenue to explore would be that its development shares mechanisms with so-called central sensitization syndromes. Central sensitization is an increase in the responsiveness of nociceptive neurons in the central nervous system to normal or subthreshold stimuli.2 Multiple infectious agents have been related to the development of chronic pain or fatigue, with the hypothesized causative mechanisms being the alteration of the immune system, the persistence of viral remains, or the treatment itself used to deal with infections.3

Another possible origin that has been hypothesized in relation to the existence of medical unexplained syndromes is alexithymia. The concept of alexithymia was introduced by Sifneos in 1973.4 Alexithymia leads to an inability to recognize and identify feelings, the use of language to describe feelings, and the inability to distinguish between emotions and bodily symptoms. It is treated as a stable personality trait, which along with other personality and environmental factors predisposes to the worsening of somatic diseases and may contribute to the onset of mental disorders. The direction of this dependence is not known exactly due to the heterogeneity of the etiology of alexithymia.5

Alexithymia and sensitization are by no means incompatible theories. It has been observed that patients with alexithymia have a higher perception of somatomorphic pain, as well as depressive feelings.6

The main objective of this study is to evaluate the correlation between long COVID symptoms and central sensitization symptoms. As secondary objectives, we want to describe the symptomatology of long COVID, evaluate the correlation between alexithymia scores and long COVID symptoms and evaluate the correlation between depression and long COVID symptoms.

MethodsProspective observational study in real clinical conditions. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in the Health Areas of León and El Bierzo on February 23, 2021 (registration number 2139).

All consecutive patients presenting with long COVID symptoms, who sign informed consent and complete the evaluation, are included. Patients are assessed in a multidisciplinary approach, initially by a somatic specialist in Internal Medicine, Pneumology, or Rheumatology who establishes the absence of somatic explicability of the symptoms and rules out the presence of evident somatic sequelae after the infection that could explain the clinical, such as pulmonary fibrosis. The evaluation by the somatic specialist includes one or more consultations in which a clinical interview and a physical examination are performed, as well as any analysis or imaging test that is considered appropriate. The specialist provides the patient with the corresponding self-administered questionnaires that must be completed prior to the outpatient consultation in the Liaison Psychiatry Unit. The psychiatrist assesses the patient for 45 min, knowing the information from the self-administered questionnaires, and establishes the diagnosis, ruling out that the pathology has another psychopathological origin, and an empirical treatment plan, in the absence of specific treatments for this condition at the present time.

The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of long COVID (patients with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, starting from 3 months after onset, with symptoms lasting at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis7 and collection of informed consent. Patients with less than 90 days between the date of PCR negativization and the date of questionnaire administration, inability to complete the questionnaires or suspicion of symptom malingering were excluded.

Patients complete a battery of self-administered questionnaires, including the following data:

- -

Diseases and allergies.

- -

Sociodemographic data: Sex, age, height, weight, employment status, and academic level.

- -

Questionnaire completion date.

- -

PCR negativization date.

- -

Table with the most frequent symptoms of persistent COVID, composed according to CDC's reported symptoms (Table 1).

- -

Alexithymia TAS-20 questionnaire8: The TAS-20 scale has 2 cut-off points, between 52 and 61 points indicates possible alexithymia and 62 or more indicates alexithymia.

- -

Zung depression scale9: The Zung depression scale has 2 cut-off points, between 36 and 51 points indicates moderate depressive symptoms and 52 or more indicates severe depressive symptoms.

- -

Central sensitization inventory10: Made up of 2 subscales, on the one hand, the symptoms scale that is considered positive above 40 points, considering a level of sensitization as mild between 30 and 39, moderate between 40 and 49, severe between 50 and 59, and extreme above 60.11 On the other hand, the scale of diagnoses related to sensitization in which the antecedents of up to 10 possible conditions associated with sensitization are collected.

- -

EuroQoL5 quality of life scale12: Provides an overall health-related quality of life score that ranges between 0 and 100.

An anonymized database is created for statistical analysis of the results.

To assess the correlation between long COVID symptoms and central sensitization symptoms is used the Spearman correlation between the SCI symptoms scale score and the total number of long COVID symptoms. One point is assigned for each symptom described by the patient to score the scale.

A descriptive analysis of long COVID symptoms is performed.

Spearman test is used to evaluate the correlation between Alexithymia and long COVID symptoms by correlating the TAS-20 scale score with the total number of long COVID symptoms.

Spearman correlation is used to evaluate the correlation between depression and long COVID symptoms by correlating the Zung depression scale score with the total number of long COVID symptoms.

ResultsAfter evaluation, 32 patients are finally included in the study, according to the flowchart shown in Fig. 1. All patients resided in the León health area. Four patients were excluded for not undergoing the psychiatric interview, 3 of whom had not yet been scheduled at the time of this study, and 1 did not attend the appointment. Of the patients evaluated by psychiatry, 3 were excluded for suspected symptom malingering, following the criteria of Bianchini, Greve, and Glynn,13 and one more for presenting a diagnosis of COVID-19-related pulmonary fibrosis. The patients were included in the study after completing the psychiatric interview, between March and December 2022.

The profile we found corresponds to a woman in the middle of her fifth decade of life, with university education and currently employed, with a BMI of 25, who suffered a SARS-CoV-2 infection 382.88 days prior to evaluation, for which she did not require hospitalization, and who presents a severe depressive disorder with associated alexithymia (Table 2).

Sociodemographic and clinical variables.

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4 | 12.5% |

| Female | 28 | 87.5% |

| Age | 46.41 | +/−11.11 |

| Range 18–64 | ||

| Academic level | ||

| Basic | 10 | 31.3% |

| Vocational training studies | 3 | 9.4% |

| Baccalaureate | 4 | 12.5% |

| University | 15 | 46.9% |

| Job situation | ||

| Unemployed | 3 | 9.4% |

| Student | 2 | 6.3% |

| Temporary work incapacity | 10 | 31.3% |

| Retired/Permanent disability | 1 | 3.1% |

| Working | 15 | 46.9% |

| No data | 1 | 3.1% |

| Hospitalized by COVID | 5 | 15.6% |

| ICU by COVID | 0 | 0% |

| Days since PCR negative | 382.88 | +/−241.73 |

| Height | 1.65 | +/−0.07 |

| Weigth | 70.08 | +/−13.19 |

| BMI | 25.53 | +/−4.16 |

| Total number of long COVID symptoms | 12.69 | +/−4.21 |

| Total SCI diagnosis | 2.16 | +/−1.80 |

| SCI symptoms score | 60.44 | +/−16.24 |

| Zung depression scale | 55.38 | +/−10.30 |

| TAS-20 alethymia scale | 63.23 | +/−16.60 |

| Quality of life scale EuroQoL | 46.96 | +/−19.83 |

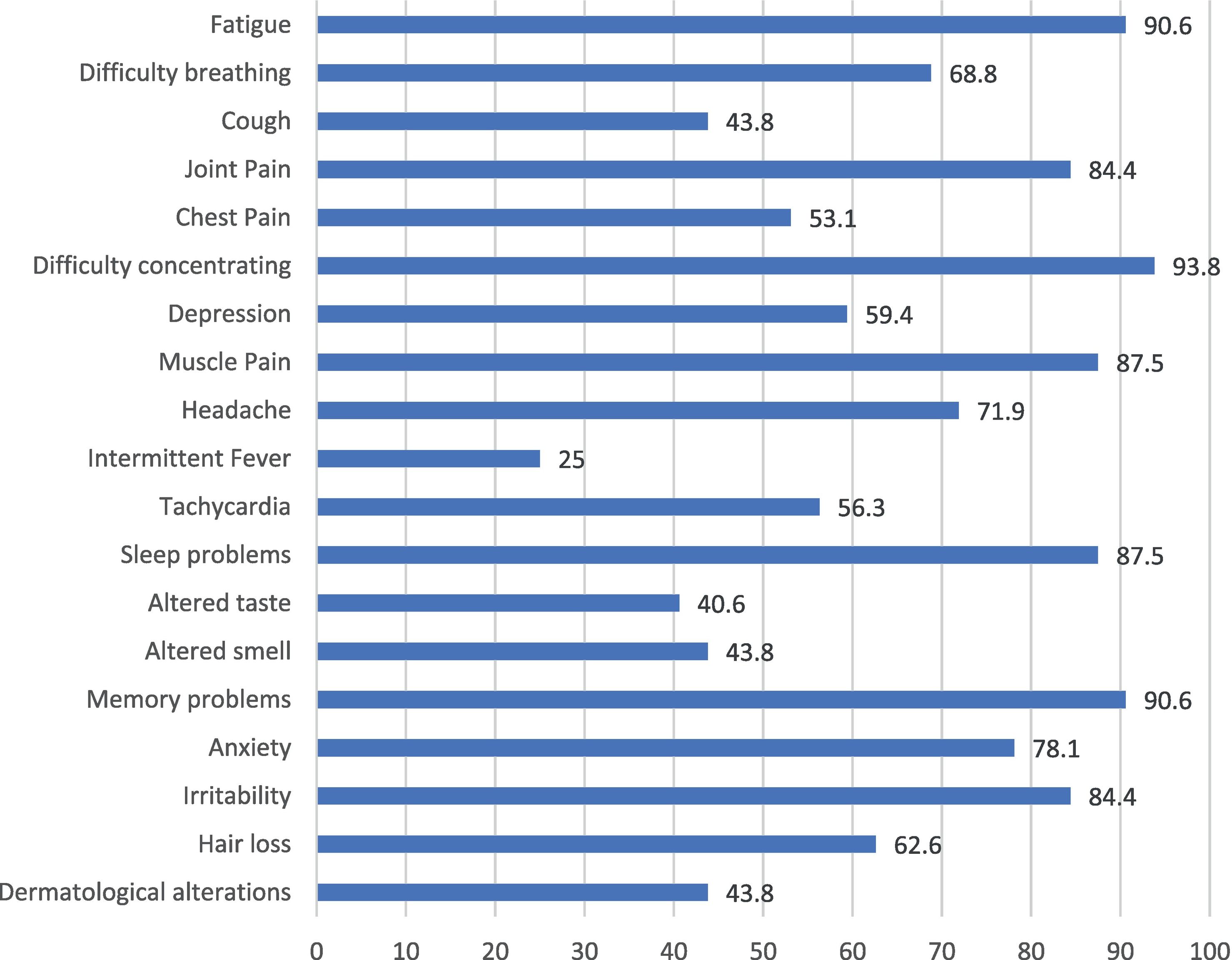

At the symptom level, patients present an average of 12.69±4.21 symptoms out of 19 possible, with the most frequently reported symptoms being fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and memory problems (Fig. 2).

On a descriptive level, we found that the score levels are very high (Fig. 3). In the Zung depression scale, the mean score was 55.38±10.30. A score of ≥52 on this scale indicates a severe depressive episode. In the Toronto alexithymia scale (TAS-20), the mean score was 63.23±16.60. A score of ≥61 on this scale indicates an alexithymic state. Finally, on the central sensitization inventory, the mean score was 60.44±16.24 out of a maximum of 100. A score >40 on this scale indicates a state of sensitization, with the mean corresponding to an extreme state of sensitization.11

We consider it important to highlight that the scales used in this study present a considerably different structure. While all responses are directly scored in the central sensitization scale, both the Zung depression scale and the Toronto alexithymia scale have a large number of items that are scored inversely. It is also worth noting that the Zung depression scale is oriented towards endogenous depressive symptoms and, to a lesser extent, reactive symptoms.

The main variable in this study is to assess the correlation between central sensitization and the sum of long COVID symptoms. In this sense, we obtained an intermediate correlation (rho, 665; p < .01) between these 2 scores. We also observed a correlation between the sum of symptoms presented and the depression score (rho, 467; p < .01), but not between the sum of symptoms presented and the alexithymia score (rho, 151; p = .359). Exploratory correlations were also evaluated between alexithymia and depression, and between depression and sensitization, and strong correlations were found: rho, 720; p < .01 and rho, 736; p < .01, respectively.

DiscussionThe correlation observed between the number of reported symptoms of persistent covid and the SCI symptom scale score could point, with the limitation of the small sample size, towards the fact that sensitization mechanisms could play a relevant role in the appearance of symptoms. Some of the symptoms described by the CDC (Table 1) have clearly subjective characteristics (pain, anxiety, sleep disturbances, etc.), although others are easily objective (intermittent fever, hair loss, tachycardia). The SCI scale presents a compendium of 25 subjective symptoms that are scored between 0 and 4 points depending on their intensity.10 The presence of a correlation between them points towards a common pathophysiological mechanism.

The patient profile obtained in the study points to a pre-infectious situation with a high stress burden, generally among people with a high academic level, highly qualified work performance, and/or high responsibility, and intellectual characteristics, most of whom are women, with gender roles still strongly ingrained in our society, which implies a greater stress burden. The clinical description provided during the consultation is that since the infection, they have begun to fall short of their previous performance and describe the triad of fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and concentration difficulties as the main symptoms. Other studies have also described the high proportion of women compared to men in the development of persistent covid symptoms.14 The characteristic symptoms found in our sample are similar to those found in other investigations, mainly in the field of neuropsychiatric findings, in this way, fatigue and cognitive dysfunction, such as concentration problems, short-term memory deficits, general memory loss have been described.15

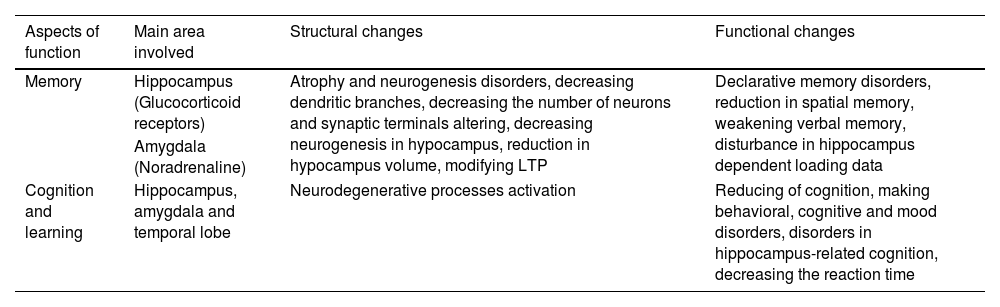

The similarity of the symptoms with those described in relation to the effects of stress on the central nervous system could indicate that the virus could have a direct additive effect on the physiological stress response. It is necessary to highlight the importance of the physiology of the stress response and the structural and functional changes it produces (Table 3), and that many patients, despite not having required hospitalization for the most part, have perceived the infection as a threatening event for their lives. Therefore, it is possible that, in the context of the pandemic terror, the infection by the virus may have exceeded the coping capacity of the patients, who were already functioning close to the pathological threshold of stress before infection.

Destructive effects of stress of CNS function. Adapted from Yaribeygi et al.16.

| Aspects of function | Main area involved | Structural changes | Functional changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | Hippocampus (Glucocorticoid receptors) | Atrophy and neurogenesis disorders, decreasing dendritic branches, decreasing the number of neurons and synaptic terminals altering, decreasing neurogenesis in hypocampus, reduction in hypocampus volume, modifying LTP | Declarative memory disorders, reduction in spatial memory, weakening verbal memory, disturbance in hippocampus dependent loading data |

| Amygdala (Noradrenaline) | |||

| Cognition and learning | Hippocampus, amygdala and temporal lobe | Neurodegenerative processes activation | Reducing of cognition, making behavioral, cognitive and mood disorders, disorders in hippocampus-related cognition, decreasing the reaction time |

Regarding the evidence of a direct biological effect of the virus as the cause of the symptoms, there are currently some hypotheses that require further investigation. It has been demonstrated that the virus presents neurotropic characteristics17 and that there is a state of chronic inflammation associated with alterations in different immunological mediators18 that correlate with the appearance of depressive symptoms. In our study, it was observed that patients presented frank depressive symptoms, with endogenic components, which is consistent with what is described in the literature. Likewise, endothelial alteration and the activation of the coagulation cascade have been described as potential pathways for the appearance of persistent symptoms.19 This would be consistent with the described observations of a symptomatic profile of vascular-type depressive disorders.20

Another variable observed in our study is the high score for alexithymia, which, in addition to difficulty identifying and expressing internal emotional states, has been associated with an amplification of unpleasant bodily sensations.21 In our sample, it was observed that the perception of being depressed was present in 59.4% of the patients, while the depression scale score indicated that 93.8% of the patients had depressive symptoms, in most cases (75%) severe. Therefore, the role of alexithymia suggests that patients may not be able to properly identify how depressed they are, with the added difficulties that this lack of insight entails when initiating treatment. It is striking that patients reported the presence of irritability (84.4%) much more than depression, which suggests that the depressive picture presents atypical characteristics that could be compatible with those described for vascular depression, whose usual clinical characteristics are executive dysfunction, loss of energy, subjective feeling of sadness, anhedonia, psychomotor retardation, motivation problems, reduced processing speed and visuospatial skills, deficits in self-initiation, and lack of introspection.22

The amplification of unpleasant bodily sensations associated with the presence of alexithymia is consistent with the presence of an extreme sensitization score in the SCI inventory. Central sensitization has been proposed as a pathogenic mechanism in conditions of low organic explicability such as fibromyalgia. However, only 6.3% of the patients had a history of having been previously diagnosed with this condition before the infection, and the symptomatic constellation of long COVID and fibromyalgia is different, with cognitive symptoms being more prominent in the former and generalized pain in the latter. In any case, the sensitization score is significantly correlated with the total number of persistent COVID symptoms, although it does not seem that the sensitized neuronal systems are the same as in the case of fibromyalgia.

When it comes to addressing the patients' condition, we are faced with a lack of specific therapeutic tools indicated for long COVID, being forced to perform an empirical treatment. We consider that the currently possible therapeutic approach involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes a comprehensive anamnesis and exploration by a somatic specialist who primarily rules out the existence of sequelae from the infection and provides a reassuring message to the patient once the relevant tests have been carried out; a psychopharmacological approach, due to the presence of depressive symptoms as well as for addressing cognitive dysfunction and fatigue, in this way, the antidepressant vortioxetine, with its procognitive effect,23 could present a suitable profile; and a psychotherapeutic approach, focused in emotional identification and recognition and with the goal of provide a view from an active coping and acceptance attitude.

This study presents the strength of having been carried out in real clinical conditions. The patients included are those who, today, can be found in any consultation. Regarding limitations, we consider that the main one may be the small sample and that the selection of patients through Internal Medicine, Pneumology, and Rheumatology services may have skewed the sample towards more severe patients since most cases, once explored and screened through complementary tests, and with a good explanation of the condition by the clinician, have not required further attention.

Conclusions- -

Central sensitization phenomena seem to have a notable importance in the symptomatic of persistent COVID and present a symptomatic constellation characterized by fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and memory problems.

- -

The profile we found corresponds to a woman in the middle of the fifth decade of life, with higher education and working, with an IMC of 25, who passed the SARS-CoV-2 infection a year ago, did not require hospitalization, and presents an important depressive disorder with associated alexithymia.

- -

Patients with persistent COVID present more severe depressive symptoms than they are capable of perceiving or expressing.

The findings reinforce the biopsychosocial perspective of persistent covid. It would be necessary to expand research on the clinical effectiveness of the different aspects of multidisciplinary intervention in this condition.

Declaration of competing interest and fundingThe authors declare no conflict of interest. This study has not received funding.