Posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome (PRLS) is characterised by subcortical cerebral oedema of vasogenic origin in patients with acute neurological symptoms.1 We present a case of PRLS associated with cyanamide overdose.

Our patient is a 48-year-old woman admitted to the intensive care unit due to low level of consciousness after taking 500mg of Colme® (calcium cyanamide). The patient presented adjustment disorder and was under treatment with cyanamide for alcohol abuse.

At admission we observed somnolence, with the patient opening her eyes when instructed but with no voluntary gaze; menace response absent bilaterally, suggestive of cortical blindness; isochoric and reactive pupils; and nonpersistent horizontal nystagmus. The patient was unable to follow simple instructions, produced unintelligible sounds, and showed loss of strength in the upper limbs with impaired osteomuscular reflexes. The neurological and systemic examination yielded no other relevant findings. An eye fundus examination revealed no alterations. The patient's body weight at the time of admission was 64kg.

Blood analysis showed creatine kinase levels at 2394U/L; aspartate transaminase at 428U/L; alanine aminotransferase at 140U/L; gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase at 240U/L, and bilirrubin at 2mg/dL. The remaining blood analytical values (glucose, urea, creatinine, sodium, potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, ammonia, C-reactive protein, and lactate), gasometric parameters (pH, pCO2, pO2, bicarbonate, and base excess), haematology values (haemoglobin, haematocrit, leucocyte, and platelet count), and coagulation parameters (prothrombin activity, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin ratio, and fibrinogen) showed no alterations with regards to our laboratory's reference values. Urine toxicology, including tests for amphetamines, cocaine, tetrahydrocannabinol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, opioids, and phencyclidine, showed negative results.

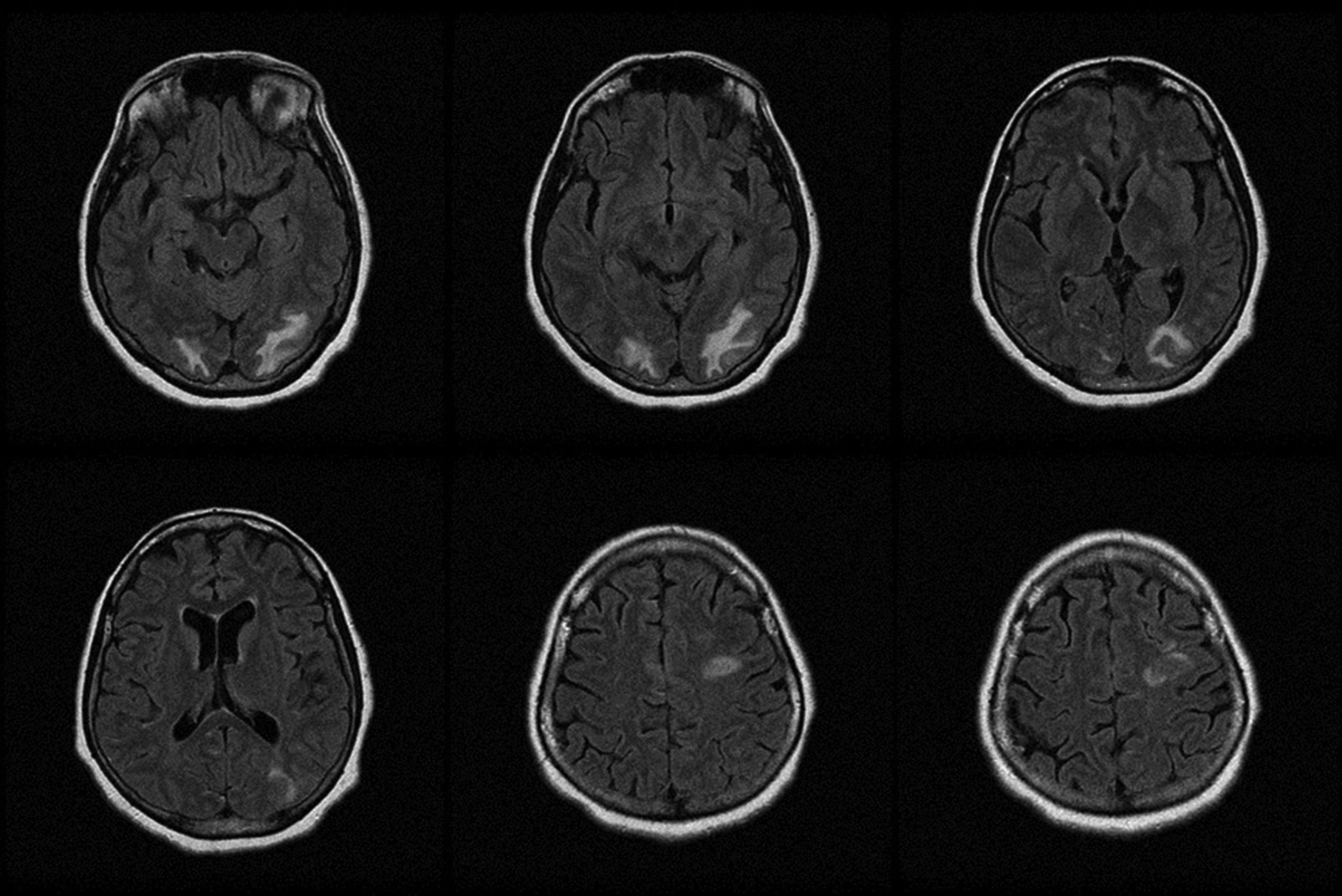

A head computed tomography (CT) scan showed occipital white matter hypodensity bilaterally, predominantly affecting the left side. An electroencephalography showed signs of moderate encephalopathy with no signs of epileptiform activity. MRI findings confirmed the presence of vasogenic oedema associated with PRLS, involving both occipital lobes with focal extension to the parietal and left frontal areas (Fig. 1).

We administered activated charcoal, suspended cyanamide, and continued with life support measures. The patient progressed favourably, fully recovering after 14 days. Blood analysis and electroencephalography findings also normalised. Furthermore, the follow-up MRI scan confirmed the disappearance of the alterations observed at admission. The patient subsequently admitted she had taken calcium cyanamide with suicidal intent and denied having consumed alcohol concomitantly.

Carbimide or calcium cyanamide is used for treating alcoholism as it causes aversion to alcohol by provoking aldehyde syndrome or the Antabuse effect.2,3 In the absence of alcohol consumption, cyanamide is well tolerated at normal doses. Although few cases are described in the literature, overdose in the absence of alcohol consumption has been associated with kidney failure, liver failure, respiratory failure, decreased level of consciousness, and metabolic acidosis.2,3 In our case, symptoms manifested after ingestion of cyanamide and no other associated factor could be identified. Furthermore, the patient explicitly denied having consumed alcohol concomitantly.

Our patient presented acute neurological impairment consisting of encephalopathy associated with cortical blindness. The first CT scan was decisive in the diagnosis, whereas the blood analysis findings did not explain the neurological symptoms. The early MRI study enabled us to establish the diagnosis.

PRLS is characterised by subcortical vasogenic oedema in patients presenting acute neurological alterations.1,4,5 Encephalopathy presents the typical symptoms, from disorientation to deep coma. Other reported symptoms are seizures, visual alterations, and headache. Focal symptoms and signs of spinal cord involvement may manifest less frequently.

Early diagnosis of the syndrome is difficult, especially in emergency situations. However, PRLS should be suspected in cases in which neurological signs and the clinical context are compatible. Imaging studies are essential for establishing an appropriate diagnostic approach. Although some radiological signs of vasogenic cerebral oedema may be observed on CT images, MRI studies better identify this type of lesion.1

Causes associated with PRLS to date include acute changes in blood pressure, acute kidney failure, autoimmune diseases, eclampsia and preeclampsia, sepsis, and administration of certain drugs.1,4,5 In the case of this patient, we did not identify any factor previously associated with this disease.

Prognosis is generally favourable. Between 75% and 90% of patients achieve full recovery during the first weeks. Sequelae reported in the literature include intracranial haemorrhage, hydrocephalus, and intracranial hypertension.1 Fatal cases directly associated with the condition have also been described.6

Diagnosis of PRLS is based on clinical and radiological findings and a compatible clinical context. Therefore, describing all situations associated with this entity may help establish an early diagnosis in future.

Please cite this article as: Peñasco Y, González-Castro A, Rodríguez-Borregán JC, Sánchez-de la Torre R, González-Suárez A. Leucoencefalopatía posterior reversible tras sobredosis de carbimida. Neurología. 2020;35:67–68.